TEXTILE WASTE

Federal Entities Should Collaborate on Reduction and Recycling Efforts

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25‑107165. For more information, contact J. Alfredo Gómez at (202) 512-3841 or gomezj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107165, a report to congressional requesters

Federal Entities Should Collaborate on Reduction and Recycling Efforts

Why GAO Did This Study

While consumers and businesses have options to donate, repurpose, and repair used textiles in the U.S., the majority are discarded into municipal waste streams, according to EPA. The rise in fast fashion has highlighted concerns about textile waste and textile recycling in the U.S., according to EPA officials.

GAO was asked to review issues related to textile waste and recycling. This report describes (1) how textile waste affects the environment; (2) how and why the rate of textile waste in the U.S. has changed in the last 2 decades; and (3) federal actions to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling, and what opportunities exist for entities to collaborate.

GAO reviewed laws, agency documents and data, and leading practices for interagency collaboration. GAO interviewed federal officials, representatives from industry, and other nonfederal stakeholders, such as officials from two state agencies and nonprofit organizations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress consider providing direction to a federal entity (or entities) to coordinate and take federal action to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. GAO is also making 7 recommendations to 6 federal entities, including that they coordinate through an interagency mechanism that follows leading practices. One entity, on behalf of the 6 entities, agreed with the findings but disagreed with coordinating through an interagency mechanism. GAO maintains the recommendations are valid.

What GAO Found

Textile waste—discarded apparel and products such as carpets, footwear, and towels—causes harmful effects to the environment, according to academic and federal reports GAO reviewed. These effects include the release of greenhouse gases and the leaching of contaminants into soil and water as textile waste decomposes in landfills. While data on textile waste are limited, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) textile waste data estimates an over 50 percent increase between 2000 and 2018 in the U.S. According to federal, academic, nonprofit, and industry sources, textile waste has increased because of multiple factors, including a shift to a fast fashion business model; limited, decentralized systems for collecting and sorting textiles; and the infancy of textile recycling technologies.

Some federal entities have initiated and planned a number of efforts to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. For example, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology led a workshop on reducing textile waste in 2021 with participants from industry, academia, government, and trade associations, among others, and is researching methods for textile recycling. The U.S. Department of State leads an informal interagency group focused on extending the life of products and materials; this group held a March 2024 meeting focused on textiles. EPA plans to develop a national textile recycling strategy within 5 to 10 years, according to officials.

GAO found that most federal entities’ efforts are nascent, and their approach depends on their mission and expertise. Further, federal entities carry out individualized efforts on textile waste and recycling and give these efforts a lower priority than other goals. GAO identified opportunities for interagency collaboration to improve these efforts. In 2022, some federal entities took steps to formalize an interagency group, but these efforts have stopped. Interagency collaboration that follows leading practices for enhancing and sustaining collaboration could leverage resources to improve the federal government’s capacity to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling.

Abbreviations

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

ITA |

International Trade Administration |

|

MSW |

municipal solid waste |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

NSF |

National Science Foundation |

|

OSTP |

Office of Science and Technology Policy |

|

PFAS |

per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

|

RCRA |

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976 |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 12, 2024

The Honorable Tom Carper

Chairman

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Rosa DeLauro

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

United States House of Representatives

The Honorable Chellie Pingree

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States House of Representatives

Congressional members, and others, have expressed concerns about the rise of fast fashion and a corresponding increase in textile waste in the United States. First introduced around 2000, the fast fashion business model produces textiles at lower cost and quality, and decreased durability. Under this model, trends change frequently, consumers buy textiles many times per year, and they dispose of textiles after using them for a short period of time. The rise in fast fashion has highlighted concerns about reducing textile waste and advancing textile recycling in the U.S., according to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) officials. Textile waste includes discarded apparel, and non-apparel products such as carpets, footwear, sheets, and towels.

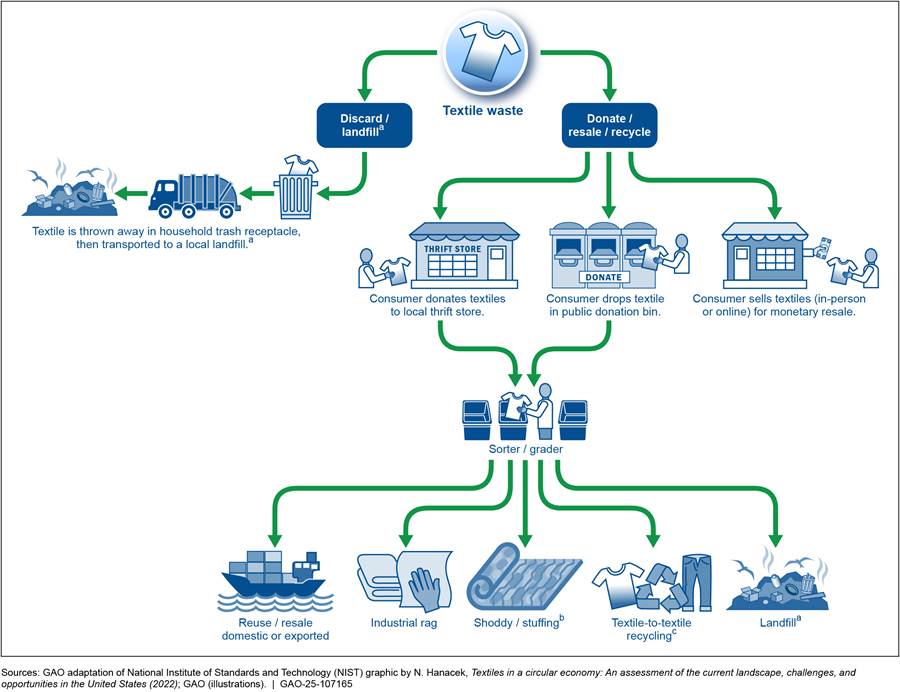

In the U.S., most used textiles are discarded into municipal solid waste (MSW) streams, according to EPA data.[1] Consumers—individuals and businesses—have options to donate, repurpose, recycle, and repair used textiles. For example, individuals may opt to donate used textiles to thrift stores or place them in clothing donation bins. These discarded textiles are collected and then sorted to be repurposed (see fig. 1).[2] However, options may be limited based on location, technology, and individual actions and decision-making.

All levels of government have a role in textile waste and recycling. Federal entities help set national recycling strategies, conduct research, encourage innovation through grants to various entities, and develop education and outreach efforts. Some of the involved federal entities include EPA, the U.S. Departments of Commerce and Energy, and the National Science Foundation (NSF). States and municipalities manage certain solid waste streams through coordination with EPA and other federal entities and develop and implement recycling programs. Other stakeholders conduct research and implement efforts to reduce textile waste and increase the reuse and recycling of discarded materials. These stakeholders include academia, nonprofit organizations (such as Goodwill Industries International, Inc.), and industry (including apparel).

You asked us to review issues related to textile waste and recycling. This report (1) describes how textile waste affects the environment; (2) describes how and why the rate of textile waste in the U.S. changed in the last 2 decades; and (3) examines what actions the federal government is taking to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling, and what opportunities exist for entities to collaborate.

In the Background section, we discuss examples of a nonprofit organization (Goodwill Industries International, Inc.) and a company (Helpsy Holdings PBC) that offers collection and donation options for used textiles. We chose these two organizations based on recommendations from knowledgeable agency officials. By including them as examples in this report, we are not endorsing, sponsoring, or affiliated with them.

To determine how textile waste affects the environment, we conducted a literature review of selected academic reports to obtain information on types of environmental impacts associated with textile waste and any related data. This review included a search of academic databases using a variety of terms, including “textile waste,” “textile waste streams,” “environmental impacts of landfills,” and “environmental impacts of textile waste,” within the last 10 years. We also gathered and analyzed relevant documents and data from selected federal, state, and city agencies; nonprofit organizations; and industry representatives (including apparel companies).

We selected and interviewed federal entities and state agencies, nonprofit organizations, and industry representatives that had ongoing or planned efforts related to reducing textile waste or advancing textile recycling, based on recommendations from knowledgeable officials. The federal entities were the U.S. Departments of Commerce, Defense, Energy, and State; EPA; General Services Administration; NSF; and the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). The selected state agencies were Massachusetts’s Department of Environmental Protection and California’s Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery. We interviewed officials from each of the federal entities and state agencies on environmental impacts associated with textile waste.

We also interviewed officials from selected nonprofit organizations, academia, a city agency, non-profit and for-profit collector and sorters, and industry representatives to obtain their perspectives on environmental impacts associated with textile waste, and efforts and opportunities to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling.[3] We conducted two site visits: (1) to a large non-profit collector and sorter of discarded textiles and (2) a waste management company, three cutting and sewing companies to get a sense of textile waste produced by these types of companies, a non-profit organization that collects and sorts discarded textiles, and a textile-to-textile recycling company in California.

To determine how and why the rate of textile waste in the U.S. has changed in the last 2 decades, we gathered and analyzed documents from federal entities, industry representatives, and nonprofit organizations. We also reviewed the U.S. Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration’s (ITA) textile and apparel import data from 2000 through 2023. We reviewed this data to understand how imports over this time period may have changed, as a change in imports could indicate a change in textile waste in the U.S.

We assessed the reliability of ITA’s import data by interviewing knowledgeable officials and reviewing related documentation, checking the data for completeness and errors, and following up as needed regarding any questions we had about the data. We found the data to be reliable for the purposes of describing what is known about how textile imports have changed over the last 2 decades. We also reviewed EPA’s data on MSW estimates for textiles from 2000 through 2018, which was the last available year of this data.[4] We assessed the reliability of the data by interviewing knowledgeable agency officials and reviewing related documentation. We found EPA’s data to be reliable for the purposes of describing the amount of the textile waste in municipal waste streams for 2000 through 2018.

We also interviewed knowledgeable officials and stakeholders from federal and state agencies, academia, and selected industry and nonprofit organizations about how textile waste has changed over the last 2 decades, including the factors driving this change. Views from selected officials and stakeholders cannot be generalized to those we did not select and interview.

To determine what actions the federal government is taking to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling, and identify opportunities for federal entities to collaborate, we reviewed federal laws and agency documents, such as reports and national strategies.[5] We interviewed federal officials on federal actions related to textile waste and recycling and obtained their perspectives on any associated opportunities to collaborate. We reviewed current and planned future opportunities for federal entities’ coordination and reviewed leading practices for interagency collaboration.[6] We interviewed these officials to reflect a variety of perspectives on current efforts and opportunities to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. Views from these officials cannot be generalized to those we did not interview.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to December 2024, in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal and State Requirements for Managing Waste, Including Textiles

EPA regulates the management of solid and hazardous wastes under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976 (RCRA), as amended.[7] RCRA defines “solid waste” as any garbage, refuse, or sludge from water supply and waste treatment plants or pollution control facilities, and other discarded materials, including materials from industrial operations.[8] Discarded textiles would be classified as nonhazardous solid waste under RCRA unless mixed with a hazardous waste.

As required under RCRA, EPA established guidelines for states to develop and implement solid waste management plans.[9] The guidelines recommend that state waste management plans include recycling and resource conservation whenever technically and economically feasible. States that submit and receive EPA approval for their plans are eligible for federal grants to help implement the approved plan. States can use these grants to support state and municipal recycling programs. EPA also sets location, design, operating, and other criteria for MSW landfills and other solid waste disposal facilities, and prohibits the open dumping of solid waste.[10] RCRA does not require states to report nonhazardous waste flows to the federal government.

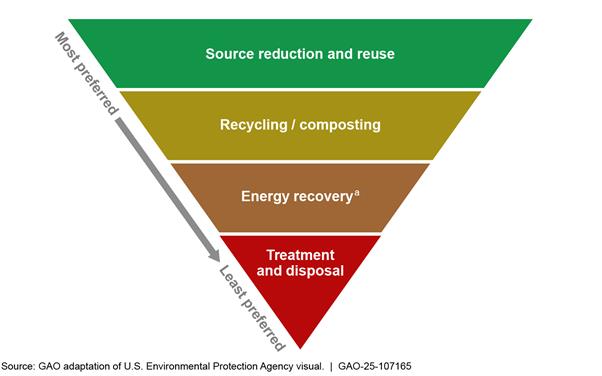

Options for textile waste disposal in the U.S. include landfilling, combustion with energy recovery, and when available, recycling.[11] To help guide waste management decision-making, EPA developed a hierarchy that ranks various MSW management strategies from most to least environmentally preferred, as shown in figure 2. For example, the hierarchy prioritizes reducing waste generation through reduction and reuse, as well as recycling and composting.[12] EPA’s hierarchy considers disposal, such as landfilling and combustion with energy recovery, as the least environmentally preferred strategies. According to EPA’s last reported data, in 2018, 66 percent of textile waste was landfilled, 19 percent was combusted with energy recovery, and 15 percent was recycled.[13]

Notes: As of February 2024, EPA was in the process of reviewing the waste hierarchy to determine if potential changes should be made based on the latest available data and information.

aEnergy recovery from waste, including combustion with energy recovery, is the conversion of non-recyclable waste materials from municipal solid waste streams into usable heat, electricity, or fuel through a variety of processes.

Textile Collection and Recycling

Unlike traditional recyclables, such as plastics and glass, textiles are not processed through material recovery facilities due to a lack of collection infrastructure and limited textile sorting technology.[14] Consumers in the U.S. typically discard unwanted textiles in their household trash, which enters the MSW stream, or repurpose the textiles through individual action, such as donations, as shown in figure 3.

aTextile waste may be combusted through an energy recovery process.

bShoddy is made from shredded fibers and used for insulation and stuffing.

cTextile-to-textile recycling is the process of turning textile waste into new fibers that are then used to create new textiles.

Textiles are collected and sorted based on various factors, such as type of textile (e.g., shirt, pants), color, and fiber composition.[15] Textiles sorted for resale in secondhand markets, both domestically and internationally, are also graded based on the anticipated reuse value. Further, textiles sorted for recycling must undergo pre-processing. Pre-processing involves preparing textiles for recycling by removing trims (e.g., zippers, buttons, seams, ribbings, badges, and labels) and reducing the size of the material (e.g., shredding or cutting the textiles into smaller pieces).

|

Examples of Companies That Offer Collection and Donation Options for Used Textiles Some individuals may choose to donate used textiles by either dropping them in a collection bin, such as one owned and operated by Helpsy Holdings PBC, or bringing them to a thrift store, such as Goodwill Industries International, Inc. Helpsy, for example, is a for-profit company located in New Jersey that collects, sorts, and sells used textiles in 10 states along the East Coast. It collects used textiles from a combination of sources, including donation bins, clothing drive events, and curbside collection. The company seeks permission and pays a fee to property owners, organizations, and municipalities to place bins, host events, and engage in curbside collection. Helpsy also collects used textiles directly from thrift stores that are not able to sort and repurpose unsold items.

Source: Helpsy Holdings PBC (photo). | GAO-25-107165 After collection, Helpsy sorts the used textiles, and then resells the materials to consumers, thrift stores, and sorters and graders in the U.S. and internationally. According to Helpsy staff, the company diverted 31 million pounds of textiles from landfills in 2023. Textiles that are wet, mildewed, or severely contaminated are landfilled by the company. Helpsy estimates that less than 1 percent of the textiles it collects are landfilled. Goodwill Industries International, Inc., is a nonprofit organization with over 3,000 locations in North America. Goodwill accepts many types of donations, including textiles. Employees process and sort the donations based on the quality of the textiles. For example, high value or rare donations, such as designer, vintage, or collectors’ items, are typically sold through ecommerce sites. Textiles that meet retail standards (e.g., free of rips, holes, stains, odors, and moisture) are sorted into specific product categories (e.g., men’s or women’s clothing) and placed on the sales floor. Donations that do not meet retail standards may be sold at Goodwill outlet stores, which are wholesale establishments that sell items at significantly lower prices. According to Goodwill staff we interviewed, one of the nonprofit’s primary goals is to divert waste from landfills. For example, Goodwill estimates that it sold 966 million pounds of textiles in 2022. Textiles that Goodwill is unable to sell in its stores are sold in bulk to buyers and brokers who grade the items into various categories for resale, recycling, export, or landfilling. The organization is also piloting various programs around the U.S. related to repair, reuse, and recycle of textiles with municipalities and companies. |

Source: GAO analysis of documents and interviews with Helpsy and Goodwill staff. Inclusion of these examples in this report should not be interpreted as GAO endorsing, sponsoring, or affiliating with these organizations. Helpsy Holdings PBC (photo). | GAO-25-107165

Textile-to-textile recycling—also known as fiber-to-fiber recycling—is the process of turning textile waste into new fibers that are then used to create new textiles.[16] As we have previously reported, there are two types of textile recycling: mechanical and chemical.[17]

· Mechanical recycling involves physically deconstructing fibers through methods such as shredding, crushing, or melting, before reprocessing fibers back into yarn. Mechanical recycling produces weaker fibers and lower quality textiles that have limited use, such as furniture stuffing or insulation.

· Chemical recycling reduces textiles to their basic molecular building blocks using chemical solutions, and then rebuilds them to produce fibers of similar quality. The required chemical solution differs based on textile material. As a result, current chemical recycling methods are typically not effective for fiber blends; however, some chemical recycling technologies have been successful in the laboratory and small-scale settings.

To operate at scale, both mechanical and chemical recycling processes require consistent, reliable sources of textile waste, referred to as feedstock.[18] Textile waste is typically categorized as post-industrial, pre-consumer, or post-consumer:

· Post-industrial waste is generated during the textile manufacturing process (e.g., cutting scraps from fabric mills or sewing facilities). This type of waste generally has a predictable volume, a high level of uniformity, does not require pre-processing (e.g., removal of buttons and zippers), and is easy to sort because the fiber content is known. As such, it is the most preferred option for textile recycling.

· Pre-consumer waste are textiles that were discarded before being sold to a consumer, such as excess inventory or damaged items. The fiber content is easily identified; however, these textiles often require pre-processing and may not be available in large, uniform volumes.

· Post-consumer waste are textiles that have been used and discarded, either by individual consumers or by commercial sources such as hospitals, hotels, or industrial laundries. This is the largest category of textile waste.

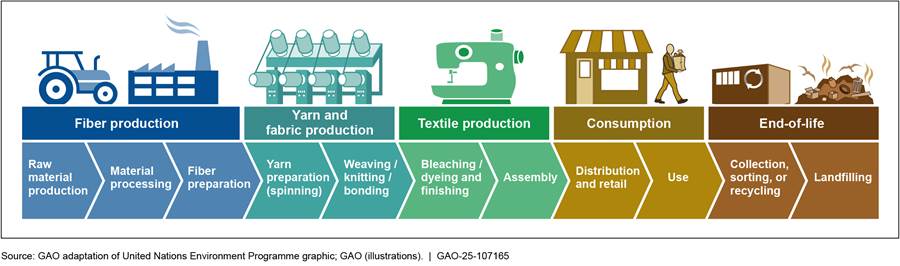

Linear and Circular Economies for Textile Production, Consumption, and Disposal

Currently, textiles are produced in a linear economy, where most raw materials are extracted or harvested, manufactured, distributed, consumed, and then disposed (typically in landfills), as shown in figure 4. Each phase has known environmental impacts and creates waste streams. For example, in a linear economy, the textile and apparel industry typically use non-renewable resources, such as oil to produce synthetic fibers, fertilizers to grow cotton, and chemicals to dye and finish textiles—all of which use large amounts of resources and create negative effects on the environment and people.

Note: The United Nations Environment Programme published the original graphic in 2021 as a figure representing activities taking place in a circular textile value chain. See United Nations Environment Programme (2021), “Catalysing Science-based Policy Action on Sustainable Consumption and Production – The value-chain approach & its application to food, construction and textiles”: 68, Nairobi.

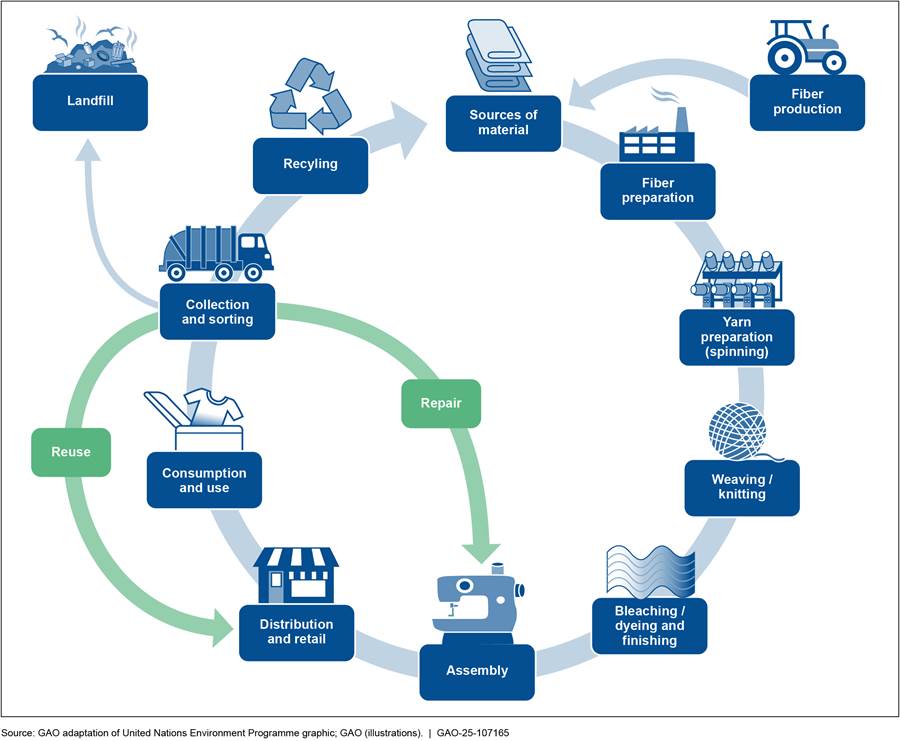

In contrast to a linear economy, federal entities and other stakeholders are developing approaches to transition to a circular economy for textiles. These stakeholders include states, academia, nonprofit organizations, and industry.[19] This economic approach aims to extend the life of products and materials for as long as possible. In a circular economy, textiles are designed for durability, reuse, repair, remanufacturing, and for the recovery of materials at end-of-life through recycling, as shown in figure 5. Overall, this approach requires less raw material and intends to keep products and materials reused within the economy, potentially in different forms.

Note: The United Nations Environment Programme report published the original graphic in 2021 as a figure representing activities taking place in a circular textile value chain. See United Nations Environment Programme (2021), “Catalysing Science-based Policy Action on Sustainable Consumption and Production – The value-chain approach & its application to food, construction and textiles”: 74, Nairobi.

Textile Waste Causes Harmful Effects on the Environment, Such as Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Textile waste causes a variety of harmful effects on the environment, specifically to air, water, and soil ecosystems, according to federal reports and academic research we reviewed. The effects include the release of greenhouse gases as textile waste decomposes in landfills, leaching of contaminants into soil and water, release of microplastics into soil and surface water, and the loss of land and habitat.

Release of greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants. Textile waste accumulates and decomposes in landfills, contributing to the release of greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane, according to a 2024 EPA report.[20] MSW landfills were the third-largest source of human-related methane emissions in the U.S. in 2022, according to EPA’s most recent inventory of greenhouse gas emissions.[21] These gases build up in the atmosphere and warm the earth’s climate, which leads to other changes around the globe, both on land and in the oceans, according to EPA.

Similarly, discarded textiles combusted during the energy recovery process also release greenhouse gases and other pollutants, according to EPA and an academic study.[22] The greenhouse gases include carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and nitrous oxide, all of which contribute to air pollution and climate change. The study also reported that dioxins, which are highly toxic chemical compounds, found in clothing fibers are released into the environment when combusted.

Other gases emitted from landfills also affect public health and the environment. For example, a 2024 academic study reported that waste in landfills—including textiles that contain per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—can emit gases with these contaminants.[23] PFAS are widely used synthetic chemicals that make clothing, carpets, and other products “waterproof,” “water resistant,” or “stain-resistant,” according to a 2022 National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) report.[24] We and others have reported that PFAS are of concern because of their ability to remain in the environment and bioaccumulate to varying degrees in humans, animals, and plants, among other potential harmful effects.[25]

Leaching of contaminants into water and soil. Contaminants, such as PFAS, contained in discarded textiles may leach from landfills and contribute to water pollution, according to academic research and our prior report on PFAS in drinking water.[26] Specifically, academic research found that landfills that accept MSW can produce a water-based solution that may contain contaminants. This solution—leachate—forms when a liquid (such as rainwater) travels through a solid material and retains some of its components.[27] The leachate passes through the landfill and enters the surrounding soil and surface or groundwater.[28] It may further leak into and pollute adjacent rivers. The research also reported that water and soil pollution may continue for decades after a landfill is closed because of the ongoing decomposition of waste.

Release of microplastics into soil and surface water. Microplastic fibers shed or break away from textiles during their product life cycle, including the end-of-life stage, and become a source of pollution, according to an interagency report and academic research.[29] Microfibers,

|

Disposal Ban on Textile Waste in Massachusetts Effective in November 2022, Massachusetts banned textiles from disposal or incineration. (310 Mass. Code. Regs. 19.017(3).) Most of the state’s landfills are expected to close by 2030, according to state officials. The Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection established a series of goals to reduce the state’s overall disposal of solid waste by 30 percent in 2030 and 90 percent by 2050. Officials noted that the state annually sends approximately 2.5 million tons of waste for disposal to other states on a net basis, which includes the total amount of waste exported and imported by Massachusetts. When the agency began examining the state’s municipal solid waste streams, textiles were found to be 5 percent of the total weight of stream. Used textiles were also identified as a valuable commodity due to their reuse and recycling potential. The disposal ban on textiles includes clean and dry clothing, footwear, bedding, towels, curtains, fabric, and similar products. Nonprofit organizations and for-profit companies use collection systems, such as bins, to gather used textiles. The bins are located around the state. Some organizations also collect textiles via curbside collection. Source: GAO analysis of state laws and agency documents and interview with state officials. | GAO‑25‑107165 |

which are less than 5 millimeters in all dimensions, can enter the environment through natural pathways, such as waterways, and engineered pathways, such as wastewater plants. According to the interagency report, about 60 percent of textiles produced today are made with plastic fibers (e.g., synthetics).[30] Another research study found that microplastics (from items including textiles) comprise a significant amount of landfill leachate, which may enter groundwater or soil.[31] Potential harmful environmental effects associated with microfibers include accumulation in soil, water, and organisms, and exposure to people and other organisms. The impacts of this accumulation and exposure are largely unknown. However, people, animals, and plants may be exposed to toxic chemicals that may have been applied to textile fibers during production and then enter the environment as microfibers.[32]

Loss of land and habitat. According to EPA officials, landfill capacity is decreasing in parts of the U.S. (such as states in the Northeast and Southeast) due to increasing amounts of waste, including textiles. Landfilling is the U.S.’s primary disposal option for all MSW, in part because of the amount of available land nationwide. Loss of land and habitat may be an effect of increased textile waste as new landfills are developed, according to a global consulting firm.[33]

EPA Has Estimated an Increase in Textile Waste Over the Past Two Decades; Increase Is Due to Multiple Factors

No standardized approach or national requirement exists for states to collect and report on MSW data, including data on textile waste. The U.S. Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration (ITA) collects data on the amount of textiles and apparel that the U.S. imports. The administration’s data show a 182 percent increase in units of textile and apparel imports in the U.S. between 2000 and 2023, which likely indicates a rise in textile manufacturing and subsequent waste. EPA estimated an over 50 percent increase in textile waste from 2000 through 2018. While EPA’s textile waste estimates have data limitations, they are widely used and remain the best estimates available, according to stakeholders we interviewed. The increase in textile waste is due to multiple factors, according to federal, academic, nonprofit, and industry sources. According to EPA officials, the agency plans to collect data from state-level agencies and revise its MSW estimation methods.

No National Requirement to Collect MSW Data; EPA’s Textile Waste Data Are Limited

Under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976 (RCRA), as amended, EPA has the authority to develop and collect information on managing solid waste.[34] However, no national requirement exists for states to collect or submit MSW data to EPA, nor has EPA developed a national standardized approach for collecting MSW data. Available data related to textile waste are limited:

· States are not required to submit MSW data, including textile waste data, to EPA. According to EPA officials, because states and municipalities collect and define MSW data differently, it is challenging to standardize data across states. For example, states, municipalities, and localities typically conduct waste characterization studies to obtain MSW data, according to EPA officials and representatives from a recycling consulting firm we interviewed. These waste characterization studies involve individuals sorting, categorizing, and weighing samples of MSW at waste management facilities and landfills for a predetermined amount of time. The studies are labor-intensive and expensive according to the representatives. As such, these studies are not updated regularly.

Additionally, waste characterization studies are typically funded by taxpayer dollars, and studies only contain data on residential waste, not commercial waste, according to the recycling consulting firm representatives. Further, states and municipalities often have different textile categories. Some state and municipalities textile categories could include rubber and leather, while others may include mattresses and carpets. According to EPA officials, not all municipalities have a category for textile waste. As a result, textile waste data from states and municipalities are limited and incomplete, and it is challenging to standardize data across states.

· Multiple stakeholders we interviewed told us that data on textile waste are limited. For example, an academic stakeholder told us textile waste data are aggregated from industry sources, and these data are low quality, incomplete, outdated, poorly validated, and collected using unreliable methodologies. The stakeholder added that this lack of robust data results from several issues, including that the textile industry tends not to hire individuals with data skills or offer them training in these areas. Further, the industry is slow to adopt new technologies and platforms. Additionally, textile and apparel companies are not required to disclose data, which limits its public availability. As a result, textile waste data from these sources are limited and incomplete.

· Data on textile reuse and recycling is challenging to track, according to EPA officials and representatives from a recycling consulting firm. As previously stated, textiles are not processed through material recovery facilities due to a lack of collection infrastructure and limited textile sorting technology. Additionally, sorters and graders that process used textiles are typically private companies that are not required to track or publicly report their data, according to the representatives. As a result, textile reuse and recycling data are difficult to track.

Since the 1980s, EPA has published a series of reports—the Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures Fact Sheet—that contain nationwide MSW estimates.[35] In these reports, EPA estimates the tons of materials generated, recycled, composted, landfilled, or sent to facilities for combustion with energy recovery. EPA officials stated that the data in these reports present a nationwide characterization. According to officials, the data are a composition of “snapshots” that are not intended to be used for trend analysis. This is because the methodology uses industry-level data that are supplemented with various other “static” data sources, which may not have been updated when a new report was published. As a result, the reports provide a snapshot of MSW data from one period of time and are intended to help local solid waste facilities manage their waste streams.

We found that EPA’s 2018 Facts and Figures Fact Sheet data are widely used by the nonprofits and industry stakeholders we interviewed. According to NIST officials, EPA’s textile waste estimates are the best available data. EPA issued its last report in 2020, using 2018 data. EPA has not published a report since 2020 because the agency reviewed external MSW estimates that used different methodologies and was concerned its methodology was under-reporting some statistics, according to EPA officials.[36]

Federal Data Indicate Increasing Rates of Textile Waste in the U.S.; Increase Is Due to Multiple Factors

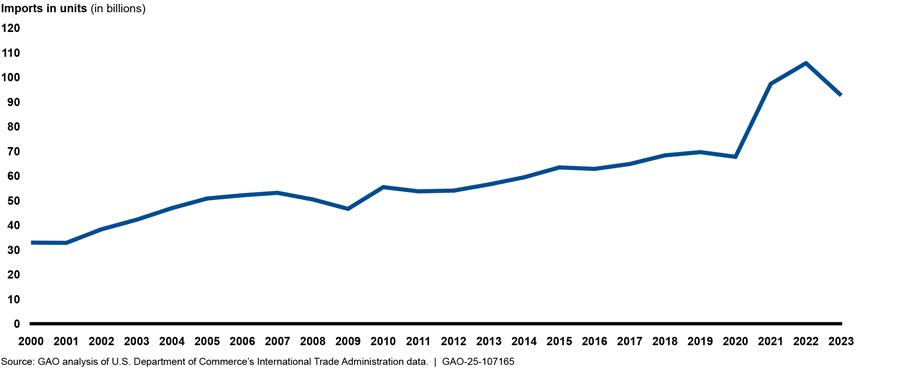

ITA’s data indicate a 182 percent increase in units of textile and apparel imports in the U.S. from 2000 through 2023, which likely indicates an increase in manufacturing and waste (see fig. 6).[37]

Figure 6: International Trade Administration (ITA) Reported Data on U.S. Textile and Apparel Imports, 2000–2023

Note: ITA tracks textile and apparel imports via dollar amount and Square Meter Equivalent units. These units are a common unit of quantity, constant across categories and time. ITA uses conversion factors to covert differing units of quantity (e.g., kilograms, dozens) into Square Meter Equivalents.

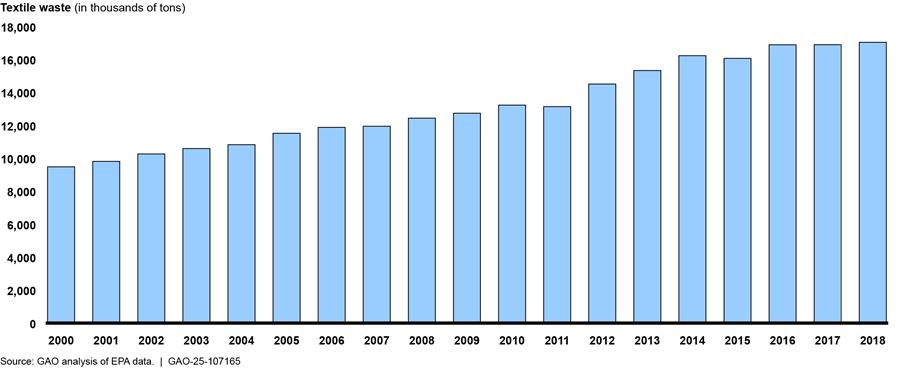

Additionally, EPA data indicate an over 50 percent increase in textile waste from 2000 through 2018, according to its 2020 Tables and Figures report (see fig. 7).[38]

Note: Data presented are from eight EPA reports published from 2003 through 2020, that contain data from 2000 through 2018. These reports base their analyses on prior years of data. The bar graph depicts data as a snapshot—not intended to be used for trend analysis—according to EPA officials.

Textile waste has likely increased in the U.S. in the last 2 decades due to five factors, according to federal, academic, nonprofit, and industry sources. These factors are (1) a shift toward a fast fashion business model; (2) limited, decentralized systems for collecting, sorting, and grading discarded textiles; (3) infancy of textile recycling technologies; (4) increased use of synthetic fibers, such as polyester, and fiber blends, such as cotton-polyester blends; and (5) foreign country bans on the import of used and unsold textiles.

· Shift toward a fast fashion business model

The apparel industry (internationally and in the U.S.) has shifted toward a fast fashion business model in the last 2 decades, resulting in an increase in textile waste, according to federal, academic, and industry documentation, and federal, nonprofit, and industry stakeholders we interviewed. The fast fashion model involves the mass manufacturing and marketing of lower-cost apparel that is quickly delivered to consumers, who then wear and dispose of the garments frequently, according to a 2022 NIST report.[39] These fast fashion products tend to be of lower quality, resulting in a limited ability to resell or repurpose the garments. According to representatives we interviewed from a nonprofit organization, fast fashion apparel is challenging to resell because the garments are lower quality and not designed to last. As a result, these nonprofit representatives said they have seen a decline in the overall quality of apparel donations.

· Limited, decentralized systems for collecting, sorting, and grading discarded textiles

No consistent, convenient, and widespread infrastructure exists to collect textiles suitable for recycling or to retain value on the secondhand market, according to federal and nonprofit documentation, and federal, nonprofit, and industry stakeholders we interviewed. Without adequate collection infrastructure, individuals’ options to discard their textiles may be limited based on their location or knowledge of donation centers. As a result, individuals may opt to dispose of textiles in the municipal waste stream, which is sent to landfills. If individuals increase their consumption of textiles, then the lack of infrastructure leads to an increase in textile waste. As previously stated, textiles are not processed through material recovery facilities due to a lack of collection infrastructure. Additionally, textiles cannot be easily added to existing collection systems due to contamination issues, according to a 2022 NIST report.[40] For example, to be reused or recycled, textiles must be dry, clean, and free from hazardous chemicals or odors.

There is a lack of textile sorting and grading facilities across the country, according to federal, academic and nonprofit documentation, and federal, nonprofit, and industry stakeholders we interviewed. The limited ability to sort textiles contributes to an increase in waste. Textile sorting and grading is currently performed manually, according to the NIST report, as shown in figure 8.[41] Manual sorting is time consuming and challenging due to identifying the fiber composition of discarded textiles, according to an academic study.[42] Representatives from an apparel company told us the manual sorting process is expensive.

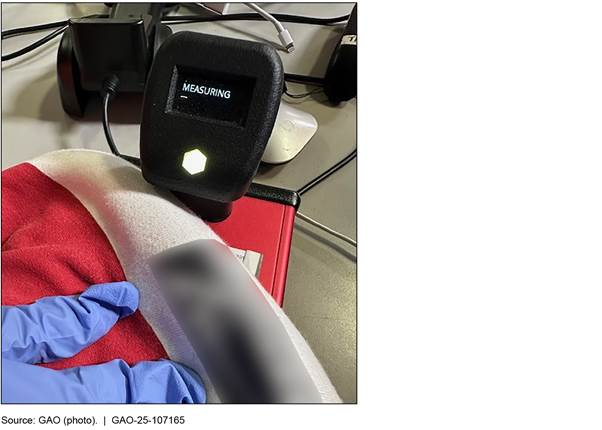

Sorting facilities are increasingly using technology to aid in fiber identification, according to the NIST report.[43] For example, some sorters use devices that use light to rapidly identify different types of fiber, as shown in figure 9. However, a nonprofit organization reports that these technologies are still in the development and trial stages.[44]

This identification is important to help the sorting facility determine if a recycling pathway is feasible. However, these devices currently are limited in their ability to accurately identify fiber blends (e.g., cotton polyester blends), according to the NIST report.[45] In addition, these devices are unable to identify stains, rips, level of wear, or screen for current fashion trends, all of which may affect the resale value. As a result, many of the available identification devices or technologies still require some level of human labor, and no sorting or grading standards or criteria exists.

· Infancy of textile recycling technologies

Textile recycling technology is in its infancy, according to federal, academic, and nonprofit documentation, and nonprofit and industry stakeholders we interviewed. If individuals increase their consumption of textiles, then the limited ability to recycle textiles in the U.S will contribute to an increase in waste. As previously stated, post-industrial textile waste is best suited for recycling because it is easy to identify and sort, and typically does not require pre-processing (see fig. 10). This type of textile waste is a valuable feedstock and is most preferred by recyclers; however, most textile waste is post-consumer, according to a report from a nonprofit organization.[46]

As we have previously reported, mechanical recycling has limitations.[47] While this method of recycling textiles is the most established, it produces lower quality materials that have limited use, and it may not be best suited for textile-to-textile recycling, according to academic research.[48] Mechanical recycling processes also affect fiber types differently; as such, mechanical recycling is better suited for single material textiles (e.g., 100 percent cotton) than for blended ones, as based on our prior work, academic research, and an industry report.[49]

Likewise, as we have previously reported, chemical recycling also has limitations.[50] Various chemical textile recycling technologies have been successful in laboratories and other small-scale settings.[51] However, they largely remain in the research and development phase, according to our prior work and research.[52]

Commercial-scale textile recycling is also limited by a lack of reliable feedstock, according to multiple stakeholders we interviewed. To make recycling economically feasible, recyclers must have consistent access to feedstock, according to representatives we interviewed from an apparel company. Feedstock for recycling purposes must meet certain conditions such as volume, quality, location, and cost,

|

Example of U.S. Company Recycling Textile Waste into New Polyester Fibers Ambercycle, Inc. is a Los Angeles-based textile-to-textile recycling company that is researching and developing systems to create and scale recycled polyester from discarded textiles. According to Ambercycle staff, the company focuses on polyester because it is one of the most commonly used synthetic fibers, especially in textiles. The company uses post-industrial and post-consumer textile waste to create its final product. For example, it sources some of the discarded textiles from a third-party company that collects the waste from apparel factories and other sources. Ambercycle developed a process to chemically extract polyester from discarded textiles and recycle it into new polyester: 1. Discarded textiles are cut and shredded for ease of processing. 2. Polyester is chemically separated from the discarded textile. 3. Any remaining additives, such as dyes or coatings, are removed from the polyester. 4. The purified polyester is melted and formed into polyester pellets that are ready to be used by manufacturers for fiber production. These recycled polyester pellets are designed to be a ready-to-use replacement for new polyester by manufacturers for ease, convenience, and to reduce any external costs, such as having to switch machinery. According to Ambercycle staff, the ease and cost of creating the polyester pellets depends on the contamination level of the fabrics that the company uses at the start of its recycling process. For example, if the fabrics are relatively clean, it is easier to create the pellets. However, if they are contaminated, the process becomes more costly and time-consuming. Ambercycle staff told us the company is also researching how to recycle other fibers from discarded textiles, including cotton and spandex. Source: Ambercycle documentation and interview with staff. | GAO‑25‑107165 |

according to a report from a nonprofit organization.[53] In addition, some textiles must undergo removal of dyes, additives, and finishes before being recycled, according to the NIST report.[54] This can involve hazardous substances subject to different regulations under RCRA and other legal requirements. Advancements in recycling technology and increased access to feedstock needs to occur simultaneously, according to multiple stakeholders we interviewed. This is necessary because recyclers are hesitant to invest in large-scale infrastructure without assurance that the feedstock will be accessible, according to the NIST report and a representative we interviewed from a nonprofit organization.[55]

· Increased use of synthetic fibers, such as polyester, and fiber blends, such as cotton-polyester blends

The increased use of synthetic fibers (e.g., polyester and nylon) and fiber blends (e.g., cotton polyester blends) poses challenges to textile recycling processes. As a result, textile waste has increased, according to federal, academic, and nonprofit documentation. Synthetic fibers and blended fiber compositions are used in many textiles produced today because of their performance characteristics, such as stretch and shrink resistance. According to a 2022 peer-reviewed article by NIST staff, demand for natural fibers (e.g., cotton and wool) has remained relatively constant. However, demand for synthetic fibers, especially polyester, has increased and this trend is expected to continue increasing. An estimated 60 percent of apparel and 70 percent of household textiles contain synthetic fiber, according to the article.[56]

· Foreign country bans on the import of used and unsold textiles

Some countries have banned the import of used textiles, according to federal and academic documentation. The inability to export used textiles may result in increased textile waste in U.S. landfills. Used garments have been historically exported to developing regions in Africa, Asia, and Central America,[57] according to a 2022 NIST report.[58] Several countries have banned or increased the tariffs on the import of used textiles to reduce pollution and protect their own domestic textile industries, among other factors.[59]

EPA Plans to Collect MSW Data from States and Revise Its Data Reporting Methods

EPA plans to collect MSW data, which could include textile waste, from state agencies via an information collection request that is under review by the Executive Office of the President’s Office of Management and Budget, according to EPA officials. This request will allow EPA to gather information that it currently does not collect, including state-level information on MSW collection and recycling. EPA plans to use the information to support its Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures Fact Sheet, which includes separate estimates for various materials. However, EPA officials said they do not know how many states, if any, will have data specific to textile waste.

EPA plans to publish its next Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: Facts and Figures Fact Sheet in 2025 using a revised methodology that will produce national estimates of MSW that are more consistent with those produced by state and territorial agencies, according to EPA officials. The updated methodology will rely more on publicly available data and less on data provided by industries. For example, EPA plans to use data from waste characterization studies, solid waste management reports, recycling reports, and any other applicable data from states and municipalities. As previously stated, states and municipalities collect and define waste data differently, according to EPA officials. As such, officials said the 2025 report may try to incorporate data (if available) from states and municipalities.

Federal Entities Have Initiated Efforts to Address Textile Waste and Recycling, but Opportunities Exist to Collaborate

Some federal entities have initiated or planned efforts to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. However, we found that federal entities have largely implemented the efforts individually, and these efforts are less of a priority than other goals or programs. Currently, there is no national requirement for agencies to address textile waste and advance recycling. We also found that there is limited interagency collaboration specifically targeting textile waste and recycling and opportunities exist for federal entities to collaborate on reducing textile waste and advancing recycling. Further, information is not readily accessible on possible federal funding sources for efforts related to reducing textile waste and advancing textile recycling for other stakeholders, including municipalities and nonprofit organizations.

Federal Entities Have Initiated and Planned Largely Individual Efforts

Federal entities, such as EPA and NIST, have planned or initiated efforts to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling (see table 1). We found that the federal entities’ approaches and efforts vary, in part, due to their differing missions.

Table 1: Federal Entities’ Missions and Efforts (active or planned) for Reducing Textile Waste or Advancing Textile Recycling, as of September 2024

|

Federal Entities and their Missions |

|

Description of efforts (active or planned) |

|

U.S. Department of Commerce (Commerce) |

||

|

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) |

||

|

To promote U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing measurement science, standards, and technology in ways that enhance economic security and improve quality of life. |

|

· Led workshop with participants from industry, academia, government, and trade associations, among others, in 2021 on reducing textile waste and moving toward a textile circular economy, summarized in a report published in 2022. NIST cohosted a second workshop in 2023 on identifying standards needed to facilitate a circular economy for textiles. NIST plans to issue another report based on the workshop and has initiated standards development activities. · Conducts research on new methods related to mechanical recycling of textiles, investigates the role of additives and contaminants on chemical recycling processes. · Develops reference data for textile fibers of known composition (e.g., cotton or polyester) to assist textile sorters in using near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy for classification and sorting of post-consumer textiles. · Examines novel alternatives to conventional materials that could be used to design products that are more easily reclaimed at end of life. |

|

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) |

||

|

To understand and predict changes in climate,

weather, ocean, and coasts, |

|

· Chairs an Interagency Marine Debris Coordinating Committee mandated in the Save Our Seas 2.0 Act to submit to Congress a report on microfiber pollution that includes (1) a definition of microfiber; (2) an assessment of the sources, prevalence, and causes of microfiber pollution; (3) a recommendation for a standardized methodology to measure and estimate the prevalence of microfiber pollution; (4) recommendations for reducing microfiber pollution; and (5) a plan for how federal agencies, in partnership with other stakeholders, can lead on opportunities to reduce microfiber pollution during the 5-year period from December 2020 to December 2025. NOAA issued the report in 2024 with support from EPA and a consulting firm. |

|

International Trade Administration (ITA) |

||

|

Create prosperity by strengthening the international competitiveness of U.S. industry, promote trade and investment, and ensure fair trade and compliance with trade laws and agreements. |

|

· Collects and publicly reports data on textile and apparel imports and exports, and used textile export data, on a monthly and annual basis. · Conducts research and analysis of data sources and textile waste technologies, among other information. |

|

U.S. Department of Energy (Energy) |

||

|

Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies Office |

||

|

To inspire people and drive innovation to transform materials and manufacturing for America’s energy future. |

|

· Oversees an innovation prize challenge for industry—Re-X Before Recycling Prize—that supports new or expanded supply chains to reintegrate end-of-use products into the economy. Textiles are a product type within the challenge’s scope. · Funds a manufacturing institute for industry—Reducing Embodied-energy And Decreasing Emissions (REMADE)—that focuses on circularity within four broad material classes, including fibers. The institute also funds a few projects related to improving textile circularity, including textile sorting. |

|

Bioenergy Technologies Office |

||

|

Supports the research, development, and demonstration of technologies aimed at mobilizing domestic renewable carbon resources for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions across the U.S. economy. |

|

· Funds and coordinates the Bio-Optimized Technologies to keep Thermoplastics out of Landfills and the Environment (BOTTLE) Consortium with the Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies Office. The consortium has several efforts underway that focus on a wide range of plastics recycling challenges, including textile waste. · Funds research on development of renewable textile replacements, such as replacing the production of some synthetic fibers from petroleum. |

|

U.S. Department of State (State) |

||

|

To protect and promote U.S. security, prosperity, and democratic values and shape an international environment in which all Americans can thrive. |

|

· Coordinates with other countries, federal entities, and others on various efforts to reduce plastic pollution and transition to circular economies, including textiles. · Leads an interagency monthly call on circular economies, which touches on domestic and international engagement on a wide diversity of circularity efforts across different resources and sectors. · Leads U.S. engagement on the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal, which regulates the international movements, management, and disposal of hazardous wastes of the parties to the Convention. While most textile wastes are not considered “hazardous waste” under the Basel Convention, agency officials recognize that other countries are working on a proposal to subject textile waste to the control mechanisms of the Basel Convention in the spring of 2025. |

|

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) |

||

|

Office of Land and Emergency Management |

||

|

To protect human health and the environment. |

|

· Plans to develop a national textile recycling strategy as part of its 2021 National Recycling Strategy series within 5 to 10 years, according to agency officials. This series is part of EPA’s effort to build a circular economy in the U.S. · Oversees grants for states, municipalities, and Indian Tribes for the Solid Waste Infrastructure for Recycling program that can fund and support improvements to the management of local post-consumer materials and municipal recycling programs. Projects to address textile waste management and recycling could fall within the scope of eligible grant activities. |

|

National Science Foundation (NSF) |

||

|

To promote the progress of science; to advance the national health, prosperity, and welfare; and to secure the national defense. |

|

· Funds the North Carolina Textile Innovation and Sustainability Engine that aims to increase the U.S.’s capacity for environmentally sustainable textiles by innovating smart textiles and wearable technology, reducing carbon emissions, reducing the disposition of textiles to landfills, and nurturing the development of new product lines that use circular methods. · Funds the Convergence Accelerator program, which encourages research and innovation. One of the program’s efforts—the Sustainable Materials for Global Challenges—has awarded funding to advance the circular economy and research topics related to textiles. · Funded a demonstration project for manufacturing textiles that automated the production process and enabled customization and on-demand production. This project could decrease textile waste in the U.S. |

Source: GAO analysis of legal provisions, agency documentation, and interviews with agency officials. | GAO‑25‑107165

We found that most efforts underway by federal entities were started within the last 5 years or are being planned for future implementation. Officials from most of the entities with whom we spoke stated that, in general, reducing textile waste and advancing textile recycling is an emerging issue within their agency. The rise in fast fashion has highlighted concerns about reducing textile waste and advancing textile recycling in the U.S., according to EPA officials.

Officials from each federal entity also told us that their efforts to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling are not a priority. Further, no federal entity is required to address textile waste or advance textile recycling specifically. Instead, some legislation and federal entities’ efforts to improve recycling generally, reduce marine debris, and transition toward plastics circularity indirectly address some aspects of textile waste. For example, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides grants for states and other eligible entities to encourage recycling generally through education and outreach but does not specifically target textile recycling.[60] Marine debris could include discarded textiles if they are disposed of or abandoned into the marine environment or Great Lakes. Officials from the Department of State also told us their agency’s primary goal is to advance plastic circularity through international negotiations on plastic pollution. Officials from EPA, Department of State, and NIST stated that limited resources, including staffing, informs their entities’ programmatic efforts and priorities.

As of August 2024, EPA officials told us they expect to release an official strategy for textile recycling, in part due to the level of interest by Congress and the public. EPA released its National Recycling Strategy: Part One of a Series on Building a Circular Economy for All in 2021. That strategy included goals to increase the national recycling rate to 50 percent by 2030 and transition toward a circular economy nationwide.[61] EPA designed the strategy to be implemented in a series that focuses on various products and materials separately.[62] EPA officials told us the textile strategy may be initiated in the next 2 to 3 years and finalized within 5 to 10 years.

EPA officials have begun to identify some of the information and data it will need to develop the textile waste strategy, including

· the amount of textiles recycled in the U.S.;

· current infrastructure in the U.S. that recovers and reuse textiles (such as the number of facilities that collect discarded textiles);

· identification of stakeholders involved with repurposing and recycling textiles (such as the apparel industry);

· international policies and efforts to reduce textile waste;

· export information related to textile waste; and

· the fiber composition of textiles, including the amount of plastics currently used, to help determine possible disposal and reuse options.

Organizations that could provide some of the information and data include (1) other federal entities, such as ITA; (2) other countries; and (3) nonfederal stakeholders (such as apparel trade associations and nongovernmental organizations) according to EPA officials.[63] EPA has also identified challenges to obtaining this information and data. For example, some of the identified data and information may be difficult to find or access because data related to textile waste, reuse, and recycling is often privately owned and limited. Further, some of these stakeholders that may have data or information have not previously worked or collaborated with EPA. However, officials told us that a lack of data should not delay policy decisions and efforts. EPA officials stated the challenge to initiating work on the textile strategy is staff bandwidth and other agency programmatic efforts.

Because the federal efforts underway or planned are being implemented individually, there may be fragmentation across these federal entities. Our Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication Evaluation and Management Guide states that fragmentation occurs when more than one federal entity (or organization within an entity) is involved in the same broad area of national need.[64] As described above, most federal entities’ efforts are nascent, and their approach to reducing textile waste and advance textile recycling varies depending on their mission and expertise.

Fragmentation may be beneficial as federal entities start to implement their efforts. For example, fragmentation could continue to allow each entity to apply its specific mission, strengths, and skillsets to the issues associated with textile waste and recycling while engaging different stakeholders on these issues and helping identify gaps that may exist across entities’ efforts. At that same time, a fragmented approach across federal entities could create negative effects and challenges, including potential overlap and duplication. For example, limited federal resources (i.e., staff) and different entities working on the same issues could lead to potential duplication and an inefficient use of resources.

Without congressional direction, it is likely that federal entities will continue with their individual efforts and face potential fragmentation and duplication. Officials from some entities told us that congressional direction is necessary because efforts on reducing textile waste and advancing textile recycling may be delayed and not coordinated. Several officials also told us that under existing authorities, like RCRA, they can implement some efforts to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. However, as efforts are implemented, federal entities may identify additional authorities that may be needed. With congressional direction and delegated authority, federal entities would be better positioned to take coordinated action to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling.

Opportunities Exist for Federal Entities to Collaborate to Reduce Textile Waste and Advance Recycling

While federal entities have planned or initiated efforts, we found that opportunities exist for federal entities to collaborate on efforts to reduce textile waste and advance recycling. Currently, officials from multiple federal entities participate in an informal interagency group on circularity. These agencies include the U.S. Departments of State, Defense, Energy, and Commerce, NSF, and EPA. The Department of State formed the interagency group in 2020 to develop a fuller understanding of the breadth of U.S. federal entities’ actions related to circularity, according to officials. The group’s March 2024 meeting focused on selected ongoing federal efforts related to textile circularity. For example, EPA presented an overview of the agency’s Environmentally Preferable Purchasing program, textile sustainability, and eco-labeling standards. NIST also presented on its work to develop a circular economy for textiles in the U.S. In 2022, an effort to formalize the group through a National Science and Technology Council charter was initiated. The draft charter identified EPA, NIST, the Department of State, and OSTP as the four joint co-chairs. However, the charter was not finalized, and OSTP agency officials told us there are no plans to formally revive the effort to finalize it because it is not a priority.[65]

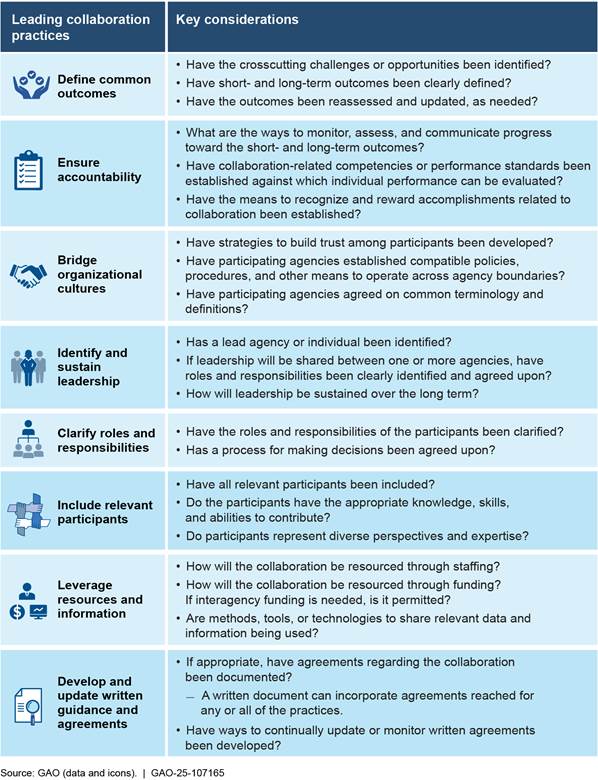

In our prior work, we found that interagency collaboration involves two or more federal entities.[66] Collaboration can be broadly defined as any joint activity that is intended to produce more public value than could be produced when the organizations act alone. Such collaboration can help federal entities better manage fragmented federal efforts, reduce unnecessary duplication, and leverage resources.[67] In addition, we have also identified leading interagency collaboration practices and selected key considerations for enhancing and sustaining collaboration between federal entities (see fig. 11). Interagency collaboration that utilizes our reported leading practices could leverage agency-wide skills, knowledge, and resources to improve the federal government’s overall capacity to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling.

As described above, most of the federal efforts to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling are nascent or still in planning stages. Officials from some of the federal entities with which we spoke—such as the Department of Energy, NSF, and NIST—fund or lead efforts related to research and development on textiles and textile recycling. Although officials are aware of the efforts occurring within their own entity, programs across federal entities could be implemented with greater efficiency and effectiveness with sustained interagency collaboration that aligns with leading interagency collaboration practices and considerations. For example, officials from a few federal entities told us they were interested in understanding more about the material composition of textiles to help their review of current textile labeling standards, and available research on recycling pathways for different textiles based on their composition. Collaboration amongst federal entities interested in this topic could reduce the risk of fragmented and duplicative efforts across multiple federal entities, potentially resulting in cost savings.

Officials from most of the federal entities with whom we spoke said that interagency collaboration on reducing textile waste and advancing textile recycling is needed and told us it would be beneficial. EPA officials explained that issues related to textile waste and recycling are unique because no single federal entity is tasked with the management of textiles. OSTP officials added that interagency collaboration is a tool to advance policy areas where activities and responsibilities are distributed across several departments and federal entities. Various mechanisms that could facilitate interagency collaboration include Memorandums of Understanding, working groups, or charters (such as National Science and Technology Council charter) that consider leading interagency collaboration practices, clearly define common outcomes, involve relevant federal participants, and identify data, funding, and resource needs.

Officials also recognized that, when considering how to collaborate, specific federal entities may be better situated to lead efforts related to textile waste reduction and recycling because of the complexity involved with discarded textiles. For example, officials from the Department of Energy told us that EPA may be better suited to develop policies to reduce textile waste and improve recycling opportunities, while NSF and the Department of Energy could contribute toward the development of related research. We also previously reported that in some cases it may be appropriate or beneficial for multiple federal entities to be involved in the same programmatic or policy area due to the complex nature or magnitude of the federal effort.[68] If federal entities do not take opportunities to collaborate, they may waste time or resources and work in counterproductive ways, as noted in a report on recent federal efforts to address microfiber pollution.[69]

Information Is Not Easily Accessible on Identifying Sources of Funding for Efforts to Reduce Textile Waste and Advance Recycling

Stakeholders at local and state agencies and a non-profit organization told us that they faced challenges accessing information on available federal grants that could be used to fund efforts related to reducing textile waste and advancing textile recycling. For example, representatives from a municipality and a nonprofit organization described how, because information was not easily accessible, they worked together to identify potential federal funding sources that could be used to develop a textile recovery and reuse facility in their city.

Representatives from other nonprofit organizations told us federal funding (e.g., grants) would be helpful to scale effective programs from the research and development phase to a regional or national level. EPA’s 2021 National Recycling Strategy includes objectives and actions to compile and share available funding sources and related resources. Currently, EPA maintains a webpage that lists available funding opportunities (such as grants) from the entity and other federal entities that are related to reducing food waste.[70] However, it does not maintain a webpage that lists such opportunities related to reducing textile waste. By making funding information more accessible, stakeholders may be able to more effectively apply for and fund textile waste reduction efforts, and report to EPA on best practices. Further, if EPA improves its communication on funding for grants that can be used for reducing textile waste and reaches a larger number of potential applicants, it could review a greater variety of proposed efforts. In addition, EPA could compile and make publicly available best practices and successful models to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling.

Conclusions

Textile waste continues to increase in the U.S. due to a variety of factors, including a shift toward fast fashion by the apparel industry and limited, decentralized systems for collecting, sorting, and grading discarded textiles. Without reducing the amount of textile waste, the harmful effects to air, water, and soil ecosystems will also continue to increase, including releasing more greenhouse gases from the decomposition of textile waste in landfills.

Federal entities are beginning or planning to implement efforts that reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. However, most of these efforts are conducted individually by the entities. Managing textile waste and recycling is not tasked to one federal entity. Because reducing textile waste and advancing textile recycling is still an emerging issue across federal entities, congressional direction could require them to take coordinated action to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. In addition to congressional direction, interagency collaboration is essential to implementing current and future efforts more effectively and efficiently. For example, EPA’s National Recycling Strategy has the goals of increasing the national recycling rate by 50 percent by 2030 and transitioning toward a circular economy nationwide, including for textiles. Increasing interagency collaboration through a mechanism that incorporates identified best practices, such as identifying and leveraging resources, may also help agencies better manage fragmentation amongst their efforts.

Nonfederal stakeholders, including local agencies and nonprofit organizations, are also piloting programs and efforts to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. Federal funding to support these efforts, such as grants from EPA and other federal entities, are available. However, information about potential federal sources is not easily accessible on EPA’s website. By making funding information more accessible, stakeholders could use funding toward efforts that help decrease the harmful environmental effects of textile waste or advance textile recycling technologies and infrastructure.

Matter for Congressional Consideration

Congress should consider providing direction and expressly delegate authority to a federal entity (or entities) to take coordinated federal action to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. (Matter for Congressional Consideration)

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of seven recommendations, including one to NIST, one to OSTP, one to the U.S. Department of State, one to the U.S. Department of Energy, one to the National Science Foundation (NSF), and two to EPA. Specifically:

The Administrator of EPA, in conjunction with NIST, OSTP, NSF, and the U.S. Departments of State and Energy, should establish an interagency mechanism to coordinate federal efforts on textile circularity, reducing textile waste, and advancing textile recycling in the US. This interagency mechanism should identify and involve federal participants and should consider leading collaboration practices, including clearly defining common outcomes and identifying data and resource needs. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of NIST, in conjunction with EPA, OSTP, NSF, and the U.S. Departments of State and Energy, should establish an interagency mechanism to coordinate federal efforts on textile circularity, reducing textile waste, and advancing textile recycling in the US. This interagency mechanism should identify and involve federal participants and should consider leading collaboration practices, including clearly defining common outcomes and identifying data and resource needs. (Recommendation 2)

The Director of OSTP, in conjunction with EPA, NIST, NSF, and the U.S. Departments of State and Energy, should establish an interagency mechanism to coordinate federal efforts on textile circularity, reducing textile waste, and advancing textile recycling in the US. This interagency mechanism should identify and involve federal participants and should consider leading collaboration practices, including clearly defining common outcomes and identifying data and resource needs. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of State, in conjunction with EPA, NIST, NSF, and OSTP, and U.S. Department of Energy, should establish an interagency mechanism to coordinate federal efforts on textile circularity, reducing textile waste, and advancing textile recycling in the US. This interagency mechanism should identify and involve federal participants and should consider leading collaboration practices, including clearly defining common outcomes and identifying data and resource needs. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Energy, in conjunction with EPA, NIST, NSF, and OSTP, and the U.S. Department of State, should establish an interagency mechanism to coordinate federal efforts on textile circularity, reducing textile waste, and advancing textile recycling in the US. This interagency mechanism should identify and involve federal participants and should consider leading collaboration practices, including clearly defining common outcomes and identifying data and resource needs. (Recommendation 5)

The Director of NSF, in conjunction with EPA, NIST, OSTP, and the U.S. Departments of State and Energy, should establish an interagency mechanism to coordinate federal efforts on textile circularity, reducing textile waste, and advancing textile recycling in the US. This interagency mechanism should identify and involve federal participants and should consider leading collaboration practices, including clearly defining common outcomes and identifying data and resource needs. (Recommendation 6)

The Assistant Administrator of EPA’s Office of Land and Emergency Management should identify and communicate federal financial resources (such as grants and other funding opportunities) and assistance that are available to encourage and support efforts by states, local governments, and organizations to reduce textile waste and advance textile recycling. (Recommendation 7)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the U.S. Departments of Commerce (NIST, ITA, and NOAA), Defense, Energy, and State; EPA; GSA; NSF; and OSTP for review and comment. OSTP provided comments, reproduced in appendix I, that it stated represent a consolidated response on behalf of OSTP, the Departments of Commerce’s NIST, Energy, and State, EPA, and NSF. These comments agree with our findings and conclusions but disagree with recommendations 1 through 6, which are identical but directed separately to the various agencies included in OSTP’s response. EPA also provided comments, reproduced in appendix II, agreeing with our findings, conclusions, and recommendations, including recommendation 7, which is directed solely to EPA. The Department of Defense and GSA did not provide comments on the draft report. We received technical comments from the Department of Commerce, which we incorporated as appropriate. OSTP’s and EPA’s comments are discussed below.