INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT AND JOBS ACT

DOT Should Better Communicate Funding Status and Assess Risks

Report to Congressional Addressees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Elizabeth Repko at RepkoE@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107166, a report to congressional addressees

INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT AND JOBS ACT

DOT Should Better Communicate Funding Status and Assess Risks

Why GAO Did This Study

DOT administers over 100 grant programs to provide billions of dollars each year to eligible entities to build highways, transit, and other infrastructure. DOT and grant recipients and awardees work to sign agreements, at which point DOT generally obligates the funding. If the grant funding is not obligated before the program’s statutory deadline, the funding becomes unavailable. Deadlines vary by program. While some do not have deadlines, others have a deadline as early as September 30, 2025.

In January 2025, the current administration issued an executive order to pause the disbursement of certain funds appropriated through the IIJA. As of April 2025, DOT is reviewing projects without signed discretionary grant agreements for alignment with administration priorities.

This report (1) assesses the status of IIJA grant funding as of April 2025, (2) identifies challenges grant awardees reported facing, and (3) evaluates DOT actions to assess risks posed by reported awardee challenges.

GAO analyzed DOT funding data from USAspending.gov as of April 2025 and surveyed awardees of 316 projects from December 2024 to March 2025 and interviewed DOT officials and funding awardees.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that DOT (1) communicate to Congress the amount of IIJA formula and discretionary grant funding obligated and outlayed and (2) assess and respond to risks posed by challenges faced by awardees. DOT concurred with both recommendations.

What GAO Found

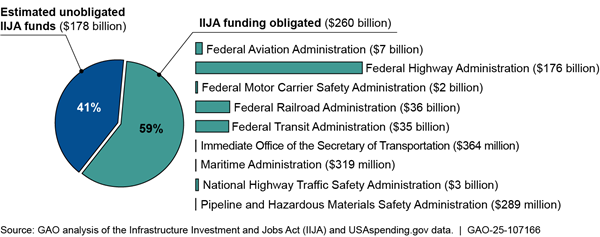

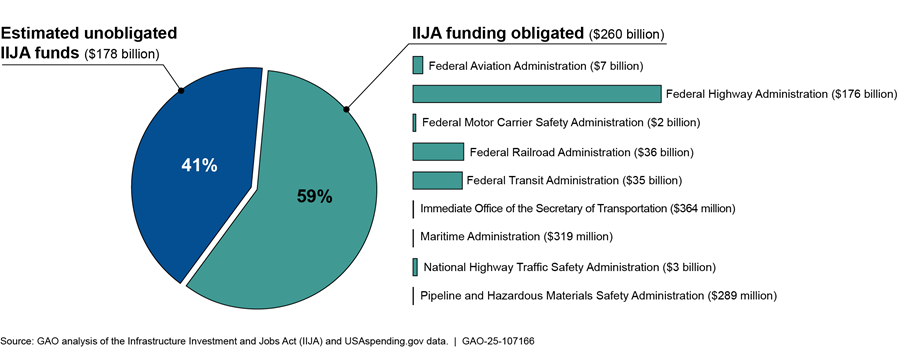

Enacted in 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) authorized and appropriated over $551 billion to the Department of Transportation (DOT) to provide grants to states, local governments, and other entities for transportation investments. As of April 2025, DOT has obligated 59 percent of its available IIJA funding and outlaid over half of that funding to recipients and awardees.

Notes: Where applicable, funding totals are rounded to the nearest billion or million. Some grant funding authorized or appropriated for the Office of the Secretary of Transportation is obligated and outlaid by other operating administrations in USAspending.gov and is accounted for in the data for those operating administrations in this figure. GAO estimated unobligated funds by subtracting obligated funding from the total funding made available for fiscal years 2022 through 2025. Unobligated funding is available for obligation as of April 2025.

While DOT has publicly reported some IIJA funding information, it has not provided complete information to Congress on the amounts of obligations and outlays for formula and discretionary grant programs in aggregate. Doing so could provide Congress with information on how these two funding types affect obligation and outlay rates. This would be valuable as Congress considers the mix of programs to fund in upcoming surface transportation legislation.

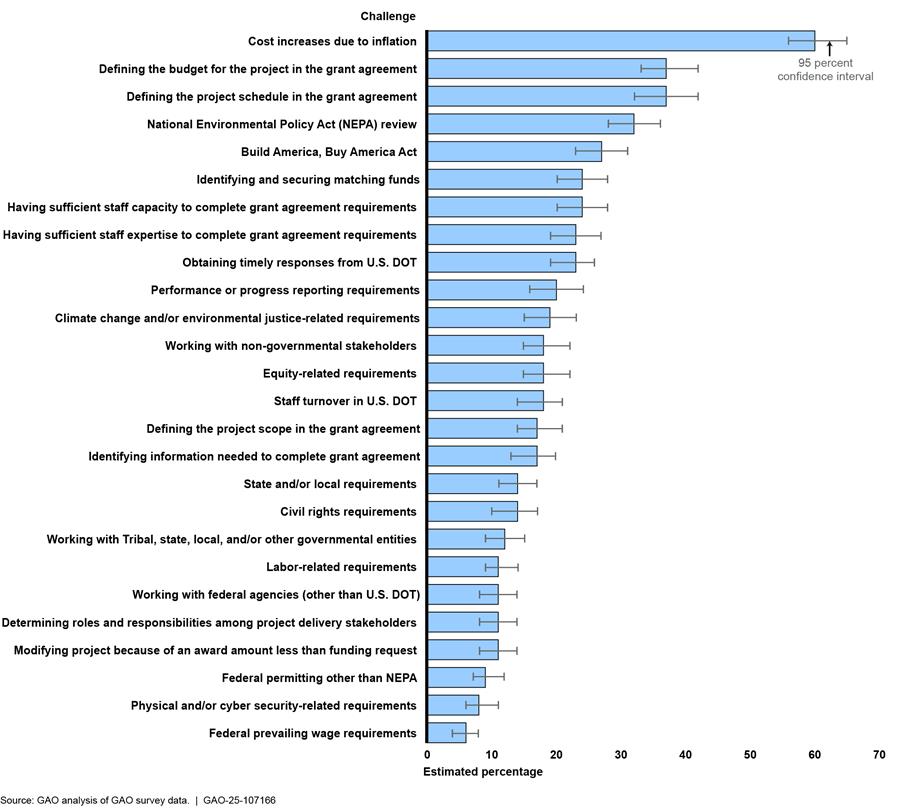

Based on GAO’s survey, discretionary grant awardees commonly experienced challenges with inflation cost increases; defining project budget and schedule; National Environmental Policy Act reviews; and Build America, Buy America Act requirements. These interrelated challenges create risks for awardees, including that funding will expire or no longer be available to the awardee. Approximately 23 percent of surveyed awardees for selected fiscal year 2022 discretionary grant programs reported that they did not have a signed grant agreement when they responded to GAO’s survey from December 2024 to March 2025.

DOT has not fully assessed the risks posed by challenges awardees cited to the efficient and effective delivery of IIJA funds. While DOT has taken some steps, it has not comprehensively identified risks, fully assessed their likelihood and impact, and monitored them. For example, efforts GAO reviewed assess risks for a single program or individual projects but do not look across DOT’s portfolio of grant programs. Fully assessing risks could help ensure that DOT has strategies to effectively address awardee challenges and guide DOT as it makes decisions about delivering the remaining billions in IIJA funding.

Abbreviations

|

AASHTO |

American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials |

|

BIP |

Bridge Investment Program |

|

BUILD |

Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development |

|

DATA Act |

Digital Accountability and Transparency Act of 2014 |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

FHWA |

Federal Highway Administration |

|

FRA |

Federal Railroad Administration |

|

FTA |

Federal Transit Administration |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

Low-No |

Low or No Emission (Bus) Grants |

|

MARAD |

Maritime Administration |

|

NEPA |

National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 |

|

NHCCI |

National Highway Construction Cost Index |

|

NSFLTP |

Nationally Significant Federal Lands and Tribal Projects Program |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OST |

Office of the Secretary of Transportation |

|

PIDP |

Port Infrastructure Development Program |

|

RAISE |

Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 24, 2025

Congressional Addressees

Enacted in 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) authorized and appropriated over $551 billion to the Department of Transportation (DOT) to make investments in highway, airport, maritime, transit and other projects through more than 100 grant programs—including around 35 new ones.[1] Most of this funding will be provided to eligible nonfederal recipients including Tribes, state departments of transportation, and local governments.[2] Under the IIJA, funding for DOT’s grant programs was authorized and appropriated for fiscal years 2022 through 2026, with specific funding amounts made available for each fiscal year.[3] DOT is responsible for distributing or awarding on average more than $100 billion in IIJA grant funding that becomes available each of those fiscal years, and working with those recipients and awardees well into the future as they develop and implement thousands of infrastructure projects nationwide.

DOT’s portfolio of more than 100 IIJA grant programs is generally designed to either distribute funding based on established formulas or award funding through competitions managed by DOT. Specifically, DOT and its component agencies (operating administrations) are responsible for administering approximately 36 IIJA formula grant programs through which DOT distributes funding annually to all eligible recipients through formulas set in statute.

To award grants through a competitive process, the operating administrations as well as DOT’s Office of the Secretary of Transportation, manage approximately 67 discretionary grant programs. These programs cover a wide range of transportation modes and eligible recipients. For discretionary grant programs, DOT announces the availability of funding, evaluates grant applications, and selects projects for grant awards for each award cycle.

Once projects are selected for award, DOT works with its portfolio of awardees to help them complete the steps necessary to reach a grant agreement so they can implement their projects.[4] Some DOT grant programs have statutory deadlines for signing an agreement to obligate funding.[5] If the awardees and DOT do not sign the agreements by these obligation deadlines, the funding either expires or becomes unavailable to the awardee, depending on the program.[6] For example, fiscal year 2022 Bridge Investment Program funding must be obligated by DOT by September 30, 2025, after which any unobligated funding for that fiscal year will expire.

The success of the IIJA in delivering transportation improvements nationwide hinges on DOT’s management of the approximately $551 billion in grant funding the act provides. In March 2022, DOT described the IIJA as “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to support transformational investments in our national transportation infrastructure.”[7] Now, several years after the IIJA’s enactment, Congress is beginning to draft legislation to authorize future surface transportation programs and make decisions about the types of grant programs to include in that legislation. Members of Congress have raised questions about differences in implementation between formula and discretionary grant programs, including the time it can take to sign grant agreements for discretionary grant programs.

In January 2025, the current administration issued executive orders directing federal agencies to review and take specified actions with respect to their programs.[8] This could affect the timing and distribution of funds. The executive orders included one to pause the disbursement of certain funds appropriated through the IIJA.[9] This executive order also directed federal agencies to review their processes, policies, and programs for issuing grants and other financial disbursements under the IIJA for consistency with the law and executive order. As of April 2025, DOT is reviewing all discretionary grant award selections for projects without signed grant agreements to ensure the project scopes align with executive orders and related DOT orders and memoranda. According to DOT officials, DOT is approving projects for obligation on a rolling basis as reviews are completed but does not yet have a timeline for completion of this review.

We performed our work on the initiative of the Comptroller General.[10] In this report we

1. assess the status of DOT’s IIJA grant funding, as of April 2025,

2. identify any challenges that funding awardees of selected discretionary grant programs reported facing in completing requirements to reach grant agreements, and

3. evaluate DOT actions to assess risks posed by reported awardee challenges.

For all objectives, we reviewed applicable statutes and regulations.

To assess the status of DOT’s IIJA grant funding, as of April 2025, we analyzed DOT IIJA funding data which we obtained from USAspending.gov in April 2025.[11] We analyzed data on IIJA award obligations and outlays, administering subagencies, assistance types, and the program activities funding each award.[12] We tested the quality of the data to assess the accuracy and completeness of the dataset. For example, we analyzed the data to ensure that no IIJA funding in USAspending.gov was obligated prior to the enactment of the IIJA, among other data tests. In addition, we interviewed the DOT officials knowledgeable of DOT’s submissions to USAspending.gov and DOT’s financial management systems. We also reviewed published reports from federal offices of inspectors general for information on the reliability of USAspending.gov data. We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for our purposes of assessing the status of DOT’s delivery of IIJA funding. However, we identified limitations with USAspending.gov data on assistance type, which we discuss later in this report. We compared DOT’s efforts to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, focusing on the principle of using quality information.[13] We did not assess the extent or results of DOT’s ongoing review of discretionary grant award selections.

To identify challenges funding awardees have faced in completing requirements to reach grant agreements, we surveyed and interviewed funding awardees. Specifically, we surveyed a generalizable sample of grant awardees for 316 projects selected to receive grants in the fiscal year 2022 funding round for six selected discretionary grant programs.[14] We surveyed awardees on challenges they faced in completing requirements to reach a grant agreement with DOT. We received a 68 percent response rate.[15] All survey results in this report are generalizable to awardees selected during the fiscal year 2022 funding rounds for our selected programs, unless presented as counts.[16] We conducted this survey from December 2024 until March 2025. We also interviewed 16 funding awardees selected in the fiscal year 2022 funding round for the six selected discretionary grant programs.[17] The experiences of these interviewees are not generalizable to all awardees.

To evaluate DOT actions to assess risks posed by reported awardee challenges, we reviewed DOT documentation and interviewed DOT officials with each of the six selected discretionary grant programs. We also interviewed the DOT officials responsible for working with awardees to reach grant agreements for projects funded by those programs. We compared DOT’s actions cited in those documents and interviews with information in DOT’s Strategic Plan and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, focusing on the principle on assessing and responding to risk.[18] See appendix I for more information about our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Summary of IIJA Funding

The IIJA provided funding for both DOT formula and discretionary grant programs. Under a formula grant program, DOT distributes funds to all eligible recipients using a statutory formula. Under a discretionary grant program, DOT awards funds to eligible recipients through a competitive process which can include DOT officials rating and selecting applications using statutory criteria.

DOT IIJA grant programs are administered by eight of DOT’s operating administrations and the Office of the Secretary of Transportation (OST). The operating administrations include the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA). OST and operating administrations share responsibilities for some programs. For example, OST conducts the application selection process for the Rural discretionary grant program while the operating administrations administer the awards (including signing the grant agreement and overseeing project implementation). For other discretionary grant programs, such as the Bridge Investment Program, FHWA conducts the application selection process, the Secretary of Transportation makes the selections, and FHWA administers the awards.

The IIJA authorized and appropriated more than $551 billion in total funding for DOT grant programs for fiscal years 2022 through 2026.[19] FHWA received the majority (61 percent) of all DOT IIJA grant funding (see table 1).

Table 1: Department of Transportation (DOT) IIJA Grant Funding Authorized and Appropriated (in billions of dollars) for Fiscal Years 2022-2026

|

Operating Administration/Office |

IIJA funding authorized and appropriated |

Operating administration IIJA funding as a percentage of total DOT IIJA funding |

|

Federal Highway Administration |

$335.5 |

61% |

|

Federal Transit Administration |

$90.4 |

16% |

|

Federal Railroad Administration |

$66.0 |

12% |

|

Office of the Secretary of Transportation |

$28.9 |

5% |

|

Federal Aviation Administration |

$20.0 |

4% |

|

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration |

$3.9 |

1% |

|

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration |

$3.2 |

1% |

|

Maritime Administration |

$2.3 |

0% |

|

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration |

$1.2 |

0% |

|

Total |

$551.4 |

100% |

Source: GAO analysis of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA). | GAO‑25‑107166

Notes: Where applicable, funding amounts are rounded to the nearest hundred million and also include authorized administrative takedowns and mandatory budget authority. Percentages are rounded to the nearest whole percent.

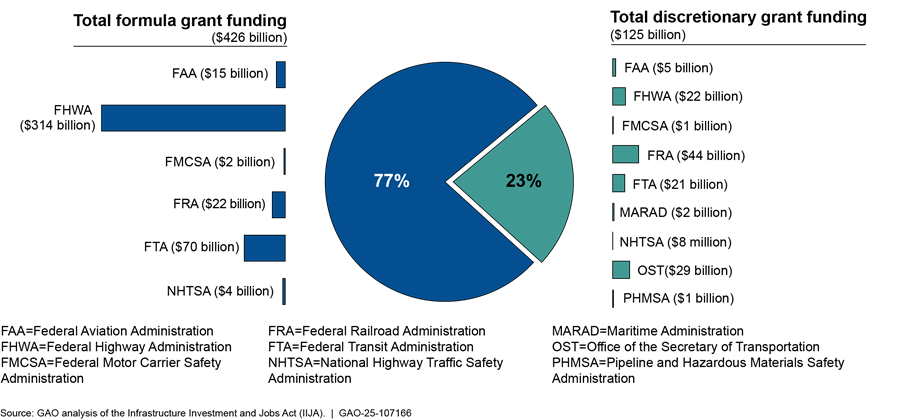

Most DOT funding authorized and appropriated under the IIJA is for formula programs. Over 77 percent (approximately $426 billion) of DOT IIJA grant funding is authorized and appropriated for formula grant programs compared with approximately 23 percent (approximately $125 billion) for discretionary grant programs (see fig. 1).

DOT is administering over 100 IIJA grant programs, including approximately 67 discretionary grant programs and 36 formula grant programs. FHWA and FTA administer the majority of DOT’s IIJA grant programs, with about 68 programs combined. FHWA accounts for almost $314 billion (approximately 74 percent) of DOT’s authorized and appropriated formula grant funding.

Figure 1: Authorized and Appropriated Department of Transportation IIJA Grant Funding, by Operating Administration and Grant Program Type for Fiscal Years 2022-2026

Notes: Where applicable, funding amounts are rounded to the nearest million or billion and also include authorized administrative takedowns and mandatory budget authority.

Formula grant funding amounts do not add up due to rounding.

Grant Process Overview

Grant funding follows a life cycle from statutory authorization or appropriation through grant closeout. Two key actions in this life cycle are obligation and outlay.

· An obligation is a definite commitment that creates a legal liability of the government for the payment of goods and services ordered or received.[20] An obligation may also be a legal duty on the part of the United States that could mature into a legal liability by virtue of actions on the part of the other party beyond the control of the United States. For the purposes of this report, DOT generally obligates funding when it signs a grant, project, or cooperative agreement (agreement) with a grant recipient.[21]

· An outlay is generally a payment made to liquidate a federal obligation.[22] An outlay occurs when DOT reimburses a grant recipient for the federal share of the costs of the project for which they signed a grant agreement.

Prior to using formula or receiving discretionary grant funding for their projects, formula grant recipients or discretionary grant awardees execute (i.e., sign) an agreement (specifically, a grant, project, or cooperative agreement) for the project with DOT. These agreements include the terms, conditions, and amount of the grant and obligate DOT to pay the federal share of the cost of the project. The agreements also outline the grant awardee’s planned use of the funds, such as the project scope, schedule, and costs for implementing the project.

Prior to signing a grant agreement, at which point DOT generally obligates the funding, DOT and awardees must satisfy the requirements of the grant program.[23] For example, DOT or awardees may be required to complete a review under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA), or awardees may be required to define the scope, schedule, and budget of the project.

Awardees may work with DOT staff in different locations during this process, depending on the program and operating administration. For example, the Maritime Administration (MARAD) administers awards for the Port Infrastructure Development Program (PIDP) out of its headquarters office in Washington, D.C.; FHWA generally administers Bridge Investment Program awards in its division offices located in each state throughout the country; and FTA administers awards for its Low or No Emission (Bus) Grants Program (Low-No) from its 10 regional offices.[24]

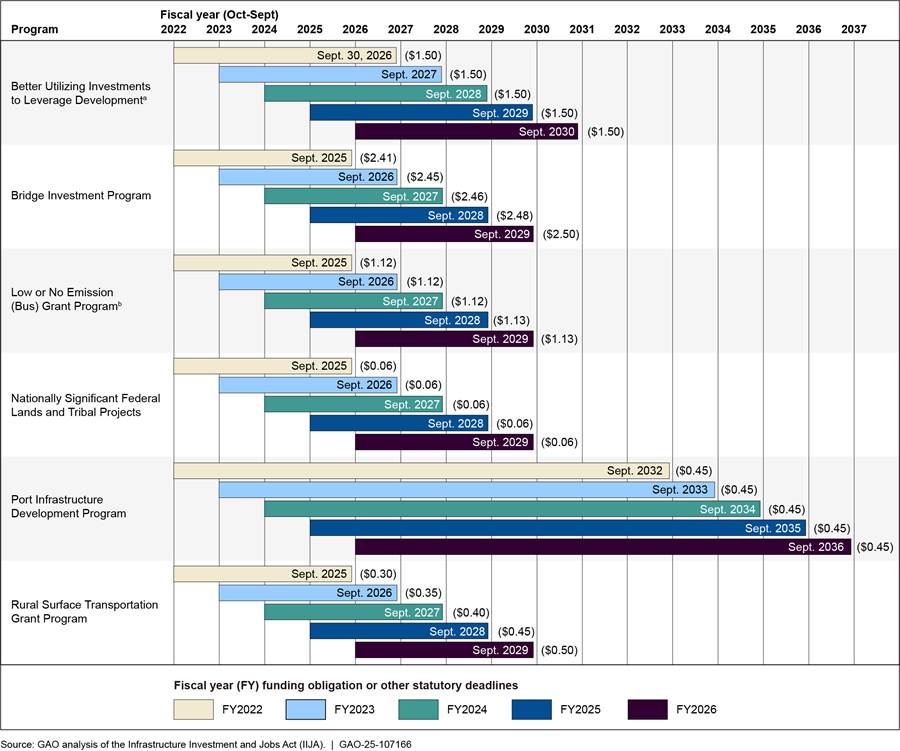

Each of our six selected grant programs has statutory deadlines by which awardees and DOT must sign a grant agreement.[25] These dates range from September 30, 2025, for some fiscal year 2022 funding, to September 30, 2036, for fiscal year 2026 PIDP funding. For our selected programs, the period of availability for DOT to obligate funding for each fiscal year funding round ranges from 4 to 11 years.[26] (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Statutory Deadlines for Signing a Grant Agreement for Selected Department of Transportation IIJA Grant Programs (funding in billions of dollars)

Notes: Funding amounts are the amounts authorized and appropriated under the IIJA. Where applicable, funding amounts are rounded to the nearest $10 million.

aBetter Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD) was formerly known as the Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) Discretionary Grant Program.

bFunding for the Low or No Emission (Bus) Grant Program does not have obligation deadlines, which are dates set by statute, after which unobligated program funding will expire. However, the program does have other statutory deadlines for signing a grant agreement, after which the awarded funding must be made available to another eligible project under the program. The dates listed for this program are those other statutory grant agreement deadlines.

DOT reports financial data about IIJA spending to USAspending.gov, which is the official source of federal spending information. USAspending.gov includes information about financial assistance, such as contracts, grants, and loans. It is intended to inform the public about how much the federal government spends every year and for what purposes. Statutes, regulations, and policies and guidance issued by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Department of the Treasury set out the requirements for monthly federal agency reporting to USAspending.gov.[27] These requirements include reporting certain financial data using a government-wide standard set of spending elements established by OMB and the Department of the Treasury. The spending elements include information about the recipient, the award amount and characteristics, and the awarding and funding entities.

DOT Has Obligated More Than Half of Available IIJA Grant Funding, as of April 2025, but Has Not Communicated Discretionary and Formula Grant Funding Amounts

DOT Has Obligated More Than $260 Billion in Available IIJA Grant Funding and Outlayed Over Half of That, as of April 2025

As of April 2025, DOT has obligated 59 percent of its available IIJA grant funding, according to our analysis of USAspending.gov. Specifically, DOT has obligated more than $260 billion of the almost $438 billion in grant funding authorized and appropriated for fiscal years 2022 through 2025 under the IIJA, as of April 2025.[28] Combined, three operating administrations—FHWA, FTA, and the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA)—obligated almost 95 percent of DOT’s obligated IIJA funding, as of April 2025. Of these operating administrations, FHWA obligated the largest amount of IIJA funding (see fig. 3). As of April 2025, DOT had yet to obligate almost $178 billion in available IIJA funding, about 41 percent of the almost $438 billion authorized and appropriated for fiscal years 2022 through 2025.[29]

Figure 3: Status of IIJA Grant Funding Available for the Department of Transportation for Fiscal Years 2022-2025 Available for Obligation, as of April 2025

Notes: Where applicable, funding totals are rounded to the nearest billion or million.

Some grant funding authorized or appropriated for the Office of the Secretary of Transportation, such as funding for Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development, is obligated and outlayed by other operating administrations in USAspending.gov and is accounted for in the data for those operating administrations in this figure.

Available funding includes authorized administrative takedowns.

We estimated the unobligated IIJA funds by subtracting the amount of IIJA grant funding DOT had obligated in USAspending.gov from the amount of total funding IIJA grant funding available for fiscal year 2022 through 2025 from our analysis of the IIJA.

Unobligated funding has not expired, as of April 2025.

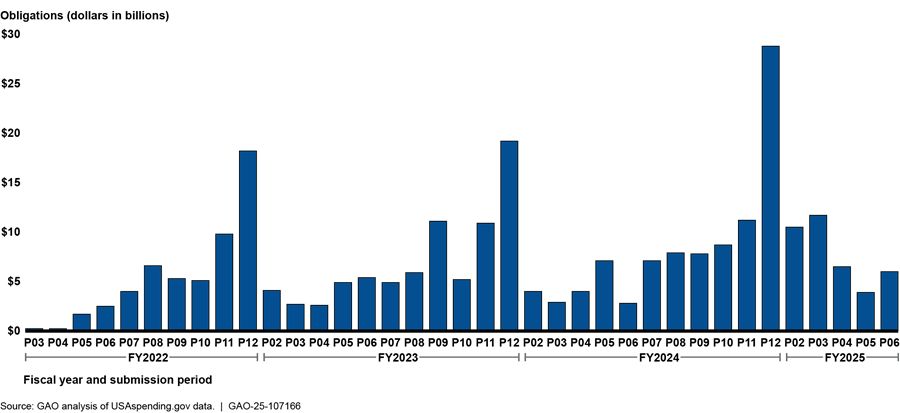

While the amount of obligated IIJA funding varies from month to month, DOT has obligated an increasing amount since fiscal year 2022. USAspending.gov reports obligations across 12 periods of the fiscal year, which coincide with months of the year. Obligations peaked in the final submission period of fiscal year 2024 (September 2024) when DOT obligated almost $29 billion, according to our analysis of USAspending.gov. This reflects a trend seen in previous fiscal years where DOT obligated the largest amount of funding in the final submission period of the fiscal year (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Department of Transportation Obligated Grant Funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act by Submission Period, Fiscal Years 2022 through 2025, as of April 2025

Note: USAspending.gov reports obligations across 12 periods of the fiscal year, which coincide with months of the year. USAspending.gov combines the first two submission periods of the fiscal year into P02.

Regarding outlays, DOT has outlayed over half of its obligated IIJA funding, as of April 2025, with FHWA having the highest outlay percentage. As of April 2025, DOT outlayed almost $135 billion in IIJA grant funding (52 percent of obligated funding), according to our analysis of USAspending.gov.[30] Four operating administrations—FHWA, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, FTA, and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration— outlayed more than half of the IIJA grant funding that they had obligated, as of April 2025, according to our analysis of USAspending.gov. (See table 2).

Table 2: Department of Transportation Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) Status of Grant Funding as of April 2025 (in billions of dollars)

|

Operating administration/office |

IIJA funding obligated |

IIJA funding outlayed |

IIJA outlays as a percentage of IIJA obligations |

|

Federal Highway Administration |

$176.1 |

$108.1 |

61% |

|

Federal Railroad Administration |

$35.7 |

$2.6 |

7% |

|

Federal Transit Administration |

$35.3 |

$17.8 |

51% |

|

Federal Aviation Administration |

$7.0 |

$3.3 |

48% |

|

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration |

$3.3 |

$1.8 |

53% |

|

Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration |

$1.8 |

$1.0 |

57% |

|

Office of the Secretary of Transportationa |

$0.4a |

$0.1a |

22%a |

|

Maritime Administration |

$0.3 |

$0.0b |

3% |

|

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration |

$0.3 |

$0.0b |

16% |

|

Total |

$260.2 |

$134.8 |

52% |

Source: GAO analysis of USAspending.gov data. | GAO‑25‑107166

Note: Funding totals are rounded to the nearest hundred million dollars.

aSome funding authorized or appropriated for the Office of the Secretary of Transportation is obligated and outlayed by other operating administrations in USAspending.gov.

bThe Maritime Administration and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration both outlayed less than $50 million.

Outlays are less than obligations due to the nature of DOT’s grant administration. According to DOT, DOT grant funds are not typically outlayed up front or in a lump sum but are generally obligated when an agreement is signed, which serves as a promise of future reimbursement. That is, DOT reimburses an awardee for the federal share of project costs after the awardee incurs those costs.[31] Project costs eligible for DOT reimbursement can include preliminary engineering, design, and construction.

Formula grant funding accounts for most of the obligated DOT IIJA funding. As of April 2025, at least 76 percent of DOT’s obligated IIJA funding has been formula grant funding, according to our analysis of USAspending.gov data.[32] Formula grant funding also accounts for the vast majority of grant funding DOT outlayed, as of April 2025. According to our analysis of USAspending.gov data, formula grant funding made up roughly 91 percent of all DOT outlayed IIJA funding, with FHWA outlaying approximately 79 percent of formula grant funding.[33] The substantial amounts obligated and outlayed by FHWA reflect the amount of formula grant funding provided in the IIJA, much of which FHWA oversees. As previously mentioned, 77 percent of grant funding authorized and appropriated under the IIJA for DOT grant programs was for formula grant programs. For example, the IIJA authorized over $273 billion in total for the federal-aid highway formula programs for fiscal years 2022 through 2026.[34] Two of these FHWA-administered formula programs, the National Highway Performance Program and the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program, alone accounted for at least 68 percent of DOT’s total outlayed IIJA formula grant funding, according to our analysis of USAspending.gov.[35]

While USAspending.gov has a variable for identifying formula grant funding, it does not include a variable to identify discretionary grant funding.[36] As a result, USAspending.gov cannot be used to report the amount of funding obligated or outlayed for DOT discretionary grant programs. DOT officials told us there is ongoing work on government-wide data standards that includes USAspending.gov.[37] This work may address how funding is categorized by specific variables in USAspending.gov, such as whether an award is a formula or project grant.

DOT Has Not Communicated Complete Information on the Amount of Formula and Discretionary Grant Funding

Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. It further states that quality information should be complete, among other attributes. Federal Internal Control Standards also state that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the agency’s objectives.[38] Quality information on the status of DOT formula and discretionary grant funding can provide policymakers with an understanding of the potential tradeoffs between the two, including the rate at which funding may be obligated or outlayed.[39] With this information, policymakers could more readily compare funding types and make more informed decisions about potential changes to funding. Such information could be particularly useful as Congress considers surface transportation reauthorization.

DOT officials told us they provide information to Congress on the status of formula and discretionary grant programs on an ad hoc basis at Congress’ request. For example, in December 2024, DOT provided Congress with several tables detailing IIJA funding. This included tables similar to reports that DOT posts on its website, known as its IIJA status of funds report, with data on the status of announced funding, obligations, and outlays by operating administration and budget account.[40] However, while these tables provide information on funding status at a high level, they are not complete as they exclude information on budget accounts that do not include discretionary programs. Further, the tables do not include a line item specifically aggregating formula or discretionary grant funding at the operating administration or DOT wide level. As such, the tables do not provide a direct comparison of the amount of obligated funding for formula and discretionary programs. Without such information, a policymaker cannot easily compare the two funding types to get a complete picture of IIJA obligations.

DOT has also collected data on the status of obligations for individual discretionary grant programs. For example, the BUILD/RAISE and Rural grant programs publish a report on their websites that details the status of the grant agreement for each awarded project. Additionally, DOT has established an internal tracking dashboard that provides information on the status of grant agreements for certain discretionary grant programs that could also indicate progress on obligations. However, while these sources cover some programs, they do not provide complete information on discretionary grant funding across DOT.[41]

DOT, by communicating complete information to Congress on the amount of obligations and outlays for DOT’s formula and discretionary grant programs, would provide Congress with quality information on DOT’s progress in delivering this funding to awardees. This information would be particularly useful in assessing the tradeoffs of formula and discretionary grant program funding, such as weighing the speed of signing agreements against targeting specific project types and recipients. As mentioned previously, Members of Congress have raised questions about differences in implementation between formula and discretionary grant programs, including the time it can take to sign grant agreements for discretionary grant programs. Information on the amount of obligations and outlays for formula and discretionary grant programs would provide Congress with information to help design programs for the next surface transportation reauthorization act based on the DOT’s experience administering IIJA grant programs.

Awardees Frequently Cited Challenges to Reaching a Discretionary Grant Agreement Including Inflation, Environmental Reviews, and Buy America Requirements

Awardees of our selected discretionary grant programs reported they experienced challenges while working to sign grant agreements.[42] Based on estimates from our survey, awardees frequently experienced the following as moderately or very challenging:

· cost increases due to inflation;

· defining the project budget;

· defining the project schedule;

· completing NEPA reviews; and

· meeting the Build America, Buy America Act or other federal domestic buying preference requirements.

Figure 5 shows the estimated percentage of awardees that found each of the above challenges to be moderately or very challenging, based on our survey.

Figure 5: Reported Challenges Faced by Selected Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) Discretionary Grant Program Awardees While Working to Sign a Grant Agreement

Note: We surveyed awardees of the Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD), Bridge Investment Program, Low or No Emission (Bus) Grant, Nationally Significant Federal Lands and Tribal Projects program, Port Infrastructure Development Program, and Rural Surface Transportation Grant Program that were selected in the fiscal year 2022 funding round. BUILD was formerly known as Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE).

The names of some challenges have been modified for this figure. For the full challenge names see appendix II. In addition, we asked about “other” challenges and provided a space for open ended responses.

Project cost inflation was the most frequently identified challenge. Based on our survey, an estimated 60 percent of awardees found inflation to be moderately or very challenging.[43] Moreover, some of these challenges are interrelated. One awardee in our survey reported that completing the NEPA review added many months to the grant agreement process and ultimately led to around a 30 percent project cost increase due to inflation. Based on our survey, an estimated 82 percent of awardees that found NEPA review to be moderately or very challenging also found inflation to be moderately or very challenging.[44] Further, we estimate 87 percent of awardees that found Build America, Buy America requirements to be moderately or very challenging also found inflation to be moderately or very challenging.[45]

These interrelated challenges may increase the risk that an awardee’s grant agreement will not be signed by the obligation or other statutory grant agreement deadline.[46] For example, if an awardee is experiencing challenges completing the NEPA review, this may extend the time until the awardee can sign the grant agreement. During this time, inflation may cause project costs to increase which could cause the awardee to have to redefine the project budget in the grant agreement.[47]

We spoke with selected awardees and reviewed other documentation to gain insight into the challenges surveyed awardees reported experiencing. Frequently experienced awardee challenges, based on our survey, include the following:

· Inflation (based on our survey, an estimated 60 percent of awardees found to be moderately or very challenging).[48] DOT statistics show the cost of construction materials increased from 2023 to 2024. According to the National Highway Construction Cost Index (NHCCI), as of the second quarter of 2024, the NHCCI saw a year-over-year increase of over 6.5 percent.[49] This means that what a dollar would have purchased in the highway construction industry in the second quarter of 2023, purchased about 6.5 percent less in the second quarter of 2024. According to DOT, the price of construction materials significantly diverged from the costs of other items in mid-2022. Between the second quarter of 2023 and the second quarter of 2024, construction costs increased over two times more than costs of household goods and services.[50]

Awardees provided insight into inflation challenges. One awardee said they were not expecting their grant agreement signing to take 2 years. Moreover, they noted that because of the time it took, they are uncertain if they will be able to complete the project as originally envisioned due to costs incurred. They said that if they had been aware of this potential timeline they would have added in more contingency funding into their initial budget. Another awardee told us that inflation costs incurred on their DOT funded project have affected other state funded projects.

· Defining the budget and schedule (estimated 37 percent of awardees found defining the budget and schedule to be moderately or very challenging, based on our survey).[51] A project’s budget and schedule may be impacted by the length of time it takes to sign a grant agreement. For example, one awardee stated that they had to alter the schedule of their project because the grant agreement process took longer than they expected. Because grant agreements may be signed years after the funding application is submitted, costs included in the project budget in the application may have increased by the time DOT and the awardee execute a grant agreement. One awardee noted that these changes to the project budget caused them to have to provide additional funds to make the budget whole. Based on our survey, identifying and securing matching funds was a commonly experienced challenge by awardees.

· NEPA reviews (estimated 32 percent of awardees found to be moderately or very challenging, based on our survey).[52] The NEPA review process can present challenges for awardees.[53] The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended, among other statutes, generally requires federal agencies to analyze and evaluate the environmental effects of their proposed actions.[54] Certain projects proposed for DOT funding are federal actions covered by NEPA and thus must undergo the NEPA review process.[55] NEPA provides that the federal agency determines the level of environmental review required under the act for the project.[56]

Awardees we spoke with or who responded to our survey identified challenges with NEPA reviews, including the scope and length of time it can take for federal agencies to complete their reviews. An awardee who started working with the operating administration environmental office on their NEPA review in early 2023 did not have a completed NEPA review when we spoke with them in August 2024. Without a completed NEPA review, the awardee said they cannot move forward with their grant agreement. This awardee said identifying acceptable mitigations to address environmental concerns raised by their project has been difficult. Another awardee mentioned the scope of the NEPA review as a challenge stating that the process required assembling 200 to 300-page documents for their projects and required public consultation.

Certain elements of NEPA, such as supplemental reviews and Section 106 can be challenging for awardees.[57] One awardee who completed a supplemental review described it as a “large lift” due to the many reports they had to complete and the financial plan they had to convert to a different format.[58] Another awardee experienced challenges related to the National Historic Preservation Act Section 106 review which, for their project, must conclude before the NEPA review can be completed.[59] As part of Section 106 reviews, DOT assesses potential adverse effects of the project on historic properties and then develops and evaluates alternatives or modifications to the project to avoid, minimize, or mitigate any potential adverse effects. The awardee said if an additional investigation is required for the project, it could lead to delays and a cost increase for the project.

· Build America, Buy America requirements (estimated 27 percent of awardees found to be moderately or very challenging, based on our survey).[60] Awardees of a few discretionary grant programs that we spoke with also identified issues with Build America, Buy America.[61] One awardee of a Port Infrastructure Development Program grant told us there is only one Build America, Buy America compliant supplier for port electric vehicles, which limits supplier competition. Fulfilling the Build America, Buy America requirement may increase this awardee’s project cost up to $1 million, according to the awardee.

We discussed these challenges with DOT officials, who stated that an awardee’s initial schedule may be unrealistic which may contribute to these challenges. The officials also said awardees can be optimistic in their proposals and misestimate when a project will be ready to move forward. For example, a recipient may not understand how long a NEPA review and acquiring matching funds can take. As noted above, awardees experienced challenges with identifying and securing matching funds (we estimate 24 percent experienced this challenge based on our survey).[62]

In addition, based on our survey, awardees experienced other challenges including having sufficient staff capacity to complete grant agreement requirements (an estimated 24 percent),[63] having sufficient staff expertise to complete grant agreement requirements (an estimated 23 percent),[64] obtaining timely responses from U.S. DOT (an estimated 23 percent),[65] and requirements related to performance or progress reporting (an estimated 20 percent).[66] Such challenges can affect awardees progress in reaching a grant agreement. For example, at the time they submitted our survey, 23 percent (49 of 213) of respondents indicated they did not have a signed grant agreement.[67] See appendix II for additional survey results.

DOT Has Taken Some Steps, But Not Fully Assessed Risks Posed by Awardee Reported Challenges

DOT Has Established a Technical Assistance Program Among Other Efforts to Address Awardee Challenges

DOT has sought to address awardee challenges by developing technical assistance, acting on environmental review challenges, and providing information on Build America, Buy America, among other efforts. Overall, based on our survey, awardees that sought assistance from DOT with their challenges found that DOT’s assistance was helpful. Specifically, an estimated 85 percent of awardees that sought assistance found DOT to be moderately or very helpful.[68]

· Technical assistance. DOT’s technical assistance includes a new program—Project Initiation Accelerator—developed to assist awardees at risk of not meeting federal grant goals or obligation deadlines. The program emerged from a pilot to provide technical assistance to three first time BUILD/RAISE awardees.[69] In February 2024, DOT estimated that the accelerator would assist approximately 50 OST awardees over a 2-year period. The accelerator assists awardees with project management, NEPA, and administrative and national policy requirements. As of March 2025, the accelerator had provided support to 11 grantees and completed technical assistance for four projects, according to DOT officials.

In addition to targeted technical assistance provided by the accelerator, DOT has also created websites that can help awardees. DOT’s Project Delivery Center of Excellence and Project Delivery Toolbox website provide resources for awardees on a range of topics including environmental review, public engagement, and civil rights compliance.[70] For example, the public engagement section includes links to DOT public engagement promising practices and operating administration and non-DOT resources on public engagement. A DOT official told us that the Project Delivery Center of Excellence resulted from a need to ensure DOT was thinking about cost containment and project delivery.

· Actions to address environmental review challenges. DOT has taken steps to address challenges related to environmental reviews.[71] For example, in 2024, DOT issued a report to Congress that identified best practices and procedures for the NEPA process.[72] These practices and procedures include establishing liaisons in other agencies, combining final environmental impact statements with records of decision, and combining operating administration regulations. In this report, DOT also identified seven strategies for accelerating the NEPA process along with the impediments those strategies address. One of these strategies is leveraging funding provided by the Inflation Reduction Act. FHWA received funding in the Inflation Reduction Act for environmental reviews. Specifically, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 appropriated $100 million for FHWA for the purpose of facilitating the development and review of environmental review documents for proposed surface transportation projects, including by building the environmental review capacity of nonfederal entities and providing guidance and technical assistance, among other things.[73] DOT’s August 2024 spend plan for this funding allocated roughly half of the funding for enhanced tools.[74] The spend plan says these tools are aimed at improving transparency and accelerating stakeholder and federal processes. The plan also allocated about $50 million across several areas: technical assistance to direct awardees, the Local and Tribal Technical Assistance Programs, and for liaisons at resource agencies.

Operating administration and program office staff have also sought to assist awardees with NEPA challenges. The PIDP program office hosted a webinar on project readiness which included information on NEPA. This webinar covered basic information on NEPA such as classes of action (e.g., categorical exclusion) and Section 106 consultation. Similarly, the BUILD/RAISE program office held a webinar that provided links to DOT NEPA resources, such as courses offered by the National Highway Institute and National Transit Institute.

· Actions to address Build America, Buy America challenges. Operating administrations have provided information on Build America, Buy America through their websites. For example, FHWA’s website provides Build America, Buy America guidance, information on waivers, and frequently asked questions. FTA and FRA also posted webinar slides on their websites. These webinars provided information on Build America, Buy America such as the materials subject to the requirements, information on the waiver process, and points of contact.

· Actions to address inflation. DOT officials told us DOT instructs applicants to include an inflation factor in total project cost estimates to cover inflation that may occur between the time applications are prepared and project selections are announced. Once project selections are announced, awardees will need to complete the requirements to reach a grant agreement. Further, addressing other challenges experienced by awardees could lessen the amount of time needed to reach a grant agreement, which could help mitigate the effects of inflation.

Unmitigated awardee challenges can pose risks to the successful completion of projects, including increased costs, schedule delays, and not meeting obligation or other statutory grant agreement deadlines.

DOT Has Not Comprehensively Assessed Risks Posed by Awardee Challenges

Federal Internal Control Standards state that federal agencies should assess, and respond to risks related to achieving the agencies’ defined objectives.[75] DOT’s fiscal year 2022-2026 strategic plan identified customer service as a strategic objective. Within this, DOT identified supporting the efficient and effective distribution of federal transportation funding as a strategy to achieve this objective.[76] Therefore, it is important for DOT to assess and respond to risks that could prevent awardees from reaching grant agreements.

While DOT has taken several steps to address awardee challenges, DOT has not fully assessed the risks to the efficient and effective delivery of funds posed by awardee challenges. Specifically, DOT’s efforts do not fully align with Federal Internal Control Standards that encourage federal agencies to comprehensively identify risks, assess their likelihood and impact, and monitor them moving forward.

Comprehensively Identify Risks

Federal Internal Control Standards encourage agencies to comprehensively identify risks by considering all significant interactions within the entity and within external parties, changes within the entity’s internal and external environment, and other internal or external factors. However, none of the efforts cited by DOT look across its portfolio of grant programs to assess risks, and DOT’s efforts to assess risks within individual programs have been limited.

For instance, in 2023 DOT analyzed obligated fiscal years 2018 and 2019 BUILD/RAISE awards and found that, on average, NEPA took 1 year to complete. DOT also found that other issues, including awardee funding shortfalls and right-of-way acquisition, took 6 to 7 months to resolve. However, this analysis falls short of a comprehensive identification of risks for several reasons:

· First, the analysis only looked at one program. While this analysis may help identify challenges that BUILD/RAISE awardees face, those challenges may not be applicable to awardees in other programs. Given that DOT administers approximately 67 discretionary grant programs funded under the IIJA, it is likely the challenges vary among programs. For example, based on our survey, an estimated 73 percent of Low or No Emission (Bus) Grants awardees found inflation to be moderately or very challenging.[77] In comparison, an estimated 56 percent of BUILD/RAISE awardees found inflation to be moderately or very challenging.[78]

· Second, within the analysis, DOT looked at over 30 BUILD/RAISE grants administered by FHWA. However, the analysis did not cover other operating administrations, such as MARAD or FTA, that also administer BUILD/RAISE grants. Assessments that look only at awardees in one operating administration or program could miss key risks in other operating administrations or programs.

Assess the Likelihood and Impact of Risks

Federal Internal Control Standards encourage agencies to estimate the significance of a risk by considering the magnitude of impact, likelihood of occurrence, and nature of the risk. DOT has taken steps to assess the likelihood and impact of project-level risks for individual programs and at some stages of the grant award process. However, these efforts are on a project or operating administration-specific level and do not comprehensively cover risks posed by awardee challenges.

Related to individual programs, MARAD has assessed the likelihood and impact of risks for PIDP projects. According to MARAD officials, MARAD conducts two risk assessments of PIDP awardees. The engineering risk assessment looks at the reasonableness of the project budget and timelines, through which MARAD officials identify the type of risk (such as delays in delivery times of construction materials and products), a mitigation strategy, and the likelihood and severity of the risk with the mitigation. These individual risks result in an overall project risk rating. The administrative risk assessment looks at topics such as the project manager’s experience. Other program and operating administration officials described meeting with recipients after selection to understand the status of projects. However, DOT has not consistently implemented a similar approach across its discretionary grant programs.

DOT also assesses risk at some stages of the grant award process. For instance, DOT assesses project-level risks before projects are selected for award but does not update these risks after selection. In each of the six discretionary grant programs we reviewed, DOT conducts project readiness reviews during the application review process to assess the likelihood of an applicant’s project completing environmental requirements to reach a grant agreement, among other things.[79] For example, in the fiscal year 2022 PIDP funding round, DOT officials rated applicants on their technical capacity and environmental risk. During the environmental risk assessment, according to the notice of funding opportunity, reviewers would independently assess the level of review the project required under NEPA and evaluate whether the applicant had demonstrated receipt of necessary environmental approvals, among other things. The review resulted in a rating of low risk, moderate risk, or high risk for the project. While this can be an effective initial step, the project readiness reviews capture the risk of the project in the application but may not reflect the risk of a selected project years after the applicant submitted the application.

By assessing the likelihood or impact of risks more broadly—such as by looking across its discretionary grant programs to assess whether any present a greater risk of not meeting program objectives—DOT and its operating administrations will be able to better prioritize its risk response to those programs facing the greatest risks.

Monitor Risks

Federal Internal Control Standards state that agencies may need to conduct periodic risk assessments to evaluate the effectiveness of the risk responses. Such assessments could be done through ongoing monitoring. DOT has existing processes that partially monitor risks and could be leveraged to more fully monitor risks. However, because DOT has not fully assessed risks to its IIJA discretionary grant programs, it does not yet have the necessary information to monitor them continuously moving forward.

Specifically, FHWA and FTA have a process to track the status of individual projects in reaching their grant agreements, and DOT has developed a dashboard to track projects more broadly, as previously discussed. FTA compiles a monthly report identifying funds at risk of lapsing and shares this with FTA regional offices. Additionally, FHWA officials told us they have developed their own tracking system which includes data on the status of grant agreement and amendments, among other things. While these systems could be useful to track the progress of grants, they are not based on a comprehensive set of risks with a likelihood and severity assessment to enable DOT to continuously monitor those risks.

Monitoring program risks is particularly important as conditions change, which may require managers to adjust their approaches to responding to risks. For example, in DOT’s 2023 analysis of BUILD/RAISE grants, DOT found that 31 of the 32 projects analyzed in the fiscal year 2019 funding round changed from when DOT selected the application to when DOT signed the grant agreement. Of these, 75 percent changed the budget, and 69 percent changed the completion date by 6 months or more.[80] Given that defining the project budget and schedule in the grant agreement were two commonly cited challenges among awardees, based on our survey, DOT would benefit from comprehensively monitoring the risk of projects after selection.

By conducting a comprehensive assessment of risks that looks across DOT’s programs and operating administrations, DOT will have more up to date information to guide its actions to respond to awardee challenges. Such an assessment could also help DOT identify changing conditions that could create future challenges.

A comprehensive assessment of IIJA program risks could also help DOT address challenges it has faced in administering its IIJA grant programs. Specifically, DOT officials we spoke with suggested that challenges related to NEPA could grow due to workload capacity and review complexity.[81] In particular:

· Workload capacity. A MARAD official involved in the NEPA review process told us that their current staffing is not sufficient.[82] In August 2024, this official said the MARAD environmental office had seven staff working on NEPA reviews. According to information provided by DOT in September 2024, MARAD had around 151 in progress NEPA reviews. Similarly, an FRA official also said that their operating administration has staffing challenges. They provided information which indicates that the environmental review workload per Environmental Protection Specialist has increased almost 83 percent since fiscal year 2019.

· Review complexity. One MARAD official said, over the past few years, most projects are environmental assessments or environmental impact statements and are very complex projects.[83] MARAD officials also said MARAD works on port projects, which generally involve sensitive environmental issues and require a high level of coordination with other federal agencies, which takes time. For example, MARAD officials told us they often coordinate with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Marine Fisheries Service, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on these reviews. An official with a different operating administration said that, with the IIJA, they have a lot of new awardees that have varying familiarity with NEPA. According to DOT, project sponsors that are unfamiliar with the NEPA process often require additional support and more time to navigate NEPA.[84]

In a March 2025 letter to the Secretary of Transportation, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) also raised concerns about DOT NEPA reviews.[85] In this letter, the President of AASHTO said, “Continued failure to advance standard environmental documents will result in missing the upcoming construction window altogether for many different types of investments, including critical Interstate Highway facilities.”[86] As mentioned above, delays in project schedules could lead to project cost increases and potentially pose risks for the efficient and effective delivery of funds.

If not fully assessed, the prevalence of these risks could increase as DOT awards more funding to grant awardees and its portfolio of projects grows. For example, we recently reported that DOT estimated that it will need to obligate over $74 billion annually in grants to Tribes, states, local jurisdictions, and territories from fiscal years 2025 through 2029 for its IIJA grant programs.[87] More fully assessing the risks posed by these challenges could help DOT to identify and prioritize the areas where assistance to awardees is most needed and effectively allocate resources to address those challenges.

Conclusions

The IIJA provided hundreds of billions of dollars in grant funding to construct and improve infrastructure and implement other projects throughout the country. DOT has collected data about the status of obligations and outlays for its IIJA programs but has not communicated complete information about formula and discretionary grants. Doing so would help policymakers understand how designing a program with formula versus discretionary grant funding could affect the efficiency with which funding is delivered. Moreover, such information could inform future surface transportation reauthorizations and help policymakers weigh tradeoffs when designing new, or revising existing programs.

In addition, DOT has an opportunity to assist grant recipients and awardees and ensure it effectively administers the approximately $551 billion in grant funding authorized and appropriated under the IIJA. The challenges reported by DOT and awardees in executing discretionary grant agreements could lead to projects with increased costs, reduced scope, and delayed delivery. As DOT moves into the final year of the reauthorization act, assessing the risks posed by challenges faced by awardees could help DOT better guide its technical assistance, such as targeting it to specific programs or operating administrations. A more thorough assessment of risks would better position DOT to meet its objective of efficiently and effectively delivering funding to awardees to ensure a safe and reliable transportation system.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to DOT:

The Secretary of Transportation should provide complete information to Congress on the amount of obligations and outlays for DOT’s IIJA formula and discretionary grant programs. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Transportation should assess the risks posed by challenges that IIJA awardees face in signing grant agreements and take steps to respond to those risks. Such an assessment should comprehensively identify risks, assess their likelihood and severity, and monitor them. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOT for review and comment. DOT concurred with both of our recommendations. DOT’s comments are reproduced in appendix III. DOT also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, and other interested parties. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at RepkoE@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Elizabeth Repko

Director, Physical Infrastructure

List of Addressees

The Honorable Susan Collins

Chair

The Honorable Patty Murray

Vice Chair

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Tim Scott

Chairman

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

Chairman

The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse

Ranking Member

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Cindy Hyde-Smith

Chair

The Honorable Kirsten Gillibrand

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The Honorable Steve Womack

Chairman

The Honorable James E. Clyburn

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Related

Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

We performed our work on the initiative of the Comptroller General.[88] In this report we (1) assess the status of the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) grant funding as of April 2025, (2) identify any challenges that funding awardees of selected discretionary grant programs faced in completing requirements to reach grant agreements, and (3) evaluate DOT actions to assess risks posed by reported awardee challenges.[89]

For all objectives, we reviewed applicable federal statutes and regulations. To identify the DOT grant programs that received funding under the IIJA, we reviewed the IIJA and statutes the act either referenced or amended for the grant programs we identified.[90] Through this review, we also determined and analyzed the amounts and types of funding that the IIJA provided for each DOT grant program we identified, as well as certain characteristics of those grant programs (e.g., formula or discretionary).[91] For each DOT grant program we identified, we further determined whether the program’s IIJA funding has obligation deadlines.[92] For each DOT discretionary grant program we identified, we also determined whether the program’s IIJA funding has other statutory grant agreement deadlines.[93]

To assess the status of DOT’s IIJA grant funding as of April 2025, we analyzed DOT IIJA funding data which we obtained from USAspending.gov.[94] We analyzed data on IIJA award obligations and outlays, administering subagencies, assistance types, and the program activities funding each award. We queried awards from USAspending.gov that had DOT identified as the awarding agency, grant funding as the award type, and the Disaster Emergency Fund Codes 1 or Z, which indicate that an award was funded through the IIJA. We included an approximation of the formula grant funding in USAspending.gov. To do so reliably, we tested the largest formula programs that make up almost 84 percent of all DOT IIJA formula grant funding in USAspending.gov. DOT had labeled over 98 percent of the obligations for these programs as formula grant obligations.

We calculated obligation and outlay amounts in this report using the “obligated_amount_from_IIJA_supplemental” and “outlayed_amount_from_IIJA_supplemental” data elements. We also analyzed federal account data to assess DOT IIJA obligations by submission period. We queried this data using the Disaster Emergency Fund Codes 1 and Z. We used DOT as the awarding agency to identify relevant awards. We used “submission_period” and “transaction_obligated _amount” data elements to calculate obligations by period. To assess the quality of these data, we tested the data to assess the accuracy and completeness of the dataset. For example, we analyzed the data to ensure that no IIJA funding in USAspending.gov was obligated prior to the enactment of the IIJA. In addition, we interviewed DOT officials knowledgeable about DOT’s submissions to USAspending.gov and DOT’s financial management systems. We also reviewed published reports from GAO and federal offices of inspectors general for information on the reliability of USAspending.gov data.[95] We found the data to be sufficiently reliable for our purposes. However, we identified limitations with USAspending.gov data on assistance type. For example, we identified more than $4 billion in Airport Infrastructure Grants IIJA obligations that were categorized under the project grant assistance type rather than the formula grant assistance type.[96] We brought this to DOT’s attention and, in May 2025, DOT officials told us they are reviewing their processes to classify IIJA Airport Infrastructure Grants as formula grants. We also identified $495 million in IIJA obligations from multiple discretionary grant programs that were incorrectly identified as formula grant funding in USAspending.gov. DOT corrected these awards and recategorized them as project grants after we brought the issue to DOT’s attention. We compared DOT’s efforts to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, focusing on the principle of using quality information.[97] This report does not assess the extent or results of DOT’s ongoing review of discretionary grant award selections.

To identify challenges that funding awardees have faced in completing requirements and to evaluate DOT actions to respond to awardee challenges, we selected six discretionary grant programs to review. These programs are (1) Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development, (2) the Bridge Investment Program, (3) Low or No Emission (Bus) Grants, (4) Nationally Significant Federal Lands and Tribal Projects, (5) Port Infrastructure Development Program, and (6) the Rural Surface Transportation grant program.[98] We selected these programs to obtain a variety of operating administrations, funding amounts, and types of awardees (e.g., Tribal government, state government). Our selection includes programs created in the IIJA as well as those that pre-date the IIJA. Finally, all of our selected programs have obligation or other statutory grant agreement deadlines.

To identify challenges that awardees have faced in completing requirements to reach grant agreements, we surveyed a generalizable sample of grant awardees for 316 projects selected to receive grants in the fiscal year 2022 funding round for our six selected discretionary grant programs.[99] We surveyed awardees on any challenges they faced in completing requirements to reach a grant agreement with DOT. We received a 68 percent response rate.[100] All survey results in this report are generalizable to awardees selected during the fiscal year 2022 funding rounds for our selected programs unless presented as counts.[101] We also interviewed 16 funding awardees selected in the fiscal year 2022 funding round for the six selected discretionary grant programs. We conducted semistructured interviews with two to three awardees from each of our selected programs to better understand awardees’ experience with the grant agreement process, including any challenges they faced. We selected awardees to obtain a variety of operating administrations, awardee types, locations, funding amounts, and grant agreement statuses (i.e., whether the awardee had a signed grant agreement with DOT).[102] The experiences of these interviewees are not generalizable to all awardees.

To evaluate DOT actions to assess risks posed by awardee challenges, we reviewed DOT documentation and interviewed DOT officials with each of the six selected discretionary grant programs. We also interviewed the DOT officials responsible for working with awardees to reach grant agreements for projects funded by those programs. We compared DOT’s actions with information in DOT’s Strategic Plan and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, Specifically, the principle on assessing and responding to risk.[103]

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Survey Development

To obtain the perspectives of awardees of Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) grant programs on any challenges they faced while working to reach grant agreements with the Department of Transportation (DOT), we developed and conducted a web-based survey.[104] We distributed our survey to entities that were selected to receive awards during the fiscal year 2022 funding round from six discretionary programs, providing each entity a unique survey link to a GAO operated website.[105] We conducted our survey from December 2024 to March 2025. We asked each selected awardee about their experience, focusing on the time after their award was announced to before they signed the grant agreement.

To develop the survey, we first selected six discretionary programs to focus our review on.[106] We selected the programs to obtain a variety of operating administrations, funding amounts, and types of awardees (e.g., tribal government, state government). Our selection includes programs created in the IIJA as well as those that predate the IIJA. Finally, all of our selected programs have obligation or other statutory grant agreement deadlines. We interviewed two to three awardees from each of these programs to better understand awardees’ experience with the grant agreement process, including any challenges they faced. We selected awardees to obtain variety of operating administrations, awardee types, locations, funding amounts, and grant agreement statuses (i.e., whether the awardee had a signed grant agreement with DOT). Based on the information obtained from these interviews and other sources, we developed an initial survey instrument. After we drafted and reviewed the initial survey, we pretested the instrument via web calls with five organizations to help ensure that questions were clear, answer choices were appropriate, and the survey was not burdensome. We revised the survey as appropriate following the pretests. Our survey included both closed and open-ended questions.

We selected a stratified sample of 316 projects out of 363 projects across our six programs.[107] We stratified our population into 16 strata consisting of each combination of operating administration (Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), Federal Transit Administration (FTA), and Maritime Administration (MARAD), program (BUILD/RAISE, PIDP, Low No, BIP, NSFLTP, and Rural), and grant type (Planning and Capital).[108] Assuming a 67 percent response rate, the sample size for each strata was calculated to allow us to produce percentage estimates having 95 percent confidence intervals no larger than +/- 10 percentage points at the strata level.

We distributed the survey to our sample between December 2024 and February 2025.[109] Following the distribution of the survey, we emailed awardees reminders about completing the survey to encourage responses. In early 2025, we called awardees who had not yet responded directly to confirm they had received the email with the survey link and further encourage responses. We closed the survey in March 2025 after receiving 213 responses, with a response rate of 68 percent. The estimates from our survey are generated by self-reported data by these respondents. We did not independently verify the responses.

We conducted a nonresponse bias analysis to identify significant factors associated with responding to the survey. We used these factors to develop weights to account for significant response patterns. Our nonresponse bias analysis developed a multivariate logistic regression model. We found the awardee characteristics of being from the northeast and south as the only significant factors associated with responding to the survey. We used the inverse of the predicted response probabilities from our multivariate logistic regression model as nonresponse adjusted weights. We had one strata with only one respondent, which made it difficult to measure within-stratum variance for that strata, so we applied a poststratification adjustment to the nonresponse adjusted weights that combined the strata with one respondent with another strata with similar characteristics. Survey estimation was done considering this modified design consisting of 13 of the original strata and one pseudo-strata.[110] We examined the sufficiency of the resulting final weights by examining frequency distribution and confirming that sum of the final weights added up to individual stratum level population totals and the overall awardee population total of 361.

We generated survey estimates using SAS’s Surveyfreq procedure and Taylor series linearization for variance estimation. We used the default Walt confidence limits when generating proportion estimates that were between .1 and .9. For estimated proportions that were less than .1 or higher than .9 we used Logit confidence limits. Survey results that were found to be unreliable due to a large margin of error or lack of respondents were labeled as unreliable. We also suppressed estimates that had five or fewer responses for data privacy concerns. Survey results are presented as estimates to the full population of awardees and have margins of error, at the 95 percent confidence level, of plus or minus 11 percentage points or fewer, unless otherwise noted.

Unless otherwise noted, all survey results in this appendix are generalizable to awardees selected during the fiscal year 2022 funding rounds for our selected programs.

Survey Results

Tables 3 through 25 provide questions from the survey and responses to the survey’s questions. Not all respondents answered each question. In some cases, based on survey design and responses provided, some questions were not applicable to certain respondents. Respondents may also have chosen not to answer some questions. In this appendix we are not reporting any responses to open-ended questions.

Grant Agreement Status Question

Table 3: Does Your Organization Have an Executed Grant Agreement for [PROJECT NAME], Which Was Selected to Receive a Fiscal Year 2022 [PROGRAM NAME] Grant, with the U.S. DOT or the Relevant Operating Administration?

|

Response |

Number of respondents |

|

Yes |

148 |

|

No |

49 |

|

Other |

11 |

|

Unsure |

- |

Source: GAO Survey of Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) Grant Program Awardees. | GAO‑25‑107166