MINE SAFETY

Commission That Reviews Legal Disputes Needs Improved Management Oversight

Report to the Chair, Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107171. For more information, contact Thomas Costa at CostaT@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107171, a report to the Chair, Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, U.S. Senate

Commission That Reviews Legal Disputes Needs Improved Management Oversight

Why GAO Did This Study

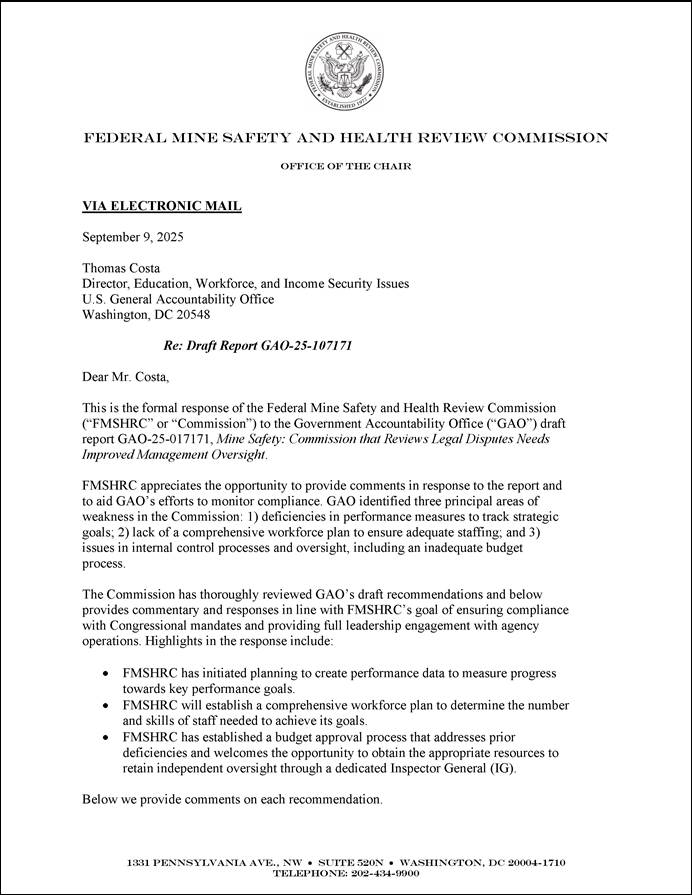

In 2024, about 327,000 miners worked at nearly 12,700 U.S. mines. By law, U.S. mines must undergo routine inspections to ensure they meet federal health and safety standards. The Commission reviews legal disputes about violations of these standards. It has an $18 million budget and about 60 employees.

GAO was asked to review the Commission’s operations and oversight. This report examines (1) how the Commission is addressing management weaknesses and (2) the challenges it has faced accessing independent oversight and options that exist to obtain support from an IG.

GAO reviewed Commission documents and external audits and interviewed agency officials and federal and industry stakeholders. GAO also assessed the Commission’s performance against relevant federal laws, regulations, and internal control standards. In addition, GAO interviewed several investigative agencies, IGs, and other federal stakeholders about strategies for agencies to access independent oversight.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Congress consider authorizing another agency’s IG to also serve as the Commission’s Inspector General. GAO is also making eight recommendations to the Commission to address management weaknesses, including those related to performance management, workforce planning, and other internal control deficiencies. The Commission agreed with GAO’s recommendations and described planned actions to address them.

What GAO Found

The Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission (Commission) has not addressed numerous management and operational weaknesses. According to senior officials, Commission leaders have often been disengaged from administering the Commission’s operations and have generally not addressed key challenges faced in carrying out its administrative functions. GAO identified a range of challenges, including:

· Agency performance management. The Commission has not fully incorporated key practices for managing its performance. Although it has established long-term goals in its strategic plan, the Commission does not have ways to measure progress toward most of those goals or consistently use reliable performance data to set new goals. Officials said that current and past Commission chairs were not fully aware of performance management requirements. As a result, the Commission is missing opportunities to improve its effectiveness and efficiency.

· Workforce planning. The Commission lacks a comprehensive workforce plan, which would help address the Commission’s operational challenges and future staffing needs. Officials acknowledged that the Commission lacks staff with human capital, financial, and other key skills, but it has not filled those gaps. The Commission also faced performance challenges due to several Administrative Law Judge retirements. One senior official told us the Commission lacks a succession plan even though all judges have been eligible to retire since 2022.

· Other internal control deficiencies. The Commission has not addressed several internal control deficiencies to improve its operations. For example, the Commission’s 2024 financial audit found an inadequate budget approval process, but a senior Commission official said the Commission could not fully address that deficiency without additional skilled personnel, and they do not have a plan to hire those personnel. In addition, the Commission has not established processes to manage its risks, ensure it is complying with relevant laws and regulations, or address other deficiencies.

Since 2021, the Commission has sought, with limited success, oversight for a variety of alleged improprieties and personnel matters. Many federal agencies have an Inspector General (IG) to investigate such allegations, but the Commission lacks an IG and instead sought assistance from several third parties. The Commission received limited investigative support from an external IG and the Office of Special Counsel. However, the Commission was unable to secure assistance to investigate allegations of improper procurement activities against a senior official, who remained on paid administrative leave for more than 3 years. Given the Commission’s challenges obtaining oversight support, it would benefit from having an IG designated in statute. The IG could be from a larger agency with related expertise and should be provided with appropriate resources to take on Commission oversight.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ALJ |

Administrative Law Judge |

|

CIGIE |

Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency |

|

Commission |

Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission |

|

COO |

Chief Operating Officer |

|

CSB |

U.S. Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FBI |

Federal Bureau of Investigation |

|

GPRA |

Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 |

|

GPRAMA |

GPRA Modernization Act of 2010 |

|

IG |

Inspector General |

|

Mine Act |

Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, as amended |

|

OGC |

Office of the General Counsel |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPIC |

Overseas Private Investment Corporation |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

OSC |

Office of Special Counsel |

|

USAID |

U.S. Agency for International Development |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 25, 2025

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

U.S. Senate

Dear Mr. Chair:

In 2024, over 327,000 miners worked at nearly 12,700 mines across the U.S. In the same year, 28 workers died in mining accidents. By law, U.S. mines must meet federal standards intended to promote the health and safety of mine workers and must undergo routine inspections to ensure compliance with these standards. The Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission (Commission) is a small, independent agency responsible for reviewing legal disputes about violations of mine safety and health standards. These disputes generally involve a review of enforcement actions taken by the Department of Labor’s Mine Safety and Health Administration, which include issuing citations or mine-closure orders and proposing civil penalties for violations of the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, as amended (Mine Act).[1] In fiscal year 2024, the Commission completed its review of more than 2,000 of these disputes.

In 2022, two senior Commission officials reported allegations of mismanagement by the head of the Commission to the U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions. These allegations included inappropriate policy changes and unreasonable personnel actions. The head of the Commission also reported to the Committee concerns about employee misconduct related to ethics and criminal violations. That same year, multiple Commission employees were placed on paid administrative leave; one employee, a senior officer in the Commission’s Office of the Executive Director, remained on paid leave for over 3 years. In addition, questions were raised about the Commission’s ability to obtain independent oversight, since it did not have an Inspector General to investigate the type of allegations that were raised.

You asked us to review the Commission’s operations and oversight. This report examines (1) how the Commission is addressing weaknesses, including those related to managing agency performance, budget and procurement, human capital, and internal controls; and (2) challenges the Commission has faced in accessing independent oversight, and what options exist to obtain support from an Inspector General.

To address the first objective about how the Commission is addressing management weaknesses, we reviewed Commission documents, particularly related to performance management activities, human capital operations, and financial management.[2] In addition, we reviewed third-party assessments of the Commission’s operations, including financial audits.[3] We spoke with each of the Commission’s senior leaders to obtain their perspectives on Commission operations, including any management weaknesses.[4] We also interviewed 14 employees across the Commission for their perspectives on operations and management.[5] We obtained information and collected documents from the Commission’s external stakeholders, including mine operators, a labor union, and the Department of Labor.[6]

We also reviewed selected past personnel actions, and we investigated selected allegations of wrongdoing related to the Commission’s past procurement activities. We evaluated the Commission’s efforts to address its management weaknesses against relevant federal laws and regulations, internal control standards, leading performance management and human capital practices, and the Commission’s own goals.[7]

To address our second objective about challenges the Commission has faced in obtaining independent oversight, we interviewed officials about the Commission’s efforts in this area and collected related documentation. We also interviewed officials from the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency (CIGIE), the Small Agency Council, and the Department of Labor’s Office of Inspector General for their perspectives on small agency operations and oversight.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Mission and Organizational Structure

The Commission provides administrative trial and appellate review of legal disputes under the Mine Act. According to the Commission, most of its cases involve the contest of civil penalties assessed against mine operators and address whether alleged safety and health violations occurred, as well as the appropriateness of proposed penalties. The Commission’s fiscal year 2024 budget was about $18 million. It employs about 60 full-time workers at its headquarters in Washington, D.C., and in satellite offices in Denver, Colorado, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The Commission has four organizational units (see table 1).[8]

|

Unit |

Description |

|

Office of the Chair and Commissioners |

Includes the chair, up to four other commissioners, and their immediate staff, such as confidential attorney advisors and assistants who support adjudication of appellate cases and various administrative duties. |

|

Office of the General Counsel |

Includes the General Counsel, Deputy General Counsel, and other attorneys who support appellate case adjudication—including providing advisory memos to commissioners and tracking the progress of cases. Attorneys may serve as counsel to an individual commissioner.a The office also provides legal support for agencywide programs, such as programs related to ethics and the Freedom of Information Act. |

|

Office of the Chief Administrative Law Judge |

Includes the Chief Administrative Law Judge (ALJ), all other ALJs, and staff such as supervisory attorneys, law clerks, and management analysts who support and track the agency’s adjudication of trial cases. |

|

Office of the Executive Director |

Includes the Executive Director and support staff who carry out various administrative functions for the agency, such as human resources, financial management, budget, procurement services, facilities, and information technology. |

Source: Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission officials and documents. | GAO‑25‑107171

aCommissioners have the option to have an Office of the General Counsel attorney advisor assigned to them as counsel in a part-time capacity or have the agency employ a full-time confidential attorney advisor as a political appointee to support their appellate duties.

When mine operators dispute the penalties, the Commission reviews the alleged violations and resulting penalties and makes a legal determination. Its decisions may be appealed in the relevant federal Court of Appeals.

The Commission carries out its mission through two levels of adjudication:

· Trial review by administrative law judges (ALJ). The Commission employs ALJs to hear and decide legal disputes under the Mine Act. ALJs evaluate and approve or deny settlement proposals between parties and, when necessary, conduct hearings. An ALJ’s decision becomes the Commission’s final order 40 days after its issuance unless within that time the Commission has directed that it will review the decision at the appellate level. In fiscal year 2024, the Commission received 1,877 new cases for trial review and its ALJs decided or approved settlements in 2,013 cases, according to its most recent Performance and Accountability Report.[9]

· Appellate review by commissioners. The Commission includes up to five commissioners who conduct appellate reviews.[10] The commissioners review ALJ decisions if (1) a party requests a review and two commissioners grant the review, or (2) two of the commissioners direct a case for review on their own initiative. In fiscal year 2024, the Commission granted reviews for 10 ALJ decisions and decided 12 such cases, according to its most recent Performance and Accountability Report. The commissioners also decide whether to reopen “default” cases for trial review, which are cases in which a mine operator has requested the Commission consider their case after they failed to meet a procedural deadline to dispute a proposed penalty or respond to an ALJ’s order. The Commission’s most recent Performance and Accountability Report said the Commission had 38 default cases pending review at the end of fiscal year 2024.

One of the commissioners serves as the Commission’s chair, who is responsible on behalf of the Commission for the administrative operations of the agency.[11] The Commission’s Chief Operating Officer (COO) oversees the agency’s daily operations and provides management guidance to the chair. The Office of the Executive Director’s responsibilities includes human resources, contracting and procurement for services such as court reporting, managing time and attendance, and federal reporting, such as annual performance and accountability reports, according to Commission officials. During the absence of the senior officer placed on leave in the Office of the Executive Director, the COO took on significant additional responsibilities, such as managing the Commission’s budget, information technology, facilities, and general administrative services.

Agency Performance Management and Enterprise Risk Management

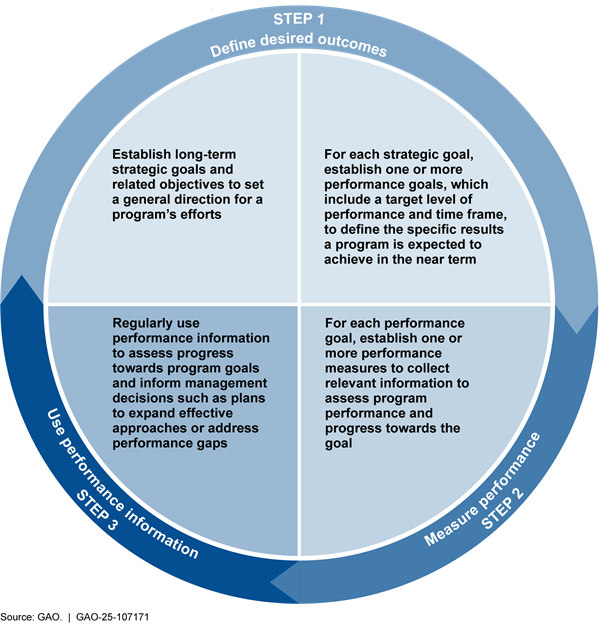

An agency’s strategic plan and related documents are key components of performance management, which involves measuring the agency’s progress toward pre-established goals. Our past work has defined performance management as a three-step process by which organizations (1) define desired outcomes, (2) measure performance, and (3) use performance information (see fig. 1).[12]

Various federal laws and guidance direct performance management activities across the federal government. For instance, the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (GPRA), as amended by the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010 (GPRAMA), generally requires federal agencies to issue strategic plans that include strategic goals and objectives for their major functions and operations.[13] Agencies are generally required to issue an annual performance plan that covers each program activity set forth in its budget.[14] In addition, agencies are generally required to assess their progress toward achieving goals and objectives through routine performance reviews.[15] The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) provides guidance to agencies on how to comply with GPRA and GPRAMA.[16]

Enterprise risk management is a forward-looking management approach that allows agencies to assess threats and opportunities that could affect the achievement of its goals. According to OMB, an effective enterprise risk management program should promote a common understanding of recognizing and describing potential risks that can affect an agency’s mission and the delivery of services to the public.[17] Such risks include strategic, market, cyber, legal, reputational, political, and a broad range of operational risks.

Federal Hiring Authorities and Agency Oversight

The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) is the federal government’s central personnel management agency that administers and enforces federal civil service laws, regulations, and rules. OPM has delegated many personnel decisions to federal agencies and encourages agencies to use human capital flexibilities, such as hiring authorities, to accomplish their missions. For example, in 1996, OPM delegated competitive examining authority to federal agencies for virtually all positions in the competitive service.[18]

OPM is responsible for ensuring that the personnel management functions it delegates to agencies are conducted in accordance with merit system principles and the standards established by OPM.[19] For example, OPM requires agencies to seek approval before they appoint current or recent political appointees to a permanent career position in the civil service to safeguard merit system principles and ensure fair and open competition that is free from political influence.[20]

The Office of Special Counsel (OSC) is an independent agency whose primary mission is to safeguard the merit system in federal employment by protecting employees and applicants for federal employment from prohibited personnel practices. Among other responsibilities, OSC investigates and prosecutes allegations of prohibited personnel practices. Individuals who believe that a prohibited personnel practice has been committed may file complaints with OSC. In some cases, if OPM finds evidence that an agency engaged in potential prohibited personnel practices, it refers the matter to OSC for additional investigation.[21]

Inspectors General

Inspectors General (IG) provide oversight for certain federal agencies.[22] As of February 2023, there were a total of 74 IGs established by law that operate across the federal government; IGs operate in Cabinet departments and larger executive branch agencies, as well as smaller entities such as certain boards and commissions.[23] IGs lead offices that generally operate as independent units within an agency. Their responsibilities include:

· conducting audits and investigations,

· promoting economy and efficiency in preventing and detecting fraud and abuse,

· reviewing existing and proposed legislation and regulations, and

· keeping the agency head and Congress informed about fraud and other serious problems.[24]

IGs are generally authorized to have access to agency records to perform their functions and responsibilities. IGs are also typically authorized to receive and investigate “whistleblower” complaints from agency employees about potential impropriety in agency programs and operations.[25] According to CIGIE, IGs maintain hotlines for individuals to report confidential information about potential fraud and abuse.

In the past, we have found that IGs play a critical role in federal oversight and all significant federal programs and entities should be subject to IG oversight.[26] We also reported some concerns about creating and maintaining small IG offices with limited resources, because a small IG office may not have the ability to maintain the technical skills and expertise needed to provide adequate and cost-effective oversight.[27]

The Commission Has Not Addressed Many Management Weaknesses, Including Gaps in Performance Management and Internal Controls

The Commission has many management weaknesses that it has

not addressed. The Commission is not able to measure progress toward achieving

most of its strategic goals. The Commission also has budget and procurement

oversight challenges and does not have a comprehensive strategic workforce plan

to guide its human capital program. In addition, the Commission has not

established a comprehensive enterprise risk management system and lacks a

comprehensive plan to address gaps it has identified in its internal control

system. Without leadership demonstrating a commitment to continuous

improvement, the Commission may not be able to address these key challenges.

The Commission Has Not Fully Incorporated Key Practices for Managing Its Performance

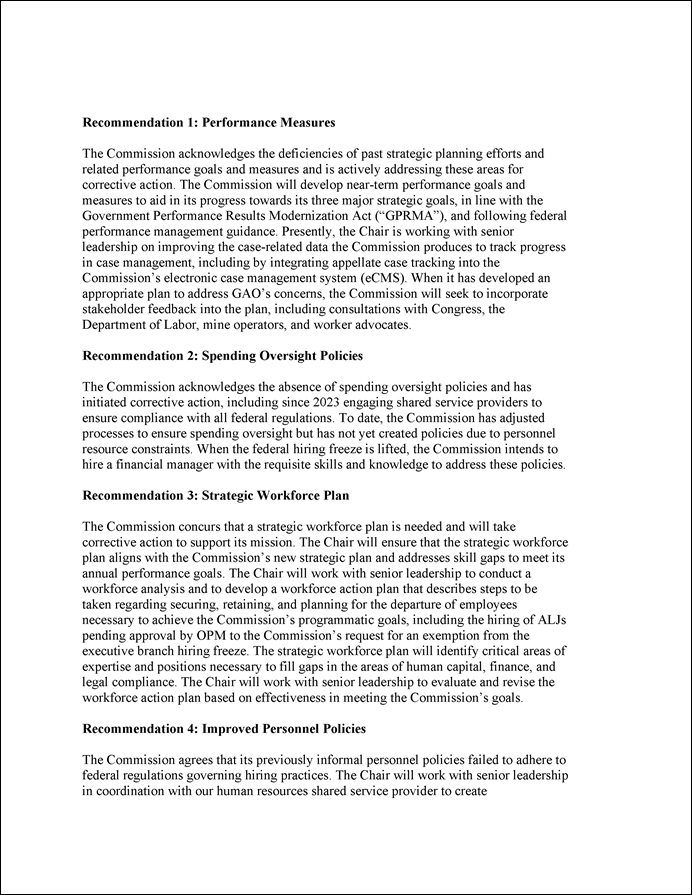

The Commission developed a strategic plan that includes three long-term goals; however, it has not fully established near-term performance goals or measures to assess progress toward achieving its strategic goals. When the Commission did measure progress, it did not ensure the reliability of some data used for those measurements. The Commission also did not consult with Congress or other stakeholders when developing its strategic plan, and it did not identify the resources required to achieve the goals it established in its strategic plan.

Goals and Performance Measures

Strategic and Performance Goals

The Commission’s first strategic goal is to ensure expeditious, fair, and legally sound case adjudication. To help achieve the first part of this strategic goal, the Commission established near-term performance goals for expeditious case adjudication, including average time frames for processing cases. The Commission defined a performance goal for how quickly the ALJs decide trial cases and a performance goal for the percentage of trial cases that are more than a year old. The Commission also created performance goals for how long it takes to decide appellate cases and a goal for the percentage of these cases that are older than 18 months.

The Commission’s first strategic goal also emphasized fair and legally sound case adjudication. However, the Commission did not define “fair” or “legally sound” with regard to case adjudication, establish related near-term performance goals, or develop a way to measure progress toward meeting these goals. As a result, the Commission is not able to measure the fairness and legal soundness of its case adjudication or assess its performance by comparing planned and actual results. Under GPRAMA, performance goals are a target level of performance expressed as a tangible, measurable objective, against which actual achievement can be compared.[28] The Commission acknowledged that it may not have complied with the relevant section of federal law and OMB guidelines and stated that it intends to ensure compliance going forward.

The Commission’s second strategic goal is to increase operational efficiency and effectiveness. This strategic goal does not include near-term performance goals to measure progress in meeting the strategic goal. The Commission did establish a related strategic objective to increase internal transparency by updating agencywide policies, such as those related to telework and employee onboarding and offboarding. However, according to officials, the Commission has not developed a way to measure progress towards this objective.

The Commission’s third strategic goal is to achieve organizational excellence through workforce development. This strategic goal also does not include near-term performance goals to measure progress in meeting the strategic goal. This strategic goal does include objectives that direct the Commission to improve talent management and promote work-life programs. However, one senior Commission official said they did not have ways to measure progress toward meeting these objectives, and two other senior officials said they were unfamiliar with them.

Data Reliability

For trial cases, the Commission uses an electronic case management system to capture the time it takes to process a case from when the case is received to when it is resolved, among other data. Commission officials said the system has checks for ensuring data reliability.

The Commission’s effort to track appellate cases, however, is informal and the resulting data may not be reliable. To collect appellate case data, the Commission uses what a senior official called the “old-fashioned paper and pencil method” to estimate the average time it takes to process appellate reviews of ALJ decisions. Specifically, according to the General Counsel, to report results for appellate case adjudication, he would estimate the average time it took to decide all the appellate cases without doing any calculations. He said that the Commission had no procedure for checking the quality of these appellate time frame estimates.[29] Two Commission officials questioned the reliability of the data, which were published in the most recent Performance and Accountability Report. That report does not describe how the Commission ensures the reliability of its data. However, GPRAMA requires agencies’ performance plans to describe how they ensure the accuracy and reliability of data used to measure progress towards performance goals.[30] These two officials said the Commission’s appellate data might be more effectively managed in the agency’s case management system to allow the agency to collect and track its case data in one system.[31]

Stakeholder Input

When developing its strategic plan, a senior Commission official said the Commission collected input from across its internal departments but did not consult with stakeholders, such as Congress, mine operators, the Department of Labor, or worker advocates and unions. GPRAMA requires federal agencies developing strategic plans to consult with Congress, including obtaining majority and minority views from the appropriate authorizing, appropriating, and oversight committees.[32]

We have previously reported that consultations with Congress are intended, in part, to ensure that agency performance information is useful for congressional oversight and decision-making.[33] Agencies are also required to solicit and consider the views and suggestions of entities that are potentially affected by or interested in the strategic plan. Commission officials said the Commission may not have complied with GPRAMA because it did not consult with Congress at least every 2 years on its strategic plan.

Resource Needs

The Commission’s strategic plan also does not consistently identify the resources needed to achieve its strategic goals. For example, to achieve its goal of timely appellate decisions, one strategy the Commission identified was to fill open positions in its Office of the General Counsel (OGC) as caseloads increased. However, according to officials, the Commission did not identify the resources it would need to fill those positions, nor did it identify what caseload increases would require filling an open OGC position. GPRAMA specifies that federal agencies should identify the resources required to achieve their goals in their strategic plans.[34] The Chair was not aware of this requirement, and the Commission historically had relied on the Office of the Executive Director, which lacked sufficient knowledge of the requirement.

Limited Use of Performance Information

The Commission has made limited use of the performance information it collects for its first strategic goal. It uses performance data on timely adjudication of trial and appellate cases to determine whether it has met its casework performance goals and publishes that data in its performance and accountability reports. Commission officials said that, on the trial side, the Chief ALJ discusses case data and processing times with ALJs and that the Commission uses performance data to adjust case assignments and allocate resources such as law clerks. Despite these efforts, five mine operators and a union of mine workers expressed concerns about case processing times at the trial level.

Likewise, for the Commission’s appeals, two senior Commission officials and Department of Labor officials told us they had concerns about the Commission’s lack of timeliness when processing default cases, among other appellate-level duties. At the end of fiscal year 2024, the Commission did not meet its goal for the percentage of default cases pending that had been on hand over 6 months, according to its 2024 Performance and Accountability Report.[35] According to officials, in July 2024, the Commission began addressing the default case backlog by assigning default cases to commissioners one at a time. Further, in July 2025, the Commission began to focus on achieving a lower average case age by using data to prioritize older cases.[36] The number of default cases has decreased significantly over the past several years, according to officials, from a high of 144 cases at the end of fiscal year 2020 to 33 in June 2025.

Two senior officials said, however, that the Commission was not using performance data to inform its strategy for establishing performance goals. Our guide on evidence-based policymaking suggests that agencies should use performance data to set new or revise existing goals, among other uses.[37] One senior official said that the Commission should assess whether the current performance goals are the most appropriate way to measure success. Officials said that Commission chairs were generally unaware of performance management requirements and were more focused on casework.

Overall, the Commission has not established a process to implement key performance management steps such as defining desired outcomes, reliably measuring performance, and consulting with Congress and relevant stakeholders. As a result, the Commission is missing key opportunities to inform its resource allocation and improve its effectiveness and efficiency.

The Commission Has Improved Some Aspects of Financial Management, but Challenges Remain

In fiscal year 2022, the Commission conducted an internal review of its budget and procurement system and found a lack of internal controls. The Commission then established certain basic controls, and a shared service provider helped it address several challenges with budget allocation, contracting, and purchase card use.

Budget Allocation

When the Commission reviewed its budget and procurement system, it found that it did not fully track its expenditures and funding needs, according to officials. To improve the accuracy of its accounting and provide better visibility into resources, in 2023 the Commission contracted with a shared service provider for full budget support, including budget execution reviews and projections.[38] For example, the service provider now reviews all transactions to ensure they are accounted for correctly and conducts detailed payroll projections, according to a senior Commission official.

Contracting

In 2021, a third-party procurement assessment found that the Commission did not follow certain Federal Acquisition Regulation requirements. For example, the assessment found that the Commission did not follow appropriate processes for competitive contracting and raised concerns about the training received by the staff performing contracting duties, among other shortcomings.[39] In 2023, the Commission expanded its contracting support through the same shared service provider it used for budget allocation services. According to a senior Commission official, this provider now conducts federally compliant procurement activities on the Commission’s behalf.

Purchase Cards

Before 2023, the Commission had not exercised appropriate oversight of its purchase card program, according to Commission officials. Based on allegations identified by Commission officials, we investigated the Commission’s use of purchase cards and found that Commission transactions were not always properly authorized or recorded. For example, we found that an employee in the Office of the Executive Director had signed paperwork to approve training purchases for the senior officer they reported to, including ethics training. That employee lacked authority to approve the purchases, according to a senior Commission official.

We also found that several purchase orders did not accurately record what was purchased. For example, in 2021 the Commission issued a purchase order for $125,000 for “Staff Training Reimbursement.” However, Commission officials said this record was not accurate, as no training was ultimately ordered or provided, and no money was disbursed. Our review of Commission records showed dozens of these purchase orders where money was obligated but subsequently not paid, totaling over $800,000 from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2024.[40] Officials acknowledged that training expenditures were approved without proper authority and problems occurred with inaccurate recording of items purchased through various orders.[41]

To address its purchase card challenges, in 2023 the Commission engaged the same shared service provider it used for budget support to oversee its purchase card program. The service provider now conducts external oversight of the Commission’s purchase card use, including ad hoc purchase audits to ensure compliance. The Commission also created a supply request form that requires multiple approvals. According to a senior Commission official, all purchases are now made through authorized vendors and tracked in a spreadsheet.

Despite improvements, the Commission continues to face challenges with financial management. For example:

· In June 2024, the Commission postponed an ALJ hearing because funding ran out on a contract that provided essential courtroom services, according to Commission officials.[42] ALJ hearings are a key mission function and are conducted so witnesses can testify on certain cases. In this instance, the Commission was unprepared for a budgeting shortfall because they had not tracked their use of contracted services, according to Commission officials. These officials told us the postponement caused significant scheduling problems for the attorneys and witnesses involved.

· The Commission occasionally loans its ALJs to serve as an ALJ at another agency where they may oversee hearings or settlement discussions.[43] According to a senior Commission official, due to poor internal financial administration, the Commission did not set up the necessary agreements with OPM and therefore the Commission’s shared service provider was unable to set up the proper accounting system to receive other agencies’ funding until late in fiscal year 2024.[44] As a result, the official said the Commission was unable to use about $100,000 in funds from the ALJs’ work.[45]

· From 2020 through 2024, the Commission had on average left more than $1.7 million—or nearly 10 percent—of its annual appropriated funds unspent, and twice left more than $2 million, according to the Commission’s annual financial statements. However, three officials told us that the Commission needs to hire personnel with human capital and budget expertise, among other needs, and a senior Commission official said that much of the unspent appropriation was supposed to be used to fill vacant positions. Two senior officials, in addition to the Chair, said the Chair was reluctant to hire staff until the Commission restructured its administrative functions.

A 2024 financial audit also found that Commission management did not have documented policies and procedures for significant financial processes and noted that there was no Chief Financial Officer. Further, the audit found that the Commission still needed to improve its contract approval process. It stated that the Commission was unable to show that it had appropriate budgetary approval before recording contractual obligations in its financial system across a sample of contracts totaling more than $1.7 million. The 2024 audit recommended that management obtain, document, and retain budgetary approval for each contract prior to obligation and that management establish internal policies and procedures for documenting the procurement process. The 2024 audit also noted that without appropriate budgetary approval, the Commission would be at risk of over-obligating funds, which could potentially result in a violation of the Antideficiency Act.[46]

The Commission concurred with the audit’s findings on the need for budgetary approval and procurement policies. In the Commission’s response to the 2024 audit recommendations, it said that it had made “substantial progress” in addressing related issues over the past 2 years. For example, the Commission said it had improved contract management processes in coordination with its shared service provider. However, the Commission said that the long-standing systemic issues resulting from improper historical contracting methods would require more time to remediate.

The Commission’s strategic plan notes that the proper administration of agency resources is key to the success of its mission. However, a senior official said the Commission did not have written policies to monitor how it spends its appropriated funds. Further, federal internal control standards state that management should obtain reliable financial data on a timely basis to enable effective monitoring. Without appropriate policies for monitoring how the Commission spends its appropriated funds, the Commission will not have assurance that funds are being used efficiently to accomplish its goals.

The Commission’s Human Capital Program Lacks Plans and Policies, and the Commission Has Taken Some Improper Hiring Actions

Inadequate Workforce Planning

We found multiple challenges that warrant strategic workforce planning. According to the COO, the Commission lacks a comprehensive strategic workforce plan to help it determine the number of staff and the skills and competencies it needs to achieve its goals. Rather, the Commission’s hiring efforts have generally focused on backfilling positions as vacancies arise. The Chair also acknowledged there had been several workforce challenges at the Commission, and she was unsure how to address them. In particular, the Commission has challenges with its ALJ and OGC staffing.

· ALJ staffing. The Commission recently faced challenges managing its trial-level performance due to several ALJ departures. As of September 2025, the Commission had five ALJs, down from eleven in 2022.[47] One ALJ retired in 2022 and another retired in 2023, leaving nine.[48] According to the Commission, after these retirements, the average time to process ALJ cases increased from 192 days in fiscal year 2023 to 225 days in fiscal year 2024.[49] Three more ALJs retired in January 2025, another retired in July 2025—leaving the Commission with five ALJs—and one more is expected to retire by the end of the calendar year.

Prior to these departures, an Office of the Chief Administrative Law Judge’s February 2020 analysis concluded that a range of 8 to 11 ALJs was required to meet its performance goals for processing trial cases. This analysis also noted that it may be prudent for the Commission to have more than the recommended number of ALJs on staff in the short term to lessen the impact of potentially losing several ALJs in a short period of time. Nonetheless, a senior official told us that the Commission lacked a formal succession plan to manage the risk of future ALJ retirements.[50]

Officials told us that the Office of the Chief Administrative Law Judge has made repeated requests to the current Chair to hire additional ALJs since 2022, including discussing new data and strategies in January 2024 in light of the possible retirement of several more ALJs. In November 2024, the Chair approved a request from the Office of the Chief Administrative Law Judge to hire three ALJs, but officials told us that the Commission was unable to begin the hiring process immediately due to a human capital records challenge.[51] Further, officials told us that the Commission is now subject to an executive branch hiring freeze and the process to hire ALJs can be lengthy. In a June 2025 letter to OPM, the Commission requested an exemption from the hiring freeze requirements to hire two new ALJs so it may fulfill its central mission, noting that it had a critical need to hire at least two ALJs to replace the five projected to be lost during 2025.[52] As of July 2025, a senior official told us that the Commission had not received a response from OPM to its request for an exemption from the executive branch hiring freeze to make new ALJ hires.

· OGC staffing. The Commission has no formalized workforce plan to determine OGC attorney staffing needs.[53] According to officials, OGC attorney advisors support appellate casework by creating advisory memos. Some OGC attorney advisors also serve as counsel to individual commissioners. Senior officials told us that this function was established decades ago when commissioners needed additional legal help to manage their caseload. Commission leadership has also assigned some duties to OGC staff to ensure that the Commission complies with relevant laws and regulations, though officials told us there were gaps in skills for obtaining compliance support for administrative matters. Some officials said that the Commission should reassess the duties assigned to OGC for fulfilling current needs.[54] A key principle of strategic workforce planning is to determine the skills and competencies that are needed to successfully achieve an agency’s missions and goals. Nonetheless, the Commission’s General Counsel told us there were no documented plans to determine the number of attorneys needed to address OGC’s workload or the distribution of grade levels for the positions.

In recent years, third-party assessments have identified other skill gaps in the Commission’s workforce, including in procurement and human capital management:

· The 2021 third-party procurement assessment recommended that the Commission hire an experienced contracting officer. According to officials, the Commission has since acquired additional contracting services from its shared service provider and a Commission administrative unit employee is being trained to conduct contracting activities.

· In 2022, OPM assessed the Commission’s staffing and concluded that its structure and administrative positions did not fully support its strategic plan. OPM found that some administrative positions were misclassified due to the Commission’s structure, low staff levels, and employee skill gaps. For example, OPM found that the Commission lacked staff to manage workforce planning and talent management. The Commission has not yet addressed these staffing gaps.

· In 2024, the Commission’s financial auditor found that the Commission had delegated authority and responsibilities to certain employees who lacked the appropriate qualifications, training, and experience needed to competently perform the functions outlined in their scope of work.

The COO said she generally agreed with the findings from these assessments and has sought to fill some positions, including a human capital specialist and a finance director. The Chair said she agreed that the Commission needed additional administrative support staff, though she had refrained from approving any new hires for administrative operations until a sensitive personnel matter in the administrative unit was resolved.[55]

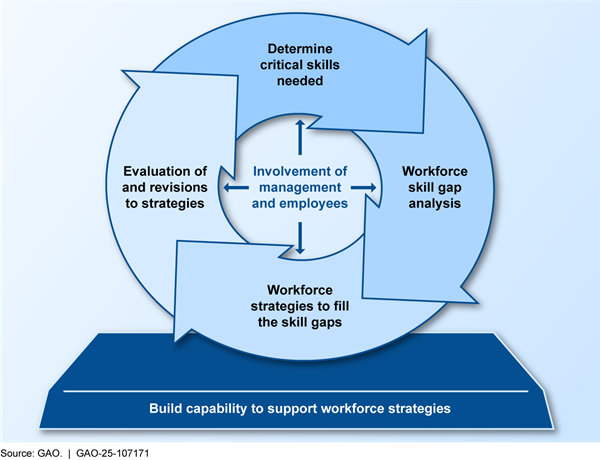

Strategic workforce planning addresses two critical needs: (1) aligning an agency’s human capital program with its current and emerging mission and programmatic goals and (2) developing long-term strategies for acquiring, developing, and retaining staff to achieve an agency’s programmatic goals.[56] As we have previously reported, workforce planning can assist federal agencies in achieving their missions and strategic goals (see fig. 2).[57]

According to federal internal control standards, agency management should continually assess the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed for the agency to secure a qualified workforce that can help achieve its organizational goals.[58] Management should also consider how best to retain valuable employees, plan for their eventual departure, and maintain continuity by hiring employees with the skills and abilities the agency needs.

A goal in the Commission’s strategic plan is to achieve organizational excellence through workforce development, which in turn supports the Commission’s goal to increase its overall operational efficiency and effectiveness. The Commission’s COO said that a workforce plan would be beneficial, though she said she had not had the resources to create one. This is in part because she had been carrying out the responsibilities of a senior officer in the Office of the Executive Director for several years while that officer was on administrative leave.[59] With a strategic workforce plan that identifies critical areas of expertise, the Commission could employ an agencywide human capital strategy to address its current operational challenges and future staffing needs.

Informal Hiring Practices and Improper Hiring Actions

The COO told us the Commission has few documented hiring and promotion policies. Only the Office of the Chief Administrative Law Judge has hiring policies for its positions, though the ALJ hiring policy has remained in draft form for several years.[60] The General Counsel told us the process for promoting individuals in his office was largely informal; when some OGC staff were recently promoted, the Commission did not announce any vacancies or solicit application materials.[61] Officials could not provide a reason for the Commission’s lack of hiring and promotion policies, though the head of one office said they understood it to be the responsibility of the Commission’s administrative unit to ensure that personnel actions complied with relevant laws and regulations.

Several employees we spoke with perceived that favoritism had guided certain hiring and promotion actions in multiple Commission offices. According to the Merit Systems Protection Board, perceptions of favoritism have the potential to lower employee satisfaction and negatively affect an agency’s performance.[62]

Certain personnel actions at the Commission also may not have followed relevant federal authorities governing civil service appointments, particularly related to fair and open competition when applying merit-based selection requirements. Examples include:

· Temporary appointments of former commissioners. Since 2008, the Commission has appointed seven former commissioners to temporary advisor positions after their terms expired (see table 2). A senior official told us these positions were generally for former commissioners who had been renominated and were awaiting Senate confirmation. One commissioner we spoke with said that the Commission made these temporary appointments to prevent a break in pay and benefits.

Table 2: Temporary Advisor Appointments of Former Commissioners at the Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission (Commission)

|

Individual |

Preceding commissioner term duration |

Temporary advisor appointment duration |

Employment action following temporary advisor appointment |

|

Former Commissioner A |

Aug. 2006 to Dec. 2007 |

Jan. 2008 to Mar. 2008 |

Reappointed as a commissioner in Mar. 2008 |

|

Former Commissioner B |

Aug. 2003 to Aug. 2008 |

Aug. 2008 to Oct. 2008 |

Reappointed as a commissioner in Oct. 2008 |

|

Oct. 2008 to Aug. 2014 |

Aug. 2014 to Apr. 2015 |

Reappointed as a commissioner in Apr. 2015 |

|

|

Apr. 2015 to Aug. 2020 |

Aug. 2020 to Oct. 2022 |

Reappointed as a commissioner in Oct. 2022 |

|

|

Former Commissioner C |

Aug. 2003 to Aug. 2008 |

Aug. 2008 to Oct. 2008 |

Reappointed as a commissioner in Oct. 2008 |

|

Oct. 2008 to Aug. 2014 |

Aug. 2014 to Apr. 2015 |

Reappointed as a commissioner in Apr. 2015 |

|

|

Apr. 2015 to Aug. 2020 |

Aug. 2020 to Jan. 2021 |

Appointed as a Commission administrative law judge in Jan. 2021 |

|

|

Former Commissioner D |

Apr. 2008 to Aug. 2012 |

Aug. 2012 to Aug. 2013 |

Reappointed as a commissioner in Aug. 2013 |

|

Former Commissioner E |

May 2010 to Aug. 2016 |

Aug. 2016 to Aug. 2018 |

Retired in Aug. 2018 |

|

Former Commissioner F |

Aug. 2013 to Aug. 2018 |

Aug. 2018 to Mar. 2019 |

Reappointed as a commissioner in Mar. 2019 |

|

Former Commissioner G |

Mar. 2019 to Aug. 2024 |

Aug. 2024 to present |

N/A |

Source: Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission documentation. | GAO‑25‑107171

Note: Individuals may have served as the Commission’s chair during a preceding commissioner term. The Commission has up to five commissioners who are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Commissioners serve 6-year terms, and vacancies can be filled only for the remainder of a term. 30 U.S.C. § 823(a), (b)(1).

Commission personnel records indicate that two of the commissioners held multiple temporary appointments during this period and some of the appointments lasted more than a year. According to the Commission, it may not have complied with relevant federal law with respect to many of these appointments, since it appears it granted an unauthorized preference to the former commissioners.[63] Commission officials said they recently modified their approach to providing former commissioners with temporary appointments. In 2024, the Commission received OPM’s approval to appoint a former commissioner to a temporary position that did not require a competitive selection process.[64]

· Career appointments of former contractors. In 2021, the Commission appointed three individuals to federal career positions who had previously been contractors in the Office of the Chief Administrative Law Judge.[65] Prior to the selection process, Commission records indicate that management said it would approve of filling the vacancies only with contractors who were conducting work at the Commission. For the search, the Commission posted job announcements for two locations and at two position levels for each location, resulting in four ranked lists of qualified candidates. Three of the lists contained veterans who ranked higher than the contractors. To make their selections, Commission officials used the only list with no veterans on it to hire the three contractors for the positions. The Commission said that the agency may not have complied with relevant federal law with regard to these individuals because it may have granted an unauthorized preference to the contractors.[66]

In addition, one of the hired contractors did not work at the worksite indicated on the list from which they were selected. Commission records indicate that from August 2021 until May 2023 the Commission paid the employee based on the locality pay rate that corresponded to the incorrect worksite, rather than a lower locality pay rate that corresponded to the employee’s actual worksite.[67] The Commission acknowledged that it may not have complied with relevant locality pay regulations with regard to this employee. Officials also told us that Commission records did not indicate whether any overpayments to the employee were recovered, and they were not able to find more information about the matter.[68]

· Appointment of a political appointee to a career position. In 2020, the Commission appointed a political appointee to a career position.[69] According to OPM, the Commission was required to obtain OPM’s approval before appointing a current or recent political appointee to a career position and had not done so. In 2022, OPM reviewed the appointment at the Commission’s request and said it could not conclude that the selection conformed with merit system principles or was free from political influence or favoritism. OPM ordered the Commission to correct the improper appointment and referred the matter to OSC for further investigation. The appointed individual subsequently left the Commission. According to Commission officials, OSC briefed the Commission on the findings from its investigation in 2024 and said that the Commission engaged in prohibited personnel practices regarding this appointment.

According to OPM, agency policies that describe procedures for how to handle job applications help ensure agencies adhere to the merit system principle of fair and open competition. Agency policies for certain hiring authorities provide a stronger foundation for compliance when they convey detailed instructions on how employees will carry out relevant laws and regulations. These policies should include (1) general hiring requirements and procedures, (2) guidance on applying relevant legal authorities, and (3) dated approvals.[70] Comprehensive hiring policies, including for internal promotions, can help the Commission ensure it complies with legal requirements and selects the most qualified candidates for open positions. In addition, documented hiring policies can help ensure that an agency retains organizational knowledge, and that this knowledge is not limited to a few personnel.[71] Establishing documented policies can also provide more transparency to Commission staff and help mitigate perceptions of favoritism.[72]

The Commission Has Deficiencies in Its Internal Control System and Lacks Comprehensive Plans to Address Them

The Commission has not properly established procedures to manage its risks, comply with relevant laws, or address other internal control deficiencies. As a result, the Commission does not have controls in place to manage challenges to achieving its goals and objectives, it has gaps in its internal control systems, and it does not have a comprehensive plan to correct identified deficiencies.

Enterprise Risk Management

The Commission has not taken steps to comprehensively manage risk across the agency. According to officials, during the Commission’s most recent strategic planning cycle, it did not formally assess or manage risk or establish a comprehensive structure for implementing a robust enterprise risk management process. Officials told us that the Commission had taken initial steps to assess risk, though it needed to fill key roles to set up effective oversight mechanisms.[73] The Commission’s 2024 financial audit stated that the Commission needs to improve its agencywide control policies and procedures, including those related to risk assessment. The audit also stated that the Commission’s lack of documented policies and procedures imperils its ability to identify and respond to risk.

Under OMB Circular No. A-11 and No. A-123, agencies should coordinate the implementation of their enterprise risk management capability that assesses and manages risk as part of their strategic planning and review process. We have reported that enterprise risk management allows agencies to assess threats and opportunities that could affect the achievement of their goals, and we identified essential elements of enterprise risk management.[74] Commission officials acknowledged that the Commission did not fully follow relevant OMB guidance for enterprise risk management; specifically, it did not have comprehensive risk management or establish an effective governance structure to manage risk. Officials told us that they had begun to address these concerns. By establishing a comprehensive enterprise risk management program, the Commission will be better able to determine the most significant risks to achieving its goals and prioritize how to use its resources to address them.

Compliance

The Commission has gaps in its internal control system for assuring it complies with relevant laws and regulations. For example, the 2021 third-party procurement assessment found that the Commission did not adhere to certain Federal Acquisition Regulation requirements. In addition, Commission officials told us that they may not have complied with applicable law for several hiring actions, including some as recent as 2021. Officials also said the Commission had not complied with the law when it did not conduct employee surveys in 2023 or 2024.[75]

Commission management acknowledged that the Commission may have deficiencies in ensuring compliance across its operations, particularly for the areas of human capital, procurement, and financial management. Officials told us that the Commission historically relied on the Office of the Executive Director to ensure compliance in administrative areas, though multiple senior officials said they now realize that the Office of the Executive Director did not have the relevant expertise for this work.[76] In 2021, the Commission hired a COO to oversee its administrative functions. The COO told us she established compliance controls and cited the Commission’s administrative shared service providers as one resource for obtaining compliance assistance in administrative matters. Nonetheless, the COO noted that additional expertise is needed to ensure compliance.

The Commission’s OGC plays a role in some compliance initiatives, including administering the Commission’s ethics and Freedom of Information Act programs. However, senior officials in OGC told us they generally do not advise Commission leadership on compliance with administrative matters. These officials told us that the Commission does not have staff attorneys with the specific skills needed to ensure that Commission operations are compliant with certain relevant laws and regulations, including those relating to hiring, procurement, and financial management.

Two commissioners told us that they recently took time away from their appellate work to provide legal services for a sensitive personnel matter and noted it would be a better use of the Commission’s resources to assign such duties to staff attorneys, such as those in OGC. One current and another former commissioner said that it would benefit the Commission to review whether OGC should be assigned duties to advise it on legal compliance with administrative matters such as hiring and termination. Officials from the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission, a similarly sized and tasked agency, told us that it assigns these types of duties to its OGC staff to ensure compliance with laws and regulations. According to federal internal control standards, management should assign responsibilities to discrete units within an agency’s organizational structure to ensure the agency complies with applicable laws and regulations. Further, management should consider how units interact to fulfill their overall responsibilities and determine what key roles are needed to fulfill a unit’s assigned responsibilities.[77] If the Commission assigns compliance responsibilities to specific personnel, it will be better positioned to address its compliance challenges.

Internal Control Deficiencies and Corrective Action

The Commission has identified many deficiencies in its internal control system, particularly through third-party assessments, though it does not have a comprehensive plan for corrective action. According to federal internal control standards, agency management should (1) evaluate and document internal control deficiencies and (2) determine appropriate corrective actions for internal control deficiencies on a timely basis. In addition, third parties can help management identify issues in the agency’s internal control system, though management has the responsibility to evaluate any issues identified to determine whether they rise to the level of an internal control deficiency.[78] Over the past 5 years, the Commission has received findings from at least seven third-party assessments that have identified potential deficiencies in the agency’s internal control system, and Commission management has responded to them in different ways (see table 3).

Table 3: Third-Party Assessments of the Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission (Commission)

|

Third party |

Assessment topic (date) |

Selected third-party findings |

Actions taken in response to assessment |

|

|

Professional services firm |

Procurement assessment (2021) |

The Commission did not follow Federal Acquisition Regulation requirements when it conducted certain procurements; agency staff lacked appropriate training. |

The Commission outsourced procurement function to a shared service provider.a |

|

|

Human capital shared service provider |

Office of the Executive Director structure and position assessment (2022) |

The office structure and positions did not fully support strategic plan; positions were misclassified; structure had gaps in workforce planning and position management. |

Commission management has reviewed some position descriptions, though the agency has maintained an unofficial hiring freeze since 2022. |

|

|

Department of the Interior Office of Inspector Generalb |

Investigation of alleged misconduct by an employee (2023) |

The employee did not violate any Commission rules on a matter related to a large transfer of electronic agency records to a personal device, as the Commission had no relevant policies. |

The Commission created an employee code of conduct for using the agency’s information technology equipment. |

|

|

Department of the Interior Office of Inspector Generalb |

Investigation of alleged misconduct by an official (2023) |

Official #1 violated an ethics pledge related to a Commission hiring matter. |

The Commission provided some officials with additional ethics training. |

|

|

Department of the Interior Office of Inspector Generalb |

Investigation of alleged misconduct by an official (2023) |

Official #2 potentially implicated a federal criminal law related to extortion. U.S. Attorney’s Office declined prosecution. |

None; the official is no longer employed by the Commission. |

|

|

Financial auditor |

Annual financial statement audit (2024) |

The Commission lacked documented policies or procedures for significant processes; agency budgetary approval process had deficiencies. |

The Commission has drafted a plan to address the findings and officials said that the Commission needs to obtain additional resources to fully implement its plan. |

|

|

Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and Office of Special Counsel (OSC)c |

Review of career appointment of former political appointee (2022–2024) |

OPM determined in 2022 that the Commission did not seek approval prior to an appointment and could not conclude that the action conformed with merit system principles. OPM referred the allegation to OSC. According to Commission officials, OSC found that multiple Commission hiring actions may not have complied with federal law. OSC briefed the Commission on the findings from its investigation in 2024 and recommended disciplinary action for the hiring official. |

The former political appointee is no longer employed by the Commission. The hiring official retired in 2025 after receiving a decision for removal from the Commission. |

|

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Mine Safety and Health Review Commission interviews and related documentation. | GAO‑25‑107171

aThe Commission makes use of a shared service provider to outsource some administrative support for the agency’s operations, including for financial management, procurement, and human resources services.

bInspectors General are independent units within certain agencies that may conduct audits, investigations, and inspections, among other things. The Department of the Interior Office of Inspector General provided the Commission with investigative services through an interagency agreement.

cOPM is the federal government’s central personnel management agency that administers and enforces federal civil service laws, regulations, and rules. OSC is an independent agency that investigates and prosecutes allegations of certain civil service law violations.

The Commission has made progress on some of the issues that the third parties identified, but it has not addressed others. For example, the Commission hired a shared service provider to help with its procurement activities and provided additional ethics training for some officials. In other cases, Commission management has yet to address findings that the third parties identified. For example, the Commission’s 2024 financial audit found internal control deficiencies and recommended that it document policies and procedures for all significant process areas and ensure that budgetary approval is documented for each contract before obligating funds. The audit found that Commission staff were unable to provide evidence of budgetary approval for more than 10 percent of procurement and budget samples that the audit tested. As of July 2025, the Commission had created a plan to address these issues identified in the audit. However, a senior Commission official said they could not implement the plan until the Commission hired people with the necessary skills.

Officials said that the Commission did not have a process in place for identifying internal control deficiencies and had not fully adhered to relevant OMB Circular No. A-123 guidance concerning corrective action plans for addressing internal control deficiencies.[79] Officials also said that the Commission lacked a structured framework for tracking and addressing deficiencies and had an absence of personnel with the necessary expertise. Without establishing a process to address internal control deficiencies on a timely basis, including those identified by third parties, the Commission risks the integrity of its operations and may miss opportunities to improve its performance.

Commission Leadership’s Limited Attention to Employee Feedback and Overseeing Operations Threatens Its Performance and Accountability

Limited Leadership Attention to Employee Feedback

Commission leadership has given limited attention to soliciting employee feedback to inform new initiatives or address potential workplace culture challenges. The Commission has not sought formalized employee feedback since 2022, although federal law requires agencies annually to solicit employee feedback about the agency’s work environment.[80] Several employees told us that when the Commission had solicited feedback, management did not develop strategies to address any shortcomings identified. We selected 14 employees across the Commission to discuss their perspectives on working at the Commission. Nine employees told us that management did not solicit employee feedback. Three employees specifically said they perceived a disconnect between management and staff.

In late 2020, the Commission formed a work environment committee, which identified the Commission’s core values of fair treatment, respect, service, and trust. The committee drafted recommendations that sought to address training, agency communication and engagement, inclusivity, and leadership. A committee member told us that the recommendations were not formally submitted to the Chair at the time due to other management challenges. The committee is no longer active.

Employee feedback helps management evaluate an agency’s adherence to ethical values and standards of conduct, according to federal internal control standards.[81] Those standards also state that an agency’s management should receive quality information about operations from personnel. Without this feedback, Commission management may miss opportunities to improve its operations and achieve Commission objectives.

Limited Leadership Attention to Commission Operations

Commission leadership has given limited attention to managing its operations. The Commission Chair—who has held the position for about 15 of the past 30 years—told us that she focused more on the Commission’s appellate work than on management duties.[82] She also said that she was generally not familiar with specific Commission goals or other information in the current strategic plan and 2024 Performance and Accountability Report.

Three senior Commission officials told us that disengaged leadership threatened the Commission’s ability to accomplish its goals. The officials emphasized that, without action by the Chair, the Commission could not take steps such as hiring staff and creating policies. In addition, the officials described a broader lack of attention to the Commission’s strategic plan and to management of the Commission’s performance. For example, one department head said that they were generally unfamiliar with the goals listed in the strategic plan and were specifically unfamiliar with their department’s goals. Other senior leaders said they did not use the Commission’s goals, and two suggested the Commission’s completed casework showed the agency is accomplishing its mission.

Two former Commission chairs told us that leadership should have been more involved with administering Commission operations. One told us that Commission leadership generally had not been as aware of the Commission’s human capital needs and other operational challenges as they should have been. Another former chair told us that administering the Commission is a central function of the chair’s role, but that leadership relied too heavily on a key Commission official who did not have the skills or training to carry out their duties successfully. Though three officials said that the Commission had started to identify ways to make improvements—such as the COO assembling a list of agency policies that staff need to create or update—the officials also said that current leadership was not sufficiently engaged.[83]

Leadership disengagement can undermine agency performance management. Our past reporting noted that the demonstrated commitment of senior leadership is perhaps the single most important element of successfully managing and improving the performance of federal organizations.[84] According to federal internal control standards, management sets the agency’s strategic plan and uses internal controls to achieve its objectives.[85] We found that the Commission had not established an internal control system to ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of its operations. Sustained leadership commitment to oversight and accountability is the key to driving the sort of transformational change needed at the Commission. Without leadership demonstrating a commitment to continuous improvement, the agency may not be able to meet its goals. Commission leadership has the opportunity to demonstrate this commitment by addressing the shortfalls we have identified to strengthen the Commission’s internal control system and, ultimately, the oversight of the Commission’s operations.

The Commission Has Sought Independent Oversight from a Variety of Sources for Targeted Issues but Lacks Comprehensive Oversight

The Commission Had Challenges Obtaining Independent Oversight but Received Help on a Limited Set of Issues

Since 2021, the Commission sought investigative support for certain personnel matters after it became aware of allegations of improper procurement activities against one official and additional allegations of misconduct against other officials.[86] To investigate these matters, the Commission sought assistance from third parties, particularly an external IG.[87] The Commission received support for some of its personnel matters, though it was unable to resolve the allegations of improper procurement activities.

In November 2021, the Commission received allegations that a senior officer in the Office of the Executive Director engaged in improper procurement activities, and, in March 2022, the Commission placed the officer on administrative leave.[88] Following advice from the Commission’s human capital shared service provider, a senior Commission official told us that they contacted two federal agency IG offices to request support for investigating the employee’s alleged improper procurement activities.[89] The official told us that the first IG office said it could not take on additional work due to limited resources, and the Commission was unable to secure an agreement with the second IG office. A Commission official told us that their contact at the second IG office recommended that they reach out to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).[90]

A senior Commission official told us that they reached out to the FBI in February 2022 and were interviewed by FBI officials. According to Commission officials, the FBI opened an inquiry into the allegations related to the senior officer’s procurement activities. Officials said they were advised that the FBI’s involvement should not deter the Commission from pursuing other avenues for investigating the allegations, such as securing the help of an IG.[91] As of January 2024, Commission officials told us that their last contact with the FBI was in July 2023.[92]

In March 2022, a White House official directed the Commission to contact CIGIE for assistance securing IG investigative services.[93] According to officials, the Commission sought IG support for a variety of issues related to misconduct by three officials, in addition to the Office of the Executive Director senior officer’s alleged improper procurement activities.[94] CIGIE officials informed the Commission that it would work to find IG support for it, though it advised the Commission to avoid seeking support for any matter that might interfere with the FBI’s inquiry related to the senior officer on administrative leave.[95] In July 2022, CIGIE notified the Commission that the Department of the Interior IG had agreed to assist it.

In October 2022, the Commission entered into an interagency agreement with the Department of the Interior IG office for investigating a specific ethics matter. Commission officials said they hoped the investigation would also resolve the improper procurement allegations concerning the senior officer. In June and July of 2023, the Department of the Interior IG office delivered three investigative reports to the Commission on alleged misconduct of the three other officials.[96] Commission officials told us that they also sought investigative support for the allegations of improper procurement activities concerning the senior officer. However, in July 2023, the Department of the Interior IG office said it would not be able to conduct additional work beyond the ethics matter identified above. In September 2023, the Commission sent a letter to CIGIE requesting investigative support for the improper procurement allegations. In response, CIGIE informed the Commission in November 2023 that no other IG had expressed interest in providing investigative support.[97]

The Commission ultimately removed the senior officer from their position due to an unrelated administrative matter. As noted earlier, OPM reviewed a 2020 Commission hiring action and informed the Commission that it could not conclude the action conformed with merit system principles. OPM referred the matter to OSC for review and appropriate action. Commission officials told us that OSC briefed the Commission on the findings from its investigation in November 2024 and recommended disciplinary action for the senior officer, who was the hiring official.[98] The Commission subsequently sent a notice of proposed removal to the senior officer, who retired after receiving a decision for removal. By this point, the senior officer had been on administrative leave for over 3 years.

Several Options Exist to Meet the Commission’s Oversight Needs, Including Using an Existing Inspector General

Senior Commission officials said that the Commission could benefit from additional independent oversight. One commissioner said that the myriad investigations over the last few years showed the need for dedicated independent oversight. Several officials told us that the barriers to securing investigative services remained and could lead to future challenges. Officials noted that if the Commission were to receive an allegation of impropriety, it would not have the ability to investigate it. Nonetheless, some officials expressed concern that creating an IG office whose sole jurisdiction was the Commission would be an inefficient use of resources.

We reviewed examples of smaller agencies that obtained oversight assistance from external IGs, which generally occurred in three ways and are discussed below. Stakeholders we spoke with, including officials from CIGIE, an IG office, and a consortium of small agencies, provided examples of smaller agencies that obtained assistance from IG offices to provide independent oversight. Stakeholders noted that the options typically require additional resources and, in some cases, legislative action by Congress. Further, some arrangements may be more effective for an agency depending on the support the agency seeks. Below are three options.

Obtain Specific, Limited Services from an External IG