INTERNET OF THINGS

Federal Actions Needed to Address Legislative Requirements

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107179. For more information, contact David B. Hinchman at (214) 777-5719 or hinchmand@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107179, a report to congressional committees

Federal Actions Needed to Address Legislative Requirements

Why GAO Did This Study

Cyber threats to IoT—such as a recent cyberattack on a municipal water system—represent a significant national security challenge. The IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 includes provisions for (1) NIST and OMB to establish guidance for securely procuring IoT, and (2) 23 civilian federal agencies to implement IoT cybersecurity requirements. The act also requires OMB to establish a waiver process for those requirements.

The act includes provisions for GAO to report every 2 years on IoT guidance and the waiver process through 2026. This report, the second of three, (1) describes guidance for securely procuring IoT, and (2) evaluates agencies’ progress in addressing IoT cybersecurity and waiver requirements.

GAO identified federal agencies with cybersecurity or acquisition responsibilities. GAO then described relevant guidance developed by those agencies covering IoT. It also compared agencies’ implementation efforts to the act and OMB’s requirements for IoT inventories and waiver processes. GAO also interviewed relevant agency officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making one recommendation to OMB and 10 to nine civilian agencies covered by the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 to address legislative requirements related to IoT. Eight agencies concurred with our recommendations. The remaining agencies neither agreed nor disagreed with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

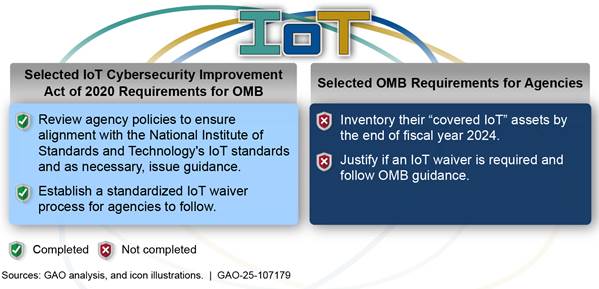

The Internet of Things (IoT) generally refers to the technology and devices that allow for the connection and interaction of “things” throughout such places as buildings, vehicles, and the transportation infrastructure. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Department of Homeland Security's Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency have issued guidance for securely procuring IoT. For example, NIST has issued cybersecurity guidance for agencies to use in mitigating risk with the acquisition, procurement, and use of IoT at all stages of a system’s life cycle. In 2022 and 2023, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) also issued guidance for ensuring that 23 civilian agencies covered by the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 address NIST’s guidelines, establish IoT inventories, and process IoT cybersecurity waivers.

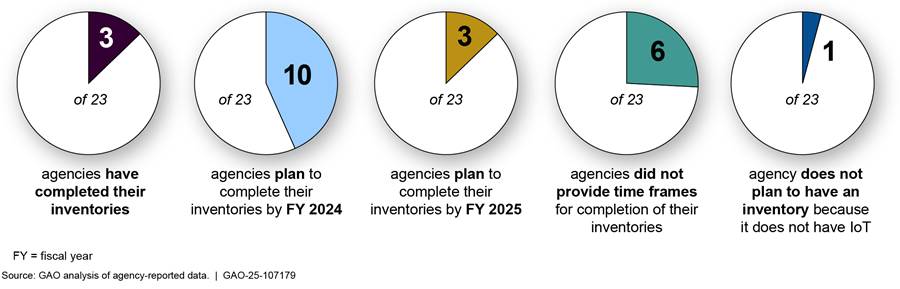

Many of the 23 civilian agencies have not yet fully addressed OMB’s IoT requirements on inventories and waivers. Of these 23 agencies:

· Three stated that they would not complete their inventories by the OMB-established deadline of September 30, 2024, and stated that they plan to do so in fiscal year 2025; six did not provide time frames; and one stated that it does not intend to establish an inventory because it does not have any IoT.

· Six agencies reported granting IoT cybersecurity waivers of certain requirements. However, in following up with these six, officials from five of the agencies stated that they should not have reported waivers. Four of the five subsequently corrected their reported efforts. Additionally, one agency corrected its waiver by removing it, and one (the Department of Health and Human Services) has not yet corrected its waiver. In addition, OMB did not verify any of the reported waiver data and reported erroneous information.

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Agency Implementation of Selected Internet of Things (IoT) Requirements

Until OMB and agencies ensure that agencies are meeting OMB’s requirements, the agencies will not be effectively positioned to assess risks so that they can impose appropriate security requirements and take other mitigating actions.

Abbreviations

|

CFO Act |

Chief Financial Officers Act |

|

CIO |

Chief Information Officer |

|

CISA |

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

FAR Council |

Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council |

|

FASC |

Federal Acquisition Security Council |

|

FISMA |

Federal Information Security Modernization Act |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

ICT |

information and communications technology |

|

IoT |

Internet of Things |

|

IT |

information technology |

|

NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

|

NDAA |

National Defense Authorization Act |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

NRC |

Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OT |

operational technology |

|

SCRM |

supply chain risk management |

|

SP |

special publication |

|

SRMA |

sector risk management agency |

|

USDA |

United States Department of Agriculture |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 4, 2024

Congressional Committees

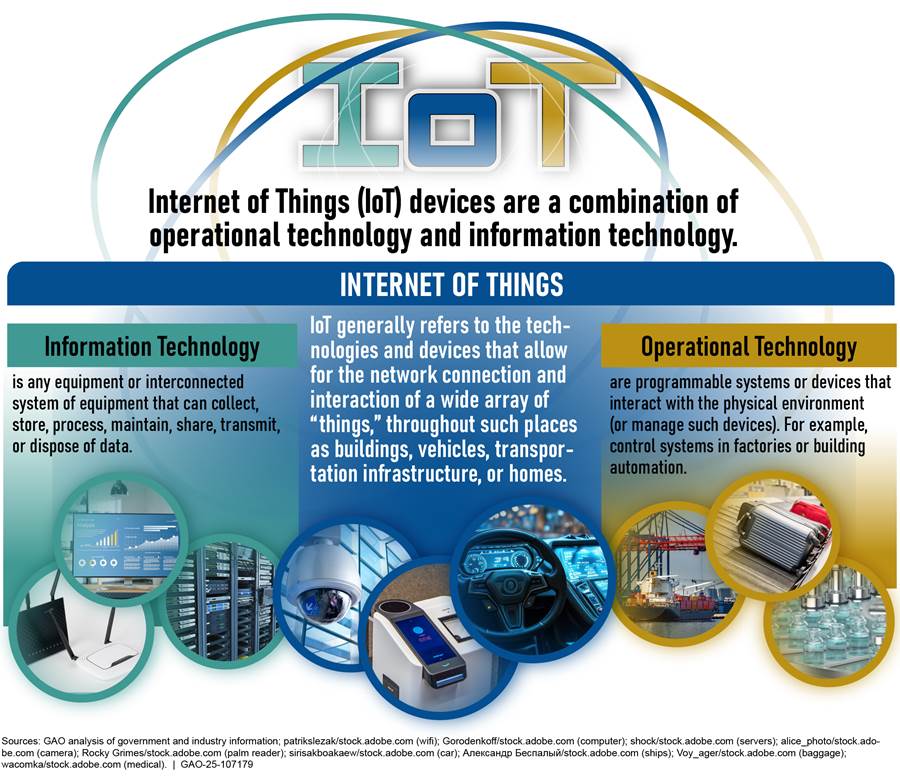

The critical infrastructure of the nation, including electricity, health care, and transportation, underpins American society.[1] The nation’s infrastructure relies on information systems, including the Internet of Things (IoT), to support its varied missions. IoT generally refers to the technologies and devices that allow for the network connection and interaction of a wide array of devices that interact with the physical world, or “things”, throughout such places as buildings, vehicles, transportation infrastructure, or homes.

The risks facing technologies such as IoT include escalating and emerging threats from around the globe, the emergence of new and more destructive attacks, and insider threats from witting or unwitting employees. Recent incidents—such as a cybersecurity attack on a Pennsylvania municipal water system in which a cyber threat actor gained access to internet-connected devices used to monitor and regulate water pressure—highlight the risks posed by these systems.[2]

Due to the cyber-based threats to federal systems and critical infrastructure, the persistent nature of information security vulnerabilities, and the associated risks, we first designated federal information security as a government-wide high-risk area in our biennial report to Congress in 1997. In 2003, we expanded this high-risk area to include the protection of critical cyber infrastructure, and in 2015 we further expanded this area to include protecting the privacy of personally identifiable information. We continue to identify the protection of critical cyber infrastructure as a high-risk area, as shown in our June 2024 high-risk update on major cybersecurity challenges.[3]

The Internet of Things (IoT) Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 includes requirements for the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to establish guidance for securely procuring IoT.[4] It also includes requirements for the civilian agencies subject to the Chief Financial Officers Act (CFO Act) of 1990 regarding IoT cybersecurity.[5] The IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act also includes provisions for us to report on efforts to enhance the cybersecurity of IoT. Specifically, it includes provisions for us to report on IoT procurement guidance and the effectiveness of OMB’s waiver process for selected IoT cybersecurity requirements.[6] Our specific objectives for this review were to (1) describe guidance for securely procuring IoT, and (2) evaluate agencies’ progress in addressing IoT cybersecurity and waiver requirements.

To address our first objective, we identified federal agencies with cybersecurity or acquisition responsibilities. These agencies included OMB, NIST, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Federal Acquisition Regulatory (FAR) Council. We then identified relevant guidance, directives, and regulations developed by these agencies for the acquisition of technologies, including IoT. We selected those that covered the procurement of securable IoT. We validated them with the agencies and made changes as appropriate.

To address our second objective, we compared selected requirements of the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 against OMB’s efforts to implement them. Specifically, we evaluated OMB’s efforts to review agency policies to ensure their alignment with NIST’s IoT standards. We also assessed the extent to which OMB issued additional guidance to agencies, as necessary, to ensure they followed NIST’s guidance.

We also compared the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies’ implementation efforts to OMB’s requirements related to the act. These efforts included efforts to develop inventories of covered IoT and granting waivers for IoT devices that do not comply with NIST standards. We assessed documentation such as agencies’ Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) reports and agency waivers for IoT devices. We also summarized information on the number of waivers the agencies have reported and granted under OMB’s implementation guidance. For both objectives, we interviewed relevant agency officials to obtain their views and verify the information provided. For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

According to NIST, IoT technology generally acts as a connection or bridge between IT and operational technology (OT) technologies. IT includes technologies used in data processing, networking, sharing, and disposing of data. OT includes controllers, sensors, and actuators. NIST defines OT as programmable systems or devices that interact with the physical environment (or manage devices that interact with the physical environment).[7] These systems and devices detect or cause a direct change through the monitoring or control of devices, processes, and events. According to NIST, examples of OT include supervisory control and data acquisition systems, distributed control systems, and building automation systems. In December 2023, OMB introduced the concept of “covered IoT,” an administrative definition of IoT that includes some technologies that are traditionally called OT.[8]

Many IoT devices are the result of the convergence of cloud computing, mobile computing, embedded systems, big data, low-price hardware, and other technological advances. IoT devices can provide computing functionality, data storage, and network connectivity for equipment that previously lacked them. This has enabled new efficiencies and technological capabilities for equipment, such as remote access for monitoring, configuration, and troubleshooting. IoT can also add the abilities to analyze data about the physical world and use the results to better inform decision-making, alter the physical environment, and anticipate future events. Agencies use a wide variety of IoT technologies, ranging from specialized connected hospital equipment in hospital settings to smart building management or smart road technologies.

NIST reported that IoT is a rapidly evolving and expanding collection of diverse digital technologies that interact with the physical world. One private sector estimate is that the global value of IoT could range from $5.5 to $12.6 trillion by 2030.[9]

See figure 1 for an overview of the intersection between IT, IoT, and OT.

Cyber Threats to IoT and Related Technologies

IT, IoT, and OT devices and systems that support federal agencies and our nation’s critical infrastructures are increasingly at risk. These systems are highly complex, technologically diverse, and often geographically dispersed. In addition, they are often interconnected with other internal and external systems and networks, including the internet. This complexity increases the difficulty of identifying, managing, and protecting the numerous operating systems, applications, and devices comprising the federal government’s systems and networks.

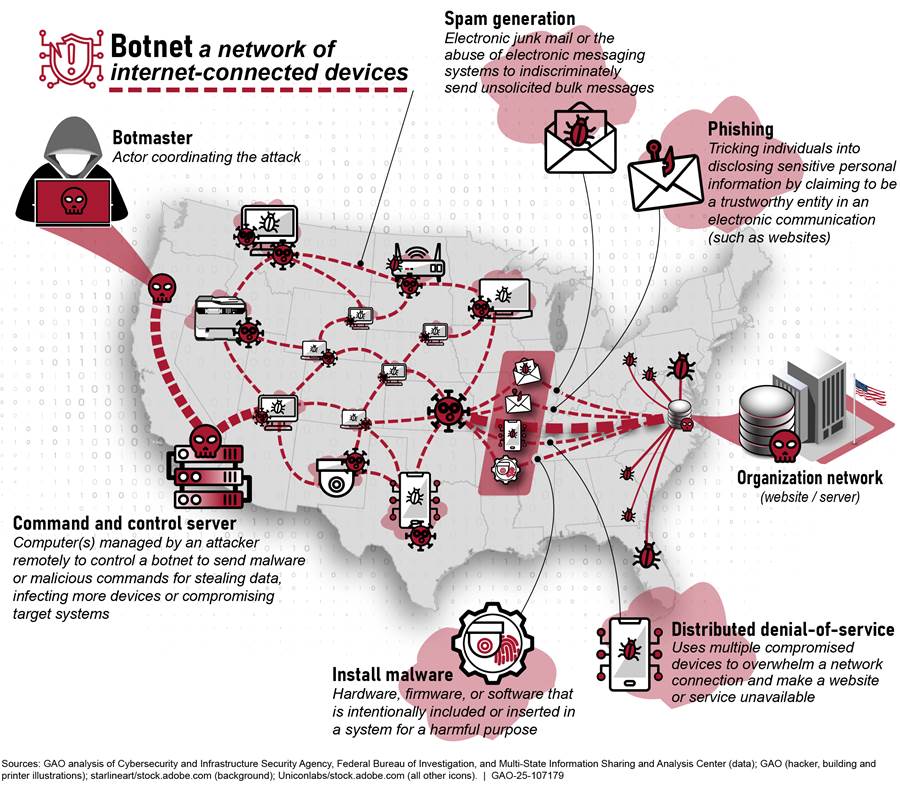

These technologies are subject to serious cyber threats that can have adverse impacts on organizational operations and assets, individuals, critical infrastructure, and the nation. As cyber threats grow increasingly sophisticated, the need to manage and bolster the cybersecurity of IoT and OT products and services is also magnified. These cyber threats can include purposeful attacks, environmental disruptions, and machine errors, and may result in harm to the national and economic security interests of the United States. Table 1 describes key types of purposeful cyberattacks that could affect IoT devices and networks, and figure 2 depicts a theoretical botnet attack involving IoT.

|

Types of attack |

Description |

|

Botnet |

A network of internet-connected computing devices infected with bot malware and that are remotely controlled by third parties for nefarious purposes. A botnet attack happens when a network of computers, Internet of Things, or other internet protocol-enabled devices are commandeered to run unauthorized code in support of malicious activities such as spam, phishing, and distributed denial of service. |

|

Denial-of-service |

An attack that prevents or impairs the authorized use of networks, systems, or applications by exhausting resources. A distributed denial-of-service attack is a variant of the denial-of-service attack that uses numerous hosts to perform the attack. |

|

Malware |

Also known as malicious code and malicious software, malware refers to a program that is inserted into a system, usually covertly, with the intent of compromising the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of the victim’s data, applications, or operating system or otherwise annoying or disrupting the victim. |

|

Man-in-the-middle |

An attack where the attacker comes in between a two-party communication, i.e., the attacker hijacks the session between a client and host. By doing so, hackers steal and manipulate data. |

|

Zero-day exploit |

An exploit that takes advantage of a security vulnerability previously unknown to the general public. In many cases, the exploit code is written by the same person who discovered the vulnerability. By writing an exploit for the previously unknown vulnerability, the attacker creates a potent threat since the compressed time frame between public discoveries of both makes it difficult to defend against. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Homeland Security, National Institute of Standards and Technology information, and industry reports. │ GAO‑25‑107179

Figure 2: Theoretical Botnet Attack Involving Network-Connected Devices Including the Internet of Things (IoT)

Recent events highlight significant cyber threats facing the nation and the range of consequences that these attacks pose.

· In June 2022, the Department of Justice reported that a Russian botnet targeted a broad range of IoT and OT devices. These devices included time clocks, routers, audio/video streaming devices, smart garage door openers, and industrial control systems, which are connected to and can communicate over the internet.[10] Millions of devices were compromised, and victims varied from large entities—including a university, hotel, television studio, and electronic manufacturers—to small entities such as home businesses and individuals.[11]

· In early 2024, DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), the National Security Agency, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation reported their assessment that a People’s Republic of China’s state-sponsored cyber group had compromised IT networks at critical infrastructure organizations. The targeted sectors included the Communications, Energy, Transportation Systems, and Water and Wastewater Systems sectors. Specifically, the agencies noted that the threat actors appeared to be pre-positioning themselves on IT networks to enable them to move to network-connected OT assets to disrupt functions of critical infrastructure in the future.[12]

IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020

The act includes provisions for the protection of IoT owned or controlled by federal agencies.[13] The act requires NIST to develop and publish standards and guidelines for the federal government on agencies’ use and management of IoT devices. Specifically, these include devices owned or controlled by an agency and connected to networks owned or controlled by the agency. NIST’s standards and guidelines are to include establishing minimum information security requirements for managing cybersecurity risks associated with such devices.

In addition, the act requires OMB to establish a standardized process for agency Chief Information Officers (CIO) to use for obtaining waivers to the IoT cybersecurity requirements outlined below. OMB is also to review agency policies pertaining to IoT devices owned or controlled by agencies for consistency with NIST standards and guidelines. OMB is then to issue policies and principles, as necessary, to ensure agency policies are consistent with the NIST guidelines concerning IoT.

Generally, before any civilian CFO Act agencies may enter or renew a contract for IT or IT services, the agency CIO must review and approve the contract, as required by law. Under the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020, if during that review for a system including IoT, the CIO determines that using the device would prevent the agency from complying with NIST IoT standards and guidelines, the agency is prohibited from using the device. The agency would also be prohibited from procuring or obtaining the device or renewing a contract to procure or obtain the device.

This prohibition may be waived by the head of the agency, but only if the agency CIO first determines that at least one of the following conditions is met:

1. The waiver is necessary in the interest of national security.

2. Procuring, obtaining, or using the IoT device is necessary for research purposes.

3. The device is secured using alternative and effective methods appropriate to its function.

Federal Roles and Responsibilities for Procuring and Securing IoT

Several entities within the federal government have responsibilities for helping oversee and guide the procurement of secure IoT technologies.

OMB. The agency oversees the management of federal agencies’ technologies, and, in conjunction with other agencies, implements the President’s Management Agenda. According to OMB, its role and the role of the Office of the Federal Chief Information Officer within OMB are to enable agencies to adopt IT technology, including IoT, in a manner that is consistent with the President’s budget and that enhances the agency’s mission.[14] In addition, OMB includes the Office of Federal Procurement Policy. The office plays a central role in shaping the policies and practices federal agencies use to acquire the goods and services they need to carry out their responsibilities, which include IoT.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS). The agency oversees technology-specific issues in support of the 2013 National Infrastructure Protection Plan (referred to as the National Plan).[15] In this role, DHS coordinates with other federal agencies, works with private sector entities that support critical infrastructure, and contributes to the development of guidance related to security considerations when acquiring IoT devices. In addition, the Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 authorized DHS to issue binding operational directives to federal agencies, consistent with OMB’s policies and guidance.[16] These directives require agencies to safeguard federal information and information systems, including IoT devices, from a known or reasonably suspected information security threat, vulnerability, or risk.

CISA. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency Act of 2018 established CISA within DHS.[17] CISA is responsible for developing and implementing information sharing programs. Through these programs, CISA develops partnerships with and shares substantive information with the private sector, and state, local, tribal, and territorial governments. This includes information on IoT threats. In addition to information sharing initiatives, CISA is also responsible for developing resources to help spread awareness about cyber threats, protective measures, and response tactics.

NIST. The agency conducts research and develops standards, guidelines, and tools for public and non-public organizations. NIST develops security standards and guidelines for non-national-security federal agency systems, which can be mandatory for federal agencies. NIST has issued multiple publications and engaged in projects to help manage the security of IoT such as Special Publication (SP) 800-213- IoT Device Cybersecurity Guidance for the Federal Government: Establishing IoT Device Cybersecurity Requirements. This guidance is intended to help federal agencies securely incorporate IoT devices into an existing information system as system elements.[18]

Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council. The Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) is the primary regulation used by all federal executive agencies to acquire supplies and services with appropriated funds. The Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council, which consists of the Secretary of Defense and the Administrators of the Office of Federal Procurement Policy in OMB, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and the General Services Administration, assists in the direction and coordination of government-wide procurement policy and regulatory activities. The council is responsible for maintaining the FAR and managing, coordinating, and controlling changes in the FAR. Several revisions to the FAR, as discussed later, are being considered based on recent NIST guidance on IoT cybersecurity, among other things.

Federal Acquisition Security Council. The Federal Acquisition Security Council (FASC) was established by the Federal Acquisition Supply Chain Security Act of 2018. The FASC is a cross-agency council responsible for providing guidance to executive agencies to reduce their information and communications technology (ICT) supply chain risks, including for IoT.[19] According to officials in OMB’s Office of the Chief Information Officer, the council finalized a strategic plan in June 2020 for addressing supply chain risks. The plan is intended to, among other things, establish requirements for sharing relevant information about supply chain risks with all federal agencies. The FASC can also recommend removal orders on specific technologies, including IoT and OT, that may pose supply chain risks.

Prior GAO Reports on the Status of IoT and Cybersecurity Risks

In March 2024, we reported on challenges associated with supporting the security of private sector OT by the federal government, including getting entities accurate and timely cybersecurity support from CISA.[20] We recommended that CISA measure customer service for its OT products and services, perform effective workforce planning for OT staff, and develop a policy on agreements with sector risk management agencies (SRMA) with respect to collaboration.[21] We also recommended that CISA issue guidance to the SRMAs on how to update their plans for coordinating on critical infrastructure issues. As of July 2024, the recommendations have not yet been implemented.

In December 2022, we reported on cybersecurity risks associated with IoT and OT, including in selected key critical infrastructure areas.[22] We found that while guidance and resources have been developed to help manage cybersecurity risks to IoT and OT devices, selected SRMAs lacked IoT and OT specific metrics to measure the effectiveness of their efforts. We also found that none of the selected SRMAs had conducted sector-wide risk assessments specific to IoT and OT devices. In addition, we noted that OMB had not yet established a standardized IoT device cybersecurity waiver process for the CIOs of covered federal agencies, as required by law. Accordingly, we made four recommendations to the selected SRMAs regarding the establishment and use of metrics to assess cybersecurity efforts. We made four additional recommendations regarding evaluating sector IoT and OT efforts. These eight recommendations have yet to be implemented. We also made one recommendation to OMB regarding issuing an IoT cybersecurity waiver process, as required by the act. In December 2022, OMB implemented the recommendation with the issuance of guidance in the form of a memorandum.[23]

Additionally, in August 2020, we reported that many federal agencies used IoT technologies for a variety of purposes, such as to control or monitor equipment or systems and to control access to devices or facilities.[24] We also noted that agencies often identified increased data collection and operational efficiencies as benefits and cybersecurity and interoperability as challenges.

Federal Agencies Have Issued Guidance Relevant to Securely Procuring IoT Devices

Federal agencies, including NIST, OMB, and DHS have issued guidance, directives, and regulations to help federal agencies securely procure IoT devices for their agencies, among other things. These are noted below.

NIST. The agency’s Risk Management Framework is a risk-based approach that integrates security, privacy, and cyber supply chain risk management activities into the system development life cycle for federal agencies.[25] The framework also has many supporting documents, as well as detailed vulnerability disclosure guidance on specific IoT devices.

The agency has also issued a variety of guidance documents for agencies to use in mitigating risk with the acquisition, procurement, and use of IoT and OT at all stages of a system’s life cycle.[26] These documents include publications on the risk management of security, supply chain guidance, and consumer IoT.

NIST’s guidelines in the special publication Establishing IoT Device Cybersecurity Requirements highlight a variety of approaches to securing IoT devices.[27] For example, if an IoT device lacks certain capabilities to support the information system’s security controls, the capabilities lacking in the IoT device might be provided by other systems or system elements such as an IoT hub, cloud service, or mobile application. Alternatively, the organization might choose to implement compensating controls such as creating a segmented network for IoT. It could also reimplement existing controls such as changing a policy or procedure for a control in response to IoT device limitation. The guidance further notes that if risks introduced by the IoT device cannot be mitigated within the organization’s risk tolerance level, the organization could accept these new risks or decide to not incorporate the IoT device into the information system.

In addition, NIST has also published a number of other documents that address IoT. Table 2 describes the key NIST publications that provide guidelines for the secure procurement of IoT and related devices.

Table 2: Key National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Publications Providing Guidelines Relevant to the Secure Procurement of Internet of Things (IoT) and Related Devices

|

Publication (release date) |

Description |

|

Special Publication (SP) 800-82 Revision 3, Guide to Operational Technology (OT) Security (September 2023) |

Intended to describe how to apply the NIST Risk Management Framework (SP 800-37, Revision 2) to OT and provide an overlay of the NIST SP 800-53, Revision 5 control catalog to further help organizations apply the NIST controls to OT. |

|

SP 800-161r1, Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management Practices for Systems and Organizations (May 2022) |

Intended to provide organizations with a systematic process for managing exposure to cybersecurity risks throughout the supply chain and developing appropriate response strategies, policies, processes, and procedures for supply chain risk management (SCRM).a It is to provide guidance to enterprises on how to identify, assess, select, and implement risk management processes and mitigating controls across the enterprise to help manage cybersecurity risks throughout the supply chain. The content in this guidance is the shared responsibility of different disciplines with different SCRM perspectives, authorities, and legal considerations. |

|

SP 800-213, IoT Device Cybersecurity Guidance for the Federal Government: Establishing IoT Device Cybersecurity Requirements (November 2021) |

Intended to help federal agencies consider how an IoT device they plan to acquire can integrate into a system. It provides information on considering system security from the device perspective, which allows for the identification of device cybersecurity requirements—the abilities and actions an organization will expect from an IoT device and its manufacturer or third parties, respectively. |

|

SP 800-213A, IoT Device Cybersecurity Guidance for the Federal Government: IoT Device Cybersecurity Requirement Catalog (November 2021) |

Intended to provide agencies a catalog of IoT device cybersecurity capabilities and non-technical supporting capabilities that can help organizations as they use SP 800-213 to determine and establish device cybersecurity requirements. |

|

SP 800-53, Revision 5, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations (September 2020) |

Intended to help federal agencies to protect organizational operations and assets, individuals, other organizations, and the nation from a diverse set of threats and risks. The controls are flexible, customizable, and implemented as part of an organization-wide process to manage risk. It provides a catalog of security and privacy controls for federal information systems and a process for selecting controls to protect organizational operations and assets, which includes the IoT and OT. |

|

NIST Interagency Report 8228, Considerations for Managing Internet of Things (IoT) Cybersecurity and Privacy Risks (June 2019) |

Intended to help federal agencies and other organizations better understand and manage the cybersecurity and privacy risks associated with their individual IoT devices throughout the devices’ life cycles. It identifies considerations that may affect the management of cybersecurity and privacy risks for IoT devices as compared to conventional IT devices and describes ways that organizations can mitigate IoT cybersecurity and privacy risks. |

|

SP 800-37, Revision 2, Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy (September 2018) |

Intended to help organizations understand NIST’s Risk Management Framework and provide guidelines for applying the framework to information systems and organizations. It provides a disciplined, structured, and flexible process for managing security and privacy risk that includes information security categorization; control selection, implementation, and assessment; system and common control authorizations; and continuous monitoring. |

Source: GAO Analysis of NIST Publications. │ GAO‑25‑107179

aNIST defines the supply chain as a linked set of resources and processes between and among multiple levels of organizations, each of which is an acquirer, that begins with the sourcing of products and services and extends through their life cycle.

In addition, we have previously reported on the foundational practices identified by NIST associated with supply chain risk management (SCRM) and the acquisition of IT and ICT. These practices also cover both IoT and OT.[28] The practices are: (1) establish executive oversight of ICT SCRM activities, (2) develop an agency-wide ICT SCRM strategy, (3) establish an approach to identify and document agency ICT supply chain(s), (4) establish a process to conduct agency-wide assessments of ICT supply chain risks, (5) establish a process to conduct a SCRM review of a potential supplier, (6) develop organizational ICT SCRM requirements for suppliers, and (7) develop organizational procedures to detect counterfeit and compromised ICT products prior to their deployment.

At the time, we issued 145 recommendations intended to help agencies address shortcomings in their SCRM practices. As of September 2024, approximately 40 percent of the recommendations have yet to be implemented.

OMB. As noted earlier, in December 2022, in response to the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 and our December 2022 recommendation, OMB issued guidance in the form of a memorandum for agencies to follow in requesting waivers.[29] In December 2023, OMB issued updated guidance in a memorandum.[30] The December 2023 memorandum: (1) clarified the IoT cybersecurity waiver process; (2) introduced the concept of “covered IoT”; (3) required agencies to develop inventories of the IoT covered by OMB’s guidance, including the identification of the critical functions of the technologies; and (4) directed the establishment of a working group to develop IoT security best practice playbooks.

In addition, OMB is coordinating a cross-agency group comprised of representatives from over a dozen agencies to develop best practice playbooks for specialized IoT and OT security for key federal government uses. The playbooks may address building management systems, industrial control systems, health and medical devices and systems, scientific laboratories, and aerospace systems, among other categories of IoT. OMB officials noted that the efforts should leverage existing cybersecurity regimes and industry practices wherever feasible, so that IoT technology is appropriately integrated into the security frameworks and programs governing other forms of information technology. This effort is ongoing, and OMB did not share details on their planned outcome or time frames.

DHS and CISA. As part of its responsibility for furthering federal cybersecurity, FISMA authorizes DHS, in consultation with OMB, to develop and oversee the implementation of compulsory directives.[31] These are referred to as binding operational directives and cover non-national-security executive branch civilian agencies.[32] These directives require agencies to safeguard federal information and information systems from a known or reasonably suspected information security threat, vulnerability, or risk.

In January 2022, CISA issued a binding operational directive requiring agencies to address known exploited vulnerabilities in federal systems.[33] In implementing this effort, CISA is responsible for the federal Coordinated Vulnerability Disclosure Process and Program. The program allows agencies to identify vulnerabilities in devices. In addition, it coordinates the remediation and public disclosure of newly identified cybersecurity vulnerabilities in products and services with affected vendor(s). This includes new vulnerabilities in industrial control systems, IoT, and medical devices, as well as traditional IT vulnerabilities.

In addition, DHS, in cooperation with the General Services Administration and the IT Sector Coordinating Council (a partnership between the private IT sector and government sectors), published a guide on IoT security acquisition for the IT sector.[34] This guide is intended to highlight areas of elevated risk resulting from the software-enabled and connected aspects of IoT technologies and their role in the physical world and designed to be applicable to any critical infrastructure sector. It was designed to improve the effectiveness of supply chain, vendor, and technology evaluations prior to the purchase of IoT devices, systems, and services.

FAR Council. The FAR Council has worked to strengthen the procurement rules around IoT devices. Specifically, in October 2023, the FAR Council published a proposed rule in the Federal Register that would require contracts for the management of a federal information system to specify any cybersecurity requirements necessary for IoT devices in accordance with NIST SP 800-213. The proposed rule would also implement the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020’s prohibition on agencies’ acquisition of an IoT device determined to be non-compliant with NIST standards and guidelines, absent a waiver by the agency head. A variety of proposed rules and changes to the FAR may apply to IoT and OT. See appendix II for more information.

OMB and Agencies Are Taking Steps to Implement IoT Requirements, but Inventories and Waivers Are Not Fully Addressed

OMB conducted reviews of selected agencies’ IoT cybersecurity policies to determine whether they address NIST guidelines for IoT, as directed by the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020. It also subsequently issued additional guidance to agencies to ensure the agencies address NIST’s IoT guidelines. In addition, most of the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies are in the process of establishing inventories of covered IoT, which are to include, among other things, documentation of IoT cybersecurity controls that are in alignment with NIST guidelines, as directed by OMB. However, several agencies will not have an inventory completed by the end of fiscal year 2024 or have not provided time frames for completion. While OMB’s updated guidance to agencies implements the IoT cybersecurity waiver process required by the law, none of the six waivers reported to OMB were consistent with the IoT cybersecurity requirements. Additionally, in reporting on the waivers to Congress, OMB did not verify the agencies’ reported data.

OMB Reviewed Selected Agencies’ IoT Policies and Issued Additional Guidance

As previously stated, the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 directed OMB to review agency policies on obtaining IoT devices for consistency with NIST’s IoT guidelines.[35] The act also directed OMB to issue policies and principles, as necessary, to ensure agencies’ policies are consistent with the NIST’s IoT guidelines.

OMB officials stated that OMB reviewed selected agencies’ policies for consistency with NIST’s IoT guidelines in 2023. Specifically, officials noted that it reviewed six of the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies that were most likely to have IoT devices. These officials noted that relatively few of these agencies had policies that addressed the selection of cybersecurity requirements specifically for IoT devices.

Subsequently, in December 2023, OMB issued additional guidance for agencies to, among other things, ensure that the agencies’ IoT security controls are aligned with NIST’s IoT guidelines. Specifically, the December 2023 memorandum requires agencies to perform an IoT inventory and describe, among other things, how the security controls for each covered IoT asset align with NIST’s guidelines and other relevant standards.[36]

OMB officials stated that they anticipate that the Chief Information Security Officer Council’s playbooks documenting security best practices for IoT devices, as well as the covered IoT inventory with security controls, mandated by its December 2023 memorandum, will lay the groundwork for further developments in IoT security policy. We plan to monitor OMB’s actions as part of our next biennial review due in December 2026.

Most Agencies Are in the Process of Establishing Inventories of Covered IoT in Accordance with OMB’s Memorandum

OMB’s December 2023 memorandum, issued in response to the act, requires the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies to establish an enterprise-wide inventory of covered IoT assets by the end of fiscal year 2024.[37] According to the memorandum, the inventories are to include, among other things, asset identification with a description of the asset, including its alignment with NIST’s security controls. The inventories are also to include the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend.

More than half of the 23 CFO Act agencies stated that they have developed or plan to develop inventories of their covered IoT assets by the end of fiscal year 2024, in accordance with OMB’s memorandum.[38] Specifically, as of July 2024, of the 23 agencies:

· three stated they have established inventories of their covered IoT assets,

· 10 stated that they will complete their covered IoT inventories by the end of fiscal year 2024,[39]

· three stated that their inventories will not be completed until fiscal year 2025 because of multiple efforts to ensure that their inventories of covered IoT are comprehensive,

· six did not provide time frames for completion of their inventories, and

· one stated that it does not intend to establish an IoT inventory because the agency does not use covered IoT within the agency’s environment.

Given the enormous array of disparate devices that may be considered part of IoT, it is important for agencies to identify and document any of those devices connected to their information systems. Without this, agencies will lack visibility into the IoT devices in their enterprise environments and the ability to mitigate IoT cybersecurity risks. Figure 3 provides a summary of agencies’ reported status in developing and completing their inventories of covered IoT assets.

Figure 3: Summary of Agency-Reported Status of Covered Internet of Things (IoT) Inventory Completion, as of July 2024

Table 3 describes agencies’ reported status of their covered IoT inventories.

|

Agency |

Covered IoT inventory statusa |

Description of inventory effortsb |

|

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend, and will be completed by the end of fiscal year (FY) 2024. |

|

Department of Commerce |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will be developed by the end of FY 2024. Commerce officials stated the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend. |

|

Department of Education |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the agency is in the process of inventorying its IoT assets. Education officials further stated that they are also refining the inventory process to include the critical functions of IoT and that it will be completed around the end of calendar year 2024. |

|

Department of Energy |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend, and will be completed by the end of FY 2024. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend, and will be completed in FY 2025. The officials stated that pilots of supporting solutions are currently underway and the agency is working to share results and incorporate the IoT asset inventory across the department. |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend, and will be completed in FY 2024. |

|

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory development is in its initial stages and will be completed by the end of FY 2024. The officials did not indicate whether the agency’s inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems processes, and assets upon which those functions depend. |

|

Department of Justice |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend, and will be completed by the end of FY 2024. |

|

Department of Labor |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the agency is working on an automated tool to track and identify IoT devices but has not started to include the identification of critical functions for IoT devices. According to Labor officials, this work will be completed by the end of FY 2024. However, Labor does not yet have a time frame for the completion of the inventory because agency officials stated that the department needs to accurately identify the attributes of IoT devices first. |

|

Department of State |

Complete |

Agency officials stated that the inventory is completed and includes asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend. |

|

Department of the Interior |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend, and will be completed by the end of FY 2024. |

|

Department of the Treasury |

Complete |

Agency officials stated that its covered IoT inventory is completed and noted that the department has not identified any IoT devices. |

|

Department of Transportation |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that a comprehensive inventory will be completed in FY 2024, and it will be further matured in FY 2025. The officials stated that asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend will be completed by the end of quarter one of FY 2025. |

|

Department of Veterans Affairs |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend. In addition, the officials stated that they plan to fund and acquire an IoT and medical IoT monitoring tool in early 2025 for inventorying medical devices. The agency officials did not provide a time frame for completing its inventory. |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the agency has conducted an initial inventory of its covered IoT and is continuing its efforts to ensure all IoT assets across the agency are included. The inventory will be completed in October 2024. The officials did not indicate whether the agency’s inventory will include the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend. |

|

General Services Administration |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that while the agency has an inventory of IoT, the agency is working on assessing and defining critical functions for devices and systems. Agency officials stated that they plan to work with the owners of the various systems to ensure that inventories include the required fields, but they did not provide a time frame for completing the inventory. |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the agency faces significant resource challenges in developing an inventory of covered IoT assets given competing priorities, the large number of systems, and budget constraints. The officials stated that they would appreciate additional guidance from the National Institute of Standards and Technology regarding requirements and the management of IoT. The officials stated that once the challenges have been addressed, the agency would conduct an inventory of IoT assets. The agency did not provide a time frame for completing its inventory. |

|

National Science Foundation |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend, and will be completed by the end of fiscal year 2024. |

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

Complete |

Agency officials stated that the inventory is complete and includes asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices, as well as the related systems, processes, and assets upon which those functions depend. |

|

Office of Personnel Management |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the agency is in the process of developing the inventory but has not yet documented the critical functions of covered IoT devices. According to the officials, the agency plans to complete the follow-up actions to the initial risk assessment by the end of fiscal year 2024. However, the agency has not yet provided a time frame for completing its inventory. |

|

Small Business Administration |

No inventory |

Agency officials stated that the agency does not intend to establish an IoT inventory because the agency does not use covered IoT within the agency’s environment. |

|

Social Security Administration |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that due to the limited IoT use in the agency, it currently does not have active plans for capturing and cataloging IoT devices. Agency officials stated they do not have a time frame for completing the inventory. |

|

U.S. Agency for International Development |

In progress |

Agency officials stated that the inventory will be completed by the end of fiscal year 2024. The officials added that the inventory will not include asset identification with a description and the critical functions of the covered IoT devices because the agency has not identified any IoT assets. |

Source: GAO summary of agency-reported data. │ GAO‑25‑107179

aCovered IoT are IoT devices, including some operational technology devices, that are embedded with programmable controllers, integrated circuits, sensors, and other technologies for the purpose of collecting and exchanging data with other devices and/or systems over a network. They also facilitate enhanced connectivity, automation, and data-driven insights across devices and systems.

bGiven the timing of the report and due date for the covered IoT inventories, we plan to follow up with agencies regarding their covered IoT inventories as part of our next biennial assessment under the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020, due in December 2026.

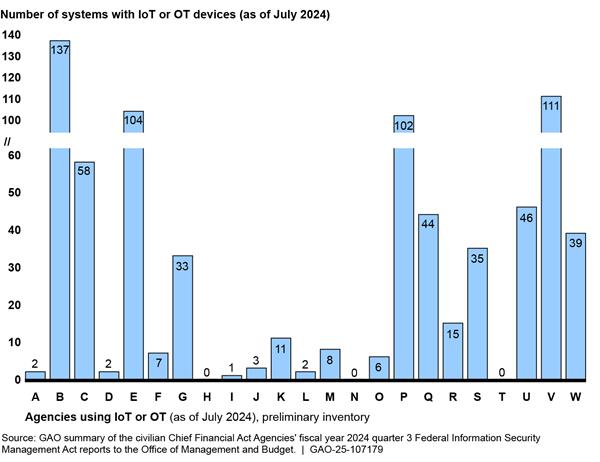

Preliminary inventory reports from agencies identified a range of between zero and 137 systems containing either IoT or OT, or both.[40] Figure 4 depicts agencies’ preliminary inventories of systems using either IoT or OT devices, or both.

Figure 4: Preliminary Inventory of Agency-Reported Systems Using Internet of Things (IoT) and Operational Technology (OT), as of July 2024

Note: The civilian Chief Financial Officer Act agencies are represented by letter because the source data was sensitive. These inventories include systems with IoT devices, OT devices, or both. Additionally, these system counts are not individual devices. Agency officials from the agency with 137 identified systems in its inventory noted that one of its identified systems had over 160,000 network-connected devices.

None of the Six Reported Waivers Were Consistent with the IoT Cybersecurity Requirements

OMB’s December 2022 and 2023 memoranda provide a standardized process for agencies to follow in determining whether to grant a waiver under the act.[41] Specifically, the 2023 memorandum clarifies when and how agencies could waive a prohibition against using IoT devices that do not comply with NIST’s IoT standards and guidelines. The act requires that agency CIOs determine whether an IoT device that would otherwise be prohibited meets one of three waiver conditions.[42] OMB determined that the CIO can then justify such a determination in a signed memorandum to the head of the agency for their approval. Specifically, OMB established the following waiver process:

· The agency head may issue a waiver of the prohibition on use or acquisition of the device in question.

· The waiver must include information about the solutions or platforms covered; a description of the purposes for which or the circumstances in which the device may be acquired or used; and the effective period of the waiver, which may not exceed 2 years.

· The CIOs must make these waivers available to OMB upon request and ensure that such waivers are documented in relevant system security plans and shared with acquisition officials for documentation in relevant contract files.[43]

As part of quarterly reporting to OMB, between June 2023 and June 2024, six agencies reported that they had granted an IoT cybersecurity waiver. These agencies were the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Department of Energy, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC).

However, in following up with these six, officials from five of the agencies stated that they should not have reported waivers. Four of the five subsequently corrected their reported efforts. Specifically, Energy, EPA, NRC, and DOT officials stated that the IoT waivers in their FISMA reports to OMB were data entry errors and not actual waivers. The agencies subsequently corrected the data entry errors in their FISMA reports and the reports now show zero waivers. Additionally, one agency (USDA) corrected its waiver by removing it and one (the Department of Health and Human Services) has not yet corrected its waiver. See table 4 for the status of all reported waivers as of July 2024.

|

Agency |

Status of reported waiver |

|

Department of Agriculture |

Waiver did not address the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) requirements.a Agency officials stated that no waiver was required and stopped reporting the waiver in April 2024. |

|

Department of Energy |

Waiver reported to OMB was a data entry error by a component. Agency corrected the data error in July 2024. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

Waiver did not address OMB’s requirements. It is unclear whether the department plans to address OMB’s requirements for the waiver. |

|

Department of Transportation |

Waiver reported to OMB was an administrative error by a contractor. Agency corrected the data error in October 2023. |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

Waiver reported to OMB was a data entry error by component. Agency corrected the data error in October 2023. |

|

Nuclear Regulatory Commission |

Waiver reported to OMB was inaccurate due to a misunderstanding of OMB’s Federal Information Security Modernization Act (FISMA) reporting instructions. Agency corrected the data element in April 2024. |

Source: GAO analysis of agency data. │ GAO‑25‑107179

aOMB’s requirements note that the waiver must include the following, at a minimum: (1) date of issuance; (2) the device(s) and any associated solutions or platforms covered; (3) a description of the purposes for which or the circumstances in which the device may be acquired or used; (4) the effective period of the waiver, which may not exceed 2 years; (5) a copy of the memorandum setting out the Chief Information Officer’s determination; and (6) the signature of the agency head or their designee.

USDA reported one waiver on an IoT system in its quarterly FISMA submissions from July 2023 to January 2024. Subsequently, USDA officials from the Office of the Chief Information Officer stated that the reported waiver did not meet the requirements under OMB’s guidance and the act. Instead, the waiver decision was made in accordance with NIST’s IoT guidance.[44] As a result, USDA stopped reporting the waiver to OMB and reported zero waivers as of its April 2024 FISMA report.

HHS identified one IoT cybersecurity waiver; however, it did not follow OMB’s waiver process. Among other things, the department did not include a description of the IoT devices, provide a signed memo containing the condition for the waiver, or document the legal authority for the granted waiver.

One impact of the agencies’ errors is that OMB reported erroneous information on waivers to Congress. Specifically, in a December 2023 letter to a Senator regarding the implementation of the IoT Cybersecurity Act of 2020, OMB reported that four systems at four agencies had IoT devices with waivers for not complying with NIST’s IoT standards and guidelines.[45] This error was due in part to OMB not verifying the agencies’ reported data. Best practices for decision-makers include having evidence of sufficient quality to inform decision-making.[46] OMB officials stated that they depend on senior agency officials to ensure that they are collecting and reporting accurate inventories through FISMA. The officials added that OMB holds discussions with agencies if OMB discovers anomalous data in agency reporting. However, OMB did not hold discussions with the above agencies to determine if their reported data was accurate.

Until OMB and agencies ensure data accuracy and compliance with OMB’s established reporting process, the agencies are likely to continue to struggle with identifying, managing, and protecting the numerous operating systems, applications, and devices comprising the federal government’s systems and networks. Moreover, the agencies risk using insecure IoT devices that do not address NIST IoT security guidelines—without the insight or approval of agency CIOs.

Conclusions

In response to OMB’s guidance under the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020, agencies are in the process of establishing inventories of covered IoT. However, not all agencies will meet the deadline for completing them. Some agencies set an alternate time frame for completing their inventories and others did not. Not knowing which devices are connected to their information systems could lead to agencies’ lack of visibility into the IoT devices in their enterprise environments and an inability to mitigate IoT cybersecurity risks.

Agencies have begun to report cybersecurity waivers; however, most were reported in error. While agencies have corrected most of the errors, at the time of our reporting HHS’s waiver had not addressed OMB’s requirements. Not following these requirements could impact HHS’s ability to impose appropriate security requirements and take other mitigating actions. Further, OMB used the reported waiver information without verifying the data and as a result provided erroneous information to Congress. Until OMB and agencies ensure that agencies are meeting OMB’s requirements for establishing inventories and issuing and reporting waivers, they will lack the ability to better secure the government’s IoT devices and systems.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of 11 recommendations, one to OMB and 10 to nine civilian CFO Act agencies. Specifically,

The Director of OMB should verify agency-reported IoT cybersecurity waivers. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Education should direct the CIO to complete the covered IoT inventory within the revised time frame it has proposed. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of HHS should direct the CIO to complete the covered IoT inventory within the revised time frame it has proposed. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Labor should direct the CIO to establish a plan and time frame for completing the covered IoT inventory, as directed by OMB. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should direct the CIO to establish a plan and time frame for completing the covered IoT inventory, as directed by OMB. (Recommendation 5)

The Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency should direct the CIO to complete the covered IoT inventory within the revised time frame it has proposed. (Recommendation 6)

The Administrator of the U.S. General Services Administration should direct the CIO to establish a plan and time frame for completing the covered IoT inventory, as directed by OMB. (Recommendation 7)

The Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration should direct the CIO to establish a plan and time frame for completing the covered IoT inventory, as directed by OMB. (Recommendation 8)

The Director of the Office of Personnel Management should direct the CIO to establish a plan and time frame for completing the covered IoT inventory, as directed by OMB. (Recommendation 9)

The Commissioner of the Social Security Administration should direct the CIO to establish a plan and time frame for completing the covered IoT inventory, as directed by OMB. (Recommendation 10)

The Secretary of HHS should direct the CIO to ensure that granted IoT waivers address OMB’s requirements. (Recommendation 11)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to OMB and the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies for their review and comment. We received responses from all of the agencies, as summarized below. Of the 10 agencies to which we made recommendations, eight agencies agreed with the recommendations and two neither agreed nor disagreed. We also received responses from the other 14 agencies; 12 of which stated that they had no comments and two that provided technical comments.

The following eight agencies agreed with our recommendations in written responses:

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix III, the Department of Education agreed with our recommendation and noted that it planned to complete its inventory of covered IoT by December 2024.

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix IV, the Department of Health and Human Services agreed with both recommendations. It noted that the department is evaluating potential solutions for IoT inventory completion and will develop a target date to finalize the initial inventory. It also noted that the department will work to ensure that granted IoT waivers address OMB’s requirements.

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix V, the Department of Veterans Affairs agreed with our recommendation and noted that the department is currently addressing it. It also had a technical comment which we addressed as appropriate.

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix VI, the Environmental Protection Agency agreed with our recommendation and provided steps it plans to take to finalize OMB’s covered IoT inventory requirements. It noted that the department expects to complete the inventory by February 28, 2025.

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix VII, the General Services Administration agreed with our recommendation. It stated that it had developed its inventory for all covered IoT assets. We were not able to verify the information provided in time to be included in the report.

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix VIII, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration agreed with our recommendation. The department provided steps it plans to take to ensure it has the tools and capabilities in place to conduct such an inventory in future. It noted that the department CIO will submit a plan and budget request to fund the completion of a covered IoT inventory beginning in fiscal year 2027.

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix IX, the Office of Personnel Management agreed with our recommendation. It noted that the department will coordinate a plan and time frame to complete the covered IoT inventory.

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix X, the Social Security Administration agreed with our recommendation. It noted that the department plans to create a unified, accurate IoT inventory by the end of fiscal year 2025.

The following two agencies neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendations:

· In comments provided by email on October 31, 2024, an Assistant General Counsel from OMB stated that the agency had no comments on the draft report.

· In comments provided by email on October 16, 2024, a liaison from the Department of Labor’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy stated that the agency had no comments on the draft report.

The remaining 14 agencies also provided responses.

· In written comments, reprinted in appendix XI, the U.S. Agency for International Development, did not have any comments on the draft report.

· In comments provided via email from relevant agency officials, 11 agencies specified that they had no comments. These agencies are the Departments of Agriculture, Energy, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, the Interior, Justice, State, the Treasury, and Transportation; the National Science Foundation; and the Small Business Administration.

· In an email from an official from the Office of the Executive Director for Operations, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission provided a technical comment, which we addressed.

· In an email from an official from the Management and Organization Office within the Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology, the agency provided technical comments, which we addressed as appropriate.

After receiving a copy of the draft report, four of the 10 agencies that anticipated completing their inventories by the end of FY2024 reported that they had completed their inventories. These four agencies include the Departments of Justice and Transportation, the National Science Foundation, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. Another four agencies (the Departments of Agriculture, Energy, Housing and Urban Development, and the Interior) stated that they plan to complete their respective inventories in 2025. The Department of Commerce noted that it did not complete its inventory and did not yet have an estimated completion date. The Department of Homeland Security did not provide an update. Given the timing of the report and due date for the covered IoT inventories, we plan to follow up with agencies regarding their covered IoT inventories as part of our next biennial assessment under the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020, due in December 2026.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Director of OMB, the heads of the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at 214-777-5719 or at hinchmand@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix XII.

David B. Hinchman

Director, Information Technology and Cybersecurity

List of Committees

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Chairman

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Mark E. Green, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Accountability

House of Representatives

The Internet of Things (IoT) Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 includes requirements for the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Office of Management and Budget (OMB), and the civilian agencies subject to the Chief Financial Officers (CFO) Act of 1990 regarding IoT cybersecurity.[47] It also includes provisions for us to report on efforts to enhance the cybersecurity of IoT. It includes provisions for us to report on IoT procurement guidance and the effectiveness of OMB’s waiver process for selected IoT cybersecurity requirements.[48] Our specific objectives for this review are to (1) describe guidance for securely procuring IoT, and (2) evaluate agencies’ progress in addressing IoT cybersecurity and waiver requirements.

To address our first objective, we identified federal agencies with cybersecurity or acquisition responsibilities. These agencies included OMB, NIST, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council. We then identified and described guidance, recommended practices, and regulations for the acquisition of technologies, including IoT, issued by federal agencies with cybersecurity or acquisition responsibilities. We selected those that covered the procurement of secure IoT. We validated the guidance and practices with the agencies and made changes as appropriate.

To address our second objective, we compared selected requirements of the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 against OMB’s efforts to implement them. We also assessed the act’s and OMB’s requirements for IoT cybersecurity and implementation of those requirements. These requirements include OMB reviewing agency policies to ensure alignment with NIST’s IoT standards and issuing guidance, as necessary; agencies developing inventories of IoT assets; and agencies issuing waivers as appropriate in accordance with the requirements. We then reviewed the agencies efforts to develop inventories of covered IoT and granting waivers for IoT devices that do not comply with NIST standards.

We evaluated documentation from OMB such as OMB’s memoranda in fiscal years 2023 and 2024 implementing the Federal Information Security Modernization Act and IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020.[49] We also evaluated documentation from the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies on IoT cybersecurity efforts, as they are the agencies covered by the review and waiver provisions of the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020. We did not include the Department of Defense because it is not covered by those provisions.[50]

We also reviewed the CFO Act agencies’ cybersecurity policies such as IT security policies and directives. We also reviewed the agencies’ Federal Information Security Modernization Act quarterly reports from July 2023 to July 2024. We compared these efforts to the requirements in the act and requirements from OMB memoranda. We summarized information on the number of waivers OMB and the covered CFO Act agencies reported and granted under the act and under OMB’s implementation guidance. For both objectives, we met with relevant agency officials to obtain their views and verify the information provided.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: Proposed Changes to the Federal Acquisition Regulation That Could Impact Federal Internet of Things

The Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council is responsible for managing changes in the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). Revisions to the FAR are prepared and issued through the coordinated action of two councils, the Defense Acquisition Regulations Council and the Civilian Agency Acquisition Council. Table 5 describes proposed changes to the FAR that could impact the use and cybersecurity of federal Internet of Things (IoT).

Table 5: Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) Proposed Changes that May Impact Federal Internet of Things (IoT) or Other Network Connected Devices as of September 2024

|

Proposed FAR changes (by Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council-identified case number) |

Description and status |

|

FAR case 2017-016, “Controlled Unclassified Information” |

Would implement regulations to address agency policies for designating, safeguarding, disseminating, marking, and disposing of controlled unclassified information, including such information stored on or processed by IoT and operational technology (OT). FAR staff is in the process of resolving open issues identified during Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) review. |

|

FAR cases 2018-017, “Prohibition on Certain Telecommunications and Video Surveillance Services or Equipment,” and 2019-009, “Prohibition on Contracting with Entities Using Certain Telecommunications and Video Surveillance Services or Equipment” |

Would prohibit the procurement of certain telecommunications and video surveillance equipment and services, including IoT and OT, from several foreign technology companies. FAR staff is reviewing comments from the public and in the process of drafting the final rule. The team’s report is due in October 2024. |

|

FAR case 2020-011, “Implementation of Federal Acquisition Security Council Exclusion Orders” |

Would implement a process in which orders based on the recommendations of the Federal Acquisition Security Council to exclude certain products, services, or sources, to include IoT and OT, from the federal supply chain are implemented. This was issued as an interim final rule in October 2023. The FAR staff is reviewing comments from the public and is in the process of drafting the final rule. The team’s report is due in October 2024. |

|

FAR case 2021-017, “Cyber Threat and Incident Reporting and Information Sharing” |

Would implement requirements of Executive Order 14028 relating to sharing of information about cyber threats and incident information and reporting cyber incidents, to include information related to IoT and OT devices. The FAR staff is reviewing comments from the public and in the process of drafting the final rule. The team’s report is due in October 2024. |

|

FAR case 2021-019, “Standardizing Cybersecurity Requirements for Unclassified Federal Information Systems” |

Would implement requirements of Executive Order 14028 relating to standardizing common cybersecurity contractual requirements across federal agencies for unclassified federal information systems, including IoT or OT located within the boundary of the system, pursuant to the Department of Homeland Security’s recommendations. It is also intended to implement the IoT Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020. The FAR staff is reviewing comments from the public and in the process of drafting the final rule. The team’s report is due in October 2024. |

|

FAR case 2019-018, “Federal Acquisition Supply Chain Security Act of 2018” |

Would partially implement a section of the Federal Acquisition Supply Chain Security Act of 2018. This law, part of the SECURE Technology Act, establishes the Federal Acquisition Security Council and its functions and authorities as well as supply chain risk assessment requirements for executive agencies. |

|

FAR case 2019-014, “Strengthening America’s Cybersecurity Workforce” |

Would implement Executive Order 13870, America’s Cybersecurity Workforce, which directs agencies to incorporate the National Initiative for Cybersecurity Education Framework lexicon and taxonomy into contracts for IT and cybersecurity services. Contracts for IT and cybersecurity services must include reporting requirements that will enable agencies to evaluate whether personnel have the necessary knowledge and skills to perform the tasks specified in the contract, consistent with the framework. Staff from the Defense Acquisition Regulation and FAR staff are in the process of resolving open issues with the proposed draft rule. |

|

FAR case, 2023-008, “Prohibition on Certain |