VETERANS CRISIS LINE

Actions Needed to Better Ensure Effectiveness of Communications with Veterans

Report to the Chairman, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-25-107182, a report to the Chairman, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, U.S. Senate.

For more information, contact: Alyssa M. Hundrup at hundrupa@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

An average of 17.6 U.S. veterans died by suicide per day in 2022—the most recent data available. This was more than double the rate for nonveterans. Preventing suicide is a top stated priority of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). VA runs the Veterans Crisis Line: a 24/7 phone, chat, and text service, staffed by crisis responders who support veterans and their family and friends (i.e., customers).

GAO Key Takeaways

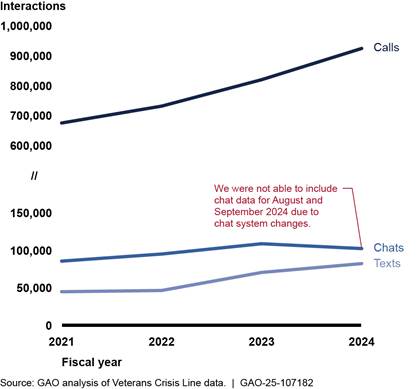

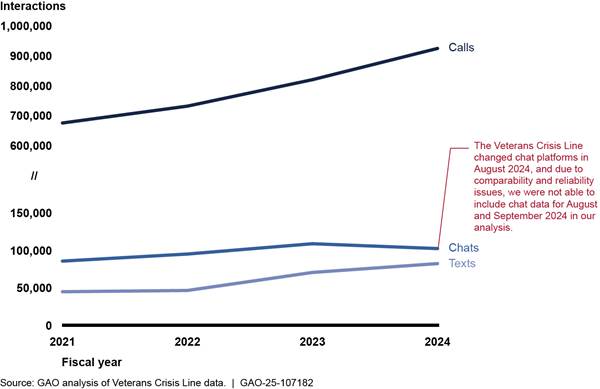

Crisis line data show it had about 3.8 million customer interactions from fiscal year 2021 through 2024, with the number increasing each year (see figure). We found the crisis line faces challenges:

· Customers with complex needs. The crisis line provides specialized training to responders in a unit that addresses complex callers. However, these callers are increasingly being routed to responders who may not have received the training, raising service quality and staffing concerns that could put customers at risk.

· Chat and text. Procedures for staff in this unit—such as responding to more than one customer at once—as well as how the unit is staffed may have adverse effects, including increased customer wait times and responder burnout, which could also put customers at risk.

Further, in July 2024, VA determined that, as a non-clinical service, the procedure the crisis line was using to disclose incidents to customers or their representatives in cases when actions or inactions created a significant risk of harm to the customer was not applicable. The crisis line withdrew the procedure and a new one has not been established. This runs counter to VA’s goal of building trust with stakeholders through transparency and accountability.

How GAO Did This Study

We obtained, reviewed, and analyzed crisis line documents as well as data from fiscal years 2021 through 2024; interviewed crisis line officials; surveyed all crisis line responders and conducted interviews with a non-generalizable sample of eight responders.

What GAO Recommends

VA should ensure the crisis line more comprehensively assesses risks of adverse effects for its customers with complex needs and those using chat and text, making adjustments to procedures and staffing, as needed; and ensure that it has a procedure for disclosing incidents. VA agreed with GAO’s recommendations and identified steps VHA plans to take to implement them.

Abbreviations

CWCN customers with complex needs

VA Department of Veterans Affairs

VCL Veterans Crisis Line

VHA Veterans Health Administration

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 2, 2025

The Honorable Jerry Moran

Chairman

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

United States Senate

Veterans suffer a disproportionately high rate of suicide compared to non-veterans. In 2022, the suicide rate for U.S. veterans was more than twice as high than for nonveterans and an average of 17.6 veterans died by suicide per day.[1] Suicide prevention is the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) top stated clinical priority, according to its strategic plan.[2] To this end, VA operates the Veterans Crisis Line (VCL). The VCL is a 24/7 national toll-free number, online chat, and text messaging service for qualifying individuals. In addition to veterans themselves, the VCL serves veterans’ family members and friends.[3]

As of March 2025, the VCL employed more than 1,000 crisis responders, all of whom answer phone calls on the VCL’s main phone line from customers (how the VCL refers to individuals that contact the crisis line). A subset of responders is assigned to a “customers with complex needs” (CWCN) unit, which handles complex or high-frequency callers on a separate line. Another subset of responders is assigned to the digital services unit, which handles chat and text-based crisis support. In addition to the training all crisis responders receive, CWCN and digital services units’ responders are to receive specialized training specific to those units.

Since 2016, we and the VA Office of Inspector General have raised questions about various aspects of VCL operations, including call wait times, the provision of crisis services, and oversight and quality assurance.[4] More recently, media reports have described allegations of inadequate staffing and training at the VCL, specifically within the CWCN unit.[5] You asked us to further review the VCL’s operations.

In this report, we:

1. describe data on VCL interactions—calls, texts, and chats—for fiscal years 2021 through 2024;

2. examine VCL procedures for operating the crisis line; and

3. examine VCL’ s monitoring of crisis responders’ call, text, and chat interactions.

To describe data on VCL calls, texts, and chats for fiscal years 2021 through 2024, we obtained national data for those years from the VCL. The VCL uses different systems for each medium (call, text, and chat) and thus, we obtained data from each system separately. For each medium, we analyzed the volume of customer interactions, wait times for calls, response times for text and chats, and other variables.[6]

To examine VCL procedures for operating the crisis line, we reviewed VA and VCL documentation, such as on procedures for handling customer interactions as well as for staffing and training crisis responders, and interviewed VCL officials about them.[7] We analyzed available VCL data related to crisis responder staffing and workload.[8] We also analyzed data from the VCL’s CWCN database to determine whether the VCL was reviewing CWCN interventions in accordance with VCL policy.[9]

In addition, we surveyed all VCL crisis responders and asked closed-ended and open-ended questions on topics including VCL procedures, workload and work environment, and training. The survey had a response rate of 51 percent, and, as such, our results could be subject to nonresponse bias.[10] We did not analyze differences between the populations who did and did not respond, and therefore, crisis responders’ answers cannot be generalized to the full population of responders at the VCL. To obtain more in-depth information on topics covered in our survey, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a non-generalizable sample of eight crisis responders.[11] Finally, we evaluated the VCL’s procedures for operating the crisis line against federal internal control standards, such as those related to identifying and responding to risks, and the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) directive on VCL operations.[12]

To examine VCL monitoring of crisis responders’ calls, text, and chat interactions, we reviewed the data that the VCL uses to monitor incoming customer interactions, as well as VHA and VCL policies related to establishing data metrics and related goals. We also examined other relevant VHA and VCL documentation. This included the standards the VCL has set for responders’ interactions with customers and procedures for responding to incidents, and interviewed VCL officials on these topics.[13] Additionally, we analyzed monthly VCL data on the results of VCL quality assurance reviews from fiscal year 2023 through fiscal year 2024. We compared the results of our analysis against documents developed by the VCL to improve responders’ compliance with quality assurance standards. We also reviewed VCL documentation for a non-generalizable sample of critical incidents and veteran suicides not categorized as critical incidents to provide illustrative examples of how the VCL responded after receiving a report of a potential incident involving the VCL’s interaction with a customer.[14] We compared the results of our examination of the VCL’s monitoring of incidents against the goals stated in VA’s strategic plan.[15]

To assess the reliability of each data source above, we reviewed related documentation, interviewed VCL officials on procedures VCL uses to collect and store the data, and performed electronic testing to identify any missing data and obvious errors as appropriate. Based on this assessment, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives. For our full scope and methodology, see Appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

According to VA’s Strategic Plan, suicide prevention is VA’s stated top clinical priority for fiscal years 2022 through 2028. The department has funded and implemented numerous suicide prevention programs.[16] VHA’s Office of Suicide Prevention is responsible for overseeing these programs, including the VCL.[17]

VCL History

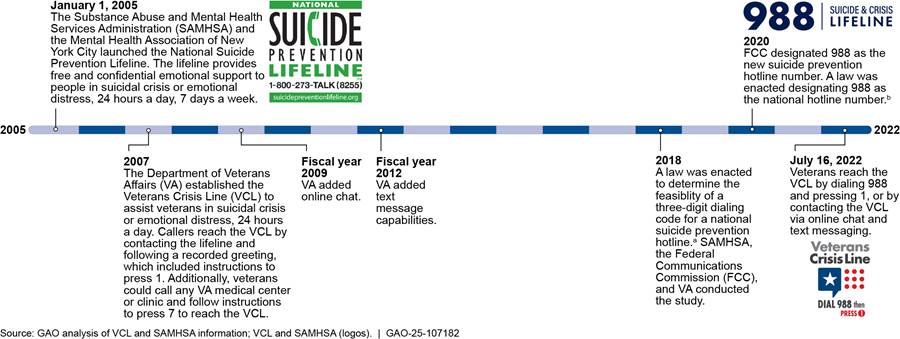

Starting in 2022, customers reach the VCL by phone by pressing 1 after dialing the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline’s 988 number—a general line that provides support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress; or by contacting the VCL via online chat and text messaging.[18] The VCL started as a phone line only, which customers reached through the Lifeline’s previous 1-800 number and pressing 1 or by contacting any VA medical center or clinic and pressing 7. See figure 1 for more information on the VCL’s history.

aNational Suicide Hotline Prevention Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-233, § 3, 132 Stat. 2424 (2018).

bNational Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-172, § 3, 134 Stat. 832 (2020).

VCL Staffing and Budget

When the VCL was first established in 2007, it employed 14 crisis responders in one call center. As it added online chat and text messaging capabilities and the volume of calls, chats, and texts to the VCL grew, it progressively increased the number of responders. The VCL also opened two additional call centers in 2016 and 2018.

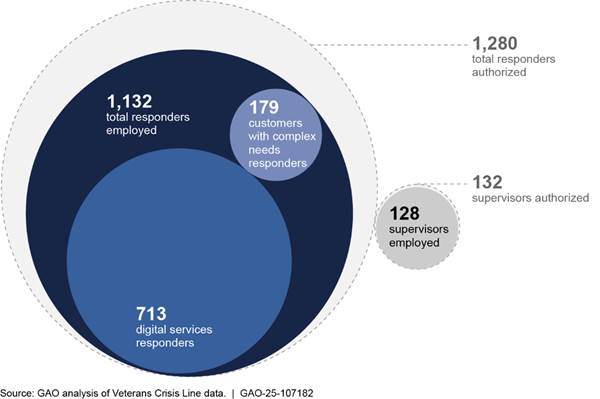

Beginning in 2021, in anticipation of increased demand for its services following the rollout of the national hotline (‘988 press 1’), the VCL significantly increased its staffing levels, and has continued to do so in the years since. Starting in 2024, the VCL also began to increase the number of crisis responders able to work in its CWCN and digital services units. For example, the number of responders trained to work in the digital services unit grew from 314 in May 2024 to 713 in March 2025, and those trained to work in the CWCN grew from 121 to 179 in this same time frame, according to VA staffing data. The VCL’s fiscal year 2024 budget totaled about $300 million.

As of March 2025, VA authorized the VCL to employ 1,280 crisis responders and 132 crisis responder supervisors, an increase from 916 authorized crisis responder positions and 90 authorized supervisory positions in March 2021 (see figure 2.).[19]

VCL officials stated that, as of March 2025, responder staffing levels had not been impacted by recent VA staff reductions, but it is unclear how ongoing and planned efforts to reduce VA staffing levels will impact the VCL’s operations in the longer term.

VCL Training

All crisis responders must take training as a prerequisite to customer interaction. This training includes classroom and on-the-job training, in which experienced responders observe trainees during live calls. The VCL also provides ongoing training for responders through its Training Management System, including to address policy and procedural changes.

Additionally, responders serving in the CWCN and digital services units must take training specific to those units.

· CWCN training is a 32-hour program that includes classroom instruction on procedures like utilizing specific behavioral management techniques to help CWCNs reduce their reliance upon the VCL and escalating interactions to management. It also includes shadowing and being observed by more experienced CWCN responders during live calls. In June 2024, according to officials, the VCL transitioned from having CWCN training run within the CWCN unit to having it run by the VCL training group, in part to increase training availability. Officials indicated that in the first 3 months since this change, 56 responders received CWCN training. Prior to the transition, from fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2023, the VCL trained an average of 25 responders per year.

· Digital services training includes two courses with instruction for using chat and text platforms, as well as skills for text and chat-based communication, such as conversational writing. After completion of these courses, responders are to have on-the-job-training, in which they are observed by other responders experienced in chat and text. As of May 2024, the VCL began preparations to train all phone responders for digital services after working as a main phone line responder for 6 months.

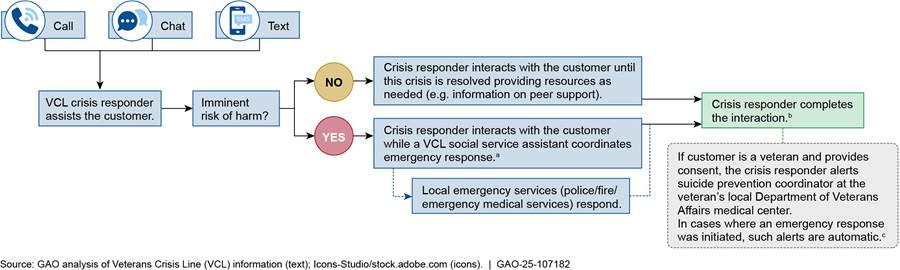

VCL Customer Interactions

The VCL expects all responders to mitigate customers’ risk for harm, whether interacting by call, text, or chat. More specifically, responders are expected to perform tasks including conducting risk assessments to identify suicide or other risk factors, addressing the crisis presented, and seeking supervisory guidance when needed, all to ensure safety for each customer, per VCL policy.

When there is risk of imminent harm that responders are not able to mitigate, the VCL expects responders to work with its social service assistants to coordinate an emergency response or welfare check. In turn, social service assistants are to convey information to emergency services to allow emergency dispatch to locate a customer in need. VCL social service assistants also assist with facility transport plans and notify suicide prevention coordinators at VA medical centers about VCL customers with urgent or emergent mental health care needs.[20]

VCL responders answer customer phone calls individually, but may have concurrent interactions for texts and chats, in which they are responding to more than one customer at the same time. The VCL expects responders to document interactions in the VCL’s records management system, Medora. The VCL also provides post-call follow-up, such as caring letters and peer support service calls.[21] (See figure 3.)

aEmergency response could include an emergency dispatch or a facility transport plan to ensure a customer gets to a treatment facility safely.

bFor calls, the crisis responder completes documentation of the interaction once the call is completed. For chat and text, they must complete documentation at the same time as ongoing chats and texts.

cSuicide prevention coordinators at VA medical centers are responsible facilitating the resolution of customers’ needs as identified in the VCL’s alert as well as re-assessing the customer for any potential risk. This includes facilitating mental health care follow-up, through a VA medical center or community referrals, when applicable, within three business days.

Customers with Complex Needs

The VCL created the CWCN unit in 2017 to manage customers who call at a high frequency, as well as those who are abusive, exhibit sexually inappropriate behavior, or make threats of violence toward VCL staff. The CWCN unit only serves customers who contact the VCL by telephone, as opposed to online chat or text messaging.

VCL considers customers for placement in the CWCN based on reports that crisis responders electronically submit to the VCL Disruptive Behavior Review Team. This team is comprised of former crisis responders with varying mental health backgrounds and advises on issues related to disruptive behavior reports, according to VCL officials.[22] This team reviews the customer’s behavior on any prior VCL calls and determines whether to designate the customer as a CWCN and, if so, what interventions for engaging with the customer during future interactions should be applied. The VCL’s telephone system flags all CWCNs to notify crisis responders who answer their calls that they will be interacting with a CWCN. To have the CWCN flag removed, the Disruptive Behavior Review Team must determine that applied interventions are no longer appropriate.

VCL Customer Interactions Increased by Nearly 40 Percent from Fiscal Year 2021 through 2024

From fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2024, VCL data show the crisis line had about 3.8 million customer interactions.[23] Calls comprised most of these interactions, at 83 percent, chats comprised 10 percent, and texts the remaining 7 percent. While texts comprised the smallest percentage, they also represented the most rapid rate of growth over the time period, increasing by over 80 percent, compared with nearly 40 percent for interactions overall (see figure 4).

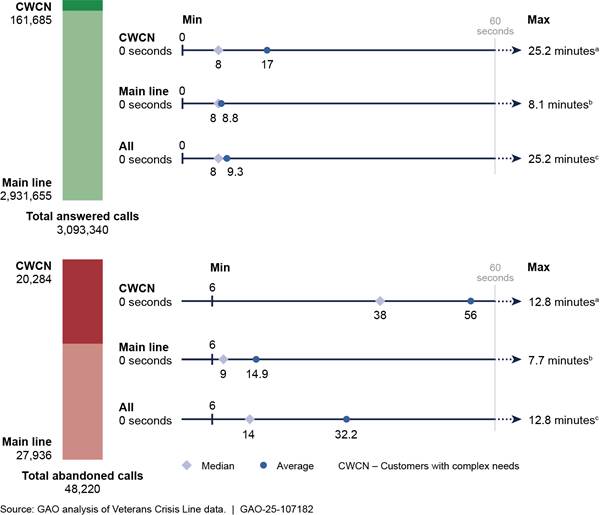

VCL calls. VCL data show that 94 percent of the 3.1 million calls to the VCL from fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2024 were routed to a main phone line responder; those routed to a CWCN crisis responder comprised the remaining 6 percent. Answered calls—99 percent of all calls—had an average wait time of 9.3 seconds and a median wait time of 8 seconds; wait times for calls that were ultimately abandoned were longer, as were wait times for calls to the CWCN. (See figure 5.)[24]

Note: As recommended by Veterans Crisis Line officials, we excluded the time CWCNs spent waiting in a queue (i.e., a predetermined hold) in our calculations of wait times, because time in queue does not reflect how quickly the crisis line is able to answer a call.

aWe found that 0.03 percent (51) of answered CWCN calls and 0.06 percent (12) of abandoned CWCN calls had wait times longer than 4 minutes.

bWe found that 0.002 percent (54) of answered main line calls and 0.05 percent (14) of abandoned main line calls had wait times longer than 4 minutes.

cWe found that 0.003 percent (105) of all answered calls and 0.05 percent (26) of all abandoned calls had wait times longer than 4 minutes.

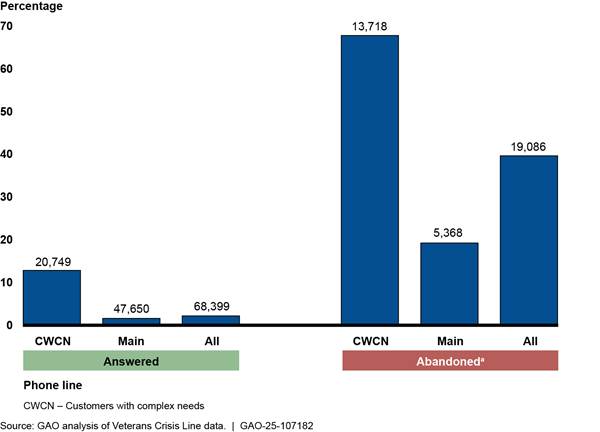

The VCL has set a service goal of answering 95 percent of calls within 20 seconds or less. For calls, in the aggregate, VCL met this goal over the time period of our review. However, it fell short of this goal for calls that were abandoned—that is when callers hung up before a responder answered—or were routed to the CWCN. (See figure 6.)

Figure 6: Veterans Crisis Line Calls with Wait Times Longer than 20-Second Maximum Goal, Fiscal Years 2021-2024

Note: As of March 2024, CWCN callers were automatically redirected to a main line responder if there were not CWCN responders immediately available. Previously, this redirection occurred after 180 seconds. Callers waiting for the main line were redirected to the CWCN if there was no responder availability after 60 seconds. In both cases, callers would be redirected back to the line to which they were originally routed if a responder on that line became available before a responder on the line to which they were redirected.

aAbandoned calls are those in which callers hang up before a responder answers. While reasons for abandoned calls can vary, some callers likely hang up because they had to wait too long.

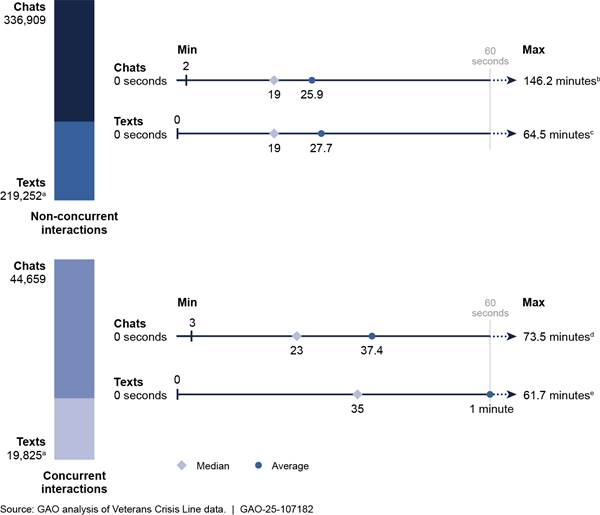

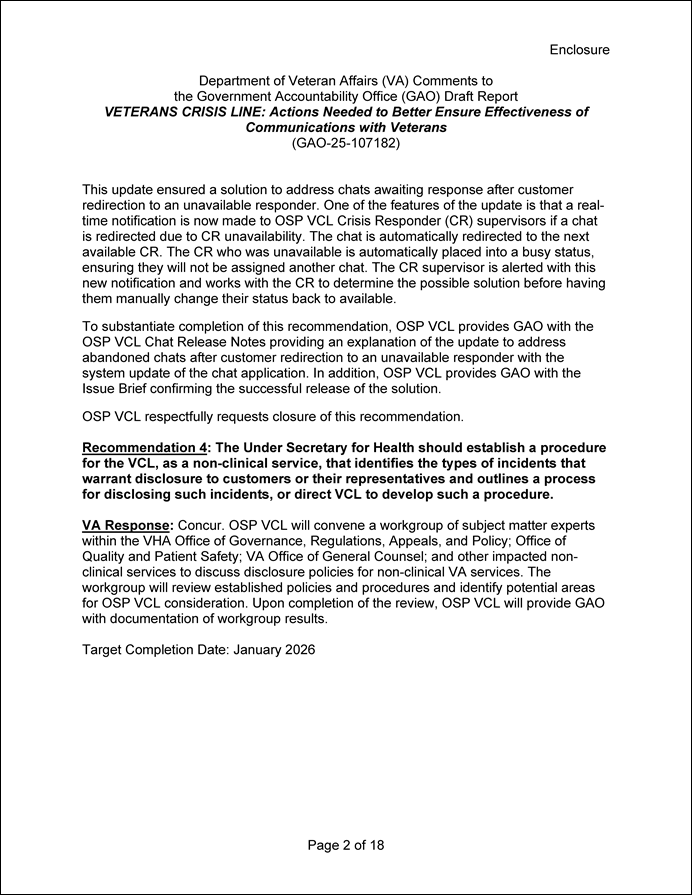

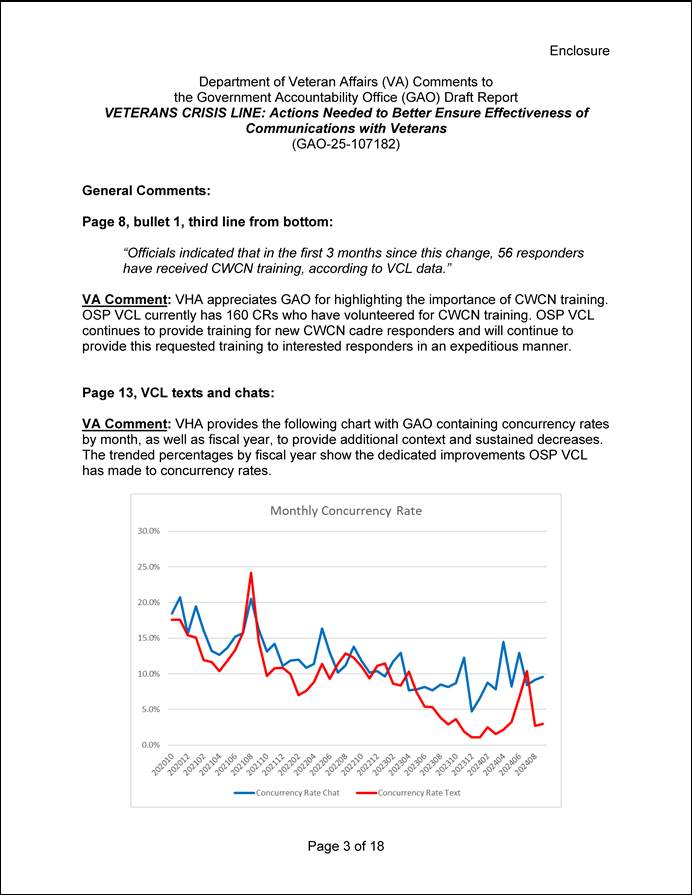

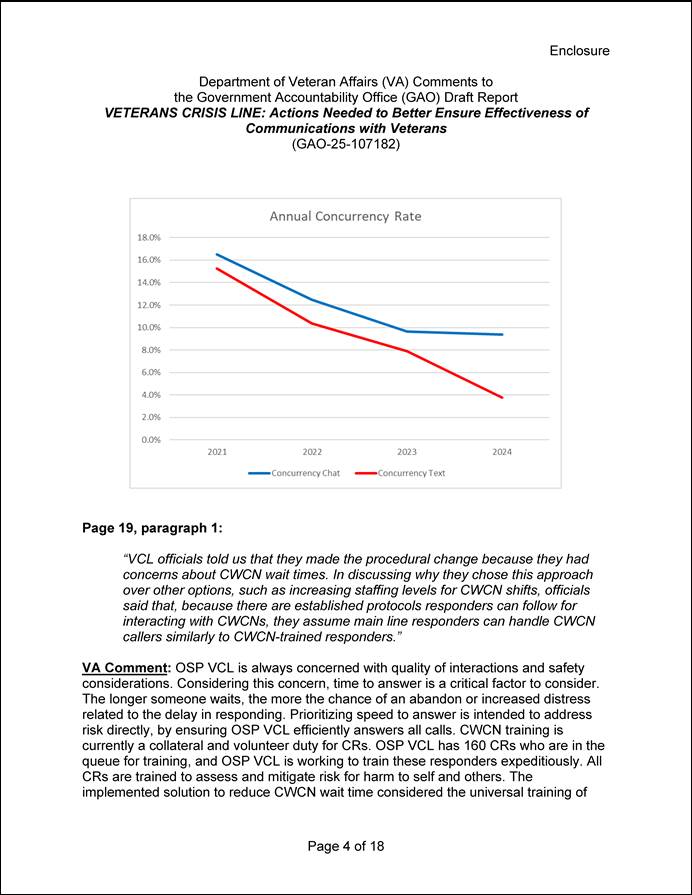

VCL texts and chats. From fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2024, crisis responders answered 98 percent of the 243,517 texts to the VCL and the 391,007 chats received, according to VCL data. Concurrent interactions (those handled at the same time as at least one other text or chat) were more likely to be abandoned and made up 8 percent of texts and 12 percent of chats over the time period.[25]

It also took crisis responders longer to send initial responses for concurrent texts and chats once answered. For example, responders answered non-concurrent texts in less than 30 seconds, on average; average response time more than doubled (1 minute) for concurrent texts (see figure 7).[26]

Notes: The VCL changed chat platforms in August 2024, and due to comparability and reliability issues, we did not include chat data for August and September 2024 in our analysis. Concurrent interactions are interactions where responders are handling a text or chat at the same time as at least one other text or chat.

aWe excluded 10 non-concurrent interactions and one concurrent text interaction due to missing response times.

bWe found that 0.3 percent (1,139) of non-concurrent chats had response times longer than 4 minutes.

cWe found that 0.2 percent (350) of non-concurrent texts had response times longer than 4 minutes.

dWe found that 1.2 percent (528) of concurrent chats had response times longer than 4 minutes.

eWe found that 1.9 percent (382) of concurrent texts had response times longer than 4 minutes.

For texts and chats customers abandoned before a responder answered (2 percent or 13,868 of all texts and chats), we found that customers generally waited for longer periods of time before abandoning an interaction, compared with interactions that responders answered. For example, for texts, customers waited an average of 30.5 seconds for those that were answered and an average of 2.6 minutes when they decided to abandon the interaction. Likewise, for chats, customers waited an average of 27.3 seconds for those that were answered and an average of 1.6 minutes when they decided to abandon the interaction.

VCL Has Procedures in Place for Operating Its Crisis Line, but Procedures Related to CWCN and Digital Services Units May Pose Risks to Customers

VCL Has Detailed Procedures to Manage Its Phone Line

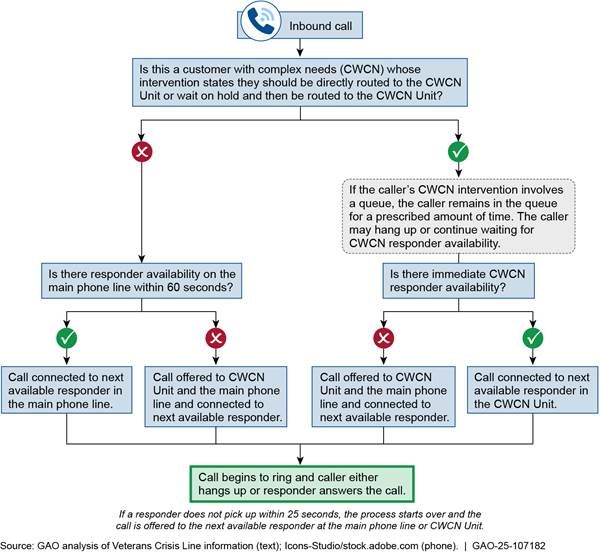

We found the VCL has detailed procedures in place for managing its phone line, including call flows that dictate how calls are routed to responders, both for the main phone line and for the CWCN (see figure 8).[27]

The VCL has a variety of other key procedures for managing its phone line.

Procedures for handling CWCNs. CWCNs can have one or multiple interventions applied, including:

|

VCL Reviews of Interventions for Customers with Complex Needs Based on our analysis of entries from the VCL’s customers with complex needs (CWCN) database from October 1, 2022, through May 9, 2024, the VCL was generally reviewing interventions for CWCNs in accordance with its policy. Specifically, we found the following: Queued interventions: VCL reviewed 89 percent of entries (3,518 out of 3,942) within 7 days per policy, and 98 percent within 9 days (3,854 out of 3,942); Routed interventions: VCL reviewed 89 percent of entries (1,420 out of 1,596) within 90 days per policy, and 98 percent within 92 days (1,560 out of 1,596); Protocol interventions: VCL reviewed 81 percent of entries (4,354 out of 5,369) within 90 days per policy and 97 percent (5,201 out of 5,369) within 92 days. We examined entries completed 2 days beyond the deadline to account for weekends, holidays, or other additional days beyond the VCL’s control. Source: GAO analysis of Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) data. | GAO‑25‑107182 |

· Customers may have individually tailored protocols attached to their phone numbers that responders—whether in the CWCN unit or the main phone line—are to use for guidance as to how best engage and meet the needs of the customer. VCL policy requires that the Disruptive Behavior Review Team review these protocols every 90 days to determine if the protocol is still appropriate for the customer.[28]

· Customers may be routed directly to the CWCN unit in which CWCN responders are specially trained to provide services to complex callers. VCL policy requires that the Disruptive Behavior Review Team review routed CWCNs every 90 days to determine if routing is still appropriate for the customer.

· Customers may be placed in a temporary queue (according to officials, either 10 or 30 minutes) before being routed to the CWCN unit.[29] This practice is intended to help CWCNs modify their behavior with responders. While in a queue, the CWCN hears a “caring message” about why they are waiting for a response, how to shape their behavior to be removed from a queue, and what to do if in crisis. VCL policy requires that the Disruptive Behavior Review Team review queued CWCNs weekly to determine if queuing is still appropriate for each customer.

Procedures for handling abusive customers on the main phone line. As of December 2024, responders are instructed to try redirecting a customer’s behavior once before disconnecting the call if the redirection does not work, for abusive customers not directly routed to the CWCN unit, whether identified as CWCNs or not, according to officials.[30]

· For high frequency or prank callers, responders must follow standard procedure and assess suicide or homicide risk first, as they would for other customers.

· If a customer is being sexually inappropriate or otherwise abusive towards a responder, the responder does not need to conduct a full assessment. However, according to VCL officials, responders cannot disconnect with callers if risk of harm to self or others has been identified in the interaction. Instead, the responders should continue with the interaction until the risk can be mitigated.

Prior to December 2024, responders were instructed to redirect an abusive customer’s behavior twice before transferring the customer to the CWCN unit through a specific phone extension. The VCL plans to examine the effects of the policy change on responders and customers as part of an ongoing assessment of CWCN policies.[31]

Procedures for documenting interactions with callers. The VCL uses Medora as its records management system, including for customer information. Documentation responders must enter in Medora includes information such as the reason for the interaction, the customer’s level of violent behavior risk, and any resources provided to the customer.[32]

Procedures for calling back customers who hang up or are disconnected. When technology issues occur, the VCL has procedures in place for contacting customers.[33] For example, responders are instructed to call back and leave a voicemail compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, if they suspect technical issues on the call or hear something of concern from the customer before a hang up or disconnection.[34]

The VCL also has procedures in place for staffing responders to main phone line shifts. For example, the VCL’s internal data team develops projections to determine the number of responders needed on the main phone line per shift, according to officials.[35]

VCL also monitors main phone line calls in real time to manage responder availability and to maximize coverage, officials said. For example, if there are fewer than 10 responders available to answer a call, VCL staff will recommend shifting responders working in the digital services or CWCN units to the main phone line. Such recommendations are made by staff assigned to monitor phone line operations, referred to within the VCL as “air traffic controllers.”

VCL Procedure Related to Its CWCN Unit May Pose Risks to Customers

We identified a VCL procedure for CWCN that may pose risks for such customers as well as for responders. In March 2024, the VCL made a procedural change to immediately redirect CWCN callers to available main phone line responders when there is no responder available in the CWCN unit.[36] Previously, this redirection occurred after 180 seconds.

Such main-phone-line staff lack specific training for handling CWCN calls and thus may not be well-equipped to handle such interactions. Specifically, 84 percent of main phone line responders have not received CWCN unit training as of March 2025, according to VCL data, to assist for such complex calls.

VCL data indicate that CWCN wait times and the number of abandoned CWCN calls have dropped since VCL implemented the procedural change.[37] However, the number of calls intended for the CWCN, but redirected to the main phone line, have sharply increased. Specifically, since the procedural change went into effect in March 2024 through September 2024, main phone line responders answered over 6,000 calls intended for the CWCN unit. This represents about a quarter of all calls the CWCN unit answered during this time period. In comparison, less than14,000 such redirects occurred across the prior 3.5 years.

VCL officials said they made the procedural change because they had concerns about CWCN wait times. In discussing why they chose this approach over other options, such as increasing staffing levels for CWCN shifts, officials said that they assume main line responders can handle CWCN callers similarly to CWCN-trained responders because there are established protocols responders can follow for interacting with CWCNs.

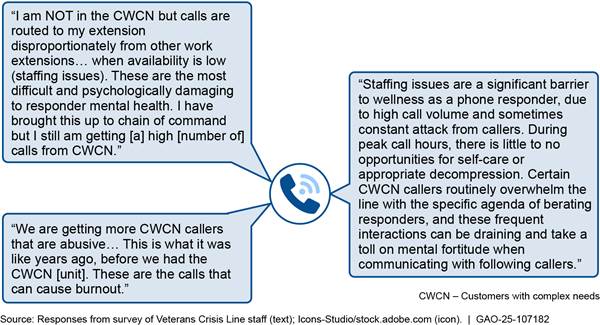

However, in our survey, main phone line responders indicated that they faced problems interacting with difficult or abusive CWCNs. (See Figure 9 for examples.) VCL officials also acknowledged that responders who have not been trained to work in the CWCN unit may struggle during calls and need more recovery time after CWCN interactions.

As such, we found the March 2024 procedural change creates risks that CWCN callers may not consistently receive the service that best meets their needs and that responders may face challenges handling complex callers. According to federal standards for internal control, management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving defined objectives.[38] In addition, according to the VHA directive on VCL operations, the crisis line was established with the goal of optimizing veteran safety through predictable, consistent, and accessible crisis intervention services.[39]

The VCL has taken some steps in this regard, such as examining data on changes in wait times for CWCN calls and in the number of calls main phone line responders answered that were intended for the CWCN unit. However, it has not examined other risks. Most notably, it has not compared the quality of CWCN calls handled by main line phone responders with those handled by CWCN-trained responders, which VCL officials acknowledged would help in understanding whether the shift in CWCN calls to main phone responders provided consistent service for customers.[40]

To the extent complex calls are not handled as effectively by main phone line responders, the increase in these responders answering CWCN calls could lead to problems with service quality and customer safety. It could also lead to operational inefficiencies if, for example, high frequency callers overwhelm the main phone line. Moreover, it could contribute to responder burnout and turnover—the latter of which was 17 percent in 2024.

VCL officials told us they do not have concerns about the turnover rate and have implemented programs to address burnout, such as allowing time for wellness activities when responder availability is high.[41] At the same time, about half of the responders who answered our survey reported feeling burnt out from their work at the VCL. By more fully assessing the risks of the procedural change for customers and responders, the VCL will be able to determine whether the effects are consistent with the goal of optimizing veteran safety outlined in its operations directive or whether other changes are needed.

More comprehensively assessing risk could also help identify if changes to staffing procedures for CWCN unit shifts are warranted. In reviewing VCL procedures for staffing the CWCN unit, we found the VCL does not develop projections to determine needed CWCN responder staffing levels per shift. Instead, it relies on historical staffing targets of five responders per shift—an approach that does not proactively account for changes in CWCN demand by shift and differs from the how the VCL staffs the main phone line.[42] Additionally, VCL air traffic controllers prioritize main phone line responder availability over CWCN responder availability and do not proactively move responders into the CWCN unit (though they will consider requests from the unit for additional staff), according to VCL officials.

As such, depending on the results of its assessment, the VCL may find that adjustments to staffing procedures are needed to ensure there are enough staff working in the CWCN unit to maintain service quality for customers and reduce burnout for responders. These staffing changes could be in addition to or instead of changes to other procedures and would be in line with the VHA directive on VCL operations, which states that the VCL Executive Director is responsible for maintaining appropriate staffing levels to achieve target service levels.[43]

Responders Reported Certain Digital Services Procedures Create Workload Challenges That Could Result in Adverse Effects

The VCL’s procedures for handling digital services customer interactions address similar topics as those for the phone line, such as customer interaction flows, documentation requirements, and responding to customer needs during system outages. However, the procedures also have key differences that we found contributed to workload challenges, especially for the chat platform, identified by responders in interviews and our survey. In particular, responders reported challenges with the digital services procedures including handling concurrent interactions, document requirements, and uneven chat distributions among respondents. (See appendix II for responses to our survey questions related to training, procedures, and workload and work environment).

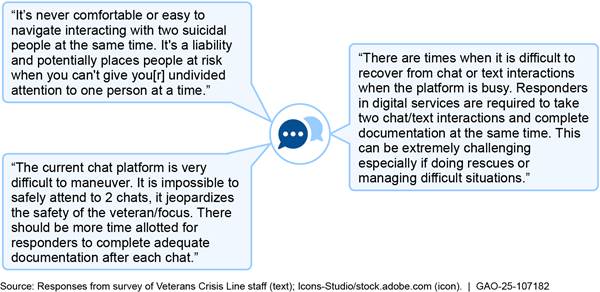

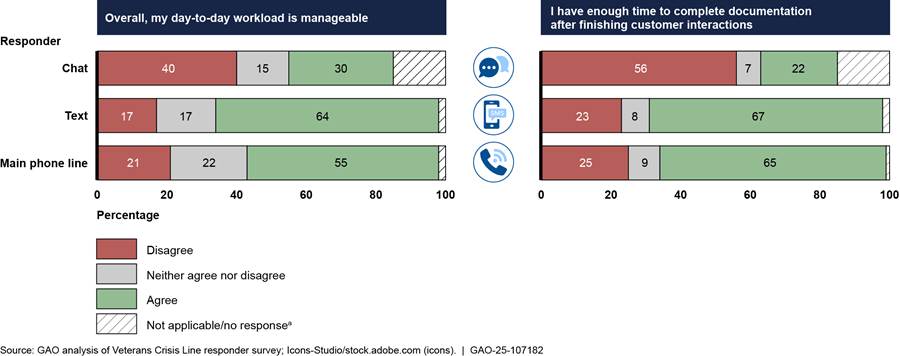

Responders are expected to handle up to two interactions concurrently, as demand requires.[44] Approximately 47 percent of chat responders and 35 percent of text responders who answered our survey indicated that they often or always handle two interactions at once. Responders indicated that this procedure of handling more than one interaction at once can distract from each chat or text conversation and increases their feelings of burnout.

Additionally, our analysis of VA data showed more than 1,500 instances of responders handling more than two concurrent interactions in chat and more than 500 in text from fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2024. This is not consistent with VCL procedures, and officials said it poses risks to customers and should not occur. Officials noted that historically, it was up to responders to accept chats and texts and that responders may have interactions that are idle, giving the responder the confidence to accept other customers. The VCL implemented a new chat platform in August 2024, and the platform limits each responder to two chats at a time, according to officials. There is not a similar limitation available for the text platform.

Responders are expected to document interactions at the same time they are handling active interactions. Responders noted that for calls, they are given time after the call to document their interactions before taking another call. Such time is not given for texts and chats, per VCL officials and responders. Having to do both at the same time can create challenges as it distracts responders from ongoing chats and texts, especially if the responder is handling multiple interactions concurrently, according to responders.

The VCL’s chat algorithm unevenly assigns chats among responders. Responders said the VCL’s chat algorithm assigns many chats to certain responders on a shift and very few chats to others.[45] The VCL updated its algorithm when switching to its new chat platform, but the new chat platform was not implemented with the intention to address the algorithm problem, and responders reported mixed reviews as to whether it has improved chat distribution. The uneven assignment of chats can increase workload and feelings of burnout for responders who are assigned a greater number of chats than their colleagues on the same shift.

See Figure 10 for additional responses provided by digital services responders regarding these procedures and their workload.

Data from our survey corroborate workload challenges within the chat platform. More chat responders indicated challenges with workload compared with text and main phone line responders (see figure 11).

Note: The survey had a response rate of 51 percent, and, as such, our results could be subject to nonresponse bias. We did not analyze differences between the populations who did and did not respond, and therefore, crisis responders’ answers cannot be generalized to the full population of responders at the VCL. Of the 946 main phone line responders who received our survey, 484 submitted responses. Of the 325 chat responders who received our survey, 161 submitted responses, and of the 349 text responders who received our survey, 168 submitted responses.

aMissing/not-applicable responses indicate that a responder taking the survey either skipped the question or indicated that they only served as a responder in the chat unit or text unit and could not provide an answer about the other digital services platform.

We found that the VCL has not adequately assessed the risks associated with the digital services procedures for which responders reported challenges and therefore lacks information on the effects of these procedures. For example, officials said:

· The VCL had a pilot to evaluate the digital services procedure that requires responders to document interactions at the same time they are actively handling interactions.[46] However, the VCL assessed the impact of the procedure for texts, and did not include chats in its evaluation.

· The VCL has not assessed the effects of its chat program’s algorithm for assigning chats on responder workload or the effect of concurrent chats or texts on service quality for customers.

Without such assessments, which would be in accordance with federal standards for internal control for risk management, adverse effects for customers and burnout and turnover among responders may occur. For example, among chat responders who answered our survey, 43 percent stated that their workload can make it difficult to be fully attuned to customers’ needs and to ensure their safety compared with 31 percent of main phone line responders and 35 percent of text responders.

Additionally, customers were more likely to abandon concurrent chats and texts before a responder answered. For example, customers abandoned five percent of concurrent chats compared with 2 percent for nonconcurrent chats, from fiscal year 2021 to fiscal year 2024, according to VCL data. Such effects would be inconsistent with the VCL’s operations directive goal of optimizing veteran safety through predictable, consistent, and accessible crisis intervention services.

More comprehensively assessing the risks associated with its digital services procedures would help the VCL understand whether it might be necessary to adjust its procedures to address responder workload challenges and ensure quality service for customers. It would also help it understand whether it might be necessary to adjust how it staffs digital services shifts to maintain appropriate staffing levels as outlined in the VHA directive on VCL operations.

We found that the VCL lacks data on digital services responders’ workload and, thus, what comprises adequate digital services staffing per shift. For example, officials said the VCL does not have data on how much time digital services responders are spending actively managing chats or texts or documenting interactions. Officials explained that this is because the VCL system that would capture such data shows responders as being assigned to chat or text but does not contain different codes for different digital services responder activities as it does for calls.

VCL officials said they are discussing the feasibility of creating specific codes for digital services responder activities but had not yet taken any steps to develop them. As a result, unlike for calls, the VCL is not able to forecast needed staffing for digital services shifts, including any changes in demand for digital services over time. Instead, the VCL relies on historical staffing targets, which are predetermined numbers based on shift. (For example, the day shift target is 30 responders, and the evening shift is 21.)

Additionally, officials do not have real-time data on digital services’ responder availability. Officials said instead, VCL air traffic controllers rely on digital services’ supervisors to request additional staff when digital services availability is low. Similar to CWCN requests, because the VCL prioritizes main phone line staffing, officials said that requests for additional digital services responders may be denied if availability on the main phone line is in jeopardy of becoming low.

Technical Issue with Identification of Available Responders in the VCL’s Chat Platform May Increase Wait Times for Some Customers

We also found a technical issue with the VCL’s new chat platform, implemented in August 2024, which may increase wait times for some customers. Specifically, officials said under the new chat platform, chat customers may be redirected to a different responder if the initial responder assigned does not accept a chat within 25 seconds of it being assigned to them. However, VCL officials reported that chat customers may be redirected between two responders who are both unavailable, as the chat system does not automatically change the status of responders who are not available to respond (e.g., responders who are on a break or who are experiencing internet outages).

VCL officials explained that customers experiencing redirects when a responder does not accept a chat within 25 seconds are routed to the longest available responder as identified by the system. Thus, if two unavailable responders appear as available in the chat platform, the customer will continue to be redirected between them, because they are identified as the longest available, until eventually one of the responders becomes available, according to officials.

Officials said that with this chat platform issue, chat customers may not reach an available responder in a timely manner, but rather experience long wait times while they are routed between two responders. This could pose a safety concern if customers disconnect before they are able to receive help. Specifically, of the 1,765 chats that were redirected due to a responder not accepting it within 25 seconds between August and November 2024, 136 chats experienced two redirects while 55 experienced three or more, indicating an issue with redirects in the chat platform, according to officials.

VCL officials said they contacted the chat platform provider to discuss modifications that would automatically change the status of unavailable responders, but did not know if or when the provider would implement a permanent fix. In the interim, VCL leadership has asked responders to manually change their status in the chat platform when they are unavailable. Officials said they recognized that this is not an ideal solution as it relies on responders to make the change, which may not consistently occur, especially if a responder is experiencing technical issues and thus is unable to report their availability.

By instructing its provider to remedy how the chat platform identifies responder availability, the VCL will be able to better ensure it is meeting the VHA directive on VCL operations requirement to have adequate services in place to respond appropriately to all requests by customers for assistance.[47] Importantly, it will also then be able to better ensure that every veteran in need of chat services will reach a responder in a timely manner.

VCL Monitors Responders’ Call, Chat, and Text Interactions Using Data and Quality Assurance Reviews, but Lacks a Procedure for Disclosing Critical Incidents

VCL Is Finalizing a Policy for Metrics and Goals to Monitor Call, Chat, and Text Interactions

The VCL monitors incoming call, chat, and text interactions to assess its performance and identify any areas needing improvement, as detailed in the VHA directive on VCL operations.[48] For example, the VCL tracks various metrics, such as the number of incoming interactions, the speed at which interactions are answered, and the percentage that are answered or abandoned. The VCL monitors and updates these metrics regularly and, depending on the metric, shares them with VCL leadership on a daily or monthly basis.

The VCL has also established certain goals associated with metrics for phone calls. For example, the VCL has a service level goal of answering 95 percent of calls within 20 seconds. Additionally, the VCL is in the process of establishing a policy with new goals and metrics for chat and text interactions. For example, based on our review of the VCL’s draft policy, the VCL plans to have service level goals of answering 95 percent of chats and 95 percent of texts each within 45 seconds. VCL officials said they expect to finalize the policy by summer 2025.

VCL Uses Quality Assurance Reviews to Monitor Responder Adherence to Standards for Customer Interactions

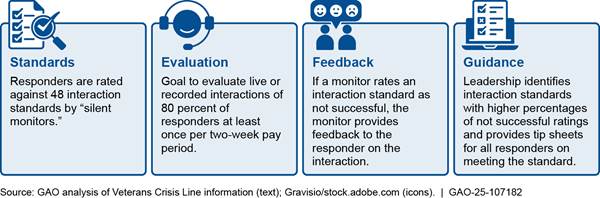

The VCL also conducts quality assurance reviews to monitor responder adherence to customer interaction standards and address deficiencies where needed (see figure 12).

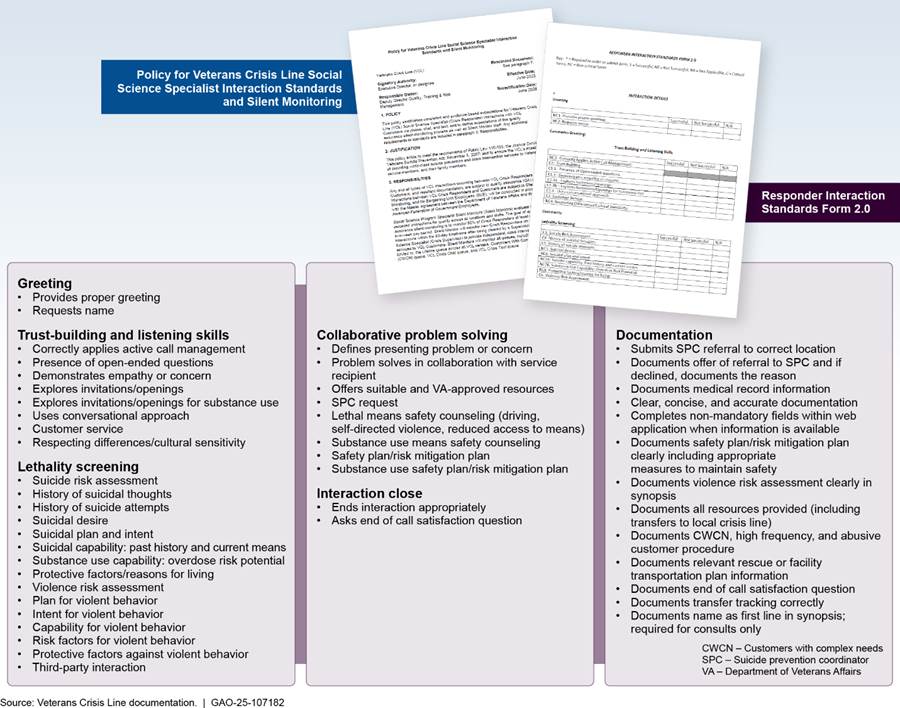

According to VCL policy, any interaction between responders and customers—including calls, chats, or texts—is subject to quality assurance review. The VCL has a goal of conducting quality assurance reviews for 80 percent of responders at least once every two-week pay period.[49] The VCL performs these reviews using silent monitors—staff who evaluate live or recorded interactions for quality using a set of 48 interaction standards, as shown in figure 13.[50]

Note: Each item in the figure above corresponds to an interaction standard. Responders are rated as either successful, not successful, or not applicable for the interaction standards listed in the figure during quality review. For each standard, VCL policy provides details on what constitutes successful, not successful, or not applicable.

The VCL’s interaction standards provide specific criteria to which a responder must adhere to be rated as successful. For example, responders are required to conduct a suicide risk assessment. The criteria for the standard include:

· assessing the risk of suicide directly (e.g., asking the caller “are you thinking of suicide?”) and

· acknowledging the presence or absence of suicidal ideation (e.g., “you began the call by saying you aren’t suicidal; any thoughts of suicide in the past?”).

If the responder does not directly ask the caller or asks the caller using the negative (e.g., “you aren’t thinking of killing yourself, are you?”), then the silent monitor evaluates the responder as not successful.

|

VCL Crisis Responders Generally Expressed Positive Views of Employee Training and Resources Available to Answer Questions Responders who answered our survey, generally expressed positive views of the training they received for their positions as well as the resources available to answer their questions. For example, among all responders who answered our survey: · 77 percent agreed that the training they received before being cleared to take calls as a VCL main phone line responder provided the knowledge and skills needed to perform their duties (7 percent had neutral views on training and 16 percent disagreed that the training provided the knowledge and skills needed to perform their duties). · 62 percent of responders agreed that ongoing training provided the knowledge and skills needed to perform their duties (16 percent of responders had neutral views and 22 percent disagreed). · 76 percent of responders agreed that supervisors are available to answer questions during shifts (8 percent of responders had neutral views and 15 percent disagreed). · 63 percent agreed that they have the resources to clarify policies and procedures when needed (16 percent had neutral views and 21 percent disagreed). Additionally, 74 percent of customers with complex needs (CWCN) responders who answered our survey and 78 percent of digital services responders agreed their training provided the knowledge and skills needed to perform their duties (13 percent of CWCN responders and 8 percent of digital services responders had neutral views, while 13 percent of CWCN responders and 13 percent of digital services responders had negative views of this training). Source: GAO survey of Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) responders. | GAO‑25‑107182 |

If a responder is rated as not successful on any standard, after the call the silent monitor is to provide feedback to the responder on how to correctly adhere to the standard. If the silent monitor observes that the interaction has an unmitigated risk—such as the absence of attempts by the responder to build trust with the caller—then the silent monitor is expected to reach out to the responder’s supervisor for immediate review and resolution.

For example, according to VCL documentation we reviewed, a silent monitor that evaluated a live phone interaction in October 2022, identified that the responder was not maintaining a conversational approach with the customer, which prompted the customer to hang up. According to VCL documentation, the silent monitor alerted the responder’s supervisor who provided coaching to the responder, and the responder contacted the customer to ensure they were safe. The silent monitor rated the responder as not successful on several criteria (including not maintaining a conversational approach) and provided examples of how to improve.

According to VCL policy, VCL quality management is responsible for analyzing quality assurance reviews for patterns of non-successful interactions to ensure quality and support crisis responder development.[51] We found the VCL was meeting this requirement by conducting systematic interventions based on the results of silent monitoring. Specifically, as of June 2023, the VCL started reviewing the monthly results of silent monitoring and began periodically publishing tips—known as “safety moments”— for improving adherence to standards. Safety moments provide additional guidance on how responders should interact with customers to meet the standard.

We found that the 10 safety moments issued by the VCL from October 2022 through September 2024 identified the interaction standards that had among the highest number of evaluations rated not successful during that period.[52] For example, a safety moment in September 2023 identified the interaction standard of “suicide plan and intent” as a challenge and offered tips and example questions on how responders should interact with callers. Our analysis found that for that month, VCL silent monitors rated about 20 percent of interactions as not successful for this standard, and this was among the highest percentage for all standards. (See Appendix III for the full results of our analysis of VCL silent monitoring data.)

VCL officials noted that issuing safety moments provides an opportunity for responders to review guidance and crisis intervention techniques to help address interaction standards with higher rates of being evaluated as not successful. However, because safety moments are relatively new, VCL officials said they are still determining how to make their review and discussion routine for responders, as well as how to assess the extent to which the safety moments are effective.

VCL officials also noted that they have taken additional steps to address interaction standards with low responder performance, such as forming workgroups with VCL quality assurance, risk management, and training staff to discuss how to improve responder performance.

VCL Reviews Customer Suicides and Other Incidents Following Crisis Line Interactions to Determine Its Role, but Lacks a Procedure for Disclosure

Whenever the VCL learns of a suicide or other incident involving a customer following a VCL interaction, VCL policy calls for a review to examine how the VCL interacted with the person involved and whether there was a shortcoming on the part of the VCL that contributed to the incident.[53] The policy also outlines the review process, which includes steps such as silent monitors reviewing the interaction between the customer and the responder to determine whether the responder acted in accordance with VCL standards.

If the VCL determines that an action or inaction by VCL staff, technical failure, or VCL process or gap in process created a significant risk of harm to the customer, VCL policy states that the incident should be categorized as a critical incident.[54] The policy further states that critical incidents include, but are not limited to, the VCL delaying or impeding access to care (e.g., poor customer service, technical issues, inaccurate or misdirected suicide prevention coordinator requests, or emergency dispatch sent to the wrong location). The VCL is to review the details of all potential critical incidents to identify contributing factors and opportunities for improvement.[55]

Based on the sample of critical incidents we reviewed that occurred from October 7, 2022, to March 6, 2024, we found that the VCL has been conducting reviews of incidents and identifying areas for improvement. In particular, for the 17 critical incidents we reviewed, we found that in all cases, the VCL conducted reviews of the relevant interactions and, where applicable, identified an area for improvement and provided coaching to the involved responder.[56]

For example, one critical incident involved a third party calling the VCL to express concerns about a suicidal veteran. While working to get information from the third-party caller, the responder also directed the third party to call 911. After reviewing the incident, the VCL determined that the responder should have conducted a conference call with the third-party and 911 instead of relying on the third-party to call 911 independently. As a result of the review, the VCL provided the responder coaching to initiate a conference call with 911 in future situations.

The VCL, however, lacks a procedure for determining whether to disclose its involvement in critical incidents. Specifically, according to VCL officials, as of July 2024, the VCL withdrew the section of its policy on critical incidents that outlined the procedure for identifying the types of critical incidents that warrant VCL disclosure as well as the subsequent process for disclosing such incidents.

This previous procedure had stated that “suicides and/or homicides that occurred with the VCL as the last known contact within 72 hours and with significant action or inaction on the part of VCL staff that was a contributing factor to the outcome,” would be classified as a sentinel event that would trigger disclosure.[57] The procedure further stated that disclosure should include providing an apology and an explanation of recourse options from the VCL to the customer or the customer’s representative in cases when the customer is deceased.[58]

According to VCL officials, its decision to withdraw its disclosure procedure was based on consultations with other VA offices, including the Office of General Counsel, the Office of Medical Legal Risk Management, and the National Center for Ethics in Health Care. Through these consultations, the VCL determined that the VHA directive the VCL used as a basis for its definition of sentinel events and associated disclosure procedures, is not applicable to non-clinical services within VHA, including the VCL. This is because VCL responders are not considered providers, clinicians, or health care professionals.[59] Additionally, VCL officials said they determined that the VCL is neither legally required nor legally prohibited from making disclosures.

Following its decision, VCL officials said they held additional consultations with applicable VA offices and learned there is not a VHA policy outlining a disclosure procedure for non-clinical services within VHA. VCL officials further stated that because other non-clinical VHA services, such as VHA’s Caregiver Support Line and the Vet Center Call Center, should also likely be covered by a disclosure procedure, they understood it was ultimately VHA’s responsibility to develop an appropriate procedure. In the meantime, the VCL has no procedure for disclosing critical incidents, and officials said it was unclear whether VHA planned to develop one that would apply to the crisis line. According to VCL officials, the VCL continues to seek clarification on disclosure requirements and how they relate to VCL operations.

VCL officials also noted that, from October 2022 through September 2024, no customer suicides were designated as sentinel events and therefore, disclosed. Based on our review of documents for our non-generalizable sample of critical incidents, we agree that the eight deaths by suicide included in this sample did not meet VCL’s criteria for such events. The VCL classified one non-suicide incident that occurred in October 2023 as a sentinel event, but according to VCL officials, the incident was not disclosed because the applicability of the VCL’s disclosure requirements were under discussion at that time.

Furthermore, the Executive Director of VA’s Office of Suicide Prevention said there is no national standard regarding disclosure of incidents that applies to crisis lines. For example, this official said the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the 988 Lifeline have not defined standards for when to disclose incidents. These crisis centers are considering the development of such standards, according to the official, but there is no formal workgroup that involves the VCL.

Establishing a disclosure procedure for the VCL as a non-clinical service would help build trust with stakeholders and be consistent with a goal in VA’s strategic plan. According to its strategic plan, the VA has a goal of building and maintaining trust with stakeholders through proven stewardship, transparency, and accountability, ensuring that VA’s culture of accountability drives ethical behavior and trust across the organization and through the ecosystem of partners.[60] In contrast, the lack of disclosure procedures could result in missed opportunities for the crisis line to hold itself accountable to customers or their representatives.

Conclusions

Suicide prevention is VA’s top stated clinical priority, and the VCL—by providing assistance to veterans in immediate crisis—is an integral part of VA’s efforts. The VCL strives to answer calls as quickly as possible and, to this end, prioritizes staffing its main phone line to meet demand. However, we found that in doing so, the VCL may be exacerbating challenges within its CWCN and digital services units and creating risks to the quality of service it provides to its customers.

Specifically, our review identified several procedures within the CWCN and digital services units that may be creating challenges for customers who contact the VCL as well as for responders. The VCL has not adequately assessed the risk of these procedures, and as a result, the extent to which they could put veterans at risk and result in responder burnout is unknown. More comprehensively assessing the risks of these procedures will allow VA to determine whether changes are needed to better ensure the quality of the service it is providing to veterans and other customers in crisis as well as the well-being of its responders.

Moreover, a technical issue with the VCL’s chat platform may increase wait times for customers to engage with a crisis responder or result in a customer abandoning a chat before a responder answers under certain circumstances. Addressing this issue will help the VCL better ensure that all chat customers receive the help they need.

The VCL also has several efforts in place for monitoring customer interactions—including tracking performance metrics and quality assurance reviews—but withdrew its procedure for determining whether to disclose critical incidents resulting from organizational action or inaction in July 2024. By ensuring the VCL has a procedure for determining the types of incidents that warrant disclosure as a non-clinical service as well as a process for making disclosure determinations, VHA can better guarantee it is meeting VA’s goal of building trust with stakeholders through transparency and accountability.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following four recommendations to VA:

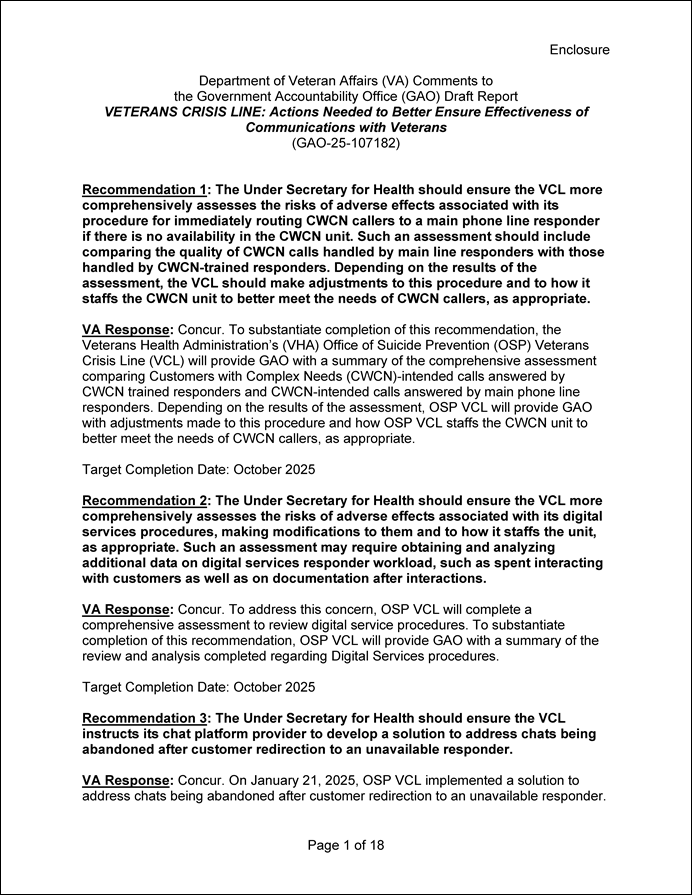

The Under Secretary for Health should ensure the VCL more comprehensively assesses the risks of adverse effects associated with its procedure for immediately routing CWCN callers to main phone line responders when there is no availability in the CWCN unit. Such an assessment should include comparing the quality of CWCN calls handled by main line responders with those handled by CWCN-trained responders. Depending on the results of the assessment, the VCL should make adjustments to its procedure for routing CWCN calls and to how it staffs the CWCN unit to better meet the needs of CWCN callers, as appropriate. (Recommendation 1)

The Under Secretary for Health should ensure the VCL more comprehensively assesses the risks of adverse effects associated with its digital services procedures, making modifications to them and to how it staffs the unit, as appropriate. Such an assessment may require obtaining and analyzing additional data on digital services responder workload, such as time spent interacting with customers as well as on documentation after interactions. (Recommendation 2)

The Under Secretary for Health should ensure the VCL instructs its chat platform provider to develop a solution to address chats being abandoned after customer redirection to unavailable responders. (Recommendation 3)

The Under Secretary for Health should establish a procedure for the VCL, as a non-clinical service, that identifies the types of incidents that warrant disclosure to customers or their representatives and outlines a process for disclosing such incidents, or direct the VCL to develop such a procedure. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to VA on March 12, 2025, and asked for the department’s comments within 30 days. VA requested an extension, which we granted, and provided written comments on May 8, 2025. VA concurred with each of our four recommendations and provided general comments related to issues discussed in this report, which are reproduced in appendix IV. VA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated, as appropriate.

For our first recommendation, VA stated that VHA plans to compare CWCN calls answered by trained CWCN responders to calls answered by main phone line responders. Regarding our second recommendation, VA stated that VHA plans to assess its digital services procedures. For both recommendations, VA provided a target completion date of October 2025.

For our third recommendation, VA stated that VHA worked with its chat platform provider to develop a solution to address chats being abandoned after customer redirection to an unavailable responder. VA also provided GAO with documentation to demonstrate how the updated process is designed to resolve this issue. To the extent the updated process addresses abandoned chats, this action should meet the intent of our recommendation.

Regarding our fourth recommendation, VA stated that VHA will convene a workgroup of subject matter experts to discuss disclosure policies for non-clinical VA services. VA provided a target completion date of January 2026 for this recommendation.

As agreed with your office, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at hundrupa@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Alyssa M. Hundrup

Director, Health Care

This report (1) describes data on Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) calls, texts, and chats for fiscal years 2021 through 2024; (2) examines VCL procedures for operating the crisis line; and (3) examines the VCL’ s monitoring of crisis responders’ call, text, and chat interactions. To address these objectives, we analyzed VCL call, chat, and text data; reviewed VCL documentation and data related to handling customer interactions, staffing and training crisis responders, and monitoring; interviewed VCL officials; and surveyed and interviewed VCL responders.

Analysis of VCL call, text, and chat data. We obtained national data on calls, texts, and chats for fiscal years 2021 through 2024 from the VCL. The VCL uses different systems for each medium, and thus, we obtained data from each system separately. Our analysis focused on VCL calls, texts, and chats that the system offered to a crisis responder.[61]

For calls, we analyzed call volume, call wait time—the time a caller spent waiting for a responder to become available plus the time the call spent ringing after being routed to a responder—and rates of answered and abandoned calls (i.e., when callers hang up before a responder answers). We examined these variables for calls waiting for the main phone line and calls waiting for the “customers with complex needs” (CWCN) unit, which handles difficult and repeat callers. Finally, we examined these variables for calls that were redirected within the VCL, that is calls intended for the CWCN that were ultimately redirected to the main phone line or vice versa.[62] In addition to calls to the VCL, we also examined volume, wait times, and abandonment rates for abusive customer transfers, which, until December 2024, occurred when a main phone line responder transferred a caller to the CWCN unit.[63]

For texts and chats within the digital services unit, we analyzed volume as well as text and chat response times, which, according to the VCL, is defined as the time it takes for a customer’s text or chat to be accepted by the system and for a responder to write and send an initial response. We also analyzed rates of answered and abandoned (defined as when an interaction ends before a responder sends a response, according to officials) texts and chats. We examined these variables by whether a responder was handling a text or chat concurrently, that is at the same time as at least one other text or chat, or not concurrently. We also analyzed the total number of concurrent chats and texts handled by individual responders at one time.

To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed related documentation, interviewed VCL officials and performed electronic testing to identify any missing data and obvious errors. On the basis of these steps, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.[64] However, because the VCL changed the system it uses to handle chats in August 2024 and, because of issues with reliability and comparability with the prior system, we did not include chat data from August and September 2024 in our analysis.

Review of VCL procedures for operating the crisis line. We reviewed Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and VCL documentation, such as on procedures for handling customer interactions as well as for staffing and training crisis responders, and interviewed VCL officials about them.[65] We also analyzed available VCL data related to crisis responder staffing and workload, including data on responder turnover and vacancy rates from fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2024, the number of responders scheduled for a shift, how many responders actually worked on the shift from January 2024 to April 2024, and the number of chats individual digital services responders handled during a shift from April 2024 through September 2024.[66]

In addition, we analyzed data from the VCL’s CWCN database from October 1, 2022, through May 9, 2024, to determine whether the VCL was reviewing CWCN interventions in accordance with VCL policy.[67] Specifically, we counted the number of instances where reviews for unique interventions exceeded the number of days dictated by policy. To assess the reliability of each data source, we reviewed related documentation and interviewed VCL officials on procedures VCL uses to collect and store the data. Based on these steps, we determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives. Finally, we evaluated VCL’s procedures for operating the crisis line against federal internal control standards, such as those related to identifying and responding to risks, and the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA) directive on VCL operations.[68]

Review of VCL monitoring of crisis responders’ calls, text, and chat interactions. We reviewed the data that the VCL uses to monitor incoming customer interactions, VCL’s quality assurance process, and the VCL’s monitoring of safety and other types of incidents reported to the crisis line. Specifically, we examined relevant VHA and VCL documentation, such as policies related to establishing data metrics and related goals, the standards the VCL has set for responders’ interactions with customers, and procedures for responding to incidents.[69] We also interviewed VCL officials on these topics. Additionally, we

· analyzed monthly VCL data on the results of VCL quality assurance reviews from fiscal year 2023 through fiscal year 2024 to determine the percent of ‘not successful’ ratings each month for each interaction standard.[70] We compared the results of this analysis against documents the VCL developed to address standards with high percentages of not successful ratings. To assess the reliability of the quality assurance data, we reviewed related documentation and interviewed VCL officials on procedures the VCL uses to collect and store the data. Based on these steps, we determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

· reviewed two lists maintained by the VCL containing data from October 2022 through March 2024 to understand how the VCL reviewed and documented different categories of incidents. The first was a list of 143 critical incidents divided into four categories: complaints (15 entries), deaths by suicide (8 entries), privacy and release of information (4 entries), and safety events/near misses (116 entries).[71] The second was a list of 316 suicides reported to the VCL, some of which were also categorized as critical incidents and therefore were also included on the first list.

From these lists, we selected 17 critical incidents, eight of which were suicides, as well as an additional 15 suicides that were not categorized as critical incidents and reviewed associated documentation.[72] While not generalizable, our selections of critical incidents and suicides to review provide illustrative examples of how the VCL responded after receiving a report of a potential incident involving the crisis responder’s interaction with a customer.

Finally, we compared the results of our examination of VCL’s monitoring of incidents against the goals stated in VA’s strategic plan.[73]

Survey of and interviews with VCL crisis responders. To gain an understanding of VCL responders’ experience working for the VCL, we sent a survey with both closed-ended and open-ended questions to VCL crisis responders on topics including VCL procedures, workload and work environment, and training.[74] To identify the population of crisis responders, we obtained a list of responders who completed initial training and were able to answer phone calls independently as of May 2024 from the VCL and removed those who were on detail away from the crisis line or who opted to not participate in our survey during initial outreach. This resulted in the survey being sent 946 VCL crisis responders.

We sent the survey to responders in May 2024 and left it open to responses for approximately 2 months. We pre-tested the survey with three responders who had various experiences at the VCL, including ranges in amount of time they were employed by the VCL, assigned shift, and additional duties with the CWCN or digital services units, incorporating their feedback as appropriate. We received 484 completed surveys for a response rate of 51 percent, meaning our results could be subject nonresponse bias. We did not analyze differences between the populations who did and did not respond, and therefore, crisis responders’ answers cannot be generalized to the full population of responders at the VCL. For a list of survey questions and associated results, see appendix II.

To obtain more in-depth information on topics covered in our survey, we conducted semi-structed interviews with a non-generalizable sample of eight crisis responders.[75] Before selecting, we accounted for additional duties, such as serving as a CWCN or digital services responder, as well as a responders’ assigned shifts to ensure we heard about a wide range of experiences with the VCL.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

This appendix provides information on a survey we administered to Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) responders to gain an understanding of responders’ experience working for the VCL. Specifically, we sent a survey with both closed-ended and open-ended questions to 946 VCL crisis responders (the total number of responders who completed initial training and were able to answer phone calls independently as of May 2024 after removing those who were on detail away from the crisis line or who opted to not participate in our survey during initial outreach).

We received 484 completed surveys for a response rate of 51 percent, meaning our results could be subject nonresponse bias. We did not analyze differences between the populations who did and did not respond, and therefore, crisis responders’ answers cannot be generalized to the full population of responders at the VCL.

To better understand responders’ experiences with specific units of the VCL (the main phone line, the “customers with complex needs” (CWCN) unit, which handles difficult and repeat callers, and the digital services unit, which provides chat and text based support), we programmed our survey so responders who indicated that they served as a CWCN or digital services responder would be presented with questions specific to that duty. The specific duties of responders are noted in the survey responses presented. Questions with no duty noted were presented to all respondents (for example, any questions that refer to the VCL phone line generally).

The first four questions confirmed that respondents were currently crisis responders with the VCL, as well as asked about respondents’ additional duties, length of time employed by the VCL, and current shift assignment. Ninety-nine percent (479) of respondents confirmed that they currently worked as a crisis responder with the VCL at the time of our survey. Of those working as crisis responders with the main phone line,

· 16 percent indicated that they also worked as a CWCN responder,

· 37 percent indicated that they also worked as a digital services responder,

· 33 percent indicated that they also helped train other staff, and

· 45 percent indicated that they did not hold other duties besides main phone line responder.[76]

Regarding length of employment,

· 39 percent indicated that they have worked as a responder with the VCL for less than 2 years,

· 37 percent for 2 to 5 years, and

· 24 percent for more than 5 years.

Regarding shift,

· 33 percent indicated that they are assigned to the night shift,

· 29 percent the evening shift,

· 28 percent the morning shift, and

· 10 percent the midday shift.

Below we present summary information on response rate by responder duty as well as the 484 responders’ responses to categorical questions about training, workload and work environment, and procedures.[77]

|

VCL duty |

Responded to survey |

Did not respond to survey |

|

Main phone line |

484 (51.2%) |

462 (48.8%) |

|

Customers with complex needs |

64 (53.8%) |

55 (46.2%) |

|

Chat |

161 (49.5%) |

164 (50.5%) |

|

Text |

168 (48.1%) |

181 (51.9%) |

Source: GAO survey of crisis responders. | GAO‑25‑107182

Notes: Percentages in rows may not add up to 100 due to rounding. Responders can work multiple duties in addition to working as a responder for the main phone line. As a result, duty categories are not mutually exclusive and column percentages do not add to 100.

|

Question |

Response (extent to which responder agreed with the statement) |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Training before taking calls as a Veterans Crisis Line (VCL) phone responder provided knowledge and skills to perform duties. |

Missinga |

1 |

0.21 |

|

Strongly disagree |

25 |

5.22 |

|

|

Somewhat disagree |

54 |

11.27 |

|

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

32 |

6.68 |

|

|

Somewhat agree |

200 |

41.75 |

|

|

Strongly agree |

167 |

34.86 |

|

|