DEFENSE HEALTH CARE

DOD Should Improve Monitoring of TRICARE Beneficiaries’ Access to Prescription Drugs

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107187. For more information, contact Sharon Silas at (202) 512-7114 or SilasS@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107187, a report to congressional committees

DOD Should Improve Monitoring of TRICARE Beneficiaries’ Access to Prescription Drugs

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD provides health care benefits, including a pharmacy benefit, to over 9 million beneficiaries through TRICARE. Eligible beneficiaries include active duty service members, retirees, and their dependents. DOD’s DHA administers the TRICARE pharmacy program through a contract. In January 2023, pharmacy services started under a new contract. Some stakeholders expressed concern that changes to the program could affect beneficiaries’ access to prescription drugs.

The Senate report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review significant changes to the TRICARE pharmacy program. This report describes key changes DHA made to the program that could affect beneficiaries’ timely access to prescription drugs between January 1, 2021, and June 30, 2024. It also describes how key changes affected beneficiaries’ access and examines how DHA monitors beneficiary access to prescription drugs.

GAO reviewed TRICARE pharmacy contracts, DHA documents, and analyzed contractor data. GAO also interviewed DHA officials, contractor representatives, and beneficiary and pharmacy stakeholder groups.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to DHA to improve its monitoring of the pharmacy contractor, including auditing contractor-reported data for accuracy. DOD partially concurred with one recommendation and concurred with the other. GAO continues to believe the recommendations are warranted, as discussed in this report.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) TRICARE pharmacy program allows beneficiaries to obtain prescription drugs from DOD-operated military pharmacies, retail pharmacies, and via mail order.

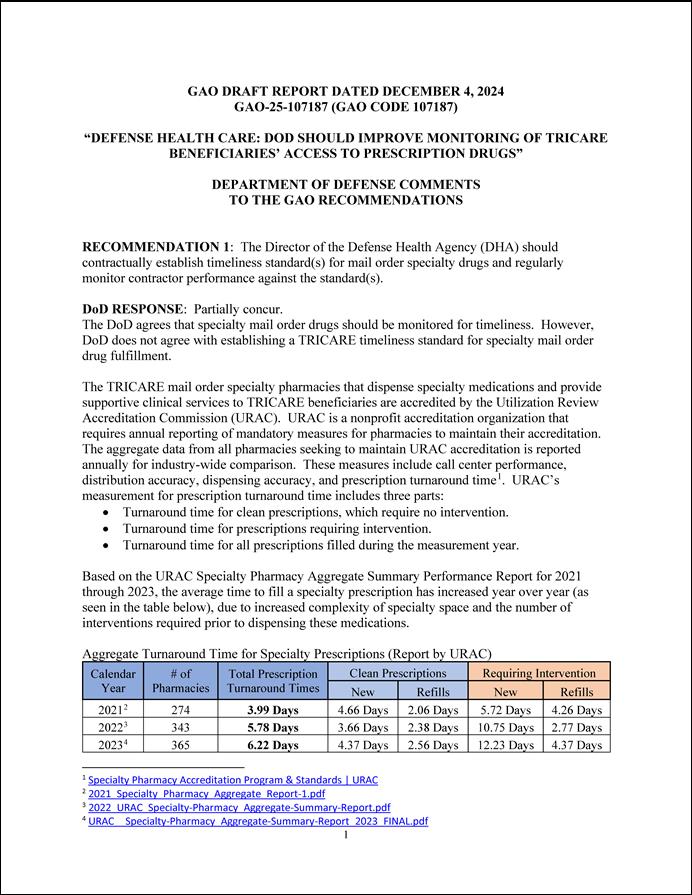

DOD’s Defense Health Agency (DHA) made certain key changes to the program between January 1, 2021, and June 30, 2024, that could affect beneficiaries’ timely access to prescription drugs. One of these key changes was lowering the required minimum number of pharmacies in the retail network from 50,000 to 35,000, resulting in a drop in the number of retail pharmacies accepting TRICARE. DHA officials told GAO that a smaller network could result in government savings. Contractor data indicate that in the third quarter of 2024, there were an average of 42,550 pharmacies in the network, 13,165 fewer than in the third quarter of 2022, the quarter before the TRICARE contractor implemented the retail network change.

Note: In the fourth quarter of 2022, the Defense Health Agency waived retail network size requirements while the TRICARE contractor implemented a network change.

As of the second quarter of 2024, contractor data indicate that 98 percent of beneficiaries were within a 15-minute drive of a network pharmacy, which met a DHA requirement for beneficiary proximity to retail pharmacies. However, GAO’s analysis of contractor data indicate that the decrease in the number of retail pharmacies likely affected some beneficiaries. For example, about 380,000 beneficiaries, about 4 percent, may have had to find a new pharmacy when a pharmacy they previously used left the network. DHA officials told GAO they viewed this as a reduction in choice of preferred pharmacy, not a loss of access.

DHA officials told GAO they primarily monitor beneficiary access by reviewing contractor-provided monthly reports. Although DHA’s oversight plans for the pharmacy contract call for the agency to audit the accuracy of data included in these reports, DHA officials said they had not done so. GAO found inaccuracies in some reports, including reports on use of specialty drugs. Periodically auditing contractor data will provide DHA with the information it needs to better ensure TRICARE beneficiaries’ continued access to prescription drugs.

Abbreviations

DHA Defense Health Agency

DOD Department of Defense

TPharm4 TRICARE Pharmacy Services, Fourth Generation

TPharm5 TRICARE Pharmacy Services, Fifth Generation

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 13, 2025

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Department of Defense (DOD) offers a full range of medical care and services, including a pharmacy benefit, to over 9 million eligible beneficiaries, including active duty service members, retirees, and their eligible family members. DOD’s Defense Health Agency (DHA) oversees the TRICARE pharmacy program, which allows beneficiaries to obtain prescription drugs from DOD-operated military treatment facility pharmacies, at retail pharmacies, or through a mail order program. TRICARE covers a range of prescription drugs from traditional medications to high-cost prescription medications known as specialty drugs, which include injectable and infused medications that are more difficult to distribute and administer. In fiscal year 2023, TRICARE spent over $8 billion on prescription drugs for about 6.6 million (70 percent) of its beneficiaries.

Like many private health plans in the U.S., DHA contracts with a pharmacy benefit manager to administer TRICARE’s pharmacy program. This contractor has a range of responsibilities, including developing and maintaining a network of retail pharmacies and operating a mail order pharmacy. In August 2021, DHA awarded its most recent pharmacy contract for $4.28 billion for services beginning January 1, 2023. The cost of the TRICARE pharmacy program contract does not include the cost of drugs. The current contractor has administered the TRICARE pharmacy program since 2003.

In awarding this contract, DHA reported that it had made changes to the TRICARE pharmacy program with the goal of improving service for beneficiaries and saving money for military families and taxpayers by creating a more efficient, competitively priced pharmacy network. In doing so, TRICARE, like many private health plans in the U.S., has signaled its interest in better managing trends including the increasing cost of prescription drugs and retail pharmacy closures.[1] Military service organizations and other stakeholders have expressed concerns that any changes to the pharmacy program could affect beneficiaries’ access by limiting their ability to obtain prescription drugs in a timely manner. Factors such as physical proximity to a pharmacy, coverage, and cost can affect one’s access to prescription drugs.

The Senate Armed Services Committee Report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review any significant changes DOD has made to the benefits or coverage for the TRICARE pharmacy benefits program over the last 3 years (since 2021).[2] In this report we:

1. describe key changes DHA made to the TRICARE pharmacy program that could affect beneficiaries’ timely access to prescription drugs,

2. examine how DHA monitors beneficiary access to the TRICARE pharmacy program, and

3. describe how key changes to the TRICARE pharmacy program may have affected beneficiary access to prescription drugs.

To describe key changes DHA made to the TRICARE pharmacy program, we reviewed pharmacy program policies, handbooks, manuals, evaluations, and contracts in effect from January 1, 2021, to June 30, 2024, to identify any changes to the program or contract. These included the TRICARE Pharmacy Services, Fourth Generation (TPharm4) contract, which ended pharmacy services in December 2022 and the TRICARE Pharmacy Services, Fifth Generation (TPharm5) contract, which started pharmacy services beginning in January 2023. We also analyzed data provided by DHA’s contractor, such as data on network size, beneficiary access, and use of prescription drugs (e.g., number of specialty drugs dispensed from different types of pharmacies) from January 1, 2021, to June 30, 2024.[3] We examined these data to identify any shifts or spikes in beneficiary access that could have indicated key changes implemented during this period. To gather stakeholder perspectives on key changes, we interviewed representatives from a nongeneralizable selection of 11 stakeholder groups, representing a variety of beneficiary and pharmacy perspectives.[4] We selected these groups to obtain a range of perspectives, including beneficiaries with rare or complex conditions and representatives from chain and independent pharmacies.

We defined key changes as changes DHA made to the TRICARE program and contract between January 1, 2021, to June 30, 2024, that could directly affect TRICARE beneficiaries’ ability to obtain prescription drugs in a timely manner within the U.S. To describe the reasons for the key changes we identified, we interviewed DHA officials and contractor representatives. We confirmed our identification of key changes and the reasons for the changes with DHA. Our review also identified other changes to the TRICARE pharmacy program during this time that did not meet our definition of a key change.[5] Appendix I summarizes selected other changes.

To examine how DHA has monitored beneficiary access to the TRICARE pharmacy program, we focused on monitoring of beneficiary access with respect to the key changes we identified. To do so, we reviewed relevant laws and regulations, TPharm4 and TPharm5 contracts and other procurement related materials, and DHA policies to identify retail pharmacy network and specialty drug access requirements and monitoring responsibilities.[6] We analyzed data DHA uses to monitor access, including monthly reports on two contractually defined access standards the TRICARE pharmacy contractor is required to meet on 1) the size of the retail pharmacy network and 2) beneficiaries’ proximity to the nearest network retail pharmacy. We also reviewed pharmacy industry standards related to monitoring beneficiary access to specialty drugs.[7] We interviewed DHA officials about monitoring processes, procedures, and the actions they have taken to monitor beneficiary access to the retail pharmacy network and specialty drugs. We assessed DHA’s monitoring processes against its Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan for the TPharm5 contract, federal internal control standards related to monitoring activities, and DHA pharmacy program policy.[8]

To describe the effects of the key changes on beneficiaries, we reviewed contractor data on beneficiary access from January 1, 2021, to June 30, 2024. To obtain illustrative examples of the effects of key changes on beneficiaries, we interviewed representatives from the 11 stakeholder groups previously discussed.

For each objective, we assessed the reliability of data by reviewing related documentation, interviewing knowledgeable DHA officials and contractor representatives, and performing electronic testing to identify any missing data or obvious errors. Based on these steps, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

TRICARE Pharmacy Program

The mission of the TRICARE pharmacy program is to provide beneficiaries with the prescription drugs they need when they need them in a safe, easy, and affordable way. To accomplish this, DHA contracts with a pharmacy benefit manager to implement the benefit design, which is determined by the agency. This contractor is responsible for, among other things, maintaining a retail pharmacy network, which involves negotiating reimbursement terms with retail pharmacies for drugs dispensed to TRICARE beneficiaries. The contractor is also to operate a mail order pharmacy; process payments to retail pharmacies for filling prescriptions for TRICARE beneficiaries; and report a range of data to DHA, including claims, use, and access data.

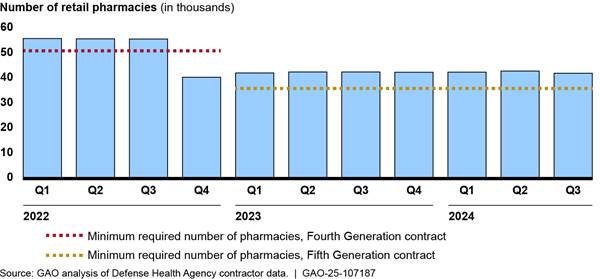

Beneficiaries can obtain covered prescription drugs through military, retail (network or out-of-network), and TRICARE mail order pharmacies. Beneficiaries may be responsible for paying a portion of the costs of their prescription drugs to pharmacies in the form of copayments.[9] See figure 1 for an explanation of the roles and responsibilities of certain entities involved in TRICARE’s pharmacy program.

Figure 1: Selected Roles and Responsibilities of Certain Entities Involved in Providing TRICARE Beneficiaries Access to Prescription Drugs

aBy law, the national prime vendor can obtain prescription drugs at prices that are generally 24 percent lower than nonfederal average manufacturer prices for non-generic products. See 38 U.S.C. 8126(a)(2).

bTRICARE’s pharmacy contractor maintains a retail network by contracting with pharmacies directly or through pharmacy services administrative organizations, which represent independent pharmacies.

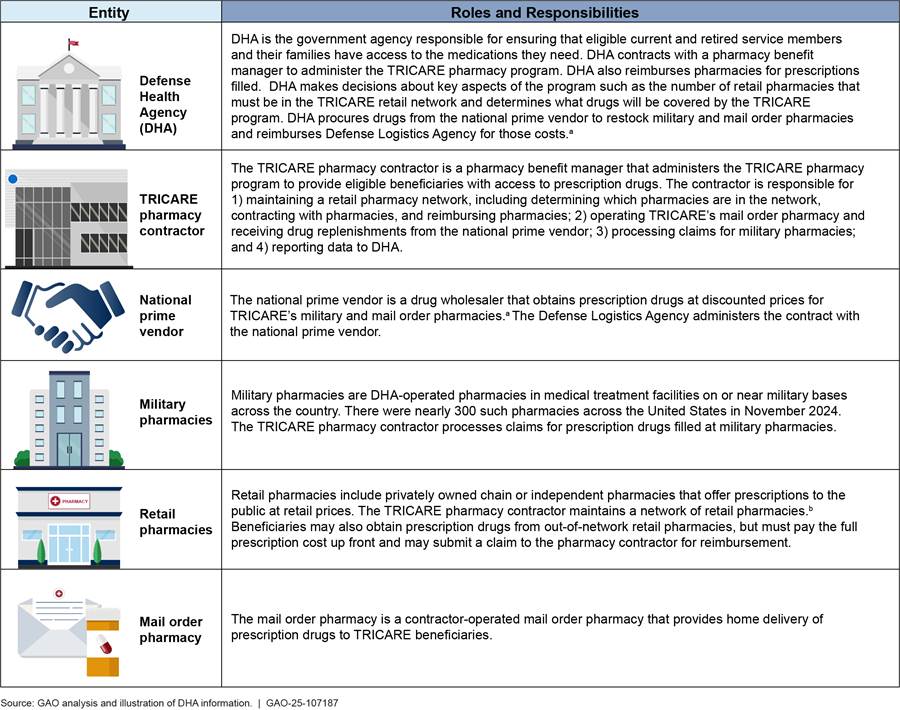

DHA coordinates with entities to procure prescription drugs and make them available to beneficiaries through military, retail, and mail order pharmacies. See figure 2 for a diagram of the relationship between certain entities involved in the TRICARE pharmacy program.

Figure 2: Relationships between Certain Entities Involved in Providing TRICARE Beneficiaries Access to Prescription Drugs

aTo resupply prescription drugs dispensed from military and mail order pharmacies; DHA reimburses the Defense Logistics Agency for the cost of drugs purchased through an intermediary known as a national prime vendor. The national prime vendor provides drugs at a fixed percentage discount off the lowest price otherwise available for each drug. By law, these prices are generally 24 percent lower than nonfederal average manufacturer prices for non-generic products. See 38 U.S.C. 8126(a)(2).

bDHA’s pharmacy contractor acts as a fiscal intermediary. DHA makes government funds available to its pharmacy contractor to make direct payments to retail pharmacies.

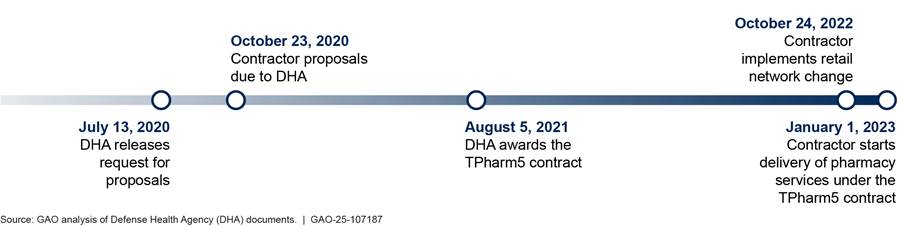

TRICARE Pharmacy Contracting and Monitoring

Key steps in DHA’s TRICARE pharmacy contracting process include strategy development, acquisition planning, proposal solicitations, negotiation, and contract awarding. Delivery of pharmacy services for DHA’s TPharm4 contract was in effect from May 1, 2015, to December 31, 2022. In preparation for the next contract period, DHA released a request for proposals for the TPharm5 contract in July 2020. DHA awarded the TPharm5 contract in August 2021. With DHA’s permission, the contractor implemented a TPharm5 retail pharmacy network change in October 2022 and began delivery of services on January 1, 2023.[10] DHA has an option to extend TPharm5 services through December 31, 2029. (See figure 3.)

Figure 3: TRICARE Pharmacy Services, Fifth Generation (TPharm5) Contract Development and Implementation Timeline

DHA is responsible for managing the pharmacy program and monitoring contractor performance, including reviewing contractor data to ensure they are meeting standards. The TRICARE pharmacy contract includes contractor responsibilities, reporting requirements, and performance standards. Performance standards are requirements that the contractor must meet to avoid a financial penalty or must exceed to earn a financial incentive. For example, DHA monitors its contactor’s ability to meet two performance standards related to beneficiary access: 1) the size of the retail pharmacy network and 2) beneficiaries’ proximity to the nearest network pharmacy.[11]

DHA Lowered the Required Minimum Number of Retail Pharmacies and Added a Requirement for Obtaining Certain Specialty Drugs

We found that DHA made two key changes to the TRICARE pharmacy program between January 1, 2021, and June 30, 2024. They are 1) lowering the required minimum number of pharmacies in the retail network and 2) adding a specialty pharmacy and a requirement related to how beneficiaries access certain specialty drugs.[12]

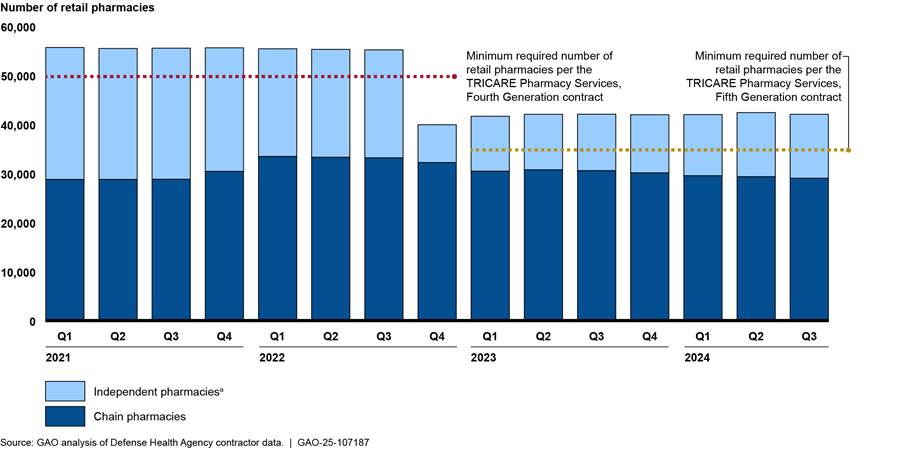

DHA Lowered the Required Minimum Number of Pharmacies in the Retail Network

Under the TPharm5 contract, DHA lowered the required minimum number of retail pharmacies in the TRICARE network by 15,000, which equates to 25 percent of the required minimum number of pharmacies in the TPharm4 contract. Specifically, DHA had required the contractor to ensure that there was a minimum of 50,000 retail pharmacies in the TRICARE network through 2022.[13] DHA lowered this requirement to a minimum of 35,000 pharmacies in the TPharm5 contract, with delivery of pharmacy services beginning in January 2023. DHA officials said that a smaller network would enhance the contractor’s ability to negotiate lower reimbursement rates with retail pharmacies, which could result in government savings, a goal of the TPharm5 contract.[14]

As a result of the lower minimum number of pharmacies in the network, the number of retail pharmacies in the TRICARE network declined, but still remained above the minimum of 35,000 pharmacies the TPharm5 contract required. The largest reduction in the number of retail pharmacies in the TRICARE pharmacy network occurred between September and October 2022, when the network decreased from 55,762 pharmacies to 41,108 pharmacies (a 26 percent reduction), according to our analysis of contractor data. Four pharmacy stakeholder groups we interviewed said some pharmacies decided to leave the network because of unfavorable reimbursement terms proposed to them by the pharmacy contractor.[15] Contractor representatives told us that, in December 2022 and again in November 2023, they asked pharmacies that had recently left TRICARE to reconsider their decision. As of October 2024, the TRICARE network included 42,457 pharmacies, according to contractor data. (See figure 4.)

Figure 4: Average Number of Independent and Chain Retail Pharmacies in the TRICARE Network by Quarter, January 2021 to September 2024

Notes: In July 2022 (Q3), the Defense Health Agency (DHA) granted the TRICARE pharmacy contractor a waiver to the requirement of maintaining a minimum of 50,000 pharmacies in the retail network while it was implementing the TPharm5 network change.

This figure does not include the number of pharmacies operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs and Indian Health Service, which ranged between 510 to 542 across this time. DHA does not count these pharmacies toward the minimum number of network retail pharmacies that its contractor must maintain.

aIndependent pharmacies include those represented by pharmacy services administrative organizations. According to DHA, these organizations include Arete Pharmacy Network/AlignRx, Cardinal Health/ Medicap Pharmacy/Medicine Shoppe, EPIC, and Health-Mart Atlas/Strategic Health Alliance.

Nearly all the pharmacies that left the TRICARE network in October 2022 were independent pharmacies.[16] Our analysis of contractor data indicates that, between September and October 2022, the number of independent pharmacies in the TRICARE pharmacy network dropped from 22,055 to 7,575, a loss of 14,480 pharmacies. Since then, some independent pharmacies rejoined the TRICARE network. As of October 2024, there were 13,191 independent pharmacies in the TRICARE network, about 40 percent fewer than the 22,055 independent pharmacies that were in the network in September 2022, according to our analysis of contractor data. In contrast, from January 2021 through October 2024, the number of chain pharmacies ranged from about 28,800 to 33,500.

DHA Introduced a Specialty Pharmacy and Requirement for Beneficiaries Obtaining Certain Specialty Drugs

In January 2023, DHA introduced a specialty pharmacy to the TRICARE network to enhance beneficiaries’ access to specialty drugs.[17] DHA officials told us they believed that introducing a specialty pharmacy would support the growing needs of its beneficiaries for specialty drugs.[18] In addition, DHA officials told us that the specialty pharmacy would offer beneficiaries enhanced access to personalized clinical services, such as 24-hour access to clinical care teams, which can include specialty-trained pharmacists and nurses.

DHA also increased beneficiaries’ access to specialty drugs by allowing them to obtain specialty drugs at any network retail pharmacy. Prior to January 1, 2023, TRICARE beneficiaries could obtain specialty drugs from military pharmacies, the contractor-operated mail order pharmacy, or select retail pharmacies. However, DHA officials told us that not all traditional pharmacies stock or can readily obtain certain specialty drugs, which can limit a beneficiary’s ability to access them when needed.

|

DHA’s Coverage of Specialty Drugs The TRICARE pharmacy program provides beneficiaries with access to certain specialty drugs–such as high-cost medications—used to treat chronic conditions that can be more difficult to distribute and administer. DHA maintains a list of covered specialty drugs and updates that list to reflect programmatic and market changes. Coinciding with the start of pharmacy services under the TRICARE Pharmacy Services, Fifth Generation contract in January 2023, DHA increased the number of drugs on its specialty drug list by nearly 400 percent, from 246 drugs to 980 drugs. According to DHA officials, 661 of the added drugs were already covered by the TRICARE pharmacy benefit. DHA officials said that they reclassified these drugs as specialty to increase the number of drugs that can be replenished from the national prime vendor at discounted prices. As of September 2024, DHA’s specialty drug list contained 1,172 drugs. Source: GAO analysis of Defense Health Agency (DHA) interviews and documents. | GAO-25-107187 |

On March 1, 2024, DHA began requiring TRICARE beneficiaries, with some exceptions, to use the mail order specialty pharmacy or a military pharmacy to fill their prescriptions for certain specialty maintenance drugs—those taken for chronic or ongoing conditions.[19] In alignment with TPharm5 contract goals, DHA officials said they believed that requiring beneficiaries to use the mail order specialty pharmacy would help save money for military families. Specifically, with this change, more TRICARE beneficiaries could obtain their specialty drugs at the mail order copayment rate, which is 70 percent less than the retail copayment rate for a 90-day supply of drugs. For example, TRICARE beneficiaries would be required to pay $38 for a 90-day prescription from the specialty pharmacy, compared with $129 for the same amount of medication from a retail pharmacy. (See table 1.)

Table 1: Potential Beneficiary Copayments for Certain Brand Name Maintenance Specialty Drugs through TRICARE Pharmacies in March 2024

|

Pharmacy |

Days’ supply per fill |

Copayment |

Total beneficiary copayment per 90-day supply |

|

Network retail |

Up to 30 days |

$43 |

$129 |

|

Mail order, including specialty |

Up to 90 days |

$38 |

$38 |

|

Military |

Up to 90 days |

$0 |

$0 |

Source: GAO analysis of Defense Health Agency documents. | GAO‑25‑107187

Note: This table lists copayment amounts for covered brand name drugs. Active duty service members pay nothing for covered prescriptions from military pharmacies, mail order, or retail network pharmacies. TRICARE pharmacy copayment amounts are set by statute in 10 U.S.C. 1074g(a)(6)(A).

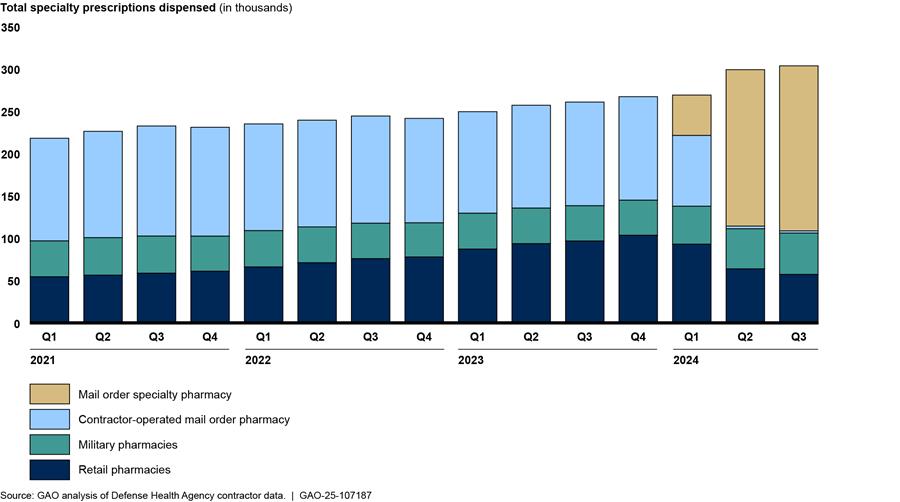

DHA officials told us that requiring beneficiaries to use the specialty pharmacy for certain maintenance drugs could also provide significant cost avoidance and help save U.S. taxpayer money, another goal of the TPharm5 contract. Coinciding with the requirement to use the mail order specialty pharmacy, DHA officials reported they began using the national prime vendor to replenish the stock of government-contracted specialty drugs the specialty pharmacy dispensed via mail.[20] Through the national prime vendor, DHA can acquire drugs at prices substantially lower than what retail pharmacies pay.[21] As a result, any increase in the portion of specialty drugs dispensed by military pharmacies or the specialty pharmacy could result in savings to the program. Our analysis of contractor data indicates an immediate increase in the share of specialty drugs dispensed by the specialty pharmacy from April to June 2024, along with a decrease in the share dispensed by retail pharmacies, when compared with the last quarter of 2023. (See figure 5.)

Figure 5: Number of 30-day Specialty Drug Prescriptions Dispensed by TRICARE Pharmacy Type by Quarter, January 2021 through September 2024

Notes: In January 2023, the Defense Health Agency (DHA) introduced a new mail order specialty pharmacy to the TRICARE program. Specialty drug prescriptions dispensed by the specialty pharmacy from January 2023 through February 2024 are counted and displayed as retail pharmacy prescriptions. In March 2024, DHA began requiring beneficiaries to fill certain specialty drug prescriptions through the specialty pharmacy and began tracking these prescriptions separately from other types of pharmacies. Specialty drug prescriptions previously filled by the contractor-operated mail order pharmacy were administratively transferred to the specialty pharmacy in March 2024.

Prescriptions are shown as 30-day equivalent prescriptions. Dispensations for more than 30-days’ worth of a drug are considered multiple prescriptions. DHA officials told GAO that in January 2023, they reclassified several hundred previously covered drugs as specialty drugs for the purpose of benefit management. Specialty prescription data from 2021 and 2022 presented here include those drugs that were later reclassified as specialty drugs.

DHA Primarily Relies on Contractor Data to Monitor Certain Aspects of Beneficiary Access but Has Not Verified the Accuracy of These Data

DHA primarily relies on contractor data to monitor beneficiary access to the TRICARE pharmacy benefit. These data indicate that the contractor is meeting certain standards related to beneficiary access. However, we identified some weaknesses in DHA’s monitoring efforts. In particular, we found that DHA 1) has not monitored the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs to beneficiaries and 2) has not verified the accuracy of the contractor data it relies on to monitor beneficiary access.

DHA Primarily Relies on Contractor Data to Monitor Certain Aspects of Beneficiary Access to Pharmacy Services

DHA officials told us that they primarily rely on contractor-provided data to monitor certain aspects of beneficiary access to the TRICARE pharmacy program. Specifically, to monitor beneficiary access to the retail network, DHA officials told us they review monthly reports from the contractor on the extent to which it is meeting two standards related to 1) the size of the retail pharmacy network and 2) beneficiary proximity to a network pharmacy.

1. Size of the retail pharmacy network. Since January 2023, DHA has required its contractor to maintain a minimum of 35,000 retail pharmacies in the network.

2. Beneficiary proximity to a network pharmacy. Since January 2023, one of DHA’s proximity standards has required its contractor to ensure that at least a certain percentage of beneficiaries have at least one network pharmacy within a 15-minute drive of their home.[22]

Our review of these data indicates that the contractor has met DHA’s network size requirement and certain proximity access standards as defined in the TPharm4 and TPharm5 contracts from January 2021 through June 2024. For example, in June 2024, contractor data indicate that there were 42,884 pharmacies in the retail network. Similarly, in June 2024, 98 percent of beneficiaries were within a 15-minute drive of at least one network pharmacy, according to contractor data. DHA officials also told us they monitor beneficiary access by reviewing beneficiary surveys, call center reports, and data on the timely delivery of mail order traditional drugs.[23]

To monitor beneficiary access to specialty drugs, DHA officials told us they review contractor data on beneficiary use of specialty drugs, including how many prescriptions are filled at each type of pharmacy.[24] The officials told us they review these data for outliers and significant changes from one reporting period to the next.

DHA Has Not Monitored the Contractor’s Timeliness in Dispensing Mail Order Specialty Drugs to Beneficiaries

According to DHA officials, the agency does not monitor beneficiaries’ timely access to specialty drugs. While DHA monitors beneficiary use of specialty drugs, including the number and type of specialty drugs dispensed, agency officials told us that they do not monitor the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs, including those dispensed through its specialty pharmacy. Monitoring the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs could include reviewing data on how quickly the contractor has shipped, scheduled delivery, or denied prescriptions. DHA officials told us that the agency has not monitored the timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs because they cannot measure this information.

However, as previously mentioned, DHA monitors the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing traditional drugs through its mail order pharmacy. In addition, the pharmacy industry monitors turnaround time for mail order specialty drugs. For example, the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission, an accreditation organization for specialty pharmacies, monitors how long it takes pharmacies to dispense mail order specialty drugs. Specialty pharmacies accredited through the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission, including DHA’s specialty pharmacy, are required to report on the average number of days the organization takes to fill new mail order specialty prescriptions and refill mail order specialty prescriptions to maintain accreditation.

According to its policy, DHA should develop appropriate metrics to monitor pharmacy activities.[25] Instead of monitoring turnaround time of mail order specialty drugs directly, DHA officials told us that they rely on the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission’s certification of the specialty pharmacy to ensure the timely delivery of mail order specialty drugs. The commission requires specialty pharmacies to provide it with timeliness data, among other things, in order to secure accreditation. However, these data are not specific to the TRICARE program. It averages the specialty pharmacy’s timeliness across all lines of business and could obscure timeliness issues within the TRICARE program. Thus, it is not sufficient for monitoring the TRICARE program.

Monitoring the timeliness of the contractor in dispensing mail order specialty drugs, similar to how the agency monitors the timeliness in dispensing mail order traditional drugs, would provide DHA with critical information to assess beneficiaries’ access to these medications. This is especially important given DHA’s recent transition to a specialty pharmacy that beneficiaries are to use to obtain certain specialty drugs. Monitoring the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing these medications could also assist DHA in pinpointing any potential problems that may occur, determine whether a performance standard is needed, and help DHA ensure that the contractor is consistently dispensing these prescriptions in a timely manner.

DHA Has Not Verified the Accuracy of TRICARE Pharmacy Contractor Data

While DHA relies on contractor-provided data to monitor certain aspects of beneficiary access, the agency has not verified the accuracy of these data, and our review revealed some inaccuracies.[26] DHA maintains a Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan that outlines how the agency will oversee contractor performance and deliverables. This plan states that DHA should conduct periodic audits to verify contractor data for adequacy, accuracy, and adverse performance trends to ensure pharmacy program objectives are met. However, DHA officials told us that they had not audited the contractor data the agency uses for monitoring beneficiary access to verify data accuracy because they had no concerns about data accuracy. Nevertheless, we found errors during our review of some contractor data that DHA uses to monitor beneficiary access.

Specifically, we identified errors in contractor-reported data on 1) beneficiaries’ use of specialty drugs and 2) beneficiaries affected by pharmacies leaving the network. First, our review of four quarters of contractor data provided to DHA in 2023 revealed persistent inconsistencies in the total number of specialty drug prescriptions filled and the number of specialty drug prescriptions filled by pharmacy type. For example, in the first quarter of 2023, the contractor reported that just under 40,000 specialty prescriptions were filled through the mail order pharmacy. Corrected data the contractor later provided indicated that the actual number of prescriptions filled through the mail order pharmacy during that time was about 70,000.

Second, DHA’s contractor reports on the number of beneficiaries who used a pharmacy during the 6 months prior to that pharmacy leaving the TRICARE retail network. These reports inform DHA of how and when the contractor notified beneficiaries that their pharmacy was leaving the network.[27] We identified 2 months of missing information on the number of beneficiaries affected by network changes from April 2024 through June 2024. During this time, roughly 200 pharmacies left the network, but DHA was not able to determine whether any beneficiaries were affected due to the missing contractor data. However, DHA officials told us that some beneficiaries were affected. Specifically, about 70 beneficiaries were not properly notified about the departure of their pharmacy from the retail network. When asked, officials told us they were unaware of the errors in these data. After we brought these errors to DHA’s attention, the contractor drafted a corrective action plan to fix these errors and reissued these reports.

Periodically auditing contractor data will provide DHA with the information it needs to better ensure beneficiaries’ continued access to the prescription drugs they need.

Some Beneficiaries May Have Had to Find a New Pharmacy or Travel Farther to a Network Pharmacy

Our analysis of contractor data indicate that the reduction in the number of retail pharmacies in the TRICARE pharmacy network affected beneficiaries in two ways: 1) some beneficiaries may have had to find a new network pharmacy and 2) some beneficiaries had to travel farther to reach their nearest network pharmacy.

In October 2022, as the contractor implemented the network change and reduced the number of pharmacies in the TRICARE pharmacy network, at least 380,000 TRICARE beneficiaries, about 4 percent of eligible beneficiaries at that time, may have had to find a new network pharmacy, according to our analysis of contractor data. These beneficiaries had recently used one of the over 14,000 pharmacies that left the TRICARE network in October 2022.[28] Affected beneficiaries may have had to transfer their prescriptions to another network pharmacy to continue to use the TRICARE benefit.

Representatives from four beneficiary stakeholder groups we spoke with told us that beneficiaries were concerned about losing access to the pharmacies they had previously used. DHA officials told us that they believed the change in size of the retail pharmacy network amounted to a reduction in the choice of one’s preferred pharmacy, not a loss of access. A representative from one beneficiary stakeholder group we spoke with agreed that, for most beneficiaries, the smaller network size was more of an inconvenience than a loss of access. However, this representative noted that beneficiaries with complex medical needs would be adversely affected if this change resulted in a loss of network capability, such as the network’s ability to fill prescriptions for specialty or compound drugs that require a pharmacy to create a new formulation of a medication to fit a patient’s unique circumstances. A representative from another stakeholder group said that families of children with rare or complex conditions reported losing pharmacies that were familiar with the specialized care these children needed and may struggle to rebuild relationships with new pharmacies.

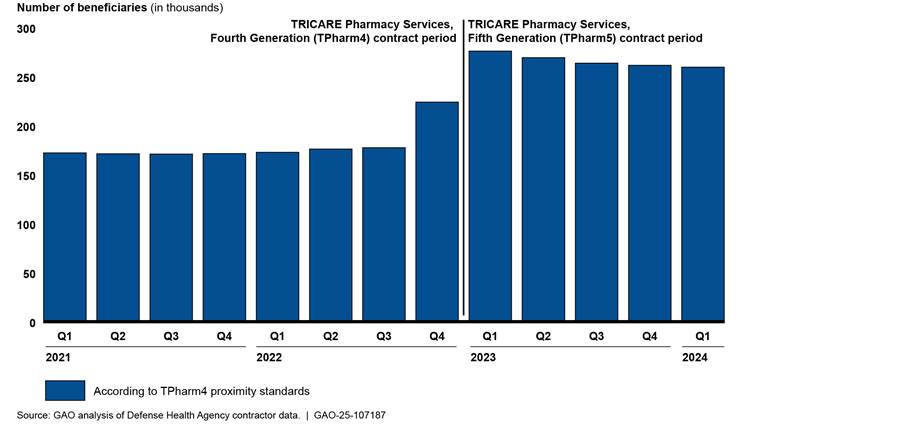

As described elsewhere in this report, DHA monitors how far beneficiaries live from their closest nearby network pharmacy and sets a proximity standard for what it considers “accessible” to beneficiaries. Around the time DHA authorized the reduction in the minimum number of retail network pharmacies, the agency also changed the way it measured beneficiary access to the retail pharmacy network. Specifically, in January 2023, DHA replaced a distance-based proximity standard from the TPharm4 contract with a time-based proximity standard to measure beneficiary access in the TPharm5 contract.[29] DHA officials told us that the time-based standard provides a more accurate measure of how long it takes beneficiaries to reach their nearest retail network pharmacy than the distance-based standard. (See table 2.)

Table 2: Monthly Pharmacy Network Proximity Standards in the TRICARE Pharmacy Services, Fourth (TPharm4) and Fifth (TPharm5) Generation Contracts

|

Distance-based proximity standard TPharm4 contract May 2015 through December 2022 |

Time-based proximity standard TPharm5 contract January 2023 |

|

|

Urban beneficiaries. At least one pharmacy within 2 miles driving distance of [x] percent of beneficiaries |

All beneficiaries. At least one pharmacy within a 15-minute drive of [x] percent of beneficiaries |

|

|

Suburban beneficiaries. At least one pharmacy within 5 miles driving distance of [x] percent of beneficiaries |

All beneficiaries. At least two pharmacies within a [x] minute drive of [x] percent of beneficiaries |

|

|

Rural beneficiaries. At least one pharmacy within 15 miles driving distance of [x] percent of beneficiaries |

All beneficiaries. At least [x] pharmacies within a 30-minute drive of [x] percent of beneficiaries |

|

Source: GAO analysis of Defense Health Agency (DHA) documents. | GAO‑25‑107187

Note: GAO masked proprietary information with [x].

Because DHA changed its proximity standards from distance-based to time-based in January 2023, we could not directly compare proximity access data between the TPharm4 and TPharm5 contract periods. To more clearly illustrate the number of beneficiaries affected by the change in the TRICARE retail pharmacy network, we requested an analysis of contractor data that applied the TPharm4 proximity standard to the TPharm5 population.

Our review of these data indicates that, in the first quarter of 2023, at least 98,000 more beneficiaries (about 1 percent of the total beneficiary population) were outside of the TPharm4 contract’s distance-based standard compared with the period prior to the network changes. These beneficiaries would have had to travel farther to reach their nearest network pharmacy than they had to prior to the October 2022 retail pharmacy network change, according the TPharm4 contract’s distance-based proximity standard. Specifically, in the third quarter of 2022, the quarter before the retail network change, there were about 177,000 beneficiaries outside of the TPharm4 contract’s distance-based standard.

In the first quarter of 2023, the quarter after the retail network change, the number of beneficiaries outside of this standard increased to about 275,000 beneficiaries. According to the TPharm4 proximity standard, the number of beneficiaries without a nearby pharmacy decreased slightly over time, with about 260,000 beneficiaries without a nearby pharmacy in the first quarter of 2024. However, as mentioned earlier in this report, the contractor had met certain proximity access standards for the period of our review, January 2021 through June 2024. (See figure 6.)

Figure 6: Average Number of Beneficiaries Outside of DHA’s Distance-Based Retail Network Proximity Standard by Quarter, January 2021 through March 2024

Note: In the TPharm4 contract, which delivered pharmacy services from May 2015 through December 2022, the Defense Health Agency (DHA) used distance-based driving standards to measure beneficiaries’ access to retail pharmacies. This proximity standard varied based on whether a beneficiary lived in an urban (2 miles), suburban (5 miles) or rural (15 miles) area. At GAO’s request, DHA’s contractor applied the TPharm4 proximity standard to the TPharm5 population to more clearly show the number of beneficiaries affected by the change in the TRICARE retail pharmacy network in October 2022. Despite these changes, the contractor has met certain network proximity standards for the entire time.

Conclusions

While the pharmacy market continues to evolve and drugs costs increase, DHA’s mission to provide beneficiaries access to prescription drugs remains the same. With the TPharm5 contract, DHA made two key changes to the pharmacy benefit with the goal of improving service for beneficiaries and saving money for military families and taxpayers. While DHA monitors certain aspects of beneficiary access to pharmacy services, this monitoring needs to be strengthened. Our review found that DHA is not monitoring the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs, which are crucial for maintaining the health of beneficiaries with chronic conditions. In addition, DHA is not verifying the accuracy of the contractor data it relies on to ensure beneficiary access to pharmacy services, as required by its Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan. By addressing these gaps in its monitoring of beneficiary access, particularly as it relates to key changes implemented, DHA can better ensure that it is meeting the goals of its program and providing beneficiaries access to the prescription drugs they need. Enhanced monitoring could also assist DHA in determining whether any performance standards to ensure beneficiary access are needed and how to establish them.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to DHA:

The Director of the Defense Health Agency should monitor the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of the Defense Health Agency should periodically audit TRICARE pharmacy program contractor-reported data for accuracy, as required by DHA’s Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided DOD with a draft of this report for review and comment. In its written response, which is reprinted in appendix II, DOD partially concurred with our first recommendation and concurred with our second recommendation. The department also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

Regarding our first recommendation, DOD agreed that it was necessary to monitor the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs. To do so, DOD noted that it will develop and implement requirements for the contractor to report turnaround time data and will routinely monitor its performance.

The first recommendation in our draft report also directed DOD to establish a performance standard for the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs. DOD did not concur with this aspect of the recommendation, and in its comments, provided information about challenges related to implementing such a performance standard. For example, DOD commented that it had not determined how to assess the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order specialty drugs because of a variety of factors that make establishing standards difficult, including that many such prescriptions require multiple interventions prior to dispensing medication, and that these prescriptions are often dispensed at irregular intervals.

We acknowledge that the development of such a standard would be difficult given the complexity of specialty drug prescriptions. We therefore clarified our recommendation to focus on monitoring the timeliness of specialty drugs dispensed by mail order. This monitoring would allow DOD to determine whether a performance standard would be appropriate or warranted.

Regarding our second recommendation that DOD periodically audit contractor-reported data for accuracy, DOD concurred, noting that it plans to place additional emphasis on validating contractor-reported data, which will include periodic audits.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of Defense. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7114 or SilasS@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Sharon M. Silas

Director, Health Care

Our review of the TRICARE pharmacy program between January 1, 2021, and June 30, 2024, identified some changes that did not directly affect beneficiaries’ ability to obtain prescription drugs in a timely manner. Examples of selected changes are described below.

Formulary. The Defense Health Agency (DHA) maintains a formulary of prescription drugs that are covered by the TRICARE pharmacy program. DHA’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee develops and maintains this formulary by evaluating new drugs that come to market and reevaluating existing drugs. In fiscal year 2021, there were 650 drugs on DHA’s basic core formulary, the list of drugs military pharmacies were required to have in stock. DHA officials reported that, as of July 2023, the basic core formulary had been superseded by a new policy, which established the Uniform Formulary as the formulary for military pharmacies. In October 2024, the Uniform Formulary included 4,419 drugs, although military pharmacies were not required to keep all of these drugs in stock at all times.

DHA officials told us that the TRICARE formulary is constantly changing to reflect new information on the efficacy and safety of drugs. For example, in May 2024, the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee recommended adding 10 drugs to the formulary that had been newly approved by the Food and Drug Administration, such as a new treatment to reduce the risk of relapse of certain cancers. In addition, in November 2023, the committee recommended removing the brand name drug Lodoco, indicated for the prevention of stroke and certain heart conditions, from the TRICARE formulary because it determined that the drug had little to no clinical benefit compared with its generic equivalent that is just as effective and costs less.

Copayment. A copayment is an amount beneficiaries must pay to fill a prescription. TRICARE pharmacy copayments are established by law and have tended to increase every few years. Copayments vary by how a drug is categorized in the formulary, type of pharmacy beneficiaries use to obtain their prescriptions, and active duty status. (See table 3.)

|

Pharmacy |

Type of prescriptiona |

|||

|

|

Generic formularyb |

Brand-name formularyb copayment |

Non-formularya copayment |

Non-covered drugs copaymente |

|

Militaryc |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

Not available |

|

Mail orderc |

$13 |

$38 |

$76 |

Not available |

|

Network retaild |

$16 |

$43 |

$76 |

Full cost of drug |

Source: Defense Health Agency documents and 10 U.S.C. 1074g(a)(6). | GAO‑25‑107187

Note: Active-duty service members have no pharmacy copayments for covered drugs when using military pharmacies, retail, or mail order pharmacies.

aTRICARE offers formulary and non-formulary drugs. Formulary drugs are those on Defense Health Agency’s list of covered drugs. Non-formulary drugs can be obtained at formulary drug costs if medical necessity is established by the provider.

bA brand-name drug is a drug marketed under a proprietary, trademark-protected name. After any patent and market exclusivity for the brand-name drug expires, other drug companies may develop a generic equivalent, a similar drug that has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, route of administration, and intended use.

cPrescriptions filled at a military pharmacy or through TRICARE mail order pharmacies are limited to a 90-day supply.

dBeneficiaries may obtain up to a 90-day supply with multiple copayments (1 per 30 days) at a retail pharmacy, although some prescriptions may be subject to quantity limits. After two courtesy fills of certain maintenance drug at a retail pharmacy, beneficiaries except active-duty service members must obtain refills for select brand-name maintenance drugs through military or mail order pharmacies.

eDrugs that are not covered by the TRICARE pharmacy benefit.

Utilization management. DHA uses these practices to help ensure that the use of drugs and other medical services is based on medical necessity, efficacy, and appropriateness. DHA made some utilization management changes during our review period, including prior authorization. In certain instances, DHA requires beneficiaries to obtain approval, referred to as a prior authorization, for a drug to ensure coverage. In the TRICARE Pharmacy Services, Fifth Generation (TPharm5) contract, DHA expanded its monitoring of the contractor’s administration of prior authorizations. Under TPharm5, the number of prior authorizations conducted initially increased. According to DHA officials, multiple factors drove this increase, including the transition to a new electronic health record system with centralized prior authorization reporting processes and the increase in coverage of drugs that may require prior authorization (e.g., specialty drugs, continuous glucose monitoring devices, and weight loss drugs).

Administration. DHA made some changes to how its contractor administers the TRICARE program. DHA has required that network pharmacies be fully licensed in accordance with applicable federal and state laws. In the TPharm5 contract, DHA allows its contractor to remove a pharmacy from the TRICARE retail network without providing advance notice to the government or beneficiaries if that pharmacy fails to meet required credentialing standards. The contractor must eventually notify the government and beneficiaries within 14 days of this change.

Reporting. DHA requires its contractor to report on aspects of the pharmacy program. In the TPharm5 contract, DHA added a requirement that its contractor is to submit an annual plan describing how beneficiaries outside of access standards can access pharmacy services.

Beneficiary services. DHA’s pharmacy contractor is required to provide beneficiaries a range of services as part of the TRICARE pharmacy program. In the TPharm5 contract, DHA added a clause that its mail order pharmacy contractor is to provide beneficiaries with delivery management services to include timely delivery of drugs to align with treatment schedules and delivery tracking.

GAO Contacts

Sharon M. Silas, (202) 512-7114, SilasS@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Patricia Roy (Assistant Director), Kelly Turner (Analyst-in-Charge), Ángela González Yanes, and Dan Sosa made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were Ying Hu, Deborah Healy, Jacquelyn Hamilton, Teague Lyons, and Roxanna Sun.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Over the last decade, increased spending on prescription drugs among private health plans and TRICARE alike has been driven by growth in the use of high-cost specialty drugs. For example, in fiscal year 2023, specialty drugs accounted for less than 1 percent of all TRICARE prescriptions and yet comprised 52 percent of total spending on prescription drugs. At the same time, TRICARE and private health plans have also been seeking to mitigate other changes in the retail pharmacy industry, including increased consolidation and closures, leaving fewer retail pharmacies available to meet patient needs.

[2]S. Rep. No. 118-58, at 167-68 (2023).

[3]In this report, we refer to data from DHA’s TPharm5 contractor as contractor data.

[4]We interviewed pharmacy representatives from AlignRx, Community Oncology Association, EPIC Pharmacies, Inc., National Association of Chain Drug Stores, National Association of Specialty Pharmacy, National Community Pharmacist Association, and Senior Care Pharmacy Coalition. Through these interviews, we spoke with nine individuals who reported that they collectively owned 136 retail pharmacies.

We interviewed beneficiary representatives from Exceptional Families of the Military, Military Officers of America Association, National Military Families Association, and TRICARE for Kids.

[5]For example, DHA officials also told us that a change in their calculation of beneficiary proximity to a retail pharmacy was significant. However, because this change did not directly affect beneficiary access, we did not include it in our list of key changes for this review.

[6]The definition of specialty drug varies across insurers. DHA has adopted guidelines for the designation of a drug as a specialty drug. These include 1) one or more of the following clinical factors: difficult to administer, special handling or storage, intense monitoring, high risk of adverse drug events, frequent dose adjustments, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy programs in place, benefits from ongoing training for patients, class not widely used in practice, and other drugs in the class are designated as specialty; 2) the cost of the drug to DHA falls in the top 1 percent of spending (cost per 30-day supply); or 3) on further review, designation of the drug as specialty continues to provide value to the patient, DHA, or both. For example, Firmagon, indicated for treatment of advanced prostate cancer and delivered by injection, is considered a specialty drug.

[7]Pharmacy industry standards include those established by the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission, which sets standards that specialty pharmacies it accredits are required to meet.

[8]Federal internal control standards state that agencies should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate the results (Principle 16). See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

Department of Defense, Defense Health Agency Procedural Instruction 6025.08 Pharmacy Enterprise Activity (Aug. 14, 2018).

[9]Copayment amounts are set in law at 10 U.S.C. § 1074g(a)(6) and depend on a beneficiary’s active duty status, a drug’s formulary status, whether a drug is generic or name brand, and where a beneficiary fills the prescription. For example, military pharmacies do not charge a copayment for most drugs. Beneficiaries who fill prescriptions at out-of-network pharmacies must pay full price for their prescription and submit claims for reimbursement, which are subject to applicable deductibles or out-of-network cost-shares and copayments. See Department of Defense, TRICARE Pharmacy Program Handbook (Jan. 2024).

[10]Contractor representatives told us that they made these changes in October 2022 to achieve the best value for the government and minimize the risk of overwhelming beneficiaries and retail pharmacies that are often occupied with benefit changes for non-TRICARE health plans in January of each year.

[11]These standards are described in more detail later in this report.

[12]We also identified other changes to the TRICARE pharmacy program that did not meet our definition of a key change. See appendix I for an overview of some of these changes.

[13]In-network pharmacies are those that the TRICARE pharmacy contractor contracts with to provide pharmacy services to TRICARE beneficiaries for predetermined copayments. At non-network pharmacies, beneficiaries must pay the full cost of a drug up front, then submit a claim for reimbursement.

[14]DHA officials told us that, in January 2025, the agency expects to complete an assessment of the financial impact of the TPharm5 contract through fiscal year 2024.

[15]The pharmacy contractor independently negotiates the terms of its contacts with retail pharmacies; DHA does not have contractual privity with the pharmacies and does not participate in related negotiations.

[16]The contract does not specify that a minimum number of independent pharmacies be in the TRICARE retail pharmacy network.

[17]Unlike traditional pharmacies that focus on providing a range of prescription drugs for beneficiaries, specialty pharmacies focus on filling prescriptions for specialty drugs, which include those that need special storage and handling. Because of this focus, specialty pharmacies generally have access to a wider array of specialty drugs than traditional pharmacies.

[18]For example, between the first quarter of 2021 and the third quarter of 2024, beneficiaries’ use of specialty drugs increased 39 percent, when adjusted for DHA’s reclassification of certain drugs as specialty drugs in January 2023.

[19]Prior to the implementation of this requirement in March 2024, TRICARE beneficiaries had been required to refill prescriptions for certain maintenance medications from the contractor-operated mail order pharmacy or from military pharmacies as a result of the Carl Levin and Howard P. ‘Buck’ McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015. According to DHA officials, the maintenance medications affected by this requirement include both specialty and non-specialty drugs.

As of September 2024, 27 percent of the drugs on DHA’s specialty drug list were certain maintenance medications. Beneficiaries taking these drugs may obtain them at a retail pharmacy for up to two 30-day fills before they are required to transfer their prescription to a military pharmacy or the specialty pharmacy. These fill limits do not apply to active duty service members, or beneficiaries with other prescription drug coverage or who live overseas. If TRICARE’s specialty pharmacy is unable to fill the prescription, the beneficiary may obtain the drug through a retail pharmacy. In addition, DHA’s contractor may grant a waiver enabling a beneficiary to obtain more than two fills of the specialty drug at a retail pharmacy based on personal need, hardship, emergency, or special circumstances.

[20]DHA officials reported that the agency had previously used the national prime vendor to replenish the government-contracted stock of non-specialty drugs and a limited number of specialty drugs dispensed at military pharmacies and the mail order pharmacy.

[21]The national prime vendor can obtain drugs at a fixed percentage discount off the lowest price otherwise available for each drug, which is generally 24 percent less than nonfederal average manufacturer prices for non-generic products. See 38 U.S.C. § 8126(a)(2).

[22]TPharm5 contract standards for the percentage of beneficiaries required to have a network pharmacy within a 15-minute drive of their home is proprietary. To calculate this measure, the contractor uses government-provided beneficiary zip code files and geospatial software to calculate beneficiaries’ proximity to a network pharmacy. The calculation of the percentage of beneficiaries meeting this proximity standard does not include 1) pharmacies located on or affiliated with military treatment facilities, Department of Veterans Affairs, Public Health Service, or Indian Health Service facilities and 2) beneficiaries residing on military bases or who live outside the U.S. and territories.

[23]DHA’s monitoring of the contractor’s timeliness in dispensing mail order traditional drugs includes whether the contractor has shipped, scheduled delivery, returned, placed in process, or denied all prescriptions from the time a prescription is received. DHA monitored the contractor’s timeless in dispensing traditional drugs under the TPharm4 contract and continues to do so under the TPharm5 contract.

[24]These data indicate that, for example, DHA’s mail order specialty pharmacy filled 64 percent of beneficiaries’ specialty drug prescriptions in the third quarter of 2024.

[25]Department of Defense, Procedural Instructions 6025.08.

[26]While we identified inaccuracies in some contractor data, we did not find errors in the network size or beneficiary proximity to a pharmacy data that DHA uses to monitor beneficiary access. As such, we determined that those data were sufficiently reliable to describe key changes to the TRICARE pharmacy program.

[27]DHA requires the pharmacy contractor to provide beneficiaries with 30 days written notification if a pharmacy they have used during the prior 6 months is leaving the network.

[28]Data reflect beneficiaries who had used a pharmacy up to 6 months prior to that pharmacy leaving the network.

From November 2022 through January 2023, an additional 2,484 pharmacies left the TRICARE retail pharmacy network, resulting in about 300,000 beneficiaries needing to find a new pharmacy. Contractor data do not show whether some of these beneficiaries were the same as those affected in October 2022. Therefore, we are unable to determine the exact number of unique beneficiaries affected when DHA reduced the minimum required number of pharmacies.

[29]In addition, under the TPharm5 contract, DHA excluded roughly 1.5 million beneficiaries who lived on or near military bases in its retail pharmacy proximity standard calculations. DHA officials told us the reason for the military base exclusion is that retail pharmacies do not operate on military bases, and military pharmacies are available for beneficiaries on military bases. Beneficiaries on or near military bases can still obtain prescriptions at military, retail, or mail order pharmacies.