RENTAL HOUSING

Use and Federal Oversight of Property Technology

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Alicia Puente Cackley at CackleyA@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107196, a report to congressional requesters

Use and Federal Oversight of Property Technology

Why GAO Did This Study

Some policymakers have raised questions about the use of property technology tools in the rental housing market, including their potential to produce discriminatory or unfair outcomes for renters. GAO was asked to assess various aspects of property technology use in the rental housing market. This report examines (1) the use of four selected property technology tools, (2) their potential benefits and risks for owners and renters, and (3) federal agencies’ oversight of these tools.

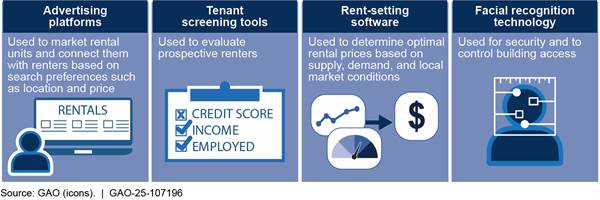

GAO focused on four commonly used types of property technology tools (see figure). GAO reviewed studies by federal agencies and advocacy and industry groups; agency guidance and documentation; and rulemakings, legal cases, and enforcement actions issued in 2019–2024. GAO also interviewed officials of four federal agencies responsible for enforcing statutes that address housing discrimination; anticompetitive, unfair, or deceptive acts affecting commerce; and the use of consumer credit reports; and representatives of 12 property technology companies, 10 public housing agencies, and nine advocacy or industry groups (nongeneralizable sample groups, selected for their expertise in or use of these technologies).

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that HUD provide more specific written direction to public housing agencies on the use of facial recognition technology.

What GAO Found

Property technology broadly refers to the use of software, digital platforms, and other digital tools used in the housing market. Property owners and renters use these technologies for functions including advertising, touring, leasing, and financial management of rental housing. These tools may incorporate computer algorithms and artificial intelligence.

Property technology tools used for advertising, tenant screening, rent-setting, and facial recognition have both benefits and risks. For example, facial recognition technology can enhance safety, according to three industry associations and all 10 of the public housing agencies in GAO’s review. However, these tools also may pose risks related to transparency, discriminatory outcomes, and privacy. For instance, potential renters may struggle to understand, and owners to explain, the basis for screening decisions made by algorithms. Facial recognition systems also might misidentify individuals from certain demographic groups, and property owners might use surveillance information without renter consent, according to advocacy groups GAO interviewed.

The four federal agencies took several actions to address these risks. To combat alleged misleading and discriminatory advertising on rental platforms, agencies pursued legal action and obtained settlements requiring changes to advertising practices and improved compliance with the Fair Housing Act. They also took enforcement actions against tenant screening companies for using inaccurate or outdated data.

However, all 10 public housing agencies stated public housing agencies would benefit from additional direction on use of facial recognition technology. The Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) current guidance to these agencies is high-level and does not provide specific direction on key operational issues, such as managing privacy risks or sharing data with law enforcement. More detailed written direction could provide public housing agencies additional clarity on the use of facial recognition technology and better address tenant privacy concerns.

Abbreviations

|

CFPB |

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

FCRA |

Fair Credit Reporting Act |

|

FTC |

Federal Trade Commission |

|

HUD |

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

|

PHA |

public housing agency |

|

proptech |

property technology |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 10, 2025

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Property owners and renters increasingly rely on property technology (proptech), which in the rental housing context broadly refers to software, digital platforms, and other digital tools used for advertising, leasing, management, and maintenance. These tools may incorporate technologies such as algorithms and artificial intelligence, including machine learning models.[1]

Proptech tools can make it easier for renters to search for, view, and lease housing, and for owners to manage their units. But some policymakers have raised questions about the use of these tools and the potential for discriminatory, unfair, or anticompetitive outcomes for renters.

You asked us to assess various aspects of proptech use in the rental housing market. This report examines (1) selected proptech tools available in the rental market, how they are used, and by whom; (2) the benefits and risks that selected proptech tools may pose for owners and renters; and (3) steps taken by federal agencies to oversee these selected proptech tools.

To identify available proptech tools, we reviewed reports from federal regulators, academics, industry groups, and advocacy organizations and identified thirty-four tools. We then purposively selected four tools that incorporate artificial intelligence and are used by owners and renters in the rental housing process: advertising platforms, tenant screening tools, rent-setting software, and facial recognition technology.[2]

For the first two objectives, we interviewed representatives of five advocacy organizations, four industry associations (that represent owners and managers), and two organizations participating in the federal Fair Housing Initiative Program (which seeks to combat housing discrimination), as well as a nongeneralizable sample of 12 companies that provided the selected proptech tools. These consisted of three advertising companies, three tenant screening companies, four facial recognition companies, and two rent-setting software companies. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives of a nongeneralizable sample of 10 public housing agencies (PHA).

For the third objective, we reviewed guidance and documentation from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the Department of Justice (DOJ) the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), final rulemakings, federal court orders, enforcement actions, and relevant advisory opinions issued by these agencies from 2019 through 2024.[3] We analyzed HUD communications to PHAs regarding use of surveillance technology and assessed them against relevant federal internal control standards.[4]

For all three objectives, we reviewed relevant laws, regulations, agency reports and guidance, and interviewed representatives from four federal agencies: the CFPB, DOJ, FTC, and HUD.

See appendix I for additional information about our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Agency Enforcement Roles and Responsibilities

Federal agencies generally do not have a direct role in monitoring or overseeing the use of proptech tools in the rental housing market. Instead, several agencies are tasked with enforcing statutes that broadly address housing discrimination; anticompetitive, unfair, or deceptive acts affecting commerce; and the use of consumer credit reports. The federal agencies with oversight and enforcement responsibilities for laws relevant to selected proptech tools include HUD, FTC, CFPB, and DOJ (see table 1).

|

Law |

Key requirements |

Key federal agencies with statutory oversight and enforcement responsibilities |

|

Fair Housing Act |

Prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental, or financing of housing, and other housing-related decisions based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, familial status, or disability. |

DOJ, HUDa |

|

Fair Credit Reporting Act |

Requires a permissible purpose to obtain a consumer credit report (including tenant screening reports) and that consumer reporting agencies follow reasonable procedures to assure the maximum possible accuracy of consumer reports. Imposes disclosure requirements on users of consumer reports who take adverse action on credit applications based on information contained in a consumer report. Imposes requirements on furnishers of information to consumer reporting agencies for consumer reports regarding the accuracy and integrity of furnished information. |

CFPB,b DOJc, FTC |

|

Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act |

Prohibits unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce. |

FTC |

|

Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Antitrust Act |

Outlaws all contracts, combinations, and conspiracies that unreasonably restrain or monopolize interstate and foreign commerce or trade practices including price fixing and bid rigging. |

DOJ |

Source: GAO analysis of relevant laws applicable to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Department of Justice (DOJ), Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). | GAO‑25‑107196

aDOJ may bring Fair Housing Act cases on its own or based on referral from HUD when HUD finds reasonable cause, issues a charge of discrimination, and a party elects to proceed in federal court.

bOn February 9, 2025, the National Treasury Employees Union and others filed a lawsuit in the District Court for the District of Columbia alleging that the actions of the Acting Director, including actions regarding staffing and enforcement work, violated the Administrative Procedure Act and the Dodd-Frank Consumer Protection and Wall Street Reform Act and were unconstitutional because they interfered with Congress’ ability to appropriate funds and create statutory functions for agencies. Nat’l Treasury Emp. Union, et al. v. Vought, No. 1:25-cv-00381 (D.D.C. filed Feb. 9, 2025). As of May 2025, the litigation is active and continues in both US Circuit and Appeals Court.

cFTC and CFPB share enforcement of the Fair Credit Reporting Act as it applies to tenant screening, which is coordinated under a memorandum of understanding. DOJ may assist or supervise related federal court cases.

More specifically, HUD’s Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity is responsible for enforcing the Fair Housing Act, which prohibits discrimination in nearly all housing and housing-related transactions based on protected characteristics.[5] This office issues guidance to assist owners and companies in complying with Fair Housing Act requirements. It also processes and investigates complaints alleging civil rights violations and conducts compliance reviews of HUD funding recipients. After a complaint is filed, HUD attempts to conciliate the matter before issuing a charge or dismissal.

If conciliation fails, HUD may refer the matter to DOJ. DOJ may bring a case in federal court if HUD investigated the complaint or issued a charge and one of the parties elected to proceed in court. In fair housing cases, DOJ can seek injunctive relief—such as training and policy changes—monetary damages, and civil penalties in pattern or practice cases.[6]

FTC and CFPB enforce the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), including oversight of consumer reporting agencies.[7] These agencies assemble or evaluate consumer information—such as employment, criminal, rental, eviction, and credit history—into consumer reports provided to third parties, including rental property owners who use them to determine eligibility for rental housing. Both FTC and CFBP can investigate and initiate enforcement action against consumer reporting agencies that violate FCRA requirements, such as those for ensuring accuracy.

In addition to enforcement, FTC and CFPB seek input from and publish resources for the public.[8] Both CFPB and FTC can bring actions for alleged FCRA violations. FTC can seek injunctive relieve on its own but must seek civil penalties through DOJ in federal district court. CFPB can bring its own cases alleging FCRA violations for civil penalties and injunctive or other relief.

FTC enforces Section 5 of the FTC Act, which prohibits unfair methods of competition or deceptive acts or practices affecting commerce.[9] Under this authority, FTC may investigate and initiate enforcement actions if it has reason to believe a violation occurred or is occurring. The FTC Act allows the agency to seek cease-and-desist orders or injunctive relief, impose civil penalties for violations of its orders or certain rules, and obtain consumer redress in certain circumstances.

HUD Administration and Oversight of Subsidized Housing

In addition to enforcing the Fair Housing Act, HUD plays a role in administering and overseeing subsidized housing programs.

Office of Public and Indian Housing. This office administers the Public Housing and Housing Choice Voucher programs, two of HUD’s largest subsidized housing programs.[10] PHAs—typically municipal, county, or state agencies created under state law—operate both programs. Under the Public Housing program, HUD provides subsidies to PHAs, which own and operate rental housing designated for eligible low-income households. Under the Housing Choice Voucher program, HUD provides rental subsidies, through PHAs, that renters can use to obtain housing in the private market.

Office of Policy Development and Research. This office develops fair market rents, which are used to determine the maximum allowable rent for Housing Choice Voucher recipients. Fair market rent generally reflects the cost of renting a moderately priced unit in a local housing market. HUD calculates and publishes these rents annually for thousands of locations.

Owners and Renters Use Proptech Tools for Listing, Searching, Screening, and Rent-Setting

Owners and renters may use one or more of the four types of proptech tools we reviewed—advertising platforms, tenant screening tools, rent-setting software, and facial recognition technology—for functions including advertising, rent-setting, screening tenants, and controlling access.

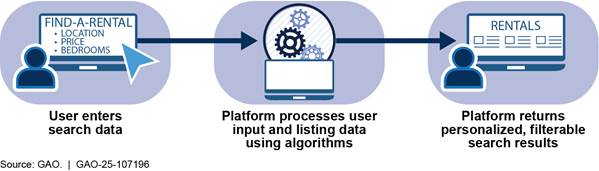

Advertising platforms. These platforms allow owners to list rental properties on websites for prospective renters to view (see fig. 1). Features may include targeted advertising, virtual touring, and rent estimates. Algorithms and machine learning may be used to personalize search results by tailoring recommendations based on user data. Other platform features may include rental-management tools for landlords, such as application intake, tenant screening, electronic lease signing, and rent collection.

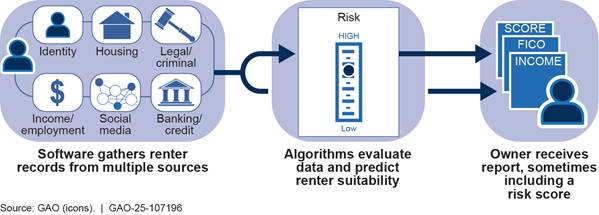

Tenant screening tools. Property owners use tenant screening tools to assess the suitability of prospective renters for a rental unit (see fig. 2). The tools assemble and evaluate tenant background information such as credit and criminal history, employment and income verification, and rental payment or eviction history to generate a screening report. Owners may use these reports to attempt to evaluate an applicant’s likelihood of fulfilling lease obligations.[11] Some tools use machine learning to analyze patterns in applicant data to attempt to predict a prospective renter’s reliability based on historical trends. These predictions may be presented as a score or recommendation that owners consider when deciding whether to approve an applicant.

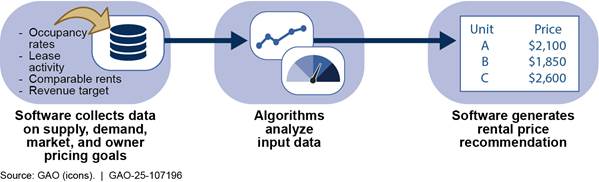

Rent-setting software. Also known as revenue management software, these tools help property owners determine rents by generating data-driven pricing recommendations (see fig. 3). They may use proprietary or public data, such as occupancy rates, market trends, and comparable unit prices. This tool may also apply artificial intelligence techniques, including machine learning, to forecast demand and suggest optimal rental levels. The software allows owners to adjust rents in response to current market conditions and their own pricing objectives.

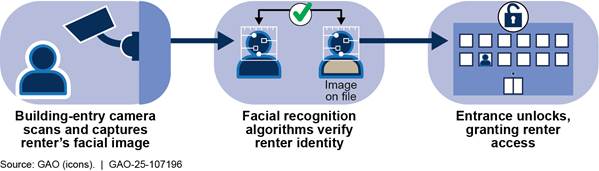

Facial recognition technology. Building owners use facial recognition technology for security, including access control (see fig. 4). For example, cameras installed at building entrances use software to verify a renter’s identity by comparing their face to a database of stored images. A successful match allows entry. The software uses computer vision, a type of artificial intelligence, to recognize faces in real time, verify identities from images, and improve accuracy over time through learning.

Selected Proptech Tools Can Offer Convenience and Safety but Also Pose Privacy, Bias, and Other Risks

Online Listing Platforms Can Benefit Owners and Renters but Carry Risks Such as Misrepresentation

Online listing platforms can provide several benefits for owners and renters, according to the industry associations and advertising companies we interviewed, including the following:

Wider advertising reach. Owners can use third-party advertising features to extend the visibility of their listings across multiple platforms. These tools use algorithms to target potential renters more efficiently than traditional print advertising. They also can save owners time by creating one listing that can be displayed across various websites and social medial platforms. Broader exposure can help fill vacancies more quickly and maximize rental income.

Convenience and cost savings of virtual tours. Listing platforms allow potential renters to take virtual tours—often in three-dimensional formats—that show a unit’s floor layout. Virtual touring is available at any time and may reduce travel and other costs. It also helps individuals with mobility or accessibility limitations assess whether a unit meets their needs without having to physically be present at the unit.

Cost savings and efficiencies from universal applications. One company with which we spoke offers “universal” rental applications for potential renters and property owners. The service is free for owners who accept the application. Prospective renters submit a single form and pay one fee to apply to multiple units over a 30-day period.

However, representatives of advocacy groups and officials from federal agencies we interviewed noted that advertising tools posed potential risks to renters, including potential misrepresentation and discrimination.

Misrepresentation of listings or costs. Owners may post fraudulent or misleading images, including altered or staged photographs. For example, potential renters may rely on pictures and videos provided in a virtual tour, but owners could manipulate these images to make rooms appear larger or smaller than they are. Owners also may make unclear statements about rent costs. For example, rent may be advertised online in a way that obscures actual costs, or fees for amenities like gyms or conference rooms may be hidden until move-in.

Discriminatory advertising. Platforms or owners may limit who sees listings or include language that discourages renters on a prohibited basis, such as by protected classes. For example, phrases such as “no children” or “no wheelchairs” may violate the Fair Housing Act by discriminating on the basis of familial status or disability. Unlike traditional print advertising, where a listing is provided in writing and a landlord subsequently assesses applicants, algorithms may analyze characteristics such as income or location and steer certain users to or from specific listings before they can apply. This practice may reduce housing access for minorities, women, families with children, and individuals with disabilities.

Online platforms use several approaches to help mitigate these risks, according to representatives from one of the three advertising companies we interviewed. For example, this company said its platform includes a rental cost and fee calculator that helps potential renters understand the full cost of a unit. The tool lists associated fees and expenses, such as monthly costs for utilities, parking, and pet fees, as well as one-time charges like security deposits and application or administrative fees. This company described a set of controls designed to prevent discriminatory advertising. These include keyword detection logic to filter potentially discriminatory language—for instance, blocking phrases that discourage families with children. The platform also displays information about relevant federal, state, and local fair housing laws to owners before they upload a listing. In addition, the website allows users to report potential discriminatory content for manual review by the company.

Screening Technology Can Help Owners Manage Risks, but Inaccurate Information May Result Denials

According to industry associations, and representatives from two companies we interviewed, owners benefit from tenant screening tools in part because they help mitigate renter-based risks, including the following:

Failure to meet lease obligations. Screening tools may help owners assess background information to reduce the risk a renter might not fulfill lease terms. For example, reviewing a prospective renter’s rent payment and credit history may help owners identify applicants with a lower risk of nonpayment.

Fraud risks. Screening algorithms assist owners in verifying information that potential renters provide. This verification helps reduce risks of identity fraud (false names, Social Security numbers, or birth dates) and synthetic fraud (fabricated documents, such as pay stubs).

Potential risks and challenges related to using screening reports include the following:

Inaccurate information. Tenant screening reports often contain inaccurate information, which can lead to unwarranted rental application denials. For example, of the approximately 26,700 screening-related complaints submitted to CFPB from January 2019 to September 2022, approximately 17,200 were related to inaccurate information.[12] Specifically, these complaints noted challenges obtaining housing—for instance, due to information erroneously included in their report; outdated information that legally should not have been included; and inaccurate arrest, criminal, and eviction records.

Model transparency issues. As we previously reported, models using algorithms can produce unreliable and invalid results.[13] Advocacy groups noted that algorithms may present a recommendation to the owner without disclosing the specific data used or how it was weighted. As a result, owners and renters may be unable to identify or correct errors, and renters may be unable to submit mitigating information to improve their chances of securing housing.

Disparate impact. Screening algorithms that rely on criminal history and eviction records may have an adverse impact on minorities, including Black and Hispanic applicants, according to advocacy group officials.[14] For example, algorithms that recommend rejecting applicants with any criminal or eviction record may disproportionately affect these groups due to their overrepresentation in the criminal justice and housing court systems. This may contribute to reduced housing access and increased housing instability. In addition, algorithms may not differentiate between serious offenses and minor ones that are unlikely to affect renter’s reliability.

Representatives of tenant screening companies we interviewed reported taking several steps to help mitigate these risks. For example, one company allows potential renters to review their background information and submit comments to the owner before applying. Renters can flag inaccuracies or provide a narrative to explain circumstances the owner might otherwise overlook. In addition, three companies told us they review and subsequently correct inaccurate information on a tenant screening report if notified by a renter or owner.

Rent-Setting Algorithms Offer Owners Pricing Insights but May Lead to Higher Rents

Representatives from two industry associations, HUD officials, and representatives from one company offering rent-setting software noted that owners and renters may benefit from the use of tools that provide rent-setting algorithms in several ways, including the following:

Responsiveness to market changes. Rent-setting algorithms may help owners adjust rents more quickly in response to changing market conditions. This can help owners achieve their desired occupancy rates, keep their properties at their desired level relative to the market, and minimize revenue lost from unintended vacancies.

Improved accuracy in HUD fair market rents. HUD incorporates data from private market sources that includes a rent-setting tool to enhance the accuracy and representativeness of its fair market rent calculations.[15] According to HUD officials, incorporating private-market data helps address gaps in public data sources, such as census data, which may be outdated or lack coverage in certain markets. HUD officials stated that more accurate and timely fair market rent calculations can help renters with Housing Choice Vouchers find suitable, affordable housing.

However, representatives of advocacy groups also told us that renters face several risks when owners use rent-setting algorithms, including the following:

Reduced bargaining power. When owners rely on rent-setting algorithms to standardize rental prices across a geographic market, advertised rents may increase and renters may have less ability to negotiate lower prices. Algorithms may recommend rents that owners treat as a market benchmark, limiting flexibility to lower prices, even when individual renters attempt to negotiate. Advocacy groups expressed concern that this effect is especially pronounced in tight housing markets, where limited supply further constrains renters’ leverage.

Potential increases in rental housing costs. According to University of Pennsylvania researchers, owners using rent-setting software adjusted rents more responsively to changing market conditions compared to other property owners.[16] This included increasing rents and reducing occupancy rates during periods of economic growth.[17] Moreover, this pattern was also found at the geographic level when, during periods of economic growth, higher levels of rent-setting software were associated with higher rent levels and lower occupancy rates. Advocacy groups we spoke to reiterated these findings, noting that dependent on market conditions, the use of a rent-setting algorithm can lead to higher rents for some renters.

Facial Recognition Technology Can Enhance Security but Pose Privacy Risks

Representatives from three of the four industry associations and all 10 of the PHAs we spoke to told us that the use of facial recognition technology can enhance safety for both private and subsidized rental housing. Owners and PHAs may install surveillance cameras equipped with facial recognition technology to improve property security. Industry association and PHA officials overseeing properties with such technology told us that it can enhance safety by helping ensure that only renters and their authorized guests can enter buildings. They noted that the technology may reduce the risk of unauthorized individuals entering public housing facilities and engaging in criminal activity.

However, representatives from advocacy organizations we interviewed raised concerns about the use of facial recognition technology in rental housing, citing risks related to accuracy, privacy, and informed consent.

Error rates. Advocacy groups we interviewed expressed concerns about facial recognition technology’s higher error rates for identifying and verifying individuals from certain demographics—particularly Black women. In the rental housing context, such inaccuracies could result in frequent access denials for some individuals.[18] Representatives of facial recognition companies cited several factors that may contribute to these errors, including poor lighting, facial expressions, and obscured facial features. They also noted that data quality—including outdated or low-resolution images used for comparison—may also affect accuracy.[19]

Privacy and consent. Facial recognition technology relies on the use of biometric information, which is unique to each person. Representatives from advocacy groups we interviewed expressed concern that surveillance data collected by owners could be used without renter consent. For example, owners could share this information with law enforcement or use it for action against a renter, such as an eviction or fine. Additionally, representatives of 6 of the ten PHAs we interviewed expressed uncertainty about what steps they should take to obtain consent when using facial recognition technology as part of their housing operations.

Federal Agencies Addressed Some Proptech Risks, but HUD Could Further Mitigate Risks

Federal agencies took several actions to address risks related to selected proptech tools.[20] However, HUD has opportunities to further mitigate risks related to facial recognition technology in public housing.

Agencies Took Steps to Address Allegedly Misleading and Discriminatory Advertising Practices

To address potential risks associated with online listing platforms—specifically, misleading advertisements and discriminatory advertising—FTC, HUD, and DOJ initiated legal actions and HUD issued guidance.

Misleading advertisements. In 2022, FTC initiated a lawsuit against Roomster, a platform for rental housing and roommate listings.[21] FTC alleged that the company participated in deceptive acts or practices in violation of Section 5 of the FTC Act because its website contained inaccurate rental listings and misleading or fake consumer reviews. A federal court issued a stipulated order requiring the company to stop misrepresenting its listings, investigate any consumer complaints, and pay a fine.

Discriminatory advertising practices. In March 2019, following a complaint and investigation, HUD issued a Charge of Discrimination against Meta alleging that its advertising platform violated the Fair Housing Act by allowing advertisers to target or exclude users based on protected characteristics. For example, Meta’s platform included a toggle feature that allowed advertisers to exclude men or women from viewing an advertisement.[22]

The case was referred to DOJ, which filed suit in in 2022. DOJ alleged that Meta’s advertising delivery system used algorithms that considered traits such as familial status, race, religion, and sex.[23] As part of the settlement, Meta agreed to stop using an advertising tool known as the Special Audience Tool, develop a new system that would address racial and other disparities caused by its use of personalization algorithms in its advertisement delivery system for housing, and eliminate targeting options related to protected characteristics under the Fair Housing Act.

In April 2024, HUD’s Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity issued guidance outlining advertising practices that may violate the Fair Housing Act when used to categorize or target online users.[24] These include advertisements that discourage certain groups from applying, offer different prices or conditions based on protected characteristics, or steer individuals toward specific neighborhoods. The guidance advised housing providers to avoid targeting options that directly or indirectly relate to protected characteristics. It also encouraged platforms to test their systems to ensure advertisements are not delivered in a discriminatory fashion.

Agencies Took Enforcement and Other Actions to Address Tenant Screening and Reporting Issues

Federal agencies have taken steps to address issues related to the accuracy and potential adverse impact of tenant screening tools. These steps include issuing guidance, taking enforcement actions and filing a statement of interest.

Guidance on Tenant Screening Tools. Also in April 2024, HUD issued guidance on applying the Fair Housing Act to screening of rental housing applicants.[25] HUD’s Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity published the guidance on its public website. The guidance also addressed the application of the Fair Housing Act to tenant screening processes that use artificial intelligence and machine learning. It included best practices for rental housing owners and tenant screening companies to support compliance with fair housing laws and mitigate artificial intelligence-related and other risks. To address inaccuracy risks, the guidance recommended that owners give applicants an opportunity to dispute the accuracy or relevance of negative information in a tenant screening report. To improve transparency, it advised tenant screening companies to include all relevant information behind a denial decision, particularly when artificial intelligence tools are used and the outcome may be difficult to explain. In February 2025, we observed that HUD had removed the tenant screening guidance from its public website. HUD provided two explanations for the removal: (1) In March 2025, HUD officials told us the guidance was taken down as part of an agencywide review of its policies and guidance to ensure consistency with an executive order; and (2) in March 2025, HUD told us the agency was updating its website and the guidance remained in effect.[26]

AppFolio. In December 2020, DOJ and FTC, sued AppFolio, Inc. a tenant screening company, for violating FCRA. The complaint alleged that the company used incorrect and obsolete eviction and criminal arrest records—some more than 7 years old—in its tenant screening reports.[27] The agencies also alleged the company failed to use reasonable procedures for accuracy, relying on third-party data without sufficient verification. As part of the settlement, the company agreed to pay a fine and implement corrective measures to improve its accuracy procedures.

TransUnion Rental Screening Solutions. In October 2023, FTC and CFPB jointly sued TransUnion Rental Screening Solutions and its parent company for violating FCRA.[28] The agencies alleged the company failed to follow reasonable procedures to ensure maximum possible accuracy of report content, including reporting sealed or incorrect eviction records, and did not disclose the sources of third-party information when requested by consumers. The stipulated settlements filed with the complaint in October 2023 required the company to enhance its procedures to ensure maximum possible accuracy for verifying eviction data and to pay consumer redress and a civil penalty.

Five background screening companies. In September 2023, FTC initiated an enforcement action against five background screening companies that advertised tenant screening reports (among other things), alleging violations of FCRA and Section 5 of the FTC Act.[29] FTC alleged that the companies inaccurately reported nonexistent or irrelevant criminal records—such as traffic violations—and allowed subscribers to edit their reports without adequate verification. In October 2023, a federal court entered a stipulated order that required the companies to cease certain practices unless they implemented compliance measures aligned with FCRA.

Statement of interest. In January 2023, DOJ and HUD submitted a statement of interest in the federal court case Louis et al. v. SafeRent Solutions and Metropolitan Management Group.[30] In the case, the two plaintiffs were Black rental applicants who used housing vouchers and alleged that SafeRent’s algorithm-based tenant screening tool assigned them low “SafeRent” scores, resulting in the denial of their rental applications. The plaintiffs also alleged that the tool disproportionately affected Black and Hispanic applicants by relying on factors such as credit history and non-housing-related debts, while failing to account for of housing vouchers as a reliable source of income. The agencies asserted that the Fair Housing Act applies to tenant screening companies that provide data used by housing owners to make suitability determinations. Accordingly, DOJ and HUD stated that such companies are prohibited from engaging in practices that result in discrimination based on protected characteristics.[31] In December 2024, the court approved a settlement between SafeRent, the other defendants, and the class of plaintiffs, and the case was subsequently dismissed.

HUD Has Opportunities to Further Mitigate Risks Relating to Facial Recognition

In September 2023, HUD’s Office of Public and Indian Housing published a letter advising PHAs to balance security concerns with their public housing residents’ privacy rights when using surveillance technology.[32] However, the letter does not provide specific direction on key operational issues regarding facial recognition technology. For example, it does not discuss how PHAs should manage privacy risks or share data with law enforcement.

Representatives of all 10 PHAs we interviewed stated they would benefit from additional information and direction from HUD on their use of facial recognition technology, especially on the following topics:

· Purpose specification. Six of the 10 PHAs wanted HUD to clarify the permitted uses of facial recognition technology. While they primarily use it to control building access for tenants and their authorized guests, they expressed interest in guidance on other potential uses, such as whether and how to disclose data to third parties, including law enforcement.

· Renter consent. Six of the 10 PHAs wanted guidance on what constitutes adequate renter consent. For example, they questioned whether posting signs about the use of facial recognition systems was sufficient. They also sought clarity on whether written consent is required before including tenant facial images in system databases, and what steps to take if a renter declined to provide consent.

· Data management. Five of the 10 PHAs wanted guidance on managing data collected through facial recognition systems. For example, they sought clarity on how long to retain images after a tenant moved out.

· Accuracy. One PHA wanted HUD to provide guidance on mitigating potential accuracy concerns.

HUD officials stated the agency has no plans to revise the September 2023 letter or issue additional written direction on facial recognition technology, citing the need to preserve PHAs’ autonomy in implementing it. However, as discussed earlier, representatives of six PHAs we interviewed expressed uncertainty about what steps they should take to obtain consent when using facial recognition technology as part of their housing operations.

HUD officials also stated that developing new guidance would require surveying about 3,300 PHAs to identify their information gaps, straining limited resources. However, the risks of facial recognition technology are well documented. For example, we have previously reported on concerns related to accuracy and the use of the technology without an individual’s consent.[33] As a result, we believe HUD could develop written direction for PHAs without the use of a survey.

According to federal internal control standards, program managers should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[34] By providing additional direction on use of facial recognition technology, HUD could help PHAs it oversees mitigate privacy and accuracy concerns and offer clarity on key issues such as purpose, consent, and data management.

Conclusions

The selected proptech tools we reviewed offer benefits to individuals searching for, living in, or owning or managing rental properties. However, they also can pose risks—particularly related to the accuracy of personal information and the potential for misrepresentation and discrimination. Federal agencies took steps to address these risks, but HUD has opportunities to further support PHAs it oversees. Providing additional written direction on the appropriate use of facial recognition technology would give PHAs greater clarity and help mitigate privacy and accuracy concerns.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Secretary of HUD should ensure that the Assistant Secretary for Public and Indian Housing provides additional written direction to public housing agencies on the use of facial recognition technology. For example, this direction could specify permitted uses of the technology, define what constitutes renter consent, and address data management and accuracy concerns.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HUD, CFPB, FTC, and DOJ for review and comment. These agencies provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

As agreed with your office, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, Chair of Federal Trade Commission, Acting Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Attorney General, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at cackleya@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Sincerely,

Alicia Puente Cackley

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

This report examines (1) selected property technology (proptech) tools available in the rental housing market, how they are used, and by whom; (2) the benefits and risks that selected proptech tools may pose for owners and renters; and (3) steps taken by federal agencies to oversee these selected proptech tools.

We identified thirty four proptech tools through a review of reports from federal regulators, academics, industry groups, and advocacy groups. We focused on tools that incorporate artificial intelligence and are used by owners and renters in the rental housing process. We purposively selected four types of proptech tools for examination: advertising platforms, tenant screening tools, rent-setting software, and facial recognition technology. These tools are not representative of all proptech tools used in the private and subsidized rental housing markets.

To gather information on owner and renter use of the selected proptech tools—and the associated benefits and risks—we interviewed representatives of a purposeful, nongeneralizable sample of 12 companies that provide such tools. These consisted of three advertising companies, three tenant screening companies, four facial recognition companies, and two rent-setting software companies. To identify these companies, we reviewed research reports, and publicly available lists of firms offering the selected tools to generate a list of companies. From that list, we selected companies that offered one or more of the tools and were responsive to our outreach. The information obtained from these interviews cannot be generalized to all companies that offer proptech tools in the private and subsidized rental housing markets.

In addition, we interviewed representatives from four industry associations and five advocacy organizations, selected because they published reports from 2019 to 2024 about the selected tools.[35] We also interviewed officials from two organizations funded by the Fair Housing Initiative Program, a federal program designed to assist people who believe they have been victims of housing discrimination.[36] We selected the two organizations because they work directly with renters, are in the metropolitan area with the largest number of public housing units based on Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) data and were recipients of HUD Fair Housing Initiative Program grants within the past 2 years.

To understand the use of and benefits and risks of the selected proptech tools in the subsidized housing market, we conducted semi-structured interviews with representatives of a nongeneralizable sample of 10 public housing agencies (PHA). We selected these PHAs to achieve a diversity in PHA size, Census region, and use of facial recognition technology. The information we gathered from these interviews cannot be generalized to the approximately 3300 PHAs.

To identify steps taken by federal agencies to oversee the selected proptech tools, we reviewed agency guidance, final rulemakings, federal court orders, agency enforcement actions, and relevant advisory opinions issued from 2019 through 2024. We analyzed relevant HUD documentation and interviewed HUD and selected PHA officials on HUD efforts to communicate to PHAs on the use of surveillance technology in their operations. We also compared a HUD communication to PHAs about using surveillance technology in their operations against federal internal control standards.[37] We determined that the internal control principle that program managers should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives was significant to this objective.

To address all three objectives, we also reviewed relevant laws, including the Fair Housing Act, the Fair Credit Reporting Act, the Federal Trade Commission Act, and the Sherman Antitrust Act. We also reviewed relevant regulations, such as HUD’s regulation on discriminatory advertising. In addition, we interviewed representatives from the following federal agencies: Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Department of Justice, Federal Trade Commission, and HUD. Within HUD, we interviewed officials from the Office of Public and Indian Housing, Office of Multifamily Housing, Office of Policy Development and Research, and Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity.[38]

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: Selected Actions Federal Agencies Took Related to Property Technology Use in the Rental Housing Context, 2019–2024

This appendix provides information on selected legal actions or guidance initiated by federal agencies from 2019 through 2024 related to tenant screening, advertising platforms, or rent-setting software.

Table 2: Status of Selected Legal Actions Federal Agencies Took Related to Use of Property Technology Tools in the Rental Housing Context, as of April 2025

|

DOJ |

Litigation |

Rent-setting software. In 2024, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and attorneys general from eight states initiated a civil antitrust lawsuit against RealPage, Inc, a company that develops and sells rent-setting software.a The complaint alleges that the company’s software enables rental housing owners to share confidential, competitively sensitive information—such as rental prices and lease terms—allowing them to align rents and reduce competition in violation of the Sherman Act. In December 2024, RealPage moved to dismiss, arguing that its software lacked market-wide influence and that DOJ failed to show anticompetitive effects. Additionally, in 2025, DOJ amended its complaint to include certain property owners.b |

|

HUD-DOJ |

Amicus brief |

Tenant screening. In Connecticut Fair Housing Center v. CoreLogic Rental Property Solutions LLC, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and DOJ filed a joint amicus brief in support of plaintiffs-appellants-cross-appellees. The brief asserted that tenant screening companies such as CoreLogic are subject to the Fair Housing Act—even if they are not the entities rejecting or accepting potential renters—because their reports to owners can be used to make housing unavailable. The agencies also underscored that blanket exclusions based on criminal history can disproportionately affect minority groups.c They cited HUD’s 2016 guidance warning that such practices may violate the Fair Housing Act if not based on a substantial, legitimate, nondiscriminatory interest.d |

|

DOJ |

Statement of interest |

Rent-setting software. In September 2023, plaintiffs filed an amended complaint alleging that RealPage and several property-management companies engaged in a price-fixing conspiracy in violation of Section 1 of the Sherman Act. They claimed RealPage’s rent-setting software facilitated the conspiracy by aggregating and sharing nonpublic rental data among competing property owners and managers. In November 2023, DOJ submitted a statement of interest arguing that such software enables owners to share nonpublic, sensitive information, potentially leading to coordinated rental housing prices.e This coordination, DOJ asserted, harms competition among owners and keeps prices artificially high for renters. |

|

FTC-DOJ |

Statement of interest |

Rent-setting software. In September 2023, the plaintiff filed a class action lawsuit in federal court against Yardi Systems, Inc. and multiple property management companies.f The lawsuit alleges that the defendants collaborated to fix rental housing prices using Yardi’s rent-setting software. In December 2023, the defendants moved to dismiss, contending that each company independently chose to use Yardi’s software and set rents on its own. In March 2024, DOJ and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued a joint statement of interest. They noted that owners’ collective reliance on Yardi’s rent-setting algorithm could facilitate price-fixing agreements in potential violation of the Sherman Act. The agencies also noted that even without direct communication among owners or strict adherence to algorithm’s recommendations, shared use of the technology might lead to coordinated pricing, harming consumers through reduced competition. In December 2024, the federal court denied the motion to dismiss.g |

Source: GAO analysis. | GAO‑25‑107196

aUnited States v. RealPage, Inc., No. 1:24-cv-710 (M.D.N.C. filed Aug. 23, 2024).

bThe six owners are Greystar Real Estate Partners, Cushman & Wakefield, Camden Property Trust, LivCor, Pinnacle Property Management Services, and Willow Bridge Property Company. The January 2025 amended complaint initially included Cortland Management, but on the same date the United States and Cortland reached a final judgement where Cortland agree to certain changes and to refrain from certain actions. In February 2025, following the amended complaint, RealPage filed another motion to dismiss the amended complaint which contained similar arguments on these points. As of June 26, 2025, the parties are awaiting court decisions on a motion to dismiss and a proposed final judgment.

cIn Connecticut Fair Housing Center v. CoreLogic Rental Property Solutions, the plaintiff alleged that CoreLogic’s tenant screening tool, CrimeSAFE, discriminated based on race, national origin, and disability when the tool’s use resulted in the denial of a disabled Latino man with no criminal conviction from moving in with his mother, alleging violations of the Fair Housing Act, Fair Credit Reporting Act, and the Connecticut Unfair Trade Practice Act. No. 3:18-cv-705 (D. Conn.). The United States District Court for the District of Connecticut ruled in favor of the plaintiff for the Fair Credit Reporting Act claim but ruled in CoreLogic’s favor for the Fair Housing Act and Connecticut Unfair Trade Practice Act claims. The plaintiffs appealed the district court’s denial of their Fair Housing Act claims, among others, and CoreLogic then cross-appealed the court’s decision relating to the Fair Credit Reporting Act claim. In November 2024, the parties, and the United States as amicus curiae supporting the plaintiff, presented arguments in the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. As of June 26, 2025, the Second Circuit had not issued a decision. Conn. Fair Hous. Ctr. v. CoreLogic Rental Prop. Sol., LLC, No. 23-1166 (2d Cir. argued Nov. 20, 2024).

dDepartment of Housing and Urban Development, Office of General Counsel, Guidance on Application of Fair Housing Standards to the Use of Criminal Records by Providers of Housing and Real Estate-Related Transactions (Washington D.C.: April 2016); and Guidance on Fair Housing Act Protections for Tenant Screening Practices Involving Criminal History (Washington D.C.: June 2022).

eIn re RealPage, No. 3:23-MD-3071 (M.D. Tenn). In February 2025, following the amended complaint, RealPage filed another motion to dismiss the amended complaint, which contained similar arguments on these points. As of June 2025, the court had not held oral arguments for RealPage’s motion to dismiss. The other defendant property management companies subsequently filed separate motions to dismiss on their own behalf. Settlement agreements have been reached with multiple defendants. As of June 2025, the case was ongoing.

fDuffy v. Yardi Sys., Inc., No. 2:23-cv-01391 (W.D. Wash.).

gAs of June, 2025, the case was ongoing.

|

Topic |

Status |

Summary of advisory opinion |

|

Name-only matching procedures |

Withdrawn |

In November 2021, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) published an advisory opinion stating that name-only matching procedures—those based solely on the similarity of first and last names—do not meet the Fair Credit Reporting Act’s (FCRA) requirement to use reasonable procedures to ensure maximum possible accuracy when generating consumer reports.a The opinion notes that relying solely on a person’s first and last name could lead to inaccurate information being included in a consumer report. CFPB withdrew this guidance on May 12, 2025. |

|

Facially false data |

Active |

In October 2022, CFPB published an advisory opinion stating that consumer reporting agencies must implement reasonable procedures to detect and prevent the inclusion of facially false (logically inconsistent) data when generating consumer reports.b Examples include reporting a delinquency that predates the account opening or an account closure date that predates the consumer’s listed date of birth. |

|

Report accuracy |

Withdrawn |

In January 2024, CFPB issued an advisory opinion on background reports.c The opinion clarifies that consumer reporting agencies must implement reasonable procedures to ensure that reports do not include information that is duplicative, expunged, sealed, or otherwise restricted from public access. Each adverse item is also subject to its own reporting period. For example, a criminal charge that did not result in a conviction generally cannot be reported more than 7 years after the date of the charge. CFPB withdrew this guidance on May 12, 2025. |

|

File disclosures |

Withdrawn |

In January 2024, CFPB issued an advisory opinion on file disclosures.d The opinion underscores that under FCRA, consumers have the right to request and obtain all information in their consumer file at the time of request. The opinion explains how consumer reporting agencies must fulfill this request even if the consumer does not explicitly ask for a “complete file” and also must disclose the sources used to generate the report. CFPB withdrew this guidance on May 12, 2025. |

Source: GAO analysis of CFPB advisory opinions. | GAO‑25‑107196

CFPB issues advisory opinions to publicly address uncertainty about its existing regulations and provide guidance to regulated entities.

aConsumer Financial Protection Bureau, Fair Credit Reporting: Name-Only Matching Procedures (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 4, 2021).

bConsumer Financial Protection Bureau, Fair Credit Reporting: Facially False Data (Washington D.C.: Oct. 20, 2022).

cConsumer Financial Protection Bureau, Fair Credit Reporting; Background Screening (Washington D.C.: Jan. 11, 2024).

dConsumer Financial Protection Bureau, Fair Credit Reporting: File Disclosures (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 11, 2024).

GAO Contact

Alicia Puente Cackley, CackleyA@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Cory Marzullo (Assistant Director), Brandon Jones (Analyst in Charge), Daniel Horowitz, Lydie Loth, Marc Molino, Barbara Roesmann, Jessica Sandler, Tristan Shaughnessy, Norma-Jean Simon, and Sean Worobec made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Artificial intelligence, in general, refers to computer systems that can solve problems and perform tasks that have traditionally required human intelligence and that continually get better at their assigned tasks. The White House, Office of Science and Technology Policy, American Artificial Intelligence Initiative: Year One Annual Report (Washington, D.C.: February 2020). Machine learning, a type of artificial intelligence, uses algorithms to identify patterns in information.

[2]We use “tenant screening” throughout this report to refer to tools that seek to assess the suitability of prospective renters for rental housing. In all other contexts, we use “renter” rather than “tenant.” We use “owners” to refer to individuals who own rental property, as well as those individuals or entities—such as property managers—acting on their behalf.

[3]Several resources we reviewed rely on the disparate-impact theory of liability, mentioned below. Under Executive Order 14281, executive departments and agencies are tasked with—among other things—repealing or amending rules and regulations to the extent they contemplate disparate-impact liability and evaluating and taking appropriate action regarding pending investigations and proceedings and existing consent judgments and permanent injunctions relying on theories of disparate-impact liability. Executive Order 14281: Restoring Equality of Opportunity and Meritocracy, 90 Fed. Reg. 17537 (Apr. 28, 2025). As of May 8, 2025, the rules, regulations, and legal actions mentioned below have not been amended or repealed, though they may be affected to the extent they rely on the disparate-impact theory of liability. On February 9, 2025, the National Treasury Employees Union and others filed a lawsuit in the District Court for the District of Columbia alleging that the actions of the Acting Director of CFPB including regarding staffing and enforcement work violated the Administrative Procedure Act and were unconstitutional because they violated the Congressional mandate in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act for CFPB to perform its statutory functions. Nat’l Treasury Emp. Union, et al. v. Vought, 1:25-cv-00381 (D.D.C. filed Feb. 9, 2025). As of May 2025, the litigation is active and continues in both the District Court for the District of Columbia and the DC Circuit Court of Appeals.

[4]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[5]Fair Housing Act, Pub. L. No. 90-284, 82 Stat. 73, 81–89, §§ 801–819 (1968), as amended (codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601–3619). Protected characteristics under the act include race, color, religion, national origin, sex, disability, and familial status. HUD also provides funding to Fair Housing Initiative Program organizations to assist individuals who believe they have been victims of housing discrimination. These organizations also conduct preliminary investigations of discriminatory claims, including sending “testers” to properties suspected of practicing housing discrimination. State and local governments may enforce their own statutes and ordinances that are substantially equivalent to the Fair Housing Act.

[6]If an election is made, HUD refers the case to DOJ, which then files a complaint in federal court. If no election is made, HUD will litigate the case before its administrative law judges.

[7]15 U.S.C. §§ 1681-1681. CFPB also has supervisory authority over covered persons, including certain consumer reporting agencies, with respect to compliance with FCRA. 12 U.S.C §§ 5511(c)(4); 5481(6), (14), (15)(A)(ix); 5514–5516.

[8]In 2023, FTC and CFPB jointly issued a request for information seeking public input on the use of algorithms in tenant screening. The request also asked about the potential for discriminatory outcomes related to the use of criminal history and eviction records in the rental housing process. Agency officials told us they issued the request for general information-gathering purposes.

[9]15 U.S.C. § 45.

[10]As of May, 2025, approximately 970,000 households were living in public housing. The Housing Choice Voucher program subsidizes the rents of more than 2.3 million households. We did not include HUD’s Office of Multifamily Housing in our review because it is not directly responsible for overseeing the use of the selected proptech tools in subsidized properties, according to officials.

[11]The information is typically obtained from sources such as potential renters, third-party vendors, courthouses, and other consumer reporting agencies.

[12]Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Consumer Snapshot: Tenant Background Checks (Washington D.C.: November 2022). CFPB’s reported data were the most current data available as of May 2025.

[13]GAO, Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: Benefits and Challenges of Technologies to Augment Patient Care, GAO‑21‑7SP (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 30, 2020).

[14]There are two principal theories of liability for discrimination: disparate treatment and disparate impact. Disparate impact can occur when a facially neutral policy or practice may be unlawfully discriminatory because it has a disproportionately negative impact on members of a protected class without a legitimate business need or where that need could be achieved as well through less discriminatory means. Disparate impact may occur when an algorithm uses a variable that does not directly refer to a protected class but still leads to disparate outcomes for certain groups. In 2015, the Supreme Court upheld the application of disparate impact under the Fair Housing Act in Tex. Dep’t of Hous. & Cmty. Aff. v. The Inclusive Cmties. Project, Inc., 576 U.S. 519 (2015). In April 2025, the President issued an Executive Order establishing a policy to eliminate the use of disparate impact liability in all contexts to the maximum degree possible. The Executive Order directs all federal agencies to deprioritize enforcement of statutes and regulations that include disparate impact liability. Executive Order 14281: Restoring Equity of Opportunity and Meritocracy, 90 Fed. Reg. 17537 (Apr. 28, 2025).

[15]In 2024, HUD supplemented public data with six private-sector data sources as part of its methodology to determine fair market rents. These sources were: (1) Apartment List Rent Estimate; (2) CoStar Group average effective rent; (3) CoreLogic’s single-family, combined 3-bedroom median rent index; (4) Moody’s Analytics average gross revenue per unit; (5) RealPage’s average effective rent per unit; and (6) Zillow’s Observed Rent Index.

[16]Calder-Wang, Sophie and Gi Heung Kim, Algorithmic Pricing in Multifamily Rentals: Efficiency Gains or Price Coordination? (Aug. 16, 2024).

[17]The study also found that owners that used rent-setting software decreased rents to increase occupancy rates during economic downturns.

[18]We previously reported that accuracy in facial recognition has been found to be variable and demographically biased. See GAO, Biometric Identification Technologies: Considerations to Address Information Gaps and Other Stakeholder Concerns, GAO‑24‑106293 (Washington, D.C: Apr. 22, 2024).

[19]For additional information on the accuracy of facial recognition technology across demographics, see GAO, Facial Recognition Technology: Privacy and Accuracy Issues Related to Commercial Uses, GAO‑20‑522 (Washington, D.C.: July 13, 2020).

[20]We limited our discussion of agency actions to finalized legal judgments and executed compliance agreements. Appendix II includes information on currently active legal actions initiated by HUD, DOJ, and FTC related to the proptech tools we reviewed. Executive Order 14281 requires agencies to evaluate existing consent judgments and permanent injunctions that rely on theories of disparate impact liability and to take appropriate actions with respect to matters consistent with the order. The order eliminates the use of disparate impact liability in all contexts to the maximum degree possible. The agencies have 90 days from April 23, 2025 to complete the review. The agencies may make decisions that impact the cases listed in this report. As of May 6, 2025, the agencies have not made public notification of any changes to these closed cases based on Executive Order 14281.

[21]Fed. Trade Comm’n et al. v. Roomster, 1:22-cv-07389 (S.D.N.Y.). Separately, another defendant was ordered to stop selling consumer reviews or endorsements and fined.

[22]Facebook, a social media platform owned by Meta, displays advertisements to users, including those for rental housing opportunities.

[23]United States v. Meta Platforms, Inc, f/k/a Facebook, Inc., No. 1:22-cv-05187 (S.D.N.Y).

[24]Department of Housing and Urban Development, Guidance on Application of the Fair Housing Act to the Advertising of Housing, Credit, and Other Real Estate-Related Transactions through Digital Platforms (Washington, D.C.: April 2024).

[25]Department of Housing and Urban Development, Guidance on the Application of the Fair Housing Act to the Screening of Applicants for Rental Housing (Washington, D.C.: April 2024). HUD issued the guidance in response to Executive Order 14110, which required HUD to issue guidance on the use of artificial intelligence in housing decisions. Executive Order 14110 was rescinded on January 20, 2025, by Executive Order 14148.

[26]The White House, Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs and Preferencing, Executive Order 14151 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 20, 2025).

[27]United States v. AppFolio, Inc., No. 1:20-cv-03563 (D.D.C.).

[28]Fed. Trade Comm’n v. TransUnion Rental Screening Sol., No. 1:23-cv-02659 (D. Colo.). See also, In re TransUnion, 2023-CFPB-0011 (Oct. 12, 2023).

[29]Fed. Trade Comm’n v. Instant Checkmate, LLC et al., No. 3:23-cv-01674 (S.D. Cal.). The five affiliated companies are Instant Checkmate, Truthfinder, Intelicare Direct, The Control Group Media Company, and PubRec. FTC alleged in its complaint that all five companies operated as a common enterprise while engaging in the alleged unlawful acts and practices.

[30]Louis et al v. SafeRent Sol., LLC and Metro. Mgmt. Grp., No. 1:22-cv-10800 (D. Mass.) DOJ is authorized under 28 U.S.C. §§ 516 and 517 to file statements of interest in federal and state court cases between private parties in which the United States has an interest.

[31]In July 2023, the court denied the defendants’ motions to dismiss the Fair Housing Act claim and permitted the case to proceed against SafeRent and the other defendants. The court dismissed certain counts against SafeRent that were unrelated to the Fair Housing Act.

[32]Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Public and Indian Housing, Letter to Public Housing Agencies (Sep. 22, 2023). As stated previously, as of May 2025, approximately 970,000 households were living in public housing. As administrator of the public housing program, HUD is responsible for providing guidance to PHAs on operations, including use of surveillance technology.

[35]The industry associations are the Consumer Data Industry Association, National Apartments Association, National Multifamily Housing Council, and Security Industry Association. The advocacy organizations are the National Fair Housing Alliance, National Low Income Housing Coalition, American Civil Liberties Union, Center for Democracy and Technology, and National Consumer Law Center.

[36]The two Fair Housing Initiative Program organizations are Brooklyn Legal Service and the Fair Housing Justice Center.

[37]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[38]We did not include HUD’s Office of Multifamily Housing in our review because it is not directly responsible for overseeing the use of the selected proptech tools in subsidized properties, according to officials.