ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Use and Oversight in Financial Services

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Michael E. Clements, clementsm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107197, a report to congressional committees

Use and Oversight in Financial Services

Why GAO Did This Study

AI generally entails machines doing tasks previously thought to require human intelligence. Its use in financial services has increased in recent years, driven by more advanced algorithms, increased data availability, and other factors. Federal financial regulators have also begun using AI tools to oversee regulated entities and financial markets.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act includes a provision for GAO to annually report on financial services regulations. This report reviews (1) the benefits and risks of AI use in financial services, (2) federal financial regulators’ oversight of AI use in financial services, and (3) the regulators’ AI use in their supervisory and market oversight activities. GAO reviewed studies by federal agencies, academics, industry, and other groups; examined documentation and guidance from federal financial regulators; and interviewed regulators, consumer and industry groups, researchers, financial institutions, and technology providers.

What GAO Recommends

GAO reiterates its 2015 recommendation that Congress consider granting NCUA authority to examine technology service providers for credit unions. GAO also recommends that NCUA update its model risk management guidance to encompass a broader variety of models used by credit unions. NCUA generally agreed with the recommendation.

What GAO Found

Financial institutions’ use of artificial intelligence (AI) presents both benefits and risks. AI is being applied in areas such as automated trading, credit decisions, and customer service (see figure). Benefits can include improved efficiency, reduced costs, and enhanced customer experience—such as more affordable personalized investment advice. However, AI also poses risks, including potentially biased lending decisions, data quality issues, privacy concerns, and new cybersecurity threats.

Federal financial regulators primarily oversee AI using existing laws, regulations, guidance, and risk-based examinations. However, some regulators have issued AI-specific guidance, such as on AI use in lending, or conducted AI-focused examinations. Regulators told GAO they continue to assess AI risks and may refine guidance and update regulations to address emerging vulnerabilities.

Unlike the other banking regulators, the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) does not have two key tools that could aid its oversight of credit unions’ AI use. First, its model risk management guidance is limited in scope and detail and does not provide its staff or credit unions with sufficient detail on how credit unions should manage model risks, including AI models. Developing guidance that is more detailed and covers more models would strengthen NCUA’s ability to address credit unions’ AI-related risks.

Second, NCUA lacks the authority to examine technology service providers, despite credit unions’ increasing reliance on them for AI-driven services. GAO previously recommended that Congress consider granting NCUA this authority (GAO-15-509), but as of February 2025, Congress had not yet done so. Such authority would enhance NCUA’s ability to monitor and mitigate third-party risks, including those associated with AI-service providers.

The federal financial regulators are increasingly integrating AI into their general agency operations and supervisory and market oversight activities, with usage varying across agencies. The regulators use AI to identify risks, support research, and detect potential legal violations, reporting errors, or outliers. Most regulators told GAO that AI outputs inform staff decisions but are not used as sole decision-making sources.

Abbreviations

|

AI |

artificial intelligence |

|

CFPB |

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau |

|

CFTC |

Commodity Futures Trading Commission |

|

FDIC |

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

|

Federal Reserve |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

|

FINRA |

Financial Industry Regulatory Authority |

|

FSOC |

Financial Stability Oversight Council |

|

NCUA |

National Credit Union Administration |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

OCC |

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

SEC |

Securities and Exchange Commission |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 19, 2025

Congressional Committees

Since the launch of the artificial intelligence (AI) application ChatGPT in November 2022, interest has grown in AI’s potential impact on various industries, including financial services.[1] AI broadly refers to computer systems that are capable of solving problems and performing tasks that traditionally required human intelligence, with the ability to continually improve at these tasks.[2] Advances in algorithms, the availability of larger volumes of data, and improvements in data storage and processing have led to increased use of AI, including in financial services. In addition, federal financial regulators have begun using AI tools to oversee regulated entities and financial markets.

In light of these developments, Members of Congress and other stakeholders have raised questions about the use of AI by financial service institutions and federal financial regulators. Section 1573(a) of the Department of Defense and Full-Year Continuing Appropriations Act, 2011, amended the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act to include a provision for us to annually review financial services regulations, including the impact of regulation on the financial marketplace.[3] This report examines (1) the potential benefits and risks of AI use in financial services, (2) federal financial regulators’ oversight of AI use in the financial services industry, and (3) federal financial regulators’ use of AI in their supervisory and market oversight activities.

For the first objective, we analyzed reports and studies from federal agencies, industry groups, international nongovernment organizations, and research and academic institutes.[4] We also interviewed representatives of seven federal financial regulators; six industry groups representing banks, credit unions, financial technology companies, and securities and derivatives market participants; three consumer and investor advocacy organizations; five research and consulting groups; four depository institutions; and three technology providers.[5] We selected interviewees that could provide perspectives on AI in banking or in securities or derivatives markets. The information gathered from these interviews cannot be generalized to all companies that develop or use AI in financial services.

For the second objective, we reviewed laws, regulations, guidance, and other agency documentation relevant to the oversight of financial institutions’ use of AI.[6] We assessed model risk management guidance issued by the prudential regulators—the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve), Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)—for general alignment with leading practices in the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) AI Risk Management Framework. In doing so, we focused on the framework’s recommended practices for overseeing regulated entities’ design, development, deployment, and monitoring of AI systems.[7] In addition, we assessed NCUA’s model risk management guidance against the strategic goals and objectives in its 2022–2026 strategic plan. We also reviewed documentation from the federal financial regulators on AI-related training efforts, AI-related committees, and other initiatives.

For the third objective, we reviewed laws, executive orders, agency reports, strategic plans, policies and procedures, and other agency documents related to the federal financial regulators’ current and planned uses of AI.[8] We also reviewed federal financial regulators’ inventories of AI uses and interviewed officials from the seven federal financial regulators regarding use of AI in supervisory activities. For more detailed information about our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Definitions of AI

The scientific community and industry have yet to agree on a common definition for AI, and definitions vary within the government.[9] However, the definitions generally entail machines doing tasks previously thought to require human intelligence. AI technologies and uses vary substantially, and there is not always a clear difference between AI and more traditional quantitative modeling. For instance, some regression analysis techniques that have been used for decades could arguably be considered a form of AI.[10]

Two terms are particularly relevant for describing AI used in the financial services industry:

· Machine learning programs automatically improve their performance at a task through experience, without relying on explicit rules-based programming.[11] Machine learning is the basis for natural-language processing and computer vision, which help machines understand language and images, respectively. Examples of natural language processing include translation apps and personal assistants on smart phones. Computer vision includes algorithms and techniques to classify or understand image or video content.

· Generative AI is a type of machine learning that can create content such as text, images, audio, or video when prompted by a user. It differs from other AI systems in its ability to create novel content, its reliance on vast amounts of training data, and the greater size and complexity of its models. Content created through generative AI is based on data, often text and images sourced from the internet at large.[12]

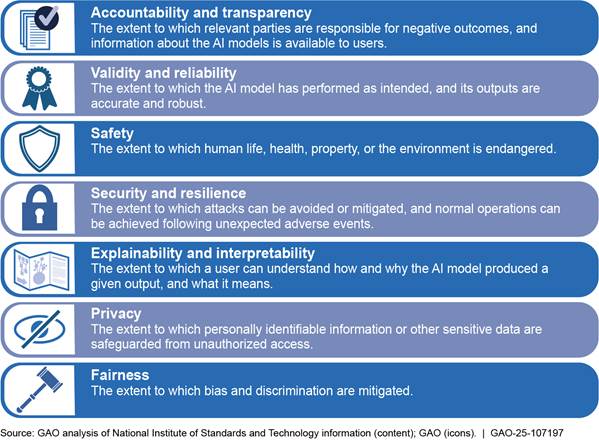

Characteristics of Trustworthy AI

NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework describes leading practices for organizations that design, develop, deploy, or use AI systems.[13] It also identifies key characteristics intended to help manage the risks of AI while promoting trustworthy and responsible AI development and use (see fig. 1).

According to NIST, addressing these characteristics individually will not ensure AI system trustworthiness. Trade-offs are usually involved, as not all characteristics apply equally to every context and some will be more or less important depending on the situation. When managing AI risks, organizations can face difficult decisions in balancing these characteristics. For example, organizations may need to balance privacy against predictive accuracy or fairness in certain scenarios. Approaches that enhance trustworthiness can reduce risks, according to NIST, and neglecting these characteristics can increase the likelihood and magnitude of negative consequences.

Federal Oversight of Financial Institutions

Multiple federal regulators oversee financial institutions based on their individual charters or activities. Table 1 explains the basic oversight functions of the federal regulators within the scope of this review.

|

Regulator |

Responsibilities |

Supervised entities and oversight function |

|

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System |

Safety and soundness, consumer financial protection, and financial stability |

Supervises state-chartered banks that opt to be members of the Federal Reserve System; bank and thrift holding companies and the nondepository institution subsidiaries of these institutions; and nonbank financial companies and financial market utilities designated as systemically important by the Financial Stability Oversight Council for consolidated supervision and enhanced prudential standards. Supervises state-licensed branches and agencies of foreign banks and regulates the U.S. nonbanking activities of foreign banking organizations. |

|

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation |

Safety and soundness, consumer financial protection, and financial stability |

Insures the deposits of all banks and thrifts approved for federal deposit insurance; supervises insured state-chartered banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System, as well as insured state savings associations and insured state-chartered branches of foreign banks; resolves all failed insured banks and thrifts; and may be appointed to resolve large bank holding companies and nonbank financial companies supervised by the Federal Reserve. Has backup supervisory responsibility for all federally insured depository institutions. |

|

National Credit Union Administration |

Safety and soundness and consumer financial protection |

Charters and supervises federally chartered credit unions and insures savings in federal and most state-chartered credit unions. |

|

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency |

Safety and soundness and consumer financial protection |

Charters and supervises national banks, federal savings associations, and federal branches and agencies of foreign banks. |

|

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau |

Consumer financial protection |

Regulates the offering and provision of consumer financial products or services under the federal consumer financial laws. Has exclusive examination authority as well as primary enforcement authority for the federal consumer financial laws for insured depository institutions with over $10 billion in assets and their affiliates. Supervises certain nondepository financial entities and their service providers and enforces the federal consumer financial laws. Enforces prohibitions on unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices and other requirements of the federal consumer financial laws for persons under its jurisdiction. |

|

Commodity Futures Trading Commission |

Derivatives industry |

Regulates derivatives markets and seeks to protect market users and the public from fraud, manipulation, abusive practices, and systemic risk related to derivatives subject to the Commodity Exchange Act. Also seeks to foster open, competitive, and financially sound futures markets. |

|

Securities and Exchange Commission |

Securities industry |

Regulates securities markets, including offers and sales of securities and regulation of securities activities of certain participants such as securities exchanges; broker-dealers; investment companies; clearing agencies; transfer agents; and certain investment advisers and municipal advisors. Oversees the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). FINRA seeks to promote investor protection and market integrity by developing rules, examining securities firms for compliance, and taking actions against violators. Approves self-regulatory organizations’ rules that govern the conduct of their members. |

Source: GAO analysis of laws and agency documents. | GAO‑25‑107197

AI Can Provide Benefits to Consumers, Institutions, and Financial Markets but Also Poses Risks

AI has the potential to bring numerous benefits to financial services, including lower costs, enhanced efficiency, and improved accuracy and customer convenience. However, AI use also poses risks, such as the potential for biased lending decisions and disruptions to financial institutions and markets.

AI Has a Variety of Uses in the Financial Services Industry

Financial institutions are using AI for many activities, according to our review of documents from federal financial regulators, financial institutions, industry and advocacy groups, and international and research organizations, as well as our interviews with these stakeholders. These activities include automated trading, countering threats and illicit finance, credit decisions, customer service, investment decisions, and risk management (see table 2).

|

Function |

Use |

Description of how artificial intelligence (AI) may be used |

|

Automated trading |

Order placement and execution |

Assess how an order for securities or derivatives should be placed to optimize execution. Execute large trade orders in a dynamic way to minimize the impact on price. |

|

Countering threats and illicit finance |

Assessing customer risk Detecting illicit activity Cybersecurity |

Identify fake IDs, recognize different photos of the same person, and screen clients against sanctions and other lists. Analyze transaction data (such as bank account and credit card data) and unstructured data (such as email, text, and audio data) to detect evidence of possible money laundering, terrorist financing, bribery, tax evasion, insider trading, market manipulation, and other fraudulent or illegal activities. Detect and mitigate cyber threats through real-time investigation of potential attacks, flagging and blocking of new ransomware, and identification of compromised accounts and files. |

|

Credit decisions |

Analyzing creditworthiness |

Analyze data from sources such as credit reports, financial statements, and transaction history to predict an applicant’s creditworthiness. Assess creditworthiness of applicants without a credit score by analyzing information not contained in a traditional credit report, such as rent and utility payments (also known as alternative data). |

|

Customer service |

Chatbots Automated response routing |

Provide customer service by simulating human conversation through text and voice commands. Respond to basic customer questions regarding bank account balances and transaction history, investment portfolio holdings, address changes, and password resets. Accept and process trade orders within certain thresholds or initiate account openings. Process and triage customer calls and screen and classify incoming customer emails according to key features, such as the email address or subject line. Respond to emails containing common or routine inquiries. |

|

Investment decisions |

Investment strategies Advisory services |

Analyze large amounts of data, including from nontraditional sources like social media and satellite imagery, to predict price movement of assets, such as stocks. Provide financial advice to individual investors by analyzing their assets, spending patterns, debt balances, internet activity, and prior communications (such as emails and chats). |

|

Risk management |

Credit risk Liquidity risk |

Analyze loan portfolio and market data to predict borrower defaults and inform decisions about when to write off debt. Analyze substantial historical data along with current market data to identify trends, note anomalies, and optimize liquidity and cash management. |

Source: GAO analysis of information from federal agencies, financial institutions, industry and advocacy groups, and international and research organizations. | GAO‑25‑107197

|

Explainability Explainability refers to the ability to understand how and why an AI system produces decisions, predictions, or recommendations. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the banking and credit union regulators, insufficient explainability in AI models can pose several challenges. It may inhibit a financial institution’s understanding of a model’s conceptual soundness and reliability, inhibit independent review and audit, and make compliance with laws and regulations more difficult. Source: GAO analysis of federal agency documents. | GAO‑25‑107197 |

Most of these AI applications use machine learning, which makes predictions, identifies patterns, or automates processes. In more limited cases, financial institutions are using generative AI, generally to enhance employee productivity. For example, one regional financial institution is piloting an internal generative AI chatbot that answers employees’ questions about policies and procedures. Additionally, some banks are training generative AI models on customer service call center conversations to enhance customer support, according to one banking association.[14] These models can provide recommendations to help employees address customer issues, such as replacing a debit card. One large financial institution is piloting generative AI tools to assist employees with writing code, summarizing customer interactions, searching legal documents, and conducting market research.

Financial institution representatives told us they have been more cautious about adopting AI for activities where a high degree of reliability or explainability is important or where they are unsure how regulations would apply to a particular use of AI. For example, the greater complexity of generative AI models makes explainability more challenging and, as discussed below, can produce inaccurate outputs. According to the Department of the Treasury, financial institutions currently limit generative AI use to activities where the institution deems lower levels of explainability to be sufficient.[15]

AI May Improve Consumer Products and Services and May Enhance Financial Institutions’ Operations

AI may be faster, more efficient, and more accurate than prior methods for performing various tasks, yielding benefits to consumers, investors, financial institutions, and financial markets, according to reports we reviewed and stakeholders we interviewed.

Potential Benefits for Consumers and Investors

Lower cost. AI can enable financial institutions to provide certain products and services at a lower cost. For example, robo-advisers that use AI to automate investment management may provide investment advice at lower fees and require smaller account minimums compared with traditional advisory services.[16] AI could also make lower-cost products and services more accessible. For example, AI-powered automation of credit underwriting services enables credit unions to deliver faster credit decisions, according to one AI provider. This feature allows its customers to avoid higher-cost lending options when funds are needed quickly.

Greater financial inclusion. AI may have the potential to expand financial services to customers typically lacking access. In lending, AI may benefit customers with thin credit files or no credit record at all.[17] Further, representatives of one AI provider told us that credit unions that implemented its AI model reported a 40 percent increase in credit approvals for women and people of color. In addition, AI could introduce investment management to populations not previously using these services.[18]

Greater convenience. AI could enhance the convenience and quality of customer service. For example, chatbots can provide immediate customer support any time of day, and AI can help them better understand and respond to customer questions. In addition, one credit union reported using an AI system to personalize its customer service by recommending a member’s frequent tasks, such as transferring funds, when they interact with the chatbot.

Potential Benefits for Financial Institutions and Financial Markets

Increased security. AI could improve the security of institutions and markets through better detection of cyber threats and illicit finance (e.g., fraud, money laundering, and insider trading). For example, AI can help combat synthetic identity fraud by identifying cases that human analysts cannot easily detect.[19] AI may also reduce false positives, which constitute the vast majority of money laundering and terrorist financing alerts, allowing institutions to focus on genuinely suspicious cases, according to the International Monetary Fund.[20]

Higher profitability. Financial institutions may realize higher profits if AI enhances revenue generation or reduces costs. AI can potentially help improve predictive power and increase profitability for financial institutions.[21] For example, according to one study, chatbots saved approximately $0.70 per customer interaction compared with human agents.[22] The aggregate savings can be substantial—for example, one large financial institution reported that its AI chatbot had had over 2 billion customer interactions.[23] In addition, one AI provider told us its AI model reduced the time and resources needed for financial institutions to make credit decisions by up to 67 percent. However, the cost of developing or acquiring AI could be high and may be prohibitive for smaller financial institutions, according to representatives from trade associations representing banks and credit unions.

Reduced market impact. Capital markets could see less price volatility from large trades when AI is used to place and execute orders. According to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, AI can minimize the market impact of large trades by optimizing size, duration, and order size dynamically, based on market conditions.[24]

Improved compliance and risk management. Financial institutions and markets could benefit if AI enhances risk management and compliance with laws and regulations. According to the International Monetary Fund, AI has improved compliance by leveraging broad sets of data in real time and automating compliance decisions.[25] Improved compliance could lead to safer securities markets, according to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).[26] Additionally, AI can monitor thousands of risk factors daily and test portfolio performance under thousands of economic scenarios, further enhancing financial institutions’ risk management.[27]

AI Presents Risks for Consumers, Financial Institutions, and Markets

AI has the potential to amplify risks inherent in financial activities, and these risks can affect consumers, investors, financial institutions, and financial markets.[28] Factors that can increase risk include complex and dynamic AI models, poor-quality data, and reliance on third parties. In addition, AI may introduce new vulnerabilities, such as hallucinations and novel cyber threats.[29]

Consumer and Investor Risks

Fair lending risk. Bias in credit decisions is a risk inherent in lending, and AI models can perpetuate or increase this risk, leading to credit denials or higher-priced credit for borrowers, including those in protected classes.[30] For example, one researcher testified that some AI models could infer loan applicants’ race or gender from application data or create complex interactions between variables that could result in disproportionately negative effects on certain groups.[31] Further, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) has warned that as AI models grow more complex, identifying and correcting biases can become increasingly difficult.[32] The use of AI to market credit products also carries fair lending risks. According to one consumer advocate, AI could steer borrowers, including those in protected classes, toward inferior or costlier credit products.

Conflict of interest risk. AI models used in investment advisory services could increase the potential for conflicts of interest between advisers or brokers and their clients. For example, AI models could optimize higher profits for advisers, potentially at investors’ expense.[33] The complexity of AI may obscure such conflicts. For example, one consumer advocate we spoke with noted that it may not be apparent when AI is providing conflicted advice that is not in the client’s best interest.

Privacy risk. AI can expose consumers to new privacy risks. For example, according to reports we reviewed, certain machine learning and generative AI models may leak sensitive data directly or by inference, including by deducing identities from anonymized data.[34] To safeguard against such privacy risks, one financial institution we spoke with restricts its employees’ access to publicly available generative AI applications. Further, AI enables financial institutions to collect and analyze increasing amounts of sensitive consumer data, increasing privacy risks. For example, according to FINRA, AI use in the securities industry may involve collecting, analyzing, and sharing personally identifiable information and biometrics, customer website or app usage data, geospatial location, social media activity, and written, voice, and video communications.[35]

Financial institutions also may rely on third parties to develop AI models or to store data, which could heighten privacy risk. For example, cloud computing used in AI exacerbates privacy risks when financial institutions lack the expertise to conduct effective due diligence on cloud services.[36]

False or misleading information risk. AI models may produce inaccurate information about financial products or services, potentially causing harm to consumers or investors. According to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), AI-based customer interactions may lead to unintended biases and deceptive or misleading communications.[37] The prudential regulators and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) have noted that AI can create or heighten risks of unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices.[38] Further, generative AI can produce outputs that are false but convincing, known as hallucinations, which can be especially problematic for consumer-facing applications.[39]

Financial Institution Risks

Operational and cybersecurity risk. AI could lead to technical breakdowns that disrupt the operations of financial institutions. According to the prudential regulators, the use of AI could result in failures related to internal processes, controls, or information technology, as well as risks associated with the use of third parties and models, all of which could affect a financial institution’s safety and soundness.[40] AI may also increase the scope for cyber threats and introduce new vulnerabilities. Novel threats could allow attackers to evade detection and prompt AI to make wrong decisions or extract sensitive information.[41]

Model risk. AI models may underperform and result in financial losses or reputational harm to a financial institution. The function and outputs of AI can be negatively affected by data quality issues, such as incomplete, erroneous, unsuitable, or outdated data; poorly labelled data; data reflecting underlying human prejudices; or data used in the wrong context. According to the prudential regulators and CFPB, AI may perpetuate or even amplify bias or inaccuracies inherent in the training data, or make incorrect predictions if that data set is incomplete or nonrepresentative.[42] In addition, according to reports we reviewed, some AI models may struggle to adapt to new conditions.[43] For example, these models may produce inaccurate results when encountering different market conditions or changing customer behavior.

Challenges in assessing the quality of AI inputs and outputs could heighten model risk. Financial institutions may find it difficult to evaluate the data sources used to train AI models, especially if the sources are opaque or unavailable, according to the Financial Stability Board.[44] Reports we reviewed indicate that testing and validating certain machine learning models may be more challenging than with traditional models due to their dynamic nature.[45] Specifically, AI models that learn continuously from live data can lead to shifts in underlying data, variable relationships, or statistical characteristics, potentially leading to model underperformance or inaccurate outputs. According to FSOC, expert analysis may be needed to evaluate the accuracy of generative AI output.[46]

According to representatives of one large bank we spoke with, hallucinations are a key reason banks avoid using generative AI for activities that warrant a high degree of accuracy, such as credit underwriting or risk management. However, they noted that techniques are being developed to limit hallucinations.[47]

Compliance risk. AI may produce results that violate or inhibit compliance with consumer or investor protection laws or that are inconsistent with safe and sound banking practices or market conduct law. For example, some AI models’ limited explainability may inhibit financial institutions from complying with fair lending laws if they cannot provide specific reasons for denying an application for credit or taking other adverse actions.

In addition, under certain circumstances, AI risk factors such as explainability challenges and poor data quality can introduce risks to safety and soundness, according to FSOC.[48] Financial institutions that use AI face increased risks if they do not adhere to appropriate operational and cybersecurity standards. Further, AI used in trading applications may contribute to inappropriate trading behavior or market disruptions, according to CFTC.[49] One study found that an AI model identified market manipulation as an optimal investment strategy without being explicitly programmed to do so, illustrating how AI can inadvertently violate the law.[50]

Financial Market Risks

Concentration risk. Financial instability could arise from a reliance on a concentrated group of third-party AI service providers (e.g., data providers, cloud providers, and technology firms). This concentration could increase the financial system’s vulnerability to single points of failure.[51] While the risk of concentration is not unique to AI, the technology’s need for significant data and computational power contributes to this concern. The Financial Stability Board has noted that highly concentrated service provider markets exist across important aspects of the AI supply chain, including in hardware, infrastructure, and data aggregation.[52]

Herding risk. AI could lead to herding behavior—where individual actors make similar decisions—resulting in systemic risk to financial markets. While this risk is not unique to AI, such behavior could arise from a concentration of third-party AI providers or homogeneity in data used to train models, and the effect depends on the sector where the behavior takes place, according to reports we reviewed.[53] For example, herding in capital markets could amplify market volatility or trigger crashes. In addition, herding in lending or risk management could amplify economic booms and busts. However, whether AI could lead to herding behavior is subject to debate, and some market participants argue that AI models, datasets, and uses will be sufficiently diverse to mitigate this risk, according to the International Organization of Securities Commissions.[54]

Regulators Use Existing Frameworks to Oversee AI, but NCUA’s Key AI Oversight Tools Are Limited

Regulators Generally Use Existing Regulatory and Supervisory Frameworks

Officials from federal financial regulators noted that existing federal financial laws and regulations generally apply to financial service activities regardless of whether AI is used.[55] For example, the Congressional Research Service explained that lending laws apply both to lenders making decisions with pencil and paper and to those using AI models.[56] Appendix II presents selected laws and regulations that are not specific to AI but may help address AI-related risks.

Similarly, financial regulator officials told us that existing guidance generally applies to financial institution activities regardless of AI use. For example, officials from FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC identified supervisory guidance for managing model risk and third-party risk (discussed below) as relevant to AI use, depending on the facts and circumstances.[57] While these guidance documents may not explicitly mention AI, their principles can help financial institutions manage key AI risks and ensure AI systems operate as intended.

Officials from most of the financial regulators we spoke with told us they believe existing statutory authorities are generally sufficient to supervise regulated entities’ AI use at this time. NCUA officials cited their agency’s lack of third-party oversight authority as a reason they believe existing authorities are not sufficient, as discussed in more detail below.

Representatives from several industry groups and financial institutions generally expressed similar views. However, several of these representatives also noted opportunities to clarify AI-related guidance. For example, some said regulators could clarify how guidance applies to AI technologies posing different levels of risk. Some also suggested that regulators clarify their expectations for explainability and adverse action notice requirements.[58] In addition, some said that financial service companies’ uncertainty about how regulations could apply makes them take a cautious approach to AI adoption.

The Financial Stability Board reported that existing frameworks address many AI-related vulnerabilities, but future developments could introduce new ones that are not adequately addressed by current regulatory and supervisory frameworks.[59] Some of the regulators made similar comments and are considering updates to regulations and guidance.[60] For example, SEC officials stated that they are assessing if existing regulations and guidance adequately address AI-related risks. CFTC staff also reported that AI’s rapid development could necessitate new or supplemental guidance or regulations.[61] Federal Reserve officials stated that they are considering whether additional policy steps or clarification for regulated entities is needed.

Federal financial regulators also told us they rely on their standard risk-based examination processes to assess if financial institutions’ AI use is consistent with applicable laws and regulations.

· Prudential regulators. FDIC, Federal Reserve, OCC, and NCUA officials told us that if AI is determined to be relevant through risk-based planning and prioritization processes, it would typically be reviewed as part of broader examinations of safety and soundness, information technology, or compliance with applicable laws and regulations. OCC officials added that examinations depend on the extent of a financial institution’s AI use and its risk management practices.

· CFPB. In June 2024, CFPB officials said their examinations focus on compliance and enforcement of federal consumer financial laws, regardless of whether AI is used. They said they typically examine regulated entities by product lines, policies, or practices, which may include reviews of institutions’ AI use.

· Financial market regulators. SEC and CFTC officials said their examinations focus on ensuring regulated entities comply with applicable statutory and regulatory requirements, regardless of AI use.[62] SEC officials added that AI can either be the focus of an examination or part of a broader examination of firm practices. CFTC officials told us that they would examine their regulated entities’ AI use for consistency with regulatory requirements.[63] They said they are in the planning stages of incorporating reviews that specifically focus on a regulated entity’s use of AI into their examinations.

If warranted, concerns or noncompliance identified during examinations or other supervisory activities can result in supervisory findings, corrective actions, or enforcement actions. Examples of recent AI-related actions include the following:

· OCC has issued 17 matters requiring attention related to AI use since fiscal year 2020.[64]

· CFPB has taken six AI-related enforcement actions since 2020, including a 2022 action against a large bank for using an automated fraud detection system that unlawfully froze accounts.[65]

· NCUA has issued one document of resolution related to AI use since fiscal year 2020. In addition, it issued a regional director letter to a credit union for insufficient governance, reporting, and risk mitigation for an AI-driven program that instantly approved loans without traditional underwriting steps, such as income verification.[66]

· SEC brought at least eight AI-related enforcement actions in 2023 and 2024, including charging parties with making false and misleading statements about their purported use of AI in violation of the federal securities laws.[67]

Some Regulators Have Developed Guidance or Conducted Supervisory Activities Specific to AI

In addition to broadly applicable guidance, some regulators have issued guidance specifically addressing financial institutions’ use of AI in certain areas, such as fair lending and derivatives markets. For example, CFPB issued two circulars, in May 2022 and September 2023, to clarify adverse action notification requirements when creditors use AI or other complex credit models in decision-making.[68] Several CFTC divisions issued an advisory in December 2024 discussing legal requirements that may be relevant when regulated entities use AI to facilitate and monitor derivatives transactions.[69]

Some regulators have also conducted AI-focused supervisory activities.[70] For example, in 2023, SEC conducted examinations of the AI disclosures and governance of approximately 30 registered investment advisers. The primary purposes of these examinations were to identify candidates for more intensive examinations and to enhance SEC’s understanding of the industry’s AI uses and associated risks. SEC officials said most of the advisers they examined did not have comprehensive policies and procedures governing their AI use. Additionally, officials said several had misrepresented their use of AI.

The Federal Reserve, OCC, and CFPB have conducted reviews across several financial institutions that focused on AI use. For example, OCC conducted an AI-focused review of seven large banks from 2019 to 2023. OCC did not issue any matters requiring attention during this review, but it provided several AI-related observations and recommendations to the banks. Many of the large banks reviewed had satisfactory risk management practices for their AI and machine learning models. However, OCC found that some banks’ risk assessments did not explicitly capture risk factors and complexities unique to AI models. For example, some banks classified their AI and machine learning models as low risk, meaning they may be evaluated less frequently and be subject to less stringent governance requirements.[71] In addition, OCC found that the seven banks provided limited information on their efforts to evaluate bias and fair lending issues associated with AI or machine learning use. OCC reported plans to continue assessing how banks are managing potential bias and fair lending concerns with the AI models.

Federal Reserve officials stated they have conducted thematic reviews of supervised organizations to understand how AI is being used and risks are being managed. CFPB officials said they conducted reviews across several financial institutions that focused on tools marketed as AI. In June 2023, CFPB issued a report in response to one of these reviews, which discussed how financial institutions use chatbot technologies and the associated challenges chatbots could pose to consumers.[72]

Regulators have also issued warnings about AI misuse. For example, in January 2024, SEC, the North American Securities Administrators Association, and FINRA issued a joint investor alert warning of increased investment fraud involving the purported use of AI and other emerging technologies.[73] On the same day, CFTC issued a customer advisory warning the public about AI-related scams.[74]

NCUA Does Not Have Two Key AI Oversight Tools Available to the Other Prudential Regulators

FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC have issued model risk management guidance that can help inform regulated entities about supervisory expectations for managing risks from the use of AI models, but NCUA’s guidance is limited. Further, NCUA lacks authority to examine third-party services provided to regulated entities.

Model Risk Management Guidance

Model risk management is a key governance and risk management tool that financial institutions use to manage AI risks. Financial institutions use models, including AI, for predictive analytics, creditworthiness assessments, investment decisions, and risk management. However, weaknesses or unreliability in these models can lead to unsound strategic decisions that can affect a financial institution’s performance, profitability, and reputation. Effective model risk management helps organizations mitigate these potential adverse effects.

The banking regulators—FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC—have issued supervisory guidance on model risk management that includes principles applicable to all model types, including AI models.[75] Principles include sound development, consideration of complexity and transparency, and evaluation of performance through testing and independent validation. The banking regulators’ model risk management guidance is not specific to AI and is meant to apply more broadly to all types of models.

The principles described in the banking regulators’ model risk management guidance generally align with NIST’s leading practices for AI models.[76] For example, guidance from all three banking regulators stresses the importance of understanding and documenting model capabilities. In addition, the regulators’ guidance emphasizes the importance of ongoing monitoring and periodic review of the risk management process for models. NIST’s framework states that AI users do not need to implement all of its leading practices to have reasonable risk management. Instead, application of the framework should be tailored to how a firm or sector uses AI. As discussed previously, developments in AI could raise issues that may warrant future updates to regulators’ risk management guidance.

NCUA has also issued guidance on model risk management, but it is limited in scope and detail:

· The guidance addresses only one model type. The model risk management guidance contained in NCUA’s examiner guide addresses only interest rate risk modeling.[77] This stands in contrast to the banking regulators’ model risk management guidance, which broadly addresses all types of models, including AI models. However, NCUA officials noted that credit unions are increasingly using models in most aspects of financial decision-making, including loan underwriting, stress testing, and fraud detection. NCUA officials also stated that their model risk management guidance, last updated in October 2016, focuses on interest rate risk modeling because this was historically the most common type of modeling used by credit unions.

· The guidance provides limited detail. The model risk management guidance contained in NCUA’s examiner guide does not have sufficient detail to ensure examiners and credit unions follow key risk management practices, including those related to managing risks from AI models.[78] The guidance briefly describes some model risk management activities, such as components of a model validation framework. It also states that policies should designate responsibility for model development, implementation, and use. However, it does not provide sufficient detail or examples of what these practices should entail or how examinations should be tailored based on specific model uses and associated risks. Furthermore, NCUA’s guidance does not address other key model risk management activities, such as model selection or the frequency with which policies should be reviewed and updated.

NCUA officials identified additional agency guidance documents, such as their letter on enterprise risk management, as relevant to credit unions’ model risk management practices.[79] However, this guidance also does not provide detail or examples that clearly describe model risk management expectations.

NCUA’s guidance contrasts with that of the banking regulators, which includes details and examples for key model risk management activities. For example, the banking regulators’ guidance outlines expectations for independence, expertise, and authority for those responsible for validating models. It also provides examples of how to evaluate models’ conceptual soundness.

We could not compare NCUA’s guidance against the NIST AI Risk Management Framework because the guidance’s limited scope did not allow for a meaningful comparison. These limitations suggest that the current NCUA guidance is not adequate to ensure effective oversight of credit unions’ model use, including AI models. NCUA officials say they have considered updating their guidance but have not yet taken steps to do so.

NCUA’s examiner guide refers examiners to other banking regulators’ model risk management guidance. NCUA officials told us that while examiners are not required to follow that guidance, they can use it as a best practice when applicable. Similarly, federally insured credit unions can refer to other banking regulators’ guidance to inform their model risk management.

However, developing its own more detailed guidance for staff and regulated entities would help NCUA ensure that its expectations for addressing risks are clear, consistently implemented, and effectively monitored. Further, such guidance would strengthen NCUA’s ability to address credit unions’ AI-related risks. This approach would align with NCUA’s 2022–2026 strategic plan, which calls for ensuring that its policies appropriately address emerging financial technologies, including credit unions’ ability to manage opportunities and risks.[80] By establishing more detailed model risk management guidance—designed to also apply to AI models—NCUA could enhance its oversight and reduce potential risks to consumers and to the safety and soundness of credit unions.

Third-Party Risk Management and Oversight Authority

Third-party risk management is another key tool that financial institutions use to manage risks associated with AI.[81] In recent years, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC issued updated guidance on third-party risk management, highlighting the importance of financial institution oversight of third parties, which may include third parties providing AI technologies.[82]

As part of their standard supervisory processes, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and OCC review how their regulated entities manage third-party risks. Certain services provided by third parties on behalf of regulated entities are subject to regulation and examination by these agencies to the same extent as if such services were being performed by the regulated entity itself on its own premises.[83] According to interagency guidance, the agencies may pursue corrective measures when necessary to address violations of laws and regulations or unsafe or unsound banking practices by the banking organization or its third party.[84]

Similar to the banking regulators, NCUA evaluates credit unions’ third-party risk management practices during examinations.[85] However, NCUA’s enabling law—the Federal Credit Union Act—does not grant NCUA the same authority as the banking regulators to examine services performed by third parties on behalf of the entities it regulates.[86] According to a 2022 NCUA report, credit unions rely on third parties for a wide range of products, services, and activities.[87] NCUA officials noted that credit unions currently use third-party AI models to support core business functions, such as data processing, stress testing, risk management, loan decisions, and customer support. Credit unions typically do not have the resources to develop AI systems in-house, according to representatives we interviewed from NCUA, a credit union association, and a credit union.

In a 2015 report, we found that third-party services were integral to the operations of many credit unions, and that deficiencies in third-party providers’ operations could quickly result in financial and other harm for credit unions.[88] We concluded that granting NCUA the authority to examine third-party service providers would enhance the agency’s ability to monitor the safety and soundness of credit unions. We recommended that Congress consider modifying the Federal Credit Union Act to give NCUA the authority to examine technology service providers of credit unions. As of February 2025, Congress had not enacted legislation to implement this recommendation. Credit unions’ increasing reliance on third party technology services—which may include AI-related services—underscores the need to grant NCUA this authority. This would, in turn, enable NCUA to more effectively monitor and mitigate third-party risks, including those associated with AI-service providers, and ensure the safety and soundness of credit unions.

Regulators Have Taken Steps to Increase Their AI Knowledge

Regulators are taking steps to enhance their knowledge and understanding of AI, including training and hiring knowledgeable staff, establishing AI-related working groups and offices, and collaborating with domestic and international agencies, as well as nonfederal stakeholders.

Training. Financial regulators have provided staff with training opportunities that help supervisory staff better understand the benefits and risks of AI and how financial institutions are deploying the technology.[89] Some of the training has focused on institutions’ use of cutting-edge applications, such as generative AI. Representatives from three private-sector organizations we interviewed expressed concern that regulators might unnecessarily burden regulated entities—such as through unwarranted examinations or supervisory actions—if supervisory staff lack experience overseeing AI. Training efforts could help address these concerns.[90]

Internal AI-related initiatives. Financial regulators have established AI-related initiatives to help assess and monitor the potential effects of AI in the financial services industry. For example, one of FDIC’s divisions has an AI working group that has developed short- and longer-term strategies aimed at gathering data on and evaluating AI usage by regulated institutions. SEC’s Strategic Hub for Innovation and Financial Technology serves as a central hub for issues related to developments in financial technology, including AI.

Collaboration with domestic and international financial supervisors. Regulators have undertaken several interagency efforts to help increase their understanding of AI. For example, FSOC established an AI working group for FSOC members to share information, and its recent annual reports have included sections focused on AI.[91] Additionally, the Federal Reserve, OCC, FDIC, and NCUA work together on an interagency basis to better understand and monitor the risks and benefits associated with financial institutions’ use of AI. CFPB has also held periodic meetings with supervisors across the federal government focusing on emerging technologies, including a recent discussion on generative AI.[92]

Several financial regulators have also collaborated with their foreign counterparts. For example, staff from SEC are leading the International Organization of Securities Commissions’ FinTech Task Force AI Working Group. In addition, FDIC, Federal Reserve, and OCC officials said they participate in the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision, where they share AI practices across jurisdictions.

External communication and collaboration. Regulators also engage with nonfederal stakeholders to gain insights into AI use in the financial services sector. For example, regulators have issued several requests for comment on the opportunities and risks associated with the sector’s AI use.[93] In addition, OCC recently published a request that solicited academic research papers on the use of AI in banking and finance and planned to invite the authors to present their findings to OCC staff and academic and government researchers.[94]

Regulators Are Using AI to Enhance Their Supervisory Activities and Adopting Different Approaches to Expand Its Use

Federal financial regulators vary in their current and planned uses of AI, including using it for general agency operations and supervisory and market oversight activities. All regulators that were using AI as of December 2024 reported using AI outputs in conjunction with other information to inform decisions.

Regulators Use AI for a Variety of Activities, with Use Varying by Agency

Regulators’ Current and Planned Uses of AI

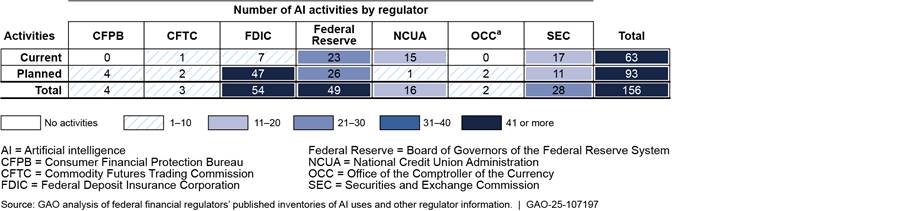

The extent of regulators’ current and planned AI use varies by agency, according to the federal financial regulators’ inventories of AI uses and other regulator information (see fig. 2).[95] As of December 2024, the Federal Reserve and SEC had the most activities using AI, and FDIC and the Federal Reserve had the most activities for which they plan to use AI in the future.

Figure 2: Number of Activities for Which Federal Financial Regulators Use or Plan to Use AI, as of December 2024

aAs of February 2025, OCC had not published its AI use inventory. The figure reflects information provided by OCC officials and may not represent its full inventory of current and planned AI uses.

Regulators are using or plan to use AI for a variety of general agency operations. For example, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, NCUA, and SEC use AI for activities such as creating and editing graphics, videos, and presentations, and answering staff questions. FDIC may use AI to score job application essays, such as to assess their grammar and mechanics, analysis and reasoning, and organization and structure.

In addition, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and SEC plan to use AI to extract information from files. For example, the Federal Reserve plans to input large amounts of data from paper forms into a digital system, while FDIC plans to extract data from PDF invoices and contracts for reconciliation purposes.

Supervisory and Market Oversight Uses of AI

The federal financial regulators are using AI for supervisory and market oversight activities, including identifying risks, supporting research, and detecting potential legal violations, reporting errors, or outliers.

Identifying risks. NCUA, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and SEC use AI to analyze data, identify patterns, or make predictions to help identify risks facing regulated financial institutions or financial markets. For example, NCUA uses AI in stress testing, which helps examiners assess the potential impact of various economic conditions on larger credit unions’ financial performance.[96] NCUA officials noted that if AI analysis predicts a credit union will fall short of minimum capital ratio requirements, NCUA examiners consider the prediction alongside other supervisory information before deciding on an action.[97] NCUA officials also told us they are researching AI applications for predicting a credit union’s financial condition over various time frames.

Supporting research. The Federal Reserve, FDIC, and SEC use AI to search, analyze, and extract relevant information from large collections of documents. Examples of the documents include regulatory filings, examination documents, public comment letters on proposed rulemakings, and news articles, depending on the agency. For example, the Federal Reserve uses AI to search bank examination documents, providing examiners with a fast and flexible method to search for specific keywords and phrases. The volume of documents varies by bank, but most collections range from 100 to over 1,000 documents, with individual documents ranging from several to over 100 pages. Prior to AI adoption, examiners reviewed documents manually. Federal Reserve officials said AI use has improved examiners’ productivity by allowing them to focus on supervisory priorities and more complex tasks.

Detecting potential legal violations. FDIC and SEC use AI to complement their other methods for identifying patterns in data that may indicate higher risk of violations of consumer or federal securities laws. For example, officials from SEC told us staff use AI tools in efforts to detect potential insider trading. Subject matter experts review flagged trades to determine if further investigation is warranted, officials said. FDIC also plans to use AI to extract data from credit reports, which will help examiners gather information needed to assist in determining compliance with fair lending laws. As of December 2024, CFPB planned to use AI to help staff analyze consumer complaints.

Detecting reporting errors or outliers. NCUA, CFTC, and the Federal Reserve use AI to help detect errors or outliers in data submitted by financial institutions. For example, NCUA uses AI to predict the future value of items in Call Reports (the quarterly financial reports that credit unions must submit) and flag those that fall outside the predicted range. NCUA officials told us that when discrepancies are flagged, they ask the credit union to review the flagged items and correct them if necessary.

Officials from each regulator told us they were not using generative AI for supervisory or market oversight activities, although some regulators were considering or exploring generative AI use. OCC officials said they intend to use generative AI to help examiners identify relevant information in supervisory guidance and assess risk identification and monitoring in bank documents. Federal Reserve officials said they are exploring potential ways to use generative AI for supervisory purposes.

Officials from all regulators that were using AI as of December 2024 told us they used AI outputs in conjunction with other supervisory information, such as examination reports and financial data, to inform staff decisions. They said they were not using AI to make decisions autonomously or relying on it as a sole source of input.

According to most of the regulators, AI increases their efficiency and effectiveness. For example, FDIC reported that its use of AI to score job applications may speed up processing and reduce costs. Most regulators also said AI tools can identify issues, patterns, and relationships not easily identified by a human. The U.S. House of Representatives’ Bipartisan Artificial Intelligence Task Force found that AI adoption can improve regulators’ efficiency and productivity, assist regulators in understanding and overseeing AI use in the financial services sector, and help identify regulated institutions in noncompliance with regulations.[98]

Policies and Procedures for AI Use

All of the federal financial regulators told us their existing policies and procedures for the general use of technology apply to their AI use as well.[99] These policies cover data protection, IT security, model risk management, and the acquisition or oversight of third-party software.

In addition, some regulators have developed or are developing AI-specific policies and procedures. The Federal Reserve recently introduced AI-specific policies for the design, development, and deployment of AI systems. NCUA recently developed an AI-specific policy that prohibits its employees from accessing certain publicly available AI tools on NCUA-issued equipment and devices. Officials from OCC and SEC told us they are in the process of developing AI-specific policies and procedures. For example, according to officials, OCC is developing an AI risk framework and considering how to incorporate the NIST AI Risk Management Framework and other AI guidance.

Regulators Are Taking Different Approaches to Identify Additional AI Uses

Financial regulators are using or planning to use different approaches to identify additional AI uses, according to documents we reviewed and discussions with officials.

· CFPB was working to develop strategies to allow for the responsible, safe, and effective use of AI and was approving AI use cases for limited pilots, according to agency documentation from September 2024.[100]

· CFTC launched an initiative that identified and scored 27 potential AI uses, based on their technical feasibility and value to the agency. These include uses such as identifying new potential enforcement actions or saving staff time.

· FDIC developed an AI strategy document, which includes goals to (1) develop the ability to increase the size of AI projects and (2) enable FDIC divisions to have autonomy and flexibility in deploying AI. The strategy also describes how the agency plans to achieve its goals. Additionally, FDIC has established a working group to review and assess potential AI uses.

· The Federal Reserve developed a road map to identify potential AI uses, experiment with AI systems, and implement value-added AI uses. In addition, the Federal Reserve established a working group to experiment with and identify potential uses for generative AI, manage AI risks, and ensure compliance with external governance policies.

· NCUA is developing a process for offices to request the use of AI tools developed by third parties, according to officials.

· OCC is working on a process to identify and implement AI tools to enhance its supervision and oversight capabilities, according to officials.

· SEC plans to develop an AI strategy in 2025 to help identify and prioritize AI uses, according to officials. SEC divisions and offices would be responsible for prioritizing the implementation of AI uses that they identify and that the AI steering committee approves. The AI steering committee would also advise the Chief AI Officer on prioritizing agencywide uses, they said.

Conclusions

The rapid advancement and widespread adoption of AI warrant robust oversight tools for federal financial regulators. We therefore reiterate our prior recommendation that Congress consider granting NCUA authority to examine technology service providers of credit unions. Such authority would enhance NCUA’s ability to monitor and address third-party risks, including those associated with AI service providers. Further, unlike the banking regulators, NCUA does not have detailed model risk management guidance that covers a broad variety of models, including AI models. Developing such guidance would strengthen NCUA’s ability to address risks to consumers and to the safety and soundness of credit unions arising from the use of AI.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Chair of NCUA should update the agency’s model risk management guidance to encompass a broader variety of models used by credit unions and provide additional details on key aspects of effective model risk management. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

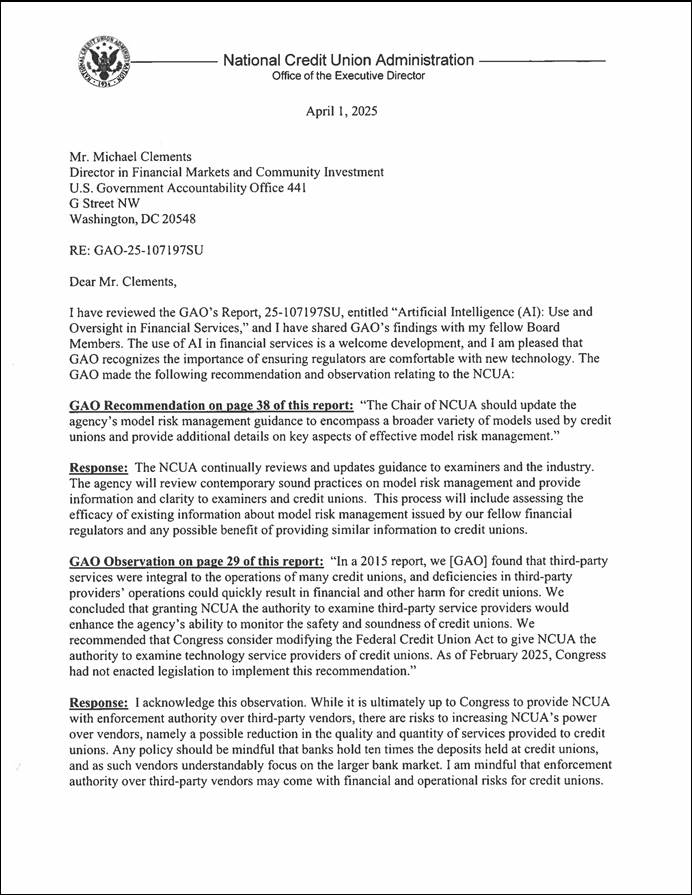

We provided a draft of this report to CFPB, CFTC, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, NCUA, OCC, and SEC for review and comment. We received written comments from NCUA, which are reproduced in appendix III. In addition, CFPB, CFTC, FDIC, the Federal Reserve, OCC, and SEC provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

NCUA generally agreed with our recommendation. In its written comments, NCUA noted that it will review contemporary sound practices on model risk management, such as the banking regulators’ guidance, and provide information and clarity to examiners and credit unions. NCUA’s plans to review current model risk management practices are consistent with the intent of our recommendation. However, we maintain that NCUA should also update its guidance so that it contains more details on key aspects of model risk management and information on additional types of models.

In addition, NCUA acknowledged our recommendation to Congress that it consider providing NCUA authority to examine technology service providers of credit unions. However, the Chairman noted that there are risks to providing NCUA such authority, including a possible reduction in the quality and quantity of services provided to credit unions and financial and operational risks for credit unions. However, we maintain that examination authority over third-party service providers would enhance NCUA’s ability to monitor and address third-party risks and ensure the safety and soundness of credit unions.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Acting Director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Acting Chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, Acting Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Chairman of the National Credit Union Administration, Acting Comptroller of the Currency, Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at clementsm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Michael E. Clements

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

List of Committees

The Honorable John Thune

Majority Leader

The Honorable Charles E. Schumer

Minority Leader

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Johnson

Speaker

House of Representatives

The Honorable Steve Scalise

Majority Leader

The Honorable Hakeem Jeffries

Minority Leader

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Boozman

Chairman

The Honorable Amy Klobuchar

Ranking Member

Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry

United States Senate

The Honorable Tim Scott

Chairman

The Honorable Elizabeth Warren

Ranking Member

Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Bill Hagerty

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Glenn “GT” Thompson

Chairman

The Honorable Angie Craig

Ranking Member

Committee on Agriculture

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chair

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable French Hill

Chairman

The Honorable Maxine Waters

Ranking Member

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Dave Joyce

Chairman

The Honorable Steny Hoyer

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

This report examines (1) the potential benefits and risks of artificial intelligence (AI) use in financial services, (2) federal financial regulators’ oversight of AI use in the financial services industry, and (3) federal financial regulators’ use of AI in their supervisory and market oversight activities. We focused our review on the use of AI by financial institutions and regulators and oversight of AI use in banking and in the securities and derivatives markets.[101] We did not include state or local laws and regulations in our review.

For our first objective, we analyzed reports, studies, and speeches that address the benefits and risks of AI from federal agencies, international nongovernment organizations, foreign regulators, industry groups, and research and academic institutions. We identified the reports and studies by conducting internet research, reviewing literature search results, and obtaining recommendations from entities we spoke with.

We also interviewed representatives of seven federal financial regulators; six industry groups representing banks, credit unions, financial technology companies, and securities and derivatives market participants; three consumer and investor advocacy organizations; five research and consulting groups; four depository institutions; and three technology providers.[102] We identified potential interviewees by conducting internet research, reviewing literature search results, and obtaining recommendations from our initial interviews. We selected interviewees that could provide perspectives on AI in banking or in the securities or derivatives markets. The information gathered from our interviews cannot be generalized to all companies that develop or use AI in financial services.

To identify common AI uses in financial services, we used a snowball sampling approach in which we identified AI uses as we collected documents and conducted interviews. We limited our review of documents to those published in 2020 or later, given the rapid pace of the development of AI. Upon identifying 168 AI uses in 25 sources, we determined that we had a sufficient number of sources to conclude our snowball sampling exercise. To categorize the AI uses, two analysts independently developed preliminary categories based on a review of the identified uses. We developed final categories by comparing and refining the preliminary categories.

To identify the potential benefits and risks of using AI in financial services, we analyzed the reports, studies, and speeches we collected and interviews we conducted. To categorize the benefits and risks, two analysts independently developed preliminary categories based on their review of the collected evidence. We developed final categories by comparing and refining the preliminary categories.

For our second objective, we reviewed federal laws, executive orders, regulations, guidance, and other agency documentation relevant to the oversight of financial institutions’ use of AI. Agency guidance and documentation included interagency guidance on third-party relationships, agency model risk management guidance, and internal examination guides, among others. We also interviewed officials from the seven federal financial regulators and representatives of the industry stakeholders mentioned above to gather additional insights.

We reviewed the model risk management guidance of the prudential regulators—the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC).[103] We also assessed the guidance’s general alignment with leading practices in the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) AI Risk Management Framework.[104]

We limited our review to model risk management guidance documents because the prudential regulators identified them as key oversight guidance for reviewing regulated entities’ AI use. A review of other regulators’ model risk management guidance was outside the scope of this report.

The NIST AI Risk Management Framework describes leading practices that can foster responsible design, development, deployment, and use of AI systems in general. It consists of four functions—Govern, Map, Measure, and Manage—that include a total of 19 leading practice categories. These categories consist of 72 subcategories. Furthermore, the subcategories typically include several discrete components.

To compare the regulators’ guidance against the NIST framework, we developed yes/no questions for each leading practice described in the framework and categorized the leading practices as (1) “yes” if the guidance reflected all of the elements of a category or subcategory, (2) “partial” if some but not all of the elements of a category or subcategory were present, or (3) “no” if the elements of a category or subcategory were not reflected in the guidance. One analyst scored the model risk management guidance for each of the banking agencies. A second analyst then independently reviewed the first analyst’s scores. The analysts discussed any differences of opinion to determine a final score.

We could not compare NCUA’s model risk management guidance against the NIST framework because NCUA’s guidance lacked sufficient scope and detail to make a meaningful comparison. Instead, we assessed NCUA’s model risk management guidance against relevant goals and objectives described in NCUA’s 2022–2026 strategic plan.[105]

To describe steps federal financial regulators are taking to prepare for increased AI adoption in the financial services industry, we reviewed documentation of their AI-related initiatives, including training efforts, and establishment of internal AI-related entities.

For the third objective, we reviewed federal laws, executive orders, guidance, agency reports, strategic plans, policies and procedures, and other agency documents related to how federal financial regulators are using AI in their supervisory and market oversight activities. Additionally, we interviewed officials from the seven federal financial regulators.

To identify the number of activities for which the seven financial regulators use or plan to use AI, we reviewed their inventories of AI uses.[106] Because OCC had not published its 2024 inventory by the time our audit work was completed, we used information provided by OCC officials on the agency’s supervisory and market oversight AI uses as of December 2024. As a result, the number of uses we report may not represent OCC’s entire inventory of AI uses.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

|