MILITARY TO CIVILIAN TRANSITION

Actions Needed to Ensure Effective Mental Health Screening at Separation

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-25-107205, a report to congressional committees

For more information, contact Alyssa M. Hundrup at hundrupa@gao.gov.

MILITARY TO CIVILIAN TRANSITION

Actions Needed to Ensure Effective Mental Health Screening at Separation

Why GAO Did This Study

Thousands of service members separate from the military each year, and research has shown that they are especially vulnerable during this transition to civilian life. A 2018 executive order directed VA and DOD to develop a joint action plan to ensure access to mental health care and suicide prevention services for separating service members. The resulting plan called for mental health screenings of all service members prior to separation, among other initiatives.

The House report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review VA and DOD’s implementation of mental health exams for service members transitioning out of the military. Among other topics, this report examines the extent to which VA and DOD based the joint separation health assessment’s mental health screening questions on validated screening tools and the outcomes of VA’s mental health screening using the joint assessment.

To address these objectives, GAO reviewed selected scientific studies to determine the effectiveness and reliability of the joint assessment’s specific mental health screens. GAO also reviewed validated screening tool recommendations in relevant clinical practice guidelines issued by organizations including VA and DOD. GAO interviewed VA and DOD officials, as well as mental health subject matter experts identified by professional associations such as the American Psychiatric Association.

GAO reviewed available mental health screening data from joint separation health assessments completed by VA contractors between May 2023—the month following its implementation—and April 2024. GAO also reviewed VA guidance for administering the joint assessments, including the process to be followed when a service member screens positive for mental health concerns, including their risk for suicide. Finally, GAO interviewed VA officials and representatives of the three contractors that administer the joint assessments about what steps they take if someone screens positive on the mental health screening questions.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making a total of three recommendations to the VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee that developed the joint separation health assessment to (1) ensure that the joint assessment’s alcohol use screen is validated, (2) ensure that the joint assessment’s PTSD screen is validated, and (3) assess whether to include violence risk screening in the joint assessment and take appropriate follow-up action. Possible actions could include taking steps to validate the joint assessment’s existing violence risk questions, replacing them with a different validated tool, or removing the questions, as appropriate.

VA concurred with GAO’s recommendations while DOD partially concurred with them. DOD stated that the VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee should explore using validated screens but did not commit to ensuring that the alcohol use, PTSD, and violence risk screens are validated. GAO maintains its recommendations are warranted and that any screening tool used in the joint assessment be validated.

What GAO Found

Federal law and Department of Defense (DOD) policy require health exams for service members separating from active duty. DOD administers most exams for these service members. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) administers these exams for service members filing for disability benefits at separation, such as those with an illness or injury caused by military service. To help coordinate efforts, VA and DOD developed a joint separation health assessment with mental health screens not included in DOD’s existing separation exam. VA implemented the joint assessment in April 2023. As of May 2025, DOD had not implemented the joint assessment but had completed a pilot of it at three sites.

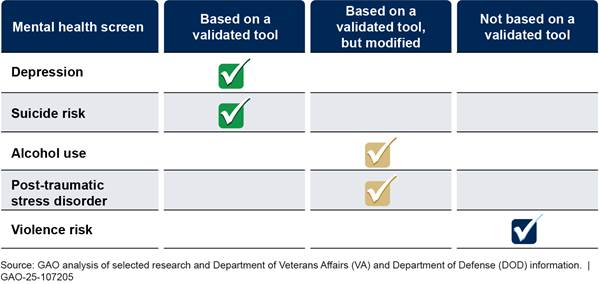

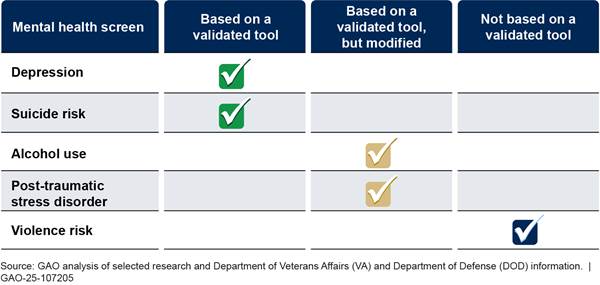

The joint assessment includes five mental health screens for 1) depression, 2) suicide risk, 3) alcohol use, 4) post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and 5) violence risk. GAO found that two of these mental health screens are validated tools. This means that they have been tested and determined to be both effective at identifying individuals at risk for a specific condition and reliable at yielding consistent results if administered to the same individual more than once. Two of the other mental health screens are based on validated tools, but VA and DOD modified the screens without validating the changes.

The remaining joint assessment screen for violence risk is not based on a validated tool. It was included for consistency with other DOD health assessment forms, according to officials. Research shows that violence screening may be useful for service members, but multiple subject matter experts GAO interviewed expressed concerns about the violence risk screen’s effectiveness.

Research shows that without validation testing, VA and DOD cannot be sure about the effectiveness or reliability of the screening they are conducting for alcohol use, PTSD, and violence risk. Using validated mental health screens would provide VA and DOD with greater assurance that their efforts to identify service members needing mental health support at separation are effective.

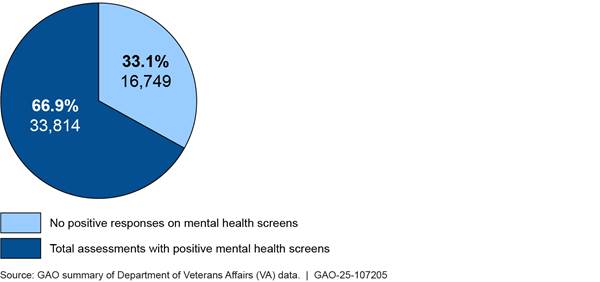

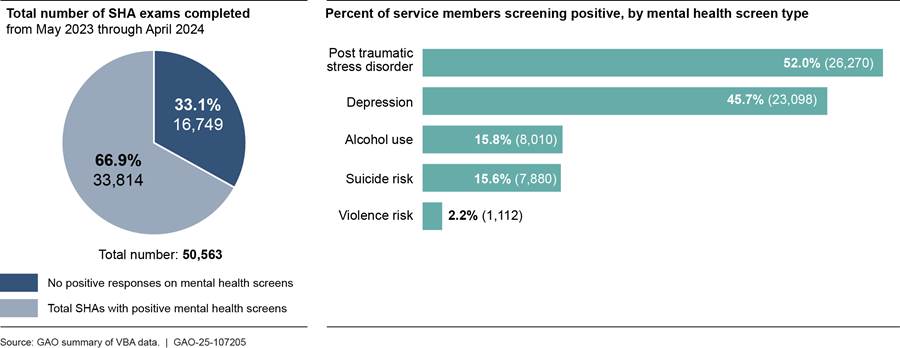

VA data show its contractors administered about 50,500 joint separation health assessments between May 2023 and April 2024 to service members being evaluated for disability benefits. Of those exams, about 67 percent of service members had at least one positive mental health screen. A positive screen indicates elevated risk for the specific mental health condition being assessed and can indicate a need for further evaluation or intervention.

GAO found that VA’s most common positive mental health screens on the joint assessment were for PTSD and depression. VA and DOD officials noted that overall, the joint assessment screening rates are higher than would be expected in a clinical setting or based on population prevalence for these disorders. In the case of screening for alcohol use and PTSD, VA and DOD modifications to these tools may have contributed to higher positive screening rates. Additionally, DOD officials said that many factors could increase the possibility of positive mental health screens among separating service members, including that this subgroup of service members intends to file disability claims.

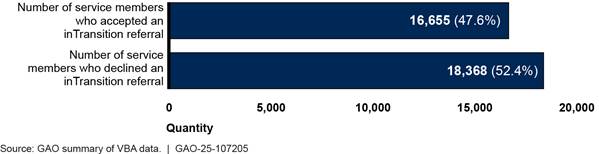

Clinicians administering the joint assessments are required to ensure that service members who screen positive are aware of available mental health care options and offer them a referral to DOD’s inTransition program, which is to offer support with mental health services during transitions. GAO’s analysis of VA’s joint assessment data found that 48 percent of service members who were offered an inTransition referral accepted, and 52 percent declined. VA does not track service members’ reasons for declining these referrals. However, VA officials noted that some service members might decline the referral if they are already involved in mental health treatment.

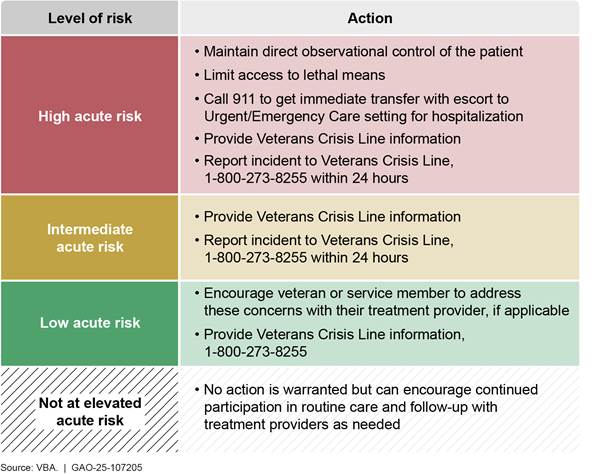

Additionally, when service members screen positive for suicide risk on the joint assessment, clinicians are to assess their level of risk and take specific actions based on that determination. For example, clinicians are required to contact the Veterans Crisis Line for high-risk individuals, among other actions.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

PTSD |

post-traumatic stress disorder |

|

SHA |

Separation Health Assessment |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

|

VBA |

Veterans Benefits Administration |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 5, 2025

Congressional Committees:

Each year, service members separate from the military and transition back to civilian life, with more than 210,000 service members separating in fiscal year 2023, according to Department of Defense (DOD) data.[1] Research has shown that during this transition period, service members are especially vulnerable. For example, the suicide rate has been about 2.5 times higher for veterans in the first year of separation than for the active-duty population.[2] This increased risk can be attributed to the many challenges that service members face during this time, such as loss of a sense of purpose, familial and financial strain, and difficulty readjusting to social and civilian life.

To help address this risk, a 2018 executive order directed the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and DOD to develop a joint action plan to ensure access to mental health care and suicide prevention services for service members transitioning out of the military.[3] The joint action plan created in response to the executive order identified several initiatives that targeted mental health care and suicide prevention and included a call for conducting mental health screening of all service members prior to separation.

Through the VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee—an interagency committee established in 2003—the departments determined that the mental health screening called for in the joint action plan would occur as part of a joint Separation Health Assessment (SHA) that the departments would develop starting in 2019. This new, joint SHA would replace DOD’s Separation History and Physical Examination, and the previous exam used by VA’s Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) for service members applying for disability compensation at separation. VA and DOD developed the joint SHA from 2019 through 2022, and VBA began using it for those service members applying for disability compensation after April 1, 2023. As of May 2025, DOD had not implemented the joint SHA. It had completed a pilot of it at three sites, and officials told us that based on the pilot’s results they were discussing next steps with leadership to identify the most appropriate way forward.[4]

The House report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to review VA’s and DOD’s implementation of mental health exams for service members transitioning out of the military.[5] In our report, we

1. describe how VA and DOD developed the joint SHA and VA’s experience implementing it;

2. assess the extent to which VA and DOD based the joint SHA’s mental health screening questions on validated screening tools; and

3. describe the outcomes of VBA’s joint SHA mental health screening.

To describe how VA and DOD developed the joint SHA, we interviewed VA and DOD officials who were on the Joint Executive Committee’s working group that developed the joint SHA. We reviewed relevant documentation, such as VA and DOD’s memorandum of agreement related to the SHA, working group workpapers, Joint Executive Committee annual reports, the joint SHA form, and the prior 2020 VBA separation exam form. To understand VA’s experience implementing the joint SHA, we interviewed additional VA officials, such as officials from VBA’s Medical Disability Examination Office and representatives of the three contractors VBA uses to provide the medical professionals who administer the SHA exams for disability claims. Because DOD had not implemented the joint SHA at the time of our review, this report focuses on VA’s implementation experience.

To examine the extent to which the joint SHA’s mental health screening questions were based on validated screening tools, we reviewed evidence from selected research to determine the effectiveness and reliability with which these screening questions sufficiently identify individuals exhibiting symptoms of certain mental health conditions.[6] We included a targeted literature search for our review.[7] This search identified scientific studies that evaluated the validity and various relevant psychometric properties of the joint SHA’s mental health screens or the screens they were based on.[8] We then used the findings from the studies to determine the validity of the joint SHA’s screening tools. If a majority of the studies we reviewed for each screening tool concluded that said tool was valid, we considered that as confirmation of the tool’s validity. If we identified variations between the mental health screening questions on the joint SHA and the original screen the questions were based on, we considered the screen to be modified only if the variations changed the content or meaning of the original. If a screen had been modified, we asked VA and DOD officials if the new version had been validated. For each of the validation studies cited in this report, we reviewed the study methodologies and determined that they were suitable for determining the validity of the respective screening tool.

We also reviewed and compared the joint SHA’s mental health screening questions with validated screening tool recommendations in relevant VA/DOD mental health clinical practice guidelines and other relevant guidelines from organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association. We reviewed relevant studies cited as evidence in some of these guidelines. In addition, we interviewed subject matter experts identified by selected medical specialty associations to obtain their perspectives on the mental health screens used in the joint SHA. Specifically, we conducted two separate group interviews: one with four staff and experts identified by the American Psychiatric Association and another with seven staff and experts identified by the American Psychiatric Nurses Association.[9] We also conducted individual interviews with four experts identified by the American Medical Association and received written responses to our interview questions from one additional expert.[10] The experts identified by the American Medical Association had expertise in various areas of behavioral health, including suicide prevention, psychiatry, and veteran populations. Finally, we interviewed VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee officials who were on the working group that developed the joint SHA to discuss their consideration of each mental health screen’s validity.

To describe the outcomes of VBA’s joint SHA mental health screening, we reviewed available data from joint SHA exams completed by VBA contractors between May 2023 (the month following the joint SHA’s implementation) and April 2024 (the most recent data available at the time of our request). Specifically, we reviewed data related to the outcomes of the joint SHA mental health screening. These outcome data included information on VBA referrals to the requisite mental health transition program resulting from the screening. To assess the reliability of the joint SHA outcomes data, we performed manual testing for obvious errors and interviewed agency officials knowledgeable about the data. When we found discrepancies (such as data that did not sum to expected totals), we brought them to VBA officials’ attention and worked with officials to correct them. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report.

We also reviewed VBA guidance related to administering the joint SHA exams to determine what process should be followed when a service member screens positive for mental health concerns, including their risk for suicide. We interviewed VA officials and representatives of the three VBA contractors who administer joint SHA exams about what steps they take if someone screens positive on the mental health screening questions. In addition, we interviewed and obtained written responses from VA and officials on the working group that developed the joint SHA about any current efforts or plans for tracking and analyzing the outcomes of its mental health screening sections.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2023 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Separation Health Exams

Federal law and DOD policy require separation health exams for service members who are separating from active duty and for certain Reserve component service members who are leaving the military.[11] Since 1998, VA and DOD have made efforts to establish a single separation exam.[12] In 2004, VA and DOD established a memorandum of agreement to support a cooperative separation process that meets DOD’s need to conduct separation exams and VA’s need to conduct disability compensation evaluations for some separating service members.[13] In 2013, VA and DOD agreed that regardless of which department conducted the separation exam, it would include the following:

· a subjective health assessment completed by the service member in advance of the exam, and

· an objective health assessment completed by a medical professional.[14]

|

Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) Disability Exams for Service Members VBA pays disability compensation to veterans with service-connected disabilities based on the severity of their disability. A service-connected condition refers to an illness or injury that was caused by—or got worse because of—active military service. Service members who are separating from the military can file a claim for disability benefits 180 to 90 days before leaving the military through VBA’s Benefits Delivery at Discharge program. This time frame allows VBA to review service records, schedule needed exams, and evaluate the claim before separation. VBA also conducts separation exams for service members being evaluated through the joint Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and Department of Defense (DOD) Integrated Disability Evaluation System. Under this system, when DOD finds a service member to be unfit for continued military service VA conducts exams and helps DOD determine the disposition of the wounded, ill, or injured service member and provides disability benefits, if appropriate. Source: VBA. | GAO‑25‑107205 |

In a 2022 update to their memorandum of agreement, VA and DOD agreed that separation exams would also include mental health screening.[15]

Most service members will have their required separation health exam administered by DOD. However, separating service members who will be filing a disability benefits claim with VA before they leave the military will have their separation exam completed by VA. For fiscal year 2023, VBA reported that it completed more than 59,000 separation exams, representing about one quarter of the service members who separated from the military that year.[16]

VBA uses three contractors to provide the medical professionals, or examining clinicians, who conduct most of the separation exams for VA.[17] In fiscal years 2023 and 2024, VBA reported that more than 99 percent of separation exams were completed by contractors.[18] The three VBA contractors are to send the completed exam forms to VBA, which uses the results as part of its disability compensation determination. VBA is also to transfer copies of these exam results to DOD.

VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee

The VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee was established to oversee coordination between VA and DOD on providing health care and benefits and to provide annual reports to the Congress on its efforts.[19] In this capacity, the committee serves as the primary federal interagency body for overseeing military transition assistance activities. The Joint Executive Committee has numerous subcommittees, business lines, and working groups, including the Transition Executive Committee and the SHA Working Group.

The SHA Working Group was initially established following a 2011 agreement between VA and DOD to develop a standardized separation health assessment program. Although specific workgroup membership has changed over time, the workgroup includes members from both departments, such as officials from VBA, the Veterans Health Administration, DOD, and the military services. In addition to developing the joint SHA, other activities of the workgroup have included efforts to digitally transfer service treatment records from DOD to VA.

To guide its efforts, the Joint Executive Committee develops a strategic plan. The strategic plan for fiscal years 2019 through 2021 included an objective related to “Mandatory Separation Health Examinations.” Specifically, one milestone related to that objective called for reviewing and updating certain baseline exams—the VA separation exam, the DOD Separation History and Physical Examination, and a mental health assessment—to inform a Joint Executive Committee decision on modifying these exams to reduce VA and DOD duplication. The Joint Executive Committee assigned this objective and milestone to the SHA Working Group. According to VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee documents, the purpose and goals of this effort included eliminating any duplication of efforts, improving clinical documentation of health status at the time of separation, and streamlining the transition of health care from DOD to VA.

Service Member and Veteran Mental Health Challenges

Military service, especially combat, may carry a psychological cost for service members and veterans. Although estimates vary across studies, evidence suggests that the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in service members deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, or both may be as high as 13 to 17 percent.[20] Further, a meta-analysis of 25 studies estimated the prevalence of recent major depression at a rate of 13 percent among previously deployed military personnel.[21] Studies have also found that mental health conditions such as mood disorders, alcohol use disorders, and PTSD, particularly with co-occurring depression, were significant risk factors for suicide attempts among veterans who served in support of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom.[22]

While combat is known to be associated with these mental health conditions, general military service can also bring challenges, such as deployments that separate service members from family and increase their risk of depression.[23] The transition out of the military can also trigger mental health concerns. Upon entering civilian life, veterans may have difficulty translating their military skills to a civilian job, and they may struggle to find employment, housing, and the other benefits that were provided as part of their military service. Additionally, veterans may struggle to reconnect with their family or relate to people who have not served in the military.

Mental Health Screening

Mental health screening is used for the early identification of individuals potentially at high risk for a specific condition or disorder. During a mental health screening, individuals answer questions about their symptoms. A clinician may ask the questions, or individuals may fill out a questionnaire and discuss their answers with a clinician afterwards.

There are specific screening tools for different types of mental health conditions, such as PTSD and depression, as well as for suicide risk. These screening tools typically follow their own protocol for scoring, which defines what constitutes a positive screen, and have guidelines for individuals that screen positive. For example, for some tools one “yes” response to any question may constitute a positive screen, while other tools might have complex scoring protocols for what constitutes a positive screen.

Mental health screening is not intended to be diagnostic. Instead, the results of a mental health screen—particularly a positive screen—can indicate a need for further evaluation or intervention. If the results show signs of a specific condition, disorder, or risk of suicide, the recommended follow-up may vary based on the individual’s level of risk. For example, if a respondent’s score on a mental health screen is particularly high or they screen positive on multiple mental health screens, they may be considered at high risk and require more urgent follow-up. Possible next steps for a positive screen include brief intervention if risky behavior is identified, discussion of possible conditions, referral to a mental health provider for further evaluation or treatment, or admittance to a hospital if someone is at high risk of a suicide attempt.

VA, DOD, and organizations such as The Joint Commission and the American Psychological Association have recommended that a validated tool be used when conducting various types of mental health screening.[24] A validated tool is an instrument that has been tested and determined to be both effective at identifying individuals at risk for a specific condition and reliable at yielding consistent results if administered to the same individual more than once.

DOD’s inTransition Program

Based on service members’ responses to the mental health screening questions in separation exams, examining clinicians may refer them to DOD’s mental health transition program—inTransition.[25] Established in 2010, inTransition is a voluntary program intended to facilitate connections to mental health services for service members at various transition points.[26] These transition points include when service members are preparing to leave military service, when they are transitioning between duty stations, or when they are returning from deployment.

The inTransition program is a confidential program with coaches—licensed psychological health clinicians—who are to provide support services by telephone to the program’s enrollees.[27] The coaches may refer service members to mental health providers, as well as provide information on community resources and support groups, among other services. Coaches do not provide telephonic mental health care or other health care services.

In July 2024, we reported about access to mental health services for service members transitioning out of the military and identified concerns with DOD’s inTransition program.[28] For example, we found that the program faced difficulties in successfully connecting with a significant portion of eligible separating service members in 2022. We also found the program did not have performance goals or associated quantitative targets and time frames against which its performance can be assessed.

We made four recommendations to DOD related to the inTransition program, including to revise inTransition’s policy to expand outreach methods. DOD concurred with all our recommendations and identified actions the department planned to take to address them, such as expanding outreach methods to include email and text messaging. As of May 2025, our recommendations remained open. By implementing them, DOD could better ensure the program’s ability to successfully connect with its enrollees and support continuity of any needed mental health services during the transition period.

VA and DOD Used Existing Health Assessments to Develop the Joint SHA; VA Reported Smooth Implementation

VA and DOD Included Five Mental Health Screens in the Joint SHA

As part of the process to develop a joint SHA, we found that the SHA Working Group took a number of steps, including the following:

· conducted a comparative analysis of 10 VA and DOD health assessment forms they determined to be relevant;[29]

· identified two groups of question types across the forms: 1) self-assessment questions to be completed by the service member, and 2) clinical questions asked by the clinician during the service member’s exam;

· grouped the questions identified into nine general categories, one of which was mental health;[30]

· established sub-working groups of subject matter experts from VA and DOD for multiple health-specific areas, including mental health; and

· adjudicated the questions for inclusion in the SHA, as recommended by the sub-working groups.

Specific to mental health, the SHA Working Group focused on questions in four of the 10 VA and DOD forms that included mental health assessments and compared the questions across these four forms to identify commonly used screens.[31] The mental health sub-working group was then tasked with reviewing and analyzing the evidence base of the mental health related questions identified in the commonly used screens in the comparative analysis. Following this review, the mental health sub-working group made recommendations to the SHA Working Group for what mental health screens should be included in the joint SHA. Ultimately, the five selected screens were: 1) depression, 2) PTSD, 3) alcohol use, 4) suicide risk, and 5) violence risk.[32]

The SHA Working Group decided to split up the five mental health screens between the self- assessment portion of the form and the clinical assessment portion as follows:

· Part A, the self-assessment medical history questionnaire, has 10 medical history sections, including one for mental health. This mental health section includes three screens for depression, PTSD, and alcohol use.[33]

· Part B, the clinical assessment, has nine primary sections, including a mental health section. The mental health section includes screenings for suicide risk and violence risk respectively. It also includes an in-person review of mental health symptoms.

VBA Officials Described Smooth SHA Implementation

VBA officials described the implementation of the joint SHA in 2023 as smooth. They explained that their contractors were already using a similar exam—with similar mental health screens—for separating service members being evaluated for disability benefits.

In August 2020, VBA implemented an updated separation exam that included five mental health screens similar to those included in the joint SHA.[34] According to VBA officials, they updated their separation exam with these five mental health screens in 2020 because VBA officials knew these screens were likely to be included in the final, joint SHA. We compared the five mental health screens in VBA’s 2020 separation exam with those in the joint SHA and found that they were largely the same.[35] Both exams include the same five mental health screening topics, with minimal changes to the questions.

Representatives from VBA’s contractors who administer the SHA exams described some initial challenges with the implementation of the new joint SHA in 2023. However, they did not tie these challenges to the mental health sections of the SHA. Instead, they cited challenges such as needing 30 more minutes overall to conduct each exam. They also mentioned that new requirements, including an audiology exam, as well as the self-assessment portion of the SHA not always being filled out completely or correctly by service members contributed to the joint SHA taking more time to administer. Representatives from VBA’s contractors did not cite any ongoing challenges related to administering the joint SHA or its mental health screening sections specifically.

While VBA has reported a smooth transition to the joint SHA, DOD may experience more challenges due to differences between its current separation exam and the joint SHA. For example, DOD’s current separation exam as of January 2025—the Separation History and Physical Examination—does not include the five mental health screens that are in the joint SHA. A military service official told us that they anticipated challenges in implementing the joint SHA because it is more comprehensive than the current exam, and it will take more time to administer. A DOD official told us that the department’s joint SHA pilot, which ended in January 2025, will provide information on how long these exams will take and any other implementation challenges that DOD may need to address.

Two of the Five Joint SHA Mental Health Screens Are Based on Validated Tools, but VA and DOD Have Not Validated the Remaining Three

We found that two of the five mental health screens included in the joint SHA are validated screening tools, based on our analysis of selected scientific research, interviews with subject matter experts, and clinical practice guidelines. We also found that VA and DOD have not validated the other three mental health screens included in the joint SHA, meaning that their effectiveness and reliability are unknown. VA and DOD based two of the joint SHA’s mental health screens on validated tools but made modifications to those screens that have not been validated. The remaining screen, on violence risk, is not based on a validated screening tool. See figure 1.

Figure 1: The Joint Separation Health Assessment’s Mental Health Screens, and the Extent to Which They Are Based on Validated Screening Tools

Note: VA and DOD based the joint assessment’s alcohol use and post-traumatic stress disorder screens on validated tools but modified the screening questions and have not re-validated them to confirm that they effectively and reliably identify those with or without the condition in question.

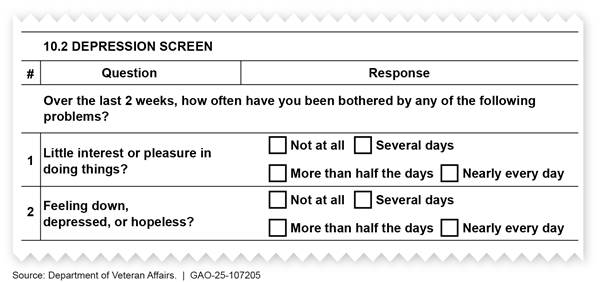

Depression screen. Through our analysis of selected research, we found that the joint SHA uses a validated tool—the Patient Health Questionnaire-2—to screen for depression. Researchers developed the two-question screen, which has been validated for use with the general population. See figure 2.

Note: Kurt Kroenke, Robert L. Spitzer, and Janet B. W. Williams developed the Patient Health Questionnaire-2.

VA and DOD’s joint clinical practice guideline for depression identifies and recommends the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 as an initial screening tool for the general population.[36] This approach is supported by the scientific research we reviewed—including a meta-analysis of 40 studies—which found that the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 performs well as an initial screening step in primary care.[37]

There are several versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire—including a version with nine questions—and the experts we interviewed varied on which version of the questionnaire they considered to be the most appropriate screening tool for the joint SHA.[38] Multiple experts cited tradeoffs between the amount of information gathered and screening length in their rationale for why one screening tool may be more appropriate than the other. For example, the longer version of the tool may contribute to screening fatigue, but it also covers additional risk factors such as sleep disturbance and suicide risk, according to experts.

SHA Working Group officials told us that they consider the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 to be a sufficient screening tool for the joint SHA and therefore did not consider using the nine-question version. The officials noted that the nine-question version of the tool can be administered to a service member who screened positive on the two-question version as part of a more comprehensive assessment. The departments’ clinical practice guidelines also recommended the subsequent use of the nine-question version as follow-up for those who screen positive.[39] Our review of selected research supports the utility of this approach to reduce clinician burden.[40]

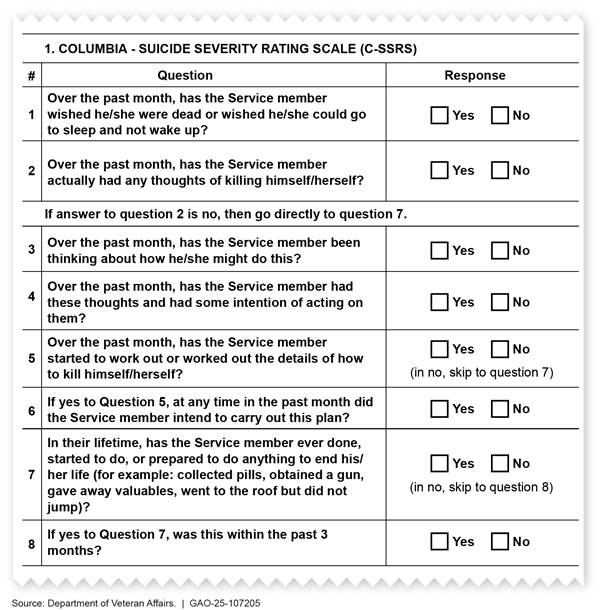

Suicide risk screen. VA and DOD selected the Columbia – Suicide Severity Rating Scale to screen for suicide risk on the joint SHA. See figure 3. Researchers developed the Columbia scale, which is validated for use with veterans. One study that we examined showed that the Columbia scale “consistently predicts future suicidal behavior” in veteran populations, particularly those believed to be at risk for suicide.[41]

Note: Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Pittsburgh developed the Columbia - Suicide Severity Rating Scale with support from the National Institute of Mental Health.

While the Columbia scale is the standard of care for suicide risk screening, suicide risk itself is not well understood, according to some experts we interviewed and research we reviewed. Two experts we consulted said that clinical and scientific understanding of how to detect suicide risk is limited. Our review of selected research substantiated these limitations and identified research that questioned the effectiveness of suicide risk screening tools overall. While we found evidence of the Columbia scale’s validity in specific populations, research on the tool’s validity, particularly across a diverse veteran population, remains limited. For example, one article we reviewed found that the screen performs well at identifying veterans with high risk of suicide but is less effective at ruling out veterans with low risk, resulting in false positives.[42] However, the experts we interviewed did not identify any other suicide risk screening tools that they would recommend using instead of the Columbia scale.

Our review of relevant clinical practice guidelines and interviews with experts found that the Columbia scale is considered the standard of care for suicide risk screening. The American Medical Association, the Joint Commission, and VA and DOD clinical practice guidelines recommend using the Columbia scale when screening for suicide risk.[43] Most subject matter experts we consulted all recognized the Columbia scale as the best tool available for suicide risk screening and agreed that it is appropriate for the joint SHA.

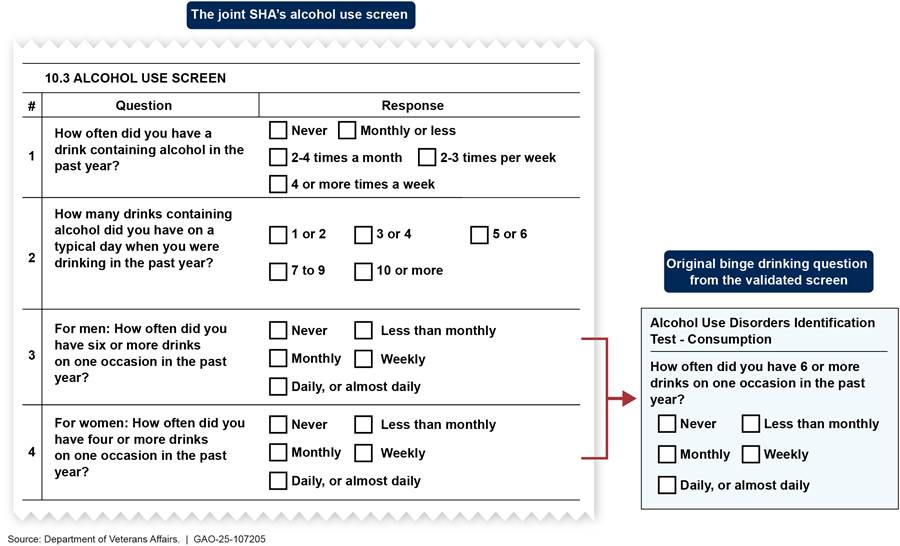

Alcohol use screen. We found that the joint SHA’s alcohol use screening questions are based on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption, which researchers developed and validated. VA and DOD’s clinical practice guidelines recommend using this tool to screen for unhealthy alcohol use.[44] The subject matter experts we interviewed recognized this screen as validated and widely used.

However, for the joint SHA, the SHA Working Group used a modified version of the original validated tool’s binge drinking question to differentiate the number of drinks by sex (now questions three and four) and have not validated the changes. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption does not differentiate these questions by sex. See figure 4.

Figure 4: Alcohol Use Screening Questions in the Joint Separation Health Assessment (SHA) Compared with the Validated Screen

Notes: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption consists of three questions and only diverges from the joint SHA’s alcohol use screening questions on the binge drinking question.

Kristen Bush, Daniel R. Kivlahan, Mary B. McDonell, Stephan D. Fihn, and Katharine A. Bradley developed the validated screen with support from the Department of Veterans Affairs, the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute, and the Department of Veteran Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System.

SHA Working Group officials told us that VA and DOD have used the modified version of the alcohol screening in clinical practice since 2020. They shared one study with GAO to support their use of a sex-tailored binge drinking question.[45] We reviewed the study, as well as an additional study cited within it, and found that the studies provided limited empirical support for the decision to use a sex-tailored screening.[46] Further, these studies tested versions of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption screen that are inconsistent with the joint SHA’s alcohol use screen’s language and scoring protocol.

|

Differing Binge Drinking Definitions for Men and Women Federal agencies, including the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism define binge drinking differently for men and women. For example, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which conducts the annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health, defines binge drinking as five or more drinks containing alcohol for males or four or more drinks containing alcohol for females on the same occasion (i.e., at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) on at least 1 day in the past month. Source: GAO analysis, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. | GAO‑25‑107205 |

SHA Working Group officials said that there were no plans to determine the validity of the specific sex-tailored binge drinking question used in the joint SHA. According to the American Psychological Association, screenings must be assessed to ensure they meet the criteria for acceptable psychological tests and serve their intended purpose.[47] The results of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption screen’s validity studies would not be directly applicable to the joint SHA’s modified version of the screening tool, as research shows that a modified screening tool should be assessed for its reliability and validity.[48] Further, VA and DOD recommend using a validated screen, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption, in their own clinical practice guidelines.[49]

Without validation, the modified screening tool’s clinical validity and reliability are unknown. That is, without validation, it is unknown how effective the tool is in identifying those who are and are not at risk for alcohol misuse or dependence, and whether the screening tool would yield consistent results.[50] Validation may help the departments learn more about how alcohol use in the active-duty and veteran populations differ by sex. The results of the validation study could lead the departments to make further modifications to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of the screening.[51]

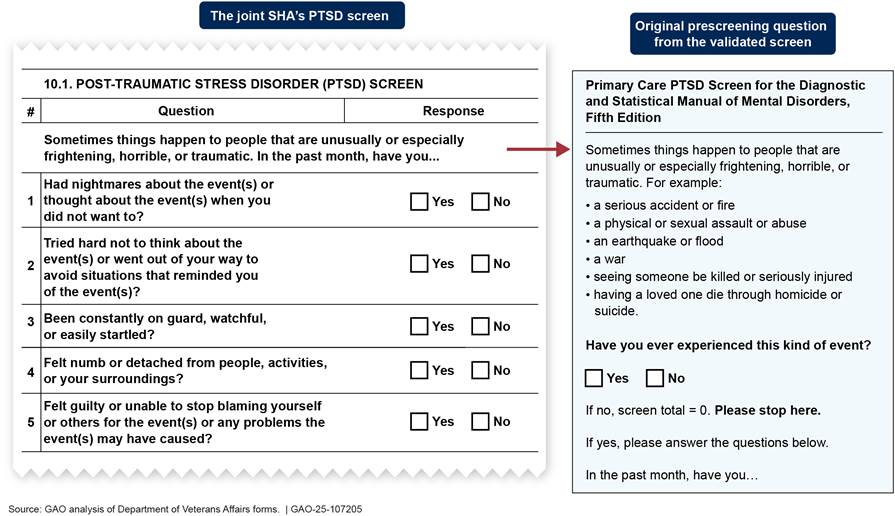

PTSD screen. The SHA’s PTSD screening questions are based on the Primary Care PTSD Screen for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5. VA’s National Center for PTSD developed the screening tool, which has been validated for use with veterans.[52] Our review of selected scientific research found evidence that this is an effective tool for use among veterans seeking health care in primary care settings. However, the populations examined in these studies primarily included older, male veterans, which may limit the generalizability of their findings to a younger and more diverse population separating from military service.[53] Many of the subject matter experts we interviewed noted that the tool is the standard of care for PTSD screening and is widely used. Further, VA and DOD’s clinical practice guideline recommends using this validated tool when screening for PTSD.[54]

However, the SHA Working Group modified the PTSD screen for the joint SHA, and the revised screen has not been validated. Specifically, the group omitted an initial prescreening question asking whether the respondent has had any lifetime exposure to traumatic events. In the validated PTSD screen, if a respondent reported that they had never experienced a traumatic event, the screening would be complete, and the respondent would screen negative. See figure 5.

Figure 5: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Screening Questions in the Joint Separation Health Assessment (SHA) Compared with the Validated Screen

Note: The joint SHA’s PTSD screen includes the same language as the Primary Care PTSD Screen for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition for questions one through five. The Department of Veterans Affairs’ National Center for PTSD developed the validated screen.

SHA Working Group officials were not aware of why the initial prescreening question was omitted on the joint SHA’s PTSD screening tool. They also told us that they have no plans to validate the modified screening tool. SHA Working Group officials acknowledged that the modifications made to the validated PTSD screen could affect the tool’s outcomes. The officials stated that experts at VA’s National Center for PTSD informed them that the modifications may increase the number of false positives and decrease the number of false negatives.[55] However, the exact impacts of the modifications are not fully known without validation.

As noted previously, research shows that once a screening tool is modified, the new version should be assessed for its reliability and validity. Without validation, the clinical validity and reliability of the modified PTSD screening tool are unknown. Using an already validated tool, such as the version of the screen recommended in VA and DOD’s clinical practice guidelines, or conducting a study to assess the validity and reliability of the joint SHA’s modified tool would help VA and DOD to ensure more accurate PTSD screening results.[56] Otherwise, there may be unknown consequences of false positive or negative outcomes. For example, service members who have a false positive screen may worry that they have PTSD when they do not.

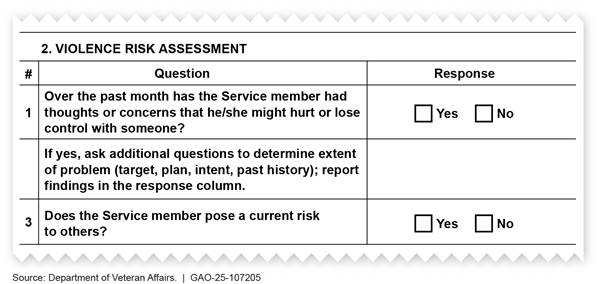

Violence risk screen. We found that the joint SHA’s violence risk screening questions are not based on a validated tool. The SHA Working Group identified the violence risk questions in its review of existing health assessment forms and recommended them for inclusion in the joint SHA for consistency with other DOD forms.[57] These officials were not aware of the violence risk questions’ origin or DOD’s rationale for including violence risk screening in these other health assessments.[58] See figure 6.

Multiple experts we interviewed expressed concerns about the effectiveness of the joint SHA’s violence risk screening questions, although opinions varied. For example, experts from one medical specialty organization found the questions subjective and vague, which they argued would create more need for clinical inquiry and judgement with little guidance. In another interview, one expert shared that the violence risk screening as written would be insufficient to determine whether the service member is at risk for hurting others. However, a third expert believed that the SHA’s violence risk questions were reasonable, as they cover known epidemiologic risk factors for violence.

Research shows that conditions such as PTSD, alcohol and drug use disorders, and head injuries are linked to increased risk of violence in veterans.[59] Further, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that violence perpetration is a risk factor for suicide.[60] Therefore, violence risk screening may be useful for this population.

Our review of selected research and clinical practice guidelines yielded one study that proposed an evidence-based violence risk screening tool for the veteran population—the Violence Screening and Assessment of Needs tool.[61] It had undergone an initial round of validation with veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. This tool applies a different set of screening questions than those currently included in the joint SHA. It has five questions, each based on a risk factor associated with violence identified in research—financial instability, combat experience, alcohol misuse, a history of violence or arrests, and probable PTSD plus anger. SHA Working Group officials said that they did not consider including this tool in the joint SHA. They noted limitations of this tool including that its question topics do not directly inquire about risk of violence against others and are largely redundant with what is already included in the joint SHA. They also noted that this tool would require additional validation testing prior to implementation due to the limited establishment of its psychometric properties, such as its reliability and sensitivity.

Concerns about the current, unvalidated tool along with the limitations of the additional tool we identified raise questions about the departments’ inclusion of violence risk screening in the joint SHA. Assessing whether to include such a screen would help VA and DOD ensure the effectiveness of their pre-separation screening approach. If the departments confirm that violence risk screening is warranted, then validation is necessary to ensure that the tool the departments use can effectively identify those who are and are not at risk of perpetrating violence and yield consistent results. Without it, the effectiveness and reliability of the violence risk screen’s questions are unknown. The departments could use a systematic screening development and validation process to ensure the clinical validity and reliability of their violence risk screening questions. For example, the departments could conduct a scientific study based on the existing screening questions, or alternatively, conduct additional testing on the Violence Screening and Assessment of Needs tool. Including a validated violence risk screening tool in the joint SHA would help to ensure that those separating service members most in need of assistance are identified and can be offered the support they need, potentially preventing violent outcomes.

Two-Thirds of Service Members Screened Positive on at Least One Mental Health Screen During VBA’s Joint SHA Exams

PTSD and Depression Have Been VBA’s Most Common Positive Mental Health Screens for the Joint SHA

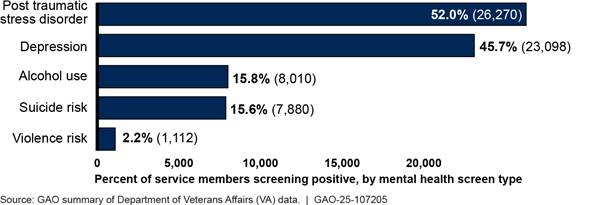

Between May 2023 and April 2024, VBA data show that its contractors administered about 50,500 joint SHAs for service members being evaluated for disability benefits. Of those exams, 67 percent of service members had at least one positive mental health screen, with PTSD and depression being the most common positive screens.[62] See figure 7. Each of the joint SHA’s five mental health screens have different scoring criteria for what is considered positive. For example, a “yes” response to three or more of the PTSD questions is considered a positive screen while a “yes” response to any suicide risk screening question is considered positive.

Figure 7: Summary of Joint Separation Health Assessment (SHA) Mental Health Screening Conducted by Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) Contractors from May 2023 Through April 2024

Notes: The data in this table come from SHA exams completed by VBA contractors and returned to VBA from May 2023 through April 2024, based on data extracted May 29, 2024.

VBA officials noted that because a service member can screen positive for more than one mental health indicator, the positive mental health screens by type do not sum to the total number of service members with positive mental health screens (33,814).

VA and DOD SHA Working Group officials told us that these screening rates are higher than would be expected in a clinical setting or based on population prevalence for these disorders. It is possible that the modifications VA and DOD made to the alcohol use and PTSD screening tools contributed to those higher positive screening rates. Nonetheless, officials said that they were not surprised that PTSD and depression were the most common positive mental health screens as they are the two most prevalent service-connected mental health conditions.[63]

|

Tracking the Results of Mental Health Screening during Joint Separation Health Assessments In February 2024, the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) began requiring its contractors that conduct joint Separation Health Assessment (SHA) exams to report data monthly on service members with positive mental health screenings and any resulting referrals to the Department of Defense’s (DOD) inTransition program. VBA officials told us these data are collected to ensure contractual compliance that any service member with one or more positive mental health screens—or for any other mental health need identified—is offered a referral to DOD’s inTransition program. VBA officials told us in January 2025 that they planned to begin sharing the monthly contractor data with DOD by spring 2025. Source: GAO summary of VBA information. | GAO‑25‑107205 |

DOD officials said that there are many reasons why this population of separating service members may have higher positive screening rates, including the timing of these assessments and the stress associated with leaving the military. Further, SHA Working Group officials noted that even if service members aren’t applying specifically for mental health disability benefits, the intent to file a disability claim could still increase the possibility of positive mental health screens. For example, these officials said that it is reasonable to assume that service members understand that the results of the joint SHA will be used to determine eligibility for financial benefits.[64] For these reasons, SHA Working Group officials told us that they expect the rates of positive mental health screens will be higher for service members who are applying for VA disability benefits than those who are not.[65]

VBA Requires inTransition Referral Offers for Those with Positive Mental Health Screens and Additional Actions for Those at Risk for Suicide

When a service member scores positive on any of the joint SHA’s mental health screens, VBA contractors’ examining clinicians are to ensure they are aware of available mental health care options and offer a referral to DOD’s inTransition program. These requirements are noted in the clinical assessment portion of the SHA, as well as accompanying VA guidance. Specifically, the guidance notes that upon identifying one or more positive mental health screens during the SHA exam, examining clinicians are to inform service members about DOD’s inTransition program and ascertain verbal consent to make a referral on their behalf. If a service member does not consent to an inTransition referral, the guidance notes that the examining clinician should still provide the service member with contact information for inTransition.[66]

Overall, of those service members who were offered an inTransition referral as part of the joint SHA exam—since it was implemented by VBA—nearly equal numbers accepted and declined the referrals, according to VBA data. See figure 8.

Figure 8: Disposition of Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) Contractors’ Referral Offers to the Department of Defense’s (DOD) inTransition Program During Separation Health Assessments, May 2023 Through April 2024

Note: Per the clinical assessment portion of the joint Separation Health Assessment (SHA), service members who score positive on one or more of the mental health screenings are required to be offered a referral to DOD’s inTransition program. VBA officials said that inTransition referrals can also be made based on other mental health concerns identified during the joint SHA exam (e.g., eating disorders, insomnia, anxiety). In addition to the service members above who were offered an inTransition referral, VBA officials told us that when they extracted these data for us, they observed that there were 50 joint SHA forms for which the inTransition referral information was not completed correctly. Officials said that they addressed this issue with the appropriate contractor in May 2024 and had seen no further instances of this error.

VBA does not track service members’ reasons for declining an inTransition referral. However, VBA officials noted several reasons that a service member might decline, including that these service members are already involved in some type of mental health treatment. Officials said that they did not have concerns about the number of service members declining inTransition referrals. The officials said that requiring an individual to participate in a program is not always therapeutic or effective. They said that it is more important that all service members who screen positive be informed about the inTransition program and provided its phone number.

VBA contractors are required to take additional actions for service members with identified suicide risk, depending on their risk level.[67] VBA contractors’ examining clinicians are provided with additional guidance related to determining an individual’s level of suicide risk, which notes that clinicians are to use judgement in their assessment. The suicide risk screening tool used in the SHA does not differentiate between levels of suicide risk. Instead, VA officials said that examining clinicians make this determination based on the SHA interview and other data available to them. Depending on the clinician’s assessment of the service member’s risk, the VBA guidance lists required and suggested actions to take, as appropriate. See figure 9.

Figure 9: Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) Guidance on Actions to Take Based on Level of Risk for Suicide as Determined During Separation Health Assessments

Note: The suicide risk screening tool used in the joint Separation Health Assessment (SHA) does not differentiate between levels of suicide risk. Instead, Department of Veterans Affairs officials said that examining clinicians make this determination based on the joint SHA interview and other data available to them.

|

The Veterans Crisis Line and Separation Health Assessments Examining clinicians are required to contact the Veterans Crisis Line for service members identified with elevated suicide risk during a joint Separation Health Assessment exam. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) officials said if a clinician called the crisis line during the exam, a crisis responder would collect the information necessary to best assist the caller and the service member. VA officials said the Veterans Crisis Line reviews all requests to determine the most effective way to provide necessary support. For example, crisis responders may assist with facilitating same-day emergency mental health care or facilitating dispatch of emergency services with the examining clinician or the service member. If the service member is in crisis but not at imminent risk for injury or suicide, then the responder will listen, offer support, and help make a plan to stay safe. While speaking with the service member, the crisis responder will also offer to submit a request to the local suicide prevention coordinator for additional support and resources. Source: GAO summary of VA information. | GAO‑25‑107205 |

In addition to the steps detailed in figure 9, if an examining clinician determines that a service member is at intermediate or high acute risk for suicide, they are also required to: (1) document the risk level and subsequent actions taken in the SHA form and (2) submit an incident report to VBA, among other things. Officials said that the report informs VBA about the incident and documents the actions the clinician took so that they can ensure contractual requirements were followed.

Although its contractors must follow the joint SHA’s screening protocols for referrals and assistance, VA officials told us that because the service members being screened are still on active duty, DOD is responsible for ensuring any necessary follow-up care. They noted that the joint SHA exams completed by its contractors do not have a VA clinical follow-up component. Further, VA officials explained that they use the joint SHA exam to assess eligibility for disability benefits and not for providing treatment recommendations.

Conclusions

Given concerns about the risk of suicide and other mental health challenges following service members’ separation from military service, it is essential that they receive effective mental health screening prior to separation. Such screening can lead to the early identification of individuals potentially at high risk and help direct them to further assessment, treatment, and intervention. By incorporating mental health screening into the departments’ joint SHA, VA and DOD have taken a step toward better identifying those separating service members at risk for mental health concerns.

However, VA and DOD modified two of the five mental health screens used in the joint SHA without validating the changes, and another mental health screen is not based on a validated tool. Without validation testing, VA and DOD cannot be sure about the effectiveness or reliability of the screening they are conducting for alcohol use, PTSD, and violence risk. Validating the screening questions they are using—or using already validated screening tools—would provide greater assurance that the departments’ screening is effective in identifying service members in need of mental health support at separation.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of three recommendations to the VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee:

The VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee should ensure that the joint SHA’s alcohol use screen is validated. This could include taking steps to validate the joint SHA’s existing screen or replacing it with an already validated one. (Recommendation 1)

The VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee should ensure that the joint SHA’s PTSD screen is validated. This could include taking steps to validate the joint SHA’s existing screen or replacing it with an already validated one. (Recommendation 2)

The VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee should assess whether to include violence risk screening in the joint SHA and take appropriate action based on this assessment. Possible actions could include taking steps to validate the joint SHA’s existing questions, replacing them with a different validated tool, or removing the questions, as appropriate. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to VA and DOD on March 14, 2025, and asked the departments for their comments within 30 days. VA provided written comments on May 8, 2025, and DOD provided written comments on April 17, 2025.[68] These comments are reprinted in appendixes I and II, respectively, and summarized below. DOD also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

VA concurred with our three recommendations and described actions it would take to address them. For each recommendation, VA stated that the Joint Executive Committee’s SHA Working Group would collaborate with various DOD and VA components to assess the screens for alcohol use, PTSD, and violence risk. VA estimated that these efforts would be completed by December 31, 2025.

In its comments, DOD partially concurred with each of our three recommendations. DOD stated that it appreciated the recommendations to use validated screening tools. However, DOD suggested we modify the recommendations to direct the SHA Working Group, which includes clinical and non-clinical health and transition experts, to “explore using” validated screens for alcohol use, PTSD, and violence risk in the joint SHA. DOD further stated that the VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee will direct the SHA Working Group to bring recommendations to the committee for decisions on whether any modifications are needed to these screens by the first quarter of fiscal year 2026.

DOD’s suggested changes weaken the intent of our recommendations because they do not ensure the use of validated screening tools. While we agree that the VA-DOD Joint Executive Committee may delegate responsibility for implementing our recommendations as appropriate, we directed our recommendations to the Committee because it is the entity with the authority to implement our recommendations. As discussed in our report, it is important that any mental health screening tools used in the joint SHA be validated. Doing so does not necessarily require that VA and DOD conduct any additional validation testing. For alcohol use and PTSD, for example, validated screening tools already exist and could replace the modified and unvalidated versions currently used in the joint SHA.

Given the joint nature of the SHA, it will be important for the two departments to collaborate in addressing our recommendations. Whatever option the departments choose for each of the three screens, it is important that VA and DOD use validated screening tools to help ensure that service members receive effective and reliable mental health screening at separation.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, the Secretary of Defense, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at hundrupa@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Alyssa M. Hundrup

Director, Health Care

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Jerry Moran

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Blumenthal

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mike Bost

Chairman

The Honorable Mark Takano

Ranking Member

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

House of Representatives

GAO Contact

Alyssa M. Hundrup at HundrupA@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Bonnie Anderson (Assistant Director), Christina Ritchie (Analyst in Charge), Adrienne Bober, and Phillip Steinberg made key contributions to this report. Also contributing to this report were Joycelyn Cudjoe, Ying Hu, Eric Peterson, Roxanna Sun, and Jennifer Whitworth.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]DOD separation data include active-duty service members from the Army, Air Force, Marines, Navy, and Coast Guard. They also include Reserve and National Guard separations from active duty greater than 180 days or on contingency operations orders over 30 days.

[2]See Yu-Chu Shen, Jesse M. Cunha, Thomas V. Williams, “Time-Varying Associations of Suicide with Deployments, Mental Health Conditions, and Stressful Life Events Among Current and Former U.S. Military Personnel: A Retrospective Multivariate Analysis,” Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 3, no. 11 (2016):1039-1048, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30304-2. This study showed that the suicide rate remained about 2.5 times higher for veterans in the first 3 years of separation compared with the active-duty population. This risk for death by suicide can remain elevated for years following the transition period.

[3]Exec. Order No. 13822, 83 Fed. Reg. 1,513 (Jan. 12, 2018). The Executive Order also identifies the Department of Homeland Security as a partner in the joint action plan.

[4]DOD’s joint SHA pilot included three military medical treatment facilities—one each at Army, Navy, and Air Force bases. The pilot was completed in January 2025.

[5]H.R. Rep. No. 118-125, at 194-95 (2023).

[6]A validated screening tool is an instrument that has been assessed and determined to effectively and reliably identify individuals exhibiting symptoms of the given mental health condition it purports to measure.

[7]For the targeted literature search, we conducted a search for relevant literature published in scholarly journals and other reports between 2014 and 2024. We used the ProQuest, EBSCO, SCOPUS, and DIALOG databases, and search terms such as “valid*,” “reliab*,” “accura*,” “sensitive*,” or “specific*” and the names or topics of the joint SHA’s mental health screens. Given the volume of literature returned in an initial test search, we conducted two searches: one that required terms such as “literature review*” or “meta-analysis”,” and another that limited the results to those that included search terms such as “military,” “veteran,” or “service member*.” We then selected the articles that were most relevant to our analysis.

[8]Psychometric properties are characteristics of psychological tests that indicate the strength of a measurement tool. Psychometric properties, such as reliability (the ability of the instrument to provide consistent results), sensitivity (the ability of the instrument to correctly identify individuals with the condition), and specificity (the ability of the instrument to correctly identify individuals without the condition), can be used to establish the overall validation of a screening tool.

[9]The American Psychiatric Association is a professional association that represents psychiatrists and promotes high quality care for those affected by mental disorders, among other activities. The American Psychiatric Nurses Association is a professional association that represents psychiatric-mental health nurses and whose mission includes shaping health policy for the delivery of mental health services.

[10]The American Medical Association is a professional association that represents physicians and promotes the art and science of medicine and the betterment of public health.

[11]10 U.S.C. § 1145(a)(5)(A) and DoDI 6040.46, “The Separation History and Physical Examination (SHPE) for the DOD Separation Health Assessment (SHA) Program,” April 14, 2016. Separation exam requirements apply to active-duty service members separating from the Army, Air Force, Marines, Navy, Coast Guard, and National Guard. They also apply to Reserve Component separations after 180 days or more on active-duty orders, or those separating after more than 30 days of active-duty service in support of a contingency operation. When we refer to “service members” throughout this report, we are referring to those service members who are required to have a separation health exam.

[12]We issued a report in November 2004 about some of these efforts. See GAO, VA and DOD Health Care: Efforts to Coordinate a Single Physical Exam Process for Servicemembers Leaving the Military, GAO‑05‑64 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 12, 2004).

[13]Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense, Implementation of Cooperative Separation Process/Examinations for the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs at Benefits Delivery at Discharge sites, Memorandum of Agreement between Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (November 17, 2004).

[14]Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense, Implementation of Separation Health Assessments for separating/retiring Service members by the Department of Defense and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Memorandum of Agreement between Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (December 3, 2013).

[15]Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense, Memorandum of Agreement between Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense Concerning Separation Health Assessments (January 24, 2022). The 2022 memorandum of agreement also states, for example, that as part of the separation exam, additional or specialty examinations will be ordered as clinically indicated.

[16]Of the 59,351 separation exams VBA reports that it completed in fiscal year 2023, 35,107 were for service members filing a claim for disability benefits through the Benefits Delivery at Discharge program, and 24,244 were for service members being evaluated through the Integrated Disability Evaluation System.

[17]According to the SHA Memorandum of Agreement between VA and DOD, the examining clinicians who conduct SHA exams are to be licensed physicians, physician’s assistants, or nurse practitioners with credentials and privileges to perform a full scope examination.

[18]The rest of the exams were conducted by Veterans Health Administration medical centers. Specifically, VBA reported that 0.3 percent and 0.2 percent of separation exams were completed by the Veterans Health Administration in fiscal years 2023 and 2024, respectively. For the purposes of this report, we refer to these exams as being completed by VBA contractors.

[19]See 38 U.S.C. § 320.

[20]See, for example, Brian C. Kok, Richard K. Herrell, Jeffrey L. Thomas, Charles W. Hoge, “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Associated With Combat Service in Iraq or Afghanistan: Reconciling Prevalence Differences Between Studies,” The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, vol. 200, no. 5 (May 2012): 444-450, https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0b013e3182532312; and, Lisa K. Richardson, B. Christopher Frueh, Ronaldo Acierno, “Prevalence Estimates of Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Critical Review,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 44, no. 1 (2010): 4-19, https://doi.org/10.3109/00048670903393597.

[21]Anne M. Gadermann, et al., “Prevalence of DSM-IV Major Depression Among U.S. Military Personnel: Meta-Analysis and Simulation,” Military Medicine, vol. 177, issue suppl. 8 (August 2012): 47-59, https://doi.org/10.7205/milmed-d-12-00103.

[22]See Daniel J. Lee, et al., “A Longitudinal Study of Risk Factors for Suicide Attempts Among Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom Veterans,” Depression and Anxiety; vol. 35 (2018): 609-618, https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22736; and Nathan A. Kimbrel, Eric C. Meyer, Bryann B. DeBeer, Suzy B. Gulliver, and Sandra B. Morissette, “A 12-Month Prospective Study of the Effects of PTSD-Depression Comorbidity on Suicidal Behavior in Iraq/Afghanistan-era Veterans,” Psychiatry Research, vol. 243 (2016): 97-99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.011.

[23]See, for example, Yousef Moradi, Behnaz Dowran, and Mojtaba Sepandi, “The Global Prevalence of Depression, Suicide Ideation, and Attempts in the Military Forces: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross Sectional Studies,” BMC Psychiatry, vol. 21, no. 510 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03526-2.

[24]The Joint Commission is an organization that accredits health care organizations and issues standards with the goal of improving the quality of patient care and safety. The American Psychological Association is a professional association that represents psychologists and promotes the advancement, communication, and application of psychological science, among other things.

[25]Service members can also self-refer to inTransition, and providers may refer service members to inTransition at other times. Further, all service members leaving military service who have received psychological health care within 1 year prior to their separations are automatically enrolled in the inTransition program. The inTransition program is available to active-duty service members, National Guard members, reservists, veterans, and retirees regardless of time in service, time from service, or characterization of discharge.

[26]In addition to inTransition, DOD and VA have other programs to support separating service members and veterans during the transition period. For example, to assist service members who may be at risk for a difficult transition—including those with mental health needs—DOD, through its Transition Assistance Program, facilitates a person-to-person connection, known as a “warm handover,” to other agencies. Within VA, the Solid Start program connects new veterans with resources and benefits, and it prioritizes outreach to those who received mental health care in the year prior to separation.

[27]According to inTransition documentation, coaches are trained in motivational interviewing, understand military culture, and are knowledgeable in mental health, substance use, and community and military resources. Coaches are to employ interventions that are appropriate for the individual, including assistance with developing an action plan or setting goals; encouragement with the use of adapting strategies; responses to mental health questions related to diagnosis or life issues; self-management materials; decision support for treatment options; and encouragement to make healthy choices to support well-being.

[28]See GAO, DOD and VA Health Care: Actions Needed to Better Facilitate Access to Mental Health Services During Military to Civilian Transitions, GAO‑24‑106189 (Washington, D.C.: July 15, 2024).