BROADBAND PROGRAMS

Agencies Need to Further Improve Their Data Quality and Coordination Efforts

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107207. For more information, contact Andrew Von Ah at vonaha@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107207, a report to congressional requesters

Agencies Need to Further Improve Their Data Quality and Coordination Efforts

Why GAO Did This Study

Access to broadband is critical for employment, education, health care, and other daily activities. Yet millions of Americans lack broadband access, despite at least $44 billion in federal investment over the past decade across myriad programs managed by different agencies. Information on where broadband is not available is key to expanding access.

GAO was asked to review federal broadband efforts. This report examines (1) agencies’ use of broadband availability information and the extent to which FCC ensures the quality of data in its National Broadband Map; and (2) the extent to which agencies’ coordination of broadband funding programs aligns with GAO’s leading practices for interagency collaboration, among other issues.

GAO reviewed documents and interviewed officials from FCC and other broadband funding agencies. GAO compared (1) FCC’s practices for ensuring the quality of information in its National Broadband Map against relevant federal internal control standards and (2) interagency coordination efforts with leading practices for interagency collaboration.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 14 recommendations, including that FCC document and evaluate the effectiveness of its processes for ensuring the quality of the National Broadband Map’s data, and that FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury clearly define and document certain aspects of their coordination. FCC, NTIA, and Treasury agreed with GAO’s recommendations; USDA neither agreed nor disagreed.

What GAO Found

Federal agencies rely on the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) National Broadband Map as a key information source to target tens of billions of dollars in federal broadband funding by knowing where high-speed internet is already available. However, the accuracy of the broadband availability data on the map is uncertain. FCC has not documented or assessed the sufficiency of its processes for ensuring the information’s accuracy. Without taking these steps, FCC cannot be assured its processes are sufficient to ensure the data’s quality or that its staff are carrying out these processes consistently, increasing the risk that inaccurate data appear on the map. Inaccurate data could jeopardize agencies’ ability to make the most efficient and effective funding decisions.

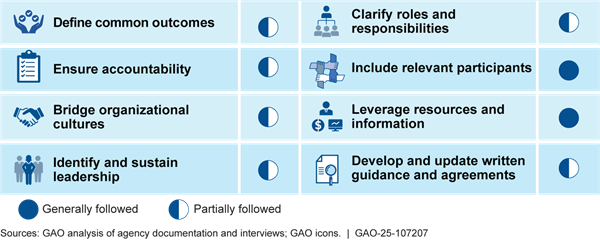

FCC, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), and the Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and the Treasury coordinate with each other to administer the bulk of federal funding for broadband deployment. GAO found that coordination efforts between these agencies generally followed two and partially followed six of eight leading collaboration practices (see figure).

Assessment of Interagency Coordination Efforts to Administer Federal Broadband Funding Compared with Leading Practices for Interagency Collaboration

In particular, the agencies use various coordination methods, including regularly meeting and leveraging maps to share data to help avoid duplicate funding. The agencies also have some written agreements to guide coordination, such as an information-sharing memorandum. However, GAO found areas where the agencies have not clearly documented the scope of how coordination efforts will be implemented. For example, they have not clearly defined or documented key areas of their collaborative efforts, such as what “covered data” include when sharing information about their broadband deployment projects, as referenced in the memorandum. The agencies also have not established timelines for providing data on funded projects to the map used to display information on federally funded broadband projects, or documented a formal process for avoiding duplicate funding. Clearly defining, agreeing upon, and formally documenting guidance would better position the agencies to sustain their collaborative efforts, especially should changes in leadership or staff occur. It would also help ensure that billions of dollars in federal funding are spent efficiently and effectively to expand broadband access, including to areas with the greatest need.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

|

BEAD |

Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program |

|

CPF |

Capital Projects Fund |

|

FCC |

Federal Communications Commission |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

MOU |

memorandum of understanding |

|

NTIA |

National Telecommunications and Information Administration |

|

SLFRF |

State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund |

|

TBCP |

Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

April 17, 2025

The Honorable John Thune

Majority Leader

United States Senate

The Honorable Ben Ray Luján

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Telecommunications and Media

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

Broadband, or high-speed internet, is increasingly considered essential for employment, education, health care, and other activities in Americans’ daily lives. Nevertheless, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) reported that as of 2022, fixed broadband was unavailable to approximately 24 million Americans, despite at least $44 billion in federal investment from fiscal years 2015 through 2020.[1] To help bridge the “digital divide”—that is, the gap between those with and without access to broadband—Congress appropriated tens of billions of dollars in additional federal funding since 2020 for programs to support expanding broadband access. In particular, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act appropriated nearly $65 billion for new and existing broadband programs.[2] However, increasing access to broadband remains an ongoing national challenge.

To effectively administer federal broadband funding, we have previously reported that federal agencies need to have a precise understanding of where broadband is already available, including location-specific characteristics of the service (e.g., speeds, internet service providers, and technology types), to target funds to areas with the greatest need.[3] However, we and others have reported that, historically, FCC data—the primary source of broadband availability information—overstated existing service.[4] In 2022, FCC launched its National Broadband Map as part of efforts to improve information on broadband availability.

In 2022, we inventoried federal programs that either must or can be used to support expanding broadband access, identifying more than 100 administered by 15 federal agencies, and documented the varied ways in which agencies coordinate to administer programs.[5] While many agencies provide funding to support broadband access, FCC, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration within the Department of Commerce (NTIA), and the Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and the Treasury administer the bulk of federal funding for deployment of new or enhanced broadband networks.

We have also reported that the role of states and territories in distributing federal broadband funds has increased in recent years with the creation of new programs that provide funds directly to them.[6] For example, the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program (BEAD) provides approximately $42 billion to expand broadband access in all states and territories. Additionally, Treasury’s Capital Projects Fund (CPF) is a $10 billion grant program available to states and territories, among other entities, that may be used for broadband infrastructure projects.

You asked us to review issues related to federal broadband programs.[7] This report examines (1) the sources of broadband availability information selected agencies use and the extent to which FCC ensures the quality of data in its National Broadband Map; (2) the extent to which selected agencies’ efforts to coordinate their administration of broadband funding programs align with our leading practices for interagency collaboration; and (3) how selected agencies have coordinated with state and territory governments regarding broadband funding, and those governments’ perspectives on that coordination.

To address these objectives, we focused on the four agencies specified above that administer the bulk of federal broadband funding and have formally agreed to coordinate and share data on broadband derived from their programs: FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury. We focused on activities undertaken by these agencies since 2022, when we last reported on federal broadband programs broadly.[8] When reviewing their activities, we also focused on those programs whose main purpose is to fund broadband deployment and, among those deployment programs, those that had funds yet to distribute at the time of our review.[9] We also included Treasury’s CPF and State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) programs in our review due to the significant amount of funds being used for broadband investment, although funding broadband is only one possible purpose of these programs.

To address our first objective, we reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury. For example, we reviewed program documentation to identify the sources of broadband availability information the agencies use when making funding decisions and other applicable documentation related to this information, such as data collection and review processes. To evaluate FCC’s efforts to ensure the quality of the availability information in its National Broadband Map, we compared FCC’s practices against relevant internal control standards related to monitoring controls and documenting responsibilities in policies.[10]

To address our second objective, we reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury. For example, we reviewed coordination-related documents, such as interagency agreements and memorandums. We compared the agencies’ coordination mechanisms and activities against the eight leading practices for interagency collaboration identified in our prior work.[11]

To address our third objective, in addition to reviewing documentation and interviewing officials from FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury, we surveyed all states and territories. Specifically, to obtain their views on the four agencies’ efforts to coordinate with them, we conducted a web-based survey of all state and territory broadband offices from August 8, 2024, through November 14, 2024. Fifty-one of 56 state and territory broadband offices completed our online questionnaire, which consisted of closed- and open-ended questions. We analyzed the responses to these questions using both quantitative and qualitative methods to produce summary statements, as well as to identify illustrative examples for reporting purposes.

Finally, to obtain additional information on all our objectives, we reviewed applicable statutes and agency program documentation, such as notices of funding opportunities. To gather additional perspectives, we interviewed representatives from 10 stakeholder organizations selected to obtain a variety of viewpoints from a cross-section of stakeholder interests. These views are not generalizable to those of all stakeholders, though they provided us with a variety of perspectives. Appendix I provides additional information on our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Over a dozen federal agencies play a role in funding broadband, with some agencies administering programs that support broadband as their main purpose and others as one possible purpose. Aside from funding broadband deployment, some of these programs support other aspects of broadband access, such as making service affordable, providing devices, and building digital skills. See appendix II for additional information on the federal programs whose main purpose is to fund broadband deployment.

The four agencies that administer most of the broadband deployment funding vary in both the amount of support they provide and their focus areas. Specifically:

FCC. FCC’s Universal Service Fund programs historically have provided the majority of federal broadband funding. The largest component of the Universal Service Fund is the High Cost program, which targets financial support to rural and high-cost areas for the deployment, operation, and maintenance of voice and broadband networks. For example, FCC’s Enhanced Alternative Connect America Cost Model—a recently established mechanism within the High Cost program—will provide approximately $18 billion over 15 years for providers to deploy and maintain qualifying broadband service in locations across the U.S.

Additionally, FCC is responsible for maintaining maps that show where broadband is available and where the federal government has funded a broadband infrastructure deployment project.

· National Broadband Map. FCC launched this map in 2022 in response to requirements in 2020’s Broadband DATA Act. The map displays location-level information on the availability of broadband service throughout the U.S., including mobile coverage.[12] Internet service providers submit broadband availability information through FCC’s Broadband Data Collection twice a year, including the technology type and maximum advertised download and upload speeds they offer at each location. Previously, FCC collected and mapped provider-reported availability data at the census-block level, which resulted in overstated availability.[13] Specifically, as directed by FCC, providers reported an entire census block as served (i.e., broadband is available) even if some locations within that block lacked service. The Broadband DATA Act required that FCC change the way it collects and reports broadband data by directing FCC to collect more granular location-based data to display on its map. In addition, the act required FCC to (1) create a process for entities (e.g., state, local and tribal governments, consumers) to challenge the accuracy of the map and (2) verify information submitted by providers.

· Broadband Funding Map. FCC is also charged with collecting and publishing information on the Broadband Funding Map, which launched in 2023 in response to requirements in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The act also requires federal agencies to report relevant data to FCC for inclusion in the map. This map displays broadband infrastructure deployment projects funded by the federal government that began as early as January 2019. The map can display both completed and ongoing projects.[14]

NTIA. NTIA has two primary responsibilities with respect to federal broadband funding: it serves as the President’s principal telecommunications policy advisor, and it administers its own funding programs. Specifically, NTIA is responsible for advising the President on telecommunications policies pertaining to economic and technological advancement.[15] In addition, the agency administers billions in federal funding appropriated for broadband expansion in recent major legislation. Most notably, authorized in 2021 by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, BEAD provides states and territories with approximately $42 billion to expand broadband access. To receive funding under BEAD, each state and territory is to create a proposal identifying each area in its jurisdiction lacking sufficient access to broadband, after which local governments, nonprofit organizations, and broadband service providers can challenge whether an area is sufficiently served. After adjudicating challenges, the state or territory creates a final proposal that specifies where it will use BEAD funds for broadband deployment projects. These BEAD proposals are commonly referred to as state plans. In addition, NTIA administers the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program (TBCP), which provides approximately $3 billion to, among other things, expand access to and adoption of broadband service on tribal land.[16]

USDA. Within USDA, Rural Utilities Service programs provide funding for infrastructure in rural communities, including telecommunications services such as broadband. For example, the purpose of the ReConnect program is to expand broadband services to rural areas that lack sufficient access by awarding grants and low-interest loans to eligible service providers. In addition, the purpose of the Community Connect program is to help rural communities expand broadband service that fosters economic growth and other benefits.[17]

Treasury. Treasury administers two programs in response to the COVID-19 pandemic that have broadband deployment as one possible use of their funds. Specifically, SLFRF is a $350 billion program available to state, territory, local, and tribal governments to support their response to and recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and whose funds may be used for broadband infrastructure investment.[18] In addition, CPF is a $10 billion grant program that provides funding to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic to states, territories, tribal governments, and freely associated states that may be used for broadband infrastructure projects.[19] Under both programs, recipients, not Treasury, select the individual projects for funding based on program eligibility requirements.

In light of the multiple federal agencies involved in administering federal broadband funding, federal statutes call for interagency coordination regarding broadband deployment. For example, the Broadband Interagency Coordination Act of 2020 directs FCC, NTIA, and USDA to enter into an interagency agreement—which the agencies established in June 2021—to coordinate and share information about funding for new broadband deployment projects under their respective programs.[20] In addition to this interagency agreement, in May 2022, FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that established guidelines for sharing information about broadband deployment funding under their programs.[21]

The ACCESS BROADBAND Act, which was enacted in 2020, also specifies that any agency that offers a federal broadband support program should coordinate with NTIA’s Office of Internet Connectivity and Growth.[22] The act requires that the coordination be consistent with certain goals, such as serving the largest number of unserved locations and ensuring that all residents have access to high-speed broadband.[23] Our prior work found that when more than one federal agency is working on the same broad area of national need, those federal efforts are fragmented, and there is risk of duplication or other inefficiencies.[24]

In addition to federal agencies, states and territories play a role in some federal broadband funding programs. As described above, NTIA’s BEAD and Treasury’s CPF programs provide funding directly to state and territory governments for expanding broadband access. State and territory governments are also eligible entities for USDA’s ReConnect and Community Connect grant programs, though the majority of recent funding through these programs has been awarded to internet service providers and other local entities. Additionally, FCC has engaged with states and territories as part of its outreach efforts to implement its Broadband Data Collection, such as soliciting any early concerns states may have had with the transition to the National Broadband Map from FCC’s previous methods of collecting and mapping broadband availability data.

Moreover, every state and territory has a centralized entity—commonly known as a state broadband office—that manages the state’s overall broadband efforts. NTIA has led efforts to coordinate with states since at least 2009, including through supporting states’ and territories’ creation of these centralized entities. These entities can take different forms and vary in structure, size, and experience. For example, they may be offices, agencies, or task forces within a state’s governor’s office, public utility, or commerce department, or could be a stand-alone state entity. While some states established a state broadband office or like entity decades ago, many states and territories have recently done so as part of BEAD implementation. According to the 2022 BEAD notice of funding opportunity, states and territories are allowed to use BEAD planning funds for establishing, operating, or increasing the capacity of a broadband office that oversees broadband programs and broadband deployment. In addition, to receive BEAD funding, as described above, states and territories are responsible for identifying locations lacking sufficient access to broadband using FCC’s National Broadband Map data and developing their own challenge process.

Agencies Rely on the National Broadband Map’s Data, but FCC Has Not Documented or Evaluated Its Processes for Verifying the Data’s Accuracy

Agencies Rely on the Map as a Key Source of Broadband Availability Information When Making Program Funding Decisions

For their programs, all four selected agencies (FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury) rely to varying degrees on FCC’s National Broadband Map as a key source of broadband availability information for identification of locations unserved by broadband, a critical step in making decisions about where to target funding and avoid overbuilding.[25]

First, for some broadband deployment programs, agencies rely almost exclusively on the National Broadband Map to select locations in which to fund deployment. For example, in 2023, FCC began using the map when identifying service locations for certain High Cost program mechanisms, as required by the Broadband DATA Act. Similarly, NTIA relies on the map extensively for BEAD implementation. For example, as required by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, NTIA allocated BEAD’s $42 billion in funding across the states based on each state’s number of unserved locations as displayed on the map. Further, the BEAD program required state and territory recipients to use the map to establish their initial lists of locations eligible for BEAD funding.

Second, for some other programs, agencies use the National Broadband Map in combination with one or more other information sources to identify where to target their funds. In particular, for both rounds of TBCP funding, NTIA allowed Tribes applying for funding to self-certify that locations for which they were applying were unserved by broadband. However, in the second round, NTIA decided to validate Tribes’ self-certifications by comparing them against information in the National Broadband Map and other agency data sources.[26] Moreover, according to USDA officials, USDA analyzes the map when assessing proposed projects for ReConnect and Community Connect but then compares the broadband availability information on the map with data from a variety of other sources, including states, program applicants, and USDA’s own general field representatives.

In particular, USDA relies on its Service Area Validation process. Under this two-stage process, USDA first conducts a “desktop review” by analyzing geographic information system data, among other methods, to determine whether an applicant’s proposed project area already has broadband available. Subsequently, if needed, a general field representative conducts an in-person site visit to attempt to verify the results of the desktop review.

Lastly, according to Treasury officials, Treasury does not require its CPF and SLFRF recipients to use the National Broadband Map when selecting broadband projects to fund. However, officials said they do encourage recipients to check the map in addition to leveraging other data sources.

FCC Has Tools to Ensure the Quality of the Map’s Data but Has Not Formally Assessed Their Effectiveness or Documented Them

The Broadband DATA Act requires FCC to verify the accuracy and reliability of the broadband availability data that internet service providers submit to FCC and that populate the National Broadband Map.[27] FCC described to us the tools it uses to meet this statutory obligation: data validations, verifications, audits, and enforcement referrals.[28]

· Validations. All data submitted by providers undergo automated validations at the time the provider submits them to FCC’s data collection system. These validations check that the data (1) meet the specifications set forth by FCC (e.g., a provider’s entry in a data field must not exceed a certain number of characters); (2) do not contain any apparent errors (i.e., internal inconsistencies); and (3) do not display any anomalous patterns (which officials said could include, for example, showing greater-than-expected changes in availability for a certain technology type and speed threshold, as compared with the provider’s most recent submission). If the system identifies an error or anomaly, it prompts the filing provider to either correct the issue or submit an explanation as to why the submission should remain unchanged. FCC staff review these explanations and, where needed, follow up with providers to request clarification. These inquiries can result in corrections to provider-submitted data. Ultimately, staff can withhold data from publishing if providers do not provide an adequate response to FCC inquiries, or staff identify clear errors.

· Verifications. According to officials, FCC typically initiates verifications as a result of referrals from third parties or staff reviews of provider data. For example, a state broadband office may report to FCC that it has received numerous complaints from consumers in a certain geographic area related to a provider not offering speeds it claims to offer in its advertisements.[29] Then, FCC requires the provider to submit additional information about its network infrastructure and service availability to substantiate availability claims. According to FCC documents, its staff initiated over 900 validation and verification inquiries from January 2023 through January 2024, resulting in updates to over 600 submissions.

· Audits. According to FCC officials, and as required by the Broadband DATA Act, FCC conducts random and targeted audits of provider data, which focus on the accuracy of a provider’s reported availability data and largely resemble the verifications described above.[30] As of December 2024, FCC had initiated seven audits—some of which have been closed—as officials have chosen to prioritize verifications instead.

· Enforcement referrals. FCC may refer entities for enforcement actions for (1) failing to make a Broadband Data Collection filing in accordance with FCC rules and instructions; or (2) willfully and knowingly, or recklessly, submitting inaccurate or incomplete information regarding the availability or quality of broadband service.[31] FCC officials told us that as of January 2025, they had made a number of referrals to the agency’s Enforcement Bureau, resulting in two consent decrees, 11 citations, and 10 forfeitures.

Although the above tools represent meaningful efforts to assess and improve the reliability of providers’ broadband availability data, the sufficiency of these efforts is not entirely clear. First, FCC can only carry out a limited number of verifications, audits, and enforcement referrals with its existing resources. In addition, except when FCC may use mobile drive testing conducted by an FCC contractor, verifications and audits rely on information provided to FCC by the same providers whose data are being questioned in the first place. For example, in response to a verification inquiry, mobile providers have the option to submit their own speed test data.

Further, FCC has reported that a substantial number of the challenges filed against fixed availability data (i.e., data that describe the availability of broadband to fixed locations, such as houses or stores) have been successful. Such successful challenges demonstrate that a nontrivial amount of inaccurate data ends up on the National Broadband Map despite FCC’s validations, verifications, audits, and enforcement referrals. For example, between November 2022 and November 2023, filers submitted approximately 8 million challenges to the map’s fixed availability data.[32] FCC accepted (i.e., it deemed a challenge to have sufficient evidence) and submitted to providers almost 4 million of those challenges, about half of which providers ultimately conceded, resulting in updates to the map.

Finally, stakeholders we interviewed—including industry groups, advocacy organizations, and others—raised significant concerns about the reliability of broadband availability data on the National Broadband Map, while acknowledging that the granularity of the data represents a marked improvement over FCC’s prior, census-block approach. First, three stakeholders questioned whether providers should serve as the source of the data. For instance, one stakeholder suggested the data would be more reliable if FCC supplemented providers’ data with data from other sources, while another stakeholder told us that an independent entity should provide the data, rather than providers.

Additionally, one stakeholder suggested providers have an incentive to overstate the service they offer to prevent competitors from having an opportunity to provide service in the same location. Further, six stakeholders offered reservations about the data, in particular that the data might tend to overstate broadband service. For example, three stakeholders expressed the view that providers’ reporting of advertised speeds, as required by FCC’s data specifications, rather than speeds users typically experience, likely results in overstating the quality of service. Another stakeholder pointed out that FCC allows a provider to report that it serves a location even if it does not actually serve it, as long as the provider claims it could begin serving that location within 10 business days.[33] This could lead to artificially inflating availability information. Finally, officials we spoke with from two major U.S. cities shared examples of providers in those cities overstating the coverage they offer.[34]

According to agency documents, FCC is continually refining its processes for validating, verifying, and auditing providers’ broadband availability data and making enforcement referrals based on lessons learned, but officials said FCC has not formally assessed the effectiveness of these efforts. For example, staff told us they have added more granular final data checks to the automated validations. Moreover, staff have begun to develop data-driven algorithms to help narrow the focus of verification inquiries to specific providers, technologies, and areas. While these efforts may have improved FCC’s processes, they have not necessarily shed light on the outcomes of these processes. More specifically, FCC has not evaluated the extent to which its validations, verifications, audits, and referrals are sufficient in ensuring the accuracy and reliability of provider availability data, the original purpose of these processes.

Moreover, although FCC began collecting provider data in June 2022, officials told us FCC has not yet formally documented the procedures that staff must conduct to carry out the data validations, verifications, audits, and enforcement referrals. Specifically, as of December 2024, 4 years after first announcing that it would use these four tools to help ensure data quality, only various discrete components of these processes (e.g., a process for targeting providers for verification or audit), have been informally documented.

Federal internal control standards state that an agency’s management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system (in this case, validations, verifications, audits, and referrals) and evaluate the findings of those activities.[35] Management may conduct monitoring through ongoing monitoring activities, stand-alone evaluations, or both, and then must assess and document the results to identify internal control issues. This assessment enables management to determine the effectiveness of its controls and take needed steps to remediate identified deficiencies. Federal internal control standards also state that an agency’s management should establish documented policies for the organization’s internal control responsibilities.

FCC officials described its processes for data validations, verifications, audits, and enforcement referrals as a new workstream that continues to be informed by fresh rounds of data, citing this as the reason why FCC had not yet formally evaluated or finalized formal operating procedures for these processes. However, without evaluating the effectiveness of its validations, verifications, audits, and referrals processes, FCC cannot know the extent to which these processes are sufficient to ensure the accuracy of the data in the National Broadband Map. This, in turn, increases the risk that shortcomings of these processes, if any, may linger. Such risks could jeopardize federal agencies’ ability to make efficient and effective federal funding decisions based on the availability data in FCC’s National Broadband Map, as well as stakeholders’ confidence in the data and those decisions. Evaluating the results of these activities could help FCC determine the right balance of activities, given available resources, or whether additional resources or controls are needed.

Ensuring that the processes are formally documented and consistently applied as soon as practicable is particularly important, given the new nature of this workstream, the role the data play in maximizing the efficiency of billions of dollars in funding across federal broadband programs, and the fact that data are to be continuously updated. Doing so also reduces the risk that if FCC staff leave the organization, information and knowledge on these new processes, which could be difficult to recover, would be lost.

Interagency Coordination Efforts Partially Followed Most Leading Collaboration Practices

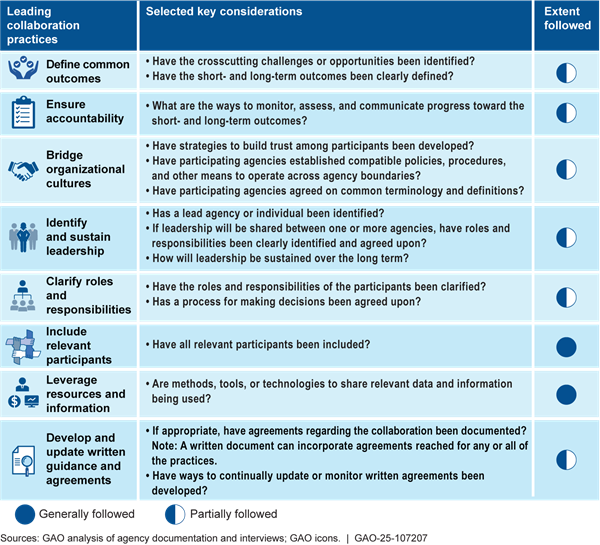

We identified several key mechanisms and activities that FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury use to coordinate with each other on their administration of federal broadband funding. As shown in figure 1 and discussed further below, we found that the agencies’ interagency coordination efforts generally followed two, and partially followed six, of eight leading practices that we have previously identified as aiding collaborative efforts.[36] Our prior work has shown that these practices help agencies enhance and sustain collaboration and are useful for addressing complex issues, such as federal broadband funding.

Figure 1: Extent to Which Interagency Coordination Efforts to Administer Federal Broadband Funding Follow Leading Collaboration Practices

Note: Generally followed – Interagency coordination mechanisms and activities followed most or all aspects of the selected key considerations that GAO examined for the leading practice. Partially followed – Mechanisms and activities followed some, but not most, aspects of the selected key considerations.

Agencies Continue to Use Varied Coordination Mechanisms to Administer Federal Broadband Funding

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury use a variety of preexisting and new mechanisms to coordinate their administration of federal broadband funding. We previously reported in May 2022 on the various mechanisms the agencies use, and we found that they have continued to use and expand them since 2022.[37] In addition, agency officials told us about new mechanisms, such as the Broadband Funding Map.

· Information-sharing MOU. In May 2022, FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury entered into an MOU that established guidelines for the agencies to share information about broadband deployment funding under their programs. The MOU is the main mechanism these agencies use to share information about their existing and pending broadband deployment projects, according to agency officials. The agencies revised and extended the MOU in May 2024, which expires in 4 years and may be extended as agreed upon by the four agencies.

· Biweekly coordinating meetings. In 2022, Treasury joined the biweekly coordinating meetings that were already taking place among FCC, NTIA, and USDA to discuss broadband-related issues, such as new funding or avoiding duplicative funding.[38] As of December 2024, the four agencies continued to meet to share information about federal broadband funding. According to agency officials, these recurring meetings are the primary mechanism by which they build trust among each other.

· Bilateral agency-to-agency coordination. According to program funding notices and agency officials, FCC, NTIA, and USDA coordinate with each other directly prior to awarding broadband funding to help avoid duplication of funding. For example, FCC and USDA have coordinated on FCC’s High Cost program and USDA’s programs, such as Community Connect, which were established prior to 2022. Since 2022, the agencies have extended these efforts to include programs such as those established under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. For example, the ReConnect funding notice for fiscal year 2024 states that USDA will coordinate with NTIA to ensure the program complements BEAD. Further, in July 2024, USDA’s Rural Utilities Service and NTIA entered into an MOU to help coordinate the concurrent implementation of ReConnect’s fifth round of funding and BEAD to avoid duplicative funding. Coordinated program implementation may help reduce the possibility of wasteful duplicative funding, which, as we noted in 2022, may increase with the number of broadband programs.[39]

· Broadband Funding Map. In May 2023, FCC published the first version of the Broadband Funding Map. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act authorized the map to be the centralized, authoritative source of data on federally funded broadband deployment projects. The map displays agency-provided, project-level data, including planned start and end dates, amount of funding awarded, network type, and expected speeds. Officials told us that the map provides a mechanism for agencies to share data with each other and that they can consult the map when coordinating on funding decisions.

In addition to these main coordination mechanisms, the four agencies also participate in other activities, such as the Broadband Coordination Group convened by the Executive Office of the President, which we discuss below.

Coordination Efforts to Administer Federal Broadband Funding Generally Followed Two of Eight Leading Practices

We found that the agencies’ coordination mechanisms and activities generally followed two leading collaboration practices: (1) including relevant participants and (2) leveraging resources and information.

|

Key Considerations for Including Relevant Participants · Have all relevant participants been included? Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107207 |

· Including relevant participants. Leading practices state that collaborative efforts should include all relevant participants. As discussed above, the four agencies—FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury—that administer most of the federal broadband funding use a variety of mechanisms to coordinate with each other. In addition to these mechanisms, the four agencies also meet monthly as part of the Broadband Coordination Group convened by the Executive Office of the President’s National Economic Council.[40] As of December 2024, the Executive Office of the President told us that the group has convened at least 10 times to coordinate on a wide range of broadband issues, such as mapping and de-duplication of funding, since 2022. The American Broadband Initiative Federal Funding Workstream—co-chaired by NTIA and USDA—also meets biweekly to bring together FCC, NTIA, USDA, Treasury, and other federal agencies that have smaller pools of funding.[41] The group comprises over 20 federal agencies with broadband initiatives and allows them to share and learn about their efforts.

|

Key Considerations for Leveraging Resources and Information · Are methods, tools, or technologies to share relevant data and information being used? Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107207 |

· Leveraging resources and information. Leading practices state that to successfully address crosscutting challenges or opportunities, collaborating agencies must leverage technological resources. FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury leverage the Broadband Funding Map and the National Broadband Map as tools to share relevant data to help avoid duplicate funding awards for new broadband deployment.[42] For example, USDA officials told us that the agency has submitted quarterly updates on new broadband investments to the Broadband Funding Map since its initial publication in May 2023. To better align Broadband Funding Map submissions, these officials said it is important to have program funding available for administrative purposes that could also be leveraged to cover key administrative expenses. Such expenses could include having staff with specialized skillsets that can analyze, share, and update geographic information system data in a timely and accurate manner.

Coordination Efforts to Administer Federal Broadband Funding Partially Followed Six of Eight Leading Practices

We found that the agencies’ coordination mechanisms and activities partially followed six leading collaboration practices: (1) defining common outcomes, (2) ensuring accountability, (3) identifying leadership, (4) clarifying roles and responsibilities, (5) developing written guidance and agreements, and (6) bridging organizational cultures.

Defining Common Outcomes and Ensuring Accountability

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury have identified a shared goal in their efforts to administer federal broadband funding but have not defined specific outcomes or performance measures to track progress across programs. Leading practices state that collaborative efforts benefit from defining short- and long-term common goals and outcomes. In addition, these practices state that establishing ways to track and monitor progress toward the shared goals and outcomes, and using performance information to do so, is key to reinforcing accountability.

|

Key Considerations for Defining Common Outcomes · Have the crosscutting challenges or opportunities been identified? · Have the short- and long-term outcomes been clearly defined? Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107207 |

· Defining common outcomes. The four agencies have not formally defined specific short- and long-term shared goals or outcomes. However, officials from each agency told us that, generally, their shared, overall goal is to provide universal, high-speed internet service to all Americans (e.g., NTIA’s Internet for All initiative).[43] FCC and NTIA officials also said that each agency and program may have its own short- and long-term goals in line with their statutory mandates.[44] In addition, eight of 10 external stakeholders we interviewed agreed that the agencies have a common goal of providing universal broadband access, but individual programs may have different targeted goals largely due to various statutory requirements. Agency officials and seven stakeholders also told us that these statutory requirements, which may include different definitions (e.g., speed thresholds for broadband service provided by funded projects), or parallel program timelines, are a crosscutting challenge for programs.

|

Key Considerations for Ensuring Accountability · What are the ways to monitor, assess, and communicate progress toward the short- and long-term outcomes? Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107207 |

· Ensuring accountability. Officials from all four agencies said that, generally, they use the National Broadband Map to help track progress toward the overall goal of Internet for All. However, we found that the agencies have not established specific performance measures or metrics (e.g., an annual percent decrease in unserved locations) to track progress across all federal programs that fund broadband deployment. While NTIA publishes an annual Federal Broadband Funding Report to cover overall trends in federal broadband investments, outcomes, and economic impacts, it does not identify specific performance metrics.[45] Officials from FCC, NTIA, and USDA, however, said that agencies track progress toward their program-specific goals through funding award reporting requirements. For example, NTIA has postaward mechanisms to track progress of approved BEAD proposals, such as completed milestones, which is shared through a public dashboard.

To help ensure that agencies’ programs are aligned, to the extent possible, with an overarching strategy and to minimize duplicative efforts, we previously recommended that the Executive Office of the President develop a national broadband strategy that includes clear goals and performance measures.[46] The office did not take a position on our recommendation and has not developed a strategy that includes all actions to implement the recommendation as of December 2024. Given this recommendation, we are not making an additional recommendation at this time. We will continue to monitor efforts to implement this recommendation, as well as the results of key federal programs that fund broadband deployment, as part of our ongoing work to help ensure accountability for the billions of dollars in funding.

Identifying Leadership and Clarifying Roles and Responsibilities

While FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury have identified a leadership model, they have not collectively defined clear roles and responsibilities. Leading practices call for identifying a leadership model, such as a lead agency or shared leadership, to support oversight and decision-making capabilities of collaborative efforts. In addition, these practices state that clearly defining and agreeing on roles and responsibilities can help agencies organize their joint or individual efforts and overcome barriers when working across agency boundaries.

|

Key Considerations for Identifying and Sustaining Leadership · Has a lead agency or individual been identified? · If leadership will be shared between one or more agencies, have roles and responsibilities been clearly identified and agreed upon? · How will leadership be sustained over the long term? Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107207 |

· Identifying leadership. FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury officials agreed that they share leadership but had varying perspectives on whether one agency may have the lead agency role in coordination efforts. Specifically, FCC, USDA, and Treasury officials said that NTIA is a leader, or that NTIA has a special role, given that it is the President’s principal telecommunications advisor. However, NTIA officials told us that Congress has not statutorily mandated any agency as the main lead. NTIA facilitates coordination among relevant agencies as the principal advisor, but each agency works to lead and manage its own programs, according to NTIA officials. In addition, these officials told us that NTIA has strategic and statutory reasons to continue facilitating coordination. For example, the ACCESS BROADBAND Act directs NTIA to coordinate with other agencies to enhance efficiency and prevent duplication of federal funding.[47]

|

Key Considerations for Clarifying Roles and Responsibilities · Have the roles and responsibilities of the participants been clarified? · Has a process for making decisions been agreed upon? Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107207 |

· Clarifying roles and responsibilities. FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury officials said that each agency plays a role largely defined in the statutes authorizing or establishing each agency’s programs. NTIA officials also noted that agency and program statutes come closest to defining responsibilities for the agencies. For example, FCC’s role and responsibilities in developing the National Broadband Map and Broadband Funding Map were defined by the Broadband DATA Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, respectively.[48] However, while the agencies have taken some steps to further identify roles and responsibilities (such as through the information-sharing MOU), they have not clearly and collectively defined, agreed upon, or formally documented key areas of coordination efforts, as discussed further below.

To help ensure that coordination efforts are complementary and lower the risk of overlap and duplication in federal funding, we previously recommended that the Executive Office of the President develop a national broadband strategy, as discussed above, that also includes clear roles.[49] Given this existing recommendation, we are not making an additional recommendation at this time but will continue to monitor efforts to implement this recommendation.

Developing Written Guidance and Agreements

|

Key Considerations for Developing and Updating Written Guidance and Agreements · If appropriate, have agreements regarding the collaboration been documented? A written document can incorporate agreements reached for any or all of the practices. · Have ways to continually update or monitor written agreements been developed? Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107207 |

While FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury have established some written guidance and agreements to guide their coordination efforts, the existing documentation does not clearly state the scope of some key collaborative efforts and how the agencies will implement them. In addition, the agencies have not clearly documented these key areas in other written guidance or agreements. Leading practices state that articulating agreements in formal documents, and developing ways to monitor and update those agreements, can strengthen participants’ commitment to work together and help outline how collaborative efforts operate. These practices also state that documentation can provide consistency in the long term, especially when there are changes in leadership.

As discussed above, the four agencies have established the information-sharing MOU as the main mechanism to share information about their broadband deployment projects and guide their coordination efforts. When the MOU expired in May 2024, the agencies revised and extended it. With regard to monitoring this agreement, the MOU includes a provision stating that it may be revised or modified upon the written agreement of the agencies. NTIA officials told us that requests to update typically come up organically during coordination meetings or other such forums. In addition, Treasury officials noted that agencies periodically monitor the MOU for needed updates.

However, we found three key areas where the existing documentation does not clearly state the scope of, or discuss how the agencies will implement, the collaborative efforts. In addition, the agencies have not clearly defined, agreed upon, or documented these key areas in other written guidance or agreements. Specifically:

· Defining covered data. The MOU states that the agencies shall share information with each other about certain projects that have received, or will receive, funds for broadband deployment, including, but not limited to, “covered data.” However, because the agencies have not clearly defined or documented what “covered data” include, it is unclear what data agencies have actually agreed to share. When we asked FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury officials what “covered data” encompass, officials provided varied responses. While officials from all four agencies mentioned data related to the Broadband Funding Map, they also provided different explanations of what “covered data” include in practice. For example, FCC officials provided examples related to pending grant applications and data aiding in identifying overlaps during the preaward phase, which officials from the other agencies did not cite. In our analysis of agency documentation, we saw examples of variance in agencies sharing data on funded project locations, pending applications, and percent overlap in proposed service areas.

Officials indicated that various factors played a role in not explicitly defining “covered data.” For example, FCC officials said the type of data an agency shares may depend on how it collects information from program applicants or defines eligible areas (e.g., covered census blocks vs. proposed service areas). NTIA officials also noted that the agencies regularly share information about their projects and have open communication channels to address any concerns around sharing “covered data,” such as providing data to assess potential duplication or additional information, as needed. USDA officials added that agencies having a certain level of flexibility when administering their programs under different statutory requirements is important, such as when considering how to define “covered data” to share information.

Clearly documenting an agreed-upon definition of “covered data,” including the scope or type of data, would help ensure consistent information sharing about broadband deployment projects across agencies’ programs and across years, especially if there are changes in leadership or new staff. For example, without a clear definition, one agency may continue to share information on funded awards and pending applications, while another agency may only share information on funded awards. Agreeing upon a clear definition of “covered data” could also allow the agencies to build needed flexibilities into the definition, which could also help to document expectations. Doing so is particularly important, as sharing information and data on each agency’s projects is critical to agencies’ ability to maximize the value and reach of the billions of dollars in federal spending committed toward expanding broadband access.

· Submitting Broadband Funding Map data. While each agency is responsible for providing data to FCC to update the map on a periodic basis, as directed by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, there are no specific and agreed-upon timelines for when agencies are to provide data on their funded projects (e.g., 2 weeks after an award is funded).[50] FCC officials told us that the agency provides monthly reminders to encourage each agency to submit relevant data to the map, but the act does not require specific timelines or provide consequences for failing to submit data. When asked about the estimated frequency that each agency submits data, officials provided varying time frames, such as monthly or quarterly.[51] For example, NTIA submits data at least monthly on new awards or changes to existing awards, and USDA submits quarterly updates, according to officials from these agencies. USDA officials also noted that one agency does not report data until construction on the project is well underway or complete. In addition, Treasury officials told us that their reporting frequency to the map can vary for Treasury’s programs based on the size of the funding recipient, such as quarterly or annually.

According to NTIA and USDA officials, it is challenging to keep the data on funded and revised awards up to date and to coordinate funding decisions without updated data. As discussed above, the agencies leverage the Broadband Funding Map to share data with each other and sometimes consult the map when coordinating on funding decisions. Thus, NTIA and USDA officials suggested that setting agreed-upon timelines for submitting data on funded awards, including any changes to awards, would aid coordination. FCC officials told us that the agencies have held preliminary discussions about developing written guidance, to include timelines for data submission, but the agencies are focusing on other aspects of coordination at this time. In addition, in its September 2024 report on proposals to improve broadband program alignment, NTIA recommended that agencies create programmatic documents that include data reporting requirements for the Broadband Funding Map and for NTIA’s data collection obligations under the ACCESS Broadband Act.[52] While acknowledging that it may take time to collect the data, the report stated that an accurate map is crucial to ensuring effective federal funding, including to prevent duplicative funding.

Moving forward, agreeing upon a definition of “covered data” and documenting compatible procedures on when to provide those data, could strengthen the agencies’ commitment to submit timely broadband deployment data and ensure that the map reflects up-to-date information on funded awards, including changes to awards. Doing so would also better position agencies to coordinate effectively to maximize federal dollars, in part, by reaching areas with the greatest need, such as areas that may have not received prior funding.

· Establishing a de-duplication process. Officials from FCC, NTIA, and USDA told us that they have not established a formal process to de-duplicate their funding prior to making decisions about projects to fund.[53] Rather, these officials said the agencies generally follow a high-level process, authored by NTIA, for de-conflicting and resolving potentially duplicative funding situations. NTIA provided us with a written description of the process, which outlined five steps, but stated that it is not an official, agreed-upon process.[54] Similarly, USDA officials told us that the agency views NTIA’s written description as more of a set of guiding principles and is not required to take all the steps listed. Agencies may also use documentation provided by relevant entities in conjunction with this process to coordinate with federal and state partners, as USDA did when we observed its staff applying the de-duplication process for a Community Connect application. In addition, NTIA developed internal standard operating procedures to document coordination and de-duplication practices for BEAD and TBCP’s second round of funding.

Further, FCC and NTIA officials said that the agencies have considered documenting more formal procedures on de-duplication, potentially through a revised, more detailed MOU or best practices document, but did not provide additional information, supporting documentation, or a time frame.[55] NTIA’s September 2024 report on proposals to improve broadband program alignment also recommended that agencies consider revising the information-sharing MOU to establish a single, consistent, formalized de-duplication review process.[56]

Clearly defining, agreeing upon, and documenting a formal de-duplication process would better position the agencies to resolve potentially duplicative funding decisions and facilitate the timely announcements of awards. Doing so could also help avoid project delays or increased costs for awarded projects, such as in instances when duplication is identified postaward. And, ultimately, it could help ensure that federal funding benefits areas that lack high-speed internet, such as unserved or underserved areas.

Bridging Organizational Cultures

|

Key Considerations for Bridging Organizational Cultures · Have strategies to build trust among participants been developed? · Have participating agencies established compatible policies, procedures, and other means to operate across agency boundaries? · Have participating agencies agreed on common terminology and definitions? Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107207 |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury have made progress in bridging organizational cultures but have not fully established compatible policies and procedures, as noted above. Leading practices state that creating common terminology and definitions, undertaking activities to build trust, and developing compatible policies and procedures help agencies coordinate effectively across agency boundaries.

To help bridge organizational cultures, FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury officials acknowledged that the agencies have taken steps to understand each other’s varied terminology for their programs, some of which is required by statute. As noted above, broadband speed thresholds for buildout can differ across programs, as can the unit of analysis when reporting information and what constitutes an “unserved status.”[57] According to officials from all four agencies, they are aware of the differences across the agencies and within programs and generally understand how another agency applies those terms through conversations and documentation, such as program statutes and notices of funding opportunities. For example, officials understand that USDA uses “de-confliction,” while the other agencies use “de-duplication” to describe processes around avoiding overlapping funding. Further, officials said the biweekly meetings and all other coordination mechanisms the agencies use have contributed toward building mutual trust.

Establishing ways to operate across agency boundaries, such as through developing a common understanding of key terms and compatible policies, can help address cultural differences and strengthen trust. Therefore, addressing the gaps we identified in the agencies’ coordination efforts could further bridge their organizational cultures.

State Broadband Offices Have Varied Perspectives on Federal Broadband Funding Coordination Efforts

Selected Agencies Coordinate with State Broadband Offices Using a Variety of Similar Methods and on Common Topics

We found that FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury all coordinate with states and territories through a broad range of methods that were similar across the agencies, and on several common topics.[58] According to officials from all four agencies, the purpose of this coordination is to help states navigate federal broadband programs. These officials told us that their coordination activities with states and territories—which two characterized as extensive—are either loosely guided by statute or occur on a more ad hoc basis based on the programs’ focus and states’ needs.

· FCC. For instance, the Broadband DATA Act requires that FCC provide technical assistance through tutorials and webinars to state, local, and tribal government entities regarding the National Broadband Map challenge process. While FCC’s broadband funding programs are mostly directed toward eligible telecommunications carriers (such as eligible internet service providers), it coordinates with states and territories for the Broadband Data Collection. FCC conducts outreach with states and territories for this effort to educate them on the challenge process and to facilitate communication about specific concerns.

· NTIA. As another example, the ACCESS BROADBAND Act and BEAD statutory requirements guide NTIA’s coordination activities with state broadband offices. For example, the ACCESS BROADBAND Act requires NTIA’s Office of Internet Connectivity and Growth to connect with communities that need access to broadband; hold regional workshops across the country to share best practices for promoting broadband access and adoption; and coordinate with state agencies, as applicable, when carrying out these efforts. In addition, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act requires that NTIA provide technical support and assistance to eligible entities (i.e., states and territories) on a variety of issues to facilitate their participation in BEAD.

· USDA. In contrast, USDA’s coordination with states and territories is mostly ad hoc. While USDA program funding recipients are typically internet service providers, USDA officials told us that they coordinate with state broadband offices occasionally, such as to prevent duplication or overlap with other federal funding in a state. Officials also told us that coordination with state broadband offices has increased throughout 2024, such as through the general field representatives who engage directly with states on broadband issues.

· Treasury. Treasury officials told us they coordinate extensively with states and territories, which are the CPF funding recipients.

As shown in table 1 and described below, the agencies use a variety of similar methods to coordinate, both individually and jointly, with state broadband offices.

Table 1: FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury Methods of Coordination with State and Territory Broadband Offices on Federal Broadband Programs

|

Method |

Example |

Used individually |

Used jointly |

|

Agency office hours: Use designated time to answer state broadband office questions and share information in a collaborative space |

FCC officials host virtual office hours to provide specific guidance to state officials, who can attend on an as-needed basis. NTIA also hosts office hours that other agencies may attend. |

FCC, NTIA, and Treasury |

✓ |

|

Assigned point-of-contact: Designate specific staff to have frequent communication and visibility with state offices |

NTIA and USDA use specific positions (program officers and general field representatives, respectively), while FCC and Treasury assign individuals for each state broadband office. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✗ |

|

Email communication: Provide programmatic updates, information, and answer questions |

Treasury communicates with state offices through a program-specific inbox to answer a variety of questions on policy, requirements, and reporting. NTIA includes FCC program information in its emails to states to deliver timely joint updates. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✓ |

|

In-person events: Host or attend conferences and events to share information and answer questions |

NTIA hosts, and federal agencies attend, in-person events with state offices. Federal agencies also attend other organizations’ conferences and events. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✓ |

|

Newsletters: Share a range of information in one place |

Treasury and NTIA produce newsletters for their programs. FCC has provided information to NTIA for its newsletters. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✓ |

|

Phone calls: Communicate and coordinate with state broadband offices on specific issues or to answer questions |

FCC called broadband leaders in every state and territory as a first step in coordination between FCC and the states for its Broadband Data Collection. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✓ |

|

Public notices: Share information and receive comments on federal broadband programs |

USDA uses the public notice filing process to review information about projects and facilitate de-duplication efforts with applicants, such as between its ReConnect program and NTIA’s Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✗ |

|

Recurring meetings: Convene state and territory officials multiple times per year to discuss programs and relevant topics |

NTIA’s State Broadband Leaders Network meets once per month. |

FCC, NTIA, and Treasury |

✓ |

|

Virtual events: Host or attend virtual meetings and other events |

FCC has hosted virtual events for states regarding FCC programs and data reporting to its National Broadband Map. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✓ |

|

Webinars: Host meetings about a program, such as ahead of a notice of funding opportunity deadline |

Treasury conducts webinars when there is new guidance for the Capital Projects Fund and State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund programs, such as when it publishes new FAQs and answers on its website. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✓ |

|

Written guidance: Publish application guidance, frequently asked questions, and technical assistance on website |

Treasury issued a user guide for program recipients, including information on reporting requirements. NTIA created a technical assistance website, providing a one-stop shop for NTIA programmatic support. |

FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury |

✗ |

Legend: ✓ = Yes and ✗ = No

Source: GAO analysis of documentation and interviews with officials from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), and Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and the Treasury. | GAO‑25‑107207

Officials from all the agencies characterized some of their coordination with states and territories as a joint federal effort. For example, officials from all four agencies coordinate with state offices through NTIA’s State Broadband Leaders Network, which is a network of state broadband office practitioners (such as directors) that NTIA convenes to provide a forum to coordinate and share information on broadband programs. FCC, USDA, and Treasury officials attend the State Broadband Leaders Network gatherings or provide program materials for these events. Additionally, while USDA officials told us they do not host recurring coordination events, USDA officials have participated in NTIA’s events to coordinate with state offices. FCC and NTIA have also partnered during office hours. For example, FCC officials told us that they have partnered with NTIA officials to facilitate a discussion about how to use FCC’s National Broadband Map in the state challenge processes for BEAD.

The agencies generally coordinate through these various means with state broadband offices on a set of similar topics. See table 2 for a description of these topics.

Table 2: FCC, NTIA, USDA, and Treasury Topics of Coordination with State and Territory Broadband Offices on Federal Broadband Programs

|

Topic |

Description |

|

Application guidance |

The agencies provide information and support to help guide state broadband offices and applicants through their program applications and requirements for broadband deployment and infrastructure projects. |

|

Broadband availability data maps |

FCC and NTIA coordinate with state offices to assist in the data collection efforts for FCC’s National Broadband Map and state challenge process for the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program, respectively. |

|

Matching fundsa |

The agencies administer several programs that allow the use of matching funds. Treasury has provided additional guidance for matching funds from its Capital Projects Fund with other programs. |

|

Preventing duplicative funding |

The agencies coordinate with state offices to help ensure that no duplicative funding occurs across federal programs and locations. |

|

Service areas/project locations |

The agencies provide guidance to applicants as they determine which areas to fund and share more information about projects set to receive federal funds in the area or that may potentially be in a proposed project area. |

|

Timelines of competing federal funding |

The agencies provide guidance on timelines for notices of funding opportunities. At times, more than one agency’s program will have an open notice of funding opportunity, which may require state offices and applicants to determine which program to apply for and where to propose a project, based on each federal broadband program’s respective timeline. |

|

Environmental requirements (e.g., environmental permitting and clearances) |

The agencies may provide coordination to help state offices navigate environmental requirements of a project, such as the National Environmental Policy Act, that states and applicants may have to meet to fund and begin construction on a project. |

Source: GAO analysis of documentation and interviews with officials from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), and Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and the Treasury. | GAO‑25‑107207

aRecipients of federal awards generally may not use funds from a federal award to pay the matching contribution required by another award program, unless the program’s authorizing statute specifically provides for such use. 2 C.F.R. 200.306(b)(5). For example, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act specifically allows for recipients to use funds provided from certain federal programs as matching funds. Pub. L. No. 117-58, 60102(h)(3)(B), 135 Stat. 429, 1198–99 (2021).

Given programmatic differences, not all agencies coordinate on each topic. For example, FCC and NTIA work with state offices on broadband availability data maps because of their responsibilities with the National Broadband Map and the BEAD challenge process, respectively. Treasury officials said they coordinate with both state offices and other federal agencies in helping states navigate how to use funds from Treasury’s CPF and SLFRF programs as matching funds for other federal broadband programs, such as BEAD. In addition, given these programmatic differences, the level of coordination with state broadband offices may vary. For example, USDA officials highlighted that their coordination with state and territory governments may have been less than some other agencies’ coordination because their funding recipients are typically other entities, like internet service providers. Similarly, FCC officials told us that, prior to states establishing their state broadband offices, FCC often worked closely with other state entities, specifically state public utility commissions.

State Broadband Offices Have Varied Perspectives on the Effectiveness and Helpfulness of Federal Agency Coordination

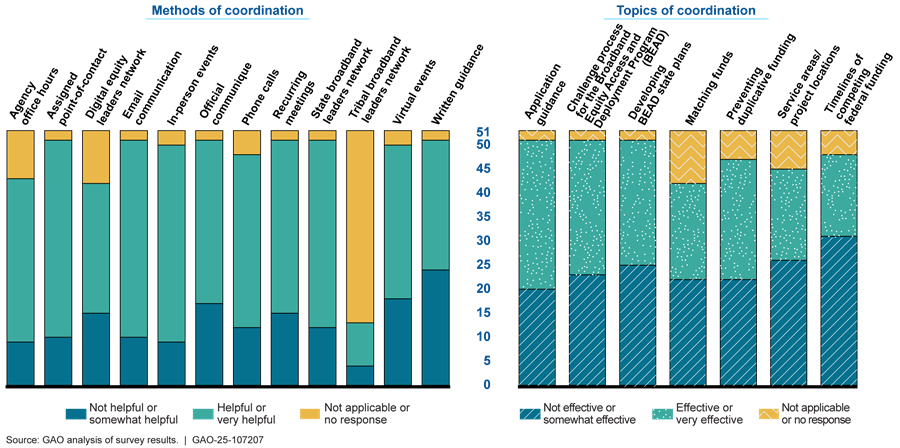

State broadband offices we surveyed provided their perspectives about specific aspects of the federal agencies’ coordination on federal broadband funding. As described below, the state offices that responded to our survey reported on how effective they viewed overall coordination, as well as their satisfaction with agencies’ expertise and timeliness; how helpful they viewed the different methods agencies used to coordinate; and how effective they viewed coordination on the different topics on which agencies provided coordination.[59]

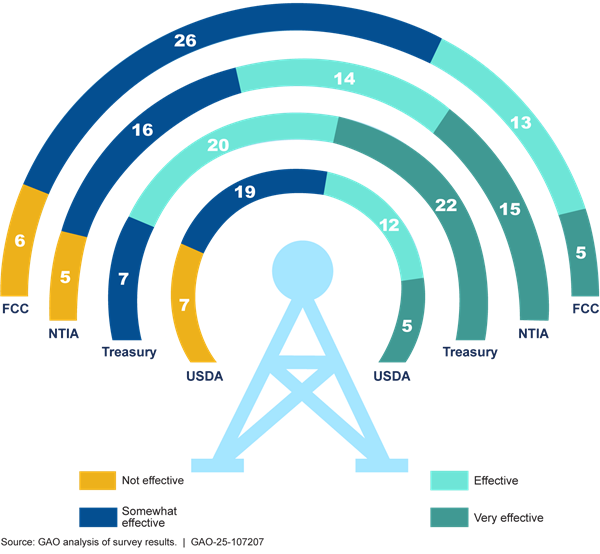

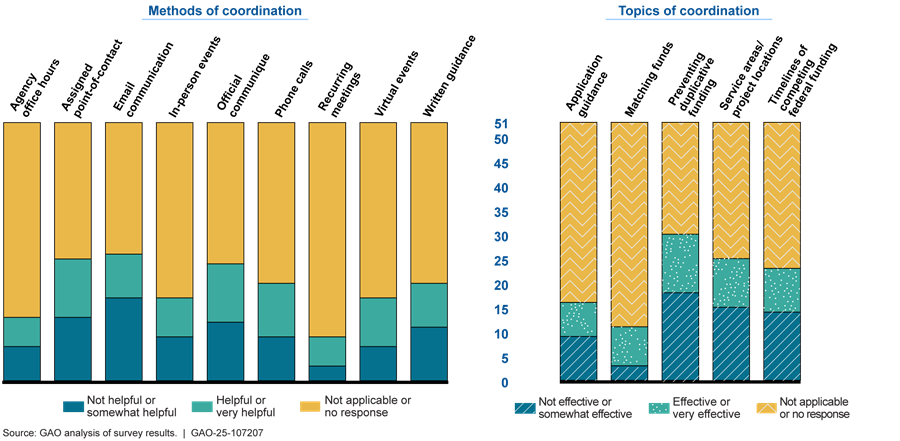

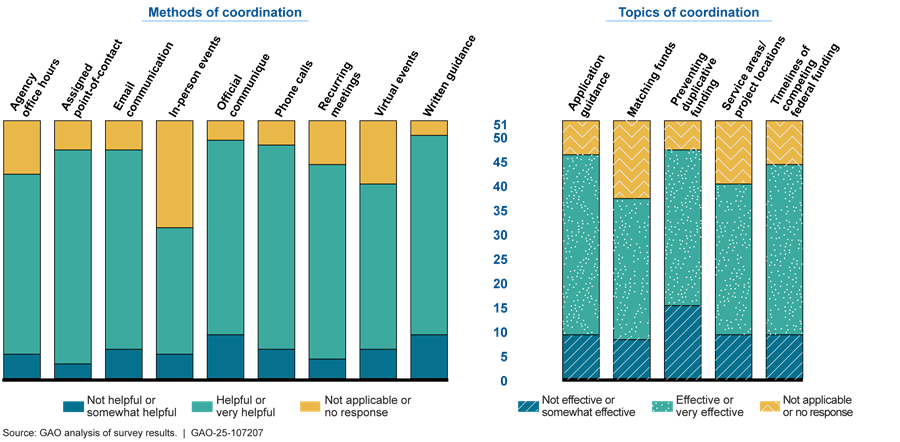

Overall coordination. When asked how they would characterize overall agency coordination efforts, most state broadband offices responded they would characterize Treasury officials’ coordination as effective or very effective, and many responded that NTIA officials’ coordination was effective or very effective (see fig. 2).[60] In contrast, many state offices responded that they would characterize FCC and USDA officials’ coordination as effective or somewhat effective.

Figure 2: State and Territory Broadband Office Views on Federal Agency Coordination with States and Territories on Federal Broadband Programs

Note: Fifty-one of 56 state and territory broadband offices completed our survey on state and territory views of coordination by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), and Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and the Treasury. Of those 51, one did not respond to this question. USDA and Treasury responses will not total 50 due to “not applicable” responses.

Expertise. In general, state broadband offices indicated they are satisfied with agency officials’ expertise in facilitating coordination with them on federal broadband programs. Specifically, most state broadband offices are satisfied with Treasury coordinating officials’ expertise, many are satisfied with FCC and NTIA officials’ expertise, and the majority of the offices that indicated coordinating with USDA are satisfied with USDA officials’ expertise.[61] For instance, one office responded that Treasury officials’ overall expertise has been instrumental in advancing its broadband goals. Further, the office stated that the insights that Treasury officials provided helped it identify its priorities and align its initiatives with available funding and helped it effectively address its unique challenges. This office also mentioned the expertise of NTIA officials as an aspect of coordination that has made the process of working with federal broadband funding seamless.

Timeliness. In general, the majority of state broadband offices reported they are satisfied with the speed with which coordinating officials from three of the four federal agencies responded to their offices’ questions, inquiries, and requests. Specifically, most state offices are satisfied with Treasury officials’ timeliness; many are satisfied with FCC and NTIA officials’ timeliness; and, of those who indicated they have coordinated with USDA, about one-third responded they are satisfied with USDA officials’ timeliness.

Methods and topics. We found that overall, state broadband offices characterized the various methods FCC, NTIA, and Treasury used to coordinate as helpful or very helpful, while they had mixed views on the helpfulness of USDA officials’ methods of coordination. Among the most helpful methods identified by state broadband offices were assigned points-of-contact; opportunities to interact through in-person, recurring, and virtual meetings; and phone and email correspondence. However, offices had mixed views on the effectiveness of agency coordination on specific topics. For example, across responses for FCC, NTIA, and USDA, some or many offices responded that coordination from the agencies on preventing duplicative funding, service areas/project locations, and navigating timelines of competing federal funding was not effective, or somewhat effective. In contrast, many state offices responded that the application guidance that NTIA and Treasury provided was effective, or very effective.