HURRICANE HUNTER AIRCRAFT

NOAA and Air Force Should Take Steps to Meet Growing Demand for Reconnaissance Missions

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

NOAA and Air Force Should Take Steps to Meet Growing Demand for Reconnaissance Missions

Highlights of GAO-25-107210, a report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact Cardell D. Johnson at (202) 512-3841 or johnsoncd1@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Air Force fly aircraft—known as Hurricane Hunters—into tropical cyclones and winter storms. Equipment on these aircraft collects critical data to help forecast a storm’s track and intensity.

Information from these aerial reconnaissance missions helps with evacuation efforts and storm preparations to protect life and property.

GAO Key Takeaways

Hurricane Hunter operations have increased since 2014, especially winter season missions, because of new responsibilities and greater demand for data. This has strained NOAA’s and the Air Force’s ability to meet their Hurricane Hunter responsibilities.

NOAA and Air Force officials said that limited aircraft availability and staffing shortages have contributed to Hurricane Hunters missing mission requirements—the key tasks of a mission. For example, they said maintenance issues prevented NOAA’s sole high-altitude jet from flying two Hurricane Helene missions in 2024. Since 2014, a growing number of mission requirements have been missed. However, NOAA and the Air Force have not systematically tracked the reasons for this. They also have not comprehensively assessed their Hurricane Hunter workforces to see if changes to staffing levels or workforce structure are needed.

NOAA plans to acquire six aircraft to replace its three aging planes, and the Air Force has identified needed technology upgrades for its aircraft. However, NOAA and Air Force senior leaders do not have a mechanism to regularly communicate with each other about their plans and resources. This has hampered the agencies’ ability to ensure that their decisions about investments in the Hurricane Hunters are aligned.

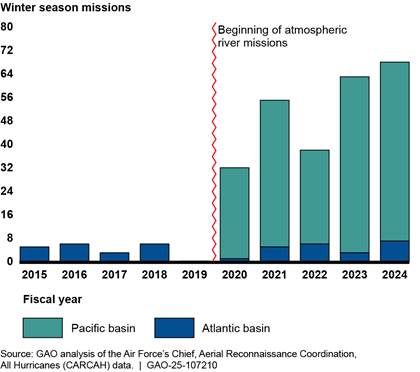

Note: Atmospheric rivers are regions in the atmosphere that transport water vapor from the tropics to higher latitudes, leading to extreme precipitation and flooding on the U.S. West Coast. This figure includes reconnaissance missions NOAA and the Air Force flew but does not include other types of missions such as research missions focused on atmospheric rivers.

How GAO Did This Study

We analyzed data and documents and interviewed officials from NOAA and the Air Force. We compared agency efforts against our key practices for evidence-based policymaking, among other things.

What GAO Recommends

We are making eight recommendations, including that NOAA and Air Force track data on why mission requirements are missed, assess their Hurricane Hunter workforces, and establish a mechanism for senior leaders to regularly communicate. The agencies agreed with our recommendations.

Abbreviations

CARCAH Chief, Aerial Reconnaissance Coordination, All Hurricanes

FY fiscal year

mph miles per hour

NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NWS National Weather Service

OPM Office of Personnel Management

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 13, 2025

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Rick Scott

United States Senate

The Honorable Roger F. Wicker

United States Senate

Tropical cyclones and winter storms are deadly and destructive natural disasters that can result in major safety, health, and economic impacts across the United States. From 1980 to 2023, the United States experienced 62 “billion-dollar” tropical cyclone events, in which storms such as hurricanes and tropical storms each caused more than $1 billion in damage. Collectively, these events resulted in nearly 6,900 deaths and at least $1.4 trillion in total damages, according to the Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).[1] During this same period, the nation also experienced more than 20 “billion-dollar” winter storms, such as Nor’easters and West Coast flooding associated with atmospheric rivers.[2] These winter storms collectively resulted in more than $100 billion in damages.

NOAA and the United States Air Force fly aircraft—known as Hurricane Hunters—directly into and above tropical cyclones and winter storms on reconnaissance missions to collect critical data used to forecast a storm’s track and intensity. NOAA’s National Weather Service (NWS) uses these and other data to develop weather forecasts and issues warnings for tropical cyclones and winter storms. These forecasts help to inform state and local preparedness and response efforts, including evacuation decisions. NOAA studies have found that including data collected by the Hurricane Hunters improved forecast accuracy by at least 10 percent.[3]

However, NOAA and the Air Force are sometimes unable to complete Hurricane Hunter mission requirements—the key tasks Hurricane Hunters perform to obtain information needed to develop forecasts—because of maintenance, staffing, and other issues. For example, as Hurricane Idalia threatened Florida in August 2023, all three of NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft were grounded, and therefore unable to collect data, because of maintenance issues. In a 2024 draft report to Congress on its Hurricane Hunter resources, NOAA acknowledged that its aging aircraft were an issue—two of its Hurricane Hunter aircraft entered service in the 1970s, and the third entered service in 1994.[4] NOAA has initiated efforts to replace its Hurricane Hunter aircraft fleet. The Air Force does not plan to replace its 10 Hurricane Hunter aircraft, which entered service between 1996 and 1999, but is exploring opportunities to upgrade the capabilities of the aircraft, according to officials and documents.

You asked us to review the status of NOAA’s and the Air Force’s Hurricane Hunter programs, including their future plans for the aircraft. This report examines (1) how the number of Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions has changed since 2014, (2) the challenges NOAA and the Air Force have faced in completing Hurricane Hunter mission requirements since 2014, and (3) the plans NOAA and the Air Force have developed to replace or upgrade their Hurricane Hunter aircraft and the challenges they have faced in implementing these efforts.

To examine how the number of Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions has changed since 2014, we analyzed Hurricane Hunter mission data from the Air Force’s Chief, Aerial Reconnaissance Coordination, All Hurricanes (CARCAH) unit.[5] Our analysis covered reconnaissance missions undertaken during tropical cyclone seasons in calendar years 2014 through 2023 and winter seasons in fiscal years (FY) 2015 through 2024.[6] We chose these years to provide a picture of Hurricane Hunter activities for the most recent full decade. We assessed the reliability of the data by, for example, conducting manual testing to look for discrepancies and interviewing CARCAH officials about the data. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing changes in the number of Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions.

We also reviewed NOAA and Air Force documents, such as annual tropical cyclone summary reports, and interviewed NOAA and Air Force officials to discuss changes to Hurricane Hunter missions. Specifically, we interviewed officials from NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations and various National Weather Service offices, such as the National Hurricane Center, as well as officials from the Air Force Reserve Command and the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron.[7]

To examine the challenges NOAA and the Air Force have faced in completing Hurricane Hunter mission requirements, we analyzed the CARCAH data to determine how many mission requirements were completed or missed, and we reviewed relevant agency documents.[8] We used our interviews with the NOAA and Air Force officials described above to help identify challenges. We also conducted site visits to NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center and Keesler Air Force Base to observe Hurricane Hunter aircraft and interview Hurricane Hunter pilots, air crew members, and maintenance personnel about their experiences and the challenges they have faced. In addition, we visited the National Hurricane Center to interview the center’s leadership and forecasters about their experiences requesting mission requirements and using the data collected by the aircraft.

To examine NOAA’s and the Air Force’s plans to replace or upgrade their Hurricane Hunter aircraft and related challenges, we reviewed agency documents, such as NOAA’s 2022 aircraft recapitalization plan and Air Force documents about upgrading the capabilities of its aircraft.[9] In addition to the interviews described above, we interviewed officials from Commerce’s Office of Budget and acquisition officials from the Office of Marine and Aviation Operations about NOAA’s plans to acquire new Hurricane Hunter aircraft and related challenges. We also interviewed officials from the Interagency Council for Advancing Meteorological Services about efforts to identify new capabilities and technologies for the Hurricane Hunter aircraft. For more details about our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Hurricane Hunter Aircraft and Operations

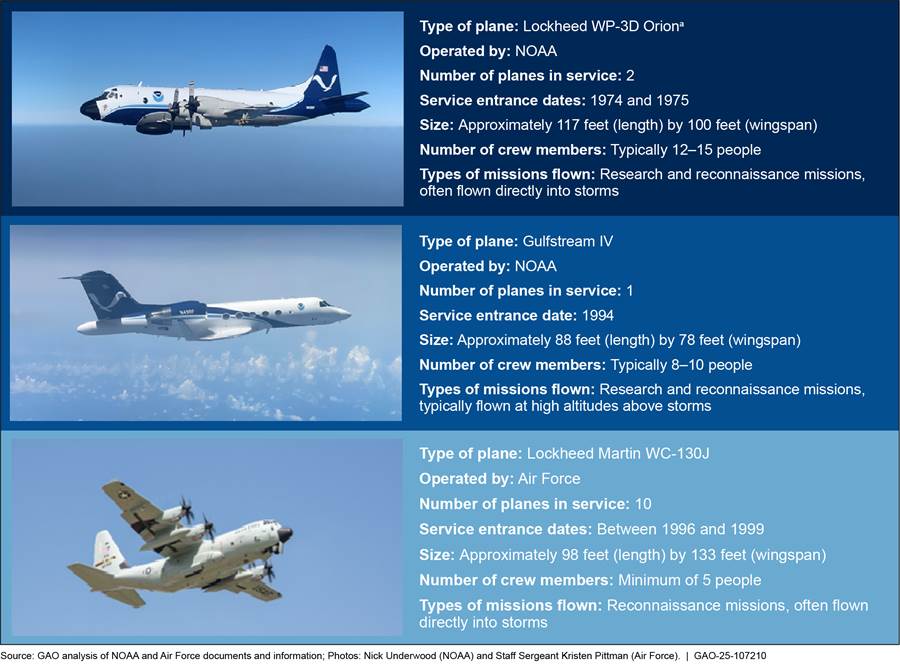

NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations operates the agency’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft, which consist of two Lockheed WP-3D Orion aircraft and one Gulfstream IV jet. The WP-3D aircraft fly directly into storms to complete their mission requirements, which include locating the center of tropical cyclones and collecting data on weather elements such as winds and atmospheric pressures. The Gulfstream IV flies at higher altitudes above storms to complete mission requirements such as collecting data from the upper atmosphere on the “steering” winds that affect a storm’s track. In addition, the Air Force Reserve’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron has 10 WC-130J Hercules Hurricane Hunter aircraft that fly into storms to collect weather data and complete other mission requirements.

As part of their Hurricane Hunter operations, NOAA and the Air Force conduct flights, known as reconnaissance missions, to collect data on tropical cyclones and winter storms to help improve weather forecasts. NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft also perform research missions to test new instruments or perform scientific experiments to better understand hurricanes and other types of storms. NOAA’s aircraft include some unique instruments and technologies that are not available on the Air Force’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft. For example, NOAA’s aircraft have Tail Doppler Radar, which provides a three-dimensional view of a storm’s wind structure and precipitation that can help to improve storm intensity forecasts. Figure 1 presents an overview of the different types of Hurricane Hunter aircraft that NOAA and the Air Force operate.

Figure 1: Overview of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and Air Force Hurricane Hunter Aircraft

aLockheed manufactured NOAA’s WP-3D Orion aircraft before changing its name to Lockheed Martin.

Historically, NOAA and Air Force Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions have focused primarily on tropical cyclones, with a limited number of reconnaissance missions also conducted during the winter season. The National Hurricane Center defines tropical cyclones as weather systems that develop over tropical or subtropical waters with organized deep convection and a closed surface wind circulation around a well-defined center.[10] NOAA classifies tropical cyclones based on maximum sustained wind speeds, as table 1 shows.

|

Classification |

Hurricane category |

Maximum sustained wind speed |

|

Tropical depression |

N/A |

38 miles per hour (mph) and below |

|

Tropical storma |

N/A |

39 to 73 mph |

|

Hurricane |

Category 1 |

74 to 95 mph |

|

Category 2 |

96 to 110 mph |

|

|

Major hurricane |

Category 3 |

111 to 129 mph |

|

Category 4 |

130 to 156 mph |

|

|

Category 5 |

157 mph and above |

Source: GAO analysis of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) information. | GAO‑25‑107210

aNOAA typically assigns names to tropical cyclones when they reach tropical storm status.

NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft are based at the agency’s Aircraft Operations Center in Lakeland, Florida. The Air Force’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft are based at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi. Depending on the location of the storm and their assigned mission requirements, NOAA and the Air Force may fly Hurricane Hunter missions from their home bases or forward deploy to other locations, such as Hawaii and St. Croix, to be better situated to fly into storms in the Pacific or Atlantic Oceans. A typical Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance flight includes air crew members (such as pilots and in-flight meteorologists) and, for NOAA flights, key maintenance personnel and researchers. The frequency of reconnaissance missions into storms can vary, with missions sometimes taking place around the clock to monitor storms in the days leading up to landfall. As part of their Hurricane Hunter operations, NOAA and the Air Force also perform scheduled and unscheduled maintenance on their aircraft and track data on the missions they fly.

Developing Weather Forecasts

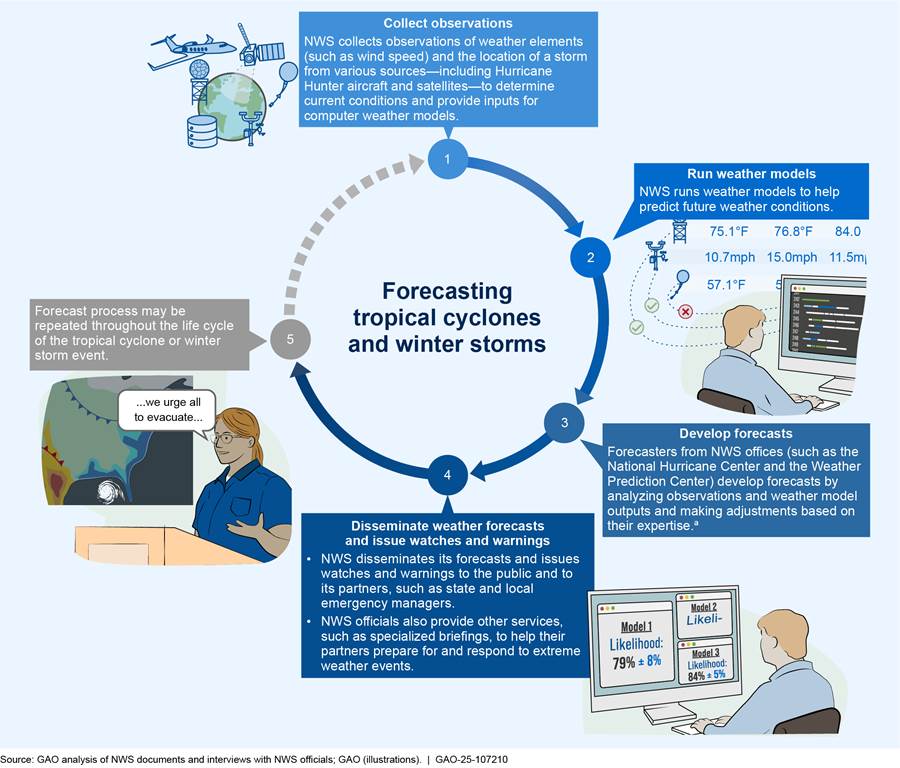

Various NWS offices use the reconnaissance data collected by Hurricane Hunter aircraft to help generate weather forecasts. For example, the National Hurricane Center is responsible for forecasting tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin and the Eastern North Pacific basin, including for storms that may affect the continental United States, Central America, and the Caribbean. The Central Pacific Hurricane Center is responsible for tropical cyclone forecasts in the Central Pacific basin, including for storms that may affect Hawaii.[11]

During the winter season, NWS’s Weather Prediction Center, in conjunction with local weather forecast offices, uses data collected by the Hurricane Hunters to develop precipitation forecasts for West Coast atmospheric river events and for East Coast winter storms. For example, including Hurricane Hunter data leads to improved precipitation forecasts for West Coast atmospheric river events, which helps to strengthen flood forecasts and support better water management decisions by reservoir operators, according to NOAA and Air Force documents.

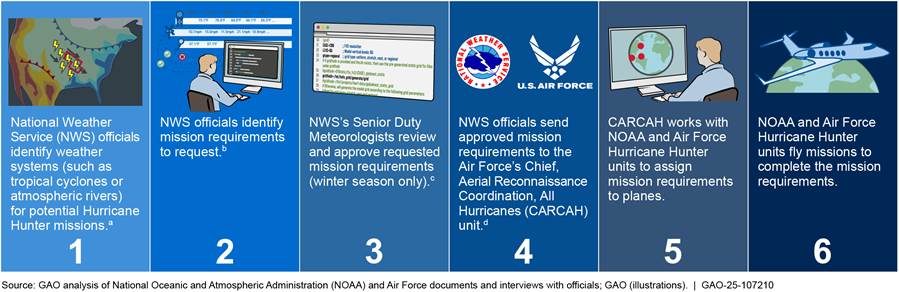

Figure 2 shows an overview of the process for forecasting tropical cyclones and winter storms.

Figure 2: The National Weather Service’s (NWS) General Process for Forecasting Tropical Cyclones and Winter Storms

aThe Weather Prediction Center serves as NWS’s leading national center for forecasting rainstorms and winter storms, among other things.

Hurricane Hunter Mission Requirements

Individual Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions are responsible for completing one or more mission requirements. These requirements may include various tasks, such as locating the center of a tropical cyclone and dropping instruments, known as dropsondes, directly into tropical cyclones or atmospheric rivers to obtain data on air temperature, pressure, humidity, and wind speed and direction. These mission requirements, and whether they are completed, serve as a primary unit of analysis used to track Hurricane Hunter performance.

Two national plans document the processes for requesting and completing aerial reconnaissance mission requirements.[12] These plans are known as the National Hurricane Operations Plan and the National Winter Season Operations Plan. NOAA and the Air Force coordinate with other federal agencies through the Interagency Council for Advancing Meteorological Services to develop and annually update the plans. The plans outline the roles and responsibilities of federal agencies involved in forecasting tropical cyclones and winter storms, including Hurricane Hunter aerial reconnaissance activities. For example, the plans describe which entities can request Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions and the procedures for doing so. They also describe steps NOAA and the Air Force should take to coordinate with each other and with other entities to complete the mission requirements (see fig. 3).[13]

aDuring the tropical cyclone season, forecasters from NWS’s National Hurricane Center and the Central Pacific Hurricane Center are responsible for completing the first two steps in this process. During the winter season, NWS’s Weather Prediction Center takes the lead on these steps for storms in the Atlantic basin, and a team led by NWS’s Environmental Modeling Center and the University of California, San Diego’s Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes takes the lead for atmospheric rivers in the Pacific basin.

bMission requirements are the key tasks, such as locating the center of tropical cyclones, that Hurricane Hunter missions must complete to obtain the information forecasters need to develop weather forecasts.

cSenior Duty Meteorologists are part of NWS’s National Centers for Environmental Prediction. Senior Duty Meteorologists are not involved in approving requests for mission requirements during the tropical cyclone season.

dCARCAH consists of a small group of Air Force Reserve personnel who are collocated with the National Hurricane Center to help coordinate Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions.

As outlined in the national plans, an Air Force unit known as the Chief, Aerial Reconnaissance Coordination, All Hurricanes (CARCAH), plays a central role in helping to coordinate Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions. CARCAH staff are collocated with NWS officials at the National Hurricane Center. CARCAH staff are responsible for coordinating with NOAA’s Office of Marine and Aviation Operations and the Air Force Reserve’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron to determine which aircraft will fly each mission to complete the mission requirements. As part of this coordination, CARCAH develops a “Plan of the Day,” which documents scheduled reconnaissance missions and the requirements each mission is supposed to complete.[14]

Hurricane Hunter Reconnaissance Missions Have Increased Since 2014 Because of New Responsibilities and Other Factors

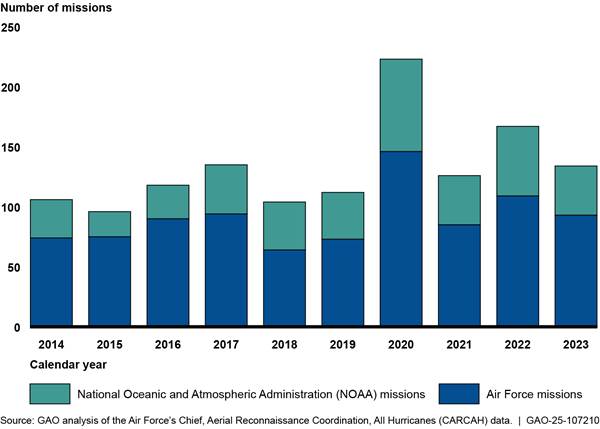

Since 2014, the number of Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions has increased for both tropical cyclone and winter seasons.[15] Tropical cyclone missions increased in part because of greater storm activity in the Atlantic basin, especially during the calendar year 2020 tropical cyclone season, and higher demand for data from forecasters. Winter season missions substantially increased beginning in FY 2020 after Hurricane Hunter responsibilities were expanded to include Pacific basin atmospheric river reconnaissance missions.[16]

Tropical Cyclone Reconnaissance Missions Increased in Part Because of Greater Storm Activity and Demand for Data

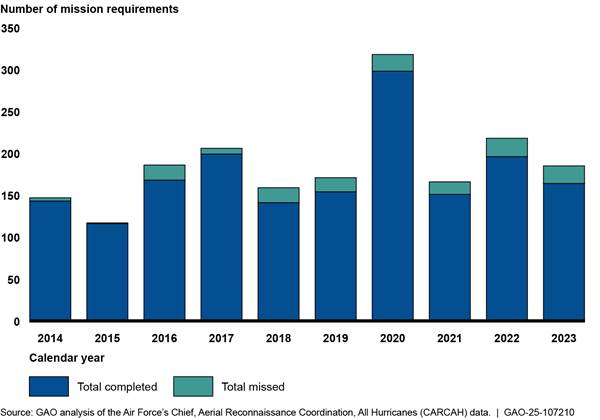

The number of reconnaissance missions flown by Hurricane Hunter aircraft during tropical cyclone seasons has grown since 2014. Specifically, after flying a total of 559 tropical cyclone reconnaissance missions during the first 5 calendar years of this period (2014 to 2018), NOAA and the Air Force flew a total of 762 such missions over the subsequent 5 calendar years (2019 to 2023), an increase of approximately 36 percent (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: Number of Hurricane Hunter Tropical Cyclone Reconnaissance Missions, Calendar Years 2014 Through 2023

Note: This figure includes tropical cyclone reconnaissance missions flown in the Atlantic and Pacific basins. The National Hurricane Operations Plan defines the Atlantic tropical cyclone season as June 1 through November 30 (the Eastern Pacific season begins on May 15). NOAA reported that the 2020 Atlantic tropical cyclone season set a record for the most named tropical cyclones in a season.

Two factors have largely driven this increase in tropical cyclone reconnaissance missions, according to our review of NOAA and Air Force data and documents and interviews with officials from both agencies:

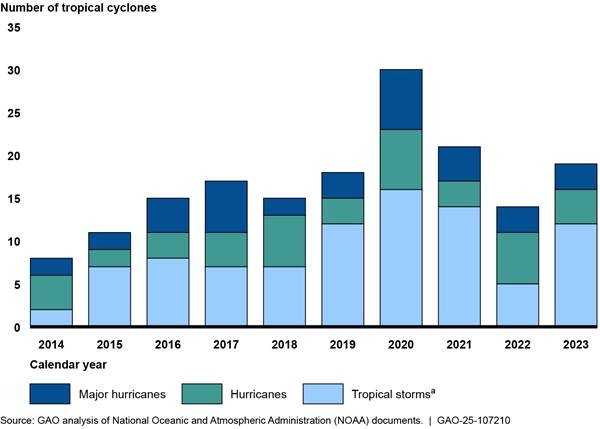

· Increased tropical cyclone activity in the Atlantic basin. The number of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin has increased over the past decade, according to NOAA documents. Specifically, calendar years 2014 through 2018 had 66 named tropical cyclones, while calendar years 2019 through 2023 had 102 named tropical cyclones, an increase of approximately 55 percent between these periods (see fig. 5).[17] NOAA and the Air Force fly reconnaissance missions into tropical cyclones or disturbances that could become tropical cyclones and pose a threat to land areas in the Atlantic basin, according to NOAA officials.[18]

Note: NOAA classifies hurricane-strength tropical cyclones into five categories (category 1 to category 5) based on a storm’s maximum sustained wind speed, with hurricanes rated category 3 or higher known as major hurricanes. For the purpose of this figure, “hurricanes” include categories 1 and 2 hurricanes, and “major hurricanes” include categories 3, 4, and 5 hurricanes. NOAA reported that the 2020 Atlantic tropical cyclone season set a record for the most named tropical cyclones in a season.

aThe tropical storms category includes four named subtropical storms in the 2019, 2020, and 2021 tropical cyclone seasons. Subtropical storms share some characteristics with tropical cyclones but differ meteorologically in other ways, such as how they derive their energy. Subtropical storms tend to generate lower wind speeds and less rain than tropical cyclones.

· Greater demand for reconnaissance data. Forecaster demand for aerial reconnaissance data has increased for multiple reasons, according to NOAA and Air Force documents and officials. For example, in a 2024 report to Congress, the Air Force reported that this demand increased in part because of the need to identify tropical cyclones earlier in their development, and in response to advances in weather models’ ability to integrate reconnaissance data.[19] In addition, NWS forecasters are requesting more frequent missions into storms to help identify changes in storm track and intensity, according to NOAA and Air Force officials.

There is also increased interest in obtaining data from NOAA’s Tail Doppler Radar. Our analysis of CARCAH’s Hurricane Hunter mission data found that NWS forecasters requested more than twice as many Tail Doppler Radar mission requirements from calendar years 2019 to 2023 (168 total mission requirements) than in the previous 5-year period (79 total mission requirements). Tail Doppler Radar missions began in 2012, but it took several years for the data to be fully assimilated into forecast models and to have a large positive impact on model performance, according to NOAA officials. Consequently, as NOAA’s data assimilation capabilities improved and the benefits of Tail Doppler Radar—such as helping forecasters map the structure of a storm’s winds—became more apparent, requests for Tail Doppler Radar mission requirements have increased.

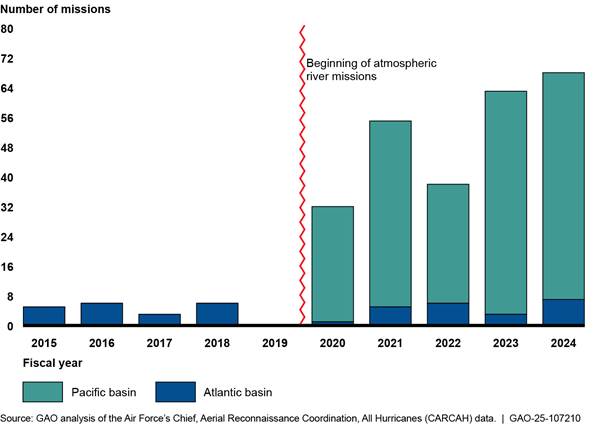

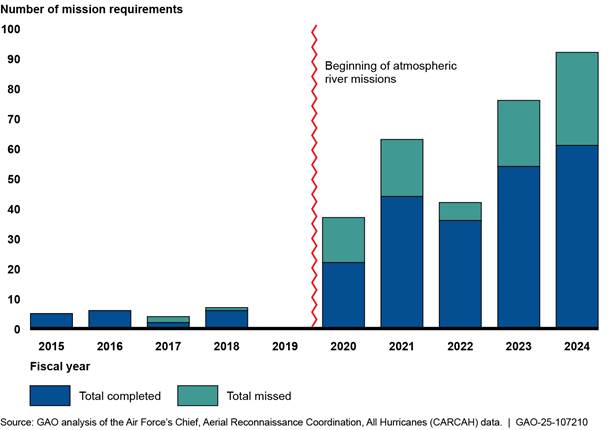

Winter Season Missions Increased Substantially Because of New Reconnaissance Responsibilities

The number of winter season reconnaissance missions flown by Hurricane Hunter aircraft has grown substantially since 2014, especially in the Pacific basin. For example, the aircraft flew a total of 20 reconnaissance missions during the FY 2015 through FY 2019 winter seasons, all of them by the Air Force in the Atlantic basin.[20] In contrast, during the FY 2020 through FY 2024 winter seasons, the NOAA and Air Force Hurricane Hunter aircraft collectively flew nearly 13 times more reconnaissance missions (256 total), mostly in the Pacific basin (see fig. 6).[21]

Figure 6: Number of Hurricane Hunter Winter Season Reconnaissance Missions in the Atlantic and Pacific Basins, Fiscal Years 2015 Through 2024

Note: This figure includes reconnaissance missions that NOAA and the Air Force flew under the National Winter Season Operations Plan. The plan defines the winter season as November 1 through March 31. Since the winter season crosses calendar years, we refer to winter seasons based on the fiscal year (FY) in which they occurred. No winter storms required reconnaissance missions in FY 2019. NOAA and the Air Force began flying Pacific basin atmospheric river reconnaissance missions in FY 2020 after these were added to the 2019 National Winter Season Operations Plan. Prior to FY 2020, NOAA and the Air Force also flew some research and training missions focused on Pacific basin atmospheric rivers, which are not included in this figure.

The expansion of Hurricane Hunter responsibilities to include Pacific basin atmospheric river reconnaissance missions largely drove the increase in winter season missions, according to NOAA and Air Force documents and interviews with officials. In 2016, a NOAA-led research effort showed that aerial reconnaissance data could help to improve atmospheric river forecasts for the West Coast, NOAA officials told us. Subsequently, beginning in 2019, the National Winter Season Operations Plans have included atmospheric river missions, according to these officials. As a result, NOAA and the Air Force began flying atmospheric river reconnaissance missions in the Pacific basin during the FY 2020 winter season.[22] Since then, the number of winter season missions in the Pacific basin has substantially exceeded those in the Atlantic basin.[23] In its 2024 draft report to Congress, NOAA predicted that winter operations could double over the next few years to further improve forecasts of atmospheric rivers.[24]

NOAA and the Air Force Face Staffing and Other Challenges to Completing Hurricane Hunter Mission Requirements

NOAA and the Air Force have missed an increasing number of Hurricane Hunter mission requirements since 2014, but they have not systematically tracked data on the reasons why. Both agencies face challenges that include limited aircraft availability and staffing shortages, according to NOAA and Air Force documents and officials, but neither agency has comprehensively assessed its Hurricane Hunter workforce needs.

Missed Mission Requirements Have Increased Since 2014, but NOAA and the Air Force Have Not Tracked the Reasons Why

Our analysis of CARCAH’s Hurricane Hunter mission data found that missed mission requirements have increased since 2014, but NOAA and the Air Force have not systematically tracked the reasons they missed the requirements to better understand trends. A missed requirement can occur when (1) the Hurricane Hunter flight tasked with the mission requirement does not fly or (2) the flight takes place but the requirement is not completed (e.g., the aircraft experiences a mechanical issue that forces the mission to end early).

|

Missed Mission Requirements During Hurricane Lee Maintenance issues grounded the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Gulfstream IV aircraft for an 11-day period from August to September 2023. This prevented NOAA from flying some high-altitude reconnaissance missions into Hurricane Lee, according to NOAA officials. At least one of these missions was instead assigned to an Air Force Hurricane Hunter aircraft as a backup. However, the Air Force aircraft also experienced maintenance issues and missed the mission requirements. Missed mission requirements can lead to a reduction in forecast quality, but the exact impact is difficult to determine, according to the officials. Hurricane Lee reached category 5 strength at its peak. It then weakened and made landfall as a post-tropical cyclone over Nova Scotia, Canada, with winds greater than 60 miles per hour. Source: GAO analysis of NOAA documents and interview with officials. | GAO‑25‑107210 |

When mission requirements are missed, forecasters have less data to inform their forecasts and are less confident in the forecast models, according to NOAA officials. Lower confidence in forecasts can hinder timely and effective storm preparations and affect evacuation decisions, according to NOAA documents and officials. For example, National Hurricane Center officials said that having lower confidence in forecasts can lead to larger evacuation areas, which can contribute to greater economic and social disruptions.

NOAA and the Air Force collectively missed more tropical cyclone season mission requirements from 2019 through 2023 than in the prior 5 years, according to our analysis (see fig. 7).[25] Specifically, from calendar years 2014 through 2018, they missed about 6 percent of mission requirements on average per tropical cyclone season (48 missed out of 815 total requirements).[26] In contrast, from calendar years 2019 through 2023, they missed about 9 percent on average per tropical cyclone season (95 missed out of 1,058 total requirements).[27]

Notes: This figure includes mission requirements that NOAA and Air Force Hurricane Hunter aircraft completed or missed. Hurricane Hunter guidance includes parameters for when a mission requirement should be considered missed, late, early, partially accomplished, or accomplished. For the purpose of our analysis, late, early, partially accomplished, and accomplished mission requirements are counted as completed requirements.

The National Hurricane Operations Plan defines the Atlantic tropical cyclone season as June 1 through November 30 (the Eastern Pacific season begins on May 15).

Missed mission requirements have happened more frequently during winter seasons, according to our analysis (see fig. 8). After winter operations expanded in FY 2020, NOAA and the Air Force collectively missed nearly 30 percent of mission requirements on average per winter season.[28] CARCAH officials told us that winter-specific weather issues, such as icing, and more limited maintenance capabilities at West Coast deployment locations, may have contributed to winter season mission requirements being missed more frequently.

Notes: This figure includes mission requirements that NOAA and Air Force Hurricane Hunter aircraft completed or missed. Hurricane Hunter guidance includes parameters for when a mission requirement should be considered missed, late, early, partially accomplished, or accomplished. For the purpose of our analysis, late, early, partially accomplished, and accomplished mission requirements are counted as completed requirements.

The National Winter Season Operations Plan defines the winter season as November 1 through March 31. Since the winter season crosses calendar years, we refer to winter seasons based on the fiscal year (FY) in which they occurred. For example, we refer to the winter season from November 1, 2014, through March 31, 2015, as the FY 2015 winter season.

NOAA and the Air Force have not systematically tracked the reasons why they missed Hurricane Hunter mission requirements:

· NOAA had not previously considered it necessary to track the reasons for missed mission requirements, in part because they happened less frequently in the past, according to officials. However, the officials said that, given the increasing challenges to completing mission requirements in recent years, the potential benefits of tracking these data have become more apparent.

· The Air Force did not historically track these data because they were not required to do so and did not consider it a priority, according to officials. However, in FY 2023, the Air Force began documenting some information about the reasons for missed mission requirements. As a result, Air Force officials said they could provide anecdotal explanations for some missed requirements, but they had limited data to assess trends over time to determine the significance of different factors contributing to missed requirements.

GAO’s key practices for evidence-based policymaking state that agencies should take actions to build the evidence they need to help them assess, understand, and identify opportunities to improve their results.[29] CARCAH has generally taken the lead on collecting and maintaining data on Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions, according to NOAA and Air Force officials. In September 2024, CARCAH officials said they were in the early stages of developing a prototype for a system that would track data on why mission requirements were missed. However, the officials said they would need further discussions with the NOAA and Air Force Hurricane Hunter units to determine the best way to proceed with this data collection effort and to avoid duplicative efforts. The CARCAH officials said they plan to have these discussions after the 2024 tropical cyclone season. They noted that they could end up determining that this information should be tracked by the NOAA and Air Force Hurricane Hunter units rather than CARCAH.

NOAA and Air Force officials said collecting data on the reasons why mission requirements are missed would be beneficial and could help to document challenges to Hurricane Hunter operations and inform decisions on how to dedicate resources to address the challenges. By working together to develop and implement a systematic process to track these data, NOAA and the Air Force would have the information needed to better understand the challenges facing their Hurricane Hunter operations so that they can identify and take actions to improve their ability to complete requirements.

Limited Aircraft Availability and Staffing Shortages Present Challenges, and NOAA and the Air Force Have Not Comprehensively Assessed Their Workforce Needs

Limited aircraft availability and staffing shortages have made it difficult for NOAA and the Air Force to complete mission requirements, according to our review of NOAA and Air Force documents and interviews with officials. Because of these challenges, NOAA and the Air Force are uncertain whether they can continue to meet their Hurricane Hunter responsibilities, particularly as demand for aerial reconnaissance increases. For example, in its 2024 draft report to Congress, NOAA stated that major investments are needed in both aircraft and human capital to continue supporting reconnaissance needs. In addition, the Air Force stated in its 2024 report to Congress that it is not positioned to fully meet its responsibilities under the National Hurricane Operations Plan and the National Winter Season Operations Plan, given the aircraft availability and staffing challenges it faces and the anticipated growth in demand. We found that NOAA and the Air Force have taken some steps to address these issues, but they have not comprehensively assessed workforce needs for their respective Hurricane Hunter programs.

Limited Aircraft Availability

Maintenance issues and limited backup options for aircraft have hindered the completion of mission requirements, according to NOAA and Air Force officials. For example, NOAA officials said maintenance issues can limit how many of its Hurricane Hunter aircraft are available for missions, such as when maintenance problems prevented all three NOAA aircraft from flying missions into Hurricane Idalia as it approached landfall in Florida in August 2023.

In its 2024 report to Congress, the Air Force reported that, despite the expansion of Hurricane Hunter winter season responsibilities, the number of Air Force Hurricane Hunter aircraft “has remained constant, challenging their abilities to cover these diverse and increasing demands.”[30] Air Force officials stated that at least three or four of their 10 WC-130Js are generally unavailable at any given time because of scheduled and unscheduled maintenance, which can lead to missed mission requirements.[31] For example, in 2019, the Air Force’s Hurricane Hunters were unable to fly multiple scheduled missions into Hurricane Dorian, a category 5 hurricane, in part because of maintenance issues, according to National Hurricane Center officials. As a result, the Air Force did not conduct flights into the hurricane for 18 hours and missed mission requirements that could have provided data to strengthen forecasts and help inform evacuation decisions.

NOAA and the Air Force have taken some steps to address maintenance challenges, according to agency documents and officials. For example:

· NOAA has changed when it performs scheduled maintenance on its Hurricane Hunter aircraft to reduce planned maintenance work during the tropical cyclone season.

· The Air Force has pre-positioned some maintenance supplies at its most used deployment locations to help fix the most common problems.[32]

· NOAA and Air Force aircraft sometimes fill in for each other if the other agency’s aircraft are unable to complete an assigned mission because of maintenance or other issues.

However, the expansion of Hurricane Hunter winter season responsibilities has required NOAA and the Air Force to perform operations at a high-tempo pace for a longer period each year than in the past. Officials said this has limited the time available for off-season repairs and contributed to more frequent maintenance issues. As a result, NOAA is seeing more abnormal problems with its aircraft, such as having to change propellers more frequently, because of increased usage and the aircraft’s advanced age, according to agency officials.[33]

Limited aircraft backup options also contribute to missed mission requirements. For example, NOAA relies on its one Gulfstream IV jet to perform high-altitude reconnaissance missions. When this aircraft cannot fly because of maintenance or other issues, its mission requirements may be missed because limited backup options are available. This occurred multiple times during the most recent 2024 tropical cyclone season, such as when maintenance issues caused the Gulfstream IV to miss flying two missions into Hurricane Helene and no backup aircraft were available, according to NOAA officials. Determining the exact impact of these missed missions is difficult, but the officials said it is possible that they led to reduced forecast quality.

NOAA has an agreement with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration to use its high-altitude Gulfstream V jet in a backup capacity, according to NOAA’s 2022 aircraft recapitalization plan. However, this jet has limited availability and does not have the same capabilities, such as Tail Doppler Radar, according to the plan. The Air Force’s WC-130Js can also sometimes fill in when NOAA’s Gulfstream IV is unavailable, but the WC-130Js must fly at lower altitudes and have more limited data collection capabilities. NOAA plans to acquire two new Gulfstream G550 jets to replace its Gulfstream IV and provide greater backup capabilities for high-altitude missions. However, the new jets may not be ready until 2025 and 2028, as we discuss below.

Staffing Shortages

|

Staffing Shortages During Hurricane Ernesto In August 2024, a staff shortage forced the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to delay deploying its Gulfstream IV aircraft by 2 days during the early stage of Hurricane Ernesto. This staff shortage occurred after one of NOAA’s flight directors, who serves as an in-flight meteorologist, was unavailable to fly because of a family emergency and no backup staff were available. As a result, NOAA only had enough flight directors to staff two of its three Hurricane Hunter aircraft and was unable to complete some mission requirements. Source: GAO analysis of NOAA written responses. | GAO‑25‑107210 |

NOAA and the Air Force have also faced challenges in completing mission requirements because of staffing shortages exacerbated by increased demand for Hurricane Hunter missions. Staffing levels have not increased concurrent with the increase in missions and expansion of Hurricane Hunter responsibilities since 2014, according to NOAA and Air Force officials. For example, the Air Force’s Hurricane Hunter resources, including personnel, have not changed while demand has increased over the past several years for tropical cyclone and winter seasons, according to its 2024 report to Congress.[34] Hurricane Hunter operations now occur nearly year-round since the addition of atmospheric river missions, but the Air Force’s staffing structure is still largely based on the needs of the traditional 6-month tropical cyclone season, according to the report and Air Force officials.

NOAA’s staffing shortages have hindered the completion of mission requirements as Hurricane Hunter personnel struggle to manage their increasingly heavy workloads, according to NOAA officials. In its draft report to Congress, NOAA highlighted challenges with having enough pilots for its Hurricane Hunter aircraft. Specifically, NOAA reported that before the 2023 tropical cyclone season, seven of 11 WP-3D pilot positions (64 percent) and four of seven Gulfstream IV pilot positions were filled (57 percent).[35] In addition, NOAA’s air crews are thinly staffed with limited backup options. For example, in 2023, NOAA stopped flying missions into Hurricane Lee because the crew had met their flight hour limits (120 hours per 30-day period), and NOAA did not have other staff available to provide relief.[36] According to NOAA officials, the agency is often one illness or injury away from having to cancel missions. Also, NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter maintenance personnel told us that they have been thinly staffed for years, resulting in unsustainable heavy workloads that have contributed to greater burnout for personnel.[37]

The Air Force has faced similar staffing shortages among its air crew and maintenance personnel. Officials said these shortages have caused the Air Force to rely on a smaller pool of personnel to complete missions and contributed to increased fatigue and burnout for those staff. For example, Air Force officials stated that the Air Force missed some mission requirements during the 2023 tropical cyclone season because its Hurricane Hunter air crew members faced high levels of fatigue.

Air Force maintenance staffing shortages have also presented challenges to completing mission requirements. For example, the Air Force had to cancel a mission in December 2023 because of limited maintenance personnel availability, according to officials.[38] In its 2024 report to Congress, the Air Force stated that its Hurricane Hunter unit is authorized 110 maintenance personnel specifically to support missions, but vacancies, training, and medical issues can substantially reduce the number of available personnel.[39] In addition, the Air Force sometimes uses maintenance personnel from other units to help maintain the Hurricane Hunter aircraft when needed, according to officials.

The Air Force’s staffing challenges are further complicated by having to balance a mix of full-time personnel and part-time reserve personnel for the Hurricane Hunter unit, as well as the different sources of funding that are used for each group, according to officials.[40] For example, in 2023, the Air Force’s 403rd Wing—which includes the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron—faced funding challenges that limited the use of Hurricane Hunter reserve personnel beginning in July, well before the end of the tropical cyclone season, according to officials. In addition, the unit’s reserve personnel are sometimes unavailable to support Hurricane Hunter missions because of other commitments, such as their civilian jobs. These challenges have limited the Hurricane Hunter unit’s ability to deploy for some reconnaissance missions and led to heavier workloads and increased burnout for the unit’s full-time staff, according to officials. Air Force officials told us that having a better balance of full-time staff and part-time reserve personnel could help them meet the increasing demand for Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions.

NOAA and the Air Force have taken steps to reduce the impact of staffing shortages on Hurricane Hunter operations, but some of these steps have placed additional burdens on existing staff. For example, NOAA has increased the use of waivers to allow crew members to exceed flight hour limits in recent years and has hired contractors to help fill some maintenance staffing gaps, according to agency officials. The agency has also sometimes asked previous Hurricane Hunter pilots serving in leadership positions elsewhere in NOAA to fly Hurricane Hunter missions when needed to help fill staffing gaps. As part of its FY 2025 budget request, NOAA requested funding for additional personnel to support the new Hurricane Hunter Gulfstream G550 jets it plans to acquire. In addition, the Air Force has deployed smaller maintenance crews for some missions in response to staffing shortages, but this can increase the workload for those personnel, according to Air Force officials.

Under the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) Human Capital Framework, agencies are directed to plan for and manage their current and future workforce needs.[41] OPM has reported that one outcome of such actions is a workforce that is positioned to address and accomplish evolving priorities and objectives based on anticipated and unanticipated events. In addition, GAO’s principles for effective strategic workforce planning state that agencies should determine the critical skills and competencies needed to achieve their missions and goals.[42] As described above, the increased demand for reconnaissance missions and the expansion of Hurricane Hunter responsibilities in recent years has presented new challenges to the ability of the NOAA and Air Force Hurricane Hunter workforces to complete mission requirements.

NOAA and the Air Force have examined staffing needs for some positions, but they have not comprehensively assessed their Hurricane Hunter workforces to determine whether changes to staffing levels or workforce structure are needed to manage this increased demand. For example:

· NOAA has examined staffing needs for its Hurricane Hunter pilots and navigators—the two Hurricane Hunter positions that are filled by members of the NOAA Commissioned Officer Corps.[43] In 2023, NOAA issued a plan focused on staffing for these positions, and in 2024 it hired a contractor to assess the NOAA Commissioned Officer Corps’ aviation workforce.[44] This assessment may include Hurricane Hunter pilots and navigators, but it will not cover other Hurricane Hunter air crew and maintenance personnel positions filled by NOAA civilian employees, according to NOAA officials. The officials said that assessing the rest of the Hurricane Hunter workforce would be helpful to gauge current and future workforce needs, but they had not yet conducted such an assessment in part because of resource limitations.

· The Air Force published a study in March 2020 that examined staffing requirements for some maintenance personnel involved in supporting the different C-130 aircraft models flown by units throughout the Air Force Reserve Command, including the Hurricane Hunter unit.[45] However, the Air Force has not conducted a similar assessment of its Hurricane Hunter air crew workforce. Air Force officials stated that the Air Force had not previously conducted such an assessment because the Hurricane Hunter unit’s current staffing structure was established by Congress in 1996. However, Air Force officials said that assessing their Hurricane Hunter air crew workforce would be useful to help them better understand staffing needs under current conditions, especially given the expansion of Hurricane Hunter responsibilities.

Comprehensively assessing their Hurricane Hunter workforces would help inform efforts by NOAA and the Air Force to ensure that they have the appropriate staffing levels and workforce structure in place to meet the growing demand for Hurricane Hunter missions.

Insufficient Communication and Other Challenges Have Hampered Efforts to Replace or Upgrade Hurricane Hunter Aircraft

NOAA has developed plans to acquire six new Hurricane Hunter aircraft, but the agency has faced funding-related challenges and other issues that pose risks to the success of these acquisition efforts. The Air Force has identified some necessary upgrades to improve the capabilities of its Hurricane Hunter aircraft, but it has experienced implementation challenges and delays. In addition, insufficient communication between senior leaders from NOAA and the Air Force has further hampered efforts to replace or upgrade the Hurricane Hunter aircraft.

NOAA Plans to Acquire New Aircraft but Has Faced Several Challenges

In 2022, NOAA published its plan for replacing its Hurricane Hunter aircraft. As outlined in this plan, NOAA seeks to acquire six new Hurricane Hunter aircraft: two Gulfstream G550 high-altitude jets and four C-130J aircraft. The first G550 jet would replace NOAA’s current Gulfstream IV jet, which is scheduled to be retired in May 2025. The second G550 jet is intended to provide greater backup capabilities for high-altitude missions and allow NOAA to simultaneously fly these missions into multiple storms. Two of the C-130J aircraft would replace NOAA’s current WP-3D aircraft, which are scheduled to be retired by 2030. The other two C-130Js would help NOAA expand its capacity to conduct reconnaissance missions and provide greater backup capabilities.

However, NOAA has encountered funding and related challenges, as well as other challenges that pose risks to its acquisition efforts.

Funding Needs and Related Challenges

NOAA has received nearly $1 billion in appropriations for the new Hurricane Hunter aircraft, as of January 2025. However, agency officials said NOAA needs substantial additional funding to complete its acquisition plans. NOAA is further along in its efforts to acquire the G550 jets than the C-130J aircraft (see table 2).

Table 2: Status of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Hurricane Hunter Aircraft Acquisitions, as of January 2025

|

Aircraft |

Acquisition status |

Funding received |

Additional funding needed |

|

G550s |

First G550: Gulfstream has manufactured the first G550 and is modifying it to meet NOAA’s needs. Estimated delivery date is April 2025, after which NOAA will make additional modifications. NOAA estimates that this aircraft will be ready to fly missions by July 2025. |

Over $160 million total from annual appropriations between fiscal year 2018 and fiscal year 2023. |

None |

|

Second G550: NOAA awarded the contract in July 2024. Gulfstream is no longer manufacturing new G550s, so NOAA will acquire a used G550 that Gulfstream will modify to meet NOAA’s needs. Estimated delivery date is spring 2028. |

Approximately $105 million total from the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and fiscal year 2024 annual appropriations. |

Approximately $21 million to $23 milliona |

|

|

C-130Js |

NOAA awarded pre-production contracts in 2023 to secure spots in Lockheed Martin’s production line for the first two of four planned C-130Js. NOAA awarded the base contract to begin acquiring these two aircraft in September 2024, with an estimated delivery date of 2030. |

Approximately $727 million from fiscal year 2023 and fiscal year 2025 disaster supplemental funding. |

Approximately $678 millionb |

Source: GAO analysis of relevant laws and NOAA documents and interviews with agency officials. | GAO‑25‑107210

aNOAA officials said that the final cost of the second G550 may vary depending on the cost of the used aircraft that the agency acquires.

bNOAA officials said that the amount of additional funding needed for the C-130Js could increase because of inflation if the funding is provided after fiscal year 2025.

NOAA officials stated that NOAA does not need additional funding to acquire the first G550 jet but requires additional funding to complete the acquisition of the second G550. NOAA has received approximately $105 million for the second G550 and requested an additional $21 million for the acquisition of this aircraft in its FY 2025 budget request. NOAA officials said that more funding could be needed to complete this acquisition depending on the final cost of the used G550 aircraft that the agency acquires.

NOAA will require substantial additional funding to complete its plans to acquire the four C-130J aircraft. NOAA officials estimated this acquisition effort would cost a total of approximately $1.4 billion, with approximately $678 million remaining to be funded as of January 2025. NOAA officials stated that obtaining the necessary funding to acquire the new C-130J aircraft has been difficult, in part because of the challenging budget environment the agency has faced and the size of the acquisition effort.

NOAA’s 2022 aircraft recapitalization plan identified limited resources as a challenge and stated that the agency would “prioritize options to acquire additional aircraft through future budget requests.” However, NOAA’s budget justifications since FY 2022 have not included any funding requests specifically for the C-130J acquisition effort, according to our review of these documents. NOAA budget office officials said that the agency identified this acquisition effort as an unfunded requirement in its FY 2023 and FY 2024 budget submissions to Commerce. However, NOAA could not request funding for this effort in those submissions because of the magnitude of the funding requirement and constraints associated with the annual budget guidance that NOAA received from Commerce and the Office of Management and Budget, according to the officials.[46]

NOAA budget officials stated that Commerce and NOAA sought to include funding for the C-130J acquisition effort in the FY 2025 budget request, but it was not included because the President had separately requested funding for new Hurricane Hunter aircraft as part of the FY 2024 domestic supplemental request announced in October 2023. In August 2024, the director of Commerce’s Office of Budget told us that Commerce was waiting to see if Congress would act on the FY 2024 domestic supplemental request before deciding whether to include funding for the C-130J acquisition effort in future budget requests. In November 2024, the President submitted a FY 2025 disaster supplemental request that called for $733 million in funding to NOAA for the acquisition of three new Hurricane Hunter aircraft to replace NOAA’s existing WP-3D aircraft. Subsequently, in December 2024, Congress appropriated $399 million in disaster supplemental funding to NOAA for the acquisition of Hurricane Hunter aircraft.[47]

GAO’s key practices for evidence-based policymaking state that federal organizations should identify resources, including funding, needed to achieve goals, and that they should communicate relevant information on their learning and results to key stakeholders.[48] Moreover, federal standards for internal control call on agency management to externally communicate the information necessary to achieve an agency’s objectives.[49] After the President included funding for new Hurricane Hunter aircraft in the FY 2025 disaster supplemental request, NOAA received additional appropriations from Congress for this acquisition effort. However, as described above, NOAA will still need to request substantial additional funding to complete its plans to acquire four C-130J aircraft.

Given the funding uncertainty NOAA faces, the agency’s annual budget requests provide a consistent, high-profile mechanism it can use to regularly communicate its funding needs for Hurricane Hunter aircraft acquisitions to Congress and other stakeholders. By including information about NOAA’s funding needs for Hurricane Hunter aircraft acquisitions in the agency’s annual budget requests going forward, Commerce could help ensure Congress and other stakeholders are more fully informed when making funding decisions about the agency’s Hurricane Hunter program.

Other Challenges

NOAA has also experienced manufacturing and technical challenges that pose risks to the success of its acquisition efforts, according to agency documents and officials:

· Manufacturing challenges. Gulfstream experienced delays in manufacturing the first G550 jet that caused it to miss the original May 2024 delivery date. Gulfstream is now scheduled to deliver the first G550 to NOAA in April 2025. After delivery, NOAA will spend additional time modifying the aircraft, such as by adding special equipment, before it is ready to fly Hurricane Hunter missions. Because NOAA is scheduled to retire its Gulfstream IV jet in May 2025, the delay in delivering the new G550 jet could result in NOAA not having an aircraft available to perform high-altitude missions at the start of the 2025 tropical cyclone season.

· Technical challenges. NOAA has not yet determined how it will install Doppler radar, which provides critical information for tropical cyclone forecasts, on the new C-130J aircraft it plans to acquire. NOAA included funding to analyze options for installing Doppler radar as part of the base contract it awarded for the first two C-130J aircraft in September 2024, according to NOAA officials.

The Air Force Has Identified Needed Upgrades to Its Hurricane Hunter Aircraft but Has Faced Implementation Challenges

The Air Force does not have plans to replace its 10 WC-130J Hurricane Hunter aircraft but has identified some necessary upgrades to improve the capabilities and technologies on the aircraft, according to Air Force documents and officials. In 2023, the Air Force developed a capabilities roadmap to help guide efforts to upgrade its Hurricane Hunter aircraft. This roadmap described the sensors and data formats in use on the Hurricane Hunter aircraft as “antiquated” and stated that the Air Force is unable to collect some data required under the National Hurricane Operations Plan because of the lack of modern technology on its aircraft.

For example, the roadmap identified long-standing communications bandwidth and reliability issues as one of the most significant limiting factors facing the aircraft. Air Force officials said these issues were first identified in 2011. The roadmap states that these issues prevent the Air Force from transmitting some data to NWS forecasters in real time, forcing the Air Force to wait until the aircraft land to transmit these data. In contrast, NOAA’s Hurricane Hunter aircraft have greater capabilities to transmit data to forecasters in real time during missions.

To help determine which technological upgrades its aircraft need, the Air Force participates in an interagency working group on aerial reconnaissance equipment, along with NOAA and other entities. This group meets annually and develops lists of prioritized capabilities and technologies for the Hurricane Hunter aircraft, such as new sensors or radar, which the Air Force then evaluates to determine what it will pursue.

However, the Air Force has faced challenges upgrading the capabilities and technologies on its Hurricane Hunter aircraft because of funding restrictions and its internal processes. The Air Force often uses National Guard and Reserve Equipment Appropriations funds to upgrade the Hurricane Hunter aircraft, but those funds include restrictions that limit how they can be used and the types of equipment that can be procured, according to Air Force officials. For example, Air Force officials said that they cannot use the funds to procure new instruments or technologies that are still in the research and development phase. In addition, the funds cannot be used to help sustain equipment after it has been acquired, according to the officials. In contrast, NOAA and Air Force officials said that it is much easier for NOAA to add new instruments and technologies, including those still in the research and development phase, to its Hurricane Hunter aircraft.

In addition, Air Force officials described the process to make modifications to the Hurricane Hunter aircraft, such as installing new technologies or equipment, as cumbersome and slow. To request an upgrade, the Hurricane Hunter unit submits a Form 1067, also known as a modification proposal, to the Air Force Reserve Command, where it undergoes a series of reviews and is considered for potential funding. Air Force officials said that this process can be time consuming and that it can take years, in some cases more than a decade, for the Air Force to add new capabilities to its aircraft. For example, Air Force officials said they have tried unsuccessfully for many years to improve the communications bandwidth of its Hurricane Hunter aircraft and add Wi-Fi. As of October 2024, officials said that the Air Force had begun testing equipment to improve the communications capabilities of its Hurricane Hunter aircraft, with an estimated permanent installation date of May 2026.

GAO’s key practices for evidence-based policymaking state that federal organizations should assess their environment to identify internal and external factors that could affect their ability to achieve goals.[50] After identifying these factors, organizations should then define strategies to address or mitigate the factors. The challenges that the Air Force has faced in upgrading the capabilities of its Hurricane Hunter aircraft can limit the information that the Air Force provides to forecasters. By reviewing its processes to assess potential barriers to upgrading Hurricane Hunter aircraft capabilities and defining strategies to mitigate those barriers, where appropriate, the Air Force would better ensure its aircraft can provide the data NWS forecasters need to produce high-quality forecasts.

NOAA and Air Force Senior Leadership Have Not Communicated on Efforts to Replace or Upgrade Hurricane Hunter Aircraft

Insufficient communication between NOAA and Air Force senior leadership has also hampered efforts to replace or upgrade the Hurricane Hunter aircraft. Specifically, NOAA and Air Force officials said that senior leaders from their agencies have not communicated with each other about their plans for the aircraft. This presents challenges since decisions about investments in Hurricane Hunter resources, such as aircraft acquisitions and upgrades, are generally made at the senior leadership level.

Senior NOAA officials said they have tried unsuccessfully to reach out to the Air Force about its plans for its Hurricane Hunter aircraft and stated they were unsure which Air Force leaders they should communicate with on this topic. In the absence of such communications, the officials said they do not know what the Air Force’s long-term plans are for its Hurricane Hunter aircraft, which has made it more difficult for NOAA to determine the needs and requirements for its own aircraft recapitalization efforts. For example, a senior NOAA leader said that knowing more about the Air Force’s plans to invest in its Hurricane Hunter aircraft or acquire new aircraft would help NOAA determine the total number of new C-130J aircraft it will need to acquire.[51]

According to NOAA officials, it is important to ensure that NOAA and Air Force investments in Hurricane Hunter resources are coordinated and aligned as part of a whole-of-government approach. However, officials from both agencies confirmed that NOAA and Air Force senior leaders have not communicated with each other about these issues because there is no mechanism in place to facilitate such communications. In the absence of such communications, a senior NOAA leader described the situation as analogous to building the two halves of a house separately without discussing how the plumbing, wires, and other systems will connect with each other. In contrast, NOAA and Air Force officials spoke positively about the ways their Hurricane Hunter units work together and communicate on operational issues, such as working through CARCAH to coordinate daily missions and holding joint annual meetings to discuss lessons learned from the prior season.

GAO’s key practices for evidence-based policymaking state that involving stakeholders, such as other federal agencies, is often vital to the success of federal efforts.[52] Such engagement should happen early and often and can help agencies align their goals and strategies with those of others involved in achieving similar outcomes. In addition, federal standards for internal control call on agency management to externally communicate the information necessary to achieve the agency’s objectives.[53]

NOAA and Air Force senior officials we interviewed agreed that improving senior-level communication about the Hurricane Hunters would be beneficial. By establishing a mechanism for senior leaders to regularly communicate about their plans and resources, NOAA and the Air Force could better ensure that decisions about the Hurricane Hunters make the most efficient and effective use of federal resources to meet the nation’s need for aerial reconnaissance data to help communities better prepare for destructive storms.

Conclusions

The NOAA and Air Force Hurricane Hunters play a critical role in helping to improve the accuracy of weather forecasts for tropical cyclones and winter storms. Forecaster demand for the aerial reconnaissance data the Hurricane Hunters collect has grown in recent years and the scope of Hurricane Hunter responsibilities has expanded, leading to a substantial increase in Hurricane Hunter operations.

These developments have strained the ability of NOAA and the Air Force to meet their Hurricane Hunter responsibilities. NOAA and the Air Force have missed an increasing number of Hurricane Hunter mission requirements since 2014, but they have not systematically tracked data on the reasons why. Developing a process to track these data would help the agencies better understand the challenges their Hurricane Hunter missions face and identify actions they could take to reduce missed mission requirements and improve operations.

In addition, the increased demand for reconnaissance missions and the expansion of Hurricane Hunter responsibilities have exacerbated staffing shortages, making it more difficult to complete mission requirements, according to NOAA and Air Force documents and officials. However, neither agency has comprehensively assessed their respective Hurricane Hunter workforces to determine their staffing needs. Conducting such an assessment would help inform efforts by NOAA and the Air Force to ensure they have the appropriate staffing levels and workforce structure to meet the growing demand for Hurricane Hunter missions.

NOAA and the Air Force have also faced challenges in their efforts to replace or upgrade their aircraft. For example, funding uncertainty poses risks to NOAA’s acquisition of new Hurricane Hunter aircraft. By including information on the funding NOAA needs in its annual budget requests, Commerce could help ensure Congress and other stakeholders are better informed about NOAA’s aircraft funding needs. In addition, the Air Force has identified needed upgrades that would enable its Hurricane Hunter aircraft to better collect key data, but it is hampered by processes that agency officials described as cumbersome and slow. Reviewing its processes to assess potential barriers and defining strategies to mitigate these barriers would help the Air Force move forward on these upgrades in a timelier manner.

Insufficient communication between NOAA and Air Force senior leadership about Hurricane Hunter plans and resources has also hampered efforts to replace or upgrade the Hurricane Hunter aircraft. By establishing a mechanism to facilitate regular communication about their plans and resources, NOAA and the Air Force could better ensure they make the most efficient and effective use of federal resources to meet the nation’s need for aerial reconnaissance data on destructive storms.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of eight recommendations, including four to the Air Force, three to NOAA, and one to the Department of Commerce. Specifically:

The Commander of the Air Force Reserve Command should, in coordination with the Administrator of NOAA, develop and implement a process to systematically track data on the reasons Hurricane Hunter mission requirements are missed. (Recommendation 1)

The Administrator of NOAA should, in coordination with the Commander of the Air Force Reserve Command, develop and implement a process to systematically track data on the reasons Hurricane Hunter mission requirements are missed. (Recommendation 2)

The Commander of the Air Force Reserve Command should perform a comprehensive assessment of its Hurricane Hunter workforce, including examining staffing levels and workforce structure, to inform future workforce planning. (Recommendation 3)

The Administrator of NOAA should perform a comprehensive assessment of its Hurricane Hunter workforce, including examining staffing levels and workforce structure, to inform future workforce planning. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that NOAA’s funding needs for Hurricane Hunter aircraft acquisitions are regularly communicated to relevant stakeholders, including Congress, such as by including information on these needs in its annual budget requests. (Recommendation 5)

The Commander of the Air Force Reserve Command should assess whether Air Force processes create barriers to upgrading Hurricane Hunter aircraft capabilities and define strategies to mitigate any identified barriers, as appropriate. (Recommendation 6)

The Administrator of NOAA should, in coordination with the Commander of the Air Force Reserve Command, establish a mechanism for their senior leaders to regularly communicate and share information about Hurricane Hunter plans and resources. (Recommendation 7)

The Commander of the Air Force Reserve Command should, in coordination with the Administrator of NOAA, establish a mechanism for their senior leaders to regularly communicate and share information about Hurricane Hunter plans and resources. (Recommendation 8)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Commerce and Defense for review and comment. NOAA, on behalf of Commerce, and the Department of Defense provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendixes II and III, respectively, and which we summarize below. NOAA and the Department of Defense also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In their written comments, NOAA and the Department of Defense agreed with our recommendations and described actions they plan to take to address them. These actions include working together to develop a process to track the reasons for missed mission requirements and to establish senior-level communications and information-sharing protocols for their Hurricane Hunter programs. NOAA stated that it believes its planning process for acquiring new Hurricane Hunter aircraft addressed our recommendation to assess its Hurricane Hunter workforce. As we discuss in the report, while NOAA examined staffing needs for some Hurricane Hunter positions, we continue to believe that a comprehensive workforce assessment is needed.

In addition, NOAA provided three general comments about our report, which we respond to below:

1) Assessing the cost-effectiveness of Hurricane Hunter flights. The analysis NOAA suggested was beyond the scope of our work.

2) NOAA’s atmospheric river missions. We added information in our report regarding research and training missions NOAA and the Air Force flew before FY 2020 that focused on Pacific basin atmospheric rivers.

3) Presenting NOAA and the Air Force as a combined Hurricane Hunter entity. We agree that NOAA and the Air Force each have unique Hurricane Hunter programs, and those programs work together to meet the nation’s aerial weather reconnaissance needs. Throughout the report, we describe the unique processes, strengths, and challenges associated with each agency’s Hurricane Hunter program, as well as shared challenges. To provide additional context regarding each agency’s Hurricane Hunter program, we added agency-specific data to our report to present the number of winter season reconnaissance missions that each agency flew and the number of mission requirements that each agency missed.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Commerce, the Secretary of Defense, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-3841 or johnsoncd1@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Cardell D. Johnson

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

This report examines (1) how the number of Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions has changed since 2014, (2) the challenges the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Air Force have faced in completing Hurricane Hunter mission requirements since 2014, and (3) the plans NOAA and the Air Force have developed to replace or upgrade their Hurricane Hunter aircraft and the challenges they have faced in implementing these efforts.

To examine how the number of Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions has changed since 2014, we analyzed data on Hurricane Hunter missions for both tropical cyclone and winter seasons. Specifically, we analyzed data from the Air Force’s Chief, Aerial Reconnaissance Coordination, All Hurricanes (CARCAH) unit on the number of reconnaissance missions flown during tropical cyclone seasons in calendar years 2014 through 2023 and winter seasons in fiscal years 2015 through 2024.[54] We chose these years to provide a picture of Hurricane Hunter activities for the most recent full decade.[55]

To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed the data for completeness and conducted manual testing to look for discrepancies. We also interviewed and obtained written responses from CARCAH officials about the reliability of the data and any discrepancies or outliers that we encountered. Based on the results of these steps, we determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing changes in the number of Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions.

We also reviewed NOAA and Air Force documents and interviewed NOAA and Air Force officials to better understand how the number of Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions has changed and the factors that have contributed to those changes. For example, we reviewed NOAA’s draft and the Air Force’s final reports to Congress on resources for their Hurricane Hunter programs, as well as the most recent and some previous editions of the annual National Hurricane Operations Plan and the National Winter Season Operations Plan.[56] We also reviewed NOAA’s annual tropical cyclone summary reports from 2014 through 2023 to determine changes in storm activity in the Atlantic basin.[57]

We conducted group interviews with officials from various NOAA and Air Force entities to discuss changes to Hurricane Hunter reconnaissance missions and to obtain their perspectives on historical trends.[58] For example, we interviewed:

· NOAA officials from the Office of Marine and Aviation Operations and from several National Weather Service offices, including the National Hurricane Center, the Central Pacific Hurricane Center, the Weather Prediction Center, the Environmental Modeling Center, and the National Centers for Environmental Prediction Central Operations office.

· Air Force officials from the Air Force Reserve Command and the 403rd Wing, including officials from the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron.

To examine the challenges NOAA and the Air Force have faced in completing Hurricane Hunter mission requirements, we analyzed CARCAH’s data on Hurricane Hunter missions, described above, to determine the number of completed and missed mission requirements.[59] We reviewed the National Hurricane Operations Plan and the National Winter Season Operations Plan to understand the processes for requesting and completing mission requirements and the responsibilities of the different entities involved. In addition, we reviewed NOAA and Air Force documents, such as their Hurricane Hunter resource reports to Congress described above, to identify challenges that NOAA and the Air Force have faced with completing Hurricane Hunter mission requirements.

We used our interviews with NOAA and Air Force officials described above to help identify and learn more about these challenges. Additionally, we interviewed three external entities—the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes, the National Science Foundation’s National Center for Atmospheric Research, and the National Weather Association—to obtain outside perspectives on Hurricane Hunter operations and challenges.