VETERANS BENEFITS

More Thorough Planning Needed to Help Better Protect Veterans Assisted by Representatives

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107211. For more information, contact Elizabeth H. Curda at (202) 512-7215 or EWISInquiry@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107211, a report to congressional requesters

More Thorough Planning Needed to Help Better Protect Veterans Assisted by Representatives

Why GAO Did This Study

Representatives accredited by VA’s ADF program serve an important role in helping veterans or their families apply for VA benefits. Accredited representatives must be of good character and meet other requirements established in federal law and regulations. GAO was asked to review VA’s ADF program.

This report examines (1) VA policies for ensuring representatives are knowledgeable and have good character, (2) how the ADF program addresses complaints against representatives and unaccredited individuals, and (3) the extent to which VA has addressed ADF program challenges.

GAO reviewed ADF policies for reviewing applications and addressing complaints. GAO also reviewed nongeneralizable samples of applications and complaints from fiscal year 2023. Further, GAO identified challenges that ADF faces by reviewing VA documents and interviewing VA officials and selected stakeholders familiar with the ADF program, such as veteran service organizations. GAO assessed the ADF program’s plans to address challenges against GAO-identified sound planning practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations to VA to develop and use plans for ADF program initiatives that identify necessary activities and timelines, resources needed, risks, and a process to monitor progress.

VA did not provide comments.

What GAO Found

The Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) Accreditation, Discipline, and Fees (ADF) program accredits representatives who help veterans file claims for VA benefits. A key responsibility for ADF staff is reviewing accreditation applications. The ADF program has policies that help staff carry out program responsibilities, such as ensuring representatives are knowledgeable and have good character. For example, it has policies on when to obtain more information if an applicant has a criminal history and how to consider this information when making approval decisions. GAO reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 35 applications approved in fiscal year 2023 and found that staff generally followed VA’s policies.

ADF staff also address complaints; however, staff responses depend on whether the subject of the complaint is accredited. Accredited representatives are subject to VA oversight, and ADF staff follow procedures to determine if a program violation occurred and what actions, if any, should be taken. In contrast, ADF officials told GAO they have limited options regarding complaints about unaccredited individuals because VA lacks enforcement authority over them. (Legislation had been proposed to impose criminal penalties in certain circumstances.) ADF officials said they investigate complaints received, issue a “cease-and-desist” letter if warranted, and can refer the complaint to state or federal law enforcement if the unaccredited individual may have committed crimes. In GAO’s nongeneralizable sample of 10 complaints against accredited and unaccredited individuals, ADF staff generally followed program procedures.

VA is addressing ADF program challenges, but its efforts do not fully apply sound planning practices that could help ensure success. Initiatives and other actions to address key challenges that VA and outside stakeholders have identified include:

· Training requirements. VA has issued a proposed rule that would increase the frequency of required training hours to ensure representatives are better qualified to provide representation.

· Deterrence of unaccredited individuals. VA is educating veterans about the safeguards tied to using accredited representatives.

· Insufficient IT System Capabilities: VA is developing a new IT system to allow staff to track program performance and automate routine tasks.

· Lacking sufficient workforce resources. VA developed a strategic plan and is analyzing workforce needs to help ADF staff carry out program responsibilities in a timely manner.

However, VA has not fully developed plans that detail how it will implement and monitor these program initiatives, contrary to sound planning practices identified in prior GAO work. Specifically, ADF plans do not fully identify specific activities, timelines, or resources needed to complete each of the initiatives. Officials also have not assessed the risks that could affect their plans, or established how they will monitor and report performance. Fully applying these practices will help ensure the success of ADF program initiatives and ensure veterans receive responsible and qualified representation on their VA benefit claims.

Abbreviations

|

ADF |

Accreditation, Discipline, and Fees program |

|

CLE |

Continuing Legal Education |

|

IT |

Information technology |

|

OGC |

Office of General Counsel |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

PACT Act |

Honoring our PACT Act of 2022 |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

|

VSO |

Veteran Service Organization |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 28, 2025

Congressional Requesters

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) processed approximately 2 million claims for disability benefits in fiscal year 2023. The number of claims VA processed has increased significantly in recent years as potential eligibility for benefits has expanded through laws such as the Honoring our PACT Act of 2022 (PACT Act).[1] To help claimants navigate what can be a complex and lengthy process, VA accredits individuals—called representatives—to help ensure veterans have responsible and qualified assistance with preparing and presenting their claims.[2] Accredited representatives can be employees or members of veterans service organizations (VSO), attorneys, or claims agents (such as financial planners or advocates), among other individuals.

Within VA’s Office of General Counsel (OGC), the Accreditation, Discipline, and Fees (ADF) program helps ensure that accredited representatives meet requirements set in federal law and VA regulations, such as having good character and taking relevant training about veteran claims. Among other responsibilities, ADF staff review applications for accreditation and make approval decisions, monitor compliance with ongoing program requirements (such as continuing legal education requirements), and investigate complaints that could lead to suspending or cancelling accreditation. In recent years, Congress, VSOs, and others have raised questions regarding the extent to which unaccredited individuals operating outside VA’s system may be taking advantage of veterans by charging them excessive fees for filing claims.

You asked us to review the ADF program and its ability to carry out its responsibilities. This report examines (1) policies VA has established to ensure that new and existing representatives are knowledgeable and have good character; (2) how the ADF program addresses complaints about accredited representatives and unaccredited individuals; and (3) the extent to which VA has addressed VA- and stakeholder-identified challenges in carrying out ADF program responsibilities.

For our first objective, to understand how VA determines that accredited representatives are knowledgeable and have good character, we reviewed ADF program policies and written procedures and interviewed ADF program officials. We also reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of accreditation applications from fiscal year 2023 to understand VA’s processes and how they are carried out in granting accreditation to representatives. Our review focused on claims agent applications because those represent the highest risk for VA. For example, the agency vets claims agents without assistance from other entities, whereas employees of VSOs and attorneys are vetted by VSOs and state bars respectively.[3] We reviewed all 35 claims agent applications that VA told us were approved in fiscal year 2023.[4] We assessed VA documentation in these application files against VA’s written procedures to determine the extent to which ADF staff reviewed applications in accordance with VA policies. One GAO analyst reviewed the applications, and another analyst verified the assessment made by the first. The staff resolved any differences in their assessments.

For our second objective on how VA investigates and resolves complaints, we reviewed relevant federal regulations and written procedures and interviewed ADF program officials. We also reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 10 complaints that VA told us were closed in fiscal year 2023: four complaints against accredited representatives and six made against unaccredited individuals. We assessed documentation describing how VA handled these complaints against its written policies and procedures. One GAO analyst reviewed the applications, and another analyst verified the assessment made by the first.

For our third objective on program challenges, we interviewed VA officials and selected stakeholders to identify challenges that the ADF program faces in carrying out its responsibilities. Selected stakeholders included VSOs, industry groups that advocate for accredited representatives, and organizations that provide training to accredited representatives. We selected stakeholders to ensure a variety of organizations that represent the interests of different types of representatives, congressionally-chartered VSOs, and individuals knowledgeable in veterans law.[5] To assess how VA is addressing VA- and stakeholder-identified program challenges, we reviewed VA plans for program improvement and interviewed ADF officials. We assessed VA’s plans against sound practices for planning that have been identified in previous GAO work.[6]

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Accreditation helps ensure that claimants have access to qualified representation if they desire. Generally, only individuals accredited by VA represent claimants in the VA claims process.[7] Table 1 describes the three types of individuals that VA recognizes as accredited representatives.

|

Category |

Who is eligible to be accredited |

|

Veterans Service Organization (VSO) representatives |

Generally employees or members of recognized VSOs.a Recognized VSOs service the needs of veterans, such as providing information on benefits and assistance in applying for them. |

|

Attorneys |

Attorneys in good standing with a state bar. Any attorney may apply regardless of the area of law in which they specialize. |

|

Claims agents |

Any individual who is neither a VSO representative nor an attorney. There is no occupational requirement, but examples include veterans’ advocates and paralegals. |

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) regulations and VA. | GAO‑25‑107211

Note: VA allows for a one-time exemption so that claimants can designate non-accredited individuals as their representative, without compensation.

aVA regulations establish a process by which VSOs may be officially recognized. Only recognized VSOs may seek accreditation for individuals as a representative of the organization. Also, VSOs may seek accreditation for individuals who are representatives of other recognized organizations.

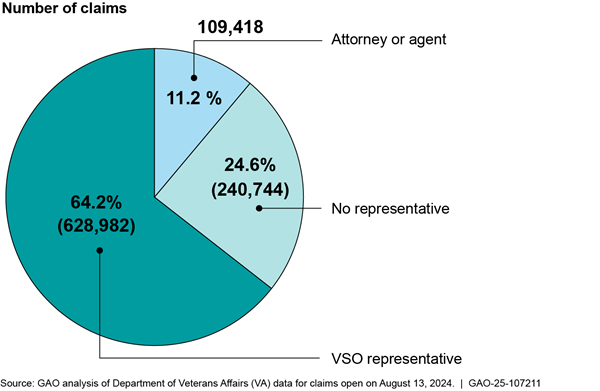

A large majority of claimants applying for disability compensation benefits use accredited representatives. Of the approximately 1 million claims open in August 2024, three-fourths of the claimants used the services of an accredited representative, with VSOs accounting for the bulk of such claims (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Number and Percentage of Open Disability Claims by Type of Accredited Representative, as of August 2024

Federal law and VA regulations set requirements that accredited representatives must meet.[8] For example, representatives must:

· Have good character. Although what constitutes good character is not specifically defined in VA regulations, they provide, with respect to claims agents and attorneys, that evidence showing a lack of good character and reputation includes such things as: conviction of a felony or other crimes related to fraud, theft, or deceit or suspension or disbarment from a court, bar, or government agency on ethical grounds.

· Provide competent representation. Accredited representatives must provide competent representation, which includes the knowledge, skills, thoroughness, and preparation necessary for representation, as well as an understanding of the issues of fact and law relevant to the claim.

· Provide prompt representation. Accredited representatives must act with reasonable diligence and promptness in representing claimants. This requirement includes responding promptly to VA requests for information or assisting a claimant in responding promptly to VA requests for information.

The ADF program—within VA’s OGC—accredits and oversees many accredited representatives. As of November 2024, 13,670 individuals were accredited to represent claimants: 8,141 VSO representatives, 5,008 attorneys, and 521 claims agents. Specifically, ADF staff:

· Review applications and make approval decisions. ADF received 2,978 applications in fiscal year 2023 and 3,765 in fiscal year 2024.

· Monitor whether accredited representatives meet ongoing program and training requirements.

· Investigate issues and complaints that could lead to a representative having his or her accreditation suspended. ADF received 54 complaints in fiscal year 2023 and 88 in fiscal year 2024.

· Review requests for new VSOs to be recognized by VA and oversee the training VSOs provide to their accredited employees or members. In fiscal years 2023 and 2024, ADF received 3 applications from VSOs seeking recognition.

The initial and ongoing requirements for accredited representatives vary by type (see table 2).

Table 2: Selected Initial and Ongoing Accreditation Requirements by Type of Accredited Representative

|

|

Good character requirements |

Training requirements |

||

|

|

Initial |

Ongoing |

Initial |

Ongoing |

|

Veterans Service Organization (VSO) representatives |

VSOs recommending a prospective representative to VA must certify the individual is of good character. |

Representatives’ good character must be recertified by their VSO every 5 years. |

VSOs recommending a prospective representative must certify that the individual has demonstrated an ability to represent claimants before VA. |

VSOs must recertify representatives’ ability to represent claimants before VA every 5 years. |

|

Attorney |

Attorneys are presumed to meet character requirements based on state bar membership in good standing unless the Office of General Counsel receives credible information to the contrary. They must also provide character references and background information, including information concerning criminal background, as part of the accreditation application. They must submit to VA information about any court, bar, or federal or state agency to which they are admitted to practice or authorized to appear, along with a certification that they are in good standing. |

Attorneys must annually submit to VA information about any court, bar, or federal or state agency to which they are admitted to practice or authorized to appear, along with a certification that they are in good standing. |

As a condition of initial accreditation, attorneys are required to complete 3 hours of qualifying continuing legal education (CLE) within 12 months. |

Attorneys must complete an additional 3 hours of qualifying CLE within 3 years of initial accreditation and every 2 years thereafter. |

|

Claims agent |

VA must make an affirmative determination of character before a prospective agent can be accredited. Claims agents must submit to VA information about any court, bar, or federal or state agency to which they are admitted to practice or authorized to appear, along with a certification that they are in good standing. Also, they must provide character references and provide background information including information concerning criminal background, as part of the accreditation application. |

Same as ongoing attorney requirements above. |

Same as initial attorney requirements above. In addition, claims agents must pass a written examination by VA. |

Same as ongoing attorney requirements above. |

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) regulations. | GAO‑25‑107211

The ADF program also plays a role in ensuring claimants are not charged improper fees when filing for benefits. Federal law and regulations govern the fees that each type of accredited representative can charge claimants. VSO representatives are required to provide their services free of charge. Attorneys and claims agents are generally prohibited from charging individuals for the initial preparation and filing of a claim, but are allowed to charge fees after an initial decision is made on the claim by VA. VA generally allows accredited agents and attorneys to charge the veteran a fee; fees 20 percent or below of the veteran’s past-due benefits awarded are presumed to be reasonable. According to VA, a claimant can challenge the fee with the ADF program if the claimant believes that the fee charged by the attorney or claims agent is too high or unreasonable.

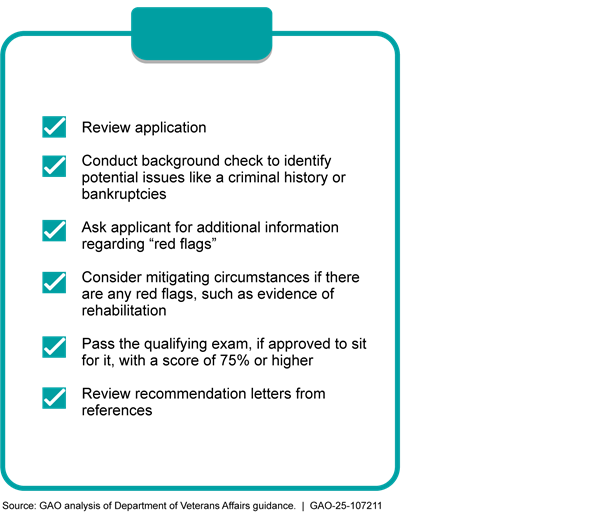

VA Has Policies for Approving New Accreditation Applications and Ensuring Training Compliance

The ADF program has policies and tools for staff to follow and use when reviewing applications for accreditation. VA’s policies and tools are detailed and help ensure that staff consistently capture information and make decisions when reviewing applications. For example:

· ADF staff use checklists to ensure they have collected required information and completed all required steps when reviewing applications.

· ADF staff use a software package allowing them to electronically store documents that support applications, track the status of an application in the review process, and record notes summarizing the results of their review, among other things.

· ADF staff use letter templates to help facilitate follow-up with applicants when additional information is needed to make an accreditation decision. For example, one template is used when the investigation identifies a possible criminal history, and another when the applicant is employed in a field in which a conflict of interest could arise if accredited, such as financial planning.[9]

· ADF staff use guidance to assess any negative findings from their application reviews. For instance, ADF policies state that previous serious misconduct is not automatically disqualifying if the applicant can provide evidence of rehabilitation. Staff are also directed to consider the recency of the misconduct and subsequent positive social contributions when deciding whether the applicant has established their good character and reputation.

Our review of all 35 claims agent applications approved in fiscal year 2023 found that staff generally followed ADF procedures when reviewing and making decisions to recommend accreditation. Specifically, we found that ADF staff generally collected all information required by VA policy, conducted additional inquiries when needed, and documented their rationale for making a recommendation to accredit the applicant (see fig. 2).[10]

Figure 2: Department of Veterans Affairs’ Process for Reviewing Applications to Become Accredited Claims Agents to Help Veterans with Claims

ADF has a written policy and procedures regarding how staff should determine whether accredited representatives are up to date on their training requirements.[11] ADF staff told us that they periodically run reports to verify that accredited representatives have completed required training. Those not meeting the requirements may have their accreditation suspended. ADF officials told us that in fiscal year 2024, they suspended the accreditation of about 1,500 attorneys and agents who did not complete their training requirements.

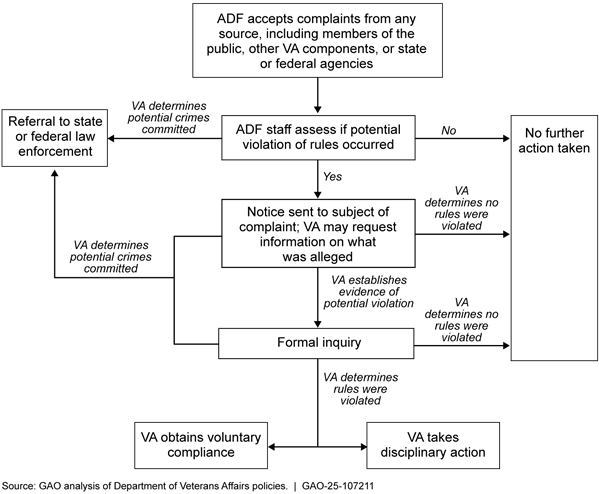

VA Investigates and Resolves Complaints Against Accredited Representatives and Takes Some Actions with Unaccredited Individuals

The ADF program addresses complaints, but the types of steps the program takes depend on whether the complaints are made against accredited representatives or unaccredited individuals. For accredited representatives, these steps include determining whether credible, written evidence exists that the representative violated any number of standards of conduct and whether it merits suspending or terminating accreditation (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) Process for Addressing Complaints Against Accredited Veterans Representatives in the Accreditation, Discipline, and Fees (ADF) Program

In contrast, ADF officials told us the program is more limited in the actions it can take with complaints against unaccredited individuals. Federal law does not provide for monetary penalties against unaccredited individuals who improperly assisted claimants when filing for benefits, and thus ADF officials told us there is little they can do regarding such individuals. However, ADF officials stated they will conduct an informal investigation to determine if the complaint has merit. If they find sufficient evidence of a possible regulatory violation, ADF staff may send a cease-and-desist letter to the subject of the complaint. The letter gives the subject of the complaint the opportunity to respond to the possible violation.

Additionally, staff told us they may refer the case to another state or federal agency if they believe there is evidence that another crime was committed (e.g., a violation of consumer protection laws). According to VA officials, they sent cease-and-desist letters to 35 of the 41 unaccredited individuals who were the subject of complaints filed in fiscal year 2024. VA also referred nine of these 35 cases to state or federal enforcement agencies.

In our review of 10 complaints (four against accredited representatives and six against unaccredited individuals) closed in fiscal year 2023, we found that ADF staff followed program procedures and guidance. For example, we found that staff obtained additional information on complaints when appropriate and documented the agency’s rationale for the actions taken. Table 3 summarizes the 10 complaint cases we reviewed.

Table 3: Summary of Selected Complaints Investigated by Accreditation, Discipline, and Fees (ADF) Program Staff in Fiscal Year 2023

|

Case |

Subject of complaint |

Summary |

|

1 |

Accredited Veterans Service Organization (VSO) representative |

Individual filing complaint alleged that the representative lacked the good character needed to be an accredited representative, but abandoned the complaint and did not sign the required release form so that ADF staff could contact the VSO representative in question. |

|

2 |

Accredited attorney |

Complaint came from a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) employee concerned that claimants were being charged unreasonable fees. ADF staff found that the fees charged by the attorney were allowable and declined to take further action. |

|

3 |

Accredited claims agent |

A claimant alleged they were charged unreasonable fees by an agent for filing an appeal to a disability claims decision. ADF staff provided the individual with information on how to challenge the reasonableness of the fees, which is a separate process from ADF’s complaint process. |

|

4 |

Accredited VSO representative |

A VSO representative alleged that another VSO representative was improperly accessing veterans’ records and referring them to a claims agent who would charge veterans for filing initial claims. ADF sent the individual a letter of inquiry. The VSO representative had accreditation removed voluntarily, and ADF officials determined they could not take additional action in this case. ADF also further investigated the claims agent named in the complaint. |

|

5 |

Unaccredited individual |

A veteran’s family member alleged that an accredited agent mismanaged the finances of the now deceased veteran. ADF determined that the claims agent who was the subject of the complaint was no longer accredited and suggested the family member file a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission or state attorney general. |

|

6 |

Unaccredited individual |

A VA employee referred a complaint that an unaccredited individual was assisting veterans with filing claims. After an initial investigation, ADF determined the subject of the complaint was not assisting veterans with filing claims and no further action was necessary. |

|

7 |

Unaccredited individual |

A VA regional office submitted a complaint that an unaccredited individual was helping veterans file initial claims. ADF sent a letter to inform the individual of the law governing accreditation. The individual responded that their business was not helping veterans prepare claims and agreed to clarify this on its website, which satisfied ADF. |

|

8 |

Unaccredited individual |

A state agency referred this case to ADF over concerns that a former VSO representative who was no longer accredited had helped veterans file claims. ADF determined that the individual was not currently assisting veterans, but sent a letter to inform the individual of the law governing accreditation. |

|

9 |

Unaccredited individual |

A business owner was the subject of numerous complaints referred to ADF, including by VA staff processing claims. The business’s website stated that it helped hundreds of veterans apply for benefits. ADF staff sent a cease-and-desist letter and met with individuals from the state’s attorney general’s office to offer assistance investigating the business. |

|

10 |

Unaccredited individual |

ADF received numerous complaints that an unaccredited individual was charging excessive fees and illegally obtaining veterans’ usernames and passwords to file claims for them. The individual previously applied for accreditation, but was denied. ADF sent a cease-and-desist letter after reviewing Facebook posts and media articles that indicated the individual’s business was assisting veterans with claims. The individual did not respond to ADF’s letter, and ADF referred the case to the state attorney general. |

Source: GAO analysis of a sample of complaint investigations by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ ADF program in fiscal year 2023. | GAO‑25‑107211

The number of unaccredited individuals illegally assisting veterans likely exceeds the number of complaints the ADF program receives according to VA officials. They told us that veterans may not know that they should not be charged for assistance filing initial claims and that veterans could be reluctant or embarrassed to report that they were taken advantage of. Officials added that it is difficult to know when unaccredited individuals are involved because they are not disclosed on the claim, and it may appear that veterans are filing claims on their own.[12]

VA Is Addressing Key Challenges with the ADF Program but Has Not Fully Developed Implementation Plans

VA Is Addressing Challenges with Training Requirements, Unaccredited Individuals, Information Technology, and Workloads

VA officials and selected stakeholders commonly cited four challenges with carrying out ADF program responsibilities; and we found that VA has undertaken a number of initiatives to address these challenges. Specifically, VA officials and selected stakeholders identified challenges related to (1) training requirements for accredited representatives; (2) deterrence of unaccredited individuals; (3) insufficient IT system capabilities; and (4) insufficient workforce resources.

Training Requirements for Accredited Representatives

VA officials and selected stakeholders we interviewed said current training requirements make it challenging to ensure that accredited attorneys and claims agents have the knowledge they need to assist veterans with benefits claims. Specifically, stakeholders told us the amount of minimum required training is too low, and they expressed concerns over timing for training.[13] For example, five of the eight stakeholders we interviewed told us current training levels required to maintain accreditation—which are 3 hours of training every 2 years—may be too low given the complexity of veterans law and recent changes such as those from the PACT Act. Two of the eight stakeholders expressed concern about having up to a year to complete training after attorneys or claims agents are accredited. One of these stakeholders noted that an accredited attorney or claims agent could provide incorrect assistance for an entire year before learning the correct information.

VA has taken steps to address this challenge. Specifically, on October 11, 2024, VA published a proposed rule in the Federal Register that included proposed changes to the training requirements.[14] The proposed rule would require agents and attorneys to complete 3 hours of qualifying training in the 6 months before they are accredited rather than within the year after accreditation. Moreover, it would require accredited claims agents and attorneys to complete 3 hours of qualifying training every year rather than every 2 years. According to VA, the intended effect of these changes is to strengthen the current training requirements to ensure that attorneys and agents representing claimants and appellants for VA benefits are better qualified to provide such representation.

Deterrence of Unaccredited Individuals

Selected stakeholders described some of the issues veterans may encounter with unaccredited individuals. For example, three of the stakeholders told us unaccredited individuals might have charged veterans a portion of their ongoing disability payments in exchange for helping the veteran file a claim, which is not permitted. Two stakeholders told us unaccredited individuals might also charge veterans regardless of the amount of assistance provided, and veterans do not have recourse with VA to challenge those charges. One stakeholder said unaccredited individuals might insist that veterans pursue the easiest claims first so that the unaccredited individual can receive payment faster. However, if veterans delay filing the more challenging claims, they may receive retroactive payments covering fewer months if those claims are later granted. This is because the date the initial claim is filed at VA generally affects the retroactive payments received. For example, if a veteran files a claim for one condition on March 1, 2024, and waits to file another claim a year later on March 1, 2025 for a different condition, the effective dates would be 12 months apart. Assuming VA grants benefits for both conditions, the veteran would receive a retroactive benefit covering fewer months for one of the conditions by waiting until March 1, 2025, to apply for benefits than if they had applied for both conditions on March 1, 2024.

According to ADF officials and five of the eight selected stakeholders we interviewed, VA has limited ability to deter unaccredited individuals from charging veterans for assistance with filing claims, which is not permitted. As discussed earlier, ADF can send a cease-and-desist letter to the individual informing them that they may be violating federal law and give the individual the opportunity to respond to the violation. However, ADF staff and stakeholders said VA does not have authority to take further action following a cease-and-desist letter, which two stakeholders told us makes such a letter ineffective.[15] ADF can refer cases to law enforcement authorities. However, they do not track these actions after the referral—unless the enforcement entity contacts the ADF program—since the cases are no longer under their control, according to VA officials.

While VA officials told us they lack enforcement authority with respect to unaccredited individuals, they said they are taking other steps to protect veterans from potential harm from unaccredited individuals. For example, VA provides outreach through its Veterans, Servicemembers, and Families Fraud Evasion program to encourage the use of accredited representatives, describe safeguards tied to using these representatives, and warn about the use of unaccredited individual.[16] In August 2024, VA officials told us the agency released an outreach toolkit—developed with the assistance of ADF officials—that focuses specifically on unaccredited individuals. This toolkit included information on potentially harmful practices such as charging high fees or placing pressure on veterans to sign a contract agreeing to pay for assistance with an initial claim.

According to VA officials, they have shared this toolkit with over 700 VSOs and many other federal agencies such as the Department of Defense and the Department of Justice. VA has also provided information about the issues veterans may encounter with unaccredited individuals through electronic media, such as social media and its email newsletter, that is sent to 16 million veterans, according to VA officials. VA also briefed congressional offices and staff at VA regional offices. Additionally, VA has included a legislative proposal in its 2025 budget submission to reinstate a criminal penalty to deter unaccredited individuals.[17]

Insufficient IT System Capabilities

According to ADF officials, the ADF program’s current IT system limits their ability to monitor program performance. For example, ADF officials told us the IT system does not automatically generate some reports that would be helpful in administering the program, such as how long it takes ADF staff to process accreditation applications or automatically identify accredited representatives who have not completed required training. Instead, ADF officials said they must generate reports on an ad-hoc basis, which is time consuming. The officials also said the system cannot run other queries that could help identify issues in processing applications. For instance, the system cannot produce data on applicants who were denied accreditation or who abandoned their applications. It also cannot differentiate between VSO representative, attorney, and claims agent applications until the individual is accredited.

Additionally, the IT system does not support many routine program tasks, increasing workloads for staff who must enter information manually, according to ADF officials. Specifically, staff must manually save all documents that the office receives, such as applications, responses to background investigations, or certifications that accredited representatives completed training. Staff also must manually update information on accredited representatives, such as when they move. Several stakeholders we interviewed told us that information posted on VA’s website, such as an accredited representative’s location, can be inaccurate. Additionally, staff must manually enter and update deadlines for when each accredited representative must complete and report on their required training.

VA has taken steps to address this challenge by planning for or developing new IT capabilities for the ADF program, according to ADF officials. Specifically, they have been working with VA’s Office of Information Technology (OIT) and providing input on IT capabilities that they need to improve program management. One planned upgrade is an online portal that will allow applicants and existing accredited representatives to enter information and upload documents directly into the IT system. Officials said this should eliminate the need to manually enter information, which would save staff a significant amount of time. VA is also planning to develop new tools to help monitor program performance, such as more robust data tracking and analysis. ADF officials could not estimate when IT upgrades will be completed; however, as of November 2024, contractors had started work on upgrades to program monitoring and officials said they thought contractors had started work on the online portal as well.

Lacking Sufficient Workforce Resources

ADF officials and four of the eight selected stakeholders said the ADF program has insufficient workforce resources and, consequently, ADF officials said they have struggled to allocate these resources. This challenge, coupled with an out-of-date IT system, has led to delays or the inability to effectively carry out certain program responsibilities, according to ADF officials. For example:

· Agent applications. ADF officials estimated that they had a backlog of almost 2,200 claims agent applications in November 2024 and that they currently receive an additional 50 to 100 of these applications per month. According to ADF officials, agent applications are the most time-intensive to process because ADF staff conduct a background check on applicants. ADF staff have advised applicants that it can take a year for their application to be processed. Officials added that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated delays because VA was not able to administer in-person written exams to applicants.[18]

· VSO training reviews. ADF has not consistently reviewed the training that VSOs provide to their employees.[19] Over the past 5 years, ADF staff have conducted reviews in 2021 and 2024. Additionally for fiscal year 2024, officials planned to request and review training of nine VSOs, but completed two reviews within that time frame.

· Fee reasonableness reviews. One stakeholder told us the ADF program struggles to decide fee disputes in a timely manner.[20] Consequently, the stakeholder thought accredited agents and attorneys know they may need to wait several years for a dispute to be resolved and a payment issued.

ADF officials told us they have concentrated on specific program responsibilities in line with shifting agency priorities and that focusing on one area, such as reducing the backlog of applications, draws resources away from other areas.

VA has taken steps to address its workload challenges by undertaking several initiatives. For example:

· Adding staff. As of November 2024, the ADF program had added seven paralegals (for a total of 12) and one attorney (for a total of six), which officials said represent the program’s highest ever staffing levels. In addition, ADF officials have worked to lighten the workload of the program’s attorneys by assigning certain routine tasks and functions to paralegals. Some of the new paralegal tasks include drafting fee reasonableness motions, drafting fee reasonableness settlement and waiver letters, completing the first review of claims agent applications, and researching complaints and developing either the first draft of an informal inquiry for an accredited representative or a cease-and-desist letter for an unaccredited individual. As stated earlier, VA also anticipates that planned IT upgrades will free staff from some administrative tasks.

· Assessing workforce needs. VA’s Office of General Counsel, which administers the ADF program, entered into an interagency agreement with the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to conduct a workforce analysis of the Office of General Counsel and its components, including the ADF program, and assess process improvements. That analysis should be completed in fiscal year 2025. Among other things, OPM will assess current workloads and develop a recommendation for the number of staff needed to carry them out.

· Streamlining fee reasonableness reviews. In response, in part, to an increase in the number of fee reasonableness requests received by VA over the past several years, VA finalized a rule to establish default fee allocations if more than one claims agent or attorney represented the veteran in the case.[21] According to VA, this should allow accredited agents, attorneys, and claimants to receive their earned fees and benefits faster. VA officials said this will also allow the Office of General Counsel to focus on fee disputes with unique circumstances.

· Developing a strategic plan. ADF officials developed the program’s first comprehensive strategic plan for fiscal year 2024, which they said is an attempt to look at the program’s activities holistically. The plan outlines the program’s initiatives, identifies the officials responsible for each, and sets goals and metrics for each initiative. For instance, the plan has goals for how quickly staff will review accreditation applications and for how many fee reasonableness reviews to resolve. A number of these initiatives would address the VA- and stakeholder-identified challenges. For example, initiatives include working with stakeholders to develop outreach to veterans regarding possible issues with employing unaccredited individuals, working with VA IT specialists on developing the new IT system, and assigning more staff to fee reasonableness reviews to address that resource limitation.

More Thorough Planning Could Help the Program Identify Resource Needs, Implement Initiatives, and Monitor Progress

Although the ADF program has developed a high-level strategic plan to address program challenges, it has not fully applied sound planning practices to implement the initiatives identified in the plan (see table 4).[22] Specifically, ADF’s plan identifies the problem addressed by the program and goals and coordination with internal and external stakeholders, as recommended by sound planning practices identified in previous GAO work.[23] However, ADF’s plan does not fully address four remaining practices that include identifying: (1) activities and timelines needed to achieve the initiatives’ goals, (2) resources needed, (3) risks that could affect initiative and goal completion, and (4) a process for monitoring and reporting on performance toward achieving program goals.

Table 4: Assessment of the ADF Program’s Plan to Address Challenges Using Components of Sound Planning Practices

|

Component |

Component description |

GAO’s assessment |

|

Problem and goals |

Identify the problem addressed by the program, as well as the program goals and objectives. |

⬤ |

|

Activities and timelines |

Identify the specific activities that must be performed to implement the program. The agency should develop a schedule that defines, among other things, when work activities will occur, how long they will take, how they are related to one another, and interim milestones and checkpoints to gauge the completion of program initiatives. |

◑ |

|

Resources |

Address the types of resources that will be needed, such as human capital or information technology, to complete the program goals. |

◑ |

|

Coordination |

Identify stakeholders and, as appropriate, ensure that they are included in developing and executing the program initiatives. Management also should ensure adequate means for communicating with, and obtaining information from, external stakeholders who may have a significant impact on the agency achieving its goals. |

⬤ |

|

Risk |

Estimate the significance of risks from both external and internal sources, assess the likelihood of its occurrence, and decide how to manage the risk. |

⭘ |

|

Performance monitoring and evaluation |

Describe how goals will be achieved, establish outcomes for each program initiative, and identify a process to monitor and report on progress. |

◑ |

Legend: ⬤ Generally applied - ADF applied a component without significant gaps in its coverage of the actions associated with this sound practice.

◑ Partially applied – ADF applied at least one but not all aspects of the component.

⭘ Not applied – ADF applied no aspects of the component.

Source: GAO analysis of Accreditation, Discipline and Fees (ADF) program strategic plan as compared to sound planning practices found in GAO‑12‑846. | GAO‑25‑107211

Problem and goals - generally applied. The plan identifies the program responsibilities, goals, and individual initiatives that will be pursued to achieve those goals. For example, the plan includes a strategic goal for program oversight and monitoring. Within this goal, the plan includes multiple oversight initiatives such as reviews of accredited representatives’ training requirements and initiatives for handling complaints against accredited representatives and unaccredited individuals.

Activities and timelines - partially applied. The ADF program developed standard operating procedures that include activities needed to complete several of the planned initiatives. For other initiatives, ADF’s plan includes a high-level description of the activities needed to complete the initiatives. However, several initiatives lacked planned actions. For example, the plan includes an initiative to coordinate with external stakeholders on outreach to veterans and enforcement actions related to unaccredited individuals, but the initiative does not include any activities describing how ADF would accomplish this goal.

Further, the plan does not include complete timelines, such as start dates or interim milestones. These could be used to track progress on the plan’s implementation such as timeframes for contacting external stakeholders and developing outreach activities. Defining all work activities for each initiative, when this work will occur, how long it will take, and milestones to gauge progress will help provide a realistic representation of the time and resources needed for these initiatives and the means by which to gauge progress, identify and address potential problems, and promote accountability.

Resources - partially applied. While the ADF plan identified staff responsible for overseeing the initiatives and VA resources to develop the program’s new IT system, we found it had not identified the full scope of resources needed or whether resources would be available when needed to complete each of the initiatives. As discussed earlier, ADF officials told us the program has limited resources and has needed to reallocate staff to address shifting priorities. However, the plans do not describe how ADF program leadership should dedicate resources to achieve its objectives, or how to allocate resources among the various initiatives.

Further, the ADF program has an incomplete picture of resource needs because, as noted above, it has not outlined specific activities and complete timelines to implement the initiatives. A plan, including activities and timelines for accomplishing the initiatives and the types of resources that will be needed, will help the ADF program make further progress addressing its challenges with carrying out its responsibilities.

Coordination - generally applied. The plan includes initiatives for communicating and obtaining information from internal and external stakeholders. Specifically, the plan includes two initiatives to collaborate with internal and external stakeholders on veteran outreach. In addition, one of the initiatives includes collaboration with external stakeholders on enforcement.

Risk - not applied. ADF’s plan does not include an assessment of risks that could affect the implementation and completion of the initiatives that are intended to help ADF achieve its program goals.[24] Such an assessment could, for example, examine risks associated with the program’s workload challenges and its decisions about deploying resources. The assessment could also include the risk of not addressing the application backlog versus not addressing the VSO training audits, for example, and their impacts on program goals. By assessing risks to understand them and their potential adverse effects—and developing applicable mitigation strategies—ADF program officials will be better positioned to set appropriate plans and priorities to implement program objectives.

Performance monitoring and evaluation - partially applied. As stated earlier, the plan includes individual initiatives ADF staff identified to help the program achieve the strategic goals. These goals include metrics, as needed, to identify whether the initiatives have been achieved that year. For example, the plan includes an initiative to conduct a review of the training requirements for accredited agents and attorneys during that plan year. However, the plan does not include details on how ADF officials will monitor or evaluate the progress of each initiative and report on that progress. Including such details will help better ensure the initiatives’ progress throughout the year.[25]

ADF program officials agreed that, for example, developing timelines and interim milestones for program initiatives could help staff monitor progress or to make a record of why certain milestones were not being met. According to ADF program officials, they have not fully applied sound planning practices because (1) they have competing resource demands and have been focused on working through their backlogs; (2) they are still developing their program processes to determine the best direction for some of the program tasks; and (3) their efforts are subject to factors outside their control, such as resource allocations or delays because of competing VA priorities. For instance, ADF officials told us that several of its initiatives are dependent on system upgrades that will be performed by VA’s OIT. However, OIT has its own plans and priorities that ADF cannot control.

However, fully applying these practices could help officials proactively develop a realistic picture of the time and resources needed for implementing and accomplishing the program’s initiatives—some of which might be months or years away from full implementation. Doing so would also help ensure accountability throughout implementation, mitigate risks, and enable better decision-making, including about resource needs and allocations. Moreover, by developing and using detailed plans for systematically implementing ADF program initiatives, VA will be better positioned to carry out its mission of ensuring that veterans receive responsible and qualified representation on their VA benefit claims.

Conclusions

Hundreds of thousands of veterans rely on accredited representatives to guide them through the process of applying for VA benefits. The ADF program plays a key role in ensuring that these representatives are qualified and charge appropriate fees. The program has taken steps to develop processes and initiatives that help ensure its staff consistently carry out program responsibilities and address many of the challenges it faces. Going forward, the ADF program would benefit from fully applying sound planning practices to its initiatives. Doing so would help ensure the success of the program initiatives and better protect veterans assisted by accredited representatives.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to VA:

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should ensure that its Office of General Counsel, in consultation with the Office of Information Technology, develops detailed plans that incorporate sound planning practices for its ADF program initiatives. These plans should detail necessary activities and timelines; identify resources needed; include risk assessments and, as necessary, applicable mitigation strategies; and identify a process to monitor and report on progress. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs should ensure that its Office of General Counsel uses the detailed plans it developed, in coordination with the Office of Information Technology, to implement and monitor the ADF program initiatives. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comment

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Veterans Affairs for review and comment. In a meeting to discuss our recommendations, ADF officials told us that several of their planned program improvements are dependent on changes to IT that are being implemented by OIT. As such, ADF officials cannot control some of the planning and resources needed to successfully carry out program improvements. We agreed to amend our recommendations to reflect the need for OGC to coordinate with OIT when developing and implementing plans. We also added some clarifying language in the report.

VA did not provide comments on this report.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7215 or EWISInquiry@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Elizabeth H. Curda

Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security

List of Requesters

The Honorable Morgan McGarvey

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Disability and Memorial Affairs

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jen Kiggans

Chairwoman

The Honorable Delia Ramirez

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Committee on Veterans’ Affairs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Tracey Mann

House of Representatives

The Honorable Frank J. Mrvan

House of Representatives

The Honorable Troy E. Nehls

House of Representatives

The Honorable Chris Pappas

House of Representatives

GAO Contact

Elizabeth H. Curda, (202) 512-7215 or EWISInquiry@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgements

In addition to the contact named above, the following individuals made key contributions to this report: James Whitcomb (Assistant Director), Daniel R. Concepcion (Analyst in Charge), and David Reed. Also contributing to this report were Alex Galuten, Mimi Nguyen, Nyree Ryder Tee, Rebecca Sero, Alero Simon, Almeta Spencer, Kate van Gelder, Margaret Weber, and Malissa G. Winograd.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Pub. L. No. 117-168, 136 Stat. 1759. Among other things, the PACT Act expanded presumptive conditions associated with exposure to burn pits and other toxins. This resulted in greater potential eligibility for certain health care and benefits. See also the Blue Water Navy Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019, which extended the presumption of exposure to herbicides, such as Agent Orange, to veterans who served in the offshore waters of the Republic of Vietnam between January 9, 1962, and May 7, 1975. Pub. L. No. 116-23, 133 Stat. 966.

[2]In this report we collectively refer to accredited veterans service organization employees, attorneys, and claims agents as “accredited representatives” unless otherwise specified. VA allows a one-time exemption so that claimants can designate non-accredited individuals as their representative, without compensation. However, these individuals are beyond the scope of our review.

[3]Veterans service organizations are responsible for determining the character of their representatives and, consequently, VA accredits individuals from these organizations without conducting any additional background research. Attorneys seeking accreditation complete the same application as claims agents. However, VA presumes that attorneys in good standing with the state bar meet character requirements unless the Office of General Counsel receives credible information to the contrary.

[4]Our sample was not generalizable because we did not, for instance, assess how VA reviewed attorney applications or applications that were denied. We did not review applications that were denied because ADF officials could not reliably identify these cases in their IT systems, and they said these cases could be subject to appeal. This report discusses some limitations of the ADF program’s IT system.

[5]Specifically, we interviewed officials from the Academy of VA Pension Planners, the American Legion, Disabled American Veterans, National Association of Veterans Advocates, the National Veterans Legal Services Program, Veterans of Foreign Wars, a past-president of the National Law School Veterans Clinic Consortium, and a law professor who specializes in veterans law.

[6]See, for example, GAO, VA Disability Compensation: Actions Needed to Address Hurdles Facing Program Modernization, GAO‑12‑846 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2012).

[7]VA allows a one-time exemption so that claimants can designate non-accredited individuals as their representative without compensation. For example, this exemption could be used by claimants who wish to designate a family member as their representative.

[8]See, for example, 38 U.S.C. §§ 5901-5905 and 38 C.F.R. §§ 14.626-14.637.

[9]Our prior work has shown that some accredited individuals were selling financial products to veterans to transfer assets to qualify for VA pension benefits. Some of these cases involved vulnerable populations, such as veterans in assisted living facilities, or involved individuals selling products that resulted in veterans losing control of their assets without qualifying for VA benefits. See GAO, Veterans’ Pension Benefits: Improvements Needed to Ensure Only Qualified Veterans and Survivors Receive Benefits, GAO‑12‑540 (Washington, D.C.: May 15, 2012); and Veterans Benefits: Actions VA Could Take to Better Protect Veterans from Financial Exploitation, GAO‑20‑109 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 3, 2019).

[10]Our assessment focused on whether ADF staff followed the program’s written procedures. We did not assess staff decisions on the applications.

[11]Attorneys and claims agents must complete 3 hours of training within 1 year of becoming accredited, an additional 3 hours within 3 years of becoming accredited, and then 3 hours every 2 years afterward.

[12]While accredited representatives are disclosed on the claim paperwork, unaccredited individuals are not, so VA has no record of such individuals.

[13]Current standards require attorneys and claims agents to complete 3 training hours within 1 year of becoming accredited, an additional 3 hours within 3 years of becoming accredited, and then 3 hours every 2 years afterwards.

[14]89 Fed. Reg. 82,546 (Oct. 11, 2024).

[15]In the 118th Congress, legislation was introduced to impose criminal penalties on individuals for soliciting, contracting for, charging, or receiving, or attempting to solicit, contract for, charge, or receive, any unauthorized fee or compensation with respect to the preparation, presentation, or prosecution of any claims for VA benefits. See, for example, the GUARD VA Benefits Act of 2023 (S. 740), the Guard VA Benefits Act (H.R. 1139), and the PLUS for Veterans Act of 2023 (S. 1789 and H.R. 1822).

[16]The Veterans, Servicemembers, and Families Fraud Evasion program is part of a White House interagency Policy Council effort. The program’s call center and website combine resources from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Department of Defense, Department of Education, Department of State, Federal Communications Commission, Federal Trade Commission, Internal Revenue Service, Office of Management and Budget, and Social Security Administration to ensure veterans and service members have cross-agency access to reporting tools and resources to combat fraud.

[17]A criminal penalty was removed in December 2006. See Pub. L. No. 109-461, § 101(g), 120 Stat. 3403, 3408.

[18]The ADF program now offers the accreditation exam only online, a change made initially in response to COVID-19.

[19]To assess a VSO’s training program, ADF requests (1) a statement of the skills, training, and other qualifications the VSO requires of current and prospective representatives handling veterans’ claims; (2) all of the organization’s materials used in training representatives; and (3) a statement of the number of hours of formal classroom instruction, subjects taught, the period of on-the-job training, and any related information.

[20]A veteran can challenge the reasonableness of a fee charged by an accredited attorney or claims agent. Officials from the VA Office of General Counsel decide whether the presumption of reasonableness applies to the fee charged and whether the fee is reasonable based on several factors including the extent and type of services the representative performed, case complexity, the amount of time the representative spent on the case, and rates charged by other representatives for similar services. In direct-payment fee matters, VA will generally pay the attorney or claims agent after the fee reasonableness decision has been made. If VA has already released the funds to the attorney or claims agent, VA will order the attorney or agent to return any excess payment to the claimant or risk having their VA accreditation removed.

[21]89 Fed. Reg. 85,055 (Oct. 25, 2024).

[22]Although there is no established set of practices for all plans, components of sound planning are important because they define what organizations seek to accomplish, identify specific activities to obtain desired results, and provide tools to help ensure accountability and mitigate risks.

[23]See GAO‑12‑846.

[24]Risk assessment is also consistent with federal standards for internal control. These standards call for agencies to both identify all relevant risks and analyze risks that may prevent them from achieving their goals. Further, this assessment should include an estimation of a risk’s significance, an examination of the likelihood of any risk’s occurrence, and a decision as to what actions should be taken to manage the risk. Risk assessment is important because it also informs an entity’s policies, planning, and priorities. See Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[25]According to ADF officials, a mid-year check-in was conducted with staff responsible for overseeing the initiatives to monitor progress. Consequently, officials prioritized a few of the initiatives such as a goal related to cease-and-desist letters in response to complaints against unaccredited individuals as well as the goal to ensure eligible accredited attorneys and agents had met their training requirements. Additionally, weekly paralegal meetings included presentations on data related to fee reasonableness reviews, accreditation applications, and the number of letters sent with the intent to suspend accreditation.