INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Patent Office Should Strengthen Its Efforts to Address Persistent Examination and Quality Challenges

Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

|

On September 30, 2025, GAO reposted this report to include comments from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in Appendix V. |

View GAO‑25‑107218. For more information, contact Candice N. Wright at wrightc@gao.gov

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107218, a report to the Chairman, Subcommittee on Intellectual Property, Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate

Patent Office Should Strengthen Its Efforts to Address Persistent Examination and Quality Challenges

Why GAO Did This Study

The U.S. patent system helps encourage innovation by allowing patent owners to generally exclude others from making or using a patented invention for up to 20 years. The USPTO employed 8,944 patent examiners at the end of fiscal year 2024 who review patent applications to determine if the inventions merit a patent. In fiscal year 2024, the USPTO received approximately 527,000 new patent applications and granted about 365,000 patents. Examiners search U.S. and foreign patents and scientific journals to determine if an application complies with statutory patentability requirements (eligible subject matter, novelty, nonobviousness, and clear disclosure). Pressure for examiners to review applications in a timely manner competes with pressure to issue quality patents that meet statutory patentability requirements.

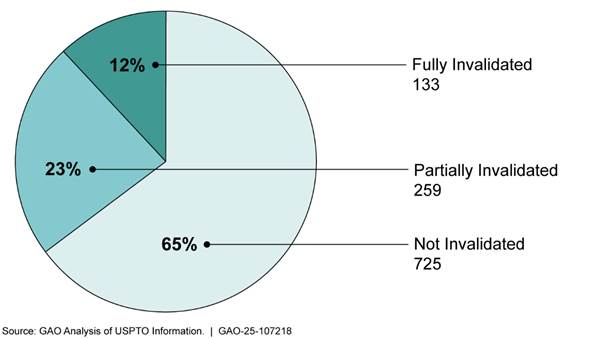

Some researchers say that patent invalidation rates in the courts suggest that patent quality may be lower than what USPTO’s quality metrics indicate. For example, according to one study, about 40 percent of litigated patents are found invalid, although these patents might not be representative of all patents. Patents that do not meet statutory patentability requirements can inhibit innovation or create costly legal disputes for patent owners and technology users.

GAO has previously reported on patent examination and quality challenges in GAO-16-490 and GAO-16-479.

GAO was asked to review issues related to patent examination and quality. This report (1) examines challenges that patent examiners face that could affect the quality of issued patents; (2) assesses initiatives the USPTO has taken to improve patent quality, including pilot programs, and the extent to which the agency has measured the effectiveness of those initiatives; (3) evaluates how the USPTO assesses patent quality and examiner performance regarding quality; and (4) assesses how the USPTO communicates patent quality externally.

To conduct this review, GAO

· interviewed agency officials and held six focus groups with nearly 50 randomly selected patent examiners representing nearly all technology areas;

· reviewed USPTO documentation on performance reviews and patent quality initiatives among other things;

· analyzed the USPTO’s Office of Patent Quality Assurance metrics, policies, and data;

· collected data and information on patent pilot programs;

· assessed USPTO pilot programs against leading practices for effective pilot programs; and

· examined USPTO’s patent metrics and literature on alternative indicators of patent value.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making eight recommendations to the USPTO, including that it

· take steps to evaluate ongoing initiatives related to patent examination challenges;

· formalize and document its approach for managing pilot programs;

· update guidance to address limitations in its supervisory quality reviews;

· establish and communicate an overall patent quality compliance goal; and

· assess and adopt alternative measures of the economic or scientific value of patents.

What GAO Found

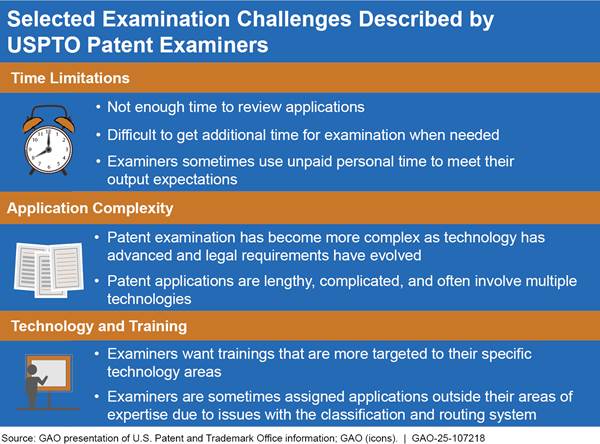

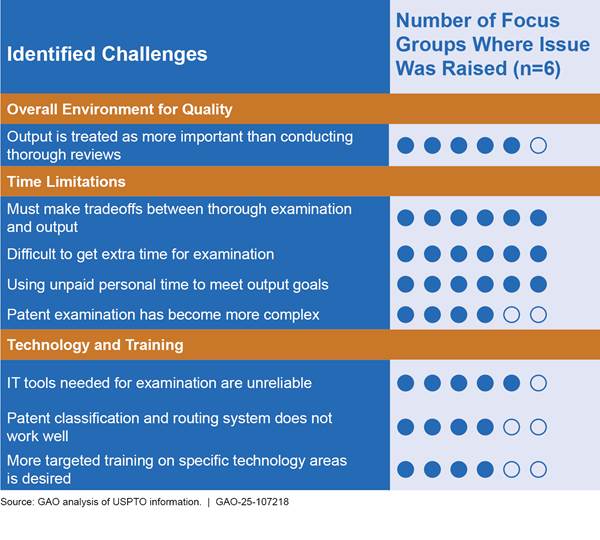

GAO conducted focus groups with nearly 50 patent examiners from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) where they told GAO that they prioritize examination output (i.e., the number of patent applications reviewed) over the quality of the review. The examiners said that the USPTO focuses more on the volume of work completed, which can affect the thoroughness of examinations. This focus on output has persisted since GAO’s review in 2016. Examiners cited a variety of challenges in patent examination, including time pressures, and noted that patent applications have become more complex (see table). Challenges identified by examiners in GAO’s focus groups were also reported in USPTO’s bi-annual examiner surveys.

The USPTO has undertaken several initiatives to address examination challenges and improve patent quality, but it has generally not effectively planned or assessed these initiatives. For example, in fiscal year 2021, the USPTO changed patent examiner performance appraisals to put more emphasis on patent quality but did not evaluate whether this improved patent quality.

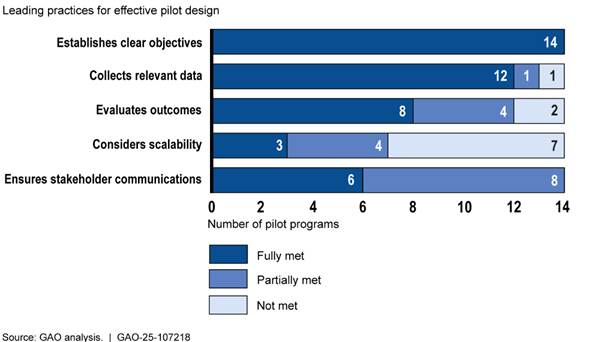

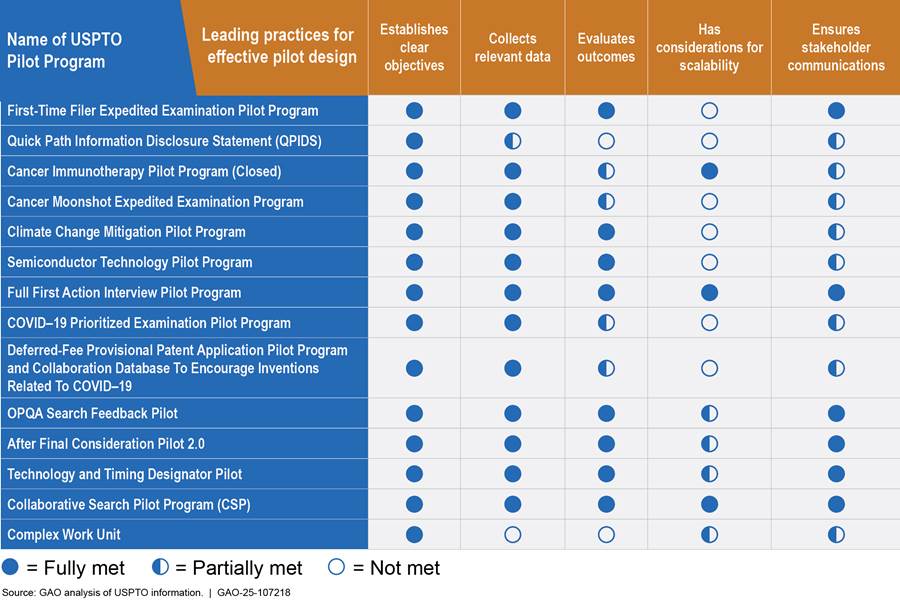

In addition, the USPTO uses pilot programs to develop and test changes to the examination process. However, the USPTO’s implementation of pilot programs is inconsistent, and the agency is missing opportunities to inform future pilots. The agency lacks a formalized structure for the creation and oversight of these programs. GAO found that the USPTO’s pilot programs do not consistently follow leading practices for effective pilot program design. For example, GAO found that seven of the 14 pilot programs did not evaluate outcomes to inform decisions about scalability and when to integrate the pilots into overall efforts.

The USPTO evaluates examiner performance in several ways, including supervisory quality reviews. GAO found that these reviews likely overstate examiners’ true adherence to quality standards and may not encourage examiners to consistently perform high-quality examination. GAO identified several limitations in how the USPTO measures examiner performance:

· Supervisors are not required to use sound selection methods, such as random selection, for the work they review for quality.

· Supervisors can exclude some identified errors from examiner performance evaluations.

· Examiners can receive a passing quality score when all their reviewed work includes errors.

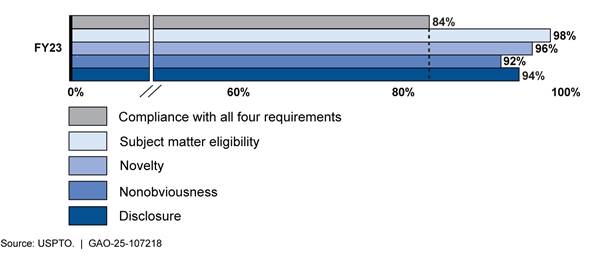

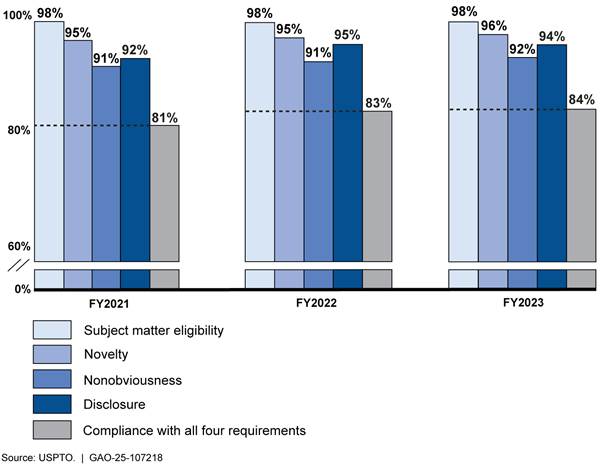

The USPTO measures compliance with each of the four statutory patentability requirements individually (see figure). However, the agency does not have a patent quality goal for the share of patents that should comply with all four requirements at once. According to data the USPTO presented for fiscal year 2023, compliance rates for each of the four statutory patentability requirements ranged from 92 percent to 98 percent, while the percentage of patents simultaneously compliant with all four requirements was 84 percent. By communicating an overall quality goal, the USPTO would provide stakeholders with a more accurate representation of patent quality.

While the USPTO has several measures of patent quality and examination timeliness, it has not tracked or communicated indicators that measure the economic or scientific value of patents, despite having a strategic goal to measure innovation. GAO identified potentially relevant indicators of value in a review of the literature, including how often patents are cited by other patents. Assessing and adopting measures of the economic or scientific value of patents would better position the USPTO to educate and inform Congress, federal agencies, and stakeholders about key trends in innovation across various sectors of the economy, and act on meaningful changes.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

AI |

artificial intelligence |

|

Commerce OIG |

Department of Commerce Office of Inspector General |

|

IDS |

Information Disclosure Statement |

|

OPQA |

Office of Patent Quality Assurance |

|

PICB |

Patent Internal Control Board |

|

PTAB |

Patent Trial and Appeal Board |

|

R&D Unit |

Research and Development Unit |

|

USPTO |

United States Patent and Trademark Office |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 30, 2025

The Honorable Thom Tillis

Chairman

Subcommittee on Intellectual Property

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

Dear Chairman Tillis:

Patents are important engines of innovation and economic growth. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) estimated that in 2019 intellectual property–intensive industries such as electronics and pharmaceuticals support 63 million jobs in the U.S. and contribute $7.8 trillion annually—or 41 percent—to the nation’s gross domestic product.[1]

The U.S. patent system—rooted in the U.S. Constitution—aims, in part, to make innovation more profitable.[2] For example, a patent owner can generally exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the patented technology for up to 20 years. By restricting competition, patents can allow their owners to earn greater profits on their patented technologies than they could earn if these technologies could be freely imitated. Also, the exclusive rights provided by patents can help their owners recoup their research and development costs. On the other hand, any reduction in competition caused by the exclusive nature of patents may result in higher prices for products that use patented technologies. The patent system, therefore, gives rise to complex trade-offs involving innovation and competition. The protection provided by patents, however, is generally understood to ultimately benefit the public through new products and services.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has stated that a quality patent is one that is correctly issued in compliance with the statutory patentability requirements—that an invention is novel, useful, nonobvious, clearly disclosed, and directed at patentable subject matter—and relevant case law at the time of issuance.[3] The USPTO has faced longstanding questions about the quality of patents it issues. For example, we found in 2013 that some stakeholders, including technology companies, judges, and legal scholars, said that some USPTO patents are not high quality, and it should not have issued some patents because they believed these patents did not meet all of the legal standards required.[4]

Although the USPTO uses internal measures of patent quality to track compliance with patentability requirements during the period of examination, some commentators say that patent invalidation rates in the courts suggest that patent quality may be lower than the USPTO’s quality metrics indicate. For example, according to one study, about 40 percent of patents that are challenged in federal courts are found invalid.[5] Although the number of patents that are later challenged is small and may not be representative of all granted patents, these challenges can negatively affect public perception of patent quality, according to the USPTO.[6]

According to academic researchers, patents that do not meet the patentability requirements can impose significant costs on society. For example, low quality patents can force businesses to pay to use patented technology that may not meet patentability requirements. Further, settling a patent dispute in the federal courts can be expensive.

Inventors are more likely to engage in costly patent litigation when the USPTO issues patents that do not fully comply with patent law. Patent experts and practitioners have also questioned whether patent examiners, and the USPTO as a whole, have greater incentives to issue a patent than to reject one—regardless of the quality of the application. The USPTO has acknowledged the need to focus additional attention on patent quality. In 2014, the USPTO’s deputy director stated an increased focus on patent quality would play a significant role in curtailing patent litigation.[7] In this report, we refer to high quality patents as those that fully meet federal patentability standards.[8]

You asked us to review various issues related to patent examination and quality at the USPTO. Specifically, this report (1) examines challenges that USPTO patent examiners face that could affect the quality of issued patents; (2) assesses initiatives the USPTO has taken to improve patent quality, including pilot programs, and the extent to which the agency has measured the effectiveness of those initiatives; (3) evaluates how the USPTO assesses patent quality and examiner performance regarding quality; and (4) assesses how the USPTO communicates patent quality externally.

We reviewed USPTO documentation related to patent examination and patent quality and interviewed agency officials, patent scholars, and practitioners. For objective 1, we convened six focus groups with nearly 50 patent examiners. The examiners were randomly selected and grouped by experience level and technology center. A trained GAO facilitator guided the discussions using a standardized list of questions to identify and understand examiners’ perspectives on patent quality and examination. Additionally, we reviewed the results of the USPTO’s Internal Quality Perception surveys of patent examiners from fiscal years 2021 to mid-2024.[9]

For objective 2, we assessed USPTO pilot programs against GAO’s leading practices for effective pilot programs and federal standards for internal control. Furthermore, we assessed the USPTO’s internal oversight board and agency initiatives against key practices for evidence-based policymaking.[10]

For objective 3, we analyzed patent quality metrics, policies regarding quality reviews, and quality review data from the USPTO’s primary quality assurance body, the Office of Patent Quality Assurance (OPQA). We also reviewed USPTO practices for assessing patent examination quality.

For objective 4, we examined the USPTO’s patent metrics and conducted a literature review on alternative indicators of patent value. We evaluated the USPTO’s efforts against federal internal control standards and the USPTO’s strategic goals. Appendix I provides more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Patent Applications and Patent Examiners

In fiscal year 2024, the USPTO received approximately 527,000 new patent applications and granted about 365,000 patents—which can include some applications received in the preceding years. A patent application includes certain key elements, particularly the specification and the claims. The specification includes a written description of the invention and the process to make and use it, while the claims define the boundaries and breadth of the patent. Applications can also include an abstract, drawings, and an information disclosure statement with references to prior art. Prior art refers to information, including other issued patents, patent applications, or technical literature such as scientific or technical books and journals.

The USPTO employed 8,944 patent examiners at the end of fiscal year 2024 who review applications to determine whether the claimed inventions merit a patent or whether the application should be rejected, among other things. Patent examiners are grouped into nine distinct technology centers that are focused on specific scientific or technical areas, such as electrical, chemical, and mechanical technology fields. Technology centers are further divided into art units, which are groups of patent examiners who specialize in a specific technology. For example, the art unit for electrical circuits and systems is housed within a technology center focused on electrical systems.

Patent examiners span a wide range of experience levels. Examiners are skilled engineers, scientists, and technology professionals. An examiner’s authority expands with each promotion. Examiners are held responsible for the quality of the steps corresponding to their respective seniority level but, regardless of seniority, are expected to complete all steps of the examination process. Patent examiners are hired as junior examiners. They move from junior to primary examiners after successfully completing a program to obtain signatory authority. While junior examiners must have their work reviewed and approved by a primary examiner before issuance, signatory authority permits primary examiners to sign off on their own work. However, primary examiners still have a sample of their work reviewed by their supervisor for performance evaluation purposes.

Patent Application and Examination Process

When a patent application is submitted, the USPTO reviews it to ensure all parts of the application are complete and then contractors classify it by technology type. Patent classification routes each application to an examiner with the appropriate technical expertise to review the application material. Classification allows examiners to identify relevant information more easily when conducting prior art searches by organizing patents into specific technology groupings based on common subject matter. Examiners spend a large percentage of their allocated examination time searching existing patents and applications in the U.S. and abroad, scientific journals or other prior art to determine if the application meets the patentability requirements for a patent and thus help ensure the validity of granted patents.[11]

After their first review, a patent examiner issues a first office action to notify the applicant of the results of the initial review. If rejected, the applicant may amend their application or provide a response supporting patentability, which would prompt the examiner to complete a second review and issue a final decision to approve or reject the claims.[12] If the claims are rejected, the applicant may file for additional examinations. If a patent is to be granted, the USPTO issues the patent to the applicant once certain fees are paid. The patent can generally remain in effect for up to 20 years from the date on which the application for the patent was filed.

All office actions are reviewed for compliance with patentability requirements and require signature by primary examiners. Further, OPQA reviews a subset of first and final decisions after the examiner’s work is complete to ensure compliance. Applicants and others can appeal an examiner’s decisions—including issued patents—before the USPTO’s Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), such as through an appeal or a trial after the patent has been granted. USPTO decisions may also be challenged in federal courts. Appendix II provides a general overview of the patent examination process.

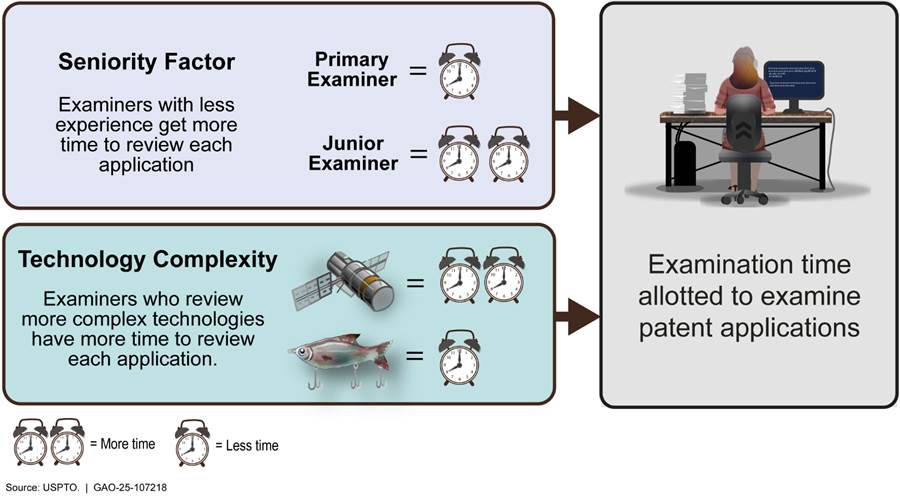

USPTO Patent Examination Time and Output

The timely issuance of high quality patents by examiners is critical to providing businesses and entrepreneurs the certainty they need to invest in, develop, and launch innovative new products and services. To ensure decisions on patent application are made in a timely manner, the USPTO establishes overall output goals for examiners, which determine the volume of work an examiner must complete to meet their output performance expectations.[13] An examiner’s output goal is calculated based on their seniority level, the technological complexity of the applications they review, and the number of hours they spend on examination activities. More senior examiners have higher output goals and are expected to conduct their examinations more quickly compared to examiners with less experience. Examiners working with more complex technology are given more time to complete their work than examiners reviewing applications with less complex technology. Lastly, examiners are expected to complete less work, and, thus, have lower output goals when they take vacation or participate in training or other non-examination activities.

The USPTO uses similar factors to determine the number of hours examiners are expected to spend reviewing each application. The USPTO allots a certain number of hours for each examiner to review an application based on the examiner’s seniority level and the technological complexity of the application (see fig. 1). For example, one examiner may be allotted 16.6 hours to complete examination for a patent application related to fishing lures, a less complex technology. However, the same examiner may be allotted 27.7 hours to complete an application related to satellite communication due to the higher level of technological complexity. Examiners with less experience get more time to complete their reviews. For example, a junior examiner may be allotted 30.2 hours to review a patent application related to fishing lures, more than double the amount of time an examiner at the highest level of seniority would receive to examine the same application.

The USPTO measures examiners’ output using units called counts. Examiners

achieve counts by completing specific tasks. For example, each examination

includes a first office action in which the examiner explains their decision

whether to grant a patent. The first office action is worth 1.25 counts. Other

activities that occur later in the examination process, such as a second office

action after the examiner has received and reviewed the applicant’s response to

the initial office action, are worth up to 0.5 counts. The USPTO’s count system

gives patent examiners incentive to spend more time on initial examination

activities, which earn more counts and contribute more toward achieving

examiners’ output goals. The USPTO generally incentivizes examiners to spend

less time on later stages of the examination process, regardless of the volume

of material to be reviewed in response to the examiner’s initial office action.

USPTO Patent Examination Quality

The USPTO defines a quality patent as one that is statutorily compliant. To meet quality standards, examiners determine if a patent application meets each of the applicable statutory patentability requirements. Table 1 provides an overview of the statutes that patents must comply with to meet quality standards. While the USPTO uses these statutory categories for quality metrics reporting, other standards, such as applying agency case law guidance, contribute to quality standards.

|

Patent requirement |

Statutory source |

Description |

|

Patentable subject matter |

35 U.S.C. §101 |

This provision contains implicit exceptions to what may be patented. Specifically, laws of nature, natural phenomena, and abstract ideas are not patentable. |

|

Novelty |

35 U.S.C. §102 |

Under this provision, a patent applicant may not receive a patent on an invention that is not new. Examiners refer to prior patent and non-patent materials, known as prior art, to determine novelty. |

|

Nonobviousness |

35 U.S.C. §103 |

This provision prohibits applicants from receiving a patent on an invention that is an obvious extension of a previous innovation. Examiners must consider the differences between the prior art and the claimed invention, among other factors, to determine if an application meets this requirement. |

|

Clear disclosure |

35 U.S.C. §112 |

A patent application must contain a thorough and clear description of the invention and set out the claims for which a patent is sought. This section sets forth the minimum requirements for the quality and quantity of information that must be contained in a patent application. |

Source: GAO analysis of statutory patent requirements. | GAO‑25‑107218

To determine compliance with these statutes, examiners must search through prior art to determine if an invention is novel and nonobvious, which is a time-intensive process that can take about half of the 20 hours that examiners have on average for each application. Pressure to complete timely application reviews competes with pressure to issue quality patents. The USPTO balances the time allocated for prior art search and thorough examination with the need for timely examination of and decisions about claimed inventions.

The USPTO has three primary mechanisms for measuring patent and examination quality including

· Supervisory quality reviews. USPTO guidance calls for supervisors to conduct at least two supervisory quality reviews each quarter for each examiner they oversee (about 6 percent of total office actions issued). In these reviews, supervisors review patent examination decisions made by the examiners they oversee to identify whether the examiner made a “clear error” or mistake during the review of a patent application. Supervisory quality reviews differ by seniority level. For examiners who are grade GS-12 and above, quality is determined in part by calculating an “error rate” for each examiner. The error rate is determined by dividing the number of supervisory quality reviews that identify a “clear error” by the total number of office actions issued by the examiner during the fiscal year. The error rate is not used for quality evaluation for junior examiners at grade GS-11 and below as their work is reviewed and approved by primary examiners. Once the examiner responds to supervisory comments, actions are reviewed for compliance with USPTO requirements, including statutory compliance. The results of supervisory reviews are used to provide feedback to examiners and inform their performance ratings.

· Quality assurance reviews. Within the USPTO, OPQA conducts independent quality reviews of an examiner’s completed work to determine compliance with the statutory patentability requirements. Quality assurance specialists review a random selection of completed office actions. OPQA assesses other aspects of patent examination, such as the completeness and quality of prior art search. The results of these reviews provide insights about compliance trends within and across technology centers.

· OPQA data integrity reviews. For these reviews, OPQA assesses whether its quality assurance specialists are consistent in their reviews of examiners’ work, including their application of quality assurance standards to reach decisions on whether an examiner’s work met quality standards.

Over the last decade, GAO and Commerce OIG have highlighted challenges affecting the USPTO’s ability to conduct thorough and complete patent examinations. For example, in June 2016, GAO found that the USPTO did not have a consistent definition of patent quality, the USPTO had not fully developed specific performance measures to assess progress toward patent quality goals, and patent examiners reported not having enough time to conduct a thorough patent examination, among other findings.[14] In December 2021, Commerce OIG found, among other things, that the USPTO’s quality review practices may not provide an accurate measure of patent examination quality and that the agency lacked the means to control or measure examination consistency.[15]

Patent Examiners Cited Persistent Challenges Regarding Patent Examination and Quality

USPTO examiners face a variety of challenges during patent examination that can affect the thoroughness of patent examination and, in turn, the quality of patents issued by the USPTO. To understand the challenges patent examiners face, we conducted six focus groups with patent examiners and reviewed examiner surveys conducted by the USPTO. Examiners in our focus groups said there was generally more emphasis on examining a large quantity of patents than ensuring the quality of issued patents, a condition which has persisted since GAO’s review in 2016. As shown in figure 2, examiners also identified specific challenges related to time pressures to sufficiently review patent applications and limitations with training and technology.

Examiners Said That the USPTO Emphasizes Output Over Quality

Examiners expressed that the USPTO places greater emphasis on meeting output goals for the number of applications reviewed over issuing quality patents. USPTO staff “at the management and supervisor levels are more concerned about [output] than quality,” according to the fiscal year 2023 quarter 4 USPTO examiner survey.[16] In 2014, a former USPTO official stated in testimony before two congressional committees that “there was a saying during my tenure at [the USPTO] that a patent examiner never got fired for doing bad quality work, as long as they did a lot of it.”[17] Ten years since this testimony, this sentiment was shared across most of our examiner focus groups.

Examiners in our focus groups also highlighted that this emphasis on output is formalized in financial incentives—such as bonuses—that examiners receive for meeting or exceeding their output and timeliness expectations. There are no similar incentives for achieving quality goals. In 2016, GAO found a similar emphasis on examination output and recommended the USPTO analyze how performance incentives affect the extent to which examiners perform thorough patent examinations.[18] The USPTO implemented the recommendation although the focus on output over quality persists according to examiners.[19]

|

Examiner Perspectives on Output Goals and Incentives for Meeting Quality Standards “[Output] is the name of the game. The quality should be good enough and [output] should be as high as possible.” “Incentives are based around [output] almost exclusively. There are no awards or incentives for quality. It’s all about the quantity and throughput. You can get dinged for quality and be [fine], but if you don’t meet [output] you are gone from the job.” |

Source: USPTO patent examiners in GAO focus groups. | GAO‑25‑107218

Examiners Have Limited Time to Meet Quality Standards and Output Goals

Examiners in our focus groups noted time pressures as a central challenge to completing thorough examination of patent applications to ensure they meet patentability requirements, USPTO guidance, and case law while also meeting output goals.

Time Constraints Hinder Thoroughness of Prior Art Search. Examiners in all six focus groups said they aim to produce work that meets quality standards in the time they are given; however, in most of our focus groups, examiners noted they often do not complete a thorough search of prior art due to time constraints. Approximately 40 percent of examiners’ time is spent conducting searches of prior art—existing patents and other scientific literature—which examiners review to determine if a patent is novel and nonobvious. Examiners in some of our focus groups shared that they could likely find prior art that is more directly related to the patent application if they had more time.

As more patents are issued over time and the body of scientific literature increases, the body of prior art grows, giving examiners more material to review.[20] In the USPTO patent examiner survey from fiscal year 2023 quarter 4, examiners noted they need more time for examination as the body of prior art is continually expanding. Further, primary examiners—those with the authority to self-certify the quality of their work—may face heightened time pressures because they have higher output expectations for the number of patent applications they need to complete as compared to junior examiners.

The issue of time constraints is long standing and GAO recommended in 2016 that the USPTO assess the time examiners need to conduct a thorough prior art search for different technologies.[21] While the USPTO performed this assessment, USPTO officials said there are diminishing returns to providing more time for examination, and agency surveys of patent applicants suggest they are satisfied with current timeliness and quality levels.

Complex Applications Exacerbate Time Pressures. Examiners noted that patent applications have become more complex over time, which can exacerbate time pressures. Examiners in most of our focus groups identified the challenge of being assigned to examine applications with technologies unfamiliar to them while they also face the challenge of examining a large body of prior art. For example, an examiner in one focus group shared that technologies like CRISPR or mRNA were not prevalent when they obtained their degree but are now important in their field of study. Additionally, examiners in some of our focus groups described how some patent applications include multiple technologies, such that no single examiner would be familiar with all the technologies relevant to the application.

In addition to keeping pace with emerging technologies, examiners must also keep pace with the growing case law that can result in changes to patentability standards, as described in some of our focus groups. According to USPTO officials, the agency issues timely guidance and has a number of initiatives designed to help examiners navigate the evolving legal landscape.

|

Examiner Perspectives on Keeping Pace with Emerging Technologies “Sometimes there are technologies I need to review that were not taught when I was in school and that I do not have background knowledge on. [I] need to spend time to learn about the technology…but I am not given enough time to… research… to fully come up to speed.” “A lot of the cases on my docket relate to cancer testing and measurement, but I end up looking at a lot of different areas as well. For example, I also get cases where AI is being applied in a biology field. I need to take time to get familiar with this particular AI technology when this happens and also need to spend more time and effort searching for prior art.” |

Source: USPTO patent examiners in GAO focus groups. | GAO‑25‑107218

Applicant Behavior Can Add to Time Pressures. Participants in some of our examiner focus groups shared that patent applicants sometimes file long or complicated amended patent applications to exploit the time pressures that examiners face. As described earlier, after patent examiners issue an initial office action, applicants may amend the claimed invention in their application. However, within the patent examination process, the bulk of the time examiners are given is for reviewing the initial application and making the initial office action. Examiners are given less time to review an amended application and issue a final office action.[22]

In USPTO’s fiscal year 2023 quarter 4 examiner survey, examiners described a practice where applicants “write initial claims that are so broad they obscure the purported invention and then amend [the claims] heavily in response to the first [office] actions.” The USPTO’s examiner survey from 2021 through 2023 also show that examiners do not believe applicants are writing clear claims, providing a manageable number of claims, or drafting claims that clearly capture the concept of the invention. The fiscal year 2023 quarter 4 survey states that examiners believe that patent applicants do this because “they want to force an allowance [of the patent].”

USPTO officials acknowledged this practice, and explained that, at the time of filing, the commercial viability of an invention may not be clear, and an applicant may make the business decision to invest fewer resources into filing the initial claims. When the commercial viability of an innovation has become clear, applicants have greater motivation to invest greater resources into filing more thorough claims.

|

Examiner Perspectives on Reviewing Amended Patent Applications “Some applicants heavily amend their application after the first rejection to the point where it is essentially a new application. However, I get much less credit for this review than I did for the initial review of the application, even though I have to do … the same amount of work.” “Applicants know we get very little time for final rejections. The first action is usually straightforward, but when [applicants submit revisions for their secondary examination], they rewrite the entire claim set and I can’t reexamine the entire thing in 4 hours, which is [the time] I get for final rejections.” |

Source: USPTO patent examiners in GAO focus groups. | GAO‑25‑107218

In addition, examiners in some of our focus groups identified long information disclosure statements as a challenge. Specifically, patent applicants are required to include an information disclosure statement as part of their application to disclose prior patents that are relevant to their claimed invention. Examiners noted that applicants include large volumes of prior patents in their disclosures, knowing that examiners may not have sufficient time to completely review all of them given the time pressures to meet output goals. The USPTO’s examiner surveys from 2021 through 2023 highlighted similar challenges and noted that applicants are not adequately citing material relevant to patentability in information disclosure statements. According to USPTO officials, this might be occurring because applicants fear being perceived as misrepresenting or omitting information with an intent to deceive the USPTO.

Examiners have difficulty getting extra time and reported sometimes working unpaid hours. Examiners in all our focus groups shared that it is generally difficult to get additional examination time needed to adequately review applications, including applications that are lengthy or include complicated or unfamiliar information. Participants in some of the focus groups also shared that, when extra time is given, it is usually insufficient. A USPTO official told us that examiners can request additional time from their supervisor to examine an application. However, examiners in some focus groups noted that getting extra time is largely dependent on supervisor preferences.

|

Examiner Perspectives on Getting Approval for Additional Review Time “Asking for additional time in my art unit is a cardinal sin.” “Extra time is often very limited. It is typically 1 to 2 hours, maybe 3 to 4 max. This does not match the [many] hours needed to spend to complete the task extra time is being requested for.” “I didn’t even know asking for extra time was an option.” |

Source: USPTO patent examiners in GAO focus groups. | GAO‑25‑107218

Examiners also said that they work unpaid hours or work during paid leave hours to review patent applications to achieve output expectations.[23] A USPTO examiner survey from fiscal year 2023 quarter 2 states that examiners “have to do work on their own time without compensation, particularly for complicated cases.” Examiners in all our focus groups shared similar sentiments. Participants in some of our groups also noted a practice in which examiners take paid vacation time with the intention of completing examination work during that time to meet their output goals.[24]

Examiners Expressed Challenges with Technology and Training

In our focus groups and the USPTO’s surveys, examiners expressed various challenges with technology and training that hinders their work. Specifically, they cited issues with unreliable examination tools, the patent classification and routing system, and the need for more targeted training. Our 2016 survey of examiners found similar issues, including that additional search tools would make prior art search easier, and that many applications were misclassified.[25] We made several recommendations, including that the USPTO assess ways to provide access to key sources of nonpatent literature and to address gaps in technical training. Although the USPTO implemented our recommendations, the issues examiners raised suggest that issues with examination tools, classification, and training persist.[26]

Examination tools are unreliable. The primary tools examiners use are for searching prior art, drafting and distributing official correspondence, and viewing documents such as application materials, according to a USPTO official. In the fiscal year 2024 quarter 2 USPTO examiner survey, the share of patent examiners who reported being “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” with specific technology tools was 46 percent for prior art search tools. This sentiment was echoed in our focus groups, with examiners in most of the groups describing that the necessary technology and tools did not work consistently and were often not functioning. USPTO fiscal year 2023 examiner surveys reported that examiners are eager for updates from the USPTO on plans to use artificial intelligence (AI) in the patent examination process as the AI tools currently available prolong examination time and are not yet useful.[27]

|

Examiner Perspectives on Technology Challenges “We’ve been dealing with a lot of tech issues lately with search tools. If I’m in the middle of something…it’s hard to get back into your rhythm if you stop working.” “There [are] problems with [the] search [system]; every time I use it, it breaks down in one way or another. Buttons just stop working and [it] crashes. It is not hyperbole; it does not work every day.” |

Source: USPTO patent examiners in GAO focus groups. | GAO‑25‑107218

The patent classification and routing system does not work well. Examiners described concerns with the patent classification and routing system, saying it incorrectly assigns applications to examiners without the right expertise, and examiners are not easily able to get the applications reassigned.[28] This can result in some examiners examining unfamiliar technology. In the fiscal year 2023 quarter 2 examiner survey, examiners reported that the classification and routing system the USPTO uses to assign patent applications to examiners “has had a negative impact on quality with cases assigned to the wrong examiners” and is “broken,” “ineffective,” and “completely wrong.”[29] These problems were also documented by Commerce OIG in 2023.[30]

In addition to the classification and routing system not working well, examiners reported in the fiscal year 2023 quarter 2 USPTO examiner survey that the current process for reassigning incorrectly assigned applications puts the responsibility for reassignment on examiners. Examiner survey respondents reported that because the process to reassign applications is time consuming, examiners are deterred from attempting to reroute applications they believe were incorrectly assigned to them. As a result, examiners often proceed with reviewing patent applications containing unfamiliar subject matter. Examiner survey respondents reported that “classifications need to be more easily reassigned” and that examiners consider the automated classification system to be a “severe burden.”

Additionally, the challenges caused by a misclassified application are not isolated to that application but can extend to future applications. A misclassified application that becomes an issued patent then becomes prior art that is improperly classified within search systems. Misclassified applications may be difficult to find when future examiners search for patent literature using technology-specific patent classification categories. The misclassified application will also now appear in search results for the classification category it does not belong in, which can clutter search results within that classification and make identifying relevant prior art more difficult.

|

Examiner Perspectives on How Patent Applications are Assigned “[T]here are too many new and unfamiliar technologies being put on my docket.” “Once an application is [assigned], it is difficult to get it reassigned, even if it is something not related to the expertise of the examiner. It can technically be done, but there are many hoops that must be jumped through and it is not a given that it will be reassigned even if those hoops are jumped through.” |

Source: USPTO patent examiners in GAO focus groups. | GAO‑25‑107218

Examiners said they need more technology-specific training and improved information sharing. Examiners in most of our focus groups shared the need for training that is more targeted to their specific technology area or art unit. Most of our focus groups also shared that when examiners are expected to learn about new or unfamiliar technologies, such as when applications are misclassified, they must teach themselves. Recent USPTO examiner surveys have repeatedly indicated that examiners desire more technology-specific training. For example, the fiscal year 2023 quarter 4 USPTO examiner survey found that examiners expressed a desire to have subject matter experts available for questions that require specialized knowledge when their supervisors are not available to help them.

Additionally, examiners said they are not allowed to reproduce or share certain training materials they obtain from supervisors and quality assurance specialists because the Office of Patent Legal Administration (OPLA) must vet materials before they can be reproduced or distributed.[31] Examiners in some of our focus groups reported that they would prefer if these informal training materials could be copied and shared for future reference.[32]

USPTO officials said the Office of Patent Training has a number of programs that target technical training.[33] Further, USPTO officials told us that the agency has taken steps focused on examiner training for emerging technologies and AI, including launching an AI and emerging technologies lecture series in October 2024, working with a university to develop an AI curriculum for its examiners, and developing plans to launch an AI learning portal.

The USPTO Has Not Assessed Whether Efforts Have Improved Persistent Challenges

We found several USPTO initiatives are aimed at addressing patent examination challenges, although the USPTO has not assessed to what extent these initiatives have led to improvements. We also found that the USPTO is using several pilot programs to develop and test changes to the patent examination process, although the USPTO has not consistently followed leading practices in implementing its pilot programs.

The USPTO Has Not Evaluated Its Initiatives to Improve Patent Examination

The USPTO has taken several actions to improve patent quality and address examination challenges described earlier; however, the agency has not effectively planned or assessed its efforts. GAO has identified key practices that can help federal agency officials develop and use evidence to effectively manage and assess the results of federal efforts.[34] Since our work in 2016, the USPTO has taken many efforts to improve patent examination. Some of these efforts, which are ongoing, include

Increased examination time. In 2019, the USPTO reevaluated examination time. This led to an increase in the amount of time allotted to examiners to review a patent application by an average of about 9 percent across all examiners, varying by several factors, including the application’s complexity (eg, the length of the application and the number of claims). According to the USPTO, since its recalibration of examination time, 27 percent fewer office actions were noncompliant with patentability requirements (decreasing from 2,708 in fiscal year 2020 to 1,984 in fiscal year 2023). However, in our focus groups and in USPTO examiner surveys from fiscal years 2021 through 2023, examiners reported that they still do not have enough time for examination—an issue that dates to our prior work in 2016.

While USPTO officials say that applicants are satisfied with the level of patent quality, the USPTO has not rigorously evaluated the effects of examination time on statutory compliance. This is because the agency has not developed specific goals related to patent quality for the increase in examination time. According to evidence-based policymaking practices, desired long-term outcomes should be broken down into performance goals to ensure that progress can be assessed.[35]

Prior art search improvements. The USPTO has taken steps to improve prior art searches, including by incorporating AI into the search system. For example, the agency has added AI capabilities to search features, such as an AI tool that identifies domestic and foreign patent documents that are similar to the application being reviewed and search features including “more like this document” and “similarity search.” As of September 2023, examiners have conducted more than 1.3 million search queries using these AI-powered features. According to the USPTO, improving examiner tools, such as by incorporating AI into search, strengthens the prior art search, and offsets challenges from examiner time constraints and application complexity.

The USPTO collects data on how much examiners use these tools, such as the number of times tools are accessed per day and the number of requests for data from the tools. However, this information alone does not enable the agency to understand the effect of these changes. This is because the USPTO has not assessed whether these changes have allowed examiners to identify more appropriate prior art. In addition, in USPTO surveys, examiners have said that AI tools currently available prolong examination time and are not yet useful. According to evidence-based policymaking practices, evaluations that assess implementation, outcomes, and impact can help the agency assess progress toward strategic goals and objectives related to patent quality.[36]

Performance appraisal plan changes. In fiscal year 2021, the USPTO updated examiners’ performance appraisal plans to better align examiner goals and agency priorities. This included changing the performance appraisals to put more emphasis on finding the best prior art earlier in examination. The updates also made performance elements for output and quality equally weighted. According to the USPTO, these changes allow the agency to hold examiners more accountable for quality. However, it is not clear what impact these changes have had on patent examination or patent quality. This is because the agency has not assessed how the new performance appraisal plans affect patent examination thoroughness or other aspects of quality. According to evidence-based policymaking practices, assessments can help the agency better understand what factors led to the results it achieved or why desired results were not achieved.[37]

To address the need to evaluate agency efforts, the USPTO created two bodies comprising USPTO staff at different levels. The first is a Research and Development (R&D) Unit—a group of experienced senior examiners who have broad knowledge of examination procedures. Created in November 2022, the R&D Unit is designed to help identify challenges to patent examination, develop ideas to address these challenges, and test and evaluate those ideas in a controlled environment. The R&D Unit consists of a rotating cohort of examiners from each technology center and had 36 examiners in 2024. According to USPTO officials, the R&D Unit has completed tests on several topics, such as on information disclosure statements, and the agency was conducting additional tests related to these topics at the time of our review (see textbox). According to USPTO officials, ideas that prove useful in the R&D Unit could be implemented across the agency and thus improve patent examination.

|

USPTO Initiative to Examine Possible Improvements The USPTO research and development (R&D) Unit is exploring the factors and relevancy of the information disclosure statements (IDS) and how they could inform decisions about future improvements. In the first phase of testing, the USPTO collected 236 survey responses from 36 examiners in the R&D Unit from March through May of 2024. The agency used these survey responses for multiple statistical analyses to determine which characteristics of the IDS impact the complexity of the IDS the most, among other things. According to the results of the first phase of this study, the number of prior art references included in the IDS does not always affect the amount of time an examiner spends reviewing the IDS. For example, of the applications that had over 100 references in the IDS, approximately 29 percent took less than 1 hour to review, while approximately 41 percent took 3 to 4 hours to review. The second phase of the test was conducted from May 2024 through July 2024 and involved two groups of examiners. Examiners in the first group conducted a search for prior art before examining the IDS. Examiners in the second group ignored the IDS when determining if an application was patentable and afterwards examined the IDS. The purpose of this phase of the testing was to determine how the inclusion of an IDS affects patentability decisions. Preliminary results of this phase showed that approximately 93 percent of examiners in the second group did not change their first office action after reviewing the IDS. |

Source: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). | GAO‑25‑107218

The second body the USPTO established is the Patent Internal Control Board (PICB), created in 2022 to provide oversight, accountability, and analysis of select patent initiatives and activities. PICB consists of senior USPTO officials and is responsible for reviewing and analyzing data and proposals related to the USPTO’s long-term goals. These responsibilities include conducting risk assessments, prioritizing the allocation of resources for operations and technology improvements, reviewing trends in agency data, monitoring agency operations, and recommending changes to management.

Although the structure of the PICB is still being finalized, officials said they have developed guidance for internal control practices to inform the board’s oversight of programs and initiatives. Using input from the Commissioner of Patents, the board is currently assessing changes to the examiner hiring process, as well as changes to examination time and application routing. USPTO officials told us that the board was designed for new initiatives and that any assessment of ongoing initiatives would occur only if pertinent to the board’s current oversight work. Given this, PICB does not currently have plans to evaluate all of the ongoing initiatives described above.

While the R&D Unit and PICB have a role in evaluating future USPTO initiatives, there is still a need to evaluate the effect of ongoing initiatives given the persistent nature and extent of challenges patent examiners face as described in our focus groups. For example, the agency has not expanded its current examiner surveys to collect data on all changes affecting patent examination, such as collecting examiners’ views on changes to performance appraisals. Such input from examiners could identify deficiencies or improvements that are not captured in current examiner surveys or the USPTO’s monitoring of examiner tools. While the USPTO has said they used OPQA data to improve the clarity of office actions, the USPTO has not used data from OPQA random quality reviews to conduct causal analyses related to changes to the patent examination process such as prior art search changes.[38] Such analyses could help the agency determine which initiatives most support patent examination and quality goals and how to use its limited assessment resources.

We found that the USPTO’s lack of clarity on the effects of the initiatives described above exists because USPTO management has not required officials in charge of programmatic changes to set clear goals, develop measurable performance indicators, or fully evaluate the results of internal policy changes. As noted above, GAO has identified key practices that can help federal agency officials develop and use evidence to effectively manage and assess the results of federal efforts.[39] Evidence can improve management decision-making, which helps to ensure that the organization’s activities are targeted at further addressing problems and achieving desired results. Without properly planning for policy changes and monitoring and evaluating the resulting outcomes, the USPTO may not be able to determine if the policy changes accomplished their intended objectives, should continue as implemented, or should be adjusted to help ensure their effectiveness.

The USPTO Has Not Consistently Followed Leading Practices for Pilot Programs

In addition to initiatives described above, the USPTO also uses pilot programs to develop and test changes to the patent examination process. According to a former agency official, pilot programs are beneficial because they allow the agency to quickly make changes to patent operations. We have previously reported on the benefits of pilot programs to produce information needed to make effective program and policy decisions and ensure effective use of time and resources.[40] In our analysis of documentation and discussions with the agency, we identified 14 pilot programs that are either currently active or were active since 2016.

|

Patent Examiners’ Perspectives on Pilot Programs Examiners in three focus groups mentioned that pilot programs to prioritize or expedite certain applications affect their ability to manage their work. Specifically, two examiners in one focus group said such pilot programs complicate their docket management because applications assigned through prioritized or expedited pilot programs come in unexpectedly and change the order in which they need to review applications. Further, one of these examiners explained that

applicants pay more fees to expedite their applications. However, examiners

are not given extra compensation for examining them more quickly, and it is

difficult for examiners to balance docket management and productivity ratings

with multiple deadlines assigned to them for each action. Another examiner

said that some pilot programs make examination more complicated since they

are not granted any additional time for the tasks required by the pilot

program. Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107218 |

· Six of the 14 pilot programs expedite the examination of patent applications. Five of these pilot programs expedite the examination of patent applications for certain technologies, and one of these pilot programs expedites the examination of patent applications for first-time patent applicants. For example, the Semiconductor Technology Pilot Program expedites patent examination for technologies related to the manufacturing of semiconductors. According to the USPTO, the agency often uses these types of pilot programs to support White House initiatives, such as the Cancer Moonshot Expedited Examination Pilot Program, which expedites applications related to cancer and supports White House efforts on cancer research.

· Five of the 14 pilot programs we identified are designed to improve different aspects of the patent examination process. For example, the Collaborative Search Pilot Program provides additional resources for prior art searches. The Full First Action Interview Pilot Program allows applicants to participate in interviews with their assigned patent examiner before the issuance of a first action.

· Three of the 14 pilot programs focus on other areas of patent examination. For example, the Deferred-Fee Provisional Patent Application Pilot Program allowed applicants to defer the payment of associated application fees if the applicant’s invention was related to COVID-19.

GAO previously identified five leading practices that, taken together, form a framework for effective pilot design.[41] By following these leading practices, agencies can promote a consistent and effective pilot design process. A well-developed and well-documented pilot program can help ensure that agency assessments produce information needed to make effective program and policy decisions. Such a process enhances the quality, credibility, and usefulness of evaluations in addition to helping to ensure that time and resources are used effectively. In our analysis of information from the USPTO, we found that the agency’s pilot programs have not consistently followed leading practices (see table 2 and fig. 3).

Table 2: Alignment of the USPTO’s Pilot Programs with GAO’s Leading Practices for Effective Pilot Design

|

Leading Practice |

GAO Assessment |

|

Establishes clear objectives Establish well-defined, appropriate, clear, and measurable objectives. |

We found that all 14 pilot programs had well-defined, appropriate, clear, and measurable objectives. For example, the First-Time Filer Expedited Examination Pilot Program is designed to increase accessibility to the patent system for inventors in historically underserved geographic and socio-economic areas. The program supports these inventors, who are new to the patent application process, by reducing the time needed to reach a first action for their applications. |

|

Collects relevant data Clearly articulate assessment methodology and data-gathering strategy that address all components of the pilot program and include key features of a sound plan. |

We found that 12 of the 14 pilot programs had a clearly articulated assessment methodology and data-gathering strategy, one of the 14 pilot programs somewhat followed this leading practice, and one of the 14 pilot programs did not follow it. For all six of the pilot programs that expedite patent examination, the USPTO collected relevant data, including the number of requests to use the programs, the status of requests, and the status of related patent applications. |

|

Evaluates outcomes Develop a detailed data-analysis plan to track the pilot program’s implementation and performance, evaluate the final results of the project, and draw conclusions on whether, how, and when to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts. |

We found that eight of the 14 pilot programs had developed a detailed data-analysis plan to assess the effectiveness of the programs, four of the 14 pilot programs partially followed this leading practice, and two of the 14 pilot programs did not follow it. For example, the Office of Patent Quality Assurance’s Search Feedback pilot program had a data-analysis plan that incorporated multiple forms of feedback from patent examiners to track the pilot program’s outcomes. However, the Complex Work Unit Pilot Program does not have records of the data collection or evaluation procedures. |

|

Considers scalability Identify criteria or standards for identifying lessons about the pilot program to inform decisions about scalability and whether, how, and when to integrate pilot activities into overall efforts. |

We found that three of the 14 pilot programs had established criteria or standards for identifying lessons to inform decisions about scalability or integrating the pilot programs into overall agency efforts, four of the 14 pilot programs partially followed this leading practice, and seven of the 14 pilot programs did not follow it. For example, the First-Time Filer Expedited Examination Pilot Program did not have any standards for identifying lessons about the scalability of the program. Alternatively, the USPTO tested the Full First Action Interview Pilot Program on a small scale to inform decisions about making the program available to other patent applications. |

|

Ensures stakeholder communication Ensure appropriate two-way stakeholder communication and input at all stages of the pilot project, including design, implementation, data gathering, and assessment. |

We found that six of the 14 pilot programs provided two-way communication with stakeholders and eight of the 14 pilot programs partially followed this leading practice. Often, the USPTO publishes updates on the progress of pilot programs on the agency’s website. For example, the agency used several forms of communication to receive feedback and provide updates for the First-Time Filer Expedited Examination Pilot Program, such as emails to stakeholders and biweekly reports. |

Source: GAO analysis of USPTO pilot questionnaire responses. | GAO‑25‑107218

Note: The results of our analysis were determined by the questionnaire responses and supporting documentation sent to us by USPTO officials. We did not conduct an in-depth review of each pilot program.

By not consistently following leading practices for pilot programs, the USPTO is missing opportunities to learn valuable information that could inform future pilot design and implementation, as well as which pilot programs should be expanded. Prior GAO work has shown that designing pilot programs in alignment with leading practices increases an agency’s ability to evaluate the pilot program’s outcomes. We found that two of the 14 pilot programs met all five leading practices for effective pilot design. Appendix IV shows the full results of our assessment by pilot program.

Beyond inconsistent application of the leading practices for pilot programs, we also found inconsistencies in other elements of pilot program implementation. Some of the USPTO’s pilot programs have had their end dates extended. For example, the USPTO started the Complex Work Unit pilot program in 2005, and the pilot program was still active at the time of our review.[42] We found that the agency does not have records of the data gathered or the evaluation procedures for this pilot program. USPTO officials told us they are missing several records for the pilot program because all the officials that started the pilot program are no longer at the agency.

Driving these inconsistencies is the USPTO’s lack of a formalized approach for the creation and oversight of pilot programs. According to USPTO officials, pilot programs are generally led by an Assistant Commissioner and supervised by an assigned Deputy Commissioner. However, the agency has not taken steps to formalize and document these roles or the process for pilot program creation. A formalized and documented process could also promote the use of leading practices for pilot programs. According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should document its responsibility for an operational process’s objectives and related risks, implementation, and operating effectiveness.[43] In the absence of a formalized structure, the USPTO’s pilot programs have not consistently implemented leading practices for effective pilot program design. Therefore, the agency is missing opportunities for lessons learned from its pilot programs and information that could inform decisions about the future of pilot programs.

The USPTO’s Quality Assessment Processes Do Not Ensure the Validity of Patent Quality Metrics and Data

We found several methodological limitations with the USPTO’s supervisory quality review process that can affect the accuracy of the data produced by these reviews. Additionally, we found that the quality control processes OPQA uses when changing completed quality reviews lack transparency and rigor.

Data from Supervisory Quality Reviews Likely Overstate Actual Adherence to Patent Requirements

Supervisory quality reviews are the primary mechanism that the USPTO uses to measure patent examination quality for individual examiners. Supervisors conduct the reviews and assess whether an examiner made any clear errors in deciding whether to grant a patent. The USPTO uses data from supervisory reviews to understand the extent to which examiners adhere to quality standards and to determine individual examiner performance ratings for quality. We identified several aspects of supervisory quality reviews of examiner’s work that likely affect the reliability of examiner performance data for quality and could contribute to an environment that does not encourage high-quality examination. In our review of supervisory review practices and USPTO data, we observed the following issues.

Supervisory quality reviews are not required to use sound criteria for selection. Relevant USPTO guidance states that “any final form work product may be reviewed, regardless of how it is selected or comes to the [s]upervisor’s attention.” This guidance does not establish any sound criteria for selection, such as random or risk-based selection. One focus group participant told us their supervisor allows them to choose which office actions the examiner would like reviewed, so the examiner makes sure to do a good job on the actions they plan to submit to their supervisor for review. The current lack of criteria for selection may limit the ability of the supervisory reviews to provide an accurate reflection of examination quality, as the actions selected for review may not be representative of an examiners typical work. A USPTO official told us that, while there is no agency-wide requirement for random selection, the USPTO offers tools that interested supervisors can use to facilitate random selection. This official also stated that some individual technology centers or art units have an expectation of random selection for their supervisors.

Supervisors can exclude identified errors from error rate calculation. According to USPTO guidance, when supervisors identify a “clear error” in an examiner’s office action, they have discretion in determining how, if at all, the error factors into the error rate that contributes to the examiner’s quality rating.[44] For example, supervisors can choose to address the error through coaching and mentoring, rather than including the error in the examiner’s error rate calculation, if they deem it is the most effective approach for improving the examiner’s performance. A USPTO official stated there is not a set process for making this determination, and that supervisors have discretion to determine how they want to address errors. USPTO officials we met with who have experience conducting supervisory quality reviews stated they avoid including an identified clear error in an examiner’s quality rating unless the examiner has repeatedly made the same type of error. Instead, they will typically take a coaching approach the first time or two an examiner makes an error. One official noted that the goal of supervisory reviews is to help examiners improve their examination skills, and that charging an error for every potential issue can sometimes be more discouraging than helpful. Given that supervisors can choose not to include all identified errors in the examiner error rate calculation, examiner performance data for quality may overstate actual examiner performance.

Error rates count multiple errors as a single error. The USPTO’s Performance Appraisal Plan for examiners states “when multiple errors are charged in a single [o]ffice action…a single error will be used in the computation of the error rate.” Whether an office action has five clear errors or one clear error, it will be counted as one error when the error rate is calculated. Because error rate calculations treat a single office action with many errors the same as work with one error, error rate metrics can understate the extent of examiner errors.

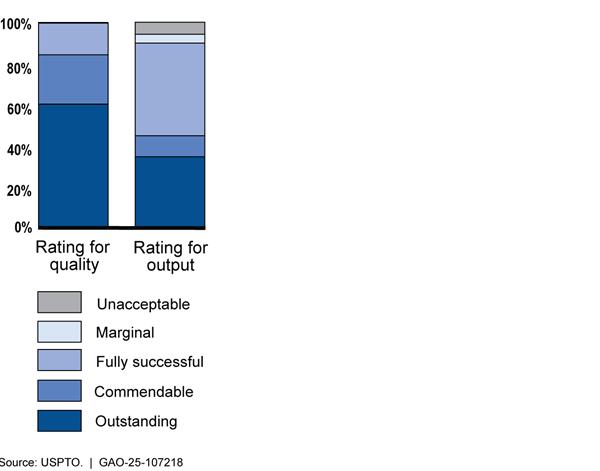

Examiners can receive a clear error in all reviews and still get a passing quality rating. According to USPTO guidance, supervisors are expected to conduct at least two quality reviews each quarter for each examiner they supervise, for a total of at least eight annual supervisory quality reviews for each examiner.[45] To receive a “fully successful” or better performance rating for quality, an examiner’s error rate cannot exceed 6.49 percent, according to the USPTO Performance Appraisal Plan for patent examiners. If an examiner receives a clear error for all eight of their required supervisory quality reviews and completed the average number of office actions in a year (about 140), their error rate would be calculated as 5.7 percent.[46] Thus, a primary examiner who completes the average number of office actions in a year can receive a clear error in all eight of their required supervisory quality reviews and still receive a “fully successful” or better performance rating for quality (see fig. 4). For an examiner’s error rate to exceed 6.49 percent, and thus receive a “marginal” or worse rating for quality on their performance rating, a supervisor would need to conduct ten quality reviews for that examiner and charge the examiner with a clear error in all ten reviews.[47] This is unlikely to occur given that, in our review of USPTO data, we found that less than 20 percent of examiners received ten or more total reviews each fiscal year between 2021 through 2023.

Figure 4: Effect of Number of Supervisory Quality Reviews with Clear Errors on Patent Examiner Error

Rate

Notes: Error rate percentages assume an examiner has completed 140 office actions, which is the average number of office actions each examiner completed in fiscal years 2022 and 2023.

“Examiner passes” indicates that the examiner would

receive a “Fully Successful” or better rating for quality on their performance

assessment. “Examiner fails” indicates that the examiner would receive a “Marginal”

or worse rating for quality on their performance assessment.

Examiner quality ratings do not align with rating standards. USPTO data we reviewed showed that about 84 percent of examiners received a quality rating of “outstanding” or “commendable” in fiscal year 2023. (see fig. 5) According to Commerce Department guidance on performance ratings, an “outstanding” performance rating indicates “rare, high-quality performance” that “rarely leave[s] room for improvement” and a “commendable” rating indicates “a level of unusually good performance.” A patent expert we met with suggested that because a large share of examiners is receiving performance scores that indicate unusually good performance or rare, high-quality performance, it raises questions about whether this performance is truly unusual or rare. This is a long-standing issue that was raised by Commerce OIG, which described similar concerns with the distribution of quality ratings in a 2015 report.[48] However, when the USPTO updated the examiner Performance Appraisal Plan in fiscal year 2022, it raised the error rate thresholds for an outstanding or commendable rating, making it easier for examiners to achieve those quality ratings.

The USPTO’s supervisory quality review process does not align with internal control standards, which, in turn, can limit the usefulness of the data produced by these reviews. Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government calls on agencies to use quality information to achieve their objectives, to ensure data are free from error and bias, and to evaluate both internal and external sources of data for reliability.[49] Currently, the USPTO’s guidance to supervisors regarding quality reviews provides them with significant latitude in how they carry out their reviews, but the lack of controls for these reviews likely produces performance data that overstate examiners’ actual adherence to quality standards and may not encourage examiners to consistently perform high-quality examination. Additionally, current USPTO processes for counting errors identified in supervisory quality reviews and calculating examiner error rates may artificially inflate measures of quality. Because the USPTO uses examination quality data to understand the extent to which examiners adhere to quality standards, it is important the agency takes steps to help ensure these data are valid and free from error and bias.

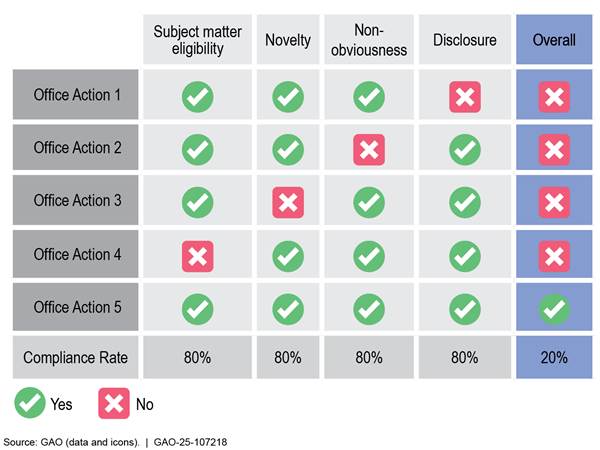

OPQA Processes When Changing Quality Review Outcomes Lack Transparency and Rigor

In addition to the supervisory quality reviews, which the USPTO uses to provide examination quality data at the individual examiner level, OPQA conducts random quality reviews to provide examination quality data at the agency and technology center levels. These quality reviews are conducted by OPQA reviewers, who assess randomly sampled office actions for compliance with patentability standards.[50] Each fiscal year, OPQA reviews approximately 12,000 completed office actions, which is about 1 percent of the total yearly volume of office actions. OPQA reviewers determine an office action to be compliant if it meets all patentability standards and noncompliant if it fails to meet at least one patentability standard.[51] The USPTO considers the metrics produced by OPQA’s random quality reviews to be the agency’s primary patent quality metrics regarding compliance with patentability requirements. The metrics produced from this data are reported to Congress and the public.

After the formal OPQA random quality review process has concluded, OPQA conducts data integrity reviews on some of the completed random quality reviews.[52] OPQA management uses these data integrity reviews to change review outcomes if they determine an OPQA reviewer incorrectly applied a quality standard.[53] OPQA management does this to help ensure quality standards are being consistently applied by OPQA reviewers. Changes to random quality reviews are tracked within a USPTO data system called the review log. However, we found limitations with the transparency and rigor of the OPQA data integrity review process that can hinder OPQA’s ability to use the review process to meet its stated goals of ensuring the “integrity and accuracy of OPQA-generated data” and providing “feedback to the [OPQA supervisor] who oversaw the review.”

Lack of Transparency

A lack of transparency in review records complicated our efforts to understand OPQA’s process for changing the outcomes of random quality reviews after conducting data integrity reviews. In our review of the USPTO’s quality review data, we identified 41 completed OPQA random quality reviews that were reopened by OPQA and had their outcome changed between fiscal year 2021 and the end of May 2024.[54] The vast majority of these changes—39 of the 41—-resulted in a noncompliant review being changed to a compliant review, which improves the USPTO’s quality metrics.