COAST GUARD

Actions Needed to Address Cutter Maintenance and Workforce Challenges

Report to the

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure,

House of Representatives

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107222. For more information, contact Heather MacLeod at macleodh@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107222, a report to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, House of Representatives

Actions Needed to Address Cutter Maintenance and Workforce Challenges

Why GAO Did This Study

The Coast Guard, a multi-mission military service within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), is responsible for ensuring the safety, security, and stewardship of more than 100,000 miles of U.S. coastline and inland waterways. It relies heavily on its cutter fleet to meet these mission demands. In 2012, GAO reported that the Coast Guard’s legacy cutters were approaching, or had exceeded, their expected service lives and that their physical condition was generally poor.

GAO was asked to review how the cutter fleet has changed since 2012. This report examines, among other things, the Coast Guard’s (1) challenges in operating and maintaining its cutter fleet, and (2) the extent it has determined its cutter-related workforce needs.

GAO analyzed available Coast Guard documentation and data for the period 2012-2024 on types of cutters, cutter availability, and cutter usage time. GAO also conducted site visits to observe facility operations and interviewed Coast Guard officials, including maintenance officials and cutter crews representing a mix of cutter types and geographic locations.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making five recommendations, including that the Coast Guard collect and assess data on (1) the impact of deferred maintenance on cutter equipment failures and which parts and systems are or will become obsolete; and (2) staff availability for the cutter workforce. DHS agreed with four of the recommendations but did not agree to analyze staff availability data. GAO continues to believe this would help inform personnel assignments.

What GAO Found

The U.S. Coast Guard faces increasing challenges operating and maintaining its fleet of 241 cutters—vessels 65 feet or greater in length with accommodations for crew to live on board. Since fiscal year 2019, the cutter fleet’s availability to conduct missions generally declined due, in part, to increasing equipment failures. Across the cutter fleet, the number of instances of serious cutter maintenance issues increased by 21 percent from 3,134 in fiscal year 2018 to 3,782 in fiscal year 2023. As a result, more cutters are operating in a degraded state and at an increased risk of further maintenance issues.

Coast Guard Cutter Penobscot Bay at a Major Repair Facility in Baltimore, Maryland

Two maintenance challenges that are particularly impactful are increasing deferred maintenance and delays in obtaining obsolete parts. In fiscal year 2024, the Coast Guard deferred $179 million in cutter maintenance, almost nine times the amount deferred in 2019 (based on inflation-adjusted values). Due to delays in receiving critical parts needed for repairs, the Coast Guard cannibalizes cutters by moving working parts between cutters. The Coast Guard lacks complete information to address the impacts of these challenges. Systematically collecting data on, and assessing, deferred maintenance and parts obsolescence could enable the Coast Guard to better prioritize projects and funding.

The Coast Guard has not fully addressed the impacts of personnel shortages that are a major challenge to operating and maintaining the cutter fleet. Cutter crew and support positions are short staffed, with vacancy rates increasing from about 5 percent in fiscal year 2017 to about 13 percent in fiscal year 2024. Cutter personnel workload has increased to meet mission demands and cutters often deploy without a full crew, which the Coast Guard does not account for in its staffing data. Regularly collecting and assessing data on staff availability could help ensure the Coast Guard is fully considering the workload faced by cutter crews and support personnel when making decisions on personnel assignments.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

SFLC |

Surface Forces Logistics Center |

|

|

|

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The U.S. Coast Guard (Coast Guard), a multi-mission maritime military service within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), is responsible for ensuring the safety, security, and stewardship of more than 100,000 miles of U.S. coastline and inland waterways.[1] It is the principal federal agency for a variety of missions, including serving as a first responder for maritime search and rescue operations and conducting maritime drug and migrant interdiction. Additionally, the Coast Guard maintains more than 50,000 buoys, beacons, and other aids to mark channels and denote hazards.[2] To fulfill these mission demands, the service relies heavily on its cutter fleet—defined as vessels 65 feet or greater in length and having adequate accommodations for crew to live on board.

In 2012, we reported that the physical condition of the Coast Guard’s legacy cutters was generally poor.[3] We found that the cutter fleet’s degraded condition negatively affected the Coast Guard’s operational capacity to meet mission requirements, and key actions taken to improve these ships’ condition had fallen short of goals.[4] More recently, we also reported in multiple reports and congressional testimony statements that newer replacement cutters have experienced significant delays in the projected delivery dates and increased acquisition program costs, and that increased depot-level maintenance[5] is affecting cutters’ operational availability.[6]

The Coast Guard has reported that its top priority is readiness, for both its assets and its workforce. The rising frequency of natural disasters, growth in commercial maritime activity, and increasing tensions in the maritime domain due to maritime irregular migration, illegal fishing, transnational organized crime, and strategic power competition has increased demands on its longstanding mission responsibilities. Moreover, in October 2024 the Coast Guard reported that, as these mission demands grow, the service is experiencing a historic workforce shortage and shortfalls in maintenance funding that impact the material readiness of Coast Guard assets.[7] The effects of these additional responsibilities and increased demands underscores the importance for the Coast Guard to regularly assess its resource needs—including for the cutter fleet and the workforce to operate and maintain them—in order to effectively carry out its missions.

You asked us to review how the operational capabilities and capacities of the cutter fleet have changed since 2012. This report examines (1) how the Coast Guard cutter fleet changed during 2012 through 2024, (2) the challenges the Coast Guard faces in operating and maintaining the cutter fleet, and (3) the extent to which the Coast Guard has filled its cutter workforce positions and determined its cutter-related workforce needs.

To address all of our objectives, we interviewed officials representing both Coast Guard area commands and all nine districts about operating and maintaining the cutters under their command, including information on cutter fleet changes during 2012 through 2024, operational targets, cutter challenges, workforce needs, and personnel shortages.[8] We also conducted site visits to Coast Guard offices located in three of nine districts to tour eight Coast Guard cutters and interview cutter crews representing six different cutter types.[9] We selected these three districts to represent a mix of Coast Guard cutter types as well as geographic location. While the information obtained from our interviews with cutter crews in these locations is not generalizable to all cutter types or operating environments, it provided valuable insights about challenges the Coast Guard faces in operating and maintaining cutters. We also interviewed Coast Guard headquarters officials and visited the Coast Guard Yard—the Coast Guard’s sole shipbuilding and major repair facility located in Baltimore, Maryland—to observe facility operations and interview Coast Guard officials about cutter availability, maintenance and repairs, and related challenges.

To examine how the Coast Guard cutter fleet changed, we analyzed cutter data obtained from the annual Register of Cutters of the U.S. Coast Guard for the period 2012 through 2025.[10] We interviewed relevant agency officials, reviewed related documentation, and assessed the data for missing data and obvious errors in accuracy and completeness to determine their reliability. Based on these steps, we determined these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of presenting data on the numbers and types of cutters over time.

To identify the challenges the Coast Guard faces in operating and maintaining the cutter fleet, we determined the extent to which the Coast Guard met cutter operational availability and usage time targets by analyzing data from the Coast Guard’s Asset Logistics Management Information System and Electronic Asset Logbook system during fiscal years 2012 through 2024.[11] We also reviewed Coast Guard guidance, instructions, and manuals to identify the applicable cutter availability metrics and usage time targets for each cutter type over our review period.[12] We interviewed relevant agency officials, reviewed related documentation, and assessed the data for missing data and obvious errors in accuracy and completeness to determine the reliability. Based on these steps, we determined these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of presenting cutter operational availability rates and cutter usage data over time. However, we found data on operational availability rates for multiple cutter types during fiscal years 2012 through 2015 to be missing.[13] For this reason, we limited our analysis of cutter operational availability in this report to fiscal years 2016 through 2024.[14]

To further identify the challenges the Coast Guard faces in operating and maintaining the cutter fleet, we analyzed available Coast Guard data on cutter maintenance and associated costs. This included data on cutter planned maintenance, unplanned maintenance issues, key mission degraders, deferred maintenance, and related costs during fiscal years 2018 through 2024, the time period for which the Coast Guard was able to provide data. To assess the reliability of these data, we obtained written responses from relevant agency officials, reviewed related documentation, and assessed the data for missing data and obvious errors in accuracy and completeness. Based on these steps, we determined these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of presenting cutter maintenance-related challenges and costs.

We also analyzed Coast Guard documentation on cutter planning and performance for both Coast Guard area commands and all nine Coast Guard districts; Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Boards;[15] and the Surface Forces Logistic Center’s (SFLC’s) Funding Shortfalls and Fleet Impacts Memorandums.[16] We assessed the completeness of these data and the Coast Guard’s process for collecting and analyzing them to address identified cutter challenges against Coast Guard guidance and policy.[17] We also assessed these data and the Coast Guard’s process against GAO-identified leading practices for managing deferred maintenance backlogs.[18]

To assess the extent to which the Coast Guard has filled its cutter workforce positions and determined its cutter-related workforce needs, we analyzed Coast Guard data on cutter crew and support positions during fiscal years 2017 through 2024, the time period for which the Coast Guard was able to provide data.[19] To assess the reliability of the data, we obtained written responses from relevant agency officials about their practices for maintaining the data, reviewed related documentation, and assessed the data for missing data and obvious errors in accuracy and completeness. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of reporting the status of Coast Guard cutter-related positions (filled or vacant). We assessed these Coast Guard data on its cutter workforce and plans to address related workforce challenges against the Coast Guard’s Framework for Strategic Mission Management, Enterprise Risk Stewardship, and Internal Control.[20] Appendix I provides additional details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of Coast Guard Missions and Cutters

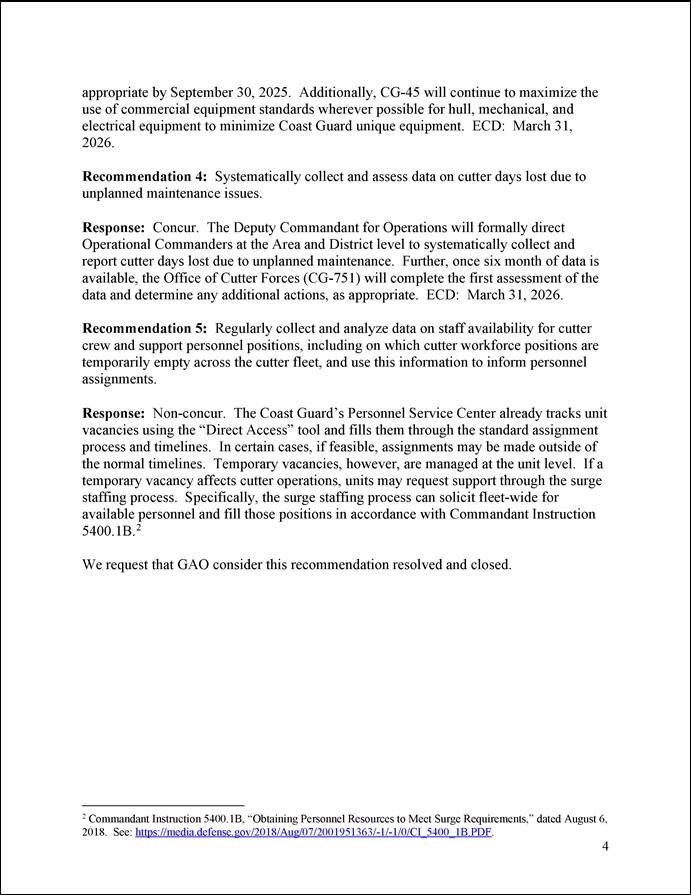

The Coast Guard is responsible for conducting 11 statutory missions defined by the Homeland Security Act of 2002.[21] These missions are statutorily divided into homeland security missions and non-homeland security missions, as shown in figure 1 below.

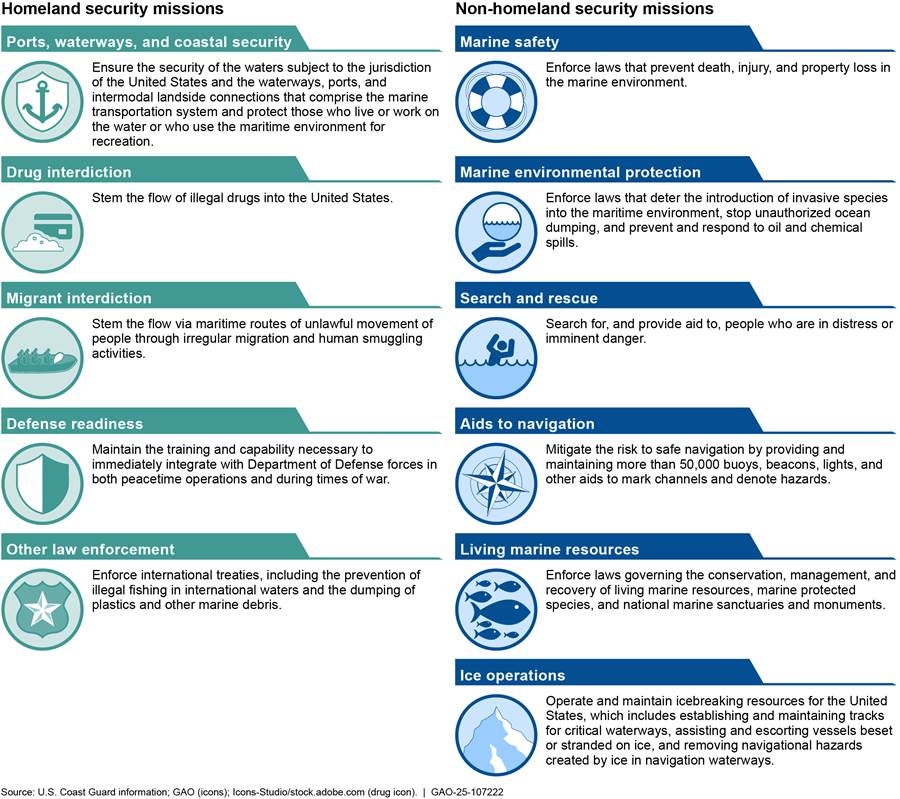

To fulfill its diverse missions, the Coast Guard operates aircraft, boats, and cutters. The Coast Guard’s cutter fleet consists of major cutters—cutters that can carry multiple small boat types—and non-major cutters.[22] Major cutters are typically larger, can remain at sea for longer, and have larger crews compared to non-major cutters. During fiscal years 2012 through 2024, the fleet overall spent the most operational time supporting the living marine resources mission, such as boarding vessels to enforce federal fisheries law. See figure 2 for the total hours the Coast Guard deployed the cutter fleet across its missions during fiscal years 2012 through 2024.

The Coast Guard stations its cutters throughout the United States and abroad. These cutters are equipped with a variety of capabilities to support the Coast Guard’s missions—such as automated weapon systems, the ability to launch rotary wing aircraft and small boats, or hulls and systems designed to improve icebreaking capabilities. According to the Coast Guard, all cutters are multi-mission, although different cutter types are designed and primarily used to support some of the Coast Guard’s statutory missions more than others. For example, some cutters operating in the open sea are capable of sustained speeds of up to 28 knots (about 30 miles per hour) and can launch small boats to interdict vessels containing drugs or migrants. Other cutters operating in coastal waterways use cranes to maintain buoys marking shipping lanes in support of the aids to navigation mission. See figure 3 for examples of Coast Guard cutters conducting operations for its different missions.

Coast Guard Cutter Modernization Efforts

To address the increasing age and deteriorating physical condition of the Coast Guard’s assets, the service began a recapitalization effort in the late 1990s to modernize a significant portion of its surface and aviation fleets by rebuilding or replacing assets. As part of this effort, the Coast Guard has acquired or is in the process of acquiring newer, comparatively more modernized cutters, to include Fast Response Cutters, National Security Cutters,[23] Offshore Patrol Cutters, Arctic Security Cutters (i.e. medium polar icebreakers), Polar Security Cutters (i.e., heavy icebreakers),[24] and Waterways Commerce Cutters. These newer cutters are intended to replace certain aging legacy cutters that we previously reported have exceeded their expected service lives, while the conditions of these cutters continue to decline.[25]

However, as mentioned earlier, we also previously reported that some of these newer replacement cutters—specifically, the Offshore Patrol Cutters and Polar Security Cutters—have experienced significant delays in the projected delivery dates and increased acquisition program costs.[26] We found that these delays in delivery of the replacement cutters have required the Coast Guard to extend the service life of some legacy cutters to meet mission demands, resulting in additional increases in maintenance costs for the cutter fleet. For example, in June 2023 we reported on the status of ongoing challenges with the Coast Guard’s management of its Offshore Patrol Cutter acquisition program and the service’s plans for the aging fleet of legacy cutters that the Offshore Patrol Cutters are intended to replace.[27] In July 2023 we reported on similar challenges the Coast Guard faces with unreliable schedule and cost estimates associated with the acquisition of Polar Security Cutters and efforts underway to maintain and extend the life of the service’s sole remaining, almost 50-year-old heavy polar icebreaker.[28]

Cutter Fleet Size Remained Stable, But Some Aging Cutters Were Replaced Due to Modernization Efforts

During 2012 through 2024, the overall size of the cutter fleet remained relatively consistent as the Coast Guard acquired newer, replacement cutters at generally the same rate that the service retired others.[29] As of January 2025, the Coast Guard operates a total of 241 cutters consisting of 40 major cutters and 201 non-major cutters. The average age of the cutters varies widely among different types of cutters. Some types of cutters have been in service for decades and are still being deployed well after their designed service lives.

The Coast Guard Has Replaced or Plans to Replace All 40 Major Cutters

During 2012 through 2024, the Coast Guard commissioned eight newer major cutters and decommissioned 10 older major cutters, with acquisition plans underway to replace an additional 30 major cutters. The Coast Guard’s fleet of major cutters includes the 418-foot National Security Cutters, which are among the largest in the fleet, have a cruising range of 12,000 nautical miles, and are designed to remain at sea for 60 days. Additionally, the Coast Guard’s major cutter fleet also includes three types of Medium Endurance Cutters with varying capabilities and three polar icebreakers (only two of which are currently operational).[30] See figure 4 for more information on the Coast Guard’s major cutters as of January 2025.

Note: Major cutters also include the 295-foot Coast Guard Cutter Eagle. The Coast Guard Cutter Eagle is primarily used to train cadets at the Coast Guard Academy and to perform a public relations role for the Coast Guard and the United States, such as making calls at foreign ports as a goodwill ambassador.

aOnly one of the two 399-foot icebreakers in the Coast Guard cutter fleet—the Polar Star—is currently operational. The second 399-foot icebreaker—the Polar Sea—has been inactive since 2010, when it experienced a catastrophic engine failure.

bThe 282-foot Medium Endurance Cutter commissioned as a Coast Guard cutter 1999. The ship was originally commissioned by the U.S. Navy in 1971.

cWe included all cutters that have not been formally decommissioned in the figure above. Due to staffing shortages, the Coast Guard removed four 210-foot Medium Endurance Cutters from service in fiscal year 2024 in advance of the cutters being decommissioned.

|

A Piece of History: U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Eagle

Coast Guard Cutter Eagle is a 295-ft training cutter used to provide at-sea experience to cadets at the Coast Guard Academy. The ship was built in 1936 in Germany and originally commissioned as the Horst Wessel. It was later taken by the United States from Germany as a war prize after World War II. Coast Guard Eagle is the American military’s only active-duty square-rigged ship. A permanent crew of around eight officers and 50 enlisted personnel maintain the ship year-round, and up to 150 cadets or officer candidates can be aboard at a time. Source: U.S. Coast Guard information; U.S. Coast Guard photo by PO3 Carmen Caver. | GAO‑25‑107222 |

As part of its recapitalization effort, the Coast Guard has replaced or plans to replace all 40 of its major cutters, as follows:

· As of January 2025, the Coast Guard has completely replaced its fleet of 12 High Endurance Cutters with 10 newer, more capable National Security Cutters.[31] For example, National Security Cutters can remain at sea without reprovisioning for 15 more days than High Endurance Cutters.[32]

· The Coast Guard is in the process of acquiring 25 Offshore Patrol Cutters, which are intended to replace the 26 Medium Endurance Cutters in the cutter fleet as of January 2025. We previously reported that the Coast Guard considers the Offshore Patrol Cutter acquisition its highest investment priority and largest acquisition program.[33] However, we also reported that the Offshore Patrol Cutter acquisition program has faced and is continuing to face significant schedule delays and cost increases. Specifically, we found that the delays in Offshore Patrol Cutter deliveries will likely exacerbate an operational capability and capacity gap due to the risk of the Medium Endurance Cutters failing before they are replaced.[34] To address the potential gap, the Coast Guard started an acquisition program to extend the service life of six of the 270-foot Medium Endurance Cutters, intending to add up to 10 years of service life for each cutter.[35] All 270-foot Medium Endurance Cutters have exceeded their original 30-year service life, with the oldest commissioned in 1983.

· The Coast Guard also plans to acquire three Polar Security Cutters, which are intended to replace two 399-foot polar heavy icebreakers (only one of which is currently operational, Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star).[36] However, as we reported in July 2023, the program experienced design challenges that have caused significant schedule delays.[37] The Coast Guard plans to complete a service life extension program for the Coast Guard Cutter Polar Star in 2025, which is intended to extend service life by 7 to 10 years.[38] In December 2024, the Coast Guard acquired a commercially available polar icebreaker to increase operational presence in the Arctic while Polar Security Cutters are acquired.[39]

· As of March 2025, Coast Guard officials reported they were in the early stages of initiating acquisition programs to replace the Coast Guard Cutter Healy with a medium polar icebreaker and replace the Coast Guard Cutter Eagle with a new training vessel.

Fast Response Cutters Replaced Patrol Boats, but Aging Non-Major Cutter Fleet Remains Mostly Unchanged

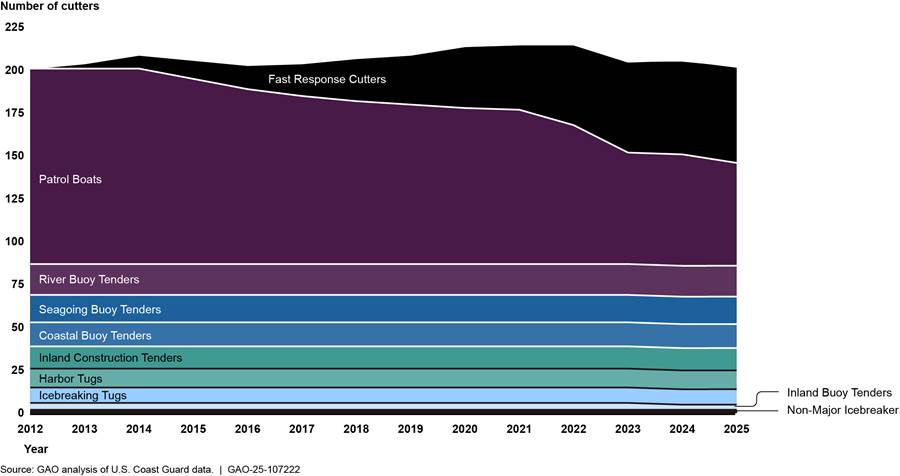

During 2012 through 2024, the Coast Guard commissioned 55 Fast Response Cutters and decommissioned 54 patrol boats in its non-major cutter fleet.[40] The remainder of the Coast Guard’s fleet of 201 non-major cutters generally remained unchanged.[41] According to Coast Guard documents, the 154-foot Fast Response Cutters are considered more capable than the 110-foot Patrol Boats they replaced because they include command and control systems that are interoperable with existing Department of Defense and DHS assets and have a standardized small boat with stern launch capabilities.[42] See figure 5 for an overview of how the Coast Guard’s non-major cutter fleet changed during 2012 through January 2025.

The Coast Guard’s non-major cutters are used for a variety of purposes and have different capacities and capabilities. For example, 225-foot seagoing buoy tenders have a personnel allowance of 48 crew members and can remain at sea unreplenished for 21 days. In comparison, the 87-foot patrol boat has a much smaller personnel allowance of 10 crew members and can remain at sea for 3 days. The various cutter types in the Coast Guard’s non-major cutter fleet as of January 2025 are described in additional detail below.

Non-major Icebreakers, Patrol Craft, Harbor Tugs

In addition to Fast Response Cutters, the Coast Guard’s non-major cutter fleet includes a 240-foot non-major icebreaker, 140-foot icebreaking tugboats, 110- and 87-foot patrol boats, and 65-foot harbor tugboats. These non-major cutters conduct a variety of Coast Guard missions to include migrant interdiction, living marine resources, ice operations, and maintaining aids to navigation. See figure 6 for more information on these non-major cutters as of January 2025.

Buoy Tenders and Construction Tenders

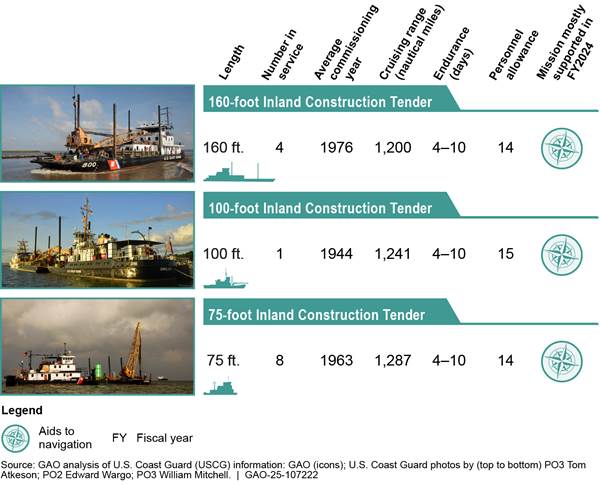

In addition to the above, the Coast Guard operates buoy tenders and construction tenders as part of its non-major cutter fleet, almost all of which have not changed since 2012.[43] These non-major cutters are primarily used to build and maintain maritime aids to navigation, such as

|

A Piece of History: U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Smilax, the “Queen of the Fleet”

Coast Guard Cutter Smilax is a 100-ft inland construction tender, commissioned in 1944, that maintains aids to navigation along the marine transportation system in coastal North Carolina. Regarded as the “Queen of the Fleet,” this title reflects Smilax's status as the oldest cutter still actively serving and is symbolized by its gold hull number. The Smilax celebrated its 80th anniversary in 2024, and the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in 2025. Coast Guard Cutter Smilax and her sister ship, Coast Guard Cutter Bluebell commissioned in 1945, have been in continuous commission since prior to the end of World War II. Source: U.S. Coast Guard information; U.S. Coast Guard courtesy photo. | GAO-25-107222 |

buoys or lighthouses. The Coast Guard did not commission any buoy or construction tenders during our review period and these cutters are among the oldest in the fleet. Specifically, as of January 2025, the average ages of Coast Guard’s fleet of buoy and construction tenders range from approximately 25 years to 81 years. Notably, the average age of the Coast Guard’s river and inland buoy tenders is 59 years and the oldest cutter in the fleet—an inland construction tender—is 81. See figures 7 and 8 for more information on the Coast Guard’s fleet of buoy and construction tenders as of January 2025.

As we have reported previously, the Coast Guard is in the early stages of acquiring Waterways Commerce Cutters, which are intended to replace the service’s legacy fleet of aging buoy and construction tenders.[44] The primary mission for the Waterways Commerce Cutters will be to establish, maintain, and operate aids to navigation on the western rivers and inland waterways.

The Coast Guard Lacks Complete Information to Address the Impacts of Increasing Cutter Maintenance Challenges

The Coast Guard Faces Increasing Cutter Maintenance Challenges While Cutter Availability Is Decreasing

The Coast Guard is experiencing increasing cutter maintenance challenges that, according to most Coast Guard officials we spoke with, are adversely affecting the availability and capacity of the cutter fleet to conduct operations. Specifically, officials from all nine Coast Guard districts reported at least one major challenge related to cutter maintenance.[45] Of those, officials from seven Coast Guard districts told us that unplanned maintenance (such as repairs or dry docks) due to equipment failures have increased and negatively affected their ability to meet mission needs.[46] For example, officials from three districts told us that equipment failures and the resulting unplanned maintenance has led to cutters missing patrol obligations.

Coast Guard operational reporting documents we reviewed provided additional examples of the impact of unplanned maintenance on cutter missions. For example, in the first half of fiscal year 2024, the Pacific Area Command lost at least 50 days of cutter operational availability due to unplanned maintenance for its National Security Cutters. Similarly, Coast Guard operational reporting documents also state that unplanned maintenance, among other things, has significantly reduced the capacity of Medium Endurance Cutters to conduct missions for the Atlantic Area Command.

Analysis of Coast Guard maintenance data also shows increasing cutter maintenance challenges, including the following:

· Across the cutter fleet, the number of instances of the most frequently occurring serious cutter maintenance issues (that could not be resolved by the cutter crew) increased by approximately 21 percent during fiscal years 2018 through 2023, according to Coast Guard data. Specifically, there were 3,134 such issues in fiscal year 2018, increasing to 3,782 such issues in fiscal year 2023.[47]

· Across the cutter fleet, the percent of total days a cutter has a maintenance issue that prevents it from meeting all mission requirements, or is partially mission capable, has increased. Specifically, the share of total cutter days cutters were partially mission capable rose from approximately 3 percent (3,164 out of 94,806) in fiscal year 2018 to approximately 8 percent (7,444 out of 90,656) in fiscal year 2024. According to Coast Guard officials, these cutters are operating in a degraded state and are at an increased risk of further maintenance issues.

· The Coast Guard’s expenditures on cutter unplanned maintenance increased by 52 percent from fiscal year 2020 ($31.9 million) to fiscal year 2024 ($48.4 million projected), after adjusting for inflation, according to Coast Guard documentation.[48]

The effects of these cutter maintenance challenges on the capacity of the cutter fleet to meet mission needs are apparent in our analysis of Coast Guard data on cutter operational availability and usage time targets, discussed below.[49]

Operational availability is decreasing. Coast Guard cutter operational availability is a metric that focuses on the percentage of time cutters are operational and do not have equipment failures that prevent them from being available to conduct missions. Based on our comparison of Coast Guard cutter operational availability targets and actual cutter performance during fiscal years 2016 through 2024, we found the extent to which major cutters and non-major cutters met this target varied by cutter type and generally declined in recent years across the entire cutter fleet.[50] Specifically, the operational availability of 20 types of cutters in the Coast Guard cutter fleet declined during fiscal years 2020 through 2024 when compared to their performance during fiscal years 2016 through 2019.[51] For example:

· During fiscal years 2016 through 2019, National Security Cutters—the Coast Guard’s newest type of major cutter—averaged approximately 94 percent operational availability, exceeding the 90 percent target set by the Coast Guard. However, this average declined during fiscal years 2020 through 2024 to approximately 88 percent.

· While all five types of inland buoy and construction tenders met their 70 percent target for operational availability during fiscal years 2016 through 2019, only three of the five types met their target during fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

· All three types of Medium Endurance Cutters met their 90 percent target for operational availability during fiscal years 2016 through 2019; however, only the 282-foot Medium Endurance Cutter met its target during fiscal years 2020 through 2024. Further, the operational availability of all three types of Medium Endurance Cutters declined during fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

Coast Guard officials identified several maintenance reasons cutters are not meeting operational availability targets.

· Specifically, officials stated that Medium Endurance Cutters have hulls that are beyond their service lives. Hull repairs can take significant time and funding, depending on complexity, scope, or delays in receiving materials, making cutters unavailable to sail.

· Further, officials told us the National Security Cutters take longer to repair due to complexity of the cutter’s systems and how difficult it is to physically access certain components. These challenges limit a technician’s ability to maintain and repair the equipment. For example, the highly integrated systems on National Security Cutters results in the inability to repair single components or systems. Instead, when one component needs repair, multiple systems may also require repair due to system integration, which lengthens the time a cutter is unavailable to sail.

· Other reasons identified by Coast Guard officials included issues with propulsion engine modifications and hull structural stiffening defects on some Fast Response Cutters that needed to be addressed upon delivery (a warranty issue), which limited the amount of time these cutters were available to conduct operations.

In contrast, officials stated that other cutter types such as the coastal, river, and inland tenders remain within targets because they are built simply, are easy for technicians to maintain, and do not operate at the high end of their limits while underway.

Cutters rarely met usage time targets. Coast Guard cutter usage time is a metric that focuses on the amount of time (either in days and/or hours) when a cutter crew or cutter is not docked at homeport or is underway. Based on our comparison of Coast Guard cutter usage targets and actual cutter performance during fiscal years 2012 through 2024, we found that the Coast Guard cutter fleet rarely met usage time targets.[52] Specifically, only one out of six types of major cutters met the annual usage time target more than half of the time during fiscal years 2012 through 2024. Notably, none of the major cutters met their usage time target in fiscal years 2023 and 2024. Similarly, the Coast Guard’s 15 non-major cutter types rarely met their usage targets during fiscal years 2012 through 2024.

Two of the maintenance challenges that are particularly impactful on cutter operations are the Coast Guard’s increasing deferred maintenance on the cutter fleet and delays in obtaining cutter parts impacted by long lead times and parts obsolescence, as discussed below.

Coast Guard is Deferring More Cutter Maintenance

According to the Coast Guard, deferred cutter maintenance is a major problem that negatively impacts the Coast Guard’s ability to meet its missions and is increasing over time.[53] For example, officials told us that deferred cutter maintenance may result in preventable equipment failures that regular maintenance could have avoided. Additionally, while Surface Forces Logistics Center (SFLC) officials told us they prioritize maintaining cutter equipment that, if it fails, could present a safety hazard, deferred cutter maintenance still contributes to an increased risk to people and safety as well as to the Coast Guard’s ability to conduct missions, according to Coast Guard officials.[54] Deferred maintenance also increases cutter maintenance costs as it further compounds pre-existing cutter maintenance budget shortfalls.

Officials from eight of nine districts told us that deferring required maintenance on cutters is one of their major challenges. Further, officials from seven of nine districts stated that deferred cutter maintenance has caused future equipment failures that had to be corrected during unplanned maintenance periods, which affected cutter operations. For example:

· SFLC officials told us they had deferred a maintenance period for a Medium Endurance Cutter due to financial constraints, leading to one of two rudders detaching from the cutter and sinking while the cutter was in port. Officials stated that conducting the needed repairs took several weeks, during which time the cutter was not available to the area command to perform missions.

· Officials from one district told us that a Fast Response Cutter had maintenance deferred on a shaft seal—a device that prevents fluids from leaking from a rotating shaft. The seal then broke, and the cutter was unable to operate for 4 months. Eventually the cutter was repaired with parts provided by the SFLC, but district officials told us that the cutter’s absence put pressure on the remaining cutters to complete missions with one less cutter available.

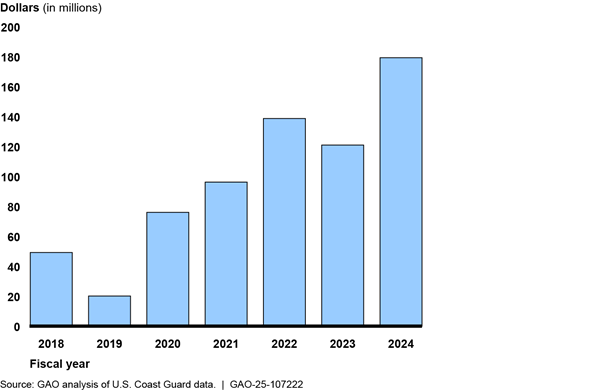

According to Coast Guard data, the amount of deferred cutter fleet maintenance expenditures continues to increase. For example, in fiscal year 2024, the Coast Guard deferred approximately $179 million in cutter maintenance expenditures—representing a 264 percent increase from the approximately $49 million deferred in fiscal year 2018 (values adjusted for inflation).[55] More notably, the amount deferred in fiscal year 2024 was almost nine times larger than the Coast Guard’s low of approximately $20 million in cutter maintenance expenditures deferred in fiscal year 2019 (see fig. 9).

Note: The drop in deferred cutter fleet maintenance expenditures in fiscal year 2019 is attributed to Coast Guard policy decisions to shift from a 2-year inventory stock of spare cutter parts to a 1-year inventory stock. This enabled the Coast Guard to instead use available funds for planned maintenance, according to Coast Guard officials.

The Coast Guard defers maintenance on the cutter fleet due to a lack of sufficient funding necessary to fully account for all cutter maintenance-related costs, including planned cutter maintenance or inventory reorders of cutter parts, according to SFLC officials. Additionally, SFLC officials told us that unplanned maintenance due to equipment failures is generally funded by transferring money from another funded project, which then must be deferred as a result. SFLC officials told us that the practice of managing the growing cutter maintenance budget shortfall by prioritizing some cutter maintenance projects and deferring others to future fiscal years is based on mission requirements, cutter maintenance history, and the demand for Coast Guard services.[56] The increase in the cutter maintenance budget shortfall is therefore caused in part by consistently carrying forward these deferred maintenance projects into the next fiscal year.[57]

According to the Coast Guard, deferred maintenance is a compounding problem that poses a long-term risk to Coast Guard mission execution. For example, officials from multiple Coast Guard operating units told us that delays in maintenance compound smaller problems into larger and more expensive problems in the future. Further, according to Coast Guard operational reporting documents, deferring maintenance in the short term means that the eventual repairs will take longer to complete. SFLC officials also told us that rolling overdue maintenance into the next fiscal year increases the required amount of maintenance. Engineers also will have less time to perform scheduled preventative maintenance if they must address an increasing number of unplanned cutter maintenance issues.

The Coast Guard has acknowledged that deferred maintenance is a major challenge that negatively impacts the availability and capacity of the cutter fleet to meet mission needs. However, the Coast Guard does not systematically collect or assess data on instances where previously deferred maintenance may have caused cutter equipment failures nor, as a result, incorporated these data into any strategies to mitigate the impact of deferred maintenance. SFLC officials stated that the Coast Guard does periodically collect and convey individual examples to Coast Guard leadership of the instances where previously deferred maintenance may have caused cutter equipment failures. SFLC officials added that it can be difficult to determine whether previously deferred maintenance caused an equipment failure since the failure may occur one or two years after the deferral. SFLC officials stated they instead prefer to focus on completing the cutter maintenance they can conduct, and they believe that conveying anecdotal examples of equipment failures that may have been caused by deferred maintenance is sufficient.

The Coast Guard’s Operational Posture 2024 document states that the Coast Guard will allocate finite resources as informed by capacity, readiness, and capability toward the most beneficial outcomes.[58] Coast Guard’s Framework for Strategic Mission Management, Enterprise Risk Stewardship, and Internal Control states that management should collect and use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[59] Furthermore, we have previously identified leading practices for managing deferred maintenance backlogs, which states that, among other things, agencies should employ models for predicting the outcome of maintenance investments, analyzing tradeoffs, and optimizing among competing investments.[60] By systematically collecting and assessing data on instances where previously deferred maintenance may have caused equipment failures, the Coast Guard can better identify the effects and potential trade-offs of deferring maintenance on cutters as demand for Coast Guard services continues to change. Further, developing mitigation strategies, as appropriate, based on this information would allow the Coast Guard to better address the effects of deferred maintenance and use its finite resources more effectively by prioritizing maintenance that is more likely to cause equipment failures.

Cutter Operators Face Delays Obtaining Parts

According to Coast Guard officials from seven of nine districts, another major maintenance challenge that impacts cutter availability is the significant delays that cutter operators face in obtaining cutter parts, many of which are obsolete. These delays can last weeks or even months and can impact both older, legacy cutters and newer cutters. For example, district officials responsible for Great Lakes ice breaking told us that some required parts for icebreakers often have an 8- to-12-week lead time. These officials added that since ice breaking is seasonal and lasts from late December to late March of the following year, if an icebreaker part breaks at the beginning of the ice season, it may be unavailable for missions during that entire winter. Furthermore, officials from six of nine districts stated that many Coast Guard cutters rely on parts and systems that are now obsolete, which makes obtaining the required parts to conduct cutter maintenance more challenging.

According to Coast Guard officials, cutter parts and systems on older cutters can become obsolete because the original manufacturer may be out of business or discontinue support for a product or system, or the part may be no longer manufactured. These issues can complicate and extend the time required to perform otherwise simpler cutter maintenance projects, according to Coast Guard officials. In comparison, officials told us that newer cutters experience obsolescence related to their electronic and computer systems more frequently, such as for a firmware update that could render a cutter’s computer system incompatible with other parts and systems on the cutter. This example of obsolescence specifically affects National Security Cutters the most, according to Coast Guard officials, because they have complex computer and electronic systems that are at greatest risk of obsolescence. Coast Guard officials also stated that technology on National Security Cutters requires updates every 2 to 3 years, much more frequently than the 10-year intervals the Coast Guard originally planned when acquiring the cutters.

The Coast Guard implemented a process to address delays in receiving critical parts needed to operate and deploy a cutter to conduct missions. This process involves cutter operators removing a working part from one cutter and installing it in another cutter that’s determined to have a greater mission need and requires the part to operate. Cutter operators refer to this process as “cannibalization,” but the Coast Guard formally refers to this practice as Controlled Parts Exchanges.[61] While Coast Guard officials told us that cannibalizations are only intended as an emergency solution when replacement cutter parts are not available, cutter operators we spoke with said that cannibalizations have become a normal practice across the cutter fleet. According to Coast Guard data, there were 194 cannibalizations completed across the cutter fleet from February 2022 to September 2024, 145 of which involved National Security Cutters.

Cannibalizations increase the risk that a working part may break as part of the replacement process, according to cutter operators and engineering officials with whom we spoke. Cutter operators also stated that conducting cannibalizations forces cutter maintenance personnel to work additional hours before and after cutter deployments to install or uninstall cutter parts, which damages morale. Furthermore, cannibalization of cutters during their maintenance cycles may also adversely impact the Coast Guard’s future surge capability to respond to emergency events such as mass irregular migration or a natural disaster, according to Coast Guard officials.

Although the Coast Guard uses cannibalization to partially address cutter parts obsolescence, the Coast Guard does not have complete information on cutter-specific obsolescence or on the prevalence and causes of obsolescence across the cutter fleet.

Cutter-specific obsolescence. The Coast Guard does not have complete information on what parts and systems are or will become obsolete for specific cutter types. Coast Guard naval engineering officials told us the policy is to use Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Boards to assess obsolete parts and systems on some specific cutter types, which assists the Coast Guard’s ability to assess overall cutter condition and remaining service life. Coast Guard officials also told us they conduct quarterly maintenance effectiveness reviews of a specific system on a cutter to assess SFLC maintenance processes and how they can be improved, which may include assessing an obsolete system. Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Boards are the primary source of information on the condition and remaining service life of a cutter type, according to Coast Guard documents.[62] However, the Coast Guard has not conducted a Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Board on every type of cutter. According to Coast Guard documentation, SFLC has completed a Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Board for three out of 22 types of cutters since 2020.[63]

The Coast Guard’s Naval Engineering Manual states that one or more cutters of each type shall normally be evaluated by a Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Board 10 years after commissioning and at each 5-year interval thereafter.[64] Evaluating the remaining service or useful life of each cutter type using a Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Board is a fundamental step in the acquisition and modernization planning cycle, according to the Naval Engineering Manual. Coast Guard officials told us they do not conduct a Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Board for all cutters because they do not expect to have the opportunity to address the Board’s findings. They stated it would be a waste of resources to conduct the assessment. However, by not conducting a Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Board for all cutter types at the intervals prescribed in Coast Guard policy, the Coast Guard does not know which systems are or will become obsolete for some cutter types. This means the Coast Guard does not have complete information to proactively address obsolete parts and systems.

Extent of obsolescence across the fleet. In addition to not having information on what parts and systems are or will become obsolete for specific cutter types, the Coast Guard has also not determined the extent of obsolescence across the cutter fleet. Existing methods to assess obsolescence are narrowly focused on specific systems or cutter types. Specifically, Coast Guard officials told us that each Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Board focuses solely on one cutter type, and maintenance effectiveness reviews focus solely on a specific system on cutters. Further, multiple officials across the Coast Guard told us that the Coast Guard does not know the full extent of obsolete parts and systems across the cutter fleet, or the cost to address or mitigate this obsolescence.

Coast Guard officials also told us that decisions made during the acquisitions process do not sufficiently anticipate cutter parts’ obsolescence during a cutter’s service life. For example, cutter engineering officials we spoke with stated that challenges associated with obtaining National Security Cutter parts were caused by acquisition strategies and decisions to design the cutter with increasingly complex technology that could become obsolete and now requires regular updates.[65] We have also previously found that, on Navy ships, acquisition decisions can cause systemic maintenance and sustainment problems, including parts obsolescence issues.[66] For example we reported on 150 significant, class-wide issues on Navy ships that required more sustainment than planned, including systems that were obsolete before or soon after ship delivery.

In 2018, the Coast Guard updated its policy on sustaining assets and made managing parts obsolescence issues a required component of its approach to sustaining assets.[67] Specifically, this policy includes a requirement that program officials develop an approach to managing the loss of manufacturers or suppliers of key items, materials, and software for each cutter type that can cause parts obsolescence. However, this policy focuses on specific asset classes, such as specific types of cutters, and does not include a fleet-wide assessment of obsolescence. Additionally, this policy only applies to cutters built after 2000 and has not been applied to cutters built previously, according to Coast Guard officials.

While acknowledging acquisitions decisions as a potential cause for cutter parts and systems obsolescence, Coast Guard officials told us they do not systematically collect and assess data on which parts and systems across the cutter fleet are or will become obsolete because the issue is complicated. Furthermore, SFLC officials told us they do not have the funding to conduct this tracking. Officials told us that SFLC staff may observe individual parts and systems obsolescence in cutters and may contact parts vendors to discuss the issue to try to address obsolescence of these individual parts and systems. However, SFLC does not have a complete strategy to mitigate the impacts of obsolescence across the cutter fleet because it does not systematically collect and assess data on which parts and systems across the cutter fleet are, or will become, obsolete.

Coast Guard officials also acknowledged that the service would benefit from implementing a systematic way to collect and assess data on parts obsolescence across the cutter fleet, and particularly for computer and electronic components that are at the highest risk of obsolescence.

The Coast Guard’s Operational Posture 2024 document states that Coast Guard will allocate finite resources as informed by capacity, readiness, and capability toward the most beneficial outcomes.[68] Additionally, the Coast Guard’s Framework for Strategic Mission Management, Enterprise Risk Stewardship, and Internal Control states that management should collect and use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[69] By systematically collecting and assessing data on which parts and systems across the cutter fleet are or will become obsolete, the Coast Guard will have more complete information on the full extent and range of obsolescence issues and their associated risks to cutter operations. Using this information, the Coast Guard can more effectively identify which obsolescence issues are the highest priority to address with its finite resources, such as critical computer and electronic components or other obsolescence issues that have the greatest impact on mission execution. Moreover, developing mitigation strategies to better address the effects of obsolescence across the cutter fleet may also enable the Coast Guard to identify potential cost savings, such as buying replacement parts needed by multiple cutters in bulk.

The Coast Guard Does Not Systematically Collect and Assess Data on the Impact of Unplanned Maintenance Issues

The Coast Guard does not have complete information to fully understand the impact of unplanned maintenance issues on cutter operations. Specifically, the Coast Guard does not systematically track the mission time lost when a cutter cannot accomplish scheduled, required tasks due to unplanned maintenance issues such as equipment failures. According to SFLC officials, if a cutter that is scheduled to be underway is not available due to unplanned maintenance issues, it has a bigger impact on the Coast Guard’s ability to meet mission needs than if the issue occurs when that cutter is scheduled to be in port.

SFLC officials told us that the Coast Guard does not systematically track service-wide data on the impact of unplanned maintenance issues on scheduled cutter days because it collects and manages key data separately. Specifically, officials stated that while SFLC uses a computer system to track whether cutters are available to conduct missions, cutter operational commanders in the field are responsible for cutter scheduling and separately use spreadsheets to plan and track scheduled cutter days.[70] SFLC officials told us this makes it difficult to compare actual cutter availability to planned cutter schedules to identify cutter days lost due to unplanned maintenance issues.

However, officials from five of the nine districts told us they already independently track this information by combining cutter scheduling and unplanned maintenance data to track how unscheduled maintenance affects the district’s ability to meet operational targets. For example, according to operational reporting documents, unscheduled maintenance contributed to one district losing at least 594 cutter days in fiscal year 2024.

The Coast Guard’s Framework for Strategic Mission Management, Enterprise Risk Stewardship, and Internal Control states that management should collect and use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[71] By systematically collecting and assessing service-wide data on cutter days lost due to unplanned maintenance issues, as some districts already do, the Coast Guard could better measure and communicate the impact of increasing maintenance issues on the Coast Guard’s ability to meet mission requirements.

The Coast Guard Has Not Fully Addressed the Impacts of Personnel Shortages on the Cutter Workforce

Cutter Workforce is Increasingly Short Staffed

The Coast Guard reported it was short about 4,800 members across the entire service (including active-duty service members, civilians, and reservists) in 2023, according to the service’s fiscal year 2024 congressional budget justification. As a result, the Coast Guard operated below the workforce level it deems necessary to meet operational demands. To mitigate the effects of this personnel shortage, the Coast Guard has ongoing efforts to recruit and retain more qualified personnel. However, we recently reported that the Coast Guard lost more enlisted service members than it recruited during fiscal years 2019 through 2023 and the Coast Guard missed its military recruiting targets for enlisted personnel during the same period. We made a total of seven recommendations to improve Coast Guard recruiting and retention efforts in May 2025.[72]

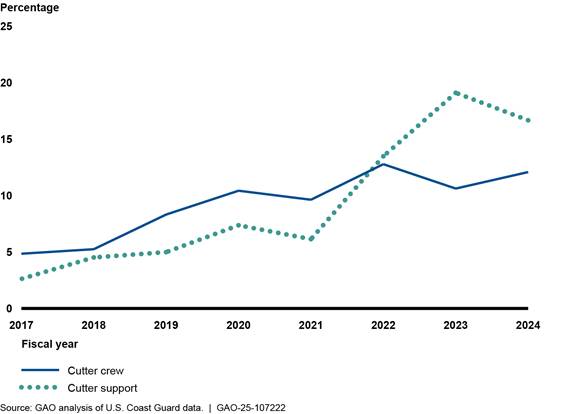

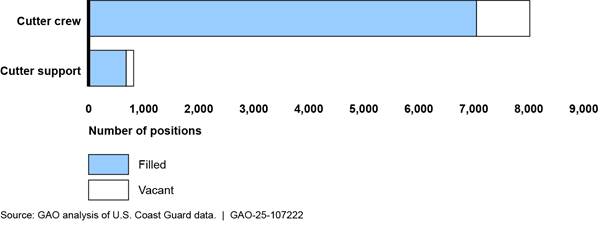

These ongoing personnel shortages impact both the cutter fleet and cutter personnel. Coast Guard officials from eight of nine districts told us that cutter personnel shortages are a major challenge to operating and maintaining the cutter fleet. Cutter crew and support position vacancy rates have increased from fiscal year 2017 through fiscal year 2024, according to Coast Guard data.[73] Specifically, our analysis shows that 1,104 cutter crew and support positions were vacant (about 13 percent) in fiscal year 2024. This is an increase from fiscal year 2017, in which 401 cutter crew and support positions were vacant (about 5 percent). As shown in figure 10, while vacancy rates for both cutter crews and support positions have increased over time, the vacancy rate for cutter support positions has increased by over 500 percent since fiscal year 2017.[74]

Note: Cutter crew positions are positions assigned to a specific cutter, and cutter support positions are positions assigned to a shore-based support team, such as a Maintenance Augmentation Team or a Weapons Augmentation Team.

In fiscal year 2024, the Coast Guard had 8,016 cutter crew positions, of which 968 (about 12 percent) were vacant; and 816 cutter support positions, of which 136 (about 17 percent) were vacant (see fig. 11).

To attempt to mitigate the effects of cutter personnel shortages on cutter operations, the Coast Guard’s Force Alignment Initiative made adjustments to the Coast Guard’s management of its assets and workforce, to include how it operates its cutters.[75] As part of this initiative, the Coast Guard de-staffed 23 seasonal boat stations, which are now used only when needed to support specific operations, and reduced duplicative search and rescue coverage for 19 boat stations.[76] Additionally, to further address personnel shortages, the Coast Guard temporarily removed from service, or laid up, seven 87-foot patrol boats and placed five 65-foot harbor tugs on standby for use as needed, and assigned crew of these cutters elsewhere. The Coast Guard also laid up four 210-foot Medium Endurance Cutters in fiscal year 2024. The crew and support personnel from all laid up cutters were assigned elsewhere to relieve existing short-staffed units.

Existing Staffing Data Does Not Account for Staff Availability

Existing cutter crew and support positions vacancy data do not account for staff availability and cutter operators told us that, in their efforts to meet mission demands during the ongoing workforce shortage, their workload has increased. Coast Guard officials from seven of nine districts told us that increased workload for cutter personnel was one of their major challenges. Specifically, multiple Coast Guard officials told us that due to cutter personnel shortages, cutters often deploy without a full crew, and the remaining crew must take on the responsibilities of missing staff. Cutter operators told us that operational commanders often move staff between cutters based on “deals” between commanders. These arrangements allow cutters to get underway with available personnel, but cutter operational commanders often do not report these deals to higher commands, according to Coast Guard officials. As a result of working without a full crew or moving crew between cutters, cutter crew and support personnel may not receive the rest for which they had been scheduled, according to cutter operators.

Coast Guard officials also told us that cutter crew and support personnel must work more hours to address the increased maintenance needs of the cutter fleet in addition to staffing shortages. For example, the crew of one cutter told us that the increased maintenance needs of the cutter reduced the crew’s availability to spend time with family in between deployments. Officials from one district told us that responsibility for completing maintenance and getting underway ultimately falls on cutter crews, which is increasingly exhausting for cutter crews that are often already short-staffed and contributes to burnout. Another district official stated that cutter engineering staff are working more hours than they should to keep cutters operational and that the “Coast Guard is maintaining these cutters on the backs of their people.”

Officials from six of nine districts told us they had concerns about cutter crew exhaustion or burnout due to increased workload. Some Coast Guard officials stated increased workload is negatively impacting staff retention. For example, multiple crew members assigned to one cutter we spoke with told us they have considered leaving or plan to leave the Coast Guard due to the long hours required. We previously reported that high workloads and pace of operations decreased morale and affected retention, according to Coast Guard service members.[77] For example, we previously found that staffing shortages have generally resulted in more collateral duties, which increased the burden and demand on members who remain with the service.

The Coast Guard maintains a list of approved active duty, civilian, and reserve personnel positions within the Coast Guard, called the Personnel Allowance List. Employees are assigned to a position, department, and location described in the list, and not all positions listed are filled. Coast Guard leadership uses the Personnel Allowance List to inform personnel assignments.

Coast Guard officials told us a cutter can appear fully staffed based on the number of positions in the Personnel Allowance List that are filled, but personnel aboard the cutter can still experience increased workload when filled positions are temporarily empty because assigned staff are unavailable to work. Officials from three of nine districts stated that personnel assigned to a cutter crew or support positions are often not available to serve in their position due to, for example, taking parental leave, attending training, or assignment to temporary duty elsewhere. This temporary duty could also include filling in on another cutter, often without leadership awareness.

Coast Guard officials stated operational commanders, not headquarters staff, are responsible for how cutters are used and scheduled, including managing cutter crew workload. Multiple Coast Guard officials told us that operational commanders and Coast Guard personnel understand the importance of the mission and will do what is required to accomplish the mission, even if they overwork themselves. Coast Guard headquarters officials told us their human resources database does not capture detailed data to track whether cutter workforce positions are temporarily empty when individual crew members are unavailable to work due to leave, training, or temporary duty. Because the existing Personnel Allowance List informs personnel assignments and does not account for which cutter workforce positions are temporarily empty, Coast Guard leadership cannot fully understand the extent of cutter workforce gaps, and therefore is not able to inform personnel assignments to effectively manage these gaps.

The Coast Guard’s Framework for Strategic Mission Management, Enterprise Risk Stewardship, and Internal Control states that management should collect and use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[78] By regularly collecting and analyzing data to show which cutter workforce positions are temporarily empty across the cutter fleet and using this information to inform personnel assignments, the Coast Guard could help ensure it is fully considering the workload faced by cutter crews and support personnel when making decisions. Collecting this information and using it to inform personnel assignments will allow the Coast Guard to make an informed decision about what the service is asking of cutter crews and support personnel to meet the mission.

Conclusions

The Coast Guard cutter fleet is a critical resource to help the Coast Guard ensure the safety, security and stewardship of U.S. waters. Growing mission demands underscore the importance for the Coast Guard to identify its resource needs, including the needs of the cutter fleet and its maintenance as well as the workforce needed to operate them.

However, the Coast Guard faces increasing cutter maintenance challenges, including deferred maintenance and the delays caused by long lead times and obsolete parts, that are adversely affecting the availability and capacity of the cutter fleet to conduct operations. These challenges delay needed repairs and can compound smaller maintenance issues into larger and more expensive issues, ultimately impacting mission readiness. By systematically collecting and assessing data on instances where deferred maintenance may have caused equipment failures and using that information to develop mitigation strategies, as appropriate, the Coast Guard may use its finite resources more effectively by prioritizing addressing maintenance issues that are more likely to cause equipment failures.

Additionally, the Coast Guard does not have complete information on what parts and systems are or will become obsolete for specific cutter types or across the cutter fleet. While Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Boards are the primary source of information used to asses’ obsolete parts and systems, the Coast Guard has not completed these boards at the intervals prescribed in Coast Guard policy. Completing Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation boards for all cutter types, as prescribed by policy, could support the Coast Guard in proactively addressing obsolete parts and systems. In addition, systematically assessing which parts and systems across the cutter fleet are or will become obsolete can also support the Coast Guard in identifying obsolescence issues that are the highest priority and developing strategies to mitigate the effects of obsolescence, including informing its acquisition approach.

Further, unplanned maintenance and delays in obtaining cutter parts affects the ability of cutters to sail in support of missions. However, the Coast Guard does not systematically collect and assess data on when cutters cannot accomplish scheduled tasks, such as training or patrols, due to unplanned maintenance issues. Systematically collecting and assessing data on cutter days lost due to unplanned maintenance issues could enable the Coast Guard to better measure and communicate the impact of increasing maintenance issues on the Coast Guard’s ability to meet mission requirements.

Finally, the Coast Guard is undertaking efforts to recruit and retain more qualified personnel to mitigate the effects of a workforce shortage that impacts both the cutter fleet and cutter personnel. However, existing data on which cutter crew and support positions are filled does not account for staff availability while the workload of the cutter-related workforce is increasing. Cutters often deploy without a full crew and cutter personnel are working more hours to meet mission demands, which is increasingly exhausting and contributes to burnout and retention issues. Regularly collecting and analyzing data on staff availability for cutter crew and support personnel positions, including which cutter workforce positions are temporarily empty across the cutter fleet, could help the Coast Guard more fully understand the extent of workforce gaps. Using this information to inform personnel assignments could help ensure the Coast Guard is fully considering the impact of these gaps on the workload faced by cutter crews and support personnel when making decisions.

Recommendations for Executive Action

The Commandant of the Coast Guard should systematically collect and assess data on instances where previously deferred maintenance may have caused cutter equipment failures and develop mitigation strategies as appropriate. (Recommendation 1)

The Commandant of the Coast Guard should complete Ship Structure and Machinery Evaluation Boards for all cutter types at the intervals prescribed by policy. (Recommendation 2)

The Commandant of the Coast Guard should systematically collect and assess data on which parts and systems across the cutter fleet are or will become obsolete and develop mitigation strategies as appropriate. (Recommendation 3)

The Commandant of the Coast Guard should systematically collect and assess data on cutter days lost due to unplanned maintenance issues. (Recommendation 4)

The Commandant of the Coast Guard should regularly collect and analyze data on staff availability for cutter crew and support personnel positions, including which cutter workforce positions are temporarily empty across the cutter fleet, and use this information to inform personnel assignments. (Recommendation 5)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Homeland Security for review and comment. DHS provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix II. In its comments, DHS agreed with the first four recommendations and described the Coast Guard’s planned actions to address them. It did not agree with the fifth recommendation, as discussed below. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

DHS did not agree with the fifth recommendation, that the Coast Guard should regularly collect and analyze data on staff availability for cutter crew and support personnel positions, including which cutter workforce positions are temporarily empty across the cutter fleet, and use this information to inform personnel assignments. In its response, DHS noted that the Coast Guard’s Personnel Service Center tracks unit vacancies using a “Direct Access” tool and fills them through its standard assignment process and timelines. DHS also stated that temporary vacancies are managed by the Coast Guard at the unit level and, if a temporary vacancy affects cutter operations, units may request support through the Coast Guard’s surge staffing process. However, DHS did not explain how these processes are used to collect data on temporary vacancies at the unit level that may not be addressed through the Coast Guard’s surge staffing process. Furthermore, DHS’s response did not include information on how these data are analyzed, for example, to assess the impacts of temporary vacancies on the workload of the cutter workforce, or to better understand the extent of cutter workforce gaps across Coast Guard units.

We maintain that the Coast Guard should regularly collect and analyze data on staff availability for cutter crew and support personnel positions, including which positions are temporarily empty, and use this information to inform personnel assignments. We noted earlier in our report that the Coast Guard has a process in place to track the extent to which cutter workforce positions are filled, using its Personnel Allowance List. In addition, we reported that operational commanders, not headquarters staff, are responsible for how cutters are used and scheduled, including managing cutter crew workload. However, we also reported that, due to cutter personnel shortages, cutters regularly deploy without a full crew and operational commanders move staff between cutters to enable a cutter to get underway, often without reporting these temporary arrangements to higher commands.

As noted earlier, we previously reported that high workloads and pace of operations decreased morale and affected retention, according to Coast Guard service members.[79] In conducting this review, Coast Guard officials from six of nine districts told us they had concerns about cutter crew exhaustion or burnout due to increased workload, with some officials stating that the increased workload is negatively impacting staff retention. Given the critical role of cutters in carrying out the Coast Guard’s missions and the increasing demands placed on the cutter workforce, we continue to believe that regularly collecting and analyzing staff availability data at all levels, to include information on the extent of temporary vacancies at the unit level, will help ensure the Coast Guard is fully considering the impact of these gaps on the workload faced by cutter crews and support personnel when making decisions.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of Homeland Security. In addition, the report is also available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at macleodh@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Heather MacLeod

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

This report examines (1) how the Coast Guard cutter fleet changed during 2012 through 2024, (2) the challenges the Coast Guard faces in operating and maintaining the cutter fleet, and (3) the extent the Coast Guard has filled its cutter workforce positions and determined its cutter-related workforce needs.

To address all of our objectives, we interviewed officials representing both Coast Guard area commands and all nine districts about operating and maintaining the cutters under their command, including information on cutter fleet changes during 2012 through 2024, operational targets, cutter challenges, workforce needs, and personnel shortages.[80] We also conducted site visits to Coast Guard offices located in three of nine districts to tour eight Coast Guard cutters and interview cutter crews representing six different cutter types.[81] We selected these three districts to represent a mix of Coast Guard cutter types as well as geographic location in order to observe a variety of operating environments and Coast Guard missions supported by the cutter fleet.

While the information obtained from our interviews with cutter crews in these locations is not generalizable to all cutter types or operating environments, it provided valuable insights about challenges the Coast Guard faces in operating and maintaining cutters, their impact on the Coast Guard’s ability to conduct missions, and Coast Guard efforts to address or mitigate the challenges identified. We also interviewed Coast Guard headquarters officials representing the Offices of Cutter Forces, Naval Engineering, and Requirements and Analysis. In addition, we visited the Coast Guard Yard—the Coast Guard’s sole shipbuilding and major repair facility located in Baltimore, Maryland—to tour the facility and interview Coast Guard officials about cutter availability, maintenance and repairs, and related challenges.

To examine how the Coast Guard cutter fleet changed, we analyzed cutter data obtained from the annual Register of Cutters of the U.S. Coast Guard for the period 2012 through 2025.[82] We interviewed relevant agency officials, reviewed related documentation, and assessed the data for missing data and obvious errors in accuracy and completeness to determine their reliability. Based on these steps, we determined these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of presenting data on the numbers and types of cutters over time.

To identify the challenges the Coast Guard faces in operating and maintaining the cutter fleet, we determined the extent to which the Coast Guard met cutter operational availability and usage time targets by analyzing data from the Coast Guard’s Asset Logistics Management Information System and Electronic Asset Logbook system for fiscal years 2012 through 2024.[83] We also reviewed Coast Guard guidance, instructions, and manuals, such as the Coast Guard’s Cutter Scheduling Standards and the Naval Engineering Manual, to identify the applicable cutter availability metrics and usage time targets for each cutter type over our review period.[84] We interviewed relevant agency officials, reviewed related documentation, and assessed the data for missing data and obvious errors in accuracy and completeness to determine their reliability.

Based on these steps, we determined these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of presenting cutter operational availability rates and cutter usage data over time. However, we found data on operational availability rates for multiple cutter types during fiscal years 2012 through 2015 to be missing. According to the Coast Guard, these data are not available for the identified cutter types and fiscal years because these cutters were being transitioned to Coast Guard’s Asset Logistics Management Information System and Electronic Asset Logbook system between 2012 and 2015. For this reason, we limited our analysis of cutter operational availability in this report to fiscal years 2016 through 2024.

Additionally, for purposes of this report, we also excluded two cutter types (which are currently part of the cutter fleet) from our analysis of operational availability and usage time targets. Specifically, we excluded the 295-foot Training Cutter Eagle because it was not used to conduct any Coast Guard missions during our review period. Secondly, we excluded the 140-foot icebreaking tug cutter type from our analysis of operational availability as we determined Coast Guard data for this cutter type was not sufficiently reliable for any years during our review period due to missing and incorrect data fields.

To further identify the challenges the Coast Guard faces in operating and maintaining the cutter fleet, we analyzed available Coast Guard data on cutter maintenance and associated costs. This included data on cutter planned maintenance, unplanned maintenance issues (such as repairs or dry docks), key mission degraders, deferred maintenance, and related costs—to include maintenance-related expenditures and budget shortfalls—for fiscal years 2015 through 2024, the time period for which the Coast Guard was able to provide data.[85] We obtained these data from multiple Coast Guard systems, including the Asset Logistics Management Information System, Asset Material Management Inventory System, Financial Systems Modernization Solution, and the Naval and Electronics Supply Support System.[86] To assess the reliability of these data, we obtained written responses from relevant agency officials, reviewed related documentation, and assessed the data for missing data and obvious errors in accuracy and completeness. Based on these steps, we determined these data to be sufficiently reliable for the purposes of presenting cutter maintenance-related challenges and costs.