TEMPORARY ASSISTANCE FOR NEEDY FAMILIES

HHS Could Facilitate Information Sharing to Improve States’ Use of Data on Job Training and Other Services

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107226. For more information, contact Kathryn A. Larin at (202) 512-7215 or larink@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107226, a report to congressional requesters

TEMPORARY ASSISTANCE FOR NEEDY FAMILIES

HHS Could Facilitate Information Sharing to Improve States’ Use of Data on Job Training and Other Services

Why GAO Did This Study

Annually, TANF provides about $16.5 billion to states to help millions of low-income individuals and families. In fiscal year 2022, states spent more than 44 percent of federal TANF and state funds on non-assistance services. Questions have arisen about how states use and account for TANF funds. GAO was asked to review TANF non-assistance spending.

This report examines (1) how selected states have used TANF non-assistance funds, (2) non-assistance data collected and used by selected states, and (3) any data challenges faced by selected states and the extent to which HHS provides support to address these challenges. This report is part of a series of reports on TANF GAO issued in 2024 and 2025 (GAO-25-107235 and GAO-25-107290).

GAO analyzed selected states’ fiscal year 2022 TANF expenditure data, the most recent available at the time of GAO’s analysis. GAO also interviewed HHS officials, those knowledgeable about TANF, and state and local officials in a nongeneralizable selection of seven states (Illinois, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wyoming). These states were selected to reflect variation in geographic region and the percentage of residents in poverty. GAO reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and agency documents.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that HHS facilitate information sharing among state TANF agencies on using data on non-assistance services. HHS agreed with this recommendation.

What GAO Found

The Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant funds cash assistance and certain “non-assistance” services. These services include work, education, and training activities; childcare; and child welfare services (see fig.). The seven states GAO reviewed varied in the percentage of TANF funds spent on these different services, reflecting their distinct priorities. State officials told GAO that their states often combined TANF funds with other funds, including other federal grants or state funds, to provide these services.

Officials from selected states generally reported collecting various demographic, participation, and outcome data on individuals and families receiving services supported by TANF non-assistance funds. Officials reported that they used various data to make eligibility determinations, monitor program performance, and adjust the delivery of TANF non-assistance services. Service providers report some data on services funded with non-assistance to state agencies, but there are no federal TANF reporting requirements for performance information on services funded with non-assistance funds. To address this, in December 2024, GAO recommended that Congress consider granting HHS additional oversight authority and also recommended that HHS improve existing reporting requirements. For certain instances in which states used TANF non-assistance funds in combination with other federal funding streams, states and service providers were subject to other federal reporting requirements.

Officials from selected states reported that they encountered a range of challenges using data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. These challenges sometimes hindered states’ ability to assess whether the services improved participant outcomes. HHS’s technical assistance initiatives have supported states’ TANF data efforts. However, HHS’s initiatives have focused on assistance while non-assistance has accounted for an increasingly large share of TANF spending. Officials from the selected states expressed an interest in learning from one another to improve their efforts to use data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. By facilitating such information sharing, HHS could help states improve their oversight of non-assistance funds and their efforts to improve participant outcomes.

Abbreviations

CCDF Child Care and Development Fund

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019

HHS U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

MOE maintenance of effort

SSBG Social Services Block Grant

TANF Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

WIOA Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 24, 2025

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

The Honorable Darin LaHood

Chairman

Subcommittee on Work and Welfare

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

Each year, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) supports millions of low-income individuals and families with children by providing assistance—cash, payments, and vouchers designed to meet a family’s ongoing basic needs—and other services to foster economic security and family stability.[1] These other services, called “non-assistance” services, include work, education, and training activities; child care; child welfare services; refundable tax credits; and emergency aid for housing, energy, and clothing. Annually, the federal government provides about $16.5 billion to states in TANF block grants. In addition, states are required to contribute their own funds, collectively spending approximately $15 billion annually. As we reported in September 2024, states have increasingly shifted federal and state TANF spending from assistance to non-assistance services.[2] For example, in fiscal year 1997—the year after TANF was signed into law—states spent about 23 percent of federal TANF and state funds on non-assistance services. By fiscal year 2022, that figure had risen to more than 44 percent.[3]

Although a large share of federal TANF and state-related funds are spent on non-assistance services, we reported in March 2006 and December 2012 that little information exists on those served with TANF non-assistance funds, what services are funded, and how these services fit into a strategy or approach for meeting TANF goals.[4] In light of cases in which TANF funds have been misused and the potential for fraud, waste, and abuse, questions have been raised about how states use and account for their TANF spending.[5]

You asked us to review data collected and used on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. This report examines (1) how selected states have used TANF non-assistance funds, (2) what non-assistance data selected states have collected and how they have used these data, and (3) any data challenges selected states have faced and the extent to which the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provides support to address these challenges.

To address these objectives, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of seven states to conduct in-person site visits and virtual interviews.[6] We selected states to capture variation in geographic region and the percentage of residents in poverty using the most recently available federal data at the time of selection.[7] Within each region, we selected the state with the highest percentage of residents under the federal poverty level and the state with the median percentage of residents under the federal poverty level. Within each state, we interviewed officials in the state’s TANF-administering agency, one to three other state agencies that provided services with TANF non-assistance funds, and a local agency or organization that provided services to clients.[8] Also, we interviewed individuals from several organizations who were knowledgeable about TANF on topics including data collected on non-assistance-funded services, states’ performance measures, states’ flexibility in using TANF funds, and oversight of TANF funds.[9]

We also took additional steps to address each objective. To address our first objective, we analyzed selected states’ TANF expenditure data from fiscal year 2022, the most recent data at the time of our analysis. Based on our analysis, we selected the four largest spending categories in these states to examine further: work, education, and training; child care; child welfare; and early care and education. In addition, we selected the spending category of non-recurrent short-term benefits for our review because of the variety of services that may be funded through this category. We assessed the reliability of the expenditure data by checking for missing data or obvious errors and interviewing HHS officials about their processes for collecting and reporting these data. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this analysis.

To address our second objective, we analyzed information from each selected state regarding demographic, program participation, and program outcome data collected on those served with TANF non-assistance funds.[10] To address our third objective, we interviewed officials in HHS’s Administration for Children and Families, including officials in five regional offices that support the states we selected. During these interviews, we discussed allowable uses of TANF non-assistance funds, data collected and used by states and related challenges states face, and the technical assistance HHS provides. Also, we reviewed relevant federal documentation, such as HHS’s most recent strategic plan, expenditure data reporting instructions, and an agency report on a TANF data technical assistance effort.[11]

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

TANF Legislation and Funds

The TANF block grant was created by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996.[12] This law consolidated several programs serving needy families, including an assistance program for families with children, into the broad-purpose TANF block grant. The TANF block grant provides approximately $16.5 billion annually to states in fixed federal TANF funding, an amount that generally has not increased since 1996. As a condition of receiving its full federal grant award, a state must also contribute its own funds—referred to as maintenance of effort (MOE) funds.[13] TANF funds generally must be used for services that are reasonably calculated to meet one of TANF’s four purposes, which are: (1) to provide assistance to needy families so that children may be cared for in their own homes or the homes of relatives; (2) to end dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage; (3) to prevent and reduce out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and (4) to encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.[14]

TANF Expenditures

TANF expenditures generally fall into two categories: assistance and non-assistance.[15]

· Assistance expenditures. In fiscal year 2022, states spent $7.9 billion of federal and state MOE funds on assistance.[16] These expenditures include cash, payments, and vouchers designed to meet a family’s ongoing basic needs. Examples include monthly cash payments to qualifying low-income families, foster care payments, and certain subsidies for adoption and guardianship.[17] Assistance also includes expenditures for supportive services, such as child care, provided to families who are not employed to help them participate in the workforce. Only families with a minor child or families with a pregnant individual who are financially needy may receive federally funded assistance, and they may only receive assistance for up to 60 months.[18] States and territories have discretion to define certain eligibility requirements for assistance, including financial neediness, and to set benefit amounts. Federal statute requires states to meet work participation rate targets that measure how well states engage families receiving assistance in certain work activities.[19]

· Non-assistance expenditures. In fiscal year 2022, states spent $13.8 billion of federal and state MOE funds on non-assistance.[20] These include expenditures for child care for families who are employed as well as for work, education, and training activities for individuals and families regardless of employment status.[21] They may also include pre-Kindergarten and Head Start; nonrecurrent short-term benefits, such as emergency housing payments; child welfare services; other services for children and youth; and services for out-of-wedlock pregnancy prevention, fatherhood, and two-parent family formation and maintenance. States are generally allowed to spend TANF funds on non-assistance services rather than assistance as long as these services are reasonably calculated to meet TANF’s statutory purposes.

TANF also gives states flexibility to set various program policies for these expenditures. For example, states can determine the respective amounts to allocate toward assistance and non-assistance services and decide the benefit levels of assistance and eligibility requirements. In contrast to expenditures for assistance, expenditures for non-assistance services have fewer federal requirements. For example, participants in TANF non-assistance-funded services are not subject to time limits or work requirements. Because states may decide which residents are eligible for individual non-assistance programs, these services can be made available to a greater number of a state’s residents.

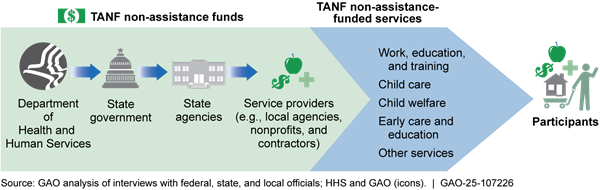

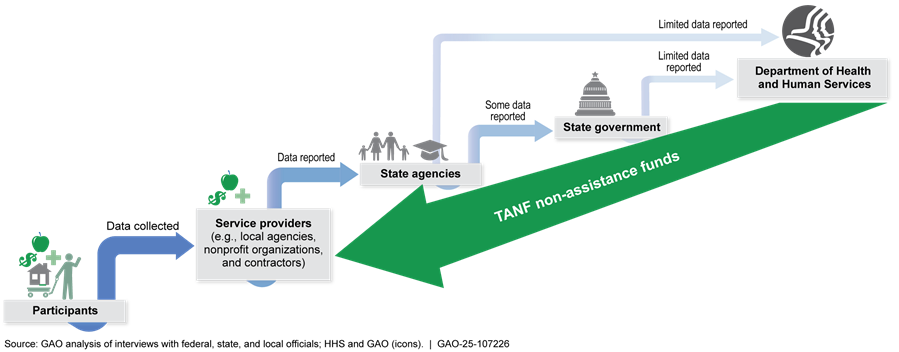

Federal and State Oversight of TANF

HHS distributes federal TANF funds to state agencies, which oversee an array of service providers—local agencies, nonprofit organizations, and other contracted organizations—that directly administer non-assistance services. State legislatures may appropriate TANF funds to other state agencies, or the state TANF agency may enter into agreements with other state agencies to further distribute the funds (see fig. 1).[22]

Figure 1: Example of How Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Non-assistance Funds Flow from the Federal Government to State and Local Entities to Provide Services to Participants

The Office of Family Assistance within HHS’s Administration for Children and Families oversees and administers TANF. HHS’s responsibilities include reviewing state TANF plans, providing states with TANF-related guidance, and collecting and publishing state expenditure data. Federal law sets forth the basic TANF reporting requirements for states. For example, states are required to provide information and report on their use of TANF funds to HHS through quarterly reports on demographic and economic circumstances and work activities of families receiving assistance through state TANF plans outlining how each state intends to run its TANF program and through quarterly financial reports providing data on federal TANF and state MOE expenditures.[23] HHS reviews state information and reports to ensure that states meet the conditions outlined in federal law. HHS also assesses whether states meet their TANF work participation rates, which measure how well states engage families that receive assistance in certain work activities during a fiscal year.

Prior and Ongoing GAO Reviews of TANF

In April 2022, as part of our reporting on payment integrity of COVID-19 spending, we reported that HHS said it does not have the authority to obtain the information it needs to estimate or report improper payment information for its TANF program. We recommended that Congress consider providing HHS the authority to require states to report the data the agency needs to estimate and report on improper payments for TANF.[24]

In addition, we recently issued two reports on other aspects of TANF spending and monitoring, including state budget decisions regarding TANF funds and HHS’s efforts to manage fraud risks.[25] In 2025, we plan to issue two reports, one on HHS’s oversight of TANF single audit findings and one on child welfare spending under TANF, including states’ use of TANF funds as payments to foster families and for child welfare services.

Selected States Use TANF Non-assistance Funds with Other Funds to Provide a Range of Job Readiness Services, Child Care, and Varied Other Supports

Selected States Varied in How They Allocated Funds and Provided Services Based on Their Priorities and the Needs of Their Target Populations

The seven selected states we reviewed varied in the percentage of TANF funds they spent on different non-assistance services such as work, education, and training services; child care; child welfare services; early care and education; and other services.[26] State officials told us their states’ use of federal TANF funds was influenced by the priorities of the state government, TANF’s structure as a flexible funding stream, the amount and type of state MOE expenditures, and the needs of their target population.[27] Officials reported that a significant focus was ensuring that their use of non-assistance funding met at least one of the four TANF purposes.

Work, education, and training services. Officials in all seven selected states reported that their states provided various work, education, and training services using TANF non-assistance funds.[28] Officials reported that the types of services varied, even within states, depending on state priorities and the specific needs of participants. Services included job preparation and work activities such as job readiness training, resume writing and interview preparation, help with the job search process, subsidized employment, and skills training. For example, in New Mexico, officials reported that the state’s Department of Workforce Solutions, which oversees the New Mexico Works program, used non-assistance funds primarily for services like training and employment-related skills development. The goals of the program are to stabilize their clients’ home environments and make families more independent through skill development and job-related technology literacy and to help assistance recipients meet their work requirements.

Child care. Officials in five of the selected states reported that their states supported child care using TANF non-assistance funds.[29] These states subsidized the cost of child care for families that need child care to work or participate in work activities through state- or county-administered child-care systems or contracted service providers. For example, officials reported that child care is Ohio’s largest category of non-assistance spending at $230 million. Ohio operates a publicly funded child-care program through which the state subsidizes the cost of child care for eligible families. The program offers financial assistance to eligible parents with incomes generally below 145 percent of the federal poverty level to help them pay for child care while they engage in work, education, or job training activities.

Child welfare services. Officials in five of the selected states reported that their states funded child welfare services using TANF non-assistance funds.[30] These states generally used these funds for salaries for social workers, whose work focuses on family unification efforts. State officials generally stated that their goal was to minimize the number of children who come into state custody. For example, officials in Illinois reported that the state’s Department of Human Services transfers $17 million in TANF non-assistance funds per quarter to the state’s Department of Children and Family Services for child welfare services aimed at keeping families intact and assisting teen parents.

Early care and education. Officials in five of the selected states reported that their states funded early care and education services using TANF non-assistance funds.[31] For example, Texas’s Health and Human Services Commission administers an early childhood intervention program that serves children with developmental delays and covers case management services beyond what is covered under Medicaid. The program uses TANF non-assistance funds as one of its funding sources.

Other services. Officials in all seven selected states reported that their states used TANF non-assistance funds to provide a variety of additional services to low-income families, including transportation, public health initiatives, housing assistance, and other wraparound services.[32] For example:

· Officials in Ohio reported that the state’s Benefit Bridge Program is supported, in part, by $15 million in TANF non-assistance funds. The Benefit Bridge assists low-income individuals who do not meet certain eligibility requirements for other benefits, such as for nutrition assistance or child care. The program aims to reduce the effect of the “benefits cliff” by helping eligible individuals pay for services such as transit allowances or additional job training.[33]

· Officials in Wyoming reported that through a $1.77 million annual grant to its Department of Health, the state uses TANF non-assistance funds to support a home visitation program for first-time mothers, mothers living in poverty, mothers experiencing intimate partner violence, and mothers who are incarcerated.

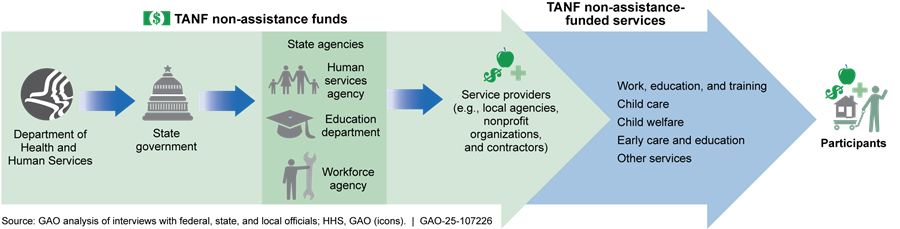

· Officials with New Mexico’s Children, Youth, and Families Department reported providing funding to Hope Works, a service provider that focuses on keeping families together by addressing homelessness (see fig. 2). The program received approximately $900,000 in TANF non-assistance funds in fiscal year 2024, according to officials. Case workers collect information about barriers a family might currently be facing—such as difficulty paying off debts or food insecurity—and connect them to stable housing, among other services.

Figure 2: A Hope Works Center in New Mexico, Funded by Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Non-assistance and State Funds, Seeks to Help Participants Achieve Housing Stability

· Officials with the Springfield Urban League, a service provider in Illinois, reported receiving $196,000 in TANF non-assistance funds each year from the state’s Department of Human Services to provide services such as job training, high school certification, and mobile wellness clinics (see fig. 3). In addition, the organization provides a range of other supports, including funds to pay for clothing and supplies for work, transportation, utilities, and supplies such as detergent, soap, and pantry items.

Figure 3: The Springfield Urban League Uses Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Non-assistance Funds to Provide Job Training and High School Certification

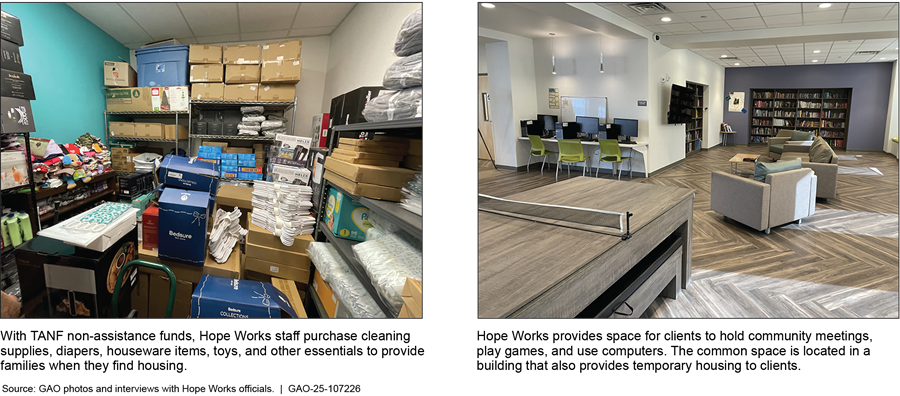

States Often Combine TANF Non-assistance Funds with Other Federal and State Funding Sources to Provide Services to Low-Income Participants, According to Selected State Officials

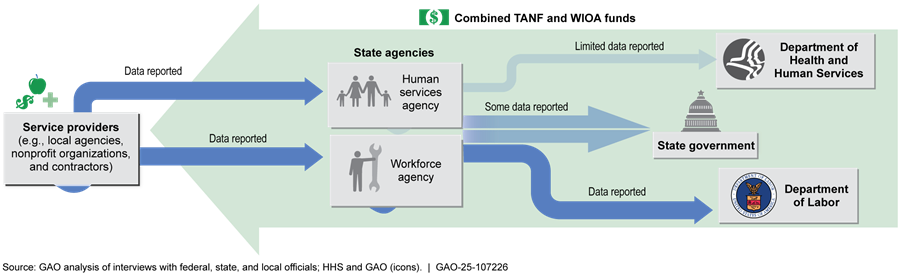

TANF non-assistance funds are one of many funding sources that states can allocate to service providers—including state and local agencies, nonprofit organizations, and other contracted organizations—to support their programs. State officials told us that TANF funds were often combined with other funds, including other federal funds—such as funding from the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA)—and state funds appropriated by their state legislatures (including state MOE and other state funds) (see fig. 4).[34] In some cases, TANF funds were formally transferred for use under other programs, including the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG).[35] In these instances, states are required to use and report on the funds consistent with the requirements of the block grant receiving the funds. For example, TANF funds transferred to CCDF are used like CCDF funds and tracked as CCDF funds. In other cases, states used TANF non-assistance funds to provide similar services to another program, such as child care, while the state retained the flexibility associated with the funds.

Figure 4: Example of How Federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Non-assistance Funds Can Be Combined with Federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Funds and State Funds

Officials in several selected states reported that their states used TANF funds to provide child care services in combination with federal funds from CCDF. Officials also reported that TANF funds helped expand existing child welfare programs. Those programs were frequently funded, in part, with other federal sources, such as Title IV-B of the Social Security Act for services to promote the welfare of children, Title IV-E of the Social Security Act for foster care payments and adoption assistance, and SSBG funds for states to provide social services to meet certain individual needs.[36]

Officials in several states, such as Texas and Ohio, also reported that their states treated TANF as a partner program to WIOA and providing TANF non-assistance services in coordination with WIOA services.[37] Officials in Texas, for example, reported using TANF non-assistance funds for programs such as their Choices Employment Program. This program focuses on employment and training for TANF-eligible participants. Participants can be co-enrolled in TANF and WIOA programs, using different resources based on what is allowable under each specific funding stream.

State officials and service providers in the selected states generally told us that the flexibility of the TANF block grant, when paired with other funding streams, helped them provide a wider range of services to their clients. For example, officials in Ohio told us that their Prevention, Retention, and Contingency program used TANF non-assistance funds for short-term needs, such as groceries or car repairs. However, according to the officials, if a particular service is not an allowable use of funds under TANF requirements, the program can use other available funds to pay for a specific service, contributing to more stable overall funding for the program.

Service Providers and State Agencies in Selected States Collect and Use Data on Those Served with Non-assistance Funds, but Not All Data Are Federally Reported

Service Providers in Selected States Generally Collect Demographic, Participation, and Outcome Data on Participants

Officials from state and local service providers in the seven selected states generally reported collecting various demographic, participation, and outcome data on individuals and families receiving services supported by TANF non-assistance funds (see table 1). In general, data collected by these providers varies depending on the type of program participants, services offered, and nature and goals of the specific non-assistance-funded services. Most data are collected at the local level by organizations directly providing non-assistance services, such as work, education, and training services. In some cases, data are collected by state-level agencies, particularly in instances where a state agency functions as a service provider, such as when providing child welfare services. However, state TANF agencies generally did not report collecting these data from other state agencies.

Table 1: Examples of Demographic, Participation, and Outcome Data Collected on Specific Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Non-assistance-funded Services

|

Service category |

Demographic and participation data |

Outcome data |

|

Work, education, and training |

Course enrollment Types of support services Demographics (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, family size, income) Employment history Education level |

Certification completion Employment in target fields Employment retention Wage increases |

|

Childcare |

Child-to-teacher ratios Enrollment statistics Parental demographics |

School readiness Parental employment outcomes |

|

Child welfare |

Demographics Types of child welfare services |

Overall wellbeing Health improvements |

|

Early care and education |

Demographics Child-to-teacher ratios Enrollment in educational courses |

School readiness |

|

Other (examples) Housing assistance Mental health services |

Family composition Income levels Housing status Demographics Types of mental health services |

Housing stability Eviction prevention Mental health improvements Impact on job stability |

Source: GAO summary of interviews with officials and providers in selected states. | GAO‑25‑107226

Demographic data. Service providers in each of the selected states reported collecting various demographic data on individuals and families receiving these non-assistance-funded services. According to officials, the types and amount of demographic data collected varied depending on the type of TANF non-assistance-funded service being provided and specific program requirements. For example, in one state’s child care program, providers reported collecting data on age, family size, and household income. For states’ job readiness programs, providers reported collecting data on age, education level, employment history, race and ethnicity, and family size.[38]

These demographic data were most frequently collected during the intake and enrollment process and generally used to determine eligibility, as discussed below. The enrollment process generally begins with an application that includes standard contact information such as name, date of birth, and social security number. One service provider in New Mexico reported that it collected and reviewed its demographic data—including individual, family, and household data, such as income, education level, and residence—on a regular basis to determine whether any eligibility updates were needed. Different TANF non-assistance-funded services can have different eligibility criteria, such that an individual or family might be eligible for some TANF non-assistance-funded services but not others based on their income.

Participation data. Service providers in each state also reported collecting service participation data, including enrollment dates, types of services received, and duration of participation. According to officials, the types of participation data collected varied depending on individual services provided to participants and specific program requirements. For example, in the case of TANF-funded child care services, officials reported collecting data on such metrics as child-to-teacher ratios and children’s educational readiness.

Officials in New York reported that their social services agency collected a detailed count of each family served and the specific services they received. They said that this information is generally retained at the state or county level, the latter especially in cases in which services are delivered through contracts at the county level. Officials in New Mexico similarly reported that their participation data were gathered in reports from contractors and included the number of programs individuals were enrolled in, number of participants, proportion of eligible families, and number of referrals sent to contractors.

Outcome data. Service providers in each of the selected states reported collecting a variety of outcome data on individuals and families to assess the performance of TANF non-assistance-funded services, such as wellbeing scores, job placement and retention rates, and educational attainment. These outcome data varied depending on the types of services provided. For example, officials with New York City’s Department of Social Services reported placing significant emphasis on assessing program outcomes, contractor efficiency, and overall program management.

Officials in Ohio reported including performance measures in their contracts with service providers in their TANF-funded youth programs, including measures such as job retention and certifications achieved by participants in the program. For another type of service—TANF-funded housing assistance—providers reported collecting data on housing stability and eviction prevention.

Data Are Used to Determine Eligibility, Monitor Performance, and Adjust Service Delivery

Officials and service providers in the selected states reported that they used various data to make eligibility determinations, monitor the performance of programs, and adjust the delivery of TANF non-assistance services. State-level agencies functioning as service providers commonly used demographic and similar data to determine eligibility, while local service providers more frequently used participation and outcome data to monitor performance and adjust service delivery.

Determining eligibility. Providers in each of the selected states reported using demographic data to help determine individuals’ and families’ eligibility for specific TANF non-assistance-funded services and programs. After specific service providers collect income and resource information, state officials said they verify the information and determine whether applicants qualify for specific TANF non-assistance-funded services. For example, a service provider in Illinois described collecting data from applicants through an enrollment packet, which asks for information on age, race and ethnicity, family size, number of children, work history, marital status, educational achievements, military service, and criminal background. One service provider also reported conducting monthly and quarterly reviews as part of their program planning to determine whether any changes were needed based on the data.

Monitoring performance. Officials in the selected states generally told us they integrated outcome data into their monitoring processes, such as through contracts with service providers, to enhance accountability. For example, Ohio’s Cuyahoga County Department of Job and Family Services reported requiring service providers to report outcome measures such as job retention rates and certifications achieved for participants in the state’s youth programs. These programs aim to prepare young individuals for the workforce, among other goals. According to Ohio officials, these outcome measures are used to monitor the effectiveness of the programs and help improve accountability. They said the state provides these reporting requirements to counties, which then track these outcome measures for their subrecipient contracts.

Officials in all seven states reported tracking long-term outcomes for participants, such as wage growth. For example, one service provider in New Mexico described collecting data on specific performance indicators at specific times after participants exited the program. This included collecting information on measurable job-related skill gains, employment status in the second quarter after program exit, wages in the second and fourth quarters after exit, and credential attainment in the fourth quarter after exit. Meanwhile, officials in six states told us they created regular reports to track program effectiveness. For example, Illinois officials told us that they produced quarterly and annual reports on the performance of their TANF-funded services, including the employment status of participants.

Adjusting service delivery. Officials reported using participation or outcome data to refine service delivery to enhance their ability to meet participants’ needs. Officials in five states reported making data-driven adjustments to programs based on outcome data. In addition, in one case, officials reported providing funds to counties with greater need. Officials from the service provider America Works, which operates in New York City, told us they collected feedback from participants regarding the relevance and applicability of their training programs. In response, the program introduced customized training tailored to high-demand industries, such as healthcare, technology, and customer service.

Additionally, officials in four states reported using data and other assessments to tailor TANF non-assistance services to individual participants’ circumstances. For example, one service provider in Wyoming reported that its agency collected data on participants’ mental health, substance use, intimate partner violence, and children’s development. Officials reported that these data then helped them tailor their services to meet the specific needs of the eligible population.

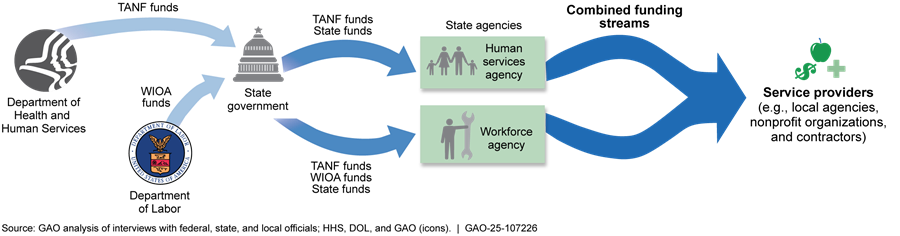

Some Non-assistance Data Are Reported to State and Federal Agencies, but Disaggregating Outcome Data Can Be Difficult

Data reporting. While individual service providers told us they consistently collected and used data at the local level, officials said that this information was not always reported up to the state or federal levels (see fig. 5). For TANF purposes, federal data reporting on non-assistance funds is limited to information on expenditures by service category. As we reported in December 2012, expenditures for non-assistance-funded services have fewer federal requirements than for assistance expenditures.[39] For example, only families that receive assistance are included in the work participation rate calculation and are subject to time limits on receiving federally funded assistance.[40]

Such conditions do not apply to families who receive non-assistance-funded services. There are no federal reporting requirements for performance information specifically on individuals or families receiving non-assistance-funded services or their outcomes. According to HHS, the agency cannot create additional requirements because its oversight of states’ use of TANF funds is constrained by its limited statutory authority.[41] In December 2024, we recommended that Congress consider granting HHS additional oversight authority related to TANF non-assistance expenditures and also recommended that HHS review and improve existing TANF reporting requirements within the agency’s statutory authority.[42] HHS agreed with our recommendation and said it will review reporting forms to improve the quality and comprehensiveness of TANF data within its statutory authority.

Figure 5: Example of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Non-assistance Data Reporting to the State and Federal Levels

Officials in each of the seven selected states said that, in certain cases, the data on non-assistance services were not necessarily reported to the state level. For example, Illinois state officials noted that local organizations report to the state only some of the demographic and outcome data on non-assistance-funded services they collect.

State officials noted that, as a result of receiving limited data, integrating the data into state-level performance reporting remained an ongoing challenge. In New Mexico, officials highlighted that some outcome data, such as job placement and retention rates, were collected by contractors and reported as part of their program performance management. However, they acknowledged that this reporting was often irregular and depended on specific programmatic requirements or contract provisions, with some data remaining solely with local service providers. Service providers in Ohio and New York also noted that while performance data were collected at the local level, they were not always systematically reported up to the state TANF agency.

For certain instances in which TANF non-assistance funding was used in coordination with other federal funding streams, state officials and service providers reported integrating TANF outcome data with those of other programs, such as WIOA, CCDF, and Social Security Act Titles IV-B and IV-E. Some officials noted that the overlapping reporting requirements provided a level of consistency across different funding streams supporting similar services and, in some cases, enabled them to conduct broader evaluations of participant outcomes.

In addition, for instances in which TANF non-assistance funds are comingled with other funding streams, such as WIOA, states and service providers can be subject to other federal reporting requirements in addition to TANF’s reporting requirements (see fig. 6). For example, the Department of Labor and the Department of Education have different reporting requirements for funding streams under their purview.[43] Meanwhile, when TANF funds are formally transferred to CCDF or SSBG, the receiving programs’ rules and reporting requirements apply to the funds. For example, according to HHS, TANF funds transferred to CCDF are subject to CCDF reporting requirements.

Figure 6: Example of Data Reporting When Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Non-assistance Funds are Combined with Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Funds

In some cases, state officials reported that they had implemented reporting requirements beyond those directly associated with TANF non-assistance-funded services (see text box below for examples).

|

Examples of States Applying Reporting Requirements Beyond Those Associated with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Texas officials reported that the state treated its TANF program as a Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) partner, and that there were certain reporting requirements specific to WIOA that they applied to participants in TANF non-assistance-funded services. Mississippi service provider officials said they adopted WIOA performance metrics as a basis for TANF non-assistance performance measures. This approach provided a tested framework for evaluating outcomes and had since evolved to better suit the specific needs of their TANF non-assistance-funded programs. New Mexico officials reported that, under the state’s childcare system, the state collected not only what was required to meet Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) reporting requirements but also additional data, including on those families receiving TANF non-assistance-funded services. Source: GAO summary of interviews with state and local officials. | GAO‑25‑107226 |

Disaggregating TANF non-assistance data. Officials in each of the selected states reported that it was either a challenge or not a current practice to disaggregate outcome data related to TANF non-assistance-funded services from data on other funding streams supporting similar services. Officials said that this was often the case when TANF non-assistance funds were used in conjunction with other funding streams. Ohio officials noted that they struggled to break down the number of participants receiving certain services or their outcomes based on the funding stream. This was due to the state funding several programs from a combined pool of separate funding sources. Similarly, officials in Texas reported that one work, education, and training program did not have performance metrics specific to TANF non-assistance, but they tracked performance metrics required by other funding sources, such as WIOA, supporting their contracts.

Officials in four states reported having varying degrees of success in disaggregating TANF non-assistance outcome data from other funding stream data. Officials in two of those states indicated that they were working toward improving their ability to distinguish TANF non-assistance outcome data from data on other funding sources. Specifically, officials in Wyoming and Texas reported seeking ways to enhance data disaggregation. Implementation of our December 2024 recommendations may help states improve their ability to disaggregate TANF non-assistance outcome data from other data.

Selected States Reported Challenges Using TANF Non-assistance Data and Said HHS Could Facilitate More Information Sharing Among States

Officials in Six Selected States Described Challenges Using Data That Sometimes Hindered Their Ability to Assess Participant Outcomes

Although states collect and use data for a variety of purposes, officials in six states told us they had encountered a range of challenges using data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. As a result, state officials were sometimes constrained in their ability to assess participant outcomes, such as job retention, and whether services were provided effectively, as shown in table 2.

Table 2: Examples of Challenges Using Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Non-assistance Data Identified by Selected State Officials

|

Challenge |

Effect |

|

Officials in one state said that because TANF data existed in multiple data systems, it was difficult for them to match data on individuals and service providers, hindering their ability to track participant experiences across programs. Specifically, the state maintained one system with administrative data, such as data on localities and other service providers, and another system with program data, such as data on individuals, including their demographic and participation data. |

State officials are not able to attribute each participant’s outcomes to specific service providers, thus limiting the state’s ability to effectively assess how well each provider is performing. |

|

Officials in one state discussed their program to teach couples about how to build a successful marriage. They said that while they collect basic data, such as the number of participants taught and classes provided, they do not conduct satisfaction surveys or follow up with participants regarding marriage quality or duration. |

State officials do not have information on whether the program contributes to high-quality or long-term marriages, in line with the TANF purpose of encouraging two-parent families. |

|

Officials in one state said that, due to limited resources, they have not been able to hire data analysts to assess gaps in service delivery or outcomes. State officials said they need support to analyze data on childcare service provision as well as the quality of care provided based on participants’ demographic characteristics, such as race, income, or family size, among other factors. |

State officials are unable to make informed decisions on how to adjust services or measure outcomes. |

|

Officials in one state said the child welfare data they collect, such as whether families are safe or whether children are being cared for at home, do not provide officials with insights on how well children are doing. |

State officials are limited in their knowledge of the extent to which child welfare services are improving children’s lives. |

|

Officials in one state told us that they do not have outcome measures for many services provided with TANF non-assistance funds, such as child welfare and teen pregnancy services. |

State officials are not able to determine the effectiveness of these services and are limited in their ability to work with the state legislature to make informed funding decisions. |

|

Officials in one state said that service providers vary in terms of the quantity of job outcome data, such as job placement and job retention rates, provided to the state. |

State officials are unable to measure the extent to which service providers in different regions are effective in helping those served obtain and retain employment. |

Source: GAO summary of interviews with selected state officials. | GAO‑25‑107226

Note: Based on data on poverty and TANF expenditures, GAO selected seven states—Illinois, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wyoming—from which to collect information about challenges using data on TANF non-assistance-funded services. GAO also interviewed officials from Colorado because of the state’s innovative data practices.

For example, officials from one state’s TANF agency said that because TANF data existed in multiple data systems within their agency, it was difficult for them to match data on individuals and service providers. Specifically, the state maintained one system with administrative data, such as data on localities and other service providers, and another system with program data, such as data on individuals, including their demographic and participation data. Moreover, their agency received data from three other state agencies, each operating their own data systems, further complicating the TANF agency’s ability to use data collected to track participant experiences across programs. Officials in this state said that it was challenging to measure participant outcomes and to hire qualified personnel who had the needed expertise to work with performance data.

Officials in other states described challenges using data to ensure non-assistance funds were being used effectively. For example, officials in one state said their service providers varied in the extent to which they provided data on their job placement and retention rates, limiting the state’s ability to determine the extent to which non-assistance funds achieved the purposes of TANF.

HHS’s Initiatives to Improve TANF Data Focus on Assistance Data

HHS’s technical assistance initiatives have supported states’ collection and use of TANF data, primarily for assistance rather than non-assistance services.[44] From 2017 through 2024, HHS funded the TANF Data Innovation Project with the goal of providing technical assistance to federal, state, and local TANF agencies on a variety of issues related to TANF data.[45] According to HHS, the project was designed to improve staff capacity and data systems to align with the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018.[46] The act created a framework for federal agencies to take a more comprehensive and integrated approach to evidence building and to enhance the federal government’s capacity to undertake those activities.[47] HHS officials told us that that the project, and a subsequent initiative, were focused on assistance instead of non-assistance-funded services.

The TANF Data Innovation project, which focused on assistance, consisted of three elements: (1) the TANF Data Collaborative provided technical assistance and training to support eight state TANF agencies’ efforts to routinely use TANF and employment data to inform policy and practice; (2) a component to increase federal staff capacity addressed the quality, use, and analysis of administrative data within the Office of Family Assistance’s TANF Data Division; and (3) the TANF Employment Project, an ongoing project, that integrates federally reported TANF data with employment data from the National Directory of New Hires to allow for deeper analysis of the TANF program, including TANF participant outcomes by HHS and other researchers.

HHS officials told us that the project enhanced the skills of data analysts at the state level. Officials in the two states included in our review that participated in the TANF Data Collaborative also told us that the project improved their capacity to collect and use TANF data. For example, New York officials reported that they benefitted greatly from the data analysis training and from collaboration with officials in other states. As a result of their participation, New York’s TANF agency is developing a dashboard to track TANF participant outcomes that may enable state officials to make better decisions regarding services provided to TANF recipients. According to HHS, the agency has begun a spin-off initiative, known as the TANF Data Collaborative 2.0, to provide training and technical assistance on data analytics for six state and local agencies with a focus on equity in service provision.

Officials in Selected States Said They Would Benefit from Sharing Promising Practices on Using TANF Non-assistance Data

Officials in selected states expressed an interest in learning from one another to improve their efforts to collect and use data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. Specifically, officials from four of the eight states we selected told us that they would benefit from the opportunity to share promising practices related to TANF non-assistance data with other states.[48] They said they were interested in learning from other states about a variety of topics, such as data systems used by other states or agencies; analyzing data to determine patterns (e.g., across demographic groups or geographic areas); and using data analysis to improve service delivery, access, or accountability. Officials in one state told us they believed the first step was to better understand how non-assistance TANF funds were being used at the local level. They added that they would like to learn about strategies other states had used to improve data collection from local service providers.

HHS told us that because TANF is a block grant with relatively few requirements compared to other federal programs, the agency had not specifically focused on non-assistance data. Based on TANF’s statutory framework, HHS officials told us they have prioritized state flexibility in administering TANF non-assistance funds. HHS officials also said that they sought to avoid creating additional requirements for states, such as using data on services provided with non-assistance funds.[49] However, as a result, HHS does not have information about states’ interests in improving their capacity to use non-assistance data.

As of July 2024, HHS’s 2022–2026 strategic plan stated that the agency will “apply knowledge and best practices to help grantees and partners provide services that focus on social determinants of health and factors that affect economic mobility.”[50] In addition, states generally may not provide services with non-assistance funds unless they are reasonably calculated to meet one of TANF’s four purposes. Consistent with states’ interests and the agency’s strategic plan, HHS officials agreed that they had a role in facilitating information sharing when state TANF agencies expressed a need for such assistance. By facilitating such information sharing, HHS could help states improve their oversight of non-assistance funds and efforts to improve participant outcomes.

Conclusions

Over the years, TANF has evolved beyond a traditional cash assistance program. It now also serves as a source of funding for a broad range of services states provide to eligible individuals and families. Even though an increasingly large share of federal TANF funds has been spent on non-assistance-funded services in recent years, federal data reporting on these services is limited. Further, selected states reported facing challenges using data to ensure that their services are effective and consistent with TANF purposes. In December 2024, we recommended Congress and HHS take actions that may help address these challenges.

Nevertheless, while HHS provides states with some technical assistance for TANF data, technical assistance provided to date is tangentially related to non-assistance data. State officials told us they would benefit from opportunities to share promising practices related to using non-assistance data and any lessons other states had learned. HHS is in a unique position to facilitate information sharing and disseminate promising practices nationwide. With additional opportunities to share information on the use of TANF non-assistance data, states would be better positioned to improve outcomes attained by low-income individuals and families and provide greater assurance that services provided with non-assistance funds are aligned with TANF purposes.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Secretary of HHS should ensure the Assistant Secretary for Children and Families facilitate information sharing among state TANF agencies on promising practices for using data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds. For example, HHS could encourage states to share their experiences, including promising practices and challenges, with each other through conferences or workshops. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. The agency concurred with our recommendation, and also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. In written comments, reproduced in appendix I, HHS said that while the agency does not have authority to collect data on those served with TANF non-assistance funds, it agrees with our recommendation and will integrate conversations about these data in its regular peer-to-peer learning opportunities among state TANF agencies. In addition, the agency said it plans to include topics related to data quality and analysis in forums such as regional and national conferences and technical assistance learning opportunities.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of HHS, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7215 or LarinK@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Kathryn A. Larin, Director

Education, Workforce, and Income Security

GAO Contact

Kathryn A. Larin, (202) 512-7215 or LarinK@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Kristen Jones (Assistant Director), Jay Palmer (Analyst in Charge), Nicole Annunziata, and Kelly Snow made significant contributions to this report. In addition, key support was provided by Charlotte Cable, Melanie Darnell, Andrea Dawson, Alexandra Edwards, Gabrielle Fagan, Lauren Gilbertson, Gina Hoover, Flavio Martinez, Kerstin Meyer, Cynthia Nelson, Mimi Nguyen, Keith O’Brien, Claudine Pauselli, Catherine Paxton, Laura Philpott, Will Stupski, and Kate van Gelder.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]TANF was established by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. Pub. L. No. 104-193, 110 Stat. 2105.

[2]GAO, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Preliminary Observations on State Budget Decisions, Single Audit Findings, and Fraud Risks, GAO‑24‑107798 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 24, 2024); Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: More Accountability Needed to Reflect Breadth of Block Grant Services, GAO‑13‑33 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 6, 2012).

[3]In fiscal year 2022, states reported spending a total of $13.8 billion on non-assistance expenditures, which was 44 percent of total expenditures and transfers. In addition, states reported spending $7.9 billion on assistance expenditures (25 percent of total expenditures and transfers), $4.3 billion on expenditures in categories that contain both assistance and non-assistance (14 percent), and $3.2 billion on program management (10 percent). States also reported transferring $2.1 billion to eligible block grants (7 percent). See GAO, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Enhanced Reporting Could Improve HHS Oversight of State Spending, GAO‑25‑107235 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 12, 2024).

[4]GAO‑13‑33. GAO, Welfare Reform: Better Information Needed to Understand Trends in States’ Uses of the TANF Block Grant, GAO‑06‑414 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 3, 2006).

[5]Reforming Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF): States’ Misuse of Welfare Funds Leaves Poor Families Behind, Hearing Before the Committee on Ways and Means, 118th Cong. (Sept. 24, 2024). See also GAO‑24‑107798 and Where is all the Welfare Money Going? Reclaiming TANF Non-Assistance Dollars to Lift Americans out of Poverty, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Work and Welfare, Committee on Ways and Means, 118th Cong. (July 12, 2023).

[6]We selected Illinois, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wyoming. We also interviewed officials from Colorado after the state was recommended to us because of its innovative data practices.

[7]We used data from the Census Bureau’s 2022 Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates, accessed December 23, 2023, https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2022/demo/saipe/2022-state-and-county.html.

[8]We refer to agencies and other organizations that provide services with TANF non-assistance funds as “service providers” for the purposes of this report.

[9]We interviewed representatives from the American Enterprise Institute, Congressional Research Service, National Association of State TANF Administrators, and Urban Institute.

[10]We did not independently assess the validity of these data because this analysis focused on the types of data collected by the selected states.

[11]Melissa Wavelet, Erika Lundquist, Stephanie Rubino, and Bob Goerge, Building and Sustaining Data Analytics Capacity: The TANF Data Collaborative Pilot Initiative Final Report, OPRE Report 2024-068 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, 2024).

[12]Pub. L. No. 104-193, 110 Stat. 2105.

[13]To meet the MOE requirement, state expenditures must be at least 80 percent of the state’s fiscal year 1994 spending in the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program, Emergency Assistance program, Job Opportunities and Basic Skills Training program, and Aid to Families with Dependent Children-related child-care programs. States that achieve their work participation standards for the year have a lower requirement, set at 75 percent of this historical state spending.

[14]42 U.S.C. § 601. Spending intended to meet the first two purposes must be for those in financial need. Additionally, certain expenditures that were authorized under prior law but do not meet one of TANF’s purposes may be permissible. 42 U.S.C. § 604(a)(2).

[15]Federal law governing TANF generally refers to the term “assistance” and does not make distinctions between different forms of aid funded by TANF. However, HHS draws distinctions between “assistance” and “non-assistance” based on statutory provisions. HHS regulations define assistance to include cash, payments, vouchers, or other forms of benefits designed to meet families’ ongoing basic needs. 45 C.F.R. § 260.31. Assistance also includes expenditures for child care and transportation provided to parents who are unemployed. HHS uses the term “non-assistance” to refer to TANF expenditures that fulfill one of the four TANF purposes but do not meet this regulatory definition.

[16]In addition, states spent $4.3 billion of federal and state MOE funds on categories containing both assistance and non-assistance expenditures in fiscal year 2022. Child care and supportive services such as transportation are considered either assistance or non-assistance depending on whether the recipient family is employed (in which case the services are non-assistance) or not employed (in which case the services are assistance). See GAO‑25‑107235.

[17]45 C.F.R. § 260.31. See also Department of Health and Human Services, Instructions for Completion of State TANF Financial Report Form, ACF-196R (May 2022). TANF expenditures categorized as assistance include assistance provided on behalf of a child or children for whom a child welfare agency has legal placement and care responsibility and is living with a caretaker relative or a child or children living with legal guardians. This also includes subsidies to help the relatives or guardians pay for adoption expenses. Assistance expenditures may also include spending on foster care, juvenile justice, or emergency assistance payments for which states were authorized to use public assistance funds as of 1996.

[18]42 U.S.C. § 608. The 60-month time limit only applies to families in which an adult is receiving federally funded assistance and would not apply to child-only cases. States may exempt a family from the 60-month time limit by reason of hardship or if the family includes an individual who has been battered or subjected to extreme cruelty. The average number of families exempted from the 60-month time limit may not exceed 20 percent of the average monthly number of families receiving assistance. 42 U.S.C. § 608(a)(7)(C).

[19]This is based on the share of families with a work-eligible individual.

[20]GAO‑25‑107235. This amount does not include expenditures in the category of funds that include both assistance and non-assistance.

[21]In addition to assistance and non-assistance expenditures, states can use up to 15 percent of their federal TANF funds to pay for administrative expenses incurred in providing TANF benefits and services. States can also transfer TANF funds for use under the Child Care and Development Fund, which provides child care subsidies for low-income families, and under the Social Services Block Grant.

[22]Any TANF funds received by a state are subject to appropriation by the state legislature. Pub. L. No. 104-193, tit. IX, § 901, 110 Stat. 2105, 2347 (1996).

[23]According to HHS, states may include examples of intended non-assistance activities in their state plans, even though they are not required to do so.

[24]The Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 defines improper payments as any payment that should not have been made or that was made in an incorrect amount under a statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirement. Pub. L. No. 116-117, § 2, 134 Stat. 113 (2020); GAO, COVID-19: Current and Future Federal Preparedness Requires Fixes to Improve Health Data and Address Improper Payments, GAO‑22‑105397 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 27, 2022).

[25]GAO‑25‑107235; GAO, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen Fraud Risk Management, GAO‑25‑107290 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 28, 2025).

[26]We analyzed HHS’s TANF expenditure data from fiscal year 2022, the most recent data at the time of our analysis. Based on these data and our interviews with federal, state, and local officials, we selected the four largest spending categories in these states to examine further. These expenditures represent federal TANF funds only and do not include state MOE spending.

[27]For additional information regarding state TANF spending, see GAO‑25‑107235. We recently reported information on nationwide, state-level TANF spending for fiscal years 2015 through 2022 and compared specific states’ spending to U.S. total spending; see: https://files.gao.gov/multimedia/gao-25-107235/interactive/index.html.

[28]Expenditures on work, education, and training can include payments to employers or third parties to cover the costs of employee wages, benefits, supervision, training, job search assistance, and job readiness services as well as secondary and post-secondary education and job skills training.

[29]These include non-assistance expenditures for families who need child care to work or participate in work activities.

[30]Child welfare programs provide services to protect children from abuse and neglect, to help parents care for their children successfully, and to provide support to children who cannot safely live with their parents. HHS’s Children’s Bureau oversees federal funding to states for child welfare programs, and states administer these programs. The primary federal funding sources for child welfare are through Titles IV-E and IV-B of the Social Security Act, although child welfare programs are also supported by other federal funding sources, including TANF.

[31]Early care and education programs are designed to support and enrich the development, and improve the life-skills and educational attainment, of children and youth. This may include after-school programs, mentoring or tutoring programs, pre-Kindergarten or Kindergarten education programs, expansion of Head Start programs, or other school readiness programs.

[32]These include non-assistance activities not otherwise enumerated by HHS. States that include expenditures in this category must provide a description of the specific benefits and services provided and the target population in their state form submissions to HHS.

[33]According to HHS, a benefits cliff occurs when someone experiences a reduction in benefits that is larger than an income gain. “Effective Marginal Tax Rates/Benefit Cliffs,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, accessed Dec. 16, 2024, https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/marginal-tax-rate-series.

[34]HHS has reported that there are multiple ways that state and local governments could use different sources of funding to achieve specific objectives, including braiding and blending funds. With braiding, funds from multiple funding streams are used to support the total costs of a common goal (e.g., to expand access to child and family services). Each individual funding stream maintains its specific program identity, meaning that funds from each specific funding source must be tracked separately. With blending, multiple funding streams are mixed to support the total costs of a common goal. Funding sources lose their program-specific identities, meaning that costs do not have to be allocated or tracked separately by funding source. See Katie Gonzalez and Pia Caronongan, Braiding Federal Funding to Expand Access to Quality Early Care and Education and Early Childhood Supports and Services: A Tool for States and Local Communities (Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Department of Health and Human Services, Aug. 23, 2021), https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/early-childhood-braiding.

[35]Section 404(d) of the Social Security Act establishes a state’s authority to transfer TANF funds to CCDF and SSBG. Funds transferred to SSBG must be spent on programs and services for children or families with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level. 42 U.S.C. § 604(d).

[36]42 U.S.C. §§ 620 et seq.; 42 U.S.C. §§ 670 et seq.

[37]WIOA requires that certain partner programs, including TANF, provide access to career services in WIOA American Job Centers—central points of service for those seeking employment, training, and related services. WIOA also requires the Department of Labor, Department of Education, and HHS collaborate to implement requirements such as developing a common performance system and overseeing state planning.

[38]The service provider we interviewed told us that they did not always collect income information because they offered their job readiness services to a broader array of clients not limited to individuals with low incomes.

[40]States must ensure that a minimum percentage of families with a work-eligible individual receiving assistance meet work participation requirements set in law, referred to as the work participation rate.

[41]HHS generally may only collect data on TANF in accordance with Section 411 of the Social Security Act. Beyond financial data, Section 411 requires states to report on the demographic, income, and work participation data of families receiving TANF or MOE-funded assistance, as collected in the ACF-199 and ACF-209 forms. When TANF funds are transferred to another block grant, such as CCDF, data may be reported in accordance with that program’s requirements.

[43]For example, WIOA requires that the Departments of Labor and Education collaborate to implement a common performance accountability system for six core programs. WIOA establishes six performance indicators for these core programs related to participants’ employment status, earnings, and skills gains, and for effectiveness in serving employers.

[44]Assistance includes cash, payments, and vouchers designed to meet a family’s ongoing basic needs. Assistance also includes expenditures for child care and transportation provided to families who are not employed to help them participate in the workforce.

[45]Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Data Innovation Project, accessed November 22, 2024, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/project/tanf-data-innovation-project-2017-2024. The Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation and the Office of Family Assistance in the Administration for Children and Families sponsored the project.

[46]Pub. L. No. 115-435, 132 Stat. 5529 (2019).

[47]See also GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2023).

[48]We selected Illinois, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wyoming. We also interviewed officials from Colorado after the state was recommended to us because of its innovative data practices.

[49]HHS generally may only collect data on TANF in accordance with Section 411 of the Social Security Act.

[50]As of February 2025, HHS’s website stated that an updated strategic plan is forthcoming. See https://www.hhs.gov/about/strategic-plan/2022-2026/index.html, accessed February 18, 2025.