NATIONAL SECURITY SPACE LAUNCH

Increased Commercial Use of Ranges Underscores Need for Improved Cost Recovery

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Jon Ludwigson ludwigsonj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107228, a report to congressional committees

NATIONAL SECURITY SPACE LAUNCH

Increased Commercial Use of Ranges Underscores Need for Improved Cost Recovery

Why GAO Did This Study

Commercial and military activities in space have grown considerably in the last decade, with continued growth expected. This growth will increase the demand on the federal launch infrastructure that supports these activities. DOD has already invested billions of dollars into launch systems and infrastructure. To support the growing demand, DOD expects to spend over $18 billion on launch services and infrastructure over the next 5 years.

A Senate report includes a provision for GAO to assess DOD’s Phase 3 strategy. GAO’s report addresses (1) DOD’s Phase 3 strategy to meet its national security space launch demand and (2) the extent to which DOD is addressing launch-related challenges as it executes Phase 3.

To conduct this work, GAO reviewed documentation, analyzed launch data, and visited all three federally owned launch ranges. GAO also interviewed DOD officials, other federal agency officials, and contractor representatives involved in launch activities.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations, including that DOD update its regulations to better define direct and indirect cost guidance to improve its ability to recoup launch support costs and ensure that the Space Force prioritizes issuing solicitations to provide insight into payload processing schedules and centralizes national security payload processing schedules across space vehicle program offices. DOD concurred with all three recommendations.

What GAO Found

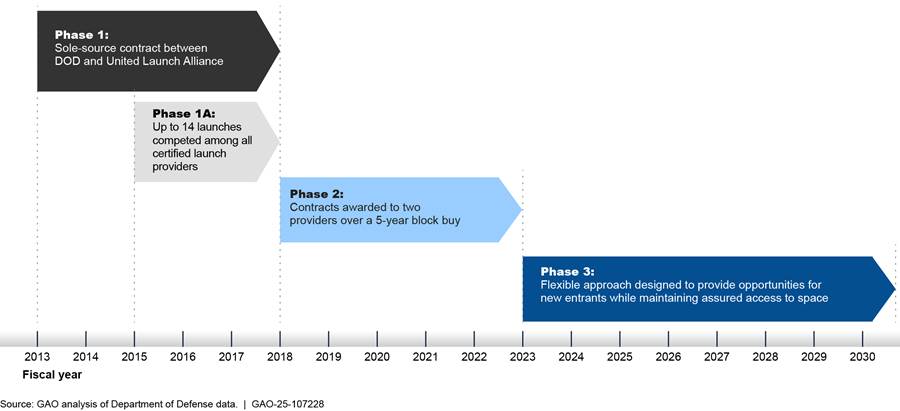

Over the last 30 years, the Department of Defense (DOD) has used different acquisition strategies to procure launches for military satellites from commercial providers. DOD’s most recent acquisition strategy—Phase 3—responds to DOD’s evolving and growing demand for launch services and infrastructure.

Phase 3 is a dual lane approach intended to lower government launch costs, ensure mission success and access to space, and facilitate competition.

· Lane 1: Expands DOD’s supply of newer commercial providers that can meet a subset of launch requirements.

· Lane 2: Assures DOD’s access to space with three commercial providers, which must meet all launch requirements for a specified number of DOD’s most critical payloads.

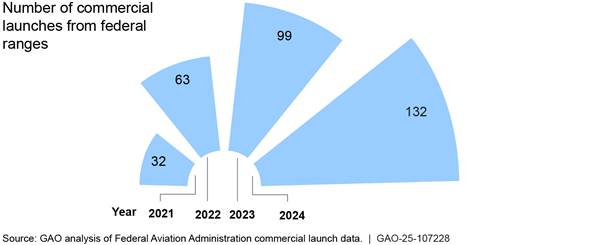

DOD is also taking steps to upgrade its launch infrastructure, which is strained by the increased rate of launches. In addition to military launches, companies use federal ranges to meet their own commercial launch needs—and commercial launches have more than quadrupled since 2021.

Increases in commercial launches have resulted in DOD providing more support to commercial entities, but DOD has struggled to accurately bill companies for direct costs. Until recently, DOD could not collect and be reimbursed for indirect costs for commercial space launch services, which include the actual costs of maintaining, operating, upgrading, and modernizing DOD space-related facilities. Recent legislation allows DOD to be reimbursed for indirect costs within certain limitations, but DOD does not have clear cost collection and reimbursement guidance for support services at launch ranges, potentially missing opportunities to recoup millions of dollars. DOD has limited payload processing capacity and lacks sufficient commercial scheduling information to manage payload processing, which is when the payload is integrated with the launch vehicle before it is transported to the launch pad. The lack of insight into commercial processing schedules hinders DOD’s efforts to coordinate processing for its own payloads. As a result, it lacks a critical tool to ensure effective coordination and efficient use of its existing and future processing capacity.

Abbreviations

|

AATS |

Assured Access to Space |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

EELV |

Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle |

|

FAA |

Federal Aviation Administration |

|

LOX-methane |

Liquid oxygen - methane |

|

NASA |

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

|

NDAA |

National Defense Authorization Act |

|

NSSL |

National Security Space Launch |

|

RSLP |

Rocket System Launch Program |

|

SpaceX |

Space Exploration Technologies Corporation |

|

SSC |

Space Systems Command |

|

ULA |

United Launch Alliance |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 30, 2025

Congressional Committees

Commercial and military activities in space have grown considerably in the last decade as the nation’s use of space-based assets for communications and national security has increased. Threats to commercial and military use of space—such as adversaries developing ways to target U.S. space assets and communications with those systems—have emerged and grown in recent years as well. In response to these threats, the Department of Defense (DOD) plans to increase launches of new satellites to replace existing capabilities or add new ones to meet the increasing demand for space-based capabilities.

The federal government has invested billions to develop launch capabilities and launch its satellites and other assets into orbits by contracting with private companies. For example, since 2008, DOD and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have collectively obligated over $48 billion to Space Exploration Technologies Corporation (SpaceX) and United Launch Alliance (ULA)—the two primary launch providers available during this time—for launch services and related activity.[1] The Air Force has obligated over $29 billion of this amount to ULA and SpaceX for launch and related services.

Further, since the start of the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program in 1995, DOD has also spent billions of dollars updating launch infrastructure to facilitate critical space launch activities. For example, among other things, DOD has improved roads and other infrastructure at the federal launch ranges, including Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Vandenberg Space Force Base. These efforts have also enabled commercial space activities at federally owned and operated launch ranges.

Continued growth of these space-based activities is likely to proceed in the future, with government and commercial launches relying on government launch sites. To take advantage of this commercial market growth and support the growing demand on infrastructure, DOD expects to spend approximately $17 billion on national security launch services and nearly $1.4 billion on infrastructure over the next 5 years. DOD’s most recent launch acquisition strategy—called Phase 3—continues to rely on commercial providers in a way that is designed to accommodate this demand.

Senate Report 118-58 to accompany a bill on the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2024 contains a provision for us to assess the National Security Space Launch (NSSL) Phase 3 acquisition strategy. Our report (1) describes DOD’s Phase 3 strategy and how it is structured to meet DOD’s national security space launch demand and (2) assesses the extent to which DOD is addressing launch-related challenges as it executes its Phase 3 acquisition strategy.

To describe DOD’s Phase 3 strategy to meet national security space launch needs, we reviewed U.S. Space Force acquisition strategies and contract documentation, among other things, and interviewed Space Force and other DOD officials. We also interviewed representatives from commercial launch providers that have provided, or plan to provide, launch services to DOD. Additionally, we interviewed officials from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and NASA to understand their roles in overseeing and participating in the launch industry. While the FAA and NASA play important roles in overseeing and participating in the launch industry, we did not evaluate their efforts to oversee or acquire launch services. We included information from them in our report to provide context for DOD’s efforts.

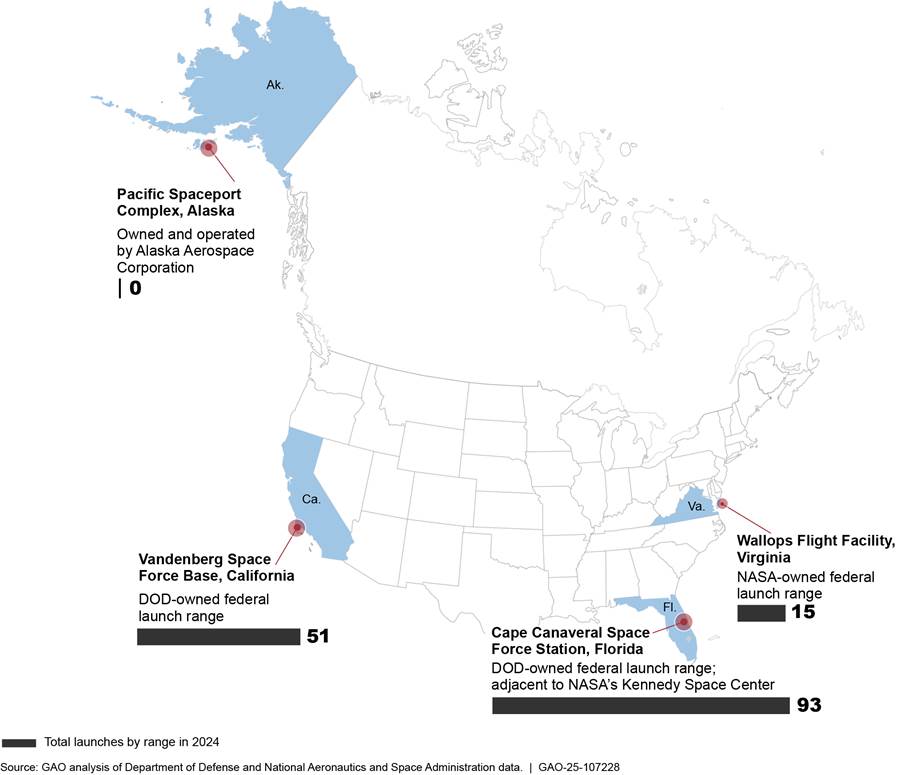

To assess the extent to which DOD is addressing launch-related challenges, we analyzed government and commercial launch data. Additionally, we conducted interviews with representatives from eight commercial launch providers and one payload processing provider. We also visited all three federally operated launch ranges: Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida; Vandenberg Space Force Base, California; and Wallops Flight Facility, Virginia. The Pacific Spaceport Complex – Alaska is located on Kodiak Island, Alaska, and provides access to space for several agencies, including the Space Force. We did not include this launch range in our review because launch activity is limited at this spaceport, and it is privately operated. Additionally, we reviewed applicable statutes and guidance regarding the Space Force’s efforts to collect funds from commercial launch providers using federal launch ranges. We analyzed actual and estimated direct charges from fiscal years 2024 through 2026 and estimated potential indirect cost reimbursements as a percentage of direct costs as authorized in statute.[2] We also analyzed launch infrastructure plans and compared these plans with applicable policy and DOD guidance. For more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, please see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Key Characteristics of Space Launch and Related Infrastructure

Space launches are generally categorized three ways:

· Military launches, also known as National Security Space launches. These launches support defense and U.S. intelligence operations. Companies providing services for military launches must be able to reliably place a range of payloads in all Earth orbits.[3]

· Civil launches. These are launches of non-defense-related government satellites for research and exploration, such as those used by NASA.

· Commercial launches. These are launches of private sector payloads, such as communications satellites and can also include lower value military payloads. Commercial launches are typically less demanding than military or civil launches, as commercial payloads can tolerate more risk than government payloads.

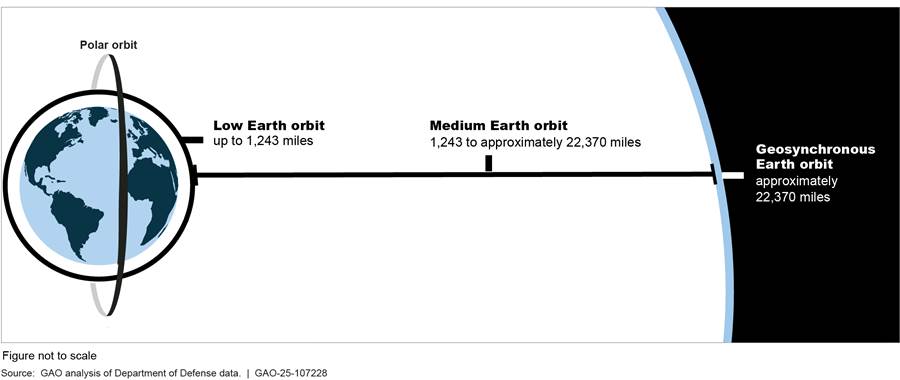

Depending on their purpose and function, satellites are generally placed in one of several orbits above Earth. Most satellites for national security space operations operate in low, medium, or geosynchronous Earth orbits as well as polar orbit. Launching satellites into space requires increasing amounts of energy to reach the orbits farther away from Earth, especially as the mass of the spacecraft increases. As a result, space lift capability is generally divided into small, medium, and heavy categories.[4] Figure 1 depicts the orbits relevant for satellite launches.

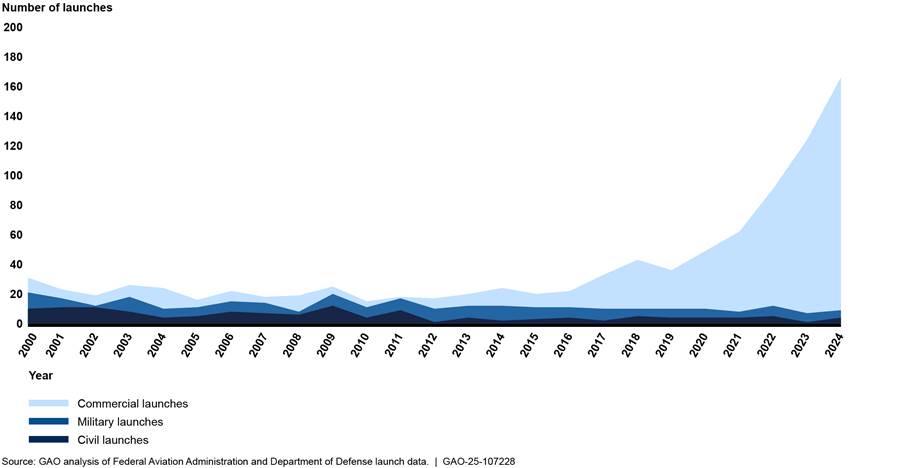

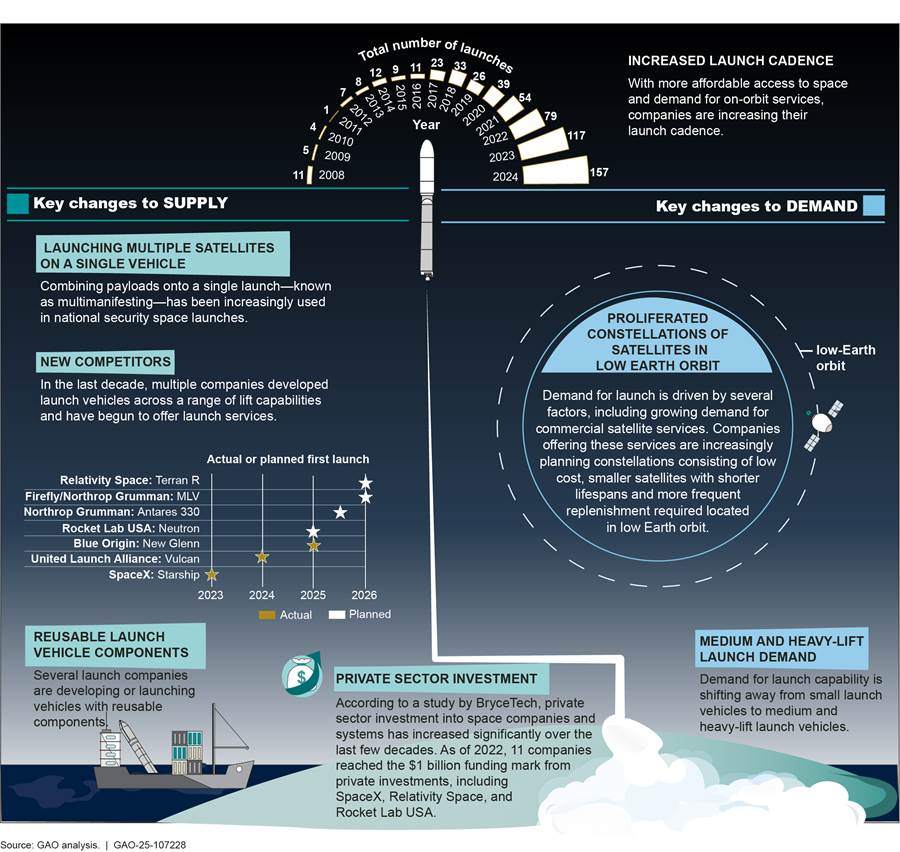

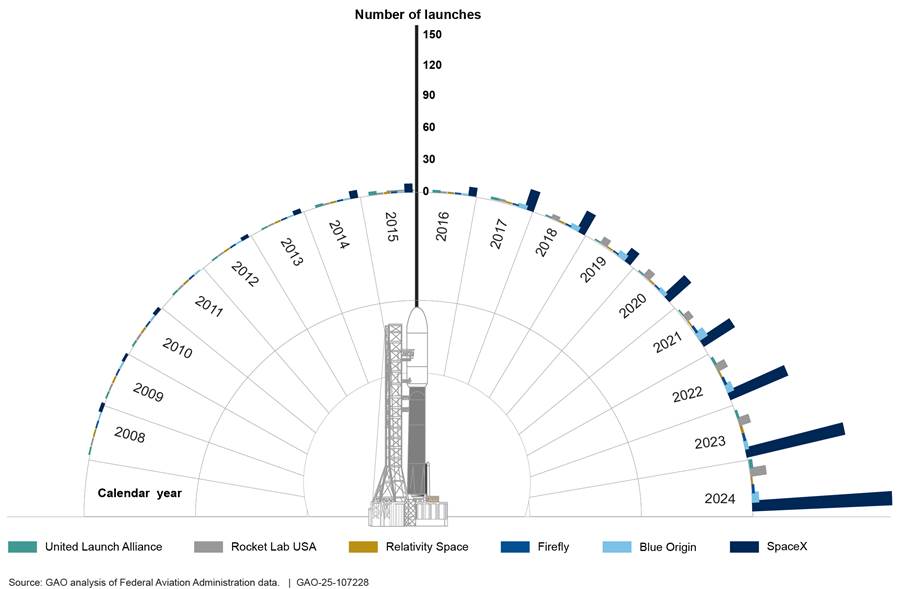

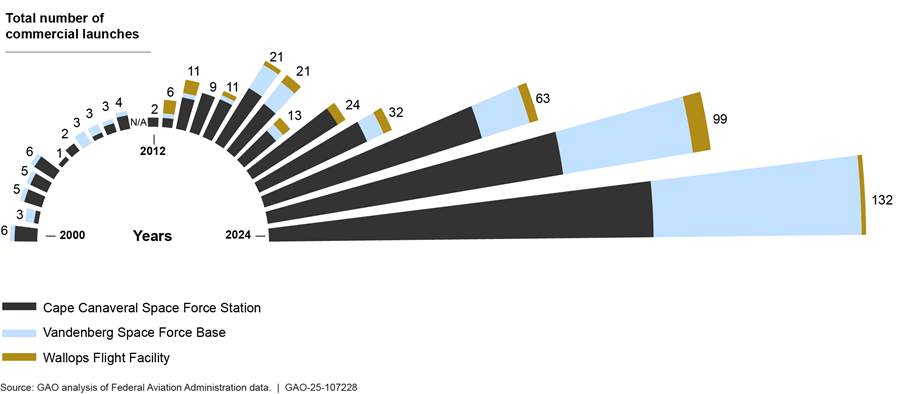

A vast increase in launches over the last several years was driven by commercial launches. SpaceX’s Starlink—a constellation of satellites intended to provide global, space-based internet service— has been increasing since 2018 and comprises the majority of commercial launches since 2023. See figure 2.

Most space launches in the U.S. originate from one of three federally operated launch ranges: Cape Canaveral, Florida; Vandenberg Space Force Base, California; and Wallops Flight Facility, Virginia. The U.S. Space Force operates Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Vandenberg Space Force Base, while NASA operates Wallops Flight Facility. The vast majority of launches last year originated from Cape Canaveral and Vandenberg. More recently, the U.S. has established a launch range in Alaska, but this range did not support a launch in 2024. These ranges are in less populated, coastal locations to provide safe access to necessary orbits. See figure 3.

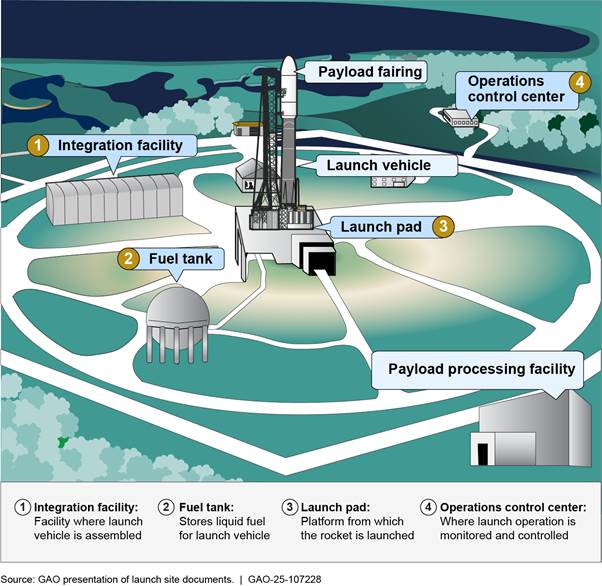

Each launch range has multiple launch complexes that vary in size and capabilities. A launch complex generally includes a launch pad (or pads), fuel tanks, and supporting launch infrastructure, such as integration facilities and operations control centers. Payload processing, also referred to as space vehicle processing, typically occurs outside the launch complex. It is the critical stage in which satellites are encapsulated in the launch vehicle fairing—the protective nosecone—before transport to the launch site and connection to the launch vehicle, which is then transported to the launch pad.[5] See figure 4.

Each launch range supports a mix of government and other uses. The contiguous Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Kennedy Space Center together have over a dozen government-owned launch complexes leased or licensed to eight private companies through a variety of arrangements. For example, NASA uses one of the three pads at Space Launch Complex 39 for its Space Launch System vehicle and leases one of the pads to SpaceX. Several other launch complexes are under consideration for future leasing arrangements. According to Space Force officials, Vandenberg Space Force Base has four launch complexes currently leased or licensed to private companies, with additional space that could be developed and leased. Wallops Flight Facility has five launch complexes and two pads for sounding rockets and hypersonic testing. NASA leases the five launch complexes to the Virginia Space Port Authority.

Private launch service providers locate their operations at federal launch ranges because of strategic locations and the launch support provided at these federally built and operated ranges. Launch providers lease launch complexes from the federal government and typically fund infrastructure at their leased launch complexes, while the federal government funds infrastructure on the surrounding range.[6] The government’s launch infrastructure at the range includes telemetry equipment, radar, command destruct infrastructure, and optical instruments to support launches across the range. Other government-supported infrastructure on the range includes the roads and bridges used to transport equipment—such as the launch vehicle and payload—to the launch pad, as well as electricity, water, and security. Figure 5 depicts a launch complex on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

The Space Force is reimbursed by the launch providers for some of the range support and other launch-related costs it incurs.

· Direct costs include the actual costs, such as salaries of U.S. civilian and contractor support personnel, incurred by DOD as a result of use of its space-related facilities by the U.S. commercial space launch providers. These costs reflect those that would not be borne by DOD in the absence of such use by the U.S. commercial space launch providers.[7] For example, direct costs can include utilities, such as high-pressure water service and electricity, as well as direct civilian labor. DOD has routinely charged launch providers for direct costs.

· Indirect costs include the actual costs of maintaining, operating, upgrading, and modernizing the DOD space-related facility.[8] For example, indirect costs might include the cost to increase security personnel at the gates of the launch range. Since December 2023, the Space Force has had the authority to recoup—under a contract or agreement with commercial entities—a portion of its indirect costs associated with space launch activities on a military installation, such as commercial launches on federal ranges. It began doing so in 2024.[9]

Several federal agencies play key roles in enabling military, civil, and commercial launches. See table 1.

Table 1: Key Federal Launch Organizations That Enable Military, Civil, and Commercial Space Launches

|

Directorate/office |

Role |

|

Department of Defense, U.S. Space Force |

|

|

Space Systems Command (SSC) |

SSC oversees military space acquisitions of satellites and other payloads through its space vehicle program offices. Space vehicle program offices manage the acquisition of space-based capabilities, such as satellite communications, missile warning, tracking, defense, and many more. |

|

Assured Access to Space Directorate (AATS) |

AATS, which reports to SSC, acquires space launch services for U.S. military and intelligence agency satellites through the National Security Space Launch (NSSL) and Rocket Systems Launch program offices. |

|

NSSL and Rocket Systems Launch program offices |

These programs are responsible for compiling launch demand from military and intelligence space vehicle program offices and procuring launch services to meet this demand. Both programs use commercial companies to provide space launch services from federally owned and operated launch ranges. |

|

Launch and Test Range System program/Spaceport of the Future initiative |

This program provides multiple services and systems for its government and commercial customers, such as range safety, launch vehicle tracking, communications, and weather forecasts. Through this effort, the Space Force is transitioning these systems to modernize Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Vandenberg Space Force Base launch ranges. |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) |

|

|

Launch Services program |

This program conducts space launches of its science and exploration projects from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Vandenberg Space Force Base, and Wallops Flight Facility. Additionally, NASA provides infrastructure and range support from its Wallops Flight Facility to multiple customers, including the U.S. Navy, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Federal Aviation Administration, as well as other organizations. |

|

Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) |

|

|

Office of Commercial Space Transportation |

This office generally monitors the commercial space industry through its mission to license and regulate commercial launches and reentries and to investigate mishaps. The FAA’s mission is to license and regulate commercial launch operations to protect public health and safety, the safety of property, and the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States. |

Source: GAO summary of U.S. Space Force, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and Federal Aviation Administration information. | GAO‑25‑107228

Note: Generally, the FAA issues licenses including for (1) a person to launch a launch vehicle or to operate a launch or reentry site, or to reenter a reentry vehicle in the United States; and (2) a citizen of the United States to launch a launch vehicle or to operate a launch site or reentry site, or to reenter a reentry vehicle, outside the United States. 51 U.S.C. § 50904(a)(b).

Recent Innovations in the Launch Market

The launch market—both government and commercial—has changed in several significant ways in recent years. Key innovations highlighted in our interviews with DOD officials include rising levels of private sector investment; increasing numbers of launch companies and a widening array of launch vehicles; the advent of reusable launch vehicle components, such as boosters; and advances in the technology and capabilities of launch vehicles to allow multiple satellites on a single launch. Innovation in the launch industry has coincided and, according to some experts, led to changes in the supply and demand for launch services. Changes in the demand for launch services have included the rise of launches aimed at providing commercial services, such as space-based internet and communications services. See figure 6 for an overview of recent changes in the launch market.

Additionally, according to an independent study, the price of launches has declined sharply over the past several decades. According to this study, as of 2022, the price of heavy launches to low-Earth orbit fell from $11,600 per kilogram in 2004 to $1,500 per kilogram in 2018, an 87 percent decrease.[10]

Commercial launches have quadrupled since 2020 and feature multiple companies. For example, SpaceX and Rocket Lab USA have consistently launched more payloads year after year over this time frame. Blue Origin has continued to launch its New Shepard vehicle. At the same time, Firefly, a relatively new launch provider, began launching its Alpha launch vehicle in 2021. See figure 7.

Demand for commercial launch has been driven by several factors, including growing interest in providing commercial satellite communication services. Companies offering, or seeking to offer, these services are increasingly planning constellations consisting of low-cost, smaller satellites located in low-Earth orbit. These smaller satellites are designed to have shorter lifespans and, thus, need to be replenished more often. SpaceX started launching its Starlink satellites in 2019 and has over 6,750 satellites in orbit, with plans for thousands more. OneWeb, which also provides space-based internet and communications, began deploying its constellation of over 600 low-Earth-orbit-based satellites in 2019. Similarly, Amazon began launching its Kuiper constellation in 2025 and plans to build a constellation of over 3,200 satellites. For these services to continue, the constellations will need to be refreshed with new satellites, which would create recurring demand for launch services.

Additionally, the Space Force and other government entities are pursuing proliferated constellations in low-Earth orbit to increase resilience. For example, the Space Development Agency is developing the Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, which is a proliferated constellation of 300-500 optically linked satellites in low-Earth orbit.[11] This constellation consists of satellites launched roughly every 2 years, beginning in 2023. The National Reconnaissance Office is also developing a proliferated architecture of satellites and began launching those payloads in 2024.

National Security Space Launch Acquisitions

DOD has implemented various strategies over the last 3 decades to foster a competitive launch industry, lower the price of launches, and assure continued access to space for DOD and the intelligence community.[12] It has done so by leveraging the private sector to meet the expected demand for national security space launches. For example, in 1995, DOD awarded launch service contracts to Boeing and Lockheed Martin under its Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle program (now called the NSSL). At the time, market forecasts indicated that demand for commercial launches would be high enough to keep multiple launch providers in business. However, in 2000, updated market forecasts indicated that demand for commercial launches would not materialize. This resulted in the Air Force becoming the majority customer for the two then-dominant launch companies. In 2006, those companies formed a joint venture—ULA—which served as the Air Force’s sole launch provider for a decade.

Since 2013, DOD has used a phased approach to awarding launch contracts. We have reported that the phased approach was intended to increase competition across the launch market, reduce the cost of launches, and provide flexibility to respond to potential geopolitical events.[13] Space Force officials estimated that the phased approach to competition saved $7.1 billion from fiscal years 2012 through 2021 and more than $26 billion over the life cycle of the program.[14] For a timeline of the acquisition phases, see figure 8 and appendix II.

In the acquisition period known as Phase 2, the Space Force competitively awarded 5-year launch service contracts to ULA and a new competitor, SpaceX. These contracts were for approximately 34 launches. In January 2023, SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy successfully launched the first Phase 2 mission. In January and October 2024, ULA’s Vulcan conducted its first and second certification launches, about 4 years later than its original plans.[15] During this delay, ULA continued to launch some satellites using other launch vehicles, and others were launched by SpaceX. The Vulcan launch vehicle was certified for national security space launches in March 2025. At the time of our reporting, the Vulcan had not yet launched any national security space missions.

In 2023, the NSSL program designed an acquisition strategy—Phase 3—that is intended to leverage emerging providers, avoid reliance on a single provider, and assure access to space for DOD’s most critical satellites. DOD began awarding contracts for Phase 3 in June 2024.

Phase 3 Strategy Aims to Enhance Competition and Government Buying Power to Meet Anticipated Space Launch Needs

Under its Phase 3 acquisition strategy, the NSSL program established a “dual lane” contracting approach to enhance competition and tailor risk management. The strategy seeks to further enhance government buying power by limiting launch acquisitions for other space vehicle program offices. Furthermore, the strategy was designed in light of the increasing variety of potential launch providers to meet DOD’s demand for launch services. In creating the Phase 3 strategy, DOD relied on lessons learned from prior acquisition phases, as well as independent market research and feedback from industry.

DOD’s Phase 3 Acquisition Strategy Establishes Two Lanes Intended to Enhance Competition and Tailor Risk Management

The NSSL program established a “dual lane” contracting approach under its Phase 3 acquisition strategy to enhance competition and tailor risk management. Lane 1 is intended to foster competition by facilitating the entry of new providers that are allowed to compete for missions with less stringent requirements. Lane 2 is intended to ensure that DOD’s core needs for its highest-value payloads can be met by providers that have met the full set of mission assurance requirements.

Lane 1 Is Intended to Facilitate New Providers, While Accepting Less Mission Assurance

Lane 1 is intended to facilitate the entry of newer launch providers to the NSSL launch business. The NSSL program allows these providers to demonstrate a subset of the full certification requirements as they compete for launches of payloads with less stringent requirements. For example, Lane 1 providers are required to demonstrate only one successful launch before the award of a task order.

In addition, NSSL implemented a tiered set of mission assurance requirements for Lane 1 providers intended to balance costs and risks. Mission assurance refers to the collection of activities undertaken throughout the life cycle of a launch vehicle development program, through launch, to assure mission success and safety. It can include activities such as prelaunch readiness reviews and launch vehicle hardware and software verification. Lane 1 providers are required to complete mission assurance activities commensurate with the risk level of the payload they are awarded.

· Tier 0: No mission-specific mission assurance; public safety review only, which can be conducted by the FAA

· Tier 1: Minimal mission assurance; limited review of contractor data and processes

· Tier 2: Some mission assurance; selective review of contractor data and processes

· Tier 3: Moderate mission assurance; review of contractor data and processes; targeted independent verification and validation based on identified risks

Further, the NSSL program will reopen competitions for the Phase 3 Lane 1 multiple award, indefinite delivery contract on a yearly basis to potentially on-ramp new indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contract holders to the vendor pool. See table 2 for a summary of the Lane 1 acquisition strategy.

Table 2: Summary of the Space Force’s Phase 3 Lane 1 National Security Space Launch Acquisition Strategy

|

Number of missions |

Approximately 31 |

|

Contract type |

Multiple award indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contractsa (multiple providers compete for task orders) |

|

Ordering period |

5-year base, with 5-year option ordering period |

|

Period of performance |

Multiple years |

|

Number of launch providers |

Multiple launch providers; Lane 2 providers eligible to compete for Lane 1 competitions |

|

On-ramp opportunities |

Annual for new launch provider or system |

|

Mission assuranceb |

Tiered (i.e., commensurate with the risk level of the payload) |

Source: GAO presentation of U.S. Space Force information. | GAO‑25‑107228

aIndefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contracts are awarded to one or more contractors when the exact quantities and timing for products or services are not known at the time of award.

bMission assurance is the comprehensive collection of activities undertaken throughout the life cycle of a launch vehicle development program, through launch, to assure mission success and safety. It can include activities such as prelaunch readiness reviews, launch vehicle hardware and software verification, and pedigree reviews.

In March 2025, the Space Force awarded firm-fixed-price, indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity National Security Space Launch Phase 3 Lane 1 contracts to Rocket Lab USA, Inc., and Stoke Space. These providers joined Blue Origin, SpaceX, and ULA, which were on-ramped to Lane 1 in 2024. Rocket Lab and Stoke Space will each receive a $5 million firm-fixed-price task order to conduct initial capabilities assessments and develop their approach to tailored mission assurance. Once Rocket Lab and Stoke Space complete their first successful launch, they will be eligible to compete for launch service task orders on Lane 1, according to a Space Force announcement.

Lane 2 Is Intended to Meet Core DOD Needs for Highest-Value Payloads

Lane 2 is intended to maintain assured access to space for critical payloads by providing a path for the most mature launch providers to compete to launch NSSL’s most critical payloads. Launch providers in Lane 2 are required to have met the full set of national security space launch certification requirements by October 1, 2026. For example, Lane 2 providers are required to demonstrate a minimum of two consecutive successful launches before being eligible to launch payloads, as compared with the single launch requirement for Lane 1. Additionally, Lane 2 providers are subject to full mission assurance, including a comprehensive review of contractor data and processes and a full independent verification and validation process.[16] See table 3.

Table 3: Summary of the Space Force’s Phase 3 Lane 2 National Security Space Launch Acquisition Strategy

|

Number of missions |

Approximately 54 |

|

Contract type |

Indefinite delivery (requirements) contracts (firm-fixed-price)a |

|

Ordering period |

5-year base (fiscal years 2025-2029) |

|

Period of performance |

Basic contract award has 5-year ordering period; performance under task orders may extend up to 3 years beyond the ordering period |

|

Number of launch providers |

3 |

|

On-ramp opportunities |

None in Phase 3 ordering period |

|

Mission assuranceb |

Full |

Source: GAO presentation of U.S. Space Force information. | GAO‑25‑107228

aIndefinite delivery (requirements) contracts are awarded to one or more contractors when the exact quantities and timing for products or services are not known at the time of award.

bMission assurance is the comprehensive collection of activities undertaken throughout the life cycle of a launch vehicle development program, through launch, to assure mission success and safety. It can include activities such as prelaunch readiness reviews, launch vehicle hardware and software verification, and pedigree reviews.

In April 2025, DOD officials reported that they awarded Blue Origin, SpaceX, and ULA firm-fixed-price, indefinite-delivery (requirements) contracts for the NSSL Phase 3 Lane 2 launch service procurement.

· SpaceX received a $5.9 billion contract award for 28 launches.

· ULA received a $5.4 billion contract award for 19 launches.

· Blue Origin received a $2.4 billion contract award for a total of seven launches.

These contracts provide launch services, mission unique services, special studies, launch service support, and early integration studies/mission analysis, among other items. Lane 2 offerors are required to complete certification by October 1, 2026.

DOD intends for the Phase 3 strategy to protect the government’s interests if one or more launch providers fail to deliver launch vehicles. For example, NSSL is allowing a wider array of new entrants via Lane 1 and three established providers in Lane 2. Additionally, the strategy allows Lane 2 providers to compete for launches in Lane 1. Furthermore, a larger pool of potential providers is expected to help protect the government’s interests by maintaining a competitive environment if providers begin to consolidate as market forces evolve in the coming years.

Phase 3 Acquisition Strategy Aims to Enhance Buying Power and Provide Long-Term Flexibility for Future Needs

New Strategy Seeks to Enhance Government Buying Power by Limiting Outside Launch Acquisitions

DOD intends to further strengthen government buying power through the Phase 3 strategy by limiting “delivery-on-orbit” acquisitions. Delivery-on-orbit acquisitions are those where the government’s space vehicle program offices acquire launch services directly under a separate contract, rather than through NSSL’s contracts.[17] According to NSSL officials, in previous acquisition phases, some space vehicle program offices—including the National Reconnaissance Office and Space Development Agency—had acquired launch services via delivery-on-orbit contracts. NSSL officials told us that these types of acquisitions dilute the government’s buying power by weakening the potential for economies of scale for NSSL launch services.[18] Officials said they believe the program can reduce the costs of individual launches by consolidating the government’s purchases of launch services (i.e., by procuring them on behalf of DOD rather than individual DOD entities procuring their own launches). Consistent with this approach, in October 2024, DOD awarded the first two task orders under Lane 1 of the Phase 3 strategy for seven Space Development Agency launches and several missions for the National Reconnaissance Office.

New Strategy Aims to Leverage Launch Supply Options to Meet DOD’s Evolving Launch Demand

The Phase 3 strategy is intended to foster a varied launch market, which would allow DOD to leverage the availability of more launch providers to keep pace with its expected needs. Examples of these needs include

· more launches overall. DOD anticipates about 85 launches over the next 5 years (2025-2029). This is an increase from 40 launches over the previous 5 years;

· more launches to less challenging orbits. DOD expects to increasingly procure launch services for payloads to less challenging orbits. These could be addressed by small launch vehicles or multimanifesting missions on larger launch vehicles.[19] Specifically, from fiscal years 2025 to 2029, about one-third of the planned national security launches are to low-Earth orbit, which is less challenging to reach. Low-Earth orbit is generally the point of entry for new launch providers, as smaller launch vehicles can more easily achieve it, and payloads placed in this orbit are usually less expensive and less complex. As these launch providers gain experience and demonstrate successful launches, they are expected to gradually develop launch vehicles that can achieve the more challenging orbits;

· continued launches to challenging orbits. DOD will also continue to procure launch services for its most critical satellites to more challenging orbits. From fiscal years 2025 to 2029, more than half of the planned national security launches are to the more challenging orbits (i.e., medium-Earth orbit and geosynchronous-Earth orbit); and

· addressing complex missions. The Phase 3 strategy can also help ensure that DOD can leverage launch providers that can address complex, mission-specific needs. These needs include classified payloads with unique security requirements and multimanifested missions.

Other NSSL needs include tactically responsive launch. This refers to an end-to-end launch capability that can be called upon to rapidly plan and launch a national security satellite to respond quickly to adversary aggression. For example, this might include replacement of a satellite that was attacked. DOD officials stated that maintaining tactically responsive launch capability is a priority. Several potential launch providers we interviewed expressed concern about unclear and inconsistent demand for tactically responsive launches, but DOD officials said the Phase 3 acquisition strategy will be able to address these needs. Specifically, DOD officials said these needs can likely be addressed by the wider array of new launch providers available to DOD via Lane 1.

DOD Incorporated Historical Lessons Learned, Market Research, and Industry Feedback to Develop Its Phase 3 Strategy

To develop its Phase 3 strategy, DOD relied on historical lessons learned, market research, and industry feedback.

Historical lessons learned. DOD built upon lessons learned from prior acquisition approaches. For example, in Phase 1, DOD awarded a sole-source contract to ULA, the only certified provider at that time. As a result, DOD did not benefit from the potential of competitive pricing from multiple providers. In Phase 2, to increase competition and reduce pricing, the NSSL program awarded contracts to two providers, ULA and SpaceX, over a 5-year block buy. In developing the Phase 3 strategy, the emerging maturity of a broader commercial market has afforded DOD the opportunity to leverage this potential to reduce pricing, expand launch capacity, and increase resiliency.

DOD officials told us they also considered the historical delays experienced by launch providers in developing and certifying new launch vehicles. For example, as previously noted, the first flight of ULA’s Vulcan launch vehicle was about 4 years later than initially planned. DOD considered this in developing a strategy that allows new indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contract holders to compete for launch task award orders but minimizes reliance on providers that have not yet proven their launch vehicles. For example, under the Phase 3 Lane 1 acquisition strategy, the indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contract award requires offerors to have a credible path to launch within 12 months of the task order proposal due date. Offerors are required to demonstrate one successful launch for a launch services task order award. Lane 2 offerors are required to complete certification by October 1, 2026.

Market research. DOD commissioned market research on expected launch demand and availability of emerging launch service providers from several independent entities. According to this research, by 2028, approximately nine U.S. launch providers may be able to produce vehicles capable of reaching one or more of the orbits required for national security space launches. Space Force officials also held discussions with space vehicle program offices to understand their demand for launch services.

Industry feedback. DOD officials told us they solicited industry feedback in multiple ways. For example, they held discussions with launch providers and hosted industry day events. In addition, DOD considered feedback it solicited and received from 13 potential launch vehicle providers on its two draft requests for proposal. In response to this feedback, DOD reported that it accepted, partially accepted, or clarified requirements in response to most of the comments received from industry respondents.

DOD Is Addressing Launch Infrastructure Challenges but Also Faces Issues Recouping Costs and Improving Payload Processing Capabilities

DOD is facing challenges related to its launch infrastructure and logistics that it is working to address. It is also facing challenges as it calculates and collects direct and indirect cost reimbursements from commercial entities that use federal launch ranges. Addressing these challenges could help DOD recoup millions from these entities, but it also faces limitations in spending these funds. Furthermore, DOD faces challenges with payload processing capacity and lacks the insight it needs into commercial processing schedules to effectively coordinate processing schedules across its space vehicle program offices.

DOD Is Facing Challenges Related to Launch Infrastructure and Logistics That It Is Working to Address

Launch Infrastructure and Logistical Challenges

Over the last decade, the facilities and related infrastructure at federal launch ranges have become increasingly strained, as companies conduct significantly more commercial launches than the ranges have historically supported. Figure 9 illustrates the significant growth of these launches.

Federal launch infrastructure is aging and, in general, was not designed to accommodate high launch cadence, larger launch vehicles, or the logistics of modern launches. Some effects of higher launch cadence and larger launch vehicles include strained utility and road systems and complex logistics of moving oversized vehicles.

· Strained utility and road systems. According to range officials at both Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Vandenberg Space Force Base, utilities that deliver water, power, and other commodities are increasingly strained as more launches occur. For example, wastewater treatment systems were not built to accommodate the volume of water that sprays the launch vehicle during liftoff to mitigate noise and heat impacts, known as the launch vehicle deluge system. Additionally, launch range personnel are conducting more maintenance and repairs than previously required on critical infrastructure across the range, including roads, bridges, and power systems. For example, Space Force officials told us that as launch providers develop and build their launch pads, the construction equipment puts wear and tear on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station’s infrastructure. Ongoing construction at launch pads has resulted in Cape Canaveral Space Force Station personnel making road and other repairs monthly, rather than quarterly. The Space Force funds these additional repairs.

· Complex logistics of moving oversized vehicles. Determining the logistics of moving oversized vehicles is highly complex. For example, Space Force officials told us that Blue Origin’s New Glenn launch vehicle is too large to cross one of the primary bridges—the most direct route to the launch site—from Kennedy Space Center onto Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. As a result, company personnel must take a much longer route around Cape Canaveral Space Force Station to their launch site, which causes congestion for other operations on the range. Moving launch vehicles around the range blocks traffic—as many current roads can only accommodate one launch vehicle at a time—and can result in safety issues. For example, according to Space Force documentation, ULA’s Vulcan launch vehicle requires a minimum of five oversized moves around Cape Canaveral Space Force Station to get to the launch pad.[20] This is due, in part, to the size of the vehicle and existing roadways on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. Moreover, in a 2023 review of ground transportation impacts on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, the Space Force found at least six incidents where transporting components of the launch vehicles caused safety or traffic issues. These incidents included near-miss collisions with infrastructure at the launch pad, boosters stuck on roads or at turns, payloads hitting above-ground powerlines, and explosives being transported unsafely.

Launch vehicle innovations, such as reusable components and new propellant types, have also led to challenges on launch ranges.

· Reusable components. Reusable launch vehicle components, combined with increased launch cadence, have contributed to the increase in operation and maintenance costs, road wear and tear, and increased demand for security. These reusable components significantly help bring down launch costs, which benefits the government as well as commercial activity in space, but they also strain range resources and cause additional logistical challenges. For example, SpaceX currently reuses Falcon 9 boosters and fairings. After each launch, SpaceX lands many of its boosters on barges in the ocean and then transports them from the nearby port to the range for refurbishment and reuse. According to Space Force documentation, the Falcon 9 requires a minimum of 10 oversized moves to recover the reusable components and refurbish them for launch. Figure 10 shows a used Falcon 9 booster being transported on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

· New propellant types. Launch vehicles using new propellant types also contribute to logistical challenges at the federal ranges. Some launch providers use, or plan to use, novel propellant types that require larger clearance zones—areas that must be cleared of personnel for safety—on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.[21] This could affect the operation of other activities on the range, including those of other launch providers. Specifically, five launch vehicles currently under development plan to use liquid oxygen and liquid methane (LOX-methane) to provide more efficient and powerful lift capability than liquid oxygen and kerosene-based fuel.[22]

The uncertainty associated with clearance zones for launches using LOX-methane propellant contributes to logistical challenges on the range. According to FAA documentation, formulas for calculating, modelling, and establishing LOX-methane clearance zones do not yet exist, as there is significant uncertainty over the explosive yield, if an explosion were to occur. As a result, launch operators are required to clear large areas on the range for launches using combinations of LOX-methane as propellant. Launch providers we spoke with expressed concern that the large size of the clearance zones during launches using these propellant types will effectively halt neighboring range operations during a launch.[23] Space Force officials added that FAA licensing requirements to protect neighboring facilities and critical assets on the launch range—known as resource protection requirements—create logistical challenges and limit launch availability.[24] The officials said that these requirements particularly affect small and medium launch providers that need more launch opportunities to demonstrate their reliability.

Efforts to Address Launch Infrastructure and Logistical Challenges

DOD has multiple efforts underway to address some of the challenges related to launch infrastructure and logistics. DOD officials said that current and planned efforts to mitigate congestion and increase efficiency at the launch ranges allow them to address short-term capability concerns. However, they noted that infrastructure investments and logistical changes are necessary to ensure the continued function of the launch ranges into the future—especially with launch cadences expected to continue to increase and infrastructure needing more frequent repairs. Table 4 summarizes DOD’s efforts to address launch infrastructure challenges.

|

Effort |

Funding |

Details or purpose of effort |

|

Spaceports of the Future infrastructure projects |

$1.4 billion |

Projects across both Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Vandenberg Space Force Base include funding for lift stations, weather towers, wastewater systems, roads, and other improvements. These projects also include upgrading communications networks; procuring support to meet increased launch capacity and cadence requirements; and digitally transforming sensors and systems that provide data, video, and communications for command and control of launch operations. The Space Force started planning and implementing these projects and expects them to continue into the 2030s. The Rocket System Launch program (RSLP) executes infrastructure improvements at Wallops Flight Facility and the Pacific Spaceport Complex - Alaska to increase the military’s future use of these ranges. RSLP received $96.3 million from fiscal years 2017 to 2024 and invested these funds equally at these two sites. |

|

Establishing Mission Development zones on ranges |

$800 million |

Move administrative buildings farther from launch pads to accommodate larger clearance zones and to avoid evacuating the associated personnel during launches. |

|

Revising transportation policies on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station |

Not applicable |

Avoid hazardous situations and blocked traffic and create more efficient pathways for launch vehicles. |

Source: GAO summary of U.S. Space Force information. | GAO‑25‑107228

In addition to these projects, the Space Force has taken steps to increase launch capacity and reduce demand for time-intensive activities across Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Vandenberg Space Force Base. For example, Space Force officials stated they began requiring launch providers to use autonomous flight termination technology on their launch vehicles, which reduced the demand for government resources to support launches.[25] As a result, range personnel reduced the time it takes to reset the launch pad and range resources between launches from 3 days down to approximately 9 hours. Additionally, Space Force officials noted that they accommodated two launches in a 12-hour time frame 10 times in the past year.

NASA is also taking steps to advance DOD and commercial launch capability at Wallops Flight Facility for small-to-medium launches, which has the potential to alleviate some of the space and logistics constraints at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and Kennedy Space Center.[26] For example, several launch providers are developing medium lift vehicles to conduct national security launches from Wallops Flight Facility.[27] Additionally, NASA officials told us they expect an increase in commercial small and medium launch demand through 2030. To accommodate this demand, increase efficiency at the range, and lower costs, NASA developed lessons learned with Rocket Lab USA for more efficient launch processes. NASA also developed the NASA Autonomous Flight Termination Unit at Wallops to reduce the cost and use of range infrastructure and operations. NASA officials told us they are working with Cape Canaveral Space Force Station personnel to assess consistency across scheduling systems at both ranges. They are also communicating best practices for launch operations, safety processes, and other areas of collaboration to increase their capability and launch efficiency.

Finally, the Space Force and other agencies are taking steps to address uncertainties related to LOX-methane propellants. A multiagency team consisting of FAA, Space Force, and NASA representatives is currently coordinating additional research on the explosive effects of LOX-methane propellant combinations. This research intends to ensure consistent safety determinations that will accurately provide launch criteria for public safety. As commercial launches have significantly increased since 2016, so have mishaps involving catastrophic launch explosions or system failures in flight.[28] In commercial space transportation, mishaps are an expected part of the industry’s development as launch providers develop new designs and gain experience.[29]

DOD Could Collect Millions in Direct Costs from Commercial Entities for Use of Federal Launch Ranges, but Faces Challenges

The Space Force collects direct and indirect cost reimbursements from commercial entities that use federal launch ranges. However, the Space Force faces challenges in its efforts to calculate and collect direct costs. We found that better capturing direct costs could help the Space Force recoup millions in indirect costs. However, the statutory cap on indirect cost reimbursements limits the amount the Space Force can collect through fiscal year 2026.

Direct and Indirect Cost Reimbursements

The Space Force collects direct cost reimbursements from commercial entities for providing them with reimbursable support services at federal launch ranges.[30] In the last 5 years, DOD issued several policies or memorandums to ensure that it is recouping its direct costs for providing commercial launch support services.[31] On June 19, 2020, the Acting Secretary of Defense issued a memorandum, Reimbursable Activities in Support of Other Entities, outlining the requirement to no longer provide nonreimbursable support of any nature to other federal, state, territorial, tribal, or private groups or organizations; foreign governments; and international organizations, unless required by statute or authorized but not required by statute. This memorandum was later incorporated into the DOD Financial Management Regulation, which now requires DOD components to obtain reimbursement from other DOD organizations, other federal agencies, and the public for direct civilian labor costs when performing a service or providing materials to another entity.[32]

More recently, a law requires the Space Force to include a specific provision in a contract or other transaction with a commercial entity.[33] This provision requires the commercial entity to reimburse DOD for all direct costs to the U.S. that are associated with any good, service, or equipment provided to the commercial entity under the contract or other transaction.

Section 1603 of the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024 also authorized the Space Force to collect a limited amount of indirect cost reimbursements from commercial entities for providing them with launch support services.[34] Indirect costs include the actual costs of maintaining, operating, upgrading, and modernizing the DOD space-related facilities. Until this law was implemented, the Space Force could not be reimbursed for indirect costs. Section 1603 of the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024 stated that DOD may include a provision in a contract or other transaction with a commercial entity that requires the commercial entity to reimburse DOD for indirect costs as the Secretary considers to be appropriate.[35] The contract or other transaction may provide for the reimbursement of indirect costs by establishing a rate, fixed price, or similar mechanism that the Secretary concerned determines is reasonable.

Space Force officials told us that, because of this authorization, they began charging indirect costs to commercial space launch entities at a rate of 30 percent of direct costs, the most allowed by statute, beginning in June 2024.

The Space Force Faces Challenges Calculating and Collecting Direct Costs

The Space Force faces several challenges in calculating and collecting direct cost reimbursements from commercial entities.

· Full direct costs are unknown. According to Space Force officials, the Space Force does not know the full costs associated with providing space launch support services for commercial launches. This is because (1) previous support contracts did not track direct costs by launch, and (2) the nature of the support the Space Force provides has changed as technology has changed. Space Force officials said that they plan to include improved direct cost calculation and tracking methodologies as task orders under the planned award of the Space Force Range indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contract. Officials stated that the new Space Force Range support contract would include methodologies to track costs, whether providers are conducting launches for government customers or commercial customers. This would allow officials to better understand the costs incurred from commercial launches and better characterize costs per launch. The Space Force reported that it awarded this contract in May 2025.[36] Officials also said that new technology modernized many range assets and that government and contractor labor have been reduced. At the same time, commercial launch service providers have modernized their launch vehicles to minimize or even eliminate the need for the most labor-intensive range assets. Officials told us that currently, commercial launch providers continue to rely on range communications and weather systems that operate 24/7 with little direct labor.

· Billing for direct costs has been uneven. The Space Force has struggled to fully estimate and bill commercial entities for the direct costs of providing them space launch support services. In October 2022, the Air Force Audit Agency found that the Space Force had an opportunity to increase direct cost reimbursements for providing range support services to providers conducting commercial launches.[37] The audit also found deficiencies in the Space Force’s billing and oversight of direct cost reimbursements.[38] For example, it found that the Space Force could increase its direct cost reimbursements for space launch support by $4.2 million annually and $25 million over 6 years by improving its billing processes and oversight. Further, the audit found that the Space Force did not bill either SpaceX or ULA for high-pressure water production at the launch pads in fiscal year 2021—even though it had guidance stating that commercial customers should be charged the basic costs to purchase and produce a utility. The audit also found that the Space Force provided nearly $2 million in booster and rocket storage services but only billed about half of its costs for providing those services.

The audit identified several reasons that the Space Force underbilled for range support services. These reasons included Space Force noncompliance with Air Force guidance and a lack of reimbursement methodologies, oversight, and higher-level guidance. The audit found that the DOD Financial Management Regulation lacked clear guidance to accurately bill reimbursable customers. The Space Force, in coordination with the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense Comptroller, aims to update DOD’s Financial Management Regulation, which provides reimbursement policy for the provision of DOD support to U.S. commercial space activities. According to Space Force officials, these updates will include process adjustments to increase the accuracy of collecting reimbursements and will clarify how to calculate direct costs. According to the Space Force’s corrective action plan, efforts to address the findings of the audit are taking longer than expected and depend on these updates to the Financial Management Regulation, which have not yet been made.

Taking steps to address billing deficiencies and to develop a robust methodology for capturing all direct costs to commercial providers as they are incurred is important. Doing so may allow DOD to recoup what it spends to support commercial launches and help address repairs and improvements to launch infrastructure.

Better Capturing Direct Costs Could Help the Space Force Collect Millions in Indirect Costs

If the Space Force better calculates and collects direct costs associated with providing commercial launch support services, it has an opportunity to recoup millions of dollars by calculating and collecting the associated indirect costs, within statutory limitations. Section 1603 of the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024 limits the amount of indirect costs in a commercial entity’s contract or other transaction that are reimbursable to not more than 30 percent, not to exceed $5 million annually, of all the direct costs that were reimbursed in each of the fiscal years 2024, 2025, and 2026. After fiscal year 2026, DOD may change how it calculates indirect costs as a rate or percentage of direct costs and without the $5 million annual cap.[39]

Under the new authority, the Space Force estimated it can expect to collect as much as nearly $16 million per year from indirect cost reimbursements in the next 2 fiscal years (2025 and 2026). See table 5 for estimated direct and indirect cost reimbursements for fiscal years 2025 and 2026.[40]

Table 5: Estimated Reimbursements for Space Force Commercial Launch Support Services, Fiscal Years 2025-2026

|

Fiscal year |

Space Force estimated direct cost reimbursements |

Space Force estimated indirect cost reimbursements |

|

2025 |

$58,278,412 |

$14,476,015 |

|

2026 |

$88,688,885 |

$15,959,188 |

|

Total |

$147 million |

$30 million |

Source: GAO analysis of Space Force data. | GAO‑25‑107228

Note: By law, the Space Force can be reimbursed for indirect costs of no more than 30 percent, not to exceed $5 million annually, of all the direct costs from a commercial launch entity. National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, Pub. L. No. 118-31, § 1603 (codified at 10 U.S.C. § 2276a). Space Force estimates and subsequent calculations may change, depending on several factors, including the actual number of commercial launches conducted, technology, and changes to statutory authority and limitations.

Because commercial launches are expected to increase in the future, the Space Force could expect to collect an increasing amount in both direct and indirect cost reimbursements. Therefore, the 2022 audit findings—that the Space Force underestimates its actual direct costs and needs a better methodology for capturing those costs—could become relevant. Capturing more direct costs could increase the amount of indirect cost reimbursements that the Space Force can collect.

Statutory Reimbursement Cap Limits Indirect Cost Collection Through Fiscal Year 2026

We found that the statutory reimbursement cap will result in some commercial entities receiving DOD launch range support without reimbursing DOD for those indirect costs for fiscal years 2024 through 2026. According to officials we spoke with and Air Force guidance, the intent of collecting indirect costs is to increase launch capacity and get reimbursed for costs from the providers that are currently benefiting, or will in the future benefit, from launching at the federal range.[41] But, officials told us they estimate that commercial entities with high numbers of commercial launches will hit the statutory $5 million reimbursement cap more quickly than providers that launch less frequently. After a provider with more frequent launches hits the $5 million cap, the Space Force will no longer be recouping its indirect costs for providing range support services. This will limit the reimbursements to DOD, even though providers are still using DOD facilities past the time the reimbursements are capped. For example, we analyzed the actual direct cost reimbursements that the Space Force collected beginning in June of fiscal year 2024. We found that SpaceX would have hit and exceeded the $5 million cap in fiscal year 2024 had the Space Force been collecting indirect reimbursements for the entire year.[42] Moreover, Space Force estimates show that the indirect costs of two providers—SpaceX and ULA—will exceed the $5 million cap in fiscal years 2025 and 2026.

The Space Force is assessing the effects of the statutory reimbursement cap, including how the cap affects indirect cost recoupment, over the next several fiscal years. For example, the Space Force estimates that without the $5 million cap on indirect costs, it could collect nearly $3 million more in fiscal year 2025 and approximately $11 million more in fiscal year 2026.

Section 1603 of the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2024 requires the Secretary of each military department to prescribe regulations on carrying out the authority to collect indirect cost reimbursements.[43] Space Force officials told us they are in the process of developing these regulations and implementing lessons learned from the first year of collecting indirect reimbursements. The Space Force is assessing the statutory cap on indirect cost reimbursements—which is set to expire at the end of fiscal year 2026—and report its findings to the congressional defense committees.[44] The Secretary of the Air Force approved the memorandum for authorization to collect associated indirect cost to direct cost from commercial space launch entities on June 7, 2024, and will revise the regulations with Space Systems Command and the Defense Secretary. There is not enough information for us to evaluate the agency’s implementation at this time. DOD is still in the process of addressing its cost reimbursement calculations and collection methods within the requirements of the existing statute.

The Space Force Is Limited in Spending Collected Funds

The Space Force is limited in spending the reimbursements it collects from commercial entities for goods, services, or equipment provided to them due to statutory restrictions. The law requiring a military department to be reimbursed for direct costs and authorizing the collection of indirect costs from commercial entities for goods, services, or equipment provided to them also requires the agency to credit the reimbursements back to the appropriations account from which the cost is derived. In this case, the reimbursed space launch costs are designated as Operations and Maintenance appropriations, which are available for obligation for 1 year.[45] This means that the Space Force must obligate the direct and indirect cost reimbursements from commercial entities within the fiscal year those funds are available. Space Force officials said that this is a limited amount of time to calculate, collect, and obligate these funds. Space Force guidance on implementing the law states that the Space Force cannot obligate the direct and indirect cost reimbursements it collects each fiscal year past the 1-year period of availability, which officials told us restricts them from funding larger infrastructure investments that would strengthen launch capacity.

The requirement to obligate the direct and indirect cost reimbursements in the same year they are collected is at odds with the Space Force’s ability to improve large-scale and expensive launch infrastructure to enhance its efficiency and cost effectiveness. For example, the Space Force wants to fund larger projects, like building new utility systems, roads, or bridges to accommodate increases in commercial launches and larger vehicles. But, constructing infrastructure such as a bridge that would shorten launch vehicle routes around the range could cost over $100 million and take years to plan and build.

As a result of these limitations, Space Force officials said they are identifying priority small projects and repairs they can fund with the direct and indirect cost reimbursements that will provide common-use benefits to launch service providers. For example, they updated safety software and plan to repair fiberoptics and upgrade launch range security inspection stations.

The agency is currently working with United States Air Force and the Office of the Secretary of Defense to revise the regulatory Financial Management Regulation guidance in accordance with the statutory NDAA language. It is too early to fully assess DOD’s progress, as DOD is still in the process of implementing how it will spend direct cost reimbursements within the requirements of the existing statute.

DOD Faces Payload Processing Challenges, Lacks Insight into Capacity Needs, and Its Coordination Is Fragmented

DOD faces payload processing capacity and complexity challenges. It has efforts underway to address these challenges, but it lacks key insights into commercial payload processing schedules. Additionally, DOD’s coordination of its payload processing schedules is fragmented.

DOD Faces Payload Processing Capacity Challenges

According to Space Force officials, payload processing capacity is the greatest challenge facing DOD’s space launch efforts. As the number and complexity of national security launches increases over the next 5 years, the Space Force expects shortfalls in access to processing bays, a critical resource for conducting these launches.[46] Specifically, Space Force officials said they expect an annual shortfall of up to two processing bays from fiscal years 2026 through 2030.[47] Until now, the Space Force had not experienced significant payload processing shortfalls because demand was relatively low, and delays to payloads or launch vehicles created openings for others in the processing schedule.

According to Space Force officials we spoke with, payload processing shortfalls will be exacerbated as the complexity of national security launches increases. Upcoming national security missions are expected to become more complex as programs increasingly multimanifest payloads on a single launch. Currently, according to Space Force officials, around 70 percent of DOD missions are multimanifested. This results in payloads for a single launch occupying multiple processing bays simultaneously—the payloads have varying security clearance requirements and may require separate processing, support, and storage spaces.

Further, Space Force officials stated that limited processing capacity occurs, in part, because space vehicle programs plan overly lengthy processing timelines. In addition, these programs do not have an incentive to be more efficient. These officials said that historically, space vehicle programs could complete work on the payloads at the processing facility and occupy one or more bays for long periods of time because demand for processing bay space was lower.

Space Force Efforts to Add Payload Processing Capacity Lack Key Insights

The Assured Access to Space Directorate (AATS) is taking steps to increase capacity at payload processing facilities before it has information that may help it use existing capacity more efficiently. Specifically, Space Force officials told us that it plans to make an award of $80 million to increase payload processing capacity at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station and an award of $80 million to increase processing capacity at Vandenberg Space Force Base. In May 2024, AATS issued a solicitation for increased space vehicle (also referred to as payload) processing capacity at both Space Force installations.[48] AATS plans to make awards in spring 2025 at Vandenberg Space Force Base, followed by Cape Canaveral Space Force Station later in fiscal year 2025.

However, the Space Force is limited in using the payload processing capacity it currently has because it lacks insight into commercial payload processing schedules. The Space Force and companies that conduct commercial launches use commercial payload processing providers.[49] Space Force officials said that because the arrangements between these payload processing providers and commercial companies are private, the Space Force cannot integrate that information in its national security mission scheduling. Space Force officials said they need insight into the commercial payload processing schedules through a contract with the payload processing provider. They have not yet issued a solicitation for such a contract but plan to do so after awarding the solicitation for increased capacity.

Under this approach, the Space Force will acquire services to provide additional processing capacity before it has insight into commercial payload processing schedules. Space Force officials stated that they do not plan to award a contract that requires insight into commercial payload processing schedules until after they award a contract to increase capacity later in spring 2025. These officials told us they are focusing their resources on increasing capacity first because they did not have the staff resources to award contracts for both efforts at the same time. The sequencing of these efforts means that the Space Force may be missing opportunities to more efficiently use the capacity it already has.

Prioritizing the issuance of a solicitation that lays out requirements for gaining insight into commercial payload processing schedules could help the Space Force avoid payload processing congestion and capacity shortfalls. It could also save costs related to payloads occupying bays for longer than planned. The Federal Acquisition Regulation requires agencies to perform acquisition planning to ensure that the government meets its needs in the most effective, economical, and timely manner.[50] Gaining insight into commercial processing schedules may allow the Space Force to align national security payload processing schedules more efficiently with the available payload processing capacity to ensure that the government meets its needs in the most effective and economical way. It could also help the Space Force more effectively target its $160 million investment to increase payload processing capacity.

DOD’s Coordination of Payload Processing Schedules Is Fragmented

The Space Force’s efforts to coordinate payload processing across its space vehicle program offices is fragmented. In 2022, an Air Force memorandum stated that the Space Force could no longer afford to suboptimally manage payload processing capacity as it has done in the past.[51] Historically, space vehicle processing for national security launches was managed through arrangements between the space vehicle program offices and the primary payload processing service provider. This resulted in fragmented efforts to coordinate national security payload processing.

The 2022 memorandum directed the Space Force’s Space Systems Command to implement a strategy that would centralize planning for payload processing and scheduling as an enterprise. According to the memorandum, doing so would optimally balance national security space priorities and maximize the use of existing capacity.

As a result of this memorandum, Space Systems Command began implementing several efforts to centralize payload processing:

· It designated the Space Systems Command Launch and Range Operations office, then subsequently AATS, as the “clearinghouse” responsible for planning, scheduling, organizing, prioritizing, coordinating, and deconflicting all aspects of space vehicle processing.

· It directed all space vehicle program offices to work with AATS to arrange for payload processing.

· It established the first formal enterprise management approach to coordinating payload processing across space vehicle program offices within the Space Force. In May 2024, AATS implemented an enterprise management team and enterprise management forum to better coordinate space vehicle payload processing.[52] The Space Force had previously established efforts to coordinate government launch schedules across agencies. However, officials told us that these efforts allowed them to piece together space vehicle program payload processing requirements and schedules but required a multistep process.[53]

Despite these efforts, coordination of national security space payload processing remains fragmented because the Space Force has not yet issued a solicitation to centralize payload processing.[54] The Space Force told us that awarding a contract under this solicitation is a key step to centralizing processing schedules but that it is focusing its resources on expanding processing capacity first. Space Force officials told us that the enterprise management team plans to award an indefinite delivery, indefinite quantity contract after it increases processing capacity. They stated that this contract, when awarded, will enable centralized management and increase coordination and execution of all space vehicle processing requirements. Officials further stated that this would reduce the current fragmented approach they use for managing payload processing for national security missions. Additionally, they stated that this is similar to how launch services are acquired centrally through the NSSL program office.

The Federal Acquisition Regulation requires agencies to perform acquisition planning to ensure that the government meets its needs in the most effective, economical, and timely manner. Without prioritizing the issuance of a contract to centralize processing schedules across space vehicle program offices, the Space Force will not have a tool to ensure effective coordination and use of its existing capacity. Without this tool, fragmentation across space vehicle programs will persist, potentially resulting in increased costs and delays at the processing facility and, ultimately, to critical on-orbit capabilities.

Conclusions

The Phase 3 acquisition strategy continues DOD’s decades-long approach to foster a robust commercial space market and reap benefits from that market through lower prices and access to space for critical national security payloads. The strategy also aims to leverage the significant investment the federal government has made into commercial launch vehicles.