HOMELAND SECURITY

Actions Needed to Address Longstanding Gaps in Human Resources IT

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107233. For more information, contact Kevin Walsh at WalshK@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107233, a report to congressional requesters

Actions Needed to Address Longstanding Gaps in Human Resources IT

Why GAO Did This Study

Since DHS was created in 2002 and merged 22 agencies into one department, its human resources environment has included duplicative systems and paper-based processes. DHS initiated its human resources IT portfolio initiative in 2003 to consolidate and modernize the department’s human resources systems.

GAO was asked to provide an update on DHS’s progress in implementing the portfolio initiative. GAO’s objectives were to, among other things, (1) identify progress in achieving goals, (2) evaluate the extent to which DHS implemented portfolio management practices, and (3) identify any challenges in overseeing shared service providers.

GAO reviewed project documentation to determine actions taken relative to goals; evaluated HRIT portfolio documentation against best practices for portfolio management; compared DHS actions to address their identified challenges to federal requirements; reviewed documents from a key shared service provider (Agriculture) and compared them to federal requirements; and conducted interviews.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making 10 recommendations, including nine to DHS to identify a strategy and goals for HRIT; address remaining portfolio management gaps; and reevaluate options to replace and secure aging systems; and one to Agriculture to renegotiate agreements to enable DHS access to cybersecurity documents. DHS and Agriculture generally concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) started a human resources IT (HRIT) portfolio (a collection of related IT projects) initiative in 2003 to modernize systems. According to the Department’s Inspector General, by 2010 DHS had made limited progress on the initiative. In 2010, the DHS Deputy Secretary announced that the department could no longer sustain a component-based approach for human resource IT. Accordingly, in 2011 DHS announced 15 program goals; most goals were aimed at delivering enterprise-wide solutions.

After nine years of effort from 2011 to 2020 that resulted in not meeting 12 of the 15 goals, DHS refined and replaced the goals with five different goals. However, it discontinued use of those goals in 2022 and further refined and replaced HRIT’s goals with two new draft goals. As of April 2025, these goals remain in draft status. Between 2005 and 2023, GAO estimates that, based on available data, DHS has spent at least $262 million on this initiative.

The lack of progress in achieving its goals is due in part to gaps in DHS’s implementation of six key portfolio management practice areas (see table below). For example, DHS does not have an approved strategy and goals, and lacks cost data for 28 of 49 projects, which prevents fully measuring portfolio performance.

DHS’s Human Resources IT Implementation of Portfolio Management Practices

|

Portfolio management practice area |

GAO rating |

|

Strategic management (e.g. developing a strategic plan) |

◑ |

|

Governance (e.g. developing a portfolio governance board) |

◑ |

|

Capacity and capability management (e.g. allocating resources) |

◑ |

|

Stakeholder engagement (e.g. implementing a stakeholder engagement plan) |

◑ |

|

Performance management (e.g. measuring performance against metrics) |

○ |

|

Risk management (e.g. utilizing a risk register to track portfolio risks) |

◑ |

Legend: ●=Fully implemented ◑=Partially implemented ○=Not implemented

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) human resources IT portfolio documentation against practices defined in Project Management Institute, Inc., The Standard for Portfolio Management – Fourth Edition (Newton Square, PA: 2017). | GAO‑25‑107233

According to DHS officials, they are experiencing two challenges in overseeing federal shared service providers, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture—a provider of payroll, personnel actions, and time and attendance services to DHS.

· DHS has had difficulties in ensuring Agriculture is adhering to federal cybersecurity requirements. Although DHS and others have reported significant cybersecurity concerns with Agriculture systems, they have not been successful in obtaining requested documents from Agriculture. According to DHS officials, they need these documents to comply with their cybersecurity responsibilities under federal requirements and guidance.

· In November 2024, Agriculture finalized a plan to modernize two critical aging mainframe systems that are essential to DHS. However, according to officials, that plan is now on hold as new leadership assesses whether the effort will continue.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

COBOL |

Common Business Oriented Language |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FedRAMP |

Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program |

|

HCBS |

Human Capital Business Solutions |

|

HRIT |

Human Resources IT |

|

ISMS |

Integrated Security Management System |

|

IT |

information technology |

|

NFC |

National Finance Center |

|

OCHCO |

Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer |

|

OCIO |

Office of the Chief Information Officer |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

|

PALMS |

Performance and Learning Management System |

|

PMI |

Project Management Institute |

|

PPS |

Payroll/Personnel System |

|

eOPF |

electronic official personnel file |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 4, 2025

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Shri Thanedar

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations, and Accountability

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Glenn F. Ivey

House of Representatives

Since the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created in 2002 and merged 22 agencies into one department, its human resources environment has been plagued by fragmented systems, duplicative and paper-based processes, and little uniformity in data management practices. According to DHS, these issues have compromised the department’s ability to effectively and efficiently carry out its mission to, among other things, enhance security and respond to disasters. For example, according to DHS, the department’s inefficient and disjointed hiring process has limited the onboarding of appropriately trained, certified, and skilled personnel that can be deployed during emergencies and catastrophic events.

To address these issues, DHS initiated the human resources IT (HRIT) investment in 2003 to consolidate, integrate, and modernize the department’s IT infrastructure that supports human resources. This investment is comprised of a portfolio of projects. For example, one of the projects was intended to implement a centralized learning management system to replace the department’s nine disparate systems. This would enable comprehensive training reporting and analysis across the department.

In February 2016, we reported that DHS had made very little progress in implementing HRIT in the 13 years since it had been initiated.[1] You asked us to provide an update on DHS’s progress in implementing HRIT. Our specific objectives were to (1) identify changes to HRIT strategic goals and progress made in achieving them, (2) evaluate the extent to which DHS implemented portfolio management practices for HRIT, and (3) determine the challenges, if any, DHS has experienced in overseeing shared service providers for key HRIT services and the extent to which DHS has addressed them.

To address the first objective, we reviewed DHS’s blueprint for HRIT to identify the portfolio’s strategic goals. We also reviewed the Human Capital Business Solutions (HCBS) Strategic Plans that were used between 2021 and 2025. We assessed these documents to identify changes in the HRIT strategic goals over time. To describe progress made in achieving goals, we reviewed relevant documentation from the HCBS office (the office responsible for implementing HRIT). This documentation included advisory team meeting minutes, director meeting minutes, project plans, and HRIT strategy documents. We reviewed the documents to assess the actions HCBS had taken relative to HRIT’s goals. Further, we interviewed officials from HCBS to obtain additional information on completed and in-progress projects.

To address the second objective, we reviewed HRIT portfolio documentation, such as strategic plans, portfolio charters, capacity plans, a risk management plan, cost and schedule data, risk registers, and governance board meeting minutes to determine HRIT’s portfolio management activities. We compared these activities against the six portfolio management domains from the Project Management Institute’s (PMI) The Standard for Portfolio Management – Fourth Edition.[2] We supplemented our analysis with interviews with HCBS officials regarding their efforts to implement the portfolio management domains. For each domain, we assessed HCBS’s implementation of our evaluation criteria as:

· fully implemented—HCBS officials provided evidence which showed that it fully or largely addressed the elements of the criteria.

· partially implemented—HCBS officials provided evidence that showed it had addressed at least part of the criteria.

· not implemented—HCBS officials did not provide evidence that it had addressed any part of the criteria.

We assessed the reliability of HRIT project data (e.g. descriptions and status) by reviewing documentation, electronically testing the data for obvious errors and anomalies, and interviewing knowledgeable agency officials. When we found discrepancies (e.g. missing data, duplicate records, or data entry errors), we brought them to DHS’s attention and interviewed portfolio officials to discuss them before conducting our analysis. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of this objective.

We also assessed the reliability of the project cost and schedule data by reviewing the project start dates, planned completion dates, and estimated and actual project costs for each of the projects to determine if there were any missing inputs. We also interviewed portfolio officials to discuss the completeness of the data. We determined that the cost and schedule data were not complete. We discuss the limitations of these data in the report.

For the third objective, we met with agency officials, including from DHS’s HCBS office, Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO), DHS’s nine operational components, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (Agriculture) OCIO, and Agriculture’s National Finance Center (NFC) to identify and discuss key challenges facing DHS’s HRIT portfolio.[3] Through these discussions we identified two challenges related to overseeing shared service providers. We reviewed documentation that provided details on the identified challenges such as an analysis of alternatives, after-action reports, agreements DHS had with its shared service providers, as well as documentation of DHS’s continuous monitoring activities of the security controls of its shared service providers.

We assessed actions DHS officials took to address the related challenges by comparing their actions to federal requirements and guidance. These requirements and guidance include Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Circular A-130[4] and the General Services Administration’s Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP).[5]

A detailed discussion on our objectives, scope, and methodology is provided in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

DHS’s mission is to secure America by preventing and deterring terrorist attacks and protecting against and responding to threats and hazards to the nation, among other things. Created in 2002, DHS merged 22 agencies and offices that specialized in one or more aspects of homeland security. The intent behind the merger was to improve coordination, communication, and information sharing among these multiple federal agencies. Each of these agencies is responsible for specific homeland security missions and for coordinating related efforts with its sibling components.

DHS’s Initial HRIT Consolidation Efforts

To address the many issues facing DHS, it initiated the HRIT portfolio to consolidate, integrate, and modernize the department and its components’ disparate IT infrastructure that supports human resources. DHS initiated HRIT in 2003, but by 2010 had made limited progress on the HRIT investment, as reported by DHS’s Inspector General.[6] This was due to, among other things, limited coordination with, and commitment from, DHS’s components.

In 2010, the Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security issued a memorandum emphasizing that DHS’s wide variety of human resources processes and IT systems inhibited the ability to unify DHS and negatively impacted operating costs. The memorandum stated that, without an enterprise operating model, support for DHS’s core mission was at risk and valuable workforce management information remained difficult to acquire across the department.

Accordingly, the Deputy Secretary stated that DHS could no longer sustain a component-centric approach when acquiring or enhancing human resources systems. In addition, the Deputy Secretary prohibited component spending on enhancements to existing human resources systems or acquisitions of new solutions, unless those expenditures were approved by the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer (OCHCO) or OCIO. The memorandum also directed these offices to develop a department-wide human resources architecture.

In 2011, in response to the Deputy Secretary’s direction, DHS completed an effort called the Human Capital Segment Architecture, which, according to DHS, defined the department’s current (or as-is) state of human capital management processes, technology, data, and relevant personnel. Further, from this current state, the department developed a comprehensive future state (or target state), and a document referred to as the Human Capital Segment Architecture blueprint that redefined the HRIT investment’s scope and implementation time frames.[7]

As part of this architecture effort, DHS conducted a system evaluation and determined that it had many single use solutions developed to respond to a small need or links to enable disparate systems to work together. DHS reported that the numerous, antiquated, and fragmented systems inhibited its ability to perform basic workforce management functions necessary to support mission critical programs. The document stated that the department’s hiring process involved multiple hand-offs which resulted in extra work and prolonged hiring. The numerous systems and hand-offs slowed DHS’s response to emergencies and limited its ability to deploy trained, certified, and skilled personnel.

To address this issue, the blueprint articulated 15 strategic improvement opportunity areas or goals that would comprise HRIT (e.g., enabling seamless, efficient, and transparent end-to-end hiring). The blueprint also outlined 77 associated projects (e.g., deploying a department-wide hiring system, establishing an integrated data repository and reporting mechanism, and developing a centralized learning center) to implement these 15 opportunities. Each opportunity area or goal includes from one to 10 associated projects. Table 1 summarizes the scope of the 15 strategic improvement opportunities—listed in the order of DHS’s assigned priority—and identifies their original planned completion dates as of August 2011 when the blueprint was issued.

Table 1: Scope and Original Planned Implementation Dates for the 15 Strategic Improvement Opportunity Areas, as Outlined in DHS’s August 2011 Human Capital Segment Architecture Blueprint

|

Strategic improvement opportunity area name (number of associated projects) |

Problem and solution approach |

Original planned completion date in Human Capital Segment Architecture Blueprinta |

|

1. Data management and sharing (5) |

Problem: Inability to support enterprise reporting and data quality issues, among other things. Solution approach: Develop, execute, and supervise plans, policies, programs, and processes that control, protect, deliver, and enhance the value of data and information assets. |

September 2014 |

|

2. Performance measures tracking and reporting (3) |

Problem: Enterprise-level performance information not available and lack of standardized performance measures across the components, among other items. Solution approach: Establish ongoing monitoring and reporting of program accomplishments, particularly in the area of progress towards pre-established goals. |

December 2011 |

|

3. Personnel action processing (10) |

Problem: Significant costs associated with maintaining seven different systems for personnel action requests, and loss of efficiency due to duplicative data entry into multiple systems, among other things. Solution approach: Establish the process necessary to appoint, separate, or make other personnel changes, which serve as a foundation for all human resources functions. |

September 2013 |

|

4. Human Resources document management (8) |

Problem: Accessibility challenges and fragmented systems are unable to support new business requirements, among other things. Solution approach: Enable accessibility, work processes, storage, and searchability of case file management contents within human resources activities. |

September 2014 |

|

5. End-to-end hiring (9) |

Problem: Hiring process involves numerous systems and multiple hand-offs, resulting in extra work and delayed hiring, among other things. Solution approach: Establish workforce planning, recruitment, hiring, security and stability, and orientation. |

December 2016 |

|

6. Performance management (3) |

Problem: Portions of performance management are done manually throughout all components, and there is a lack of reporting capabilities and transparency into the performance management process, among other things. Solution approach: Create a process to support the attainment of DHS’s organizational goals by promoting and sustaining a high-performance culture. Accomplished through the issuance of employee performance work plans. |

December 2012 |

|

7. Off-boarding process (1) |

Problem: No standardized approach to offboarding at Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and there are time lags before selected systems recognize that an employee has left DHS, which poses a high risk of security infractions, among other things. Solution approach: Establish a process through which an employee is formally separated from employment in the federal government, including canceling badges, credentials, and passwords, removing the employee from the payroll, and initiating backfill process |

December 2012 |

|

8. Policy issuances and clarification (4) |

Problem: Policies are deployed without fully understanding Human Resources (HR) IT and reporting implications, and components’ participation in policy discussions is not consistent, among other things. Solution approach: Create a process for promulgating new policies and standards to improve compliance and enhance efficiency, as well as streamline and enhance existing policies so that they are clearer and easier to follow. |

June 2015 |

|

9. Payroll action processing (6) |

Problem: Inadequately trained timekeepers negatively impact payroll, and three systems are used to initiate payroll actions, among other things. Solution approach: Establish a process for conducting those actions that impact an employee’s pay, including personnel actions, payroll actions, and timekeeping. |

June 2014 |

|

10. HRIT deployment process (4) |

Problem: Expectations with regard to system requirements and the potential need to customize system solutions do not align with overall delivery related to commercial off-the-shelf products and lack of transparency around project plans and schedules related to overall delivery, among other things. Solution approach: Create a process for the activities DHS’s Human Capital Business Systems unit undertakes to implement enterprise HRIT systems to components, including coordination of initiation and approval processes within DHS governance structures. |

September 2012 |

|

11. Knowledge management (7) |

Problem: No effective enterprise search capability and lack of department-wide visibility of stove-piped content with restricted access, among other things. Solution approach: Establish a solution for capturing, retaining, sharing, and disseminating essential knowledge across DHS’s community of human resources professionals in their respective components. |

December 2014 |

|

12. Training (4) |

Problem: Training varies greatly from component to component, and current junior-level human resources specialists are not as well trained in core human resources skills as their predecessors, among other things. Solution approach: Create a systematic process for teaching employees work-related skills and guiding them to adopt cultural changes. |

June 2015 |

|

13. Communication and collaboration among components (5) |

Problem: Lack of an integrated plan for Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer (OCHCO) communication, and lack of regular communication across DHS, among other things. Solution approach: Establish a process for sharing information in response to data calls, audits, Congressional requests, or the simple requirements of day-to-day business, along with the process of components working together to solve common challenges. |

December 2012 |

|

14. Onboarding process (6) |

Problem: Multiple, duplicative systems used to track onboarding activities and no standardized, automated capability to trigger onboarding activities, among other things. Solution approach: Create a process for the activities that occur from after the conclusion of pre-employment (when security and any necessary medical screenings are completed) to when an official Entrance on Duty date is established and provisioning (ensuring new employees have the tools to do their job) is scheduled. |

December 2012 |

|

15. HRIT intake process (2) |

Problem: No enterprise-wide HRIT governance process for determining whether to pursue a project. Solution approach: Establish an overall governance process to determine project initiation based on business needs, preliminary definition, review, and decision along various defined IT paths. |

December 2011 |

Source: Data provided by DHS. | GAO‑25‑107233

aThese dates reflect the last month of the quarter in which the strategic improvement opportunities were planned to be complete, as identified in the Human Capital Segment Architecture Blueprint.

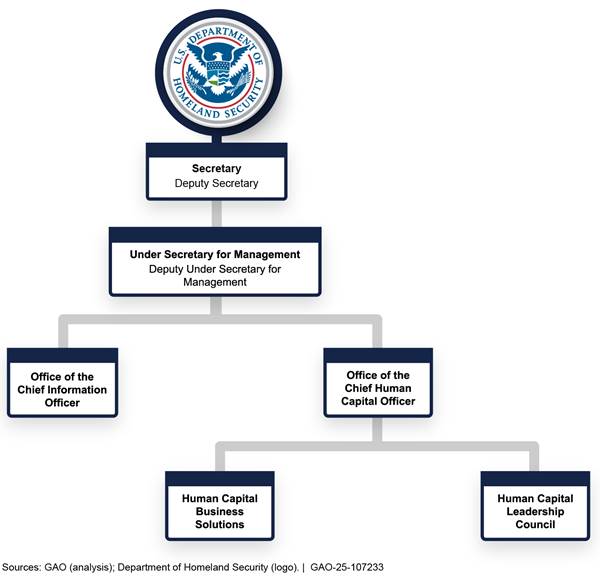

Organizational Structure for Overseeing HRIT

The organization structure for overseeing HRIT includes multiple offices. Specifically, the Department’s Management Directorate is headed by the Under Secretary for Management. Within this directorate are the OCHCO and the OCIO. The OCHCO is responsible for, among other things, department-wide human capital policy, development, planning, and delivering human capital functions. Figure 1 illustrates these functions.

Within OCHCO is HCBS, the portfolio manager responsible for implementing the HRIT portfolio. The Human Capital Leadership Council serves as the governing board for the portfolio. The OCIO is responsible for departmental IT policies, processes, and standards, and ensuring that IT acquisitions comply with DHS IT management processes, among other things. Figure 2 illustrates a simplified organizational structure for overseeing HRIT within DHS.

Figure 2: Simplified Organizational Structure for Overseeing the Human Resources IT (HRIT) Portfolio within the Department of Homeland Security

Between 2005 and 2023, we estimate that DHS obligated at least $262 million for the HRIT program, shown below in Table 2.[8]

Table 2: Department of Homeland Security’s Human Resources IT Obligations (dollars in millions) in Fiscal Years 2005-2023

|

Fiscal Year |

Amount Obligated |

|

2005 |

$36 |

|

2006 |

30 |

|

2007 |

25 |

|

2008 |

0 |

|

2009 |

17 |

|

2010 |

17 |

|

2011 |

17 |

|

2012 |

14 |

|

2013 |

10 |

|

2014 |

8 |

|

2015 |

10 |

|

2016 |

8 |

|

2017 |

4 |

|

2018 |

4 |

|

2019 |

13 |

|

2020 |

12 |

|

2021 |

14 |

|

2022 |

13 |

|

2023 |

10 |

|

Total |

$262 |

Source: GAO analysis of the President’s budgets and

documentation provided by the Department of Homeland Security. | GAO‑25‑107233

GAO Previously Made Recommendations to Improve HRIT Implementation, but Issues Remain

In 2016, we reported that HRIT had made very little progress in implementing the portfolio’s 15 strategic improvement opportunity areas or goals.[9] Specifically, we found that while the vast majority of the areas were to be delivered by June 2015, only one goal had been met, and the completion dates for the other 14 were unknown. In addition, we reported that the department did not effectively manage the HRIT investment. For example, DHS did not update or maintain the HRIT schedule, have a life cycle cost estimate, or track all associated costs. Moreover, the blueprint had not been updated in approximately 4.5 years.

As such, we made 14 recommendations aimed at ensuring the HRIT portfolio received necessary oversight and improved DHS’s learning management system program implementation. Between 2016 and 2020, DHS implemented 11 of the 14 recommendations. For example, DHS updated and maintained the department’s human resources system inventory and approved an updated Human Capital Segment Architecture blueprint.

DHS did not implement three recommendations related to the performance and learning management system. In particular, those recommendations were not implemented because DHS moved the performance and learning management system into an operations and maintenance status in 2017, rather than continue to implement the remaining planned performance management capabilities.

As of September 2024, OCHCO reported that the HRIT environment continued to be disparate, duplicative, inefficient and error prone. Specifically, the office reported that DHS uses more than 80 disparate systems and tools throughout the employee lifecycle (recruitment to separation). Officials reported that due to the complex HRIT portfolio, the department’s more than 260,000 employees continue to have multiple accounts, logins, and passwords. Additionally, officials reported that the portfolio creates redundant work for human resources practitioners and increases the risk of data errors.

Best Practices for Portfolio Management

A portfolio is a collection of projects, programs, and operations managed as a group to achieve strategic objectives. Project Management Institute’s (PMI) Standard for Portfolio Management identifies portfolio management principles that are generally recognized as good practices for organizations to effectively manage complex and intense program and project investments.[10] These include:

· Portfolio strategic management: Develop a portfolio strategic plan, which includes a vision and mission statement, a description of the organization’s long-term portfolio goals and objectives, and the planned means to achieve goals and objectives.

· Portfolio governance: Establish clearly defined governance roles for the portfolio and develop processes and timelines for updating governance documents.

· Portfolio capacity and capability management: Identify, allocate, and optimize resources for maximizing resource utilization and minimizing resource conflicts in portfolio execution. Capacity and capability management in the context of portfolio management applies to all aspects of resources such as staff, capital, technology, equipment, etc.

· Portfolio stakeholder engagement: Identify the stakeholders and then develop and implement plans for engaging stakeholders.

· Portfolio performance management: Negotiate and realize the portfolio’s expected value based on metrics, budget, and other factors. Document evidence of measuring portfolio performance as judged by the defined value metrics.

· Portfolio risk management: Develop a risk management plan in which portfolio risk tolerance, risk processes, and risk responses are defined. Develop a risk register in which risks to the portfolio are identified and risk owners are assigned.

Overview of Federal Shared Services

In 2001, the President’s Management Agenda encouraged federal agencies to use administrative and operational services and processes that other federal and external parties provide, commonly referred to as federal shared service providers, to save money and increase efficiencies. Federal shared service providers such as the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Finance Center (NFC) provide human resources services ranging from hiring to payroll to time and attendance.

OPM offers human resources services to federal agencies for hiring, performance management, and human resource employee training and development. For example, OPM provides, among other things, cloud-based learning management systems to federal agencies to support employee skills enhancement.

The NFC is a service provider for payroll, human resources, and insurance services to approximately 156 federal agencies.[11] Its services include:

·

Payroll and Personnel System

Payroll/Personnel System (PPS) is an NFC built and owned payroll and personnel

system that provides back-end payroll processing to federal entities and

employees.

·

Human Resources System

EmpowHR is a web-based human capital management system that human resource

staff use to enter employee information such as position information, personnel

actions, and employee addresses.

·

Time and Attendance

GovTA is a web-based time and attendance tool that interfaces with the

payroll/personnel system and allows employees to input their time and

attendance data.

HRIT Strategic Goals Have Changed Multiple Times; Few Results Achieved

DHS initiated HRIT in 2003, but by 2010 had made limited progress on the HRIT investment, as reported by DHS’s Inspector General.[12] Between 2011 and 2025, HCBS transitioned among three sets of goals. Specifically, in 2011 DHS developed 15 strategic goals, in 2020 DHS announced 5 new strategic goals, and in 2022 HCBS began transitioning to two new goals. Officials stated that the goals in each of the three sets relate to each other and that the associated changes were due to evolving priorities of the department. HCBS made limited progress in achieving the first two sets of goals between 2011 and 2022, and the extent of HCBS’s progress towards achieving the third set is yet to be determined because these goals have been in draft since 2022.

Limited Progress on Past Goals

Strategic Goals from 2011 to 2020: As previously mentioned, in 2011 DHS developed 15 strategic goals for HRIT. In 2016, we reported that HRIT had made very little progress in implementing the portfolio’s 15 goals, also known as strategic improvement opportunity areas.[13] Specifically, we found that while most of the areas were to be delivered by June 2015, only one had been met, and the completion dates for the other 14 were unknown.

DHS eventually discontinued its use of the 15 goals in 2020. For the 15 goals over the 9-year period from 2011 to 2020, HCBS met three of the goals: (1) establish HRIT performance measures tracking and reporting; (2) improve communication and collaboration among components by creating cross-component human capital working groups; and (3) create an intake process for evaluating HRIT projects and proposals prior to funding them. HCBS did not fully achieve the remaining 12 goals. See appendix II for a list of the 15 goals.

Strategic Goals from 2021 to 2022: In October 2020, HCBS issued a strategic plan containing five new goals covering fiscal years 2021-2025. According to officials, they made this change to refine their prior goals and align HRIT’s goals with a federal human capital business reference model.[14] See appendix II for a list of these five goals.

HCBS partially met two of the five goals: (1) maturing the use of technology and (2) maturing the management and use of data. Specifically, these goals were partially addressed via the implementation of several systems as well as system improvements. For example, HCBS officials created a system called the Human Resources Service Center to provide capabilities to employees and human resources staff. In addition, HCBS officials improved the Human Capital Enterprise Information Environment, which is a data environment for human capital information to support enterprise-wide reporting and data analytics.[15] These improvements included migrating the Enterprise Information Environment to a cloud environment in 2022. According to HCBS officials, this improvement reduced costs and increased security. Further, in 2021, DHS began activities to transition from its existing time and attendance system (WebTA) to a replacement system (GovTA).

In another effort aimed at addressing the strategic goals, in November 2022 HCBS deployed an enterprise-wide learning management system called DHSLearning. However, it did not replace ten duplicative learning management systems used across DHS as intended, and DHSLearning was only implemented by DHS headquarters and three of DHS’s nine components.

Seven months later (in May 2023), DHSLearning was forced offline due to a system failure which also caused data losses due to the vendor’s system backups being improperly configured. In response, in June 2023 DHS terminated DHSLearning.[16] As a result, HCBS made no progress in reducing duplicative learning management systems used across the department.

HCBS officials stated that starting around 2022, they stopped focusing on these five goals.

HCBS Developed New Draft Goals

HCBS began transitioning to a third set of draft goals in 2022. According to DHS officials, this third set of goals was developed to further refine HRIT’s goals. Specifically, the office created two new draft goals: (1) streamlining HRIT solutions to support end-to-end processing, and (2) maturing human capital data management.

As of April 2025, HCBS officials stated that they had made progress toward the draft goals.

· Goal 1: Streamlining HRIT solutions to support end-to-end processing. Officials reported that in fiscal year 2023, the Human Resources Service Center delivered quarterly reporting of “time-to-hire” data and the ability to input and extract employee service history data. Further, in fiscal year 2024 HCBS officials stated that they automated quality control for recruitment requests during the hiring process.

According to HCBS officials, they intend to achieve this draft strategic goal by implementing an end-to-end human capital management system through NFC as its shared service provider. This system is expected to replace and streamline aging systems that DHS relies on to provide human resource services throughout the employment lifecycle—from hiring, to payroll, to benefits, to separation.

· Goal 2: Maturing human capital data management. HCBS officials stated that in fiscal years 2023 and 2024 they updated a data dictionary and integrated data archiving from a variety of systems across DHS and the operational components, such as employee training and time and attendance data. Officials also noted that in fiscal year 2023, HCBS began its GovTA migration testing and DHS fully implemented GovTA in March 2025.

HCBS officials plan to build data standards and establish a data governance approach. They also intend to establish connections between the Enterprise Information Environment and new or updated systems used by DHS or its components.

While DHS has been taking selected actions since 2022 that were intended to achieve the current draft goals, as of April 2025 the goals had not been finalized. Therefore, it remains to be seen the extent to which these efforts will contribute to whatever goals are eventually approved. As of April 2025, officials added they were working to ensure that their plans and goals align with the new President’s priorities and department-wide direction.

However, the officials were not certain when HRIT plans and goals would be finalized or what impact the leadership changes would have on the HRIT strategy. As a result, HCBS continues to expend resources on an initiative started more than 20 years ago that has no approved goals and has yielded limited results.

HCBS Has Not Fully Implemented Portfolio Management Practices

The portfolio’s lack of progress in achieving its goals is due, in part, to gaps in HRIT’s implementation of six key portfolio management practice areas. Specifically, of the six portfolio management practice areas defined by the Project Management Institute’s (PMI) Standard for Portfolio Management, the HCBS office partially implemented five of the areas and did not implement the remaining area. Table 3 describes the areas and provides our assessment of HCBS’s implementation of each.

Table 3: Summary of the Department of Homeland Security’s Human Resources IT Portfolio’s Implementation of Portfolio Management Practice Areas

|

Portfolio management practice area |

GAO rating |

|

Strategic Management |

◑ |

|

Governance |

◑ |

|

Capacity and Capability Management |

◑ |

|

Stakeholder Engagement |

◑ |

|

Performance Management |

○ |

|

Risk Management |

◑ |

Legend: ●=Fully implemented ◑=Partially implemented ○=Not implemented

Source: GAO analysis of the Department of Homeland Security’s Human Resources IT portfolio documentation against practices defined in Project Management Institute, Inc., The Standard for Portfolio Management – Fourth Edition (Newton Square, PA: 2017). | GAO‑25‑107233

Portfolio Strategic Management—Partially Implemented

PMI’s Standard for Portfolio Management states portfolios should be clearly defined, linked to strategic objectives, and include project selection and prioritization criteria. This includes developing a portfolio strategic plan, which includes a vision, mission statement, description of the organization’s long-term portfolio goals and objectives, and explains how the organization plans to achieve these general goals and objectives.

In January 2024, HCBS developed a draft strategic plan for HRIT. In addition, HCBS assigned priority levels to each project in the portfolio. However, the HRIT portfolio has been without a final strategic plan that reflects current goals since 2022. HCBS officials were not certain when their draft plan would be finalized.

In addition, the portfolio is not clearly defined, because HCBS lacks visibility into all existing human resources systems that comprise HRIT. Specifically, officials roughly estimate there are 89 human resources systems used across the department and its components. However, officials did not validate the accuracy and completeness of this number. Officials stated that they did not have a process in place with components to review the systems inventories to ensure the accuracy. HCBS officials explained that they do not have the resources to examine every human resource system utilized across the department.

However, DHS continues to fund component systems without assurance that HCBS officials understand the value and scope of systems supporting HR functions. HCBS officials’ position on a system inventory represents a reversal from 2018, when DHS addressed one of our recommendations by updating and maintaining its inventory of human resources systems.[17] Further, this position is inconsistent with the former Deputy Secretary’s statement that the Department could no longer sustain a component-centric approach in acquiring human resources systems.

Until HCBS establishes a complete inventory of human resources systems, its ability to have fully informed long-term portfolio goals and objectives is at risk. In addition, until HCBS finalizes an HRIT strategic plan that describes the portfolio’s goals and explains how the organization plans to achieve these, the department is at risk of investing in projects that do not meet its strategic goals or support DHS in meeting its mission.

Portfolio Governance—Partially Implemented

According to PMI, portfolio governance includes: establishing clearly defined governance roles for the portfolio; developing processes and timelines for updating governance documents; reviewing and updating portfolio management plans; assigning a portfolio manager to effectively manage the portfolio; assigning a portfolio sponsor to help obtain the needed resources to meet the portfolio’s goals; and establishing a portfolio governance board to provide the appropriate leadership, oversight, and decision making.

HCBS has taken actions to provide portfolio governance. Specifically, it has designated a portfolio manager and portfolio sponsor. In addition, in 2014, DHS established a portfolio governance board, referred to as the Human Capital Leadership Council.

However, the HCBS office does not have documentation that outlines the roles and responsibilities of the Human Capital Leadership Council. While officials stated that they are working to draft a charter for the council, HCBS has not established a timeline for completion or frequency of updates.

In addition, the 2020 HRIT Portfolio Program Management Plan, which includes the roles and responsibilities of the HRIT program and project managers, contains outdated references. Specifically, the plan references the obsolete strategic improvement opportunities and an executive steering committee that was dissolved in August 2022. HCBS has not established a timeline or frequency for updating this important plan.

HCBS officials stated that all governance documents are updated on an as-needed basis. However, the officials did not provide a reason why they have not developed a process or timeline for updating documents.

Until HCBS establishes and implements a process, timeline, and frequency for maintaining HRIT’s governance documents, the office’s ability to provide the appropriate leadership, oversight, and decision making for the portfolio will be limited.

Portfolio Capacity and Capability Management—Partially Implemented

PMI states that effective and efficient capacity and capability management connects the portfolio’s overall strategy with the attainment of its objectives. This practice includes identifying, allocating, and optimizing resources for maximizing utilization and minimizing resource conflicts in portfolio execution. Capacity and capability management in the context of portfolio management applies to all aspects of resources such as staff, capital, and technology.

On an annual basis, HCBS’s five branch directors each develop a capacity plan that provides estimates for staff and capital resource needs.[18] In addition, officials stated that the Human Capital Leadership Council assesses the portfolio monthly and on an ad hoc basis.

HCBS has not conducted a comprehensive portfolio capabilities assessment since 2018. Given that the HRIT goals have changed twice since then, the capabilities assessment has not stayed up to date with HRIT’s strategy. HCBS officials stated that they do not know why they have not updated the capabilities assessment. They acknowledged that the portfolio would benefit from such an assessment; however, as of December 2024, they do not have a timeline for conducting one. HCBS officials stated that the decision to conduct an assessment would be weighed against other priorities and available resources.

The lack of a current capabilities assessment limits HCBS’s ability to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the capabilities of the HRIT portfolio. This may prevent HCBS from optimizing selection, funding, and execution of the portfolio’s projects, and continue to limit progress on HRIT.

Portfolio Stakeholder Engagement—Partially Implemented

According to PMI, portfolio stakeholder engagement includes identifying and analyzing the stakeholders and then developing and implementing plans for engaging them.

According to HCBS officials, they identify stakeholders for specific projects during the analysis phase of the project life cycle and during project readiness review meetings. In addition, HCBS has demonstrated some evidence of stakeholder engagement at regular meetings such as monthly meetings with operational components and at project milestone meetings.

However, HCBS does not have a stakeholder engagement plan. The officials attributed the absence to the portfolio’s lack of resources, multiple shifts in direction, and changes in leadership.

In addition, it is unclear the extent to which stakeholders have been engaged and are supportive of DHS’s major decisions. For example, the degree of support from stakeholders, such as DHS’s operational components, to continue to pursue NFC as the shared service provider for the future end-to-end human capital management system is unknown (and discussed in more detail later).

Specifically, HCBS officials stated that they met with stakeholders in May 2024 to discuss this approach, and decided to continue with NFC until the center provided more information on the full plan regarding the human capital management system. However, HCBS had not documented these decisions or stakeholders’ (such as the departments’ operational components) buy-in to this approach. In addition, officials from three of DHS’s nine components (U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the U.S. Secret Service, and U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement) stated that they are working on implementing their own end-to-end human capital management systems thereby reinforcing component-based solutions.

Without a stakeholder engagement plan and documentation of stakeholder engagement activities and decisions, there is a greater likelihood for communication and expectation gaps between HRIT and its stakeholders.

Portfolio Performance Management—Not Implemented

PMI’s Standard for Portfolio Management states that portfolio performance management (also called value management) includes negotiating and realizing the portfolio’s expected value based on metrics, budget, and other factors. It also includes documenting evidence of measuring portfolio performance as judged by the defined value metrics.

Contrary to these best practices, HRIT’s two current draft goals are not readily measurable. Specifically,

· The draft strategic plan states that the first draft goal—streamlining HRIT solutions to support end-to-end processing—will be achieved by consolidating DHS’s more than 80 human resources systems and tools into one platform. As previously mentioned, HCBS intends to achieve this goal by acquiring an end-to-end human capital management system through the NFC. This system is expected to replace and streamline the department’s aging human resources systems.

However, DHS officials have stated that they do not expect all components to implement the new system. For example, as previously mentioned, the officials from three of DHS’s nine components stated that they do not plan to implement the department-wide solution because they are working on implementing their own solutions. Moreover, HCBS did not specify how many of the over 80 systems they realistically plan to reduce and did not establish quantitative targets for how much duplication will be eliminated as part of HCBS’s plan.

· The second draft goal—mature human capital data management—is also not readily measurable. Specifically, the draft strategy states that HCBS plans to continue to improve the Enterprise Information Environment. For example, as previously mentioned, HCBS officials plans to expand its use of the environment by building data standards and establishing a data governance approach. They also plan to establish connections between the enterprise information environment and new or updated systems used by DHS or its components. However, the plan lacks detail and specificity to allow for observable ways to measure the extent to which the goal will be achieved.

In contrast to the two current draft goals, our review of the prior 15 goals covering 2011 to 2020 shows that nine of these goals were readily measurable and focused on department-wide solutions. For example, in reviewing the short titles of the 15 goals, we determined that

· four use the phrase “enterprise-wide solution,” and

· five use descriptive terms reflecting a department-wide perspective, such as centrally managed data portal, a single system, enterprise-wide platform, integrated system, and system used by every component.

According to HCBS officials, they do not have a performance measurement process to determine progress against goals. Officials stated that this is generally due to a lack of maturity in their portfolio management approach.

Until HCBS establishes measurable goals in a finalized strategic plan, DHS leadership and the Congress will not be able to determine how much progress HRIT is making. DHS also would not be able to identify whether the portfolio’s annual appropriations are being effectively spent to achieve DHS’s long-standing goal of reducing duplication and increasing efficiencies.

Moreover, we also found that HCBS collects incomplete project data which restricts the office’s ability to determine HRIT performance for its ongoing projects. Specifically, at the beginning of 2024 HCBS officials started using a centralized project tracking document to determine the progress of each HRIT project. As of October 2024, HRIT had 24 in-progress and 25 completed projects recorded on the project tracker. However, 28 of 49 completed and in-progress HRIT projects (57 percent) were missing either or both complete estimated and actual cost data. Furthermore, 22 of the 49 completed and in-progress projects (45 percent) were missing complete planned and/or actual critical milestone data.[19]

HCBS officials stated that they rely on the branch directors and project managers to populate HCBS’s HRIT project tracking documents each month and do not track down any past data that was missing or conflicting. As a result, HCBS is unable to determine the performance of these projects in the portfolio over time. See appendix III for a table of in-progress projects as of October 2024.

In addition, by not collecting complete data to measure the portfolio’s performance, HCBS will also be limited in its ability to report on the portfolio’s achieved value. The lack of data collected, and the lack of analysis performed, can hinder HCBS in making data-driven changes to its strategy.

Portfolio Risk Management—Partially Implemented

PMI states that portfolio risk management includes developing a risk management plan in which portfolio risk tolerance, risk processes, and risk responses are defined, and a risk register in which risks to the portfolio are identified and risk owners are assigned.

HCBS has a risk management plan that describes how to identify, analyze, mitigate, and report risks that affect the HRIT portfolio’s projects. The plan also states that each project’s risk manager will assign risk ratings through collaborative efforts, and high-rated risks will receive particular attention from HCBS leadership.

In addition, HCBS maintains a risk register for the HRIT portfolio that includes, among other things, a risk description, likelihood of the risk occurring, a mitigation strategy for the risk, risk rating and risk owner. As of October 2024, the risk register included three portfolio-level risks and 30 project-level risks.

However, the HCBS risk register does not cover risks for all in-progress HRIT projects. For example, of the 24 ongoing HRIT projects, as of October 2024, the risk register only covered five projects. The 19 other projects did not identify any risks.

HCBS officials stated that they have discussed the need to put additional focus on identifying project risks and reported that in October 2024 they integrated the risk management review process into the monthly branch meeting discussions. However, as of February 2025, HCBS had 11 in-progress projects that had not identified any risks. As such, there are still gaps in the HRIT risk management process.

Until HCBS establishes and implements a process that ensures risks are identified for every HRIT project, the office will lack a process that ensures risks that could impact the success of the projects are appropriately mitigated.

Gaps Exist in Addressing Challenges in Overseeing Shared Service Providers

DHS reported two key challenges in overseeing shared service providers for HRIT services. First, DHS officials stated that they have had difficulty in ensuring that shared service providers follow security requirements. Second, DHS officials stated that they have experienced uncertainty in the timing of replacing legacy HRIT systems. Addressing these challenges is essential to ensuring the security of personally identifiable information and planning for system replacements.

DHS Faces Challenges in Ensuring Shared Service Providers Follow Security Requirements

DHS officials stated that ensuring shared service providers follow security requirements has been problematic. These requirements are set forth by the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Circular A-130.[20] Among other things, this circular requires federal agencies to implement information security programs that include continuous monitoring of security controls.[21] In instances where an agency is relying on a shared service provider, the circular also requires agencies to describe the responsibilities in agreements with the service providers. In addition, the circular notes that when an agency acts as a service provider (e.g. Agriculture, OPM), the ultimate responsibility for compliance with applicable requirements of this circular remains with the agency receiving the service (e.g. DHS) and is not shifted to the service provider. Lastly, the General Services Administration’s Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP) calls for the agency receiving a service (e.g. DHS) from a cloud provider to conduct continuous monitoring of the provider to support the agency’s ongoing security authorizations.[22]

Monitoring Concerns with Agriculture’s Human Resources Shared Services

DHS heavily relies on Agriculture’s NFC shared systems to perform, among other things, personnel actions via EmpowHR; payroll processing with Payroll/Personnel System (PPS); and time and attendance recording via GovTA.

However, DHS and others have reported significant concerns related to the security of agency data maintained in NFC systems.

· In July 2022, NFC mailed sensitive information to tens of thousands of federal employees using outdated personnel information.

· In December 2022, the Agriculture Office of Inspector General found NFC’s systems had unmitigated vulnerabilities, a lack of proper reporting and tracking of these unmitigated vulnerabilities, and a lack of policies and procedures to properly respond to vulnerabilities.[23]

· In January 2023, an NFC system misconfiguration exposed sensitive DHS personnel data on the internet.

· In July 2023, the National Academy of Public Administration reported that NFC’s system for processing payroll (PPS) for many federal agencies, including all of DHS’s employees, is a legacy mainframe-based system that needs to be replaced.[24] The report noted that the system is complex with over twenty subsystems that make it time-consuming to design and implement upgrades, enhancements, and increase functionality.

Consistent with Circular A-130, while Agriculture’s OCIO is responsible for the maintenance and security of NFC’s shared human capital systems, DHS (and every other agency using these services) is ultimately responsible for the continuous monitoring of these systems. DHS has agreements in place with NFC for each of these three systems. However, DHS did not ensure the agreements included access to documentation the department needed to conduct continuous monitoring activities.

This has resulted in DHS officials reporting that Agriculture’s OCIO has not provided the DHS OCIO with important security documentation needed to effectively monitor EmpowHR, PPS, and GovTA.

· EmpowHR – To enable continuous monitoring of EmpowHR, DHS officials made at least five requests to Agriculture between April 2024 and October 2024. DHS requested access to key security documentation (e.g. security authorization letters, recent security scans, system design documentation, contingency plans, incident response plans, and a plan of action and milestone reports).[25] However, Agriculture did not provide access to the requested security documentation.

In addition, in May 2024, the DHS Office of the Chief Information Security Officer identified significant security vulnerabilities in NFC’s EmpowHR system. DHS determined the risk of these vulnerabilities was acceptable if certain conditions were met. These conditions included that DHS conduct monthly reviews on the EmpowHR system to ensure Agriculture was addressing the vulnerabilities. Between June 2024 and August 2024, DHS officials made at least 18 requests to Agriculture to review their progress in addressing the vulnerabilities. However, Agriculture did not provide the requested documentation to enable such a review.

In July 2024, DHS’s Chief Information Security Officer re-granted the authority to operate for EmpowHR, contingent upon certain conditions being met, including DHS performing monthly continuous monitoring reviews of EmpowHR. However, in March 2025, DHS officials stated that because Agriculture did not provide the requested documentation, DHS was unable to satisfy the condition of performing monthly continuous monitoring reviews.

· PPS – Similar to EmpowHR, DHS made a series of at least five requests to Agriculture to enable continuous monitoring between April 2024 and October 2024. However, Agriculture did not provide access to the requested security documentation.

· GovTA – As with the other systems, DHS made a series of requests for documentation to Agriculture. In April and November 2024, Agriculture provided DHS with some system security documentation, such as security assessment reports, a system security plan, and plans of action and milestones reports for GovTA. However, DHS officials stated that Agriculture has not provided all of the requested documents, such as penetration testing reports or cyber hygiene reports. In March 2025, Agriculture officials stated that they provided DHS with a high-level briefing on penetration testing and red-team testing but stated that Agriculture does not provide its cyber hygiene reports to any agency.

In March 2025, Agriculture OCIO officials stated that beginning in April 2025, a monthly meeting is to occur between Agriculture and DHS to discuss the continuous monitoring concerns and requested security documentation related to EmpowHR, PPS, and GovTA. Agriculture OCIO officials acknowledged that they had not provided DHS officials access to the documents they were requesting for these NFC systems. Agriculture officials noted that they planned to provide access to annual security assessment documents for EmpowHR, but according to DHS, as of April 2025, this had not yet occurred. In addition, according to DHS officials, access to annual security assessments will not enable them to satisfy the Department’s continuous monitoring needs.

As such, DHS’s awareness of the security of its data stored and managed in these systems will continue to be limited until DHS renegotiates its applicable agreements to obtain more access to security documentation with NFC’s shared human resources systems.

In addition, until Agriculture renegotiates applicable agreements with DHS for EmpowHR, PPS, and GovTA to allow DHS to conduct continuous monitoring of these systems, DHS will continue to be unable to meet its security requirements mandated by OMB.

System Security of DHSLearning Shared Service Was Not Fully Monitored

The OPM-sponsored DHSLearning system was the other shared service system that DHS experienced issues within the monitoring of the system security. In September 2022, after reviewing the vendor’s security practices, the DHS Chief Information Security Officer granted the approval to allow the system to operate. Accordingly, DHSLearning was deployed in November 2022.

In May 2023, DHSLearning experienced a system failure that forced the system offline. DHS also reported experiencing data losses. Following the incident, DHS conducted an investigation and determined that the vendor’s legacy hardware had failed, and system backups were not properly configured. In June 2023, the Chief Information Security Officer determined that these failures reflected poor cybersecurity practices with the OPM-sponsored DHSLearning environment. He stated that the risk to DHS operations and assets was not acceptable and issued a decision to deny DHSLearning’s authority to operate.

As a result, DHS headquarters and the three components that were using DHSLearning were left with no learning management system until they determined workarounds. For example, officials from the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers stated that when DHSLearning was shut down, it had to develop its own system. They stated that doing so was difficult due to the component’s small size which did not have the level of staffing or the resources to dedicate to such an effort.

Prior to the May 2023 incident, DHS’s HCBS officials reported that their Information System Security Officer was following OMB’s and DHS’s continuous monitoring requirements. Specifically, officials reportedly monitored activities of the security of the system by reviewing monthly reports provided by the vendor. Officials stated that no high-risk issues were identified, and that they monitored the vendor’s progress in addressing the small number of lower risk issues on a monthly basis.

However, HCBS officials provided limited evidence of their continuous monitoring activities. For example, officials provided one artifact that demonstrated that they reviewed the cloud service provider’s plans of action and milestones report from March 2023. Furthermore, this artifact identified cloud service provider weaknesses, but did not identify tasks, resources, milestones, or completion dates to address them. This lack of detail in the artifact hindered DHS’s ability to ensure the weaknesses were addressed. Given the limited and incomplete documentation, the extent to which HCBS was conducting continuous monitoring activities on the cloud service provider is unclear.

Following the incident, and in response to a DHS Office of Inspector General report on the issues with DHSLearning,[26] the department prepared an after action and lessons learned report. Specifically, in August 2024, DHS reported that OCHCO has partnered with OCIO to more proactively assess the security of the systems they leverage from federal shared service providers.

Further, in July 2024, DHS created a draft cloud continuous monitoring guide that describes actions DHS is required to take to bring a cloud system into compliance when the provider fails to maintain an adequate risk management program. If implemented effectively, these actions should reduce the likelihood that future disruptions or loss of critical operations provided by cloud service providers will occur.

Shared Service Provider Plans for Replacing Legacy Systems Are Uncertain

DHS and others have reported significant concerns about NFC’s legacy human resources systems. For example, in July 2023 the National Academy of Public Administration reported that NFC’s system that processes payroll for many federal agencies, including all of DHS’s employees, is a legacy mainframe-based system that needs to be replaced.[27] The report noted that the system is complex with over twenty subsystems that make it time-consuming to design and implement upgrades, enhancements, and increase functionality.

The mainframe also uses a legacy programming language, referred to as Common Business Oriented Language (COBOL). As we have previously reported, COBOL was introduced in 1959 and became the first widely used, high-level programming language for business applications. The Gartner Group, a leading IT research and advisory company, has reported that organizations using COBOL should consider replacing the language, as procurement and operating costs are expected to steadily rise and because there is a decrease in people available with the proper skill sets to support the language.[28]

In response to these issues, in 2023 DHS’s HCBS finalized an analysis of alternatives to evaluate options and recommend the best path forward to mitigate the risks of its reliance on NFC’s legacy systems and to modernize its human resources systems and processes.[29] The analysis recommended against using a federal shared service provider, because the study reported that such a provider was not as agile in implementing modernization efforts. Instead, the study recommended using a commercial shared service provider, which could provide benefits such as increased self service to customers and a reduction in manual data entry for staff.

Following the 2023 HCBS alternatives analysis, and the National Academy of Public Administration study, NFC began working on a plan to modernize its legacy systems. Specifically, as previously mentioned, NFC planned to acquire a commercial cloud-based, end-to-end human capital management system that would replace NFC’s legacy human resources systems, including PPS and EmpowHR.

Aware of NFC’s plans, DHS leadership decided to remain with NFC. HCBS officials stated that they believed this decision was consistent with the intent of the 2023 alternatives analysis recommendation, given that NFC was now planning to implement a commercial cloud-based system that would be shared across its federal customers. HCBS officials also reasoned that it would be significantly more expensive for DHS to pursue acquiring its own commercial system rather than using a federal shared service option.

According to NFC officials, in November 2024 they finalized a business case for the modernization effort. NFC expected that the modernization would be multi-phased and take approximately eight years for full implementation.

However, in March 2025, NFC officials stated that the modernization was placed on hold until new leadership assessed whether the effort would continue.

Given these developments, DHS currently does not know if or when NFC will be able to deliver the capabilities DHS needs to modernize its HRIT environment. In March 2025, DHS officials stated that a potential delay in implementation of NFC’s end-to-end human capital management system poses significant operational, strategic, and workforce challenges for DHS. Officials stated that without the modernized system, human resources staff will continue to manually process data. In addition to contributing to inefficiencies, manual efforts introduce greater risk of errors in critical functions such as hiring, payroll, and benefits administration.

As a result of these developments, the 2023 alternatives analysis is out of date as it did not assess current alternatives. For example, the alternatives analysis did not include an assessment of using NFC as DHS’s shared service provider for a commercial cloud-based human capital management system. The alternatives analysis also did not assess the impact of waiting for NFC to determine if the center will move forward with acquiring a human capital management system.

Until HCBS updates its alternatives analysis to reflect current options and associated uncertainty to determine the best alternative for consolidating DHS’s human resources systems and processes, the department is likely to continue to experience the inefficiencies and ineffectiveness that it has faced for over 20 years.

Conclusions

DHS’s mission is vital to the security of the United States, but it still struggles with the legacy of merging 22 disparate organizations. Notably, since 2003, DHS has been working to consolidate, integrate, and modernize the department’s human resources IT infrastructure. DHS has made limited progress in achieving its goals, which inhibits DHS’s ability to prepare for, and quickly respond to, emergencies. As a result, HCBS continues to expend resources on an initiative started more than 20 years ago that has no approved goals, has yielded limited results, and led to few department-wide solutions.

The gaps in DHS’s portfolio management practices for HRIT, including the absence of a finalized strategic plan, a complete inventory of human resources systems, up to date governance documents, a current capabilities assessment, a plan for stakeholder engagement, measurable goals, complete project status information, and a process for identifying risks for all HRIT projects, have contributed to this stagnation. Until DHS addresses these gaps, the department’s duplicative and inefficient human resources systems will persist.

Furthermore, DHS’s gaps in its actions to address persistent challenges has led to further setbacks in its attempts to modernize and consolidate human resources systems. Specifically, until DHS and Agriculture renegotiate applicable agreements on key shared systems to allow DHS access to documents to conduct continuous monitoring of these systems, DHS will continue to be unable to meet its security requirements. In addition, without an updated HRIT alternatives analysis to reflect current options and associated uncertainty for consolidating its human resources systems and processes, DHS will continue to underdeliver on its HRIT consolidation and modernizations promises.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of 10 recommendations, including 9 to DHS and one to Agriculture. Specifically:

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer to establish and implement a timeframe for updating and maintaining the HRIT strategic management plan and ensure it reflects measurable strategic goals. (Recommendation 1)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer to establish and implement a process for ensuring it has a complete inventory of human resources systems that are used across DHS, on an ongoing basis. (Recommendation 2)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer to develop and implement a process, timeline, and frequency for updating HRIT portfolio governance documents. (Recommendation 3)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer to update the HRIT portfolio capabilities assessment to ensure it is in alignment with the current portfolio. (Recommendation 4)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer to develop and implement a plan for engaging portfolio stakeholders that includes documenting key decisions made with stakeholders. (Recommendation 5)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer to collect complete project information from each of the components’ HRIT projects and measure the performance of the projects based on complete project data to ensure they are producing value against HRIT’s strategic goals (once finalized). (Recommendation 6)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer to establish and implement a process that ensures risks for every HRIT project are identified. (Recommendation 7)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer and the Chief Information Officer to renegotiate applicable agreements with Agriculture and NFC officials to obtain more access to security documentation with NFC’s EmpowHR, PPS, and GovTA systems. (Recommendation 8)

· The Secretary of Homeland Security should direct the Chief Human Capital Officer to update its alternatives analysis to reflect current options and associated uncertainty to determine the best alternative for consolidating and modernizing DHS’s human resources systems and processes. (Recommendation 9)

· The Secretary of Agriculture should direct the department’s Chief Information Officer and officials from NFC to renegotiate its agreements with DHS for EmpowHR, PPS, and GovTA, to allow access to security documentation for continuous monitoring activities. (Recommendation 10)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DHS and Agriculture for review and comment.

DHS’s comments are reprinted in appendix IV. In written comments, DHS generally concurred with our nine recommendations directed to them and provided estimated completion dates for implementing eight of the recommendations.

DHS also provided considerations related to the evolution and achievement of its strategic goals. Specifically, DHS stated that with each new set of goals, the department has refined its priorities, rather than fully replacing them. In addition, DHS stated that it does not expect to fully replace all existing human capital systems with an enterprise human capital management system. We updated the report accordingly.

In addition, while DHS stated that it concurred with recommendation 9, the department indicated that it disagreed with the need to conduct a new alternatives analysis. DHS stated that it plans to leverage the results from NFC’s and OPM’s planned procurements of human resources IT solutions to inform DHS’s strategy and align the operations plans. DHS also requested that we consider this recommendation resolved and closed.

However, the timeframes for NFC’s procurement have been delayed. In addition, as of March 2025, NFC did not know when it would be able to proceed with its procurement. DHS officials have stated that a delay in implementation of an end-to-end human capital management system poses significant operational, strategic, and workforce challenges for DHS. Therefore, we maintain the need for DHS to reassess all potential options and associated timelines to determine the best alternative for modernizing DHS’s human resources systems. Accordingly, we do not agree that DHS has resolved this recommendation.

DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

In an email, a program analyst from the Office of the Chief Financial Officer at the Department of Agriculture stated that Agriculture agreed with our recommendation directed to them.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of the Departments of Homeland Security and Agriculture, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Kevin Walsh at WalshK@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Kevin Walsh

Director, Information Technology and Cybersecurity

Our objectives were to (1) identify changes to HRIT strategic goals and progress made in achieving them, (2) evaluate the extent to which DHS implemented portfolio management practices for HRIT, and (3) determine the challenges, if any, DHS has experienced in overseeing shared service providers for key HRIT services and the extent to which DHS has addressed them.