TEMPORARY ASSISTANCE FOR NEEDY FAMILIES

Enhanced Reporting Could Improve HHS Oversight of State Spending

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107235. For more information, contact Jeff Arkin at (202) 512-6806 or arkinj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107235, a report to congressional requesters

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

Enhanced Reporting Could Improve HHS Oversight of State Spending

Why GAO Did This Study

Since 1996, the TANF block grant has annually provided $16.5 billion in federal funding to states to help low-income families. In addition, states collectively spend approximately $15 billion of their own funds. States have broad flexibility to use these funds to meet TANF’s statutory purposes. There is limited detail reported on state spending of these federal funds.

GAO was asked to review TANF spending. This report addresses, among other things, trends in states’ use of TANF funds; selected states’ TANF budget decisions; and the extent to which HHS collects expenditure data for oversight purposes. This report is part of a series of reports on TANF to be issued in the coming months.

GAO analyzed HHS TANF expenditure data; reviewed federal laws, HHS regulations and guidance, and TANF reporting; interviewed HHS officials and officials in eight selected states. GAO selected these states to reflect a range of geographic regions and poverty rates.

What GAO Recommends

Congress should consider granting HHS authority to collect additional TANF-related information from states, as appropriate, for oversight purposes. GAO is also making two recommendations, including that HHS (1) ensure states submit complete narrative data in their expenditure reporting and (2) review reporting requirements to enhance the information it collects from states consistent with its statutory authority. HHS agreed with our recommendations and outlined plans to address them.

What GAO Found

Nationwide, state spending on Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) “non-assistance” services—such as work activities, education, and training activities—increased as a percentage of total TANF spending between fiscal year 2015 and fiscal year 2022 (from 40.8 to 44.2 percent). During that period, “assistance” spending, including cash payments to needy families, decreased as a percentage of total spending (from 27.2 to 25.2 percent). Individual state spending on those categories varied. See figure below for total fiscal year 2022 spending and transfers by TANF category.

Officials GAO interviewed from selected states said they considered various factors—such as the number of families eligible for cash assistance, legislative priorities, and historical precedent—when making decisions about assistance and non-assistance spending and transfers to other allowable block grants. Selected states attributed increases in unspent funds (from $4 billion in 2015 to $9 billion in 2022, nationwide) to overestimation of program needs and availability of other time-limited federal funds, such as those for COVID-19 relief.

States are required to file various reports on their TANF expenditures with the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). However, GAO found that:

· In March 2024, seven states (out of 31 whose reported expenditures required narrative explanations) were missing or had incomplete narratives for fiscal year 2022. New control activities to improve the completeness of required reporting would enhance HHS oversight of states’ TANF spending.

· States’ reporting does not include detailed information on aspects of TANF expenditures—such as information on planned non-assistance spending or on subgrantees that administer TANF-funded programs. This type of information could strengthen oversight, potentially including that of improper payments, and guide future decision-making on TANF. While current law limits what information HHS can collect from states, HHS could identify additional reporting requirements within its existing statutory authority to enhance the completeness of states’ reporting. Further, Congress could consider providing HHS statutory authority to collect additional information as appropriate for oversight purposes.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

ACF |

Administration for Children and Families |

|

AFDC |

Aid to Families with Dependent Children |

|

CCDF |

Child Care and Development Fund |

|

HHS |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

|

MOE |

maintenance of effort |

|

PEAF |

Pandemic Emergency Assistance Fund |

|

PRWORA |

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 |

|

SSBG |

Social Services Block Grant |

|

TANF |

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 12, 2024

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

The Honorable Darin LaHood

Chairman

Subcommittee on Work and Welfare

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

Since 1996, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant has provided $16.5 billion annually in federal funding to states.[1] States have substantial flexibility and autonomy to determine how to allocate federal TANF funds while meeting its statutory goals.[2]

TANF is administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Administration for Children and Families (ACF). States may use TANF funds for a broad set of programs that tackle poverty, reduce child welfare involvement, and address the specific needs of their communities. However, there is limited federal reporting on how states use these funds to support programs that address these issues.[3] Most federal reporting requirements in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA)—which authorized TANF—apply only to states’ “assistance programs,” which provide benefits such as cash payments to eligible families, and not to “non-assistance” services, such as workforce training and pre-kindergarten programs.[4] In 2012, we reported that since the start of the program, spending on non-assistance had increased while spending on assistance programs had decreased.[5] Concerns about misuse of TANF funds underscore the importance of transparency in how states’ use both TANF assistance and non-assistance funds.[6]

You asked us to review state spending for TANF non-assistance funds. This report reviews (1) trends in states’ use of TANF funds from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2022, (2) how selected states budget and allocate TANF funds, (3) the extent to which selected states used eligible non-governmental third-party expenditures to satisfy maintenance of effort (MOE) requirements, (4) how selected states ensure TANF spending meets statutory purposes and accurately report expenditure data to ACF, and (5) the extent to which ACF collects information on states’ use of TANF funds for oversight purposes.

To describe how states used TANF funds from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2022, we analyzed TANF expenditure data reported by states to ACF from fiscal year 2015 through fiscal year 2022, the most recent available data at the time of our analysis.[7] We assessed the reliability of the data by checking for missing data or obvious errors and interviewing ACF officials about their processes for collecting and reporting these data. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this analysis. We reviewed ACF’s TANF financial expenditure reporting forms and guidance and interviewed ACF officials to determine which TANF expenditure reporting categories contained assistance expenditures, non-assistance expenditures, both assistance and non-assistance expenditures, program management expenditures, and transfers to other eligible block grants. See appendix I for a crosswalk of ACF TANF spending categories and the expenditure reporting categories we used in our analysis.

To review how selected states budget and allocate TANF funds, use non-governmental third-party expenditures to meet MOE spending requirements, ensure spending on non-assistance services meets the statutory purposes of TANF, and report on that spending to ACF, we reviewed federal laws and regulations that pertain to allocating TANF funds.[8] We reviewed ACF policies and guidance on budgeting and reporting on the use of TANF funds and relevant state appropriations laws and codes. We also reviewed state budget and process documents and interviewed officials in eight selected states: Illinois, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wyoming.[9] We selected these states for diversity in geographic region and range of percentage of the population in poverty. We analyzed ACF data on TANF uses in the selected states and interviewed state budget officials, state auditors, and state TANF agency officials from our selected states about their processes. While information from these selected states is not generalizable to all states, the information provides illustrative examples of how states have made spending decisions related to TANF funds.

To assess the extent to which ACF collects information on states’ use of TANF funds for oversight purposes, we assessed ACF’s oversight efforts against relevant federal laws and internal control standards. We reviewed regulations; ACF policies and guidance for budgeting, allocating, and reporting on TANF funds; and state expenditure reporting provided to ACF.[10] We also interviewed ACF officials about their processes for ensuring TANF expenditures were accurately reported.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

TANF Authorizing Legislation and Available Funds

TANF was created by the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA).[11] This law consolidated several programs serving needy families, including a cash assistance program for families with children, into the broad-purpose TANF block grant. The act specified that $16.5 billion be provided to the states each fiscal year in fixed federal TANF funding, an amount that generally has not increased since 1996.[12]

States have a variety of funding sources available to assist needy families as part of TANF (see fig. 1).

· Annual allocations of the $16.5 billion in federal funds to each state, called the State Family Assistance Grant, are based on federal expenditures under TANF’s precursor programs and do not change from year to year.

· A state may apply for and receive additional TANF Contingency Funds when unfavorable economic conditions exist in the state. In recent years, Congress has appropriated $608 million annually to be distributed to states qualifying for contingency funds.[13]

· A state may also have unspent TANF funds from previous years that are available for use in the current fiscal year.[14] States can indefinitely carry over federal TANF funds not spent in a given fiscal year for use in future fiscal years. Under HHS’s federal award regulations the states use two categories to report on the status of their unspent TANF funds: (1) unobligated balances represent funds not yet committed for a specific expenditure by a state, and (2) unliquidated obligations represent funds states have committed but not yet spent.[15] Both types of carried over funds are referred to throughout this report as unspent funds.

· A state must contribute its own MOE funds toward TANF purposes as a condition of receiving its full federal award. The MOE requirement for each state is set at 80 percent of the state’s spending on TANF’s precursor programs in 1994.[16] States generally have spent about $15 billion annually in total MOE in recent years.

Statutory Purpose and Eligible Uses of TANF

States can spend TANF’s State Family Assistance Grant, unspent TANF funds from previous years, contingency funds, and state MOE funds in any manner that is reasonably calculated to achieve TANF’s statutory goals:

· provide assistance to needy families so that children can be cared for in their own homes or in the homes of relatives;

· end the dependence of needy parents on government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage;

· prevent and reduce the incidence of out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and

· encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.[17]

TANF expenditures generally fall into two categories: assistance and non-assistance.

TANF Assistance Expenditures

TANF expenditures for assistance are often—but not exclusively—provided in the form of a monthly cash benefit.[18] Assistance expenditures include monthly cash payments to qualifying low-income families (also known as basic assistance), payments made to foster parents, and subsidies for adoption and guardianship. Assistance expenditures can also include expenditures for supportive services, such as child care for families who are not employed.

Under federal statute, only families with children, or families with a pregnant individual, who are financially needy may receive federal assistance, for up to 60 months.[19] States and U.S. territories have discretion to define certain eligibility requirements for assistance, including financial neediness, and to set benefit amounts.[20]

To receive their full federal TANF award, states must meet requirements associated with families receiving assistance. For example, states must meet a target work participation rate, which measures how well states engage families receiving assistance in work activities during a fiscal year.[21] States must also enforce other TANF program requirements, including sanctioning families with a member who refuses to work or participate in work activities, such as job skills training.[22]

TANF Non-assistance Expenditures

Non-assistance expenditures may include work supports and child care for working parents; pre-kindergarten; non-recurrent short-term benefits such as emergency housing payments; child welfare services; other services for children and youth; and services for prevention of out-of-wedlock pregnancies, fatherhood, and two-parent family formation and maintenance.[23]

Expenditures for non-assistance services have fewer federal requirements. Because states have discretion in determining which residents are eligible for individual non-assistance programs, these services can be made available to a larger population of state residents than assistance programs.

Other Allowable Uses of TANF

In addition to providing services, TANF funds can be transferred for use under the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) and the Social Services Block Grant (SSBG).[24] States may transfer up to 30 percent of their federal TANF award to CCDF and up to 10 percent of their federal TANF award to SSBG. Combined transfers to these two block grants cannot exceed 30 percent of a state’s annual federal TANF grant. Transferred funds are subject to the rules of the program to which they are transferred.[25]

States can also use TANF funds to pay for program management expenses incurred in providing TANF benefits and services. Certain administrative costs may not exceed 15 percent of a state’s total TANF expenditures.

Federal TANF Reporting Requirements

ACF collects and analyzes data that states report on TANF expenditures, work participation, and basic assistance caseload, among other things. To report on their planned and actual expenditures of federal TANF funds and state MOE funds, states complete the following:

· State Plans. States must have a complete or valid plan in place each fiscal year. The plan must have been submitted within the prior 27-month period. The plan explains how they intend to conduct a program that provides TANF assistance to needy families.[26] State plans must include an outline of the state’s basic assistance program.

· Quarterly Expenditure Reporting. States must submit quarterly reports to HHS on their expenditures of TANF funds by category on the Form ACF-196R.[27] For more information on TANF reporting categories, see appendix I.

· Annual Narrative Reporting on Certain Expenditures. States must submit annual narrative reports to ACF on the target population and types and amounts of benefits provided for certain expenditure categories on Form ACF-196R Part 2.[28]

· Annual MOE Reporting. States must submit annual reports to ACF with details on any programs contributing to their MOE expenditures using the Form ACF 204.[29]

ACF makes states’ TANF expenditure reporting publicly available annually, which includes the total amount spent in each expenditure category in a given fiscal year. ACF does not publish state plans or information collected from the annual narrative or MOE reporting.

Prior and Ongoing GAO Reviews of TANF

In April 2022, as part of our reporting on payment integrity of COVID-19 spending, we reported that HHS said it does not have the authority to obtain the information it needs to estimate or report improper payment information for its TANF program. We recommended that Congress consider providing HHS the authority to require states to report the data the agency needs to estimate and report on improper payments for TANF.[30] Beyond this report we are reviewing other aspects of TANF spending and monitoring, including (1) HHS’s efforts to manage fraud risks; (2) HHS’s oversight of TANF single audit findings; (3) selected states’ collection and use of TANF non-assistance data and HHS’s role in supporting these efforts; and (4) child welfare spending under TANF, including states’ use TANF funds as payments to foster and adoptive families and child welfare services. We will report on the results of these reviews in 2025.[31]

State Non-Assistance Spending and Unspent Funds Increased from 2015 to 2022

Non-Assistance Spending As a Share of All TANF Spending Increased between Fiscal Year 2015 and Fiscal Year 2022

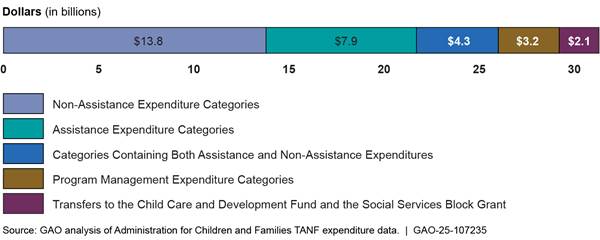

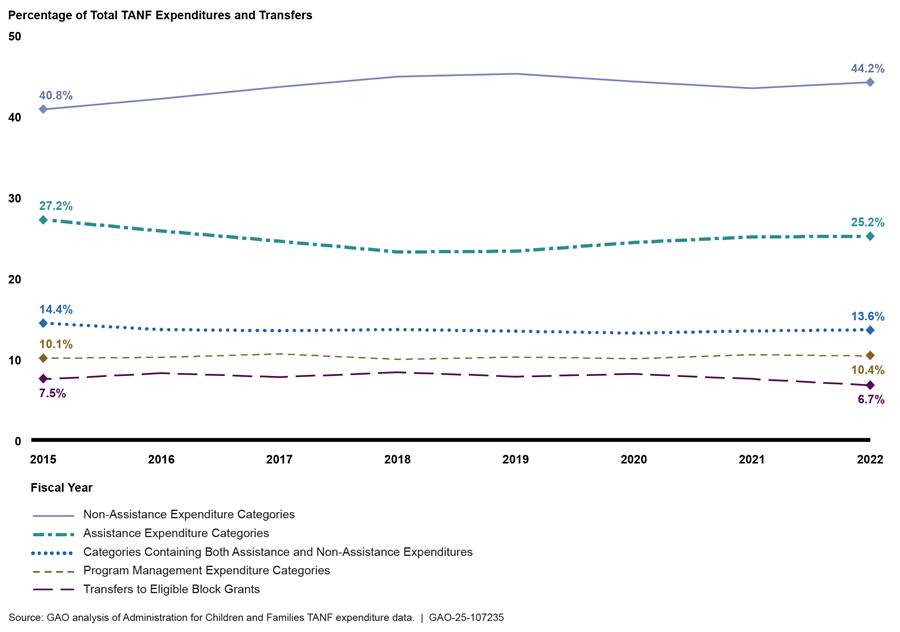

Nationwide, spending on non-assistance as a share of all TANF spending increased between fiscal year 2015 and fiscal year 2022, according to our analysis of ACF’s TANF expenditure data.[32] As shown in figure 2, states reported that they spent 40.8 percent of all TANF funds on non-assistance expenditures in fiscal year 2015 compared to 44.2 percent in fiscal year 2022. Spending on program management as a share of all TANF spending also increased, from 10.1 percent in fiscal year 2015 to 10.4 percent in fiscal year 2022.

Over the same period, spending on assistance and other expenditure categories decreased as a share of all TANF spending.

· Expenditures on assistance decreased from 27.2 percent to 25.2 percent.[33]

· Transfers to eligible block grants decreased from 7.5 percent to 6.7 percent.

· Spending in categories containing both assistance and non-assistance expenditures decreased from 14.4 percent to 13.6 percent.[34]

Figure 2: Change in Percentages of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Expenditures and Transfers by Category from Fiscal Year 2015 to Fiscal Year 2022

Note: States report expenditures of federal TANF and state maintenance of effort funds on Department of Health and Human Services Form ACF-196R. Eligible block grants are the Child Care and Development Fund and the Social Services Block Grant.

However, trends in individual states’ use of TANF funds may differ from nationwide trends because states have significant discretion in how they may use their TANF block grant funds. For example, according to our analysis, from fiscal year 2015 to fiscal year 2022 non-assistance spending increased in 22 states and the District of Columbia and decreased in 28 states. Over the same period, assistance spending increased in 12 states and the District of Columbia and decreased in 38 states. In 24 of those states, expenditures on total assistance decreased by more than 30 percent.

For more information on state-level TANF spending between fiscal year 2015 and fiscal year 2022, and to compare specific state spending to U.S. total spending (see the interactive link).

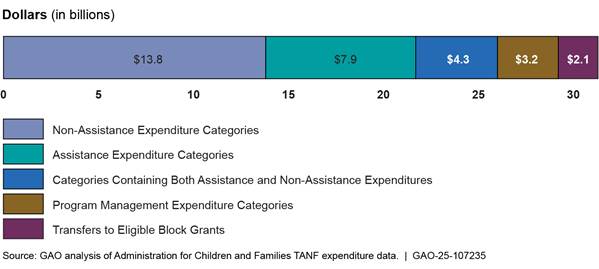

In fiscal year 2022, the most recent year of data available at the time of our analysis, states spent or transferred $31.3 billion of federal TANF and state MOE funds.[35] Figure 3 shows the amount of TANF funds states reported spending by expenditure category.

Figure 3: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Funds Spent or Transferred, Fiscal Year 2022

Note: States report expenditures of federal TANF and state maintenance of effort funds in Department of Health and Human Services Form ACF-196R. Eligible block grants are the Child Care and Development Fund and the Social Services Block Grant. In fiscal year 2022, 41 states and the District of Columbia transferred $2.1 billion to these block grants.

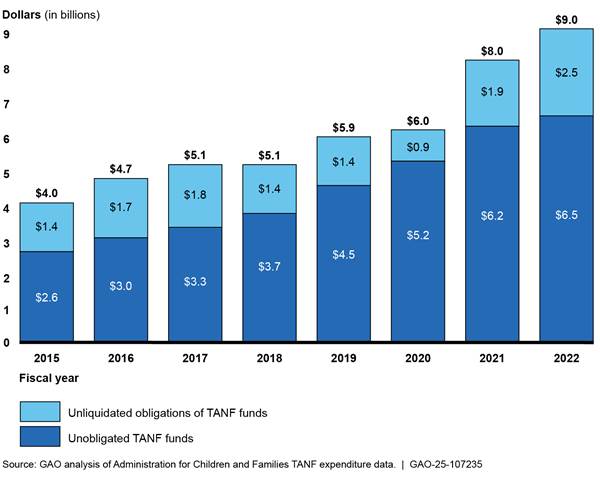

TANF Unspent Balances Increased between 2015 and 2022

From fiscal year 2015 to fiscal year 2022, total federal TANF funding carried over by states as unspent funds increased from $4 billion to $9 billion, as shown in figure 4.[36] This increase is the result of states, overall, spending less of their federal TANF funds during that period. In fiscal year 2022, a total of 45 states and the District of Columbia had an unspent balance, compared to 47 states and the District of Columbia in 2015. Reasons for increases in unspent funds in selected states are discussed later in this report. See appendix III for state-specific information on unspent TANF funds.

Figure 4: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Total Unspent Balances by All States, Fiscal Year 2015 to Fiscal Year 2022

Note: Under Department of Health and Human Services regulations, states use two categories to report on the status of their unspent TANF funds: (1) unobligated balances, which represent funds not yet committed for a specific expenditure by a state; and (2) unliquidated obligations, which represent funds states have committed but not yet spent. The sum of unobligated TANF funds and unliquidated obligations of TANF funds in the figure may not equal total unspent funds due to rounding.

Selected States Made TANF Budget and Transfer Decisions Based on Estimated Caseloads, Historical Precedent, and Legislative Priorities

Most Selected States Reported Estimating Basic Assistance Caseloads as Part of the TANF Budgeting Process

To determine how much to budget for basic assistance each year, six of eight selected states estimated their TANF caseloads—the number of individuals and families to whom they would provide TANF cash assistance—for the upcoming year. Officials in these six selected states described caseload estimates that incorporate economic conditions such as unemployment rates, state changes to eligibility requirements for TANF assistance, and historic expenditure data. The two other selected states told us they adjust their TANF spending throughout the year to meet basic assistance needs as they arise.

Officials in all our selected states told us that they were able to provide assistance to all eligible families who applied. In three of these selected states—New Mexico, New York, and Wyoming—officials told us that they prioritize funding basic assistance before making other TANF budget decisions. Officials in two states described several barriers that may dissuade some TANF-eligible families from applying for assistance, such as low benefit amounts offered in their states, the risk of being sanctioned and losing other program benefits, and work requirements.[37]

Selected States’ Non-Assistance Spending Decisions Reflect Legislative Priorities, Historical Precedent, and Local Needs

The state entities that are involved in identifying priorities for non-assistance funds varied by state and by type of decision. In some states, such as Ohio, the legislature may appropriate a portion of the state’s TANF funds for specific non-assistance programs. Alternatively, as in Mississippi, the legislature may authorize the state TANF agency to spend the state’s TANF funds, including for any non-assistance programs. Depending on the state, other state entities may also be involved, such as the state budget office, local social services departments, and other state programmatic agencies such as departments of child welfare or workforce development.

Decision-makers in our selected states told us that they considered a variety of factors when deciding how to spend TANF funds for non-assistance benefits and services.

· Legislative priorities. Legislative appropriations can direct TANF funds to specific non-assistance programs implemented by state agencies or non-governmental third-party organizations. For example, in recent years the Texas legislature has appropriated TANF funds to the state workforce agency to provide workforce training, and the New York legislature has appropriated funds for the state TANF agency to operate a summer youth employment program. In Wyoming, the legislature passed a statute that authorizes the state Department of Health to spend TANF funds on a public health nursing infant home visitation program. The Ohio legislature names individual food banks and after school programs operated by non-profits that will receive TANF funds in its appropriation bill.

· Historical precedent. Both legislative and state TANF agency officials relied on historical precedent to make decisions about which non-assistance services to provide with TANF funds. In some states, officials told us that legislative decisions for TANF are similar over time. For example, Texas officials told us that the legislature’s annual appropriations of TANF funds for state agencies providing TANF non-assistance services—such as the workforce training described above—are generally consistent year to year. Ohio officials told us that some organizations, such as the Ohio Fatherhood Commission, traditionally receive TANF non-assistance funds through the legislative appropriations process. Illinois statute specifies the amount of funds the Department of Human Services should transfer to the Department for Children and Family Services for child welfare, which Illinois officials told us was in part because these services were provided through TANF’s precursor programs.

State TANF agencies also used historical precedent to make decisions about TANF non-assistance programs. In Wyoming, officials told us that the Department of Family Services has historically focused on providing employment services. In Mississippi, state officials told us that the Department of Child Protection Services receives TANF funds to carry out the child welfare services it previously administered when it was part of the state TANF agency, the Department of Human Services.

· Local needs. State officials also told us they consider local needs in their states by developing geographically targeted programs or by leaving some TANF non-assistance decision-making to local social services departments. In Wyoming and Mississippi, the state TANF agency issues requests for proposals for programs that target TANF priorities in underserved geographic areas. In Wyoming, these programs include workforce programs, such as job training for low-income parents, and in Mississippi these programs include afterschool programs and parenthood initiatives. Both states provided examples of how they review proposals using criteria—including budgets, evaluation plans, and past performance—to make selection decisions.

In New York and Ohio, the state TANF agency operates a state-supervised, county-administered TANF program that provides both assistance and non-assistance benefits. In this model, the state determines the assistance and non-assistance benefits local social services districts can provide with TANF funds. The local social services departments have some discretion to expend TANF funds on the eligible assistance and non-assistance services that meet the needs of their communities.

· Flexibility of TANF funds. TANF’s statutory flexibility allows states to use TANF funds to pay for a variety of non-assistance benefits and services. For example, officials in New Mexico told us that their state’s legislature leveraged this TANF flexibility to support a child welfare program that is not yet eligible for Title IV-E Prevention Program funds.[38]

TANF’s flexibility also allows states to adjust the activities paid for by TANF versus other state or federal funds. In Illinois and Massachusetts, the state TANF agency identifies existing programs that meet the broad statutory purposes of TANF. These states then count expenditures on these eligible programs toward federal TANF funds or state MOE expenditures through the ACF financial reporting process.

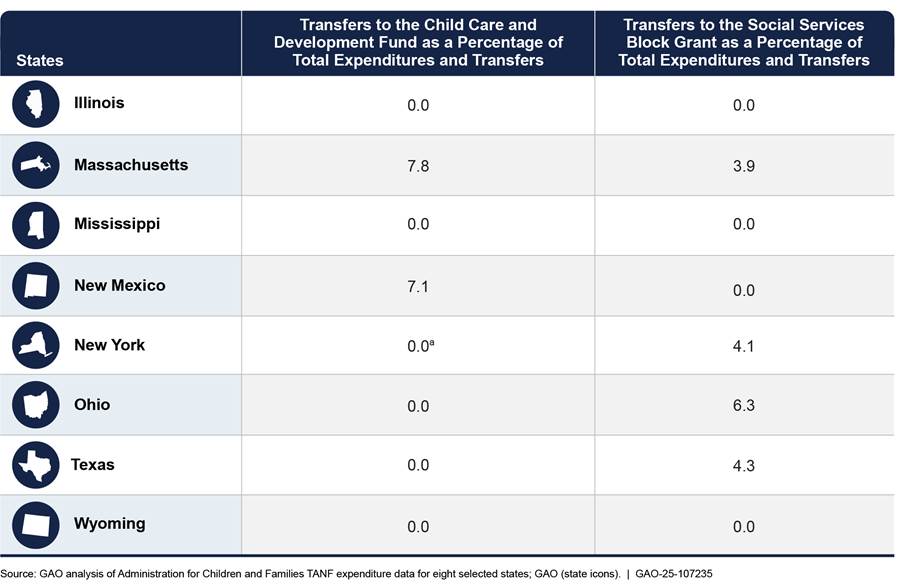

Selected States Transferred TANF Funds to Eligible Block Grants Based on Historical Precedent or State Agency Preferences

The amount of TANF funds selected states transferred to eligible block grants varied by state and by block grant. Three of our eight selected states transferred TANF funds to CCDF and four transferred TANF funds to the SSBG in fiscal year 2022, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Selected States’ Transfer of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Funds to Eligible Block Grants in Fiscal Year 2022, as a Percentage of Their TANF Expenditures and Transfers

Note: Total expenditures include spending from federal TANF funds and state maintenance of effort. Total transfers include federal TANF funds transferred to both eligible block grants. Eligible block grants are the Child Care and Development Fund and the Social Services Block Grant.

aNew York transferred 0.02 percent of its total expenditures and transfers to the Child Care and Development Fund, which rounds to 0.0.

The selected states took two approaches when deciding whether to transfer TANF funds to CCDF and SSBG. Four of these selected states told us they based decisions on whether to transfer TANF funds to other block grants based on historical precedent. For example, Massachusetts officials said that the state has traditionally transferred the maximum percentage of TANF funds to CCDF and SSBG.

The other four selected states decided whether to transfer TANF funds based on the preference of the agency or district receiving the transfer. For example, New Mexico officials told us that the state’s Early Childhood Education and Care Department prefers to receive TANF funds for child care through a transfer to CCDF. In contrast, Ohio officials said that they prefer to keep their TANF funds separate from CCDF so that the state retains flexibility to use the funds for uses other than child care. New York officials told us that local social services departments, which administer TANF programs at the county level, sometimes choose to transfer funds to SSBG.

Selected States Attributed Increases in Unspent Funds to Overestimation of Program Needs and Availability of Other Federal Funds

Most selected states we spoke with—regardless of whether they carried over unspent funds—told us they did not intentionally reserve TANF funds for future use. In half of these states—Mississippi, New York, Ohio, and Texas—unspent fund balances increased from fiscal year 2015 to fiscal year 2022. Two selected states, New Mexico and Wyoming, reduced the amount of unspent funds held between fiscal year 2015 and fiscal year 2022.[39]

Of the six selected states with unspent funds in fiscal year 2022, five of these states attributed their TANF unspent balances to subgrantees underspending their obligated funds. For example, Ohio officials told us that the state’s unliquidated obligations resulted from counties underspending the funds budgeted for their local TANF programs.

New York officials told us that, in addition to subgrantees underspending their obligated funds, state overbudgeting for assistance contributed to their unspent balance. New York budgeted for high expected TANF caseloads during the COVID-19 pandemic, but federal and state programs (e.g., federal relief funds, the federal child tax credit, and increases in unemployment insurance benefits) reduced the need for TANF basic assistance and resulted in unspent TANF funds.

The ability to carry over TANF funds indefinitely meant that some selected states prioritized budgeting and spending other time-limited federal funding, such as COVID-19 relief funds, before using TANF funds. For example, Texas officials said that the TANF unspent balance in their state has increased in recent years in part because the state prioritized spending down COVID-19 relief funds. Similarly, New York officials told us that an influx of time-limited federal funds for child care during the pandemic resulted in New York’s local social services departments underspending TANF funds they had originally budgeted for child care.

Some of our selected states described plans to spend down their TANF unspent balance. For example, Texas officials told us that the state plans to identify areas where it can allocate additional funds beyond its annual TANF award to spend down its TANF unspent balance. Ohio officials told us that they have been using the state’s TANF unspent balance to fund the remaining balance of the state’s child care program after all other resources are fully expended.

State officials told us that excess TANF funds afford states the opportunity to pay for eligible projects they may not otherwise be able to fund. For example, Wyoming officials told us that they are using part of Wyoming’s unspent balance to fund an employment support initiative for non-custodial parents, which officials said the state’s annual budget does not currently support. New York officials told us they plan to use the state’s unspent funds carried over during the pandemic to fund an increase in eligibility for subsidized child care and certain regional, one-time anti-poverty initiatives.

Few Selected States Used Non-Governmental Third-Party Expenditures to Satisfy Maintenance of Effort Requirements

Under current TANF regulations, states are allowed to count eligible expenditures made by non-governmental third parties, such as non-profit organizations, toward their annual TANF MOE requirements.

We found that two of the eight selected states, Ohio and New Mexico, used non-governmental third-party expenditures to help meet their MOE requirements in fiscal year 2023.[40]

· Ohio used non-governmental third-party expenditures for 8.8 percent of its MOE requirement in fiscal year 2023. All non-governmental third-party expenditures that Ohio counts toward its MOE are made by the Ohio Association of Foodbanks. Ohio’s Department of Job and Family has a memorandum of understanding with the Ohio Association of Foodbanks, and this document includes a format for the Association of Foodbanks to report its eligible expenditures. Specifically, the Ohio Association of Foodbanks submits information on the total value of dollars it spent and in-kind goods and services it provided, as well as the total population served by the foodbanks. Ohio’s Department of Job and Family Services officials told us they then identify the portion of the served population that is TANF eligible and use this figure to determine how much of the Association of Foodbanks’ total expenditures are eligible to be counted toward the MOE requirement.

· New Mexico used non-governmental third-party expenditures for 15 percent of its MOE requirement in fiscal year 2023. New Mexico officials said that they contact non-governmental organizations statewide to collect information on eligible non-governmental third-party expenditures. New Mexico provides a certification form, which asks organizations to list any social service programs they administer that meet the purposes of TANF. It also asks organizations to provide the total amount of non-federal funds used to fund these programs and the number of volunteer hours associated with each program. Officials said that in addition to completing the form, organizations also are to provide documentation to support their TANF program eligibility and total expenditures. New Mexico’s Health Care Authority then compiles the information to calculate the total amount of eligible non-governmental third-party expenditures.

In October 2023, ACF issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that, among other things, would prohibit states from counting non-governmental third-party expenditures to meet annual MOE requirements.[41] In our interviews with officials in Ohio, they did not express concern about their ability to meet annual MOE requirements should the final rule contain this provision. Officials in New Mexico said that disallowing the use of non-governmental third-party expenditures would decrease its overall reported MOE.

Selected States Have Various Processes for Reviewing and Confirming Statutory Eligibility of TANF Programs and Accuracy of Expenditure Reporting

Selected States Reviewed Statutory Eligibility of New Programs through Annual Appropriations and the Award of Grants and Contracts

All eight selected states described processes for reviewing and documenting the statutory eligibility of new proposed TANF expenditures or programs.

· Annual appropriations process reviews. Officials in four selected states said they confirm statutory eligibility of planned TANF programs and expenditures as part of the annual state appropriations process. For example, in New York, officials told us that the state budget office works with other state agencies during its budget formulation process to ensure proposed programs comply with the federal TANF requirements. In Texas, state officials said that staff of a joint legislative committee help determine whether proposed uses are allowable, and assist the state legislature in making TANF appropriations that comply with federal law.

In these four selected states, officials told us they document some assurances of statutory compliance in budget requests and other documents. For example, according to New Mexico state officials, budget requests and appropriations for TANF funds in that state must include language related to the statutory eligibility of the TANF expenditures proposed. Additionally, New Mexico’s state TANF agency completes an analysis of any bills containing new proposed uses of TANF funding, in part to determine whether the proposed uses comply with statutory purposes of TANF.

However, officials told us that eligibility of potential new TANF programs proposed by the legislature—programs not included in the state TANF agency’s budget request—is not always documented. Officials in some states described confirming statutory eligibility for these programs as part of negotiations during the budget process. For example, in Ohio, officials told us that any proposed legislatively directed spending of TANF funds is not part of the budget request, and therefore its statutory eligibility is not documented. In New York, while individual legislative priority programs funded with the state’s TANF grant may not be in the Governor’s proposed budget and are added by the legislature during negotiations, these programs are often continuations of existing programs and agencies ensure any required eligibility is documented. Officials in both states noted that the amount of TANF funding allocated to legislatively proposed programs is relatively small compared to the state’s overall grant.

· Vendor, grantee, and state agency reviews. Seven of our selected states told us they confirmed statutory eligibility for individual programs receiving TANF funds as part of their respective vendor and grant award processes or documented it through various types of agreements. Five selected states used a competitive process to select vendors to operate certain TANF-funded programs and noted that they confirm the proposed program will meet TANF eligibility requirements before awarding the grant or contract. In four selected states, officials said that the state TANF agency established interagency service agreements or memorandums of understanding with other state agencies receiving TANF funds and that these agreements document the eligibility of these programs.

Selected States Reported Monitoring TANF Programs for Ongoing Eligibility through Reimbursement Processes and Program Reviews

Each selected state told us they monitored ongoing programs receiving TANF funds for statutory compliance through expenditure reimbursements, program reviews, or both.

· Expenditure reimbursements. In seven selected states, staff at the state TANF agency told us they review invoices submitted by other state agencies or vendors to confirm TANF eligibility before issuing reimbursements.

· Individual program reviews. Officials in seven selected states said they used individual program reviews to confirm programs’ ongoing TANF eligibility. For example, officials in five selected states said staff at the state TANF agency meet with other state agencies and vendors on a regular or ad hoc basis to confirm any programs the agency or vendor operates continue to meet TANF eligibility requirements. Officials in two other states told us they rely on information vendors or districts submitted as part of reporting requirements to confirm a program’s ongoing TANF eligibility. In another state—Mississippi—state officials told us that as part of program changes, they implemented an initiative to conduct site visits to ensure vendor-operated programs continue to comply with the terms outlined in the vendor’s agreement with the state, including those programs’ eligibility under the statutory purposes of TANF.

· Other reviews. Rather than review programs on an individual basis, officials in Texas told us they review all programs for TANF eligibility as part of their process for developing the state TANF plan every 3 years.[42]

Selected States Have Processes to Review the Accuracy of TANF Expenditure Reporting

Selected states have various review processes in place to help ensure the accuracy of TANF expenditure reporting. In all our selected states, officials said the state TANF agency was responsible for federal TANF expenditure and MOE reporting. According to officials in these states, the state TANF agency reports to ACF on all expenditures and transfers of TANF funds for its state.

Officials from selected states described various types of review for accuracy.[43] Officials in five selected states told us they rely on coding within their state accounting system to compile expenditure information for the Form 196R. These states use program and activity codes within their accounting systems that crosswalk to the reporting categories on the Form 196R. In addition, state officials told us that several of these states have multiple officials review the reports for accuracy before they are submitted to ACF.

In one selected state—Massachusetts—officials told us they rely on preestablished queries of the state’s financial system to manually compile expenditure information. Officials revisit expenditures and activity codes at annual meetings with agencies to confirm spending and to ensure that the expenditures are still allowable and program activities are still relevant to federal TANF requirements.

In selected states in which the state TANF agency reimburses other state agencies or vendors, the state TANF agency is responsible for categorizing those reimbursements with the appropriate codes for federal reporting. Officials in Illinois described multiple levels of review for processing reimbursements for TANF expenses to state agencies, including intergovernmental agreements that require quarterly certifications attesting to the accuracy of the data and random testing on selected expenses to ensure they are TANF eligible. In some instances where expenditures are incurred by agencies other than the state TANF agency, those agencies may categorize their own expenditures. For example, in three selected states other state agencies report their expenditures by category to the state TANF agency, according to officials from those states.

ACF’s Existing Controls and Authorities for TANF Reporting Limit Oversight of State Spending

Not All States Submitted Complete Narratives for TANF Reports to ACF

ACF requires various forms of reporting on states’ TANF programs.[44] However, in our review of fiscal year 2022 reporting documentation for all states and the District of Columbia, we found that seven states submitted incomplete reports.

ACF provides detailed instructions on its website for states to complete the TANF quarterly expenditure reporting (Form ACF-196R). Using this

form, states report on their assistance and non-assistance expenditures by category. ACF also provides instructions on its website for states to complete their annual narrative reports to accompany the quarterly reports (Form ACF-196R Part 2). If states make expenditures in certain categories, they are required to provide narratives describing the nature of the spending, including information about the target population and the specific assistance provided.[45] For example, expenditures that do not clearly fall into any existing reporting categories are considered “other” expenditures and require a narrative report.

|

Administration for Children and Families (ACF) Required Reporting for States Receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Funds State Plans. States must have a valid plan on file each fiscal year with ACF that explains how they will conduct their TANF programs. The plan must have been submitted within the prior 27-month period. These plans must include an outline of the state’s basic assistance program. Quarterly Expenditure Reporting. States must submit quarterly reports to ACF on their expenditures of TANF funds by category in the Form ACF-196R. Annual Narrative Reporting on Certain Expenditures. States must submit annual reports to HHS on the target population and types and amounts of benefits provided for certain expenditure categories in Form ACF-196R Part 2. Annual Maintenance of Effort Reporting. States must submit annual reports to ACF with details on any programs contributing to the state’s maintenance of effort expenditures using the Form ACF-204. Source: GAO review of Administration for Children and Families forms. | GAO-25-107235 |

Our analysis of state submissions shows some incomplete reporting from states. For fiscal year 2022, 31 states had expenditures in at least one of three categories that required a narrative response and seven of those states had not submitted one or more required narrative response, according to reporting documentation from ACF in March 2024.[46]

ACF officials told us that it is aware of missing narrative reports and has processes to monitor state reporting.

· ACF officials explained that they use spreadsheets to track the status of required reporting for each state. ACF also provides additional training and technical assistance to states related to narrative report submissions. According to ACF officials, they prioritize states that have not provided required narratives.

· ACF officials told us they also review state submissions and work with states if submissions are incomplete. ACF officials explained that states can continue to submit narratives in response to ACF’s ongoing technical assistance to states.

However, these controls have not effectively ensured that states are providing the required narratives to support their expenditures. As described above, our analysis showed that seven of the 31 states that had narrative report requirements were still missing narratives 2 fiscal years after they were due.[47] ACF officials attributed problems with incomplete reports to challenges at the state level. ACF officials told us they face challenges with capacity of state employees who handle the TANF reporting, including obstacles with staff turnover and training. Specifically, they said they have encountered staff who are not aware of reporting deadlines, or how to submit reports in ACF’s reporting system.

Federal internal control standards require that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[48] Our identification of missing narratives in states’ TANF reporting indicates that ACF’s existing controls are inadequate. Improving the completeness of data that states should submit in their required TANF expenditure reporting should help ensure that TANF funds are spent properly and result in better information ACF can use to perform its statutorily authorized oversight role.

Reports ACF Requires from States Do Not Include Detail on Certain TANF Non-Assistance Expenditures

ACF requires states to submit plans outlining intended uses of TANF funds, as well as to regularly report on TANF expenditures and MOE spending. ACF officials told us they review the following reports for compliance. However, some of these reports do not require states to report certain details that could aid in HHS’s oversight of TANF spending.

· State plans. In their state plans submitted to ACF, states are not required to include any information on planned non-assistance programs or expenditures. Collecting more detail, such as information on how states plan to use their non-assistance funds, would allow ACF to better understand how states use TANF non-assistance funds and review planned spending to ensure these programs meet statutory purposes.[49]

· Quarterly expenditure reporting. In these reports, states are not required to include specific information on what expenditures are being reported in each category or detail on the programs and subgrantees that administer TANF-funded programs. Additionally, some reporting categories, such as Work Supports and Child Care, combine both assistance and non-assistance expenditures, which limits HHS’s ability to understand the extent to which states are using their TANF funds to assist needy families. More detailed information would help HHS ensure that all expenditures are being reported accurately by category and comply with the statutory purposes of TANF.

· Annual MOE reporting. The level of detail in annual MOE reporting varies from state to state, and states are not required to identify non-governmental third-party expenditures—expenditures by nonprofits and others—used to meet MOE requirements. This information could inform HHS of the extent to which states use non-governmental third-party expenditures to meet their MOE requirements and the potential effects of future policy changes to the requirements.[50]

Trends in state spending patterns, including continued increased spending on non-assistance programs, may require updates to current reporting requirements to enhance oversight. ACF officials told us that it is within their statutory authority to make some improvements to the type and amount of information collected from states. ACF officials last made changes to the TANF expenditure reporting forms in 2015. At that time, ACF created more detailed expenditure reporting categories and modified their accompanying definitions to increase the transparency and accuracy of TANF financial data. Officials said that they could work with their Office of General Counsel to determine the extent of additional changes they can make to their data collection while remaining within their authority.

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 created a TANF oversight role for ACF.[51] Under that statute, ACF’s role includes reviewing required reporting and, when appropriate, assessing penalties.[52] Federal internal control standards require that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives. Reviewing its current reporting requirements within its existing authorities and making any appropriate changes could help ACF ensure the information it requires from states is adequate for its oversight purposes, potentially including that of improper payments, and to make any needed changes to the program.

However, ACF officials face limits to their ability to request certain additional information from states. TANF’s authorizing legislation prohibits oversight of state TANF programs beyond what is explicitly required in the law.[53] According to HHS, all data collection actions it may take are outlined in Sec. 411 of the Social Security Act.[54] HHS has interpreted this to mean that it cannot collect any data not expressly listed, nor can it request data in areas where it lacks explicit authority. ACF officials confirmed that the legislation authorizing HHS’s oversight of TANF does not specifically allow it to request information on:

· planned uses of TANF funds beyond the state’s basic assistance program,

· the amount of TANF funds the state anticipates directing to various programs (including basic assistance and non-assistance),

· the amount of TANF funds the state directs to each individual program, or

· the amount of the state’s MOE met by non-governmental third-party expenditures.

ACF officials also said that expanded statutory authority could potentially allow them to collect more granular expenditure information on subrecipients of TANF funds. In its fiscal year 2024 and 2025 budget requests for ACF, HHS included a legislative proposal requesting enhanced authority to collect more comprehensive data on TANF and MOE expenditures made to non-governmental subgrantees to improve monitoring on TANF expenditures and activities, including to develop an improper payment rate for TANF.[55] We have also previously recommended in 2012 that Congress consider ways to improve reporting and program performance information so that it encompasses the full breadth of states’ uses of TANF funds. While Congress took some initial steps to reform TANF in 2016, no legislation was passed and Congress has not made changes to the reporting requirements.[56]

For purposes of ACF oversight of TANF, by granting additional authorities for ACF to collect information related to states’ use of non-assistance funds, and other data as appropriate, Congress could enhance ACF’s ability to monitor and ensure more comprehensive oversight of billions of TANF dollars. Greater detail would also provide additional information for policymakers’ decision-making regarding the TANF program.

Conclusions

TANF’s statutory flexibilities allow states to fund a broad set of programs to address poverty, reduce child welfare involvement, and meet the specific needs of their diverse communities.

ACF requires and reviews state planning documents, quarterly expenditure reporting, annual narrative reporting on certain expenditures, and annual MOE reporting. However, not all states submitted complete sets of required reports, according to our review of state reporting in fiscal year 2022. By designing control activities to improve the completeness of required reporting, ACF would further ensure that states report on their use of TANF funds in a comprehensive way that adheres to existing requirements and enhances oversight.

HHS’s statutory authority to request more data and information from states is limited. However, exercising its existing authorities by reviewing and updating its current reporting could strengthen its ability to oversee and ensure the accountability of TANF funds. Further, granting HHS authority to collect more detailed TANF program and expenditure information from states such as planned and actual TANF non-assistance expenditures, as appropriate, could strengthen its oversight and provide additional context for future decision making regarding the TANF program.

Matter for Congressional Consideration

We are making the following matter for congressional consideration:

Congress should consider granting HHS the authority to collect from states specific additional information needed to enhance its oversight authority, such as planned and actual TANF non-assistance expenditures, beyond what is provided for in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996. (Matter for Consideration 1)

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to ACF:

The Secretary of HHS should ensure ACF design control activities to help ensure states are submitting complete narrative data in their expenditure reporting. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of HHS should ensure ACF conducts a review of all TANF reporting requirements and forms and make appropriate changes within its statutory authority to enhance reporting for oversight of TANF funds. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. In its written comments, which are reproduced in appendix IV, HHS concurred with our recommendations. HHS stated that it will continue to improve on its monitoring and training efforts to ensure timely submission of required reporting. HHS also said it will review reporting forms to improve the quality and comprehensiveness of TANF data within its statutory authority. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We also provided excerpts of the draft report to cognizant staff of state TANF agencies in Illinois, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Wyoming. The selected states provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-6806 or arkinj@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Jeff Arkin

Director, Strategic Issues

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children and Families (ACF), requires states and the District of Columbia to complete Form ACF-196R on their expenditures of federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant funds and state maintenance of effort funds. Reporting is organized into categories for expenditures and transfers.

For the purposes of our reporting, we identified five expenditure groups based on ACF’s Form ACF-196R instructions: (1) assistance expenditure categories, (2) non-assistance expenditure categories, (3) categories containing both assistance and non-assistance expenditures, (4) program management expenditure categories, and (5) transfers to eligible block grants.

Assistance Expenditure Categories

HHS regulations define assistance to include cash, payments, vouchers, and other forms of benefits designed to meet a family’s ongoing basic needs (i.e., for food, clothing, shelter, utilities, household goods, personal care items, and general incidental expenses).[57] These benefits may be conditioned on participation in work activities such as work experience or community service.

Non-Assistance Expenditure Categories

HHS regulations exclude other benefits and services from the definition of assistance, creating another group of expenditures referred to as non-assistance. Non-assistance includes work subsidies, supportive services such as child care and transportation provided to families who are employed, refundable earned income tax credits, and services such as employment counseling and case management.[58] Non-assistance expenditures also include nonrecurrent, short-term benefits that are designed to deal with a specific crisis situation or episode of need, are not intended to meet recurrent or ongoing needs, and will not extend beyond 4 months.

Categories Containing Both Assistance and Non-Assistance Expenditures

Child care and supportive services such as transportation are considered either assistance or non-assistance depending on whether the recipient family is employed (in which case the services are non-assistance) or not employed (in which case the services are assistance).

Table 1: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Expenditure Groups and Expenditure Reporting Categories

|

Expenditure group |

Form ACF-196R reporting category |

Examples of selected expenditures within this category |

|

Assistance expenditures

|

Basic Assistance (excluding Relative Foster Care Maintenance Payments and Adoption and Guardianship Subsidies) |

Cash, payments, and other forms of benefits designed to meet a family’s ongoing basic needs. |

|

|

Relative Foster Care Maintenance Payments and Adoption and Guardianship Subsidies |

Basic assistance provided on behalf of a child involved in the state’s child welfare system who is living with a caretaker relative. Also includes adoption subsidies. |

|

|

Foster Care Payments Authorized Solely under Prior Law |

Basic assistance provided on behalf of a child involved in the state’s child welfare system who is in foster care, authorized solely under section 404(a)(2) of the Social Security Act and referenced in a state’s former Aid to Families with Dependent Children or Emergency Assistance plan. |

|

|

Juvenile Justice Payments Authorized Solely under Prior Law |

Basic assistance payments on behalf of children in the state’s juvenile justice system, authorized solely under section 404(a)(2) of the Social Security Act and referenced in a state’s former Aid to Families with Dependent Children or Emergency Assistance plan. |

|

|

Emergency Assistance Authorized Solely under Prior Law |

Other benefits authorized solely under section 404(a)(2) of the Social Security Act and referenced in a state’s former Aid to Families with Dependent Children or Emergency Assistance plan. |

|

Non-assistance expenditures |

Juvenile Justice Services Authorized Solely under Prior Law |

Juvenile justice services provided to children, youth, and families, authorized solely under section 404(a)(2) of the Social Security Act and referenced in a state’s former Aid to Families with Dependent Children or Emergency Assistance plan. |

|

|

Emergency Services Authorized Solely under Prior Law |

Other services authorized solely under section 404(a)(2) of the Social Security Act and referenced in a state’s former Aid to Families with Dependent Children or Emergency Assistance plan. |

|

|

Child Welfare or Foster Care Services Authorized Solely under Prior Law |

Services provided to children and their families involved in the state’s child welfare system, authorized solely under section 404(a)(2) of the Social Security Act and referenced in a state’s former Aid to Families with Dependent Children or Emergency Assistance plan. |

|

|

Child Welfare Services |

Services designed to strengthen families so that children can be cared for in their own homes, including family counseling, parenting skills classes, and case management. Services and activities designed to promote and support successful adoptions. Other services provided to children and families involved in or at risk of being involved in the child welfare system. |

|

|

Work, Education, and Training Activities |

Payments to employers or third parties to cover the costs of employee wages, benefits, supervision or training, job search assistance, and job readiness services. Expenditures on education and training activities, including secondary education, job skills training, and postsecondary education. |

|

|

Pre-Kindergarten/ Head Start |

Pre-kindergarten or kindergarten education programs, expansion of Head Start programs, or other school readiness programs. |

|

|

Financial Education and Asset Development |

Programs and initiatives designed to support the development and protection of assets including contributions to Individual Development Accounts, financial education services, tax credit outreach campaigns and tax filing assistance programs, and credit and debt management counseling. |

|

|

Refundable Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC) |

Refundable portion of state or local EITCs paid to families that are consistent with TANF regulations. |

|

|

Non-EITC Refundable State Tax Credits |

Refundable portion of other tax credits provided under state or local law that are consistent with TANF regulations. |

|

|

Non-Recurrent Short-Term Benefits |

Short-term payments to families to deal with a specific crisis situation or period of need, such as emergency housing, short-term utilities payments, and back-to-school payments. |

|

|

Supportive Services |

Services such as domestic violence services; health, mental health, substance abuse and disability services; housing counseling services; and other family supports. |

|

|

Services for Children and Youth |

Programs designed to support and enrich the development and improve the life-skills and educational attainment of children and youth. This may include after-school programs and mentoring or tutoring programs. |

|

|

Prevention of Out-of-Wedlock Pregnancies |

Programs that provide sex education or abstinence education to pre-teens and teens and education and family planning services to individuals, couples, and families to reduce out-of-wedlock pregnancies. |

|

|

Fatherhood and Two-Parent Family Formation and Maintenance Programs |

Programs that promote responsible fatherhood or encourage the formation and maintenance of two-parent families, such as parent and marriage skills workshops and public advertising campaigns. |

|

|

Home Visiting Programs |

Programs where nurses, social workers, or other professionals provide services to families in their homes, such as providing information and guidance around maternal health and child health and development and connecting families to necessary resources and services. |

|

|

Other |

Non-assistance activities not otherwise enumerated. States including expenditures on this line must provide a description of the specific benefits and services provided and the target population in their submission of Form ACF-196R Part 2. |

|

Categories containing both assistance and non-assistance expenditures |

Work Supports |

Assistance and non-assistance transportation benefits provided to help families obtain, retain, or advance in employment. Goods provided to individuals to help them obtain or maintain employment, such as tools, uniforms, and licensing fees. |

|

|

Child Care |

Child care assistance and non-assistance expenditures for families that need child care to work or participate in work activities. |

|

Program management expenditures |

Program Management |

Administrative costs associated with contracts and subcontracts, Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income application services, case planning and management, and certain direct service provision. Costs related to monitoring and tracking under the program, such as costs for information technology. |

|

Transfers to eligible block grants |

Transferred to Child Care and Development Fund Discretionary |

Funds transferred to the Child Care and Development Fund. These funds are subject to the rules and regulations of the Child Care and Development Fund in place for the federal fiscal year at the time when the transfer occurs. A state can only transfer current-year federal TANF funds. |

|

|

Transferred to Social Services Block Grant |

Funds transferred to the Social Services Block Grant. These funds are subject to the statute and regulations of the Social Services Block Grant program in place for the federal fiscal year at the time when the transfer occurs and are only to be used for programs and services to children or their families whose income is less than 200 percent of the income official poverty line as defined by the Office of Management and Budget. A state can only transfer current-year federal TANF funds. |

Source: GAO analysis of Administration for Children and Families TANF expenditure reporting instructions. | GAO‑25‑107235

Appendix II: Territorial Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Financial Reports, Fiscal Year 2022

U.S. territories report quarterly on their expenditures of federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds and territorial maintenance of effort on Form ACF-196TR. Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands participate in TANF and receive federal TANF funds; American Samoa is eligible but does not participate in TANF; and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands is not eligible for TANF.

Territorial reporting for TANF expenditures differs from that of states. States report quarterly on expenditures of TANF funds made within the current fiscal year. Territories report quarterly on their cumulative expenditures for each open grant year since the first day of the award. If a territory needs to make corrections to past reporting, the territory makes those changes in the next quarterly report, rather than revising old reports.

Form ACF-196TR, which collects territorial TANF expenditure data, also categorizes some TANF expenditures differently from Form ACF-196R, which is used to collect state TANF expenditure data. Territories report on assistance and non-assistance expenditures separately, while states have combined reporting for certain categories—child care, transportation, and other supportive services—that may contain both assistance and non-assistance expenditures.

Unlike states, territories report separately on expenditures for individual development accounts.[59] For states, such expenditures are included as part of the state’s reporting category for financial education and asset development expenditures. Territories also do not report expenditures for home visiting programs in their own category.

Territorial reporting on TANF expenditures for child welfare is less granular than that for states. Territories have three reporting categories for child welfare expenditures: relative foster care maintenance payments and adoption and guardianship subsidies, assistance authorized solely under prior law, and non-assistance authorized solely under prior law. Meanwhile, states have six reporting categories for child welfare expenditures: basic assistance, including relative foster care maintenance payments and adoption and guardianship subsidies; assistance authorized solely under prior law including foster care payments; non-assistance authorized solely under prior law including child welfare or foster care services; child welfare services including family support, family preservation, and reunification services; adoption services; and additional child welfare services.

Form ACF-196TR also collects expenditure data for federal Aid to Aged, Blind, or permanently and totally Disabled persons (AABD) programs under Titles I, X, and XIV, or XVI of the Social Security Act. AABD is similar to the adult assistance programs that preceded Supplemental Security Income, which is not available in the territories.

Data on territorial expenditures of TANF funds have not previously been publicly reported. The tables below show TANF spending in fiscal year 2022 by category for Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Table 2: Guam Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Financial Report, Fiscal Year 2022, Grant Year 2016 to Grant Year 2022

|

Spending Category |

(A) Federal TANF |

(B) Territory Funds |

(C) Territory Programs Maintenance of Effort |

(D) TANF and All Maintenance of Effort Combined |

|

1. Awarded |

$3,454,042 |

$0 |

$0 |

$3,454,042 |

|

2. Transfer to Child Care and Development Fund Discretionary Fund |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

3. Transfer to Social Services Block Grant |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

4. Available for Expenditure |

$24,189,732 |

$0 |

$0 |

$24,189,732 |

|

5. Expenditures on Assistance |

$0 |

$947,202 |

$0 |

$947,202 |

|

(A). Basic Assistance |

$0 |

$947,202 |

$0 |

$947,202 |

|

(B). Child Care |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(C). Transportation and Other Supportive Services |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(D). Under Prior Law |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(E). Relative Foster Care Maintenance Payments and Adoption and Guardianship Subsidies |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

6. Expenditures on Non-Assistance |

$633,427 |

$0 |

$0 |

$633,427 |

|

(A). Work-Related Activities and Expenses |

$483,756 |

$0 |

$0 |

$483,756 |

|

1. Subsidized Employment |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

2. Education and Training |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

3. Other Work Activities/Expenses |

$483,756 |

$0 |

$0 |

$483,756 |

|

(B). Child Care |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(C). Transportation |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

1. Job Access |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

2. Other Transportation |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(D). Individual Development Accounts |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(E). Refundable Earned Income Tax Credits |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(F). Other Refundable Tax Credits |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(G). Non-Recurrent Short-Term Benefits |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(H). Prevention of Out-of-Wedlock Pregnancy |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(I). Two-Parent Family Formation and Maintenance |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(J). Administration |

$114,000 |

$0 |

$0 |

$114,000 |

|

(K). Systems |

$35,671 |

$0 |

$0 |

$35,671 |

|

(L). Non-Assistance Authorized Solely under Prior Law |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(M). Other |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

10. Total Expenditures |

$633,427 |

$947,202 |

$0 |

$1,580,629 |

|

11. Federal Unliquidated Obligations |

$225,019 |

$0 |

$0 |

$225,019 |

|

12. Unobligated Balance |

$18,594,997 |

$0 |

$0 |

$18,594,997 |

Source: GAO analysis of Administration for Children and Families TANF expenditure data. | GAO‑25‑107235

Note: Lines 7, 8, and 9 of Form ACF-196TR collect expenditure data for federal Aid to Aged, Blind, or permanently and totally Disabled persons programs. These expenditures are not applicable to TANF funding and are not included in the table above.

Table 3: Puerto Rico Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Financial Report, Fiscal Year 2022, Grant Year 2016 to Grant Year 2022

|

Spending Category |

(A) Federal TANF |

(B) Territory Funds |

(C) Territory Programs Maintenance of Effort |

(D) TANF and All Maintenance of Effort Combined |

|

1. Awarded |

$71,326,346 |

$0 |

$0 |

$71,326,346 |

|

2. Transfer to Child Care and Development Fund Discretionary Fund |

$7,132,634 |

$0 |

$0 |

$7,132,634 |

|

3. Transfer to Social Services Block Grant |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

4. Available for Expenditure |

$451,768,059 |

$0 |

$0 |

$451,768,059 |

|

5. Expenditures on Assistance |

$26,476,672 |

$4,375,173 |

$0 |

$30,851,845 |

|

(A). Basic Assistance |

$26,019,170 |

$4,375,173 |

$0 |

$30,394,343 |

|

(B). Child Care |

$94,830 |

$0 |

$0 |

$94,830 |

|

(C). Transportation and Other Supportive Services |

$362,672 |

$0 |

$0 |

$362,672 |

|

(D). Under Prior Law |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

(E). Relative Foster Care Maintenance Payments and Adoption and Guardianship Subsidies |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

6. Expenditures on Non-Assistance |

$4,530,086 |

$13,311,112 |

$0 |

$17,841,198 |

|

(A). Work-Related Activities and Expenses |

$796,127 |

$2,268,080 |

$0 |

$3,064,207 |

|

1. Subsidized Employment |

$55,443 |

$0 |

$0 |

$55,443 |

|

2. Education and Training |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

3. Other Work Activities/Expenses |

$740,684 |

$2,268,080 |

$0 |

$3,008,764 |

|

(B). Child Care |

$247,018 |

$0 |

$0 |

$247,018 |

|

(C). Transportation |

$8,453 |

$0 |

$0 |

$8,453 |

|

1. Job Access |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

$0 |

|

2. Other Transportation |

$8,453 |

$0 |

$0 |

$8,453 |