COAST GUARD

Better Feedback Collection and Monitoring Could Improve Support for Duty Station Rotations

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-107238

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107238. For more information, contact Heather MacLeod at (202) 512-8777 or MacLeodH@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107238, a report to congressional committees.

November 2024

COAST GUARD

Better Feedback Collection and Monitoring Could Improve Support for Duty Station Rotations

Why GAO Did This Study

To conduct its missions, the Coast Guard assigns service members to numerous locations within and outside the continental U.S., including aboard ships.

A committee report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review the Coast Guard rotations process and how DOD supports that process. This report addresses the extent to which the Coast Guard identified challenges with rotations and has taken action to address them, among other things.

GAO analyzed Coast Guard and DOD policies and guidance on rotations. GAO also interviewed DOD and Coast Guard officials, including geographically dispersed field unit officials from all nine Coast Guard districts. The information GAO obtained from these interviews is not generalizable, but provided insights and context concerning how the Coast Guard monitors and addresses rotation challenges experienced by service members.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making two recommendations, including that the Coast Guard establish a process to routinely collect and analyze service-wide feedback on rotations. The Coast Guard agreed with the recommendation. DOD partially agreed with GAO’s other recommendation. GAO maintains that the recommendation is warranted, as discussed in the report.

What GAO Found

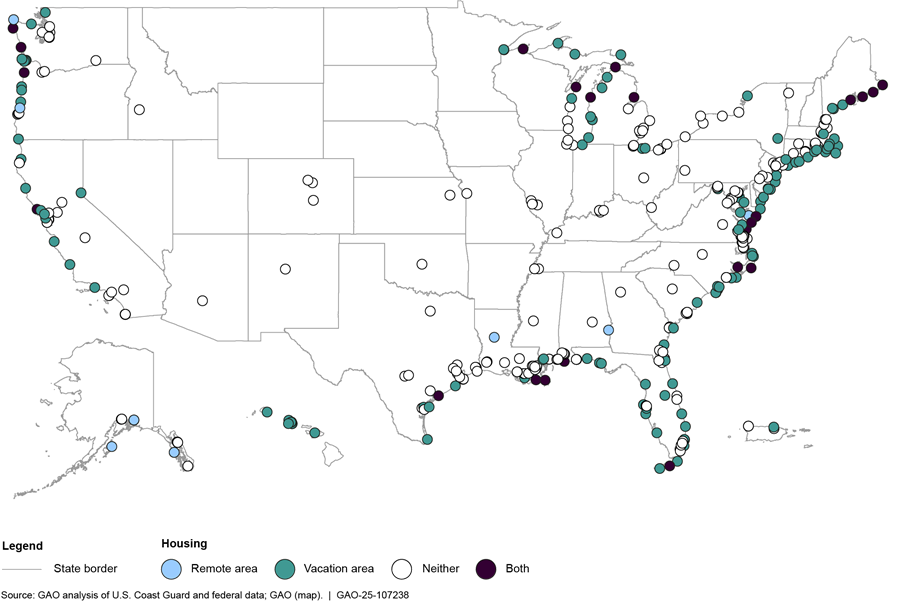

The Coast Guard annually rotates over 40 percent of its 40,000 active-duty military personnel to new duty stations. Around 41 percent of Coast Guard units are in remote areas or high vacation rental areas (such as Cape Cod, Massachusetts), or both. U.S. Transportation Command, within the Department of Defense (DOD) administers the shipment and storage of service members’ household goods, including for Coast Guard personnel, through the Defense Personal Property Program.

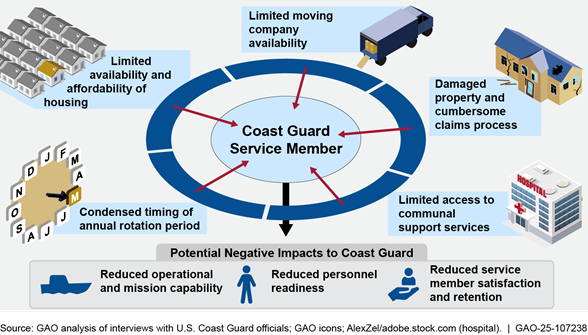

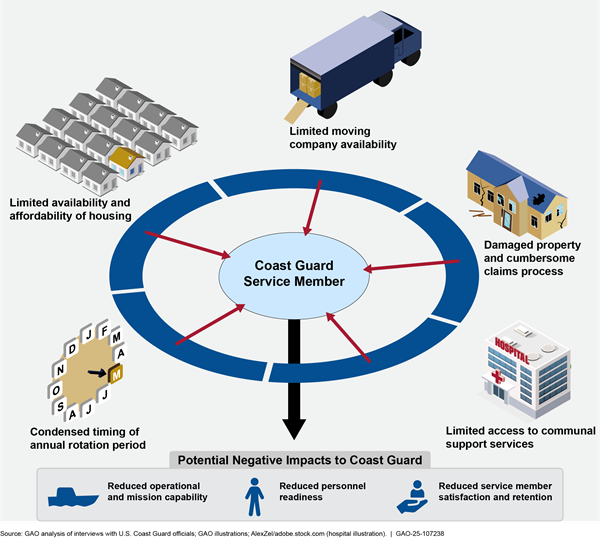

Officials from the nine Coast Guard districts told GAO that service members can experience key challenges when rotating to new duty stations. These challenges included limited moving company availability and access to specialized health care (see figure below). Officials told GAO that these challenges can have potential negative impacts on Coast Guard operations, personnel readiness, and retention. For example, delays in arrivals of newly assigned members to replace rotated members can increase workloads for those stationed at some units. Additionally, some newly assigned members may not be able to fully participate in mission-related duties before taking care of personal issues like obtaining dependent care. The Coast Guard has taken some actions to address these challenges, such as helping with researching available places to rent.

While the Coast Guard has mechanisms that may collect information on challenges experienced by service members, they are not specifically intended to do so. For example, members may communicate feedback on rotations when preferencing new assignments. However, the Coast Guard does not have a process for collecting service-wide feedback about duty station rotations. Establishing a process to routinely collect and analyze such feedback would position the Coast Guard to better understand rotation challenges and their impact on operations, readiness, and retention, as well as meet service member needs.

Abbreviations

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

TRANSCOM |

U.S. Transportation Command |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 18, 2024

The Honorable Jack Reed

Chairman

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

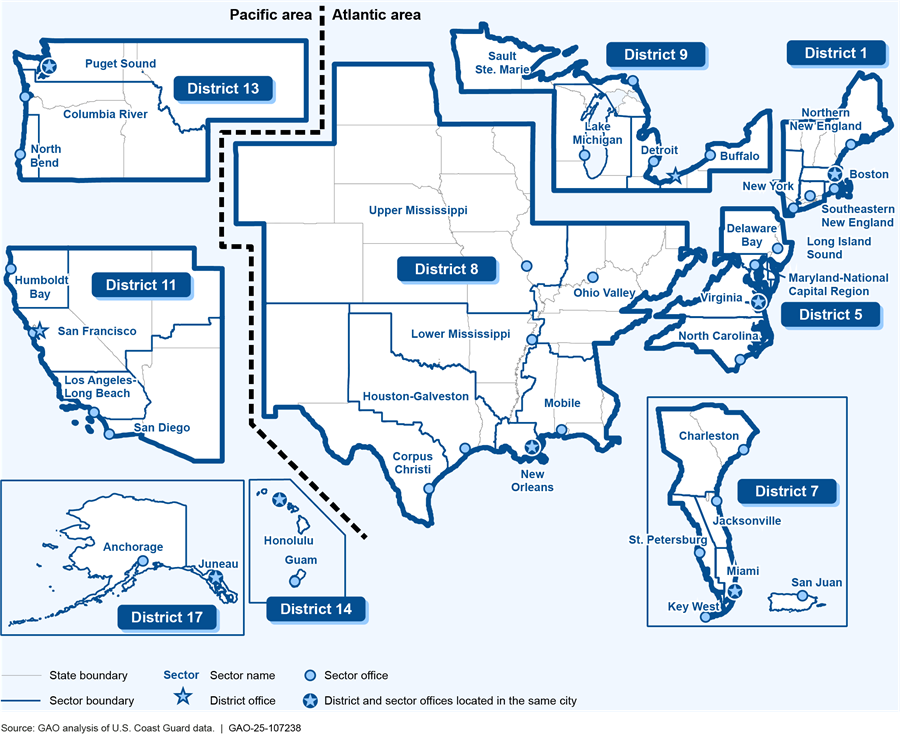

As a multi-mission service within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Coast Guard deploys about 40,000 active-duty military personnel to numerous locations within and outside the continental U.S. These personnel conduct missions, such as search and rescue and marine environmental protection.[1] To conduct its missions, the Coast Guard assigns service members to duty stations at a wide range of operating locations, including aboard ships. Coast Guard personnel, and often their families, must reside near its operating locations, including along the east and west coasts of the continental U.S., along the Great Lakes, and in rural and remote areas such as Maine and Port Angeles, Washington.[2] We recently reported that around 41 percent of Coast Guard units are in remote or high vacation areas, or both (see figure 1).[3]

Figure 1: Coast Guard Units Located in Areas that are Remote, Contain Majority High Vacation Rentals, or Both, as of 2023

The Coast Guard annually rotates about 3,300 officers and between 14,000 to 15,000 enlisted Coast Guard service members to new permanent duty stations, according to officials.[4] This equates to over 40 percent of the Coast Guard’s active-duty workforce. Creating opportunities for flexible assignments and providing adequate individual and family support services for service members, particularly in areas considered remote, is a key element of the Coast Guard’s efforts to enhance service member quality-of-life, morale, recruiting, and retention. We have previously reported on the Coast Guard’s recruitment and retention challenges, and on challenges with the affordability and availability of housing for service members.[5] We recommended the Coast Guard establish a process to collect and use service-wide housing feedback from service members and spouses on a routine basis, which the Coast Guard is in the process of addressing.

A committee report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision that we review the Coast Guard duty station rotations process and how the Department of Defense (DOD) supports that process.[6] This report addresses: (1) how the Coast Guard and DOD support Coast Guard duty station rotations; (2) Coast Guard and DOD costs for supporting duty station rotations for Coast Guard service members; (3) how DOD measures service member satisfaction with personal property shipments during rotations; and (4) the extent to which the Coast Guard has identified challenges with the duty station rotations process and has taken action to address them.

To address all four objectives, we reviewed relevant guidance and policies from the Coast Guard related to the administration of duty station rotations, including the Coast Guard’s Military Assignments and Authorized Absences manual, Pay Manual, and Supplement to the Joint Travel Regulations.[7] We also reviewed relevant DOD guidance related to travel and personal property shipments for service members, including the Joint Travel Regulations and Defense Transportation Regulations.[8]

For our first objective, we analyzed the policies and practices the Coast Guard and DOD employ, including the information collected and used in the management of duty station rotations for Coast Guard service members. In addition, we interviewed officials with responsibilities related to the administration of duty station rotations. Specifically, we met with Coast Guard headquarters officials from the Personnel Service Center, Logistics Command, and Office of Military Personnel Policy.[9] In addition, we interviewed officials from relevant DOD components, including the U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM), Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Military Personnel Policy and the Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Logistics.[10]

For our second objective, we analyzed Coast Guard and DOD’s reported expenditures for supporting duty station rotations of Coast Guard service members. Specifically, this included DOD shipment and expenditure data related to administering the Defense Personal Property Program and Coast Guard expenditures for personal property shipments coordinated through the program. We reviewed data from fiscal years 2019 through 2023 to ensure we considered the most recent five-year period and included data captured before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic.[11] We used the provided data to generate summary statistics about shipments and rotation-related costs for both DOD and the Coast Guard.[12] During this process, we manually assessed the data for accuracy and followed up with Coast Guard and DOD officials to validate our calculations and the reliability of the reported data. Based on interviews with knowledgeable Coast Guard and DOD officials and our review of officials’ responses to data reliability questions, we determined that both the Coast Guard and DOD expenditure data were sufficiently reliable to identify trends in costs related to duty station rotations.

For our third objective, we analyzed DOD customer service satisfaction survey data for Coast Guard personal property shipments conducted through the Defense Personal Property Program from fiscal years 2019 through 2023. To assess the reliability of data and identify any limitations, we calculated Coast Guard survey response rates, reviewed relevant survey documentation, and interviewed knowledgeable DOD officials about their survey administration and data collection efforts. Based on these efforts, we determined that only Coast Guard customer satisfaction data for fiscal year 2023 were sufficiently reliable for reporting. We compared the Coast Guard’s efforts to assess the quality of the survey data to our key practices.[13] Where appropriate, we also compared TRANSCOM’s process to collect and use customer satisfaction data against government standards and federal statistical policies.[14]

For our fourth objective, we conducted interviews with field unit officials from all nine Coast Guard districts, including district command officials, base officials, and transportation officers.[15] During the interviews we used standardized questions regarding unit and personnel readiness, the rotation process, and feedback from Coast Guard service members on their moves. Based on the responses, we identified general themes about duty station rotation-related challenges experienced by service members in their districts’ respective geographic areas of responsibility. The information we obtained from these interviews is not generalizable, but it provides insights and context concerning how the Coast Guard monitors and addresses rotation challenges experienced by service members.

In addition, we reviewed the Coast Guard’s efforts to collect and use different types of information to help manage duty station rotations, including service member feedback on rotation-related challenges. We determined that the information and communication component of internal control was significant to this objective, along with the underlying principles that management should use quality information and communicate the necessary quality information to achieve objectives, as described in Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[16] Where appropriate, we reviewed the Coast Guard’s process to collect and use service member feedback to determine the extent to which the Coast Guard used these underlying principles for decision-making.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of Coast Guard Duty Station Rotation Process

Rotation Process. The Coast Guard’s duty station rotation process consists of two phases: (1) assignment administration and (2) member travel and personal property shipments. During the first phase, the Coast Guard Personnel Service Center in headquarters identifies anticipated available positions for the upcoming assignment year (i.e., the following calendar year). Officials then solicit input from Coast Guard field units on personnel qualification requirements and unit readiness.[17] Headquarters officials subsequently incorporate this information into a published list of available assignments that will begin the next calendar year, which service members can review and apply for via ranked preference. Headquarters officials then make assignment decisions and generate transfer orders assigning the member to a new duty station.[18] Tour lengths for assignments typically vary from one to four years depending on the type of assignment (e.g., continental U.S., overseas, afloat, etc.), and may be extended or shortened based on service need or member preference.

During the second phase, service members coordinate their travel and personal property shipments and then conduct their move.[19] Headquarters officials typically issue transfer orders at least 90 days before the member’s reporting date to units within the continental U.S. and 120 days before the member’s reporting date to units outside the continental U.S. During this time, Coast Guard service members must decide whether to use a government-contracted move provided through DOD or independently schedule a property move with a commercial moving company (personally procured move). In addition, members may choose to independently move a portion of their household goods themselves.

Rotation Schedule. According to officials, the Coast Guard primarily rotates its active-duty workforce between May 15 and August 31, known as peak moving season. However, the Coast Guard may selectively assign personnel to duty stations outside the routine assignment process because of position changes and unplanned or unexpected vacancies throughout the year. In contrast with the Coast Guard’s practice, DOD service branches rotate most of their personnel year-round, according to officials.[20] The Coast Guard changed its rotation policy in the mid-1990s to the current practice to minimize disruptions for service members’ families during the school year and improve retention, according to Coast Guard officials. In addition, officials noted that the change to a summer rotation season led to more predictability in the timing of transfers for service members and their families.

Transportation Offices. At Coast Guard and DOD military installations, over 250 personal property processing and shipping offices (transportation offices) support service member rotations and the movement of personal property. The military services own, operate, and staff the transportation offices. The Coast Guard operates 23 transportation offices distributed across its unit locations. In cases where a local Coast Guard transportation office is not available, Coast Guard service members may work with representatives on DOD military installations performing similar functions, according to officials.

The personal property processing offices are tasked with ensuring that the service member’s transfer orders and move authorization paperwork are correct, and that their application is accurate and complete, among other things. The processing offices also provide counseling to service members on the move process, including the option to use a personally procured move or government-contracted move, as well as available entitlements and allowances.

The personal property shipping offices are to coordinate with transportation service providers (i.e., commercial moving companies) to schedule government-contracted moves, monitor provider performance, and take or recommend administrative action against poor performing providers. Four of the Coast Guard transportation offices have shipping offices (Miami, Florida; Alameda, California; and Ketchikan and Kodiak, Alaska).

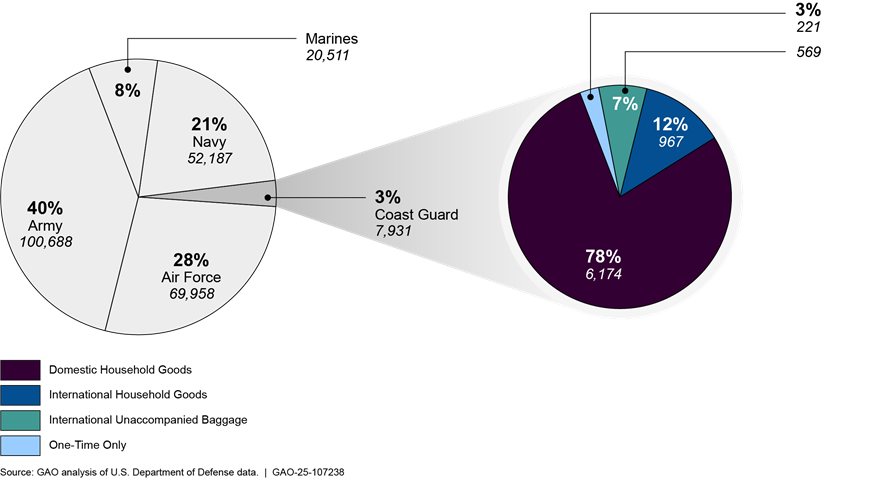

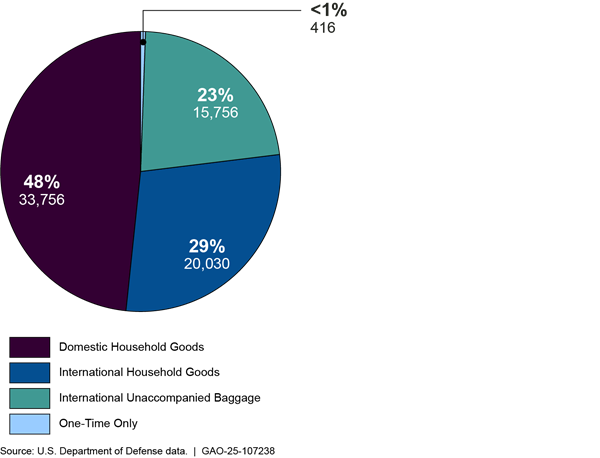

The Defense Personal Property Program

The Defense Personal Property Program, managed by U.S. Transportation Command (TRANSCOM) within DOD, is responsible for administering government-contracted household goods and privately owned vehicles shipping and storage programs for military services, including Coast Guard service members, DOD civilians, and their families.[21] The military services reimburse TRANSCOM for program and operating costs based on the proportion of their shipments administered through the program, according to TRANSCOM officials. In fiscal year 2023, the program arranged for the delivery of about 251,000 domestic and international household goods, unaccompanied baggage, and one-time-only shipments.[22] This included about 7,900 household goods shipments (3 percent of the total number of shipments) for Coast Guard service members (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Household Goods Shipments Delivered Through the Defense Personal Property Program in Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Data current as of August 13, 2024 and does not include shipments picked up prior to fiscal year 2023.

See appendix II for the breakdown of household goods shipments delivered through the Defense Personal Property Program for DOD military services in fiscal year 2023.

Once a service member receives their transfer orders, they contact their local personal property processing office to receive counseling on their allowances and entitlements. Service members, with guidance from these processing offices then enter their transfer and move information into the Defense Personal Property System.[23]

|

Transportation Service Providers About 850 transportation service providers currently participate in the Defense Personal Property Program. Providers operate through different combinations of “channels,” or combinations of origin and destination locations, within and outside the continental U.S. The number of available providers within a given channel varies based on how many have an acceptable Best Value Score—a scoring system DOD established that uses metrics such as customer satisfaction, on-time pickup and delivery, and other factors to assign providers an aggregate performance rating. The Best Value Score is the key factor in the booking and selection of a moving company to move service member personal property, thereby incentivizing good performance, according to TRANSCOM officials and program documents.

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Defense information (text); New Africa/stock.adobe.com (image) | GAO‑25‑107238 |

If a service member elects to use a government-contracted move, the system electronically offers the shipment to one of the DOD-approved transportation service providers (see sidebar) available to ship and store the service member’s personal property. After a transportation service provider accepts the shipment, it will contact the service member to conduct a pre-move survey to establish the volume of household goods to be transported, identify special packing requirements, and confirm packing and pickup dates.[24] Transportation service providers then conduct the shipment and coordinate directly with the service member for delivery or storage of their household goods.

Coast Guard and DOD Policies and Guidance Support Duty Station Rotations

Coast Guard Implements Policies for Assignment Administration

The Coast Guard implements policies and procedures concerning assignment administration for duty station rotations through its Military Assignments and Authorized Absences guidance (assignment manual). According to the manual, the Coast Guard aims to supply qualified, versatile personnel who can effectively perform Coast Guard duties and missions. The manual states that the needs of the service are the highest priority, but that the service aims to distribute assignments to preferred and less desirable duty stations more equitably throughout its personnel structure. As such, the manual includes policies to consider members’ prior service history and special circumstances during the assignment process, as well as establish programs to support service members at their new assignment locations.

Geographic Stability. Coast Guard policies allow for extensions and consecutive tour of duty assignments in a local or geographic region to minimize rotation costs and family disruptions. However, this does not mean that members may fill the same position for two consecutive tours. Rather, successive assignments may be located within the same geographic region. For example, about 30 to 33 percent of assignments are no cost orders, where the service member’s new assignment is within 50 miles of their existing assignment, according to Coast Guard officials. Officials noted that service members stationed at the Coast Guard area commands in Base Portsmouth, Virginia and Base Alameda, California, are likely to have opportunities for subsequent assignments in the same geographic area.

Assignment Priority. Coast Guard policies also allow enlisted members who have completed full tours in arduous or hard-to-fill duty station assignments to receive preference for their next assignment.[25] Many times these positions are assigned aboard Coast Guard ships or outside the continental U.S, and arduous duty stations assignments are rated on a scale from one to six. Enlisted members who complete assignments with an assignment priority rating of one or two are most likely to receive their first choice of location for their next assignment. For example, officials noted that a service member completing a one-year assignment for unaccompanied personnel on a cutter stationed in the Persian Gulf would receive a priority one rating and would therefore likely get their first choice for their next assignment location.

Special Circumstances. In addition to policies intended to account for a members’ past duty station assignment, the Coast Guard assignment manual also includes policies to support service member’s special circumstances. For example, when assigning married service member couples, assignment officers should coordinate tour lengths to support duty station co-location.[26] Similarly, the Coast Guard is to account for availability of medical services at a duty station in cases where members’ dependents have special needs, such as chronic medical conditions, mental health conditions, or physical disabilities. In cases where a dependent has a condition that requires significant medical attention, the Coast Guard typically restricts member assignments to geographic locations with access to a major medical area within 25 miles or a 30-minute drive.[27]

Sponsor Program. The assignment manual states that Coast Guard field units should support incoming service members by assigning them sponsors who can provide information about the community and provide general assistance. This includes information on housing availability, temporary lodging, and communal resources on bases (e.g., commissary); information to facilitate job-seeking spousal employment; and other information.

DOD Issues Guidance for Member Travel and Personal Property Shipments

DOD is the issuing authority for regulations concerning member travel and personal property shipments for service members during rotations. Specifically, DOD maintains and applies Joint Travel Regulations and Defense Transportation Regulations. These regulations apply to all uniformed service members and their dependents, including the Coast Guard.

Joint Travel Regulations. The Joint Travel Regulations cover policies and laws establishing travel and transportation allowances of uniformed service members and DOD civilian travelers.[28] These include rules for traveling locally, shipping belongings, and qualifying for standard travel and transportation allowances–transportation, per diem, and temporary lodging–and miscellaneous reimbursable expenses.[29] In addition, the Joint Travel Regulations describe the total amount and types of household goods members are allowed to move under their transfer orders, generally referred to as entitlements. For example, a member’s weight allowance refers to the total combined weight of any household goods shipped, plus any unaccompanied baggage shipped and any household goods in storage, that a service member is entitled to move. The total authorized weight allowance is typically determined by a service member’s pay grade and whether they have dependents. The Joint Travel Regulations also establish policies for reimbursements to service members for personally procured moves.[30]

Defense Transportation Regulations. The Defense Transportation Regulations, managed by TRANSCOM, describe procedures and assign responsibilities related to personal property shipments under the program. For example, transportation service providers participating in the Defense Personal Property Program are fully responsible for the shipment and storage of service members’ household goods, including all loss and damage, claims, or other violations.[31] Under these regulations, TRANSCOM is responsible for overseeing transportation service provider performance and conducting quality assurance activities, including taking action for unethical behavior or violations of contract terms.[32] To become a transportation service provider, moving companies must also follow guidelines under DOD rules for military freight traffic.[33]

In addition to the regulations, DOD maintains a public-facing website (MilitaryOneSource.mil) for military service members and their families to plan the full spectrum of their moves, among other things.[34] The site provides (1) general and detailed information on required steps for government-contracted movement of personal property; (2) links to submit move requests; (3) contact information for transportation offices; and (4) other assistance tailored for each military service branch. Service members, including those from the Coast Guard, can use the website to access the Defense Personal Property System to schedule their personal property move, track their shipment, and file damage claims.

Coast Guard Inflation-Adjusted Rotation Costs Generally Declined from Fiscal Years 2019 through 2023, but DOD Program Costs Increased with a Major Program Reform Effort

Coast Guard Duty Station Inflation-Adjusted Rotation Costs Generally Declined from Fiscal Years 2019 through 2023

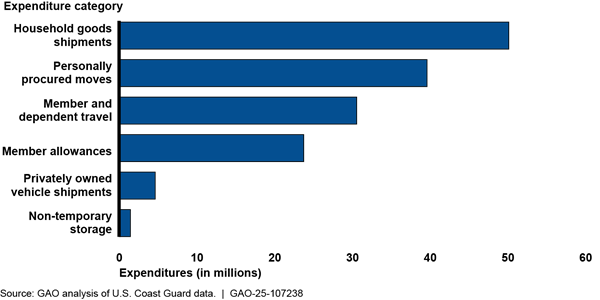

The Coast Guard is responsible for all expenditures related to the shipment and storage of personal property for service members rotating to new assignment locations. Coast Guard reported expenditures for duty station rotations averaged about $174 million per fiscal year between fiscal years 2019 through 2023 (adjusted for inflation), according to our analysis of Coast Guard data (see table 1). This includes expenditures for government-contracted shipments and storage of household goods and privately owned vehicles coordinated by the Defense Personal Property Program, service member and dependent travel, personally procured moves, and various allowances for service members.[35] During this period, the Coast Guard reimbursed service members for, on average, about 5,800 personally procured moves annually.

Table 1: Total Coast Guard Duty Station Rotation Reported Expenditures from Fiscal Years 2019 through 2023

|

Fiscal Year |

Total Expenditures (nominal $) |

Total Expenditures (inflation adjusted $)a |

|

2019 |

150,878,117 |

179,307,592 |

|

2020 |

159,206,650 |

186,494,513 |

|

2021 |

156,179,037 |

177,112,470 |

|

2022 |

167,178,316 |

175,666,129 |

|

2023 |

149,935,167 |

149,935,167 |

Source: GAO analysis of Coast Guard data. | GAO‑25‑107238

aExpenditures are adjusted for inflation and presented in fiscal year 2023 dollars.

Reported rotation expenditures in nominal dollars generally increased after 2019, but returned to the 2019 level in 2023. However, when adjusted for inflation, the expenditures increased in fiscal year 2020 and then declined between fiscal years 2021 and 2023. Coast Guard officials attributed this decline to a net loss in the number of its active-duty members resulting from recruitment and retention issues. Officials noted similar trends in membership and reported rotation expenditures for other military services. In fiscal year 2023, household goods shipments and personally procured moves were the largest proportion of reported Coast Guard rotation expenditures (fig. 3).

DOD Costs for the Defense Personal Property Program Increased Significantly between Fiscal Years 2022 to 2023 with a Major Program Reform Effort

Total reported expenditures for the Defense Personal Property Program increased by 80 percent from $56 million in fiscal year 2022 to $100 million in fiscal year 2023 (adjusted for inflation), according to our analysis of TRANSCOM data (see table 2).[36] TRANSCOM officials attributed this increase to the costs of the Global Household Goods Contract. Specifically, in November 2021, TRANSCOM awarded a new contract (the Global Household Goods Contract) to oversee activities related to the worldwide movement and storage-in-transit of household goods for military service members. This contract was awarded as part of a major program reform effort in response to reported dissatisfaction with DOD’s relocation program. In fiscal year 2023, reported expenditures for the Global Household Goods Contract implementation totaled about $48 million. The reform effort includes replacing a legacy technical system (the Defense Personal Property System) with two new information technology architectures designed to modernize and streamline shipment of personal property, among other things.[37]

Table 2: Total Household Goods Shipments and Reported Defense Personal Property Program Expenditures from Fiscal Years 2019 Through 2023

|

Fiscal Year |

Number of Shipments |

Nominal Global Household Goods Contract Expenditures (in millions) |

Nominal Total Program Expenditures (in millions)a |

Inflation Adjusted Total Expenditures (in millions) |

|

2019 |

393,941 |

$0 |

$33.8 |

$40.2 |

|

2020 |

336,045 |

$0.5 |

$44.1 |

$51.9 |

|

2021 |

326,869 |

$0 |

$44.1 |

$49.6 |

|

2022 |

308,543 |

$6.0 |

$53.9 |

$56.1 |

|

2023 |

327,548 |

$48.0 |

$100.9 |

$100.9 |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Defense reported expenditure data. | GAO‑25‑107238

Note: Household goods are items associated with the home and personal effects belonging to a service member and dependents on the effective date of the order or transfer. The number of shipments column includes all instances in which a requirement for shipping was created in the Defense Personal Property System, regardless of whether the shipment was picked up or delivered.

aDefense Personal Property Program expenditures include administrative (i.e., program office), depreciation, and Global Household Goods contract transition costs, but do not include personal property shipment or storage costs, according to TRANSCOM officials.

The total number of household goods shipments administered through the Defense Personal Property Program declined by 22 percent from fiscal year 2019 through 2022, then increased by about 6 percent from fiscal year 2022 to fiscal year 2023.[38] TRANSCOM officials attributed the decline in shipments to reduced travel resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as individual military department decisions on force structure and assignments, and budget cycles. Officials noted that increases in shipments since then likely indicate resumption of historic shipment rates. TRANSCOM uses the shipment data to bill the military services, including the Coast Guard, for reimbursements for program and operating costs based on the proportion of total shipments for each service, according to officials.

The Coast Guard’s reported inflation-adjusted reimbursement amounts averaged about $1.2 million from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2022, and more than doubled in fiscal year 2023 to about $3 million (see table 3). Coast Guard shipments averaged about 3 percent of total shipments from fiscal years 2019 through 2023. However, the number of Coast Guard shipments administered through the program declined by about 10 percent from fiscal year 2019 through 2023. Coast Guard officials attributed the decline to a combination of factors, including: the lack of moving capacity and staff within all major moving carriers; more Coast Guard members choosing to use personally procured moves versus government-contracted moves; and TRANSCOM’s higher reimbursement rates for personally procured moves that began in fiscal year 2022.

Table 3: Total Coast Guard Household Goods Shipments and Reported Reimbursements to Defense Personal Property Program from Fiscal Years 2019 through 2023

|

Fiscal Year |

Number of Coast Guard Shipments |

Nominal Coast Guard Reimbursement (in millions) |

Inflation Adjusted Coast Guard Reimbursement (in millions) |

|

2019 |

10,752 |

$0.9 |

$1.1 |

|

2020 |

10,249 |

$1.3 |

$1.6 |

|

2021 |

9,911 |

$0.9 |

$1.0 |

|

2022 |

9,334 |

$1.2 |

$1.2 |

|

2023 |

9,724 |

$3.0 |

$3.0 |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Department of Defense data. | GAO‑25‑107238

Note: The number of Coast Guard shipments column includes all instances in which a requirement for shipping was created in the Defense Personal Property System, regardless of whether the shipment was picked up or delivered.

DOD Conducts Customer Satisfaction Surveys, but Does Not Analyze Them for Potential Non-Response Bias

DOD Collects Customer Satisfaction Surveys to Monitor Program Performance

TRANSCOM collects customer satisfaction responses to monitor transportation provider performance in the Defense Personal Property Program. Specifically, TRANSCOM’s survey contractor issues up to five separate surveys to service members at different stages of their personal property moves.[39] Members receive each survey via e-mail or text message within 12 hours of completing the relevant stage of the move, such as pick up of their household goods. The survey contractor also contacts non-respondents at five scheduled follow-up dates for up to 120 days from the initial notification, according to TRANSCOM officials. Finally, officials noted TRANSCOM provides a fact sheet on MilitaryOneSource.mil that explains the importance of the surveys and conducts outreach about the surveys via social media, a military spouse advisor network, and governance meetings.

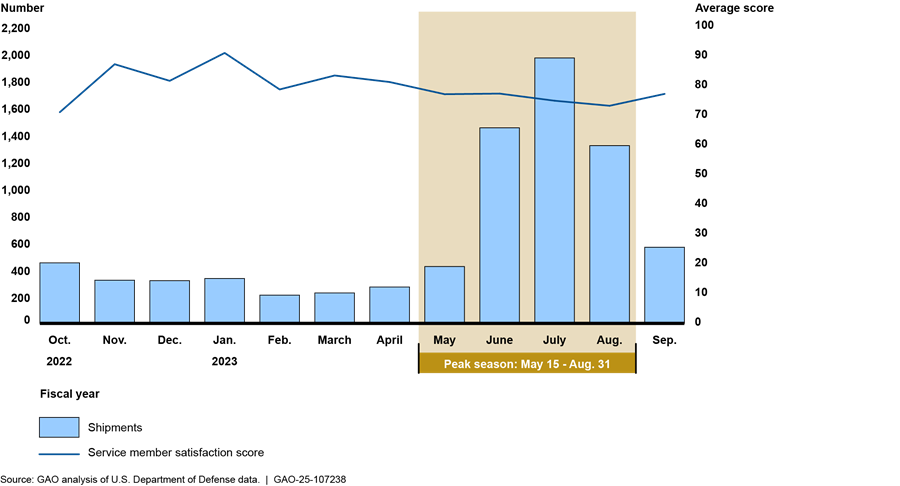

TRANSCOM uses service member responses to calculate an aggregate customer satisfaction survey score, which is a component of a provider’s Best Value Score.[40] Under the Defense Transportation Regulations, TRANSCOM uses the Best Value Score to award shipments to individual providers on a shipment-by-shipment basis. In addition, TRANSCOM uses customer satisfaction data to communicate member experiences to senior leaders from the military services and DOD during regularly scheduled program review and senior leadership meetings.[41] These meetings give the services the opportunity to raise issues or challenges reported by their members, as well as remain informed about their members’ satisfaction with moves conducted under the program. As figure 4 shows, Coast Guard customer satisfaction scores for household good shipments averaged around 76 percent in fiscal year 2023, with a decline occurring during much of the peak moving season.[42]

Figure 4: Coast Guard Household Goods Shipments Compared with Average Coast Guard Service Member Survey Satisfaction Scores for Fiscal Year 2023

DOD Does Not Analyze Survey Responses for Potential Bias Resulting from Low Response Rates

Although TRANSCOM has processes in place to survey the entire eligible population of customers and use satisfaction data it obtains, most service members across all military services typically do not provide survey responses. Low survey response rates are of concern because they raise the risk that the responses received do not represent the views of all service members. This may be due to non-response bias, meaning that the survey results differ from people who respond versus people who do not. For example, in calendar year 2023, TRANSCOM officials reported that about 29 percent of all service members that received a survey responded on average, with variation by month and type of survey. For the Coast Guard, the average response rate declined from 36 percent in 2019 to 16 percent in 2022, and response rates from July 2022 through June 2023 varied across service member ranks from about 10 percent to 40 percent. These differences suggest that the likelihood of response varies across different types of customers (e.g., enlisted vs. officer).

TRANSCOM’s current process takes several steps to ensure accurate and reliable survey results, according to officials. Under the Defense Transportation Regulations, TRANSCOM applies controls to ensure that enough surveys are completed before using the surveys to calculate each transportation service provider’s Best Value Score.[43] TRANSCOM officials said that they also coordinated with service headquarters, the Army Audit Agency, and moving industry associations to define the necessary minimum number of surveys to generate valid results.[44] Finally, officials also cited Defense Transportation Regulations that state that the current surveys have a lower risk of non-response bias than other methods as the survey seeks to provide relative rankings of transportation service provider performance.[45]

However, we found that these efforts were not sufficient to address the risk of non-response bias in the survey data. Specifically, TRANSCOM officials do not fully analyze the customer satisfaction survey data to identify potential non-response bias or identify whether adjustments of estimates are needed.[46] For example, a service member’s likelihood of response could be correlated with the transportation service provider, its performance, or other associated factors, such as a member’s rank, tenure, demographics, and geographic location. In addition, like other population estimates, transportation service provider ranks are also susceptible to bias from missing data.[47]

Finally, previous studies on the potential for non-response bias sponsored by DOD between 2006 and 2011 focused on minimum sample sizes as a remedy for potential sources of error. However, those evaluations did not conduct the type of analysis and adjustment typically used for surveys with low response rates, which could identify factors affecting response rates in general. Further, reaching the minimum requirement for a survey does not ensure that the survey results are unbiased.[48] Instead, it is important to know the probabilities of response for all respondents and, if that is not known, then sufficient adjustments for a low response are typically necessary to ensure the estimates are unbiased.[49]

TRANSCOM officials said they do not analyze the survey responses for non-response bias because they are satisfied that the current survey process effectively captures customer input. However, officials told us they are open to improving the process to ensure quality results. One way to analyze the risk of non-response bias is to compare the characteristics of those members who responded (e.g., service branch, rank, demographics, or geographic location) to the characteristics of the overall population of the survey. This comparison can help identify whether certain groups are underrepresented from the results. Once identified, additional steps can be taken to correct the bias, such as targeting underrepresented groups with additional follow up or giving more statistical weight to their responses during analysis.

GAO’s key practices for evidence-based policymaking state that an organization should assess the quality of the evidence it uses for decision-making, which includes assessing the completeness of the data.[50] In addition, federal standards for statistical surveys set by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget call for agencies to analyze non-response bias for any survey with a response rate of less than 80 percent.[51] The standards suggest that agencies consider comparing respondents to external sources of data, or compare the characteristics of respondents and non-respondents and adjust their reporting of survey estimates if the non-response analysis shows a potential bias.[52]

Non-response bias could cause estimated customer satisfaction scores to be higher or lower than they would have been if the population of customers had responded. This error would, in turn, affect transportation service provider performance scores, rankings, and prioritization for future shipments. In addition, TRANSCOM and the military services may not have accurate information on service member satisfaction with government-contracted moves through the Defense Personal Property Program for decision-making. By conducting analysis for potential non-response bias and making adjustments as necessary, TRANSCOM will have greater assurance that the information it is using represents the views of the target population of service members. Doing so can also help TRANSCOM monitor the transportation service provider performance under the Defense Personal Property Program. It could also provide more reliable information on service member experiences to representatives of the military services, including the Coast Guard.

Coast Guard Officials Identified Challenges Related to Duty Station Rotations, but the Coast Guard Does Not Collect Service-Wide Feedback

Coast Guard field unit officials we interviewed identified key challenges for duty station rotations, particularly for service members rotating to duty stations in remote, rural, and high vacation rental areas. These challenges may negatively affect Coast Guard operations, personnel readiness, and retention, according to officials. However, the Coast Guard does not have a process for routinely collecting service-wide feedback about duty station rotations.

Coast Guard Field Unit Officials Identified Challenges Related to Duty Station Rotations

Field unit officials we interviewed from the nine Coast Guard districts identified five key challenges related to duty station rotations, particularly for service members rotating to duty stations in remote, rural, and high vacation rental areas (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Duty Station Rotation Challenges and Potential Negative Impacts Identified by Coast Guard Field Units

Limited availability and affordability of housing. Officials from all nine Coast Guard districts said that limited availability and affordability of housing, particularly in remote and high vacation areas, are challenges routinely experienced by service members. The Coast Guard relies on the private sector as the primary source of housing for its service members. In such cases, the Coast Guard compensates service members entitled to a housing allowance with a Basic Allowance for Housing.[53] However, some officials noted that the Basic Allowance for Housing was not sufficient to cover the cost of non-military owned housing in expensive areas.[54]

Limited transportation service provider availability. Officials from seven of nine districts noted that limited transportation service provider availability to conduct personal property shipments can be a challenge for Coast Guard service members. For example, if a transportation service provider is unavailable, officials from one district noted that the service member may need to either delay the reporting date or utilize a personally procured move. However, officials from five districts stated that personally procured moves are often also challenging for service members. Officials noted that service members must independently research, hire, and schedule shipments with commercial providers and pay the upfront costs for a personally procured move.[55] This may result in additional stress and higher out of pocket costs for service members, according to officials.

Condensed timing of annual rotation period. Officials from five of nine districts said that the condensed timing of the annual rotation period (May 15 through August 31) compounds other challenges due to transportation service provider availability, which limits moving flexibilities. For example, officials noted that Coast Guard service members compete for shipping dates with DOD service members, and providers may be more inclined to accept DOD service member requests in some locations.[56] In addition, officials from five districts stated that short notice transfer orders or delays in receiving issued orders may cause additional stress for members when planning their moves.[57]

Limited access to communal support services. Officials from five of nine districts said that Coast Guard service members and dependents experience challenges accessing communal support services in their geographic areas of responsibility, such as childcare and medical facilities. Coast Guard members may rotate to units in remote and rural areas far away from DOD and Coast Guard installations with their own communal support services, according to officials. Officials told us that, as a result, service members in those areas may have limited access to civilian childcare and medical services, since they are not otherwise easily accessible or available in the local communities in which they are assigned.[58]

Damaged property and cumbersome claims process. Officials from four of nine districts noted that property damaged during shipments, and filing reimbursement claims for that damage, are challenges service members can experience during rotations. Service members may file a claim against a transportation service provider for damaged or lost household goods during a move. However, district officials noted that the claims process may be difficult and cumbersome for service members. For example, officials from one district noted that providers may argue that property with wear and tear that is damaged during the shipment is not their responsibility, citing plausible deniability because the item was not brand new. Coast Guard service member satisfaction rates with the claims process have been consistently low over time, averaging about 41 percent in calendar year 2023, according to TRANSCOM officials.

Coast Guard Field Unit Officials Identified Potential Negative Effects on Operations, Personnel Readiness, and Retention Due to Rotation Challenges

Rotation challenges may negatively affect Coast Guard operations, personnel readiness, and service member retention, according to Coast Guard field unit officials we interviewed.

Operational impact. Officials from six of nine districts said that challenges with rotations may negatively affect operations and mission capability. For example, officials noted that the summer rotation season coincides with heightened levels of mission-related activities, such as search and rescue and disaster response activities, in some areas. Delays in arrivals of newly assigned members may also reduce operational capabilities and readiness, according to officials. In addition, officials noted that such delays can lead to other service members stationed at these units taking on higher workloads during the rotation season to offset the gap of not having someone else in place. Officials from five of these six districts told us they may reassign members from other units or request reservists to fill operational gaps, particularly during peak moving season.

Personnel readiness. Officials from four of nine districts noted that service members rotating to duty stations in their areas of responsibility may not be fully mission capable when they arrive.[59] For example, officials noted that service members must balance competing demands during rotations, including managing shipments of their personal property, finding available housing, and finding schools and medical facilities for dependents—all while conducting their job duties. Officials told us that newly assigned members at times may not be able to fully participate in mission-related duties before taking care of personal needs. For example, officials from one district we spoke with do not consider personnel to be mission-ready until they are permanently housed. In addition, officials noted that some members may need to undergo additional training for their new assignment. However, officials from two districts said that with the limited timeframe for rotations, members may not receive requisite training before arriving to their new assignments and may not be fully mission capable.

Retention. Officials from six of nine districts said that duty station rotations are often disruptive for service members and that challenges experienced at certain locations may negatively affect retention. For example, Coast Guard officials from four districts noted that fewer members prefer assignments in remote areas than other locations in which the Coast Guard operates.[60] Officials cited various factors for why this may occur, such as limited access to large metropolitan areas, logistical challenges moving to those locations, or lack of available communal support services. Although the Coast Guard may order members to be stationed in these areas based on service need, this may have a negative effect on service member satisfaction and retention.

Coast Guard Has Taken Some Actions to Address Duty Station Rotation Challenges

Coast Guard officials told us they have taken some actions to mitigate or otherwise address challenges experienced by service members when they rotate to new duty stations. Officials said that staff at transportation offices on bases work directly with members on rotation-related issues. This includes pre-move counseling, as well as coordinating with service members and their receiving units to schedule moving dates based on transportation service provider availability. In addition, transportation offices may assist members with navigating the claims process for damaged or lost goods. However, field unit officials from one district noted that staffing shortages on bases and the high volume of rotations during the peak summer months may limit the ability of transportation offices to meet service members’ support needs.

In addition, Coast Guard field unit housing officials serve as the primary points of contact for service members and their families once they are assigned to a base or station. Housing officers communicate with service members regarding their housing needs and try to assist with researching available places to rent. The Coast Guard has some mechanisms to address challenges with affordability and availability of housing in select locations, such as using leased housing and having certain localities classified as critical housing areas, according to officials.[61] The Coast Guard may also request approval from DOD to extend temporary lodging expense allowances based on critical housing shortages. However, field unit officials from one district noted that certain areas may not be approved for temporary lodging extensions, as they do not meet DOD criteria.[62]

At the headquarters level, officials told us the Coast Guard established the Permanent Change of Station Assist Team in 2020 to address personal property shipping challenges experienced by service members during the COVID-19 pandemic. The team has a hotline for service members to call with challenges in the move process, both for government-contracted moves and for personally procured moves. For example, team staff can contact transportation service providers on behalf of a service member to address scheduling or logistical issues with a move.

However, headquarters officials told us that the Permanent Change of Station Assist Team is not a permanent program and noted declining service member usage of the team. Further, some field unit officials noted limitations on the extent the team can directly address service member needs, stating that base officials can provide a similar level of support. According to officials as of June 2024, the Coast Guard will review the number of calls and the provided support to make a final decision on the program at the end of the 2024 rotation season.

Regarding support for dependents, we previously reported on actions the Coast Guard has taken to increase access to childcare for Coast Guard service members. These include plans to build more child development centers, centralizing online information to help families find childcare in their communities, and increasing the subsidy amounts to improve affordability.[63] In addition, we have previously reported that the Coast Guard has developed several telehealth resources to facilitate access to care for service members. However, officials noted some limitations and technical challenges. The Coast Guard can also authorize travel for personnel and some dependents to receive necessary care that is not available locally.[64]

Regarding retention, the Coast Guard previously sponsored assessments of service-wide retention issues that included questions related to duty station rotations.[65] These included a 2019 RAND women’s retention study and an employee retention survey in spring 2023. Service members that participated in the women’s retention study reported various challenges related to work environments, career issues, and personal life concerns. For example, participants noted some challenges with rotations, namely receiving assignments to undesired locations or without other women, as well as spousal employment issues and limited access to childcare.[66]

Separately, in its 2023 employee retention survey, the Coast Guard found that over 50 percent of respondents cited the desire for more geographic stability for themselves and their families as one of their top five factors for wanting to leave the Coast Guard.[67]

In addition, the Coast Guard has various incentive programs to manage the effects of rotations on the workforce and encourage service members to volunteer for difficult-to-fill assignments, according to officials. For example, the Coast Guard’s Military Workforce Planning Team annually determines monetary and non-monetary assignment incentives to help recruit and retain members with critical skill sets. Further, officials noted that the Coast Guard established specialty pay for remote and austere conditions at two locations near Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts in March 2022.[68]

Finally, the Coast Guard developed its “advance-to-position” program, which enables qualified enlisted members to earn advancement (i.e., promotions) through accepting orders to difficult-to-fill assignments. Officials told us that this allows service members to make decisions regarding their own assignments and may result in fewer members leaving the service. However, field unit officials from one district told us that this program may lead to more junior staff placed in positions that may require more experience. Further, officials said they are collecting data to better understand the effect of this program on their operations and mission performance. Headquarters officials noted that the program is still in preliminary testing and has only been in effect for one assignment year.

Coast Guard Does Not Have a Process to Routinely Collect Service-Wide Feedback on Duty Station Rotations from All Service Members

The Coast Guard has mechanisms that may collect information on duty station rotation challenges experienced by some, but not all, service members. For example, field unit officials from six of nine districts told us that they occasionally report service members’ experiences and challenges with rotations to relevant headquarters offices. Coast Guard headquarters officials told us that in addition to challenges reported by field units, members can communicate feedback on rotations when they meet with assignment officers. Further, Coast Guard headquarters officials noted that they receive high-level summary information on service member satisfaction with personal property shipments conducted through the Defense Personal Property Program.

Standards for Internal Control calls for management to use and communicate quality information, including obtaining relevant data from internal and external sources and processing it into information that stakeholders can use to make informed decisions and evaluate the entity’s performance in achieving key objectives and addressing risks.[69] Although Coast Guard officials collect some information on individual service member rotation experiences, we found that the Coast Guard does not have a process to routinely collect and use service-wide feedback on duty station rotations. Headquarters officials said they believe they have appropriate information to remain informed of individual service member experiences with rotations and use it when making assignment decisions. However, they acknowledged that they do not have a process for collecting and analyzing service-wide feedback on rotation-related challenges. Further, the Coast Guard Permanent Change of Station Assist Team does not collect information on rotation challenges experienced by members, according to officials. Finally, summary information on shipment satisfaction provided by TRANSCOM does not include service member experiences with the Coast Guard assignment process and policies, personally procured moves, or available support programs.

Without a process to routinely collect feedback on rotations, the Coast Guard is limited in its ability to evaluate whether current rotation policies contribute to service-wide challenges. For example, the service does not have complete information to make informed decisions regarding the impact of rotations on operations, personnel readiness, and retention, or the adequacy of current support initiatives in addressing those challenges. Establishing a process to collect and analyze service-wide feedback on a routine basis will provide the Coast Guard with a better understanding of rotation challenges and the impact on operations, personnel readiness, and retention. This understanding can better position the Coast Guard to address challenges with the duty station rotation process, as well as meet service member needs.

Conclusions

The Coast Guard assigns thousands of service members to a range of operating locations every year, including to remote areas, where the members, and often their families, must reside. The Coast Guard and DOD play important roles in supporting Coast Guard service members during rotations, and both agencies have taken some steps toward identifying and addressing related challenges, such as conducting surveys and providing additional support services.

DOD provides the Coast Guard summary information from TRANSCOM on Coast Guard service member satisfaction with personal property shipments conducted through the Defense Personal Property Program. However, TRANSCOM does not analyze the customer satisfaction survey responses to identify potential non-response bias and the effect on the accuracy of those responses. As a result, the Coast Guard may not have accurate information on service member experiences with government-contracted moves through the Defense Personal Property Program for decision-making. By conducting analysis for potential non-response bias in the survey responses, TRANSCOM and the military services will have greater assurance that the information they are using represents the views of the target population of service members who use government-contracted moves conducted through the Defense Personal Property Program.

In addition, the Coast Guard relies on field units to report on service members’ experiences and challenges with rotations, but it does not have a process to collect and analyze service-wide feedback on duty station rotations on a routine basis. By establishing such a process, the Coast Guard would have a better understanding of rotation challenges and the impact on operations, personnel readiness, and retention. This would also better position the Coast Guard to manage its rotation policies and guidance toward meeting service member needs.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations, one to DOD and one to the Coast Guard:

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the TRANSCOM Commander analyzes the potential for non-response bias in the Customer Satisfaction Survey and, as necessary, incorporate accepted statistical methods to adjust for identified sources of bias into operating procedures. (Recommendation 1)

The Commandant of the Coast Guard should establish a process to routinely collect and analyze service-wide feedback on duty station rotations. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DHS and DOD for review and comment. DHS and DOD provided written comments, which are reprinted in appendices IV and V, respectively, as well as technical comments that we incorporated, as appropriate. The Coast Guard, through DHS, concurred with our recommendation that the Coast Guard establish a process to routinely collect and analyze service-wide feedback on duty station rotations.

DOD partially concurred with our recommendation to analyze the potential for non-response bias in the Customer Satisfaction Survey and, as necessary, incorporate accepted statistical methods to adjust for identified sources of bias. In its written comments, DOD stated that TRANSCOM finds no evidence of non-response bias in the Customer Satisfaction Survey. In addition, DOD stated that we did not identify any bias in the survey response rates or explain what statistical methods would be acceptable to adjust for non-response bias. However, as described in the report, low survey response rates raise the risk of non-response bias, in which the survey results differ from people who respond versus people who do not. Although TRANSCOM takes several steps to ensure accurate responses, officials said they do not assess the survey data to identify potential non-response bias that may arise from low survey response rates. By conducting this analysis and adjusting estimates using the statistical methods described in the report, we believe that DOD and the military services, including the Coast Guard, will have greater assurance that the information they are using represents the views of service members.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Commandant of the Coast Guard, the Secretary of Defense, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-8777 or MacleodH@gao.gov. Contact points for our Office of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to the report are listed in appendix VI.

Heather MacLeod

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

Appendix II: Breakdown of Household Goods Shipments for DOD Military Services Conducted Through the Defense Personal Property Program in Fiscal Year 2023

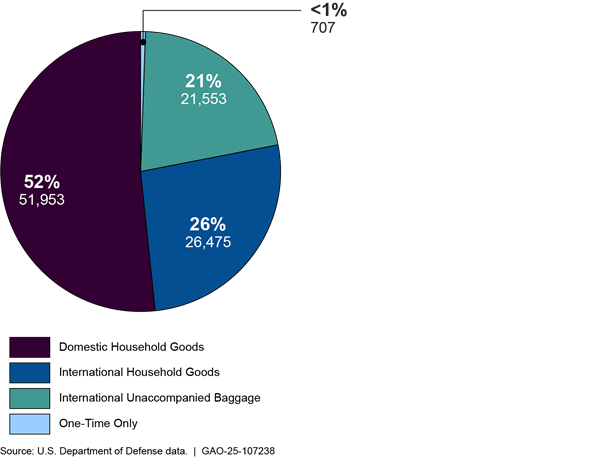

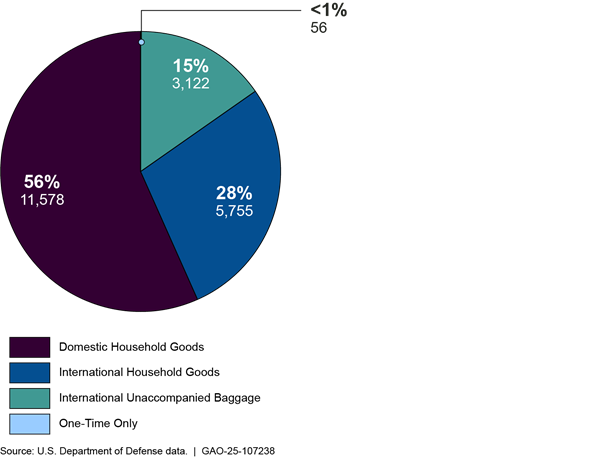

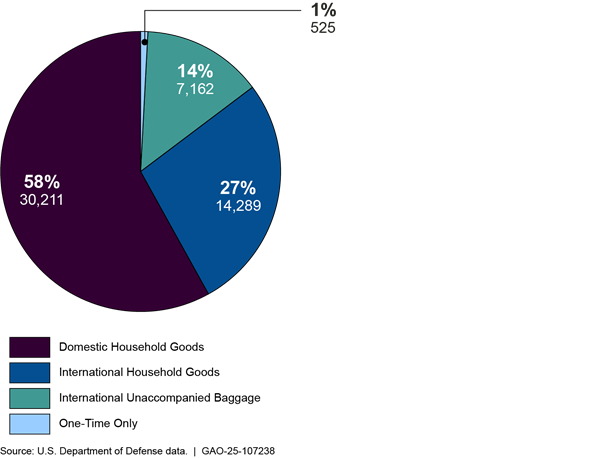

As previously described, in fiscal year 2023, the Defense Personal Property Program arranged for delivery of about 251,000 domestic and international household goods, and unaccompanied baggage. This included about 7,900 shipments (3 percent of the total number of shipments) for Coast Guard service members. The following figures provide a breakdown of the number of household goods shipments delivered for the DOD military services in fiscal year 2023.

Figure 7: Air Force Household Goods Shipments Delivered Through the Defense Personal Property Program in Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Data current as of August 13, 2024.

Figure 8: Army Household Goods Shipments Delivered Through the Defense Personal Property Program in Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Data current as of August 13, 2024.

Figure 9: Marine Corps Household Goods Shipments Delivered Through the Defense Personal Property Program in Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Data current as of August 13, 2024.

Figure 10: Navy Household Goods Shipments Delivered Through the Defense Personal Property Program in Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Data current as of August 13, 2024.

In November 2021, TRANSCOM awarded a new contract (the Global Household Goods Contract) worth over $6 billion across the Future Years Defense Program to a single commercial move manager—HomeSafe Alliance.[70] According to the contract terms, HomeSafe Alliance is to oversee activities related to the worldwide movement and storage-in-transit of household goods for military service members. In a January 2024 report to congressional committees, TRANSCOM cited widespread dissatisfaction with DOD’s relocation program and calls for change from military families and congressional leaders in 2018 as the impetus for program reform efforts, which included awarding the Global Household Goods Contract.

Under the terms of the new contract, transportation service providers can participate in the new program as subcontractors and HomeSafe Alliance will arrange personal property shipments, request payments, and monitor subcontractor performance.[71] Concurrent with the execution of the Global Household Goods Contract, TRANSCOM plans to replace its legacy technical system (the Defense Personal Property System) with two new information technology architectures designed to modernize and streamline shipment of personal property. The first, developed by DOD, will facilitate service member move requests and serve as the initial interface where transportation offices develop their initial move requirements, such as the timing for picking up household goods. The second, developed by HomeSafe Alliance, is a customer-facing system designed to automate functions, such as customer satisfaction surveys and damage claims, and work with the new DOD system.

Domestic implementation of the Global Household Goods Contract was scheduled to begin in September 2023; however, the transition was delayed due to challenges with the creation of the new DOD and HomeSafe Alliance technical systems. TRANSCOM officials said they began phasing in the new information technology systems from March through April 2024 at a limited number of military installations, with plans for full domestic implementation by the end of 2024 and full international implementation by the end of 2025. DOD plans to continue to award personal property moves to individual moving companies on a shipment-by-shipment basis through the 2024 peak season. However, the planned implementation timeframe depends on the results of the initial phase-in, resolution of any interoperability issues, and completion of necessary staff training, according to TRANSCOM officials. As of August 2024, both new information technology systems had been successfully integrated and deployed to support initial shipments under the new contract and were capable of processing household goods moves for DOD service members in the continental U.S., according to officials.

GAO Contact

Heather M. MacLeod, (202) 512-8777 or MacLeodH@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Andrew Curry (Assistant Director), Jason Blake (Analyst-in-Charge), Bethany Cole, Nasreen Badat, Tracey King, John Bornmann, Jeff M. Tessin, and Ben Crossley made key contributions to this report.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]The Coast Guard’s 11 statutory missions outlined in the Homeland Security Act of 2002, as amended, are as follows: marine safety; search and rescue; marine environmental protection; ports, waterways, and coastal security; drug interdiction; migrant interdiction; living marine resources; other law enforcement; aids to navigation; ice operations; and defense readiness. 6 U.S.C. § 468(a).

[2]For the purposes of this report, “personnel” and “service members” are used interchangeably, consistent with Coast Guard terminology in policies and guidance. Active-duty personnel are full-time enlisted and officer personnel responsible for carrying out the Coast Guard’s missions.

[3]GAO, Coast Guard: Better Feedback Collection and Information Could Enhance Housing Program, GAO‑24‑106388 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 5, 2024).

[4]A permanent duty station is a service member’s official station, or a civilian employee or international traveler’s permanent workplace. It may be either on land or aboard a ship. For the purposes of this report, we use the term “duty station” to refer to permanent duty stations.

[5]GAO, Coast Guard: Recruitment and Retention Challenges Persist, GAO‑23‑106750 (Washington, D.C.: May 11, 2023) and GAO‑24‑106388.

[6]S. Rep. No. 118-58, at 149 (118th Cong.).

[7]Coast Guard, Military Assignments and Authorized Absences, Commandant Instruction M1000.8A (Washington, D.C.: June 6, 2019); Coast Guard Pay Manual, Commandant Instruction M7220.29D (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 6, 2019); Coast Guard Supplement to the Joint Travel Regulations, Commandant Instruction M4600.17B (Washington, D.C.: June 28, 2019).

[8]Department of Defense, Joint Travel Regulations for Uniformed Service Members and DOD Civilian Employees (Feb. 1, 2024) and Defense Transportation Regulations, Part IV, (Aug. 1, 2023). According to this guidance, personal property includes household goods, unaccompanied baggage, privately owned vehicles, and mobile homes. Household goods are items associated with the home and personal effects belonging to a service member and dependents on the effective date of the order or transfer.

[9]The Coast Guard Personnel Service Center is responsible for assigning personnel with the appropriate skills to available billets so the service can properly carry out its mission, among other things. The Coast Guard Logistics Command is the parent command for bases providing mission support, which include offices that help coordinate the processing and shipment of service members’ personal property. The Coast Guard Office of Military Personnel Policy develops and maintains policy guidance related to military assignments and pay and ensures the Coast Guard follows Joint Travel Regulations and Defense Transportation Regulations issued by DOD.

[10]The U.S. Transportation Command within DOD administers personal property and personally owned vehicle shipment and storage programs for all uniformed service members (including Coast Guard), as well as develops and maintains guidance related to the movement of those items, among other things.

[11]We adjusted these values for inflation based on the most recent 10-year projections issued by the Congressional Budget Office in 2024.

[12]Our summary statistics for rotation-related costs are based on Coast Guard and DOD’s reported expenditures.

[13]GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: Jul. 12, 2023).

[14]U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Standards and Guidelines for Statistical Surveys, Statistical Policy Directive No. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2006).

[15]In this report, we use the term “field units” to refer to the various types of shore-based units in the Coast Guard’s field organization, including area commands, districts, sectors, and subordinate field units. The Coast Guard’s field structure is divided into two area commands: Atlantic and Pacific. These areas are further divided into nine district commands consisting of sectors and stations within them and are responsible for Coast Guard operations within their geographic areas of responsibility. For a visual depiction of these geographic areas, see appendix I.

[16]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014). Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance that the objectives of an entity will be achieved. We considered the underlying principles that management should obtain relevant data from internal and external sources and process it into information that stakeholders can use to make informed decisions. Federal internal control standards also call for management to evaluate the entity’s performance in achieving key objectives and addressing risks utilizing this data.

[17]Coast Guard individual commands communicate to headquarters about enlisted personnel assignment issues that may affect the operational readiness of field units during the assignment year. The Coast Guard balances personnel concerns against individual service member preferences, professional development goals, and the goal of equitably distributing members to all units.

[18]Headquarters officials assign members based on different factors, including time in present area, assignment history, physical condition, and dependent needs.

[19]Unit staff are responsible for converting transfer orders to travel orders and distributing travel orders.

[20]Although DOD military services rotate their members year-round, about 40 percent of DOD’s annual household goods moves also occur during the annual summer peak moving season.

[21]We previously reported on steps DOD could take to improve the Defense Personal Property Program. Specifically, we recommended that DOD collect and track data more precisely to determine the program’s manpower needs and costs; develop performance metrics for program activities not part of the Global Household Goods contract; and articulate the linkage between performance metrics and program goals. DOD has implemented all recommendations. See GAO, Movement of Household Goods: DOD Should Take Additional Steps to Assess Progress toward Achieving Program Goals, GAO‑20‑295 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 6, 2020).

[22]Unaccompanied baggage are necessary items expeditiously shipped to a duty station location. Unaccompanied baggage may be transported separately from most household goods, and includes personal clothing and effects, cooking and housekeeping items, and items required for the care of dependents, such as baby carriages.

[23]The Defense Personal Property System is a web-based DOD system that supports shipment management, invoicing, and damage claims.

[24]Department of Defense, Defense Transportation Regulation, Part IV Chapter A-402: Shipment Management (Feb. 7, 2024).

[25]Officers are not eligible for assignment priority upon completion of arduous positions, according to Coast Guard officials.

[26]Assignment officers within the Coast Guard Personnel Service Center are responsible for assigning service members to duty stations. Officers oversee discrete portfolios based on specialties, such as aviation billets, mission support, and engineering, and accordingly coordinate the assignment of personnel competing for different jobs, according to Coast Guard officials.

[27]Coast Guard, Special Needs Program, Commandant Instruction 1754.7C (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 9, 2020).