ADMINISTRATIVE BURDEN

OMB Should Update Instructions to Help Agency Assessment Efforts

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Yvonne D. Jones at jonesy@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107239, a report to congressional requesters

OMB Should Update Instructions to Help Agency Assessment Efforts

Why GAO Did This Study

According to an estimate cited by OMB, eligible Americans forgo claiming more than $140 billion in federal benefits each year. They do so, in part, due to administrative burdens—the time and other resources expended to obtain or retain these benefits. Reducing such burdens can help reduce economic insecurity and improve the public’s experiences with federal programs, a longstanding priority of Congress and the executive branch.

GAO was asked to review federal agencies’ efforts to reduce administrative burdens for federal benefit programs. This report examines selected federal agencies’ efforts to (1) implement OMB guidance for reducing administrative burdens, (2) support burden reduction efforts, and (3) integrate burden reduction priorities into their performance management activities.

GAO compared nine federal agencies’ information collection requests to OMB’s burden reduction guidance and documentation instructions for agencies. GAO also compared performance management documentation developed by three selected federal agencies that administer three of the largest federal benefit programs—USDA, SSA, and VA—to relevant OMB guidance. GAO interviewed officials at OMB and the three selected agencies about their burden reduction efforts.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that OMB update its supporting statement instructions to fully incorporate all elements of its burden reduction guidance. OMB did not provide comments.

What GAO Found

Federal information collections include applications and other forms that individuals must complete to obtain federal benefits, such as food assistance, medical care, and cash aid. In April 2022, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued guidance to agencies for documenting administrative burdens that individuals experience in submitting the required information. OMB has directed agencies to document these burdens in the supporting statements for each information collection request provided to OMB for review and approval. These burdens include learning, compliance, and psychological costs.

GAO reviewed supporting statements for 51 of the 8,613 approved information collection requests submitted to OMB between April 2022 and April 2024. These 51 requests met the following criteria:

· The preparing agency was a Chief Financial Officers Act agency.

· The request set requirements that individuals and households must meet to obtain or retain federal benefits.

· The agency estimated the request would impose at least 75,000 burden hours on the public.

OMB’s instructions for preparing these statements do not fully incorporate OMB’s burden reduction guidance. For example, OMB’s instructions do not direct agencies to discuss potential learning or psychological costs as part of their statements. As a result, agencies may not be fully documenting the administrative burdens imposed by benefit program requirements, limiting transparency and potentially missing opportunities to identify and reduce burdens on the public.

As of December 2024, the Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Social Security Administration (SSA) had established offices for improving customer experience. These offices helped to collect data to monitor customer feedback. They also helped to identify solutions for reducing administrative burdens in support of broader efforts to improve customer satisfaction.

USDA, VA, and SSA have also taken steps to integrate burden reduction priorities into strategic goals, strategic objectives, and performance goals associated with some of their largest programs and services.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

CFO Act |

Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 |

|

CX |

customer experience |

|

FNS |

Food and Nutrition Service |

|

EO |

executive order |

|

HISP |

High Impact Service Provider |

|

ICR |

information collection request |

|

OIRA |

Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

PRA |

Paperwork Reduction Act |

|

SSA |

Social Security Administration |

|

SSI |

Supplemental Security Income |

|

USDA |

Department of Agriculture |

|

VA |

Department of Veterans Affairs |

|

VEO |

Veterans Experience Office |

|

VHA |

Veterans Health Administration |

|

WIC |

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 21, 2025

Congressional Requesters

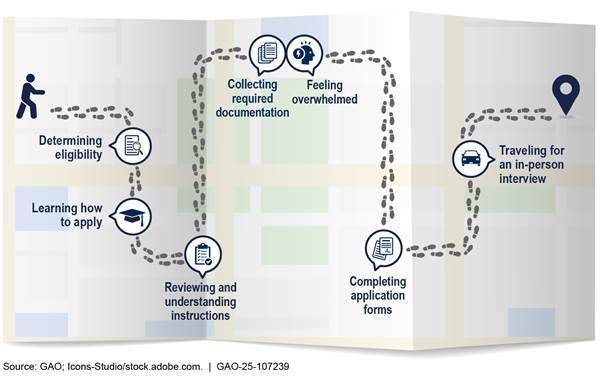

According to a 2023 estimate cited by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), eligible Americans forgo claiming more than $140 billion in federal benefits each year.[1] These benefits include food assistance, medical care, and cash aid. OMB has reported that unclaimed benefits increase material insecurity and make it harder for families to climb out of poverty. These benefits go unclaimed, in part, because individuals attempting to obtain or retain them experience administrative burdens. Such burdens include financial expenses and the “time tax”—the time and effort to learn about and meet program requirements.

OMB reported that the public spent an estimated 10.5 billion hours attempting to complete federal information collections in fiscal year 2023. Applications and other forms for federal benefit programs make up a large proportion of these collections. In April 2022, OMB issued guidance to agencies on how to identify opportunities to reduce burdens experienced by individuals in meeting information collection requirements for benefit programs.[2]

Improving customers’ experiences with federal programs has been a longstanding priority of Congress and the executive branch. The President issued Executive Order (EO) 14058 in December 2021, directing the heads of federal agencies to take a variety of actions to improve public customers’ experiences with federal programs and services.[3] Through EO 14058, the President further directed federal agencies to integrate customer experience (CX) priorities into their performance management activities, among other provisions. Agencies’ efforts to implement EO 14058’s CX directives can help them to establish burden reduction as long-term priorities.

You asked us to review federal agencies’ efforts to reduce administrative burdens for federal benefit programs under EO 14058 and its implementing guidance. This report examines the extent to which (1) federal agencies have implemented OMB’s information collection request (ICR) guidance to reduce administrative burdens associated with federal benefit programs; (2) selected agencies have taken actions to support burden reduction efforts for federal benefit programs; and (3) selected agencies have integrated burden reduction priorities for federal benefit programs into their performance management activities.

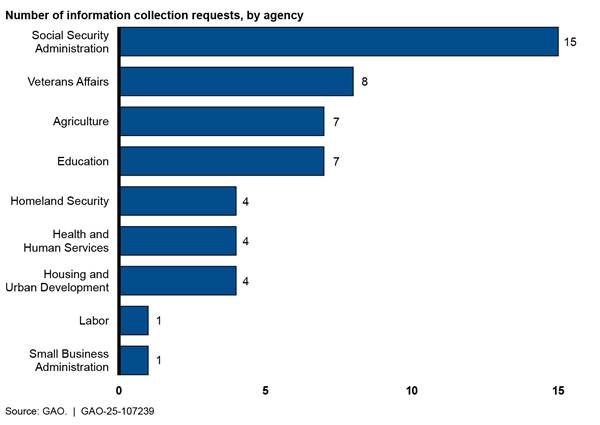

For our first objective, we identified 8,613 approved ICRs submitted to OMB from when it issued its guidance in April 2022 to April 2024. Of these 8,613 ICRs, we focused our review on the 51 ICRs, submitted by nine agencies, which met the following criteria:

· the preparing agency was a Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) agency;

· the ICR set requirements that individuals and households must meet to obtain or retain federal benefits; and

· the preparing agency estimated the ICR would impose at least 75,000 burden hours on the public.[4] We used a 75,000 burden hours threshold for our analysis to focus our review on ICRs that impose higher administrative burdens on the public. ICRs that met this threshold accounted for 99 percent of all burden hours imposed by ICRs related to obtaining or retaining federal benefits.

We reviewed supporting statement documentation for each of the 51 ICRs to assess whether each ICR fully addressed three selected elements of OMB’s M-22-10 burden reduction guidance. These elements summarize the OMB guidance provisions relevant to burden analysis. They address documenting (1) the full range of administrative burdens that individuals may experience in meeting the ICR’s information collection requirements, (2) the extent to which certain groups of individuals may experience higher burdens than others, and (3) external engagement with the public beyond the notice-and-comment process. We also compared OMB’s burden reduction guidance to OMB’s supporting statement instructions to agencies for documenting burden analyses as part of agencies’ ICR submissions.

To understand why agencies may not have fully addressed some elements of OMB’s burden reduction guidance in their ICRs, we interviewed officials from OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) and Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) staff from three selected agencies: the Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Social Security Administration (SSA). We selected these agencies because they administer three of the benefit programs and services with the highest obligations.[5]

For our second and third objectives, we focused our work on the USDA, VA, and SSA benefit programs and services with the highest fiscal year 2022 obligations: USDA nutrition assistance programs administered by the Food and Nutrition Service, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (about $121 billion); VA health care services administered by the Veterans Health Administration (about $109 billion); and SSA’s Supplemental Security Income (about $60 billion) and Social Security Disability Insurance programs (about $142 billion).

For our second objective, we interviewed PRA and CX staff at our selected agencies about their efforts to support initiatives to identify and reduce administrative burdens as of December 2024.[6] We focused on efforts relevant to the prioritized programs and services. We reviewed agency documentation of these efforts, where available.

For our third objective, we reviewed USDA, VA, and SSA performance plans, performance reports, and quarterly agency priority goal reports prepared in fiscal year 2024. We used this documentation to identify performance management activities related to reducing administrative burdens for some of the largest benefit programs and services offered by these agencies, as identified above. These activities included strategic goals, strategic objectives, and performance goals. We then assessed the extent to which documentation for each identified performance management activity incorporated selected elements from OMB’s Circular A-11 guidance. These elements reflect information that agencies should include in their annual reporting on performance management activities.[7] We focused our analysis on the 19 guidance elements that we identified as important to agencies’ efforts to achieve progress toward their missions and to communicate that progress. We interviewed agency officials about potential gaps in agencies’ performance management documentation. We also interviewed officials about their agencies’ efforts to integrate burden reduction priorities into the individual performance plans for senior executives. For more detail on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Process for Developing Federal Information Collections

Federal information collections refer to any instance where a federal agency obtains, solicits, requests, or requires the disclosure of data from the public, including from individuals, businesses, or organizations.[8] Information can be collected using forms, surveys, and recordkeeping and disclosure requirements. Applications and other forms for benefit programs, such as those providing food assistance, medical care, and cash aid, make up a large proportion of federal information collections.

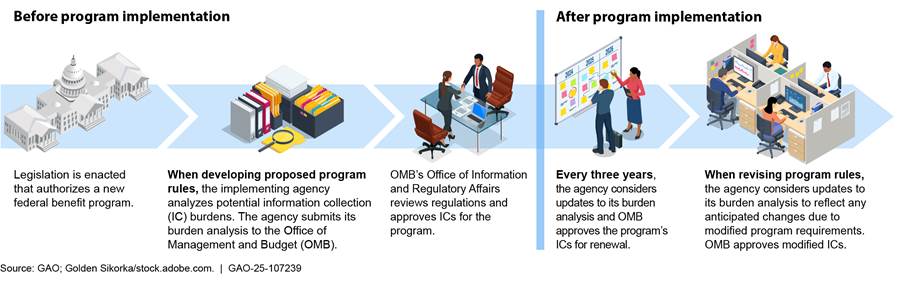

The Paperwork Reduction Act of 1980, as amended, governs how agencies collect information from the public.[9] Under the PRA, when seeking approval for an information collection, an agency generally must provide a 60-day notice in the Federal Register that provides important details about the proposed collection and provides the public with the opportunity to comment.[10] For information collections that are associated with proposed rules, the agency can meet this requirement through its notice of proposed rulemaking. Once the comment period is over, the agency considers any comments received and updates the proposed information collection, as needed. The agency then publishes a second notice in the Federal Register and submits an ICR to OMB for approval.[11] Within OMB, OIRA is responsible for reviewing and approving submitted ICRs. Agencies generally must resubmit existing ICRs that are still necessary to OMB for reapproval every 3 years.[12] These procedures are generally referred to as the standard clearance process.

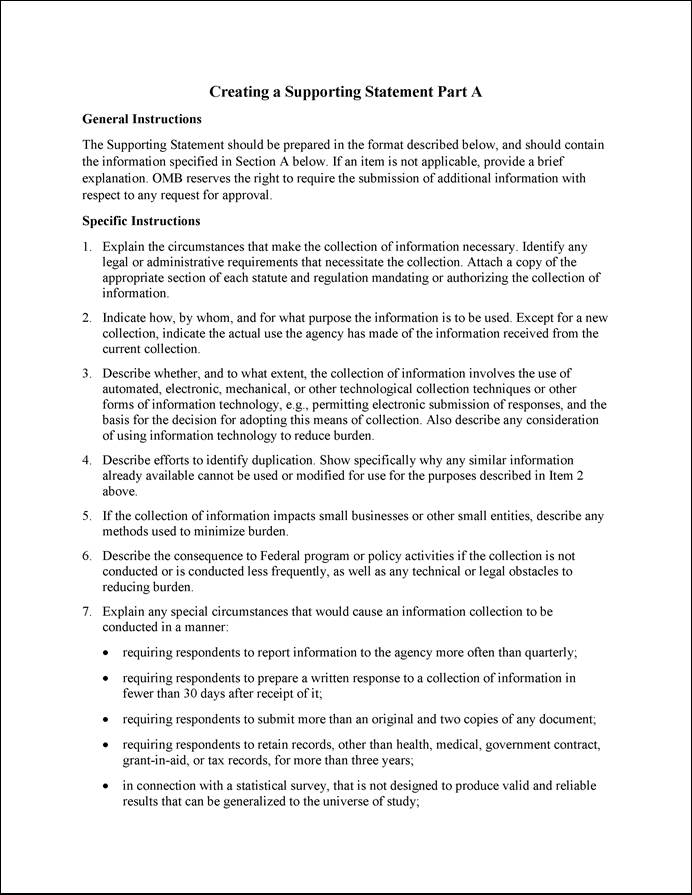

Burden Analysis Requirements and Guidance

The PRA requires agencies to analyze the potential burdens that their information collections will impose on the public if approved. To carry out this requirement, OMB guidance directs agencies to document their burden analyses as part of their ICR submissions, including in the supporting statements that agencies provide to OMB for review. OMB uses agencies’ responses in the supporting statement to understand the proposed collection’s purpose and practical need, as well as to assess agencies’ efforts to avoid imposing excessive burdens on the public (see fig. 1 for an example of this process).

Figure 1: Illustrative Example of Agencies’ Efforts to Analyze Administrative Burdens for Information Collections

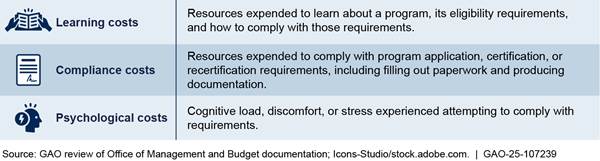

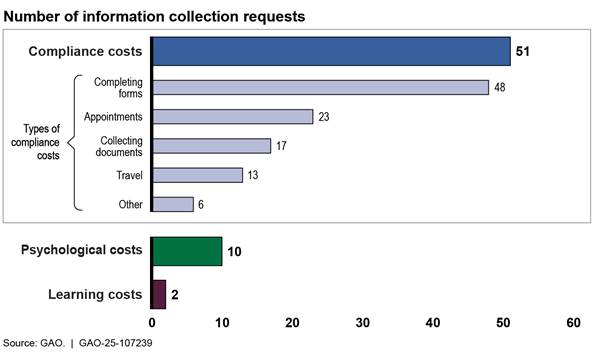

Through EO 14058, issued in December 2021, President Biden directed the head of OIRA to coordinate with relevant interagency councils to develop guidance for agencies to identify specific steps to reduce information collection burdens on the public. The EO states that reducing burdens can enhance the public’s access to programs and services administered by those agencies. In April 2022, OMB issued its M-22-10 guidance to assist agencies in carrying out the goals of the EO. The guidance, along with OMB’s subsequent memo reviewing strategies for reducing administrative burdens, directed federal agencies to ensure that their ICR supporting statements discuss the full range of costs—learning, compliance, and psychological—experienced by members of the public in completing information collections, with an emphasis on how some groups may experience higher costs than other groups.[13] (see fig. 2)

· Learning costs. Resources expended to learn about a program, its eligibility requirements, and how to comply with those requirements.

· Compliance costs. Resources expended to comply with program application, certification, or recertification requirements, including filling out paperwork and producing documentation.[14]

· Psychological costs. Cognitive load, discomfort, or stress experienced attempting to comply with requirements.

Figure 2: Examples of Burdens Experienced by Individuals in Meeting Information Collection Requirements for Federal Benefit Programs

OMB expects agencies to consult with groups external to the federal government beyond required notices in the Federal Register and to document their efforts. OMB states that such consultation can include outreach to program applicants and participants, subject matter experts, advocacy groups, and front-line staff outside the federal government who help administer the programs. OMB states that this documentation should include an explanation for how these consultations led the agency to update their information collections and burden analyses, if at all.

Use of OMB’s Generic Clearance Process for Burden Analysis

Federal agencies may also develop information collections to better understand the administrative burdens that program requirements impose on their customers. For example, agencies may develop surveys to collect information on the public’s experiences with a program’s application process. OMB has stated that the time needed to obtain approval through the PRA’s standard clearance process described above can sometimes deter agencies from developing such information collections. To address this issue, OMB has issued guidance to agencies that identifies opportunities to use exemptions from the standard PRA clearance process.[15] These opportunities include the use of OMB’s generic clearance process. They also include situations where agencies intend to make only non-substantive or de minimis changes to existing information collections.

Through its M-22-10 guidance, OMB reiterates the importance of OMB’s generic clearance process.[16] At the time OMB issued its guidance, most but not all of the CFO Act agencies had generic clearances for collecting customer feedback.[17] The initial plan would need to go through the standard notice and comment process, but the agency would not need to seek further public comment on each specific information collection that falls within the plan. Instead, the agency would only obtain OMB approval, subject to the terms of the generic clearance developed during the prior OMB review. Generic clearances are appropriate when agencies can determine the need and usefulness of information collections in advance but cannot yet determine their details. Most generic clearances cover information collections that are voluntary, low-burden, and uncontroversial. Generic clearances can help facilitate a variety of timely forms of public engagement, such as customer service surveys, focus groups, semi-structured interviews, and pre-testing.

Guidance and Requirements for Institutionalizing Burden Reduction

OMB’s M-22-10 guidance encourages agencies to empower staff to identify and support burden reduction opportunities, where appropriate. The guidance identifies PRA staff and officials responsible for overseeing Enterprise Risk Management efforts as potential advocates for reducing burdens.[18] However, agencies may also develop specific teams dedicated to improving CX, including through reducing burdens. Efforts to reduce administrative burdens often require agencies to change existing processes, incurring costs and introducing potential risks. By providing staff with sufficient authority and commitment to reduce administrative burdens, agencies can more effectively manage such tradeoffs and institutionalize burden reduction as a long-term priority.

EO 14058 further directs agencies to integrate CX priorities, as appropriate and consistent with applicable law, into a variety of performance management activities.[19] These activities include strategic plans, annual performance plans and reports, priority goals, and individual performance plans for senior executives.

· Strategic plans. At least every 4 years, federal agencies are required to issue strategic plans that articulate their fundamental missions and lay out long-term goals.[20] Through these plans, agencies are required to set outcome-oriented strategic goals that explain how they intend to achieve their missions. Agencies are also required to identify strategic objectives that articulate specific outcomes or impacts that they intend to achieve through their activities.

· Performance plans and reports. Agency performance plans provide the linkages between agencies’ near-term activities and their longer-term goals. Agencies express these linkages through the development of performance goals.[21] Performance goals are target levels of performance to be achieved for an activity in a given timeframe. Such targets are generally expressed as tangible, measurable objectives or as quantitative values. On an annual basis, agencies are required to prepare performance plans for the current and next fiscal year and performance reports summarizing progress made in the prior 5 fiscal years.

· Agency priority goals. Agency priority goals are a subset of performance goals that reflect agencies’ highest priorities, as determined by the heads of those agencies. Agencies set targets and milestones and report progress for priority goals on a quarterly basis. Agencies develop priority goals every 2 years.

· Individual performance plans for senior executives. Federal agencies are required to establish performance management systems that hold senior executives accountable for individual and organizational performance. Senior executives’ performance plans should be aligned with their agencies’ outcome-oriented organizational performance goals.

OMB Circular A-11 provides government-wide policies and guidance for federal agencies to follow in preparing and reporting on their strategic plans, performance plans and reports, and agency priority goals. These policies and guidance are intended to assist agencies in implementing federal performance planning and reporting requirements required by the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993, as amended by the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010.[22] As agencies implement EO 14058 directives to integrate CX priorities into their performance management activities, successfully implementing OMB’s Circular A-11 policies and guidance for performance management can also help to ensure that these activities are effective in helping agencies achieve their intended results, including through reducing administrative burdens.

EO 14058’s performance management directives build on other federal efforts to leverage agency planning processes to prioritize activities that may reduce administrative burdens. Beginning in 2018 and annually thereafter, OMB has directed each agency designated as a High Impact Service Provider (HISP) to create an annual CX action plan outlining actions to improve customers’ experiences with their services.[23] These CX actions provide agencies with opportunities to integrate burden reduction and CX priorities into performance management activities in addition to those addressed through EO 14058.

Agencies Face Challenges Implementing OMB’s Burden Reduction Guidance

Agencies Have Not Fully Addressed OMB’s Burden Reduction Guidance in Their ICRs

We reviewed supporting statement documentation for 51 ICRs for federal benefit programs. These ICRs were developed by nine CFO Act agencies from April 13, 2022, to April 13, 2024, and approved by OMB. The nine preparing agencies estimated that each ICR would annually impose at least 75,000 burden hours on the public.[24] The ICRs encompass information collections that individuals or households are required to complete to receive federal benefits. They include initial program applications and supporting documentation requirements. They also include agency reporting requirements that beneficiaries must meet to remain eligible for benefits over time, such as requirements to periodically provide income information or medical evidence. Generally, each ICR we reviewed focuses on one federal program and information collections relevant to that program (see fig. 3).

Note: GAO identified 8,613 information collection requests (ICRs) submitted to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) during the two-year period following OMB’s issuance of M-22-10 in April 2022 that OMB subsequently approved. We then selected for analysis those 51 ICRs that are related to federal benefit programs and are expected to impose burdens of at least 75,000 hours per year.

We reviewed each ICR’s supporting statement to determine how it addressed three selected elements of OMB’s April 2022 burden reduction guidance:

· the full range of administrative burdens that individuals may experience in meeting the ICR’s information collection requirements;

· the extent to which certain groups of respondents may experience higher burdens than others; and

· external engagement with the public beyond the notice-and-comment process.

In conducting our review, we did not assess agencies’ compliance with OMB’s M-22-10 guidance, including whether agencies should have more fully addressed certain elements in their ICR supporting statements that they did not. This is because OMB’s burden reduction guidance does not direct agencies to address in their supporting statements what aspects, if any, of these elements may not be applicable to a given ICR. For example, the guidance does not direct agencies to identify types of administrative burdens that may not be relevant to an ICR when documenting the full range of burdens imposed by that ICR. We also did not assess the extent to which not fully addressing each of the three guidance elements may have affected the accuracy or completeness of agencies’ burden analyses.

We found that most ICRs we reviewed did not fully address the three selected guidance elements.

· Addressing the full range of burdens. OMB states that agencies should document the full range of administrative burdens—including learning, compliance, and psychological costs—that individuals may experience when attempting to meet an ICR’s information collection requirements. We found that agencies reported compliance costs for all 51 ICRs we reviewed. In addition, 10 reported psychological costs, and two reported learning costs (see fig. 4).

Note: GAO identified 8,613 information collection requests (ICRs) submitted to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) during the two-year period following OMB’s issuance of M-22-10 in April 2022 that OMB subsequently approved. We then selected for analysis those 51 ICRs that are related to federal benefit programs and are expected to impose burdens of at least 75,000 hours per year.

Agencies discussed time spent completing forms for almost all ICRs we reviewed (48). For some ICRs, agencies reported additional compliance costs, such as time spent waiting for an appointment or interview to begin. For example, in its ICR documentation for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), USDA estimated that applicants will spend 10 minutes collecting documents, 20 minutes traveling to and from a WIC clinic, and 35 minutes being interviewed at the clinic and reading instructions.[25] The agency also reported that—once certified to receive WIC benefits—individuals will need to spend an estimated 30 minutes to pick up the WIC instrument used to purchase food.[26] Agencies quantified compliance costs for 44 ICRs. For seven ICRs, agencies qualitatively discussed sources of compliance costs, such as application forms and supporting documentation requirements.

Agencies discussed psychological costs for ten of the ICRs. They did so by describing potentially sensitive questions included in the ICR. Others identified privacy concerns that program participants may have about authorizing access to certain personal information, such as financial data from payroll providers.

Agencies discussed learning costs for two ICRs. For one, the agency did so by qualitatively discussing how an individual could learn more about the benefit program’s application. For the other, the agency quantified the estimated time that applicants would need to learn about a program and determine their eligibility.

· Adversely affected groups. OMB directs agencies to use their burden analyses to mitigate burdens on individuals that systematically experience higher burdens than others in meeting information collection requirements. OMB also notes that analyzing burdens associated with adversely affected groups is consistent with the goals of the PRA.[27] We reviewed our selected ICRs to determine how, if at all, agencies considered how certain groups may face adverse challenges in completing the information collections. We identified only one ICR for which the preparing agency identified groups that may experience disproportionately higher burdens. We identified 18 additional ICRs for which agencies documented prior steps taken to mitigate disproportionate burdens on some groups but not remaining opportunities. For example, USDA’s documentation shows that USDA provides its Free and Reduced Price School Meals application in 49 languages other than English, which could reduce burdens for people who have limited English proficiency.

· External consultation. OMB directs agencies to document their efforts to consult with groups external to the federal government beyond the required publication of notices in the Federal Register for notice and comment. OMB states that such consultation can include outreach to program applicants and participants, subject matter expects, advocacy groups, or front-line staff outside the federal government who help administer the programs. The guidance also explains that this documentation should include discussions of how these consultations led agencies to update their information collections and burden analyses. Regular consultation with the public during the ICR renewal process is valuable to understand how burdens may change over time due to demographic or technological changes. For example, one ICR documents how the agency worked with individuals to update specific forms, so they could be read with a particular screen reader.

We found that agencies reported on their efforts to consult with external stakeholders beyond the notice-and-comment process in 17 of the 51 ICRs we reviewed. For example, for one ICR, the Department of Health and Human Services documented its consultation with social scientists to design and conduct cognitive interviews concerning how people react to application questions about race and ethnicity. For nine of these ICRs, agencies also explained how they made changes or updates to their ICRs in response to these external consultations. For example, in its ICR for the Summer Food Service Program, USDA described how its consultation with state agencies helped shape the burden estimates for the collection.

Thirty-four of the ICRs we reviewed did not document efforts to consult with external stakeholders, as directed, beyond the notice-and-comment process. For example, in one ICR, an agency explained its lack of external consultation by saying that it solicited external comments when the form was first developed and approved by OMB years earlier. The agency also stated that no problems have been identified with its procedures since this initial consultation.

OMB’s Supporting Statement Instructions Do Not Fully Incorporate Its Burden Reduction Guidance

Agencies have not fully addressed OMB’s April 2022 burden reduction guidance in their ICRs for federal benefit programs partly because OMB’s supporting statement instructions do not fully incorporate the guidance. OMB reviews agencies supporting statements in determining whether proposed ICRs would impose reasonable burdens on the public and comply with other legal requirements. To facilitate its review, OMB requires agencies to structure their supporting statements as a series of responses to 18 instructions provided by OMB (see app. III). OMB’s instructions do not fully incorporate OMB’s burden reduction guidance elements in the following ways:

· Burdens that are assessed qualitatively. OMB’s M-22-10 guidance states that a supporting statement should document the respondent’s beginning-to-end experience for completing information collections, including by documenting relevant compliance, psychological, and learning costs. The guidance further directs agencies to discuss learning and psychological costs through their qualitative responses to supporting statement instruction 2. However, this instruction does not relate to learning or psychological costs. Rather, it directs agencies to discuss how, by whom, and for what purpose an information collection is to be used.

· Respondents that may be adversely affected. OMB’s M-22-10 guidance directs agencies to use their analyses to reduce administrative burdens on individuals that systematically experience higher burdens than others in meeting information collection requirements. However, OMB’s supporting statement instructions do not instruct agencies to identify potentially adversely affected groups, such as non-English speakers, individuals in rural areas, or individuals in jurisdictions that have established unique program requirements.[28] Rather, instruction 12 directs agencies to express burden hour estimates as a range, if appropriate. For some ICRs we reviewed, agencies provided separate estimates to account for respondents who completed paper versus electronic forms or incurred travel costs. Such estimates may indicate that some groups, such as those with limited technological proficiency, may face higher burdens than others in completing an information collection. However, they do not identify these groups or capture the extent to which total burdens that they experience may be higher than those experienced by other groups.

· Results of external engagement. OMB’s M-22-10 guidance directs agencies to consult at least every 3 years with groups external to the federal government beyond the required publication of notices in the Federal Register. M-22-10 also states that agencies should document the results of these consultations, including any corresponding updates made to their information collections or quantitative burden estimates. OMB’s supporting statement instruction 8 does note that agencies should consult with persons outside the agency at least every 3 years. However, the instruction does not direct agencies to document the results of these consultations.

Officials from our three selected agencies said their agencies prioritize ensuring that ICRs meet requirements for OMB approval, as reflected through OMB’s supporting statement instructions. Some officials also stated that OMB’s burden reduction guidance and the supporting statement instructions are misaligned, and this creates uncertainty about how to address the guidance in their ICRs. They also acknowledged that, as a result, their agencies may not fully implement OMB’s burden reduction guidance, as shown through our review of 51 ICRs. Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) and SSA officials told us that their agencies have developed internal guidance in response to this misalignment. OMB staff we interviewed neither agreed nor disagreed that its burden reduction guidance and supporting statement instructions are not fully aligned.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, agencies should communicate quality information externally so that those external entities can help agencies achieve their objectives.[29] Until OMB updates its supporting statement instructions to more fully reflect its burden reduction guidance, agencies may continue to submit ICRs to OMB for review and to the public for comment, that do not fully incorporate OMB’s guidance. By not fully implementing OMB’s burden reduction guidance, agencies may limit the completeness and transparency of information available to OMB and the public for assessing whether the burden imposed by federal benefit programs are reasonable. Agencies may also be missing opportunities to identify and prioritize resources toward reducing those administrative burdens that would most benefit the public.

Agencies Have Used the Generic Clearance Process to Better Understand Burdens

As part of its guidance, OMB encourages agencies to use long-standing PRA flexibilities, particularly the generic clearance process, when developing information collections to better understand potential administrative burdens experienced by respondents. We found that all 24 CFO Act agencies have generic clearances to collect CX information. Each of our three selected agencies—USDA, VA, and SSA—has multiple generic clearances and is using the fast-track process to obtain OMB’s approval for at least some information collections.[30] These three agencies had each developed generic clearances prior to the issuance of M-22-10. Since then, each agency has continued to use these clearances to collect routine customer feedback to better understand and potentially reduce administrative burdens for their programs or services.

USDA. USDA has five generic clearances relevant to its nutrition assistance programs. These include two department-level generic clearances relevant to collecting information on CX and service delivery across USDA. They also include three FNS generic clearances that FNS uses, in part, to better understand and address challenges people may face in accessing FNS nutrition benefits, including challenges related to learning about FNS programs, eligibility criteria, and how to obtain benefits. These include a clearance to collect CX information.[31] FNS has expanded its use of collections covered by these three generic clearances over time. For example, in 2023 FNS used the fast-track process to receive OMB approval for an information collection intended to help FNS gather information about WIC participants’ experiences with shopping using WIC benefits. FNS has reported that it intends to use the results of this effort to inform its strategies for improving WIC beneficiaries’ shopping experiences and reducing administrative burdens associated with using WIC benefits.

VA. VA has two department-level generic clearances to collect customer feedback relevant to VA’s delivery of health care services. VA has used one long-standing departmental generic clearance to collect qualitative feedback from VA customers concerning the effectiveness of services provided by its three component agencies. VA uses a second generic clearance to collect customer experience information. For example, VA has developed an information collection under this clearance to interview active-duty military servicemembers, recently separated veterans, and family members about the transition to civilian life. VA reported that it will use this information to improve the usefulness of materials provided to servicemembers, making them more aware of resources and benefits for which they are eligible. These efforts could reduce learning costs that servicemembers face in accessing such services.

SSA. SSA has three department-level generic clearances to collect customer feedback on SSA programs and services. One generic clearance encompasses SSA’s information collections that are eligible for fast-track approval. These smaller scale collections are intended to collect qualitative information, such as open-ended requests for customer feedback. A second clearance encompasses SSA’s quantitative and larger scale qualitative customer satisfaction surveys offered to SSA customers. SSA administers these surveys by telephone, by mail, and online. SSA uses a third generic clearance to collect customer feedback data, support more in-depth customer research, conduct user testing of services and digital products. SSA officials said the agency has developed collections under the third generic clearance to gather customer feedback on the design of SSA’s website. Officials said that SSA used insights from this feedback to redesign its website so that people attempting to access SSA benefits or services could more clearly identify steps that they need to complete. These improvements could help reduce compliance costs that individuals experience in applying for these benefits or services.

Agencies Have Established Customer Experience Offices that Identify and Support Burden Reduction Activities

According to OMB’s M-22-10 guidance, agencies are expected to identify both short-term and long-term initiatives to minimize administrative burdens on the public. The guidance further encourages agencies to empower staff to advocate for reducing administrative burdens. As of December 2024, USDA, VA, and SSA had each established a department-wide CX office led by an official in a dedicated CX position. On February 24, 2025, SSA announced the closure of its Office of Transformation. This office had previously overseen SSA’s CX efforts. According to SSA, the agency’s Office of Operations will oversee SSA’s CX efforts moving forward.

As of December 2024, each CX office was taking action to facilitate its agency’s efforts to reduce some administrative burdens for federal benefit programs and services as part of its broader efforts to improve CX. These efforts included working with department components to understand burdens and collect data to make improvements to CX. The offices varied in terms of their maturity and scope of activities (see table 1).

|

Customer experience office |

Year established |

Fiscal year 2024 full-time equivalents |

|

|

Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Experience Office |

2015 |

312 |

|

|

Department of Agriculture Customer Experience Office |

2018a |

8 |

|

|

Social Security Administration Office of Transformationa |

2023 |

8 |

|

Source: GAO review of agency documentation and agency interviews. | GAO‑25‑107239

aOn February 24, 2025, the Social Security

Administration (SSA) announced the closure of its Office of Transformation. The

Office of Transformation included SSA’s Office of Customer Experience, Office

of Experience Design, and Office of Change Management. Each office was involved

in SSA’s customer experience activities. SSA officials told us that the

agency’s Office of Operations will oversee SSA’s CX efforts moving forward.

Working with Components to Understand Burdens

Selected agencies have focused on reducing administrative burdens in relation to their EO 14058 directives and High Impact Service Provider (HISP) commitments. Each agency’s CX office had coordinated with other agency components to better understand some of these burdens and how to address them.

· Staff from USDA’s CX office meet monthly with leadership from each of USDA’s six HISPs to help those HISPs reduce burdens and improve CX. According to agency officials, they collect and analyze relevant data on program beneficiaries. USDA officials said the CX office is beginning to expand the meetings to include USDA’s other component agencies.

· In 2023, SSA’s CX office supported a cross-agency team’s efforts to learn about challenges, including administrative burdens, that people experience in trying to obtain and maintain adult disability benefits. For example, the team learned through interviews and focus groups that applicants were unprepared for the level of detail needed for an initial disability claims interview. This led SSA to prioritize efforts to better prepare applicants for these interviews, which would reduce compliance costs for applicants.

· VA’s Veterans Experience Office (VEO) includes a team that has partnered with VA’s administrations to conduct interviews with veterans, their families, caregivers, and survivors to better understand these customers’ experiences and preferences in using VA services. According to VA, the team engages with these customers when evaluating existing services and when designing improvements to make services more accessible.

Collecting Customer Experience Data

VA’s VEO launched an enterprise-wide platform to collect high-level data on customers’ experiences with VA services. VEO assesses service effectiveness as well as veterans’ sense of ease and their emotional experiences with VA services.[32] VEO also has responsibility for assessing CX data. VA officials said that VEO teams regularly meet with program offices to discuss potential challenges, including administrative burdens, identified through the team’s analysis of feedback data and potential solutions.

SSA developed standardized CX surveys for major online services, including services for obtaining retirement and adult disability benefits. As of December 2024, SSA has also centralized how it collects feedback for major services across different interaction channels, including website, phone, and office interactions. SSA has previously reported that centralizing and standardizing its research can enable the agency to obtain customer feedback more quickly and help to drive faster process changes that can improve access to SSA benefit programs.

USDA’s CX office is coordinating with each of USDA’s component agencies to implement tools for collecting customer feedback that can be used to better understand administrative burdens experienced by individuals attempting to obtain or retain benefits administered by USDA. By January 2024, USDA offices had coordinated to launch 10 CX surveys. According to officials from USDA’s CX office, all components will begin collecting feedback in fiscal year 2025, and the CX office will elevate important insights to the attention of programming components.

Improving Customer Experience

VA’s and SSA’s CX offices worked to implement burden reduction initiatives as part of their efforts to improve CX.

· VA.gov and VA mobile app. VEO works with component agencies and VA’s IT office to understand its customers’ digital service needs and help inform the design of VA’s website and mobile app. For example, Veterans can use the mobile app to message VA health care teams and upload documentation electronically, among other features. These features could help veterans access VA medical care more efficiently. Since its implementation in 2021, the mobile app has been downloaded more than 2 million times and received high customer satisfaction scores from its users, according to VA.

· SSA electronic signature and upload documents initiative. SSA officials told us that SSA began an initiative in 2022 to eliminate signature requirements from its forms where appropriate. SSA has said that this initiative is intended to make it easier for individuals to provide SSA with documentation needed to access SSA services. SSA officials said that this initiative made limited progress at first due to concerns that removing such signature requirements could increase fraud and other risks. However, SSA officials said that SSA’s Office of Transformation assumed leadership over the initiative in 2023. Since then, SSA determined that it could manage risks while modifying signature requirements. In December 2024, SSA officials told us that the agency had removed signature requirements for 43 of these forms,[33] allowing for electronic signatures on 39, and enabling customers to self-submit forms and some types of supporting documentation electronically. SSA planned to review additional forms for signature removal. SSA officials said the initiative had helped the agency to better address and balance the tradeoffs between fraud risks and burden reduction.

· SSA Supplemental Security Income simplification initiative. SSA’s Office of Transformation supported agency efforts to improve the application process for those applying for Supplemental Security Income (SSI). In November 2022, we found that most SSI claimants were not yet able to apply for SSI benefits online despite SSA’s efforts to expand remote service delivery, including by phone and internet. We recommended that SSA develop a plan—with clear steps, goals, metrics, and timelines—for enabling claimants to apply for SSI benefits online. SSA concurred with the recommendation, and we will continue to monitor their progress in developing a plan.[34]

According to USDA officials, USDA’s CX office has not had had a significant role in coordinating with USDA component agencies to address administrative burdens. USDA’s efforts to implement EO 14058 directives and HISP commitments are generally applicable to specific USDA component agencies, such as the Food and Nutrition Service. USDA’s CX office coordinates with those component agencies to prepare CX action plans.[35]

Agencies Have Taken Steps to Integrate Burden Reduction Priorities into Performance Management Activities

We reviewed USDA, VA, and SSA performance plans, performance reports, and quarterly agency priority goal documentation issued in fiscal year 2024. We found that each agency has taken steps to integrate burden reduction priorities into their performance management activities for selected programs and services—specifically their strategic goals, strategic objectives, and performance goals.[36] Agency officials also told us how they have integrated CX priorities into the individual performance plans for senior leaders.

In conducting our review, we focused on performance management activities relevant to USDA, VA, and SSA benefit programs and services with the highest fiscal year 2022 obligations. Agencies’ performance management activities for these programs and services address priorities expressed through agency-specific EO 14058 directives or agencies’ HISP commitments. They also address additional opportunities to reduce administrative burdens.

Integrating burden reduction priorities into strategic goals and objectives can help these agencies to clarify the outcomes they intend to achieve through their burden reduction efforts. In addition, performance goals for these objectives can help these agencies to assess short-term progress toward these goals and objectives, highlight the contributions of specific activities, and promote the agency’s accountability for achieving its goals related to reducing burdens.

For the three performance activities, we assessed each identified strategic goal, strategic objective, and performance goal that we identified as relevant to reducing administrative burdens against selected elements of OMB’s Circular A-11 guidance for performance management.[37] We selected these elements because we determined that they were important to agencies’ efforts to both achieve progress toward their missions and to communicate that progress. For example, we assessed strategic objectives against OMB guidance elements that direct agencies to identify responsible personnel, report progress, and identify next steps for their objectives. We assessed performance goals against OMB guidance that directs agencies to report results, set targets, and explain changes to their performance goals. For each of our selected agencies, we found that identified performance management activities generally addressed each of these selected elements.

USDA Nutrition Assistance Programs

We identified three USDA objectives related to reducing administrative burdens for nutrition assistance programs. These objectives are to (1) increase food security; (2) promote better use of technology and shared solutions; and (3) take data-driven, customer-focused approaches.[38] USDA’s achievement of these objectives depends in part on the implementation efforts of states, territories, tribes, and other partners. However, USDA maintains performance goals regarding participation in these programs. These performance goals can help the agency to assess efforts to reduce administrative burdens experienced in accessing these programs.

USDA’s objective to increase food security includes expanding WIC online purchasing as a supporting strategy. USDA is considering facilitating WIC online shopping through rulemakings and other mechanisms. Other strategies for this objective include expanding the use of mobile technologies for accessing WIC benefits. Expanding WIC purchasing both online and through mobile technologies is intended to reduce administrative burdens that individuals face in using WIC benefits.

USDA says it is promoting better use of technology by streamlining policies and modernizing systems to reduce barriers to accessing USDA programs. This strategy relates to the EO 14058 directive that USDA identify opportunities to simplify enrollment and recertification for nutrition assistance programs. USDA reported some information relevant to this strategy as part of its annual equity action plan issued in January 2024.[39]

USDA strategies for taking data-driven, customer-focused approaches to service delivery include piloting the use of mobile technologies for the purpose of accessing Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. In August 2024, FNS reported that it had selected states to participate in the pilot project, but those states were still designing their individual pilots. In 2018, legislation required FNS to authorize up to five mobile payment pilots for the use of personal mobile devices in place of SNAP Electronic Benefit Transfer cards to conduct SNAP transactions.[40]

Regarding accountability for senior executives, USDA officials told us that FNS senior executive performance plans include an objective through which senior executives are assessed based on their efforts to identify and implement actions that will improve the quality of services provided to stakeholders and increase the overall satisfaction with a specific interaction or a service requested.

VA Health Care and Benefits Activities

VA strategic objectives related to burden reduction for health care activities include (1) providing VA customers with accessible services and easy to understand information, (2) delivering benefits and services to underserved and at-risk veterans, and (3) providing veterans with better tailored health care.[41]

To achieve the first objective, VA’s strategies include expanding digital services through VA.gov and the VA mobile app. They also include providing multi-channel customer support.[42] VA has reported on progress made and next steps for these efforts. For example, VA reported that in fiscal year 2023 it made self-service enhancements to VA.gov and the mobile app, including by enabling veterans to submit supplemental information online regarding previously decided benefits claims.

VA’s strategies to deliver benefits and services to underserved and at-risk populations include reaching out to transitioning servicemembers at risk for food insecurity and connecting them to resources and other assistance programs. VA’s performance goal for this strategy assesses the agency’s efforts to contact eligible veterans who are newly separated from the military. VA reports that it conducted outreach to 77 percent of veterans eligible for outreach in fiscal year 2024, exceeding its target of 55 percent. Such efforts are intended to improve veterans’ awareness of benefits for which they are eligible, thereby reducing their learning costs in accessing these benefits.

To provide veterans with better tailored benefits and health care, VA strategies include expanding use of virtual health technologies. VA intends for this effort to reduce burdens experienced by veterans in accessing health care by reducing the need for in-person appointments, including travel and wait times. In recent years, we have identified challenges that the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has had ensuring that both VHA facility and community care appointments are scheduled in a timely manner.[43] In fiscal year 2024, VA developed two new performance goals to assess veterans access to telehealth services. In January 2025, VA reported that it provided real-time video telehealth services to 32 percent of eligible veterans at their homes or other non-VA locations in fiscal year 2024, exceeding its target of 24 percent. VA also reported that it provided telehealth services to 44 percent of eligible veterans in fiscal year 2024, exceeding its goal of 35 percent.[44]

VA officials told us that individual performance plans provide senior executives with the option to either develop a CX Action Plan for their component or commit to increasing customer satisfaction by a certain percentage for a key program or service provided by their component.

SSA Digitization and Modernization Activities

SSA objectives related to reducing administrative burdens include objectives to (1) expand digital services, (2) build a more customer-focused organization, (3) identify and address barriers to accessing SSA services, and (4) improve organizational performance and policy implementation.[45]

SSA’s strategies for expanding digital services included implementing the agency’s electronic signature and document upload initiatives, as discussed earlier in this report.[46] SSA’s performance goals for this objective include increasing the number of customer transactions completed on SSA’s website. SSA reported that it met its target to increase total transactions by 5 million in fiscal year 2024 compared to fiscal year 2023.

To achieve its objective to build a more customer-focused organization, SSA’s strategies include working to expand access to electronic medical evidence for disability determinations. SSA’s performance goals for this objective include supporting increased submissions of electronic medical evidence. SSA received 58 percent of this evidence electronically in fiscal year 2024, exceeding its goal of 57 percent. SSA reported that software improvements and new partnerships in fiscal years 2024 and 2025 will support progress toward this goal.

To identify and address barriers to accessing SSA services, SSA has worked to reduce learning costs for SSA programs. SSA’s strategies include conducting outreach initiatives to make individuals aware of their potential eligibility for SSA programs. For this objective, SSA also has established a performance goal to assess efforts to improve customer satisfaction with its website. SSA reported that it is continuing to make improvements to its website that should provide the public with greater clarity regarding their eligibility for SSA programs and how to apply. SSA reported that website satisfaction rose to about 81 percent in fiscal year 2024, exceeding its target of 71 percent.

To improve organizational performance and policy implementation, SSA’s strategies include simplifying policies and modernizing processes that can help reduce program compliance costs. For example, SSA reported that it is taking steps to streamline routine wage reporting for SSI, which can make it less burdensome for beneficiaries to retain SSI benefits.

SSA officials told us that SSA performance plans include a goal in senior executives’ performance plans that those executives contribute toward achievement of the Commissioner’s priority goals and high customer satisfaction. Agency executives may achieve this goal, in part, through identifying and reducing burdens experienced by individuals attempting to access SSA programs and services.

Conclusions

OMB has provided guidance to help agencies more fully and transparently document administrative burdens imposed on individuals accessing federal benefits, with the goal of reducing these burdens. However, not all ICRs have addressed three elements of this guidance, and OMB’s supporting statement instructions that agencies use to submit their ICRs do not fully incorporate the guidance. As a result, agencies are at risk of developing ICRs that do not document the full range of burdens imposed on the public by these information collections. By updating its supporting statement instructions to address the full scope of its burden reduction guidance, OMB could help ensure that agencies more fully document administrative burdens for benefit programs. More complete analyses could help agencies, OMB, and the public better identify opportunities to reduce these burdens. They could also help agencies better prioritize their CX and component agency resources toward reducing those burdens that will most benefit the public and enable agencies to make progress toward their burden reduction goals.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Director of the Office of Management and Budget should update OMB’s supporting statement instructions for information collection requests to fully incorporate all of the elements of its burden reduction guidance.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Agriculture and Veterans Affairs, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Social Security Administration for review and comment. The Departments of Agriculture and Veterans Affairs and the Social Security Administration provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. The Social Security Administration also provided written comments that are reprinted in appendix V. The Office of Management and Budget did not provide comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Agriculture, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, and the Acting Commissioner of Social Security. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at jonesy@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VI.

Yvonne D. Jones

Director, Strategic Issues

List of Requesters

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Gerald E. Connolly

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Lisa Blunt Rochester

United States Senate

The Honorable Angie Craig

House of Representatives

The Honorable Sara Jacobs

House of Representatives

The Honorable Doug LaMalfa

House of Representatives

The Honorable Lucy McBath

House of Representatives

The Honorable Dan Newhouse

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jimmy Panetta

House of Representatives

The Honorable Scott Peters

House of Representatives

This report examines the extent to which (1) federal agencies have implemented the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) information collection request (ICR) guidance to reduce administrative burdens associated with federal benefit programs, (2) selected agencies have taken actions to support burden reduction efforts for federal benefit programs, and (3) selected agencies have integrated burden reduction priorities for federal benefit programs into their performance management activities.

For our first objective, we identified 8,613 approved ICRs submitted to OMB from when it issued its guidance in April 2022 to April 2024.[47] Of these 8,613 ICRs, we focused our review on the 51 ICRs, submitted by nine agencies, which met the following criteria:

· The preparing agency was a Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) agency;

· The ICR set requirements that individuals and households must meet to obtain or retain federal benefits; and

· The preparing agency estimated the ICR would impose at least 75,000 burden hours on the public.[48] We used a 75,000 burden hours threshold for our analysis to focus our review on ICRs that impose higher administrative burdens on the public. ICRs that met this threshold accounted for 99 percent of all burden hours imposed by ICRs related to obtaining or retaining federal benefits.

To confirm the accuracy of Reginfo.gov data, we (1) conducted data testing to identify errors, (2) interviewed OMB officials concerning the data’s reliability, (3) and reviewed OMB instructions provided to agencies to ensure that data entered into the Reginfo.gov database are complete.[49] We concluded that the data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes of identifying ICRs to review.

We reviewed supporting statement documentation for each of the 51 ICRs to assess whether each ICR fully addressed three selected elements of OMB’s M-22-10 burden reduction guidance. These elements summarize the OMB guidance provisions relevant to burden analysis. They address documenting (1) the full range of administrative burdens that individuals may experience in meeting the ICR’s information collection requirements, (2) the extent to which certain groups of individuals may experience higher burdens than others, and (3) external engagement with the public beyond the notice-and-comment process. We also compared OMB’s M-22-10 guidance to OMB’s supporting statement instructions to agencies for documenting burden analyses as part of their ICR submissions.[50]

In conducting our review, we did not assess agencies’ compliance with OMB’s M-22-10 guidance, including whether agencies should have more fully addressed certain elements in their ICR supporting statements that they did not address. This is because OMB’s burden reduction guidance does not direct agencies to address in their supporting statements what, if any, aspects of these elements may not be applicable to a given ICR. For example, the guidance does not direct agencies to identify types of administrative burdens, if any, that may not be relevant to an ICR when documenting the full range of burdens imposed by that ICR. We also did not assess the extent to which agencies not fully addressing each of the three guidance elements may have affected the accuracy or completeness of that agency’s burden analyses.

To understand why agencies may not have fully addressed the three selected elements of OMB’s burden reduction guidance in their ICRs, we interviewed officials from OMB’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs and Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA) staff from three selected agencies: the Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Social Security Administration (SSA). We selected these agencies because they administer three of the benefit programs and services with the highest obligations or, if obligations data were unavailable, outlays. To identify program outlay data, we reviewed the Federal Program Inventory, the President’s Budget for Fiscal Year 2024, and agency sources.

For our second and third objectives, we focused our work on the USDA, VA, and SSA benefit programs and services with the highest fiscal year 2022 obligations: USDA nutrition assistance programs administered by the Food and Nutrition Service, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (about $121 billion); VA health care services administered by the Veterans Health Administration (about $109 billion); and SSA’s Supplemental Security Income (about $60 billion) and Social Security Disability Insurance programs (about $142 billion). For our second objective, we interviewed PRA and CX staff at our selected agencies about their efforts to support initiatives to identify and reduce administrative burdens as of December 2024.[51] We focused on efforts relevant to the prioritized programs and services. We reviewed agency documentation of these efforts, where available.

For our third objective, we reviewed USDA, VA, and SSA performance plans, performance reports, and quarterly agency priority goal reports prepared in fiscal year 2024. We used this documentation to identify performance management activities related to reducing administrative burdens for some of the largest benefit programs and services offered by these agencies, as identified above. These activities included strategic goals, strategic objectives, and performance goals.

We compared these activities to agencies’ High Impact Service Provider commitments, as reported on Performance.gov, as well as Executive Order 14058 directives to determine whether identified performance management activities related to these commitments or directives. We then assessed the extent to which documentation for each identified performance management activity incorporated selected elements from OMB’s Circular A-11 guidance.[52] OMB Circular A-11 identifies 26 elements that agencies should address when reporting on their strategic goals, strategic objectives, and performance goals, including agency priority goals, as part of their annual performance plans, annual performance reports, and agency priority goal implementation action plans. We focused our analysis on the 19 guidance elements that we identified as important to agencies’ efforts to achieve progress toward their missions and to communicate that progress. For a full list of selected guidance elements included in our analysis, see appendix IV. We interviewed agency officials about potential gaps in agencies’ performance management documentation. We also interviewed officials about their agencies’ efforts to integrate burden reduction priorities into the individual performance plans for senior executives.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

We identified 8,613 approved information collection requests (ICRs) submitted to the Office of Management and Budget from when it issued its burden reduction guidance in April 2022 to April 2024.[53] Of these 8,613 ICRs, we focused our review on the 51 ICRs, submitted by nine agencies, which met the following criteria:

· The preparing agency was a Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act) agency;

· The ICR set requirements that individuals and households must meet to obtain or retain federal benefits; and

· The preparing agency estimated the ICR would impose at least 75,000 burden hours on the public.[54] We used a 75,000 burden hours threshold for our analysis to focus our review on ICRs that impose higher administrative burdens on the public. ICRs that met this threshold accounted for 99 percent of all burden hours imposed by ICRs related to obtaining or retaining federal benefits.

These ICRs are listed in table 2. For more information on our selection methodology, see appendix I.

|

Agency |

ICR title |

ICR reference number |

|

DHS/FEMA |

Disaster Assistance Registration |

202310-1660-007 |

|

DHS/FEMA |

National Flood Insurance Program Claims Forms |

202301-1660-007 |

|

DHS/FEMA |

Federal Assistance to Individuals and Households Program (IHP) |

202403-1660-002 |

|

DHS/FEMA |

Notice of Loss and Proof of Loss |

202302-1660-001 |

|

DOL/WHD |

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993, As Amended |

202306-1235-001 |

|

ED/FSA |

2024-2025 Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) |

202303-1845-006 |

|

ED/FSA |

William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program (Direct Loan Program) Promissory Notes and related forms |

202203-1845-003 |

|

ED/FSA |

Income Driven Repayment Plan Request for the William

D. Ford Federal Direct Loans and Federal Family |

202312-1845-003 |

|

ED/FSA |

William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan Program, Federal

Direct PLUS Loan Request for |

202308-1845-002 |

|

ED/FSA |

Loan Rehabilitation: Reasonable and Affordable Payments |

202302-1845-002 |

|

ED/FSA |

Borrower Defense to Loan Repayment Universal Forms |

202307-1845-007 |

|

ED/OESE |

Migrant Education Program Regulations and Certificate of Eligibility |

202302-1810-003 |

|

HHS/CMS |

Application for Enrollment in Medicare Part A,

Internet Claim (iClaim) Application Screen, Modernized |

202304-0938-004 |

|

HHS/CMS |

Data Collection to Support Eligibility Determinations

for Insurance Affordability Programs and Enrollment |

202208-0938-007 |

|

HHS/CMS |

Application for Enrollment in Medicare - The Medical Insurance Program (CMS-40B) |

202311-0938-011 |

|

HHS/CMS |

Model Medicare Advantage and Medicare Prescription

Drug Plan Individual Enrollment |

202306-0938-006 |

|

HUD/OH |

Mortgage Insurance Termination; Application for Premium Refund or Distributive Share Payment |

202309-2502-004 |

|

HUD/OH |

Single Family Application for Insurance Benefits |

202401-2502-004 |

|

HUD/PIH |

Family Report, MTW Family Report, MTW Expansion Family Report |

202403-2577-001 |

|

HUD/PIH |

Restrictions on Assistance to Noncitizens |

202303-2577-001 |

|

SBA |

Disaster Home Loan Application |

202311-3245-001 |

|

SSA |

Appointment of Representative |

202203-0960-001 |

|

SSA |

Application for Widow’s or Widower’s Insurance Benefits |

202202-0960-007 |

|

SSA |

Application for Child’s Insurance Benefits |

202210-0960-007 |

|

SSA |

Application for Lump-Sum Death Payment |

202204-0960-010 |

|

SSA |

Request to be Selected as a Payee |

202203-0960-007 |

|

SSA |

Request for Correction of Earnings Record |

202307-0960-003 |

|

SSA |

Request for Waiver of Overpayment Recovery or Change in Repayment Rate |

202310-0960-004 |

|

SSA |

Continuing Disability Review Report |

202305-0960-001 |

|

SSA |

Application for Supplemental Security Income |

202203-0960-008 |

|

SSA |

Disability Update Report |

202303-0960-005 |

|

SSA |

Disability Case Development Information Collections |

202402-0960-002 |

|

SSA |

Disability Report – Child |

202402-0960-001 |

|

SSA |

Social Security Benefits Application |

202208-0960-002 |

|

SSA |

Technical Updates to Applicability of the

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Reduced Benefit Rate for |

202206-0960-013 |

|

SSA |

Authorization for the Social Security Administration

to Obtain Wage and Employment Information from |

202309-0960-002 |

|

USDA/FNS |

7 CFR Part 245 - Determining Eligibility for Free & Reduced Price Meals and Free Milk in Schools |

202307-0584-008 |

|

USDA/FNS |

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women,

Infants, and Children (WIC) Program Regulations - |

202310-0584-003 |

|

USDA/FNS |

7 CFR Part 225, Summer Food Service Program |

202207-0584-004 |

|

USDA/FNS |

Food Distribution Programs |

202305-0584-002 |

|

USDA/FNS |

Senior Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program (SFMNP) |

202211-0584-008 |

|

USDA/FNS |

Final Rulemaking: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program: 2008 Farm Bill Provisions on Clarification |

202006-0584-003 |

|

USDA/RHS |

Direct Single Family Housing Loan and Grant Programs, 7 CFR 3550 - HB-1-3550, and HB-2-3550 |

202205-0575-001 |

|

VA |

VA Health Benefits: Application, Update, Hardship

Determination - VA Forms 10-10EZ,10-10EZR |

202402-2900-023 |

|

VA |

Application for Disability Compensation and Related Compensation Benefits (VA Form 21-526EZ) |

202205-2900-006 |

|

VA |

Appl. for DIC, Death Pension, and/or Accrued Benefits

(21P-534EZ); Appl. for Dependency and Indemnity |

202209-2900-009 |

|

VA |

Application Request to Add and/or Remove Dependents (VA Form 21-686c) |

202111-2900-008 |

|

VA |

Request for Certificate of Eligibility (VA Form 26-1880) |

202206-2900-002 |

|

VA |

Application For VA Educational Benefits (VA Forms 22-1990, 22-1990e, 22-1990n) |

202211-2900-016 |

|

VA |

Intent to File a Claim for Compensation and/or

Pension, or Survivors Pension and/or DIC |

202111-2900-007 |

|

VA |

Program of Comprehensive Assistance for Family Caregivers (PCAFC) Decision Appeal Forms |

202202-2900-004 |

Source: GAO review of RegInfo.gov information. | GAO‑25‑107239

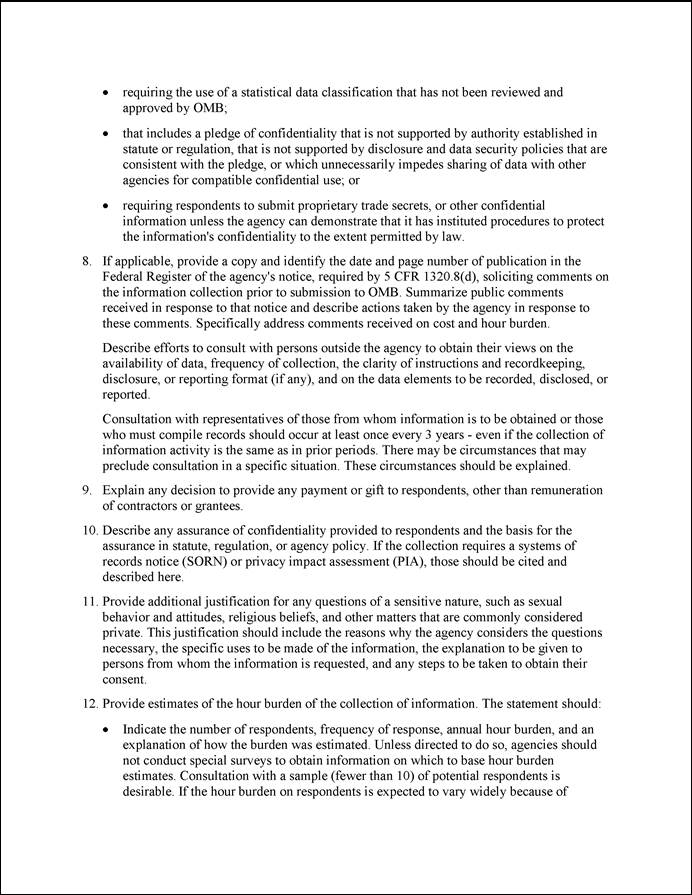

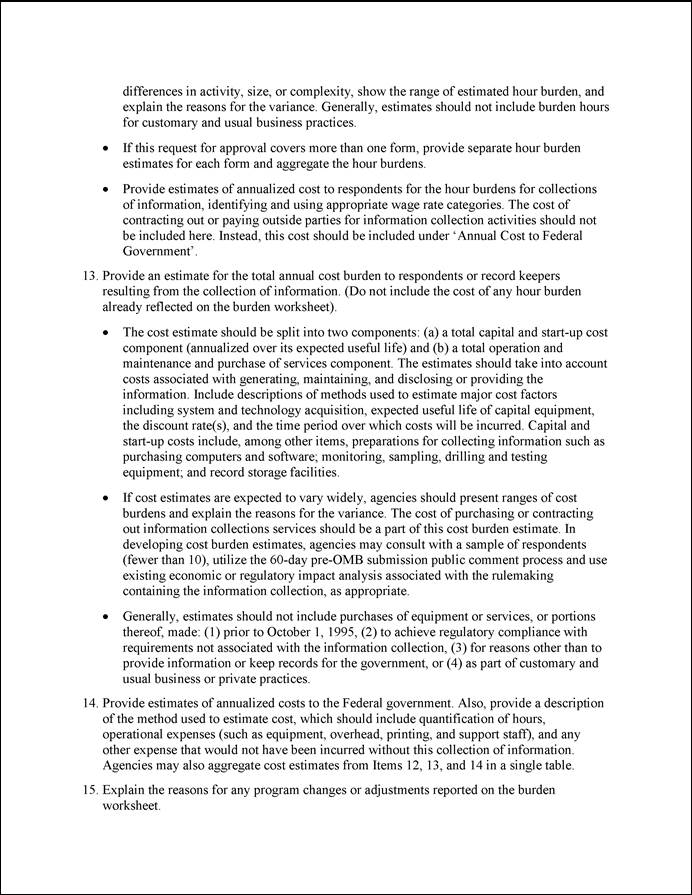

Appendix III: Office of Management and Budget Instructions for Creating a Supporting statement Part A

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) requires agencies to include as part of each information collection request submission to OMB a supporting statement that provides the agency’s rationale for the information collection. On April 13, 2022, OMB also issued M-22-10, Improving Access to Public Benefits Programs Through the Paperwork Reduction Act.[55] OMB M-22-10 provides guidance to agencies for improving their analyses of administrative burdens imposed by their information collections. OMB directs agencies to document their efforts to implement M-22-10 guidance related to burden analysis in Part A of their supporting statements.

OMB requires agencies to structure Part A of their supporting statements as a series of responses to 18 instructions provided by OMB. These instructions are reproduced below and are available on pra.digital.gov. Agencies’ supporting statements are publicly available on reginfo.gov. Both websites are jointly managed by the General Services Administration and OMB.

We reviewed performance plans, performance reports, and quarterly agency priority goal reports prepared in fiscal year 2024 by three selected agencies: the Departments of Agriculture and Veterans Affairs and the Social Security Administration. We used this documentation to identify performance management activities related to reducing administrative burdens for some of the largest benefit programs and services offered by these agencies. These activities included strategic goals, strategic objectives, and performance goals.