ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS

Communication with Users on Water Storage Fees and Cost Estimates Could Be Improved

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Cardell D. Johnson at JohnsonCD1@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107242, a report to congressional committees

Communication with Users on Water Storage Fees and Cost Estimates Could Be Improved

Why GAO Did This Study

Nationwide, the Corps oversees over 400 water storage agreements that collectively provide about 11 million acre-feet of storage in exchange for users sharing O&M costs with the Corps. Prior GAO work found user concern with certain aspects of the Corps’ annual O&M user fee process, including variations in annual fees and a lack of detailed information about them. The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to review the Corps’ practices associated with O&M fees.

This report examines the extent to which the Corps has (1) managed its annual O&M user fee process consistently with selected key practices for federal user fees and (2) developed the 5-year O&M cost estimates as required by law.

GAO selected a nongeneralizable sample of 14 water storage agreements from 10 Corps districts according to criteria such as water storage capacity, reviewed agency documents, and interviewed Corps officials and municipal and industrial water users. GAO compared the Corps’ current practices to GAO’s federal user fee design guide and a 2014 legal requirement.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to the Department of Defense to improve how the Corps both communicates annual O&M fees and provides 5-year O&M cost estimates. The Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works agreed with all three recommendations and described planned actions to implement them.

What GAO Found

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) enters into agreements with municipal and industrial water users, such as local water utilities, for reservoir storage space. Users must annually reimburse the federal government for their portion of the reservoir’s operations and maintenance (O&M) cost, and such reimbursements can be considered user fees. The Corps district offices GAO spoke with followed many key practices for setting user fees. For example, the Corps accounted for the total costs of providing the service and established user-specific fees.

However, these district offices did not follow a key practice related to sharing information with users to help assure them that the fees are set fairly and accurately. The 10 Corps district offices GAO spoke with communicated limited fee information and offered few opportunities for users to discuss the fee. For example, two districts did not provide users with any supplemental information beyond the fee amount and one user in these districts told GAO they regularly request supplemental information from the Corps to better understand their fee. The other eight districts provided users with some supplemental information, but multiple users in those districts told GAO that such information lacked key details on specific O&M costs and activities.

Example of Corps Operations and Maintenance Work

Replacement of riprap stone protection on the outlet channel bank.

Five of the 10 Corps districts GAO spoke with did not provide users with legally required 5-year O&M cost estimates, and the Corps does not yet have an oversight mechanism to ensure these estimates are provided. By law, the Corps is required to notify water users of anticipated O&M costs for the upcoming fiscal year and the following 4 years. Water users can review these estimates to be informed about future costs, such as dam safety risk assessments, which are scheduled every 10 years. All five of the users GAO spoke with who were not provided the estimates said they would be helpful for planning purposes. In December 2024, Corps officials told GAO that headquarters is in the early stages of developing and establishing a mechanism to oversee these estimates but did not provide documentation of this effort. Developing such a mechanism will help assure Corps headquarters that districts provide users with information needed to effectively plan and administer their water supply storage.

No table of contents entries found.

Abbreviations

|

M&I |

municipal and industrial |

|

O&M |

operations and maintenance |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 17, 2025

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

Chairman

The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse

Ranking Member

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) is the world’s largest public engineering agency and manages hundreds of water resources projects, such as reservoirs, across the United States through its civil works program.[1] These projects serve a variety of purposes, including storage for flood control, hydropower, and irrigation. In addition, the Corps implements the water storage provisions of the Water Supply Act of 1958 (as amended) at reservoirs, where it enters into agreements with municipal and industrial (M&I) water users, such as local water utilities, for storage space in reservoirs.[2] Nationwide, there are 135 water storage projects with over 400 storage agreements. These projects collectively provide approximately 10.6 million acre-feet of storage in 26 states, according to Corps documentation.[3] M&I water supply storage agreements are generally in effect for the physical life of a reservoir.[4] The water is used for many purposes, including for use by households, commercial operations, and public supplies.

The Corps neither acquires nor secures the rights to the water, nor does the Corps play a substantial role in the delivery of stored water to users. Instead, it plans, constructs, and operates its reservoirs to enhance the availability of water supplies at the request of users, among other purposes such as flood control. While the federal government operates the reservoirs, federal law requires the user to reimburse the Corps for a portion of the reservoir’s annual operations and maintenance (O&M) costs.[5] For example, the Corps classifies the operations of the dam, reservoir, and supporting infrastructure or equipment to be joint costs, which include costs for labor, utilities, mowing, and janitorial work. The Corps deposits these reimbursements into the U.S. Department of the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts. For fiscal year 2023, the revenues totaled approximately $20 million, according to Corps officials. These payments fit the definition of user fees, which GAO’s design guide for federal user fees describes as related to a voluntary transaction or request for government goods or services above and beyond what is normally available to the public.[6]

The number of water storage agreements has grown over the years. For instance, the number of such agreements nearly doubled from a total of 235 agreements in 1998 to 438 in 2023, according to Corps documentation. Increased demand for storage to help M&I users meet the water supply needs of their customers, combined with reduced water availability stemming from droughts, among other factors, has increased interest in water supply storage.

In August 2017, we reported that some M&I water users raised concerns about certain aspects of the Corps’ annual O&M fee process, including the lack of detailed information and variations in annual fees.[7] During that 2017 review, the Corps also began providing users with annual O&M cost estimates looking ahead over the ensuing 5-year period as required by the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014.[8] These estimates are to assist M&I users in improving planning and administration of water supply storage, as stated in a 2015 Corps Memorandum.[9]

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for us to review the Corps’ practices associated with O&M costs.[10] This report examines the extent to which the Corps has (1) managed its annual O&M user fee process consistent with key practices for federal user fees related to setting fees and sharing related information with users, and (2) developed the 5-year O&M cost estimates as required by law.

To address both objectives, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of 14 water storage agreements from 438 agreements from fiscal year 2023, the most recent fiscal year of available data, listed in the Corps database provided to us in March 2024. To assess the reliability of these data, we (1) reviewed agency documents; (2) manually checked the data for inconsistencies, obvious errors, and outliers;[11] and (3) spoke with knowledgeable officials about data entry processes and controls. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing the geographic distribution of M&I water supply storage and selecting a nongeneralizable sample that allows for illustrative examples.

We selected a nongeneralizable sample of 14 M&I water user agreements using criteria to ensure we included agreements across a range of districts on the basis of the amount of user fees, storage capabilities, and number of agreements or O&M users.[12] The sample was sourced from 10 districts with water storage facilities.[13] Most of the selected agreements came from districts that manage a large number of agreements or a large volume of water (in acre-feet), or that collected the most user fees according to dollar value.[14] These districts managed about 80 percent of all water storage agreements between Corps districts and M&I users in fiscal year 2023. This approach resulted in a diverse sample, reflecting a variety of agreement start dates, storage capacities, O&M user fees, and agreement types, among other things.

To further examine both objectives, we reviewed Corps documents, including annual O&M user fee letters, 5-year O&M cost estimate letters provided to users, actual water storage agreements between M&I users and the Corps, model water storage agreements, and other supplemental information prepared for M&I users. We interviewed Corps officials, including headquarters, division, and district offices. We also interviewed or obtained written response from the 14 M&I water users selected in our nongeneralizable sample. This enabled us to gather perspectives from those directly involved in those specific agreements, including utility companies and city and state governments.

To examine the extent to which the Corps has managed its annual O&M user fee process consistent with key practices for federal user fees, we compared Corps user fee processes we learned about from interviews with key considerations and practices for setting user fees and sharing information with users about fees listed in GAO’s design guide for federal user fees.[15] To examine how the Corps developed the 5-year O&M cost estimates as required by law, we compared the estimate provisions contained in the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 with Corps documentation, such as the Corps’ associated 2015 implementation guidance and estimates provided to M&I users.

We conducted this performance audit from December 2023 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The Corps’ Civil Works Program

Located within the Department of Defense, the Corps has both military and non-military missions, such as its civil works program. The Corps’ civil works program is responsible for water resources projects and is organized into three tiers: a national headquarters in Washington, D.C.; eight regional divisions that were generally established according to watershed boundaries; and 39 districts nationwide. The Corps headquarters primarily develops the policies and guidance that the agency’s divisions and districts carry out as part of their oversight responsibilities of the water projects under the Corps’ purview. The Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, appointed by the President, establishes the policy direction for the civil works program. The Chief of Engineers, a military officer, who is also the Commanding General of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, oversees the Corps’ civil works operations and reports on civil works matters to the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works. The eight divisions, commanded by military officers, coordinate civil works projects in the districts within their respective divisions. Corps districts, also commanded by military officers, are responsible for planning, engineering, constructing, and managing water resources infrastructure projects, such as reservoirs, in their districts.

The Corps’ civil works program has three primary mission areas: commercial navigation, flood and storm damage reduction, and aquatic ecosystem restoration.[16] However, the Corps also performs other functions, such as facilitating emergency management and recreation. To manage both its primary mission areas and other functions, the Corps established multiple business lines, that provide a management and budget development framework. In fiscal year 2024, the Water Storage for Water Supply Business Line received approximately $46 million, or about 0.5 percent, of the Corps’ civil works annual appropriations, according to agency documentation.

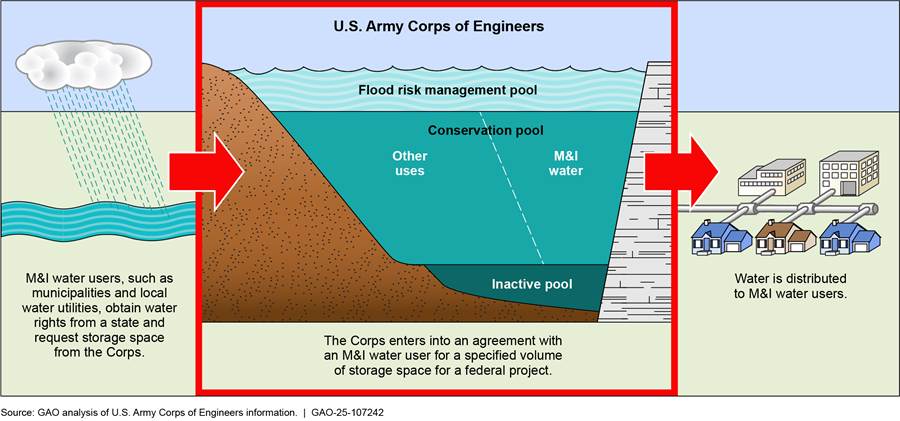

The Corps’ Water Storage Role and Authorities

The Corps provides M&I water storage but does not have a role in acquiring or securing the rights for water that users store at Corps’ projects. Water users must secure the necessary water rights.[17] The Corps also does not have a substantial role in the distribution of stored water, which is generally the responsibility of water users. The Corps enters into agreements with M&I water users, such as states or local water utilities, for water storage within Corps-managed multi-purpose projects, such as reservoirs that typically consist of three water storage pools for flood risk management, conservation, and inactive purposes (see fig. 1). The Corps grants M&I users (as well as other specific users, such as utilities that generate hydroelectric power) storage in the reservoir’s conservation pool.[18]

These agreements may be either (1) an originally authorized agreement for water supply that was included in storage plans prior to the construction of the reservoir or (2) a reallocation agreement, where storage at existing projects is reassigned from one use, such as hydropower generation, to use for M&I water supply. As we reported in 2017, since the 1990s construction of new projects has slowed significantly, resulting in fewer originally authorized agreements, and the Corps has increasingly entered into reallocation agreements to provide M&I water storage.[19]

Notes: The flood risk management pool is normally kept empty to permit runoff storage during periods of high inflow. The conservation pool can consist of dedicated storage for one or more of the following purposes: hydropower, navigation, M&I water storage, water quality, or irrigation. The inactive pool is normally set aside for a specific hydropower purpose and to store expected levels of sediment.

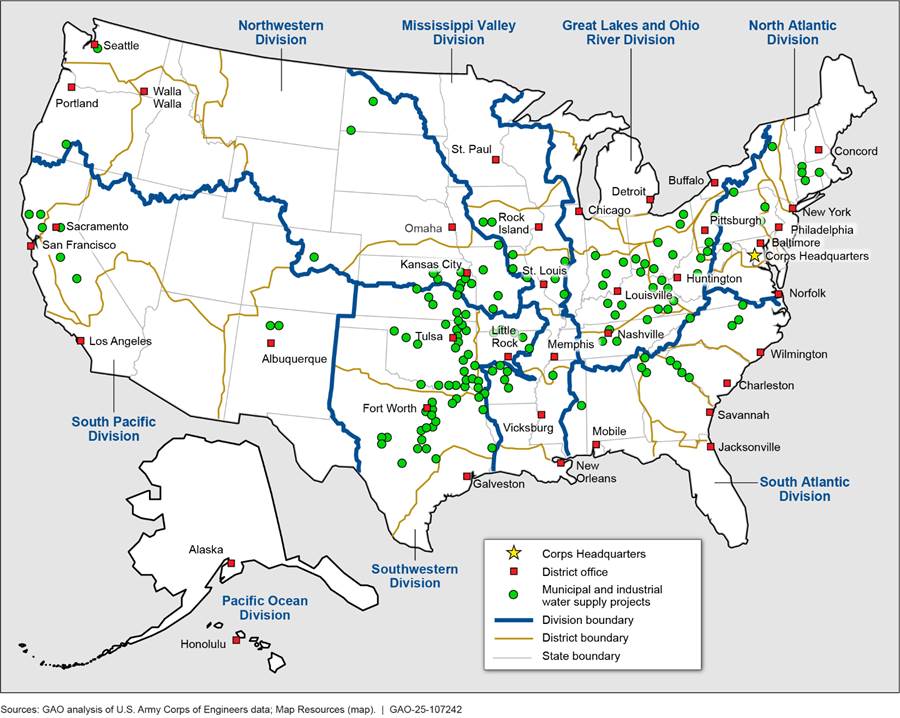

According to our analysis of agency data provided in March 2024, the majority of M&I water storage is concentrated in the Corps’ Southwestern Division, which contains almost 64 percent of the Corps’ water supply storage agreements and about 61 percent of storage volume (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Location of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Projects with Municipal and Industrial Water Storage

Key statutes that establish the Corps’ water storage authorities are as follows:

· Water Supply Act of 1958. According to Corps documentation, the Corps views this statute as the primary vehicle for its involvement in water supply storage as it authorizes the agency to provide M&I water storage at federal projects owned and operated by the Corps to water users on a reimbursable basis. The act authorizes the Corps to include M&I water storage at any reservoir project for current or future needs.[20]

· Public Law 88-140 of 1963. Generally extends to water users the right to use the storage for the physical life of the project subject to repayment of costs.[21]

· Water Resources Development Act of 1986. Modifies the repayment requirements for water users at Corps projects, such as by requiring that O&M costs be reimbursed annually.[22] See figure 3 for examples of O&M activities.

· Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014. Requires Corps districts to provide water users with a 5-year estimate of O&M costs.[23]

Figure 3: Examples of Operations and Maintenance Activities at U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Reservoirs

Key Considerations and Practices for Federal User Fees

The Corps’ O&M fees are a type of federal user fee. A federal user fee is a charge assessed by a federal agency against a party that directly benefits from a government program or activity. Other examples of federal user fees are food inspection fees and fees to enter a national park.

GAO’s design guide for federal user fees states that user fees can be designed to reduce the burden on taxpayers.[24] That is, user fees can finance the portions of activities that provide benefits to certain groups of users—for example, visitors to national parks—above and beyond what is normally provided to the public. The guide says that, by charging the costs of those programs or activities to beneficiaries, user fees can also promote economic efficiency, equity, and adequacy of revenue to cover costs.

To achieve their goals, user fees must be well designed and implemented. GAO’s design guide for federal user fees describes key considerations for designing and implementing fees and the effects of these considerations in terms of economic efficiency, equity, and other factors. In particular, the guide describes practices that federal agencies should consider and follow when setting, collecting, using, and reviewing fees. The guide also refers to other federal government guidance documents, including from the Office of Management and Budget, that provide direction to federal agencies in designing and managing fees. The guide identifies the following key practices for setting them and sharing information on fees that apply to the Corps’ management of O&M user fees:

· Under the beneficiary-pays principle, charge those who use and benefit from the good or service covered by the fee.

· Establish mechanisms to help ensure the fee will cover the intended share of costs over time.

· Establish specific fees for individual users that reliably account for the total costs of providing the service.

· Reliably account for the total costs of providing the service by determining which activities and costs should be included and which should not.

·

Share relevant analysis and information with users to help assure

them that the fees are set fairly and accurately.

The Corps Follows Key Practices for Setting Annual O&M Water Storage User Fees but Could Better Share Information with Users

The Corps district offices we spoke with followed many key practices for setting annual O&M user fees. For example, the Corps reliably accounts for the total costs of providing the service and establishing user specific fees. However, these district offices did not follow a key practice related to sharing information with users about fees. Specifically, the Corps provided users with limited information beyond the fee amount, which multiple users told us hindered their ability to understand and review the fee, and the Corps provided limited opportunities to discuss the fee.

Corps Districts We Spoke with Followed Many Key Practices for Setting Water Storage User Fees

Corps district offices we spoke with applied the following four key practices from GAO’s user fee design guide for federal user fees when setting annual O&M user fees for M&I water users:

· Charge those who use and benefit from the good or service covered by the user fee. All 14 agreements in our nongeneralizable sample contain provisions requiring the user to reimburse the federal government for certain O&M costs. In summer 2024, we asked Corps districts to provide recent O&M fee documentation and districts provided such documentation for the 14 agreements in our nongeneralizable sample. The extent to which user fees fund a program should generally reflect the nature of its beneficiaries, according to GAO’s design guide for federal user fees.[25] Thus, the first step for setting fees is to consider the extent to which a program benefits users, the general public, or both. The design guide describes the “beneficiary-pays principle,” which states that if a program benefits both the general public (such as with flood risk management) and direct users (such as M&I water storage), it should be funded in part by general revenues and in part by fees. This promotes equity because the beneficiaries of a service pay for the cost of providing the service they benefit from. This is the case for Corps reservoirs with M&I water storage since all reservoir related O&M costs are initially funded through the federal appropriations process (general revenues), but M&I users are required to reimburse the government for their portion of these costs (user fees).

· Establish mechanisms to help ensure the fee will cover the intended share of costs over time. Each of the 14 agreements in our nongeneralizable sample lists a specific O&M reimbursement percentage, which is aligned with Office of Management and Budget guidance for agencies to set fees in percentage terms to help ensure they keep pace with rising costs.[26] In addition, all 14 agreements state that such reimbursements must occur on an annual basis and do not contain an end date for such reimbursements, meaning the user must make annual payments for as long as the agreement is in force. Fee collections should be sufficient to cover the intended portion of program costs over time, according to the GAO design guide for federal user fees.[27]

· Establish user-specific fees. Each of the 14 agreements in our nongeneralizable sample, which were signed between 1953 and 2013, contains an O&M reimbursement percentage that is unique to that user. In 1998, the Corps issued a standardized water storage agreement outlining a methodology for calculating a user’s O&M reimbursement percentage. The Corps was expected to use this model agreement, with minor modifications during negotiations, with any significant deviations requiring headquarters review, according to agency documentation. In 2007, the Corps replaced the 1998 model agreement with two separate model agreements: one for an originally authorized agreement and another for a reallocated agreement. Each 2007 model agreement introduced a distinct methodology for calculating the O&M reimbursement percentage.

Our nongeneralizable sample includes no agreements signed from 1998 through 2007. However, it does contain three originally authorized agreements signed after 2007, all of which adhere to the O&M reimbursement methodology outlined in the 2007 model agreement. All other things being equal, user-specific fees (as opposed to a systemwide fee) promote equity and economic efficiency because the amount of the fee is closely aligned with the cost of the service, according to the GAO design guide for federal user fees.[28]

· Reliably account for the total costs of providing the service. All 10 Corps districts included in our nongeneralizable sample use the same general two-step process to identify the total cost of providing the service. First, district officials query the Corps’ financial management database to identify the total O&M-related costs that were incurred at the reservoir during each agreement’s billing period. Second, Corps district officials organize these costs by the agency’s internal work category budget codes and conduct a line-by-line review to determine if each cost should be included or excluded from the user fee. O&M costs that are included are those that are considered “joint costs” (e.g., support two or more project purposes, such as flood risk management and M&I water storage) as well as those costs specifically related to the M&I water storage purpose, such as infrastructure that controls the diversion or withdrawal of the stored water.

O&M costs that can be excluded are either explicitly listed in the agreement (such as those for a recreation purpose) or identified by Corps district officials during their line-by-line review as being specific to a single purpose (such as those for an environmental stewardship purpose) other than M&I water supply storage. Therefore, to generate the actual annual O&M fee an M&I user receives, the Corps identifies all O&M costs, subtracts costs that are excluded, and applies the O&M reimbursement percentage listed in the agreement to the remaining total. If a fee is to recover the costs associated with a portion of an agency service, it is critical that agencies record, accumulate, and analyze timely and reliable data relating to those costs, consistent with applicable accounting standards, according to GAO’s design guide for federal user fees.[29]

Corps Districts We Spoke with Did Not Follow the Key Practice of Communicating about Water User Fees

The 10 Corps district offices we spoke with communicated limited information to help users understand their annual O&M fees, which does not align with a key practice to share relevant analyses and information with users to help assure them that fees are set fairly and accurately.[30] In addition, the Corps offered few opportunities for users to discuss the fees, which prior GAO work has shown contributes to ineffective communication that can increase users’ misunderstandings about how fees work and what activities they may fund.[31]

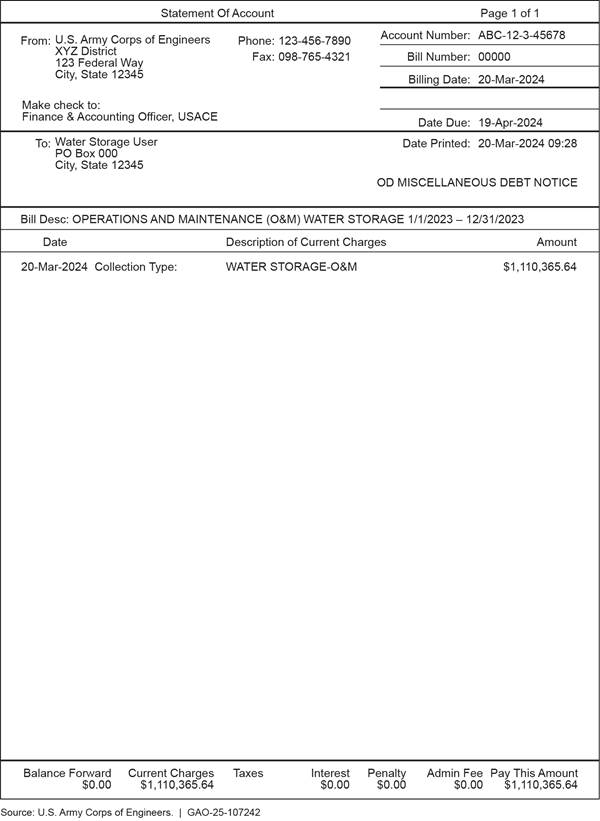

Regarding limited information, two of the 10 Corps districts we spoke with did not provide users with any supplemental information beyond the fee amount. In short, these users received a fee amount with no further details. (See fig. 4 for an example of the information contained in a fee notification.) One user from these two districts told us that the Corps district had previously provided supplemental fee information in annual fee notifications but had stopped doing so a few years ago. This user was unsure why the Corps district office had stopped providing such information but said it would be useful if the information were provided again as it improved transparency for the user and provided a basis upon which to examine the accuracy of the fee.

Another user from these two districts discussed above said that they request supplemental fee information on a regular basis from the Corps district office to help them better understand their bills. In particular, the user started to request supplemental information from the Corps district office about 10 years ago because the O&M fee had increased in one year from about $325,000 to about $700,000. The user’s board of directors expressed concerns about this increase and asked the user to review the fee, according to the user. The user told us that the Corps district office has been generally responsive to their request for supplemental information and that such information had allowed them to better understand the fees and confirm the fee’s accuracy to the board of directors.

Figure 4: Example of an Annual Operations and Maintenance Fee Notification by a Corps District Sent to a User, Without Supplemental Fee Information

Note: We redacted this figure, deleting user-specific information to address potential privacy concerns. Although this figure replicates the actual annual operations and maintenance fee notification sent by a Corps district, the user told us that the Corps district office has been generally responsive to the user’s request for supplemental information and that such information allowed the user to better understand the fee.

The eight other Corps districts in our nongeneralizable sample provided users with some level of supplemental fee information, such as a single-fee calculation, a short table that summarized costs by the Corps’ internal work category budget codes, and multiple fee calculations supported by an itemized cost list from the Corps’ financial management database. One user who received a single-fee calculation told us that this level of detail did not describe what specific O&M activities the user was paying for, creating an information gap that made the user an uninformed customer. In addition, a user who received a short table summarizing costs by the Corps’ internal work category budget codes told us that the information was presented in very broad categories and provided no details on specific O&M activities or a good understanding of what user fees paid for.

A user in one of the districts that provides multiple fee calculations supported by the itemized cost list told us that it is of limited usefulness because there are no specific details on the number, type and scope of actual work activities performed. However, a user from another district that provides multiple fee calculations supported by the itemized cost list described a situation where such supplemental information was helpful in one instance to remove an erroneous charge from the user’s bill. The user said that a few years ago the user had identified a $250,000 cost related to solar panel installation at the reservoir’s campground, which is a recreation cost that should have been excluded from the user’s fee. The user said this issue was brought to the Corps district office’s attention and the cost was removed from the user’s fee.

When asked for any suggestions to improve the supplemental fee information provided by the Corps, five of the 14 users across the 10 Corps districts we spoke with said that the agency could detail and describe in plain language the key work activities that collectively account for a significant portion of the fee. These users said that having information on the fee’s key cost drivers would be especially useful to both understand the fee and to be able to explain the fee amount to their board of directors or management. In addition, two of the 14 users said that the Corps could detail and describe in plain language what O&M activities have changed year over year since such changes causes annual fee amounts to vary. The type and cost of annual O&M work conducted at the reservoir can vary for multiple reasons, such as changes in federal funding levels, the need to conduct periodic inspections or surveys, and impacts from severe weather events, according to Corps officials.

Opportunities for users to discuss fees with the Corps were limited, as Corps officials at nine of the 10 districts we spoke with said they did not dedicate user forums to this purpose. Officials in these nine districts said that user fee issues can be discussed during general coordination meetings between the Corps and users and that district officials are available to answer users’ billing questions via phone or email.[32] However, two users described to us experiences with initiating phone or email communications with the Corps that did not result in substantive opportunities for discussion. In one instance, a user told us they had to reach out to Corps district officials many times over multiple years to request an annual invoice and then had to resend payment when the Corps lost the user’s check. The user also told us that the Corps district’s explanation of why one year’s fee was higher than prior years lacked sufficient detail. In another instance at a different Corps district, a user requested additional details on their fee but was told by an agency official that the user would need to complete a Freedom of Information Act request to get the information.

However, one district we spoke with proactively provides an opportunity for its user to discuss the annual fee. Specifically, this district publishes an annual report and organizes an annual meeting with the user where the district discusses the annual report and the annual fee.[33] This user told us that the annual meeting provides an important opportunity for back-and-forth discussions and contributes to the good working relationship they have with the Corps.

Districts do not always provide users with detailed information and meaningful opportunities for discussion regarding the activities and costs associated with annual O&M fees because the agency lacks both agencywide and district specific policies requiring them to do so. The Corps has a 1998 handbook guiding the overall planning and management of the water supply storage program, but the handbook contains few details related to the annual O&M fee process and no details about what information should be shared with users during the fee review process.[34] None of the 10 Corps districts we spoke with could identify an official Corps policy that included specific, detailed actions for administering the annual O&M fee, including what information should be shared with users. One of the 10 districts we spoke with did develop its own standard operating procedure that covered the fee process, but that procedure did not provide information related to how such fees should be reviewed by the users. Instead, officials at the 10 Corps districts we spoke with said that they share fee information with users on the basis of longstanding practices in their specific district. However, the rationale behind the annual O&M fee has not been fully transparent to some users we spoke with. If the Corps provided more complete information and opportunities for discussion, users would have greater transparency into the overall fee amount and the associated work activities.

Corps Districts Did Not Provide All Users with the Required 5-Year Cost Estimates, and Estimates That Were Provided Were Not Prepared in a Consistent Manner

Of the 10 Corps districts we spoke with, five did not provide M&I users with the legally required 5-year O&M cost estimates and do not have an oversight mechanism to ensure estimates are provided. The five districts that did prepare the estimates each used their own methods, leading to inconsistencies across the districts. While M&I users value receiving estimates, three users shared challenges they have experienced with them and identified steps the Corps could take to improve the usefulness of the estimates.

The Corps Did Not Provide All Users with Required 5-Year O&M Cost Estimates and Has No Mechanism to Ensure Users Receive Them

Of the 10 Corps districts we spoke with, five did not provide M&I users with the legally required 5-year O&M cost estimates. By law, the Corps is required to notify M&I users of anticipated O&M activities and their associated costs for the upcoming fiscal year and the following 4 years.[35] District officials are to prepare these estimates annually, and this effort is in addition to the annual O&M fee letter. Many M&I users that receive the estimates told us they review them to be informed about future O&M costs.[36]

Corps headquarters officials told us they were unaware some districts were not providing users estimates per the legal requirement. District officials provided a range of reasons for not providing the estimates. For instance, officials in one district said they believe this requirement is only applicable to new agreements signed after the law was enacted in June 2014, and since no new agreements have been signed since that time, the officials do not believe it is required. In October 2024, Corps headquarters attorneys told us the requirement to prepare a 5-year O&M cost estimate applies to all water storage agreements regardless of their start date. Officials with another district said that they were not aware of this requirement until it was brought to their attention during our review.

The Corps does not have an oversight mechanism to ensure that districts provide annual 5-year O&M cost estimates to M&I users because the Water Supply Storage Business Line is not a primary mission area for the Corps, according to Corps officials. In addition, the 2015 implementation guidance does not include a formal oversight mechanism for ensuring that these estimates are provided. In December 2024, headquarters officials informed us that they plan to develop an oversight mechanism for the estimates but did not provide details or documentation of this effort. Such formal oversight will be important to effectively manage growing M&I water storage demands.

All five of the users we spoke with who did not receive the 5-year estimates said that receiving such estimates would be helpful for planning and budgeting purposes. In addition, two users said they are hopeful that the Corps will begin providing these estimates, and two said they will start to request the estimates. Without ensuring that all users receive the legally required 5-year O&M cost estimates, users may lack essential information needed to effectively plan and administer their water supply storage per the 2015 implementation guidance.

The 5-Year Cost Estimates Provided Were Not Developed in a Consistent Manner

Of the five Corps districts that prepared the required 5-year cost estimates, each did so using their own methods. This approach has resulted in inconsistencies across districts, and it remains unclear whether these district specific approaches produce the best available estimates, as called for by the 2015 implementation guidance. For instance:

· One district calculated its estimates by applying approximately a 2 percent inflation rate to each of the 5 years. Additionally, for each of the 5 years, the district included anticipated future costs, such as spillway repair construction-related costs, to determine the estimated cost for each of the 5 years.

· Another district developed the first year’s estimate by including base activities (i.e., those needed for minimal safe operations) and additional activities that were included in the President’s budget request. However, the estimates for the remaining 4 years only include those base activities multiplied by an inflation rate. For example, the district estimated one user’s O&M cost in the first year to be approximately $190,000, while the estimated cost in each of the following 4 years was approximately $140,000.

· A third district worked with its operations group to review data in the Corps’ project management system to identify scheduled work activities and their associated costs over the entire 5-year period. The estimates include costs that occur at regular intervals such as dam safety risk assessments (every 10 years) and periodic inspections (every 5 years). As such, one user’s estimated O&M costs for the agreement in our nongeneralizable sample is about 21 percent greater in the 2 years where the inspection and assessment activities are scheduled to be conducted compared with the average O&M costs for the other 3 years where such activities are not planned.

Three of the five districts also included additional cost information that all users we spoke with found helpful. Specifically, these districts included costs related to repair, replacement, and rehabilitation work (referred to as “recapitalization costs”). These are infrequent major capital improvements; users are required to pay a portion of these recapitalization costs as stipulated in their water storage agreements with the Corps.[37] Examples of Corps recapitalization projects include inspection and repair of gate systems, dam road maintenance, and riprap overlay. These costs can have significant financial impact on M&I users and including them in the estimates allows users time to prepare for large expenses. While not legally required, including recapitalization costs in the 5-year O&M estimates aligns with the broader goal of keeping users informed about their financial obligations. For example, one district estimated that a user, who has one agreement in our nongeneralizable sample but a total of 11 agreements in the district, would pay over a 5-year period about $7.3 million in O&M costs and about $2.0 million in recapitalization costs, which included repairing a dam road and an outlet channel. This user told us that the district’s inclusion of the recapitalization costs in the 5-year estimates was appreciated and increased the user’s knowledge for budgeting purposes.

While users value receiving estimates, they also shared challenges they have experienced with the estimates and identified steps the Corps could take to improve the usefulness of the estimates. For example:

· One user told us their organization uses the estimate provided by the Corps as a starting point and typically budgets higher than what is estimated from the Corps. This is because their organization had been surprised by an unexpected O&M expense in the past. They now add $50,000 to each future estimate provided by the Corps. This is an effort to create a financial buffer and prevent surprises.

· Another user said it would be more useful if the Corps provided an “all-in” cost estimate. That is, in addition to O&M cost estimates provided to the user, the Corps could consider notifying the user of recapitalization costs they might be responsible for. That user uses their own modeling tool to estimate an all-in cost that includes an inflation factor.

· A third user told us they would find it more beneficial if their 5-year O&M cost estimates from the district included specific planned or potential future O&M project cost estimates for years 2 through 5. The user said that inclusion of these future projects would be more helpful to their organization’s planning efforts.

Corps districts are implementing their own methodologies for preparing 5-year estimates because Corps headquarters has not yet developed agency-wide estimating instructions, despite their plans to do so. Headquarters officials said they have relied on district officials for information related to preparation of the estimates. The 2015 implementation guidance states that the Water Storage for Water Supply Business Line will serve as the proponent for developing and communicating best practices in providing these estimates.

In December 2024, headquarters officials told us that they would develop additional procedures to improve the consistent implementation of the 5-year O&M cost estimating instructions. Such estimating instructions may enable the districts to provide users with the best-available estimates, as called for in the 2015 implementation guidance. In addition, these procedures will guide districts on using contract-specific and expense data, incorporating best practices, and ensuring timely notifications to M&I users, according to Corps officials. Corps-wide procedures are expected to be available by December 2025, according to officials. However, officials did not provide documentation of this effort, such as a written plan with key milestones.

Conclusions

The Corps collects millions of dollars annually in O&M fees from M&I users to support activities such as dam safety inspections, concrete repairs, and mowing contracts. With more than 400 existing water storage agreements and a growing demand for reallocation agreements, the Corps faces increasing responsibilities in managing these fees. GAO’s design guide on federal user fees outlines key considerations and practices for managing federal user fees effectively. Although the Corps districts generally align their O&M fee setting practices with these guidelines, variations exist on the type of supplemental documentation provided to users. These inconsistencies are compounded by limited opportunities for user engagement and limited communication to discuss the fees. Without a clear process to ensure consistent and transparent communication about fees, the Corps risks users misunderstanding the basis for fees and challenges related to fee management—particularly as water storage demands rise.

By law, the Corps is required to notify M&I users of anticipated O&M activities and their associated costs for the upcoming fiscal year and the following 4 years.[38] However, the Corps does not currently have an oversight mechanism to ensure estimates are provided. Further, the Corps has not established estimating instructions as called for in its own 2015 guidance. The absence of Corps-wide direction, combined with the absence of an oversight mechanism to ensure timely delivery of these estimates has resulted in inconsistent practices across districts, leaving some users without sufficient information—in some cases, none at all—to plan and budget for future O&M costs. For example, some districts we spoke with take an additional step in preparing their estimates by also including recapitalization costs (infrequent major capital improvements). Although not legally required, this approach aligns with the broader goal of keeping users informed about their financial obligations. In contrast, other districts we spoke with did not provide users with sufficient information to effectively plan or budget for future O&M costs. The Corps has yet to formalize their plans to address these gaps.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to the Department of Defense:

The Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works should ensure the Chief of Engineers and Commanding General of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers develop a policy to help ensure effective communication of annual O&M fees to users. Such a policy could include provisions providing users information that explains, in plain language, what activities the fee pays for as well as providing users with a specific opportunity to discuss the fee. (Recommendation 1)

The Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works should ensure the Chief of Engineers and Commanding General of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers develop and implements an oversight mechanism to ensure that all non-federal users receive the legally required 5-year O&M cost estimates each year. (Recommendation 2)

The Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works should ensure the Chief of Engineers and Commanding General of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers provide estimating instructions for the 5-year O&M cost estimates and consider including recapitalization costs in those estimates. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report for review and comment to the Department of Defense. In its written comments, reprinted in appendix I, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works agreed with all three of our recommendations and described planned actions to implement them. The Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, the Chief of Engineers and Commanding General of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at JohnsonCD1@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Cardell D. Johnson

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

GAO Contact

Cardell D. Johnson, JohnsonCD1@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Elizabeth Erdmann (Assistant Director), Sahar Angadjivand (Analyst in Charge), Adrian Apodaca, Patrick Bernard, Alyssia Borsella, Pamela Davidson, William Gerard, Matthew McLaughlin, Zoe Need, and Kathleen Padulchick made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]In addition to the civil works program, the Corps has a military program, which provides, among other things, engineering and construction services to other U.S. government agencies and foreign governments. This report only discusses the civil works program.

[2]The Water Supply Act of 1958 is Title III of the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1958, Pub. L. No. 85-500, tit. III, §§ 301–02, 72 Stat. 297, 319–20 (codified in relevant part as amended at 43 U.S.C. § 390b).

[3]An “acre-foot” of water is the volume of water required to cover 1 acre of land to a depth of 1 foot, which is equivalent to approximately 326,000 gallons.

[4]Pub. L. No. 88-140, 77 Stat. 249 (1963) (codified at 43 U.S.C. §§ 390c–390f). This law generally extended nonfederal interests’ right to use reservoir water supply storage to the physical life of the project, as long as the space is still available, the non-federal interest continues making specified reimbursements, and the right is not otherwise limited by law.

[5]Water Resources Development Act of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-662, § 932(a)(3), 100 Stat. 4082, 4196 – 97 (codified as amended at 43 U.S.C. § 390b(b)).

[6]GAO, Federal User Fees: A Design Guide, GAO‑08‑386SP (Washington, D.C.: May 29, 2008).

[7]GAO, Army Corps of Engineers: Better Data Needed on Water Storage Pricing, GAO‑17‑500 (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 18, 2017).

[8]Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014, Pub. L. No. 113-121, §1046(b), 128 Stat. 1193, 1254 (codified at 43 U.S.C. § 390b-1). These estimates are expressly not to be construed or relied on as the actual amounts. Instead, actual expenditures are subject to congressional appropriations and program execution. Id.

[9]See Department of the Army, Memorandum for Major Subordinate Commands, “Implementation Guidance for Section 1046(b) of the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014—Improving Planning and Administration of Water Supply Storage,” Aug. 7, 2015.

[10]Pub. L. No. 117-263, div. H, tit. LXXXI, § 8236(g), 136 Stat. 2395, 3773 (2022). Division H, title LXXXI of this act is the Water Resources Development Act of 2022.

[11]As part of that review, we identified and removed duplicate water agreements which reduced the number of water storage agreements from 451 to 438.

[12]Specifically,12 agreements came from the top districts because of storage capacity or the number of agreements or O&M users. Three of those districts with either high O&M user fees or large storage capacities were selected because they also had a low number of agreements; this indicated that a small number of agreements were in place to handle large capacities and user fees. Finally, two agreements were selected from districts in which either the user had never received a 5-year O&M cost estimate or because the agreement was relatively new and had a low O&M cost.

[13]The districts in our sample were Baltimore, Fort Worth, Kansas City, Little Rock, Mobile, Sacramento, San Francisco, Tulsa, Vicksburg, and Wilmington.

[14]For example, agreements selected from districts with a large number of agreements ranged in terms of storage capacity and other characteristics.

[15]We excluded key considerations and practices in GAO’s design guide for federal user fees related to (1) collecting the fees and (2) using the fees. We made this decision for multiple reasons, including that the Corps does not have feasible alternatives to the current approaches for fee collection and use. The Corps collects fees after the service is provided, in accordance with the terms of the agreements. Additionally, the fees are returned to the U.S. Treasury as general revenues per legislative requirements. GAO, Federal User Fees: A Design Guide, GAO‑08‑386SP (Washington, D.C.: May 29, 2008).

[16]Section 221 of the Water Resources Development Act of 2020 (WRDA 2020) required the Corps to submit a report to certain congressional committees that analyzes the benefits and consequences of including water supply and water conservation as a primary mission of the Corps, which the agency provided in August 2023. Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, div. AA, § 221, 134 Stat. 1182, 2693 (2020). WRDA 2020 is Division AA of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021. In 2024, bills were introduced in the House of Representatives that would have made water supply a primary Corps mission. H.R. 7065, § 2(a) (118th Cong); H.R. 8812. § 121(a) (118th Cong.). These provisions were not enacted.

[17]Water rights are typically an interest in real property, protected by state and federal laws. Depending on the legal system used in the locale, surface water rights may originate in ownership of riparian lands (i.e., lands that occur along waterways and water bodies) or be acquired by statutorily recognized methods of appropriation.

[18]The flood risk management pool is normally kept empty to permit runoff storage during periods of high inflow. The inactive pool is normally set aside for a specific hydropower purpose and to store expected levels of sediment.

[20]Pub. L. No. 85-500, tit. III, § 301(b), 72 Stat. 297, 319 (codified in relevant part as amended at 43 U.S.C. § 390b(b)).

[21]77 Stat. 249 (codified at 43 U.S.C. §§ 390c–390f).

[22]Pub. L. No. 99-662, § 932(a)(3), 100 Stat. 4082, 4196 – 97 (codified as amended at 43 U.S.C. § 390b(b)).

[23]Pub. L. No. 113-121, §1046(b), 128 Stat. 1193, 1254 (codified at 43 U.S.C. § 390b-1).

[26]Office of Management and Budget, User Charges, OMB Circular No. A-25 Revised (July 1993). Agencies derive their authority to charge fees either from the Independent Offices Appropriation Act of 1952 (IOAA), Pub. L. No. 82-137, 65 Stat. 268 (1951) (codified at 31 U.S.C. § 9701) or other statutory authority. OMB Circular No. A-25 establishes federal guidelines regarding user fees assessed under the authority of the IOAA and other statutes, including the scope and types of activities subject to user fees and the basis upon which the fees are set. While the O&M cost reimbursement charges are not expressly characterized in authorizing legislation as user fees, they represent charges for benefits provided to recipients beyond those accruing to the general public. Thus for the purposes of our evaluation, we consider them to be user fees.

[31]GAO, Federal User Fees: Key Aspects of International Air Passenger Inspection Fees Should Be Addressed Regardless of Whether Fees Are Consolidated, GAO‑07‑1131 (Washington D.C.: Sept. 24, 2007); Federal User Fees: Substantive Reviews Needed to Align Port-Related Fees with the Programs They Support, GAO‑08‑321 (Washington D.C.: Feb. 22, 2008); and Federal User Fees: Fee Design Options and Implications for Managing Revenue Instability, GAO‑13‑820 (Washington D.C.: Sept. 30, 2013).

[32]Six of the 14 users we spoke with told us about various ways in which they communicate with their respective Corps district offices and told us that some of those communications can involve the annual O&M fee. For example, two users said their organizations have regularly scheduled general coordination meetings with the Corps while four users discussed having positive professional working relationships with certain Corps district office officials that resulted in good communication on an ad hoc basis.

[33]A provision in this user’s water storage agreement states that within 30 days after the end of the annual billing period the Corps shall provide the user with a report showing actual annual O&M costs incurred.

[34]U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Water Supply Handbook: A Handbook on Water Supply Planning and Resource Management (Institute for Water Resources, December 1998). According to the handbook, its two primary purposes are to detail the process for providing users with water storage from new and existing Corps reservoir projects and describe how that storage is managed through modeling, water conservation, forecasting and water control systems.

[35]Specifically, the Corps is required, for each water supply feature of a reservoir it manages, to notify the applicable nonfederal interests before each fiscal year of the anticipated operation and maintenance activities for that fiscal year and each of the subsequent 4 fiscal years (including the cost of those activities) for which the nonfederal interests are required to contribute amounts. 43 U.S.C. § 390b-1.

[36]The district’s preparation of these estimates aligns with 2015 implementation guidance to assist with planning and administration of water storage. Department of the Army, Memorandum for Major Subordinate Commands, “Implementation Guidance for Section 1046(b) of the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014—Improving Planning and Administration of Water Supply Storage,” Aug. 7, 2015.

[37]In general, a user can repay these recapitalization costs (i) in increments during construction of the repair, rehabilitation, or replacement, (ii) as a lump sum on completion of that construction, or (iii) at the request of the state or local interest, in increments over a period of not more than 25 years beginning on completion of construction. Water Resources Development Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-263, div. H, tit. LXXXI, § 8389, 136 Stat. 2395, 3831 (codified at 43 U.S.C. § 390b(b)).

[38]43 U.S.C. § 390b-1.