K–12 EDUCATION

DOD NEEDS TO ASSESS ITS CAPACITY TO PROVIDE MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES TO STUDENTS

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107247. For more information, contact Jacqueline M. Nowicki at nowickij@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107247, a report to congressional committees

DOD Needs to Assess Its Capacity to Provide Mental Health Services to Students

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD research has found that military families and children face severe barriers to accessing mental health care, harming family well-being and military readiness. Without proper treatment, children with mental health concerns are at risk of school failure, substance misuse, and suicide.

Senate Report 118-58 includes a provision for GAO to examine mental health services in DODEA schools. This review examines (1) mental health concerns of DODEA students, (2) DODEA’s capacity to implement its new MTSS framework, and (3) the extent to which DOD has assessed how well mental health programs in DODEA schools meet student needs and their collaboration in doing so.

GAO analyzed suicide-related incident data collected by DODEA for school years 2022–23 and 2023–24, the most recent data available. GAO also conducted site visits to 27 schools and eight military treatment facilities on 11 military installations across DODEA’s three regions. GAO interviewed DOD and DODEA officials, reviewed relevant federal laws, policies, and procedures, and assessed DOD actions against policy and relevant federal standards.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations to DOD, including to assess capacity to implement MTSS, to evaluate its programs that provide mental health services in DODEA schools, and assure that these programs collaborate to align their services with student needs. DOD agreed or partially agreed with six recommendations, and disagreed with one, which GAO maintains is valid.

What GAO Found

The Department of Defense Education Activity (DODEA) educated more than 65,000 military-connected pre-K-12 students in 160 schools worldwide in school year 2023–24. GAO found that, like U.S. public school students, DODEA students have experienced increasing mental health concerns in recent years. Per GAO analysis, DODEA schools assessed one in 50 students for suicide risk in each of school years 2022–23 and 2023–24 in response to an identified mental health concern. In all 27 DODEA schools GAO visited worldwide, school leaders described more frequent and acute concerns (see figure).

School psychologists and school counselors told GAO they rarely had time to work with students to prevent crises due to competing responsibilities and heavy administrative workloads, such as testing coordination duties. Such staff are key to successfully implementing DODEA’s Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework—an evidence-based approach to help schools identify and proactively address student needs and build resilience. However, DODEA has not assessed its workforce capacity to implement MTSS with fidelity. Federal workforce planning principles include identifying and addressing human capital needs. Without a workforce plan, DODEA may be unaware of resource gaps that could hinder its success—particularly in light of DOD’s recent directives to optimize its civilian workforce.

DOD has not assured that the three mental health programs it operates in DODEA schools meet student needs. First, none of the programs have been evaluated, contrary to DOD policy. The largest—Military and Family Life Counseling (MFLC)—places nonclinical counselors in nearly every DODEA school. However, school leaders raised concerns about the program, including poor collaboration with school staff and high turnover among counselors. Second, DOD has not assured that these programs provide the right mix of services to meet student needs. School leaders, parents, and military treatment facility staff all told GAO that DODEA students need additional clinical mental health care. Two programs provide clinical services in some DODEA schools. However, these programs are small—embedding one clinician in DODEA schools for every four non-clinical MFLC counselors. Further, DOD has not facilitated collaboration among these programs to assure that they provide the right mix of services to meet DODEA student needs. GAO has reported that collaboration can help agency components address cross-cutting challenges—such as responding to student mental health needs. Collaboration could help DOD better assure that these programs provide the right mix of services to meet DODEA student needs, in line with leading practices and its own goals.

Abbreviations

ADHD Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

ASACS Adolescent Support and Counseling Services

COVID-19 Coronavirus Disease 2019

DOD Department of Defense

DODEA Department of Defense Education Activity

MFLC Military and Family Life Counseling

MTSS Multi-Tiered System of Supports

PTSD Post-traumatic stress disorder

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 14, 2025

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

In 2022, about three-quarters of K–12 public schools nationwide reported that mental health concerns among their students had increased since the COVID-19 pandemic.[1] A 2023 Defense Health Board report found that rates of mental health diagnoses among military-dependent children had increased substantially between 2005 and 2021.[2] The report also noted that military families faced severe barriers to accessing mental health care and that these barriers harm family well-being and military readiness. Without proper treatment, children with mental health concerns are at risk of school failure, substance misuse, and suicide.[3] Early treatment can help children manage their symptoms and support their well-being.[4]

The Department of Defense (DOD) has established policies and procedures to encourage service members and the wider military community to seek mental health care. DOD also offers services like crisis intervention, counseling, and suicide prevention programming. For example, DOD’s website references the toll-free 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, which is available 24/7 to service members, veterans, and their family members.

Similarly, the Department of Defense Education Activity (DODEA) recently introduced a Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework to help its schools better support students’ academic and behavioral needs and enhance students’ well-being and resilience. At the time of our review, DODEA was in the second year of implementing this framework. DODEA school psychologists and counselors also provide certain nonclinical mental health services, such as education, screening, and short-term counseling. Certain DOD-sponsored programs also offer nonclinical and, in some cases, clinical mental health services in some DODEA schools.[5] We have recently reported on DOD’s efforts to address service members’ mental health needs and the challenges that remain.[6] However, less is known about the effectiveness of DOD’s efforts to meet the mental health needs of the more than 65,000 military-connected children who attend DODEA schools in the U.S. and overseas.

Senate Report 118-58 accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to examine issues related to student mental health at DODEA schools. This report examines (1) the types and prevalence of mental health concerns among DODEA students, (2) the extent to which DODEA has assessed its workforce capacity to effectively implement its new MTSS framework, and (3) the extent to which DOD has assessed how well DOD-sponsored school-based mental health services meet the needs of DODEA students and schools and whether they are collaborating to do so.

To address each of our research questions, we interviewed DODEA officials in headquarters and conducted site visits to a nongeneralizable sample of 27 schools at 11 military installations across DODEA’s three regions (the Americas, Europe, and the Pacific).[7] We selected these installations and schools for geographic, military service, and grade-level variation.[8] We held interviews with school leaders (principals and assistant principals), student support staff (school psychologists, school counselors, and nurses), and available providers in schools with access to onsite DOD-sponsored mental health programs.[9] We also conducted six discussion groups with parents of DODEA students from five of the 11 installations to obtain their perspectives on their children’s mental health concerns and the services available to them. Finally, we met with behavioral and mental health providers from eight military treatment facilities on the installations we visited—and leadership from seven of those military treatment facilities—to learn about the mental health concerns they observed among students and the services these facilities offered.[10] We also reviewed relevant federal laws and agency policies and procedures.

To assess the types and prevalence of mental health concerns facing DODEA students, we analyzed suicide risk assessment data from DODEA’s electronic serious incident reporting system. DODEA student support staff conduct a suicide risk assessment after a student self-harms, expresses suicidal thoughts, or attempts to commit suicide. We analyzed data collected for school years 2022–23 and 2023–24, the most recently completed school years at the time of our review.[11] To gain additional insight into the circumstances that prompted suicide risk assessments, we reviewed narrative responses from a nongeneralizable random sample of about 20 incident reports taken from the 2,928 records included in the dataset we analyzed.[12] We assessed the reliability of these data by interviewing DOD officials, reviewing relevant documentation, and reviewing the data for obvious errors, outliers, and missing information. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable to report on the proportion of students DODEA assessed for suicide risk over this period, and the outcome of those risk assessments.

To determine the extent to which DODEA has assessed its workforce capacity to effectively implement its new MTSS framework, we analyzed agency documentation and interviewed agency officials regarding that framework. We also analyzed school psychologist and school counselor staffing ratio data for school years 2020–21 through 2022–23, the 3 most recently completed school years at the time we obtained the data. We assessed the reliability of these data through steps that included assessing the data for obvious errors, outliers, and missing information. We determined that they were sufficiently reliable to report on the ratio of school psychologists and school counselors to enrolled students. We assessed DODEA’s staffing ratios against relevant professional standards by which DODEA is guided.[13] We assessed its workforce planning efforts against key principles for federal workforce planning and DOD and DODEA personnel policy and guidance.[14]

To determine the extent to which DOD has assessed how well DOD-sponsored school-based mental health services meet the needs of DODEA students and schools, we reviewed program policies, procedures, and staffing data for the three programs that provide mental health services in DODEA schools. These programs are the nonclinical Military Family Life Counseling (MFLC) program, the clinical Adolescent Support and Counseling Services (ASACS) program, and the clinical School Behavioral Health program. We also interviewed Military Community and Family Policy officials who oversee the MFLC program, Army officials who oversee the ASACS program, and Defense Health Agency officials who oversee the School Behavioral Health program. We assessed these DOD components’ program evaluation practices against DOD policy regarding evaluating counseling programs.[15] We also assessed the programs’ efforts to collaborate to meet students’ needs against leading practices for collaboration in the federal government.[16]

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

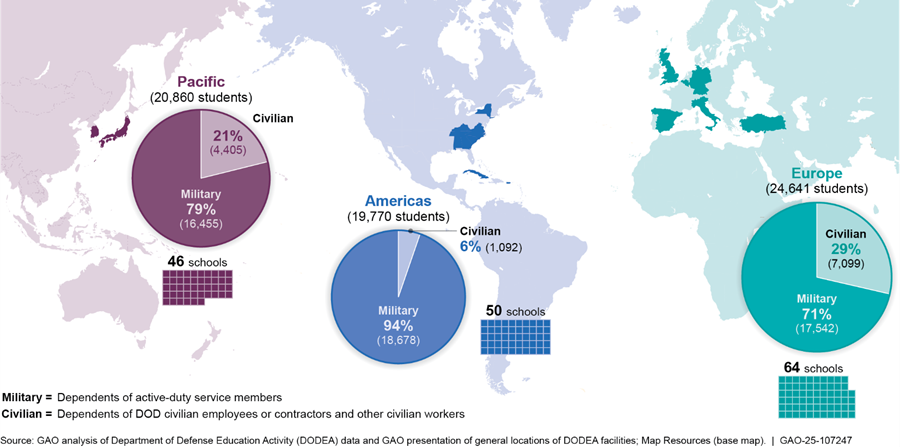

In school year 2023–24, DODEA—which reports to the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness—educated more than 65,000 students of military-connected families across 160 schools (see fig. 1). About 70 percent of these students attended DODEA schools overseas. The majority of DODEA students were children of active-duty service members. However, nearly one in five was the child of a civilian DOD employee or contractor, most of whom were located overseas.

Note: Student enrollment data are as of October 2, 2023. Student enrollment can fluctuate throughout the year.

This figure excludes DODEA’s virtual school, which enrolled 35 students in school year 2023–24.

DODEA’s Framework for Supporting Student Mental Health

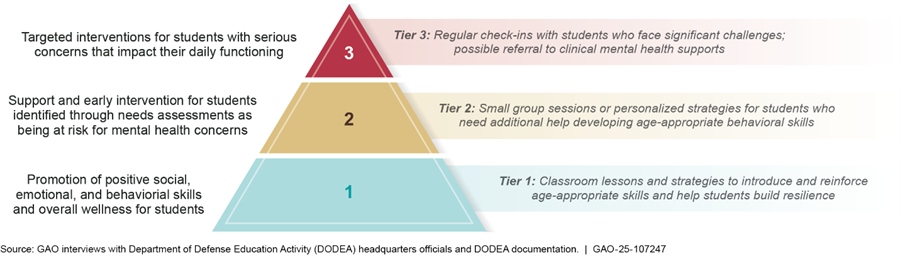

DODEA supports students’ mental health as part of a broader, multi-tiered approach to supporting the educational needs of the whole child. DODEA’s Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework is intended to address students’ academic achievement, resilience, and well-being in a proactive, responsive, and comprehensive manner, before students’ needs escalate to more serious concerns. MTSS frameworks are used in many public schools and are designed to help schools leverage their internal and community resources to better support students.[17] Evidence shows that MTSS can help address students’ mental health concerns (such as depression) while increasing mental well-being and resilience.[18] DODEA’s framework includes four main components, each of which includes activities that support students—including their mental well-being and behavioral needs. These activities are summarized below.

· Core instruction. Schools should provide students with daily, age-appropriate core instruction to help them build resilience. Resilience skills help students adapt to challenges. These skills are particularly important for military-connected children, who may change schools as many as nine times during their K–12 schooling and must also cope with other unique challenges such as parental absences for deployments.

· Intervention systems. Schools should make a continuum of supports available to students, with the supports increasing in intensity in response to their specific needs The first tier of support focuses on universal strategies that promote emotional well-being and resilience for all students through core instruction. Tiers two and three provide additional supports to students with greater needs.

· Team-based leadership. Schools should create teams comprising student support staff (e.g., school psychologists and school counselors), teachers, and administrators who meet regularly to develop strategies to support certain students. For example, they might develop strategies to help a student with a history of off-task behavior to improve their ability to follow classroom direction.

· Data informed decision-making. Schools should collect data to identify which students need support and prompt additional action to help them. For example, these data may drive a school’s decisions to offer classroom lessons on anger management (tier one) or small group sessions to help struggling students build skills (tier two). These data could also identify more urgent needs—for instance, a student experiencing suicidal thoughts—and prompt immediate tier three intervention (see fig. 2).

DODEA Student Support Staff

DODEA school psychologists and school counselors are core student support staff who play a key role in supporting student mental health. For example, per DODEA policy, school psychologists’ and school counselors’ responsibilities include providing nonclinical mental health services to students.[19] These services include nonclinical screenings and assessments; classroom presentations on topics such as managing stress; and short-term, solution-focused nonclinical counseling for individual students.[20] School psychologists and school counselors also help administer DODEA’s suicide prevention program, participate in DODEA student support teams, and respond to a wide variety of student crises, including students’ attempts to harm themselves or others.[21]

DOD-Sponsored Mental Health Programming in DODEA Schools

DOD has three programs that place mental health professionals in DODEA schools to provide mental health services to students (see table 1). The largest of these programs, the MFLC program, provides nonclinical mental health services in nearly every DODEA school and is primarily available to children of active-duty service members.[22] Two smaller programs—ASACS and School Behavioral Health—provide clinical mental health services in some DODEA schools.[23]

Table 1: Mental Health Services Provided by U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) Programs in Some Department of Defense Education Activity (DODEA) Schools

|

|

Military and Family Life Counseling |

Adolescent Support and Counseling Services |

School Behavioral Health Program |

|

Services |

Share information and provide nonclinical counseling support to help with concerns including school adjustment, deployment and separation, and behavioral concerns |

Share information and clinically treat conditions such as anxiety, depression, substance misuse, trauma and stress, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

Clinically diagnose and treat conditions such as anxiety, depression, trauma and stress, and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder; manage medications; and refer patients to other clinical providers |

|

Program office |

Military Community and Family Policy |

U.S. Department of the Army |

Defense Health Agency |

|

Providers in DODEA schools |

206a |

19b |

25c |

|

Grades served |

Prekindergarten to 12 |

6 to 12 |

Prekindergarten to 12 |

|

Students eligible |

Dependents of active-duty service members who do not have a diagnosed mental health disorder and are not experiencing suicidal ideation or self-harm |

Dependents of active-duty service members and civilian workers who attend DODEA schools overseas |

Dependents of active-duty service members and retirees who have access to TRICAREd and dependents of civilian workers who pay out of pocket if space is available |

Source: GAO analysis of data and information from DOD Military Community and Family Policy, Department of the Army, and Defense Health Agency, GAO (icons). | GAO‑25‑107247

aChild and Youth Military and Family Life Counseling staffing data are for school year 2023–24.

bAdolescent Support and Counseling Services staffing data are from March 2025.

cSchool Behavioral Health program staffing data are from January 2023.

dTRICARE is a DOD program that provides health care to active-duty and retired service members and their families.

DOD Clinical Mental Health Services in Medical Treatment Facilities

The Defense Health Agency operates medical treatment facilities on military installations across the world. These facilities prioritize active-duty service members’ physical and mental health needs and make services available to military dependents and to retirees with TRICARE coverage when space is available.[24] DOD civilian employees and their families without TRICARE cannot receive medical care from an installation’s medical treatment facility except in a medical emergency.

Amid Concerns About Increasingly Poor Student Mental Health, DODEA Assessed One in 50 Students for Suicide Risk in Each of the Past 2 School Years

School leaders and student support staff across all 27 DODEA schools we visited told us their students were experiencing unprecedented and increasing levels of mental health concerns. These included higher incidences of suicidal ideation, self-harm, depression, and anxiety compared to past years. Moreover, suicidal behaviors were among the most pressing mental health concerns these school officials observed. Their observations are consistent with reports from K–12 public schools nationwide (see sidebar).

|

Mental Health Concerns Among Public K–12 Students in the U.S. In Spring 2022, more than two-thirds of public schools (69 percent) reported an increase in the percentage of students seeking mental health services from the school since the start of the pandemic. Further, a 2023 nationally representative survey found that four in 10 U.S. high school students reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, two in 10 reported seriously considering suicide, and nearly one in 10 reported that they had attempted suicide. Source: Department of Education and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. | GAO-25-107247 |

Our analysis of data from DODEA’s serious incident reporting system found that in each of the past 2 school years, DODEA staff assessed about one in 50 students for suicide risk in response to an identified concern.[25] Similar to the makeup and distribution of the DODEA student body, we found that:

· 72 percent of students assessed for suicide risk were in DODEA’s Pacific and Europe regions, while 28 percent were in the Americas;

· 72 percent were in elementary or middle school, while 28 percent were in high school; and

· 49 percent were boys and 51 percent were girls.

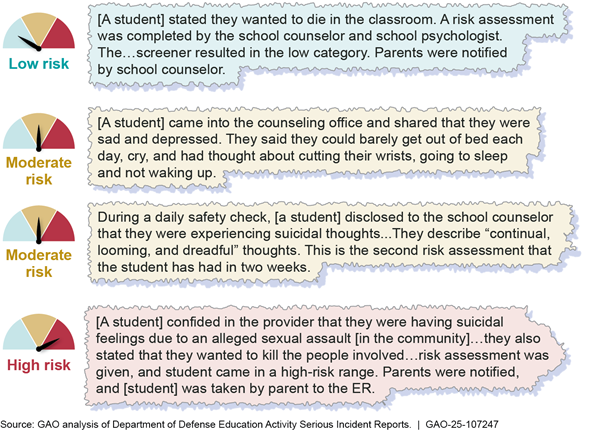

Among the students assessed for suicide risk over this 2-year period, DODEA staff determined that 62 percent were at low risk for suicide, while 32 percent were at moderate risk, and about 6 percent were at high risk. According to DODEA risk-level definitions:

· Students assessed and found to be at low risk for suicide likely have other emotional concerns and do not display severe suicidal behavior.[26] These students may be referred to school counseling or an outside mental health provider.

· Students assessed and found to be at moderate risk for suicide display behavioral signs and risk factors that warrant significant concern about the possibility of suicidal behavior. These students require a complete medical evaluation before returning to school.

· Students assessed and found to be at high risk for suicide appear in immediate danger of making a suicide attempt and require an emergency medical evaluation before returning to school.

Figure 3 shows examples of incidents at DODEA schools that prompted a suicide risk assessment and the results of the assessment.

Figure 3: Examples of Serious Incident Report Narratives Involving Students in DODEA Schools Who Expressed Suicidal Thoughts or Attempted Suicide, School Years 2021–2022, 2022–2023, and 2023–2024

In all 27 DODEA schools we visited, school leaders and student support staff told us that more students had been diagnosed with mental health disorders compared to previous years or had mental health symptoms requiring assessment and classroom intervention. For example, at nearly all of these schools, staff told us their students were experiencing episodes of anxiety (26 of 27) and depression (24 of 27). At some schools we visited (7 of 27), staff told us that their schools’ chronic absenteeism and school refusal behaviors were linked to student mental health concerns, such as anxiety and depression. In a few schools, leaders and student support staff told us some students with anxiety regularly refused to attend school. In two cases shared with us, students would leave school without permission and run home due to their anxiety.

Other commonly cited mental health concerns included recurrent episodes of depression (24 of 27 schools); self-harm behaviors, such as cutting (19 schools); emotional impairments (11 schools); post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or symptoms of exposure to traumatic events (10 schools); and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, 9 schools).

School leaders and student support staff also described the toll that other mental health disorders took on their school community. Some told us they had designated classrooms for emotionally impaired students, who can have episodes of destructive, aggressive, or violent behavior that can be difficult and resource intensive for schools to manage.[27]

School leaders also told us that, in some cases, students exhibiting PTSD symptoms may have been affected by their parent’s service-related PTSD or other untreated mental health conditions. School leaders we spoke with said it can be difficult for parents to secure ADHD evaluations for their children or necessary ADHD medication, especially overseas.[28]

School leaders, student support staff, installation clinical providers, and parents we spoke with described various factors that contributed to the mental health concerns they observed. They also told us that mental health concerns may arise as students grow and develop. Factors not unique to students’ military-connected experiences included:

· excessive and unsupervised phone and social media use,[29]

· bullying and cyberbullying,

· family conflict (e.g., divorce, custody disputes), and

· academic pressures (e.g., testing anxiety, college preparation).

Factors related to students’ military-connected experiences included:

· frequent moves, resulting in geographic isolation from family and friends;

· parental deployments and temporary duty assignments; and

· adjustment to family dynamics during parental absence.

DODEA Has Not Assessed the Capacity of Its Workforce to Implement Its MTSS Framework, While School Leaders Cited Significant Resource Constraints

While DODEA’s Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) framework emphasizes the importance of proactively addressing students’ mental health needs before they escalate to more serious concerns, DODEA has not assessed schools’ capacity to carry out this work. Specifically, DODEA has not developed a workforce plan to support the rollout of this new framework. Workforce plans help government agencies assess the resources they need to achieve their goals and identify strategies for securing additional resources.[30] Further, without a plan, DODEA may be unaware of resource gaps that could hinder its success—particularly in light of DOD’s recent directives to optimize its civilian workforce. [31]

School leaders and student support staff at 24 of the 27 schools we visited told us they rarely had time to provide preventative mental health services called for in DODEA’s MTSS framework. In particular, school psychologists and school counselors told us their time was almost entirely consumed by responding to student crises, supporting special education and accommodations efforts, and completing required administrative tasks. Some told us that responding to a student crisis—for instance, an explosive episode in the classroom or an incident of a student harming themselves—could upend an entire workday and require extensive follow-up work.[32]

According to our analysis of DODEA data, 82 percent of students evaluated for suicide risk in school year 2023–24 were to receive follow-up counseling from their school psychologist, school counselor, or other school staff. Student support staff told us that activities to enhance resilience, such as delivering classroom lessons, holding small group sessions, and working with individual students, frequently fell by the wayside in the wake of a crisis. These types of activities are part of DODEA’s MTSS framework and can help schools proactively address concerns before they escalate. School leaders and student support staff at most schools we visited (22 of 27) said they would like to spend more time on such proactive activities.

School leaders and student support staff also described other factors that negatively affected their ability to provide the core instruction and targeted supports to help students build the resilience skills called for under DODEA’s MTSS framework. School staff from nearly every school we visited (24 of 27) cited DODEA’s high staffing ratios for school psychologists as a major constraint on their capacity. Specifically, DODEA officials told us that their target staffing ratio was one school psychologist for every 900 students (1:900). Our analysis found that the actual ratio in school year 2023–24 was 1:832. However, DODEA policy states that it is guided by the standards set by the National Association of School Psychologists, which sets a target ratio of 1:500.[33] DODEA came closer to meeting this professional standard than the average public K–12 school in the United States.[34]

However, the large majority of DODEA schools shared a school psychologist with at least one other school, including 20 of the 27 schools we visited. As a result, school psychologists we spoke with told us they were rarely able to devote time to students who were not in crisis but needed their attention. For instance, one told us she would not have time to conduct the weekly check-ins she felt were needed for a student who had recently attempted suicide. Another school psychologist who also served as a part-time special education teacher said she faced difficulty meeting the responsibilities of her dual roles.

While the MTSS framework emphasizes the importance of working directly with students, school counselors at nearly all schools we visited (23 out of 27) described heavy administrative workloads that interfered with their capacity to do this. Administrative duties included serving as standardized testing coordinators—a practice strongly discouraged by the American School Counselor Association.[35] DODEA policy states that it is guided by the professional standards established by the American School Counselor Association.[36] School counselors at most schools (22 of 27) told us that these duties—including scheduling tests, ordering supplies, training proctors, and proctoring tests—took significant time away from students. For instance, school counselors from two schools said they were generally unavailable to students in April and May because of their schools’ intensive standardized testing schedules in the last 2 full months of the school year.[37] On the day we visited, one middle school counselor told us, “There are at least 10 or 12 kids we are supposed to check in with today because they’re not well, but I haven’t been able to do it because [my co-counselor is administering a] test and we almost had a fight [between students] in the office this morning.”

DODEA headquarters officials told us they agreed that standardized testing was not a good use of school counselors’ expertise. They further acknowledged that alternative staffing solutions exist that do not rely solely on school counselors. For instance, school leaders may assign standardized testing duties to a group of others in the building or designate it as an extra duty assignment with additional pay for staff who would like to take on the responsibility outside of their normal working hours. However, DODEA policy leaves standardized testing staffing decisions to the school leader at each school and does not explicitly discourage using school counselors to fulfill this role. Without issuing guidance to discourage schools from relying on school counselors as standardized testing coordinators, schools may not be making the best use of their staff’s expertise–especially with regard to supporting DODEA students’ well-being.

DODEA headquarters officials told us that their MTSS framework intends for schools to use existing systems to meet students’ mental health needs proactively when they may be at a lower level of intensity. Officials also said that additional work should not be required to implement this framework. However, school psychologists and school counselors we spoke with universally told us they already faced significant constraints on their ability to achieve these goals. Similarly, parents on four of the five military installations where we held parent discussion groups also told us that school psychologists and school counselors did not have adequate time to meet their children’s needs.

Key principles for workforce planning call for federal agencies to identify current and future human capital needs.[38] Moreover, DOD’s current directives to optimize its civilian workforce underscore the importance of assuring that staffing resources are aligned with agency priorities and needs. Policies that guide DODEA’s school psychological and counseling services state that adequate staffing is necessary for DODEA to provide a full range of services—including direct, proactive services to students.[39] DOD Directive 1100.4 also requires that DODEA staff its schools at the minimum levels necessary to accomplish its mission and performance objectives.[40] Assessing the staff capacity of its schools to implement DODEA’s MTSS framework and subsequently developing a plan to address any identified gaps could help DODEA improve its odds of success. Without these steps, DODEA is vulnerable to resource gaps that could hamper its ability to achieve its goals for the provision of mental health services to its students.

DOD Has Not Evaluated the Mental Health Programs It Offers in DODEA Schools or Assured That They Collaborate to Meet Student Needs

DOD Has Not Evaluated Its Use of Nonclinical MFLC Counselors in DODEA Schools, While School Leaders and Staff Shared Wide-Ranging Concerns

While DOD places nonclinical counselors through the Military and Family Life Counseling (MFLC) program in nearly every DODEA school, DOD’s office of Military Community and Family Policy has not evaluated the program’s use in DODEA schools. According to Military Community and Family Policy officials, Child and Youth Behavioral counselors from the MFLC program (MFLC counselors) have provided nonclinical support and behavioral intervention services to children of active-duty service members in DODEA schools since 2008.[41] Under federal law, all MFLC counselors are required to be licensed mental health care providers, but may only provide non-medical counseling services.[42] According to the MFLC program guide, services include assisting DODEA students and their families with day-to-day stressors, such as communication issues, family dynamics (e.g., divorce), grief and loss, deployment and reunification, and social skills/peer interactions. They may also provide classroom lessons to students on these topics, lead small group discussions, and offer one-on-one nonclinical counseling to children of active-duty service members. According to Military Community and Family Policy officials, MFLC counselors are required to be clinically licensed because such counselors have better training and skills to support students with mental health needs compared to those without clinical licensure.

Leaders and staff from nearly every school we visited (24 of 27) described instances that left them hesitant to refer students to MFLC counselors or unsure of how to incorporate MFLC counselors into their school’s existing efforts to enhance students’ mental well-being. For example, school leaders and student support staff in some schools (10 of 27) told us that MFLC counselors would not disclose how they were supporting the students they counseled or, in some cases, whether they were counseling a particular student at all, because MFLC counseling is designed to be confidential. The MFLC Program Guide states that MFLC counselors may balance their requirement to keep information confidential—except to meet legal obligations or to prevent harm to self or others—with efforts to collaborate with school staff. When asked, Military Community and Family Policy staff told us that MFLC counselors use their discretion when determining whether to share limited information with school leaders and student support staff.

Further, MFLC counselors provide targeted interventions to individual students that align with the third tier of DODEA’s MTSS framework, such as one-on-one counseling. However, the counselors’ job duties do not include participating in other elements of the framework. DODEA headquarters officials told us that they did not have the authority to change the scope of MFLC counselors’ role—for instance, to require them to participate in team-based leadership efforts, such as student support teams. Because MFLC counselors generally do not take part in these collaborative efforts, some school leaders and student support staff we spoke with told us they had difficulty leveraging MFLC counselors’ skills effectively.

Similarly, school leaders and student support staff also expressed frustration that MFLC counselors’ services were not available to many of the students with the greatest need for additional support at school. For example, the MFLC program guide prohibits MFLC counselors from counseling students with diagnosed mental health conditions (e.g., depression or anxiety) on topics related to their diagnosis, even though MFLC counselors are clinically licensed and have the training and skill set to address these needs.[43] And while Military Community and Family Policy officials said that MFLC counselors may work with students who receive special education services, school leaders and student support staff from a few schools we visited (5 of 27) told us their MFLC counselor would not do this.

Leaders and support staff at 20 of 27 schools also expressed concerns about high turnover among the MFLC counselors who were assigned to their schools. MFLC counselors serve one-year terms and may move on to a different assignment after the school year ends.[44] Some school leaders and student support staff said their schools had experienced a high rate of turnover among their MFLC counselors, which interrupted continuity of care and eroded trust with students and other adults who worked in their schools. Staff at 11 of the 27 schools we visited told us that their MFLC counselors usually only stay for a year or two before moving on. In some cases, school leaders said they had worked with MFLC counselors who became valuable additions to the school community during their limited tenure. Others primarily served as lunchroom attendants or recess monitors. One district leader we spoke with described MFLC counselors as “glorified babysitters.”

DOD’s Military Community and Family Policy has not evaluated how it has implemented the MFLC program in DODEA schools, contrary to DOD’s policy to periodically evaluate all counseling programs. While Military Community and Family Policy commissioned a study in 2017 to examine the MFLC program’s effectiveness for adults, it excluded children from the scope of this review because MFLC services for children were programmatically separate from those for adults.[45] Military Community and Family Policy officials told us they had recently assessed the needs of military-connected children who attended schools and other programs with MFLC counselors. Officials stated that this assessment included an online survey of school principals, but they could not provide information on what the survey asked or how many DODEA schools received it. Further, officials told us that findings from the needs assessment could not be reported for DODEA schools specifically.[46]

Even though the MFLC program has not been evaluated in DODEA schools, Military Community and Family Policy officials described the program as highly successful in meeting the needs of DODEA students. Officials also stated that anonymous feedback solicited from school leaders about all MFLC counselors was overwhelmingly positive. However, Military Community and Family Policy officials told us they were unable to isolate feedback provided on MFLC counselors in DODEA schools specifically. Further, anonymous feedback on individual employees is not a substitute for a rigorous evaluation of a program’s performance. These officials also told us they were always available to DODEA school leaders to address any specific concerns about a MFLC counselor in their school. However, DODEA headquarters officials said that, to their knowledge, Military Community and Family Policy had not solicited feedback on the MFLC program at the DODEA school level. While DODEA headquarters officials told us that a staff member attended monthly meetings with representatives of the Military Community and Family Policy office, officials also said that these meetings did not focus specifically on how the MFLC program works in DODEA schools.

DOD policy requires periodic evaluations of its counseling programs.[47] Program evaluations provide agency leaders with evidence to help them determine whether their programs and activities are achieving intended results. Key practices for federal program evaluation activities call for agencies to engage stakeholders in the evaluation process and use the results to inform future actions.[48] Absent an evaluation of how the MFLC program is working in DODEA schools that includes stakeholder input, DOD’s office of Military Community and Family Policy may be unaware of challenges it is able to resolve and opportunities to improve service delivery to students at a time when demand for such services is increasing.

DOD Has Not Evaluated Its Use of Clinical ASACS Counselors and School Behavioral Health Providers in DODEA Schools

Although DOD policy requires periodic evaluations of its counseling programs, DOD has not evaluated its Adolescent Support and Counseling Services (ASACS) and School Behavioral Health programs, both of which have provided on-site clinical services to students at some DODEA schools for decades.[49] In-school clinical mental health services are a common strategy in schools across the country for assuring that school-aged children with identified mental health needs have the support they need to safely remain at school (see sidebar).

|

Federal Data on Mental Health Services in K–12 Public Schools According to Department of Education data, an estimated 38 percent of public schools offered clinical mental health treatment services for students in school year 2021–22. And as of the 2023–24 school year, an estimated 57 percent of public schools that offered mental health services reported partnering with outside practices or programs to provide mental health services to students. Additionally, an estimated 67 percent reported using school or district-employed licensed mental health professionals to provide mental health services to students. Source: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, School Survey on Crime and Safety 2021–22 and School Pulse Panel 2023–24. | GAO-25-107247 |

We visited eight schools across DODEA’s three geographical regions that had access to an on-site clinical provider from the ASACS or School Behavioral Health program at the time of our visit or during the prior year. Leaders and student support staff in each school told us these programs helped their highest-needs students succeed in school. For example, staff from a primary school told us that one high-needs student who received clinical mental health services in school was able to overcome severe separation anxiety, enabling the student to successfully handle being dropped off at school each morning by their parent.

Parents whose children had received services from these clinical providers described similar benefits. One parent said that having access to consistent therapy at school helped their child flourish socially. Another parent described their child, who had previously been disruptive in class, as thriving in the classroom because of the School Behavioral Health program. One parent noted that their child’s ASACS provider was very impactful because of scarce clinical resources in the community. Further, school and program officials told us their ASACS and School Behavioral Health clinicians also provided additional benefits to the school—such as participating in student support teams, providing teachers with strategies to help high-needs students, and stepping in to provide support when students were in crisis.

While school leaders, student support staff, and parents praised the ASACS and School Behavioral Health programs across the three regions we visited, DOD has not evaluated or sought feedback from DODEA on the programs’ effectiveness. In a 2024 review, the Army took an initial step toward program evaluation by assessing its ability to measure ASACS program performance using available data. Through this assessment, it identified data gaps and made recommendations to Army leadership to address them. While Army officials who oversee the ASACS program told us they had not yet completed a formal evaluation of the program, they agreed that one was needed. Officials from the Defense Health Agency said they had not evaluated the School Behavioral Health program since they assumed administrative responsibility for the program from the Army.[50] Instead, officials stated that that they had prioritized developing a new program manual to guide the program’s administration under the Defense Health Agency.

DOD policy requires periodic evaluation of its counseling programs.[51] Key practices for federal program evaluation activities call for agencies to engage stakeholders in the evaluation process and use the results to inform future actions.[52] Program evaluations also provide agency leadership with evidence to help them make policy decisions. Without formally evaluating how well the ASACS and School Behavioral Health programs are working with the input of stakeholders, including DODEA headquarters staff and school leaders, DOD is missing an opportunity to identify potential concerns and develop plans to address them.

DOD Has Not Assured That the Mental Health Services It Offers in DODEA Schools Are Aligned with Student Needs and That Programs Are Collaborating to Do This

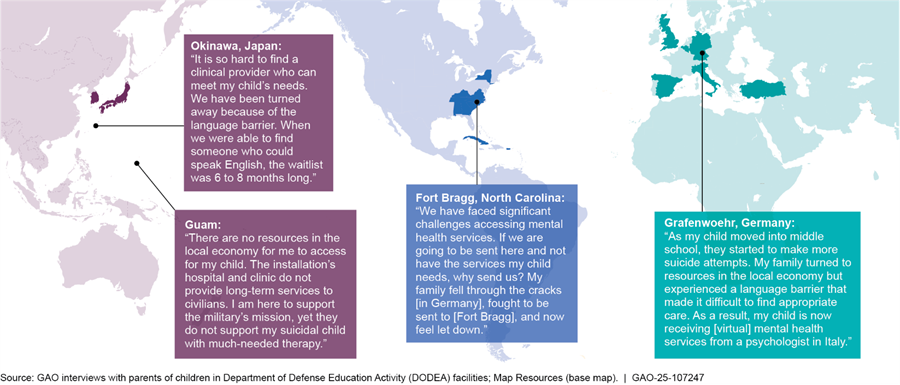

DOD has not assured that its MFLC, ASACS, and School Behavioral Health programs are aligned to provide the right mix of mental health services to meet DODEA student needs. School leaders, military treatment facility staff, and parents we interviewed told us that DODEA students were in critical need of additional clinical resources (see fig. 4). School leaders also told us they would welcome clinical resources embedded in their schools. However, at the time of our review, four times more nonclinical MFLC counselors were embedded in DODEA schools than clinical providers from either the ASACS or School Behavioral Health programs.[53] Further, school leaders and student support staff in nearly every school we visited told us they had trouble using their nonclinical MFLC counselors effectively.

Figure 4: Examples of Challenges DODEA Families Described Regarding Access to Mental Health Services

In 2023, the Defense Health Board called on DOD to eliminate the severe barriers that military families, including children, face in accessing mental health care.[54] It further stated that increasing rates of youth mental health disorders among military families compromised military readiness by reducing the pool of potential future recruits. It is DOD policy to eliminate barriers and provide easy access to a continuum of counseling support to build resilience.[55] The Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness is assigned responsibility for ensuring that DOD components comply with this policy and that they share information.[56]

Despite growing concerns about DODEA student mental health and DOD’s own policy on sharing information about and eliminating barriers to counseling, officials told us no entity facilitates collaboration and information sharing regarding services the MFLC, ASACS, and School Behavioral Health programs provide in DODEA schools. When asked why, School Behavioral Health officials stated that the programs fell under separate authorities, had different missions and priorities, and that none could direct the others to take action.

Instead of formal collaboration to assure that their programs were aligned with DODEA student needs, leaders from the MFLC and ASACS programs said local counselors collaborated with relevant stakeholders to address the individual concerns of specific children. And while School Behavioral Health program officials said they sometimes shared information with other program leads (e.g., at monthly meetings hosted by the office that oversees the MFLC program), DODEA headquarters officials told us that the meetings did not focus on DODEA schools. They also stated that no DOD component had asked them which services DODEA schools needed most.

As we have previously reported, collaboration can help agency components work together to tackle challenges that cut across programs and entities—for instance, addressing rising mental health needs among school-aged children. Given the MFLC, ASACS, and School Behavioral Health programs’ separate administration and distinct missions, effective collaboration could help DOD better assure that it is effectively meeting the mental health needs of students in its own school system. Practices that are known to enhance collaboration include (1) defining common outcomes (e.g., aligning services with needs), (2) identifying and sustaining leadership (e.g., designating a focal point to spearhead collaborative efforts), and (3) including relevant stakeholders (e.g., the programs that provide services and DODEA). Employing such practices could help DOD better assure that it provides the right mix of mental health services to meet DODEA student mental health needs, in line with its own policy.

Conclusions

While DODEA has taken steps to respond to rising student mental health concerns through its MTSS initiative, the success of this initiative largely depends on the capacity of the school-based staff charged with implementing it. School psychologists and school counselors in nearly every school we visited described workload constraints that prevented them from attending to all but the most urgent student needs. However, DODEA has not yet assessed its capacity to implement all aspects of the MTSS initiative. Some workload constraints could be solved by providing guidance to encourage school leaders not to assign standardized testing coordination duties to school counselors, in line with the position of the American School Counselor Association. However, without further action by DODEA to assess its workforce capacity to implement its MTSS framework, the success of its MTSS rollout remains in question.

DOD offers several programs to provide mental health services in some DODEA schools, but the DOD offices responsible for these programs may not have the necessary information they need to assure their efficacy. Thorough evaluations of the MFLC, ASACS, and School Behavioral Health programs could help DOD officials determine how they are meeting the needs of DODEA students and identify opportunities to improve effectiveness. Finally, DOD-sponsored research has called for action to address widely recognized gaps in mental health service availability. However, DOD has not taken steps assure the MFLC, ASACS, and School Behavioral Health programs—which are housed in different components and have distinct purposes—collaborate to align their services to meet DODEA student needs. Without ensuring that it has the right mix of resources to address DODEA students’ mental health needs, DOD may fall short of meeting service member families’ needs, potentially harming mission readiness.

Recommendations

We are making the following seven recommendations to DOD:

The Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness should direct the DODEA Director to develop and disseminate guidance to schools for assigning standardized testing coordination responsibilities to school leaders. This guidance should discourage schools from relying on school counselors as standardized testing coordinators. (Recommendation 1)

The Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness should direct the DODEA Director to assess the capacity of its workforce to provide the continuum of behavioral supports indicated in its MTSS framework. This assessment should consider the capacity of school psychologists and school counselors. (Recommendation 2)

The Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness should direct the DODEA Director to develop a plan based on the results of its workforce assessment to address any identified gaps in workforce capacity that could hinder the success of its MTSS initiative. (Recommendation 3)

The Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness should direct the Director of Military Community Support Programs to evaluate the MFLC program’s use in DODEA schools, seeking feedback from DODEA headquarters staff and school leaders, and develop a plan to address any areas of concern identified through its evaluation. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of the Army should direct the Director of the Directorate of Prevention, Resilience, and Readiness to evaluate the ASACS program’s use in DODEA schools, seeking feedback from DODEA headquarters staff and school leaders, and develop a plan to address any areas of concern identified through its evaluation. (Recommendation 5)

The Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness should direct the Director of the Defense Health Agency to evaluate the School Behavioral Health program’s use in DODEA schools, seeking feedback from DODEA headquarters staff and school leaders, and develop a plan to address any areas of concern identified through its evaluation. (Recommendation 6)

The Secretary of Defense should direct the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness to assure that the ASACS, MFLC, and School Behavioral Health programs collaborate to align their services to meet DODEA student mental health needs. In doing so, and in line with leading practices on federal collaborative efforts, the programs should define common outcomes, identify and sustain leadership for the effort, and involve relevant stakeholders, including DODEA. (Recommendation 7)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. DOD provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. In its formal comments, reproduced in appendix I, DOD concurred with three recommendations, partially concurred with three recommendations, and did not concur with one of our recommendations.

DOD concurred with recommendations 4 and 6 that DOD evaluate its MFLC and School Behavioral Health programs. DOD also concurred with recommendation 7, which recommended the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness foster coordination among the ASACS, MFLC, and School Behavioral Health programs.

DOD partially concurred with recommendation 1, regarding developing and disseminating guidance to schools that discourages them from assigning standardized testing coordination responsibilities to school counselors. DOD stated that it will direct DODEA to develop and disseminate guidance on assigning testing coordination responsibilities in a way that is mindful of school counselors’ primary responsibilities. As stated in the report, encouraging school leaders not to assign standardized testing coordination duties to school counselors, in line with the position of the American School Counselor Association, could help address some of DODEA’s workload capacity issues. We continue to maintain that guidance to explicitly discourage assigning testing responsibilities to school counselors is warranted.

DOD partially concurred with our second recommendation to assess the capacity of its workforce to implement the behavioral supports envisioned in DODEA’s MTSS framework, and in doing so to consider the capacity of school counselors and school psychologists. DOD said it has assessed school-level staffing to ensure responsibilities are appropriately positioned to support the strategic instructional needs of military-connected students, and noted that student support is not limited to school counselors and psychologists. Rather, it involves a comprehensive team of school nurses, school social workers, and other professionals committed to student success. We agree, and note that the recommendation does not preclude taking a broader approach as DOD outlines.

DOD also partially concurred with our third recommendation that DODEA develop a plan based on the results of its workforce assessment to address any identified gaps in workforce capacity that could hinder the success of its MTSS initiative. DOD stated that the MTSS framework is meant to be adaptable to enable DOD to meet the ever-evolving needs of its schools and students. DOD also noted that the next phase of the MTSS rollout will focus on refining roles and responsibilities to ensure optimized resource allocation, and that MTSS requires cycles of continuous assessment. We agree that optimizing resource allocation is critical to the success of MTSS. However, DODEA has not yet assessed its capacity to implement all aspects of the MTSS initiative. We continue to believe that identifying any gaps in workforce capacity and developing a plan to address them will help DODEA align its staffing resources to meet students’ needs and improve the success of its MTSS implementation.

DOD did not concur with recommendation 5 that the Secretary of the Army evaluate the ASACS program’s use in DODEA schools. In its response, DOD stated that, in the context of ongoing work to implement ASACS program guidance, ASACS staff in DODEA schools will collaborate with local DODEA school leaders and counselors for effective collaborative planning, and because this work is ongoing our recommendation is superfluous. We are pleased that the Army recognizes the value of collaboration, and our report describes these efforts. However, as stated in the report, he ASACS program has not been evaluated for effectiveness in DODEA schools, and Army officials agreed that a formal program evaluation was needed. We continue to maintain that an evaluation of the ASACS program is necessary.

Lastly, DOD questioned whether the January 2024–May 2025 dates of our review, as noted in the generally accepted government auditing standards compliance statement, are correct. These are the dates when we started our audit and issued our report, and are therefore correct.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on GAO’s website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at nowickij@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Jacqueline M. Nowicki

Director, Education, Workforce, and Income Security Issues

GAO Contact:

Jacqueline M. Nowicki, nowickij@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments:

In addition to the contact named above, Ellen Phelps Ranen (Assistant Director), Manuel Valverde (Analyst in Charge), Myra Francisco (Analyst in Charge), and Jeanine Navarrete made key contributions to this report. Elizabeth Calderon, Ryan D’Amore, Sherri Doughty, Justin Dunleavy, Serena Lo, Elizabeth Oh, Isaac Pavkovic, Tricia Roy, Jerry Sandau, Meg Sommerfeld, and Sirin Yaemsiri also contributed to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]These concerns included depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. See U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, School Pulse Panel (April 12–25, 2022), https://ies.ed.gov/schoolsurvey/spp/SPP_April_Infographic_Mental_Health_and_Well_Being.pdf.

[2]See Department of Defense, Defense Health Board, Beneficiary Mental Health Access, Defense Health Board Reports (Falls Church, VA: June 28, 2023), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/trecms/pdf/AD1206266.pdf.

[3]See Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Mental Health, Children and Mental Health: Is This Just a Stage?, NIH Publication No. 24-MH-8085, (Bethesda, MD: Revised 2024) https://www.nimh.nih.gov/sites/default/files/documents/health/publications/children-and-mental-health/children-and-mental-health.pdf.

[4]Department of Health and Human Services, Children and Mental Health: Is This Just a Stage?.

[5]Clinical services include diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders. Some clinical mental health providers can offer longer-term therapy and, in some cases, prescribe medication.

[6]For example, see GAO, DOD and VA Health Care: Actions Needed to Better Facilitate Access to Mental Health Services During Military to Civilian Transitions, GAO‑24‑106189 (Washington, D.C.: July 15, 2024); GAO, DOD Assessment Needed to Ensure TRICARE Behavioral Health Coverage Goals Are Being Met, GAO‑24‑106597 (Washington, D.C.: February 6, 2024); and GAO, Suicide Prevention: DOD Should Enhance Oversight, Staffing, Guidance, and Training Affecting Certain Remote Installations, GAO‑22‑105108 (Washington, D.C.: April 28, 2022). We have also reported on the challenges DOD-affiliated civilian workers and their families face in accessing health care, including mental health care, in certain overseas locations. See GAO, Civilian Workforce: DOD Is Implementing Actions to Address Challenges with Accessing Health Care in Japan and Guam, GAO‑25‑107453 (Washington, D.C.: April 3, 2025).

[7]In this report, we used the following quantifiers to characterize how commonly DODEA school leaders and student support staff at the 27 schools we visited shared particular views or experiences: all (27 schools), nearly all (23 to 26 schools), most (14 to 22 schools), some (7 to 13 schools), and a few (3 to 6 schools).

[8]These military installations were Fort Bragg in North Carolina; U.S. Army Garrison Bavaria, Spangdahlem Air Base, U.S. Army Garrison Wiesbaden, and U.S. Naval Support Activity Naples in Europe; and Kadena Air Base, Camp Lester, Camp Foster, Camp McTureous, U.S. Navy Station Military Base, and Andersen Air Force Base in the Pacific.

[9]Specifically, we interviewed Child and Youth Behavioral Military Family Life Counselors (MFLC counselors) in eight schools, Adolescent Support and Counseling Services (ASACS) counselors in five schools, and School Behavioral Health providers in two schools.

[10]For the purposes of this report, statements attributed to “installation clinical providers” includes hospital and clinic behavioral health and mental health staff. We spoke with leadership and installation clinical providers at Spangdahlem Air Base, U.S. Army Garrison Wiesbaden, U.S. Naval Support Activity Naples, Kadena Air Base, Camp Foster, and Naval Base Guam. We also met with installation clinical providers in Fort Bragg.

[11]We excluded data from school year 2021–22 because DODEA had not yet fully implemented its student threat and suicide risk assessment program, and schools may not have consistently conducted or recorded the results of suicide risk assessments during that school year as a result. We also reviewed data reported through DODEA’s Director’s Critical Information Requirement reports, which are filed by DODEA’s regional chief of staff, or regional director. These reports flag certain severe incidents, such as suicide or criminal conduct, that need to be brought to the immediate attention of DODEA’s Director and the DODEA Headquarters chief of staff.

[12]These records covered the 2021–22, 2022–23, and 2023–24 school years.

[13]See National Association of School Psychologists, The Professional Standards of the National Association of School Psychologists (May 2020).

[14]See GAO, Human Capital: Key Principles for Effective Strategic Workforce Planning, GAO‑04‑39 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 11, 2003); Department of Defense Education Activity, School Psychological Services, Manual 2964.4 (Arlington, VA: June 2004) and Department of Defense Education Activity, School Counseling Services, Manual 2964.2 (Arlington, VA: January 2006). Additionally, see Department of Defense, Guidance for Manpower Management, Directive 1100.4 (February 2005).

[15]Department of Defense, Department of Defense Instruction 6490.06 (Arlington, VA: March 31, 2017). Department of Defense Instruction 6490.06 requires periodic evaluations of DOD counseling programs.

[16]GAO, Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2023).

[17]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Promoting Mental Health and Well-Being in Schools: An Action Guide for School and District Leaders, Accessed March 6, 2025, https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/136371.

[18]Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Promoting Mental Health and Well-Being in Schools.

[19]See Department of Defense Education Activity, School Counseling Services Manual, DODEA Manual 2964.2 (Arlington, VA: January 2006). and Department of Defense Education Activity, School Psychological Services Manual, DODEA Manual 2964.4 (Arlington, VA: January 2004).

[20]DODEA policy states that if students need intensive therapy, they should be referred to a clinical mental health provider.

[21]DODEA uses a youth suicide prevention program to teach students how to identify signs of depression and suicide in both themselves and peers. The program’s curriculum includes classroom lessons for students in grades 6–12 on identifying signs of suicide. It also provides materials for school professionals on recognizing at-risk students and taking appropriate follow-up action.

[22]The MFLC program is housed within Military Community Support Programs and falls under the authority of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. In addition to DODEA schools, the MFLC program also embeds services in military child development centers and public schools with a high proportion of military-dependent students. MFLC counselors also provide support in military child and youth programs.

[23]The ASACS program is housed within the Army’s Directorate of Prevention, Resilience, and Readiness. The School Behavioral Health program is housed within the Defense Health Agency and falls under the authority of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. Both the ASACS and School Behavioral Health programs also operate in a limited number of public schools to provide services to children of active-duty service members.

[24]The Defense Health Agency manages TRICARE, which is a health care program for active-duty service members, their eligible family members, and military retirees.

[25]School leaders electronically report all incidents involving suicidal behavior in DODEA’s Serious Incident Reporting system. Staff use a Student Suicide Risk Assessment Tool to assess students who have exhibited signs of self-harm, expressed thoughts of suicide, or have attempted suicide. The tool includes a series of questions about the student’s plans for self-harm or suicide attempt, emotional state, levels of stress, and mental health diagnoses. DODEA officials told us their staff participate in professional learning on completing these assessments. Officials said this training also helps increase practitioners’ skills in identifying, intervening, and providing support for students demonstrating student threat behaviors.

[26]Department of Defense Education Activity Administrative Instruction 5200.01, Student Threat and Suicide Risk Assessment Program.

[27]According to DODEA guidance, emotional impairment is a condition confirmed by clinical evaluation and diagnosis and that, over a long period of time and to a marked degree, adversely affects educational performance. Emotional impairment includes one or more of the following characteristics: (1) inability to learn that cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health factors; (2) inability to build or maintain satisfactory interpersonal relationships with peers and teachers; (3) inappropriate types of behavior or feelings under normal circumstances; (4) a tendency to develop physical symptoms or fears associated with personal or school problems; (5) a general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression.

[28]During our site visits, military treatment facility officials told us some commonly prescribed medications for ADHD can be difficult to secure overseas due to local regulations on their use and production.

[29]DODEA schools have discretion to establish their own cell phone policies during the school day (e.g., prohibiting use entirely or only during class). DODEA students may be disciplined for use that violates school policy. Among U.S. public schools, 76 percent of schools prohibit cell phone use during school hours, according to 2022 Department of Education survey data. As of November 2024, DODEA did not have plans to change its student cell phone use policy.

[30]Key principles for workforce planning include determining the critical skills needed to achieve agency goals, as well as developing strategies to address gaps in the number or alignment of human capital resources. See GAO‑04‑39.

[31]DOD has issued two memos directing its components to submit proposals on opportunities to reduce or eliminate redundant or non-essential functions. See DOD, Initiating the Workforce Acceleration & Recapitalization Initiative, Memorandum for Senior Pentagon Leadership, Commanders of the Combatant Commands, and Defense Agency and DOD Field Activity Directors (March 28, 2025) and DOD, Workforce Acceleration & Recapitalization Initiative Organizational Review, Memorandum to Senior Pentagon Leadership, Commanders of Combatant Commands, and Defense Agency and DOD Field Activity Directors (April 7, 2025).

[32]School officials from one school told us a student in crisis can take up to 10 hours to address, including administering suicide risk assessments and handling required follow-up work. One school counselor said she had recently devoted 2 days to a particularly challenging student crisis. In most instances, school psychologists and school counselors are also responsible for checking in with students at moderate or high risk for suicide once they return to school.

[33]See DODEA, Manual 2946.4, and National Association of School Psychologists, 2020 Professional Standards.

[34]The national staffing ratio for school psychologists in school year 2023–24 was one school psychologist for every 1,065 students, according to the National Association for School Psychologists.

[35]The American School Counselor Association has also identified other common administrative tasks that are often assigned to school counselors, such as scheduling classes and supervising common areas.

[36]See DODEA, Manual 2946.2.

[37]DODEA’s assessment calendar for school year 2023–24 included over 20 different standardized tests.

[38]See GAO‑04‑39. Such principles can also help agencies mitigate human capital challenges, such as the shortage in school psychologists and school counselors.

[39]See DODEA Manuals 2946.4 and 2946.2.

[40]DOD, Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, Guidance for Manpower Management, Directive 1100.4 (February 12, 2005).

[41]The Department of Defense began the MFLC program in 2004 to provide nonclinical mental health services to service members and their families. In response to the needs of military-connected children, DOD created a Child and Youth Behavioral MFLC counselor role in 2007 to support children in locations including schools and child development centers on military installations. According to MFLC program officials, MFLC counselors began working in DODEA schools in Europe through a pilot program in 2008, which was subsequently expanded across nearly all DODEA schools.

[42]See 10 U.S.C. § 1781(d). The term “non-medical counseling services” means mental health care services that are nonclinical, short-term and solution focused, and address topics related to personal growth, development, and positive functioning.

[43]The contracts for MFLC counselors also prohibit counseling students with suicidal thoughts or self-harm behaviors. The MFLC program guide also states that civilian-dependent students may not receive counseling services. However, civilian-dependent students can participate in MFLC counselors’ classroom and group activities as long as dependents of active-duty service members are also participating.

[44]According to the Military Community and Family Policy officials, MFLC counselors have the option to extend their rotation longer than 1 full school year. They also told us that MFLC counselors assigned to DODEA schools stayed for an average of 240 days in school year 2023–24, and that about one-third did not extend their rotation in their school for the following year.

[45]RAND, An Evaluation of U.S. Military Non-Medical Counseling Programs, RAND Corporation (Santa Monica, CA: October 2017).

[46]Military Community and Family Policy officials said that this assessment was part of the first phase of an effort to examine the needs of military-connected children. Officials told us that the findings from this assessment will be published when they receive clearance to do so. According to Military Community and Family Policy officials, feedback from participants who worked with MFLC counselors would be collected during the second phase of this effort. However, officials said they only planned to collect feedback from adults.

[47]See Department of Defense Instruction 6490.06.

[48]See GAO, Evidence-Based Policymaking: Practices to Help Manage and Assess the Results of Federal Efforts, GAO‑23‑105460 (Washington, D.C.: July 2023).

[49]The Army-sponsored ASACS program had embedded 19 mental health clinicians in DODEA schools as of March 2025, according to program officials. The Defense Health Agency-sponsored School Behavioral Health program had 25 clinicians in DODEA schools as of January 2023.

[50]The School Behavioral Health program was originally part of the Department of the Army. In 2019, DOD began its multiyear transition of its health care services from the military departments to the Defense Health Agency’s management and administration. DOD completed this transition in 2022.

[51]See Department of Defense Instruction 6490.06.

[52]See GAO‑23‑105460.

[53]Specifically, the MFLC program embedded 206 nonclinical counselors in nearly all of DODEA’s 160 schools as of the 2023–24 school year, compared to 24 clinical ASACS counselors in the same school year. As of January 2023, the School Behavioral Health program had placed 25 providers in DODEA schools.

[54]See Department of Defense, Defense Health Board, Beneficiary Mental Health Access. The Defense Health Board recommended that DOD prioritize aligning its mental health services with the needs of military families by addressing persistent provider shortages and appointment delays. The Board also recommended that DOD improve the recruitment and retention of providers in high demand locations and prioritize initiatives to meet key staffing requirements.

[55]See Department of Defense Instruction 6490.06.

[56]Department of Defense Instruction 6490.06.