COVID-19 RELIEF

Improved Controls Needed for Referring Likely Fraud in SBA’s Pandemic Loan Programs

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107267. For more information, contact Seto J. Bagdoyan at (202) 512-6722 or bagdoyans@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107267, a report to congressional committees

Improved Controls Needed for Referring Likely Fraud in SBA’s Pandemic Loan Programs

Why GAO Did This Study

SBA distributed over $1 trillion in loans and grants to over 10 million small businesses in 2020-2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through the CARES Act and other laws, Congress provided funding for PPP and COVID-19 EIDL to support small businesses. In June 2020, GAO found that SBA had not yet developed and implemented plans to identify and respond to risks for the PPP to ensure program integrity. GAO reported in May 2023 that SBA moved quickly under challenging circumstances to develop and launch its pandemic relief programs but that some of the relief funds went to those who sought to defraud the government.

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to monitor COVID-19 pandemic relief funds. In this report, GAO examines SBA’s four-step antifraud process by describing (1) how the process for detecting and referring likely fraud cases was designed and implemented for COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP and identifying (2) any control weaknesses in the process for detecting and referring likely fraud cases for COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP.

GAO examined SBA documentation, interviewed SBA officials, and reviewed prior reports by GAO, SBA’s OIG, and SBA’s independent financial statement auditor, and reports by the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that SBA work with its OIG to develop a plan for referring potential or likely fraud for the COVID-19 EIDL program. SBA agreed with the recommendation.

What GAO Found

According to Small Business Administration (SBA) officials, the four-step process for managing fraud risks in its pandemic loan programs generally consisted of the following components for both the Paycheck Protection Plan (PPP) and COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) programs:

· Screening: automated review, sometimes with additional manual components, that compared each application with several public and private databases and checked for internal inconsistencies that indicated data anomalies.

· Data analytics: various data analytic tools to examine data anomalies, sometimes using a type of artificial intelligence called machine learning for the PPP to help identify files with data anomalies in need of review.

· Human-led reviews: manual reviews of files with data anomalies to determine if the file was ineligible or likely fraudulent.

· OIG referrals: referrals of likely fraudulent applications to SBA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG).

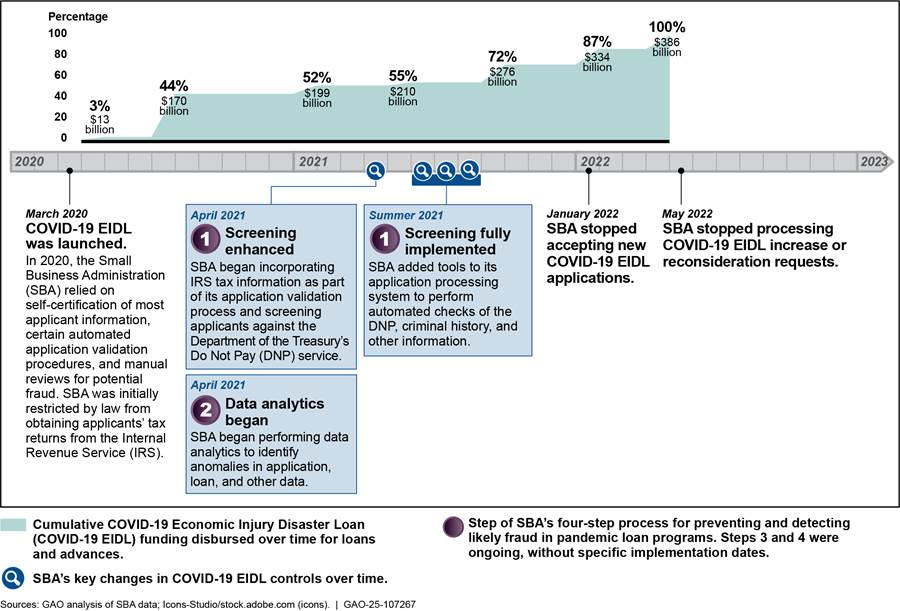

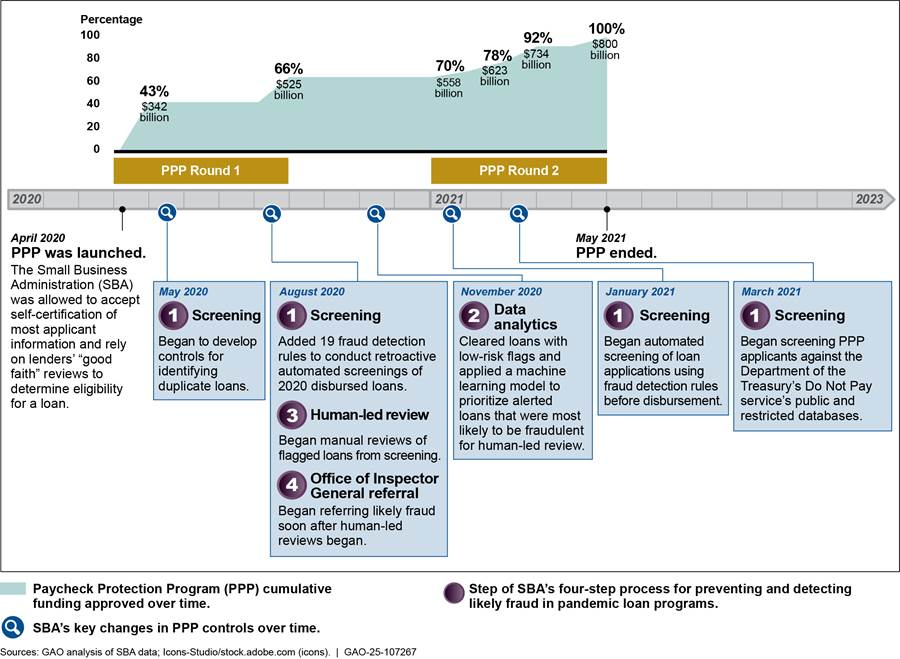

This process and its various steps were introduced at different times for COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP and were implemented iteratively over the course of the pandemic. However, SBA did not implement the process until more than half of the programs’ funding had been approved, thus limiting its impact in preventing fraud. Specifically, for COVID-EIDL, over $210 billion of an eventual $385 billion (or about 55 percent) had already been disbursed before the full process was implemented. For the PPP, over $525 billion of an eventual $800 billion (or about 66 percent) had already been approved.

The four-step process as applied to COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP had weaknesses, as several audit entities, including GAO, SBA’s OIG, and SBA’s independent financial statement auditor, have previously reported. For example, as part of its screening step, SBA compared loan applications against the Treasury’s various Do Not Pay (DNP) databases and public records. A June 2024 SBA OIG report found, however, that SBA awarded and disbursed funds to potentially ineligible entities listed in DNP without sufficient evidence to support the loan decision. In response to this report, SBA agreed, among other things, to review and address those loans and grants with an alert in the file that was not previously addressed. According to SBA’s OIG, the proposed action did not fully meet OIG’s recommendation to review all loans identified as potentially ineligible.

In its work, GAO identified a weakness in SBA’s process for referring cases of likely fraud to its OIG—that is, step four of its four-step process. As part of its referral step for COVID-EIDL, SBA submitted almost 3 million referrals to its OIG. SBA OIG officials told GAO that of these referrals, about 2 million were not actionable because they did not contain enough data elements to allow for further investigation or had quality issues, such as duplicates or incorrect information. Without an effective referral process, the SBA OIG is not able to fully investigate instances of likely fraud and make follow-on referrals to, for example, the Department of Justice for prosecution, as necessary.

Abbreviations

|

AI |

artificial intelligence |

|

BSA |

Bank Secrecy Act |

|

COVID-19-EIDL |

COVID-19 Economic Injury

Disaster Loan |

|

DNP |

Do Not Pay |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

Fraud Risk Framework |

A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs |

|

FRDAA |

Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 |

|

IP |

Internet Protocol |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

NDNH |

National Directory of New Hires |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

PIIA |

Payment Integrity Information Act |

|

PPP |

Payment Protection Program |

|

PRAC |

Pandemic Response Accountability Committee |

|

RRF |

Restaurant Revitalization Fund |

|

SBA |

Small Business Administration |

|

SSA |

Social Security Administration |

|

SSN |

Social Security Number |

|

STAR |

Suspicious Transaction Analysis

and Reporting |

|

SVOG |

Shuttered Venue Operators Grant program |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 24, 2025

Congressional Committees

The Small Business Administration (SBA) made or guaranteed more than $1 trillion in loans and grants to over 10 million small businesses between 2020 and 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, through the CARES Act and other laws, Congress provided funding for the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and the COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) program to support small businesses.[1] In May 2023, we found that SBA moved quickly under challenging circumstances to develop and launch its pandemic relief programs.[2]

As we and others have reported, some of the relief funds went to those who sought to defraud the government. For example, in June 2020 GAO found that SBA had not yet developed and implemented plans to identify and respond to risks for the PPP to ensure program integrity, achieve program effectiveness, and address potential fraud.[3] GAO made corresponding recommendations to complete these tasks and SBA did so by implementing a master review plan that included an approach to use an automated rules-based tool to flag loans with attributes of ineligibility, fraud, or abuse and then manually review them. Similarly, GAO reported in January 2021 that SBA had approved at least 3,000 COVID-19 EIDL loans, totaling about $156 million, to potentially ineligible businesses. Therefore, GAO recommended that SBA conduct portfolio-level analysis to detect potentially ineligible applications.[4] In September 2022, SBA implemented this recommendation by performing analytics tests, among other things, to detect potential fraud in the COVID-19 EIDL program.

The SBA Office of Inspector General (OIG) in June 2023 estimated that SBA disbursed more than $200 billion in potentially fraudulent COVID-19 EIDL and PPP loans, or about 17 percent of the total disbursed funds for these programs.[5] SBA disputed the OIG’s estimate and compiled and published its own estimate, also in June 2023, of around $36 billion in likely fraud. According to SBA, its estimate was informed by the results of a four-step process that had been implemented over the course of the pandemic to detect and refer to the OIG instances of likely fraud in the relief programs.[6]

The CARES Act includes a provision for GAO to monitor the disbursement of SBA and other COVID-19 relief funds. In our May 2023 report, we noted that as fraud schemes emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, SBA adapted its existing fraud risk management approach and added controls to help prevent, detect, and respond to fraud. We also identified, based on selected analyses of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL data, over 3.7 million unique recipients with fraud indicators out of a total of 13.4 million. The presence of such fraud indicators is not proof of fraud but rather can be used to identify potential fraud and assess fraud risks.[7]

We recommended that SBA take various actions to enhance its data analytics program for fraud prevention and detection. In its comments on our report, SBA agreed with both recommendations.[8] However, it took issue with our analyses and suggested that the report omitted discussion of its four-step process, which included the use of automated screening and first-of-their-kind machine learning techniques, to detect likely fraudulent loans and grants and refer them to the SBA’s OIG.[9] The May 2023 report did acknowledge that SBA established processes to detect potential fraud. However, the intent of that audit was not to evaluate those processes and, as a result, the discussion of those processes in our 2023 report was limited.

For this report, we undertook an evaluation of SBA’s four-step process to detect and refer likely fraud in COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP. Specifically, this report (1) describes how SBA’s four-step process for detecting and referring likely fraud was designed and implemented for COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP and (2) identifies weaknesses that existed in SBA’s four-step process for detecting and referring likely fraud to the SBA’s OIG.

To address the first objective, we reviewed previous reports issued by SBA, SBA’s OIG, the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC), GAO, and internal documentation developed by SBA and its PPP loan review contractor that detailed the mechanics and purpose of SBA’s four-step process.[10] In addition, we met with relevant SBA, SBA’s OIG, and PRAC officials, as well as SBA’s loan review contractor who was primarily responsible for developing and implementing the four-step process. We also conducted a site visit to SBA’s primary COVID-19 EIDL processing center in Fort Worth, Texas, to understand how the application process worked during the pandemic and to interview relevant staff members.

To identify any weaknesses in the four-step process, we reviewed the opinions of SBA’s independent financial statement auditor, as well as SBA, SBA’s OIG, GAO, and PRAC reports on PPP and COVID-19 EIDL internal controls that were intended to detect and respond to likely fraud. We also analyzed SBA data on the timing and amount of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL loans disbursed during the pandemic, as compared with when steps in the process were implemented. We used Department of Justice (DOJ) press releases and corresponding court case information to select and review 10 cases that had been adjudicated as PPP or COVID-19 EIDL fraud. We selected 10 cases whereby the fraud occurred after the SBA ‘s four-step antifraud process was in place. We did not perform any analysis to determine how many such cases exist. The cases are not generalizable to all fraud cases or all potential or likely fraud involving the PPP and COVID-19 EIDL.

We sent these 10 cases to SBA for additional information and reviewed its responses to determine how the internal controls did not stop the fraudulent loan or grant in each case. From the identified cases, we selected examples to illustrate how fraud occurred despite the presence of internal controls. We compared federal agency requirements for the use and reporting of artificial intelligence (AI) with SBA’s use of AI in the four-step process.[11] Finally, we met with SBA and SBA OIG officials to better understand SBA’s processes for referring likely fraud to the OIG. We compared those processes with the leading practice in GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework for referrals.[12]

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

SBA’s Pandemic Relief Programs

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected the nation and its economy. Stay-at-home orders, social distancing requirements, and reduced consumer demand early in the pandemic caused both temporary and permanent business closures, particularly among small businesses. To help support small businesses, in March 2020, Congress passed the CARES Act that, among other things,[13] provided funds for the newly created PPP, which was authorized under SBA’s 7(a) small business lending program, and the COVID-19 EIDL program, which was partially based on an existing SBA-administered program providing EIDL disaster loans.[14] Subsequently, in 2022, Congress extended the statute of limitations for criminal and civil enforcement for all forms of PPP and COVID-19 EIDL loan fraud from 5 years to 10 years.[15]

· PPP made funds available to small businesses and nonprofits, referred to collectively as “small businesses,” to help support payroll costs, rent, utilities, and other eligible operating costs during the pandemic. Applicants could apply for first draw loans in PPP Round 1 from April through August of 2020, and first or second draw loans in PPP Round 2 from January through May 2021.[16] PPP loans were made to recipients through participating lenders.[17] PPP loans have a 100 percent SBA guaranty, meaning that SBA agreed to purchase a loan from the lender if the borrower fails to pay. This purchase—called a guaranty purchase—covers a lender’s losses in the event of a borrower default, reducing the risk of lending to small businesses. Existing 7(a) lenders and some other SBA lenders were automatically allowed to participate in the PPP. Lenders who had not previously participated in an SBA program had to apply and be approved before they could participate in the PPP. New lenders were jointly approved by SBA and the Department of the Treasury. Lenders had to apply relevant Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) requirements.[18] SBA required lenders not previously subject to BSA requirements to establish a BSA compliance program and collect additional information for new customers to satisfy BSA requirements.

PPP loans are fully forgivable if certain conditions are met.[19] The borrower can apply through its lender to have the loan forgiven any time on or before the maturity date of the loan if the borrower has used all the loan proceeds for which the borrower is requesting forgiveness.[20] Although the PPP is no longer accepting applications for new loans, some PPP loans are still going through SBA’s loan forgiveness process. A loan forgiveness application must be submitted before the maturity date of the loan, which is either 2 or 5 years from the date the loan originated.

· COVID-19 EIDL program provided funds to small businesses from March 2020 through May 2022 to recover from the economic effects of the pandemic. SBA managed the COVID-19 EIDL program directly, initially led by its Office of Disaster Assistance and later by the Office of Capital Access. The program included two types of funding: loans and grants—also known as advances. Advances—new programmatic elements in COVID-19 EIDL—include EIDL advances (in 2020) and targeted advances and supplemental targeted advances (in 2021) for applicants located in low-income communities and meeting other eligibility requirements. Although the time to apply for COVID-19 EIDL funding has expired, SBA still continues to service the loans. COVID-19 EIDL loans were not eligible for forgiveness.

This loan program is separate from SBA’s traditional EIDL program, which existed before the CARES Act and assists small businesses, small agricultural cooperatives, and most private nonprofit organizations that have suffered economic injury from a disaster.[21] The traditional EIDL program continues to assist small businesses through disasters as they occur.

In March 2021, we added Emergency Loans for Small Business to our High Risk List.[22] The High Risk List highlights federal programs and operations that we have determined are in need of transformation, or that are vulnerable to waste, fraud, abuse, and mismanagement. Combined with the massive volume of loans and expenditures that occurred in a short period of time, this designation was driven by the limited controls in place when SBA launched the programs and the controls that remained at the time of our designation. We were also concerned about SBA’s reliance on self-certification, limited oversight, and sparse documentation of the agency’s oversight plans and documentation for estimating improper payments. Accordingly, in making the designation, we cited concerns related to the potential for fraud, significant risk to program integrity, and the need for improved program management and better oversight. We also cited the results of SBA’s financial statement audit, in which the auditor issued a disclaimer of opinion on SBA’s financial statements because SBA was unable to provide adequate documentation to support a significant number of transactions and account balances related to the PPP and COVID-19 EIDL.

The 2023 High Risk List updated the original designation and noted that SBA had fully met the leadership commitment requirements in several ways.[23] For example, SBA formed a High-Risk Working Group comprised of senior officials to resolve high-risk issues and created the Fraud Risk Management Board in February 2022 and designated it as SBA’s antifraud entity. However, as of the 2023 High Risk List update, SBA had yet to fully implement or provide adequate support for its fraud risk management efforts and address all the material weaknesses in internal controls reported by its financial statement auditor.[24]

Fraud Risk Management

To help combat fraud in government agencies and programs—both during normal operations and emergencies—GAO published A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs (Fraud Risk Framework) in 2015.[25] The objective of fraud risk management is to ensure program integrity by continuously and strategically mitigating both the likelihood and effects of fraud, while also facilitating a program’s mission. The Fraud Risk Framework identifies leading practices for managing fraud risks in a strategic, risk-based way and encompasses control activities to prevent, detect, and respond to fraud, with an emphasis on prevention.[26]

As discussed in the Fraud Risk Framework, while preventive controls offer the most cost-effective investment of resources, managers who effectively manage fraud risks develop a plan that describes how the program will respond to instance of fraud that occur, despite existing controls. Such a response includes referring instances of potential fraud to the OIG for further investigation.

Artificial Intelligence

AI involves computing systems that “learn” how to improve their performance. Machine learning is one type of AI. As defined in statute, “machine learning” is an application of AI that is characterized by providing systems with the ability to automatically learn and improve, on the basis of data or experience, without being explicitly programmed.[27] Agencies are required by executive order to prepare an inventory of their AI use cases.[28] Among other things, this applies to both existing and new uses of AI and AI developed both by the agency or by third parties, such as contractors, on behalf of agencies for the fulfilment of specific agency missions. The AI reporting requirements were aimed to ensure AI use awareness across the government and ensure agencies did not use AI irresponsibly, which could have exacerbated societal harms such as fraud, discrimination, bias, and disinformation.

SBA Developed and Implemented a Four-Step Process to Detect and Refer Likely Fraud Cases for COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP

According to SBA, the four-step process it developed and implemented to detect and refer likely fraud in COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP generally consisted of the following components for both programs:

· Screening: automated review, sometimes with additional manual components, that compared each application with several public and private databases and checked for internal inconsistencies that indicated data anomalies.

· Data analytics: various data analytic tools that examined data anomalies, sometimes using a type of AI called machine learning for the PPP to help identify files with data anomalies and in need of further review.

· Human-led reviews: manual reviews of files with data anomalies to determine if the file was ineligible or likely fraudulent.

· OIG referrals: referrals of likely fraudulent files to the OIG.

SBA officials noted that the process’s two main goals were to block attempted fraud and to position the agency to assist its OIG by referring only actionable loans.[29] SBA introduced this process and its various steps at different times and implemented them iteratively over the course of the pandemic. Therefore, the components of the process were not always implemented in a linear fashion. Moreover, the PPP and COVID-EIDL programs are different programs, with different program rules and structures. Therefore, there were differences in how the four-step process was designed and implemented for each program. According to SBA officials, they refer to it as the “four-step process” more as a term of art (rather than an official designation) to broadly describe the various fraud detection and referral efforts across the two programs.[30]

SBA Used a Four-Step Process to Implement Key Detection and Referral Activities for COVID-19 EIDL

Screening. SBA took various steps to set up its application processing system for COVID-19 EIDL and to expand automated screening checks. Its loan officers also performed manual screening as part of the underwriting process. For instance:

· Implementing an application processing system. In April 2020, SBA employed a contractor to implement an application processing system capable of handling the increased volume of applications stemming from the pandemic. Although SBA had an existing disaster loan processing system in place at the start of the pandemic, the system did not have the capacity to handle the high volume of COVID-19 EIDL applications.

· Requiring manual screening. After August 2020, SBA staff began manually reviewing all applications prior to approval and stopped approving applications in batches in response to an SBA OIG finding. Specifically, SBA’s OIG found that for the first 6 months of the program, applications without certain problems flagged by the automated validation system were being approved by team leaders in batches and with little to no additional review.[31] According to SBA, 36.7 million entities were automated and manually screened for COVID-19 EIDL.

· Incorporating Internal Revenue Service (IRS) tax information. In April 2021, based on the removal of a restriction put in place by the CARES Act, SBA began incorporating IRS tax information as part of its validation process. Specifically, it began using this information to confirm that businesses existed on or before January 31, 2020 (as required to receive COVID-19 EIDL funding), and to verify business revenue. Before January 2021, the CARES Act restricted the use of applicants’ tax information. The restriction made it challenging to verify applicant eligibility, as that was key to establishing that the business existed and that employee size and revenues were correct, according to SBA officials.[32]

· Incorporating Do Not Pay (DNP) information. SBA began screening applicants against Treasury’s DNP service in April 2021.[33] Specifically, SBA officials told us that they implemented a direct interface with DNP and that all subsequent applications were screened through DNP. According to SBA officials, if an application was flagged by DNP, it received a manual review prior to approval or disbursement.

· Incorporating the Suspicious Transaction Analysis and Reporting (STAR) tool. SBA officials told us that SBA added the STAR tool to its application processing system in summer 2021.[34] SBA used the tool to check applicants’ criminal history, among other things, prior to loan approval. Before this change was made, SBA relied on applicants’ self-attestation to determine if they had a criminal history that would make them ineligible for the program.

Data analytics. According to SBA officials, the agency began performing data analytics in April 2021, a year after the start of the program, to identify anomalies across all COVID-19 EIDL applications, loans, and advance data. However, the officials stated that the analytics introduced were not part of the application review process and were, thus, not required prior to loan approval or disbursement. Analyses included comparisons across loans, such as checks for duplicate bank accounts, and logic tests. The officials stated that the analyses were led by SBA’s Chief Data Officer, and any files with continued anomalies were sent to an internal team for manual review and referral to the SBA’s OIG, where appropriate.

Human-led reviews. SBA officials told us that the agency used human-led reviews for the EIDL program prior to the pandemic and that SBA took steps to expand this process during the pandemic for COVID-EIDL. Beginning in June 2020, SBA set up risk review teams to address suspected COVID-19 EIDL fraud, among other things, and added staffing to those teams. In particular, SBA created email accounts to report potential fraud for human-led review and possible referral to the SBA’s OIG. According to SBA officials, typically a human-led review was initiated when an SBA loan officer or other staff identified potential fraud and referred the case to SBA’s risk review team for additional review. The risk review team would then perform additional checks to try and confirm the applicants’ identity or, for example, reach out to the applicant, as necessary, to confirm information. If necessary, the risk review team referred instances of suspected fraud to the SBA’s OIG.

Referrals to the OIG. According to SBA officials, referral of suspected EIDL fraud predated the pandemic, with the agency regularly and routinely referring suspected instances of fraud and misuse to the SBA’s OIG. However, the officials explained to us that they changed the frequency and format with which they sent referrals of likely fraud to the SBA’s OIG during the pandemic, including in response to feedback from the OIG. For example, officials stated that while they initially provided the OIG with spreadsheets listing minimal data points for each referral, they began sending more comprehensive data in December 2020. SBA officials also noted that SBA referred suspected fraud to the OIG on a manual, as-needed basis. SBA reported in June 2023 that it referred 2.46 million COVID-19 EIDL applications and 520,000 funded loans and loan advances to the OIG for further investigation and law enforcement action.[35]

SBA Used Its Four-Step Process to Implement Key Detection and Referral Activities Controls for the PPP

Screening. In 2020, SBA did not screen loan or borrower information beyond looking for duplicate applications before issuing an SBA loan number to the lender making the loan.[36] However, beginning in January 2021, SBA implemented an automated screening tool for first and second draw loans in Round 2 to prevent fraud in the PPP, consistent with our June 2020 recommendation.[37] Notably, SBA added the front-end compliance checks to identify anomalies or attributes that may indicate noncompliance with eligibility requirements, fraud, or abuse after the lender requested a loan number but before the lender made the loan.[38] SBA compared loan applications against Treasury’s DNP service and public records and applied 19 fraud detection rules. Detection rules included checks for criminal record, inactive business, and determining whether the business was in operation as of February 15, 2020 (a requirement to be eligible for a PPP loan), among other checks. If the check identified a potential issue, a compliance check error message, or a hold code identifying the issue would be placed on the loan application, and the application could not proceed until it was resolved.[39] For instance, a hold code would be issued if there were discrepancies in the applicant’s name, or if the business was no longer active.

Starting with Round 2 between January and May 2021, small businesses could receive a second PPP loan, if they met certain conditions. According to SBA officials, second draw PPP loans were put through the same automated screening process used for Round 2 first draw loans. If this screening uncovered an issue, a compliance check error message would be sent to the lender. In addition, if there was a hold code placed on the first draw loan because of SBA’s screening of Round 1 loans, the application for a second draw loan would be delayed until the issue was resolved, if appropriate.

Beginning in August 2020, SBA retroactively reviewed all loans that already had received disbursements, using the new automated screening process. Of the 5.1 million Round 1 PPP loans that were retroactively reviewed, approximately 2 million were flagged as having at least one alert through automated screening and were flagged for additional SBA review.

Data analytics. In November 2020, SBA worked with its loan review contractor to put in place a new machine learning tool to rate borrower forgiveness applications according to fraud risk and to clear batches of loans flagged during automated screening that were considered low risk. The loan review contractor used historical data from prior application reviews to train a model to categorize new data and identify loans that were likely to receive approval for forgiveness. In addition to machine learning, in March 2021, the loan review contractor began analyzing some loans in the aggregate to identify and analyze relationships across loans, borrowers, and lenders, seeking to identify potentially suspicious relationships and activities.

Human-led reviews. Beginning in August 2020, SBA used a contractor to conduct loan eligibility and loan forgiveness reviews for Round 1 applications, instead of relying primarily on PPP lenders to review borrower self-certifications of eligibility, as was done since the program’s inception. The contractor also conducted loan eligibility and loan forgiveness reviews for Round 2 first and second draw loans. The contractor conducted automated and manual loan reviews to test for compliance with program requirements to evaluate the accuracy of PPP borrowers’ self-certifications.[40]

Referrals to the OIG. SBA officials informed us in August 2024 that SBA referred approximately 54,000 PPP loans with complete case memos and supporting documentation to the OIG for likely fraud via the SBA’s OIG hotline. In addition, they explained that approximately 77,000 loans were escalated internally for additional review by the agency.

SBA Implemented Its Four-Step Process for COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP After Most Funding Had Been Disbursed, and the Process Had Weaknesses

SBA’s Four-Step Process for Detecting and Referring Likely COVID-19 EIDL and PPP Fraud Was Not Fully Implemented Until After Most Funding Was Disbursed

SBA’s four-step process for detecting and referring likely COVID-19 EIDL fraud was not fully implemented until over half of the funding was approved. Specifically, expansions of automated screening and the addition of data analytics—key aspects of SBA’s four-step process—were not implemented until mid-2021, after over $210 billion (about 55 percent) of an eventual over $385 billion of COVID-19 EIDL loans and advances was disbursed. By this time, SBA had approved over 3.8 million loans, about 97 percent of the approximately 3.9 million loans it ultimately approved.[41] See figure 1.

Figure 1. Timeline of SBA’s Implementation of Key Controls in Its Four-Step Process as COVID-19 EIDL Funding Was Disbursed

Regarding the PPP, expansions of automated screening and human-led reviews—key aspects of SBA’s four-step process for detecting and referring likely fraud—were not implemented for the program until January 2021, after over $525 billion (about 66 percent) of an eventual $800 billion in PPP funding was approved. By this time, SBA had approved over 5.2 million loans, which is about 44 percent of the total loans it approved. See figure 2.

SBA’s implementation of key controls for COVID-19 EIDL and the PPP was reactive in nature—the controls were not implemented until more than half of the funding was approved. While fraud control activities can be interdependent and mutually reinforcing, preventive activities generally offer the most cost-effective investment of resources. Therefore, as discussed in the Fraud Risk Framework, effective managers of fraud risks focus their efforts on fraud prevention to avoid a costly “pay-and-chase” model.

Some of SBA’s COVID-19 EIDL Application Screening Controls Had Weaknesses

Some of the controls SBA added as part of its COVID-19 EIDL application screening processes—that is, portions of step 1 of the four-step process—had weaknesses that may have limited their usefulness in preventing and detecting likely fraud. Below are illustrative examples of vulnerabilities that the screening step of the four-step process was not able to mitigate effectively.

· Limitations in use of tax transcripts. SBA officials have said that the CARES Act’s restriction on using applicants’ tax information made it challenging to verify applicant eligibility. According to SBA officials, this information represented the primary measure SBA used before the pandemic to prevent fraud. It was key to confirming that businesses were legitimate and that requested loan amounts were appropriate. Without this tax information, prior to April 2021, the agency relied on self-certification of applicant information and the controls put in place as part of the automated and manual screening process. Whereas SBA retroactively reviewed funded PPP loans against new upfront automated controls to identify suspicious loans, as discussed below, SBA was not able to undertake a similar effort with COVID-19 EIDL loans using tax transcripts. SBA officials explained that a retroactive review with tax information would have required prior authorization from the borrower, and no such authorization was obtained during the initial application process.

Additionally, the SBA’s OIG identified weaknesses associated with SBA’s screening of loan applications after the tax transcript review was implemented. A September 2022 SBA OIG report found four disbursements, out of a sample of 10, approved after the tax transcript requirement was implemented that should not have been approved because the loans were ineligible.[42] Specifically, the loan files did not contain conclusive evidence from the tax transcript that the businesses existed on or before January 31, 2020. The OIG also found evidence of potential fraud in two of the 10 reviewed disbursements approved after the requirement was implemented. SBA agreed with the SBA OIG’s recommendation to review the cases and to make plans to attempt to recover funds if the disbursements were ineligible.

The text box contains an illustrative example we identified of a case in which tax transcript discrepancies did not prevent a fraudster from receiving COVID-19 EIDL funds.

|

In December 2021, a fraudster received $346,600 in COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (COVID-19 EIDL) funds by purporting to own and operate a nonprofit organization using falsified documentation, including a profit and loss statement fabricated solely for the purpose of obtaining the loans. The fraudster also falsely represented information, such as the number of employees employed by the business. The fraudster used most of the funds on personal items or expenses, including a vacation and the purchase of two vehicles. According to Small Business Administration officials, the fraudster’s application was initially flagged for multiple reasons, including an inability to locate the necessary tax transcripts. However, the flags were resolved through discussion with the applicant and the receipt of additional documentation. The fraudster pled guilty and was sentenced to restitution of $346,600, 21 months in prison, and 2 years of supervised release. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice information, court documents, and Small Business Administration documents. I GAO-25-107267

· Limited use of DNP. A June 2024 SBA OIG report found that the agency continued to award and disburse funds to those listed in DNP without sufficient evidence to support the loan decision.[43] The OIG reviewed a statistical sample of 278 loans and grants to borrowers listed on one or more of the DNP databases. The SBA’s OIG did not find any flags in SBA’s system to mark the sampled loans as matching a DNP record or any evidence of an attempt to resolve the DNP matches by loan officers prior to loan approval. It found that a total of $145.2 million was disbursed to potentially ineligible applicants whose loans matched a DNP record related to death, suspension or debarment, or delinquent child support. According to the SBA’s OIG, this occurred because SBA did not match applicants against all available DNP databases. Instead, SBA relied on credit bureau reports and borrower self-certification to identify applicants who were delinquent on child support and to identify applicants in default on federal debt who were suspended or debarred from doing business with the federal government. In response to this report, SBA agreed, among other things, to review and address those loans and grants with an alert in the file that was not previously addressed. According to the SBA’s OIG, the proposed corrective action did not fully satisfy the OIG’s recommendation to review all of the loans identified as potentially ineligible.

In addition, SBA’s independent financial statement auditor has identified multiple material weaknesses in internal controls over financial reporting that relate to the screening process, including in both the automated and manual review components for COVID-19 EIDL, that have persisted for several years. These material weaknesses, in part, led to the program being listed on GAO’s High Risk List. For example, the financial statement auditor found, among other things, that SBA had not developed adequate controls to address specific alerts within its application processing system. The auditor did not identify material weaknesses with the data analytics, human-led reviews, and referral to OIG steps. See table 1 for material weaknesses related to screening identified by the SBA’s financial statement auditor from 2020 through 2024.

Table 1: Material Weaknesses Identified by the SBA’s Financial Statement Auditor from 2020 to 2024 Regarding COVID-19 EIDL That Relate to Screening in the Four-Step Process

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

|

SBA did not have adequate procedures and controls in place to address certain alerts within its application processing system. |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

○ |

○ |

|

SBA did not adequately design and implement controls to ensure that approved COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loans (COVID-19 EIDL) and grants were provided to eligible borrowers and accurately recorded. |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

|

SBA could not provide sufficient evidence of a consistent process documenting how the COVID-19 EIDLs with hold codes were identified and resolved. |

○ |

○ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

Legend:

✖ = Material weakness identified by the SBA’s financial auditor

○ = Material weakness was not mentioned by the SBA’s financial auditor

Source: GAO analysis of Small Business Administration’s (SBA) financial statement audit opinions and SBA data. | GAO‑25‑107267

Note: This table does not reflect all of the material weaknesses identified by the SBA’s financial statement auditor, but the ones that best aligned with the fraud controls of SBA’s four-step process. The auditor did not identify material weaknesses with the data analytics, human-led reviews, and referral to Office of Inspector General steps. A material weakness is a deficiency in internal control over financial reporting such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the entity’s financial statements will not be prevented, or detected and corrected, on a timely basis.

SBA Lacks an Effective Referral Process for COVID-19 EIDL

While SBA incorporated referrals to the SBA’s OIG as step 4 of its four-step process for COVID-19 EIDL, we found that this process is not effective and, thus, could inhibit the OIG’s ability to investigate suspected fraud as SBA continues to service these loans. Specifically, SBA and OIG officials told us that they do not have an agreed-upon understanding of what information needs to be included in a referral and how to formally submit and receive actionable referrals.

In June 2023, SBA reported that out of 3 million flags generated from its automated screening tools and manual reviews for COVID-19 EIDL, it referred 2.46 million blocked COVID-19 EIDL applications and 520,000 funded loans and loan advances to its OIG for further investigation due to likely fraud.[44] However, SBA OIG officials told us that of the roughly 3 million total referrals, about 2 million were not actionable. They explained that these referrals were not actionable because, for example, they did not contain enough data elements to allow for further investigation or had quality issues, such as duplicates or incorrect information. Further, the referrals were sent via different mechanisms over time, including via spreadsheet or email. In this regard, SBA OIG officials stated that they considered emailed referrals with details on cases to be the most useful.[45]

GAO’s Fraud Risk Framework states that agencies should develop a plan outlining how the program will respond to identified instances of fraud.[46] Specifically, when instances of fraud are identified, managers should take steps to ensure that they respond promptly and that the response is consistently applied. This process is critical for ensuring the continued effectiveness of fraud risk management activities. However, for COVID-19 EIDL, SBA could not provide us with evidence of such a plan that included how referrals to the OIG would be handled.

Without an effective referral process, the SBA’s OIG is not able to fully investigate instances of potential or likely fraud and make downstream referrals to, for example, the Department of Justice for prosecution. Moreover, if the SBA’s OIG is unable to fully review potential or likely fraudulent cases to identity fraud, then SBA will have less opportunity to learn from actual fraud cases to inform detection efforts going forward.

Some of the SBA’s PPP Application Screening Controls Had Weaknesses

Some of the controls SBA added as part of its PPP application screening process—that is, portions of step 1 of the four-step process—had weaknesses that may have limited their usefulness in preventing and detecting likely fraud. Below are illustrative examples of vulnerabilities that the screening step of the four-step process was not able to effectively mitigate against and some examples where the controls did not work as intended:

· Fraudulent documentation. In January 2022, the PRAC issued a report finding that the upfront antifraud-screening controls put in place January 2021 would not have likely detected typical PPP fraud cases.[47] Namely, SBA had no internal controls aimed at identifying fraudulent documentation. Therefore, there is a high residual risk from fraudsters who falsify documents and misrepresent borrower self-certifications, which is a primary method of PPP fraud based on adjudicated DOJ fraud-related PPP cases.[48]

The text box contains an illustrative example we identified of a case in which the fraudster used fraudulent documentation to obtain PPP funds.

|

In March 2021, a fraudster was approved for a Paycheck Protection Program loan totaling approximately $73,000 using fictitious documentation that overstated the number of employees and corresponding monthly payroll expenses. The fraudster was a convicted felon at the time the application was submitted. The loan was initially flagged for a disqualifying business formation date, but the lender certified it collected documentation and certified the borrower was eligible. The fraudster used some of the funds to purchase a luxury vehicle. The lender and the Small Business Administration’s automated screening process did not identify that the applicant had a criminal record. The fraudster was sentenced to 5 years in prison; 5 years of supervised release; and restitution of approximately $190,000. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice information, court documents, and Small Business Administration documents. I GAO-25-107267

· Internet Protocol tracking. The same PRAC report noted that SBA had a gap in its analytic capabilities because it did not obtain internet weblogs to track the Internet Protocol (IP) or internet address of where borrowers submitted applications to help identify duplicate borrowers. For example, the PRAC found that in one PPP criminal case, four individuals submitted 16 applications using the same internet address, which could indicate potential fraud.

· Lender shopping. The PRAC report also noted that SBA did not track loans that PPP lenders denied and the reasons for denials. Nor did it collect information on the loans that lenders had internally flagged as ineligible or with fraudulent hold codes to allow other lenders to review these flagged applications more carefully. Analyzing such information could reduce instances of applicants’ shopping for weaker internal controls among lenders. This approach may have allowed lenders with less sophisticated fraud detection controls to leverage the more effective controls of other SBA lenders.

· Data-sharing limitations for screening. In January 2023, the PRAC issued a “fraud alert” involving Social Security Numbers (SSN) that were not sufficiently verified by SBA using Social Security Administration (SSA) data.[49] Specifically, the PRAC identified $5.4 billion in potentially fraudulent PPP (and COVID-EIDL) loan applications that used questionable SSNs by matching such loan applications with SSA data. In May 2023, the PRAC issued a follow-up to this fraud alert after conducing further analysis and identified $38 million in potentially improper or fraudulent pandemic loans associated with SSNs of deceased individuals.[50] Since SBA does not have legal access to SSA data, the PRAC recommended that they work with SSA to explore information-sharing agreement(s) that will allow them to conduct verifications across all SBA-funded grant, loan, and benefit programs that are vulnerable to identity fraud.

Similarly, GAO reported in May 2023 that almost 772,500 unique PPP recipients did not have any corresponding quarterly wage data reported to the National Directory of New Hires (NDNH).[51] Of these, almost 15,000 had received 100 percent forgiveness for loans totaling approximately $10 billion as of December 31, 2021. This suggests that these recipients may have obtained PPP funds for nonoperating businesses, such as shell companies or fictitious businesses, or for businesses that were not in operation by the respective eligibility cutoff dates. Currently, SBA does not have statutory access to NDNH data. We recommended, and SBA agreed, to identify external sources of data that can facilitate the verification of applicant information and the detection of potential fraud across its programs and to then develop a plan for obtaining access to those sources. This may involve pursuing statutory authority from Congress, or entering into data-sharing agreements with cognizant agencies to obtain such access.[52]

The text box contains an illustrative example we identified of a case in which the fraudster claimed to operate a business that did not exist, while also serving a prison sentence. Both of these factors should have disqualified the fraudster from receiving PPP funds. Data-sharing limitations for screening may have been a contributing factor in enabling the fraudster to fraudulently obtain the PPP funds.

|

In April 2021, after the new Small Business Administration’s (SBA) screening process was in place, a fraudster submitted two fraudulent Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan applications claiming business losses for a business that did not exist. The fraudster was serving a state prison sentence during the period he claimed to be running a business. The fraudster received approximately $41,000, and both loans were forgiven by SBA. The fraudster was sentenced to 44 months of prison; 3 years of supervised release; and restitution of the PPP loan amounts. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Justice information, court documents, and Small Business Administration documents. I GAO-25-107267

SBA’s Data Analytics via Machine Learning for PPP Was Limited, and SBA Did Not Follow AI Reporting Requirements

As part of SBA’s data analytics—that is, step 2 of the four-step process—SBA stated in June 2023 that the machine learning tool it began using in November 2020 was the “first of its kind artificial intelligence.” SBA further stated that the machine learning, among other tools SBA used, helped to “block” millions of PPP ineligible applications, including those attempting fraud.[53] While the machine learning tool helped SBA to both prioritize and deprioritize loans for a human-led review based on perceived risk, these loans had already been funded.

SBA officials further explained that the machine learning process was primarily a tool to reduce the number of applications for human-led review—that is, step 3 in the four-step process—due to the large volume of funded loans that were flagged retroactively once the automated controls were put in place. Machine learning was not applied to new PPP loan applications in 2021, as those applications went through the new, upfront antifraud-screening controls prior to funding.

According to SBA, using machine learning, its loan review contractor referred approximately 92,000 loans to SBA recommending that the agency forgive the loan without conducting a human-led manual review. These loans were determined to be at lower risk for fraud, even though fraud-related flags or alerts existed for them. SBA officials explained that this allowed them to focus on the higher-risk loans, helped to ensure that false positives were reduced and that forgiveness applications were elevated for human-led reviews, as well as that referrals to the SBA’s OIG were for actionable loans with a high risk of fraud. However, there is still a risk that funded loans that retroactively failed the upfront compliance checks, yet were deemed low risk via the machine learning tool, were in fact true positives and carried fraud risk. These loans received no additional reviews or referrals, if the funded loan was potentially fraudulent.

We recognize that, given the limitations on time and resources, reviewing millions of flagged loans may require prioritization of higher-risk loans. However, reviewing a subset of all funded loans flagged as suspicious raises questions about the usefulness of the various compliance checks, as well as how the machine learning thresholds were set to allow some combination of hold codes to no longer trigger additional reviews.[54] Though machine learning helped SBA prioritize loans for review, SBA did not use it to identify and analyze relationships across loans, borrowers, and lenders, or to seek to identify new types of potentially suspicious relationships and activities for fraud. Instead, it was primarily a measure to reduce the number of funded loans needing human-led reviews.

As mentioned earlier, agencies are required by executive order to prepare an inventory of their AI use cases. The AI reporting requirements were aimed to ensure AI use awareness across the government and ensure that agencies did not use AI irresponsibly, which could exacerbate societal harms, such as fraud, discrimination, bias, and disinformation. Despite SBA’s prior statements on the use of AI via press release statements, SBA officials told us during this review that they have never had any AI use cases.[55] SBA also reported that it did not have any AI use cases in fiscal years 2022 and 2023. As of December 2024, SBA had not reported an inventory of its AI use cases, including usage of machine learning for the PPP and did not post this information on its website when machine learning was in use.

SBA officials explained to us that they no longer consider the machine learning tool as related to AI and no longer use machine learning. However, as previously noted, as defined in statute, machine learning is a type of AI.[56]

In September 2024, SBA issued a compliance plan for advancing governance, innovation, and risk management for agency use of AI. This plan describes SBA’s process for soliciting and collecting AI use cases across all subagencies, components, and bureaus. Further, according to SBA’s 2024 fraud data analytics strategy, SBA has plans to develop a framework for program offices to evaluate return on investment for advanced fraud analytics capabilities, such as predictive modeling, AI, and machine learning.

Some of SBA’s PPP Human-led Review Controls Had Weaknesses

Some of the controls SBA added as part of its PPP human-led review process—that is, step 3 of the four-step process—had weaknesses that may have limited their usefulness in managing fraud risk.

· Loan review prioritization. In February 2022, the SBA’s OIG reported concerns regarding a loan review process change.[57] Specifically, in June 2021, SBA put in place a new process to prioritize loan reviews based on fraud risk, rather than those that had applied for forgiveness. The change allowed SBA to review PPP loans with a high risk of fraud that had not yet filed for forgiveness. However, this change also meant that a certain number of loans were manually reviewed after they had been forgiven. SBA’s changes to this process, including issuing and forgiving loans prior to an eligibility or forgiveness review, could have diminished SBA’s ability to recover funds, created a pay-and-chase environment, and resulted in the government expending additional resources to recover funds.

· Limited use of Treasury DNP. In March 2021, SBA began screening PPP applicants against DNP databases. However, in February 2024, the SBA’s OIG reported that SBA did not use all components of the DNP dataset and that some loans were approved without sufficient evidence to support the loan decision.[58] For example, the SBA’s OIG statistically sampled 176 of 25,634 loans with DNP matches and concluded that SBA appropriately resolved 84. The SBA’s OIG found that SBA inappropriately cleared the remaining 92 loans by either using predecisional memos that did not address the DNP hold codes, or the loan files did not contain sufficient documentation to support the SBA’s review decisions. By projection, the SBA’s OIG estimated that lenders disbursed, and SBA forgave, 12,234 of 25,634 loans (or 48 percent), totaling over $1.4 billion, without verifying the borrowers’ eligibility, which further exposed the program to financial losses and improper payments. According to the SBA OIG’s report, the SBA’s actions in response to the report findings were not sufficient to resolve the SBA OIG’s recommendation to review the 92 hold codes and determine if the borrowers were eligible for the PPP loans.

In addition, as with COVID-19 EIDL, the SBA’s independent financial statement auditor has identified multiple material weaknesses in the SBA’s financial statements that relate to the PPP human-led review step that have persisted for several years. These material weaknesses, in part, led to the program being added to GAO’s High Risk List. For example, the financial statement auditor found that SBA did not have effective monitoring controls over contractors’ review process, as well as over lenders and whether they followed the established procedures. The financial statement auditor also found that SBA had not verified all validation checks from its automated screening process. See table 2 for the material weaknesses identified by the financial auditor related to human-led reviews from 2020 to 2024.

Table 2: Material Weaknesses Identified by the SBA’s Financial Statement Auditor from 2020 to 2024 Regarding PPP That Relate to Human-led Reviews in the Four-Step Process

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|

|

SBA did not make sure that the relevant cohort of Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan guarantees and applications met PPP eligibility requirements by verifying with all of the validation checks available within its case management system. |

○ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

|

SBA’s review process was not properly designed to identify and resolve a complete list of potential noncompliance flags from the case management system that should have been addressed prior to approving the loan guarantees. |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

○ |

|

SBA did not perform a sufficient review of the application to ensure that lenders followed established procedures and adequately addressed the eligibility concerns raised from the case management system’s automated screening. |

○ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

|

SBA did not adequately design and implement controls to ensure PPP loan guarantees were comprehensively reviewed to address their respective eligibility flags and ultimately determine their eligibility for forgiveness. |

○ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

|

SBA did not show effective monitoring controls over the results from the key contractor involved in the review process. |

○ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

|

SBA did not adequately design and implement controls to ensure that purchase requests of PPP loan guarantees were appropriately reviewed to verify that requesting lenders met the program requirements prior to approving and disbursing the original loan. |

○ |

○ |

✖ |

✖ |

✖ |

Legend:

✖ = Material weakness identified by Small Business Administration’s (SBA) financial statement auditor

○ = Material weakness was not mentioned by SBA’s financial statement auditor

Source: GAO analysis of the SBA’s financial statement audit opinions and SBA data. | GAO‑25‑107267

Note: This table does not reflect all of the material weaknesses identified by the SBA’s financial auditor but summarizes the ones that best aligned with the fraud controls of the SBA’s four-step process. The auditor did not identify material weaknesses with the automated screening, data analytics, and referral to Office of Inspector General steps. A material weakness is a deficiency in internal control over financial reporting such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the entity’s financial statements will not be prevented, or detected and corrected, on a timely basis.

Conclusions

SBA distributed over $1 trillion in loans and grants to over 10 million small businesses in 2020-2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic. As fraud schemes emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, SBA adapted its existing fraud risk management approach and added controls to help prevent, detect, and respond to fraud. However, the four-step process SBA used during the pandemic to detect and refer instances of potential or likely fraud in COVID-EIDL and the PPP had weaknesses that persisted over time, as several entities, including GAO, the SBA’s OIG, and the agency’s independent financial statement auditor, have previously reported. Regarding specifically the fourth step of the process—making referrals to OIG—we identified weaknesses that reduced the effectiveness of the SBA’s efforts. By not having an effective plan for making referrals, SBA is limiting the ability of its OIG to fully investigate instances of likely fraud and make follow-on referrals to, for example, the Department of Justice for prosecution. The development of such a plan for COVID-19 EIDL loans that are still being serviced could also help inform the development of plans for future referrals to the OIG in other programs.

Recommendation for Executive Action

We are making the following recommendation to SBA:

The SBA Administrator should collaborate with the SBA’s OIG to develop an effective plan, including the data elements to be provided and the process to be used, for referrals of potential or likely COVID-19 EIDL fraud cases. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to SBA for its review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix I, SBA agreed with our recommendation and indicated it was taking steps to implement it. SBA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the SBA Administrator. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512- 6722 or bagdoyans@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Seto J. Bagdoyan

Director, Forensic Audits and Investigative Service

List of Committees

The Honorable Susan Collins

Chair

The Honorable Patty Murray

Vice Chair

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chairman

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Bill Cassidy,

M.D.

Chair

The Honorable Bernard Sanders

Ranking Member

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Rand Paul,

M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Tom Cole

Chairman

The Honorable Rosa L. DeLauro

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Mark E.

Green, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable James Comer

Chairman

The Honorable Gerald E. Connolly

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

The Honorable Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

GAO Contact

Seto J. Bagdoyan, (202) 512-6722 or bagdoyans@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Philip Reiff (Assistant Director), Scott Clayton (Analyst in Charge), Priyanka Bansal, Arturo Barrera, Colin Fallon, Joy Myers, Julius Mitchell, Maria McMullen, Abinash Mohanty, and James Murphy made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), Pub. L. No. 117-2, 135 Stat. 4; Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-260, div. M and N, 134 Stat. 1182 (2020); Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, Pub. L. No. 116-139, 134 Stat. 620 (2020); and CARES Act, Pub. L. No. 116-136, 134 Stat. 281 (2020).

[2]GAO, COVID RELIEF: Fraud Schemes and Indicators in SBA Pandemic Programs, GAO‑23‑105331 (Washington, D.C.: May 18, 2023).

[3]GAO, COVID-19: Opportunities to Improve Federal Response and Recovery Efforts, GAO‑20‑625 (Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2020).

[4]GAO, COVID-19: Critical Vaccine Distribution, Supply Chain, Program Integrity, and Other Challenges Require Focused Federal Attention, GAO‑21‑265 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 28, 2021).

[5]Small Business Administration, Office of Inspector General, COVID-19 Pandemic EIDL and PPP Loan Fraud Landscape, Report 23-09 (Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2023).

[6]Small Business Administration, Protecting the Integrity of the Pandemic Relief Programs: SBA’s Actions to Prevent, Detect, and Tackle Fraud (June 2023). In its report, SBA used the term “likely” fraud, as opposed to “potential” fraud, regarding the outcome of its four-step process. For that report, SBA defined “potential” fraud in broad terms, to include indicators of suspicious or inconsistent behavior requiring further review. SBA defined “likely” fraud as those potentially fraudulent cases that were analyzed and reviewed and determined by SBA to be likely fraudulent. As noted by SBA in its report, however, there is no agreed-upon definition or threshold of potential or likely. For the purposes of our report, we use SBA’s term of likely fraud in the context of describing SBA’s four-step process and its outcomes. Otherwise, consistent with our prior reporting and that of others, we use the term potential fraud.

[7]Fraud and “fraud risk” are distinct concepts. Fraud—obtaining something of value through willful misrepresentation—is a determination to be made through the judicial or other adjudicative system, and that determination is beyond management’s professional responsibility. Fraud risk exists when individuals have an opportunity to engage in fraudulent activity, have an incentive or are under pressure to commit fraud, or are able to rationalize committing fraud.

[8]Specifically, we recommended that SBA (1) ensure it has and utilizes mechanisms to facilitate cross-program data analytics and (2) identifies external data sources that could aid in fraud prevention and detection and develop a plan to obtain access to those resources. SBA has taken actions that partially address both recommendations, but they remain open as of December 2024.

[9]Machine learning is a type of artificial intelligence (AI) that uses algorithms to identify patterns in information. It begins with data and infers rules or decisions procedures to predict specified outcomes. For additional details on characteristics and types of AI, see GAO, Artificial Intelligence: Agencies Have Begun Implementation but Need to Complete Key Requirements, GAO‑24‑105980 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 12, 2023).

[10]The Pandemic Response Accountability Committee was established by the CARES Act to conduct oversight of the federal government’s pandemic response and recovery effort. The PRAC is composed of 21 federal inspectors general.

[11]Since completing our audit work, the executive order that created federal agency reporting requirements has been rescinded.

[12]GAO, A Framework for Managing Fraud Risks in Federal Programs, GAO‑15‑593SP (Washington, D.C.: July 2015).

[13]The focus of this report is the PPP and COVID-19 EIDL programs, as they are SBA’s largest pandemic relief programs. However, Congress also enacted two other pandemic relief programs—Restaurant Revitalization Fund (RRF) and Shuttered Venue Operators Grant (SVOG) programs. RRF provided about $29 billion in award funds (which did not need to be repaid) to recipients—businesses in the food service industry—to use for eligible expenses such as payroll, business debt, maintenance, or construction of outdoor seating. SVOG provided about $15 billion in grant funds to recipients, which included live performing arts and entertainment businesses affected by the pandemic. Recipients could use the funds for eligible expenses that enable business operations, such as payroll, rent or mortgage, and utility payments.

[14]The 7(a) loan program is SBA’s existing small business lending program. The program provides small businesses access to capital that they would not be able to access in the competitive market. EIDL, which is part of SBA’s Disaster Loan Program, provides low-interest loans to help borrowers—small businesses and nonprofit organizations located in a disaster area—meet obligations or pay ordinary and necessary operating expenses. In this report, we refer to the Economic Injury Disaster Loan provisions of SBA’s Disaster Loan Program as “traditional” EIDL and to the EIDL program designed to help small businesses recover from the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic as COVID-19 EIDL.

[15]PPP and Bank Fraud Harmonization Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-166, 136 Stat. 1365; and COVID-19 EIDL Fraud Statute of Limitations Act of 2022, Pub. L. No. 117-165, 136 Stat. 1363.

[16]A borrower’s first PPP loan, which could be received in either 2020 or 2021, is referred to as a “first draw loan.” Borrowers that received first draw loans could apply for a second draw PPP loan in 2021, based on different eligibility requirements.

[17]According to a 2022 PRAC report, SBA, in conjunction with the Department of the Treasury, approved a nationwide network of more than 5,000 lenders, including about 800 new lenders, to review PPP applications, assess borrowers’ eligibility, and decide on the suitability of making a loan under delegated authority. See Pandemic Response and Accountability Committee, Small Business Administration Paycheck Protection Program Phase III Fraud Controls (Jan. 21, 2022).

[18]The Bank Secrecy Act requires banks and other financial institutions to take precautions against money laundering and other illicit financial activities by conducting due diligence activities and informing Treasury of suspicious activity by their customers.

[19]Forgiveness amounts may be reduced if certain conditions are not met. For example, payroll costs must account for at least 60 percent of the total PPP forgiveness amount, salary or wage reduction can generally be no more than 25 percent during the covered period, and the borrower must generally maintain the average number of full-time employees during the covered period.

[20]During the PPP loan forgiveness process, the borrower submits a forgiveness application and documentation to the lender. The lender then has 60 days to review and submit its forgiveness decision (approved in full, approved in part, or denied) to SBA. SBA then pays for the loans that were not identified for additional review. See GAO, Paycheck Protection Program: SBA Added Program Safeguards, but Additional Actions Are Needed, GAO‑21‑577 (Washington, D.C.: July 29, 2021) for more details on the forgiveness process.

[21]See GAO, Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program: Additional Actions Needed to Improve Communication with Applicants and Address Fraud Risks, GAO‑21‑589 (Washington, D.C.: July 30, 2021), where we list the key legislation that made notable changes to the COVID-19 EIDL program.

[22]See GAO, High-Risk Series: Dedicated Leadership Needed to Address Limited Progress in Most High-Risk Areas, GAO‑21‑119SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2, 2021).

[23]We use five criteria—Leadership Commitment, Capacity, Action Plan, Monitoring, and Demonstrated Progress—to assess agencies’ progress in addressing high-risk areas identified in our High Risk List. For further detail on these criteria and SBA’s progress in meeting them, see GAO, High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

[24]A “material weakness” is a deficiency in internal control over financial reporting such that there is a “reasonable possibility” that a material misstatement of the entity’s financial statements will not be prevented, or detected and corrected, on a timely basis.

[26]The Payment Integrity Information Act (PIIA)requires the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to maintain guidelines for agencies to establish financial and administrative controls to identify and assess fraud risks and that incorporate leading practices detailed in our Fraud Risk Framework. Office of Management and Budget, Circular A-123, Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk Management and Internal Control (OMB M-16-17) directs agencies to adhere to the Fraud Risk Framework’s leading practices as part of their efforts to effectively design, implement, and operate an internal control system that addresses financial and nonfinancial fraud risks. 31 U.S.C. § 3357(b). The Fraud Reduction and Data Analytics Act of 2015 (FRDAA) originally required OMB to establish these guidelines for agencies in 2016. Pub. L. No. 114-186, 130 Stat. 546 (2016). FRDAA was repealed and replaced by PIIA in 2020.

[27]15 U.S.C. § 9401(11).

[28]In December 2020, Executive Order 13960 required agencies to prepare an AI use case inventory within 180 days of the Federal Chief Information Officers Council issuing guidance on such inventories. Executive Order 14110 required OMB to, on an annual basis, issue instructions to agencies for the collection, reporting, and publication of agency AI use cases. See The White House, Promoting the Use of Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence in the Federal Government, Exec. Order 13960 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 3, 2020); and Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence, Exec. Order 14110 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 30, 2023). As noted above, since we completed our audit work for this report, the executive order that created the requirement for the collection, reporting, and publication of use cases has been rescinded. Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions, Exec. Order 14148 (Washington D.C.: Jan. 20, 2025). The term “use case” refers to specific challenges or opportunities that AI may solve. For more information on AI use cases, see GAO, Artificial Intelligence: Agencies Have Begun Implementation but Need to Complete Key Requirements, GAO‑24‑105980 (Washington, D.C.: December 2023).

[29]SBA defined “actionable loans” as loans with a higher likelihood of truly being fraudulent, following manual review.

[30]SBA has also reported on the use of the four-step process. See Small Business Administration, Protecting the Integrity of the Pandemic Relief Programs.