QUADRENNIAL HOMELAND SECURITY REVIEW

Improvements Needed to Meet Statutory Requirements and Engage Stakeholders

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107269. For more information, contact Chris Currie at CurrieC@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107269, a report to congressional requesters

QUADRENNIAL Homeland Security REVIEW

Improvements Needed to Meet Statutory Requirements and Engage Stakeholders

Why GAO Did This Study

Homeland security threats continue to evolve and include challenges ranging from terrorist attacks to natural disasters. This situation underscores the need for DHS to periodically examine and strengthen the nation's homeland security strategy.

The Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act require that every 4 years DHS—in consultation with other stakeholders—conduct a Quadrennial Homeland Security Review, which is a comprehensive examination of the nation's homeland security strategy.

GAO was asked to assess DHS’s 2023 review and report. This report assesses the extent to which (1) DHS met statutory requirements and (2) DHS and its stakeholders use the report to execute their homeland security roles.

GAO analyzed relevant statutes and documentation of the review and report. GAO also interviewed stakeholders, including representatives of eight DHS component agencies; three other federal agencies, such as the Department of Defense; and 11 external stakeholders, such as state agencies.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that DHS develop and document processes and procedures for (1) conducting the Quadrennial Homeland Security Review to ensure it meets all statutory requirements in future reviews and (2) engaging stakeholders, including when and how to engage stakeholders in the review. DHS concurred with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

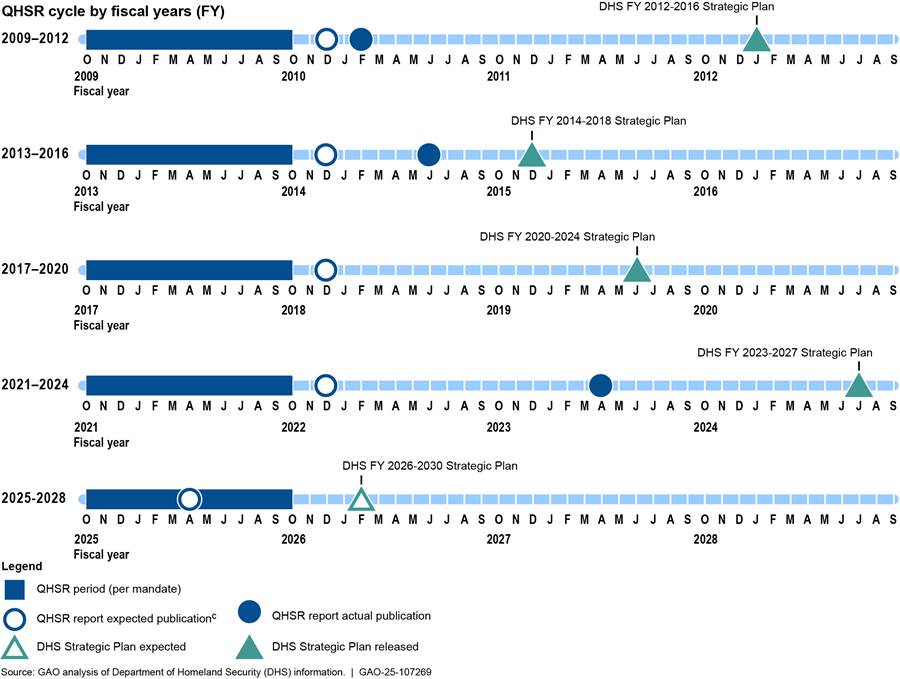

GAO found that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) did not fully meet 10 of the 21 identified statutory requirements for the 2023 Quadrennial Homeland Security Review and accompanying report. Among other elements, DHS did not fully meet requirements for prioritizing missions, providing a budget plan to meet those missions, and issuing the report by the established time frame. For example, DHS was to issue the report every 4 years beginning in fiscal year 2009, however, DHS did not issue a report for 9 years following issuance of its 2014 report. As a result, DHS drafted a new strategic plan during that time without affirming the homeland security priority missions through the review. DHS officials could not explain why DHS did not fully meet the statutory requirements because there is limited documentation of the steps taken for conducting the review. The figure below depicts phases for conducting the review, but DHS documentation does not have details on the processes and procedures for conducting each phase. Developing and documenting processes and procedures for conducting the review could better position DHS to meet all statutory requirements and use timely information in planning its efforts to address constantly evolving homeland security threats.

GAO found that DHS has processes to use the report as a foundation for making annual resource decisions. Specifically, DHS has internal guidance for using it to inform its strategic plan and budget. However, the effectiveness of this guidance and use of the report depends on DHS issuing the report prior to its Strategic Plan. Not issuing the report on time could lead to a strategic plan that does not take into account the most recent homeland security environment. Additionally, DHS is statutorily required to consult with certain stakeholders, including other federal agencies and state agencies, when conducting the review. DHS states in its 2023 report that DHS’s success in accomplishing its missions depends on partnerships with these stakeholders, but stakeholders GAO contacted said they generally do not use the report. Developing and documenting processes and procedures for engaging stakeholders may help ensure that DHS solicits and incorporates meaningful input from all stakeholders. It could also result in a better understanding of all stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities in their partnerships with DHS.

Abbreviations

DHS Department of Homeland Security

FY Fiscal Year

GPRA Government Performance and Results Act

NDAA James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act

Office of Policy Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans

QHSR Quadrennial Homeland Security Review

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 7, 2025

Congressional Requesters

Our nation faces a variety of homeland security threats—including terrorism, natural disasters, and cyberattacks—that are constantly evolving and pose an array of challenges. According to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), from January 2022 to July 2024, domestic violent extremists conducted seven fatal attacks resulting in 22 deaths in the United States, and law enforcement has disrupted at least a dozen other plots.[1] For example, in May 2022, an alleged racially motivated violent extremist attacked a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, killing 10 individuals. The attacker adhered to a white supremacist ideology—specifically targeting Black people—and drew inspiration from previous racially motivated violent extremist attackers and their online materials. The defendant pleaded guilty, was sentenced in state court, and is awaiting trial on federal hate crimes and other charges.

In the cyber domain, financially motivated cyber criminals continue to employ ransomware and other schemes that disrupt targeted critical infrastructure and impose significant financial costs on their victims, according to DHS. For example, a 2024 ransomware attack against the United States’ largest payment exchange platform for prescription drugs led to nationwide disruptions to pharmacy and hospital services for at least 2 weeks and cost over $20 million in ransom payments.

Evolving homeland security threats emphasize the need for DHS to periodically examine and strengthen the nation’s homeland security strategy. The Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 requires that every 4 years, beginning in fiscal year 2009, DHS—in consultation with other federal agencies, state, local, and tribal governments, as well as private sector stakeholders—conduct a Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR). This review is a comprehensive examination of the nation’s homeland security strategy.[2] According to the act, the review is to delineate and update, as appropriate, the national homeland security strategy, outline and prioritize the full range of critical homeland security missions, and assess the organizational alignment of DHS with the homeland security strategy and missions, among other things.[3]

To date, DHS has issued three QHSR reports (2010, 2014, 2023).[4] This review focuses on the most recent QHSR report issued in 2023. We previously reviewed the 2010 and 2014 QHSR reports and made seven recommendations and, as of April 2025, DHS had implemented two of the seven.[5] The remaining five recommendations that DHS did not address focused on enhancing DHS’s stakeholder consultations, stakeholder roles and responsibilities, as well as improving and documenting its risk analysis—issues that remain relevant, as discussed in more detail later in this report.

You asked us to review issues related to the 2023 QHSR. This report addresses the following questions:

1. To what extent did DHS meet statutory requirements for the 2023 QHSR?

2. To what extent do DHS and its stakeholders use the QHSR report to execute their homeland security roles?

To assess the extent to which DHS completed the 2023 QHSR in accordance with statutory requirements, we reviewed the 2023 QHSR report and DHS’s Future Years Homeland Security Program report covering fiscal years 2022 through 2026. We also reviewed DHS documentation related to the development of the 2023 QHSR report, such as a summary of DHS’s external and stakeholder consultations for the 2023 QHSR. Specifically, three GAO analysts independently reviewed the relevant documentation and compared them to each of the 11 review and 10 reporting statutory requirements. They used this comparison to determine whether DHS met, partially met, or did not meet each statutory requirement of the 9/11 Commission Act. If the analysts disagreed, they discussed their independent assessments to reach concurrence.

In addition, we interviewed DHS officials involved in the QHSR to determine DHS’s position on how they addressed the 9/11 Commission Act review and reporting requirements. We also compared documentation related to conducting the 2023 QHSR against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[6] Specifically, we determined that the control environment and control activities components of internal control were significant to this objective. We analyzed the extent to which DHS has internal controls—such as assigned responsibilities and documented processes and procedures—to ensure the 2023 QHSR met statutory requirements.

To determine the extent to which DHS and its stakeholders use the QHSR report to execute their homeland security roles, we analyzed DHS strategic documents including the 2023 QHSR report; DHS’s Fiscal Years 2020–2024 and 2023–2027 strategic plans; and DHS’s Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Instruction. We also analyzed excerpts from DHS’s fiscal years 2026–2030 Resource Allocation Plan guidance related to its program and budget review process. We reviewed these documents to determine the extent to which DHS budget guidance addresses QHSR report use and alignment with other DHS strategic documents.

We also reviewed DHS documentation related to the development of the 2023 QHSR report. Further, we interviewed QHSR internal stakeholders such as DHS officials within the Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans (Office of Policy) that manages the QHSR, the eight DHS operational components, the Office of the Chief Financial Officer, the Science and Technology Directorate and the Office of Intelligence and Analysis. Additionally, we interviewed or solicited written responses to our questions from other federal and external stakeholders. These included three of the eight federal agencies DHS is statutorily required to consult, as well as representatives from 11 states and private sector associations and non-governmental organizations.[7] We selected these stakeholders randomly from various lists of stakeholders that DHS officials said they consulted while conducting the QHSR. From our review of the relevant documentation as well as our interviews with DHS officials with the Office of Policy and component offices, we identified DHS policies and guidance related to strategic planning and budget alignment with the QHSR.

We also determined the extent to which selected other federal and external stakeholders use the QHSR report from our interviews and stakeholders’ written responses. Further, we compared documentation and procedures related to DHS’s engagement of stakeholders against Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[8] Specifically, we determined that the information and communication component of internal control was significant to this objective. We analyzed the extent to which DHS leveraged information to communicate with internal and external stakeholders to ensure use of the 2023 QHSR report.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Roles and Responsibilities

Pursuant to statute, DHS is responsible for conducting the QHSR.[9] Several offices within DHS have key responsibilities supporting the QHSR, as well as strategy and budget planning:

· The Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans (Office of Policy) is responsible for leading the development and coordination of department-wide strategies, policies, and plans, including the QHSR report and the DHS Strategic Plan.

· The Office of the Chief Financial Officer controls and manages development, justification, and defense of the department’s budget submission and the Future Years Homeland Security Program report.[10] It is also responsible for managing the department’s Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution process.

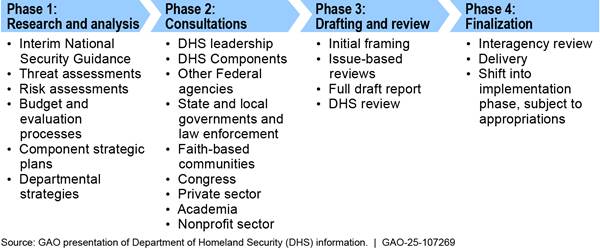

For the QHSR, the 9/11 Commission Act requires DHS to consult with specific stakeholders.[11] These stakeholders fall into three main categories: (1) internal DHS stakeholders; (2) other federal stakeholders; and (3) external stakeholders, including, but not limited to, state agencies and private sector representatives. See figure 1 for the QHSR stakeholders and how DHS consulted them while conducting the 2023 QHSR.

Figure 1: Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR) Stakeholders and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Consultation Mechanisms

DHS’s Approach for the 2023 QHSR

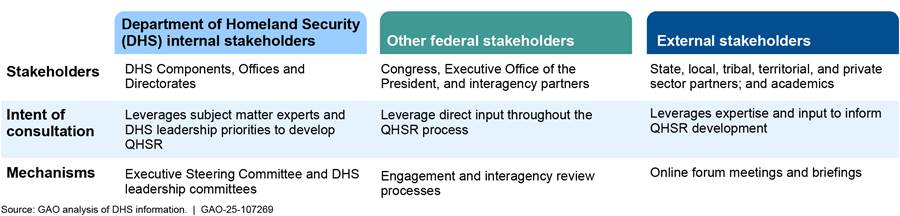

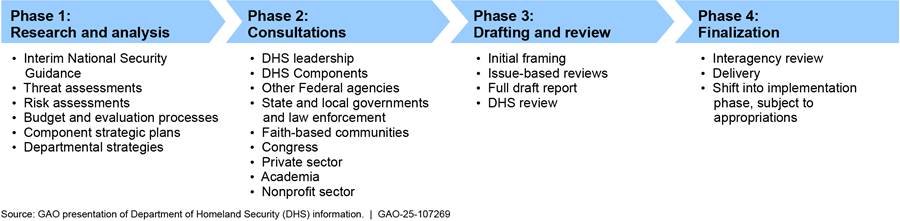

According to the 2023 QHSR report, DHS’s approach for conducting the 2023 QHSR involved four phases: (1) research and analysis, (2) consultations, (3) drafting and review, and (4) finalization (see fig. 2 for more details on each phase). The first phase, according to DHS, included a review of key department strategies and documents, such as threat and risk assessments and component strategic plans. The second phase was to focus on consulting with internal stakeholders, including DHS leadership and component offices, as well as other stakeholders such as federal agencies, state and local governments, and industry partners. DHS drafted the QHSR report in the third phase based on information collected from the previous phases, according to DHS officials. Finally, in the fourth phase, DHS provided the draft QHSR report to other federal agencies to review, followed by finalization of the report.

Relationship of the QHSR to the DHS Strategic Plan and Budget Development Process

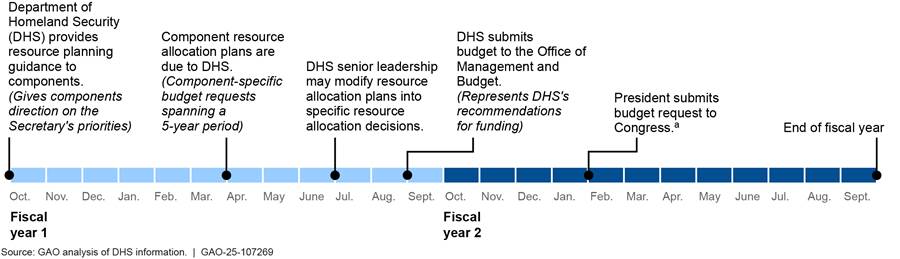

DHS uses a planning, programming, budgeting, and execution process to allocate resources. This process produces the 5-year funding plans presented in its Future Years Homeland Security Program. According to DHS guidance, at the outset of the annual process, the department’s Office of the Chief Financial Officer and Office of Policy should provide fiscal guidance and resource planning guidance, respectively, to the department’s component agencies.[12]

In accordance with this planning and fiscal guidance, the components should submit 5-year funding plans—called Resource Allocation Plans—to the Office of the Chief Financial Officer and DHS’s senior leaders. Components must indicate how changes in their Resource Allocation Plans from one year to the next relate to the QHSR missions. DHS senior leadership may modify the plans in accordance with their priorities and assessments into specific resource allocation decisions, which serve to formalize the Secretary’s resource decisions. DHS then uses the Resource Allocation Decisions to develop the Office of Management and Budget justification that informs the President’s annual budget request for the department.

DHS guidance establishes approximate timelines for when guidance is to be provided to components and when budget plans are due for this annual budget development process, as shown below in figure 3.

aPer statute, the President is to submit the President’s Budget by the first Monday in February. Pub. L. No. 101-508, 13112(a)(4), 104 Stat. 1388-1, 1388-608 (1990) (codified as amended at 2 U.S.C. 631).

Overview and Evolution of QHSR Missions

The 2010 QHSR report established five missions for accomplishing the nation’s homeland security strategy: (1) prevent terrorism and enhance security, (2) secure and manage our borders, (3) enforce and administer our immigration laws, (4) safeguard and secure cyberspace, and (5) strengthen national preparedness and resilience. According to the 2014 QHSR report, the review adopted the same five missions set forth in the 2010 QHSR report but revised the objectives within those missions. The report stated that this revision reflected changes in the strategic environment and areas where homeland security partners and stakeholders had matured, evolved, and enhanced their capabilities and understanding of the homeland security mission space. Specifically, the 2014 QHSR report provided revised goals for cybersecurity protection that include leveraging technology and enhancing investigative capabilities. The 2023 QHSR report further reaffirmed the five homeland security missions set forth in the 2010 and 2014 QHSR reports and similarly refined the objectives to reflect the evolving landscape of homeland security threats and hazards. It also introduced a sixth homeland security mission—combat crimes of exploitation and protect victims—which, according to DHS, reflects the overriding urgency of supporting victims and stopping perpetrators of such crimes.

Prior GAO Reviews

We previously reviewed the 2010 and 2014 QHSRs and made a total of seven recommendations. These recommendations were generally focused on (1) enhancing stakeholder consultations and (2) improving and documenting the QHSR risk assessment methodology. As of April 2025, DHS had fully implemented two of the seven recommendations, and had not implemented the remaining five, as shown in table 1. Some of the previously identified issues—specifically those related to stakeholder engagement and the lack of documentation—persist and are addressed later in this report, while others may no longer be relevant.[13]

|

QHSR reports |

Recommendations on enhancing stakeholder consultations |

Recommendations on improving and documenting risk assessment methodology |

|

2010 QHSRa |

Recommendation 1: Provide more time for consulting with stakeholders during the QHSR process to help ensure that stakeholders are provided the time needed to review QHSR documents and provide input into the review. Status: Not implementedb Recommendation 3: Examine additional mechanisms for obtaining input from nonfederal stakeholders during the QHSR process. Status: Implemented |

Recommendation 2: Examine the extent to which risk information could be used as one input to prioritize QHSR implementing mechanisms, including reviewing the extent to which the mechanisms could include characteristics, such as defined outcomes, to allow for comparisons of the risks addressed by each mechanism. Status: Implemented |

|

2014 QHSRc |

Recommendation 1: Identify and implement stakeholder meeting processes to ensure that communication is interactive when project planning for the next QHSR. Status: Not implemented Recommendation 3: Clarify component detailee roles and responsibilities when project planning for the next QHSR. Status: Not implemented |

Recommendation 2: Ensure future QHSR risk assessment methodologies reflect key elements of successful risk assessment methodologies, such as being documented, reproducible, and defensible. Status: Not implemented Recommendation 4: Refine QHSR risk assessment methodology so that in future QHSRs it can be used to compare and prioritize homeland security risks and risk mitigation strategies. Status: Not implemented |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107269

aGAO‑11‑873. In addition to this report, we also issued another report on the 2010 QHSR (GAO‑11‑153R) and made no recommendations in that report.

bWhen we reviewed the 2014 QHSR, we surveyed stakeholders and found that DHS did not implement this recommendation.

cGAO‑16‑371. We closed the four recommendations from this report as not implemented when DHS did not issue the QHSR in 2018.

DHS’s Lack of Documented Processes for the QHSR Affects Its Ability to Meet Statutory Requirements

DHS Did Not Meet All Statutory Requirements for the 2023 QHSR

We found that DHS partially met eight and did not meet two of the 21 QHSR statutory requirements, including requirements for issuing the report by the established time frame, prioritizing homeland security missions, and providing a budget plan to meet those missions.[14] The 9/11 Commission Act provides specific requirements for the QHSR and subsequent report, as described in appendix I.[15] These requirements identify actions DHS is to take when conducting the review and reporting the results, such as time frames, consultations, and contents of the review and the report. We assessed the QHSR and subsequent report against the statutory requirements to determine the extent to which DHS met the requirements.

For example, the 9/11 Commission Act required DHS to conduct the QHSR in fiscal year 2009 and every 4 years thereafter. Additionally, DHS is to publish a report about the QHSR by December 31 of the year that the review took place.[16] As with previous QHSRs, DHS did not issue the most recent QHSR report by the required deadline, as shown in table 2.

Table 2: Deadlines and Actual Issuance Dates for the Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR) Reports

|

Time frame for QHSR |

Deadline for QHSR report to Congress |

QHSR report to Congress issuance |

|

Fiscal year 2009 |

December 31, 2009 |

February 2010 |

|

Fiscal year 2013 |

December 31, 2013 |

June 2014 |

|

Fiscal year 2017 |

December 31, 2017 |

None issued |

|

Fiscal year 2021 |

December 31, 2021 |

April 2023 |

Source: GAO analysis of statute (Pub. L. No. 110-53, 2401(a), 121 Stat. 266, 543-545 (2007) (codified as amended at 6 U.S.C. 347)) and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR) reports. | GAO‑25‑107269

Note: The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2023 changed the required timing of the issuance of the QHSR report, stating that the QHSR report be issued “not later than 60 days after the date of the submission of the President’s budget for the fiscal year after the fiscal year in which a quadrennial homeland security review is conducted.” Pub. L. No. 117-263, 7141(a)(3)(A), 136 Stat. 2395, 3652 (2022). Though the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2023 states that amendments made by the act shall apply with respect to a QHSR conducted after December 31, 2021, DHS states in the 2023 QHSR report that the department substantially completed the review prior to the enactment of these amended requirements and sought to avoid or mitigate any further delay in submitting it to Congress.

Additionally, the act requires DHS to prioritize the full range of the critical homeland security mission areas.[17] While the QHSR report identifies six mission areas that DHS officials say encompass the most significant threats to the nation, these mission areas are not prioritized, as required. See appendix I for complete details on our assessment, including which requirements DHS met, partially met, and did not meet for the 2023 QHSR.

DHS officials could not explain why DHS did not fully meet some requirements. For example, regarding the budget plan requirements, Office of Policy officials stated that the 2023 QHSR report provides “a vision and prioritization” for the department’s budget. However, we did not find expected elements of a budget plan in the 2023 QHSR report, and officials could not explain why the requirement was not completed. Additionally, when asked to provide a timeline for the QHSR development and drafting, which could demonstrate DHS’s plan for meeting the statutorily required deadline, DHS could not do so.

Office of Policy officials said there was limited documentation about the steps taken to prepare the 2023 QHSR report and the previous 2018 draft QHSR report that was not finalized. Officials who conducted the review for the 2023 QHSR, and staff with the office in the 2018 time frame, are no longer with Office of Policy. Office of Policy officials we interviewed in September 2024 stated that they were not involved and did not know how the QHSR was conducted because of limited documentation or records. Therefore, they could not speak to how meeting statutory requirements was considered in the 2023 QHSR or the unfinished 2018 QHSR process.

Based on available information in the QHSR reports, DHS took different approaches to develop each of the three QHSRs. For example, for the 2014 QHSR, the Office of Policy requested and received detailee staff at the supervisory level from each of the DHS internal components to serve a 6-month assignment with the QHSR core team. The Office of Policy did not request or receive detailee staff for the 2010 and 2023 QHSRs. Additionally, for the 2010 and 2014 QHSRs, DHS convened study groups led by a DHS official and facilitated by an independent subject matter expert, which researched and developed recommendations for the QHSR report content. DHS took a different approach to the 2023 QHSR by having DHS officials conduct issue-based reviews. This included reviewing 11 topics selected by the department as the most impactful topics to DHS’s missions. While approaches to developing the QHSR may need to change over time, we have found DHS has not fully met all statutory requirements for any of its three released QHSR reports, highlighting the importance of developing processes and procedures to ensure all statutory requirements for the next QHSR are met.

In September 2018, we reported on challenges the Office of Policy has faced in leading, conducting, and coordinating department-wide and crosscutting policies and efforts—including issues related to repeatability and lack of documented processes and procedures.[18] In particular, we found that the Office of Policy’s efforts were sometimes hampered by the lack of clearly defined roles and responsibilities and that the Office of Policy did not have a consistent process and procedure for its strategy development and policymaking efforts, which includes the QHSR.

We recommended that DHS finalize a delegation of authority or similar document that clearly defines the Office of Policy’s mission, roles, and responsibilities, which DHS subsequently did in December 2019. We also recommended that DHS should create corresponding processes and procedures to help implement the mission, roles, and responsibilities defined in the delegation of authority to help ensure predictability, repeatability, and accountability in department-wide and crosscutting strategy and policy efforts.

However, as of December 2024, DHS has not taken steps to implement our recommendation to create processes and procedures for key strategy development and policymaking efforts, such as the QHSR.[19] We found similar issues within the Office of Policy, among other factors, caused the 2023 QHSR report to be issued late and not meet all requirements. Furthermore, DHS officials also stated that not issuing the QHSR report regularly—as happened when a QHSR report was not issued in 2018—can make the process more difficult and time consuming for the next QHSR. For example, covering the time between the 2014 QHSR and the 2023 QHSR required officials to understand and document 9 years of threats, which officials noted was very challenging because of the quick changing nature of the current threat landscape. Additionally, as discussed later in this report, some of DHS’s efforts were not informed by the type of comprehensive examination of the homeland security strategy that the QHSR is to provide when completed on time and in accordance with statutory requirements. For example, its fiscal years 2020–2024 strategic planning was not informed by the QHSR. DHS officials said that developing processes and procedures would be helpful to ensure that future QHSRs would be more timely and complete. Doing so would help ensure that the national homeland security strategy is delineated and updated every four years, as statutorily required, to be better positioned to effectively address the constantly evolving homeland security threats.

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, it is important for management to document and maintain internal control systems, including processes and procedures for core responsibilities, such as conducting the QHSR.[20] Effective documentation assists in management’s design of internal controls by establishing the internal control responsibilities of the organization and communicating the who, what, when, where, and why of internal control execution to personnel. Documentation also provides a means to retain organizational knowledge and mitigate the risk of having that knowledge limited to a few personnel. Developing and documenting processes and procedures for conducting the QHSR, including processes and procedures to meet all statutory requirements, could help ensure future QHSRs meet these requirements. Further, such documented procedures could help predictability and repeatability if QHSR staff transition to other roles.

DHS’s 2023 QHSR Approach Does Not Position DHS to Meet Future Risk Assessment Requirements

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes new provisions relating to the QHSR.[21] Among other requirements, future QHSR reports are to include information and documentation on “the risk assessment of the assumed or defined national homeland security interests of the Nation that were examined for the purposes of that review.”[22]

For the 2023 QHSR, Office of Policy officials stated that DHS reviewed risk and threat briefings to determine the most pressing threats to homeland security. Officials stated that this review included leveraging existing analytic documents, component strategies and strategic plans, departmental budget documents, risk assessments, and classified intelligence assessments. We reviewed some of the risk assessments and classified intelligence assessments that DHS used in developing the QHSR and determined that they generally align with the threats identified in the QHSR report.

Based on their review of the risk and threat briefings, DHS officials stated that DHS conducted a full analysis of all five key homeland security mission areas and determined that one additional mission area—combat crimes of exploitation and protect victims—should be included to cover the department’s extensive work in this area. Officials stated that this process constituted their risk assessment process for the 2023 QHSR. However, Office of Policy officials could not provide any documentation on the process, including rationale for adding the new mission or any supporting analysis. Office of Policy officials stated that they were planning to document procedures, including procedures related to risk assessments, for the next QHSR iteration but have not done so as of November 2024.

We previously reported in 2016 that DHS’s risk assessment process for the QHSR was not documented.[23] We recommended that future QHSR risk assessment methodologies reflect key elements of successful risk assessment methodologies, such as being documented, reproducible, and defensible. However, DHS has not implemented that recommendation.

As stated above, development and documentation of processes and procedures is a necessary part of an effective internal control system. Given the new QHSR requirement for risk assessment documentation, developing and documenting processes and procedures for conducting the QHSR including, but not limited to, risk assessments, would serve as a valuable internal control to better position DHS to meet statutory requirements.

DHS Has Taken Actions Requiring Internal Use of the QHSR, but Stakeholder Engagement and Use Are Limited

We found that DHS has processes to use the QHSR report as a foundation for making annual resource decisions in support of its homeland security role and missions. To do so, the department has provided guidance to its component agencies for aligning their strategic planning and budget with the QHSR report and has established procedures for implementing that guidance. For example, the DHS Strategic Plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027 organizes the department’s strategic goals and objectives into the six missions defined in the QHSR. However, although statutory time frames call for the QHSR report to be issued before the Strategic Plan, DHS did not issue a QHSR report prior to its fiscal years 2020–2024 Strategic Plan.[24] Additionally, DHS’s approach to stakeholder engagement, and the limited focus on other stakeholders’ efforts and homeland security roles in the QHSR report, may be affecting stakeholders’ use of the QHSR report. DHS states in the 2023 QHSR that DHS’s success in accomplishing its missions depends on partnerships with other stakeholders, but stakeholders with homeland security roles whom we contacted said they generally do not use the QHSR report or questioned the report’s usefulness.

DHS Use of the QHSR for Strategic and Budget Planning

In 2016 DHS provided internal guidance for using the QHSR to inform its strategic plan and budget. For example, the DHS Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution Instruction states that during the planning phase, DHS is to provide components with direction for implementing the QHSR report and DHS Strategic Plan to ensure that the department is actively using both documents when making annual resource decisions.[25] Additionally, in 2024, DHS introduced new guidance requiring components to align any annual changes in their Resource Allocation Plans with a corresponding 2023 QHSR mission to inform the DHS Secretary’s resource allocation decisions to the Office of Management and Budget.[26] To ensure implementation of this guidance, officials with DHS’s Office of the Chief Financial Officer stated that they added the QHSR missions to a drop-down menu in the data system it uses for tracking the department’s budget justification changes. This helped ensure that components indicated a QHSR mission for their Resource Allocation Plan submissions, according to DHS officials.[27] Thus, DHS components are required to link each program, project, and activity to a corresponding mission in the QHSR report

We interviewed officials from all eight DHS operational components and officials from two DHS directorates with key roles in QHSR, and they identified various ways they use the QHSR for their strategic and budget planning. For example, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officials stated that the QHSR report informs their broader mission areas and provides an indication of where to funnel budget resources. These officials added that they requested funding for a new role in asylum processing that was highlighted in the 2023 QSHR as part of the evolution in DHS’s mission to administer the nation’s immigration system.[28] However, they said that they rely primarily on what is in the DHS Strategic Plan as well as the Secretary’s Priorities rather than the QHSR report. Nonetheless, they stated that they see an alignment of the QHSR report, DHS Strategic Plan, and the Secretary’s Priorities.

Although DHS policy calls for its Strategic Plan to align with the QHSR report, the effectiveness of this guidance and use of both documents depends on DHS issuing the QHSR report prior to its Strategic Plan. As shown in figure 4, the statutory time frames call for the QHSR report to be issued before the Strategic Plan, which could ensure that DHS establishes or affirms its priority missions through the QHSR prior to expanding on plans to achieve those missions in the Strategic Plan. However, as also shown in figure 4, DHS did not issue a QHSR report as required by December 31, 2017. As such, DHS drafted its fiscal years 2020–2024 Strategic Plan—which was issued on June 27, 2019— without an updated QHSR report to inform it, according to DHS officials.

Figure 4: Required and Actual Time Frames for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR) and Strategic Plan

Notes: The 9/11 Commission Act required DHS to issue the QHSR report by December 31 of the year in which the QHSR was conducted. Pub. L. No. 110-53, 2401(a), 121 Stat. 266, 545 (2007). The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 changed the required timing of the issuance of the QHSR report, stating that the QHSR report be issued “not later than 60 days after the date of the submission of the President’s budget for the fiscal year after the fiscal year in which a quadrennial homeland security review is conducted.” Pub. L. No. 117-263, 7141(a)(3)(A), 136 Stat. 2395, 3652 (2022) (codified as amended at 6 U.S.C. 347(c)(1)). Per statute, the President is to submit the President’s Budget by the first Monday in February. Pub. L. No. 101-508, 13112(a)(4), 104 Stat. 1388-1, 1388-608 (1990) (codified as amended at 2 U.S.C. 631). The Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993 as amended by the GPRA Modernization Act of 2010 requires agencies to make their strategic plans publicly available no later than the first Monday in February after the commencement of a Presidential term. Pub. L. No. 111-352, 2, 124 Stat. 3866, 3866 (2011) (codified as amended at 5 U.S.C. 306). The letters below the timeline stand for the months in the fiscal year in the following order: O-October, N-November, D-December, J-January, F-February, M-March, A-April, M-May, J-June, J-July, A-August, S-September.

Officials from four of the eight DHS components we interviewed cited challenges related to the timing of the QHSR report and DHS’s strategic plan that may have impacted their use of the QHSR. For example:

· Federal Emergency Management Agency officials stated that they use either the DHS Strategic Plan or QHSR report to inform their strategic planning, depending on which is more current. Since the QHSR report was not released by the end of budget development, the Federal Emergency Management Agency relied on other department planning guidance documents for the development of its fiscal year 2025 budget.

· Additionally, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency officials stated that they do not use the QHSR report, primarily because the timing of the QHSR makes it hard to use in their component strategic planning.

DHS has consistently not issued the QHSR on time, as shown in figure 4. As noted previously, DHS does not have processes or procedures for how and when to conduct the QHSR. Developing and documenting processes and procedures for conducting the QHSR—including relevant steps and associated time frames in the QHSR process—could improve DHS’s ability to meet statutory time frames. Doing so could help DHS use timely information in planning how to address constantly evolving homeland security threats.

Other Federal and External Stakeholder Engagement in and Use of the QHSR

Other federal and external stakeholders we interviewed described limited engagement with DHS in the development of the QHSR as well as limited focus on stakeholder efforts and homeland security roles in the QHSR report, which may be affecting stakeholders’ engagement in and use of the QHSR report. For example, other federal and external stakeholders we contacted described their involvement with DHS as limited, with some noting that they did not meet with DHS prior to the report being drafted.

DHS officials told us they consulted with three categories of stakeholders while conducting the QHSR, consistent with the requirements of the 9/11 Commission Act: (1) internal DHS stakeholders; (2) other federal stakeholders; and (3) external stakeholders, including, but not limited to, state agencies or private sector representatives. DHS provided us with multiple lists of the stakeholders and dates when consultation occurred. However, DHS had no documentation on the substance of information discussed or how it was incorporated into the QHSR report. This raises questions about how the input, if any, from stakeholders, including other federal and external stakeholders, informed the QHSR and thus the extent to which these stakeholders perceive the subsequent report as applicable to them and useful in managing their missions.

Furthermore, as discussed previously, DHS’s stated approach for conducting the QHSR indicates that stakeholder consultation is to occur prior to drafting the QHSR report. However, DHS’s consultation with other federal stakeholders it is statutorily required to consult consisted of circulating its draft of the QHSR report.[29] DHS could not provide evidence of comments or other documentation that showed how the consultations with these stakeholders informed the 2023 QHSR.

We interviewed three of the eight other federal stakeholders DHS is statutorily required to consult, and all three stated that they received the draft QHSR report; however, they did not meet with DHS prior to receiving the draft.[30] For example, Department of Defense officials stated that they were not aware of any meeting to discuss stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities in the QHSR process; however, they received the draft QHSR report for review. DHS and officials from the remaining five other federal stakeholders could not identify staff within these agencies who participated in the QHSR or the dates of their participation. The list DHS provided to us of the federal stakeholders it consulted, with dates of the consultations, did not include three of the eight other federal stakeholders DHS is statutorily required to consult. Officials stated that they could not confirm if DHS consulted with the stakeholders since officials who conducted the consultations are no longer with the agency.

In addition to other federal stakeholders, DHS officials said that they also solicited QHSR input from external stakeholders, such as state and local partners, industry groups, and other non-governmental organizations, through meetings in late 2021. We randomly selected 11 of the 45 external stakeholders DHS identified as having consulted with, and five of the 11 stated that they did not recall participating in the QHSR or had limited insight into the process.[31] Further, three of the 11 stakeholders were not aware of a QHSR stakeholder participation meeting prior to us contacting them. DHS could not provide agendas or any record of these meetings to show how external stakeholder input was collected and incorporated into the 2023 QHSR report. Without insight into the process, other federal and external stakeholders may not be positioned to use the QHSR.

Our past work on the QHSR also identified challenges related to stakeholder collaboration. Specifically, we previously found in April 2016 that DHS did not provide sufficient feedback opportunities for stakeholders in conducting the QHSR.[32] We recommended that DHS identify and implement processes and clear roles and responsibilities that ensure the stakeholder process is interactive. As of April 2024, DHS has not taken action to implement this recommendation. Similarly, in September 2011, we found that DHS did not provide enough time for stakeholder engagement. We recommended that DHS provide more time for consulting with stakeholders during the QHSR, which DHS did not implement going into the 2014 QHSR.[33]

In addition to the lack of clarity on stakeholders’ involvement in the QHSR, the resulting QHSR report makes limited references to other federal stakeholders and their roles in homeland security, which could also be affecting how or whether these stakeholders use the QHSR report to execute their homeland security roles and to support DHS. As stated in the 2023 QHSR report, DHS cannot accomplish its missions alone. According to the report, DHS’s success depends on the strength of mutually beneficial partnerships with other federal, state, local, and tribal governments as well as the private sector. The report provides examples of DHS’s partnership with these stakeholders, however, the information on the stakeholders’ contributions to the partnership is limited.

For example, the QHSR report states that DHS will continue to operate with other federal stakeholders such as the (1) Department of Health and Human Services to provide medical capabilities and care and facilitate placement of unaccompanied children, (2) Department of Justice’s Bureau of Prisons to provide transportation capabilities and the Executive Office for Immigration Review to reduce the immigration court backlog, and (3) Department of Defense to provide detection and monitoring capabilities and assistance with contracting. Additional information on the nature of these partnerships and each agency’s role and responsibilities in them is not discussed in the 2023 QHSR report. For example, as mentioned earlier in this report, the QHSR report lacks information on the budget, which would include any resources required from each agency to implement these partnerships. Such information, together with improved consultation with these federal stakeholders, could help ensure these stakeholders understand their expected roles and responsibilities for executing the homeland security missions in partnership with DHS.

Officials from one of the eight DHS operational components we interviewed stated that the QHSR report is not focused on the efforts of the entire homeland security enterprise.[34] They questioned where in the QHSR report the input from other stakeholders falls. One official stated that if the intent of the QHSR is to be a quadrennial effort that looks at the homeland security enterprise more broadly, then the department should consider including actions that support that enterprise rather than focusing only on the department’s efforts. Six of the 14 external stakeholders and other federal agencies we interviewed or solicited written responses from said that they do not use the QHSR or questioned the usefulness of the QHSR report.[35]

According to Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should communicate with and obtain quality information from external parties which can be done using established reporting lines through open, two-way communication.[36] Additionally, the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 has new QHSR requirements for engaging with additional stakeholders, such as the Homeland Security Advisory Council and the Homeland Security Science and Technology Advisory Committee.[37] These requirements also include documenting stakeholder consultations, including all feedback submitted during the process and how that feedback informed the QHSR.[38]

As discussed earlier in this report, DHS does not have processes and procedures for conducting the QHSR. Developing and documenting processes and procedures for engaging stakeholders, including when and how to engage them, may help ensure that DHS solicits and incorporates meaningful input from all stakeholders. It could help ensure that all stakeholders understand their expected roles and responsibilities for executing the homeland security missions in partnership with DHS. Doing so could help ensure that the QHSR report reflects a comprehensive examination of the homeland security strategy of the nation.

Conclusions

Given the varying and constantly evolving homeland security threats to the nation, it is vital that DHS regularly examine the nation’s homeland security strategy and missions. To that end, the QHSR is supposed to comprehensively examine the nation’s homeland security strategy. DHS has issued three QHSR reports to date in which it identified DHS’s missions and objectives and revised those missions and objectives, as appropriate.

We previously reviewed the first two QHSRs and identified issues—such as a lack of documentation and limited stakeholder engagement—that continued to plague the most recent QHSR, and which DHS has yet to address. As with DHS’s 2014 QHSR report, DHS made changes to its mission objectives, and it also added a sixth mission to the 2023 QHSR report. However, it did not document the methodology for QHSR risk assessments—as we previously recommended—that led to those mission changes. In each of our reviews of the QHSR, we have found that DHS did not fully meet statutory requirements. This included requirements for issuing the QHSR by the statutorily required time frame which DHS has never done. Without meeting these deadlines, the report will have limited potential to inform the department’s strategic planning in a timely manner. In addition to challenges related to the timing of the QHSR report, stakeholders cited limited engagement with DHS in the development of the QHSR as well as limited focus on stakeholder efforts and homeland security roles in the QHSR report, which may be affecting stakeholders’ engagement in and use of the QHSR report.

Developing and documenting processes and procedures for conducting the QHSR—including processes and procedures for conducting risk assessments, for meeting all statutorily required time frames, and for when and how to engage stakeholders in the QHSR process—could better position DHS to fully meet all QHSR statutory requirements. Doing so could also help DHS use timely information in planning how to address the constantly evolving homeland security threats and to solicit and incorporate meaningful input from all stakeholders to ensure that DHS and stakeholders can effectively use the QHSR for executing their homeland security roles.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to the Secretary of Homeland Security:

The Secretary of Homeland Security should develop and document processes and procedures for conducting the QHSR to meet all statutory requirements, including those for (1) QHSR risk assessments and (2) required time frames. (Recommendation 1).

The Secretary of Homeland Security should develop and document processes and procedures for engaging stakeholders, including when and how to engage stakeholders, in the QHSR. (Recommendation 2).

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Departments of Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Justice, State, and the Treasury and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. DHS provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix II. The Departments of Defense, Health and Human Services, Justice and State did not have any comments on the report. The other agencies did not provide any comments on the report.

In its comments, DHS concurred with the two recommendations. DHS noted that it plans to develop a program management plan to document processes and procedures for conducting the QHSR, to include risk assessments, required time frames, and stakeholder engagement. If fully implemented, this should address the intent of both recommendations and better position DHS to meet all QHSR statutory requirements and incorporate input from all stakeholders moving forward. DHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the Secretaries of Defense, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, State, and the Treasury; the Attorney General; the Director of National Intelligence; and appropriate congressional committees. In addition, this report will be available at no charge on the GAO Web site at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at curriec@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. Key contributors to this report are listed in appendix III.

Chris Currie

Director, Homeland Security and Justice Issues

List of Requesters

The Honorable Mark E. Green, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable J. Luis Correa

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Border Security and Enforcement

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Shri Thanedar

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Oversight, Investigations and Accountability

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Glenn F. Ivey

House of Representatives

The Honorable Michael T. McCaul

House of Representatives

The Honorable Scott Perry

House of Representatives

The Honorable Bonnie Watson Coleman

House of Representatives

The Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 included 21 requirements for the QHSR and associated report.[39] The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) met 11, partially met eight, and did not meet two of these requirements through the 2023 QHSR and report, as shown in table 3.

The act provides that each such review “shall be a comprehensive examination of the homeland security strategy of the Nation, including recommendations regarding the long-term strategy and priorities of the Nation for homeland security and guidance on the programs, assets, capabilities, budget, policies, and authorities of the Department.”[40] The act includes 11 requirements related to the scope, consultation, and content of the review (review requirements). To assess the extent to which DHS met these review requirements, we reviewed all relevant evidence, including DHS documentation and interviews with DHS officials and QHSR stakeholders.

The act further requires that DHS submit to Congress a report regarding the QHSR and identifies specific elements the report is to include. For the 10 reporting requirements, we limited our assessment to the published QHSR report because the act requires these requirements to be addressed therein.

DHS officials agreed with our overall assessment but stated that some of the requirements we found as not fully met were because of issues outside of DHS’s control. For example, in response to deadline requirements for the report and review, DHS officials stated that it was impractical to issue a QHSR without the White House first issuing its National Security Strategy because that strategy informs the goals for agencies in national security, such as DHS. Additionally, DHS officials stated that since the QHSR is a political document—that is, it is a document that derives direction from the White House and supports the presidential administration’s priorities—there are other added other complexities that impact the timeliness of the review and subsequent report. We understand the complexity of the process, but our assessment of DHS actions found that more can be done to ensure the next QHSR is timely.

Table 3: GAO’s Assessment of the 9/11 Commission Act Requirements in Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) 2023 Quadrennial Homeland Security Review (QHSR)a

|

QHSR requirement |

GAO assessment |

GAO rationale |

|

(a)(1)Quadrennial reviews required—In fiscal year 2009, and every 4 years thereafter, the Secretary shall conduct a review of the homeland security of the Nation (in this section referred to as a ‘‘quadrennial homeland security review’’). |

Partially Metb |

The act requires DHS to conduct the most recent review during fiscal year 2021. The DHS Secretary sent a memo to the DHS Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans (Office of Policy) directing the agency to start the QHSR. That memo was dated July 30, 2021. DHS officials told us that the office started the process in 2021 through stakeholder meetings and reviewing documents. Overall, the memo notes that there was consideration of the QHSR within the designated fiscal year, but it is unclear the extent to which the review was completed within that fiscal year. The report was not issued until 2023. |

|

(a)(2) Scope of reviews—Each quadrennial homeland security review shall be a comprehensive examination of the homeland security strategy of the Nation, including recommendations regarding the long-term strategy and priorities of the Nation for homeland security and guidance on the programs, assets, capabilities, budget, policies, and authorities of the Department. |

Metc |

In general, the QHSR provides a comprehensive discussion of the six missions with their associated objectives and goals. It includes details on various programs across the DHS enterprise, describing their current operations and plans for future growth. DHS emphasizes the need for assets—such as personnel, physical infrastructure, and technology—to conduct its critical missions. The report states that the components’ roles and responsibilities in specific mission areas position them to address mission-specific capabilities, such as law enforcement against transnational organized crime. Additionally, the QHSR discusses updates to certain policies to ensure legal compliance and alignment with best practices, as well as descriptions of current authorities. It also discusses areas where expanded authorities may be necessary to meet the developing mission requirements. Finally, the QHSR explains that its strategic guidance and updated mission framework will inform existing processes for translating priorities into resources, including the DHS Strategic Plan and annual budget development process, to ensure mission priorities inform funding decisions. |

|

QHSR requirement |

GAO assessment |

GAO rationale |

|

(a)(3)(C) Consultation— The Secretary shall conduct each quadrennial homeland security review under this subsection in consultation with (A) the heads of other Federal agencies, including the Attorney General, the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of Agriculture, the Secretary of Energy, and the Director of National Intelligence; (B) key officials of the Department, including the Under Secretary for Strategy, Policy, and Plans; (C) and other relevant governmental and nongovernmental entities, including State, local, and tribal government officials, members of Congress, private sector representatives, academics, and other policy experts. |

Partially metd |

DHS officials stated that they did consult all required federal agencies. However, DHS could not provide evidence that they consulted the Secretary of Agriculture, the Secretary of Energy, or the Attorney General during the QHSR. DHS provided evidence of contacting all other required federal agencies through meetings and/or draft comment procedures. DHS consulted multiple stakeholders within the department, including members of the Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans and all DHS components. Finally, DHS consulted multiple external stakeholders including congressional committees, academics, private sector representatives, and other policy experts. DHS consulted with representatives from state governments and tribal governments as well as organizations representing local governments. |

|

(a)(4) Relationship with Future Years Homeland Security Program—The Secretary shall ensure that each review conducted under this section is coordinated with the Future Years Homeland Security Program required under section 874. |

Met |

DHS provided a list of documents and assessments it used as the basis for drafting the 2023 QHSR. Among these were the Future Years Homeland Security Program reports for fiscal years 2021–2025 and fiscal years 2022–2026. While the QHSR does not directly reference either Future Years plan, QHSR missions and objectives are supported by the programs and related resource allocations outlined in the Future Years plans. |

|

(b)(1) Contents of review—In each quadrennial homeland security review, the Secretary shall delineate and update, as appropriate, the national homeland security strategy, consistent with appropriate national and Department strategies, strategic plans, and Homeland Security Presidential Directives, including the National Strategy for Homeland Security, the National Response Plan, and the Department Security Strategic Plan. |

Met |

DHS reviewed the strategies and documents listed in the requirement as part of the 2023 review process. DHS provided a list of documents which includes these plans as key reference documents. Additionally, DHS added mission 6 (Combat Crimes of Exploitation and Protect Victims) to the 2023 QHSR, showing that DHS determined this mission was a necessary update to the QHSR to encompass the department’s work in this area. |

|

(b)(2) –Contents of review—In each quadrennial homeland security review, the Secretary shall outline and prioritize the full range of the critical homeland security mission areas of the Nation. |

Partially met |

The 2023 QHSR lays out the national homeland security strategy through the six homeland security mission goals and objectives. According to DHS officials, they developed and reaffirmed these through the review process, including through consultation with stakeholders and other activities. However, department officials did not prioritize the missions outlined in the QHSR in the review or subsequent budget process. |

|

QHSR requirement |

GAO assessment |

GAO rationale |

|

(b)(3) Contents of review—Describe the interagency cooperation, preparedness of Federal response assets, infrastructure, budget plan, and other elements of the homeland security program and policies of the Nation associated with the national homeland security strategy, required to execute successfully the full range of missions called for in the national homeland security strategy described in paragraph (1) and the homeland security mission areas outlined under paragraph (2). |

Partially met |

Most of the elements of this requirement, such as the interagency cooperation, preparedness of federal response assets, and infrastructure, of this requirement were addressed in stakeholder meetings through an online forum or interviews and were addressed in the 2023 QHSR (see QHSR requirement (c)(2)(D)). DHS asked stakeholders via interviews about their priorities and if the priorities were adequately resourced. However, this does not constitute a budget plan discussion nor was there additional evidence describing a budget plan. |

|

(b)(4) Contents of review—In each quadrennial homeland security review, the Secretary shall identify the budget plan required to provide sufficient resources to successfully execute the full range of missions called for in the national homeland security strategy described in paragraph (1) and the homeland security mission areas outlined under paragraph (2). |

Not met |

The 2023 QHSR, like previous QHSRs, does not identify a budget plan for executing the full range of homeland security strategy missions. The report makes references to including the new 6th mission—Combat Crimes of Exploitation and Protect Victims—in its budget requests, however, the budget plan for this mission is not identified in the 2023 QHSR or in the Future Homeland Security Program plan for fiscal years 2022 through 2026, which officials said they used for drafting the QHSR. For example, referencing the addition of the sixth mission, the 2023 QHSR states that work related to the mission “will continue to grow and its identification as a full mission of the department lays the groundwork for necessary enhancements, including planning, increased budget requests, operational cohesion, and partnerships.” Although, this references a potential increased budget request, it does not provide sufficient detail to be considered a budget plan. |

|

(b)(5) Contents of review—In each quadrennial homeland security review, the Secretary shall include an assessment of the organizational alignment of the department with the national homeland security strategy referred to in paragraph (1) and the homeland security mission areas outlined under paragraph (2). |

Met |

The 2023 QHSR provides information on the organizational alignment of the department (see QHSR requirement (c)(2)(E)). In addition, officials from multiple DHS components told us that, through the review process, they understood the missions they were aligned with or responsible for. |

|

(b)(6) Contents of review In each quadrennial homeland security review, the Secretary shall review and assess the effectiveness of the mechanisms of the department for executing the process of turning the requirements developed in the quadrennial homeland security review into an acquisition strategy and expenditure plan within the department. |

Partially met |

The 2023 QHSR includes a limited discussion on reviewing and assessing the effectiveness of the mechanisms for turning certain QHSR requirements into an acquisition strategy. For example, the 2023 QHSR acknowledges that procurement and acquisition processes must be based on analysis, leverage the scale of the department, and have strong alignment with strategy. However, the 2023 QHSR lacks discussion of turning the requirements into an expenditure plan. |

|

(c)(1) Reporting in general—Not later than December 31 of the year in which a quadrennial homeland security review is conducted, the Secretary shall submit to Congress a report regarding that quadrennial homeland security review. |

Not met |

DHS performed the review in 2021 and 2022 but did not release the report until April of 2023. |

|

QHSR requirement |

GAO assessment |

GAO rationale |

|

(c)(2)(A) Reporting: Contents of report—Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include the results of the quadrennial homeland security review. |

Met |

Although the 2023 QHSR report does not address all the reporting segments required within the 9/11 Commission Act (see below), it reports on DHS’s effort to conduct the homeland security review as well DHS’s role in and future goals for homeland security. The document addresses threats to homeland security, DHS’s work and collaborations for mitigating identified threats, and DHS’s future objectives to continue to meet threats. |

|

(c)(2)(B) Reporting: Contents of report—Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include a description of the threats to the assumed or defined national homeland security interests of the Nation that were examined for the purposes of that review. |

Met |

DHS met this requirement for the 2023 QHSR report by discussing threats to homeland security, including domestic terrorism, climate change, transnational criminal organizations, cybercrime, foreign threats, and human trafficking. These threats were each related to one of the national homeland security missions identified during the review. |

|

(c)(2)(C) Reporting: Contents of report—Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include the national homeland security strategy, including a prioritized list of the critical homeland security missions of the Nation. |

Partially met |

The 2023 QHSR report lays out the national homeland security strategy through the six homeland security mission goals and objectives. In terms of a prioritized list of the critical missions of the Nation, the QHSR report does not rank the list in order of importance. Instead, it includes language that provides a forward-looking understanding of what DHS intends to focus on within the missions. |

|

(c)(2)(D) Reporting: Contents of report—Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include a description of the interagency cooperation, preparedness of Federal response assets, infrastructure, budget plan, and other elements of the homeland security program and policies of the Nation associated with the national homeland security strategy, required to execute successfully the full range of missions called for in the applicable national homeland security strategy referred to in subsection (b)(1) and the homeland security mission areas outlined under subsection (b)(2). |

Partially met |

The 2023 QHSR report addresses most of the elements of this requirement including interagency cooperation, preparedness of Federal response assets, and infrastructure, as well as some discussion of other elements of the homeland security program and policies of the Nation. For example, as related to interagency cooperation, the QHSR report describes that DHS will continue to operate in a coordinated fashion with federal partners such as Health and Human Services to provide medical capabilities and care and facilitate placement of unaccompanied children, among other interagency efforts. Further, regarding preparedness of federal response assets, the QHSR report describes how DHS is working to advance climate resilience and further increase equity in its preparedness and response efforts as underserved communities are disproportionately impacted by extreme heat. However, the QHSR report has a limited discussion of the budget and does not lay out the budget plan required to successfully execute the full range of missions. |

|

(c)(2)(E) –Reporting: Contents of report—Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include an assessment of the organizational alignment of the department with the applicable national homeland security strategy referred to in subsection (b)(1) and the homeland security mission areas outlined under subsection (b)(2), including the department’s organizational structure, management systems, budget and accounting systems, human resources systems, procurement systems, and physical and technical infrastructure. |

Partially met |

The 2023 QHSR report provides information on the organizational alignment and organizational structure of the department as well as discussion of physical and technical infrastructure, human resources, and procurement systems. For example, Appendix B of the 2023 QHSR report defines the operational Components of the department and identifies the specific homeland security mission areas relevant to that component. However, the 2023 QHSR report does not provide any discussion of management or budget and accounting systems alignment. There is not a description or definition of “systems” or “mechanisms” by which the budget and accounting activities or management activities are accomplished. DHS officials told us that these systems are alluded to in the “Strengthening the Enterprise” section, but they did not provide actual examples of how that is achieved. |

|

QHSR requirement |

GAO assessment |

GAO rationale |

|

(c)(2)(F) –Reporting: Contents of report—Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include a discussion of the status of cooperation among Federal agencies in the effort to promote national homeland security. |

Met |

The QHSR report provides descriptions of cooperation between DHS and other federal and non-federal agencies for homeland security that meet each of the homeland security missions. As an overarching example, the 2023 QHSR notes that DHS is fundamentally a department of partnerships and the department’s success depends on the strength of these partnerships. As such, the 2023 QHSR report explains that the department pursues mutually beneficial partnerships across federal agencies and interfaces with these entities daily, relying on their counsel and expertise, communicating departmental priorities and initiatives in real time, and accessing new technologies and ideas. |

|

(c)(2)(G) Reporting: Contents of report—Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include a discussion of the status of cooperation between the Federal Government and State, local, and tribal governments in preventing terrorist attacks and preparing for emergency response to threats to national homeland security. |

Met |

The 2023 QHSR report provides a statement on the partnerships between various sectors, including those listed in this requirement. In the report, it states, “Our success depends on the strength of these partnerships as we cannot accomplish our missions alone.” In addition, the 2023 QHSR report also provides examples of collaboration between state, local, and tribal governments including, but not limited to, DHS partnerships with state and local governments, law enforcement organizations, international nongovernmental organizations, and non-profits to conduct border management, immigration processing, and resettlement operations along the southwest border. |

|

(c)(2)(H) –Reporting: Contents of report—Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include an explanation of any underlying assumptions used in conducting the review. |

Met |

The QHSR report does not explicitly identify the underlying assumptions, but there is discussion of general strategic challenges that shape the homeland security strategy outlined in the 2023 QHSR. For example, the 2023 QHSR report notes development of the Homeland Security mission—Combat Crimes of Exploitation and Protect Victims—was added in light of the prevalence and severity of such crimes including human trafficking, labor exploitations, and child exploitation. The 2023 QHSR report further describes that this mission relates not only to DHS’s ongoing work to raise awareness of these threats and provide training to those who encounter victims of these crimes, but also the necessary enhancements to combat such crimes. |

|

(c)(2)(I) Reporting: Contents of report— Each report submitted under paragraph (1) shall include any other matter the Secretary considers appropriate. |

Met |

This provision does not require the report to cover any particular item, so this requirement is met even if no additional items are incorporated. |

|

(c)(3) –Public availability—The Secretary shall, consistent with the protection of national security and other sensitive matters, make each report submitted under paragraph (1) publicly available on the Internet website of the department. |

Met |

The QHSR report is available on the DHS public website. |

Source: GAO. | GAO‑25‑107269

aPub. L. No. 110-53, 2401(a), 121 Stat. 266, 543-545 (2007) (codified as amended at 6 U.S.C. 347). The statutory requirements for the QHSR include both review and reporting components. For the purposes of this report, we use the term “QHSR report” when specifically discussing the report itself, and “QHSR” to refer to the review period, which includes developing the report.

bWe determined a requirement was “met” if DHS addressed all elements of the requirement, “partially met” if DHS addressed some but not all elements of the broader requirement, and “not met” if DHS addressed none of the elements of the requirements.

cFor the purposes of this report, “guidance” on the identified items was considered “met” if the QHSR mentioned or described the particular item.

dFor the purposes of this report, consultation was considered met if the agency provided documentation that they contacted the identified stakeholders (federal agencies, internal DHS offices, and State, Local, Tribal and Territorial partners) via email or a meeting.

GAO Contact:

Chris Currie, CurrieC@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgements:

In addition to the contacts named above, Alana Finley, (Assistant Director), Edith Sohna (Analyst-in-Charge), Christine Catanzaro, Michele Fejfar, Taylor Gauthier, Eric Hauswirth, and Mary Turgeon made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Department of Homeland Security, Office of Intelligence & Analysis, Homeland Threat Assessment 2025 (Washington, D.C.: October 2024) and Homeland Threat Assessment 2024 (Washington, D.C.: September 2023).

[2]Pub. L. No. 110-53, § 2401(a), 121 Stat. 266, 543-546 (2007) (codified as amended at 6 U.S.C. § 347). The statutory requirements for the QHSR include both review and reporting components. For the purposes of this report, we use the term “QHSR report” when specifically discussing the report itself, and “QHSR” to refer to the review period, which includes developing the report.