TRACKING THE FUNDS

Agencies Continued Executing FY 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/ Congressionally Directed Spending Provisions

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-107274

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107274. For more information, contact Jeff Arkin at (202) 512-6806 or arkinj@gao.gov or Allison Bawden at (202) 512-3841 or bawdena@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107274, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

TRACKING THE FUNDS

Agencies Continued Executing FY 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending Provisions

Why GAO Did This Study

The Consolidated Appropriations Acts, 2022 and 2023, and accompanying joint explanatory statements, together designated $24.4 billion for 12,196 provisions at the request of Members of Congress. These provisions designate a particular recipient—such as a nonprofit organization or local government—to receive an amount of funds to use for a specific project. These provisions are called “Community Project Funding” in the House of Representatives and “Congressionally Directed Spending” in the U.S. Senate.

The joint explanatory statements accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Acts, 2022 and 2023, include provisions for GAO to review agencies’ implementation of CPF/CDS contained in the acts. This report describes the amount of funds for these specific provisions that have been recorded as obligated and outlayed as of the end of fiscal year 2023, as reported by the 19 agencies responsible for distributing the funds.

GAO collected budget execution data—obligations and outlays—along with completion status and data quality information from each of the relevant agencies. These data reflect agencies’ recorded obligations and outlays as of the end of fiscal year 2023. GAO also interviewed agency officials about their plans and processes for implementing the provisions.

What GAO Found

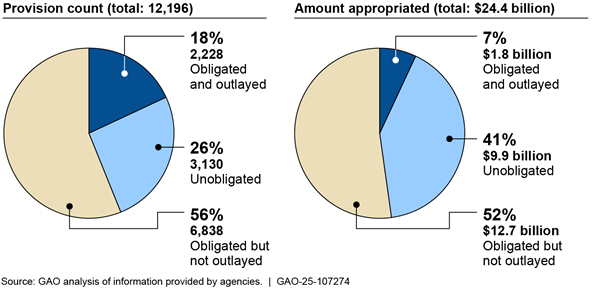

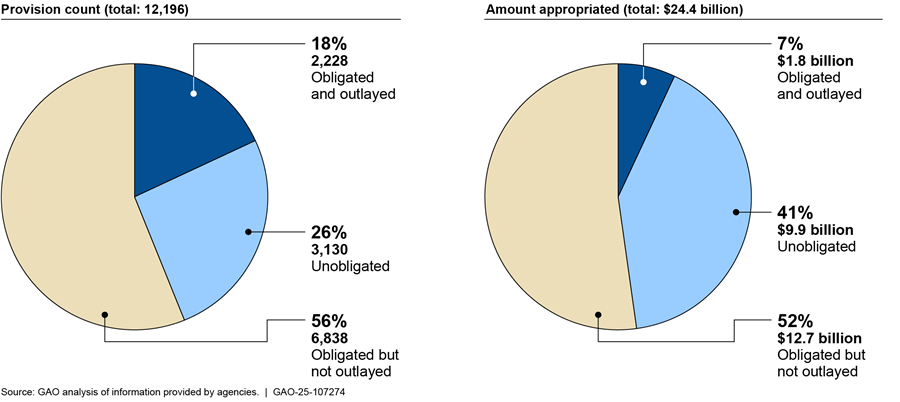

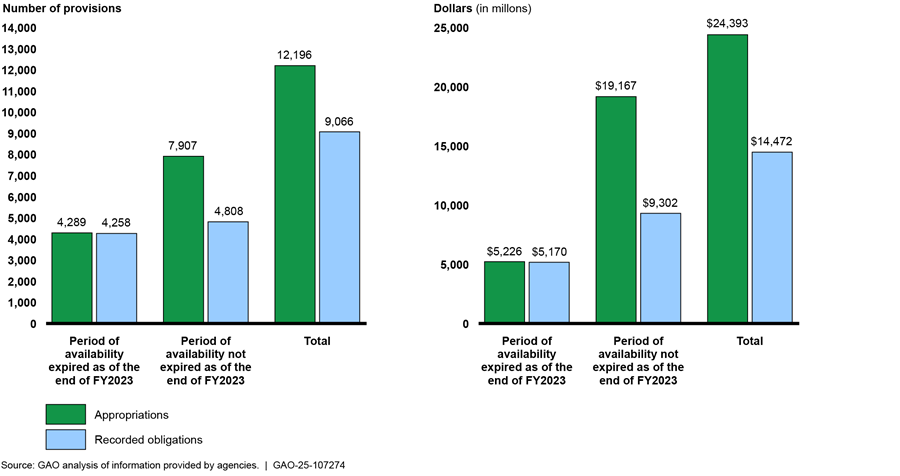

As of the end of fiscal year 2023, agencies recorded obligations (e.g., took an action, such as signing a contract or awarding a grant, that created a legal duty to pay) toward 74 percent of the fiscal year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending (CPF/CDS) projects. Agencies made outlays (i.e., disbursed cash) toward 18 percent of these projects. Of the $24.4 billion in total funding for these provisions, agencies recorded obligations for 59 percent and outlays for 7 percent.

Agency-Recorded Obligations and Outlays for Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending, End of Fiscal Year 2023

Note: GAO included provisions for those agencies that recorded obligations for any amount of designated funds as obligated in this count.

Of the 19 agencies responsible for distributing the funds, 10 agencies recorded obligations for at least 90 percent of their projects and nine recorded obligations for at least 90 percent of their designated funds. Agencies recorded obligations toward more than half of the projects within all states (48 states plus the District of Columbia) and three of the four U.S. territories where projects are located. Agencies also recorded obligations for 18 of the 20 projects located across multiple states.

For provisions with funding that expired as of the end of fiscal year 2023, agencies recorded obligations for 99 percent of these projects (4,258), representing 99 percent of the designated funds ($5.17 billion), before the funding expired. An agency may not use the expired funds to incur new obligations but may use the funds to liquidate legally incurred obligations.

Agencies did not record any obligations for 31 provisions ($26.2 million) with designated funds that expired at the end of fiscal year 2023 for various reasons. For example, according to agency officials, some recipient organizations had closed, declined the funding, or did not follow agency application processes.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CPF/CDS |

Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending |

|

FY |

Fiscal year |

|

ONDCP |

Office of National Drug Control Policy |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 21, 2024

Congressional Committees

As part of recent appropriations acts, Members of Congress could request to designate funding through legislative provisions for specific projects in their communities. These provisions designate certain amounts of funds for particular recipients, such as a nonprofit organization or local government, to use for specific projects. The provisions are called “Community Project Funding” in the House of Representatives and “Congressionally Directed Spending” in the U.S. Senate.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 designated $15.3 billion for 7,233 such provisions and the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 designated $9.1 billion for 4,963 provisions. Thus, a total of $24.4 billion for 12,196 provisions was designated across both years.[1] Nineteen federal agencies are administering these funds, which go toward projects with purposes such as education, health care, and transportation.[2]

The joint explanatory statements accompanying the Consolidated Appropriations Acts, 2022 and 2023, include provisions for us to review agencies’ implementation of Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending (CPF/CDS).[3] This report describes the amount of funds designated by the fiscal year 2022 and 2023 CPF/CDS provisions that have been recorded as obligated and outlayed as of the end of fiscal year 2023 and as reported by the 19 agencies responsible for distributing the funds.[4] We are also publishing an online dataset to accompany this report.[5]

We used data collection instruments to obtain information from the 19 agencies on the obligations and outlays they had recorded as of the end of fiscal year 2023 for each provision for which funds were appropriated in fiscal years 2022 and 2023.[6] We performed manual and programmatic checks on the completeness, reasonability and logic of the data, such as checking for duplicate records. We followed up with agencies in the instances in which we found inconsistencies with the reported data and resolved the issues. However, we did not check the obligations and outlay data against agency records. Therefore, the obligations and outlay amounts included in this report and our online dataset are reported according to the agencies’ data.

To help assess the reliability of the agencies’ data, all the agencies that submitted data also responded to standardized data quality questions. None of the agencies’ responses raised any issues of concern related to the completeness, accuracy, timeliness, or usability of the data within the scope of our review.

Finally, most agencies used their financial systems to provide the obligation and outlay data we requested.[7] To help understand potential broader financial management data quality issues within each agency, we reviewed the independent auditor’s reports, where available, on each agency’s fiscal year 2023 financial statement. These reports include examination of the agency’s internal controls over financial reporting and compliance with selected provisions of applicable laws, regulations, contracts, and grant agreements.[8] Where applicable, we also reviewed auditors’ reports on whether each agency’s financial management system complied substantially with the three requirements of the Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996.[9]

We identified six agencies that either had material weaknesses in financial management or a significant deficiency in grants management. We asked these agencies how these issues affected the accuracy and completeness of their data. Officials from all six agencies stated that these issues had no effect on the data they provided. We did not independently evaluate how these issues may specifically affect the obligation and outlay data we collected from agencies. We found the data to be reliable for the purpose of reporting the status of agency-reported obligations and outlays for the funds designated for these projects.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Congress provides budget authority to federal agencies to incur financial obligations through annual appropriations acts or other legislation. See table 1 for key terms and definitions in the budget process.

|

Budget term |

Definition |

|

Appropriation |

· Budget authority to incur obligations and to make payments from the Treasury for specified purposes. · Appropriations do not represent cash actually set aside in the Treasury for purposes specified in a given appropriation act; they represent amounts that agencies may obligate during the periods of time specified in the respective appropriation acts. |

|

Obligation |

· An obligation is a definite commitment that creates a legal liability on the part of the federal government for the payment of goods and services ordered or received, or a legal duty on the part of the United States that could mature into a legal liability by virtue of actions on the part of the other party beyond the control of the United States. Payment may be made immediately or in the future. · An agency incurs an obligation, for example, when it places an order, signs a contract, awards a grant, purchases a service, or takes other actions that require the government to make payments to the public or from one government account to another. |

|

Outlay |

· An outlay occurs, for example, upon the issuance of checks, disbursement of cash, or electronic transfer of funds made to liquidate a federal obligation. · Outlays during a fiscal year may be for payment of obligations incurred in prior years (prior-year obligations) or in the same year. |

|

Period of availability |

· When Congress appropriates funds, it specifies the period during which the funds are available to the agency to incur new obligations, referred to as the period of availability. Budget authority can be provided as one-year (available for obligation only during the specific year in which the funds were appropriated), multiple or multiyear (available for obligations for a fixed time in excess of one year), and no-year (available for obligation for an indefinite period of time). · In this period, the agency may incur new obligations for goods and services and charge them against the appropriation. |

|

Expired appropriations |

· At the end of the period of availability, the appropriation expires, meaning that the agency may not use the funds to incur new obligations. Generally, appropriated funds remain expired for 5 fiscal years after the period of availability ends.a An agency may use an expired appropriation to record, adjust, and make outlays toward prior obligations that were properly incurred. · An expired appropriation account generally closes at the end of the 5-year period, unless an exception is made in law, and any remaining funds are cancelled. The canceled funds may not be used for obligation or expenditure for any purpose. All remaining funds are returned to the general fund of the Treasury and are thereafter no longer available for any purpose. |

Source: GAO‑05‑734SP. | GAO‑25‑107274

aIn limited situations, an agency may have statutory authority that extends the expired fund stage beyond this 5-year window. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency has 7 years for multiyear funds appropriated for fiscal year 2001 and beyond. In some instances, the timeline that agencies set for recipients to spend funds through a grant agreement or contract may be shorter than the period of availability.

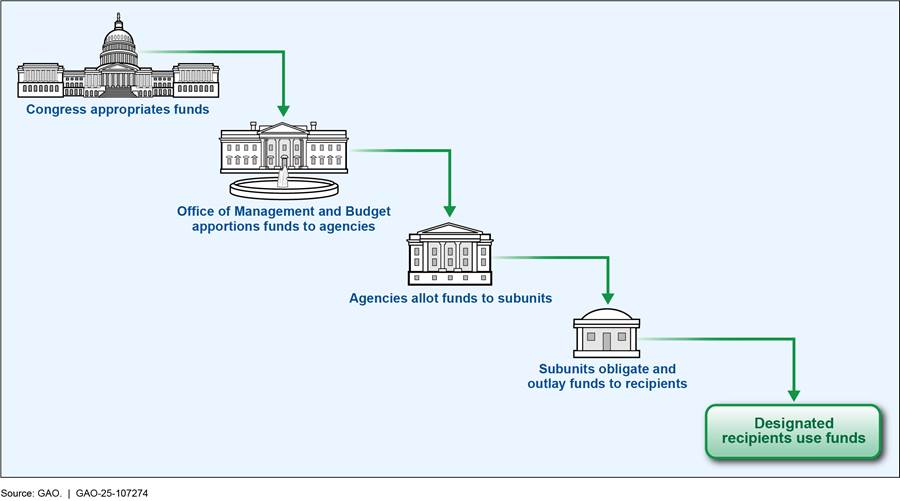

As figure 1 shows, after Congress appropriates funds, there are multiple steps before agencies can make funds available to recipients. Specifically, after Congress appropriates funds, the Office of Management and Budget apportions, or distributes, the funds to executive branch agencies.[10] Agencies then allot the apportioned funds within the account to program offices or subunits, consistent with the agency’s funds control system. Once the funds have been allotted, the program office or subunit can begin the process of making the funds available to recipients by first obligating the funds and then outlaying them.

The funds designated through CPF/CDS provisions are part of larger lump-sum appropriations that cover a number of programs, projects, or other items. Many of the provisions may be administered through the award of grants. Agencies that receive lump-sum appropriations for the purpose of executing a grant program might otherwise use a merit-based or competitive allocation process to distribute the funds. Because these provisions designate a specific recipient or project, agencies do not use such processes to award these funds. However, in some cases agencies have required the recipients of funds designated through these provisions to submit materials consistent with those required for competitive awards before obligating funds. The agencies use these materials in administering and overseeing the funds.

An agency may record an obligation only at the point of incurring an obligation, known as the obligational event. For grants, the point at which an agency incurs an obligation varies depending on the nature of the grant. In some situations, the agency incurs an obligation when it awards a grant. For other grants, the timing of the obligational event may be outside of the agency’s control. For example, in some circumstances, the agency may incur an obligation immediately when the appropriation for the grant becomes law.[11]

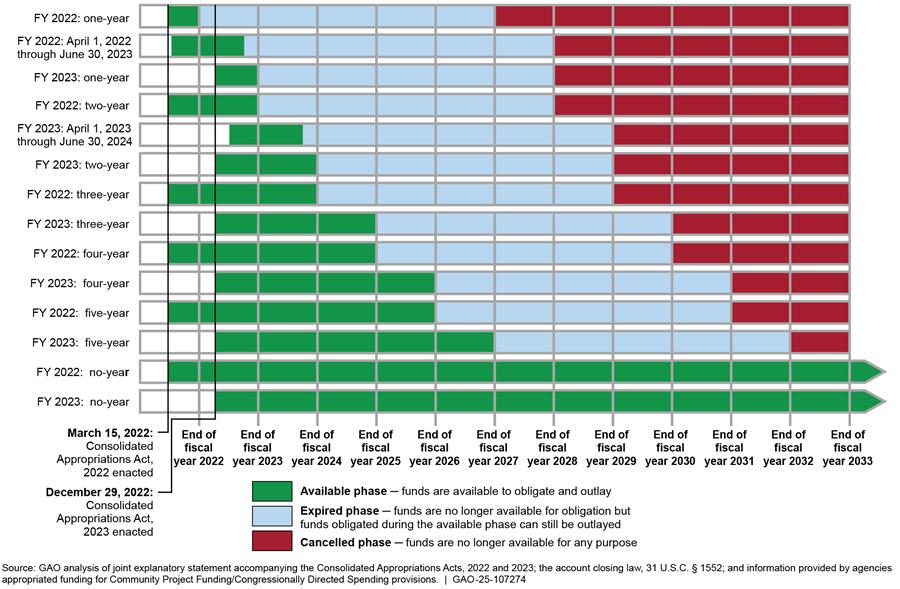

When Congress appropriated funds for the fiscal year 2022 and 2023 provisions, it specified a period of availability applicable to each appropriation from which funds were designated to specific recipients (see fig. 2). Generally, agencies may only obligate funds during the period in which they are available, after which the funds are expired.

Figure 2: Periods of Availability for Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending Provisions in the Consolidated Appropriations Acts, 2022 and 2023

Note: Obligations are actions that create a legal duty of the government for the payment of goods or services. Outlays are the disbursement of cash made to liquidate a federal obligation.

Through subsequent laws, Congress made technical corrections to 51 fiscal year 2022 and 2023 CPF/CDS projects.[12] In addition, as of May 2024, the Environmental Protection Agency made technical corrections to 83 of the fiscal year 2022 and 2023 CPF/CDS projects.[13] Most of these changes were technical corrections to the names of the CPF/CDS recipients, projects, or both.

Agencies Have Recorded Obligations for Most of the Provisions for Fiscal Years 2022 and 2023

As of the end of fiscal year 2023, the 19 agencies had recorded obligations toward 9,066 of the 12,196 fiscal year 2022 and 2023 projects (74 percent).[14] Agencies recorded outlays towards 2,228 of the projects (18 percent). Expressed in dollars, agencies recorded obligations for 59 percent of the $24.4 billion in designated funds, and outlays for 7 percent of the designated funds, as of the end of fiscal year 2023. See figure 3.

Figure 3: Agency-Recorded Obligations and Outlays for Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending, End of Fiscal Year 2023

Notes: We included provisions for those agencies that recorded obligations for either all or a portion of the designated funds as obligated in this count. Obligations are actions that create a legal duty of the government for the payment of goods or services. Outlays are the disbursement of cash made to liquidate a federal obligation.

As table 2 shows, agencies recorded obligations for nearly all the provisions designated with a one-year period of availability (99 percent of these provisions), and obligated nearly all funds available for these projects (99 percent). The obligation and outlay rates for designated funds with other periods of availability varied.

Table 2: Obligations and Outlays for Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending by Period of Availability, End of Fiscal Year 2023

Dollar amounts in millions, and percents of row totals are in parentheses

|

Period of availability |

Number of provisions |

Number of provisions with funds obligateda (percent) |

Total funds designated |

Amount obligated (percent) |

Amount outlayed (percent) |

|

One-year |

3,938 |

3,908 |

$4,914.0 |

$4,859.8 |

$642.8 |

|

15-Months |

422 |

173 |

355.0 |

137.6 |

10.7 |

|

Two-year |

373 |

286 |

448.6 |

348.8 |

33.1 |

|

Three-year |

154 |

69 |

595.2 |

166.4 |

25.0 |

|

Four-year |

3,578 |

2,895 |

7,288.0 |

5,053.7 |

90.6 |

|

Five-year |

216 |

104 |

3,455.6 |

1,132.5 |

442.7 |

|

No-Year |

3,515 |

1,631 |

7,336.4 |

2,773.7 |

505.1 |

|

Total |

12,196 |

9,066 |

$24,392.7 |

$14,472.5 |

$1,750.0 |

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by agencies. | GAO‑25‑107274

Note: Percentages are based on total, unrounded amounts of agency-reported obligations and outlays, as a percentage of designated funds.

aThis column indicates the number and percentage of provisions for which agencies recorded obligations for either all or a portion of the designated funds.

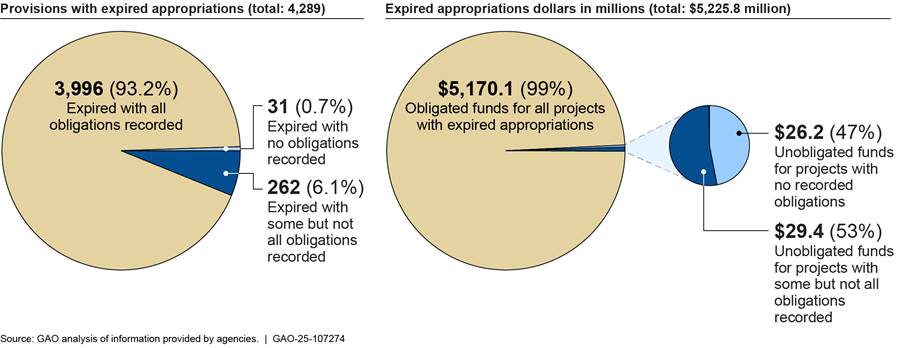

Agencies Recorded Obligations for Nearly All Provisions with Funding That Expired as of the End of Fiscal Year 2023

Appropriations for 4,289 provisions, representing $5.23 billion, expired as of the end of fiscal year 2023, as figure 4 shows. Agencies recorded obligations for 99 percent of these projects (4,258 projects) representing about 99 percent of the designated funds for these provisions ($5.17 billion).

Figure 4: Designated Funds and Agency-Recorded Obligations by Expiration Status for Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending, End of FY 2023

Notes: The 4,289 provisions with a period of availability that expired at the end of fiscal year 2023 included 3,938 projects with 1-year funding (fiscal year 2022 and 2023 provisions), 173 provisions with a 15-month period of availability (fiscal year 2022 provisions), and 178 provisions with 2-year funding (fiscal year 2022 provisions). We included provisions for those agencies that recorded obligations for either all or a portion of the designated funds as obligated in this count.

Agencies recorded obligations for the entire designated amounts for over 93 percent of projects with funds that had expired as of the end of fiscal year 2023.[15] See figure 5.

Figure 5: Agency-Recorded Obligations for Expired Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending, End of Fiscal Year 2023

Notes: Unobligated funds for expired appropriations are not available for new obligations but remain available to agencies to record, adjust, and liquidate prior obligations that were properly incurred, generally until 5 fiscal years from the end of the period of availability. After this period the funds are considered cancelled and are not available for obligation of expenditure for any purpose. We counted provisions as having recorded obligations for the entire designated amounts when agencies recorded obligations within one-hundredth of a percent of the provision’s designated funds.

Eight agencies recorded obligations for a portion of the designated funds for 262 projects with designated funds that expired as of the end of fiscal year 2023.[16] In total, these agencies did not record obligations for $29.4 million of designated project funds, ranging from less than $20 to $4.2 million for individual projects. The following examples highlight some of the reasons agency officials provided for recording obligations for a portion of the designated funds for projects.

· Agency withheld funds for administration and other costs. The Department of Defense withheld 10 percent from two projects related to research and development to support its Small Business Innovation Research program and related administrative costs, which include financial management, contracting support, and other costs. Specifically, from a $1 million project, the Department of Defense withheld $100,000 and for another project with designated funds of $964,000, the agency withheld $96,400.[17]

· Project cost less than designated amount. Department of Homeland Security officials told us that it had $13 million in cost reductions across its projects with recorded obligations. Department of Health and Human Services officials told us that recipients of four projects submitted budgets for at least 2 percent less than the designated amounts ($15,000 to $99,000). Additionally, National Archives and Records Administration officials stated that some recipients submitted budgets for less than the designated amounts.

Five agencies (the Departments of Education, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, the Interior, and the National Archives and Records Administration) recorded no obligations for 31 provisions with designated funds that expired at the end of fiscal year 2023 and reported that the projects did not go forward. In total, these agencies did not record any obligations for $26.2 million of designated project funds, ranging from $15,000 to $5.3 million for individual projects. Agency officials provided the following examples of why projects did not go forward.

· Recipient organization closed. Officials from the Department of Education told us they were unable to obligate funds for one recipient because the organization no longer existed.

· Recipient declined the funds or did not submit an application. Officials from the National Archives and Records Administration and the Departments of Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Education, and the Interior reported that recipients declined their awards or did not submit an application. For example, as we previously reported, one recipient did not apply for funds for a Department of Health and Human Services provision because they had received funding for the project under a Department of Education provision.[18] In addition, according to National Archives and Records Administration officials, one designated recipient did not have a unique identifier needed to apply for the funds.[19] The recipient did not have enough time to register for the identifier and was unable to apply for the funds.

· Agency determined the project was ineligible. Officials from the Department of Homeland Security’s Federal Emergency Management Agency told us that the agency determined that three fiscal year 2023 CPF/CDS provisions, as written, were not eligible for funding under its pre-disaster mitigation program. Officials told us that two of the applicants were private nonprofit organizations, which are not eligible entities under the program. The third provision was for a dredging project, which is not an eligible activity under the program.

Agencies Recorded Obligations for the Majority of Projects with Unexpired Designated Funding

Agencies recorded obligations for about 61 percent of projects with unexpired periods of availability (4,808 projects) representing about 49 percent of these designated funds ($9.3 billion), as of the end of fiscal year 2023. See table 3.

Table 3: Obligations and Outlays for Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending by Years of Remaining Availability, End of Fiscal Year 2023

Dollar amounts in millions, and percents of row totals are in parentheses

|

Years of remaining availability |

Number of provisions with remaining availability |

Number of provisions with funds obligateda (percent) |

Total funds designated |

Amount obligated (percent) |

Amount outlayed (percent) |

|

One |

518 |

151 |

$777.8 |

$269.1 |

$29.7 |

|

Two |

1,447 |

1,195 |

2,713.4 |

1,895.6 |

40.5 |

|

Three |

2,283 |

1,775 |

6,149.7 |

3,844.7 |

372.6 |

|

Four |

144 |

56 |

2,189.7 |

519.3 |

120.7 |

|

N/A (no-year funds) |

3,515 |

1,631 |

7,336.4 |

2,773.7 |

505.1 |

|

Total |

7,907 |

4,808 |

$19,167.0 |

$9,302.3 |

$1,068.7 |

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by agencies. | GAO‑25‑107274

Note: Percentages are based on total, unrounded amounts of agency-reported obligations and outlays, as a percentage of designated funds.

aThis column indicates the number and percentage of provisions for which agencies recorded obligations for either all or a portion of the designated funds.

Agencies recorded obligations for the entire designated amount for about 90 percent (4,324 of 4,808) of the projects with unexpired appropriations with obligated funds.[20] For the remaining 484 of the 4,808 provisions, agencies recorded obligations for a portion of the designated amount.

Eight agencies said they would not obligate additional amounts toward 71 of the 484 projects with obligations for a portion of the designated amount, as of the end of fiscal year 2023.[21] In total, these agencies do not plan to record obligations for $18.6 million of the designated project funds, ranging from less than $100 to $5.8 million for individual projects. Agency officials provided various reasons why they do not plan to record additional obligations for these projects.

· Agency withheld funds for the administration of the projects. Congress granted the Department of Commerce the authority to use 1 percent of designated funds for certain projects to pay for its associated administrative costs over the period of performance.[22] The Department of Agriculture withheld $500,000 from a $10 million project to cover expenses necessary to administer the project.[23]

· Project cost less than the designated amount. Department of Defense officials told us that one project had recorded obligations that were about $211,000 less than the amount of the designated funding. Additionally, officials from the Department of Energy stated that one recipient requested $20,000 less than the amount of the designated funding for a project.

Five agencies (the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Justice, and Transportation) reported that 15 of the 7,907 projects with unexpired designated funds as of the end of fiscal year 2023 were not going forward. In total, these agencies did not record any obligations for $14.0 million of designated funds, ranging from $14,000 to $8.7 million for individual projects. Agency officials provided the following examples of why projects did not go forward.

· Recipient declined the funds or did not submit an application. Officials from the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, and Justice reported that recipients declined the funds or did not complete an application. For example, the Department of Justice recorded an obligation of $30,000 to a designated recipient that had applied for the funds. However, the applicant subsequently declined the award and the agency deobligated the $30,000.

· Agency cancelled the project. Officials from the Department of Defense reported that the department cancelled a military construction project and reprogrammed a portion of the funds. In fiscal year 2023, the Department of Defense notified Congressional committees and reprogramed $5.2 million of the $8.7 million in project funds for an ongoing project within the same state.[24]

More than Half of Agencies Recorded Obligations for at Least 90 Percent of Their Projects

As table 4 shows, 10 of the 19 agencies recorded obligations for at least 90 percent of their projects and nine of these agencies obligated at least 90 percent of their designated funds.

Table 4: Obligations and Outlays for Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending Funds by Agency, End of Fiscal Year 2023

Dollar amounts in millions, and percents of row totals are in parentheses

|

Agency |

Number of provisions |

Number of provisions with funds obligateda (percent) |

Periods of availability |

Total funds designated |

Amount obligated |

Amount outlayed (percent) |

|

Department of Housing and Urban Development |

2,630 |

2,630 |

Four-year |

$4,498.7 |

$4,498.7 |

$3.6 |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

36 |

36 |

Two-year |

53.4 |

53.4 |

14.4 |

|

Office of National Drug Control Policy |

8 |

8 |

One-year |

10.5 |

10.5 |

0.2 |

|

Small Business Administration |

335 |

335 |

One-year |

262.7 |

262.7 |

25.7 |

|

Department of Education |

1,073 |

1070 |

One-year |

1,022.2 |

1,021.3 |

295.9 |

|

Department of Health and Human Services |

2,189 |

2,178 |

One- and no-year |

3,109.6 |

3,099.2 |

367.9 |

|

Department of Commerce |

245 |

243 |

Two- and no-year |

753.8 |

746.5 |

10.9 |

|

Department of Justice |

832 |

823 |

No-year |

703.9 |

702.0 |

65.3 |

|

Department of Homeland Security |

290 |

274 |

One-year |

522.3 |

477.4 |

1.0 |

|

National Archives and Records Administration |

43 |

40 |

One- and no-year |

73.8 |

30.9 |

3.0 |

|

General Services Administration |

5 |

4 |

No-year |

56.5 |

7.1 |

3.3 |

|

Army Corps of Engineers |

331 |

256 |

No-year |

1,603.1 |

528.5 |

258.7 |

|

Department of the Interior |

172 |

96 |

Two-, three-, and no-year |

242.3 |

174.6 |

66.8 |

|

Department of Defense |

245 |

122 |

Two- and five-year |

3,488.3 |

1,160.6 |

448.4 |

|

Department of Agriculture |

649 |

296 |

One-, two-, four-, and no-year |

899.7 |

384.2 |

46.1 |

|

Department of Labor |

422 |

173 |

Fifteen-month |

355.0 |

137.6 |

10.7 |

|

Department of Energy |

217 |

57 |

No-year |

325.1 |

90.7 |

2.1 |

|

Department of Transportation |

1,251 |

295 |

Three-, four-, five-, and no-year |

4,050.0 |

841.8 |

111.0 |

|

Environmental Protection Agency |

1,223 |

130 |

Two- and no-year |

2,361.9 |

244.9 |

14.9 |

|

Total |

12,196 |

9,066 |

|

$24,392.7 |

$14,472.5 |

$1,750.0 (7.2%) |

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by agencies. | GAO‑25‑107274

Note: Percentages are based on total, unrounded amounts of agency-reported obligations and outlays, as a percentage of designated funds.

aThis column indicates the number and percentage of provisions for which agencies recorded obligations for either all or a portion of the designated funds.

Agency officials described factors that affected when obligations were recorded for the CPF/CDS projects. For example, officials from the Department of Justice said they obligated funds for most of their projects, even though they were available indefinitely (no-year), because they understood it was a congressional priority to make the funds available to recipients quickly. Officials from the Department of Housing and Urban Development told us that the department determined its CPF/CDS funds were obligated as of the date of enactment by Congress.

Officials from one agency that had not obligated a majority of its designated funds said that the timing of obligations can be affected by project-specific factors, including project complexity and schedule. Specifically, Department of Transportation officials told us that completing a planning study could take a year, while completing a full construction project and obligating and outlaying the funds for that project could take multiple years.[25] Similarly, officials from the Environmental Protection Agency told us that one of the agency’s biggest challenges in obligating these funds has been ensuring the projects comply with applicable federal requirements, which needs to occur before the agency can obligate any of the funds. Officials said that in some cases, the difficulty is due to the lack of technical capacity on the part of designated recipients. Officials said that many of these recipients face challenges in completing their applications to receive funding, and a small percentage have no experience applying for federal funds. As a result, many recipients require significant technical assistance from the agency, which can delay obligating the funds.[26]

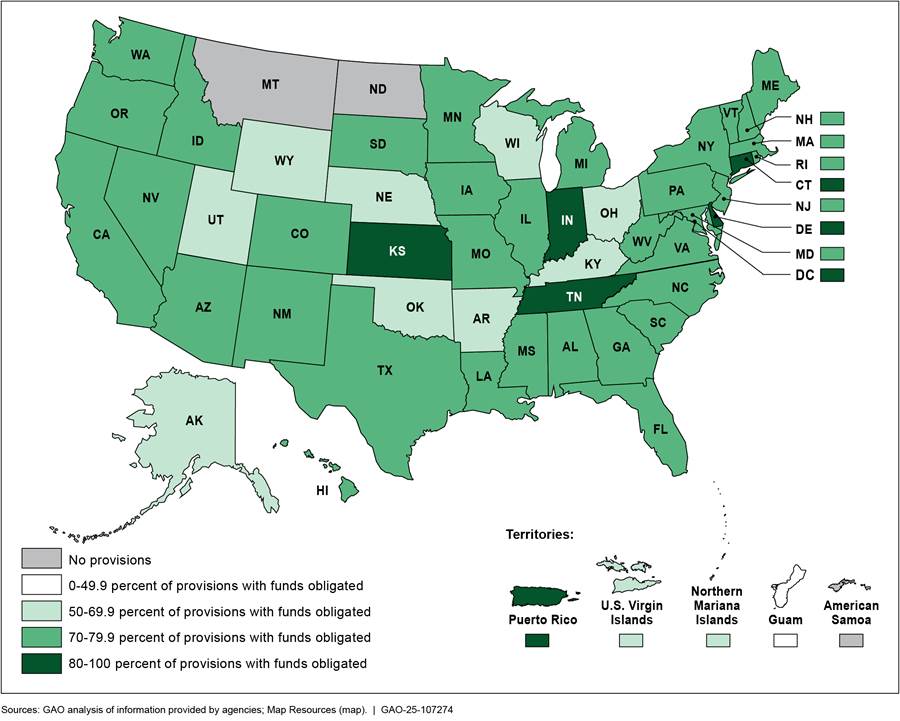

Agencies Recorded Obligations toward More Than Half of the Projects in All States and Territories Where Projects Are Located

For fiscal years 2022 and 2023, Congress designated funding for projects located in 48 states, the District of Columbia, and four of the U.S. territories.[27] The number of projects for designated recipients in these states or territories ranged from two (Guam) to 1,225 (California). The total amounts designated for those projects ranged from about $4.4 million (Guam) to about $2.2 billion (California).

As figure 6 illustrates, agencies recorded obligations for at least 50 percent of projects in 48 states, the District of Columbia, and three territories.[28] Among these locations, agencies recorded obligations for at least 80 percent of projects in five states, the District of Columbia, and one territory. Additionally, four agencies received funding for individual projects located across two to seven different states or the District of Columbia. Agencies recorded obligations toward 18 of the 20 projects located across multiple states and 77.2 percent ($135.8 million) of the $176.0 million in designated funds.

Figure 6: Percentage of Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending Projects with Recorded Obligations by Location of Designated Recipient, End of Fiscal Year 2023

Note: Among the projects, 20 are located in more than one state, such as water management projects along a river. These projects are not included in the figure. Funds designated for these 20 multistate projects total about $176.0 million and are located in 30 states and the District of Columbia. While no provisions were located solely in Montana, two multistate provisions are to be executed in Montana along with six other states. No single-state or multistate provisions are located in North Dakota. Additionally, no provisions are located in American Samoa.

Agencies Recorded Obligations at a Higher Rate for Projects for Higher Education Organizations and Other Nonprofit Organizations than for Other Recipient Types

In our prior work analyzing projects funded by CPF/CDS provisions for fiscal years 2022 and 2023, we classified the recipients of the designated funds as either (1) federal government, (2) tribal/state/local/territorial government, (3) higher education organizations, or (4) other nonprofit organizations.[29]

As table 5 shows, agencies recorded obligations for more than 90 percent of the projects designated for higher education organizations and other nonprofit organizations. Agencies recorded obligations for 68 percent of projects designated to federal recipients and 59 percent of projects for tribal/state/local/territorial government recipients. Funding for 99 percent of projects designated for federal recipients and funding for 81 percent of projects designated to tribal/state/local/territorial government recipients will be available for obligation for a period of availability of four or more years.

Table 5: Obligations and Outlays for Fiscal Year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending by Recipient Type, End of Fiscal Year 2023

Dollar amounts in millions, and percents of row totals are in parentheses

|

Recipient type |

Number of provisions |

Number of provisions with funds obligateda (percent) |

Total funds designated |

Amount obligated (percent) |

Amount outlayed (percent) |

|

Other nonprofit organizations |

4,211 |

3,852 (91.5%) |

$4,952.1 |

$4,538.4 (91.6%) |

$412.6 (8.3%) |

|

Higher education organizations |

1,411 |

1,280 (90.7) |

2,743.9 |

2,494.0 |

327.4 (11.9) |

|

Federal government |

686 |

467 (68.1) |

5,362.0 |

1,853.8 |

746.9 |

|

Tribal/state/ local/territorial government |

5,888 |

3,467 (58.9) |

11,334.7 |

5,586.2 (49.3) |

263.1 (2.3) |

|

Total |

12,196 |

9,066 |

$24,392.7 |

$14,472.5 (59.3%) |

$1,750.0 (7.2%) |

Source: GAO analysis of information provided by agencies. | GAO‑25‑107274

Note: Percentages are based on total, unrounded amounts of agency-reported obligations and outlays, as a percentage of designated funds.

aThis column indicates the number and percentage of provisions for which agencies reported that they had recorded obligations for either all or a portion of the designated funds.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the 19 agencies that were appropriated funds through Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending provisions for fiscal years 2022 and 2023 for review and comment. We received technical comments from the Departments of Agriculture and Energy that we incorporated, as appropriate. The remaining 17 agencies informed us they had no comments.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the 19 agencies that were appropriated funds, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Jeff Arkin at (202) 512-6806 or arkinj@gao.gov or Allison Bawden at (202) 512-3841 or bawdena@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Jeff Arkin

Director, Strategic Issues

Allison Bawden

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

List of Committees

The Honorable Patty Murray

Chair

The Honorable Susan Collins

Vice Chair

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Chris Van Hollen

Chair

The Honorable Bill Hagerty

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Jack Reed

Chair

The Honorable Deb Fischer

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Legislative Branch

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Tom Cole

Chairman

The Honorable Rosa DeLauro

Ranking Member

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable David Joyce

Chairman

The Honorable Steny Hoyer

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable David Valadao

Chairman

The Honorable Adriano Espaillat

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Legislative Branch

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

This report describes the amount of funds designated by the fiscal year 2022 and 2023 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending (CPF/CDS) provisions that have been recorded as obligated and outlayed as of the end of fiscal year 2023, as reported by the 19 agencies responsible for distributing the funds.[30] We are also publishing an online dataset to accompany this report.[31]

For this objective, we reviewed previous GAO work from our series of reports related to these provisions.

To identify the factors that affect the timing of obligations and outlays, we interviewed officials from the 19 agencies about their plans and processes for implementing the fiscal year 2022 and 2023 provisions.

To obtain the agencies’ recorded obligations and outlays for these provisions as of the end of fiscal year 2023, we created data collection instruments for each of the 19 agencies that included information on each of the provisions we identified through our prior work and that the agencies had previously verified.[32] In addition to the obligations and outlays the agencies recorded as of the end of fiscal year 2023, we asked agencies to provide a completion status for obligations and outlays for each provision indicating that no further obligations were anticipated.

We performed manual and programmatic checks of completeness, reasonability, and logic on the collected data. For example, we manually verified that data were entered for each provision and programmatically checked for duplicate records. We also ensured that reported amounts reflected expected budget execution patterns, such as ensuring that obligations did not exceed the designated amount for the provision. We followed up with agencies in instances in which we found inconsistencies with the data they had reported and resolved the issues.

The Department of Education did not report its data through the data collection instrument. Instead, the agency provided output from its internal agency systems, and we matched the records. The agency reviewed the data collection instrument we generated and confirmed we matched the data correctly. We maintained the project and recipient descriptions as they were presented in the joint explanatory statements except where Congress included technical corrections in law, or the agency had legal authority to make technical corrections to the project and recipient descriptions, as further discussed below. Additionally, for one category of projects, the Department of Energy did not complete the data collection instrument because it had recorded no obligations or outlays for these provisions. We manually filled in the data fields in the data collection instrument with zeros for this category of provisions.

Through the process of completing the data collection instruments, we worked with the agencies to make corrections and resolve inconsistencies in the information they provided. In some cases, agencies corrected the information they had reported to us for our prior report.[33] For example:

· One agency reported lower outlay amounts as of September 30, 2023, than it reported as of September 30, 2022, for our previous report. In response to our inquiry about the project outlays, the agency indicated that the outlays it reported for the prior report were incorrect and that outlays reported for the projects for this report were correct.

· One agency originally reported obligating additional funds toward several of its projects that came from other sources of appropriations, but we asked the agency to resubmit the data collection instruments with the other sources excluded.

· One agency reported a change in recipient type for some projects as compared to what we reported in our prior report.

· A few agencies reported deobligations from prior reported obligations, which we included in the data.

While some agencies reported to us that they made or planned to make adjustments to the obligations or outlays after September 30, 2023, we did not seek to include these adjustments in our data because our data reflect the status of obligations and outlays as of September 30, 2023.

The obligations and outlays data we include in this report and our online dataset are reported according to the agencies. We gave the agencies an opportunity to comment and submit additional evidence along with their data if they requested a change. We did not compare the obligations and outlay data agencies submitted to us against agency records. We did not evaluate whether agency obligations or outlays were completed in compliance with fiscal laws.

To help assess the reliability of the agencies’ data, we included standardized data quality questions as part of our data collection instrument. We verified that all the agencies that submitted data to us also responded to the standardized data quality questions. The Department of Energy did not provide answers to our data quality questions for the category of projects with no recorded obligations and outlays because they were not applicable. None of the agencies’ responses raised any issues of concern related to the completeness, accuracy, or usability of the data they reported to us through the data collection instrument that ultimately affected the data they reported. However, one agency noted that reconciliation with an external data system could affect the timeliness of the data. Upon following up with the agency, the agency said that because we asked for data from several months earlier, the reconciliation did not affect the accuracy of the data.

To help understand potential broader financial management data quality issues within each agency, we reviewed the independent auditor’s reports on each agency’s fiscal year 2023 financial statements.[34] Most agencies used their financial systems to provide the obligation and outlay data we requested.[35] The independent auditor’s reports include examination of the agency’s internal controls over financial reporting and compliance with selected provisions of applicable laws, regulations, contracts, and grant agreements. Where applicable, we also reviewed auditors’ reports on whether each agency’s financial management systems complied substantially with the three requirements of the Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996.[36]

We identified six agencies that either had material weaknesses in financial management or a significant deficiency in grants management. We asked these agencies how these issues affected the accuracy and completeness of their data. Officials from all six agencies stated that the issues found had no effect on the data they provided. We did not independently evaluate how these issues may specifically affect the obligation and outlay data we collected from agencies.

An agency official said that the Executive Office of the President’s Office of Chief Financial Officer creates the financial statement and audit report for the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) and other Executive Office of the President components. An ONDCP official said the agency cannot separate out ONDCP’s information from the other Executive Office of the President components. We asked ONDCP about any control deficiencies or noncompliance issues identified in the auditor’s report that would affect the financial reporting of obligations and outlays as provided to us. An ONDCP official told us that the Executive Office of the President’s financial statements were audited by an independent firm and received an unmodified (clean) opinion.

We found the data to be reliable for the purpose of reporting the status of agency-reported obligations and outlays for the amounts of funds designated for these projects.

Throughout this report, we present the obligations that agencies reported to us as being recorded as of the end of fiscal year 2023, but the point of obligation for some of the provisions may have already occurred through the enactment of law.[37] We have not determined when an obligation would arise for each specific grant action that agencies may take for funds designated through CPF/CDS provisions in the Consolidated Appropriations Acts, 2022 and 2023.[38]

Many of the figures and tables in this report contain counts of the number of projects for which agencies recorded obligations for any amount of designated funds—a portion of or all designated funds. We include projects with any amount of recorded obligations as obligated in these counts. Further, the presence of any obligations is an indication that the agency has begun taking steps to implement the provision. Additionally, we consider agency recorded obligations of 99.99 percent or more of designated funds as all designated funds obligated. We made this decision in order to address potential rounding issues in the reported data.[39]

We described the data using different categories, including period of availability, agency, location, recipient type, and expiration status.[40] As discussed in prior work, we determined the period of availability, agency, and location directly or by inference from the Consolidated Appropriations Acts, 2022 and 2023 and their accompanying joint explanatory statements. We include only states, the District of Columbia, and territories in our analysis because the location data in the joint explanatory statements shows a project’s location as a state or territory. We were not able to separate out Tribal Nations. Projects related to tribal governments are included within the relevant state or territory. We determined expiration status by applying the appropriation year, the period of availability, and our reporting date of September 30, 2023. Finally, we inferred recipient type from the joint explanatory statements project and recipient information and from information provided by agencies.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 and accompanying joint explanatory statement designated $15.3 billion for 7,234 provisions. Officials from the Environmental Protection Agency told us that the fiscal year 2022 appropriations included one provision for $780,000 that incorrectly identified the recipient. Congress subsequently included a technical correction in the fiscal year 2023 appropriations modifying the recipient’s name, but with $0 appropriated. We corrected the name of the recipient for the fiscal year 2022 provision and removed the fiscal year 2023 provision from our data set. As a result, together with the 4,963 fiscal year 2022 provisions, our data set includes 12,196 rather than 12,197 provisions.

We revised information for 51 fiscal year 2022 and 2023 CPF/CDS projects based on Congress’ technical corrections from the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, and the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024.[41] Most of these changes were technical corrections to the names of the CPF/CDS recipients, the projects, or both for projects administered by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Departments of Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, the Interior, Labor, and Transportation. One technical correction changed the name of the requestor.

In addition, we revised information for 83 fiscal year 2022 and 2023 CPF/CDS projects based on technical corrections made by the Environmental Protection Agency pursuant to its permanent authority authorizing the agency to award state and tribal grants to entities and for purposes other than those listed in a joint explanatory statement accompanying an appropriations act.[42] As of May 2024, the Environmental Protection Agency made technical corrections to the names of the recipients, projects, or both for the provisions. Two of the corrections resulted in a change in recipient type.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Jeff Arkin, (202) 512-6806 or arkinj@gao.gov

Allison Bawden, (202) 512-3841 or bawdena@gao.gov

In addition to the contacts named above, Janice Latimer (Assistant Director), Karen Jarzynka-Hernandez (Analyst in Charge), Ann Marie Cortez, John Delicath, Bonnie Pignatiello Leer, Caitlin Loftus, Gabriel Nelson, Omari Norman, Nina M. Rostro, Dan C. Royer, and Walter Vance made key contributions to this report.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Pub. L. No 117-328, 136 Stat. 4459 (Dec. 29, 2022); Pub. L. No. 117-103, 136 Stat. 49 (Mar. 15. 2022). The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 and accompanying joint explanatory statement designated $15.3 billion for 7,234 provisions. However, we removed one provision because it served as a technical correction for a fiscal year 2022 provision. Congress did not designate funds for this technical correction. See appendix I for more information.

[2]For this report, we count the U.S Army Corps of Engineers and the Office of National Drug Control Policy within the Executive Office of the President as agencies.

[3]We have issued a series of reports in response to these provisions. See our Tracking the Funds website, www.gao.gov/tracking‑funds. The Tracking the Funds website includes additional data and visualizations as a part of this work. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024, and The Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024 also included specific CPF/CDS provisions. Pub. L. No. 118-42, 138 Stat. 25 (Mar. 8, 2024); Pub. L. No. 118-47, 138 Stat. 460 (Mar. 23, 2024). See GAO, Tracking the Funds: Specific Fiscal Year 2024 Provisions for Federal Agencies, GAO-25-107549 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 21, 2024) for more information.

[4]An obligation is a definite commitment that creates a legal liability on the part of the federal government for the payment of goods and services ordered or received. An outlay occurs upon the issuance of checks, disbursement of cash, or electronic transfer of funds made to liquidate a federal obligation.

[5]This dataset can be accessed on our public website at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao‑25‑107274.

[6]When referring to CPF/CDS, we use the term “provisions” when describing the line items laid out in the joint explanatory statements. These provisions usually describe projects and designated recipients. We use the term “projects” when describing the implementation of the provisions identified in the joint explanatory statements.

[7]In this report, we use the term financial system to refer to an agency’s information system used to, among other things, collect, maintain, and report data about financial events and costs, such as obligation amounts incurred and payments authorized to satisfy those obligations (i.e., outlays). In addition to financial systems, some agencies reported data from grants management systems or business intelligence systems.

[8]Most federal executive agencies are required to annually prepare agency-wide financial statements and have them independently audited in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. 31 U.S.C. §§ 3515, 3521(e). These audits are to be performed by the executive agency’s Inspector General; by an independent external auditor as determined by the Inspector General; or, for executive agencies that lack a statutory Inspector General, by an independent external auditor as determined by the agency head. 31 U.S.C. § 3521(e). An agency official said that the Executive Office of the President’s Office of Chief Financial Officer creates the financial statement and audit report for the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) and other Executive Office of the President components. We asked the agency about any control deficiencies or noncompliance issues identified in the auditor’s report that would affect the financial reporting of obligations and outlays as provided to us. An ONDCP official told us that the Executive Office of the President’s financial statements were audited by an independent firm and received an unmodified (clean) opinion.

[9]The Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996 requires the 24 agencies listed in 31 U.S.C. § 901(b) (commonly referred to as “CFO Act agencies”) to implement and maintain financial management systems that comply substantially with (1) federal financial management system requirements, (2) applicable federal accounting standards, and (3) the United States Government Standard General Ledger at the transaction level. Pub. L. No. 104-208, div. A, §101(f), title VIII, 110 Stat. 3009, 3009-389 (Sept. 30, 1996), reprinted in 31 U.S.C. § 3512 note.

[10]Appropriations for legislative branch agencies, the judicial branch, the District of Columbia, and the International Trade Commission are apportioned by officials having administrative control of those funds. 31 U.S.C. § 1513(a).

[11]In these instances, an agency must still record an accounting charge against the appropriation in its obligational records, but this charge reflects the obligation the agency already incurred and is not the creation of the obligation. For additional information regarding the point of obligation for grants, see appendix VI in GAO, Tracking the Funds: Specific Fiscal Year 2022 Provisions for Federal Agencies, GAO‑22‑105467 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2022).

[12]These corrections applied to the Environmental Protection Agency and the Departments of Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, the Interior, Labor, and Transportation. See Pub. L. No. 117-328; Pub. L. No. 118-42; Pub. L. No. 118-47.

[13]Congress granted the Environmental Protection Agency a permanent technical authority authorizing it to award state and tribal assistance grants to entities and for purposes other than those listed in a joint explanatory statement accompanying an appropriations act. Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2006. Pub. L. No. 109-54, 119 Stat. 499, 530 (Aug. 2, 2005).

[14]We included provisions for those agencies that recorded obligations for any amount of designated funds as obligated in this count. Further, the presence of an obligation is an indication that agencies have begun taking steps to implement the provisions.

[15]We counted provisions as having recorded obligations for the entire designated amounts when agencies recorded obligations within one-hundredth of a percent of the project’s designated funds. See appendix 1 for more information.

[16]The eight agencies are the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and the Interior as well as the National Archives and Records Administration.

[17]The Small Business Innovation Research program was established to increase the participation of small innovative companies in federally funded research and development and to stimulate small businesses’ technology development and commercialization. According to DOD officials, the agency set aside a portion of funding to support its program.

[18]GAO, Tracking the Funds: Sample of Fiscal Year 2022 Projects Shows Funds Were Awarded for Intended Purposes but Recipients Experienced Some Challenges, GAO‑24‑106334 (Washington, D.C: Sept. 25, 2024).

[19]Some agencies require grantees to register for a Unique Entity Identifier from the System for Award Management (SAM.gov), an official website of the U.S. government used by grantees to do business with the federal government.

[20]We counted provisions as having recorded obligations for the entire designated amounts when agencies recorded obligations within one-hundredth of a percent of the designated funds.

[21]The eight agencies are the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Energy, and Health and Human Services, the Army Corps of Engineers, the Environmental Protection Agency, and General Services Administration.

[22]See Pub. L. No. 117-328, 136 Stat. at 4516; Pub. L. No. 117-103, 136 Stat. at 106-07.

[23]Officials from the Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture said the agency set aside 5 percent of the funds to administer the CPF/CDS provision, consistent with agency practice where specific legislation does not provide additional administrative costs. Officials reported that the agency establishes an overhead rate that is calculated annually based upon the previous 3 year’s overhead rates. When this program was funded, the National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s overhead rate was 5 percent.

[24]The ongoing project was not a CPF/CDS project.

[25]GAO, Tracking the Funds: Specific Fiscal Year 2022 Provisions for Department of Transportation, GAO‑22‑105892 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2022).

[26]GAO, Tracking the Funds: Agencies Have Begun Executing FY 2022 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending, GAO‑23‑106318 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 28, 2023).

[27]While no projects were located solely in Montana, two multistate projects are to be executed in Montana along with six other states. No single-state or multistate projects are located in North Dakota. Additionally, no projects are located in American Samoa.

[28]We include only states, the District of Columbia, and territories in our analysis because the location data in the joint explanatory statements only shows a project’s location as a state (including the District of Columbia) or territory. We are not able to separate out Tribal Nations when examining geography. Projects related to tribal governments are included within the relevant state or territory. See appendix I for additional details.

[29]GAO‑22‑105467. In some cases, the designated recipient is the federal government, such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers or the Department of the Interior. For example, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is designated to receive funds to undertake specific dam and dredging projects.

[30]For this report, we count the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Office of National Drug Control Policy, within the Executive Office of the President, as agencies.

[31]This dataset can be accessed on our public website at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao‑25‑107274.

[32]GAO, Tracking the Funds: Agencies Have Begun Executing FY 2022 Community Project Funding/Congressionally Directed Spending, GAO‑23‑106318 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 28, 2023); Tracking the Funds: Specific FY 2023 Provisions for Federal Agencies, GAO‑23‑106561 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 28, 2023); and Tracking the Funds: Specific Fiscal Year 2022 Provisions for Federal Agencies, GAO‑22‑105467 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 12, 2022).

[34]Most federal executive agencies are required to annually prepare agency-wide financial statements and have them independently audited in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. 31 U.S.C. §§ 3515, 3521(e). These audits are to be performed by the executive agency’s Inspector General; by an independent external auditor as determined by the Inspector General; or, for executive agencies that lack a statutory Inspector General, by an independent external auditor as determined by the agency head. 31 U.S.C. § 3521(e).

[35]In this report, we use the term financial system to refer to an agency’s information system used to, among other things, collect, maintain, and report data about financial events and costs, such as obligation amounts incurred and payments authorized to satisfy those obligations (i.e., outlays). In addition to financial systems, some agencies reported data from grants management systems.

[36]The Federal Financial Management Improvement Act of 1996 requires the 24 agencies listed in 31 U.S.C. § 901(b) (commonly referred to as “CFO Act agencies”) to implement and maintain financial management systems that comply substantially with (1) federal financial management system requirements, (2) applicable federal accounting standards, and (3) the United States Government Standard General Ledger at the transaction level. Pub. L. No. 104-208, div. A, §101(f), title VIII, 110 Stat. 3009, 3009-389 (Sept. 30, 1996), reprinted in 31 U.S.C. § 3512 note.

[37]An agency may record an obligation only at the point of incurring an obligation, known as the obligational event. For grants, the time when an agency incurs an obligation varies depending on the nature of the grant. In some situations, the agency incurs an obligation when it awards a grant. For other grants, the timing of the obligational event may be outside of the agency’s control. For example, in some circumstances, the agency may incur an obligation immediately when the appropriation for the grant becomes law. In these instances, an agency must still record an accounting charge against the appropriation in its obligational records, but this charge reflects the obligation the agency already incurred and is not the creation of the obligation.

[38]For more information about the obligational event of grants, see GAO‑22‑105467, appendix VI.

[39]For some projects, agencies recorded obligations slightly below the designated funds.

[40]We have previously categorized designated recipients into four categories: federal government; tribal, state, territorial, or local governments; higher education organizations; and other nonprofit organizations. We assigned all recipients that are not federal government; tribal, state, territorial, and local government; or higher education organizations to the “other nonprofit organization” category since a designated recipient cannot be a for-profit entity. Examples of “other nonprofit” organizations include organizations that provide programs for workforce development, shelter for victims of domestic violence, and interim housing for the homeless.

[41]Pub. L. No. 117-328, 136 Stat. 4459 (Dec. 29, 2022); Pub. L. No. 118-42, 138 Stat. 25 (Mar. 8, 2024); Pub. L. No. 118-47, 138 Stat. 460 (Mar. 23, 2024).

[42]Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-54, 119 Stat. 499, 530 (Aug. 2, 2005).