DEFENSE INDUSTRIAL BASE

Actions Needed to Address Risks Posed by Dependence on Foreign Suppliers

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107283. For more information, contact William Russell at RussellW@gao.gov and Tatiana Winger at WingerT@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107283, a report to congressional committees

Actions Needed to Address Risks Posed by Dependence on Foreign Suppliers

Why GAO Did This Study

The January 2024 National Defense Industrial Strategy stated that DOD’s dependence on adversarial sources for goods it procures is a mounting national security challenge. These suppliers may cut off U.S. access to critical materials or provide “back doors” in their technology that serve as intelligence pathways.

The Conference Report and a House Report for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 include provisions for GAO to report on DOD’s dependence on foreign entities and its processes for determining whether it is procuring goods from China. This report, among other things, (1) describes the information that government procurement data contains on the country of origin of goods that DOD procures, and (2) assesses DOD actions to collect additional data.

To conduct this work, GAO analyzed government procurement data from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, reviewed DOD documents, and interviewed DOD officials and contractor representatives.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that DOD identify resources, priorities, and time frames to implement efforts to integrate and share supply chain data; identify an organization responsible for implementing leading commercial practices; and test the use of contract requirements to obtain country-of-origin information from suppliers. DOD concurred with all three recommendations.

What GAO Found

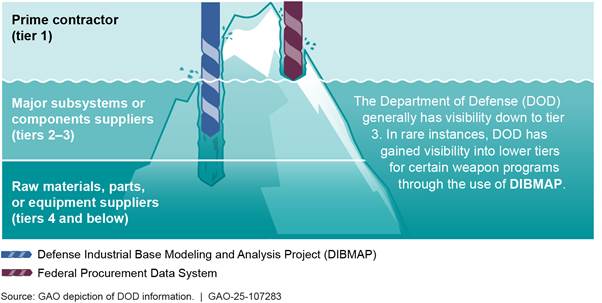

The Department of Defense (DOD) considers reliance on foreign sources for items it procures a national security risk. DOD estimates that over 200,000 suppliers help produce advanced weapon systems and noncombat goods. The primary procurement database for the federal government, however, provides little visibility into where these goods are manufactured or whether materials and parts suppliers are domestic or foreign.

DOD is pursuing several supply chain visibility efforts designed to help improve its ability to identify risks of what it refers to as “foreign dependency.” DOD has made progress gathering supplier information for major subsystems and components. However, these efforts are uncoordinated and limited in scope and provide little insight into the vast majority of suppliers, including those that provide raw materials and parts.

DOD identified actions it can take to improve its ability to identify and mitigate foreign dependency issues, including

· establishing an office to integrate efforts across DOD; and

· implementing leading commercial practices for supply chain visibility, such as focusing visibility efforts on high-priority programs.

However, DOD has yet to identify resources, priorities, and time frames for completing the integration. Additionally, it has not identified the organization responsible for implementing the leading commercial practices. Without doing so, DOD will be less able to identify and address foreign dependency risks.

One untested approach that DOD officials stated could give DOD more visibility into foreign dependency risks is to contractually require suppliers to provide the information. While some DOD officials assert the information is readily available, others stated this approach may be too costly or that suppliers may not be willing to provide information. Unless DOD tests the costs and challenges of requiring suppliers to provide foreign dependency information, it could be missing an opportunity to address a mounting challenge to the security of its supply chains.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DIBMAP |

Defense Industrial Base Modeling and Analysis Project |

|

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

|

FPDS |

Federal Procurement Data System |

|

|

SCREEn |

Supply Chain Risk Evaluation Environment |

|

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 24, 2025

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Department of Defense (DOD) relies on a global network of over 200,000 suppliers to produce weapon systems—such as fighter jets, helicopters, and destroyers—as well as noncombat goods, such as batteries and manufacturing equipment. In September 2018, DOD reported that its reliance on foreign sources of supply, which we refer to as foreign dependency, is a risk to the defense industrial base and to national security.[1] This is because, among other things, adversarial sources may cut off U.S. access to critical materials to produce weapons or provide “back doors” in their technology that serve as intelligence pathways. For example, in 2024, China imposed export restrictions on gallium and germanium—two elements critical for military-grade electronics.

In October 2024, DOD stated that supply chain visibility is essential for the military services to ensure operational readiness and strategic advantage and that it will be a major component of its efforts to improve production and supply chains.[2] Further, DOD stated that greater visibility will help it identify potential supply chain disruptions, such as those related to foreign dependence, and manage these risks more effectively.

The Conference Report for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to report on the degree to which DOD is dependent on entities located in foreign countries for the procurement of certain end items and components essential for national security, which we refer to as “goods.”[3] In addition, the House Report accompanying the legislation contained a similar provision for us to examine DOD processes for determining whether it is procuring noncombat goods from China and considering alternate sources, including domestic manufacturers, when there are concerns about the manufacturing origin of these goods.[4] Our report (1) describes the information that government procurement data contain on the country of origin of goods that DOD procures, (2) assesses the extent to which DOD is taking action to collect additional country-of-origin data, and (3) describes DOD’s efforts to mitigate foreign dependency risks.

To describe the information that government procurement data contain on the country of origin of goods that DOD procures, we analyzed relevant data from the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, the most recent data available during the time of our review. FPDS is the primary government-wide database for federal procurement. To assess the extent to which DOD is taking actions to collect additional country-of-origin data, we analyzed pertinent documents on new DOD initiatives, including guidance, project plans, data calls, and briefings.

To describe DOD’s efforts to mitigate foreign dependency, we analyzed DOD strategies, action plans, annual capability reports, and implementation reports from fiscal years 2020 through 2024 for DOD’s supply chains.[5] We selected three examples—the F-35 fighter jet, lithium batteries, and 155 mm ammunition—for further analysis to illustrate how DOD identifies and mitigates foreign dependency risks. We also interviewed knowledgeable DOD officials to supplement the information we collected throughout the review. A detailed description of our scope and methodology is included in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The U.S. Defense Industrial Base

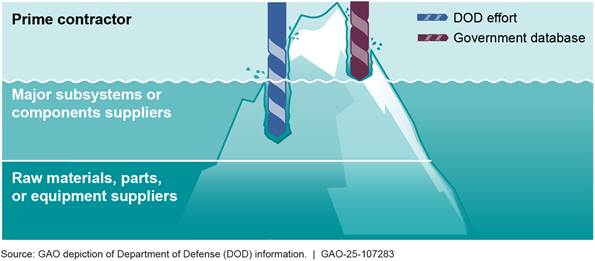

The defense industrial base can be divided into several tiers: prime contractors, major subcontractors, and lower tiers that include suppliers of parts, electronic components, and raw materials. Industries and companies that constitute the U.S. defense industrial base often supply both military and commercial markets. DOD relies on a globalized network of suppliers for the components and technologies used in its weapon systems and other goods it procures.

We previously reported that domestic companies that offshore their operations or accept foreign investment can help DOD save money and access more technology.[6] But a globalized supply chain can also make it harder for DOD to get what it needs if, for example, other countries cut off U.S. access to critical supplies. We also reported that this has made it more difficult for DOD to identify sources that may present a risk, particularly at the lower levels of the supply chain, which includes materials and small electronic components.[7]

Supply Chain Risks

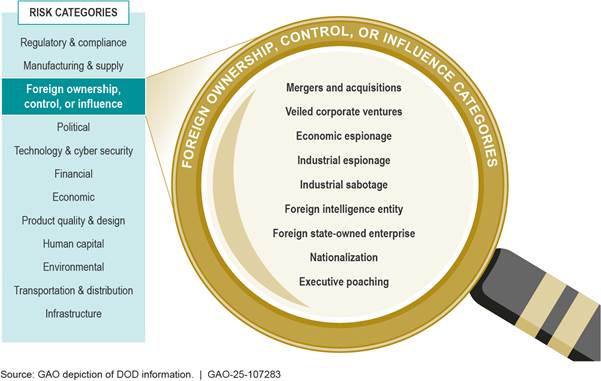

DOD requires resilient, diverse, and secure supply chains to ensure the development and sustainment of capabilities critical to national security.[8] DOD organizations such as weapon acquisition programs and the Defense Logistics Agency collect information on DOD’s suppliers so they can ensure access to needed goods. The organizations screen the information for 12 categories of supply chain risk, including foreign ownership, control, or influence risks. As shown in figure 1, there are nine categories of foreign ownership, control, or influence risks.

One type of foreign ownership, control, or influence risk is nationalization. This is the process of a foreign government taking control of a company or industry that was previously privately owned. This may result in political interference in operations. When addressing these risks, DOD must make tradeoff decisions. According to the National Defense Industrial Strategy, DOD must balance the need for speed and scale with cost.

Executive Orders and Congressional Mandates Related to Defense Industrial Base

In recent years, the President and Congress have taken action to help improve DOD’s ability to identify and mitigate defense industrial base risks, including those related to foreign dependence. For example:

· In February 2021, Executive Order 14017 directed DOD to assess its critical supply chains to improve its capacity to defend the nation.[9] In response, DOD issued an action plan in February 2022 that prioritized four areas in which critical vulnerabilities posed the most pressing threat to national security.[10] The areas included kinetic capabilities; energy storage and batteries; castings and forgings; and microelectronics. In this action plan, DOD also provided an update on steps it took to mitigate risks for obtaining critical minerals and materials.

· Section 846 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 required DOD to develop a National Security Strategy for the National Technology and Industrial Base that included a prioritized assessment of risks and challenges to the defense industrial base.[11] In response, DOD released its first National Defense Industrial Strategy in January 2024 and unclassified implementation plan in October 2024. The National Defense Industrial Strategy stated that DOD’s dependence on adversarial sources for goods it procures is a mounting national security challenge. The strategy also outlines DOD’s priorities, while the implementation plan identifies the organizations responsible for leading individual efforts, resources needed to mitigate risks over the next 5 years, and metrics to measure progress. One of the planned actions includes assessing supply chain risk vulnerabilities through the development and use of tools that illuminate adversarial influence on DOD supply chains, which we refer to as supply chain visibility. This effort includes identifying foreign supplier risks.

Primary DOD Organizations Engaged in Guidance and Oversight of the Defense Industrial Base

Several DOD organizations have responsibilities for providing guidance and oversight of the defense industrial base and mitigating industrial base risks.

· The Assistant Secretary of Defense for Industrial Base Policy, within the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, is DOD’s principal advisor for issues affecting the industrial base. Among other things, the office conducts DOD-wide industrial base risk assessments to identify risks, coordinates certain industrial base investments to mitigate risks, and reports annually on assessments of the defense industrial base and associated risks and mitigation efforts.

· The Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Logistics, also within the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, is responsible for DOD’s logistics strategy and policy; supply, storage and distribution; property and equipment; transportation; and program support functions. Among other things, the office is responsible for improving the visibility, accountably, and control of all critical assets.

· The Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office supports DOD’s integration of procurement data into a single enterprise data management and analytics platform, known as Advana.[12] Advana contains data from various government procurement sources, including FPDS and information the office is collecting for certain weapon acquisition programs.

· DOD often relies on the military service acquisition executives, system commands, and program offices to execute risk mitigation efforts. The service acquisition executives implement risk mitigation efforts across their respective enterprises.[13] It is DOD’s practice to delegate risk mitigation to the lowest level possible—the program offices—as these offices are the most knowledgeable about their changing risks and must address them to help meet cost, schedule, and performance goals.

Government Procurement Data Provide DOD with Limited Insight into the Country of Origin of Goods

FPDS—the primary government-wide database for federal procurement—contains summary level contract information on goods that federal agencies procure but provides limited information about the countries of origin for these goods.[14] FPDS allows DOD and other federal agencies to record and report information on all contracts they award, track spending, analyze procurement trends, and generate reports for transparency and accountability purposes.[15] We identified two data fields in FPDS that have information on the countries where goods that DOD procures are manufactured: (1) Place of Manufacture, and (2) Country of Product or Service Origin. The data for these two fields provide information on compliance with laws related to domestic sourcing, such as the Buy American Act.[16]

· Place of Manufacture field: This field represents whether the end products being procured (manufactured goods only) are manufactured inside or outside the U.S. in accordance with the Buy American Act. The field does not indicate the country where components are manufactured. Options in this field include indicating that the products are made in the U.S., or that they are made outside the U.S. and qualify under one of the regulatory exceptions, or that the contract is subject to the requirements of a trade agreement instead of the Buy American Act requirements. For fiscal years 2020 through 2024, FPDS data show the U.S. as the Place of Manufacture for approximately 95 percent of the obligations for goods that DOD procured.

· Country

of Product or Service Origin field: This field represents the country from

where the preponderance of the content of the products (goods) or services

being procured is derived. If the good or service is a domestic end product,

then the U.S. is identified as the Country of

Origin in FPDS.[17]

If the good or service is not a domestic end product, then a country code is

entered that identifies the one country where the preponderance of the

acquisition’s content came from. FPDS does not include country information on

other suppliers that provide material or components for those goods or

services. The U.S. is identified as the Country of Origin for approximately 96

percent of obligations for goods that DOD procured from fiscal years 2020

through 2024 based on dollar value. DOD officials recognize that they cannot

use FPDS to determine where components of goods that DOD procures are produced.

|

F-35 Joint Strike Fighter The F-35 is a fifth-generation fighter aircraft designed to replace a range of aging aircraft in the U.S. military services’ inventories. Seven partner nations—Australia, Canada, Denmark, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, and the United Kingdom—contribute to F-35 development, production, and sustainment.

Source: Department of Defense report and U.S. Air Force; S. King, Jr. | GAO‑25‑107283 |

For example, DOD is aware that FPDS does not contain complete information about F-35 suppliers. FPDS data show that from fiscal years 2020 to 2024, there were 115 active DOD contracts related to the F-35. Of those, the U.S. is identified as the Country of Origin for 114 contracts. According to DOD officials, FPDS does not include information on the subcontracts that the prime contractor, Lockheed Martin, enters with suppliers that provide subsystems, components, and raw materials for the aircraft. DOD, through Lockheed Martin, found that magnets included on some F-35s originated from China.

|

Microelectronics Microelectronics are very small devices, such as computer memory chips and sensors, that can process, store, and move data or signals. The Department of Defense (DOD) reported that microelectronics are a part of a wide variety of commercial and defense products—from cell phones, cars, and kitchen appliances to precision guided munitions, hypersonic weapons, and satellites. Microelectronics are also a central component of DOD’s advanced capabilities. While the microelectronics supply chain is global in nature, manufacturing is centralized in the Asia-Pacific region, and the adjunct industries that support manufacturing are globally dispersed.

Source: DOD reports and Patrick Daxenbichler/stock.adobe.com. | GAO‑25‑107283 |

Similarly, DOD cannot identify where all the microelectronics in the goods it procures are manufactured. According to our analysis of FPDS data from fiscal years 2020 to 2024, DOD procured $1.3 billion of electronic microcircuits, a type of microelectronics. The U.S. is identified in FPDS as the Place of Manufacture and Country of Origin for nearly 100 percent of those obligations. For example, Defense Microelectronics Activity officials told us that, of that amount, they procured over $400 million of a specific type of microcircuit from DOD-accredited trusted suppliers using commercial domestic foundry processes. These microcircuits were used to address defense-unique needs that could not be addressed by using commercially available off-the-shelf components.

However, DOD officials are concerned that commercial microelectronics that are used in DOD goods are coming from non-U.S. sources. According to DOD estimates, 88 percent of the production and 98 percent of the assembly, packaging, and testing of all microelectronics are performed overseas—primarily in Taiwan, South Korea, and China.

In addition to FPDS, the Defense Logistics Agency and the Defense Contract Management Agency also have their own data systems that include information on suppliers.[18] However, like FPDS, the systems are not intended to provide supply chain visibility.

DOD Has Not Taken Key Steps in Its Supply Chain Visibility Efforts

DOD is undertaking several efforts to collect and analyze data on its suppliers to help identify foreign dependency and other industrial base risks. However, it has obtained limited country-of-origin information from suppliers through these efforts. DOD identified actions it can take to better coordinate its efforts and share information across the department but has yet to identify resources, set priorities, and establish time frames for implementing these efforts. Additionally, DOD has not tested an alternative approach of using contract deliverables to collect additional information from suppliers, which leaves the department reliant on contractors voluntarily providing supplier information and provides little insight into possible costs of obtaining this information going forward.

DOD Efforts to Identify Country-of-Origin Information Have Had Limited Success

Various DOD organizations have initiated efforts to collect more data on companies in the defense supply chain, including the countries where suppliers are manufacturing their goods. In some cases, the organizations are using information from commercial supply chain tools to supplement the data they collect. DOD officials stated that the efforts have not provided enough visibility into the supply chain to help DOD proactively identify all foreign dependency risks, primarily because suppliers are not contractually required to provide such information to DOD.

Supply Chain Visibility Efforts

In the past 5 years, DOD initiated two primary efforts to obtain greater supply chain visibility. The first effort, Supply Chain Risk Evaluation Environment (SCREEn), is a supply chain risk tool. SCREEn is focused on weapon system risk identification, prioritization, and mitigation. The second effort—Defense Industrial Base Modeling and Analysis Project (DIBMAP)—is focused on gathering information on a few tiers of suppliers for a broad scope of weapon systems.

· SCREEn. In 2020, DOD initiated SCREEn to gain greater visibility into the F-35 microelectronics and propulsion supply chains, and to identify risks of intellectual property theft and foreign ownership, control, and influence. DOD has since expanded its goal to gain visibility into the suppliers for approximately 40,000 parts on the F-35. DOD is also expanding the SCREEn effort to include additional weapon system programs.[19]

DOD has been using a combination of government and commercial sources of data over the past 5 years to try to identify the F-35 suppliers.[20] SCREEn officials have also enlisted the help of the F-35 Joint Program Office for additional data. Through these efforts, DOD officials said that, as of April 2025, SCREEn has data on the country of origin for first- and second-tier suppliers for 30,000 of the 40,000 F-35 parts.

However, the officials estimated that they have collected country-of-origin information on less than 10 percent of all suppliers that provide components and raw materials for those parts. According to SCREEn officials, the F-35 Joint Program Office is pursuing ongoing efforts with industry to acquire additional parts and supplier data, but stated that there are challenges acquiring sub-tier data due to the lack of contractual requirements.

DOD officials said that SCREEn has not been used to proactively identify and mitigate foreign dependency risks yet. Instead, the officials said they have used the data to analyze alternative suppliers and assess supply chain risks across multiple weapon system programs. For example, SCREEn’s capabilities allowed the F-35 Joint Program Office to validate alternative suppliers for Chinese-made magnets that the prime contractor found on the aircraft in 2023 and 2024.[21] We discuss these magnets later in this report. DOD officials said SCREEn is still in development and the goal is for it to proactively identify risks and provide decision-makers with mitigation support.

· DIBMAP. In February 2023, the Deputy Secretary of Defense directed the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment to collect and analyze industrial base data for 110 weapon system programs—an effort referred to as DIBMAP.[22] DOD organizations were instructed to collect and submit data on the prime contractors and first- and second-tier suppliers for weapon systems. The purpose of the effort was to capture the data in a single authoritative record to guide acquisition and sustainment strategies, policies, and mitigation. The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment subsequently tasked the Industrial Base Policy office to oversee the effort in a March 2023 memorandum. The Under Secretary stated that the data collection should not result in any additional costs to DOD and that DOD should not modify contracts to collect the data.

The Industrial Base Policy office used a combination of data calls to program offices and sustainment data maintained by the Defense Logistics Agency to obtain the data. According to Industrial Base Policy officials, DOD generally met its goal for collecting data on prime contractors and the next two tiers of suppliers, and in some cases was able to collect more. For example, DOD was able to identify the prime contractor and three tiers of suppliers for the MQ-9 Reaper drone program. Furthermore, DOD took this opportunity to collect data on additional weapon systems when available. The mapping effort now has information on 732 weapon systems and programs.

Industrial Base Policy officials stated that the data can be used to identify a variety of industrial base risks at the top tiers of the supply chain, and that in general, they have not identified any foreign dependency risks of which they were not already aware. The officials also stated, however, that the supplier information collected so far does not provide enough visibility for DOD to identify or proactively address foreign dependency risks that exist at lower tiers in the supply chain. For example, DOD found that suppliers for the MQ-9 Reaper drone are primarily concentrated in the U.S. and some are in Europe. However, Industrial Base Policy officials said this does not fully represent the MQ-9 supply chain, as a separate DOD deep-dive analysis identified Chinese integration in the lower sub-tiers of the drone. As of March 2025, Industrial Base Policy officials said DIBMAP development is on pause until DOD determines the next steps for this effort.

Overall, as shown in figure 2, while DIBMAP provides more supply chain visibility than FPDS, generally it does not provide visibility into the lower-tier suppliers of raw materials, parts, or equipment where DOD officials said foreign dependency risks also exist.

Other DOD organizations have also initiated efforts to develop data systems and tools to increase supply chain visibility and identify potential risks. As shown in table 1, the efforts are generally early in development, apply only to that organization, and their success in collecting additional supplier information has varied.

|

System/Tool |

Initiation date |

Description |

|

Supply Chain Illumination and Program Risk |

2023 |

The Navy is developing the tool to help track and mitigate supplier risk and allow real-time analysis of supplier health. The tool incorporates some government and commercial data, but, according to Navy officials, the effort is facing challenges with collecting the data needed to proactively identify foreign dependency risks. |

|

FirstLook |

2023 |

The Air Force is using a combination of government and commercial data to quickly identify potential risks associated with individual suppliers. Air Force officials said they had conducted 1,731 FirstLooks as of April 2025. According to the officials, once potential risks are flagged via FirstLook, they can conduct enhanced analysis to collect additional information, including country-of-origin. |

|

Market Information Program |

2022 |

The Defense Logistics Agency used a third-party company to survey 63 suppliers across three classes of goods to collect supplier data. The suppliers provide aviation parts, clothing and textiles, and land and maritime parts. Five suppliers provided complete responses thus far, which, according to agency officials, has resulted in the agency reassessing the sub-tier supplier part of the program. |

|

Industrial Base Analysis Tool |

2004 |

The Army modeled the ammunition industrial base using government and commercial data. Army officials stated that they have significantly more information on this supply chain because DOD develops the designs and owns the data rights to the different types of ammunition. The Army used the tool to identify several Chinese sources in the 155 mm ammunition supply chain. |

Source: DOD documentation and GAO interviews with DOD officials. | GAO‑25‑107283

Commercial Supply Chain Tools

According to DOD officials, their organizations are using commercial supply chain tools to supplement their efforts to improve supply chain visibility. These tools use data analytics and rely on a variety of data sources, such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, bills of lading, press releases, and government and industry organizational membership information.[23]

Some DOD officials said the commercial tools have helped them identify relationships between suppliers and track changes in ownership of suppliers.[24] For example, according to officials from one weapon system program, they used a commercial supply chain tool to identify potential foreign dependency risks for rare earth minerals, dual use components, and semiconductor manufacturing processes. Another program received an alert from a commercial supply chain tool regarding a change of company leadership with suspected ties to a foreign supplier. This alert helped the program develop risk mitigation strategies.

DOD has raised concerns about the reliability of the information provided by the commercial tools. For example, in a 2024 Air Force assessment of three commercial supply chain tools, the Air Force found that supply chain illuminations done by commercial tools were 60 to 70 percent accurate. According to the assessment, the commercial tools identified risks in instances where no risk existed and failed to identify some suppliers in the supply chain. Additionally, we spoke to a program office official who found that there were too many unverified relationships between suppliers identified through a commercial tool, making the information unreliable.

DOD Has Not Taken Actions to Implement Recommendations That Could Improve Its Ability to Identify Foreign Dependency Risks

DOD and the Defense Business Board recently issued reports identifying actions DOD could take to improve its supply chain risk management approach and visibility efforts, but DOD has not taken key steps toward implementing these actions.[25] In February 2023, DOD reported that it lacked a coordinated, holistic framework to effectively manage the risks within the broader defense supply chain, including foreign sourced components.[26] Management of these risks is currently fragmented across numerous DOD organizations, with little cross-functional coordination or sharing of common supply chain information or initiatives.[27]

DOD has taken or is in the process of taking actions to address some of these challenges:

· The Assistant Secretary for Sustainment issued a taxonomy of supply chain risks and definitions to enable a common dialogue for sharing, assessing, and categorizing risk information across DOD.

· The Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Logistics worked with the General Services Administration on a blanket purchase agreement that allows DOD organizations to access commercial supply chain tools instead of these organizations contracting separately for the same tools.[28] In March 2025, nine vendors were awarded a blanket purchase agreement. In addition, the office is (1) finalizing a guidebook that will include information on supply chain risk management leading practices and mitigation strategies; and (2) identifying the various DOD systems and tools that store supply chain data with a goal of making the data available across DOD through a single platform, such as Advana.

· The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment issued a memorandum in October 2024 that authorized the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Sustainment to establish a new central organization to lead DOD-wide supply chain risk management integration, if needed. In November 2024, the new office—the Supply Chain Risk Management Integration Center—was established.

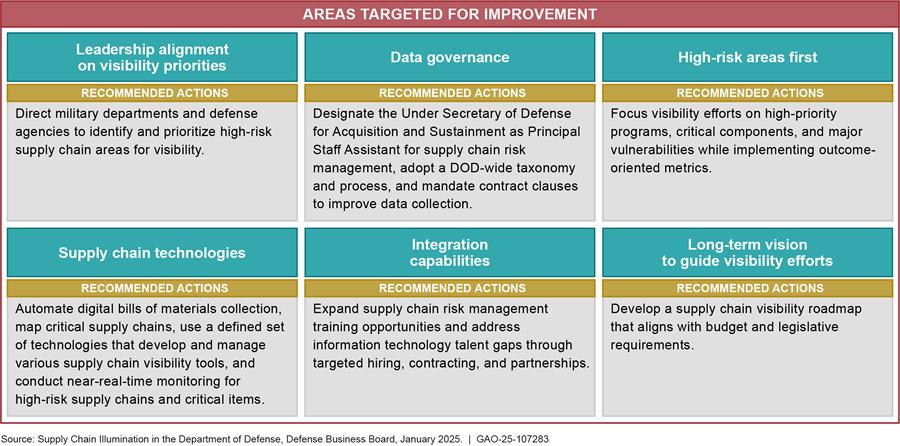

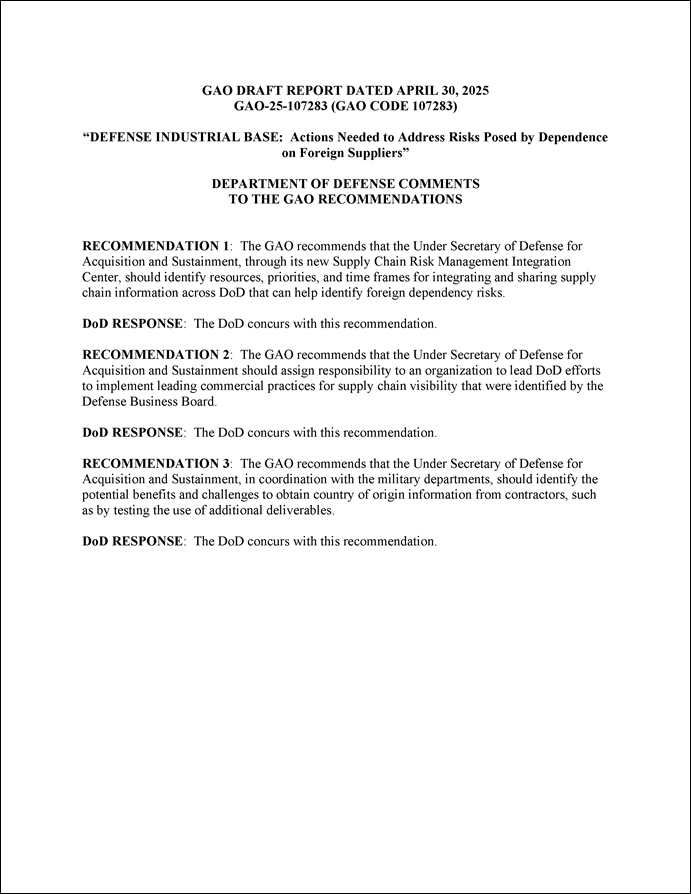

In January 2025, the Defense Business Board issued a report on DOD supply chain visibility. It assessed DOD’s current efforts and compared them to private-sector leading practices that the board identified.[29] The board identified six areas where DOD practices did not align with leading practices and made 12 recommendations for improvement. For example, the board recommended that DOD prioritize its visibility efforts and mandate the use of contract clauses that require data sharing. Figure 3 provides a summary of these recommendations.

Figure 3: Summary of Defense Business Board Recommendations for Improving Department of Defense (DOD) Supply Chain Visibility, January 2025

While DOD established a new office to lead the department’s supply chain risk management efforts, DOD officials stated that they have not identified resources, priorities, and time frames for the office to complete relevant actions. In addition, according to DOD officials, the department has not identified the responsible organization for determining the actions DOD plans to take to implement the Defense Business Board recommendations. DOD officials stated that they have not completed these actions because they need to ensure that the actions align with the current Secretary of Defense’s priorities.

Good practices for Enterprise Risk Management indicate that agencies should identify resources, priorities, and time frames and assign responsibilities to support risk management actions.[30] Without taking these actions as soon as practicable, DOD will be less able to identify and address foreign dependency risks.

DOD Has Not Tested an Alternative Approach for Collecting Country-of-Origin Data

DOD has not contractually obligated prime contractors to provide country-of-origin data that would help it obtain greater visibility into suppliers at the lower tiers of the supply chain. Efforts to collect information on sub-tier suppliers without this type of requirement have not been successful.

For example, in addition to the SCREEn effort described earlier, the Defense Logistics Agency is having difficulty mapping the supply chains across three classes of goods. Of the 63 suppliers it is trying to gather data from, 37 agreed to provide information, 22 declined to participate or were non-responsive, and four are still evaluating whether they will participate. Suppliers that declined to participate provided several reasons, including the absence of a contractual obligation to provide the information, the additional work it would be for them, limited resources to dedicate to this effort, and an unwillingness to share proprietary information. Defense Logistics Agency officials said limited supplier participation has negated any value in conducting supply chain analysis. They stated that obtaining additional supplier information would require use of contract clauses.

Some DOD officials we spoke with asserted that supplier information is readily available in enterprise resource planning systems that suppliers maintain to track inventory and determine when to reorder parts.[31] The officials explained that private sector companies have been successful in gaining greater visibility into their supply chains by requiring sub-tier suppliers to provide information from these systems. These DOD officials do not believe that requesting the information from suppliers would cost much more money. DOD officials said they are in the conceptual phase of developing contract clauses that would require additional information from suppliers.

However, this perception contrasted with the opinions of other DOD officials and industry representatives who said that DOD would incur significant cost increases if it required prime contractors to obtain information on all their suppliers. Specifically, they said it is difficult and expensive to get these data after a contract has been awarded. They suggested that DOD limit the scope of its data collection efforts to critical components and technologies, or to weapon acquisition programs that are early in the acquisition process. This is similar to the Defense Business Board’s recommendation in its study on DOD supply chain visibility, which stated that DOD should mandate contract clauses that require data sharing. Specifically, the study stated that DOD should start with contracts that are new or involve high-risk supply chain items.

Regardless of their perspectives on costs, DOD officials and industry representatives said some suppliers may not be willing to share their information or report foreign dependence problems even with the contract clauses. For example, they said that:

· Suppliers are concerned about the potential lack of safeguards to protect their proprietary information, which would have an impact on their business interests. A DOD official said this could be addressed by having suppliers provide information directly to DOD instead of to prime contractors.

· Suppliers are disincentivized to disclose potential foreign dependency risks because it could result in production stoppages while the risk is being investigated. For example, a DOD official said the F-35 program experienced 6-month production stoppages, in 2023 and 2024, when Chinese magnets were identified on the aircraft and had to be replaced. The official said DOD’s payments to the contractor stopped during these periods. DOD officials said DOD would likely need to determine the extent to which it could provide suppliers protection from liability or penalties when foreign dependency risks surface.

Although DOD is in the conceptual phase of developing potential contract clauses, it has not fully assessed whether this effort would address DOD and supplier concerns. Good practices for implementing an Enterprise Risk Management framework indicate that agencies need to consider the costs and benefits of proposed approaches for mitigating risks.[32] In DOD’s case, testing the use of contract requirements, such as new deliverables, could help DOD understand the cost of obtaining additional supplier information. This information could be used to

· identify foreign dependency risks;

· determine how to address concerns raised by suppliers that are reluctant to provide the information;

· assess costs to obtain the information; and

· determine how it could implement Defense Business Board recommendations for data sharing.

For example, the insights gained from the limited data gathered through the SCREEn effort show the potential to find and mitigate previously unknown foreign dependencies. Unless DOD tests the costs and challenges of requiring suppliers to provide foreign dependency information, it could be missing an opportunity to have greater insights that would help it to address the security and stability of its supply chain for critical materials and other goods it procures.

DOD Identified Supply Chain Priority Areas but Faces Challenges in Identifying Foreign Dependency Risks

DOD is taking steps to mitigate supply chain risks it identified, including foreign dependency, in designated priority areas. DOD programs identified the risks independently or through prime contractors’ self-disclosures rather than through the SCREEn and DIBMAP efforts described earlier. Examples in three supply chains—aviation, batteries, and kinetic capabilities—illustrate the foreign dependency risks that DOD faces and the methods it has used to identify and mitigate these risks.

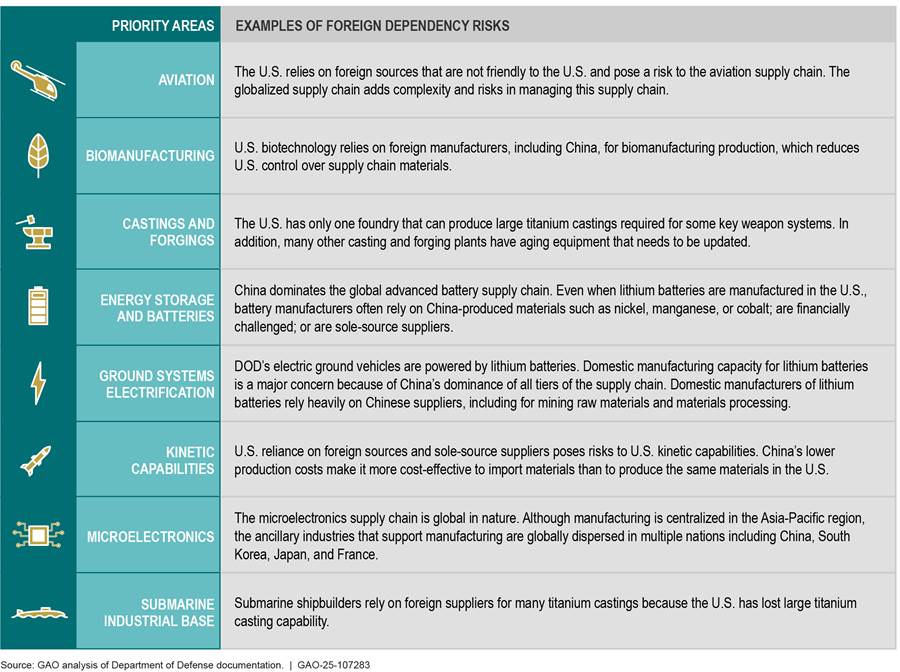

DOD Is Focused on Several Priority Areas to Mitigate Supply Chain Risks

DOD has focused on eight priority areas for mitigating defense supply chain risks since 2020. This effort is based on DOD’s own experiences and reflected in its report in response to Executive Order 14017.[33] Figure 4 identifies the eight priority areas with examples of foreign dependency risks for each area.

Figure 4: Department of Defense’s (DOD) Eight Supply Chain Priority Areas and Examples of Foreign Dependency Risks

DOD officials said they have several tools to mitigate foreign dependency risks once identified in the priority supply chain areas. These tools are (1) investments, (2) policy, (3) a stockpile of critical minerals, and (4) strategic partnerships and agreements with international partners and allies.

· Investments. DOD has three primary investment programs that it uses to mitigate foreign dependency risks. Defense Production Act Title III funds are used to establish, expand, maintain, or restore domestic production capacity for critical components and technologies.[34] Industrial Base Analysis and Sustainment investments are used to maintain or improve the health of essential parts of the defense industry by addressing critical capabilities. Manufacturing Technology investments are used to anticipate and close gaps in manufacturing capabilities. Altogether, DOD obligated about $6.5 billion for 828 projects from fiscal years 2020 through 2024. For example, DOD invested in projects to bring back domestic sourcing of critical chemicals to support kinetic capabilities; expand solid rocket motor production; and fund advanced manufacturing technology projects for sensors, radars, and optics.

· Policy. According to Industrial Base Policy officials, DOD is making changes to policies related to the procurement of some items, partially in response to legislative requirements. For example, the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 prohibits certain magnets in a defense platform that come from any part of the supply chain of China, Iran, North Korea, or Russia.[35] The Servicemember Quality of Life Improvement and National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2025 further prohibited DOD from procuring any covered semiconductor products and services with any entity that knowingly provides covered semiconductor products and services to Huawei, a company based in China.[36] It also stipulated that DOD coordinate a department-wide approach to establishing a battery strategy to further leverage the advancements of domestic and allied commercial battery industries.[37]

· Stockpile of critical materials. DOD has maintained the National Defense Stockpile to store materials—such as titanium and lithium—that are critical to defense and essential civilian needs in times of national emergency. We previously reported that DOD regularly held about 50 different types of materials in the stockpile between fiscal years 2019 and 2023, and that DOD is heavily reliant on foreign or single domestic sources of supply for other critical materials it does not hold.[38] For example, there were no domestic manufacturers for over half of the 99 materials DOD identified in shortfall in fiscal year 2023. Congress appropriated $175 million to DOD in fiscal years 2022 and 2024 to acquire additional materials.[39]

· Strategic partnerships and agreements with international partners and allies. The National Defense Industrial Strategy states that DOD must engage its partners and allies to expand global defense production and increase supply chain resilience to address foreign dependency risks. For example, the June 2024 Interim Implementation Report for the strategy stated that the Army opened a new modular metal parts facility operated by a Canadian firm in Mesquite, Texas, to increase domestic production of 155 mm ammunition to meet growing demand.[40] In another example, DOD awarded funds in May 2024 to two Canadian companies to build resilience in the cobalt and graphite supply chains. These are the first awards using an expanded definition of Defense Production Act domestic sources.[41]

Selected Examples Illustrate DOD’s Challenges with Identifying Foreign Dependency Risks

We selected three examples to illustrate the various foreign dependency challenges that DOD faces and the methods that it has used to identify and mitigate these risks. The examples are for specific weapons and goods in DOD’s priority areas of aviation (F-35 Joint Strike Fighter), energy storage and batteries (lithium batteries), and kinetic capabilities (155 mm ammunition).

· F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. The F-35 prime contractor, Lockheed Martin, identified prohibited Chinese magnets in the F-35 supply chain and notified DOD in 2023 and 2024. DOD subsequently paused manufacturing for several months to identify alternative suppliers. As part of its mitigation efforts, DOD issued two National Security Waivers to accept the F-35s with the magnets for national security purposes and determined that the magnets posed no safety risk.[42] Without these self-disclosures from Lockheed Martin, DOD may not have known that the magnets were made in China. As we discussed earlier in our report, DOD officials stated that they used SCREEn to identify alternative suppliers to provide the needed magnets.

During a site visit to the prime contractor, DOD program officials also identified Chinese-made robotic arms in the F-35 assembly line as coming from a German manufacturer now owned by a Chinese company. This discovery triggered a DOD investigation and other mitigation actions. For example, F-35 Joint Program Office officials said that DOD used SCREEn and a commercial supply chain company to analyze risks posed to the F-35. DOD concluded that there were no safety or quality impacts to the F-35.

F-35 Joint Program Office officials said that during its investigation into the robotic arms, DOD also identified some cybersecurity concerns. It mitigated these concerns by instructing Lockheed Martin to implement measures to ensure the vulnerability could not be exploited. To address the potential vulnerability, Lockheed Martin representatives said the robots were disconnected from the internet.

· Lithium batteries. DOD officials stated that DOD has started building domestic battery production capabilities and stockpiling certain types of lithium batteries to reduce reliance on foreign sources that are located primarily in China. Lithium is a critical material used in the production of batteries and supports many applications and weapon systems, including radios, ground combat vehicles, and aerial refueling drones. In November 2024, Office of the Secretary of Defense officials said that several U.S. companies produce some of these batteries and two additional U.S. companies are considering production in the U.S.

· 155 mm ammunition. DOD is taking steps to increase domestic production of 155 mm ammunition. According to DOD’s National Defense Industrial Strategy, the war in Ukraine increased demand for these shells.[43] We previously reported that the Army used supplemental funding and Defense Production Act Title III funding to pursue a planned increase in 155 mm ammunition production. According to DOD officials, DOD is increasing production from 168,000 to 1.2 million rounds per year. To help support this increase, the Army is qualifying additional suppliers for metal shells and metal forging capabilities.[44] Additionally, DOD has been establishing domestic sources for critical chemicals that are used to manufacture the artillery to reduce its reliance on China and other foreign countries for these materials.

Conclusion

DOD recognizes that there are serious national security implications for not knowing where components of the goods it procures are manufactured. This potentially includes losing access to critical materials for weapon systems. However, its recent initiatives to obtain greater visibility into its suppliers have been decentralized and produced mixed results, especially for suppliers at the lower tiers that provide parts, components, and raw materials.

DOD is pursuing efforts to better manage fragmentation by integrating its supply chain management efforts and sharing supplier information more efficiently across the department. These efforts can be bolstered by DOD implementing Defense Business Board recommendations, which provided actionable next steps DOD can take to further improve supply chain visibility based on commercial practices and that largely align with our observations. It is now incumbent on DOD to consider and adopt these actions by identifying the resources, priorities, and time frames necessary to implement them. Assigning a lead organization will also help ensure these recommendations are implemented and help DOD identify and mitigate risks.

While DOD has had some success asking for this information from contractors and has taken steps when foreign dependency issues are identified, the amount of information collected has been uneven and ad hoc, in part because contractors are not obligated to provide it. As the department works to expand its supply illumination efforts, it still has not determined whether and how to require additional information from contractors. Testing or piloting contract requirements, such as new deliverables that require contractors to provide supplier information, can help DOD determine factors such as the costs and benefits, level of information needed, and which supply chains to target. Unless DOD takes steps to test the use of contract requirements, it will continue to face risks with unknown foreign dependencies and will not know whether alternative contracting approaches are feasible and effective at gathering information necessary to mitigate these risks.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to DOD:

The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, through its new Supply Chain Risk Management Integration Center, should identify resources, priorities, and time frames for integrating and sharing supply chain information across DOD that can help identify foreign dependency risks. (Recommendation 1)

The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment should assign responsibility to an organization to lead DOD efforts to implement leading commercial practices for supply chain visibility that were identified by the Defense Business Board. (Recommendation 2)

The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, in coordination with the military departments, should identify the potential benefits and challenges of obtaining country-of-origin information from contractors, such as by testing the use of additional deliverables. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. In its comments, DOD concurred with all three recommendations. DOD’s letter is reprinted in appendix II.

We are providing copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, and to the Secretary of Defense and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov. If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact us at russellw@gao.gov, or wingert@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public

Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

William Russell

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

Tatiana Winger

Acting Director, International Affairs and Trade

The Conference Report for the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to report on the degree to which the Department of Defense (DOD) is dependent on entities located in foreign countries for the procurement of certain end items and components essential for national security, which we refer to as “goods.”[45] Additionally, the House Report accompanying the legislation contained a similar provision for us to examine DOD processes for determining whether it is procuring noncombat goods from China and considering alternate sources, including domestic manufacturers, when there are concerns about the manufacturing origin of these goods.[46] Our report (1) describes the information that government procurement data contain on the country of origin of goods that DOD procures, (2) assesses the extent to which DOD is taking action to collect additional country-of-origin data, and (3) describes DOD’s efforts to mitigate foreign dependency risks.

To describe the information that government procurement data contain on the country of origin of goods that DOD procures, we analyzed relevant data contained in the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) from fiscal years 2020 through 2024. We conducted an assessment on the FPDS data to ensure accuracy and data reliability. We originally identified six FPDS data fields that contained information on foreign sourcing. We determined that two of those fields were relevant for this review—Place of Manufacture, and Country of Origin. We excluded four data fields because they did not identify the country of origin or where the goods were manufactured—Vendor Country; Foreign Entity; Foreign Owned; and Principal Place of Performance.[47] We also analyzed FPDS data from fiscal years 2020 through 2024 for the F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter program, microelectronics, and microcircuits to illustrate the type of foreign sourcing data that are included in FPDS.

We interviewed officials from throughout DOD on other data systems that identify the country of origin for goods that DOD procures. This included officials from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Industrial Base Policy, the Air Force, Army, Navy, Defense Logistics Agency, Defense Contract Management Agency, and other organizations.[48]

To assess the extent to which DOD is taking actions to collect additional country-of-origin data, we analyzed pertinent documents on new DOD initiatives, including guidance, project plans, data calls, and briefings. We evaluated various efforts across DOD to determine the government and commercial data sources used to collect supplier information and how much additional visibility DOD has gained into its supply chains. We assessed the two primary DOD efforts to improve supply chain visibility over the past 5 years, based on DOD documents and interviews with DOD officials: (1) Industrial Base Policy’s Defense Industrial Base Modeling and Analysis Project (DIBMAP), and (2) the Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office’s Supply Chain Risk Evaluation Environment (SCREEn) tool. Additionally, we assessed the Defense Logistics Agency’s Market Information Program, the Army’s Industrial Base Analysis Tool, the Navy’s Supply Chain Illumination and Program Risk tool, and the Air Force’s FirstLook assessments.

We interviewed officials engaged in the improvement efforts, including those in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Industrial Base Policy, the Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office, the Defense Logistics Agency, and the Defense Contract Management Agency. Through these interviews, we identified their roles, responsibilities, and views on the benefits and challenges of DOD’s efforts, as well as additional actions needed to improve supply chain visibility.

To determine the type of information that DOD is able to collect from commercial supply chain tools, we first interviewed officials from 10 DOD offices, including programs residing under the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment and the offices of the service acquisition executives from the Army, Air Force, and Navy. This also allowed us to get their perspective on the value of the tools. To identify examples of programs that have used commercial supply chain tools, we also solicited information through our annual assessment of DOD’s costliest weapon system programs for 2025 and received nongeneralizable responses from 65 weapon system programs.

We received confirmation from 10 programs that they had used commercial supply chain tools. We sent follow-up questions to nine offices to determine (1) their purpose for using the commercial supply chain tools; (2) whether the tools helped them identify any potential foreign dependency risks; and (3) what mitigations, if any, they had taken as a result of identifying foreign dependency risks. Additionally, we spoke with representatives from one prime contractor, Lockheed Martin, to understand their experiences and challenges with using commercial tools to identify foreign dependency risks. While this one contractor is not representative of the experience of others, the perspectives of a contractor provided important insights in this area.

To describe DOD’s efforts to mitigate foreign dependency, we analyzed information in several DOD reports and strategy documents to determine what the specific risks were and actions taken or planned to mitigate them. The documents included

· DOD’s National Defense Industrial Strategy;

· Securing Defense-Critical Supply Chains: An Action Plan Developed in Response to President Biden’s Executive Order 14017;

· annual Industrial Capability Reports published from fiscal years 2020 through 2023;[49] and

· the National Defense Industrial Strategy and implementation reports.

DOD identified eight priority areas for mitigating defense supply chain risks, of which we selected three for additional analysis—aviation, energy storage and batteries, and kinetic capabilities. The other five priority areas are biomanufacturing, castings and forgings, ground systems electrification, microelectronics, and the submarine industrial base. From the three priority areas, we selected three examples—the F-35 fighter jet, lithium batteries, and 155 mm ammunition—for further analysis based on their identification by DOD as included in priority areas in the fiscal year 2021 Industrial Capabilities Report or identified in Executive Order 14017.[50] We selected the priority areas and examples based on interviews with DOD officials as they illustrate the various risks that DOD faces and the methods that it has used to identify and mitigate these risks, but are not generalizable to the other priority areas.

We interviewed DOD officials on actions taken to address foreign dependency, including officials from the Office of Industrial Base Policy, the military services, the Defense Logistics Agency, and the F-35 Joint Program Office, as well as a prime contractor representative for the F-35. Through these interviews, we collected and analyzed information on DOD’s current mitigation efforts and proposals to implement additional mitigation efforts to reduce foreign dependency.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

William Russell, russellw@gao.gov, and Tatiana Winger, wingert@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contacts named above, Alissa Czyz, Director; Cheryl Andrew, Assistant Director; Christina Werth, Assistant Director; Gina Hoffman, Assistant Director; Sameena Ismailjee, Analyst in Charge; Lorraine Ettaro; Suellen Foth; Edward Harmon; Almir Hodzic; Lisa Shibata; Filip Stojkovski; Anne Louise Taylor; Seyda Wentworth; and Adam Wolfe made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]In response to an Executive Order on strengthening the U.S. defense industrial base, DOD issued a report in September 2018 in which it assessed its industrial base risks. DOD identified nearly 300 risks across 16 defense industrial base sectors. The report identified foreign dependency as a contributor to DOD supply chain insecurity. See Department of Defense, Assessing and Strengthening the Manufacturing and Defense Industrial Base and Supply Chain Resiliency of the United States (Report to President Donald J. Trump by the Interagency Task Force in Fulfillment of Executive Order 13806). See Exec. Order 13806, 82 Fed. Reg. 34597 (July 21, 2017).

[2]Department of Defense, National Defense Industrial Strategy, Implementation Plan for FY25 (Oct. 2024).

[3]H.R. Rep. No. 118-301, at 1148 (2023) (Conf. Rep.).

[4]H.R. Rep. No. 118-125, at 253-54 (2023).

[5]The fiscal year 2021 Industrial Capabilities Report, published in March 2023, was the most recent report available at the time of this review.

[6]GAO, Defense Supplier Base: Challenges and Policy Considerations Regarding Offshoring and Foreign Investment Risks, GAO‑19‑516 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 5, 2019).

[7]GAO, Defense Industrial Base: Integrating Existing Supplier Data and Addressing Workforce Challenges Could Improve Risk Analysis, GAO‑18‑435 (Washington D.C.: June 13, 2018).

[8]DOD, National Defense Industrial Strategy, January 2024.

[9]Exec. Order No. 14017, 86 Fed. Reg. 11849 (Mar. 1, 2021).

[10]Department of Defense, Securing Defense-Critical Supply Chains: An action plan developed in response to President Biden’s Executive Order 14017 (Feb. 2022).

[11]Pub. L. No. 116-92, § 845 (2019); 10 U.S.C. § 2501, recodified at 10 U.S.C. § 4811.

[12]Advana is DOD’s enterprise data and analytics platform, which provides DOD users with data from more than 400 DOD business systems, along with tools, services, and analytics to enable data-based decision-making. In July 2024, the Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office announced that Advana support would transition from a single provider to multiple providers, with the intent to seek formal solicitations after September 2024. DOD officials said that Advana development remains paused because the contract was up for recompete.

[13]Senior officials include the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics for Air Force and Space Force programs; the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Acquisition, Logistics, and Technology for Army programs; and the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition for Navy and U.S. Marine Corps programs.

[14]FPDS provides details for federal contracts from weapon systems to noncombat goods. Its data go back nearly 50 years and span over several federal agencies. The system includes information on prime contractor supplier names, type of work, location, and contract amounts.

[15]DOD uses FPDS foreign sourcing data for various reports submitted to Congress, including the Source Content for Major Defense Acquisition Programs reports and annual Purchases from Foreign Entities reports.

[16]Buy American Act, Pub. L. No. 72-428 (1933), as amended, codified at 41 U.S.C. §§ 8301-8305. The Buy American statute generally requires federal agencies to purchase domestic end products for use in the United States. Federal Acquisition Regulation 25.101. A manufactured product is defined generally as domestic if it was manufactured in the United States and the cost of the components mined, produced, or manufactured in the United States is greater than 60 percent of the total cost of the components, subject to exceptions. Federal Acquisition Regulation 25.003.

[17]Domestic end products are defined, with exceptions, as unmanufactured products mined or produced in the United States; and end products manufactured in the United States, provided that (a) the product is a commercially available off-the-shelf item; or (b) the cost of the components mined, produced, or manufactured in the United States exceeds 60 percent of the cost of all its components, except that the percentage will be 65 percent for items delivered in calendar years 2024 through 2028 and 75 percent for items delivered starting in calendar year 2029. Federal Acquisition Regulation 25.003.

[18]The Defense Logistics Agency’s Enterprise Business System includes visibility of prime contractor data for parts it is buying, which is then shared with FPDS. The Defense Contract Management Agency’s Industrial Base Integrated Data System is a repository of defense industry data used to manage data pertaining to suppliers, products, capabilities, and associated relationships throughout the Defense Industrial Base.

[19]DOD also plans to use SCREEn to satisfy Section 856 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, which requires DOD to pilot a program to analyze, map, and monitor supply chains for up to five weapon systems and authorizes the pilot program to use DOD and commercial supply chain tools. Pub. L. No. 118-31, (2023). In addition to the F-35 program, DOD plans to include the MV-22C Osprey, MIM-104 Patriot missile system, C-5C/M Super Galaxy, and Standard Missile 6 for SCREEn analysis.

[20]DOD officials stated that SCREEn’s data are integrated into Advana, DOD’s enterprise-wide data platform.

[21]The contractor disclosed the integration of the magnets in 2022 and DOD issued a national security waiver in 2023.

[22]The Deputy Secretary of Defense instructed the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment to lead the DIBMAP effort with the military services, Defense Contract Management Agency, and the Defense Logistics Agency providing it the necessary supplier information. The Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office was instructed to help integrate the information into Advana.

[23]A bill of lading is a commercially available document issued by a carrier to a shipper, signed by the captain, agent, or owner of a vessel, furnishing written evidence regarding receipt of the goods, the conditions on which transportation is made (contract of carriage), and the engagement to deliver goods at the prescribed port of destination to the lawful holder of the bill of lading. U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Bill of Lading Document (Aug. 15, 2024).

[24]To identify examples of programs that have used commercial supply chain tools, we solicited information through our annual assessment of weapon systems programs for 2025. Ten programs reported they had used commercial supply chain tools. We sent follow up questions to the offices for nine of the 10 programs to determine (1) their purpose for using the commercial supply chain tools; (2) whether the tools helped them identify any potential foreign dependency risks; and (3) what mitigations, if any, they had taken as a result of identifying foreign dependency risks.

[25]Department of Defense, Defense Business Board, Business Transformation Advisory Subcommittee, Supply Chain Illumination in the Department of Defense (Jan. 7, 2025). Department of Defense, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Sustainment, Recommended Inputs to Strategic Documents (Jan. 2024).

[26]Department of Defense, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Sustainment, Supply Chain Risk Management Framework Project Report – Phase I (Feb. 15, 2023).

[27]Fragmentation refers to those circumstance in which more than one federal agency (or more than one organization within an agency) is involved in the same broad area of national need. GAO, 2024 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Billions of Dollars in Financial Benefits, GAO‑24‑106915 (Washington, D.C.: May 15, 2024).

[28]A blanket purchase agreement is a simplified method of filling anticipated repetitive needs for supplies or services with qualified sources of supply. Federal Acquisition Regulation 13.303-1.

[29]Department of Defense, Defense Business Board, Business Transformation Advisory Subcommittee, Supply Chain Illumination in the Department of Defense (Jan. 7, 2025).

[30]Our Enterprise Risk Management framework is a forward-looking management approach that allows agencies to assess threats and opportunities that could affect the achievement of their goals. It includes the following six elements: (1) align Enterprise Risk Management process to goals and objectives; (2) identify risks; (3) assess risks; (4) select risk response; (5) monitor risks; and (6) communicate and report on risks. GAO, Enterprise Risk Management: Selected Agencies’ Experiences Illustrate Good Practices in Managing Risk, GAO‑17‑63 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 1, 2016).

[31]Enterprise resource planning is a software system that helps organizations streamline their core business processes—including finance, manufacturing, supply chain, sales, and procurement—with a unified view of activity. For supply chain management, enterprise resource planning systems help with planning, procurement, manufacturing, inventory management, warehouse management, and order management. There are numerous commercial providers of enterprise resource planning systems in the market.

[32]GAO, Enterprise Risk Management: Selected Agencies’ Experiences Illustrate Good Practices in Managing Risks, GAO‑17‑63 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 1, 2016).

[33]Department of Defense, Securing Defense-Critical Supply Chains: An action plan developed in response to President Biden’s Executive Order 14017 (Feb. 2022).

[34]Defense Production Act of 1950, Pub. L. No. 81-774, (1950) (codified as amended at, 50 U.S.C. §§ 4501–4568).

[35]Section 871 amended 10 U.S.C. § 2533c (recodified at 10 U.S.C. § 4872), which prohibits acquisition of sensitive materials from non-allied foreign nations, unless an exception applied. Pub. L. No. 115-232 (2018). The materials include samarium-cobalt magnets; neodymium-iron-boron magnets; tungsten metal powder; and tungsten heavy alloy or any finished or semifinished component containing tungsten heavy alloy. The covered nations include China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia.

[36]Pub. L. No. 118–159, § 853 (2024).

[37]Pub. L. No. 118–159, § 883 (2024).

[38]GAO, National Defense Stockpile: Actions Needed to Improve DOD’s Efforts to Prepare for Emergencies, GAO‑24‑106959 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2024).

[39]The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 appropriated $125 million for fiscal year 2022. Pub. L. No. 117-103, § 8035 (2022). The Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2024 appropriated $50 million for fiscal year 2024. Pub. L. No. 118-47, § 8034 (2024).

[40]The facility is operated by General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems in Canada.

[41]Section 1080 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 expanded the definition of a domestic source for Defense Production Act Title III investments. Pub. L. No. 118-31 (2023); 50 U.S.C. § 4552(7). This provision allows qualifying companies in the United Kingdom and Australia, in addition to the United States and Canada, to be considered as domestic sources under the Defense Production Act.

[42]10 U.S.C. § 4863(a) requires that, absent an exception, DOD may not acquire an end item, including aircraft, or components thereof, containing specialty metals not melted or produced in the United States. 10 U.S.C. § 4863(k) provides the authority for the Secretary of Defense to accept an end item containing noncompliant materials under a national security waiver. This prohibition is implemented in DOD’s Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS). See DFARS 225.7003; 252.225-7009. The DFARS provides uniform acquisition policies and procedures for DOD. The 2023 and 2024 F-35 National Security Waivers state that DFARS clause 252.225-7009 is included in DOD’s F-35 contracts.

[43]The U.S. has provided Ukraine more than 3 million rounds of 155 mm ammunition. Ukraine uses this large-caliber artillery shell for its weapon systems, such as howitzers.

[44]GAO, Ukraine: Status and Challenges of DOD Replacement Efforts, GAO‑24‑106649 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 30, 2024).

[45]H.R. Rep. No. 118-301, at 1148 (2023) (Conf. Rep.).

[46]H.R. Rep. No. 118-125, at 253-54 (2023).

[47]We previously identified the six Federal Procurement Database System data fields on foreign sourcing. See GAO, International Trade: Foreign Sourcing in Government Procurement, GAO‑19‑414 (Washington, D.C.: May 30, 2019).

[48]Other DOD organizations include the Deputy Secretary of Defense for Logistics, Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office, and Defense Pricing, Contracting, and Acquisition Policy.

[49]The fiscal year 2021 Industrial Capabilities Report, published in March 2023, was the most recent report available at the time of this review.

[50]Department of Defense, Fiscal Year 2021 Industrial Capabilities Report to Congress (Mar. 2023). Exec. Order 14017, 86 Fed. Reg. 11849 (Feb. 24, 2021).