MEDICAID

Enrollment in and CMS Oversight of Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group

Committee on Finance

U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107286. For more information, contact Jessica Farb at (202) 512-7114 or FarbJ@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107286, a report to the Ranking Member, Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate

Enrollment in and CMS Oversight of Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group

In Why GAO Did This Study

Individuals who experience foster care are more likely to have complex health needs as compared with the general population, according to CMS. Over the past decade, Congress has established and expanded Medicaid coverage options for individuals formerly in foster care that meet certain criteria.

GAO was asked to provide information about efforts to enroll individuals formerly in foster care into Medicaid. Among other things, this report addresses the size of the Former Foster Care Children eligibility group; barriers this population faces enrolling in Medicaid, and selected states’ approaches to addressing them; and CMS oversight of enrollment in the Former Foster Care Children eligibility group.

GAO analyzed reliable 2023 Medicaid eligibility and age data from 46 states and the District of Columbia. GAO also analyzed CMS and selected states’ documents; and interviewed officials from CMS, selected states’ Medicaid and child welfare agencies, and organizations that work with individuals formerly in foster care or on issues related to aging out of foster care and Medicaid. GAO selected these states—Arizona, California, Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, and Ohio—based on factors such as variation in the number of individuals in foster care and geography. GAO also conducted a site visit to Georgia.

What GAO Found

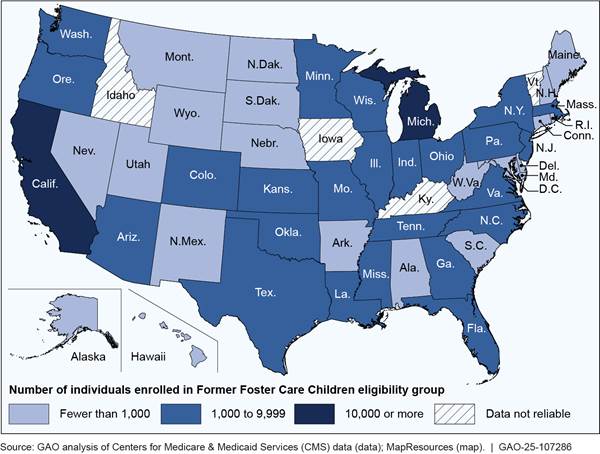

Medicaid is a joint state-federal health care financing program for certain low-income and medically needy individuals. The program covers certain individuals who aged out of foster care, ages 18 to 26, through the Former Foster Care Children eligibility group, regardless of their income. At least 112,000 individuals were enrolled in this group during 2023, according to GAO analysis of Medicaid data. These individuals comprised less than 1 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries.

Number of Individuals Enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children Medicaid Eligibility Group in 2023

Note: For more details, see figure 2 in GAO-25-107286.

Individuals who have aged out of foster care can face barriers to enrolling in Medicaid and maintaining coverage. For example, they may miss Medicaid outreach if they change addresses frequently due to unstable housing, or avoid seeking assistance due to mistrust of state agencies, according to officials in selected states and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which oversees Medicaid. States’ approaches to address these barriers include using text messaging to reach individuals and collaborating with trusted organizations that have supported individuals in foster care.

CMS provided guidance to states on enrolling individuals formerly in foster care in Medicaid, and conducted general monitoring of Medicaid eligibility, which includes the Former Foster Care Children eligibility group.

Abbreviations

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

FFCC |

Former Foster Care Children |

|

SUPPORT Act |

Substance Use-Disorder

Prevention that Promotes |

|

T-MSIS |

Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 10, 2025

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

Dear Mr. Wyden:

Approximately 18,500 individuals aged out of foster care in fiscal year 2022, reaching the legal age of adulthood without being reunified with their families or placed in new permanent families.[1] Individuals who experience foster care are more likely to have complex health needs, such as behavioral health conditions and disabilities, as compared with the general population.[2]

While in foster care, nearly all individuals are eligible for Medicaid, a joint federal-state health care financing program for certain low-income and medically needy individuals. At the federal level, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) oversees the Medicaid program and the Administration for Children and Families oversees the federal foster care program.[3] State Medicaid and child welfare agencies administer the day-to-day operations of these programs.[4] These state agencies collaborate to provide health care coverage and services to individuals in foster care; however, after leaving foster care these individuals can face barriers accessing health care coverage, according to CMS.

Eligibility for Medicaid is established by a series of federal and state laws and regulations. Under federal law, states must cover certain mandatory groups, such as individuals in federally funded foster care, and they have the option to cover certain other groups of individuals. Over the past decade, Congress has established and expanded Medicaid coverage options for individuals formerly in foster care. First, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act created the mandatory Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) Medicaid eligibility group, which required states to provide coverage for certain individuals up to age 26 who aged out of foster care in that state, effective January 1, 2014.[5] Second, the 2018 Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act) expanded the FFCC eligibility group to require states to cover individuals who aged out of foster care in a different state, effective January 1, 2023.[6]

You asked us to provide information about efforts to enroll individuals formerly in foster care into Medicaid. In this report, we

1. describe the size and demographic characteristics of Medicaid’s FFCC eligibility group;

2. describe the barriers individuals formerly in foster care face when enrolling in Medicaid, and approaches selected states used to address them;

3. describe how selected states implemented SUPPORT Act changes related to enrolling individuals in Medicaid’s FFCC eligibility group; and

4. examine CMS oversight of states’ efforts to enroll individuals in Medicaid’s FFCC eligibility group.

To describe the size and demographic characteristics of Medicaid’s FFCC eligibility group, we analyzed 2023 data from CMS’s Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS).[7] In all states and the District of Columbia for which T-MSIS data were reliable, we analyzed these data to determine the number and age of beneficiaries enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group. In eight selected states—Arizona, California, Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, and Ohio—we further analyzed T-MSIS data to compare race/ ethnicity, gender, and residence in an urban or rural area for FFCC beneficiaries to all other similarly aged Medicaid beneficiaries. We selected these states to obtain variation in the number of individuals in foster care and geographic location, among other things.

We did not independently verify the accuracy of the T-MSIS data; however, we took steps to assess the reliability of the data. We assessed the reliability of T-MSIS data by reviewing documentation, such as technical documentation from CMS describing the data and CMS’s assessment of its quality, checking the T-MSIS data for obvious errors and omissions, and interviewing CMS and state officials to resolve any identified discrepancies. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting objectives and accounted for any limitation or discrepancy in these data during our analyses. For example, for our analysis on the number and age of beneficiaries enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group, we determined the data were sufficiently reliable for 46 states and the District of Columbia.[8] For our analysis of data for our selected states on race/ ethnicity, gender, and residence in an urban or rural area, we excluded New York State. New York State’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials. (See app. I for more detail on the scope and methodology for our T-MSIS data analysis, including steps we took to assess the reliability of the T-MSIS data.)

To describe the barriers individuals formerly in foster care face when enrolling in Medicaid and selected states’ approaches to address them, we reviewed documentation from CMS, the Administration for Children and Families, Medicaid and child welfare agencies in the eight selected states, and organizations that work with individuals formerly in foster care or on issues related to aging out of foster care and Medicaid. We also interviewed officials from these entities, as well as a group of individuals formerly in foster care as part of a site visit to Georgia, about these topics. The information we obtained from the selected state agencies, organizations, and individuals formerly in foster care cannot be generalized.

To describe how selected states implemented SUPPORT Act changes related to enrolling individuals in Medicaid’s FFCC eligibility group, we reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from CMS and the eight selected states about requirements for states and actions they took to implement these changes. The information we obtained from the selected state agencies cannot be generalized.

To examine CMS oversight of states’ efforts to enroll individuals in Medicaid’s FFCC eligibility group, we reviewed CMS documentation and interviewed CMS officials. We compared this oversight to CMS’s responsibility for ensuring states’ compliance with Medicaid requirements and to federal internal control standards for implementing internal control activities and risk assessments.[9]

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Medicaid Eligibility Processes

To qualify for Medicaid coverage, individuals generally must fall within certain categories or populations, and must meet the eligibility criteria associated with an eligibility group that is covered by the state.[10] We refer to this collectively as the individual’s basis of eligibility. Depending on the eligibility group, individuals must meet certain financial eligibility criteria, such as having income below specified levels. Individuals must also meet nonfinancial criteria, such as citizenship and state residency requirements.

As the day-to-day administrators of the Medicaid program, states are generally responsible for assessing applicants’ eligibility for and enrolling eligible individuals into Medicaid. These responsibilities include verifying individuals’ eligibility at the time of application, performing redeterminations of eligibility, and promptly disenrolling individuals who are no longer eligible. States generally have flexibility in the sources of information they use to verify applicants’ Medicaid eligibility.[11] However, to the extent practicable, states must use third party sources of data for these verifications prior to requesting documentation from the applicant. Once a state determines that an individual meets relevant eligibility criteria, the state enrolls the individual into Medicaid, typically under one basis of eligibility.[12]

At the federal level, CMS is responsible for overseeing states’ compliance with Medicaid requirements. Federal laws and regulations establish certain eligibility and enrollment requirements, and CMS provides guidance and technical assistance to states to ensure they are adhering to them. CMS also may offer states flexibilities to waive certain of these requirements, such as allowing states to extend Medicaid coverage to populations that are not otherwise eligible. In addition, CMS is responsible for monitoring the accuracy and timeliness of states’ Medicaid eligibility determinations. CMS does this through two programs:

· The Medicaid Eligibility Quality Control program is implemented by states and overseen by CMS to monitor the accuracy and timeliness of Medicaid eligibility determinations and identify methods to reduce and prevent errors related to incorrect eligibility determinations.

· The Payment Error Rate Measurement program is implemented by CMS to estimate improper payments by, among other things, measuring errors in state determinations of Medicaid eligibility.[13]

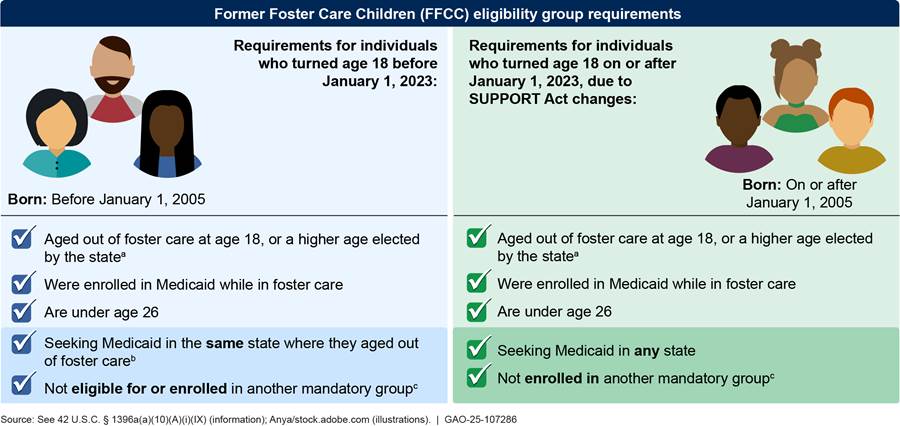

FFCC Eligibility Group

Most individuals who have aged out of foster care and are 18 through 25 years old are eligible for the mandatory FFCC Medicaid eligibility group, regardless of income.[14] The SUPPORT Act, enacted in 2018, made several changes to the FFCC group’s eligibility criteria. Specifically, the SUPPORT Act began requiring states to cover eligible individuals who aged out of foster care in any state, as opposed to limiting eligibility to individuals who aged out of foster care in that same state. In addition, the SUPPORT Act began permitting states to enroll eligible individuals in the FFCC group even if they are eligible for certain other mandatory groups, such as groups for caretakers or pregnant people.[15] The legislation specified that these changes would apply to foster youth who turn 18 years old on or after January 1, 2023.[16] As a result, the current eligibility criteria that apply to former foster youth who turned 18 before January 1, 2023, are different than the criteria that apply to younger individuals. (See fig. 1.)

Notes: There is no income limit for the FFCC eligibility group. States may receive approval from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to waive certain eligibility requirements for this group. The Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act) changed Medicaid FFCC eligibility requirements effective for individuals who turned age 18 on or after January 1, 2023. See Pub. L. No. 115-271, 1002, 132 Stat. 3894, 3902 (2018). As a result, the current eligibility criteria that apply to former foster youth who turned 18 before January 1, 2023, are different than the criteria that apply to younger individuals. Beginning January 1, 2031, the FFCC group will only have one set of eligibility criteria because all individuals who turned age 18 prior to January 1, 2023, will have turned age 26—the maximum age for FFCC eligibility.

aStates may elect to end federally funded foster care at age 18 or an older age through age 20. In states that end such assistance at an age above 18, CMS considers an individual who is in foster care upon turning age 18 and who ages out of foster care prior to reaching the state’s maximum age for foster care is eligible for the FFCC group provided they meet the other eligibility requirements.

bIn addition, CMS gives states the option to cover individuals who were placed by their state in foster care in another state (and are otherwise eligible).

cThe other mandatory eligibility groups include eligibility groups for children under age 19, parent or caretaker relatives, and pregnant people, but not the adult group that is described in section 1902(a)(10)(A)(i)(VIII) of the Social Security Act. Individuals eligible for both the FFCC eligibility group and the adult group must be enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group.

CMS has allowed states to waive certain requirements for the FFCC eligibility group to expand coverage and streamline enrollment for individuals formerly in foster care through demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act (section 1115 demonstrations) and waivers issued under section 1902(e)(14)(A) of the act (section 1902(e)(14) waivers). For example:

· Section 1115 demonstrations allow states to cover individuals who aged out of foster care in another state and turned age 18 prior to January 1, 2023.[17] According to CMS, six states had newly requested this authority while implementing the SUPPORT Act changes. As of January 2025, three states’ requests were approved.[18]

· Section 1902(e)(14) of the Social Security Act allows the Department of Health and Human Services to waive certain Medicaid requirements, such as the requirement for states to apply different eligibility rules based on when an individual turned age 18, under certain circumstances.[19] According to CMS officials, these waivers were used temporarily following the COVID-19 public health emergency while states worked to come into compliance with the SUPPORT Act changes or waited for approval of a section 1115 demonstration. According to CMS officials, as of September 2024, six states received waiver authority to do so.

In general, individuals who age out of foster care and remain in the state may be enrolled in the FFCC Medicaid eligibility group without having to take action. Officials from all eight selected states we interviewed said that child welfare agency staff or the Medicaid enrollment system notifies Medicaid eligibility staff that the individual is aging out of foster care.[20] Medicaid eligibility staff then review the information to redetermine the individual’s eligibility, and change their enrollment from the eligibility group for individuals currently in foster care to the FFCC eligibility group (or another group for which they are eligible).[21] Conversely, individuals who were in foster care in a different state must apply for Medicaid through the standard application process, according to Medicaid officials in our selected states. All our selected states’ Medicaid applications include a question asking whether the applicant was in foster care.

|

Aging Out of Foster Care According to officials we interviewed in eight selected states, child welfare agency caseworkers inform individuals aging out of foster care that they may be eligible for Medicaid. This occurs during the transition planning process, which must take place at least 90 days before the individual ages out of foster care. Child welfare agency caseworkers work with these individuals to develop a transition plan, which documents information, such as where they will live or work, and must include information on health insurance options, such as Medicaid. Source: 42 U.S.C. 675(5)(H) and GAO analysis of interviews with state child welfare agency officials. | GAO‑25‑107286 |

As with all Medicaid beneficiaries, states generally must redetermine eligibility for those enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group once every 12 months, or whenever it has reliable information about a change in circumstances that may affect the beneficiary’s eligibility.[22] According to CMS officials, in making this redetermination, states generally only need to verify that a FFCC beneficiary is still a resident of the state and under age 26. This is because the other eligibility criteria specific to the FFCC eligibility group—prior foster care status and Medicaid enrollment—are not subject to change; thus, states do not need to reverify these criteria. In addition, while states have flexibility in the sources they use to verify a beneficiary’s eligibility, CMS regulations require that states attempt to redetermine eligibility without contacting the individual if possible, and if requesting information, request only the information needed to determine eligibility.[23] CMS has issued various guidance following the COVID-19 public health emergency reminding states they must attempt to renew eligibility for beneficiaries based on available information, without requiring information from them.[24] If the state is not able to renew an individual based on available information, the state must send the individual a prepopulated renewal form. If the state determines that an individual is no longer eligible for the FFCC eligibility group, the state must assess the individual’s eligibility for other Medicaid eligibility groups prior to terminating coverage.[25]

At Least 112,000 Beneficiaries Were in Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group in 2023; Larger Percentages Lived in Urban Areas than Other Medicaid Beneficiaries

Beneficiaries in the Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group Comprised Less Than 1 Percent of States’ Medicaid Beneficiaries in 2023, Most Were Ages 21 Through 25

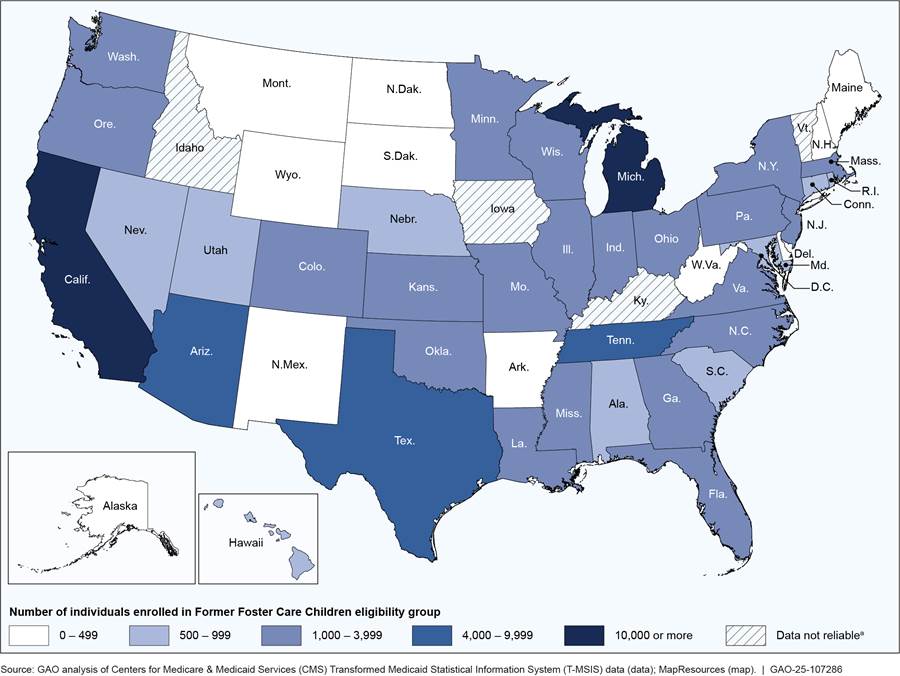

Across 46 states and the District of Columbia, there were at least 112,000 beneficiaries enrolled in the FFCC Medicaid eligibility group for at least one month in 2023, according to our analysis of T-MSIS data.[26] FFCC beneficiaries comprised less than 1 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries in 2023.[27] Additionally, the number of FFCC beneficiaries in each state in 2023 ranged from fewer than 70 in the District of Columbia to more than 26,000 in California. (See fig. 2 and app. II.)

Figure 2: Number of Beneficiaries Enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children Medicaid Eligibility Group in 2023

Notes: See 42 U.S.C. 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX); 42 C.F.R. 435.150 (2024). Beneficiaries were both enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) Medicaid eligibility group and were ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. FFCC beneficiaries are individuals who have aged out of foster care and meet certain criteria, regardless of their income. New York State’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials.

aWe excluded four states after we determined their T-MSIS data were not reliable for our purposes: Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, and Vermont.

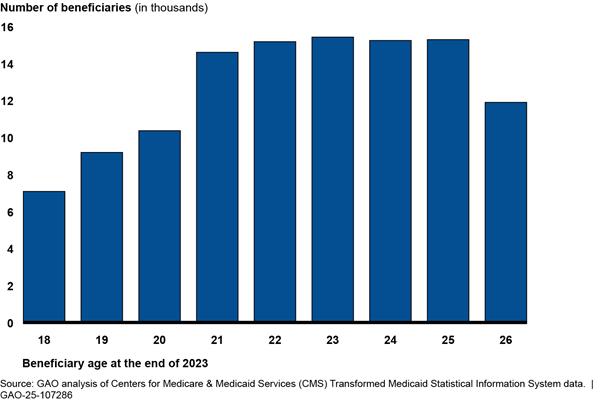

Most beneficiaries enrolled in the FFCC Medicaid eligibility group for at least one month in 2023 were ages 21 through 25, according to our analysis of T-MSIS data. Generally, individuals formerly in foster care are eligible for the FFCC group if they are ages 18 through 25. The age distribution of FFCC beneficiaries in 2023 is affected by the enrollment of individuals in extended foster care and the continuous enrollment period in effect during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Specifically:

· Extended foster care. Of the 46 states and the District of Columbia in our analysis, 34 states and the District of Columbia offered federally funded extended foster care as of June 2024. Extended foster care allows individuals to remain in foster care beyond age 18, typically through age 20, provided they meet certain requirements, such as attending school. Individuals in federally funded extended foster care are not eligible for the FFCC eligibility group until they leave extended foster care.[28] Therefore, fewer individuals ages 18 through 20 are enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group.

· Continuous enrollment period. States were required to keep beneficiaries continuously enrolled in Medicaid during the COVID-19 public health emergency, from March 2020 to March 2023, as a condition of them receiving temporary enhanced federal funding. To comply, states paused Medicaid disenrollments and had the choice to pause their Medicaid eligibility redeterminations as well. As a result, some individuals who became newly eligible for the FFCC group due to aging out of foster care between ages 18 and 21 did not have their Medicaid eligibility redetermined during that time. Instead, these individuals remained in the eligibility group for individuals in foster care rather than transitioning into the FFCC group. (See fig. 3 for beneficiaries enrolled in the FFCC group for at least one month in 2023 by age.)

Figure 3: Age Distribution of Beneficiaries Aged 18 to 26 Enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children Medicaid Eligibility Group in 2023

Notes: See 42 U.S.C. 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX); 42 C.F.R. 435.150 (2024). Beneficiaries were both enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) Medicaid eligibility group and were ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. FFCC beneficiaries are individuals who have aged out of foster care and meet certain criteria, regardless of their income. We excluded from our analysis four states for which we determined their Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System data were unreliable: Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, and Vermont. In addition, New York State’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials.

In addition, some beneficiaries who became ineligible for the FFCC group when they turned 26 years old during the continuous enrollment period did not have their eligibility group changed because their Medicaid eligibility was not redetermined. This resulted in some beneficiaries remaining enrolled in the FFCC group at age 26, and as old as age 29 in 2023.[29] Medicaid officials in all eight selected states confirmed that individuals who turned 26 during the continuous enrollment period may not have been moved from the FFCC group, which would result in individuals over age 25 remaining enrolled in 2023. Officials from the eight states said their states have taken steps to redetermine eligibility for these FFCC beneficiaries and ensure that they have been moved to the appropriate Medicaid group or disenrolled. CMS officials said that individuals formerly in foster care are likely eligible for other Medicaid eligibility groups due to the characteristics of this population that meet eligibility requirements for other groups; for example, because these individuals may have lower incomes.

In Selected States, Larger Percentages of FFCC Beneficiaries Were Black, Living in Urban Areas, or Male Compared to Their Percentages among Other Beneficiaries in Their State

Race/ Ethnicity

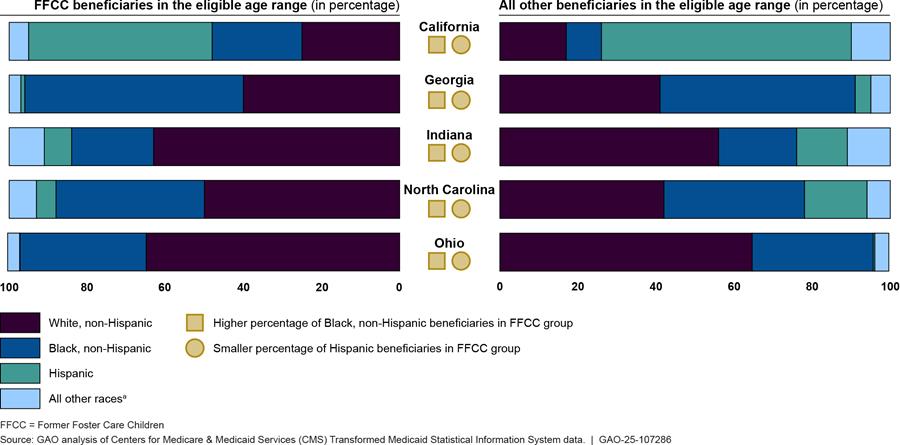

In our analysis of 2023 T-MSIS data in eight selected states, five states had reliable race and ethnicity data (California, Georgia, Indiana, North Carolina, and Ohio).[30] In all five states, we found that Black, non-Hispanic beneficiaries were a larger percentage of beneficiaries in the FFCC eligibility group than they were of similarly aged beneficiaries in all other Medicaid eligibility groups in their respective state. For example, in California, 23 percent of FFCC beneficiaries were Black, non-Hispanic, compared to 9 percent of all other similarly aged Medicaid beneficiaries in the state. Conversely, in all five states, Hispanic beneficiaries were a smaller percentage of the FFCC eligibility group than of all other Medicaid eligibility groups. In four states (California, Indiana, North Carolina, and Ohio), White, non-Hispanic beneficiaries were a larger percentage of the FFCC eligibility group than of all other Medicaid eligibility groups. (See fig. 4.)

Figure 4: Individuals Enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group and All Other Medicaid Eligibility Groups in Selected States, by Race and Ethnicity, 2023

Notes: See 42 U.S.C. 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX); 42 C.F.R. 435.150 (2024). Beneficiaries in the Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) category were both enrolled in the FFCC Medicaid group and were ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. FFCC beneficiaries are individuals who have aged out of foster care and meet certain criteria, regardless of their income. Beneficiaries enrolled in other eligibility groups were both enrolled in any other Medicaid eligibility group and were ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. Three of our eight selected states (Arizona, Massachusetts, and New York) were excluded from this analysis due to unreliable race and ethnicity data. The percentage of beneficiaries with unreliable race and ethnicity data for 2023 did not exceed 10 percent among FFCC beneficiaries or all other beneficiaries in the eligible age range for the states included in the figure. Percentages of beneficiaries are rounded to the nearest percent.

aAll other races includes American Indian and Alaska Native, non-Hispanic; Asian, non-Hispanic; Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; Multi-racial, non-Hispanic; and other, non-Hispanic. Hispanic beneficiaries may be of any race.

Three of our selected states did not have reliable race and ethnicity data (Arizona, Massachusetts, and New York).[31] In our prior work, we have documented that states have unreliable race and ethnicity data for Medicaid beneficiaries.[32] For example, our 2021 report on data completeness in Medicaid found that 21 of 50 states had acceptable race and ethnicity data for 2016.[33] We also reported that CMS asked states to focus on improving the accuracy and completeness of beneficiary eligibility data in T-MSIS, which includes beneficiaries’ race and ethnicity. In other work, we have highlighted the importance of states accurately and completely reporting on race and ethnicity to help the federal government better understand existing health disparities and take actions to promote health equity.[34] In addition, in November 2021, the CMS Administrator noted the need for accurate race and ethnicity data and a commitment to work with states to improve measurement of health disparities.[35]

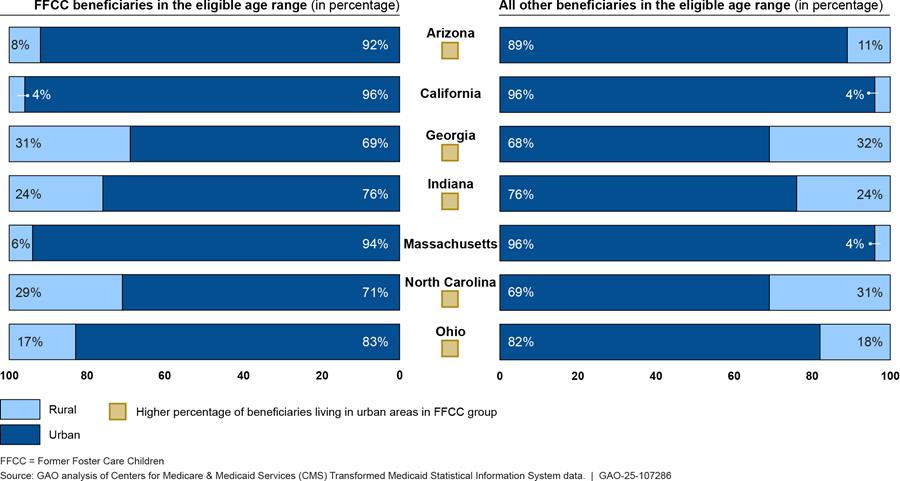

Urban/ Rural Area

In five selected states (Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, North Carolina, and Ohio), a larger percentage of beneficiaries in the FFCC eligibility group lived in urban areas, compared to similarly aged beneficiaries in all other Medicaid eligibility groups, according to our analysis of seven selected states’ reliable 2023 T-MSIS data.[36] Medicaid officials in one selected state said that some smaller, rural counties may have less experience and expertise in enrolling individuals formerly in foster care in Medicaid. Individuals formerly in foster care we interviewed in Georgia said that information about Medicaid coverage is not always shared with those living in rural areas, so individuals eligible for the FFCC eligibility group may not be aware of the benefits available to them. (See fig. 5.)

Figure 5: Individuals Enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group and All Other Medicaid Eligibility Groups in Selected States, by Rurality, 2023

Notes: See 42 U.S.C. 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX); 42 C.F.R. 435.150 (2024). Beneficiaries in the Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) category were both enrolled in the FFCC Medicaid group and were ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. FFCC beneficiaries are individuals who have aged out of foster care and meet certain criteria, regardless of their income. Beneficiaries enrolled in other eligibility groups were both enrolled in any other Medicaid eligibility group and were ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. One of our eight selected states (New York) was excluded from this analysis because the state’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials. Percentages of beneficiaries are rounded to the nearest percent. Indiana had a smaller percentage of beneficiaries living in urban areas in the FFCC eligibility group than other Medicaid beneficiaries, but the percentages are equal due to rounding.

Gender

In five selected states (Arizona, California, Georgia, Indiana, and Ohio), males were a larger percentage of beneficiaries in the FFCC eligibility group than they were of similarly aged beneficiaries in all other Medicaid eligibility groups in their state, according to our analysis of seven states.[37] (See fig. 6.)

Figure 6: Individuals Enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group and All Other Medicaid Eligibility Groups in Selected States, by Gender, 2023

Notes: See 42 U.S.C. 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX); 42 C.F.R. 435.150 (2024). Beneficiaries in the Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) category were both enrolled in the FFCC Medicaid group and were age 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. FFCC beneficiaries are individuals who have aged out of foster care and meet certain criteria, regardless of their income. Beneficiaries enrolled in other eligibility groups were both enrolled in any other Medicaid eligibility group and were age 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. T-MSIS data include the following genders for a beneficiary’s biological or self-identified sex: male and female. One of our eight selected states (New York) was excluded from this analysis because the state’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials. Percentages of beneficiaries are rounded to the nearest percent.

Enrollment Barriers Included Renewal Difficulties, Frequent Moving; Selected States’ Efforts to Address Them Included Simplifying Renewals and Conducting Outreach

Individuals can experience various barriers to enrolling in and maintaining Medicaid coverage upon aging out of foster care, according to officials from CMS and selected states’ Medicaid and child welfare agencies. These barriers include

· difficulties experienced during the Medicaid enrollment and renewal process,

· frequent address changes due to transient and unstable housing,

· less specialized knowledge among agency staff,

· difficulty coordinating between state agencies, and

· mistrust of the child welfare system by individuals formerly in foster care.

Some of these barriers are not unique to individuals formerly in foster care and may be experienced by other individuals seeking or maintaining Medicaid coverage. However, individuals formerly in foster care are more likely to experience these barriers, according to officials from our selected states. Representatives from selected organizations that work with individuals formerly in foster care told us that this includes certain populations of individuals—such as Black youth, youth residing in rural areas, and youth who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning—some of whom are overrepresented in foster care. Lack of access to health coverage and services, in turn, can exacerbate disparities in health and social outcomes for individuals formerly in foster care, according to CMS.[38]

To address these barriers to enrolling in and maintaining Medicaid coverage, selected states use a variety of approaches, such as providing information through outreach events for individuals currently or formerly in foster care and simplifying Medicaid renewal processes, according to officials and documents from CMS and selected states. Some of these approaches were possible due to CMS efforts to facilitate continuity of Medicaid coverage for various populations, including individuals formerly in foster care. However, officials from our selected states noted that these approaches were particularly relevant to individuals formerly in foster care. (See table 1.)

Table 1: Examples of Barriers Individuals Formerly in Foster Care May Experience Enrolling in and Maintaining Medicaid Coverage, and Selected States’ Approaches to Address Them

|

Barriers individuals formerly in foster care may experience |

Examples of approaches selected states took to address barriers |

|

Difficulties enrolling in and renewing Medicaid: · Individuals may not have health literacy or a supportive adult to assist with managing their health care and coverage options. · Individuals may not have access to documents needed to apply for Medicaid, such as proof of former foster care status. · Individuals may lack access to certain technology, such as a phone or the internet, to access the state’s Medicaid application modalities or respond to renewal requests. |

Conducted outreach about Medicaid: · State Medicaid and child welfare agencies partnered with organizations that serve individuals currently and formerly in foster care to share Medicaid information. · State Medicaid and child welfare agencies participated in conferences and other events targeted at individuals currently or formerly in foster care to share Medicaid information. Used specialized caseworkers: · State child welfare agencies used caseworkers that work specifically with older individuals currently or formerly in foster care to help them understand their Medicaid eligibility and apply. Simplified enrollment and renewal process: · State Medicaid agencies accepted attestation of former foster care status and prior Medicaid enrollment, so that individuals did not need to provide documents. · State Medicaid agencies requested waivers of certain requirements to streamline the enrollment process for individuals formerly in foster care. |

|

Transient population and unstable housing: · Individuals may not have a permanent address due to housing instability or homelessness. · State Medicaid agencies may not have an accurate address to send requests for information during the annual renewal process for maintaining enrollment, so individuals may not respond to these requests. |

Used alternative information sources to confirm state residency: · State Medicaid agencies used flexibilities allowed during the public health emergency to access other reliable information sources, like the National Change of Address database or managed care organizations, to verify or update an individual’s address without having to contact them.a Enrolled individuals in certain Medicaid delivery options: · State Medicaid agencies enrolled individuals into a Medicaid delivery system with statewide coverage, instead of plans with regional coverage, to accommodate frequent housing changes within this group. Used technology to contact individuals: · State Medicaid agencies used technology, such as text messaging, to reach individuals who move frequently or do not have a mailing address. |

|

Less specialized knowledge among state agency staff: · Medicaid and child welfare agency staff may lack specialized knowledge about Medicaid eligibility for this group, in part, because of high rates of staff turnover in some states. |

Used specialized eligibility staff: · State Medicaid agencies designated specific staff to manage enrollment for individuals currently and formerly in foster care so they have specialized knowledge of eligibility rules for the Former Foster Care Children group. · A state child welfare agency designated specific caseworkers to manage Medicaid outreach and enrollment so that individuals formerly in foster care interact with staff who have specialized knowledge of Medicaid. |

|

Difficulty coordinating between state agencies: · Coordination may be difficult between the Medicaid and child welfare agencies because they use separate record systems. |

Collaborated across state agencies: · State Medicaid agency staff provided training to child welfare agency caseworkers on rules for the Former Foster Care Children eligibility group to improve staff knowledge. · State child welfare agencies sent a list of individuals aging out of foster care to the Medicaid agency each month to ensure timely redetermination of individuals’ Medicaid coverage. |

|

Mistrust of child welfare system: · Individuals formerly in foster care may not trust the child welfare system, which hinders them from seeking assistance from the child welfare agency or the state government in general. |

Used external staff and trusted contacts: · States contracted with external organizations to provide case management services and other supports to older individuals in foster care or who recently aged out, such as helping them apply for Medicaid, so that they had access to individuals outside the child welfare agency. · State child welfare agencies leveraged Youth Advisory Boards that serve individuals currently and formerly in foster care to share information about Medicaid, because individuals formerly in foster care often prefer to receive information from peers who have experienced foster care or organizations that have supported them. · A state child welfare agency developed a youth navigator program where foster youth and former foster youth could reach out by phone or text to get help with issues related to Medicaid enrollment. |

Source: GAO analysis of interviews with officials from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Administration for Children and Families, selected state Medicaid and child welfare agencies, and selected advocacy organizations; and CMS documents. | GAO‑25‑107286

Note: Selected states are Arizona, California, Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, and Ohio.

aStates used flexibilities that CMS provided in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency under section 1902(e)(14)(A) of the Social Security Act to facilitate ex parte renewals. Since then, additional regulatory changes have made some of these flexibilities permanent.

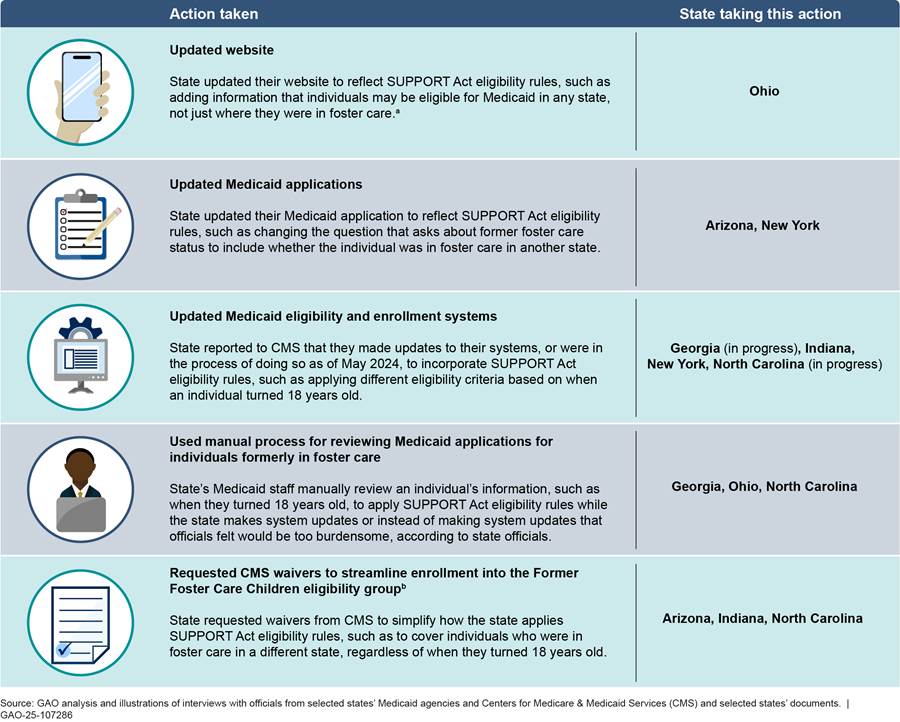

Selected States Updated Medicaid Applications and Used CMS Waivers, among other Actions, to Implement SUPPORT Act Changes

Among our eight selected states, six have made changes to implement the SUPPORT Act changes, such as updating their Medicaid applications or enrollment systems, or requesting CMS waivers to simplify the enrollment process, according to documents from and interviews with CMS and state Medicaid officials.[39] (See fig. 7.) Officials from the two other selected states—California and Massachusetts—told us they did not make changes to their processes or systems because they had received CMS waivers prior to the SUPPORT Act to cover individuals who aged out of foster care in another state.

Figure 7: Examples of Actions Selected State Medicaid Agencies Reported Taking to Implement SUPPORT Act Eligibility Changes for the Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group

Notes: Selected states are Arizona, California, Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, and Ohio. California and Massachusetts are excluded from this figure because they already had CMS approval to enroll individuals who aged out of foster care in another state prior to the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act). See Pub. L. No. 115-271, 1002, 132 Stat. 3894, 3902. This act requires that states apply separate criteria when determining eligibility for the Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) eligibility group, depending on when an individual turned age 18. Specifically, states are only required to provide Medicaid eligibility through the FFCC group to individuals who turned 18 prior to January 1, 2023, if the individual aged out of foster care in the same state. In addition, states may not enroll those individuals in the FFCC group if they are eligible for certain other eligibility groups. However, for individuals who turn 18 on or after January 1, 2023, states must extend coverage to eligible individuals regardless of the state in which they aged out of foster care and whether they are eligible for most other mandatory groups.

aMedicaid officials in five states said they do not conduct direct outreach to individuals who were in foster care in another state, and officials in four states said they cannot identify these individuals unless they apply for Medicaid and indicate they were formerly in foster care.

bUnder the Social Security Act, states may request waivers from CMS to streamline Medicaid enrollment. These waivers may include (1) section 1115 demonstrations to waive the requirement to apply separate eligibility rules for individuals formerly in foster care based on when the individual turned age 18, and (2) section 1902(e)(14)(A) waivers to temporarily waive this requirement until the state comes into full compliance with requirements or receives approval for a section 1115 waiver.

CMS Oversight of Former Foster Care Children Eligibility Group Included Providing Enrollment Guidance to States and Monitoring Eligibility

CMS has provided guidance and technical assistance to states on the FFCC eligibility group and monitors enrollment of the FFCC eligibility group as part of its overall oversight of all Medicaid eligibility groups. Federal internal control standards state that federal agencies should periodically review their policies and procedures for continued relevance, and identify, analyze, and respond to risks. [40] Examples of CMS oversight involving such policies and procedures include the following:

· CMS issued guidance to states regarding the FFCC eligibility group that included strategies to reach and enroll individuals in this group, and explanations of the SUPPORT Act changes to the eligibility requirements.[41] CMS also provided technical assistance to states on submitting required state plan amendments to implement the SUPPORT Act changes to the FFCC eligibility group.[42] Specifically, CMS reviewed the state plan amendments and worked with states to determine how they would update eligibility and enrollment systems, and conduct outreach to individuals formerly in foster care.

· CMS monitors the accuracy of states’ Medicaid eligibility determinations for all eligibility groups, including the FFCC eligibility group, through the Payment Error Rate Measurement and the Medicaid Eligibility Quality Control programs, according to agency officials. In addition, CMS has been working closely with states following the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency to identify noncompliance with eligibility redetermination requirements.[43] CMS officials said they have not identified any compliance issues specific to the FFCC eligibility group through these efforts as of November 2024.

· CMS will reach out to a state for further discussion if the agency is notified by a stakeholder of a Medicaid compliance issue, according to agency officials. Officials said they expect that states are complying with Medicaid eligibility and enrollment requirements unless the agency becomes aware of an issue. As of November 2024, CMS officials said they were not aware of any compliance issues related to the FFCC eligibility group.

According to agency officials, CMS assessed the risk of not conducting additional eligibility and enrollment monitoring for the FFCC eligibility group to both beneficiaries and the Medicaid program and determined it was low. For example, officials said the Medicaid benefits a beneficiary receives and the federal matching rate are the same whether a beneficiary is enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group or another mandatory group, other than for the adult group.[44] As previously noted, CMS officials have said that individuals formerly in foster care are likely eligible for other Medicaid eligibility groups due to the characteristics of this population.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Health and Human Services for review and comment. The Department of Health and Human Services provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-7114 or FarbJ@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Sincerely,

Jessica Farb

Managing Director, Health Care

Appendix I: Scope and Methodology for the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System Data Analysis

To describe the size and demographic characteristics of Medicaid’s Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) eligibility group, we analyzed data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS).[45] We accessed T-MSIS data on November 5 and 7, 2024, for calendar year 2023, the most recent year of complete data.[46] In 46 states and the District of Columbia, we analyzed T-MSIS data for beneficiary Medicaid eligibility group and age. Specifically, we calculated the number of (1) beneficiaries both enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group and ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023; and (2) beneficiaries enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group at each age from 18 through 26 using the beneficiary’s age as of December 31, 2023.[47]

In eight selected states, we conducted additional T-MSIS analysis on beneficiaries’ demographic characteristics. We selected these states—Arizona, California, Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, and Ohio—for variation in the number of individuals in foster care, geographic location, and whether the state had requested and received permission from CMS to enroll individuals into the FFCC eligibility group who had aged out of foster care in another state prior to the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act (SUPPORT Act). In these states, we identified and organized demographic characteristics for beneficiaries both enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group and ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023 as follows:

· Race/ ethnicity. T-MSIS data include the following values for race and ethnicity that we used for our analysis: American Indian and Alaska Native, non-Hispanic; Asian, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; Hispanic, all races; Multi-racial, non-Hispanic; White, non-Hispanic; other, non-Hispanic; and null, which may occur, for example, if the beneficiary’s race and ethnicity was not reported.

· Gender. Beneficiary’s biological sex or their self-identified sex. T-MSIS data include the following values for gender: male and female.

· Urban/ rural area. To determine whether beneficiaries lived in an urban or rural area, we identified the number of unique beneficiaries living in each geographic area (zip code or county), as reported in T-MSIS, and used the CMS Zip Code Geographic Reference file to define urban and rural areas. In limited circumstances, beneficiaries may be counted more than once within a state.[48]

We then calculated race/ ethnicity, gender, and urban/ rural area for beneficiaries in other Medicaid eligibility groups who were aged 18 to 25 for at least one month in 2023 in the selected states and compared the results to the same demographic information for FFCC beneficiaries.

We did not independently verify the accuracy of the T-MSIS data; however, we took steps to assess the reliability of the data. We assessed the reliability of T-MSIS data by reviewing documentation, such as technical documentation from CMS describing the data and CMS’s assessment of its quality, checking the T-MSIS data for obvious errors and omissions, and interviewing CMS and state officials to resolve any identified discrepancies. On the basis of our review of the T-MSIS data, we determined the following:

· Beneficiary Medicaid eligibility group and age were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report for 46 states and the District of Columbia, and we accounted for any limitation or discrepancy in these data during our analyses. We determined that the T-MSIS data from Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, and Vermont were not sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our reporting and excluded each state’s data from our analysis. In Idaho, Iowa, and Kentucky, we identified reliability issues with age data for beneficiaries enrolled in the FFCC eligibility group. In Vermont, CMS had high levels of concern with the beneficiary eligibility group data. Additionally, while we determined New York State’s data for FFCC beneficiaries to be reliable for purposes of inclusion in our beneficiary Medicaid eligibility group and age analysis, the state’s data do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials. State officials said New York City uses a different data category for FFCC beneficiaries than the rest of the state. State officials said they were working to address this issue.

· Beneficiary demographic information on race/ ethnicity, gender, and urban/ rural area were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report for seven of our eight selected states, and we accounted for any limitation or discrepancy in these data during our analyses. Specifically, we excluded New York State from our analysis of race/ ethnicity, gender, and residence in an urban or rural area because, as previously noted, New York State’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City. We also excluded Arizona and Massachusetts from the race/ ethnicity analysis because they did not have reliable race and ethnicity data for at least 90 percent of FFCC beneficiaries.

Appendix II: Number of Beneficiaries Enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children Medicaid Eligibility Group in 2023, by State

Table 2 provides information on the number of Medicaid beneficiaries aged 18 through 25 enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children eligibility group for at least one month in 2023, by state, based on our analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System data.

Table 2: Beneficiaries Enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) Medicaid Eligibility Group in 2023

|

State |

Number of individuals enrolled |

|

Alabama |

971 |

|

Alaska |

188 |

|

Arizona |

7,316 |

|

Arkansas |

455 |

|

California |

26,544 |

|

Colorado |

1,621 |

|

Connecticut |

628 |

|

Delaware |

343 |

|

District of Columbia |

66 |

|

Florida |

2,808 |

|

Georgia |

2,432 |

|

Hawaii |

640 |

|

Idaho |

N/Aa |

|

Illinois |

1,721 |

|

Indiana |

2,952 |

|

Iowa |

N/Aa |

|

Kansas |

2,123 |

|

Kentucky |

N/Aa |

|

Louisiana |

1,261 |

|

Maine |

231 |

|

Maryland |

897 |

|

Massachusetts |

2,730 |

|

Michigan |

14,134 |

|

Minnesota |

1,068 |

|

Mississippi |

1,063 |

|

Missouri |

2,550 |

|

Montana |

348 |

|

Nebraska |

669 |

|

Nevada |

787 |

|

New Hampshire |

441 |

|

New Jersey |

1,259 |

|

New Mexico |

223 |

|

New Yorkb |

1,366 |

|

North Carolina |

1,811 |

|

North Dakota |

466 |

|

Ohio |

1,943 |

|

Oklahoma |

1,056 |

|

Oregon |

1,227 |

|

Pennsylvania |

3,827 |

|

Rhode Island |

513 |

|

South Carolina |

811 |

|

South Dakota |

446 |

|

Tennessee |

5,132 |

|

Texas |

7,003 |

|

Utah |

923 |

|

Vermont |

N/Aa |

|

Virginia |

2,637 |

|

Washington |

3,210 |

|

West Virginia |

161 |

|

Wisconsin |

1,038 |

|

Wyoming |

284 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System data. | GAO‑25‑107286

Notes: See 42 U.S.C. 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX); 42 C.F.R. 435.150 (2024). Beneficiaries were both enrolled in the Former Foster Care Children (FFCC) Medicaid eligibility group and ages 18 through 25 for at least one month in 2023. FFCC beneficiaries are individuals who have aged out of foster care and meet certain criteria, regardless of their income.

aWe excluded four states with unreliable Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System data from our analyses: Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, and Vermont.

bNew York State’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials.

GAO Contact

Jessica Farb, (202) 512-7114 or FarbJ@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Peter Mangano (Assistant Director), Erika Huber (Analyst-in-Charge), Mallory Kennedy, Catina B. Latham, Jodi Lewis, and Shana Sandberg made key contributions to this report. Also contributing were Julianne Flowers, Drew Long, Jennifer Rudisill, and Roxanna Sun.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]Approximately 370,000 individuals were in foster care as of September 30, 2022. See Administration for Children and Families, Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System Report # 30 (Mar. 13, 2024). In general, individuals age out of foster care when they turn 18 years old; however, 35 states and the District of Columbia allow individuals to remain in foster care voluntarily through age 20, provided they meet certain criteria, such as attending school.

[2]For example, see Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS All-State SOTA Call: Ensuring Access to Medicaid Coverage for Former Foster Care Youth (June 1, 2017).

[3]CMS and the Administration for Children and Families are agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services.

[4]Several states provide child welfare and Medicaid services under county- rather than state-administered agencies.

[5]Pub. L. No. 111-148, §§ 2004(a), 10201(a), 124 Stat. 119, 283, 917 (2010) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX)).

[6]Pub. L. No. 115-271, § 1002, 132 Stat. 3894, 3902 (2018). The SUPPORT Act also simplified Medicaid eligibility determinations and enrollment processes for this population.

[7]T-MSIS is an initiative to improve state-reported data available for overseeing Medicaid.

[8]We excluded four states after determining their T-MSIS data were not reliable for purposes of our reporting objectives: Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, and Vermont.

[9]See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014). Internal control is a process effected by an entity’s oversight body, management, and other personnel that provides reasonable assurance that the objectives of an entity will be achieved. Applicable underlying principles for internal control activities and risk assessments are that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks, as well as review policies for continued relevance and effectiveness in achieving the entity’s objectives.

[10]Section 1905(a) of the Social Security Act lists 17 categories of individuals, also known as populations, who may receive Medicaid coverage if they meet applicable criteria. See 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(a). Most eligibility groups are defined in sections 1902(a)(10)(A)(i) (mandatory groups) and 1902(a)(10)(A)(ii) (optional groups) of the Social Security Act. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i), (ii).

[11]In verifying individuals’ eligibility, states must assess specified financial and nonfinancial information.

[12]Individuals may meet the criteria for more than one category and eligibility group. For example, an individual who is under age 18 and pregnant could meet the criteria applicable to children and those applicable to pregnant women. However, a state would enroll this individual under one basis of eligibility only, unless an exception applies.

[13]For additional information on CMS oversight of Medicaid eligibility determinations, including these programs, see GAO, Medicaid Eligibility: Accuracy of Determinations and Efforts to Recoup Federal Funds Due to Errors, GAO‑20‑157 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 13, 2020).

[14]Exceptions include individuals who exit foster care before age 18 or were not enrolled in Medicaid while in foster care. These individuals formerly in foster care are not eligible for Medicaid under the FFCC eligibility group.

[15]For purposes of this report, we refer to these statutory amendments to FFCC eligibility criteria as the “SUPPORT Act changes.” The SUPPORT Act did not change the statutory requirement for individuals eligible for both the FFCC group and the adult group (described in section 1902(a)(10)(A)(i)(VIII) of the Social Security Act) to be enrolled in the FFCC group.

[16]Accordingly, the SUPPORT Act did not change eligibility requirements for former foster youth who turned 18 years old before January 1, 2023. Those individuals remain subject to the statutory eligibility criteria established in 2014 under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. For example, individuals who turned age 18 prior to January 1, 2023, are not eligible for the FFCC eligibility group if they are eligible for another mandatory group, other than the adult group. In addition, they are eligible for Medicaid under the FFCC group only in the state in which they aged out of foster care, unless the state received a waiver of this requirement.

[17]Under section 1115 of the Social Security Act, the Secretary of Health and Human Services may waive certain federal Medicaid requirements that, in the Secretary’s judgment, are likely to promote Medicaid objectives. See 42 U.S.C. § 1315.

From January 1, 2014, through January 20, 2017, 14 states covered individuals who aged out of foster care in another state through their state plan. A Medicaid state plan is an agreement between a state and the federal government describing how that state administers its Medicaid program, including giving assurance that a state will abide by federal rules. When a state is planning to make a change to its program, it sends a state plan amendment to CMS for review and approval. As of January 21, 2017, states were required to have an approved CMS demonstration to continue covering these individuals.

[18]According to CMS, 11 states had a section 1115 demonstration to cover individuals who aged out of foster care in another state prior to the SUPPORT Act. CMS officials said, as of September 2024, these states are approved to continue covering individuals who aged out of foster care in another state and turned age 18 prior to January 1, 2023.

[19]See 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(e)(14)(A).

[20]CMS has issued guidance recommending that state Medicaid and child welfare agencies collaborate to enroll individuals in the FFCC eligibility group automatically when they age out of foster care.

[21]States are required to take steps to ensure continuity of coverage for Medicaid beneficiaries, such as determining eligibility for all possible groups prior to terminating coverage. According to CMS officials, this helps ensure an individual aging out of foster care continues to be enrolled. Individuals formerly in foster care may be eligible for other Medicaid eligibility groups, such as those for individuals under age 19, parents or caretakers, or pregnant people.

Officials in five selected states said that Medicaid eligibility is processed by another department or a county agency that also determines individuals’ eligibility for other programs, such as food assistance.

[22]42 C.F.R. §§ 435.916(a)(1), 435.919(b) (2024).

[23]42 C.F.R. § 435.916(b) (2024).

[24]For example, see Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, SHO #22-001 RE: Promoting Continuity of Coverage and Distributing Eligibility and Enrollment Workload in Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Basic Health Program (BHP) Upon Conclusion of the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (Baltimore, Md.: Dec. 16, 2022); and CMCS Informational Bulletin: Conducting Medicaid and CHIP Renewals During the Unwinding Period and Beyond: Essential Reminders. (Baltimore, Md.: Mar. 15, 2024).

[25]42 C.F.R. § 435.916(d) (2024). States must also follow procedures to notify the individual and transfer the individual’s account to a coverage program for which they are potentially eligible. See 42 C.F.R. § 435.1200(e) (2024).

[26]We excluded four states after we determined their T-MSIS data were not reliable for purposes of our analyses: Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, and Vermont. New York State’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials. State officials said New York City uses a different data category for FFCC beneficiaries than the rest of the state. State officials said they were working to address this issue.

The count of FFCC beneficiaries in 2023 does not represent the total number of individuals formerly in foster care who were enrolled in Medicaid. Individuals formerly in foster care are typically eligible for the FFCC eligibility group. Some of these individuals may be enrolled in other Medicaid eligibility groups, such as the Medicaid eligibility group for pregnant people. In addition, under current law, states must enroll certain former foster youth—those who turned age 18 before January 1, 2023—into other mandatory eligibility groups for which they are eligible rather than enrolling them in the FFCC eligibility group. CMS officials said that over time, the FFCC eligibility group will include a greater proportion of individuals formerly in foster care, as more individuals turn age 18 after January 1, 2023, and those who turned 18 prior to this date will age out (i.e., turn age 26).

[27]Monthly totals of Medicaid beneficiaries in 2023 ranged from 77.9 million to 86.9 million.

[28]See 42 C.F.R. § 435.145 (2024).

[29]According to our T-MSIS analysis, there were about 17,000 individuals ages 26 through 29 enrolled in the FFCC group in 2023.

[30]The eight selected states are Arizona, California, Georgia, Indiana, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, and Ohio.

[31]Arizona and Massachusetts did not have reliable race and ethnicity data for at least 90 percent of FFCC beneficiaries. New York State’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials. State officials said New York City uses a different data category for FFCC beneficiaries than the rest of the state. State officials said they were working to address this issue.

[32]We have recommended CMS continue efforts to assess and improve T-MSIS data and articulate specific plans and associated time frames for using these data for broad program oversight. See GAO, High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023). As of December 2024, CMS has addressed some of these recommendations, but has not addressed others.

[33]See GAO, Medicaid: Data Completeness and Accuracy Have Improved, Though Not All Standards Have Been Met, GAO‑21‑196 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 14, 2021).

[34]See GAO, Medicaid: CMS Should Assess Effect of Increased Telehealth Use on Beneficiaries’ Quality of Care, GAO‑22‑104700 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 31, 2022); and Medicaid: Characteristics of and Expenditures for Adults with Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities, GAO‑23‑105457 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 24, 2023).

[35]See Chiquita Brooks-LaSure and Daniel Tsai, “A Strategic Vision for Medicaid and The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP),” Health Affairs Blog (Nov. 16, 2021), DOI: 10.1377/hblog20211115.537685.

[36]One of our eight selected states (New York) was excluded from this analysis because the state’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials.

[37]T-MSIS data include the following genders for a beneficiary’s biological or self-identified sex: male and female. Beginning in 2025, states will be able to report beneficiaries’ sexual orientation and gender identity in T-MSIS. Studies suggest that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning youth are over-represented in foster care.

One of our eight selected states (New York) was excluded from this analysis because the state’s data for FFCC beneficiaries do not include data from New York City, according to New York State Medicaid officials.

[38]See Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, SHO #22-003 RE: Coverage of Youth Formerly in Foster Care in Medicaid (Section 1002(a) of the SUPPORT Act) (Baltimore, Md.: Dec. 16, 2022).

[39]As previously described, the SUPPORT Act introduced changes to the Medicaid FFCC eligibility group for individuals formerly in foster care who turned age 18 on or after January 1, 2023, including requiring states to cover individuals who aged out of foster care in another state. Pub. L. No. 115-271, § 1002, 132 Stat. 3894, 3902 (2018).

[40]See GAO‑14‑704G.

[41]For example, see Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, SHO #22-003 RE: Coverage of Youth Formerly in Foster Care in Medicaid (Section 1002(a) of the SUPPORT Act) (Baltimore, Md.: Dec. 16, 2022).

[42]States were required to submit state plan amendments by March 31, 2023, in order to be effective January 1, 2023. As of July 2024, all states submitted timely state plan amendments, except for one state. CMS officials told us that state took steps to ensure individuals had coverage until the state plan amendment went into effect.

As of October 2024, CMS regulations are not consistent with statutory FFCC eligibility requirements as amended by the SUPPORT Act. See 42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(IX) and 42 C.F.R. § 435.150 (2024). In September 2024, CMS officials said its guidance and technical assistance on implementing the SUPPORT Act gave it assurance states were aware of and following the requirements. CMS officials also said they would consider updating the regulation in future rulemaking.

[43]In July 2024, we reported on CMS’s oversight of Medicaid eligibility redeterminations following the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency. Specifically, we reported that CMS identified a number of common areas of states’ noncompliance with eligibility determination requirements, such as states not conducting ex parte renewals for certain eligibility groups, which led to eligible individuals losing Medicaid coverage in some cases. CMS officials told us they identified key lessons learned regarding the agency’s oversight, such as the need for ongoing guidance. We recommended that CMS document and implement changes to its oversight of states’ Medicaid eligibility redeterminations that reflect lessons learned. CMS agreed with the recommendation. As of September 2024, CMS had not yet addressed the recommendation. See GAO, Medicaid: Federal Oversight of State Eligibility Redeterminations Should Reflect Lessons Learned after COVID-19, GAO‑24‑106883 (Washington, D.C.: July 18, 2024).

[44]CMS and states share responsibility for financing Medicaid expenditures. CMS matches states’ expenditures for a portion (i.e., the federal share or the federal financial participation) of each state’s Medicaid program costs. The amount CMS pays states varies by state, as well as for certain types of expenditures (e.g., services or administrative costs) and populations (e.g., the adult group).

[45]T-MSIS is an initiative to improve state-reported data available for overseeing Medicaid.

[46]Specifically, we reviewed data from CMS’s T-MSIS Analytic Files, a series of research-ready analytic files CMS created to support analysis, research, and data-driven decisions on key Medicaid topics, as well as program oversight. All Medicaid beneficiary data we reviewed were from the Annual Demographic and Eligibility T-MSIS Analytic Files. For the purposes of our report, we refer to the T-MSIS Analytic Files as T-MSIS data.

T-MSIS data may change over time as states make updates and corrections to their data.

[47]While the eligible age range for the FFCC eligibility group is 18 through 25, we included individuals who were 25 for at least one month in 2023 and were 26 as of December 31, 2023, because these individuals would have been eligible for the FFCC eligibility group for part of the year.

[48]Duplicate counting of beneficiaries occurred when a beneficiary’s T-MSIS data indicated that the beneficiary lived in both an urban area and a rural area of the state. Less than 2 percent of beneficiaries are counted more than once in each of our selected states.