FEDERAL CIVILIAN FIREFIGHTERS

DOD Should Take Action to Address Long-Standing Staffing Gaps

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact

Kristy E. Williams at williamsk@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107288, a report to congressional requesters

Federal Civilian firefighters

DOD Should Take Action to Address Long-Standing Staffing Gaps

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD’s Fire and Emergency Services community supports efforts to safeguard and advance vital U.S. national interests by ensuring safety and minimizing loss on DOD installations. DOD civilian firefighters comprise 95 percent of all federal civilian firefighters who provide structural firefighting services, such as responding to building fires. According to DOD, meeting firefighter staffing requirements is important to maintain safe operations.

GAO was asked to review issues facing federal agencies with civilian firefighter workforces. This report (1) compares DOD civilian firefighter authorizations with staffing levels, (2) assesses DOD’s efforts to address civilian firefighter staffing gaps, and (3) compares DOD and local government firefighter work schedules and compensation at five locations.

GAO reviewed relevant regulations and policies; analyzed DOD and OPM data on staffing, compensation, and hours worked; and interviewed cognizant DOD and OPM officials. GAO interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of firefighters and officials at five DOD installations, selected to obtain variation among the services.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations that DOD implement a strategy to mitigate firefighter staffing gaps and monitor efforts to set annual staffing targets and close gaps, and the military services develop strategic human capital plans that include all required elements. DOD generally concurred with the recommendations and identified actions it plans to take to implement them.

What GAO Found

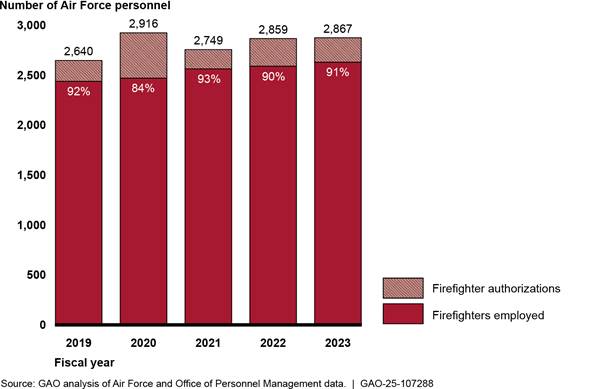

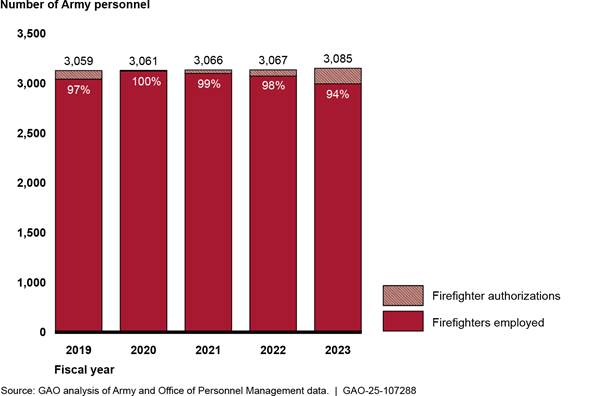

The Department of Defense (DOD) employed fewer civilian firefighters than authorized in fiscal years 2019 through 2023, the most current 5 years of data available. According to DOD and Office of Personnel Management (OPM) data, DOD employed approximately 93 percent of its authorized civilian firefighter positions in fiscal years 2019 through 2023. DOD stated that the authorizations represent the minimum staffing that must be maintained to ensure safe operations and that staffing below the authorized levels increases the department’s risk of property loss and environmental damage.

DOD has taken limited steps to address long-standing staffing gaps in its civilian firefighter workforce. Since 2003 DOD has identified causes of civilian firefighter staffing gaps (see figure), such as competition from local fire departments. DOD has taken some steps, such as including strategies for civilian firefighter retention in the department’s strategic workforce plan updates, to address these gaps.

However, DOD has not fully addressed the identified causes of its civilian firefighter staffing gaps through sustained or coordinated efforts. Specifically:

· DOD has not developed and implemented a department-wide strategy to mitigate the causes of and close civilian firefighter staffing gaps. Such a strategy is required by DOD policy and federal regulations. Developing this would better position DOD to address long-standing civilian firefighter staffing gaps that put firefighters at increased risk of injury.

· DOD has not consistently set staffing targets for its civilian firefighter workforce or reported on progress in closing identified gaps. Monitoring such efforts will provide DOD leadership better visibility over progress in closing the identified staffing gaps that have the potential to put a strategic program or goal at risk of failure.

· The military services have not consistently developed or implemented Fire and Emergency Services civilian strategic human capital plans. Such plans, as required by DOD policy, would assess the current state of the workforce and forecast future requirements to manage risks.

GAO also found that DOD civilian firefighters at all five selected locations worked more hours than local firefighters and made less per hour in base compensation, while total cash compensation varied. Including an analysis of DOD and local fire departments’ work hours and compensation differences within its department-wide strategy would help DOD make progress toward addressing staffing gaps.

Abbreviations

|

DCPAS |

Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service |

|

DLA |

Defense Logistics Agency |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FLSA |

Fair Labor Standards Act |

|

GS |

General Schedule |

|

MCO |

mission-critical occupation |

|

OPM |

Office of Personnel Management |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 30, 2025

The Honorable Gerald E. Connolly

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Honorable Kweisi Mfume

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Government Operations and the Federal Workforce

Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

House of Representatives

The Department of Defense’s (DOD) Fire and Emergency Services community supports efforts to safeguard and advance vital U.S. national interests by ensuring safety and minimizing loss on DOD installations.[1] This community ensures the continued function and resilience of the department’s personnel, facilities, and infrastructure, among other things, and serves as the first line of defense when catastrophes threaten DOD installations. Within the Fire and Emergency Services community, DOD structural civilian firefighters—hereafter referred to as DOD civilian firefighters—provide structural firefighting services, such as responding to building fires. Other functions include aircraft rescue and firefighting, wildland firefighting, and all-hazards incidents.[2] DOD’s civilian firefighters are a subset of the larger federal firefighting workforce.[3] In fiscal year 2024, DOD employed about 95 percent (approximately 8,800) of all federal structural civilian firefighters.[4]

DOD determines its civilian firefighter authorizations—or the total number of civilian firefighters the department is allowed in a fiscal year—based on DOD and National Fire Protection Association standards and service-level objectives. According to DOD, the number of civilian firefighters authorized each year represents the minimum staffing requirement that must be maintained to ensure safe operations.[5] More specifically, in its Fiscal Year 2010–2018 Strategic Workforce Plan, DOD stated that staffing below the authorized levels increases DOD’s risk of property loss and environmental damage.[6] Since 2010, DOD has consistently identified fire protection (i.e., civilian firefighters) as a mission-critical occupation (MCO), or one that has the potential to put a strategic program or goal at risk of failure related to human capital deficiencies.

You asked us to review issues facing federal agencies with structural firefighting responsibilities, including recruitment and retention barriers and how federal firefighters’ compensation and work schedules compare with their local and state counterparts. This report (1) compares DOD civilian firefighter staffing levels with authorized positions, (2) assesses the extent to which DOD has addressed civilian firefighter staffing gaps, and (3) compares DOD civilian firefighter hours worked and compensation with local government firefighter hours worked and compensation at selected locations.

We focused our review on civilian firefighters employed by DOD because the department employs approximately 95 percent of the federal structural civilian firefighter workforce. For all three objectives we conducted a mix of in-person and virtual site visits at a nongeneralizable sample of five DOD locations.[7] During these site visits, we interviewed 10 groups of firefighters, five installation fire chiefs, and five groups of installation human resources managers about efforts to recruit and retain DOD civilian firefighters and any issues facing the DOD civilian firefighter workforce. At each of the five selected DOD locations, we also identified a corresponding local fire department, from which we obtained data on local firefighter compensation and hours worked.

For our first objective, we obtained DOD civilian firefighter authorization data from the military services and the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA).[8] We obtained DOD civilian firefighter staffing level data for fiscal years 2019 through 2023 from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). We analyzed the data to identify any differences between the number of civilian firefighters DOD employed (staffing level) and the number of DOD civilian firefighters authorized for fiscal years 2019 through 2023.[9]

For our second objective, we obtained documentation on the steps DOD has taken to identify and address the causes of any staffing gaps in its civilian firefighter workforce and compared that documentation with applicable DOD and OPM policies.[10] Additionally, we obtained documentation on the steps DOD has taken to assess and report firefighter staffing data to monitor DOD-wide progress in closing gaps. We compared that documentation with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, including the principle that management establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate results.[11] We also requested Fire and Emergency Services civilian strategic human capital management plans from the military services and DLA. We received plans from the Air Force, the Navy, and DLA, and compared those plans with applicable DOD policies.[12]

For our third objective, we obtained and analyzed documentation and data on 2023 compensation and work schedules for DOD civilian firefighters and local firefighters at the five selected site visit locations.[13] We compared cash compensation and work schedules—in terms of hours worked—for DOD civilian firefighters, including military service and DLA firefighters, to the cash compensation and work schedules of local firefighters at each of the five selected locations. We compared that analysis and the steps DOD has taken to identify the causes of any staffing gaps in its civilian firefighter workforce with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, including the principle that management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving defined objectives.[14] For a detailed description of our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of DOD’s Civilian Firefighter Workforce

DOD civilian firefighters serve in a mission-critical occupation and protect personnel, facilities, and infrastructure that are critical to executing DOD mission-essential functions at installations—such as military bases, camps, or centers. Within DOD, the military services and DLA are the primary components that employ civilian firefighters. In fiscal year 2024, DOD employed approximately 8,800 civilian firefighters.

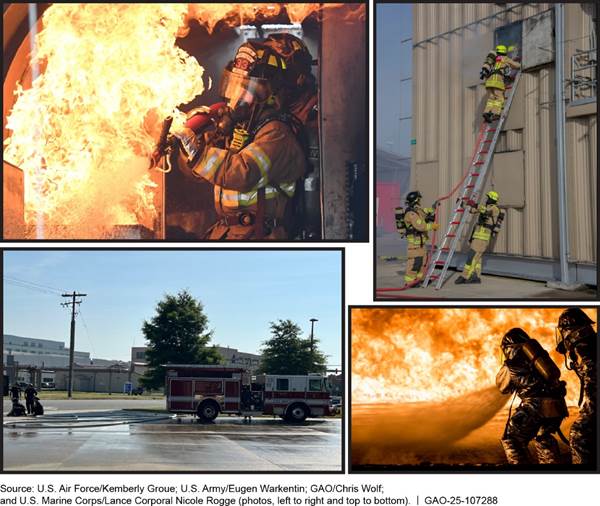

In addition to their responsibilities on DOD installations, DOD civilian firefighters may be called on to help civil authorities under mutual aid agreements, community partnerships and other written agreements, host-nation support agreements, and Defense Support of Civil Authorities.[15] Figure 1 shows DOD civilian firefighters performing various fire-related activities.

DOD uses National Fire Protection Association standards as the framework for the department’s Fire and Emergency Services Certification Program.[16] The Association has developed over 300 standards and codes, including standards for minimum staffing during responses and minimum job performance requirements for firefighters.[17] As a result, the National Fire Protection Association standards identify the level of performance required for DOD civilian firefighters and other Fire and Emergency Services personnel to function effectively.[18]

Strategic Human Capital Management and Closing Mission-Critical Skills Gaps

Since 2001, we have designated strategic human capital management as a government-wide high-risk area.[19] In 2011, after the federal government made progress in this area, we narrowed the focus of the high-risk issue area to the need for agencies to close mission-critical skills gaps. At that time, we noted that agencies faced challenges effectively and efficiently meeting their missions across a number of areas. We further stated that federal agencies needed to continue to (1) take actions to address their specific challenges, and (2) work with OPM—which provides guidance on strategic human capital management for the federal government—to address critical skills gaps.[20]

According to federal regulations, a skills gap arises when there is a difference between the current and projected workforce size and the skills needed to help ensure an agency can meet its mission and achieve current and future goals and objectives.[21] According to OPM, a skills gap can be either a

1. “staffing gap,” in which an agency has an insufficient number of individuals to complete its work; or a

2. “competency gap,” in which an agency has individuals without the appropriate skills, abilities, or behaviors to successfully perform the work.[22]

To address the high-risk designation and focus on closing skills gaps across the federal government, OPM developed an approach to identify agency-specific and government-wide MCOs at greatest risk of such gaps and implement strategies to close identified gaps.[23]

DOD’s MCO process includes seven steps, starting with the identification of MCOs and ending with efforts to close skills gaps.[24] Since 2010, DOD identified civilian firefighters as an MCO, and at times as a high-risk MCO. Specifically, since identifying fire protection as an MCO in fiscal year 2010, DOD has identified staffing gaps in the civilian firefighter workforce on several occasions, including in fiscal years 2010, 2012, and 2019.[25] In 2012, DOD identified fire protection as a “high-risk” MCO—which the department defines as an MCO most at risk for failure due to human capital deficiencies including staffing gaps.[26]

Our prior work has shown that federal agencies’ progress in closing staffing gaps requires demonstrated improvements in agencies’ capacity to perform workforce planning and recruit and retain the appropriate number of staff.[27] For example, in 2024 we reported that DOD was partially consistent with key strategic workforce planning principles on determining needed skills and developing strategies to address staffing gaps in its financial management workforce.[28] Additionally, the 2023 update to our High Risk Series reported that continued federal agency efforts are needed to adequately address staffing gaps within the federal workforce.[29] We further reported that mission-critical staffing gaps pose a high risk to the nation.

DOD Inspector General Has Identified Civilian Firefighter Staffing Challenges

In 2003, DOD’s Inspector General identified challenges DOD faced related to staffing levels within its civilian firefighter workforce. Specifically, in response to concerns expressed by the House Appropriations Committee about minimum firefighter staffing levels, the DOD Inspector General reported on the adequacy and effectiveness of DOD’s Fire and Emergency Services program.[30] In that report, the DOD Inspector General reported the following:

· Inefficient hiring processes adversely affected fire department staffing and resulted in firefighters having to work significant overtime. Further, working such significant overtime could impact the fire department’s ability to accomplish its missions and lead to potential safety risks for firefighters.

· DOD lacked a human capital strategy for the Fire and Emergency Services program. Having such a strategy could help the department identify shortfalls and provide a basis for the human capital resources required to support Fire and Emergency Services programs.

· Material management control weaknesses existed. More specifically, the management of Fire and Emergency Services programs did not ensure that the installations were adequately staffed.

· Fire departments had creatively managed personnel during times of human capital shortfalls, but due to significant overtime, could encounter obstacles to meeting firefighting missions as well as potential safety issues.

We further discuss the findings of the DOD Inspector General report and subsequent actions DOD has taken later in this report.

Entities Involved in DOD’s Civilian Firefighter Workforce Planning

The following entities have roles and responsibilities related to DOD’s workforce planning, including for civilian firefighters:

· The Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service (DCPAS) develops and implements civilian human resources plans, policies, and programs for DOD, such as a strategic workforce planning guide that addresses requirements to identify staffing gaps and develop strategies to close those gaps. DCPAS also advises and assists functional community managers with advancing their capabilities to plan and manage their respective functional community workforces.[31] Additionally, DCPAS issues guidance on the process for identifying and revalidating MCOs and high-risk MCOs within DOD. According to DOD’s Mission Critical Occupations: MCO & High Risk MCO Determination & Revalidation guide, DCPAS works with DOD functional communities, such as the Safety and Public Safety Functional Community, and DOD components, including the military services and DLA, on any requirements related to the MCO list.[32] Specifically, according to that guide, DCPAS works with these functional communities and components on efforts to close staffing gaps within high-risk MCOs. DCPAS also develops and submits MCO-related reports—which include staffing targets and gaps—to OPM annually.

· The Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Safety and Occupational Health manages DOD’s Safety and Public Safety Functional Community, according to DOD officials, which includes the civilian firefighter workforce. Functional community managers are responsible for identifying staffing gaps in their assigned workforces by analyzing staffing levels against projected staffing needs. Based on that analysis, the office develops and implements strategies to mitigate the identified staffing gaps. In addition, the office identifies MCOs from the assigned occupations, which include civilian firefighters and approximately 13 other occupations, such as emergency management and explosives safety.

· The Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Environmental Management and Restoration, as the designated organizational lead for Fire and Emergency Services, oversees the development and implementation of Fire and Emergency Services policy and serves as the principal advisor on Fire and Emergency Services matters for DOD, according to DOD officials.

· The military services and DLA plan, program, and budget for Fire and Emergency Services requirements. In addition, they are required to develop a Fire and Emergency Services Civilian Strategic Human Capital Plan that identifies current and projected staffing requirements, identifies critical staffing gaps, and develops strategies to manage the civilian firefighter workforce to address those gaps.[33] The military services and DLA also make available a cadre of trained human resources consultants to advise component functional community managers on recruitment and retention strategies to address identified competency gaps.[34]

·

OPM collects MCO-related data from DOD and other federal

agencies, including data on staffing targets and gaps for MCOs, and monitors

agency progress in meeting staffing targets.

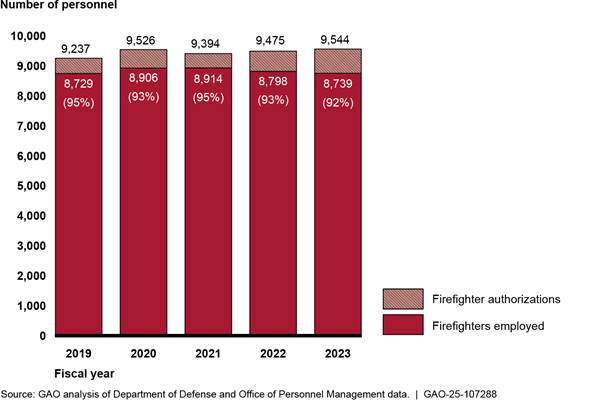

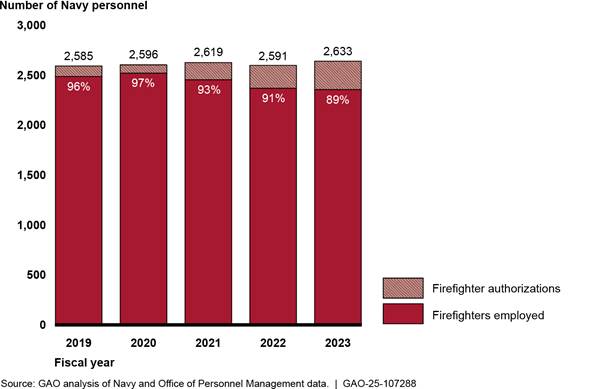

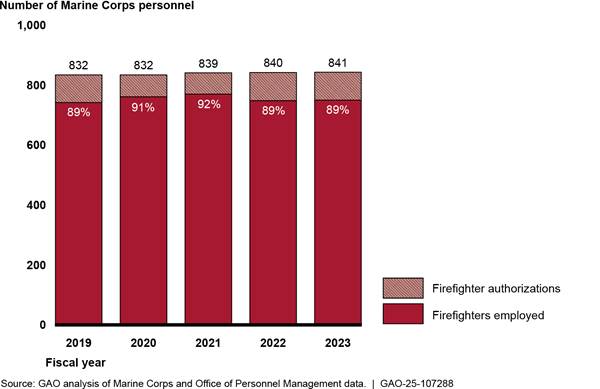

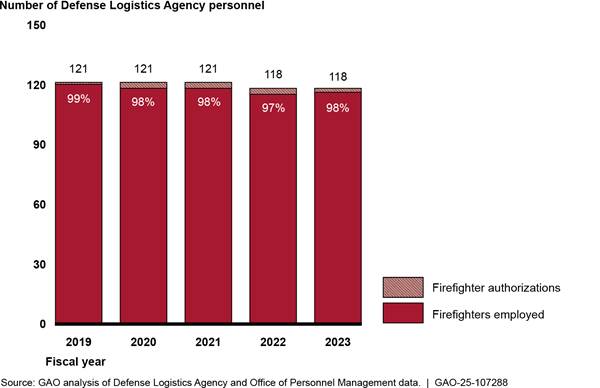

DOD Firefighter Staffing Levels Were Lower Than Authorized in Fiscal Years 2019–2023

According to DOD and OPM data, DOD employed fewer civilian firefighters than authorized in fiscal years 2019 through 2023. Specifically, DOD employed approximately 93 percent of its authorized civilian firefighter positions between fiscal years 2019 and 2023. The difference between authorized and employed civilian firefighters grew from 508 firefighters (5 percent of authorizations) in fiscal year 2019 to 805 firefighters (8 percent of authorizations) in fiscal year 2023, as shown in figure 2.[35] For additional information on DOD civilian firefighter authorizations and staffing levels for each of the military services and DLA, see appendix II.

Figure 2: Department of Defense (DOD) Civilian Firefighter

Actual Staffing Levels Compared with Authorizations, Fiscal Years 2019–2023

Note: For the purposes of this report, DOD civilian firefighter staffing levels include DOD civilian firefighters employed by the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Defense Logistics Agency.

As discussed, in its Fiscal Year 2010–2018 Strategic Workforce Plan, DOD reported that the authorized civilian firefighter staffing levels represent the minimum staffing requirements the department must maintain for safe operation.[36] DOD’s plan further reported that employing fewer firefighters than authorized puts firefighters at increased risk of injury and leads to the potential for increased property loss, environmental damage, or both.

DOD civilian firefighters at the five installations we visited stated that low staffing levels have resulted in working increased mandatory overtime at their respective installations (which we discuss in more detail later in this report).[37] Firefighters at each of the five installations stated that they had worked at least one mandatory overtime shift, with the number of overtime shifts ranging from one shift in the prior 2 months to as many as three shifts per pay period. At one installation, firefighters stated that for the last two shifts, between 20 to 30 percent of the firefighters on duty were working either a voluntary or mandatory overtime shift. According to DOD civilian firefighters we interviewed at one installation, staffing issues have resulted in frequent mandatory overtime, which firefighters use to supplement their incomes. At another installation, firefighters said they enjoy some mandatory overtime, but the amount they are currently working is too much. We further discuss overtime in the DOD civilian firefighter workforce later in this report.

DOD Has Taken Limited Steps to Address Long-Standing Civilian Firefighter Staffing Gaps

DOD has identified several causes of its staffing gaps but

has not addressed those causes through sustained or coordinated efforts. DOD

also has not consistently assessed and reported civilian firefighter staffing

data to monitor progress in closing staffing gaps for this MCO. Additionally,

while DLA has a current strategic plan for its civilian firefighter workforce,

the military services have not consistently developed strategic plans that

assess and forecast future civilian firefighter workforce needs, as required.

DOD Has Identified Some Causes of Staffing Gaps but Does Not Have a Strategy to Address Them

DOD Has Identified Causes of Staffing Gaps

Since 2003, DOD has consistently identified four causes of staffing gaps, as shown in figure 3.[38]

|

DOD Civilian Firefighters’ Perspectives on Competition from Local Fire Departments “City firefighters make more, work less, and see more action. Where would you want to be as a firefighter?” “We work more hours than our local counterparts but make less money.” “The hours are a massive deterrent for new recruits who are also considering local departments.” “It’s harder to recruit younger people because of the lengthy, 144 hour per 2-week pay period schedule.” Source: GAO interviews with Department of Defense (DOD) personnel. I GAO‑25‑107288 |

Competition from local fire departments. DOD civilian firefighters we interviewed at all five installations told us that competition from local fire departments (see sidebar) is a challenge because local fire departments continue to offer higher pay and operate shorter workweeks (which we discuss in more detail later in this report).

In 2013, DOD’s Fiscal Years 2013–2018 Strategic Workforce Plan identified the high level of competition from local municipalities for firefighter personnel and skills as a challenge for the department’s staffing and a cause of staffing gaps.[39] According to that plan, this competition made it difficult for the department to retain its civilian firefighters because municipal fire departments in the same geographic areas as DOD installations had a higher pay scale and worked fewer hours.

Inefficient hiring processes. DOD civilian firefighters and human resources personnel we interviewed at all five installations told us that the hiring process (see sidebar) is a challenge for departments in 2024. During those interviews, the firefighters specifically identified the length of time it takes to complete the hiring process as one of the biggest issues currently facing the civilian firefighter workforce.

|

DOD Civilian Firefighters’ and Human Resources Personnel’s Perspectives on the Hiring Process “The application process is a nightmare and an administrative burden.” “The lengthy hiring process is a primary recruitment and retention issue.” “The hiring process takes too long, which results in applicants giving up and taking other jobs.” “[The ability to hire someone using a hiring authority] has been a game changer. Before, it took very long to hire.” Source: GAO interviews with Department of Defense (DOD) personnel. I GAO‑25‑107288 |

In its 2003 report, the DOD Inspector General stated that DOD’s inefficient hiring processes adversely affected fire department staffing.[40] According to that report, fire chiefs from the Army, Marine Corps, and Navy identified the hiring process for firefighters as an issue, with some vacancies taking more than 6 months to fill. In 2010, DOD also identified the amount of time taken to fill each position as the primary reason for chronic civilian firefighter staffing shortfalls.[41]

Additional missions and outdated standards. DOD civilian firefighters and human resources personnel we interviewed at four of five selected installations stated that the requirement to conduct additional missions and the outdated classification standard (see sidebar) are challenges for the firefighter workforce and lead to firefighter concerns about compensation and career progression.

|

DOD Civilian Firefighters’ and Human Resources Personnel’s Perspectives on Additional Missions and Outdated Standards “Our job responsibilities have continually increased without any additional compensation.” “The classification standard [used to classify positions under the General Schedule pay system] is outdated and restricts the hiring pool.” “The classification standard is over 20 years old and causes career progression issues.” “[General Schedule] grade levels are not commensurate with training and certifications.” Source: GAO interviews with Department of Defense (DOD) personnel. I GAO‑25‑107288 |

The DOD Inspector General’s 2003 report identified civilian firefighters’ participation in additional missions beyond their structural fire suppression, prevention, and education duties as an impediment to fire department staffing. The report identified that DOD firefighters respond to incidents involving hazardous materials and wildland fires as additional missions. The Inspector General further reported that DOD’s policies required civilian firefighters to respond to such incidents, but the policies did not modify staffing requirements to appropriately account for such additional missions or emergencies. Moreover, in 2010 DOD reported that the civilian firefighter classification standard required updating to address changes to the occupation, including capturing certain specialized firefighter duties.[42] According to that report, the outdated classification standard resulted in career progression issues for civilian firefighters.

Lack of funding. DOD civilian firefighters we interviewed at all five installations and a fire chief at one installation told us that funding affects firefighter staffing because of impacts to the availability of recruitment and retention incentives, training, and living conditions at the fire station (see sidebar).

|

DOD Civilian Firefighters’ and a Fire Chief’s Perspectives on Funding “Due to budget cuts, there is not enough funding to approve recruitment, retention, or relocation incentives.” “Poor living conditions—sewage leaks, lack of air conditioning, and 20-year-old mattresses—are a big issue. We’re told there is no money.” “The lack of funding makes it difficult to take advantage of DOD’s training resources.” Source: GAO interviews with Department of Defense (DOD) personnel. I GAO‑25‑107288 |

In its 2003 report, the DOD Inspector General also indicated that DOD policy did not result in increased staffing to cover additional missions, and as a result, caused fire department staffing gaps.[43] Moreover, DOD’s 2003 Fire and Emergency Services Strategic Plan identified funding levels and staffing ceilings as challenges to achieving the department’s strategic goal of reducing loss of life and injuries, and property and environmental damage.[44] Subsequently, in 2013, DOD identified funding reductions as a major contributor to civilian firefighter staffing reductions and the staffing gap.[45]

DOD Has Taken Some Steps to Address Identified Causes of Long-Standing Staffing Gaps, but Does Not Have a Department-Wide Strategy

Since 2003, DOD has taken some department-wide steps to address civilian firefighter staffing gaps, such as updating selected planning documents and beginning to revise the classification standard for the civilian firefighter position. However, these efforts remain limited or incomplete because the department has not developed and implemented a department-wide strategy to mitigate the causes of and close such gaps.

· Strategic plan updates. DOD updated its Fire and Emergency Services Program Strategic Plan in 2003.[46] This updated plan included strategies to help the department (1) comply with minimum staffing requirements identified in DOD policy, and (2) identify additional staffing for new mission requirements. In 2010 and 2013, DOD included strategies to improve civilian firefighter retention in its department-wide civilian employee strategic workforce plans.[47] Both the 2010 and 2013 plans included a strategy focused on improving the consistency and application of medical qualification standards and fitness standards for civilian firefighters. The goal of that strategy was to develop a validated competency model for the civilian firefighter workforce to use in hiring decisions and assessment of gaps.[48] However, since 2013, DOD has not developed similar or related strategies or other elements that would address the causes of civilian firefighter staffing gaps across the department.

· DOD personnel plan. In its 2003 report on the Fire and Emergency Services program, the DOD Inspector General stated that the department was aware of issues associated with the hiring process and was attempting to streamline the process. To address these issues, DOD drafted a personnel plan that included an on-the-spot hiring authority if a severe shortage of candidates existed.[49] The department planned to first use the authority for laboratory employees, and later apply the authority to all civilian employees, according to the DOD Inspector General’s report. However, DOD officials stated that as of 2024, the authority was never applied to all civilian employees.

· Revised classification standard. DOD began revising the civilian firefighter classification standard in 2010 to address career progression issues associated with OPM’s 2004 civilian firefighter classification standard.[50] However, OPM officials stated that as of December 2024, they had not received an official request to update the civilian firefighter classification standard since OPM’s last update to the standard in 2004. Accordingly, the classification standard had not been revised as of December 2024 and OPM’s 2004 civilian firefighter classification standard remains in effect. In December 2024, DOD officials stated that the department began internal efforts to update the civilian firefighter classification standard in June 2024. Officials further stated that the department plans to engage with OPM about the classification standard in fiscal year 2025, among other planned efforts.

· Training on root-cause analysis. In 2016, Safety and Public Safety Functional Community members received training on root-cause analysis to assist them in identifying the root causes of staffing gaps in the civilian firefighter community. However, in November 2024, DOD officials told us they did not know whether the Safety and Public Safety Functional Community conducted the analysis to identify any root causes. At that time, officials also stated they did not have any documentation related to this analysis.

· Use of direct-hire authority. In August 2024, DOD issued a memorandum delegating the use of a direct-hire authority for civilian firefighters to the Secretaries of the Military Departments and Directors of the Defense Agencies.[51] According to the DOD memorandum, use of this direct-hire authority allows the military services and the defense agencies—including DLA—to directly recruit and appoint qualified persons without applying competitive rating and ranking procedures. Under this authority, for example, the military services and DLA will not be required to publicly post job opportunity announcements for civilian firefighters, which can reduce the time it takes to hire civilian firefighters.

Military service and DLA firefighters, fire chiefs, and human resources personnel we interviewed at all five selected installations described steps their respective installations took to address staffing issues. These steps included those associated with the length of the hiring process, competition from local fire departments, and other workforce challenges. However, the steps taken varied by location and, according to officials from the five installations we visited, were not part of any sustained, coordinated departmental efforts to address identified staffing gaps. For example:

· Interviewees at three of the five DOD installations stated that incentives, such as recruitment, retention, and relocation bonuses, were used to attract and retain civilian firefighters. However, DOD officials at the military service headquarters and installation levels stated that recruitment, retention, and relocation incentives are not broadly used across the civilian firefighter workforce.

· At three of the five DOD installations, interviewees reported using direct-hire authorities to shorten the hiring process.[52]

· Interviewees at two of the five DOD installations stated that personnel attended local job fairs and used social media to recruit firefighters.

· At one installation, interviewees stated that time-off awards increased from 8 hours to 24 hours to help improve civilian firefighter retention.

· Interviewees at another installation reported having an ongoing contract to build an application for firefighter and police recruiting. Officials stated they designed the application to increase awareness of open jobs within the potential recruit pool and to streamline the hiring process. Officials did not have an estimated completion date for that application.

According to DOD policy, functional community managers are responsible for mitigating identified staffing gaps in their respective communities.[53] According to DOD officials, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Safety and Occupational Health is the Safety and Public Safety Functional Community Manager, covering the civilian firefighter workforce. Additionally, federal regulations require DOD and other federal agencies to address staffing gaps within MCOs, which includes DOD civilian firefighters.[54] Specifically, DOD policy and federal regulations require the development of a strategy to mitigate causes of and close identified gaps.[55] However, the department’s efforts to address DOD civilian firefighter staffing gaps have remained limited and incomplete because the department has not developed and implemented a department-wide strategy that would position it to make more comprehensive and complete progress toward addressing its challenges.

In December 2024, DOD officials stated that personnel turnover and organizational changes within the offices of Force Safety and Occupational Health and the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Environmental Management and Restoration resulted in knowledge gaps related to the roles and responsibilities associated with strategy development for the civilian firefighter workforce. While turnover and organizational changes have occurred and very likely complicate efforts to address these challenges, the staffing challenges have persisted for decades. The development and implementation of a department-wide strategy would help provide continuity in the face of such turnover.

Until the department develops and implements such a department-wide strategy that is aimed at comprehensively mitigating the causes of and closing the gaps, DOD’s efforts will remain limited in scope and the department will be unable to address long-standing staffing gaps in its civilian firefighter workforce. As previously discussed, failure to close such staffing gaps puts firefighters at increased risk of injury and leads to the potential for increased property loss, environmental damage, or both.

DOD Has Not Consistently Assessed and Reported Firefighter Staffing Data to Monitor Progress in Closing the MCO’s Staffing Gaps

DOD has taken some steps to address identified staffing gaps in the civilian firefighter workforce, as noted above, but the department has not consistently assessed staffing data to set annual staffing targets for that workforce or reported on efforts to close staffing gaps. DOD and other federal agencies use the MCO process to monitor and address staffing gaps and to close such gaps for those occupations at the greatest risk of having them.[56] Beginning in fiscal year 2010, DOD has generally identified civilian firefighters as an MCO or high-risk MCO. For example, DOD identified civilian firefighters as an MCO in 2010; a high-risk MCO in fiscal years 2012 through 2019; and an MCO in fiscal year 2024.

However, DOD did not identify its civilian firefighter workforce as an MCO in fiscal years 2020 through 2023. According to DOD officials, the department may have accidentally omitted civilian firefighters from the MCO list from fiscal year 2020 through fiscal year 2023, but the officials were unable to confirm this based on their records. Further, although civilian firefighters were not identified as an MCO on the department’s MCO list during this time frame, DOD included civilian firefighters in a 2023 MCO report submitted to OPM. DOD officials stated that the department’s inclusion of firefighters in the report may have also been an oversight, but they did not provide any documentation to confirm.

Since designating civilian firefighters as an MCO in fiscal year 2010, DOD has inconsistently assessed staffing data to set annual staffing targets and has reported on its efforts to close gaps in identified targets three times. Specifically, DOD took steps to assess staffing data and set annual targets in fiscal years 2010, 2012, and 2019.[57] However, DOD has not set annual staffing targets for civilian firefighters or reported on its progress closing staffing gaps since 2019.

According to OPM’s Workforce Planning Guide, workforce planning is a systematic process of analyzing and assessing the workforce against set targets to mitigate the gaps between the current workforce and future mission and human capital needs.[58] According to a memorandum from OPM, DOD, and the Department of Labor, agencies must set annual staffing targets for MCOs—which they use to calculate staffing gaps—and report annually to OPM on their progress with closing staffing gaps.[59] According to DOD policy, the heads of the components should develop, manage, execute, and assess manpower allocations and resources, as part of their respective strategic workforce plans.[60] Moreover, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government state that management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate results.[61]

DOD has not consistently assessed staffing data on its civilian firefighter workforce to set targets for the MCO or reported on the department’s progress closing staffing gaps, as required, because management has not implemented monitoring activities to ensure that these requirements are addressed. DCPAS and Safety and Public Safety Functional Community officials stated that they were new to their roles and, as a result, were unaware of the requirements associated with setting MCO staffing targets and reporting on the department’s progress closing staffing gaps. However, DOD did not consistently set annual staffing targets for the civilian firefighter MCO and report on the department’s progress closing staffing gaps for a number of years before these officials took their current roles.

By implementing monitoring activities to ensure that the Safety and Public Safety Functional Community and the heads of the DOD components, in collaboration with DCPAS, set annual civilian firefighter staffing targets and report progress closing staffing gaps to OPM, DOD will have better assurance it is addressing MCO-related reporting requirements. Furthermore, it will have better visibility over the status of its civilian firefighter workforce, including necessary information about its progress achieving staffing targets, and be better positioned to address any staffing gaps that may exist.

The Military Services’ Strategic Plans Do Not Consistently Assess and Forecast Future Civilian Firefighter Workforce Needs

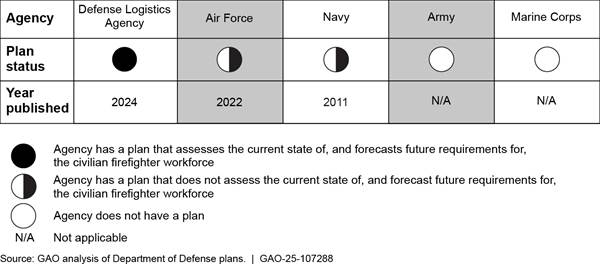

The DOD components, including the military services and DLA, have been inconsistent in their efforts to develop strategic human capital plans to assess the state of and consider future needs for their respective civilian firefighter workforces, as shown in figure 4. As of November 2024, DLA had developed a strategic human capital plan to assess the current and future needs of its civilian firefighter workforce. However, the military services have not consistently developed such plans.[62]

Based on our review of the existing plans, DLA’s 2024 plan assesses the current state of the civilian firefighter workforce and forecasts future workforce requirements.[63] For example, the DLA plan includes an environmental scan, which assesses the current state of the civilian firefighter workforce and summarizes factors influencing future requirements. The plan states that firefighter positions at the General Schedule (GS)-7 grade level are harder to fill due to position certification requirements, including driver-operator pumper and hazardous material requirements.[64] To address this, the plan states that DLA should update the position description to allow candidates to obtain those certifications within 2 years of employment.

In comparison, the Air Force and Navy have taken steps to develop strategic human capital plans, but their plans do not assess the current state of the civilian firefighter workforce or forecast future workforce requirements. Further, the Navy’s most recent plan, which was last updated in 2011, is outdated. The Army and Marine Corps do not have strategic human capital plans for their civilian firefighter workforces or estimated completion dates for those plans, according to DOD officials.

DOD policy requires components, including the military services and defense agencies such as DLA, to develop Fire and Emergency Services civilian strategic human capital plans that assess the current state of, and forecast projected requirements for, their respective civilian firefighter workforces.[65] However, the military services’ plans do not consistently reflect the current state of the civilian firefighter workforce or forecast future requirements. This is due to service leadership not appropriately updating their plans to include this information. Specifically, Air Force leadership did not ensure that they included all required elements in the Air Force’s plan. Similarly, Navy leadership did not ensure that they included all required elements and updated the Navy’s plan in a timely manner.

Air Force and Navy officials did not have information about why their plans did not assess the current state of the civilian firefighter workforce and forecast future workforce requirements. However, Air Force officials told us they expect to publish an updated plan in 2025 that addresses these areas.

Additionally, the Army and Marine Corps leadership did not develop plans as required. As of November 2024, the officials noted that these services did not have development time frames or estimated completion dates for their plans. By ensuring the development of civilian firefighter strategic human capital plans consistent with DOD policy that assess the current state of their civilian firefighter workforces and forecast future requirements for those workforces, the military services will have access to information needed to more effectively address staffing gaps. Moreover, having such information will help the services manage risks associated with staffing gaps in the civilian firefighter workforce in alignment with the plans.

DOD Civilian Firefighters at Selected Locations Worked More Hours Than Local Firefighters and Compensation Varied

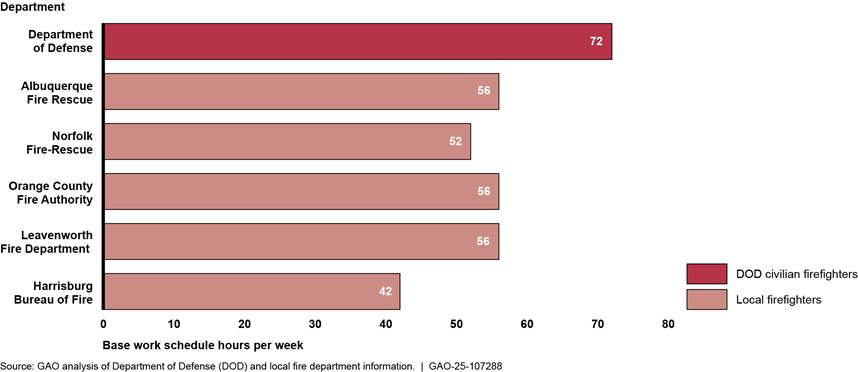

Our analyses of DOD and local fire department documentation and data determined that DOD civilian firefighters at all five selected locations worked more hours per week than local firefighters in 2023, but compensation varied. Specifically, DOD civilian firefighters worked more hours per week than local firefighters in terms of standard base work schedules and more total hours than local firefighters. Additionally, DOD civilian firefighters at all five selected locations earned less per hour in base compensation than local firefighters, but total cash compensation varied between DOD civilian and local firefighters.[66]

DOD Civilian Firefighters Worked More Hours Than Local Firefighters at Five Selected Locations

Standard Base Work Schedules

At all five selected locations, DOD civilian firefighters worked longer standard schedules than local firefighters in 2023, as shown in figure 5.[67] According to the Federal Firefighter Pay Reference Guide, DOD civilian firefighters typically work a 72-hour per week standard schedule.[68] In comparison, according to the local fire department’s collective bargaining agreements and other documentation at our five selected locations, firefighters typically work between 42 and 56 hours per week.[69]

Figure 5: Standard Base Work Schedule for DOD Civilian Firefighters and Local Firefighters, by Selected Location, 2023

Notes: DOD civilian firefighters typically work 144 hours per 2-week pay period or 72 hours per week. Defense Civilian Personnel Advisory Service, Federal Firefighter Pay: Reference Guide PT-820 (2018).

Local fire department locations were in Albuquerque, New Mexico; Norfolk, Virginia; Orange County, California; Leavenworth, Kansas; and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

|

DOD Civilian Firefighter 72-Hour Workweek The length of shifts worked to meet the DOD civilian firefighter 72-hour workweek can vary. According to fire chiefs from the four military services, DOD civilian firefighters work either 24-hours on, 24-hours off or 48-hours on, 48-hours off schedules. DOD firefighters at three of the installations we visited work a 48-hour alternating schedule, either 48-hours on, 48-hours off or 48-hours on, 72-hours off. Firefighters at two installations we visited said their fire department recently switched from the 24-hour alternating schedule to the 48-hour alternating schedule. Those firefighters said the 48-hour schedule has improved their morale, quality of life, and work-life balance. |

Source: GAO interviews with Department of Defense (DOD) personnel. I GAO‑25‑107288

According to DOD civilian firefighters and installation human resources officials at four of the five selected locations, the 72-hour per week standard base work schedule causes retention issues because firefighters perceive they can work “better” schedules at the local fire departments. For example, according to DOD installation human resources officials at two selected locations, the 72-hour per week work schedule is often more intense than firefighters anticipated and causes DOD civilian firefighters to frequently seek employment at local fire departments that offer work schedules with fewer work hours per week.

|

DOD Civilian Firefighter Daily Work Schedule Example DOD civilian firefighters at four of the five locations we visited described similar daily work schedules: Shifts begin around 7:00 a.m. Firefighters generally check their vehicles and equipment to ensure proper operation and functioning. During the workday, they conduct training exercises and classroom and online training courses, as well as physical fitness training. Civilian firefighters also complete various administrative tasks during their day. Daily work tasks are completed by approximately 3:00 p.m.–4:00 p.m., at which point they begin their personal time. During their personal time, firefighters are free to eat, relax, or sleep. Firefighters respond to calls throughout their 24- to 48-hour shifts. |

Source: GAO interviews with Department of Defense (DOD) personnel. I GAO‑25‑107288

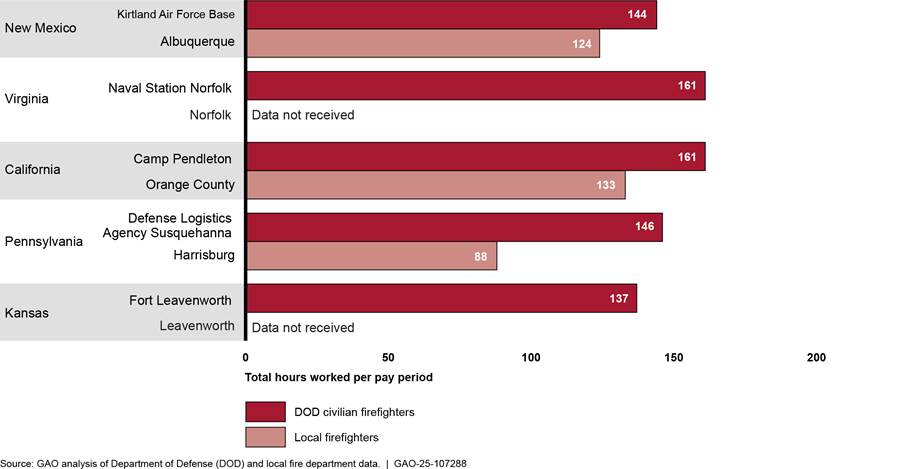

Total Hours Worked

DOD civilian firefighters worked more total hours, which includes standard work schedule and overtime, per pay period than local firefighters at the three selected locations for which we received data, as shown in figure 6.[70] Specifically, at those three locations, DOD civilian firefighters worked 150 hours per pay period on average. In comparison, local firefighters worked 115 hours per pay period on average at the three corresponding local fire departments. For example, firefighters at Camp Pendleton worked 161 hours per pay period, while local firefighters in Orange County worked 133 hours per pay period. In addition, total hours worked by DOD civilian firefighters varied between the three selected DOD locations for which we had corresponding local fire department data.

Figure 6: Average Total Hours Worked by DOD Civilian Firefighters and Local Firefighters per 2-Week Pay Period, by Selected Location, 2023

Notes: DOD and local fire department data on total hours worked differed by reporting period. The following departments reported data by calendar year: Orange County Fire Authority. The following departments reported data by fiscal year: DOD, Albuquerque Fire Rescue, and Harrisburg Bureau of Fire.

We received data on total hours worked from three local fire departments in Albuquerque, New Mexico; Orange County, California; and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. We did not receive data from local fire departments in Norfolk, Virginia and Leavenworth, Kansas; therefore, we did not include them in the comparison.

Use of Overtime

DOD civilian firefighters and local firefighters both worked overtime hours beyond their standard work schedules in 2023.[71] Specifically, DOD firefighters worked an average of 3 overtime hours per week across all five selected locations. In comparison, local firefighters worked an average of 5 overtime hours per week at three selected locations.[72] However, as discussed, DOD civilian firefighters at all five selected locations work longer standard schedules than local firefighters at the three selected locations. Therefore, the DOD civilian firefighters worked more total hours per pay period at the five selected locations in 2023 even when considering that local firefighters worked more overtime hours per week at three selected locations.

DOD civilian firefighters at all five selected locations stated that mandatory overtime has become more frequent and has caused quality of life issues such as fatigue, poor work-life balance, and other family issues, such as high divorce rates (see sidebar). DOD civilian firefighters at one installation said they generally receive little or no advance notice for a mandatory overtime shift. Those firefighters further stated that shifts cannot be refused, so any plans that the firefighters scheduled would need to be canceled.

|

DOD Civilian Firefighters’ Perspectives on Mandatory Overtime “We’re beat down. There’s too much [mandatory overtime]. No one listens. No one helps.” “[Mandatory overtime] results in high divorce rates in the DOD civilian firefighter workforce.” “[Firefighters] leave for various reasons including…excessive mandatory overtime.” Source: GAO interviews with Department of Defense (DOD) personnel. I GAO‑25‑107288 |

According to DOD civilian firefighters at one selected location, not all overtime is problematic because some firefighters choose to work overtime to supplement their income. Firefighters also use voluntary overtime to control their schedule. For example, firefighters at one selected location said they may volunteer for an overtime shift to protect their scheduled days off. By volunteering for the overtime shift, firefighters said they are able to move their name to the bottom of the list and temporarily avoid mandatory overtime. Alternatively, firefighters at another location said scheduling mandatory overtime is a collaborative effort where firefighters volunteer for a shift to help ensure someone who needs a particular day off can get the time off.

Compensation Varied Between DOD Civilian Firefighters and Local Firefighters at Five Selected Locations

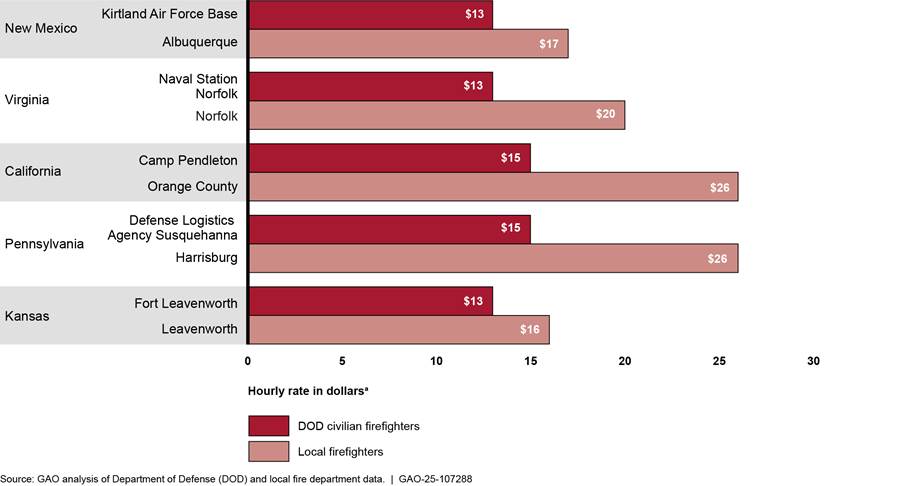

Hourly Base Compensation

|

Calculating DOD Civilian Firefighters’ Annual Salary The annual salary for DOD civilian firefighters consists of two parts—base compensation (i.e., salary according to the General Schedule (GS) pay scale, including locality pay or a higher special rate supplement) and overtime pay. DOD firefighters have a 53-hour weekly overtime threshold—as provided in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) for FLSA-nonexempt firefighters and in 5 U.S.C. 5542(f) for FLSA-exempt firefighters. Therefore, the DOD civilian firefighter work schedule includes 19 overtime hours within their standard 72-hour weekly pay. DOD calculates firefighter base compensation using the Office of Personnel Management’s GS pay scale salary divided by 2,756 annual hours (i.e., 53 hours per week multiplied by 52 weeks per year). For overtime pay, DOD multiplies base compensation by 1.5 for FLSA-nonexempt and some FLSA-exempt firefighters. For example, a DOD civilian FLSA-nonexempt firefighter in the Washington, D.C. area at the GS-7, Step 1 level who worked 3,744 hours in 2024 would have earned the following cash compensation: · 2024 GS-7, Step 1 annual rate for the D.C. locality: $55,924 · Basic rate of pay: 55,924/2,756 annual hours = $20.29 · Overtime rate of pay: 1.5(20.29) = $30.44 · Total annual pay: 2,756(20.29) + 988(30.44) = $85,994 FLSA-exempt firefighter pay calculations are similar to the example above. However, the overtime pay calculations may differ based on the overtime cap for all GS-exempt employees. For those employees who exceed the GS-10, step 1 hourly rate of basic pay, the overtime hourly rate is equal to the greater of either 1.5 times the GS-10, step 1 rate or the employee’s hourly rate of basic pay. |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) documentation. | GAO‑25‑107288

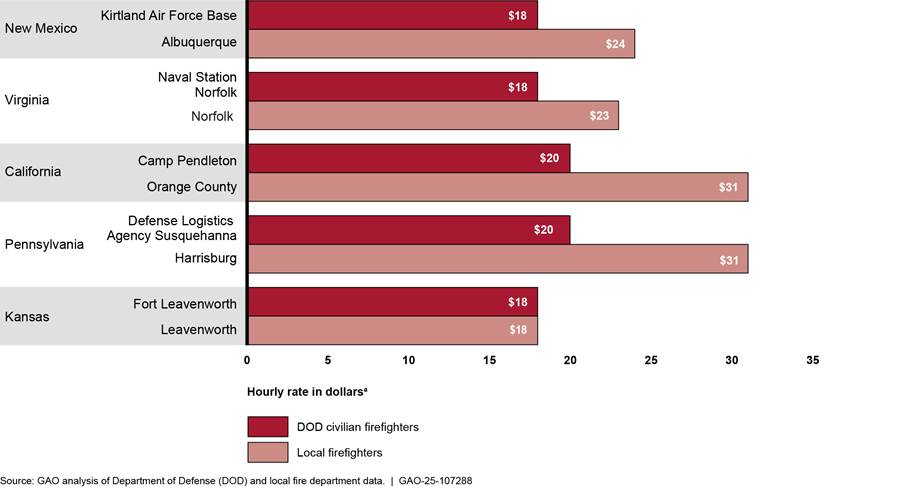

At all five selected locations, local firefighters made more overall per hour in base compensation than DOD civilian firefighters in 2024, as shown in figures 7 and 8.[73] Specifically, entry-level (early career) local firefighters at the five selected locations made approximately 53 percent more on average than entry-level DOD civilian firefighters at the corresponding DOD location.[74] For example, entry-level local firefighters in Orange County, California made approximately 81 percent more on average than DOD civilian firefighters at Camp Pendleton, while those in Leavenworth, Kansas made approximately 19 percent more on average than DOD civilian firefighters at Fort Leavenworth, as shown in figure 7.[75] See appendix I for information on the ranks analyzed for entry-level (early career) firefighters.

Notes: DOD and local fire department data on hourly base compensation differed by reporting period. The following departments reported data by calendar year: DOD, Harrisburg Bureau of Fire, and Leavenworth Fire Department. The following departments reported data by fiscal year: Albuquerque Fire Rescue, Norfolk Fire-Rescue, and Orange County Fire Authority.

Amounts rounded to the nearest whole dollar.

aWe determined the hourly base compensation by dividing annual salary by the number of non-overtime hours in the standard work week multiplied by 52 weeks in the year. Annual salary is based on Office of Personnel Management General Schedule and local fire department pay tables for each location. DOD civilian firefighters at all five locations and local firefighters at Albuquerque, Orange County, and Leavenworth work 53 non-overtime hours in their standard work week. Local firefighters at Norfolk and at Harrisburg work 52 and 40 non-overtime hours in their standard work week, respectively. Actual hourly base compensation may differ.

Additionally, fully certified (mid-career) local firefighters at the five selected locations made approximately 33 percent more on average than fully certified DOD civilian firefighters at the corresponding DOD location, as shown in figure 8. For example, fully certified local firefighters in Orange County, California made on average 55 percent more than the DOD civilian firefighters at Camp Pendleton, while firefighters in Norfolk, Virginia made 27 percent more than DOD civilian firefighters at Naval Station Norfolk. See appendix I for information on the ranks analyzed for fully certified (mid-career) firefighters.

Notes: DOD and local fire department data on hourly base compensation differed by reporting period. The following departments reported data by calendar year: DOD, Harrisburg Bureau of Fire, and Leavenworth Fire Department. The following departments reported data by fiscal year: Albuquerque Fire Rescue, Norfolk Fire-Rescue, and Orange County Fire Authority.

Amounts rounded to the nearest whole dollar.

aWe determined the hourly base compensation by dividing annual salary by the number of non-overtime hours in the standard work week multiplied by 52 weeks in the year. Annual salary is based on Office of Personnel Management General Schedule and local fire department pay tables for each location. DOD civilian firefighters at all five locations and local firefighters at Albuquerque, Orange County, and Leavenworth work 53 non-overtime hours in their standard work week. Local firefighters at Norfolk and at Harrisburg work 52 and 40 non-overtime hours in their standard work week, respectively. Actual hourly base compensation may differ.

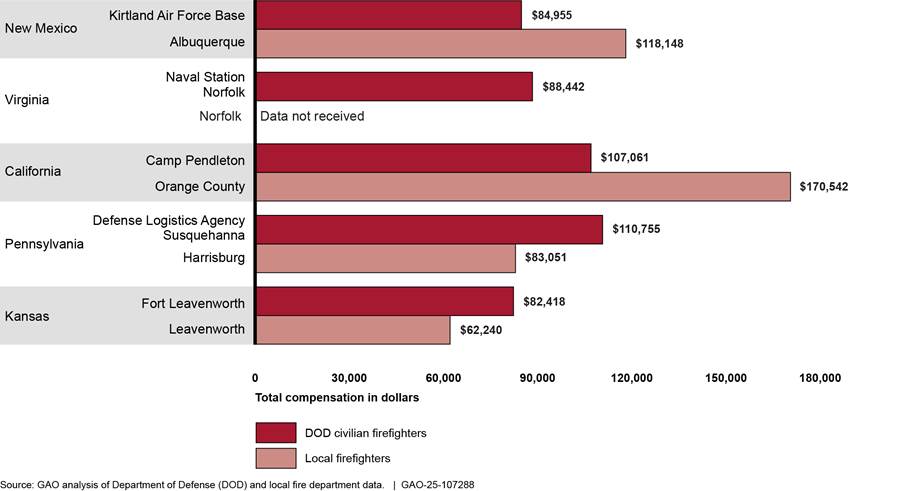

Total Cash Compensation

Total cash compensation varied between DOD civilian firefighters and local firefighters at four of the five selected locations in 2023, as shown in figure 9.[76] Specifically, DOD civilian firefighters at our two selected locations in New Mexico (Kirtland Air Force Base) and California (Camp Pendleton) made less in total cash compensation than the local firefighters at the corresponding local fire departments. At those two locations, DOD civilian firefighters earned approximately 31 percent less than local firefighters on average. In comparison, DOD civilian firefighters at our two selected locations in Pennsylvania (Defense Logistics Agency, Susquehanna) and Kansas (Fort Leavenworth) made more in total cash compensation than local firefighters at the corresponding local fire departments. At those two locations, DOD civilian firefighters earned approximately 33 percent more than local firefighters. Firefighters at two installations stated that DOD civilian firefighters may make more than their local counterparts, but only because they work significantly more hours.

Figure 9: Comparison of Average Total Cash Compensation for DOD Civilian Firefighters and Local Firefighters, by Selected Location, 2023

Note: DOD and local fire department data on total cash compensation differed by reporting period. The following department reported data by calendar year: Orange County Fire Authority. The following departments reported data by fiscal year: DOD, Albuquerque Fire Rescue, Harrisburg Bureau of Fire, and Leavenworth Fire Department.

Retirement Benefits and Leave Accrual

Total compensation includes cash compensation, as discussed above; benefits, such as retirement; and leave accrual, among others. According to OPM, these benefits are designed to make federal employee (i.e., DOD civilian firefighter) careers rewarding while balancing work and family life.[77] At all five selected locations, DOD civilian firefighters and officials—including an installation fire chief and human resources personnel—expressed concerns about other aspects of firefighter compensation and benefits. Those concerns included the following:

· Retirement benefits. DOD civilian firefighters at all five locations, including an installation fire chief, said that DOD civilian firefighter retirement benefits are complex and do not account for all hours worked. Specifically, firefighters at one installation stated that their retirement benefit calculations are confusing and said they often speak to retirees to get a better sense of their retirement benefits. At another installation, the fire chief and firefighters stated that DOD’s human resources department is often unable to provide accurate retirement information. Those firefighters told us about colleagues who were given incorrect retirement dates. Additionally, the fire chief at that installation stated that they hired outside experts to help firefighters understand their retirement benefits because of the challenges they faced obtaining accurate information. Further, as discussed, DOD civilian firefighters at three selected locations worked an average of 3 hours beyond their standard 19-hour overtime work requirement. Firefighters at all five selected locations told us that not receiving credit for overtime in their retirement pay calculations is one of the challenges of being a DOD firefighter.[78]

· Leave accrual. DOD civilian firefighters and human resources personnel at four of the five selected locations said that the leave accrual rate for firefighters is disproportionate when compared to other federal employees. However, DOD guidance states that employees with an uncommon tour of duty, such as firefighters with a standard 72-hour weekly work schedule, accrue leave directly proportional to the standard leave accrual rates for employees who accrue and use leave on the basis of an 80-hour biweekly tour of duty.[79] Firefighters at two installations told us they feel the annual leave accrual rate for firefighters is disproportionate to that of other federal civilian employees, and can encourage sick leave abuse to ensure firefighters can take needed time off. The firefighters further stated that in such instances, sick leave is taken for vacation or to ensure that special events are not missed.

Our analysis of firefighter work schedules and compensation at five selected locations showed that local firefighters worked fewer hours and were paid higher hourly base rates than DOD civilian firefighters. Additionally, we identified areas of concern that are causing dissatisfaction among DOD firefighters, such as increased mandatory overtime and issues with retirement benefits. According to federal internal control standards, management should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving defined objectives.[80] Studying these issues across the department would help inform DOD’s ongoing efforts to address civilian firefighter staffing gaps and their causes.

As previously discussed, developing and implementing a department-wide strategy to mitigate and close staffing gaps could help DOD make more progress addressing challenges with its civilian firefighter workforce. By including an analysis of work schedule and compensation differences between DOD and local fire departments within this strategy, DOD would be positioned to make more comprehensive and complete progress mitigating and closing its civilian firefighter staffing gaps that put firefighters at risk of injury or could result in property loss, environmental damage, or both.

Conclusions

DOD civilian firefighters support efforts to safeguard and advance vital U.S. national interests by ensuring safety and minimizing loss on DOD installations. However, DOD has faced challenges over the years related to staffing levels within its civilian firefighter workforce. Since 2003, DOD has identified several causes of the staffing gaps within the civilian firefighter workforce, including competition with local fire departments’ work schedules and compensation. However, it has not developed a DOD-wide strategy to mitigate and close those staffing gaps, as required by DOD policy.[81] By developing such a DOD-wide strategy and including an analysis of work schedule and compensation differences, the department will be better positioned to take sustained and coordinated action to address long-standing staffing gaps in its civilian firefighter workforce.

In addition, DOD has designated civilian firefighters as an MCO due to long-standing staffing gaps in the workforce. However, it has not consistently assessed and reported firefighter staffing data to monitor department-wide progress in closing those gaps. By implementing monitoring activities to verify that DOD sets annual civilian firefighter staffing targets and reports progress closing staffing gaps to OPM as required, DOD will have better assurance that it is addressing MCO-related reporting requirements. It will also ensure the department has visibility into staffing levels for its civilian firefighter workforce.

Finally, while DLA developed a strategic human capital plan that assesses the current state of, and forecasts future requirements for, its civilian firefighter workforce, the four military services have not consistently developed similar plans. By following existing DOD policy to develop and implement current strategic workforce plans that assess and forecast needs for the civilian firefighter workforce, the Air Force, Navy, Army, and Marine Corps will be better able to more effectively address staffing gaps within their respective services and manage related risks.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making a total of six recommendations, including two to DOD, two to the Navy, and one each to the Air Force and Army.

The Secretary of Defense should ensure the Safety and Public Safety Functional Community Manager (Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Safety and Occupational Health) develops and implements a DOD-wide strategy to mitigate and close staffing gaps in the civilian firefighter workforce, which should include an analysis of work schedule and compensation differences between DOD and local fire departments that may affect staffing levels. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness implements monitoring activities to verify that the Safety and Public Safety Functional Community and the heads of the DOD components, in collaboration with DCPAS, set annual staffing targets for civilian firefighters and report progress in closing staffing gaps to OPM, as required. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of the Air Force should update and implement the Air Force’s Fire and Emergency Services civilian strategic human capital plan and ensure that the updated plan assesses the current state of the Air Force’s civilian firefighter workforce and forecasts future workforce requirements. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of the Navy should update and implement the Navy’s Fire and Emergency Services civilian strategic human capital plan and ensure that the updated plan assesses the current state of the Navy’s civilian firefighter workforce and forecasts future workforce requirements. (Recommendation 4)

The Secretary of the Army should develop and implement a Fire and Emergency Services civilian strategic human capital plan and ensure that the plan assesses the current state of the Army’s civilian firefighter workforce and forecasts future workforce requirements. (Recommendation 5)

The Secretary of the Navy, in coordination with the Commandant of the Marine Corps, should develop and implement a Fire and Emergency Services civilian strategic human capital plan for the Marine Corps and ensure that the plan assesses the current state of the Marine Corps’ civilian firefighter workforce and forecasts future workforce requirements. (Recommendation 6)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD and OPM for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix III, DOD concurred with five recommendations and partially concurred with one recommendation. DOD also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. OPM did not provide comments on our draft report.

DOD partially concurred with the recommendation that the Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness implements monitoring activities to verify that DCPAS and the Safety and Public Safety Functional Community set annual staffing targets for civilian firefighters and report progress closing staffing gaps to OPM, as required. In its comments, DOD stated that the Safety and Public Safety Functional Community—managed within the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness—will support the establishment of monitoring activities and advocate for and support the DOD components in meeting the intent of the recommendation. The department stated that, while DCPAS could serve as the focal point for the components reporting information to OPM, the individual component heads also have responsibility for setting staffing targets for civilian firefighters. As discussed in our report, DCPAS develops and submits MCO-related reports—which include staffing targets and gaps—to OPM annually.

Based on DOD’s comments, we revised the addressees of this recommendation to reflect the components’ roles in setting staffing targets. We are encouraged by the department’s acknowledgment of the actions it will take to implement our recommendation and believe that such actions, if fully implemented, would address our recommendation.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Army, the Secretary of the Navy, the Secretary of the Air Force, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, and the Director of the Office of Personnel Management. In addition, this report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at williamsk@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Kristy E. Williams

Director, Defense Capabilities and Management

This report (1) compares Department of Defense (DOD) civilian firefighter staffing levels with authorized positions, (2) assesses the extent to which DOD has addressed civilian firefighter staffing gaps, and (3) compares DOD civilian firefighter work schedules and compensation with local government firefighter work schedules and compensation at selected locations.

To address these objectives, we focused on DOD, specifically the military services—the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force—and the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), which together employ approximately 95 percent of all federal structural civilian firefighters.[82] Additionally, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of locations where DOD civilian firefighters are employed and conducted a series of virtual and in-person site visits (see table 1). We selected five site visit locations based on (1) military service (one location for each military service and DLA), (2) geographic diversity (one installation in each census region), (3) rural versus urban setting (finding a percentage of each using 2020 Census data by county or location within a metropolitan statistical area), (4) diversity in the size of the fire department, and (5) diversity in annual firefighter wages (one location from each of the four Bureau of Labor Statistics annual wage categories).

|

Military service |

Installation |

Location |

Corresponding local departmenta |

|

Air Force |

Kirtland Air Force Base |

Albuquerque, NM |

Albuquerque Fire Rescue |

|

Navy |

Naval Station Norfolk |

Norfolk, VA |

Norfolk Fire-Rescue |

|

Marine Corpsb |

Camp Pendleton |

Orange County, CA |

Orange County Fire Authority |

|

Army |

Fort Leavenworth |

Leavenworth, KS |

Leavenworth Fire Department |

|

Defense Logistics Agencyb |

Susquehanna Distribution Center |

New Cumberland, PA |

Harrisburg Bureau of Fire |

Source: GAO analysis of Department of Defense (DOD) and local fire department information. | GAO‑25‑107288

aWe used data from corresponding local fire departments to compare DOD civilian firefighter and local firefighter work schedules and cash compensation.

bVirtual site visit location.

At the five DOD locations, we interviewed a total of 10 groups of civilian firefighters, five installation fire chiefs, and five groups of installation human resources personnel responsible for fire and emergency services occupations. Specifically, for our interviews with DOD civilian firefighters, we interviewed junior- and senior-level firefighters separately at all locations to encourage more candid responses.[83] We asked DOD civilian firefighters questions about their individual job experiences, compensation, and work hours, as well as broader questions about recruitment and retention at their installation. Because we did not select participants using a statistically representative sampling method, the perspectives obtained are nongeneralizable and therefore cannot be projected across DOD’s workforce of approximately 8,800 civilian firefighters. While the information obtained from these interviews is not generalizable to the larger DOD civilian firefighter population, it provides valuable perspectives from the civilian firefighters and DOD officials and illustrative examples about aspects of the DOD civilian firefighter workforce from the locations we visited.

Objective 1: Staffing Levels

To compare DOD civilian firefighter staffing levels with authorized positions, we obtained and reviewed DOD civilian firefighter authorization data from the four military services included in our review and DLA.[84] We also obtained and analyzed DOD civilian firefighter staffing data from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to determine the number of DOD civilian firefighters employed by the four military services and DLA from fiscal year 2019 through fiscal year 2023.[85] Specifically, we analyzed data on funded DOD civilian firefighter authorizations and DOD civilian firefighter staffing levels for fiscal years 2019 through 2023 to identify any differences. During our site visits to DOD installations, we interviewed civilian firefighters, the installation fire chief, and installation human resources personnel at each site about any challenges related to staffing levels and shortages in the firefighter workforce.

Objective 2: Addressing Staffing Gaps

To assess the extent to which DOD has addressed civilian firefighter staffing gaps, we obtained documentation on the steps DOD has taken to address any staffing gaps in the civilian firefighter workforce—including reports and plans identifying causes of staffing gaps and steps DOD has taken—and compared that documentation with applicable DOD and OPM policies.[86] We also obtained documentation on the steps DOD has taken to assess and report firefighter staffing data to monitor DOD-wide progress in closing gaps. We compared that documentation with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, including the principle that management should establish and operate monitoring activities to monitor the internal control system and evaluate results.[87] Additionally we requested the Fire and Emergency Services civilian strategic human capital management plans from the military services and DLA. We received plans from the Air Force, the Navy, and DLA, and compared those plans to applicable DOD policies.[88] During our site visits, we interviewed civilian firefighters, the installation fire chief, and installation human resources personnel at each site about recruitment or retention challenges in their respective civilian firefighter workforces, and any ongoing or potential installation efforts to address such challenges.

Objective 3: Comparing Work Schedules and Compensation