TEMPORARY ASSISTANCE FOR NEEDY FAMILIES

HHS Needs to Strengthen Oversight of Single Audit Findings

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107291. For more information, contact James R. Dalkin at dalkinj@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107291, a report to congressional requesters

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

HHS Needs to Strengthen Oversight of Single Audit Findings

Why GAO Did This Study

HHS annually provides about $16.5 billion in TANF grant funds to states to provide cash, supportive services, and non-cash assistance to low-income individuals and families with children. GAO was asked to review TANF spending and related control practices.

This report examines the nature and extent of TANF single audit findings, as of April 30, 2024, and the extent to which HHS has conducted oversight of TANF single audit findings, among other objectives. This report is part of a series of recent reports on TANF that GAO issued (GAO-25-107235, GAO-25-107290, and GAO-25-107226).

GAO reviewed states’ timeliness in submitting 2023 single audit reports and identified the number of TANF-related findings and any commonalities in the most recent reports. GAO interviewed HHS officials and reviewed HHS policies and procedures for following up on TANF single audit findings; issuing management decisions; and imposing penalties on, or alternatively obtaining corrective compliance plans from, states that are not in compliance with TANF program requirements.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to HHS to (1) ensure that ACF updates its single audit resolution procedures, (2) ensure that ACF implements a strategy to issue management decisions timely, and (3) develop procedures to timely impose penalties, or alternatively obtain corrective compliance plans. HHS disagreed with the first recommendation; GAO clarified the procedures to be updated. HHS agreed with the second and partially agreed with the third recommendation

What GAO Found

The Single Audit Act requires states and other entities that spend $1 million or more in federal awards each year to undergo a single audit. Single audits can help the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) identify deficiencies in states’ internal controls over financial reporting and over compliance requirements for federal award programs. Auditors report these deficiencies in single audit reports as audit findings.

GAO identified 37 states with, collectively, 162 Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) audit findings in their single audit reports. Fifty-six of these findings were categorized as a material weakness, the most severe category of audit findings. For example, auditors found that one state did not report required information for awards granted to subrecipients. Thirty-seven of the 162 audit findings repeated for 2 or more years, and three remained unresolved for over a decade (see figure). Such findings—especially those categorized as material weaknesses—are considered particularly serious, as they can indicate critical risks and issues in a federal program. Additionally, some of these findings involved deficiencies that could lead to improper payments.

HHS’s Administration for Children and Families (ACF), which administers the TANF block grant funds, has not updated its procedures for determining its effectiveness in helping states resolve TANF single audit findings. Additionally, ACF’s procedures do not ensure that it issues timely management decisions to states. Management decisions are the agency’s written evaluations of whether audit findings are sustained and the expected corrective actions to resolve the findings. Further, HHS does not have sufficient procedures to timely impose penalties on, or alternatively obtain corrective compliance plans from, states in violation of TANF program requirements. Developing effective procedures would better position HHS to help states improve internal controls over TANF federal awards and improve program outcomes.

Abbreviations

|

ACF |

Administration for Children and Families |

|

C.F.R. |

Code of Federal Regulations |

|

FAC |

Federal Audit Clearinghouse |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

SOP |

standard operating procedure |

|

TANF |

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families |

|

Uniform Guidance |

Uniform Administrative

Requirements, Cost |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 4, 2025

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chairman

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

The Honorable Darin LaHood

Chairman

Subcommittee on Work and Welfare

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provides approximately $16.5 billion in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant funds annually to states, territories (Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and Puerto Rico), and the District of Columbia (hereafter referred to as states). Each year, these TANF funds are used to provide millions of low-income individuals and families with children with cash assistance and other services, called non-assistance, to foster economic security and stability. Congress and others have raised questions about the potential misuse of TANF funds. For example, in May 2020 and October 2021, the Mississippi State Auditor announced that multiple individuals affiliated with that state’s TANF program potentially misspent, converted to personal use, or wasted more than $77 million of TANF funds.[1]

The Single Audit Act, as well as the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) implementing Uniform Guidance and related HHS regulations incorporating OMB’s Uniform Guidance, require states, among others, that spend $1 million or more in federal awards (e.g., TANF award funds) each year to undergo a single audit (an audit of an entity’s financial statements and federal awards).[2] After the audit, states are required to submit the single audit reports to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse (FAC).[3] Single audits help ensure that states have adequate internal controls in place over federal programs and are complying with relevant program requirements.

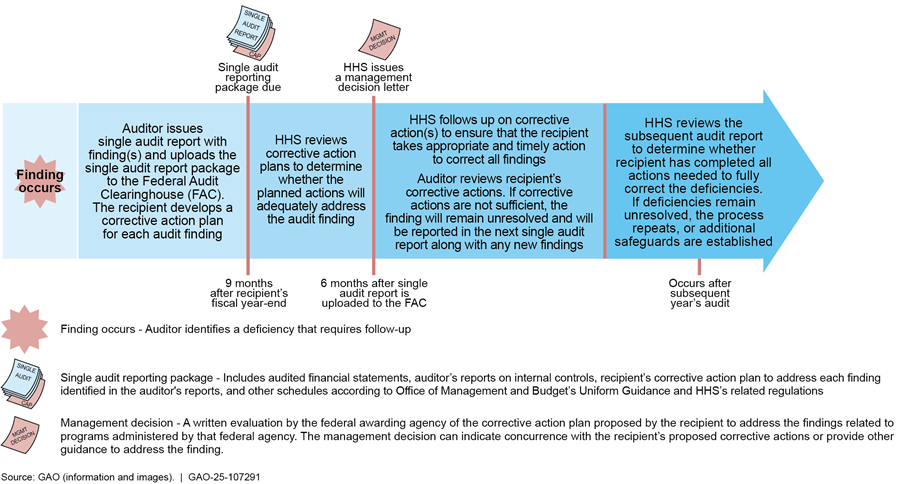

OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations require HHS, as the federal awarding agency for TANF funds, to take certain steps as part of the single audit process. For example, HHS is responsible for

· ensuring that single audits are completed and reports are received in a timely manner;

· issuing management decisions for audit findings, stating whether findings are sustained and specifying expected corrective actions;

· following up on audit findings to ensure that states take appropriate and timely corrective action; and

· developing a baseline, metrics, and targets to track the effectiveness of the process of following up on audit findings.[4]

You asked us to review issues related to TANF single audits.[5] This report examines (1) the timeliness of fiscal year 2023 single audit report submissions and the nature and extent of TANF single audit findings; (2) commonalities among these findings; and (3) the extent to which HHS has conducted oversight of TANF single audits, including following up on findings, issuing management decisions, and imposing penalties on, or alternatively obtaining corrective compliance plans from, states not meeting TANF program requirements.

To address our first objective, we obtained the most recent single audit reports for all states from the FAC database, as of April 30, 2024.[6] We then reviewed the FAC database submissions to identify states with timely fiscal year 2023 single audit reports. We analyzed these reports and identified the number of TANF-related findings, as well as any findings that resulted in a material weakness or significant deficiency, severe findings, repeat findings, and findings with questioned costs.[7] We defined a severe finding from a single audit as one that the auditor determined contributed to (1) a modified opinion on a compliance audit or (2) a material weakness on an internal control over compliance audit.[8]

To address our second objective, we analyzed the TANF findings we identified in our first objective to identify commonalities among reported (1) conditions and causes, (2) compliance requirements, and (3) repeat findings. In addition, we interviewed representatives of the single audit community and included examples of commonalities they reported identifying in single audit findings.[9]

To address our third objective, we interviewed HHS officials to determine how the agency tracks and follows up on TANF single audit findings, as well as whether it exercises its authority under the Social Security Act to impose penalties on or alternatively obtain corrective compliance plans from states. In addition, we reviewed policies, procedures, and related documentation that HHS provided to us on its single audit resolution process.[10] For additional details on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

TANF

States use TANF funds to provide assistance to low-income individuals and families with children in the form of cash (e.g., monthly cash payments to qualifying low-income families), payments made to foster parents, and subsidies for adoption and guardianship.[11] States also use TANF funds to provide other services, called non-assistance, for work, education, and training activities, as well as childcare for parents who are employed. According to our analysis of TANF expenditure data for fiscal year 2022, the most recent fiscal-year data available, states reported spending a total of $13.8 billion on non-assistance expenditures, $7.9 billion on assistance expenditures, and $4.3 billion on expenditures in categories that contain both assistance and non-assistance.[12]

As the federal awarding agency, HHS is responsible for overseeing the use of TANF funds. The Office of Family Assistance, within HHS’s Administration for Children and Families (ACF), administers the TANF block grant funds that are provided annually to states. The Assistant Secretary for Financial Resources, Audit Resolution Division, sets the audit resolution policy for all of HHS and assigns resolution of single audit findings to the applicable operating divisions. HHS operating divisions are primarily responsible for audit findings associated with the programs they administer. TANF audit findings are assigned to the ACF operating division.

Single Audit

Single audits are an important tool federal agencies use to oversee federal awards. Under the Single Audit Act, they must be conducted by an independent auditor, typically either a private firm engaged by the recipient or by a state or local government audit agency.[13]

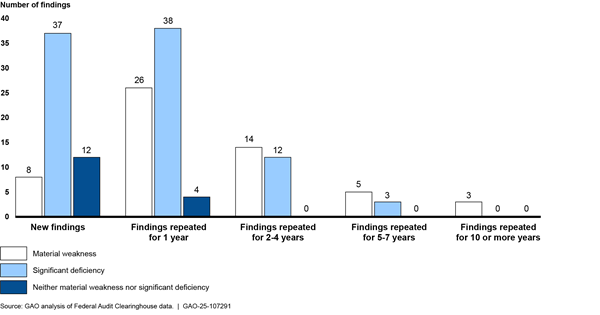

A single audit is an audit of an entity’s financial statements and federal awards for the fiscal year.[14] Single audit reports must include (1) the award recipient’s financial statements and schedule of expenditures of federal awards; (2) when applicable, a status of all prior single audit findings, which were included in the prior single audit report’s schedule of findings and questioned costs for federal awards; (3) the auditor’s opinions on the award recipient’s financial statements and schedule of expenditures of federal awards, compliance with certain federal legal requirements (from laws, regulations, and the terms and conditions of federal awards), and internal control over compliance; (4) when applicable, a schedule of findings and questioned costs; and (5) when applicable, a corrective action plan to address each audit finding. See figure 1 for an example of TANF expenditures that are subject to single audit.

Figure 1: Examples of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Expenditures Subject to Single Audit

Single audits can help HHS identify deficiencies in states’ financial reporting and in their compliance with certain federal legal requirements (from laws, regulations, or the terms and conditions of federal awards) that may have a direct and material effect on each of HHS’s major federal award programs. Such audits can also help the agency identify deficiencies in states’ internal controls over financial reporting and over compliance requirements for federal award programs. Auditors report these deficiencies in single audit reports as audit findings. Auditors must report the following as audit findings:

1. significant deficiencies and material weaknesses in internal control over major programs;

2. material noncompliance with federal statutes, regulations, or the terms and conditions of federal awards related to a major program;[15] and

3. known questioned costs greater than $25,000.[16]

Uniform Guidance and Related Regulations on Single Audits

OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations establish single audit requirements and awarding agency oversight responsibilities for federal awards. The guidance and regulations require auditors to report single audit findings with sufficient detail and clarity. Audit findings must include the following information:[17]

· Federal program and specific federal award identification, known as the assistance listing number.[18]

· Criteria or specific requirement upon which the audit finding is based, including certain federal legal requirements (from laws, regulations, and the terms and conditions of the federal awards). Criteria generally identify the required or desired state or expectation with respect to the program or operation.

· Condition found, including facts that support the deficiency identified in the audit finding.

· Cause that identifies the reason or explanation for the condition or the factors responsible for the difference between the situation that exists (condition) and the required or desired state (criteria), which may also serve as a basis for recommendations for corrective action.

· Effect or potential effect of the finding.

· Questioned costs, which are expenses that an auditor has identified as potentially problematic.

· Identification of whether the audit finding was a repeat of a finding in the immediately prior audit and, if so, any applicable prior-year audit finding numbers.

Auditors refer to guidance in OMB’s annual Compliance Supplement to identify compliance requirements applicable to each federal program in their single audit.[19] The compliance requirements vary for each federal program. Compliance requirements applicable to TANF that were subject to audit in fiscal year 2023 included (1) activities allowed or unallowed and allowable costs/cost principles; (2) eligibility; (3) matching, level of effort, and earmarking; (4) reporting; (5) subrecipient monitoring; and (6) special tests and provisions.[20]

Auditor Opinions

OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations require a single audit report to include an opinion on whether the award recipient’s financial statements are fairly presented, in all material respects, in accordance with the applicable reporting framework. In addition, a single audit report must include a report on compliance for each major program and a report on internal control over compliance. This includes an opinion as to whether the entity complied, in all material respects, with the types of compliance requirements that could have a direct and material effect on each of the major programs selected for the audit.

Opinions can be unmodified or modified. Unmodified opinions are issued when the auditor determines that the recipient complied, in all material respects, with applicable compliance requirements. Modified opinions are issued when the auditor (1) concludes that material noncompliance with applicable compliance requirements exists or (2) is unable to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to conclude if material noncompliance with applicable compliance requirements exists.

Some Single Audit Reports Not Submitted Timely and Indicate Severe and Repeated Findings

Twenty States Did Not Submit Timely 2023 Single Audit Reports to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse

The Single Audit Act and OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations require states to submit single audit reports to the FAC within a designated time frame.[21] Our review of the 50 states and the District of Columbia’s single audit reports found that 20 states did not timely submit their 2023 single audit reports to the FAC. Specifically, as of January 15, 2025,15 states had submitted their fiscal year 2023 single audit reports after the required due date, and five states had not yet submitted their fiscal year 2023 reports.

Many TANF Audit Findings Were Severe

Audit Findings

In our review of the most recent state single audit reports, we identified 37 states with 162 TANF findings collectively as of April 30, 2024.[22] Of these 37 states, 22 had at least one finding categorized as a material weakness, the most severe category of audit finding (see table 1).

Table 1: Number of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Single Audit Findings by Category and Number of States

|

Finding category |

Number of findings |

Number of states |

|

Material weakness |

56 |

22 |

|

Significant deficiency |

90 |

29 |

|

Other matter |

16 |

7 |

|

Total |

162 |

37a |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Audit Clearinghouse data. | GAO‑25‑107291

aOur analysis found only 37 states had audit findings in the TANF program in their most recently available single audit reports, as of April 30, 2024. States may have multiple findings in the same single audit report.

These 22 states had a total of 56 TANF findings categorized as material weaknesses in their single audit reports. Examples of these audit findings included:

· Insufficient documentation. The state did not obtain or maintain sufficient documentation to support beneficiary eligibility for TANF-funded assistance payments. As a result, the auditor noted that the state may have made payments to ineligible beneficiaries.

· Inadequate internal controls. The state lacked adequate internal controls for ensuring accurate reporting on statutorily required quarterly TANF data forms.[23] HHS uses these forms to determine whether the state met the statutory minimum work participation requirements for the TANF program.

· Failure to report subrecipient information. One state failed to report information required by the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006[24] for subawards granted to subrecipients of the TANF program, resulting in noncompliance with federal requirements.[25]

Additionally, 90 of the findings resulted in a significant deficiency, a less-severe finding than a material weakness, but one that requires attention from those charged with governance. In one instance, the auditor found cases in which no income eligibility and verification system documentation was present in the electronic case record or case notes.

The remaining 16 findings were not categorized as material weaknesses or significant deficiencies.

Audit Opinions on Compliance

We identified 20 states for which the auditor issued a modified opinion on the state’s compliance with TANF program requirements.

The auditors for 17 states did not identify TANF as a major program; therefore, no audit opinion was issued on the program (see app. II). The remaining 14 states’ auditors issued unmodified opinions, meaning the auditors determined that recipients complied, in all material respects, with applicable compliance requirements.

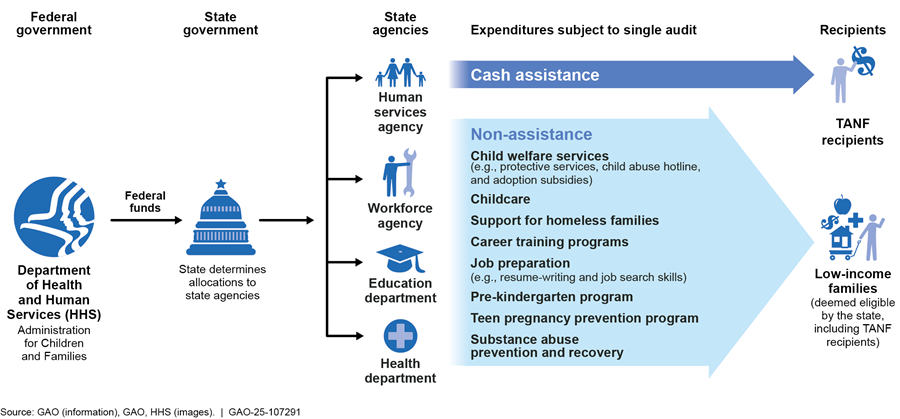

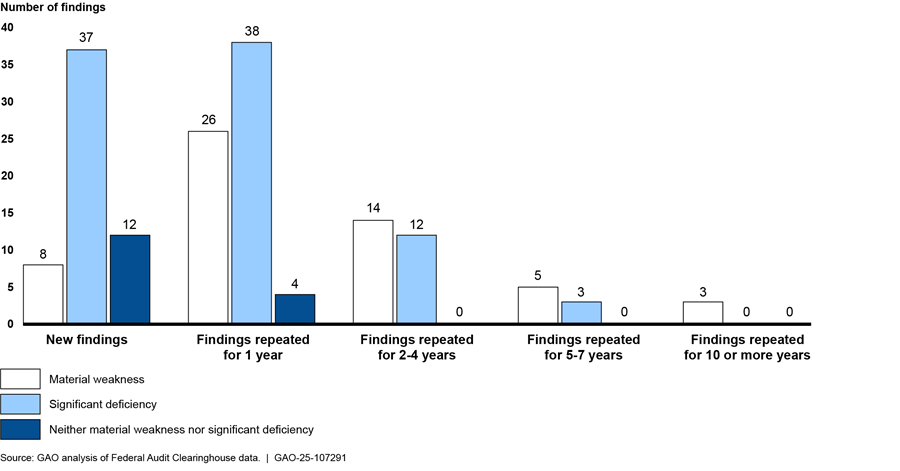

The Majority of Severe Findings Were Repeat Findings

One hundred five of the 162 audit findings have repeated for at least 1 year. Thirty-seven findings repeated for 2 or more years, and three remained unresolved for over a decade. A repeat finding is one that is the same as, or substantially similar to, a finding in a previous audit, for which the recipient did not take planned corrective action or the action it took was ineffective. Repeat findings—especially those categorized as material weaknesses—are considered particularly serious as they can indicate continuing critical risks and issues in a federal program.

Forty-eight of the 56 TANF findings categorized as material weaknesses are repeat findings, three of which have repeated for over a decade. Additionally, 15 of the 90 significant deficiencies have repeated for 2 or more years. Figure 2 displays the number of repeat findings categorized by severity.

Figure 2: Number and Duration of Repeated Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Single Audit Findings, as of April 30, 2024

Even though states must initiate and proceed with corrective actions on TANF audit findings as rapidly as possible and corrective action should begin no later than upon receipt of the audit report, states may not resolve findings in 1 year. This can result from the time allowed for states to submit their audit reports to the FAC and for federal awarding agencies, such as HHS, to issue management decisions on a state’s corrective action plan. Under the time frames provided by the Single Audit Act, as well as OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations, states are required to submit to the FAC their single audit reports and corrective action plans within 9 months of their fiscal year-end. HHS must issue management decisions in response to the audit findings within 6 months of the FAC’s acceptance of states’ single audit reports. As a result, a single audit finding from one year may remain open in the next, potentially explaining the high number of findings that repeated for 1 year.

Among the repeat TANF findings, we identified one that has repeated for 15 years and another that has done so for 13 years, both from the same state. These two findings relate to long-standing internal control deficiencies that could lead to payments to ineligible applicants, for the wrong amount, or for an improper length of time. Additionally, one state had five material weakness findings that repeated for at least 4 years. Four of these were related to insufficient internal controls over compliance with TANF requirements, increasing the risk that the state’s TANF program will be ineffectively and inefficiently administered.

Several Audit Findings Involved Questioned Costs

We found that 36 of the 162 TANF findings involved questioned costs. One of the questioned cost amounts was nearly $1.3 million. In this case, the auditor found that the state did not document completion of eligibility checks prior to issuing the payment.[26] The other questioned cost amounts ranged from $99 to $179,074, with an average of $22,542 and a median of $6,548.

TANF Single Audit Findings Share Commonalities in Condition, Cause, and Compliance Issues

Commonalities in Condition and Cause

The 162 TANF findings shared some common conditions and causes, as reported by state auditors. Specifically, we found that internal control deficiencies were the most reported condition and cause.[27] Other commonalities among findings involved issues such as inaccurate data, lack of reporting,[28] and insufficient documentation, among others (see table 2). The audit community has identified similar commonalities, according to representatives we spoke with.

Table 2: Examples of Findings in Common Conditions or Causes for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Findings from Most Recent Single Audit Reports, as of April 30, 2024

|

Condition or cause |

Finding example(s) |

|

Internal control deficiencies |

The state did not follow the federally approved plan to allocate costs among state and federal programs. Internal controls failed to identify inconsistencies. |

|

Insufficient documentation |

The state had policies and procedures in place regarding the issuance and removal of sanctions; however, adequate documentation to determine that the controls were operating effectively was not consistently maintained or available. |

|

Inaccurate data |

The state reported inaccurate data due to errors related to the implementation of a new case file system. |

|

Special tests and provisions |

The state did not achieve its two-parent work participation rate for the fiscal year, which is required by the Social Security Act and HHS’s implementing TANF regulations.a |

|

Reporting |

The state failed to report subaward information required by the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006.b |

|

Eligibility |

The state did not comply with beneficiary eligibility requirements for childcare services paid with grants from the Child Care and Development Fund and TANF funds due to inadequate internal controls.c |

|

Insufficient procedures or lack of procedures to review or monitor activities |

The state did not have adequate procedures for monitoring subrecipient financial records. The state did not perform procedures reviewing subrecipient financial records. |

|

Lack of staff or frequent staff turnover |

The state could not provide an explanation as to why the ACF-204 annual report was incomplete due to staff turnover. |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Audit Clearinghouse data. | GAO‑25‑107291

aEach state must achieve a 90 percent minimum two-parent participation rate minus any caseload reduction credit to which it is entitled. See 42 U.S.C. 607; 45 C.F.R. 261.23.

bThis act requires information on federal awards, including subawards, be made available to the public on a single searchable website (currently, USAspending.gov). Pub. L. No. 109-282, 120 Stat. 1186 (Sept. 26, 2006), reprinted in 31 U.S.C. 6101 note. A subaward is an award provided by a pass-through entity, such as a state, to a subrecipient, such as a nonprofit organization, to carry out part of a federal award received by the pass-through entity. 2 C.F.R. 200.1; 45 C.F.R. 75.2.

cThe Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) refers to the childcare programs conducted under the provisions of the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act, as amended, which is codified at 42 U.S.C. 9857-9858r. The CCDF consists of discretionary funds authorized under 42 U.S.C. 9858 and mandatory and matching TANF funds appropriated under 42 U.S.C. 618. See 45 C.F.R. 98.2.

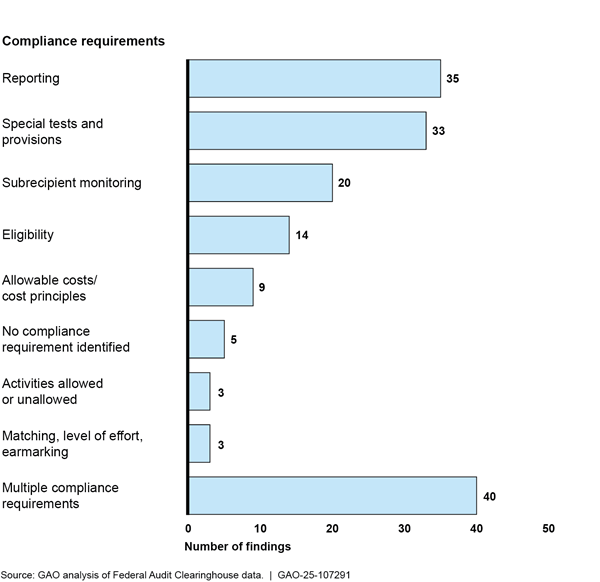

Commonalities in Compliance Requirements

For the 162 TANF single audit findings, we found that most of the audit findings were related to three compliance requirements: reporting (35 findings), special tests and provisions (33 findings), and subrecipient monitoring (20 findings). More than one compliance requirement may be associated with one audit finding. We identified 40 audit findings that were related to more than one compliance requirement. The number of audit findings grouped by compliance requirement are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: Number of Audit Findings Related to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Compliance Requirements from Most Recent Single Audit Reports, as of April 30, 2024

Note: Single audit report findings that did not list a compliance requirement in the finding were categorized as no compliance area identified.

Commonalities in Compliance Requirements for Repeat Findings

As noted earlier, 105 of the 162 TANF audit findings repeated for at least 1 year—some recurring for as many as 10 years. We found that most of the repeat findings were related to three compliance requirements: special tests and provisions (25 findings), reporting (18 findings), and subrecipient monitoring (13 findings). For example, one repeat finding, which has reoccurred for 13 years, related to inadequate documentation for determining whether the internal controls for the issuance and removal of sanctions were operating effectively.

A representative of the audit community that we interviewed also identified commonalities in repeat findings, which overlap with our results. For example, the representative stated that there are two common themes associated with TANF single audit findings dating as far back as 2014: (1) eligibility (i.e., beneficiaries receiving TANF funds that may not meet eligibility requirements) and (2) lack of internal controls to ensure that expenditures charged to the TANF program by a state health and human services agency are in fact charged to the program and in the accurate amount.

HHS Has Not Implemented Procedures to Conduct Effective Oversight of TANF Single Audit Findings

We found that ACF’s single audit resolution standard operating procedures (SOP), dated November 2021, did not include steps to track and measure the effectiveness of its actions to help states resolve TANF single audit findings.[29] Further, management decisions, stating whether findings are sustained by HHS and, if necessary, specifying expected corrective actions, were not always issued timely to states. Finally, HHS lacked procedures to ensure that it imposed penalties timely on, or alternatively obtained corrective compliance plans from, states not meeting TANF program requirements.

ACF’s Procedures Do Not Measure Its Effectiveness in Helping States Resolve TANF Single Audit Findings

We found that ACF’s SOP does not have sufficient procedures to help ACF determine the effectiveness of its single audit resolution process. Specifically, its SOP lacks steps to track and measure the effectiveness of its actions to help states resolve TANF single audit findings. ACF officials stated that if a management decision is documented and issued to the recipient, the agency records the finding as closed in its internal Audit Tracking and Analysis System. However, this closed status does not necessarily indicate that the recipient addressed or took all necessary corrective actions within a reasonable amount of time to resolve the audit finding.

We found that many states have single audit TANF findings that repeated for 2 or more years and that some findings remained unresolved for over a decade. ACF officials stated that the agency does not have an established time requirement for recipients to resolve TANF single audit findings.

ACF has not implemented HHS’s procedures nor updated its own SOP to include steps to track and measure the effectiveness of its actions to help states resolve TANF single audit findings. ACF officials stated that ACF retains the discretion to not implement HHS’s SOP.

HHS’s SOP, which is designed to promote standardization, was issued in September 2019 for department-wide use and directs agencies to use a resolution process to determine whether corrective action plans have been implemented and deficiencies have been corrected. HHS’s SOP further states that successful single audit resolution should result in a reduction in repeat audit findings. HHS revised its SOP in October 2024 to include procedures for determining the effectiveness of its resolution process at least annually. OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations require HHS to follow up on audit findings to ensure that TANF fund recipients take timely and appropriate action to correct deficiencies identified through the single audit process. OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations also require HHS to develop a baseline, metrics, and targets to track, over time, the effectiveness of the HHS’s process to follow up on single audit findings. HHS can use these metrics in making award decisions as well as in determining the effectiveness of single audits in improving award recipients’ accountability.

Figure 4 depicts HHS’s procedures for following up on single audit findings for the period covered under our review. These procedures were generally aligned with OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations.

Figure 4: Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Procedures for Single Audit Findings Follow-up

Tracking and measuring the effectiveness of its single audit resolution actions could help ACF identify repeat single audit issues and determine the effects of deficiencies on the TANF program, such as a lack of internal controls, that could lead to improper payments. Without updating its procedures to do so, ACF increases the risk that (1) it will not follow up on findings, (2) corrective actions to fix weaknesses in a state’s internal controls will not be implemented timely, and (3) program outcomes may not align with the program’s purposes.

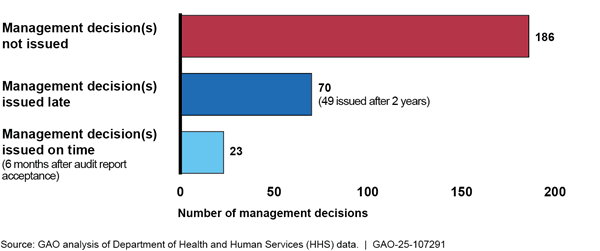

ACF’s Procedures Do Not Help Ensure Timely Issuance of Management Decisions to States

We found that 23 (approximately 8 percent) of the 279 management decisions related to TANF for state fiscal years 2018 through 2023 were issued within 6 months of the audit report’s FAC acceptance as required by OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations. In its Audit Tracking and Analysis System, ACF indicated that 70 management decisions were not issued within the required 6-month time frame. For example, ACF’s records show that the management decision for one state with four findings was issued 4 years past the due date. In addition, ACF has not issued management decisions for 186 findings as of April 2024.[30] Issuing late management decisions to the award recipients may result in delayed initiation of corrective actions and may result in repeat findings in subsequent year single audits.

In February 2017, we recommended that HHS revise its policies and procedures to reasonably assure that management decisions contain the required elements and are issued timely in accordance with OMB’s Uniform Guidance.[31] In response to our recommendation, HHS revised its SOP, dated September 2019, to include procedures for issuing management decisions within 6 months of acceptance of the audit report by the FAC, in accordance with OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s implementing regulations.[32]

The revised HHS SOP also includes procedures for quality control reviews of management decisions. Specifically, HHS’s Office of Program Audit Coordination is tasked with completing quality control reviews to verify that HHS’s management decisions are issued timely and include the required elements. However, despite these 2019 revisions to HHS’s SOP, ACF continued to issue late management decisions for TANF findings (see fig. 5). ACF stated that it has the discretion to not adhere to HHS’s SOP. Choosing not to adhere to HHS’s SOP may result in delays in the issuance of management decisions.

HHS officials stated that the delays in issuing management decisions are a result of internal staff capacity, awaiting the outcome of criminal or civil investigations, and having complex findings that require consulting with other program offices. HHS further stated that a TANF audit backlog had accumulated during the COVID-19 pandemic and post pandemic period while agency staff were fully engaged in helping grant recipients respond to the public health crisis. HHS officials said they are now working to eliminate that backlog.

Figure 5: Timeliness of HHS’s Issuance of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Management Decisions for Fiscal Years 2018 through 2023, as of April 2024

Developing and implementing a strategy to eliminate the accumulated TANF audit backlog would help strengthen ACF’s compliance with OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations. It would also help improve ACF’s oversight of states to ensure that TANF audit findings are timely corrected. Additionally, timely issuance of management decisions would help reduce the risk that states will misunderstand HHS ACF’s position on their TANF audit findings and fail to implement appropriate corrective actions.

HHS Does Not Have Sufficient Procedures to Impose Enforcement Mechanisms on States Not Meeting TANF Requirements

HHS has established enforcement mechanisms such as imposing penalties on, or alternatively obtaining corrective compliance plans from, states when they are in violation of the Social Security Act. However, based on our review of single audit reports, we identified instances in which HHS could have imposed a penalty or alternatively obtained a corrective compliance plan from a state but did not. Further, HHS did not provide documentation during the course of our engagement of its determination not to impose a penalty.

The Social Security Act authorizes HHS to impose penalties on states, or alternatively obtain corrective compliance plans from them. According to the act, HHS can impose penalties on states for multiple reasons related to not meeting TANF program requirements, including (1) failure to satisfy minimum participation rates, (2) failure to comply with the 60-month limit on assistance, (3) failure to timely submit quarterly reports, and (4) paying amounts that are in violation of the act.[33]

HHS officials said that the Social Security Act subjects a state to a potential penalty if it fails to meet certain statutory requirements. HHS officials stated that the agency evaluates each single audit finding to determine whether it is appropriate to impose a penalty under the Social Security Act. They further explained that, before any penalty is imposed on the state, the state has the option to alternatively submit a corrective compliance plan to correct the failure.[34] HHS officials stated that if a recipient develops a corrective compliance plan, HHS will not impose a penalty pending the outcome of the corrective compliance plan.

HHS established some steps in its SOP to determine whether it is appropriate to impose a penalty by suspending or terminating a TANF award amount. However, these procedures do not include time frames for issuing or enforcing penalties, and as such, are not effective for ensuring that penalties are imposed timely or are imposed at all. In addition, HHS did not have written procedures for determining whether a corrective compliance plan should be obtained from states, nor did it have procedures for documenting support for its determinations. HHS could not provide an explanation for why the agency does not have such procedures.

In accordance with HHS’s TANF regulations, if HHS determines that a state did not achieve one of the required work participation rates, then HHS must reduce the amount of the grant to the state.[35] However, we found that HHS’s Office of Family Assistance reported that eight states and one territory did not meet their fiscal year 2022 statutory requirements for TANF work participation rates, but did not impose a penalty.[36]

In one instance, auditors reported that a state did not achieve its TANF work participation rate in the fiscal years 2022 and 2023 single audit reports; the penalties associated with these findings were $19.7 million and $800,000, respectively. HHS provided evidence that it sent notices of penalties in March 2025, and ACF officials stated that they are in varying stages of assessing penalties. However, ACF did not provide evidence that ACF imposed the penalties or provide documentation of its determination not to impose a penalty in response to our request.

In another single audit report, auditors found that two families received TANF benefits for longer than the 60 months allowed by the Social Security Act.[37] HHS did not provide any evidence that the state was penalized or alternatively entered a corrective compliance plan. As a result, HHS may be missing opportunities to encourage states to remove recipients who are no longer eligible to receive benefits, which could help reduce overpayments.

Additionally, we found that when HHS imposed penalties, they were late. Specifically, based on our review of HHS’s listing of penalties imposed from fiscal year 2016 to fiscal year 2023, we found that HHS was late in imposing penalties for all 11 documented violations.[38] The late penalties totaled $10.4 million.

Federal internal control standards state that management should implement control activities through policies. As such, management is responsible for designing the policies and procedures to enable the entity to comply with laws and regulations. Further, the standards require documentation as a necessary part of an effective internal control system.[39]

By establishing and documenting specific procedures for imposing penalties on states or alternatively obtaining corrective compliance plans from states that are not meeting TANF program requirements, HHS can enhance its oversight. This includes encouraging states to resolve audit findings in a timely manner; comply with certain federal legal requirements (from laws, regulations, and the terms and conditions of federal awards); and reduce the likelihood of improper payments.

Conclusions

TANF provides billions of dollars annually to states to help low-income individuals and families with children. States have a responsibility to ensure they have adequate internal controls in place over federal programs and are complying with relevant program requirements. States that receive substantial amounts of TANF funds require auditors to review their compliance with laws and regulations and report findings in single audit reports. HHS must also do its part to ensure accountability for these funds, including following up on single audit findings, issuing management decisions, and monitoring recipients’ corrective actions.

Recent single audit reports indicate that many states have single audit findings that repeated for 2 or more years and some findings that remained unresolved for over a decade. The majority of these repeat findings were categorized as severe. HHS has recently revised its procedures to help determine its effectiveness in helping states resolve these findings. However, ACF has not implemented these procedures or updated its own SOP to include effectiveness determinations. Until ACF revises and implements its procedures, it will not be able to assess how well it is helping states timely resolve their single audit findings. Doing so will also help ACF ensure that states timely identify and correct weaknesses in their TANF program internal controls. Such steps would provide greater assurance that TANF funds are used properly.

HHS’s SOP has procedures to timely review single audit findings and issue management decisions on the adequacy of states’ corrective action plans to address single audit findings. However, ACF has not issued timely management decisions for findings related to the use of TANF funds. Until ACF takes steps to develop and implement a strategy to eliminate the accumulated TANF audit backlog to ensure that management decisions are issued within the required time frame, there is increased risk that audit findings will not be corrected timely and that states will misunderstand ACF’s position on the audit findings and fail to implement appropriate corrective actions.

Imposing penalties or alternatively obtaining corrective compliance plans are effective mechanisms for encouraging states to meet TANF program requirements. HHS has established processes to carry out these enforcement mechanisms but does not have written procedures for timely determining whether to impose penalties or alternatively obtain corrective compliance plans from states in violation of TANF program requirements. Having these procedures would help ensure that HHS complies with federal legal requirements and improves its oversight of federal awards. Additionally, until HHS establishes such procedures, it may be missing opportunities to help states improve internal controls over TANF funds and improve program outcomes.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to HHS:

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Administration for Children and Families revises and implements its audit resolution standard operating procedures (dated November 2021) to include steps to track and measure the effectiveness of actions to help states resolve TANF single audit findings. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should ensure that the Administration for Children and Families develops and implements a strategy to eliminate the accumulated TANF audit backlog, to ensure that management decisions are issued within the required time frame. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Health and Human Services should develop, document, and implement additional procedures to timely impose penalties or alternatively obtain corrective compliance plans for states that are not meeting TANF program requirements. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix III and summarized below, HHS did not concur with the draft report’s first recommendation, concurred with the second, and partially concurred with the third. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

HHS disagreed with recommendation 1 in our draft report, which stated that HHS should ensure that it implements HHS’s revised SOP (dated October 2024) to track and measure the effectiveness of actions to help states resolve TANF single audit findings. ACF officials stated that the recommendation pertained to HHS’s SOP, which was not written by ACF, and that implementing such procedures is at ACF’s discretion.

After receiving our draft report, ACF provided its own single audit resolution SOP. We modified the recommendation and report to clarify that ACF, rather than HHS, should revise and implement its audit resolution SOP. Until ACF’s procedures are revised and implemented, ACF will not be able to determine how effective its processes are in helping to resolve findings and make any necessary adjustments for improvements. As a result, ACF will continue to face risks that corrective actions to fix weaknesses in a state’s internal controls will not be implemented effectively or timely.

HHS concurred with the draft report’s recommendation 2 and cited actions that it has taken or will take to address it. HHS recommended a modification to the recommendation, specifying that the backlog relates specifically to TANF findings. We agree and modified the recommendation and report to reflect TANF findings. The actions that HHS described, if implemented effectively, would address recommendation 2.

HHS partially agreed with the draft report’s recommendation 3. In its written comments, HHS stated that it concurs with the recommendation to develop and implement additional procedures to timelier evaluate whether to impose penalties that do not relate to TANF work participation rates. ACF provided evidence that penalty amounts related to work participation rate requirements are calculated and notices are sent to states.

However, HHS disagreed with a portion of the draft report’s recommendation 3, which recommended that HHS document its determinations of whether to impose penalties for states that are not meeting TANF program requirements. Specifically, HHS stated that the penalty determination process is documented in penalty notifications letters sent to the states. HHS provided evidence, which we reviewed, that it documented its decisions related to imposing penalties. However, HHS does not have written procedures to do so timely. As a result, we have modified the recommendation and report to include written procedures to document decisions to impose penalties in a timely manner. Having documented procedures would help ensure that HHS complies with federal legal requirements and improves its oversight of federal awards.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at dalkinj@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

James R. Dalkin

Director

Financial Management and Assurance

This report examines the (1) the timeliness of fiscal year 2023 single audit report submissions and the nature and extent of TANF single audit findings; (2) commonalities among these findings; and (3) the extent to which the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has conducted oversight of TANF single audits, including following up on findings, issuing management decisions, and imposing penalties on, or alternatively obtaining corrective compliance plans from, states not meeting TANF program requirements.[40]

To address all three of our objectives, we obtained the most recent single audit reports for all states and the District of Columbia (51 total reports), as of April 30, 2024, from the Federal Audit Clearinghouse (FAC).

For our first objective, we determined the timeliness of states’ fiscal year 2023 single audit report submissions to the FAC as of January 15, 2025. We then reviewed the most recent single audit reports as of April 30, 2024, to identify the number of TANF-related findings that were new, repeated more than 1 year, resulted in a material weakness or a significant deficiency, or involved questioned costs, as reported by the auditors. We also reviewed the TANF program audit opinion on each report.

To address our second objective, we analyzed the TANF findings identified in our first objective to identify commonalities among reported (1) conditions and causes, (2) compliance requirements, and (3) repeat findings. To verify commonalities identified, we used a text analytics method to efficiently locate key terms for both the condition and cause of the findings. We identified and summarized unmet compliance requirements for each finding. Finally, we identified and summarized the repeat findings according to the related compliance requirements. In addition, we interviewed representatives of the single audit community and summarized commonalities they identified in single audit findings.[41]

For our third objective, we reviewed federal awarding agency single audit requirements in the Single Audit Act, as well as the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (Uniform Guidance) and HHS’s related regulations, to determine the requirements for HHS management of TANF single audit findings.[42]

Additionally, we reviewed federal internal control standards and determined that the following components and underlying principles of internal control were significant to objective three:[43]

· Control environment. Management should establish an organizational structure, assign responsibility, and delegate authority to achieve the entity’s objectives, and evaluate performance and hold individuals accountable for their internal control responsibilities.

· Control activities. Management should design control activities to achieve objectives and respond to risks. Management should implement control activities through policies.

We assessed HHS’s policies and procedures against the Single Audit Act, as well as OMB’s Uniform Guidance, HHS’s related single audit regulations, and federal internal control standards, to determine the extent to which HHS conducted appropriate oversight using single audit reports.

Further, to determine HHS’s compliance with OMB’s Uniform Guidance and its own related regulations, which require that management decisions be issued within 6 months, we reviewed a list of findings that HHS provided for state single audit reports issued in fiscal years 2018 through 2023. We compared the dates of each management decision to the date of the single audit reporting package to determine whether it was within the required 6-month time frame.

To determine how HHS tracks and follows up on TANF single audit findings, we interviewed officials from several of the agency’s operating divisions, including Grants Management, the Office of Family Assistance, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Financial Resources Audit Resolution Division, and the Administration for Children and Families. We also inquired whether HHS has imposed any penalties on or alternatively obtained corrective compliance plans from states that did not meet TANF program requirements.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Appendix II: Single Audit Reports Reviewed and Compliance Opinions on the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Program

In this report, we reviewed the most recently available state single audit reports, as of April 30, 2024. Specifically, we analyzed 34 fiscal year 2023 reports, 15 fiscal year 2022 reports, and two fiscal year 2021 reports to determine if they included Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) audit findings. In those reports, we reviewed the auditor’s Report on Compliance for Each Major Federal Program. We identified 20 states for which the auditor issued a modified opinion on the state’s compliance with TANF program requirements and 14 states for which the auditor issued an unmodified opinion. We also identified 17 states for which the auditor did not identify TANF as a major program and consequently did not issue a TANF audit opinion (see table 3).[44]

Table 3: Single Audit Reports Reviewed and Compliance Opinions on the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Program, as of April 30, 2024

|

State |

Most recent single audit |

Auditor’s opinion on report on compliance for TANF programa |

|

Arkansas |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Colorado |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

Connecticut |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

Delaware |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Florida |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Georgia |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Hawaii |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Idaho |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Indiana |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Iowa |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

Kansas |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Kentucky |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

Louisiana |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Maine |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Maryland |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

Minnesota |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Nebraska |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

New Hampshire |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

New Jersey |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

New Mexico |

2023 |

N/A |

|

New York |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

North Carolina |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Ohio |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Oregon |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Pennsylvania |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Rhode Island |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

South Carolina |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

Tennessee |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Texas |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

Utah |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Vermont |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Virginia |

2023 |

Qualified |

|

West Virginia |

2023 |

Unmodified |

|

Wisconsin |

2023 |

N/A |

|

Alabama |

2022 |

N/A |

|

Alaska |

2022 |

Qualified |

|

Arizona |

2022 |

Unmodified |

|

District of Columbia |

2022 |

Adverse |

|

Illinois |

2022 |

Qualified |

|

Massachusetts |

2022 |

N/A |

|

Michigan |

2022 |

Qualified |

|

Mississippi |

2022 |

Qualified |

|

Missouri |

2022 |

Unmodified |

|

Nevada |

2022 |

N/A |

|

North Dakota |

2022 |

N/A |

|

Oklahoma |

2022 |

Qualified |

|

South Dakota |

2022 |

N/A |

|

Washington |

2022 |

Qualified |

|

Wyoming |

2022 |

Unmodified |

|

California |

2021 |

N/A |

|

Montana |

2021 |

Qualified |

N/A: TANF was not identified as a major program by the auditor; therefore, no audit opinion was issued on the program.

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Audit Clearinghouse data. | GAO‑25‑107291

aOpinions can be unmodified or modified. Unmodified opinions are issued when the auditor determines that the recipient complied, in all material respects, with applicable compliance requirements. Modified opinions are issued when the auditor (1) concludes that material noncompliance with applicable compliance requirements exists or (2) is unable to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to conclude if material noncompliance with applicable compliance requirements exists. The categories of modified opinions are qualified, adverse, and disclaimer.

GAO Contact

James R. Dalkin, dalkinj@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Michelle Philpott (Assistant Director), Melanie Darnell (Auditor in Charge), Seth Brewington, Teressa Gardner, Zachary Kinger, Vivian Ly, Kimberly Maire, and Matthew Valenta made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Mississippi Office of the State Auditor, Press Releases (May 4, 2020; Oct. 12, 2021).

[2]The Single Audit Act is codified at 31 U.S.C. §§ 7501-06, and implementing OMB guidance is published as part of the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards (Uniform Guidance), reprinted in 2 C.F.R. part 200 subpart F. HHS has adopted the text of the Uniform Guidance, with some HHS-specific amendments, in its related regulations incorporating the Uniform Guidance. See 45 C.F.R. pt. 75. In April 2024, OMB issued revisions to the Uniform Guidance, including 2 C.F.R. § 200.501 (which HHS adopted in its regulations), raising the threshold of annual expenditures triggering a single audit (or in limited circumstances, a program-specific audit) from $750,000 (the amount applicable during our audit period) to $1 million, effective for federal awards issued beginning October 1, 2024. 89 Fed. Reg. 30046 (Apr. 22, 2024). In October 2024, HHS issued an interim rule making changes to its Uniform Guidance regulations, which are effective on October 1, 2025, except where expressly stated otherwise, such as for the expenditure threshold. 89 Fed. Reg. 80055 (Oct. 2, 2024).

[3]The FAC serves as a repository and database of single audit reports and information obtained from the data collection forms that federal award recipients and their auditors are required to submit.

[4]2 C.F.R. § 200.513(c); 45 C.F.R. § 75.513(c).

[5]This report is one of several recent and ongoing GAO reviews covering various aspects of TANF. See GAO, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Enhanced Reporting Could Improve HHS Oversight of State Spending, GAO-25-107235 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 13, 2025), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen Fraud Risk Management, GAO-25-107290 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 28, 2025), and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: HHS Could Facilitate Information Sharing to Improve States’ Use of Data on Job Training and Other Services, GAO-25-107226 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 24, 2025). In other ongoing work, we are reviewing HHS’s child welfare spending under TANF. We anticipate issuing the report on the results of this ongoing work in 2025.

[6]For our analysis, we reviewed 35 fiscal year 2023 single audit reports: 14 for fiscal year 2022 and two for fiscal year 2021.

[7]A material weakness is a deficiency in internal control over compliance that indicates a reasonable possibility that material noncompliance with a federal program compliance requirement will not be prevented, or detected and corrected, on a timely basis. A significant deficiency is a deficiency in internal control that is less severe than a material weakness, yet important enough to merit attention by those charged with governance. Under HHS’s regulations incorporating OMB’s Uniform Guidance, a questioned cost is a cost that is questioned by the auditor because (1) an audit finding resulted in a violation or possible violation of statutes, regulations, or the terms and conditions of the federal award; (2) the costs, at the time of the audit, were not supported by adequate documentation; or (3) the costs incurred appeared unreasonable and did not reflect the actions a prudent person would take in the circumstances. 45 C.F.R. § 75.2.

[8]A modified opinion is reported when an auditor (1) concludes that material noncompliance with applicable compliance requirements exists or (2) is unable to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to conclude whether material noncompliance with applicable compliance requirements exists. The categories of modified opinions are qualified, adverse, and disclaimer.

[9]To obtain the views of the single audit community, we spoke with representatives of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants; the Association of Local Government Auditors; and the National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers, and Treasurers.

[10]The single audit resolution process is how federal awarding agencies determine whether a recipient’s planned corrective action, if properly implemented, will correct the condition identified in the audit finding.

[11]HHS’s TANF regulations define “assistance” to include cash, payments, vouchers, and other forms of benefits designed to meet a family’s ongoing basic needs, such as food, clothing, and shelter. It also includes certain supportive services, such as transportation and childcare provided to parents who are not employed. 45 C.F.R. § 260.31.

[12]GAO‑24‑107798. In addition to providing services, TANF funds can be transferred for use under two other HHS block grants. The total amount transferred to these block grants cannot exceed 30 percent of the state’s annual federal TANF award amount. Transferred funds are subject to the rules of the program to which they are transferred, subject to statutory limitations.

[13]31 U.S.C. §§ 7501(a)(8), 7502(c).

[14]31 U.S.C. § 7501(a)(18). In limited circumstances, an award recipient may elect a program-specific audit in lieu of a single audit. 31 U.S.C. § 7502(a); 2 C.F.R. § 200.501(a)-(d); 45 C.F.R. § 75.501(a)-(c).

[15]A major program is determined using a risk-based approach. The risk-based approach must consider current and prior audit experience, oversight by federal agencies and pass-through entities, and the inherent risk of the federal program. 2 C.F.R. § 200.518; 45 C.F.R. § 75.518.

[16]2 C.F.R. § 200.516(a); 45 C.F.R. § 75.516(a).

[17]2 C.F.R. § 200.516(b); 45 C.F.R. § 75.516(b).

[18]Audit findings must identify the federal program and specific federal award, including the assistance listing number and title, federal award identification number and year, name of the federal agency, and name of the applicable pass-through entity. 2 C.F.R. § 200.516(b); 45 C.F.R. § 75.516(b).

[19]The Compliance Supplement is an annually updated authoritative source for auditors that identifies existing important compliance requirements that the federal government expects to be considered as part of a single audit. Auditors use it to understand the federal program’s objectives, procedures, and compliance requirements, as well as audit objectives and suggested audit procedures for determining compliance with the relevant federal program. 2 C.F.R. § 200.1.

[20]The Compliance Supplement treats “activities allowed or unallowed” and “allowable costs/cost principles” as one requirement. 2 C.F.R. pt. 200, app. XI.

[21]2 C.F.R. §§ 200.507(c)(1), 200.512(a)(1); 45 C.F.R. §§ 75.507(c)(1), 75.512(a)(1). According to OMB’s Uniform Guidance and HHS’s related regulations, the audit must be completed and submitted within the earlier of 30 calendar days after receipt of the auditor's report(s) or 9 months after the end of the audit period (unless a different period is specified in an audit guide for a program-specific audit). If the due date falls on a weekend or federal holiday, then the reporting package is due the next business day.

[22]Our analysis included TANF findings from 26 fiscal year 2023 reports, 10 for fiscal year 2022, and one for fiscal year 2021.

[23]42 U.S.C. § 611(a).

[24]FFATA requires information on federal awards, including subawards, be made available to the public on a single searchable website (currently, USAspending.gov). Pub. L. No. 109-282, 120 Stat. 1186 (Sept. 26, 2006), reprinted in 31 U.S.C. § 6101 note. A subaward is an award provided by a pass-through entity, such as a state, to a subrecipient, such as a nonprofit organization, to carry out part of a federal award received by the pass-through entity. 2 C.F.R. § 200.1; 45 C.F.R. § 75.2.

[25]A subrecipient is an entity that receives a subaward from a pass-through entity to carry out part of a federal award. A subrecipient may also be a recipient of other federal awards received directly from a federal awarding agency. An individual who is a beneficiary of such an award is not considered a subrecipient. 2 C.F.R. § 200.1; 45 C.F.R. § 75.2.

[26]HHS has not issued a management decision during our audit period; therefore, we are uncertain if HHS sustained the questioned costs.

[27]An internal control deficiency exists when there is an issue with controls that requires further evaluation and remediation. See GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014).

[28]In January 2025, GAO issued a report reviewing HHS oversight of TANF and made two recommendations related to reporting oversight. GAO recommended that HHS design control activities to help ensure that states are submitting complete narrative data in their expenditure reporting. GAO also recommended that HHS conduct a review of TANF reporting requirements and forms and make appropriate changes within its statutory authority to enhance reporting for oversight of TANF funds. HHS agreed with the recommendations and outlined plans to address them. See GAO‑25‑107235.

[29]A management decision is the federal awarding agency's written determination, provided to the recipient, that includes the agency’s evaluation of the audit findings and the recipient’s corrective action plan. A corrective action plan is a document prepared by the recipient describing the actions it will take to address each audit finding included in the auditor's reports. 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.511, 200.521; 45 C.F.R. §§ 75.511, 75.521.

[30]HHS is required to issue a management decision for each audit finding. 2 C.F.R. § 200.513(c)(3)(i); 45 C.F.R. § 75.513(c)(3)(i). HHS officials stated that one letter can include management decisions for multiple findings.

[31]GAO, Single Audits: Improvements Needed in Selected Agencies’ Oversight of Federal Awards, GAO‑17‑159 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 16, 2017).

[32]2 C.F.R. § 200.521(d); 45 C.F.R. § 75.521(d).

[33]Social Security Act of 1935, codified at 42 U.S.C. § 609. The work participation rate measures the extent to which states engage families receiving TANF assistance in certain work activities. 42 U.S.C. § 607.

[34]45 C.F.R. § 262.6. A state has an option to enter into a corrective compliance plan to correct or discontinue a violation in order to avoid a penalty from HHS. The corrective compliance plan must include, among other things, (1) a complete analysis of why the state did not meet the requirements; (2) a detailed description of how the state will correct or discontinue, as appropriate, the violation in a timely manner; (3) the time period in which the violation will be corrected or discontinued; (4) the milestones the state will achieve to assure it comes into compliance within the specified time period; and (5) a certification by the governor that the state is committed to correcting or discontinuing the violation, in accordance with the plan.

[35]45 C.F.R. § 261.50.

[36]Department of Health and Human Services, Work Participation Rates for FY 2022, TANF-ACF-IM-2023-02 (Oct. 5, 2023). HHS issues TANF state work participation rates, which measure how well states engage families receiving assistance in certain work activities during a fiscal year. For work participation rate purposes, states include the 50 states; the District of Columbia; and the U.S. territories of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. A state must meet an overall (or “all families”) and a two-parent work participation requirement or face a potential financial penalty. The statutory requirements are 50 percent for all families and 90 percent for two-parent families, but a state’s individual targets equal the statutory rates minus a credit for reducing its caseload. 42 U.S.C. § 607; 45 C.F.R. §§ 261.21, 261.23.

[37]42 U.S.C. § 608. HHS’s implementing TANF regulations state that any family that has received assistance under any state program funded by federal TANF funds for 60 months, whether consecutive or not, is ineligible for additional federally funded TANF assistance. 45 C.F.R. § 264.1. The Social Security Act, however, provides that states may exempt a family from this time limit by reason of hardship. The average number of families to which an exemption is made for hardship may not exceed 20 percent of the average number of families receiving assistance. 42 U.S.C. § 608(a)(7)(C).

[38]For violations, HHS must reduce the grant payable to the recipient for the immediately succeeding fiscal year quarter by the amount so used in violation. 42 U.S.C. § 609(a)(1)(A). HHS assessed 11 penalties to six states for violations, the largest of which was $7.7 million.

[40]We defined a severe finding as one that the auditor determined contributed to (1) a modified opinion on a compliance audit or (2) a material weakness on an internal control audit. A modified opinion is reported when an auditor (1) concludes that material noncompliance with applicable compliance requirements exists or (2) is unable to obtain sufficient appropriate evidence to conclude whether material noncompliance with applicable compliance requirements exists. The categories of modified opinions are qualified, adverse, and disclaimer. A material weakness is a deficiency in internal control over compliance that indicates a reasonable possibility that material noncompliance with a federal program’s compliance requirement will not be prevented, or detected and corrected, on a timely basis.

[41]To obtain the views of the single audit community, we spoke with representatives of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants; the Association of Local Government Auditors; and the National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers, and Treasurers.

[42]The Single Audit Act is codified at 31 U.S.C. §§ 7501-06, and implementing OMB guidance is published as part of the Uniform Guidance, reprinted in 2 C.F.R. part 200 subpart F. HHS has adopted the text of the Uniform Guidance, with some HHS-specific amendments, in its regulations. See 45 C.F.R. pt. 75.

[43]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014).

[44]A major program is determined using a risk-based approach, which considers current and prior audit experience, oversight by federal agencies and pass-through entities, and the inherent risk of the federal program. 2 C.F.R. § 200.518; 45 C.F.R. § 75.518.