PAYMENT CARDS

Costs and Benefits for Federal Entities

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Michael E. Clements at clementsm@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107298, a report to congressional requesters

April 2025

Costs and Benefits for Federal Entities

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal entities accept payment cards from the public for postage, train travel, national park entry, and other payments. Entities also provide cards to employees for work-related purchases.

GAO was asked to review federal entities’ acceptance and use of payment cards. This report examines (1) fees paid by selected federal entities to payment card companies in FY 2023; (2) these entities’ efforts to reduce fees; and (3) the benefits of accepting and using payment cards.

GAO analyzed aggregated data on payment card fees from seven federal entities, selected because collectively they represent a substantial number of federal entities that accept cards and a range of card management practices and transaction volumes. The entities are Amtrak, Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service, The Smithsonian Institution, U.S. Postal Service, Army and Air Force Exchange Service, Marine Corps Community Services, and Navy Exchange Service Command. GAO also conducted selected analysis of the Internal Revenue Service.

GAO reviewed industry documentation about payment card fees and other arrangements among selected federal entities and payment card companies, as well as documentation related to the General Services Administration SmartPay program. Additionally, GAO conducted a literature review and interviewed industry and subject matter experts and officials from the selected federal entities.

What GAO Found

More than 85 federal entities collected over $43 billion from consumers who used credit, debit, or other payment cards for goods, services, and other payments in fiscal year (FY) 2023 (the most recent data available at the time of the review). The entities in turn paid about $784 million in fees ($1.06 on average per transaction) to card issuers, networks, and companies that facilitated the transactions. Fees paid amounted to 1.8 percent of revenue (which falls within the range of published industry estimates for U.S. merchants).

|

Entity |

Transactions (millions) |

Transaction revenues ($ million) |

Fees paid by entities ($ million) |

|

Treasury Bureau of the Fiscal Service |

153 |

$18,602 |

$312 |

|

Other entities |

590 |

$25,001 |

$472 |

|

Total |

743 |

$43,604 |

$784 |

Source: GAO analysis of data from selected federal entities. | GAO-25-107298

Notes: Numbers may not sum to totals because of rounding. Bureau of the Fiscal Service manages payment card acceptance for an estimated 81 federal entities. Payment cards include credit, debit, and other types of cards, with associated fees paid to card issuers, card networks, and processing companies that facilitated the card transactions.

Transaction fees include an interchange fee set by card networks (e.g., Mastercard, Visa) and paid to the card issuers. Interchange fees accounted for nearly 90 percent of the fees selected entities paid in FY 2023. Network, processing, and other fees made up the remainder. The Department of the Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service manages card payment acceptance and pays fees on behalf of an estimated 81 federal entities. In FY 2023, it paid about $299 million in interchange and network fees and about $13 million in processing and other fees. Other entities (e.g., Amtrak, U.S. Postal Service) maintain their own relationships with payment card companies and pay fees directly.

Federal entities have taken steps to reduce payment card costs. For example, five of the selected federal entities told GAO they reduced fees by meeting transaction volume thresholds. One entity limited the types of payment cards accepted for certain transactions, and another limited transaction amounts. However, two entities described challenges navigating complex network rules in their efforts to reduce fees. Additionally, two entities reported unsuccessful negotiations with card networks to lower interchange fees.

Federal entity officials said entities receive several benefits from accepting and using payment cards. For example, accepting cards helps reduce the administrative burden of handling cash and checks and enhance customer satisfaction by meeting consumer expectations for card payment options. Benefits of providing cards to employees for work-related purchases include lower administrative costs, such as those for cash advances, and closer tracking of employee spending to help prevent fraud. Also, payment cards provided through the GSA SmartPay program generate spending-based refunds, which totaled $488 million in FY 2023 based on net eligible funds of $37 billion spent.

Abbreviations

|

Amtrak |

National Railroad Passenger Corporation |

|

BFS |

Bureau of the Fiscal Service |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

IRS |

Internal Revenue Service |

|

MCC |

merchant category codes |

|

NAFI |

Nonappropriated Fund Instrumentalities |

|

PIN |

personal identification number |

|

USPS |

United States Postal Service |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 30, 2025

Congressional Requesters

Credit and debit card payments accounted for 60 percent of all U.S. consumer payments in 2023.[1] Like private businesses, many federal entities accept credit, debit, and other payment cards from the public for a wide variety of goods, services, and other payments, such as postage, train tickets, and national park entry fees. Acting as “merchants” in these transactions, federal entities pay fees to the card networks, financial institutions that issue the cards, and other companies that facilitate the transactions (payment card companies). The card networks, which include American Express, Mastercard, and Visa, generally set the largest of the fees that merchants pay for each transaction. The financial institution that issues the card to the consumer (known as the card issuer) receives the fee. Additionally, federal entities provide cards to their employees for work-related purchases, such as travel.

Given the widespread acceptance and use of payment cards by federal entities, you asked us to analyze data on the fees paid by federal entities to card networks and card issuers for accepting payments by credit, debit, and prepaid cards, and benefits of accepting and using cards.[2] This report examines (1) the total amount of fees paid by selected federal entities to payment card companies for card transactions processed in fiscal year (FY) 2023; (2) efforts by selected federal entities to reduce fees; and (3) the benefits federal entities gain from accepting and using payment cards.

To determine fees that federal entities incurred for accepting payment cards, we analyzed aggregated data from the Department of the Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service (BFS), which processes and generally bears the cost of payment card transactions on behalf of many federal entities; the National Passenger Railway Corporation (Amtrak); The Smithsonian Institution; U.S. Postal Service (USPS); and three selected Department of Defense (DOD) Nonappropriated Fund Instrumentalities (NAFI)—the Army and Air Force Exchange Service, Marine Corps Community Services, and Navy Exchange Service Command.[3] We selected these federal entities because they collectively represent a substantial number of federal entities that accept payment cards and reflect a range of payment card management practices and transaction volumes. We analyzed FY 2023 data (the most recent data available at the time of our review) from these entities on total payment card transaction volume and dollar value, and total transaction fees by fee type, card type, and card network.[4]

To identify federal efforts to reduce the costs of accepting payment cards, we reviewed published industry documentation and documentation about fees and other arrangements among selected federal entities, processing companies, financial institutions, and networks. We also interviewed federal entity officials and representatives of two networks and one financial institution.

To identify benefits of accepting and using cards, we reviewed documents and interviewed officials from the selected federal entities to gather their perspectives. We also reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from the General Services Administration (GSA), which administers the SmartPay purchase card program used by federal entities. Additionally, we collected and analyzed data from GSA on purchase card refunds.[5]

We also conducted a literature review of research on benefits and costs of accepting and using cards, including studies in peer-reviewed journals, as well as news articles, public statements, and congressional testimonies. Based on the results of this review, we selected a nonprobability sample of eight organizations whose representatives we interviewed about the potential benefits and challenges associated with accepting and using payment cards. For more information on our objectives, scope, and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Payment Card Transactions and Participants

Consumers commonly use payment cards (including credit, debit, prepaid, and charge cards) to pay merchants for goods and services.

· Credit cards allow consumers to pay for goods and services using funds loaned by the card issuer, typically a commercial bank or other financial institution. Consumers can either pay the account balance in full by the end of the billing cycle or pay part of the balance and pay interest and other fees on the remaining balance.

· Debit cards enable consumers to draw funds directly from their financial institution accounts to pay for purchases. Debit transactions can be authorized via a signature or a personal identification number (PIN). Signature debit and PIN debit transactions have different authorization processes and are routed over different network infrastructure.[6]

· Prepaid cards are not linked to an individual’s financial institution demand deposit account. Instead, consumers load funds onto the card prior to purchase. These cards are issued by financial institutions that hold the funds that have been loaded onto the card.

· Charge cards must be paid in full at the end of each billing cycle and are issued by financial institutions.

The financial institutions that issue these cards have relationships with one or more card networks. In the U.S., the largest networks are American Express, Discover, Mastercard, and Visa. There are also several other debit card networks.

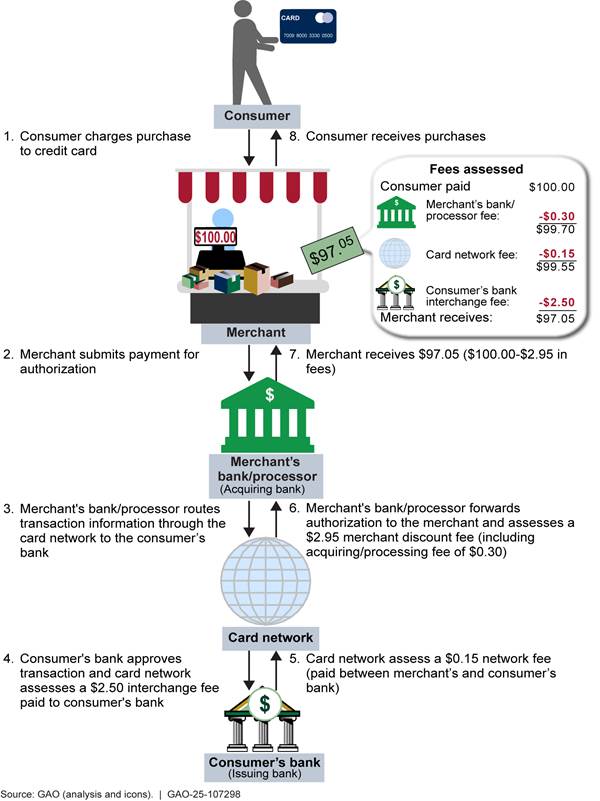

The parties involved in a typical payment card transaction depend in part on the card network. For example, Mastercard and Visa transactions involve the card network, card issuer, consumer, merchant and acquirer (or processor) (see table 1).[7]

|

Card issuer |

the financial institution that issued the consumer’s payment card |

|

Consumer |

the cardholder who initiates the payment |

|

Merchant |

the entity accepting the card payment |

|

Acquirer and processor |

the merchant’s financial institution (acquirer) and associated payment processing company (processor), which process the transaction |

|

Card network |

the network facilitating the transaction |

Source: GAO summary of industry information. | GAO‑25‑107298

Note: Certain other card networks, such as American Express and Discover, also act as issuer.

Merchants pay a merchant discount fee (also referred to as a transaction fee) to the processor or acquirer, which in turn pay fees to the card issuer and network.

In a typical Mastercard or Visa transaction, the merchant’s processor or acquirer charges a merchant discount fee, which includes the following components:

· The interchange fee is paid by the merchant’s bank or acquirer to the card issuer (typically the financial institution that issued the card).[8] The networks establish the rates that determine the interchange fees and adjust the rates semiannually. The interchange rate assessed on a card transaction is generally composed of (1) a fixed fee per transaction and (2) a percentage of the value of the consumer’s purchase.

· Network fees are generally fixed fees per transaction that are established by each card network. The fees are paid to the card network as compensation for operating the network.

· Payment processor or acquirer fees make up the remainder of the merchant discount fee. They are paid to the processor or acquiring bank for their services, which include routing the transactions to appropriate networks and issuers.[9]

Some merchants pass all or a portion of the merchant discount fee on to the consumer by adding a surcharge or convenience fee when consumers use a credit card.[10]

Figure 1 illustrates the role of the parties involved in a typical credit card transaction and the flow of fees among them.

Note: This graphic illustrates a typical merchant accepting Visa or Mastercard but processes and fees vary. For example, for the Department of the Treasury’s Bureau of Fiscal Service, interchange and other fees are not “deducted” from the transaction amount that is collected by the federal entity. Instead, transactions are settled “at par,” with associated costs of card acceptance paid separately. For cards issued by American Express or Discover, the card network also acts as issuer.

Debit Card Interchange Fee Regulation

Debit card interchange fees have been subject to federal regulation since 2011.[11] Under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, any interchange fee for electronic debit transactions must be reasonable and proportional to the cost incurred by the card issuer with respect to the related transaction.[12] The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System implemented this requirement through Regulation II, which became effective on October 1, 2011.[13] Regulation II established a cap on interchange fees for electronic debit transactions, setting the limit at the sum of (1) $0.21 per transaction and (2) 5 basis points (0.05%) of the transaction’s value.[14]

However, small issuers and certain types of debit cards are exempt from these requirements.[15] Regulation II also prohibits network exclusivity, requiring issuers and networks to enable processing of electronic debit transactions on at least two unaffiliated networks.[16] Additionally, merchants must be allowed to direct the routing of the electronic debit transactions over these networks.[17]

In contrast to debit card interchange fees, interchange fees for credit card transactions are not specifically regulated at the federal level.[18] These fees have long been the subject of debate: merchants argue that networks charge higher-than-competitive fees, while the banking industry argues that the fees reflect the cost of providing the transactions.[19] Members of Congress proposed legislation in 2023 that would require the Federal Reserve to regulate network competition for credit card transactions.[20] This would include, for example, prohibiting covered card issuers and networks from restricting the processing of credit transactions to the two networks with the largest market shares.[21] The legislation is designed to lower credit card interchange fees by increasing competition in the market.[22]

Federal Entities That Accept and Use Payment Cards

Federal entities that accept cards as a method of payment typically participate in BFS’s Card Acquiring Service. The service supports various card acceptance points, including point-of-sale devices (for “card present” transactions) and Pay.gov (for “card not present” including e-commerce transactions). According to BFS officials, federal entities that settle funds through Treasury’s General Account must use the Card Acquiring Service to process payment card transactions, absent a statutory authority providing otherwise. BFS operates the service through a financial agent, which provides acquiring bank services and partners with a card processor for transaction processing. The financial agent pays related card fees (interchange fees, network fees, and processing and other fees), which are then reimbursed by BFS, according to BFS officials.

Entities that accept payment cards but do not participate in BFS’s Card Acquiring Service operate their own card processing programs. These entities pay the associated fees directly to the companies with which they maintain relationships. For example, Amtrak, Smithsonian, USPS, and certain DOD NAFIs have relationships with processors or acquirers to process payment cards for their customer transactions.[23] In addition, IRS contracts with three companies to process tax payments made by cards, and taxpayers are responsible for paying associated card fees.

In addition, federal entities provide cards to employees, such as through the GSA SmartPay program. To implement this program, GSA contracts with U.S. Bank and Citibank to offer cards for work-related purchases such as office supplies, business services, fuel and vehicle maintenance, and travel services. The federal entities select cards from among the four following business lines:

1. Purchase (for supplies and services)

2. Travel (for airline, hotel, and travel-related expenses)

3. Fleet (for fuel and supplies for government-issued vehicles)

4. Integrated (a combination of purchase, travel, or fleet cards)

As part of the GSA SmartPay program, federal entities maintain task orders with one or both of the two banks that issue these cards. Entities may receive refunds, which are monetary payments from the banks calculated based on spending volume and timely payment. GSA is compensated for administering the program through a contract access fee deducted from the refunds entities receive. Under the GSA SmartPay master contract, this contract access fee cannot exceed 6.5 basis points (0.065%) of eligible net charge volume.[24] The contract also provides for federal entities to negotiate task orders directly with the banks. The task orders establish terms such as which products and services the bank will provide and refund rates.

Over 85 Federal Entities Paid More Than $780 Million in Card Fees in FY 2023

Our analysis found that more than 85 federal entities collectively paid about $784 million in fees in FY 2023 to process payment card transactions (see table 2). These fees covered roughly 740 million transactions conducted using credit, debit, and other types of payment cards that accounted for more than $43 billion in revenue. Selected federal entities paid $1.06 in fees on average per transaction to card issuers, networks, and processors or acquirers. Fees paid were about 1.80 percent of revenue.[25]

To conduct this analysis, we obtained data from BFS, which manages approximately 2,000 card acceptance accounts for an estimated 81 federal entities.[26] We also obtained data from Amtrak, Smithsonian, USPS, and selected DOD NAFIs—the Army and Air Force Exchange Service, Marine Corps Community Services, and Navy Exchange Service Command.[27]

Table 2: Payment Card Transaction Revenues and Fees Paid by Selected Federal Entities, Fiscal Year 2023

|

Entity |

Transactions (millions) |

Transaction revenues ($ million)a |

Fees ($ million)b |

|

Treasury Bureau of the Fiscal Servicec |

153 |

$18,602 |

$312 |

|

Other entities |

590 |

$25,001 |

$472 |

|

Total |

743 |

$43,604 |

$784 |

Source: GAO analysis of federal entity data. | GAO‑25‑107298

Note: Numbers may not sum to totals because of rounding.

aPayment cards include credit, signature debit, personal identification number debit, and prepaid cards.

bFees include interchange fees, network fees, and processing and other fees federal entities pay to the companies that facilitate the transactions.

cThe Department of the Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service manages payment card acceptance for an estimated 81 federal entities.

The total amount of fees each entity pays depends on a range of factors. These include the number and total dollar value of the transactions and the type of card used (credit or debit).

Number of and dollar value of transactions. The total fees an entity pays to companies that facilitate payment card transactions depends on the number and dollar value of transactions. Entities with higher sales volumes and revenues from card payments generally incur higher fees.

In addition, our analysis found that total fees increased or decreased in tandem with the transaction revenue over time. For example, BFS’s Card Acquiring Service payment card transaction revenue collections on behalf of federal entities increased by about 20 percent between FY 2019 and 2023, growing from approximately $16 billion (in 2023 dollars) to approximately $19 billion. Correspondingly, total fees paid by BFS rose by about 22 percent, from approximately $254 million in FY 2019 (in 2023 dollars) to $312 million in FY 2023.

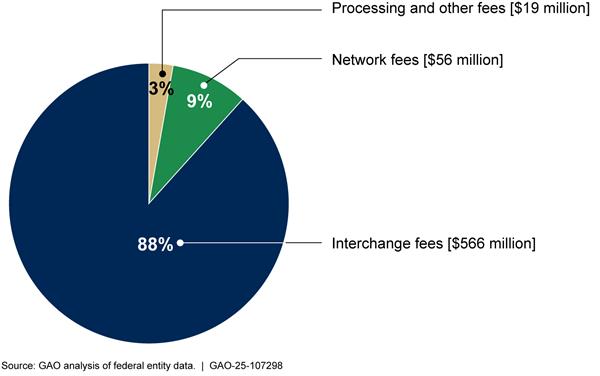

Type of card used. The type of card used—credit or debit—also significantly affects the fees entities incur, particularly the interchange fee, and interchange fees accounted for nearly 90 percent of the total fees paid by selected federal entities in FY 2023 (see fig. 2).

Notes: Data represent credit and debit card (payment card) fees from selected entities. These fees comprise interchange fees paid to the card-issuing financial institutions, network fees paid to participating card networks, and processing and other fees paid to companies processing the transactions. Some entities’ data for interchange fees include data for card networks that do not charge separate network fees.

Card issuers provide various types of cards with differing interchange rates based on regulatory requirements, risk considerations, processing costs, associated cardholder rewards programs, and other factors. Fees entities pay to accept credit cards are generally higher than for debit cards in part because debit card interchange fees are regulated and capped.[28] Credit cards issued to individual consumers generally have lower interchange rates than credit cards issued to commercial entities, for example. Card networks set interchange rates (which determine the interchange fees entities pay) based on a number of factors, one of which is the transaction type. In-person, card-present transactions generally pose lower risk of fraud, while card-not-present transactions (e.g., online purchases) carry higher risks of fraud and chargebacks, resulting in higher interchange fees.[29] Another factor is the type of card. For example, rewards credit cards that offer cash back or points generally have higher interchange fees than non-rewards credit cards. Further, the merchant’s business line or merchant category can also affect the interchange rate, as discussed later in the report.

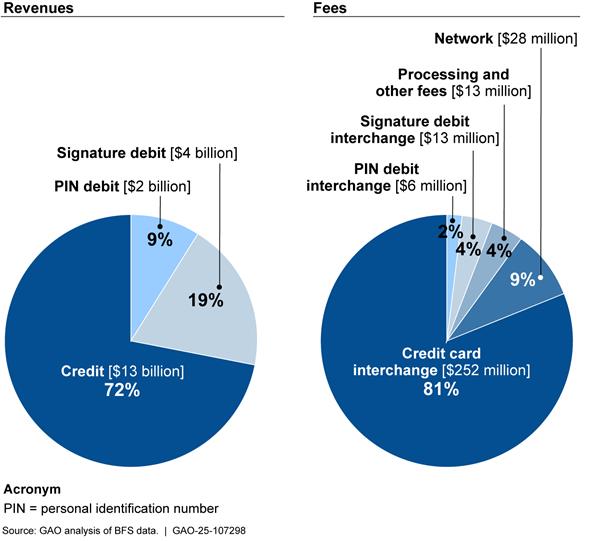

In general, when more consumers use credit cards instead of debit cards, entities pay higher fees. For example, we found that over two-thirds of BFS payment card revenue collected on behalf of federal entities was generated through credit card payments. Therefore, credit card interchange fees represented the highest share of BFS’s total fees, accounting for 81 percent of the total fees (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Payment Card Revenues and Fees Paid by the Bureau of the Fiscal Service (BFS), Fiscal Year 2023

Note: BFS is a component of the Department of the Treasury that manages card acceptance operations for an estimated 81 federal entities. Interchange fees are paid to the card-issuing financial institutions, network fees are paid to participating card networks, and processing and other fees are paid to companies processing the transactions. Debit card transactions are verified using a signature or a personal identification number; fees may differ for the two types of transactions. Data for interchange fees include data for card networks that do not charge separate network fees.

In addition to the interchange fees, entities paid fees to card networks, acquirers, and to processors. Processing fees include other costs entities incur to accept card payments. Such costs could include software for network infrastructure, fraud prevention measures, hardware for processing, and point-of-sale card terminal rentals.

Federal Entities Took Steps to Reduce Costs of Accepting Cards but Identified Challenges

Steps Entities Took to Reduce Costs Included Optimizing Rates and Limiting Card Types Accepted

Federal entities in our review took steps to reduce fees or other costs associated with the acceptance of payment cards. These included optimizing rates and pricing models, limiting card acceptance by transaction amount or card type, passing fees on to consumers, conducting analyses, and considering alternative service providers.

Optimizing MCC interchange rates. To reduce payment card fees, federal entities have leveraged merchant category codes (MCC), which card networks use to classify transactions according to business type.[30] Networks such as Mastercard and Visa publish schedules with interchange rates corresponding to merchant categories.[31] According to published 2023–2024 schedules for Mastercard and Visa, interchange rates for consumer credit cards ranged from under 1 percent to approximately 3 percent, plus a fixed amount per transaction.[32] Public sector rates were generally on the lower end of this range, with Mastercard’s published public sector rate at 1.55 percent (plus $0.10), for example. Moreover, card networks may offer larger supermarkets lower consumer credit card interchange rates than the public sector, according to network officials. For example, the lowest rate for the supermarket MCCs in the 2023–2024 MCC schedule published by Mastercard is 1.15% + $0.05.

Federal entities have reduced fees in some cases by categorizing transactions under MCCs that have lower rates. For example, according to BFS officials, BFS’s financial agent has undertaken efforts in the past to reduce fees associated with the Defense Commissary Agency’s transactions by negotiating with card networks a reduced supermarket MCC rate that is generally available only to supermarkets with higher transaction volumes than the Defense Commissary Agency.[33]

Meeting transaction volume thresholds. Officials from five federal entities in our review told us they have reduced fees by meeting transaction volume thresholds. Some networks establish tiered interchange rates, offering lower rates as transaction volumes increase.[34] Merchants with high transaction volumes—typically determined by total transactions or dollar amount under a given MCC—generally qualify for lower-rate tiers.

Selecting optimal pricing models. Federal entities have worked with processors to select a pricing model that reduces card processing fees. Three pricing models are common among processors or acquirers, based on our review of industry documentation.

1. Interchange plus: Acquirers or payment processors pass through network and interchange fees, adding their own processing fees.

2. Tiered pricing: Acquirers or processors structure fee rates based on risk factors and other requirements.

3. Flat-rate (blended) model: Merchants pay a uniform rate for all transactions, blending credit and debit card rates.

A few entities’ officials told us they operate under the interchange-plus model. Merchants generally choose models that best fit their business needs and may select in part according to their size. Larger merchants may choose the interchange-plus processing model because their high transaction volumes and ability to analyze transaction types may enable them to take advantage of lower fee rates. Smaller merchants may choose a flat-rate (blended) model to simplify their management of card payments.

Increasing authorization rates. Card issuers may decline transactions if they cannot verify the cardholder’s identity or suspect fraud. Disputed charges can result in chargebacks, which require refunds and incur additional fees.

Officials from some entities we interviewed reported taking steps to increase the proportion of successfully authorized transactions, which helps them qualify for the lowest fee tiers established with their processor or network. For example, officials from one entity told us they work with their processor to meet network requirements for securing or verifying consumers’ identities. This effort has raised their authorization rates, thereby reducing fees. Other reported practices include using an encrypted credit card access program provided through the acquirer and implementing address verification for card-not-present transactions.[35]

Routing transactions over lower-cost networks. Processors can reduce merchants’ costs by routing transactions through networks with lower fees. The routing process depends on a number of factors, such as the type of payment card, the specific card issuer, and applicable legal requirements. For example, under Regulation II, merchants must be allowed to direct the routing of electronic debit transactions over at least two unaffiliated networks. Officials of three of the entities we reviewed noted that their processors route debit transactions to networks with the lowest interchange rates.

Limiting payment card acceptance by transaction amount or card type. To reduce costs, some federal entities limit the size of the transaction or the types of payment cards they accept for specific products or transactions. For example, BFS’s Card Acquiring Service imposes a $24,999.99 maximum on total daily credit card transactions processed from a single payer. No such limit is imposed on debit card transactions. Another entity does not accept PIN debit card payments because the expenses required to implement hardware, security, and software for PIN debit payments would outweigh the potential benefits, according to an analysis the entity conducted.

Passing fees on to consumers. Officials from two federal entities told us they pass all or a portion of transaction fees to card-using consumers. For example, IRS is authorized by law to accept tax payments by credit and debit card, provided that all payment card fees for such transactions are passed on to the taxpayer.[36] Similarly, the Defense Commissary Agency is required by law to charge a user fee to certain veterans and caregivers of veterans who use a debit or credit card at commissaries.[37] The fee is intended to offset the additional costs to the government associated with card use by the patrons, including expenses related to card network use and related transaction processing fees. However, aside from the Defense Commissary Agency, BFS officials stated that they were not aware of any statutory authorities that would authorize federal entities participating in the Card Acquiring Service to impose surcharges or convenience fees on card transactions.

Hiring consultants and conducting analysis. Two entities hired consultants with industry expertise to identify ways to reduce fees. These consultants provided information about what peers are paying for the same type of services. Officials of one entity said its consultant helped inform its negotiations, resulting in reduced fees. Independent research and analysis also have helped federal entities identify best practices. Officials from two entities noted that regular analysis of their transactions helped ensure compliance with contractual requirements and qualify for the lowest fee tiers. In addition, officials from two entities told us they informally shared best practices with other federal entities on ways to process transactions that reduce fees.

Considering alternative processors or acquirers. Like other merchants, a federal entity can select a payment processor or acquiring bank that offers services tailored to its needs. Officials from three entities in our review said they have conducted cost and service comparisons when selecting processors or acquirers. Officials from one entity said they reviewed their existing processor’s pricing and considered an offer from a competitor. This led them to discuss better terms with the original processor. Contracting procedures differed among the federal entities in our review.[38]

Challenges to Reducing Costs Included Difficulty Auditing Fees and Negotiating Fee Reductions

While the entities we reviewed had some success in managing costs associated with accepting payment cards, they also identified challenges with certain efforts.

Difficulty auditing fee arrangements. Despite adopting a range of strategies and approaches to reducing fees, officials from two entities described challenges in analyzing complex network rules and validating fees.[39] Entities rely on processors for information about the fees charged for individual cards, which vary based on the card issuer’s terms. Two entities conducted audits to validate card-related fees paid to processors, but both encountered challenges with analyses due to data limitations.[40] One entity’s audit cited an inability to validate $23.4 million in fees. Its chief audit executive noted challenges in verifying fee calculations across thousands of transactions with hundreds of associated fee types.[41]

Unsuccessful negotiations to reduce interchange fees. Officials of two federal entities told us they attempted to negotiate reduced interchange fees directly with networks but were unsuccessful. Network officials told us they generally do not negotiate interchange rates with individual merchants. Networks may negotiate rates in markets where they seek to expand card acceptance and transaction volumes, the officials said.[42]

Unsuccessful request for marketing funds. Officials from one entity told us they were unable to negotiate marketing funds from a card network to offset the cost of accepting payment cards (such as for software and hardware).[43] Networks sometimes provide merchants with marketing funds as an incentive to promote card use among consumers. However, the entity was unable to secure these funds, despite having received them previously.

Benefits of Accepting and Using Cards Include Customer Convenience and Refunds from Issuers

Accepting Cards Helps Entities Meet Consumer Expectations and Track Spending Patterns

Federal entities accepting payment cards experience benefits such as enhanced customer satisfaction, improved operational efficiency, and the ability to track customer spending patterns, according to stakeholder interviews.

Customer satisfaction. Officials from all eight of the entities we reviewed that accept payment cards said that consumers expect to be able to use payment cards for purchases or payments.[44] For example, officials of two NAFIs reported that 90 percent or more of their sales come from credit or debit cards, and Amtrak officials also said cards account for over 90 percent of ticket sales revenue. Accepting cards online further enhances customer convenience.

Operational efficiency. Accepting payment cards improves efficiency compared with other forms of payment, according to officials of four entities, three industry representatives, and two subject matter experts we interviewed. Processing cash or checks can require staff or other resources to manage lock boxes or payment deposits. Card transactions are verified immediately, while checks may take days to process. The National Park Service’s move to cashless fee collection in some national parks in recent years saved funds previously spent on processing cash, according to an agency press release.[45]

Ability to track spending patterns. Card acceptance gives federal entities insights into consumer spending patterns. Representatives of five entities told us they use data from processors or acquiring banks to track trends. For example, USPS receives daily and monthly reports that staff use to analyze spending trends, while Amtrak uses card data to track daily operations, analyze historical patterns, and improve budget forecasting. Amtrak staff noted that payment data revealed a trend of increased train travel during inclement weather, which informed budget forecasting.

Fraud prevention. Accepting payment cards can also help federal entities enhance security and prevent fraud. For example, USPS officials noted that card use reduces cash handling, mitigating theft risks. Furthermore, card networks provide additional protections by screening transactions for potential fraud before authorization.

Aside from these categories of benefits, however, the federal entities we reviewed did not provide comprehensive data on cost savings from accepting cards, which is consistent with our 2008 findings.[46] Further, while studies from government, academic, and industry sources have compared the costs of different payment methods, precise savings estimates specific to federal entities remain difficult to calculate.

Benefits of Entities Using Cards Include Refunds, Efficiency, and Fraud Monitoring

A large number of federal entities offer payment cards for use by employees. This includes those entities participating in the GSA SmartPay program: the 24 federal entities subject to the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 and more than 90 other federal entities.[47] In FY 2023, entities used SmartPay cards to conduct over 88 million transactions, totaling more than $37 billion in spending on goods and services, according to GSA data.[48] The Department of Veterans Affairs and DOD accounted for the highest spending levels, according to our analysis.

Seven entities in our review participate in the GSA SmartPay program; two also operate other payment card programs.[49] These entities identified the following benefits of using GSA SmartPay or similar programs.

Refunds

Entities receive refunds from the card issuers, which the GSA SmartPay master contract defines as monetary payments provided to agencies, based on the dollar or “spend” volume during a specified period.[50] In FY 2023, for example, organizations that participated in the GSA SmartPay program earned gross refunds of approximately $488 million. Net refunds totaled $472 million (see fig. 4). According to GSA, this net refund amount represented a 1.7 percent rate of return across all business lines, excluding payments that are not eligible for refunds.[51] For example, according to USPS, its employees spent $1.7 billion through purchase, fleet, travel, and uniform cards, and USPS received approximately $37 million in refunds.[52]

The refunds that participants receive are net of fees deducted to compensate GSA for managing the GSA SmartPay program. GSA’s Center for Charge Card Management does not receive a direct appropriation, according to GSA officials. Instead, GSA receives a contract access fee deducted from each entity’s gross refunds. This fee covers GSA’s GSA SmartPay program management costs. GSA received almost $16 million in contract access fees in FY 2023.

Note: General Services Administration (GSA) contract access fees, which fund GSA’s administration of the GSA SmartPay program, are deducted from total gross refunds. The data have been adjusted for inflation using Consumer Price Index data with base year 2023. The data represent refunds received by all GSA SmartPay participating organizations, including federal entities and Tribes and tribal organizations.

Operational Efficiency

Federal entity officials we spoke with said that charge card usage enhances operational efficiency by reducing administrative costs associated with employee spending.[53] This includes minimizing the need for cash advances and imprest funds.[54] Charge cards also enable timely purchases—for example, USPS drivers use GSA SmartPay fleet cards to buy gas as needed. GSA representatives told us that no formal analyses have quantified the benefits of the GSA SmartPay program. But they noted it was more efficient for smaller purchases.[55]

Fraud Prevention

To mitigate fraud risks, federal entities have monitored charge card use and leveraged tools provided by issuing banks. Federal law and Office of Management and Budget memorandums require federal agencies to monitor charge card use among employees and report annually on internal controls.[56] Additionally, Offices of Inspectors General must periodically assess agency purchase and travel card programs to analyze the risk of improper charges. For example, a September 2024 GSA Office of Inspector General audit concluded that fraud risks were moderate in GSA’s purchase card program and low in its travel card program.[57]

In addition, the GSA master contract requires issuing banks to provide GSA SmartPay participants with fraud analytics tools that test transactions against entity-specific rules. Amtrak officials noted that chip technology and real-time data help them prevent and detect unauthorized use. Officials from Smithsonian, USPS, and GSA said access to employee spending data also helps identify unusual activity. The ability to set card usage limits further helps prevent fraud, noted USPS officials.

Cardholders are generally protected from fraudulent transactions. If the cardholder reports unauthorized charges, the issuing financial institution investigates and may reverse the charge. This helps to shield the cardholder—or, in this case, the federal entity—from liability.

Other Benefits

Stakeholders we interviewed noted two additional benefits of charge card use by federal entities:

· The GSA City Pair Program, which uses the GSA SmartPay charge card, offers federal entities discounts on flights.[58]

· The grace period before payment due dates allows entities to charge expenses, pay them within the grace period, and use funds for other uses during that time.[59]

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to Amtrak, BFS, DOD, GSA, IRS, Smithsonian, and USPS for review and comment. Amtrak, BFS, and Smithsonian provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. DOD, GSA, IRS, and USPS did not have any comments on the report.

As agreed with your office, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, Secretaries of Treasury and Defense, the President of Amtrak, Acting Administrator and Deputy Administrator of the General Services Administration, Acting Tax Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Postmaster General (Acting) of USPS, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be made available at no charge at the GAO website at www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff members have any questions about this report, please contact me at clementsm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

Michael E. Clements

Director, Financial Markets and Community Investment

List of Requesters

The Honorable Richard J. Durbin

Ranking Member

Committee on the Judiciary

United States Senate

The Honorable Roger Marshall, M.D.

United States Senate

The Honorable Peter Welch

United States Senate

The Honorable Lance Gooden

House of Representatives

The Honorable Zoe Lofgren

House of Representatives

The Honorable Tom Tiffany

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jeff Van Drew

House of Representatives

This report examines (1) the total amount of fees paid by selected federal entities to processing companies, financial institutions, and card networks (payment card companies) for card transactions processed in fiscal year (FY) 2023; (2) efforts by selected federal entities to reduce these fees; and (3) the benefits federal entities gain from accepting and using payment cards.

To determine fees that federal entities incurred for accepting payment cards, we analyzed aggregated data from seven federal entities that accept payment cards. We selected these entities because they represent a substantial number of federal entities that accept payment cards and reflect a range of payment card management practices and transaction volumes. Our selection included entities that receive annual federal appropriations and those that rely on nonappropriated funds.

Specifically, we examined the Department of the Treasury’s Bureau of the Fiscal Service (BFS), National Passenger Railway Corporation (Amtrak), The Smithsonian Institution, U.S. Postal Service (USPS), and selected Department of Defense (DOD) Nonappropriated Fund Instrumentalities (NAFI).[60] The NAFIs were the Army and Air Force Exchange Service, Marine Corps Community Services, and the Navy Exchange Service Command. We also conducted selected analysis of the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which accepts payment cards but does not pay associated fees (the taxpayer pays a convenience fee directly to the card processor).[61]

To estimate the number of entities (81) that participate in BFS’s Card Acquiring Service (which manages card acceptance operations for other federal entities), we obtained information from BFS on the total number of accounts maintained by its financial agent.[62] We then verified the entity names associated with each account against the list of federal entities in the Federal Register and individual entity websites.[63] One analyst verified the entity name against the public sources and a second analyst reviewed the work, resolving issues or discrepancies with a third analyst as needed.

We obtained FY 2023 data from the seven entities, which were the most current data available during the period of our review. We obtained data including total payment card transaction volume and dollar value, and total transaction fees by fee type, card type, and card network. Not all entities provided all these data elements. In addition, we received these data elements from BFS for FY 2019–2022 and used the Consumer Price Index to adjust prior year dollar values to reflect 2023 dollar values.

To assess the quality of the data provided by each entity, we checked for errors and followed up with entities to understand the reasons for those errors and obtain corrections. We also interviewed entity staff about their data processing and quality checks. In addition, we reviewed samples of reports and dashboards from card processors, who provide the source data to the entities. We obtained written responses to questionnaires or interviewed staff of the entities about the reliability of these source data. We determined that the data for all selected federal entities were reliable for the purposes of summarizing fees that federal entities paid to card networks, financial institutions, and processors.

Identifying Efforts to Reduce Costs

To identify the efforts these federal entities have taken to reduce costs related to accepting payment cards, we reviewed industry documentation published by card networks, processors, and financial institutions as well as industry analyses about steps merchants may take to reduce fees. Published documentation we reviewed included card network rules and payment processor guidance for merchants. We also reviewed documentation, such as agreements, about fees and other arrangements among the selected federal entities and payment card companies.

In addition, we interviewed officials of federal entities about efforts to reduce costs, including their negotiations with payment card companies and challenges encountered. We also interviewed representatives of two networks and one card-issuing financial institutions.

To identify benefits to federal entities of accepting and using cards, we collected General Services Administration (GSA) FY 2019–2023 data (the most current data available at the time of our review) on its GSA SmartPay purchase card program. We determined the total dollar amount its participants received in refunds. We used the Consumer Price Index to adjust prior year data to reflect 2023 dollar value. To assess the reliability of these data, we interviewed GSA staff about their data sources and quality control steps. We determined that the data were reliable for reporting on the aggregate size of the refunds.

To estimate the number of participants in GSA SmartPay, we obtained a list of account holders from GSA, provided via its two contracted banks. We verified the entity names associated with each account against federal entities listed in the Federal Register or individual entity websites as needed. One analyst verified the entity name against public sources, and a second analyst reviewed the work, and resolved any identified issues by conferring with a third analyst.

Additionally, we reviewed documents and interviewed officials from the selected federal entities to gather their perspectives. We also reviewed documentation and interviewed officials from GSA, which administers the SmartPay purchase card program used by federal agencies. We conducted a literature review of the benefits and challenges of accepting and using payment cards; we identified studies published in peer-reviewed journals, news articles, public statements, and congressional testimony on federal and other merchants’ experiences accepting cards and providing cards to employees.

Based on the results of this review, our prior work, and recommendations from an initial selection of organizations, we selected a nonprobability sample of eight organizations whose representatives we interviewed about their perspectives on the benefits and challenges of accepting and using payment cards. These organizations were the Brookings Institution, California Department of Transportation, Electronic Payment Coalition, Merchant Payment Coalition, Olin Business School at Washington University in Saint Louis, Mastercard, Visa, and U.S. Bank.

This report omits information that federal entities deemed to be sensitive and require protection from public disclosure (for example, proprietary or competition-sensitive information). The report also omits attribution to specific federal entities in certain figures and examples due to the sensitive nature of the underlying information.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Michael E. Clements, clementsm@gao.gov

In addition to the contact named above, Karen Tremba (Assistant Director), Catherine Gelb (Analyst in Charge), Annie (Pin-En) Chou, Garrett Hillyer, Paulina Maqueda Escamilla, Siena Pilati, Abbie Sanders, Lindsey Shapray, Jena Sinkfield, and Haley Wall made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

https://www.gao.gov/about/contact-usm 7814, Washington, DC 20548

[1]Berhan Bayeh, Emily Cubides and Shaun O’Brien, 2024 Findings from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice (Washington, D.C.: 2024). The Survey and Diary of Consumer Payment Choice is a collaboration of the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta and Boston and FedCash Services. See also Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve Payments Study, 2022 (Washington, D.C.: 2024). According to this study, the value of debit, credit, and prepaid card payments made in the U.S. was $9.43 trillion in 2021, and the value of these payments increased by 10 percent each year from 2018 through 2021.

[2]We previously reported on fees that federal entities pay to card networks and card issuers and the benefits federal entities identified from accepting payment cards, such as increased sales, better tracking of transactions, and reduced fraud. See GAO, Credit and Debit Cards: Federal Entities Are Taking Actions to Limit Their Interchange Fees, but Additional Revenue Collection Cost Savings May Exist, GAO‑08‑588 (Washington, D.C.: May 15, 2008).

[3]DOD defines a nonappropriated fund instrumentality as a DOD organizational and fiscal entity supported in whole or in part by nonappropriated funds. Department of Defense Instruction No. 1015.15, Establishment, Management, and Control of Nonappropriated Fund Instrumentalities and Financial Management of Supporting Resources, encl. 2, ¶ E2.13 (Oct. 31, 2007, amended Mar. 20, 2008). For more information about NAFIs, see GAO, Principles of Federal Appropriations Law, Third Edition, GAO-08-978SP, vol. III, ch. 15 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2008), 15-226-15-276, in conjunction with GAO, Principles of Federal Appropriations Law: Annual Update to the Third Edition, GAO-15-303SP (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 2015), 15-3-15-4. We also conducted selected analysis on the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). IRS contracts with three companies to process credit and debit card payments made by taxpayers who opt to pay their income taxes by payment card. IRS does not pay payment card fees for these transactions. Instead, taxpayers pay a convenience fee to the company that processes the card transaction.

[4]We assessed the reliability of the data we received from each entity by checking for errors within the data, reviewing samples of reports, and obtaining responses to questions from knowledgeable staff. We determined that the data for all selected federal entities were reliable for the purposes of summarizing fees that federal entities paid to card networks, financial institutions, and processors.

[5]To assess the reliability of the GSA data, we interviewed staff about the source of the data and GSA’s quality control steps. We determined the data were reliable for reporting on the aggregate size of the refunds.

[6]Signature debit transactions are processed on credit card network infrastructure and involve two steps—authorization is transmitted in one message and clearing information is transmitted in a separate message. In contrast, PIN debit cards are processed through a single-message system that authorizes and clears the charge within a single message.

[7]American Express and Discover operate differently from Mastercard and Visa, with the former two acting as a combined issuer and network for their respective transactions.

[8]According to officials of one network, transaction fees compensate issuers for their cost of funds in the period between their settlement with the merchant and when they are paid by the cardholder, and the risks they take on for fraud or non-payment by cardholders. Fees may also reflect administrative costs to issue the card and issuer costs for rewards that issuers offer to consumers who use the cards to make purchases.

[9]Merchants may work directly with either acquiring banks or payment processors.

[10]A merchant’s ability to add surcharges or convenience fees depends on applicable laws and network rules, according to literature we reviewed. See, e.g., Matthew C. Luzadder and Alla M. Taher, “The Changing Landscape of Interchange Fees and Surcharges,” The Review of Banking and Financial Services, vol. 40, no. 12 (Dec. 2024), 129-135; Tom Witherspoon and Audrey Carroll, “NY's Revamped Card Surcharge Ban Is Unique Among States,” Law360 (Feb. 2024).

[11]For purposes of this regulation, debit cards include general-use prepaid cards, among other things. See, e.g., 12 C.F.R. § 235.2(f). Interchange fees are any fees established, charged, or received by a payment card network and paid by a merchant or acquirer to compensate the issuer of the card for its involvement in an electronic debit transaction. See, e.g., 12 C.F.R. § 235.2(j). Note that entities that employ a three-party system—that is, where one entity acts as a systems operator, issuer and potentially acquirer—are not payment card networks for purposes of the rule. 12 C.F.R. app. A to pt. 235, commentary to § 235.2(m).

[12]Pub. L. No. 111-203, tit. X, § 1075(a)(2), 124 Stat. 1376, 2068-2074 (2010) (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1693o-2).

[13]Federal Reserve, Debit Card Interchange Fees and Routing, Final Rule, 76 Fed. Reg. 43,394 (July 20, 2011) (codified as amended at 12 C.F.R. pt. 235).

[14]12 C.F.R. § 235.3(b). Under Regulation II, electronic debit transaction means the use of a debit card by a person as a form of payment in the United States to initiate a debit to an account, but excludes transactions initiated at an ATM, including cash withdrawals and balance transfers initiated at an ATM. 12 C.F.R. § 235.2(h). A basis point is one-hundredth of 1 percent. Card issuers who meet certain fraud prevention standards can charge an additional $0.01 per transaction. The Federal Reserve developed the interchange fee cap in 2011, using data voluntarily reported by large debit card issuers for transactions performed in 2009. Since that time, the Federal Reserve has collected debit card transaction data on a mandatory basis every other year. In 2023, the Federal Reserve proposed lowering the interchange fee cap based on the latest data and making other changes to Regulation II. Federal Reserve, Debit Card Interchange Fees and Routing, Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 88 Fed. Reg. 78,100 (Nov. 14, 2023).

[15]An issuer is exempt if it holds the account being debited and, together with its affiliates, has assets of less than $10 billion. 15 U.S.C. § 1693o-2(a)(6); 12 C.F.R. § 235.5(a). The act and regulation also exempt debit cards issued under government-administered payment programs and certain reloadable prepaid cards, with some exceptions. 15 U.S.C. § 1693o-2(a)(7); 12 C.F.R. § 235.5(b)-(d).

[16]12 C.F.R. § 235.7(a), app. A to pt. 235, comment to § 235.7(a).

[17]12 C.F.R. § 235.7(b), app. A to pt. 235, comment to § 235.7(b).

[18]Separately, certain payment card networks and issuers have been the subject of ongoing antitrust litigation since 2005. See e.g. In re Payment Card Interchange Fee and Merchant Discount Antitrust Litigation, No. 1:05-md-01720 (E.D.N.Y.). The plaintiffs are merchants who allege that network interchange fees, and associated rules, are anticompetitive and violate federal and state antitrust laws. Effective in 2023, the defendants entered into a $5.6 billion settlement with a class of plaintiffs seeking monetary damages for past injury. The remaining class of plaintiffs—those seeking equitable relief—reached a proposed settlement with the defendants in 2024. The proposed settlement included reductions and caps on credit card interchange fee rates over several years, as well as various changes to network rules. See In re Payment Card Interchange Fee and Merchant Discount Antitrust Litigation, No. 1:05-md-01720, Doc. 9179-2 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 26, 2024). However, the court did not approve the proposed settlement.

[19]Congressional Research Service, Credit Card Swipe Fees and Routing Restrictions, R48216 (Oct. 8, 2024). See also GAO, Credit Cards: Rising Interchange Fees Have Increased Costs for Merchants, but Options for Reducing Fees Pose Challenges, GAO-10-45 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 19, 2009).

[20]The Credit Card Competition Act of 2023 was introduced in both chambers of Congress but neither bill was enacted by the end of the 118th Congress. S. 1838, H.R. 3881.

[21]This requirement would not apply to credit cards issued in a 3-party payment system model. The legislation defines a covered card issuer as a card issuer that, together with its affiliates, has assets of more than $100,000,000,000.

[22]Credit Card Competition Act of 2023, 169 Cong. Rec. S5843 (daily ed. Dec. 7, 2023) (statement of Sen. Durbin). See also Congressional Research Service, How the Credit Card Competition Act of 2023 Could Affect Consumers, Merchants, and Banks, IF12548 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 2023).

[23]Smithsonian officials told us they pay card acceptance fees from revenue-generating functions (such as sales) rather than federally appropriated funding. Military exchanges also rely on nonappropriated funding, such as sales revenue, to cover operating expenses.

[24]All references to GSA’s SmartPay Master Contract refer to the Conformed Generic Master Contract #GS-36F-GA00x thru Modification PO0021, (June 4, 2024). Eligible net charge volume refers to the portion of an entity’s charges that are eligible for refunds.

[25]As part of our literature review, we reviewed recently published industry publications, websites, and other news sources to find estimates of fees U.S. merchants paid to accept payment cards. We compiled information from these sources and, based on this review, we found that fees U.S. merchants paid could range from approximately 1.0 percent to 4.4 percent of transaction revenue. We did not independently validate these estimates. As we discuss later, the fees paid by entities vary, such as by type of card.

[26]As noted previously, the BFS Card Acquiring Service manages card acceptance for other federal entities. We estimated that 81 federal entities participated in the Card Acquiring Service as of February 2024. To estimate the number of entities that participate, we obtained information from BFS on the total number of accounts maintained by its financial agent (as of February 2024, accounts totaled 2,078). We then verified the entity names associated with each account against the list of federal entities in the Federal Register and individual entity websites.

[27]IRS does not participate in BFS’s Card Acquiring Service but does participate in Pay.gov for payments that IRS employees make to reimburse IRS under certain circumstances. According to IRS, the agency has statutory authority to contract for payment card acceptance services. Additionally, IRS is required to pass related transaction fees on to the taxpayer. See 26 U.S.C. § 6311; 26 C.F.R. § 301.6311-2.

[28]Debit card interchange fees are typically lower than those for credit cards also in part because debit card transactions withdraw money directly from a cardholder's bank account and therefore are less risky for card issuers than credit cards.

[29]A chargeback is a refund for a transaction provided to a cardholder when a customer disputes a debit or credit card transaction. The card issuer must determine whether to provide that cardholder with this refund.

[30]The International Organization for Standardization defines MCCs based on the types of goods and services sold by merchants. See https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:18245:ed-2:v1:en, accessed Oct. 3, 2024.

[31]See Mastercard 2023–2024 U.S. Region Interchange Programs and Rates (Apr. 14, 2023), https://www.mastercard.us/content/dam/public/mastercardcom/na/us/en/documents/merchant‑rates‑2023‑2024.pdf, accessed June 25, 2024, and Visa USA Interchange Reimbursement Fees (Oct. 14, 2023), https://usa.visa.com/content/dam/VCOM/download/merchants/visa‑usa‑interchange‑reimbursement‑fees.pdf, accessed April 19, 2024.

[32]Mastercard 2023–2024 U.S. Region Interchange Programs and Rates (Apr. 14, 2023); Visa USA Interchange Reimbursement Fees (Oct. 14, 2023).

[33]Some networks offer tiered interchange rates (based on transaction volume) for merchants in the supermarket MCC.

[34]Mastercard’s and Visa’s published interchange rates included tiered rates for merchants in certain merchant categories. For example, with respect to Mastercard, the minimum annual volume for its supermarket programs was $6 billion for Tier 1, $2 billion for Tier 2, and $750 million for Tier 3. Mastercard 2023–2024 U.S. Region Interchange Programs and Rates (Apr. 14, 2023). With respect to Visa, the minimum annual volume was $23.26 billion for Tier 0, $12.64 billion for Tier 1, $4.99 billion for Tier 2, and $1.13 billion for Tier 3. Visa also imposed other types of thresholds for each tier (for example, based on transaction count). Visa USA Interchange Reimbursement Fees (Oct. 14, 2024).

[35]Address verification can minimize the risk of fraudulent transactions by comparing the billing address provided by a consumer with the billing address on the account to confirm they match. Processors can also help entities implement secure processing technologies, such as point-to-point encryption or tokenization.

[36]See 26 U.S.C. § 6311; 26 C.F.R. § 301.6311-2. According to IRS, up to 3.5 percent of tax payments are paid with credit cards annually. IRS contracts with three companies to process card payments and collect related transaction fees directly from taxpayers. IRS evaluates the companies to ensure they meet performance standards and quality levels specified in the performance work statement.

[37]10 U.S.C. § 1065; 32 C.F.R. pt. 225. The user fee is in addition to a uniform surcharge imposed under other statutory provisions. See 10 U.S.C. § 2484(d).

[38]For example, IRS awards contracts through the Federal Acquisition Regulation system, which establishes a uniform set of policies and procedures for acquisition by executive branch agencies. This system consists of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), which is the primary document, and agency acquisition regulations that implement or supplement the FAR. However, we previously reported that certain federal entities, contracts, and agreements are not expressly subject to the FAR, including USPS, Amtrak, DOD military exchanges, Treasury’s financial agency agreements, and Smithsonian contracts which do not involve federal funds. GAO, U.S. Postal Service: Purchasing Changes Seem Promising, but Ombudsman Revisions and Continued Oversight Are Needed, GAO‑06‑190 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 15, 2005), 2; Amtrak Management: Systemic Problems Require Actions to Improve Efficiency, Effectiveness, and Accountability, GAO‑06‑145 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 4, 2005), 36; Forced Labor: Actions Needed to Better Prevent the Availability of At-Risk Goods in DOD’s Commissaries and Exchanges, GAO‑22‑105056 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 3, 2022), 10–11; Revenue Collections And Payments: Treasury Has Used Financial Agents in Evolving Ways but Could Improve Transparency, GAO‑17‑176 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 25, 2017), 4; Smithsonian Institution: Additional Information Should Be Developed and Provided to Filmmakers on the Impact of the Showtime Contract, GAO‑07‑275 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 15, 2006), 3. As a result, the policies and procedures used by some federal entities in this review may differ.

[39]For example, published network rules we reviewed were over 400 pages.

[40]Navy Exchange Service Command Chief Audit Executive, Credit Card Processing and Related Financial Systems Audit (13-10). The report found that in addition to card and assessment fees, the Navy Exchange Service Command was charged 49 other types of fees, accounting for approximately 93 percent of total credit card processing fees in FY 2013. See also Army and Air Force Exchange Service, Report of Audit, Credit and Debit Card Receivables, No. 2015-10 (Jan. 2016). This report identified cost-saving opportunities but highlighted difficulties in reconciling fees due to insufficiently detailed processor data.

[41]Officials from both entities stated they review processor invoices to confirm the accuracy and consistency with previously established rates. Upon verification, payment is made.

[42]Card networks have negotiated reduced interchange rates with some public sector entities, including California’s public transit system. See, for example, Ken Burgess, “Avoiding the Interchange Squeeze,” Mobility Payments Intelligence Report (Jan. 18, 2023). https://www.mobility‑payments.com/2023/01/18/avoiding‑the‑interchange‑squeeze/, accessed May 24, 2024. For additional information about public transit challenges with payment card fees, see Aaron Klein, How Better Payment Systems Can Improve Public Transportation (Brookings Institution: Jan. 2023).

[43]As noted previously, costs of accepting cards include software for network infrastructure, fraud prevention measures, and processing; hardware for processing; and point-of-sale card terminal rentals.

[44]IRS also contributed perspectives on the benefits of payment cards.

[45]See for example, National Park Service, April 12, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/deva/learn/news/cashless.htm. Accessed September 12, 2024. The park service participates in the BFS Card Acquiring Service.

[47]As of April 2024, approximately 115 federal entities held accounts with one or both of the banks under the GSA SmartPay program, including the 24 entities named in the Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-576, tit. II, § 205(a), 104 Stat. 2838, 2842 (codified as amended at 31 U.S.C. § 901). The act established chief financial officers to oversee financial management activities at 24 major executive departments and agencies. The entities are often referred to collectively as Chief Financial Officers Act agencies. They consist of the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, the Interior, Justice, Labor, State, Transportation, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs; the Environmental Protection Agency; GSA; National Aeronautics and Space Administration; National Science Foundation; Nuclear Regulatory Commission; Office of Personnel Management; Small Business Administration; Social Security Administration; and Agency for International Development. In addition to federal entities, Tribes and tribal organizations participate in GSA SmartPay.

[48]GSA awarded a master contract to two banks, which issue charge cards and provide other payment solutions to the entities that participate in the GSA SmartPay program. The master contract defines charge card as similar to a credit card, except that there is no line of credit established and the balance owed is due and payable in full upon receipt of the billing statement. GSA is compensated through a percentage-based fee deducted from the refunds that the banks return to the entities.

[49]The entities we reviewed that use payment cards are Treasury, USPS, Amtrak, the three DOD NAFIs, Defense Commissary Agency, Smithsonian, IRS, and GSA. Most entities participate in SmartPay. Some entities, such as DOD and Amtrak, also reported using charge card programs in addition to or instead of SmartPay. For example, two DOD NAFIs issue cards for purchase and travel through other banks. Amtrak officials reported using multiple charge card programs, including GSA SmartPay, for crew lodging and other purposes, some of which earn rewards similar to GSA SmartPay. Amtrak also uses a single-use card payment system for vendors, in addition to automated clearing house and wire check payments.

[50]Entities may refer to these refunds as rebates or cash back. According to the GSA SmartPay master contract, the refunds may include additional payments from the contractor to the agency to correct improper or erroneous refund payments or make an invoice adjustment. GSA officials distinguished refunds from rebates, describing the latter as commercially available offers.

[51]According to GSA documentation, GSA negotiates minimum refund rates with the banks that issue the payment cards based on spending volume and timeliness of payment. Each entity negotiates its refund rate in task orders with the issuing banks so refund rates vary. Office of Management and Budget Circular A-123, Appendix B, states that unless specific authority exists allowing refunds to be used for other purposes, refunds must be returned to the appropriation or account from which they were expended and can be used for any legitimate purchase by the appropriation or account to which they are returned, or as otherwise authorized by statute. (Aug. 2019).

[52]Eligible employees under USPS are issued uniform allowance purchase cards to purchase approved uniform items.

[53]According to GSA officials, another benefit of the GSA SmartPay program is the ability to leverage commercial systems and practices under FAR part 12, such as account management, reporting, and data mining systems. In addition, banks are required to provide training to agency employees in groups of 20 or more.

[54]Imprest funds are fixed-cash or petty-cash funds in the form of currency or coin that have been advanced to a cashier as "Funds Held Outside of the Department of the Treasury."

[55]Our literature review and interviews with subject matter experts identified limited research on the quantitative benefits to federal entities of offering payment cards to employees. We identified a series of surveys that were conducted between 2014 and 2022 of private and public sector card issuers. See Richard J. Palmer and Mahendra Gupta, The 2014 Purchasing Card Benchmark Survey Report (2014) and Richard J. Palmer and Mahendra Gupta, The 2017 Purchasing Card Benchmark Survey Report (2017). See also Richard J. Palmer, Mahendra Gupta, and James Brandt, “Implementing card technology in government: different approaches, different outcomes,” Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, vol. 16, no. 1 (2022): 51–67. Based on results of these surveys and others, GSA estimated over $1.34 billion in administrative cost savings for FY 2022 from using cards instead of purchase orders. GSA officials said they were considering updating this estimate. We were not able to validate the methodology used for these estimates.

[56]For example, Government Charge Card Abuse Prevention Act of 2012, Pub. L. No. 112-194, 126 Stat. 1445; Office of Management and Budget, Implementation of the Government Charge Card Abuse Prevention Act of 2012, M-13-21 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2013), 1. Requirements may differ by agency or card type.

[57]In 2017, we reviewed GSA and selected other agencies’ purchase card programs. We did not find evidence of fraud or improper payments but recommended that GSA reemphasize OMB guidance to obtain and retain complete documentation of micropurchases. GSA implemented this recommendation. We also recommended that the Department of the Interior reexamine its card program to require cardholders to document purchase request and preapproval for self-generated purchases for purchase card transactions. Interior stated it did not plan to take action on this recommendation and therefore we closed the recommendation as not implemented. GAO, Government Purchase Cards: Little Evidence of Potential Fraud Found in Small Purchases, but Documentation Issues Exist, GAO‑17‑276 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 14, 2017). After we provided GSA with the official draft of this report, GSA released a statement describing certain actions it took to mitigate risk and improve oversight of the GSA SmartPay program. This included reducing card limits, instituting a review and approval process for future purchases, and looking into instances of fraud and abuse. GSA also asked certain other agencies participating in the GSA SmartPay program to reduce card limits and the number and usage of cards. GSA, Statement regarding recent reporting about the GSA SmartPay® program, Feb. 21, 2025, available at https://www.gsa.gov/about-us/newsroom/news-releases/statement-regarding-recent-reporting-about-the-gsa-smartpayr-program-02212025, accessed Apr. 16, 2025.

[58]Under the GSA SmartPay master contract, the issuing banks provide charge cards with specific account numbers that are only recognized by the City Pair Program.