COMMERCIAL SHIPBUILDING

Maritime Administration Needs to Improve Financial Assistance Programs

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Andrew Von Ah at VonAha@gao.gov .

Highlights of GAO-25-107304, a report to congressional committees

Maritime Administration Needs to Improve Financial Assistance Programs

Why GAO Did This Study

Concerns over the state of U.S. commercial shipbuilding have grown in recent years. Such concerns are particularly related to the nation’s capacity to meet government shipbuilding and repair needs that are critical to national defense.

The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 includes a provision for GAO to review efforts to support the U.S. commercial maritime industry. This report addresses, among other topics, (1) the use of the Maritime Administration’s programs to encourage or improve U.S. shipbuilding and the extent to which they follow leading practices and (2) ideas identified by selected stakeholders to address challenges facing the maritime industry.

GAO reviewed Maritime Administration documents and compared its four financial assistance programs with leading practices for performance management. GAO also surveyed domestic vessel owners and operators and shipbuilding or repair companies. GAO also visited selected shipyards and interviewed government officials and 31 industry stakeholders selected to provide a range of perspectives on the Maritime Administration’s programs and the maritime industry’s ability to contribute to national defense.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations, including that the Maritime Administration develop measurable goals for, and assess the performance of, its four financial assistance programs.

DOT agreed with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

Under coastwise laws, U.S. vessel owners and operators engaged in domestic trade generally must use U.S.-built vessels. The construction of vessels in U.S. shipyards helps to support the U.S. maritime industry, which plays a vital role in national defense.

Because U.S.-built vessels generally cost more than foreign-built ones, the Maritime Administration has four financial assistance programs to encourage or improve U.S. shipbuilding. The Federal Ship Financing Program generally offers loan guarantees for vessel construction at U.S. shipyards. In the last 5 years, the program executed two loan guarantees for two vessel owners totaling nearly $400 million. The two tax deferral programs, the Construction Reserve Fund Program and the Capital Construction Fund Program, allow vessel owners or operators to defer paying tax on certain eligible deposits that are placed into an account and can be used to fund projects at U.S. shipyards. In 2024, seven vessel owners or operators had a Construction Reserve Fund program account, and 137 vessel owners or operators had a Capital Construction Fund Program account. Finally, the Small Shipyard Grant program provides grants to small shipyards for equipment or training. In fiscal year 2024, this program had $8.75 million in available funds and had 78 grant applications from shipbuilding or repair companies requesting just under $50 million.

These four financial assistance programs have provided some support for vessel owners or operators and shipyards, but the programs’ administration does not follow leading practices for assessing program performance. For example, the Maritime Administration cannot determine to what extent the programs are effective in growing the U.S. maritime fleet because it has not established measurable goals for, or assessed the performance of, these programs. Doing so would allow the Maritime Administration to identify any changes that could better increase the nation’s shipbuilding capacity to promote national security and economic prosperity. An April 2025 Executive Order established United States policy to revitalize and rebuild domestic shipbuilding and requires certain actions to grow the U.S. maritime fleet.

In addition, the 31 industry stakeholders GAO interviewed identified challenges facing vessel owners or operators and shipyards competing within the U.S. domestic maritime industry. They also had ideas to address those challenges (see table).

|

Challenge |

Ideas |

|

Domestic vessel owners or operators face competition with other modes of transportation, such as trucks. |

Encourage the use of domestic vessels to carry cargo along rivers or between coastal ports. |

|

Shipyards face workforce challenges from “boom-and-bust” cycles created by fluctuating demand for new vessel construction. |

Smooth the workflow through economies of scale, such as through large, consistent federal vessel procurements. |

|

Shipyards face challenges with aging infrastructure. |

Expand the Small Shipyard Grant program, and encourage foreign investment. |

Source: GAO analysis of 31 stakeholders’ statements. | GAO-25-107304

Abbreviations

CBP U.S. Customs and Border Protection

DOD U.S. Department of Defense

DOT U.S. Department of Transportation

FY2023 NDAA James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023

NSS Canada’s National Shipbuilding Strategy

OMB Office of Management and Budget

U.K. United Kingdom

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 30, 2025

The Honorable Ted Cruz

Chairman

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Ranking Member

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

U.S. federal policy has long held that a strong U.S. maritime industry is critical to national defense and that it should be capable of carrying the substantial portion of its foreign and domestic commerce and serving as a naval or military auxiliary in time of war or national emergency.[1] Private shipyards, which may construct commercial or government vessels, including military vessels, are one segment of the U.S. maritime industry. However, concerns over the status of U.S. commercial shipbuilding have grown in recent years, particularly in light of China’s dominance in commercial shipbuilding and the difficulty U.S. private shipyards have had competing in global markets.[2] For example, in 2019, the Administrator of the Maritime Administration testified before Congress that the successful, multidecade industrial policies of the principal shipbuilding nations—China, Korea, and Japan—had virtually eliminated the ability for U.S. shipyards to compete in the global market.[3] In a 2023 speech, the Secretary of the Navy stated that the growth of China’s commercial maritime power was a development more concerning than even its naval expansion.

In 2024, the Navy issued a shipbuilding plan articulating a whole-of-government effort to rebuild the comprehensive maritime power of the nation, which seeks to reverse decades of decline in the commercial, as well as the naval shipbuilding industries.[4] More recently, proposed legislation designed to help revitalize the U.S. maritime industry, including U.S. shipyards, has been introduced in both the current and previous sessions of Congress.[5] In addition, in March 2025, during a joint address to Congress, President Trump announced the creation of a new Office of Maritime and Industrial Capacity at the National Security Council in the White House. An April 2025, Executive Order requires, among other things, various actions designed to strengthen America’s shipbuilding capabilities and grow the U.S. maritime fleet.[6]

The Navy and other government agencies rely in large part on the capability and capacity that private shipyards provide to support their shipbuilding and repair efforts.[7] Seven private shipyards generally build major ships for the Navy.[8] Beyond these seven shipbuilding companies, private shipbuilding or repair companies in the United States may work on a mix of military, other government, and commercial vessels. This report focuses on these other private shipbuilding or repair companies.

Much of the work that sustains these private shipbuilding or repair companies—and, in turn, the overall capacity the nation has to support military and other government shipbuilding and repair needs—comes from U.S. commercial vessel owners or operators involved in domestic commerce.[9] (For more information on current activities at U.S. commercial shipyards, see app. I). These owners or operators involved in specified domestic activities in the United States generally must use vessels built in U.S. shipyards. For example, the law commonly referred to as the Jones Act,[10] and related coastwise laws,[11] collectively require that vessels involved in the domestic maritime transportation of merchandise be owned by U.S. citizens, registered under the U.S. flag, and built in the United States.[12]

To support the commercial maritime industry, the Maritime Administration manages three financial assistance programs to support domestic vessel owners’ or operators’ efforts to build or repair vessels in U.S. shipyards. It also manages the Small Shipyard Grant program, which provides grants to small shipyards to make capital improvements or develop workforce training programs. The Maritime Administration also led the development of the current National Maritime Strategy, publishing Goals and Objectives for a Stronger Maritime Nation in 2020.[13] The Maritime Administration is working on a new strategy that was mandated in the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 (FY2023 NDAA).[14]

The FY2023 NDAA includes a provision for us to review efforts to expand and modernize the commercial U.S. maritime industry, with a focus on the Maritime Administration’s programs to support shipbuilding.[15] This report addresses (1) the use of the Maritime Administration’s programs to support domestic vessel owners or operators and the extent to which these programs follow selected leading practices for assessing program performance; (2) the use of the Small Shipyard Grant program and the extent to which this program follows federal guidance and selected leading practices for assessing program performance; and (3) ideas identified by selected stakeholders to help address challenges in the maritime industry, and perspectives of government officials and shipyard representatives in selected other countries.

To support all three objectives, we interviewed 20 U.S. stakeholders, including shipyards, vessel owners or operators, and industry associations selected to provide a range of perspectives on the Maritime Administration’s financial assistance programs and ideas to address challenges facing the maritime industry. In addition, as part of our work on the surveys described below, we conducted survey pretests with four additional shipyards and seven additional owners or operators and included relevant information from those pretests, as appropriate. In total, we interviewed 31 stakeholders.

To determine the use of the Maritime Administration’s programs to support domestic vessel owners or operators, and the extent to which the programs follow selected leading practices for assessing program performance, we reviewed relevant laws and statutes, program documents on the implementation of the three financial assistance programs, and application and program data and information from 2020 through 2024. To assess the reliability of these programs’ data, we interviewed Maritime Administration officials responsible for implementing these programs and discussed the accuracy and completeness of the program data. We determined that the data were reliable for the purposes of describing existing information the Maritime Administration has collected on these programs. We interviewed Maritime Administration officials responsible for implementing these programs, officials from the Internal Revenue Service responsible for oversight of the Capital Construction Fund Program and the Construction Reserve Fund Program, and officials from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) responsible for reviewing the Maritime Administration’s review of applications for the Federal Ship Financing Program. We compared the Maritime Administration’s implementation of these programs with selected practices identified in our prior work to help manage and assess the results of federal efforts—specifically that agencies should establish measurable goals to be able to track progress toward achieving those goals.[16]

For both the first and third objectives, we conducted a nongeneralizable survey of domestic vessel owners or operators to obtain information on their use of, and experiences with, the three Maritime Administration programs listed above and ideas to address challenges within the maritime industry. We received responses to our owner/operator survey from 34 domestic vessel owners or operators representing different segments of the maritime industry. Because domestic vessel owners or operators completing the survey may not all have experience with the Maritime Administration’s financial assistance programs, the number of responses to each question in the owner/operator survey may be different.

To determine use of the Small Shipyard Grant program and the extent to which it follows federal regulations, guidance, and leading practices for assessing program performance, we reviewed program documents, data, and applications for fiscal years 2020 through 2024. To assess the reliability of these program data, we interviewed Maritime Administration officials responsible for implementing these programs and discussed the accuracy and completeness of the program data. We determined the data were reliable for the purposes of describing program use and analyzing the Maritime Administration’s management of this program. We visited eight private U.S. shipyards that generally work on commercial vessels to discuss the challenges they face, as well as their experiences with the Maritime Administration’s Small Shipyard Grant program. We selected these shipyards to ensure a variety of regions, yard capability and size, and to include some that did and did not receive a Small Shipyard Grant. We compared the Maritime Administration’s implementation of this program with OMB regulations and the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Guide to Financial Assistance.[17] We also compared the Maritime Administration’s implementation of this program with practices identified in our prior work to help manage and assess the results of federal efforts—specifically that agencies should establish measurable goals to be able to track progress toward achieving those goals.[18]

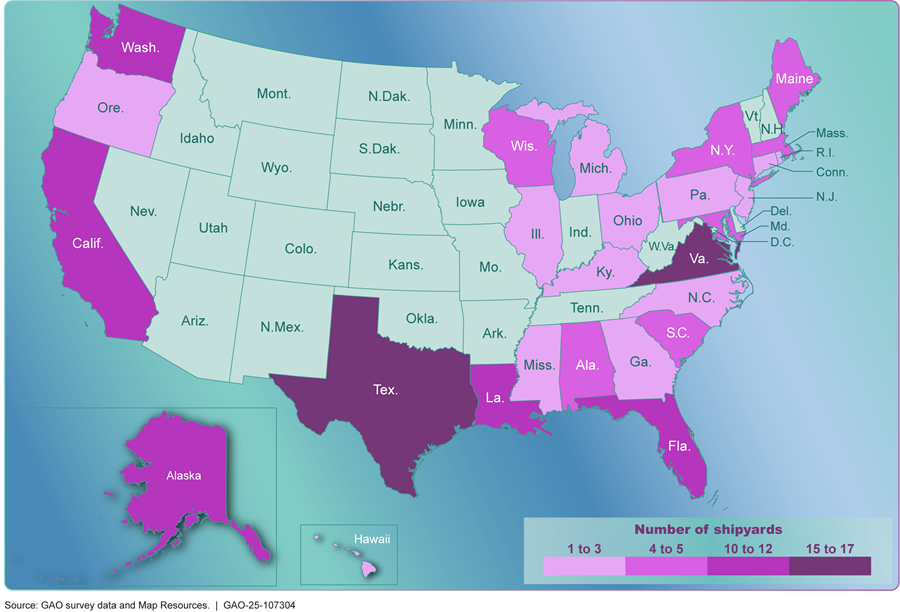

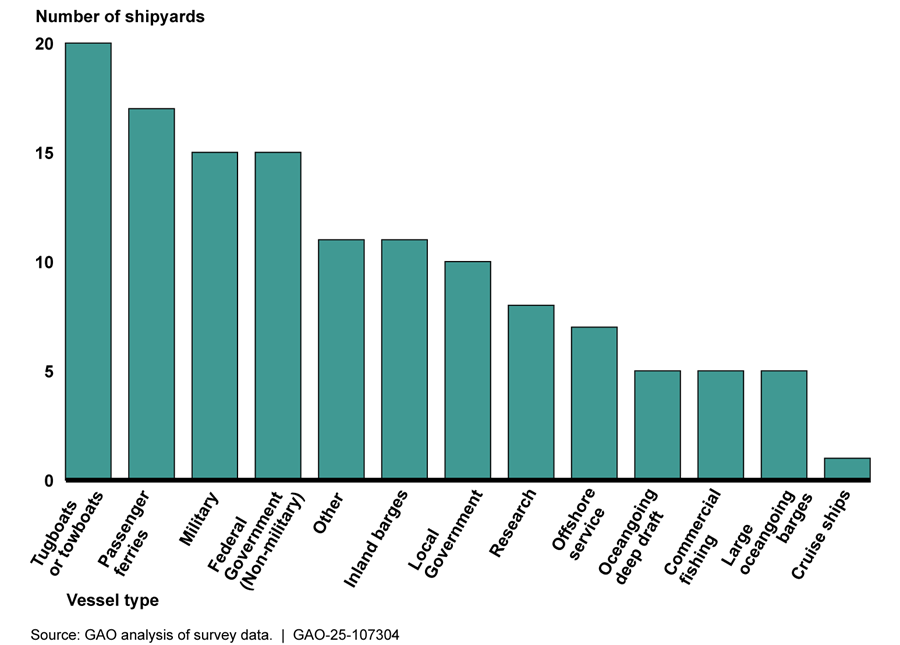

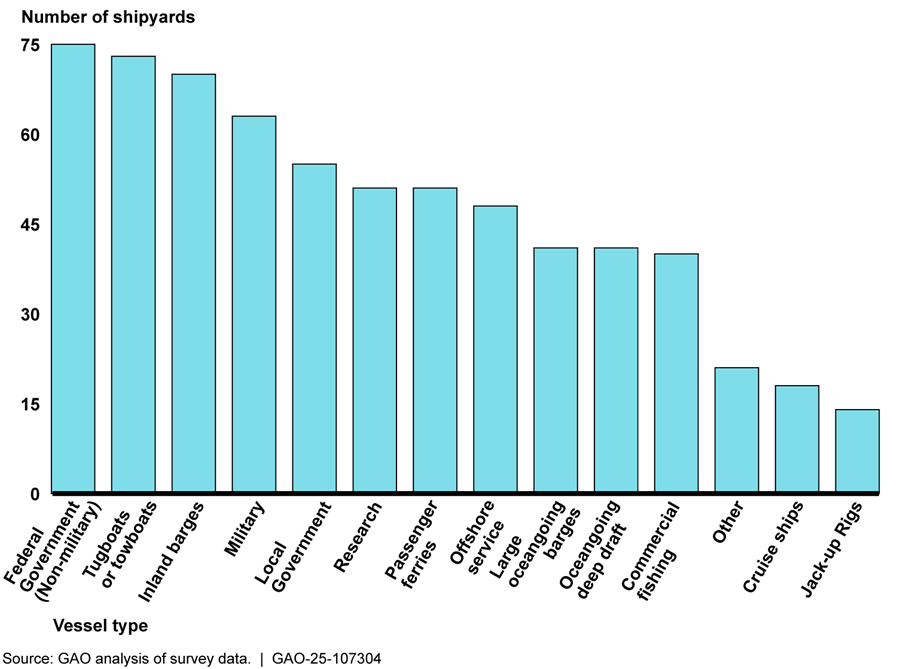

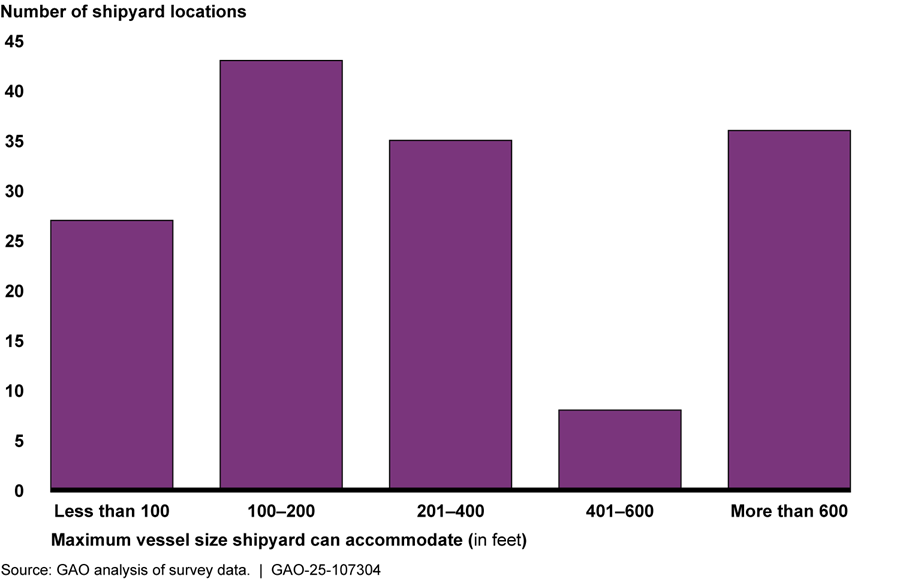

For both the second and third objectives, we conducted a nongeneralizable survey of private shipbuilding or repair companies to obtain information on their activities; their use of, and experiences with, the Small Shipyard Grant program; and challenges. We received responses to our survey from 105 shipbuilding or repair companies located across the contiguous United States and Alaska and Hawaii.

During our interviews with the 31 domestic stakeholders described above, we gathered ideas to help address challenges in the maritime industry. In addition, we interviewed officials in a nongeneralizable selection of four countries: South Korea, Singapore, the United Kingdom (U.K.), and Canada to represent a variety of shipbuilding capacities and strategies. The information we obtained from these countries is not generalizable but provides examples of the shipbuilding experiences and policies of different countries. The ideas identified by stakeholders to help address challenges in the maritime industry provide broad information for future consideration. The ideas are not listed in any specific order, and we are not suggesting that they be done individually or combined. Additionally, it was not within the scope of our review to assess how effective the ideas may be. We also express no view regarding the extent to which legislative changes might be needed to implement them. See appendix II for more information about our scope and methodology, including our two surveys.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

U.S. Maritime Industry and Shipbuilding and Repair

The U.S. commercial maritime industry includes owners and operators of vessels registered under the U.S. flag, private U.S. shipyards, and other supporting industries.[19] U.S. flag vessels can operate domestically or in international trade.[20] Unlike U.S.-flag vessels operating in most domestic activities, U.S.-flag vessels operating in international trade do not have to be built in the United States,[21] although they have to follow other requirements of U.S. flag vessels such as that they be crewed largely with U.S. citizens.[22]

The Jones Act and related coastwise laws serve to establish the parameters of the U.S. domestic shipping and shipbuilding market.[23] They do so largely through the requirements that such vessels must be U.S. flagged, U.S. owned, U.S. crewed, and U.S. built. These requirements create a closed market for domestic vessels operating in many domestic activities. For example, these vessels carry cargo from California to Hawaii, transport crew and supplies related to the domestic oil or offshore wind industries, dredge sediment from U.S. ports or perform beach nourishment services to mitigate erosion, and transport passengers between U.S. points. According to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, there were more than 40,000 U.S.-flag vessels engaged in domestic trade in 2022.[24]

The requirement that vessels engaged in domestic trade be built in the United States is intended to help ensure that there is a market for shipbuilding and repair at U.S. private shipyards. According to Maritime Administration officials, as of February 2025, there were 145 private shipyards engaged in shipbuilding and over 300 shipyards engaged in ship repair. However, despite the U.S. shipbuilding requirement of the Jones Act and related coastwise laws, concerns have been raised that the United States does not have adequate shipbuilding capacity and capability to meet national security needs.[25] According to the Department of Defense (DOD), in 2021, there were roughly 25 U.S. shipyards capable of constructing medium-to-large-sized vessels;[26] the other U.S. shipyards either construct smaller vessels or do only repairs (see app. I for the results of our survey of shipyards). Most shipbuilding in U.S. shipyards is done for commercial domestic vessel owners or operators or for U.S. government agencies, such as the Navy, Coast Guard, and Maritime Administration.[27]

Generally, U.S. shipyards are unable to effectively compete for commercial vessel orders internationally because the cost to construct and repair vessels at U.S. shipyards is higher than at foreign shipyards due to higher labor costs and lack of economies of scale, among other reasons.[28] In addition, in January 2025, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative published the results of an investigation that found that China’s targeting of the shipbuilding sector for dominance was “unreasonable.” [29] China’s tactics included government subsidies and what the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s report described as unfair labor practices. As a result, according to this report, China’s tactics had severely disadvantaged U.S. companies, workers, and the U.S. economy by undercutting business opportunities for, and investments in, the U.S. maritime, logistics, and shipbuilding and repair sectors.

Roles of Federal Agencies

The Maritime Administration within DOT is responsible for promoting U.S. shipbuilding and repair services for domestic and international commerce and national defense. To support this mission, the Maritime Administration administers four financial assistance programs for U.S. vessel owners or operators and U.S. shipyards—two tax deferral programs, a loan guarantee program, and a grant program.[30] The collective purposes of the programs are to encourage U.S. vessel owners or operators to construct or reconstruct vessels at U.S. shipyards and assist U.S. shipyards’ modernization efforts.

Tax deferral programs. The Maritime Administration administers two different tax deferral programs for vessel owners or operators: the Capital Construction Fund Program and the Construction Reserve Fund Program. These programs allow vessel owners or operators to defer paying tax on certain eligible deposits and earnings that can later be used to fund projects at U.S. shipyards.[31] For example, vessel owners or operators could defer paying tax on the gains attributable to the sale of a vessel that are deposited into a fund account for future vessel construction or reconstruction at a U.S. shipyard.

To open a Capital Construction Fund Program account or a Construction Reserve Fund Program account, vessel owners or operators submit an application to the Maritime Administration.[32] Once approved, vessel owners or operators become fundholders and can deposit funds from eligible transactions into the account.[33] To withdraw funds, fundholders must allocate the funds to an eligible project, such as the construction of a new vessel, within 3 years for a Construction Reserve Fund Program account and up to 25 years for a Capital Construction Fund Program account.[34] The Internal Revenue Service oversees tax rules applicable to these two tax deferral programs under their general administration and enforcement of federal tax law, according to Internal Revenue Service officials.

Loan guarantee program. The Federal Ship Financing Program provides loan guarantees to vessel owners for vessel construction or reconstruction projects at U.S. shipyards and to U.S. shipyards for shipyard modernization projects. According to the Maritime Administration, the intended benefits of the loan guarantee program are long repayment terms (up to 25 years), below market interest rates, and up to 87.5 percent project financing. The Maritime Administration reviews applications to the Federal Ship Financing Program in coordination with an independent financial advisor and other federal entities, including the Office of Management and Budget.[35] Federal Ship Financing Program loan guarantees are financed by the program’s designated preferred lender, the Federal Financing Bank, which is a federal corporation supervised by the Secretary of the Treasury. The Maritime Administration is responsible for monitoring the successful repayment of the loan.

Grant program. The Small Shipyard Grant program provides grants to individual U.S. shipyards with no more than 1,200 employees to partially fund specified types of capital improvement projects, such as certain upgraded equipment purchases or specified types of training programs.[36] The Maritime Administration accepts applications to the Small Shipyard Grant program once a year, announcing the deadline on its website. The Maritime Administration’s process is to evaluate applications for, among other things, alignment with statutory merit criteria and selection considerations based on departmental priorities. Subject matter experts conduct technical reviews prior to senior review team reviews and Maritime Administrator award decisions, according to the program’s 2024 Notice of Funding Opportunity.[37]

Other federal agencies also have roles in supporting and enforcing U.S. maritime policies. For example:

· The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency is responsible for enforcing and administering laws and regulations pertaining to the Jones Act and other coastwise laws.

· The U.S. Coast Guard is the primary agency for enforcing maritime laws and regulations including with respect to U.S.-flag vessels and, among other agencies, is tasked with the development and enforcement of standards to ensure maritime safety, security, and environmental protection. Additionally, the U.S. Coast Guard administers and enforces documentation requirements for the U.S.-flag registry (e.g., determining whether vessels meet U.S.-ownership and build requirements). This registry is used for determining a vessel’s eligibility for use in coastwise trade subject to the Jones Act and other coastwise laws.

· The Department of Defense supports U.S. maritime policy in a number of ways, such as by relying in large part on U.S.-flag commercial vessels to provide sealift in times of peace, crisis, and war; and by relying on private shipbuilding and repair companies to build and, in many cases, repair its ships.[38] According to U.S. Navy officials, the Navy’s Maritime Industrial Base program is working on a study of the state of the maritime industry as a whole for future potential Navy needs. The study will consider the capacity and capability of both large and smaller private shipyards that support ship construction and maintenance for the Navy. According to Navy officials, the smaller shipyards have the ability to play a major supporting role for the defense industrial base by constructing subcomponents of larger vessels.[39]

National Maritime Strategy

DOT has been required by several statutes to produce a national maritime strategy in coordination with other federal stakeholders.[40] To meet such a requirement from 2014, in 2020, DOT issued a National Maritime Strategy in the form of a report to Congress.[41] The strategy included a goal to strengthen U.S. maritime capabilities essential to national security and economic prosperity. In 2018, we had reported that a National Maritime Strategy was needed to prioritize increasing U.S.-flag vessels’ competitiveness and address other maritime challenges.[42]

The FY2023 NDAA directed the Secretary of Transportation to commission a study to inform a new National Maritime Strategy and then develop a new strategy.[43] It also directed the Secretary of Transportation to submit this strategy to Congress no later than 6 months after it received the study. Among other things, the act specifies that the new strategy should include recommendations to increase the use of short-sea shipping (i.e., transporting goods by sea, river, or lake over short distances instead of by truck or rail) and enhance U.S. shipbuilding capability. The Maritime Administration selected the Center for Naval Analyses to conduct the required study in September 2023; as of May 2025, the study had not been published.

In addition, an April 2025 Executive Order relating to strengthening the commercial shipbuilding capacity and maritime workforce of the U.S. requires the Maritime Administration, in coordination with other agencies, to complete additional reviews and reports on the state of the U.S. maritime industry.[44] These requirements include delivery of a Report on Maritime Industry Needs summarizing current policies and programs that support the maritime industry and potential other means of support, and a Review of Shipbuilding for U.S. government use, and recommendations to increase U.S. shipbuilding.

Maritime Administration’s Vessel Owner or Operator Programs Provide Some Support but Do Not Have Measurable Goals for Assessing Performance and May Be Duplicative

Vessel Owners or Operators Have Made Varied Levels of Use of the Maritime Administration’s Financial Assistance Programs

Vessel owners or operators have made varied levels of use of the Maritime Administration’s three financial assistance programs to construct vessels at U.S. shipyards. These programs, the Capital Construction Fund Program, the Construction Reserve Fund Program, and the Federal Ship Financing Program, were each established under the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, as amended.[45] The purpose of the programs is to encourage vessel owners or operators to construct or reconstruct vessels at U.S. shipyards. According to Maritime Administration officials, vessel construction at U.S. shipyards has increased in recent years, from 600 vessels constructed in 2020 to 925 vessels constructed in 2024.

Capital Construction Fund Program. As of 2024, the Capital Construction Fund Program had 137 vessel owners or operators participating in the program as fundholders. Eligibility for the Capital Construction Fund Program was recently expanded and, according to Maritime Administration officials, program use has increased. Previously, the stated allowable purpose of a Capital Construction Fund was restricted to the construction, acquisition, or reconstruction of U.S.-flag, U.S.-built vessels engaged in foreign trade or certain specified types of domestic trade (i.e., Great Lakes, noncontiguous domestic, or short-sea transportation). This specified type of domestic trading restriction was removed by statutory amendment in December 2022, expanding the allowable purpose to vessels engaged in the foreign or domestic trade of the United States.[46] According to Maritime Administration officials, after the eligibility expansion, the number of new applicants to the Capital Construction Fund Program increased nearly tenfold, from three in 2022 to 29 in 2023. In 2020 and 2021, before the eligibility expansion, the program had zero new applicants. From 2020 through 2023, fundholders deposited $675 million into Capital Construction Fund Program accounts, according to information provided by the Maritime Administration. At the end of 2023, fundholders had an accumulation of nearly $2.5 billion that could be withdrawn to construct or reconstruct vessels at U.S. shipyards.

Construction Reserve Fund Program. The Construction Reserve Fund Program is not a heavily utilized program, according to Maritime Administration officials. The most recent year a new Construction Reserve account was opened was 2013, according to Maritime Administration officials. In 2024, seven vessel owners or operators had open accounts and, according to Maritime Administration officials, two of those seven fundholders regularly used their Construction Reserve Fund account. However, Maritime Administration officials said that the fundholders who regularly use the program have a high number of vessels in their fleets that are eligible for the program.

Federal Ship Financing Program. The Federal Ship Financing Program is a low-volume program but has a high impact, according to Maritime Administration officials. In the last 5 years, the Federal Ship Financing Program received 12 new applications and executed two loan guarantees for two vessel owners, totaling nearly $400 million, according to information provided by the Maritime Administration.[47] The two loan guarantees are intended to fund construction of 22 new vessels, including towboats, barges, and containerships, at four U.S. shipyards. In the last 5 years, the Federal Ship Financing Program has not funded any vessel reconstruction projects.[48] As of January 2025, five vessel owners had pending applications that Maritime Administration officials were reviewing, according to the Maritime Administration website.[49] Projects in those applications propose constructing nine vessels, including offshore crew transfer, service, and installation vessels and containerships, at five different U.S. shipyards.

Domestic vessel owners or operators who completed our owner/operator survey, and stakeholders we spoke to who commented on these three Maritime Administration programs, provided their perspectives on program use. Of the 34 domestic vessel owners or operators that completed our survey, four reported using a Maritime Administration financial assistance program to construct a new vessel in the last 10 years. An additional 17 reported that they had constructed a new vessel in the past 10 years without the assistance of a Maritime Administration financial assistance program. In addition, 19 of the 34 owners or operators that took our survey responded that they had reconstructed a vessel in the past 10 years, and three of those 19 stated that they had used a Maritime Administration financial assistance program. Owner/operator survey respondents reported mixed opinions on their ability to complete a project, such as constructing a vessel, if they were not able to obtain Maritime Administration financial assistance.[50]

Of the 34 owner/operator survey respondents who completed our survey, 23 said they did not currently have a Capital Construction Fund Program account, 31 said they did not currently have a Construction Reserve Fund account, and 30 said they had not applied for a Federal Ship Financing Program loan guarantee in the past 5 years.[51] These survey respondents provided different reasons for why they were not using a Maritime Administration financial assistance program, as follows:

· Not aware of programs. Of the survey respondents who were not currently or recently using one of the financial assistance programs, some were not aware that the three programs existed. Specifically, five respondents were unaware of the Capital Construction Fund Program, 14 were unaware of the Construction Reserve Fund Program account, and seven were unaware of the Federal Ship Financing Program. According to Maritime Administration officials, they are working to make vessel owners or operators more aware of these programs and the potential benefits the programs can provide by engaging with maritime stakeholders at maritime conferences and events. For example, according to Maritime Administration officials, their greatest outreach effort to promote these programs is at WorkBoat, a wide-reaching annual maritime industry conference. The Maritime Administration also provides comprehensive information about the programs on their website.

· Not eligible for the Capital Construction Fund Program. Six of the 23 survey respondents that did not currently have a Capital Construction Fund Program account thought they were not eligible for the program. As mentioned above, the allowable domestic purposes of a vessel with respect to this program was recently expanded by statutory amendment. Domestic vessel owners or operators that operate in U.S. inland waters are a segment of the industry that is likely now eligible to a larger extent for the program due to the recent change. According to a maritime industry association representative we interviewed that represents domestic vessel owners or operators that operate in U.S. inland waterways, the association was not aware of any of their members using the Capital Construction Fund Program. According to Maritime Administration officials, making vessel owners or operators aware they are potentially now eligible for this program is part of the Maritime Administration’s efforts to make more vessel owners or operators aware of all of the financial assistance programs. For example, according to Maritime Administration officials, they gave a presentation on the expanded eligibility of the Capital Construction Fund at the Inland Marine Expo in May 2024, which is a conference for the inland and intracoastal marine industry.

· Federal Ship Financing Program application too challenging. Seven of the 30 survey respondents that had not applied within the past 5 years to the Federal Ship Financing Program considered the application to be too challenging. To apply for a loan guarantee through the Federal Ship Financing Program, applicants must submit a multipart application documenting eligibility; company financial background; and project design, costs, and economic feasibility; among other requirements.

o A challenging part of the application, according to three of 19 stakeholders who commented on the program, is demonstrating the economic soundness of the project that the loan guarantee is intended to fund because they believe the Federal Ship Financing Program to be overly risk averse. Specifically, four stakeholders said that it was difficult for vessel owners in emerging markets, like offshore wind farms, to get approved for a Federal Ship Financing Program loan guarantee because their speculative projects are considered high risk. One domestic vessel owner and operator said that the Federal Ship Financing Program is designed for companies with strong balance sheets that could easily be approved for a commercial loan, not for the companies that need the government support in order to get financing.

o According to representatives from one maritime industry association, the Federal Ship Financing Program became more risk averse due to defaults in the early 2000s that forced the Maritime Administration to cover the losses. According to Maritime Administration officials, they have a fiduciary responsibility to approve loan guarantees only for projects that can demonstrate financial viability, which makes it more difficult for high-risk projects to be approved. Maritime Administration officials also stated that some of these stakeholders’ concerns relate to issues beyond economic soundness. For example, according to Maritime Administration officials, speculative projects relate only partly to macroeconomic conditions and are also influenced by factors such as financial stability and geopolitical risk.

· Federal Ship Financing Program application review process takes too long. Of the 30 owner/operator survey respondents who had not applied for a loan guarantee from the Federal Ship Financing Program at the time of the survey, 10 respondents said that the long application review process contributed to their decision to not apply. Furthermore, 14 of the 19 stakeholders that commented on the Federal Ship Financing Program said that the application review process takes too long. Once an applicant submits an application to the Federal Ship Financing Program, the application review process takes, as a best-case scenario, between 6 to 9 months, according to Maritime Administration officials. These officials said they are aware that the application review process is long, and they encourage applicants to schedule preapplication meetings to ensure that applicants are eligible for the program before they submit their application and wait for the Maritime Administration’s review. Maritime Administration officials also said that every application is different, and certain applications can take longer due to factors including insufficient application documentation and applicant responsiveness. Furthermore, Maritime Administration officials said they have tried to address inefficiencies in the application review process. For example, they recently implemented a streamlined application review process for eligible applicants that meet certain requirements.[52] As of February 2025, no applicants had opted to use this process, according to Maritime Administration officials.

Maritime Administration Has Not Established Goals or Assessed Performance of Financial Assistance Programs for Vessel Owners or Operators

The Maritime Administration cannot determine to what extent the Capital Construction Fund Program, the Construction Reserve Fund Program, and the Federal Ship Financing Program are achieving intended outcomes because it has not established measurable goals or assessed the performance of these programs.[53] The Maritime Administration’s purpose for all three programs is to encourage vessel owners and operators to construct or reconstruct vessels at U.S. shipyards. However, the agency does not set any measurable goals for the programs to determine to what extent the programs’ purpose is being achieved. Without such goals, the agency also does not assess the results of these programs.

According to performance management leading practices, agencies should set measurable goals to identify the results they seek to achieve, collect performance information to measure progress, and use that information to assess the results and inform decisions to ensure further progress toward achieving those goals.[54]

Maritime Administration officials acknowledged that measuring the effect of these three programs would be helpful for managing them but also described challenges with doing so. For example, officials said it is difficult to develop metrics for the impact of programs to grow an industry because it is hard to know if a vessel owner or operator would have built a ship without the programs. While it may be challenging to determine how vital these programs are to a vessel owner or operator’s ability to construct a new vessel, the Maritime Administration should be able to establish measurable goals and determine whether the programs are helping vessel owners or operators achieve intended outcomes. The Maritime Administration receives annual reports from operators on Capital Construction Fund Program activity and is a co-signer on Construction Reserve Fund accounts and must approve all transactions. Officials said they do not use that information to assess the programs’ performance. However, after establishing measurable goals for the programs, officials could determine what information to track to assess performance—such as information in these reports or available through the Maritime Administration’s required approvals. For example, Maritime Administration officials could set a goal and track the number of new applicants to the Capital Construction Fund Program and the Construction Reserve Fund Program or the number or types of vessels constructed or reconstructed with associated funds. For the Federal Ship Financing Program, Maritime Administration officials receive information on projects from loan guarantee applications, such as planned vessels’ construction at U.S. shipyards. Officials could use application information to set a goal and track the number of new applications to the program, the number of vessels to be constructed or reconstructed due to program funding, or the number of U.S. shipyards receiving work due to program funding.

Maritime Administration officials said that they can only set goals for the programs based on what they can control, and the number of applications submitted or the number of vessels constructed with funds from these accounts is determined by the maritime industry. However, setting and tracking progress toward goals such as these could provide valuable information that could inform Maritime Administration activities, such as outreach to various industry segments. Doing so could also provide a better understanding of the extent to which the programs, as currently constituted, are meeting their objective of encouraging vessel construction at U.S. shipyards.

By having measurable goals and the ability to assess the programs’ performance in relation to the goals, the Maritime Administration would be better positioned to consider changes it could make to the programs to increase its ability to support U.S. vessel owners or operators. Setting measurable goals would also help officials identify the information they need to collect to assess the extent to which the programs are achieving intended goals. In addition, a better understanding of the effects of the Capital Construction Fund Program, the Construction Reserve Fund Program, and the Federal Ship Financing Program could help inform the Maritime Administration’s broader efforts to support the U.S. maritime industry in line with its National Maritime Strategy.

Two of the Maritime Administration’s Programs for Vessel Owners or Operators May Be Duplicative, and the Agency Has Not Formally Assessed Whether This Should Be Addressed

During our review, we found that the Maritime Administration’s two tax deferral programs, the Capital Construction Fund Program and the Construction Reserve Fund Program, appear duplicative in terms of beneficiaries, services, and administration.[55] According to Maritime Administration officials, it considers its four programs for vessel owners or operators or shipyards—the two tax deferral programs, the loan guarantee program, and the shipyard grant program, which we discuss below—to be different tools toward achieving the same purpose of encouraging vessel owners or operators to construct or reconstruct vessels at U.S. shipyards. While the loan guarantee program and the grant program provide distinctly different benefits in terms of the type of financial assistance provided and the eligible recipients, the extent to which the two tax deferral programs are distinct is less clear.

Beneficiaries. The beneficiaries eligible for the Capital Construction Fund Program and the Construction Reserve Fund Program are now largely similar due to a statutory amendment. Previously, as described above, the programs had different beneficiary groups. The Construction Reserve Fund Program is open to vessel owners or operators with otherwise eligible vessels engaged in the foreign or domestic commerce, and the Capital Construction Fund Program was, prior to December 2022, restricted to vessel owners or operators with otherwise eligible vessels engaged in foreign trade or certain specified types of domestic trade.[56] An amendment in the FY2023 NDAA removed the specified types of domestic trading restrictions.[57] As a result, according to Maritime Administration officials, vessel owners or operators whose vessels may have previously only been eligible for the Construction Reserve Fund Program are likely to also be eligible for the Capital Construction Fund Program. According to Maritime Administration officials, generally, fundholders want to close their Construction Reserve Fund Program account and apply to open a Capital Construction Fund Program account now that they are eligible, due to the potential benefits in services it provides.

Services. Both programs are tax deferral programs that provide similar benefits to fundholders by allowing them to defer paying tax on certain eligible transactions by depositing funds into an account for future vessel construction or reconstruction at a U.S. shipyard, among other specified purposes.[58] Both programs allow fundholders to defer paying tax on deposits from certain proceeds from the sale or loss of vessels.

The Capital Construction Fund Program may hold certain advantages in the services it provides over the Construction Reserve Fund Program. A Capital Construction Fund Program account offers greater flexibility for fundholders. According to Maritime Administration officials, a Construction Reserve Fund Program account must be a joint bank account between the fundholder and the Maritime Administration, and officials must approve every transaction. In contrast, once a vessel owner or operator is approved for a Capital Construction Fund Program account, Maritime Administration officials do not have to approve any transactions from that bank account, according to Maritime Administration officials. In addition, the Capital Construction Fund Program may offer more long-term benefits to fundholders than the Construction Reserve Fund Program. In general, funds deposited into a Capital Construction Fund Program account can remain in the account for up to 25 years before fundholders must use them for a qualified vessel, whereas fundholders must use the Construction Reserve Fund Program deposits within 3 years. Finally, while the Capital Construction Fund Program allows fundholders to defer paying taxes on earnings from vessel operations deposited into the account, tax must be paid on any earnings from vessel operations deposited into a Construction Reserve Fund Program account.

On the other hand, the Construction Reserve Fund Program may provide a benefit to fundholders that the Capital Construction Fund Program does not but, according to Maritime Administration officials, it is not used by many fundholders. The Construction Reserve Fund Program allows deposits from vessel operation earnings to come from vessels that are not documented under U.S. laws, whereas the Capital Construction Fund Program specifically requires all participating vessels to be documented under U.S. laws.[59] According to Maritime Administration officials, they were only aware of one fundholder out of the seven that participate in the Construction Reserve Fund Program having deposits with respect to vessels that are not documented under U.S. laws. In this case, Maritime Administration officials stated that the vessels were barges serving as docks and so were not actually moving along the inland waterway. In addition, Maritime Administration officials said that this fundholder was trying to find the required certificates to document the vessels under U.S. laws to participate in the Capital Construction Fund Program. Further, Maritime Administration officials said that with the eligibility changes and increased flexibility of the Capital Construction Fund Program, the Construction Reserve Fund Program has limited utility going forward.

Administration. The Office of Marine Financing within the Maritime Administration is responsible for administering both programs.[60] During our review, Maritime Administration officials said that two staff members handle the administrative responsibilities for both programs, using the same resources. Staff members review applications to the programs for eligibility and completeness, confirm all applications that meet the requirements, and work with vessel owners or operators to update applications that do not meet the requirements, according to officials. Officials do not consider the responsibility of administering the two programs to be an administrative burden. Even so, it is possible that combining the programs could help streamline the Maritime Administration’s administrative efforts.[61]

Duplicative programs can place additional demands on administrative resources and potentially confuse those seeking program services. We have previously reported that if agencies are implementing programs that have duplicative services, beneficiaries, and administration, they should consider options to address the duplication and increase economy and efficiency by consolidating or eliminating duplicative programs.[62] According to 17 out of 32 owner/operator survey respondents, a change the Maritime Administration could consider is combining the Capital Construction Fund Program and the Construction Reserve Fund Program.[63] According to one domestic vessel owner and operator, they used the programs interchangeably, and combining the programs could streamline the Maritime Administration’s efforts. While Maritime Administration officials acknowledge that there are many similarities between the two tax deferral programs, they have not formally evaluated the potential duplication and if greater efficiencies could be gained by combining the programs or sunsetting the Construction Reserve Fund Program.

Assessing the potential effects of either combining the programs or eliminating the Construction Reserve Fund via legislative changes from Congress would allow the Maritime Administration to determine if efficiencies could be gained from doing so and if further action was warranted.

Grant Program Helps Shipyards Modernize but Does Not Have Measurable Goals for Assessing Performance or Follow Some Federal Guidance

Small Shipyard Grant Program Has Provided Support to Shipyards, but Maritime Administration Has Not Established Goals or Assessed Performance

Maritime Administration officials and shipbuilding or repair companies that responded to our survey of shipbuilding or repair companies described ways that the Small Shipyard Grant program has helped shipyards. According to Maritime Administration officials, the program’s grants have helped shipyards increase their efficiency, the competitiveness of their operations, and the quality of ship construction and repair. Of the 60 shipbuilding or repair companies that responded to our survey that said they had received a Small Shipyard Grant in the past 5 years, 25 said they used the grant funding to purchase a crane; 14 purchased painting or blasting equipment; 12 purchased cutting equipment; and 24 purchased other types of equipment, such as forklifts. Further, 25 of the 60 shipbuilding or repair companies said they would not have been able to purchase their new equipment without the grant. These respondents also said that the equipment purchased improved efficiency and safety and lowered operating costs.

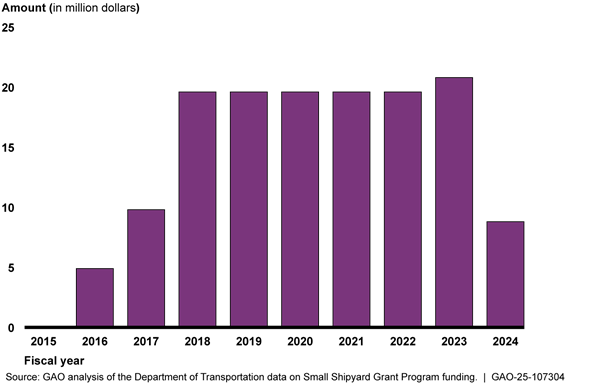

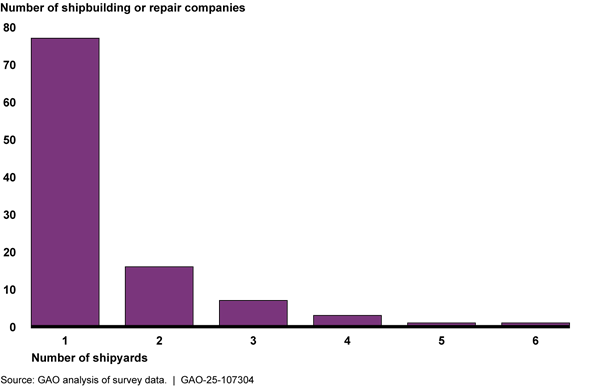

According to Maritime Administration officials, recent demand for Small Shipyard Grant program funding has been greater than the amount of available funding. For example, in fiscal year 2024, the Maritime Administration received 78 eligible applications from different shipbuilding or repair companies requesting just under $50 million and announced awards for $8.75 million in 15 grants. In fiscal year 2023, the Maritime Administration received 99 eligible applications requesting just under $82 million and announced awards for $20.8 million in 27 grants. Appropriations for the Small Shipyard Grant program, which started for fiscal year 2008, ranged from $0 to about $20 million annually for fiscal years 2015 through 2024, for a total of about $142 million (see fig. 1).[64] Maritime Administration officials said the average Small Shipyard Grant is about $800,000. For fiscal year 2025, the Small Shipyard Grant program was again appropriated $8.75 million, the same level as fiscal year 2024. According to Maritime Administration officials, the Notice of Funding Opportunity for the fiscal year 2025 Small Shipyard Grant program did not include any major changes.

While grantees have benefitted from the program, the Maritime Administration cannot determine to what extent the Small Shipyard Grant program is achieving its intended outcomes because it does not have measurable goals and does not assess the performance of the program. Specifically, the program purpose, as established in statute, is “to provide assistance in the form of grants, loans, and loan guarantees to small shipyards for capital improvements and maritime training programs to foster technical skills and operational productivity relating to shipbuilding, ship repair, and associated industries.” However, the Maritime Administration does not set any goals related to these purposes or track outcomes from the grants that can inform the extent to which the program is achieving its purpose. As discussed above, according to performance management leading practices, agencies should set measurable goals to identify the results they seek to achieve, collect performance information to measure progress, and use that information to assess the results and inform decisions to ensure further progress toward achieving those goals.[65]

Maritime Administration officials told us that measuring progress for the Small Shipyard Grant program would be helpful, but determining if a shipyard would have invested in new equipment or training without the program could be difficult to measure. Maritime Administration officials said that they have spoken with industry representatives on how to report on the effect of the program, but additional data would be needed, which Maritime Administration officials said they have not initiated collecting for two reasons. The first is that certain data can be business sensitive for small shipyards that have thin profit margins and are in competition with one another. Second, the statute authorizing the Small Shipyard Grant program does not require them to do so. However, Maritime Administration officials do collect some information from successful applicants that officials could use toward establishing and tracking measurable goals. As part of the post award process, shipyards that receive a grant are required to put together a final report that includes information on the project’s expected long-term performance outcomes, according to Maritime Administration officials.

With measurable goals, the Maritime Administration could assess the Small Shipyard Grant program’s performance. Such assessment would allow the Maritime Administration to consider whether the grant program is operating efficiently or effectively and any changes it could make to the program in the future to increase its ability to support small shipyards. In addition, as with its financial support programs for domestic vessel owners or operators, a better understanding of the impact of the Small Shipyard Grant program could help inform the Maritime Administration’s broader efforts to support the U.S. maritime industry and, in particular, U.S. commercial shipyards in line with its goals in the National Maritime Strategy.

Maritime Administration Does Not Document Its Decision Rationale for Awarding Small Shipyard Grants

Maritime Administration officials follow a multistep process for awarding grants to shipyards that apply to the Small Shipyard Grant program, but they do not document their decision rationale for why they award or do not award grants. To select recipients for a Small Shipyard Grant award, Maritime Administration officials said that they score applications in an internal spreadsheet on a range from 0 to 100. This scoring is based on the experience of the evaluators, who review applications based on the requirements in the Notice of Funding Opportunity and their professional judgment. According to Maritime Administration officials, these evaluators are subject matter experts, with decades of experience in their fields. After numerically scoring applications, Maritime Administration officials said they prepare a memo with the final list of selected applicants and their numeric scores for the Maritime Administrator. The Administrator receives an oral briefing on the rationale for award selection, along with this memo.

According to OMB regulations and DOT’s Guide to Financial Assistance, the Maritime Administration should develop a set of policies and procedures that permit consistency concerning its grant application merit review process and evaluation of each application.[66] Under DOT guidance, the documentation should contain the following:

· if approved for funding, an explanation of why the selected applications were chosen for funding over other applications; and

· if not approved for funding, and an explanation for not awarding the application.

However, Maritime Administration officials do not document their reasons for approving or not approving each application, and the scores do not serve as a clear guide to which projects are selected for funding. Specifically, while officials assign a numeric score to each application through their scoring sheet and make notes specific to each application received, our review found that they do not necessarily select only the highest-rated projects. Moreover, the scoring sheets do not include any additional explanation of why a selected applicant was chosen for funding over other applications or, if not approved for funding, why it was not. Our review of the 78 applications to this program in fiscal year 2024 found that the Maritime Administration scored 31 applications with a 90 or above but awarded funding to 14 of these applications and one application with a score of 77.5. The Maritime Administration did not document why it chose the 15 applications it selected for funding, including why an application with a score of 77.5 received an award over 38 unsuccessful applications with higher scores.

Maritime Administration officials said they do not document their decision rationale. Further, they said that the numerical scores given to applications are not the sole determining factor in award decisions. Maritime Administration officials said they consider several factors, including statutory and policy priorities, project feasibility and readiness, funding availability and distribution, and evaluator discretion. Moreover, Maritime Administration officials said that they prioritize geographic distribution and new applicants, meaning that shipyards with active or recent grants are less likely to receive additional grants. However, these other factors for selecting awardees are not documented.

We have previously reported that DOT’s administration of discretionary grants should be more consistent and transparent. As a result, we have a priority recommendation that DOT develop a department-wide approach for evaluating applications and documenting key decisions for these programs.[67] As of April 2025, DOT had not implemented this recommendation. By documenting the specific reasons why the Maritime Administration did or did not select an application for an award as compared with other applications, the agency can better demonstrate that it is funding the projects that best meet the Small Shipyard Grant program’s statutory purpose to support small shipyards. Further, the agency can demonstrate that it is reviewing grant applications in a fair and equitable manner.

Maritime Administration Does Not Notify Unsuccessful Shipyard Grant Applicants About Their Award Status or Options for Requesting Feedback

The Maritime Administration does not provide certain information to unsuccessful applicants to the Small Shipyard Grant program, as required by DOT guidance. Specifically, DOT’s Guide to Financial Assistance requires the grant administrator to notify unsuccessful applicants that their application was not successful.[68] For each unsuccessful applicant, the grant administrator must provide the applicant either (1) a brief, written explanation of the decision rationale; or (2) an opportunity to receive post-selection oral feedback regarding the decision, and a review of their application.

However, we found that the Maritime Administration does not inform unsuccessful Small Shipyard Grant program applicants (1) that they did not receive an award, (2) why they did not receive an award, or (3) that they can request feedback. Maritime Administration officials said they contact successful applicants via email to notify them of their award but do not contact unsuccessful applicants. Further, officials said they offer feedback to those unsuccessful applicants that request it but do not communicate this to unsuccessful applicants, unless the applicant contacts the Maritime Administration first. When an unsuccessful applicant requests feedback, Maritime Administration officials said that they show the applicant where the evaluator thought the application could use improvement and how it compared with other applications.

Unsuccessful applicants may not know that they need to request feedback from the Maritime Administration to receive it. According to our survey of shipbuilding or repair companies, of the 39 respondents who applied but did not receive an award, 30 said they did not receive feedback from the Maritime Administration on why their application was unsuccessful. A representative at one shipyard we interviewed told us that they did not receive clarification at the time about why their application was not awarded a grant and that they were not aware of any process for receiving feedback. Further, 94 of 105 shipbuilding or repair companies that responded to our shipyard survey said that the Maritime Administration should improve feedback to the Small Shipyard Grant program applicants, and 45 survey respondents (just under half) said that improving feedback was very important.

Maritime Administration officials said they do not provide this information to unsuccessful applicants because, typically, the applicant calls the Maritime Administration when they have not heard about receiving an award. Officials then verbally notify the caller that they did not receive a Small Shipyard Grant award and give the caller the option to receive feedback on their unsuccessful application.

Notifying all unsuccessful applicants that they did not receive a Small Shipyard Grant award and providing information regarding why they did not receive funding would enhance the Maritime Administration’s technical support to small shipyards. Moreover, systematically providing a feedback option to unsuccessful applicants would help those applicants target future funding requests to this competitive grant program.

U.S. Stakeholders Identified Ideas to Address Challenges in the Maritime Industry, and Foreign Officials Described Related Challenges and Experiences

U.S. Stakeholders Identified Challenges Vessel Owners or Operators and Shipyards Face; Foreign Officials and Shipyard Representatives Described Some Similar Challenges

Domestic vessel owners or operators and U.S. shipyards that build commercial ships face challenges competing within the domestic market subject to the Jones Act and related coastwise laws, according to stakeholders we spoke to and information provided by respondents to our two surveys. Shipyards in selected other countries face some similar challenges, according to representatives from shipbuilding companies in Singapore and South Korea and foreign government officials we spoke with from Singapore, South Korea, Canada, and the U.K.

Domestic Vessel Owners or Operators

Competition with Foreign Flag Vessels

Generally, Jones-Act-compliant vessels, with their requirements to be built in the United States and crewed with U.S.-citizen mariners, are more expensive to construct and operate, according to the Congressional Research Service.[69] According to the Maritime Administration, vessel owners or operators in the domestic market face an even playing field because they compete under uniform laws and regulations that protect their crews and cargo.[70] However, according to six stakeholders we interviewed, a key challenge for emerging markets, such as offshore wind farms, related to increasing domestic vessel owners’ or operators’ business, is uncertainty or inconsistency around prioritizing domestic vessels in certain domestic maritime markets.[71] This inconsistency can lead to domestic vessel owners or operators being disadvantaged due to competition from lower-cost foreign vessels in certain domestic markets such as offshore wind farms, according to representatives from three industry associations.

Specifically, one industry association representative stated that U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which is responsible for interpreting which activities fall under the Jones Act and other coastwise laws, has at times made determinations that allow foreign-flag vessels to perform certain functions that, in the association’s view, should be protected for domestic vessels. For example, this representative cited a ruling by CBP related to offshore wind development, based on the concept that activity at pristine seabed locations on the outer continental shelf do not constitute a coastwise point for Jones Act purposes.[72] This representative stated that as a result, many foreign-flag vessels are involved in constructing U.S. offshore wind farms, limiting the extent to which this emerging industry can lead to vessel owners or operators investing in new vessels in U.S. shipyards, which could help support the maritime industry.

Competition with Other Modes of Transportation

According to representatives from two industry associations, another challenge for domestic vessel owners or operators is competition with other modes of transportation, such as long-haul trucking. Specifically, one industry association said that owners or operators are competing against other modes of transportation that are more recognizable and receive greater funding, such as highways, air cargo, and railroads. According to one domestic vessel owner and operator, another challenge is that transporting cargo via U.S. waterways is slower than by truck in the current maritime transportation network.

Shipyards

Workforce

Fluctuating demand for new vessel construction and vessel repair in the United States contributes to workforce challenges, according to four shipyard representatives, two industry association representatives, and one domestic owner and operator we interviewed. According to a 2002 Center for Naval Analysis study, the U.S. shipbuilding industry has experienced several major “boom-and-bust” cycles since the 1950s. The cycles were due to shifting government shipbuilding incentives, collapse of the offshore oil and gas industry, and overbuilding vessels for different segments of the U.S. domestic fleet.[73] Furthermore, a Maritime Administration study from 2021 stated that U.S. private shipbuilding companies continued to experience “boom-and-bust” cycles from 2005 through 2020.[74] According to representatives from four shipyards, one vessel owner and operator, and two industry associations, this “boom-and-bust” cycle contributes to two distinct challenges related to retention of the current workforce and recruitment of new workers.[75]

With respect to retention of workers, 62 of the 105 shipbuilding or repair companies that responded to our survey said that retaining workers was very or moderately challenging. For example, one shipyard representative we spoke with said when they lay off workers during a “bust,” they cannot find workers when demand increases again. Another shipyard representative said that a steadier workflow would be useful for workforce retention.

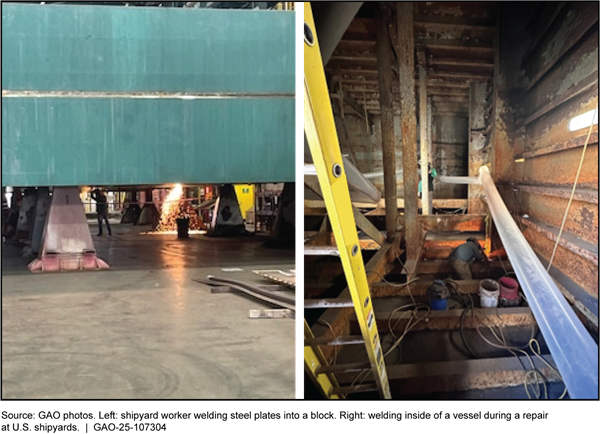

Figure 2: Images of a Shipyard Worker Welding Steel Plates into a Block (left) and Welding Inside a Vessel During a Repair at a U.S. Shipyard (right).

With respect to recruitment, U.S. shipyards find it challenging to recruit experienced workers due to competition with other sectors, among other reasons, according to 12 stakeholders, including shipyard representatives, vessel owners or operators, and industry association representatives. Moreover, 90 of the 105 surveyed shipbuilding or repair companies said that recruiting workers was very or moderately challenging. For example, representatives of one shipbuilding and repair industry group said that the labor market is tight post-pandemic, and shipyards are now competing with service industry employers for workers. One shipyard representative said that at one point, the shipyard had 1,000 employees, but now that number is down to 200, in part because younger generations are not getting into the shipbuilding and repair industry.

Foreign officials we spoke with in the U.K. also described workforce challenges related to “boom-and-bust” cycles and difficulties recruiting workers, whereas officials in South Korea and Singapore described diversified demand from the global commercial markets for their shipbuilding and repair services that largely protected them from facing such workforce challenges.[76] According to government officials in the U.K., a sustainable demand of different types of shipbuilding contracts is required to recruit and retain workers. Shipyard representatives and government officials in South Korea and Singapore said that while “boom-and-bust” cycles have occurred due to the global financial crisis or swings in the global oil and gas market, the variety of vessels they build and repair, and their presence in the global market, has enabled shipyards to keep their workflow steady and to provide steady work to their workers.

Even so, shipyard representatives and government officials in both countries stated that they struggled to recruit sufficient workers for some of the same reasons cited by U.S. shipyards, such as competition from other industries and less interest from younger generations. They stated that they use foreign workers to help address their workforce shortages to the extent that their laws allow, but that this may create challenges with language barriers and training deficiencies. Further, both Singapore and South Korea have limits on the percentage of shipyard workers who can come from foreign countries, according to government officials in both countries. These shipyard representatives said they developed training programs to help the foreign workers integrate.

Infrastructure

Aging shipbuilding and repair infrastructure can create challenges for production efficiency and shipyard modernization, according to six shipyard representatives we interviewed. Most surveyed shipbuilding or repair companies, specifically 92 out of 105, said outdated infrastructure impeded operational efficiency.[77] According to Maritime Administration officials, most U.S. shipyard infrastructure is from when the U.S. government invested in shipyards during World War II.[78] One shipyard representative said that they are still using a dry dock built during World War II, even though it had reached the end of its useful life. Shipyard representatives in Texas said that it would cost up to $30 million to purchase a new dry dock. Maritime Administration officials also said that private investment and venture capital has not invested in shipyards for much needed improvement and modernization, at least in part due to the “boom-and-bust” issue that makes it challenging to guarantee a return on investment. Most surveyed shipbuilding or repair companies, specifically 89 out of 105, also said that financing infrastructure improvements has been challenging.[79] For example, one shipyard stated that the single most important need is repairing aging infrastructure because most facilities operate with infrastructure built half a century ago and lack capital to replace it. Without that capital, they run the risk of closing and, once a shipyard closes, it will not reopen.

In contrast, shipyard representatives in South Korea and Singapore stated that their success in the highly competitive global shipbuilding market was dependent on having highly efficient shipyard infrastructure and production processes. For example, representatives at one shipyard stated that they had designed the layout of the shipyard, including buildings and other infrastructure, to ensure smooth logistics from assembly to dock and that they redesigned or replaced infrastructure as needed.

Supply Chains

Sourcing specific materials or parts can be challenging due to the lack of a sufficient and diverse domestic supply base, according to six shipyards and one industry association. Some of these stakeholders said that the U.S. supply base was not sufficient because the commercial shipbuilding industry was too small to support a robust supply market. Specifically, seven industry groups and shipyard representatives and DOD officials we spoke with said that sourcing materials, such as steel, and components such as microchips, batteries, wiring, and cabling, can be challenging. One shipyard representative said that proposed tariffs for steel and aluminum may increase this challenge in the future. Representatives from one U.S. shipyard with a foreign parent company said that another challenge with U.S. suppliers is that they can be far from shipyards, which adds to cost.

Similar to the United States, materials and parts sourcing can be challenging in the U.K. due to varying demand, according to U.K. officials.[80] In comparison, South Korea and Singapore shipyard representatives stated that the countries’ shipyards have robust local supply chains because they support a much larger shipbuilding industry than in the United States. In addition, representatives at shipbuilding companies in both South Korea and Singapore stated that their shipyards’ location in clusters of shipyards allows for synergies. Such synergies include drawing suppliers to the same area to provide supplies for multiple shipyards with minimal travel logistics involved, reducing potential for delays and costs. Representatives at shipbuilding companies in South Korea also told us that the clustering of shipyards facilitates the ability to order subcomponents for their ships from other shipyards in the same region.

U.S. Stakeholders Offered Ideas to Address Challenges Faced by Vessel Owners or Operators and Shipyards; Foreign Officials and Representatives Described Related Experiences

Stakeholders identified several ideas to potentially address challenges in the U.S. maritime industry and grow the U.S.-built fleet.[81] These ideas related to domestic vessel owners or operators and shipyards specifically, as well as to how to improve the National Maritime Strategy to better support the U.S. maritime industry. Foreign officials and shipyard representatives described experiences that related to some of these ideas.

Domestic Vessel Owners or Operators

Prioritize U.S.-Flag Vessels

U.S. domestic vessels could be better prioritized over foreign vessels in markets like offshore wind farms to encourage growth, according to six stakeholders we interviewed. According to one industry group representative, for example, domestic tug vessels could play a larger role in the offshore industry, but instead foreign-flag tug vessels are moving some equipment into U.S. waters. In addition, one domestic vessel owner and operator said that counteracting CBP rulings regarding the application of the Jones Act that have allowed for foreign-flag vessels to operate in U.S. waters in certain types of instances could return cargo to domestic vessels in areas besides offshore wind farms. Specifically, this owner and operator referred to a CBP ruling on liquid natural gas that would allow U.S. natural gas to be sent to Mexico via pipeline for a liquefaction process and then transported in a liquefied state back to the United States on foreign-flag vessels. CBP ruled that the proposed liquefaction process would result in the creation of a new and different product within the meaning of the CBP regulatory exception to the application of the Jones Act and, therefore, would not be required to be transported on U.S. domestic vessels.[82]

Encourage New Maritime Markets