CYBERSECURITY

DHS Implemented a Grant Program to Enable State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Governments to Improve Security

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107313. For more information, contact David B. Hinchman at hinchmand@gao.gov, or Tina Won Sherman at shermant@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107313, a report to congressional committees

cybersecUrity

DHS Implemented a Grant Program to Enable State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Governments to Improve Security

Why GAO Did This Study

State, local, tribal, and territorial governments provide essential services, including public utilities, healthcare, and public safety. To help address cybersecurity risks and threats to these essential services, DHS implemented a cybersecurity program under the State and Local Cybersecurity Improvement Act.

The act includes a provision in statute for GAO to review DHS’s grant program. This report (1) identifies, categorizes, and describes the projects funded by the grant program, (2) examines the extent to which DHS's grant program review process met the requirements of the act, (3) examines the extent to which selected applicants met eligibility requirements, and (4) describes selected state and territory officials’ views on the program.

GAO identified and summarized approved cybersecurity projects under the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program. GAO analyzed requirements for FEMA and CISA in administering the grant program. GAO also selected a nongeneralizable random sample of seven state and territory grant applicants from various regions of the country to examine the extent to which applicants met eligibility requirements. GAO interviewed selected officials from seven states and two territories who agreed to provide their views on the program.

What GAO Found

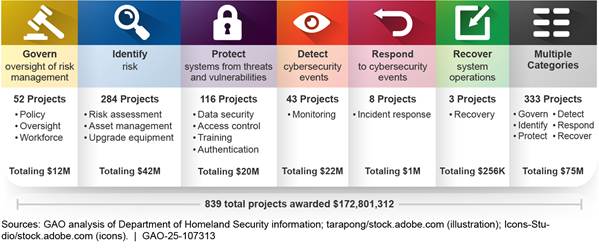

Pursuant to federal law, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) implemented a grant program to help state, local, tribal, and territorial governments address cybersecurity risks and threats. As of August 1, 2024, DHS provided about $172 million in grants to 33 states and territories. The grants are funding 839 state and local cybersecurity projects that align with core cybersecurity functions as defined by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (see figure). The projects include developing cybersecurity policy, hiring cybersecurity contractors, upgrading equipment, and implementing multi-factor authentication. Such projects are essential to identifying risks, protecting systems, detecting events, and responding to and recovering from incidents.

In administering the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program, DHS’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) are responsible for reviewing (1) cybersecurity grant applications and (2) applicants’ proposed cybersecurity projects. GAO found that the review and selection processes used by these agencies met the law’s specific requirements. For example, CISA used a checklist to validate that applicants’ cybersecurity plans contained 16 elements required by the act.

GAO also found that seven selected applicants met the grant program’s eligibility requirements, with allowed exceptions. For example, applicants were allowed to submit investment justifications without detailing project-level information if they were not yet ready when the applications were due. In these cases, DHS held awarded funds until applicants addressed requirements.

Selected state and territory officials had positive feedback about the grant program, such as FEMA’s willingness to make improvements to the application process. Officials also noted challenges, including sustaining cybersecurity projects after the grant program ends. For example, officials from three states emphasized the importance of reauthorizing the program. However, officials from other states said that they plan to use other federal grant programs or state and local-level funds to continue funding cybersecurity projects.

Abbreviations

|

CISA |

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FEMA |

Federal Emergency Management Agency |

|

FY |

fiscal year |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

NOFO |

Notice of Funding Opportunity |

|

SAA |

State Administrative Agency |

|

SLTT |

state, local, tribal, and territorial |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 29, 2025

The Honorable Rand Paul, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Mark E. Green, M.D.

Chairman

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

State, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) governments provide essential services, including public utilities, healthcare, and public safety. These services are increasingly reliant on the internet, making them vulnerable to various cyber-related risks. In recent years, cyberattacks on locally owned utilities and school districts have become more frequent and severe, demonstrating the need for increased cybersecurity.

Ensuring the cybersecurity of the nation has been on our High-Risk List since 1997. This was expanded to include protecting the cybersecurity of critical infrastructure in 2003. The nation’s critical infrastructure includes many of the services owned and operated by SLTT governments, such as water and wastewater facilities. In our June 2024 update, we reported on major cybersecurity challenges facing the nation, including establishing a more comprehensive cybersecurity strategy and performing effective oversight.[1]

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, enacted in November 2021, included the State and Local Cybersecurity Improvement Act. This act established a program to help eligible SLTT entities address cybersecurity risks and threats to information systems.[2] Specifically, the act authorized $1 billion to be appropriated over 4 years to be distributed by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to these eligible entities.

DHS is responsible for implementing two grant programs: the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program and the Tribal Cybersecurity Grant Program. DHS announced the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program in September 2022 and the Tribal Cybersecurity Grant Program in September 2023.

DHS’s Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) are jointly responsible for managing the grant programs. FEMA is responsible for the fiscal administration of the grants while CISA is responsible for setting programmatic goals and objectives and providing expertise on cybersecurity.

The act includes a provision for GAO to conduct a review of DHS’s grant selection process. Our specific objectives were to (1) identify, categorize, and describe the projects funded by the grant program; (2) determine the extent to which DHS’s grant selection process for the program met the requirements of the act; (3) determine the extent to which grant applicants met the eligibility requirements for the program; and (4) describe selected states’ and territories’ views on the program.

For the purpose of our review, we focused on the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program because grant applications and project-level data were not yet available for the Tribal Cybersecurity Grant Program. While Tribal Nations are not eligible to apply directly for grants under the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program, they can receive funding as a local government under the program. As a result, some Tribal Nations’ projects are included in this review.

To address the first objective, we identified eligible entities that could apply for the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program. There are 56 eligible entities, referred to as State Administrative Agencies (SAAs), that could apply for the grant program on behalf of the 50 states, the U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia.[3] We analyzed data from FEMA to determine the number of cybersecurity projects approved. We compiled a list of 839 cybersecurity projects approved as of August 1, 2024, and categorized these projects based on the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework core functions (i.e., govern, identify, detect, protect, respond, and recover) because the framework provides a taxonomy for communicating cybersecurity efforts.[4] To categorize the projects, we reviewed the descriptions of the 839 approved cybersecurity projects and aligned each project to one or more NIST core function. Further details of the NIST core functions are provided in appendix I.

To address the second objective, we analyzed the act to identify FEMA and CISA requirements for administering the grant program. We identified five such requirements that FEMA or CISA should be using. The five requirements include validating that deliverables—such as the applicants’ cybersecurity planning committee and cybersecurity plan—met requirements established in the act.[5] Next, we identified FEMA and CISA’s processes used to validate if applicants met each requirement. For example, we identified that CISA developed an internal checklist with 16 required elements to analyze applicants’ cybersecurity plans. We compared these requirements to the processes used to review applications.

In addition, we selected a nongeneralizable sample of grant applicants to determine the extent to which FEMA and CISA used their grant review process. To do so, we collected available data from FEMA about entities that had obligated awarded amounts. This yielded 54 eligible entities that applied for funding in fiscal year (FY) 2022 and 55 entities that applied in FY 2023. Next, to mitigate selection biases, we developed a method to randomly select eligible entities. First, we randomly selected the state of Connecticut to be our test case to determine the resources we needed to perform a comprehensive analysis. Based on that review, we narrowed the number of entities to those that had approved cybersecurity projects for FY 2022 and FY 2023. This analysis yielded an initial list of 30 states and territories. To ensure a diversity of geographic regions, we categorized the 30 entities across FEMA’s 10 regions, then combined the regions to create five groups. We then combined all territories into a separate (sixth) group to ensure that our nongeneralizable sample included a territory. Finally, we randomly selected one applicant from each of the six groups to mitigate any potential selection bias. In addition to Connecticut, we selected a stratified random nongeneralizable sample of grant application packages from the following SAAs: Alaska, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Ohio, West Virginia, and Puerto Rico. This yielded a total of seven applicants. We note that nongeneralizable samples cannot be used to make inferences about a population.

Further, to confirm whether FEMA and CISA used their process to review and approve grant applications from our seven selected grant applicants, we evaluated 14 grant application packages, one for each of the first 2 years of the program (FY 2022 and FY 2023), to determine whether the agencies’ reviews met the requirements outlined in the act. We also interviewed FEMA and CISA officials to determine and validate our understanding of their roles and responsibilities and the processes used to review and approve grant applications in accordance with the act’s requirements.

To address the third objective, we analyzed the 14 grant applications submitted by the seven selected applicants. We compared these applications against the eligibility criteria provided in the grant program’s publicly issued Notices of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for FY 2022 and FY 2023 and DHS’s internal checklist for determining an applicant’s eligibility.[6] For example, the NOFO required applicants to develop a cybersecurity plan and investment justifications outlining cybersecurity projects. We also interviewed FEMA and CISA officials on their grant program criteria, procedures for assisting applicants in meeting eligibility requirements, and their efforts to advise applicants on incomplete or missing elements.

To address our fourth objective, we used our initial nongeneralizable sample of states and territories outlined in objective 2. In addition, we randomly selected additional states and territories if officials from our initial selection of seven declined to speak with us. Next, we obtained contacts for 13 SAAs that were publicly available and then emailed them to request an interview to obtain their views on the grant program. Nine SAAs responded that they were willing to speak with us. These SAAs included five from our initial selection of seven states and territory outlined in objective 2 and four additional SAAs that also submitted cybersecurity projects for approval by CISA. Specifically, we interviewed officials from the following nine SAAs: Alaska, Kentucky, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and the territories of Northern Mariana Islands and Puerto Rico. We asked SAA officials about their views of the grant program and challenges, if any, that they faced in using the awarded grants or in sustaining funding for approved cybersecurity projects. We note that results from nongeneralizable samples cannot be used to make inferences about a population.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Overview of the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program

In September 2022, DHS announced the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program for state, local, and territorial governments as established by the act. The $1 billion program is authorized to be appropriated across four years to support cybersecurity projects, including $200 million in FY 2022, $400 million in FY 2023, $300 million in FY 2024, and $100 million in FY 2025. Each award year has a 4-year period of performance.

Under the grant program, eligible entities, referred to as SAAs, can apply for the grants. These entities represent the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and the U.S. territories of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico are to receive a minimum of 1 percent of the total funds appropriated for the fiscal year, and the remaining four territories are to each receive 0.25 percent.

SAAs are responsible for applying for and managing grant applications and awards. In addition, the SAAs are responsible for ensuring that at least 80 percent of awarded funds are passed through to local governments, and at least 25 percent of the 80 percent of the total awards are passed through to rural communities.[7] Although Tribes are not eligible to apply directly for the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program’s funding, they may be eligible to receive funding as a local government.[8]

As previously noted, DHS’s FEMA and CISA are jointly responsible for managing the grant program. FEMA is responsible for providing grant administration, including awarding and allocation of funds to eligible entities, financial management, and oversight of executing funds. CISA is responsible for providing subject matter expertise in cybersecurity, setting programmatic goals and objectives, and reviewing and approving submitted SAA cybersecurity plans and projects. In addition, in December 2024, CISA and the Office of the National Cyber Director published a guide to assist all federal grant-making agencies in incorporating cybersecurity into all of their existing grant programs, and to enable grant recipients to build cyber resilience into their grant-funded infrastructure projects.[9]

We previously reported on federal grant programs in which a portion of funds can be used to provide cybersecurity support to SLTT governments.[10] For example, FEMA administered five grant programs[11] and awarded about $670 million for FY 2019 through FY 2022 to be used for cybersecurity-related activities, but none of the grants were specifically for cybersecurity.

Federal Requirements for the Grant Program

The State and Local Cybersecurity Improvement Act established requirements for both the awarding agency and the grant applicants. DHS issues annual guidance in the form of a NOFO to assist eligible applicants in meeting the act’s requirements. In addition, CISA established requirements within the NOFO guidance for individual cybersecurity projects to help states, territories, and local entities increase their cybersecurity maturity.

Requirements for the awarding agency. The act outlines specific requirements that DHS must meet for awarding grant program funding to eligible applicants. Specifically, the act requires DHS to confirm that eligible entities have:

· established a cybersecurity planning committee,

· developed a cybersecurity plan with 16 required elements,

· met pass through requirements,[12]

· met requirements of a multi-entity group, as applicable, and

· provided annual progress reports from eligible entities.

The act allows for DHS to provide flexibilities for applicants to meet requirements within the 4-year period of performance. That is, it does not require applicants to adopt best practices and implement cybersecurity projects at the onset.

In addition, DHS’s CISA is required to (1) submit annual reports to Congress about use of the grants awarded and (2) submit a study and recommendations on the use of a risk-based formula for apportioning grant program funds.

Requirements for grant applicants. DHS publishes guidance to grant applicants in the form of NOFOs that prescribe specific requirements for individual grant programs. The grant program’s NOFO identifies a number of eligibility requirements that applicants must meet to include required deliverables as part of the grant program package. In addition, FEMA and CISA developed program objectives that applicants are expected to address over the 4-year period of performance of the grant. These objectives are to establish governance structures, assess systems and capabilities, implement security protections, and build a cybersecurity workforce.

In addition to addressing these grant program objectives, applicants must meet other NOFO requirements, unless the act or DHS allow an exception to these requirements (see table 1).

Table 1: Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) Eligibility Requirements for the State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program and Allowed Exceptions

|

NOFO requirement |

Exceptions to requirement allowed by |

|

Establish a cybersecurity planning committee and charter |

May use existing planning committees as long as the composition of the committee meets requirements outlined in the act. |

|

Develop a cybersecurity plan |

Allowed not to submit a cybersecurity plan if applicants certify to DHS that the activities that will be supported by the grant are integral to the development of the cybersecurity plan or assist with activities that address imminent cybersecurity threats. |

|

Submit investment justification |

Can submit investment justifications marked “to be determined” if applicants are not ready to submit cybersecurity projects for Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA) approval on the application due date. |

|

Submit project worksheet |

Can submit project worksheets marked “to be determined” if applicants are not ready to submit cybersecurity projects for CISA’s approval on the application due date. |

|

Sign up for CISA services |

Are not required to sign up for CISA services for initial submission and approval of a grant. Applicants are required to sign up for these services once during the 4-year period of performance. |

|

Conduct CISA nationwide cybersecurity reviewa |

No exceptions. |

|

Request pre-award costs |

No exceptions. |

|

Pass through funds |

Allowed to submit partially completed applications if applicants are not prepared to submit projects at the time applications were due. For those applicants, DHS accepts the application package without the 45-day signed consent letter indicating that the entity passed through required funds. |

|

Meet cost share |

Allowed a cost share waiver if applicants demonstrate economic hardship. In addition, cost share requirements are waived for insular areas of the U.S. territories of American Samoa, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. |

|

Submit environmental planning and historic preservation documentation |

No exceptions. |

|

Submit financial, performance progress, and single audit reports |

No exceptions. |

|

Submit closeout reporting |

No exceptions. |

Source: GAO analysis of grant program documentation. | GAO‑25‑107313

aThe Nationwide Cybersecurity Review is a free, anonymous, annual self-assessment designed to measure gaps and capabilities of state, local, tribal, and territorial governments’ cybersecurity programs. It is based on the National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework and is sponsored by DHS and the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center. The Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center is an independent, nonprofit organization that was designated by DHS in 2010 as the cybersecurity information sharing and analysis center for state, local, tribal, and territorial governments.

Additional FY 2023 NOFO requirements for cybersecurity projects. In addition to the requirements described above, CISA required in FY 2023 that individual projects include addressing cybersecurity best practices to help states, territories, and local entities increase their cybersecurity maturity. Applicants have until the end of the grant program’s 4-year period of performance to address and begin implementation of the following:

· multi-factor authentication;

· enhanced logging;[13]

· encrypt data at rest and in transit;[14]

· end use of unsupported/end-of-life software and hardware that are accessible from the internet;

· prohibit use of known/fixed/default passwords and credentials;

· ensure the ability to reconstitute systems (backups);

· actively engaging in information sharing between CISA and state, local, and territorial entities in cyber relevant time frames to drive down cyber risk; and

· consider migration to the .gov internet domain.[15]

SLTT Governments Planned to Use Approximately $172 Million for a Variety of Cybersecurity Projects

DHS expended $172 million to 33 states and territories for 839 approved cybersecurity projects, as of August 1, 2024. SLTT governments planned to use cybersecurity projects in various ways, such as developing cybersecurity policy, engaging cybersecurity contractors, upgrading equipment, implementing multi-factor authentication, and others.

The cybersecurity projects are aligned with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework core functions and categorized into multiple subcategories, as shown in figure 1. In addition, 10 of the 839 projects were for five Tribes to receive about $500,000 for cybersecurity projects, including for cybersecurity risk assessments, cybersecurity training, and cyberattack tabletop exercises. Further details of how the projects align with each NIST core function are provided below the figure.

Figure 1: State and Territory Cybersecurity Projects’ Alignment with the Core Functions of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Cybersecurity Framework

Govern. Cybersecurity projects aligning with this core function include the subcategories of cybersecurity policy, oversight, and upgrading workforce. For example:

· Cybersecurity policy: 15 projects were approved to develop states and territories’ cybersecurity policy, totaling about $3.5 million. For example, 10 states and one territory plan to use funds to develop a statewide cybersecurity plan. Specifically, some entities plan to assess, create, and implement policies and procedures that will help protect their data, provide continuity of service, and protect their information systems from cyberattacks1418603.

· Oversight: three projects were approved for one state and one territory on cybersecurity oversight, totaling about $282,000. For example, one entity plans to identify cybersecurity skillsets, procedures, and practices within organizations to build a stronger cybersecurity governance procedure. Another entity plans to develop and implement cybersecurity plan templates and document governance structures within state, local, and territorial government agencies.

· Workforce: 34 projects were approved to engage cybersecurity contractors at states and territories, totaling about $8 million. For example, 12 states plan to engage contractors for planning and implementing cybersecurity programs.

Identify. Cybersecurity projects aligning with this core function include the subcategories of risk assessment, asset management, and upgrading equipment. For example:

· Risk assessment: 94 projects were approved for 20 states and one territory to conduct cybersecurity risk assessments, totaling about $20 million. Specifically, multiple states and one territory plan to perform recurring cybersecurity vulnerability scans of municipalities’ internal and external networks, systems, and applications, and provide recommended mitigations for the highest criticality vulnerabilities. In addition, one Tribe plans to perform risk assessments to identify risks and vulnerabilities to its Tribal Nation agencies. Other entities plan to build a cybersecurity roadmap to improve their cybersecurity posture.

· Asset management: three projects were approved for two states to conduct asset management assessments, totaling about $600,000. Specifically, one entity plans to cover a sampling of localities that use computerized devices for water to help mitigate and protect against attacks. Another entity plans to help safeguard data and the privacy of 178 school districts and 190,000 students to address cybersecurity threats, attacks, and threat resolution activities.

· Upgrading equipment: 187 projects were approved for 13 states and one territory to conduct upgrades to equipment, totaling about $22 million. For example, one entity plans to replace aging firewall systems while another plans to implement endpoint protection software management tools.

Protect. Cybersecurity projects aligning with this core function include the subcategories of data security, access control, training, and authentication. For example:

· Data security: three projects were approved for three states to improve data security, totaling about $1 million. Specifically, one state plans to decrease risks posed by malware, viruses, and other malicious internet activity. Another state plans to implement and update security protections and visibility of the networks that its departments and agencies depend on for accessing systems and communications.

· Access control: one project, totaling about $8,000, was approved for an entity to implement a third-party identity and access management software tool for all city employees and departments.

· Training: 69 projects were approved for 19 states and two territories to conduct cybersecurity training, totaling about $15 million. Specifically, some entities plan to train personnel to understand their roles and responsibilities within established cybersecurity policies, procedures, and practices. One entity plans to provide security awareness training courses for all municipality employees. Other entities plan to provide cybersecurity training to employees to protect against threats to critical infrastructure and key resources. One Tribe plans to have officials attend a boot camp to learn best practices and enhance awareness of cybersecurity-related topics.

· Authentication: 43 projects were approved for nine states to conduct authentication, totaling about $4 million. For example, one entity plans to purchase multi-factor authentication hardware tokens to enhance security.

Detect. Forty-three projects were approved for 12 states and one territory to conduct monitoring, totaling about $22 million. Specifically, some entities plan to implement intrusion detection systems on governmental networks, which could be monitored around-the-clock to identify intrusion attacks, alert key personnel, and report nationally to inform about coordinated cyberattacks. Other entities plan to purchase endpoint protection products with the enhancements of machine learning, which may include cloud computing, email, and other solutions.

Respond. Eight projects were approved for six entities to conduct incident response, totaling about $1 million. For example, one entity plans to develop and facilitate cyber exercises to help improve the ability to monitor, evaluate, and assess cyber incident responses. Another entity plans to develop cybersecurity incident response plans.

Recover. Three projects were approved for three entities regarding incident recovery, totaling about $250,000. Specifically, one state plans to re-envision its disaster recovery strategies while another state plans to seek a disaster recovery site and point-to-point fiber connection for 9-1-1 services.

Multiple categories. Three hundred thirty-three projects were categorized as having a combination of two or more identified categories in the above listings, totaling about $75 million. Specifically, some states had single projects to evaluate the maturity of their cybersecurity program, develop and implement their cybersecurity plan, and upgrade their network software and hardware.

DHS’s Grant Review Process Met the Act’s Requirements

The act requires that DHS review grant applications to determine whether applicants satisfied requirements outlined in the act before granting awards. This review includes determining whether applicants included required deliverables, like cybersecurity plans, as part of the application package.

DHS’s grant selection process met the requirements of the act. Table 2 describes statutory requirements that DHS must meet for the grant program and whether DHS met those requirements when reviewing and approving applications.

Table 2: Extent to Which the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Statutory Grant Review Met Requirements

|

Requirement |

Description |

Did DHS meet the requirement? |

|

Establishment of a cybersecurity planning committee |

DHS is required to evaluate and confirm that eligible entities should establish a cybersecurity planning committee to assist in developing, implementing, revising, and approving the cybersecurity plan of an eligible entity; and assist with the determination of effective funding priorities for grants. |

Yes |

|

Development of a cybersecurity plan |

DHS is required to evaluate and confirm that eligible entities should incorporate any existing plans to protect against cybersecurity risks and threats to state, local, or territorial government information systems. DHS also is to evaluate if eligible entities describe how they will incorporate 16 cybersecurity plan elements and mandatory requirements. |

Yes |

|

Confirmation of pass-through of funds |

DHS is required to evaluate and confirm that eligible entities are required to pass down funds no later than 45-days to local governments and rural areas. Specifically, entities are to pass down 80 percent to local governments and 25 percent of the 80 percent of the total award must go to rural governments. |

Yes |

|

Establishment of a multi-entity group |

DHS may award grants to a multi-entity group to support efforts of the group to address cybersecurity risks and cybersecurity threats to information systems within the jurisdictions of the eligible entities that comprise the multi-entity group. A multi-entity group applying for a grant for the group is required to submit a project plan, which describes the division of responsibilities, distribution of funding, and coordination efforts amongst eligible entities. |

Yes |

|

Obtain grant recipient annual performance progress reports |

Eligible entities must submit a report outlining progress in implementing the cybersecurity plan and addressing cybersecurity risks to DHS no later than 1 year after receiving a grant for implementing the cybersecurity plan, and annually thereafter, until 1 year after the date on which funds from the grant are expended or returned. |

Yes |

Source: GAO analysis of the State and Local Cybersecurity Improvement Act requirements and agency data. | GAO‑25‑107313

As shown in the table, FEMA and CISA, in their capacity as the joint managers of the grant program, met all the requirements for the selected applicants. Specifically:

CISA used its application review process to determine if applicants established a cybersecurity planning committee. CISA reviewed each of the seven selected applicants’ cybersecurity planning committee charters and validated that the charters met the act’s requirement, including that the planning committee met the required composition. Once approved, CISA communicated validation through email to notify the applicant that its planning committee was approved.

CISA used its application review process to determine if applicants developed a cybersecurity plan to include 16 required elements. CISA obtained and reviewed cybersecurity plans and used a checklist to verify that applicants’ plans addressed the required 16 cybersecurity elements. Specifically, CISA evaluated plans and indicated on its checklist if each of the 16 elements were addressed and further identified the page number with the corresponding cybersecurity plan that addresses each element. If all 16 elements were addressed, the cybersecurity plan was considered approved and CISA sent an email to the applicant with a signed letter stating that the cybersecurity plan was approved and meets statutory requirements. If an element was not addressed in the cybersecurity plan, CISA worked with the applicant and provided information needed to address the element.

FEMA used its application review process to determine if applicants passed down funds to local and rural governments. FEMA obtained and reviewed, when appropriate, each applicant’s 45-day signed consent letter indicating that the applicant had met the pass-through requirement to local and rural governments. Specifically, FEMA received two out of seven consent letters from applicants validating that the applicant met the local and rural pass-through of funds requirement for FY 2023. Based on our analysis and confirmation from FEMA officials, for the remaining five applicants, this requirement was either not applicable because the applicant did not submit cybersecurity projects and therefore had not determined how to pass down funds, or the entity was a territory and therefore exempt from this requirement as defined in the act.

FEMA used its application review process to determine if applicants were involved in multi-entity groups (if applicable). If a multi-entity group applies for a grant, FEMA is required to review the group’s project plan and validate that the plan addresses the required cybersecurity elements. None of the seven selected applicants submitted projects that incorporated multi-entity groups.

FEMA received annual progress reports by grant recipients. As part of the grant application package submission, FEMA obtained annual progress reports from the seven selected grant applicants.

In addition to the grant application requirements, the act also requires DHS to submit two reports to Congress. First, the act requires an annual report to Congress that is to include the use of grants awarded, the proportion of grants used to support cybersecurity in rural areas, the effectiveness of the program, and the progress made towards implementing cybersecurity plans. In June 2024, CISA submitted the first State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program annual report to Congress outlining the use of FY 2022 grant funds and the program’s effectiveness, progress towards statewide cybersecurity strategic planning, and reducing cybersecurity risks to SLTT information systems. The report also stated that a follow up report discussing key outcomes from the grant program’s second year (FY 2023) will be released in 2025.

Second, the act requires CISA to submit to Congress a study and legislative recommendations on the potential use, impact, and obstacles with implementing risk-based formulas for apportioning funds of the grant program. The study is also to include any other information determined necessary to inform Congress on the progress towards, and obstacles to, implementing a risk-based formula. CISA has not yet submitted a study and recommendations on the use of a risk-based formula for apportioning grant program funds, which was due on September 30, 2024. According to CISA officials, CISA developed an initial study but decided to take a different approach based on an updated methodology that was not previously available. Officials expect the study to be completed in 2025.

Selected Applicants Met Grant Program Requirements

Grant applicants are required to meet NOFO eligibility requirements for the grant program which are also derived from the act.[16] As previously mentioned, exceptions to eligibility requirements are allowed by the act and DHS.

The seven selected grant applicants met the grant program’s NOFO eligibility requirements for FY 2022 and FY 2023, as applicable. In some instances, DHS allowed exceptions or alternative means to meeting some requirements. For example, there were applicants that did not initially fully meet all requirements for submitting investment justifications and project worksheets, so DHS permitted partially completed applications but held awarded funds until applicants addressed the relevant outstanding requirements at a later time.

FEMA approved selected applications for FY 2022 funding based on eligibility requirements. DHS required applicants to focus on two requirements in FY 2022: establishing a cybersecurity planning committee and developing a cybersecurity plan. The seven applicants met those two requirements for FY 2022 funding. While there were other requirements that applicants were to address, DHS deferred these to allow applicants time to establish a governance structure with subrecipients and to identify gaps in subrecipients’ cybersecurity posture.

FEMA and CISA jointly approved selected applications for FY 2023 funding based on eligibility requirements and allowed exceptions. During the second year of the program (FY 2023), the seven applicants met the FY 2023 NOFO requirements, as applicable. Table 3 describes whether selected grant applicants were approved for FY 2023 funding based on meeting the NOFO eligibility requirements.

Table 3: Extent to Which Selected Applicants Met Fiscal Year 2023 Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) Eligibility Requirements for the Grant Program

|

Requirement |

Description |

Number of selected applicants that met requirement |

|

Establish a cybersecurity planning committee and charter |

Eligible entities must submit the cybersecurity planning committee and charter at the time of application. The charter must include a detailed description of the committee’s composition and define roles and responsibilities. It must also include a detailed description of how decisions on priorities funded through the grant program will be made, among other things. |

7 of 7 |

|

Develop a cybersecurity plan |

Eligible entities must submit a signed cybersecurity plan. The plan must address the entity’s plans to protect against cybersecurity risks and cybersecurity threats to information systems owned by, or on behalf of, state, local, and territorial governments, and describe how feedback from local governments was incorporated. In addition, it must define roles and responsibilities of state, local, and territorial governments and include a timeline for implementing the plan and metrics used to measure implementation of the plan. It also must include a summary of cybersecurity projects and be approved by the cybersecurity planning committee. The plan is to include 16 required cybersecurity elements that represent a broad range of cybersecurity capabilities and activities. |

7 of 7 |

|

Submit investment justification |

Eligible entities must submit an investment justification detailing project-level information regarding how the grant program goals and objectives are met through the development and implementation of the entity’s cybersecurity plan. Only one investment justification form can be submitted for each of the four grant program objectives. |

7 of 7a |

|

Submit project worksheet |

Eligible entities must submit one project worksheet that includes information for each investment justification. The project worksheet is to be used to record all proposed projects with budget details, budget narrative, management and administrative costs, amount and source of cost share. |

7 of 7a |

|

Sign up for Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) services |

Eligible entities must sign up for CISA services such as vulnerability scanning. These services are not required for initial submission and approval of a grant; however, grantees are required to sign up for these services once during the 4-year period of performance. |

5 of 7—two applicants are N/A because they did not sign up for CISA services but have the entire 4-year period of performance to do so. |

|

Conduct nationwide cybersecurity reviews |

Eligible entities must conduct a Nationwide Cybersecurity Review that is administered by the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center during the first year of the award period of performance and annually thereafter.b |

7 of 7 |

|

Request pre-award costs |

Eligible entities can request pre-award costs with approval from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) before the award is announced. |

N/A—none of the seven applicants submitted projects that incurred pre-award costs. |

|

Pass through funds |

Eligible entities must pass through at least 80 percent of awarded funds to local governments and at least 25 percent of the 80 percent of the total award must go to rural governments, within 45 calendar days of receipt of the funds. |

7 of 7a |

|

Meet cost share |

Eligible entities must meet a 10 percent cost share requirement for fiscal year 2022 and 20 percent for fiscal year 2023 grant program funding. Cost share requirements are waived for insular areas of the U.S. territories of American Samoa, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. |

7 of 7a |

|

Submit environmental planning and historic preservation documentation |

Eligible entities that propose projects with the potential to impact the environment, such as constructing communication towers, modification or renovation of existing buildings or structures, or replacing facilities, must submit detailed project descriptions and supporting documentation for FEMA to determine whether the proposed project has the potential to impact environmental resources or historic properties. |

N/A—none of the seven applicants submitted projects that required environmental planning and historic preservation documentation. |

|

Submit financial, performance progress, and single audit reports |

Eligible entities must submit a quarterly federal financial report that identifies obligations and expenditures and an annual performance progress report that includes a brief narrative of project status, summary of project expenditures, description of potential issues that may affect project completion, and data collected for Department of Homeland Security (DHS) performance measures. Entities that expended $750,000 or more during their fiscal year must submit a single audit report. |

7 of 7 |

|

Submit closeout reporting |

Within 120 calendar days after the end of the period of performance for the award, eligible entities must liquidate all financial obligations and submit a final federal financial report and performance progress report. |

N/A—none of the grant program awards have been closed out due to the 4-year period of performance. |

Source: GAO analysis of grant program documentation. | GAO‑25‑107313

aDHS allowed exceptions or alternative means to meeting this requirement in fiscal year 2023 that, for our reporting purposes, we are considering as having met the requirement outlined in the NOFO.

bThe Nationwide Cybersecurity Review is a free, anonymous, annual self-assessment designed to measure gaps and capabilities of state, local, tribal, and territorial governments’ cybersecurity programs. It is based on the National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework and is sponsored by DHS and the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center. The Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center is an independent, nonprofit organization that was designated by DHS in 2010 as the cybersecurity information sharing and analysis center for state, local, tribal, and territorial governments.

During the second year of the program (FY 2023), applicants were approved based on the NOFO requirements and allowed exceptions. Specifically:

Cybersecurity planning committee and charters. All seven applicants submitted a cybersecurity committee charter that included their Chief Information Officer, Chief Information Security Officer, and representatives from within the state and territory.

Cybersecurity plans including 16 required cybersecurity elements. All seven applicants submitted a cybersecurity plan that included all 16 required elements that were approved and signed by the Cybersecurity Planning Committee and the Chief Information Officer and/or Chief Information Security Officer.

Investment justifications. All seven applicants submitted investment justifications when appropriate for FY 2023 detailing how the grant program objectives and goals will be met as appropriate. Although the NOFO required an eligible entity to submit an investment justification and align cybersecurity projects to the four grant program objectives, as previously mentioned, DHS allowed an exception to meeting this requirement. For example, two applicants marked “to be determined” as they had not submitted projects for approval by CISA. FEMA officials stated that the agency allowed applicants to submit investment justifications and marked “to be determined” if applicants were not prepared to submit projects for approval by CISA.

Project worksheets. All seven applicants submitted project worksheets that included information for each investment justification and aligned to the grant program objectives for FY 2023, as applicable. Similar to the investment justification, DHS also allowed an exception to meeting this requirement. For example, five applicants marked “to be determined” as they had not submitted projects for approval by CISA. Although the NOFO required an eligible entity to submit a project worksheet that aligns cybersecurity projects to the four grant program objectives, FEMA officials stated that applicants who were not prepared to submit projects at the time of application were permitted to submit a project worksheet that stated “to be determined.” As previously mentioned, funds are on hold until applicants submit projects and CISA approves them.

CISA cyber hygiene services. Five of the seven applicants signed up for cyber hygiene services, as appropriate. Although the NOFO required grantees to sign up for CISA services such as vulnerability scanning, these services and membership are not required for submission and approval of a grant. DHS officials stated that applicants are required to sign up for these services at least one time during the 4-year period of performance. CISA checked if applicants had signed up during its monitoring visit at states and territories and also checked its internal records to determine if applicants had fulfilled this requirement.

Nationwide Cybersecurity Review.[17] All seven applicants completed a cybersecurity review in FY 2023. According to CISA, this was an annual requirement regardless of if the applicant submitted cybersecurity projects or not and was not directly tied to any specific projects but rather required states and territories to obtain an assessment of their cybersecurity posture at large.

Pre-award costs. FEMA confirmed that none of the seven selected applicants submitted projects that incurred pre-award costs.

Pass-through requirements to local and rural governments. While two of the seven applicants met the pass-through requirement, this requirement was either not applicable or was exempted for the remaining five. Specifically, for FY 2023, four applicants did not submit projects for approval which negated the requirement to submit a 45-day consent letter to FEMA certifying that funds were passed through to local and rural governments. One applicant was a territory and therefore was exempt from meeting the pass-through requirement.

Cost share reports. Although all applicants submitted a cost share report within their project worksheets for FY 2023, five applicants did not identify cybersecurity projects. According to FEMA, applicants that did not identify projects were allowed to apply with applications that stated “to be determined.” DHS made an exception to meeting this requirement for applicants that were not prepared to submit cybersecurity projects. In addition, some applicants submitted and were approved for cost share waivers.

Environmental planning and historical preservation review. FEMA confirmed that none of the seven selected applicants submitted cybersecurity projects that would impact them to submit environmental planning and historical preservation documentation.

Federal financial reports, performance progress reports, and single audit reports. All seven applicants met the requirement to submit these reports to FEMA, as appropriate. All seven applicants submitted a federal financial report. Also, all seven applicants submitted progress reports for calendar year 2023. Within the progress report, applicants were required to outline a brief narrative and overall status of cybersecurity projects. However, although applicants submitted progress reports, all seven applicants had no progress to report for calendar year 2023, due to funds being held because applicants had not submitted projects or spent the funds. In addition, regarding the single audit reports, applicants were required to file a report if they spent $750,000 or more for the fiscal year. All seven applicants met the threshold amount and submitted their single audit reports to FEMA.

Closeout reports. This requirement was not applicable for all seven applicants. According to FEMA, none of the grant program awards have been closed out as of January 2025 due to the 4-year period of performance for each award.

Selected SAAs Reported Their Views on the Grant Program, Including Positive Feedback and Concerns

SAA officials we interviewed about the grant program provided positive feedback on FEMA’s communications, guidance, and funding. Officials also reported challenges with the program and concerns with sustaining cybersecurity projects after the grant program ends. Selected officials reported their plans for sustaining projects by using other grant programs or seeking future funds at the state and local level.

Selected SAAs Reported Positive Feedback About the Grant Program

Five of nine SAAs commented favorably about FEMA’s efforts to facilitate open and constant communication, respond to feedback, and make improvements to the second iteration of the NOFO. For example, four SAAs had positive feedback about FEMA’s monthly office hours to facilitate open and constant communication for states and territories to ask questions about the grant program or to share lessons learned.

In addition, SAA officials noted that FEMA and their local CISA coordinators provided the necessary guidance to have a better experience in the second funding year. Specifically, the officials stated that FEMA solicited feedback from them and subsequently improved the FY 2023 NOFO. According to CISA officials, CISA conducted outreach and provided educational awareness to local subrecipients, which resulted in an increase in applications during the second funding year of the program.

SAA officials also provided positive feedback about the funding received from the grant program. For example, an official from one SAA stated that many of the current and proposed cybersecurity projects and assessments would not have been possible at the local level without the grant program.

In addition, DHS’s June 2024 annual report to Congress discussed positive results from the program. Specifically, the report stated that the program had enabled CISA to establish an initial baseline measurement of the current SLTT cybersecurity posture. This measurement was based on eligible entity’s required self-assessments, both through the cybersecurity planning process and the Nationwide Cybersecurity Reviews administered by the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center.

Selected SAAs Identified Challenges in Implementing the Grant Program and Some Have Developed Mitigation Plans

Although officials reported positive feedback about the grant program, all nine selected SAAs identified several other ongoing challenges with implementing the grant program. Specifically, SAAs identified challenges with completing and submitting grant applications and meeting the cost share requirement. FEMA and SAAs described plans to address the challenges.

Completing and submitting grant applications. Eight selected SAAs faced challenges with completing and submitting grant applications during the first program funding year. For example, officials cited their own administrative challenges with inexperienced grants management staff and turnover of personnel that led to challenges with submitting the grant application efficiently. Specifically, one SAA experienced a turnover in its grants specialist, who was responsible for submitting applications in FEMA’s grants management system. As a result, the SAA experienced difficulties obtaining permissions in FEMA’s system, as the system is set up to only allow one person to submit applications. FEMA is currently working on a solution with its new grants system to resolve this issue.

Meeting the cost share requirement. Officials from six SAAs reported challenges with meeting the cost share requirement. For example, an official from one SAA stated that it is difficult for smaller communities to participate in the grant program because they cannot meet the cost share requirement, whereas larger communities are able to absorb the cost share. In addition, another SAA official stated that they were unsure whether local entities could meet the cost share requirement if the waiver is not approved for FY 2024 funding and noted that FY 2025 will be even more difficult, since the cost share requirement will increase to 40 percent. Furthermore, another SAA official stated that they could not meet the FY 2022 10 percent cost share requirement, so they requested and were granted a waiver for that requirement for both FY 2022 and FY 2023.

SAA officials indicated that they will continue to seek ways to overcome these challenges within their state and local governments and provide grant program funding to localities. In addition, FEMA and CISA officials stated that their agencies will continue to obtain feedback from SAAs and work with them to improve grant applications for the remainder of the grant program period of performance.

All Selected SAAs Identified Concerns with Sustaining Project Funding When the Program Ends and Some Identified Plans to Address These Concerns

In addition to reporting challenges with the grant program, seven selected SAAs reported concerns with sustaining funding when the program ends after its fourth funding year. Two officials described internal budget constraints on sustaining funding for cybersecurity projects. For example, one SAA official stated that smaller municipalities may be “deciding between spending on paving roads or cybersecurity practices.” The official added that these types of risk management decisions could create vulnerabilities in the state’s cybersecurity posture. To mitigate the internal budget constraints, one SAA required subrecipients to include how they will sustain projects in their plans.

Another SAA official commented that sustainment will be an issue for all local entities who have applied for the grant program because many localities have no other means of funding to allocate to cybersecurity. The official also said that their state office could help cover some of the matching requirements, but not enough to cover all cybersecurity investments.

Further, an official from one SAA stated that introducing cybersecurity in their state government as a priority is difficult because there is no clear mandate that explicitly requires organizations to assign a percentage of funding to cybersecurity. Instead, all cybersecurity investments must be justified and include why the projects are critical.

Officials from three SAAs emphasized the importance of reauthorizing the grant program after it sunsets on September 30, 2025.[18] For example, one SAA official stated that it would be detrimental to the state’s cybersecurity efforts if the grant program is not reauthorized. Another SAA official said that reauthorization would help their state with cybersecurity given their limited resources.

SAAs’ plans to address concerns with sustaining funds

Over half of the nine SAAs we interviewed planned to address concerns with sustaining funds by using other grant programs or seeking future budgets at the state and local level.

Using other FEMA grant programs. Officials from seven SAAs plan to use other FEMA grant programs, such as the Homeland Security Grant Program, to attempt to continue funding cybersecurity projects when the grant program ends. However, five SAAs stated that these funds would not be enough to cover all cybersecurity grant program projects because of other funding priorities required by the Homeland Security Grant Program. For example, an official from one SAA stated that 80 percent of the Homeland Security Grant Program funding is passed through to municipalities while 20 percent remains at the higher government level, of which 5 percent is for management and administration of the grant. Remaining funds are then allocated to the state’s fusion center. Therefore, there is not enough to sustain projects that were initiated with the cybersecurity grant program.[19] The official also noted that the entity received a 10 percent decrease in the Homeland Security Grant Program during the time of this review.

Nevertheless, these SAAs plan to use the Homeland Security Grant Program to continue funding projects when the cybersecurity grant program ends. Regarding the use of the Homeland Security Grant Program to sustain funding for projects, FEMA officials stated that SAAs can apply for funding under the program because “enhancing cybersecurity” remains a national priority area, so applicants can apply for grants to fund cybersecurity-related projects.

Seeking future state and local-level funds. An official from one SAA plans to advocate to their state legislature for a dedicated line item in their states’ local government budget specifically for cybersecurity. Another SAA official described a similar approach to sustaining funding at the statewide level through shared services. In addition, an official from one SAA stated that subrecipients were not allowed to draft an application without addressing sustainment at the local level. The official further noted that they required all subrecipients to describe how they will sustain projects in their plan. Nevertheless, the SAA plans to utilize state-level budget or local city budgets to sustain projects.

Agency Comments

We requested comments on a draft of this report from DHS. We received only technical comments from the department, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to appropriate congressional committees, the Department of Homeland Security, and other interested parties. In addition, this report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff members have any questions about this report, please contact David B. Hinchman at HinchmanD@gao.gov or Tina Won Sherman at ShermanT@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made major contributions to this report are listed in appendix II.

David B. Hinchman

Director, Information Technology and Cybersecurity

Tina Won Sherman

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

The National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework is intended to provide guidance to industry, government agencies, and other organizations to manage cybersecurity risks. It offers a taxonomy of high-level cybersecurity outcomes that can be used by any organization to better understand, assess, prioritize, and communicate its cybersecurity efforts. It consists of six core functions: govern, identify, protect, detect, respond, and recover. Within the six functions are 22 categories (see table 4).[20]

Table 4: Summary of the National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework Core Functions

|

Framework |

Description |

Categories |

|

Govern |

Govern cybersecurity risks to ensure that services are established, communicated, and monitored. |

organizational context risk management strategy roles, responsibilities, and authorities policy oversight cybersecurity supply chain risk management |

|

Identify |

Identify cybersecurity risks to systems, people, data, and capabilities to improve the organization’s cybersecurity posture and conduct asset management assessments. |

asset management risk assessment improvement |

|

Protect |

Protect the organization’s systems, people, data, and capabilities through appropriate safeguards and limits or contain the impact of a potential cybersecurity event through workforce training and enhancing security. |

identity management, authentication, and access control awareness and training data security platform security technology infrastructure resilience |

|

Detect |

Detect cyberattacks in an effective and timely manner, using appropriate activities like continuous monitoring capabilities or endpoint protection products. |

continuous monitoring adverse event analysis |

|

Respond |

Respond to detected cybersecurity incidents in an effective and supportive manner in the context of recovery activities like forensics and development of incident response plans to improve the ability to monitor, evaluate, and assess cyber incident responses. |

incident management incident analysis incident response reporting and communication incident mitigation |

|

Recover |

Recover from a cybersecurity incident of assets and operations in the context of restoring operation from a cyber incident, communicating restoration activities with stakeholders, and notifying the public of recovery efforts. |

incident recovery plan execution incident recover communication |

Source: National Institute of Standards and Technology. | GAO‑25‑107313

GAO Contact

David B. Hinchman at HinchmanD@gao.gov

Tina Won Sherman at ShermanT@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contacts named above, the following staff made key contributions to this report: Michael Gilmore (Assistant Director), Hugh Paquette (Assistant Director), Kavita Daitnarayan (Analyst in Charge), Tracey Bass, Jillian Clouse, Alex Engel, Smith Julmisse, Jess Lionne, Dwayne Staten, Andrew Stavisky, and Adam Vodraska.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, High-Risk Series: Urgent Action Needed to Address Critical Cybersecurity Challenges Facing the Nation, GAO‑24‑107231 (Washington, D.C.: June 13, 2024).

[2]State and Local Cyber Security Improvement Act, Pub. L. No. 117-58, Div. G, Title VI, Sub. B § 70612(a), 135 Stat 429, 1272-1285 (2021), codified at 6 U.S.C. § 665g.

[3]The Department of Homeland Security, Notice of Funding Opportunity Fiscal Year 2022 State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 16, 2022).

[4]National Institute of Standards and Technology, The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) 2.0 (Gaithersburg, MD: Feb. 26, 2024). The NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 is intended to provide guidance to industry, government agencies, and other organizations to manage cybersecurity risks. It offers a taxonomy of high-level cybersecurity outcomes that can be used by any organization to better understand, assess, prioritize, and communicate its cybersecurity efforts.

[5]6 USC § 665g(b).

[6]The NOFO includes all requirements and details, including information on funding eligibility for states and territories.

[7]The District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands are exempt from the local government and rural pass-through requirement, as outlined in the act.

[8]In September 2023, DHS announced the Tribal Cybersecurity Grant Program. All 574 federally recognized Tribal Governments are eligible to apply for this grant program dedicated to supporting tribal cybersecurity resiliency. The funding apportioned for tribal governments was $6 million in FY 2022 and over $12.2 million for FY 2023. FEMA and CISA combined these into a single funding notice for a total of approximately $18.2 million. Tribes that apply have to submit cybersecurity plans, cybersecurity planning committee lists, and charters. Tribes had to apply by January 10, 2024, before they could receive award funding.

[9]The Office of the National Cyber Director, following consultation with the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Playbook for Strengthening Cybersecurity in Federal Grant Programs for Critical Infrastructure (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 17, 2024).

[10]GAO, Federal Grants: Numerous Programs Provide Cybersecurity Support to State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial Governments, GAO‑24‑106223 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 16, 2023).

[11]FEMA’s five grant programs included: Homeland Security Grant Program, Transit Security Grant Program, Port Security Grant Program, Emergency Management Performance Grant Program, and Tribal Homeland Security Grant Program.

[12]Specifically, eligible entities are to pass down 80 percent to local governments and 25 percent of the 80 percent of the total award must go to rural governments.

[13]Enhanced logging is a process that encrypts event logs for safe transport to the support administrators. It also provides information in the event log to help administrators troubleshoot issues they may encounter with specific devices.

[14]NIST defines data at rest as data that is stored and not being accessed or used, typically on a computer’s hard disk or server. Data in transit is referred to as the movement of data from one location to another, such as when it is being transmitted over a network or the internet.

[15]The act promotes the delivery of safe, recognizable, and trustworthy online services, including through the use of the .gov internet domain.

[16]The Department of Homeland Security, Notice of Funding Opportunity Fiscal Year 2023 State and Local Cybersecurity Grant Program (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 7, 2023).

[17]The Nationwide Cybersecurity Review is a free, anonymous, annual self-assessment designed to measure gaps and capabilities of SLTT governments’ cybersecurity programs. It is based on the NIST Cybersecurity Framework and is sponsored by DHS and the Multi-State Information Sharing and Analysis Center.

[18]6 U.S.C. § 665g(s)(1).

[19]In general, fusion centers provide a mechanism for multiple federal, state, local, and territorial entities to collaborate and share resources, expertise, and information. Their goal is to maximize the ability to detect, prevent, investigate, and respond to all hazards, including criminal or terrorist threats. See 6 U.S.C. § 124h(k)(1).

[20]National Institute of Standards and Technology, The NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 (Gaithersburg, MD: Feb. 26, 2024).