GRANTS MANAGEMENT

Recent Guidance Could Enhance Subaward Oversight

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Jeff Arkin at (202) 512-6806 or ArkinJ@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107315, a report to congressional requesters

Recent Guidance Could Enhance Subaward Oversight

Why GAO Did This Study

In fiscal year 2024, the federal government obligated roughly $1.2 trillion in grants to support national priorities. Grant recipients can pass through these funds to subrecipients in the form of a subaward. GAO and Office of Inspectors General audits have found persistent issues with the completeness and accuracy of subaward information. This makes it challenging to track where subaward funds are ultimately spent and can increase the risk for fraud and misuse of federal funds.

GAO was asked to review various issues related to subaward oversight. This report describes (1) common issues related to subaward oversight identified through single audits; (2) how selected federal agencies and grant programs implement their subaward oversight requirements; and (3) recent changes to regulations and guidance that could enhance subaward oversight.

GAO analyzed single audit findings from the Federal Audit Clearinghouse to identify common compliance issues related to subaward oversight. GAO met with officials from IIJA grant programs with funds distributed as subawards to describe examples of federal subaward oversight. GAO also reviewed recent changes to relevant regulations and guidance and discussed how they could improve subaward oversight with OMB staff.

We provided a draft to our three selected agencies and OMB for comment. One agency provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate, and two responded with no comments. OMB did not provide comments.

What GAO Found

The Single Audit Act requires non-federal entities that expend above a certain amount in federal awards in a fiscal year to undergo a single audit—an audit of an entity's financial statements and federal awards—or in select cases a program-specific audit. GAO analyzed 3,680 single audit findings from 2022 to 2024 addressed to recipients that received a grant award from a federal agency and passed funds through to another entity, or subrecipient, in the form of a subaward. According to this analysis, 36 percent of these findings were primarily associated with one of the following topics:

· Incomplete

subaward reporting. Some of these grant recipients did not fulfill required

reporting of subawards to the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency

Act Subaward Reporting System (FSRS) for display on USAspending.gov. This

limits the transparency of federal funding and makes it challenging to track

these funds for oversight purposes.

· Subrecipient

monitoring activities. Some of these grant recipients did not monitor their

subrecipients’ activities or did not review audit reports for their

subrecipients, which impairs their oversight of those subrecipients.

· Verifying or justifying eligibility decisions. Some of these grant recipients did not ensure that their subrecipients were eligible to receive federal funds, which can put those funds at risk for fraud.

While grant recipients are responsible for overseeing their subawards, federal agencies are to ensure the grant recipients they make awards to carry out their oversight responsibilities. GAO selected an example grant program with subrecipients from each of the three agencies that received the largest amounts of Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) funding. Officials from these programs described a variety of approaches to support subaward oversight, such as reviewing recipients’ budgets, progress reports, and audit findings.

In 2024, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) took steps that could enhance federal subaward oversight. These steps include:

· amending

the Code of Federal Regulations to direct agencies to review single audit

findings to non-federal entities—including subrecipients—which could broaden

agencies’ awareness of challenges affecting their programs;

· issuing

a memorandum directing agencies to update their award terms to clearly convey

the requirement for grant recipients to provide complete subaward descriptions

in their reports to FSRS, which should result in clearer information available

to the public about federal spending; and

· addressing GAO’s prior recommendation to clarify agencies’ role in supporting subaward data quality by issuing a memorandum directing agencies to hold their grant recipients accountable for reporting subawards to FSRS, which should lead to more complete subaward data being publicly available on USAspending.gov.

GAO will continue to monitor subaward oversight and transparency as agencies take steps to implement this guidance.

Abbreviations

|

API |

application programming interface |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FAC |

Federal Audit Clearinghouse |

|

FFATA |

Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency |

|

|

Act of 2006 |

|

FSRS |

Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency |

|

|

Act Subaward Reporting System |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

LDA |

Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

|

OIG |

Office of Inspector General |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

UTC |

University Transportation Centers |

|

Weatherization |

Weatherization Assistance Program for Low-Income Persons |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

March 26, 2025

The Honorable James Lankford

Chairman

Subcommittee on Border Management,

Federal Workforce, and Regulatory Affairs

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Joni Ernst

United States Senate

The Honorable Margaret Wood Hassan

United States Senate

In fiscal year 2024, the federal government obligated roughly $1.2 trillion in grants to tribal, state, local, and territorial governments to support national priorities. Grant recipients, such as states, can pass through these funds to other entities in the form of a subaward to help carry out a portion of the work associated with a grant.[1]

Our prior work, and that of federal Offices of Inspector General (OIG), have found persistent issues with the completeness and accuracy of publicly available information on subawards. For example, our prior work found that a lack of robust data entry validations and unclear guidance limited the quality of subaward data displayed on USAspending.gov.[2] These issues make it challenging to track where subawards are ultimately spent and for what purpose. Likewise, OIG and single audit reports have also identified a number of issues with subaward reporting and oversight, including instances of subawards not being reported properly, grant recipients not performing required risk assessments of subrecipients, and grant recipients not reviewing single audit reports for their subrecipients.[3]

You asked us to review various issues related to subaward oversight. This report describes (1) common issues related to subaward oversight identified through single audits, (2) how selected federal agencies and grant program offices implement their grant subaward oversight requirements, and (3) recent changes to regulations and guidance that could enhance subaward oversight.

To identify common subaward oversight issues identified through single audits, we analyzed single audit findings using a form of text analytics called topic modeling to identify themes in the contents of over 7,000 single audit reports from audit years 2022 to 2024, spanning over 30 grant awarding agencies.[4] We also reviewed federal government oversight reports related to subaward oversight.

To describe how selected federal agencies implement their subaward oversight requirements, we selected three example agencies and grant programs. We used data from USAspending.gov to identify agencies that received the most Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) grant funding and programs that had reported subawards.[5] We also interviewed knowledgeable officials from our selected agencies and program offices, and reviewed documentation related to their grant and subaward management activities.

To describe recent changes in the requirements on awarding agencies and grant recipients for subaward oversight, we reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and guidance, including Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) final rule issued in April 2024, which took effect in October 2024. We interviewed OMB staff about recent updates to regulations and guidance memorandums to confirm our understanding of their purposes. For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

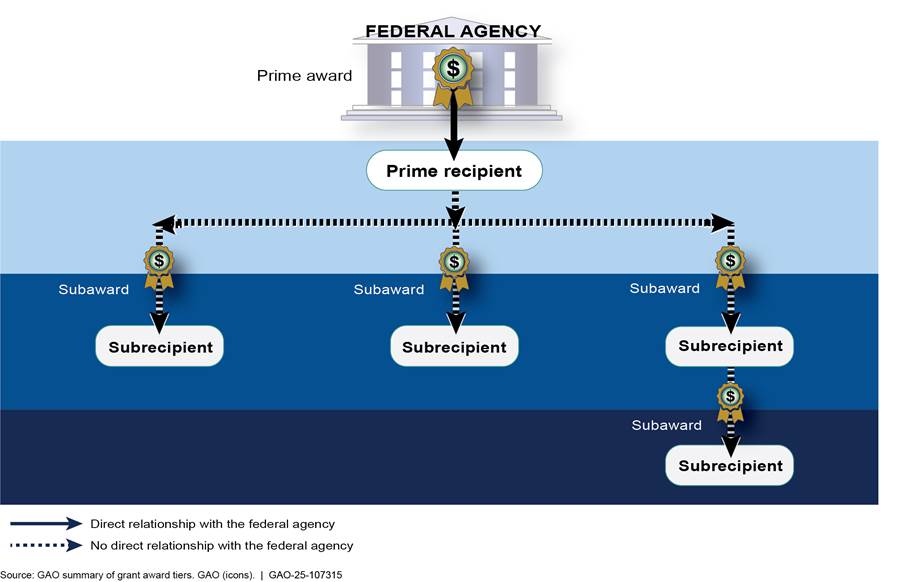

Federal grant subawards are made when a recipient that received a grant award from a federal agency—known as the prime recipient—passes some amount of that award to a subrecipient to carry out part of the work associated with the grant award. Subawards made by prime grant recipients are referred to as first-tier subawards.[6] Federal awarding agencies do not have a direct legal relationship with subrecipients. Instead, oversight responsibility for first-tier subawards belongs to the prime recipients of federal awards (see fig. 1).[7]

Federal regulations assign several oversight responsibilities to pass-through entities for the subawards they make.[8] For prime recipients that pass through funds as subawards, these responsibilities include:

· confirming that subrecipients are not suspended or debarred from receiving federal funds;

· evaluating subrecipients’ risk of committing fraud;

· reporting subaward information to the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act Subaward Reporting System (FSRS), as required;[9]

· ensuring subrecipients undergo single audits, if required, and that they address findings from those audits; and

· monitoring the activities of their subrecipients as necessary.[10]

Although federal agencies that award prime grants do not have a direct legal relationship with subrecipients of those grants, they provide indirect oversight of subawards by ensuring prime recipients carry out their subaward oversight responsibilities.[11] The role for awarding agencies includes:

· approving prime recipients’ subaward activities that were not previously approved as part of their application;

· communicating subaward oversight and reporting requirements to prime recipients;

· collecting and reviewing regular performance reports from prime recipients, which can include information on subrecipients and their activities;[12]

· reviewing and addressing findings from single audits, which can include findings on prime recipients’ monitoring of subawards; and

· holding prime recipients accountable for reporting required subawards to USAspending.gov via FSRS.[13]

Common Subaward Compliance Issues Emerged from Single Audit Findings

To identify common compliance issues related to subaward oversight, we used a statistical approach called topic modeling to analyze relevant findings from single audits.[14] We selected audit findings from audit years 2022 to 2024 that were addressed to prime recipients that passed funds through to another entity in the form of a subaward. Through our topic model we identified nine topics, three of which we determined were most relevant to subaward oversight and compliance issues. Of the 3,680 single audit findings we selected for this analysis, 1,332 (36 percent) were primarily associated with one of these three topics.

Incomplete subaward reporting.[15] According to our model, 517 (14 percent) of the 3,680 findings we selected for this analysis were most closely associated with the topic we refer to as “FFATA reporting.” Findings associated with this topic commonly noted that data about subawards required to be reported under FFATA were either not reported, not reported timely, or reported incorrectly. For example, one single audit finding associated with this topic described testing a sample of 96 subawards and found that over half of those, totaling over $130 million in obligations, were not reported to FSRS.[16] Subawards not reported to FSRS are not visible to the public via USAspending.gov, limiting the transparency of federal funding and making it challenging to track these funds for oversight purposes.

We examined the single audit findings most closely associated with this topic to identify shared root causes.[17] Based on that analysis, we found:

· at least 199 (38.5 percent) were attributed to the prime recipient having deficient internal controls to fully comply with their subrecipient monitoring responsibilities;

· at least 99 (19.1 percent) were attributed to the prime recipient not understanding or being aware of federal requirements;

· at least 78 (15.1 percent) were attributed to mistakes or errors, including miscalculations;

· at least 44 (8.5 percent) were attributed to personnel limitations, such as inadequate staff and turnover; and

· at least 15 (2.9 percent) were attributed to the auditee lacking evidence, such as documents, records, or tracking.

Subrecipient monitoring activities.[18] According to our model, 482 (13 percent) of the 3,680 findings we selected for this analysis were most closely related to the topic we refer to as “assorted subrecipient monitoring activities.” The findings most closely associated with this topic included deficiencies such as not monitoring the activities of subrecipients, not conducting a required risk assessment for subrecipients, and not ensuring that subrecipients underwent required single audits or failing to review single audit reports.

According to our analysis of the cause statements related to these findings, we found that:

· at least 224 (46.5 percent) were attributed to the prime recipient having inadequate internal controls to fully comply with their subrecipient monitoring responsibilities;

· at least 41 (8.5 percent) were attributed to personnel limitations, such as inadequate staff and turnover;

· at least 39 (8.1 percent) were attributed to mistakes or errors, including miscalculations;

· at least 31 (6.4 percent) were attributed to the prime recipient not understanding or being aware of federal requirements; and

· at least 30 (6.2 percent) were attributed to the auditee lacking evidence, such as documents, records, or tracking.

Verifying or justifying eligibility decisions.[19] According to our model, 333 (9 percent) of the 3,680 findings we selected for this analysis were most closely related to the topic we refer to as “verifying or justifying eligibility decisions.” Prime recipients of federal funds that plan to make a subaward must first check that intended subrecipients are not suspended or debarred from receiving federal funding. This can be done by checking the list of suspended and debarred entities on SAM.gov.[20] If recipients award federal funds to subrecipients without conducting the required suspension and debarment checks, then those funds are at risk of being spent fraudulently.

According to our analysis of the cause statements in the findings most closely associated with this topic:

· at least 101 (30 percent) were attributed to the prime recipient having deficient internal controls to fully comply with their subrecipient monitoring responsibilities;

· at least 42 (12.6 percent) were attributed to the prime recipient not understanding or being aware of federal requirements;

· at least 37 (11.1 percent) were attributed to the auditee lacking evidence, such as documents, records, or tracking;

· at least 20 (6 percent) were attributed to simple mistakes or errors, including miscalculations; and

· at least 13 (3.9 percent) were attributed to personnel limitations, such as inadequate staff and turnover.

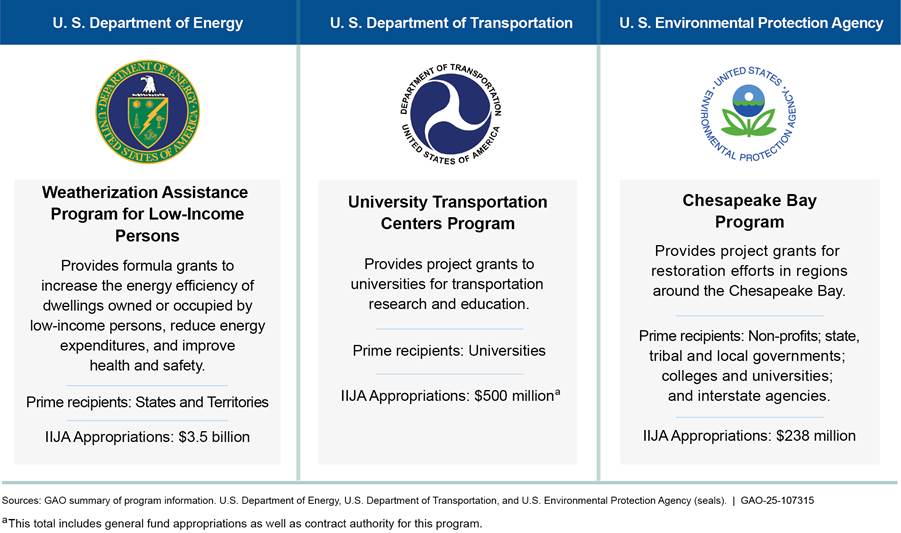

Selected Agencies Use a Variety of Approaches to Conduct Subaward Oversight

Selected grant program officials we spoke to told us about a variety of approaches they take to implement their subaward oversight responsibilities. We selected three financial assistance programs from the Department of Energy (DOE), the Department of Transportation (DOT), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which were the three agencies that received the largest amounts of IIJA funding, to provide examples of how they conduct oversight of subawards.[21] We selected these example programs based on funding they had received and their experience with subawards. See figure 2 for more information on our selected example programs.

Figure 2: Selected Programs with Subawards That Received Funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)

Approving Planned Subaward Budgets in Prime Recipients’ Applications

Recipients can include information about proposed subawards with their grant application. This information can include the total amount the prime recipient plans to pass through to subrecipients, details about anticipated subrecipients, and the amount each subrecipient would be slated to receive. Recipients must receive written approval for subaward activities that were not previously approved as part of their application from the agency or pass-through entity that made the award.

Officials we spoke to from our selected programs provided us different examples of what these proposed budgets contain. For example, applications for DOE’s Weatherization Assistance Program for Low-Income Persons (Weatherization) include budgets with specific columns for subrecipient administration, and training and technical assistance for subrecipients.[22] DOE officials told us that for competitive grants, applicants are to identify potential subrecipients in their grant proposals as well as provide an estimated budget that would include subawards, certain equipment to be used, and a written description of what the subrecipients’ contributions to the overall project will be. Additionally, DOE officials told us that Weatherization prime recipients are required to submit a plan that outlines how the prime recipient will administer the funds and ensure compliance with requirements and that includes a list of planned subrecipients.

Colleges and universities applying for grants under DOT’s University Transportation Centers (UTC) program as a lead institution include proposed budgets for each intended consortium member institution in their application.[23] DOT officials told us they consider the consortium of colleges and universities to be a team of partners, and the award decisions are made based on all the institutions involved in a proposed consortium.

If a prime recipient proposes subaward activities not previously proposed and approved in the federal award, they must submit a written request to the awarding agency and have that request approved.[24] For example, DOE officials shared an example of a Weatherization recipient’s modified annual plan that added a subrecipient that was not in the original plan. The modification included the new subrecipient’s name and revised subaward amount for each planned subrecipient.[25] Officials from UTC and the Chesapeake Bay Program told us they had not received any requests to change funding to subawards after an original grant agreement was made.

Ensuring Prime Grant Award Recipients Report Required Subaward Information

Prime recipients are required to report subawards greater than or equal to $30,000 for display on USAspending.gov, via FSRS, by the end of the month after the month in which the award was made.[26] For example, a reportable subaward made in November must be reported to USAspending.gov via FSRS by the end of December.

Agency officials shared some examples of activities that are intended to ensure prime recipients report required subaward information. For example, EPA officials told us they check FSRS as part of their annual review of each grant recipient to ensure subawards have been reported for the Chesapeake Bay Program.[27] EPA’s internal guidance for this review contains detailed instructions on accessing FSRS.gov to check whether grant recipients have reported their subawards. EPA officials also reach out to prime recipients that have not reported their subawards to FSRS to remind them of their reporting requirements.

DOE officials told us that they did not regularly check FSRS reporting for recipients of the Weatherization program.[28] DOE officials told us that they are working on improving the subaward data in FSRS for the Weatherization program by developing a report that merges data from several systems to identify prime recipients that are not reporting subawards. DOE officials also told us they plan to send a reminder to those prime recipients that have made subawards above the required reporting threshold regarding their FSRS reporting requirements, which could help improve the completeness of Weatherization subaward reporting.

Collecting Regular Progress Reports from Grant Recipients

Federal regulations generally require prime recipients to submit regular reports on their progress implementing grant awards to awarding agencies on at least an annual but no more than a quarterly basis.[29] These periodic reports help agencies ensure program goals are being met and can contain information on subrecipients and the work they are conducting.

The content of progress reports varied across our selected programs. For example, the progress reports we reviewed for the Weatherization program presented total numbers of weatherized units in a state or territory during the reporting period and over the life of the grant to date. These quarterly reports contained additional information on the work conducted, such as the number of weatherized units by primary heating fuel and type of occupant.[30]

Progress reports we reviewed for the UTC program included descriptions of research projects subrecipients were conducting. DOT officials told us that prime recipients submit progress reports every 6 months using a standardized template that describes major goals of the program; research projects being undertaken; and accomplishments in areas such as research, education, and workforce development. They also noted that there are individual reports submitted for each research project across the centers that include a description of the project and its effects, and that each transportation center is required to have a website where they post information on the research conducted.[31]

Reviewing Findings from Single Audits and Office of Inspector General Reports

Under the Single Audit Act and OMB’s implementing guidance, non-federal entities that expend $1 million or more in federal awards in their fiscal year are generally required to undergo a single audit.[32] If a single audit identifies certain deficiencies, then these single audit findings must be included in the reporting package that the recipient submits to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse (FAC).[33] Single audits typically include a financial review of an entity’s expenditures of federal awards, and a compliance review related to its major grant programs that typically covers issues such as cash management, equipment and real property management, and allowable costs. Single audit findings can be relevant to subawards even when the auditee is not a subrecipient.[34] For example, single audits of prime recipients can find compliance issues with the auditee’s subrecipient monitoring or reporting, which could include reporting subawards to FSRS. While single audits are an important component of oversight, they do not cover all recipients of federal funds, all federal programs, or all funding types.[35]

Officials we spoke to across our selected agencies took a variety of approaches when reviewing single audit findings.[36] For example, DOE officials told us single audits are a component of their annual risk assessment process for the states and territories that are the prime recipients of Weatherization program funds. These officials also told us that a single audit coordinator tracks and reviews single audit findings for prime recipients that receive Weatherization funds, as well as other findings related to DOE financial assistance programs. According to DOE officials, these findings might not be related to the Weatherization program specifically, but any weaknesses in internal controls identified for a prime recipient could also affect the implementation of the Weatherization program. DOE officials also stated that single audits of Weatherization prime recipients generally do not focus on the quality of subrecipient oversight because Weatherization prime recipients are large jurisdictions—states and territories—for whom Weatherization spending is a relatively small portion of the total amount of federal financial assistance they expend.

DOT officials told us that DOT’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) identifies single audit findings affecting DOT programs and coordinates with the Office of the Secretary of Transportation to track them using an agency-wide database. This information is also shared with relevant DOT program offices to implement a plan for remediating audit findings and with prime recipients to address any questioned costs.[37] DOT officials told us that once a finding is resolved, the Office of the Secretary works with DOT’s OIG to document and provide evidence of the action that was taken to address the finding.[38] DOT OIG officials told us they issue quarterly summary reports on significant single audit findings, and that these reports focus on instances where DOT is the cognizant agency and the finding affects directly awarded DOT programs.[39] If DOT is not the cognizant agency, the officials told us they will only report on those findings in some cases, such as if the questioned costs exceed $5,000.

EPA officials told us the Chesapeake Bay Program has a baseline review process that involves administrative and technical checks performed once a year, and that a separate review of single audit findings is a part of this annual baseline review for all prime recipients. Specifically, the officials said that they search the FAC each year for their prime recipients and review the most recent year of audit findings for those recipients that are associated with EPA.[40]

EPA officials also told us grant officers track single audit findings for follow up. The information they track includes the prime recipient involved, the year of the audit, the nature of the finding, the date the findings were resolved, when EPA sent a management decision letter to the audited entity, and any additional comments related to the single audit findings.[41] EPA officials also said they can use single audit findings to identify prime recipients they should contact to provide additional technical assistance or training.

Agency OIGs can also conduct audits that can identify issues related to subawards. For example, DOT’s OIG issued a report that found many Operating Administrations lack detailed information on how recipients use DOT funding because the funds are passed through to subrecipients.[42] Another DOT OIG report found one agency had not complied with its own policies regarding reviews of subgrants.[43] Officials from DOE’s OIG told us they are planning to conduct audits of recipient and subrecipients of the Weatherization program that will review topics such as eligibility testing and incurred costs.

Monitoring Prime Recipients’ Oversight of First-Tier Subawards

Federal regulations require pass-through entities, including prime recipients, ensure that their subrecipients are not suspended or debarred, ensure subawards are identified as such to the subrecipient, evaluate fraud and noncompliance risk, verify subrecipients undergo required single audits, and perform appropriate subrecipient monitoring.[44]

Officials from our selected programs use a variety of approaches to monitor their prime recipients’ oversight of first-tier subawards. These activities include:

Collecting regular reports on subrecipient monitoring activities. DOE requires Weatherization prime recipients to complete an annual Training, Technical Assistance, Monitoring, and Leveraging report in which they describe their monitoring of subrecipients, including the subrecipients they monitored, any major findings from their monitoring and resolutions, and trends with respect to findings.

Checking subrecipient eligibility. DOE officials told us that when reviewing recipients’ proposed plans, they use SAM.gov to look for any issues with intended subrecipients in the plan. For example, officials told us they might find that a subrecipient holds outstanding federal debt. In those cases, officials said they would reach out to the prime recipient or the subrecipient directly and ask if they have a payment plan in place. They would then confirm that the payment plan is being followed to resolve the debt or could put a temporary hold on those subrecipients’ funding, if appropriate.[45]

Conducting site visits. DOE officials told us that each year, the Weatherization program performs a risk assessment of prime recipients and uses the results of that assessment to prioritize which site visits to conduct. During site visits, Weatherization officials use a monitoring checklist that directs officials to collect and review documents from the prime recipient that include the most recent subrecipient agreements and subrecipient monitoring reports, samples of communications with subrecipients, and subrecipient corrective action plans (if applicable). The checklist also instructs Weatherization officials to assess how a prime recipient ensures that its subrecipients have all relevant program materials needed to effectively carry out the program, what the prime recipient’s process is for executing its subrecipient awards, and how the prime recipient reviews and validates subrecipient invoices for allowable costs.

Holding regular meetings with prime recipients. DOT officials told us that they hold meetings twice a year with transportation centers participating in the UTC program that allow recipients to ask questions and learn from one another. EPA officials told us that that they meet with prime recipients to touch base after the recipients submit each of their semiannual progress reports.

Providing technical assistance to prime recipients. EPA officials told us they will often help Chesapeake Bay Program recipients with questions they raise. EPA also provides specific guidance to help prime recipients understand subawards. For example, EPA guidance documents contain an appendix with information on making the distinction between a subrecipient and a contractor.[46]

Reviewing invoices. DOT officials told us they periodically review prime recipients’ invoices to provide assurance that subrecipients are using funds appropriately. Officials stated that grants managers use a risk-based approach to select invoices to review and may consider factors such as past issues with a recipient when determining risk. In addition to selecting invoices based on risk, officials told us that they also try to review invoices from a random recipient selected from different types of UTC grant recipients.

Recent Revisions to Regulations and Guidance Could Enhance Subaward Oversight

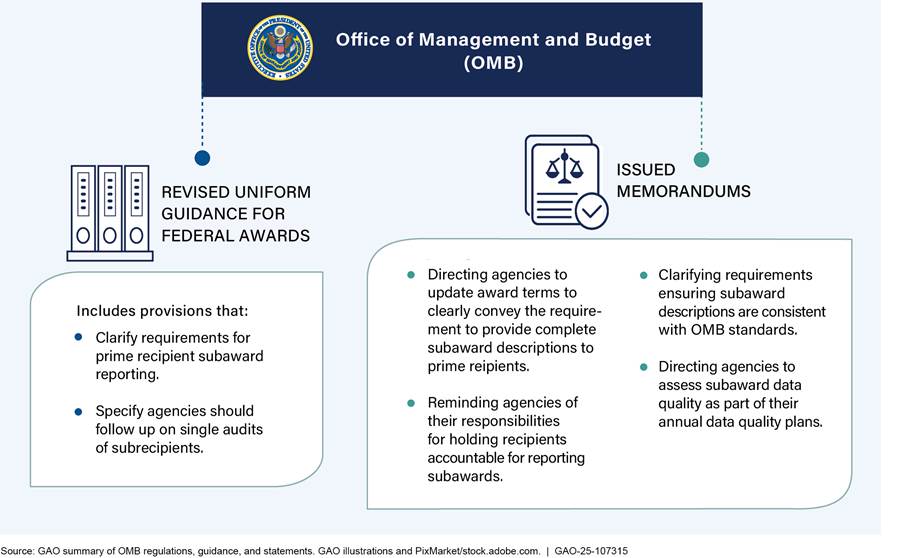

Recent revisions to OMB regulation and guidance provide direction to federal agencies on improving the management of federal financial assistance, as shown in figure 3.

Note: OMB issues uniform requirements and guidance for federal financial assistance. See 2 C.F.R. pt. 170, 200. OMB memorandums referenced are Advancing Effective Stewardship of Taxpayer Resources and Outcomes in the Implementation of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, M-22-12 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 29, 2022), and Reducing Burden in the Administration of Federal Financial Assistance, M-24-11 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 4, 2024).

These revisions could lead to improvements in the completeness and accuracy of subaward data, which may make it easier to track federal grant funds awarded to subrecipients and enhance subaward oversight. Specifically, recent revisions address:

Checking subaward data quality and completeness. In April 2022, OMB issued memorandum M-22-12, which directs federal agencies to annually review the quality of their financial assistance subaward data, including subaward descriptions, for all programs included in their DATA Act Quality Plan.[47] The guidance specifies that agencies should test a statistical sample of subaward records to ensure that award descriptions, reporting of subawards, and postaward reporting are meeting requirements and directives. The guidance also directs agencies’ officials to consider the results of that testing in their processes for producing the management assurance statement in agencies’ annual Agency Financial Reports.[48]

In November 2023, we observed issues with the quality of reported subaward data in USAspending.gov, including subawards with impossibly large amounts and likely duplicative records.[49] We also found that existing OMB guidance, such as M-22-12, did not establish clear expectations for agencies’ role in supporting subaward data quality. We recommended that OMB clarify its expectations of agencies in supporting the quality of subaward data reported to USAspending.gov via FSRS. OMB revised its regulations and issued implementing memorandum M-24-11 in April 2024 to clarify the required reporting of certain subawards and that awarding agencies are responsible for ensuring prime recipients report required subaward information to FSRS to be displayed on USAspending.gov.[50] This guidance, if implemented properly, should lead to improvements in the completeness of subaward data available to the public on USAspending.gov. For example, EPA officials told us the Chesapeake Bay Program checks prime recipients’ FSRS reporting as part of its annual review, and we did not identify any prime recipients of this program that had unreported subawards.

Conveying subaward description requirements. In its M-24-11 memorandum, OMB directed agencies to update the terms of their federal awards to clearly convey to prime recipients the requirement to provide complete subaward descriptions to further increase federal award transparency. We previously reported that award descriptions are particularly important to achieving the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act’s transparency goals and for ensuring that data are consistent and comparable, thus allowing the public and policymakers to track federal spending.[51] Subaward Description is one of the data elements included by prime recipients when reporting subaward data to USAspending.gov via FSRS. In November 2023 we reported on some issues with subaward descriptions, such as subaward descriptions having five or fewer characters, no letters, or no spaces. Improved subaward descriptions may assist in providing clear information to the public about federal spending.

Clarifying what must be reported as a subaward. Previously, OMB instructed prime recipients to report each “obligating action” to FSRS. In November 2023, we found that approximately 25 percent of grant subawards may have been duplicative of other existing subaward records on USAspending.gov, and that some prime recipients may be confused about what qualifies as an action they should report.[52] OMB amended the regulation, which became effective on October 1, 2024, to direct prime recipients to report the “total amount of the subaward” when reporting subawards to FSRS.[53] This change may help reduce duplicative reporting of subawards in USAspending.gov by clarifying what prime recipients are supposed to report.

Following up on subrecipient single audit findings. Prior to October 1, 2024, OMB directed federal awarding agencies to follow up on single audit findings to ensure the “recipient” takes timely and appropriate corrective action.[54] We have previously reported that some agencies focus on addressing and resolving single audit findings only where those findings were addressed to their prime recipients.[55] In its updated guidance, OMB now requires awarding agencies to follow up on single audit findings for “non-Federal entities.” OMB staff confirmed that this revised language is intended to include findings addressed to both prime recipients and subrecipients and clarify that agencies should be aware of all single audit findings associated with their programs.[56] The revised regulations and guidance could encourage agencies to review single audit findings made to subrecipients of their programs. This would enhance agencies’ oversight of their prime recipients’ subrecipient monitoring responsibilities.[57]

Fully implementing OMB’s revised guidance could enhance federal oversight of subawards by leading to more complete subaward reporting to the public, including improved subaward descriptions, and greater use of single audit findings to identify common compliance issues requiring agency attention. Moreover, having more complete and accurate information on where subawards are spent, by whom, and for what purpose could help detect and prevent fraud and misuse of federal grant funds. We will continue to monitor subaward oversight and transparency as agencies take steps to implement this new guidance.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to DOE, DOT, EPA, and OMB for review and comment. We received technical comments from DOT, which we incorporated as appropriate. DOE and EPA responded that they did not have any comments on our draft report. OMB did not provide comments on the draft report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretaries of Energy and Transportation, the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be made available at no charge at the GAO website at www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-6806 or arkinj@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Jeff Arkin

Director, Strategic Issues

This report describes (1) common issues related to subaward oversight identified through single audits, (2) how selected federal agencies and grant program offices implement their grant subaward oversight requirements, and (3) recent changes to regulations and guidance that could enhance subaward oversight.

To identify common subaward oversight issues, we analyzed findings made by independent auditors in recent single audits. A single audit is an audit of an entity’s financial statements and expenditures of federal awards that can identify the award recipient’s deficiencies in (1) presentation of financial information under applicable accounting standards; (2) compliance with provisions of laws, regulations, contracts, or grant agreements; or (3) its internal control systems.[58] The Single Audit Act, and implementing Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance, generally requires an annual single audit (or, in limited circumstances, permits a program-specific audit) be performed on non-federal entities that spent $1 million or more in federal award dollars in a fiscal year.[59]

The Federal Audit Clearinghouse (FAC) is a website that publishes single audits performed under the Single Audit Act.[60] Our prior work has examined the reliability of the FAC data and found them sufficiently reliable for the purposes of describing available information in single audits.[61] We performed additional testing on single audit data we used in our analyses and found that they have not changed in ways that would affect their reliability for our purposes.

To efficiently summarize the contents of thousands of single audit findings, we used a type of statistical text analytics—known as topic modeling—on the text of selected findings. Topic modeling uses machine learning to detect underlying topics, or groups of related words, within text documents.

The topic modeling work took two phases: fitting the models and applying them to updated data. In both phases, we obtained all available findings and federal award data for audit years 2022 to 2024 from the FAC. We did not limit that analysis to a specific awarding agency or agencies. To focus on findings most likely to describe challenges related to oversight of grant subrecipients, we removed findings associated with direct federal assistance loans. We also filtered down to findings addressed to either (1) a prime recipient overseeing one or more subrecipients, or (2) a subrecipient that did not pass along any portion of their funds to a further subrecipient. We determined the resulting sets of findings were most likely to relate to subrecipient oversight issues of interest to our audit.

To fit our models, we obtained our selected data as of September 28, 2024. We cleaned and processed the text of those findings to ensure they were useable for topic modeling.[62] We then extracted the condition, criteria, and cause statements from each finding, when they could be readily identified.[63] After consideration and testing of the numbers of topics appropriate to these texts, we fit two separate models for the two groups of findings. For one model, we used the texts from 3,694 findings addressed to prime recipients overseeing subrecipients. For the second model, we used the texts from 9,571 findings addressed to subrecipients that did not make further subawards. We fit each of our two topic models to these texts using a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm.[64] For each model, we assigned the number of topics that produced the most favorable values of coherence and perplexity.[65]

To succinctly refer to specific topics in other sections of this report, we assigned them names. For each named topic, we reviewed the keywords and the five findings the model deemed most representative of the topic, to develop initial names.[66] Those initial names were then independently reviewed by an internal methodological expert. The topic names used in this report are not intended to summarize all the findings that the model associated with a given topic.

In the next phase, we applied our models to our selected findings and awards data from the FAC as of January 3, 2025. We extracted only the condition statements out of the findings and applied the same filters and data cleaning steps. Ultimately, we applied our models to 3,680 condition statements from findings addressed to prime recipients overseeing one or more subrecipients and 10,509 addressed to subrecipients that did not pass along any portion of their funds to a further subrecipient. These findings collectively came from 7,352 audits and spanned over 30 grant awarding agencies.

The LDA algorithm does not assign a single topic to a single text; rather, each text can have elements of more than one topic in it at a time. However, the LDA algorithm provides the topic distribution (as values of gamma, γ) for each of the texts it models. Therefore, to quantify the prevalence of the topics within our condition statements, we considered a condition statement to be most closely associated with a given topic (its dominant topic) if that topic maximized its value of gamma (γ) according to our models. Table 1 shows the topics and their frequencies as dominant topics according to our model of 3,680 findings addressed to prime recipients overseeing subrecipients.

Table 1: Topics Generated by GAO Topic Modeling of Condition Statements from Single Audit Findings Addressed to Select Prime Recipients of Federal Grants

|

Topic |

Topic keywords |

Frequency as dominant topic in selected condition statements |

Percent frequency as dominant topic in selected condition statements |

|

1 |

subrecipient, monitoring, recipient, passthrough, risk, review, include, monitor, assessment, perform |

482 |

13.1% |

|

2 |

act, funding, transparency, accountability, system, month, tier, equal, compensation, prime |

517 |

14% |

|

3 |

fund, state, program, agency, schedule, total, fiscal, request, school, cash |

372 |

10.1% |

|

4 |

federal, control, internal, award, entity, non, maintain, effective, establish, condition |

41 |

1.1% |

|

5 |

contract, suspension, debarment, contractor, suspend, procedure, county, policy, debar, purchase |

333 |

9% |

|

6 |

eligibility, payment, service, provider, case, child, process, access, claim, income |

543 |

14.8% |

|

7 |

charge, activity, grant, support, employee, allowable, record, documentation, time, sample |

512 |

13.9% |

|

8 |

report, submit, financial, quarterly, data, end, period, information, city, project |

591 |

16.1% |

|

9 |

department, requirement, year, management, office, finding, property, equipment, level, identify |

289 |

7.9% |

Source: GAO topic modeling of selected single audit data from the Federal Audit Clearinghouse application programming interface, or API, for audit years 2022 to 2024, as of January 3, 2025. | GAO‑25‑107315

Note: When preparing text for topic modeling, each text is cleaned of punctuation and set to lowercase. Frequencies were measured as the number of condition statements modeled for which the given topic maximized gamma (γ) (i.e., the findings deemed most representative of the topic) according to our Latent Dirichlet Allocation model. Percentages calculated out of 3,680 total texts modeled, rounded to one decimal place.

Table 2 shows topics and their frequencies as dominant topics according to our model of the 10,509 findings addressed to subrecipients that did not make subawards.

Table 2: Topics Generated by GAO Topic Modeling of Condition Statements from Single Audit Findings Addressed to Select Subrecipients of Federal Grants

|

Topic |

Topic keywords |

Frequency as dominant topic in selected condition statements |

Percent frequency as dominant topic in selected condition statements |

|

1 |

contract, wage, contractor, requirement, rate, project, certified, include, subcontractor, weekly |

529 |

5% |

|

2 |

charge, employee, activity, support, time, allowable, record, indirect, allocate, effort |

1190 |

11.3% |

|

3 |

control, internal, property, corporation, issue, non, effective, equipment, sponsor, general |

695 |

6.6% |

|

4 |

report, submit, end, year, day, month, data, form, period, timely |

1329 |

12.6% |

|

5 |

financial, schedule, accounting, statement, duty, prepare, account, segregation, error, ledger |

1174 |

11.2% |

|

6 |

purchase, entity, suspension, debarment, suspend, debar, threshold, covered, method, exclude |

1056 |

10% |

|

7 |

eligibility, documentation, state, student, service, child, income, application, eligible, case |

1018 |

9.7% |

|

8 |

award, law, policy, procedure, establish, section, maintain, provide, condition, organization |

659 |

6.3% |

|

9 |

subrecipient, program, recipient, department, passthrough, funding, information, monitoring, accountability, county |

471 |

4.5% |

|

10 |

agency, food, provision, act, shall, labor, cash, net, resource, excess |

134 |

1.3% |

|

11 |

district, fund, reimbursement, school, claim, meal, request, esser, context, total |

1130 |

10.8% |

|

12 |

review, grant, system, payment, management, approval, process, prior, approve, invoice |

1124 |

10.7% |

Source: GAO topic modeling of selected single audit data available in the Federal Audit Clearinghouse application programming interface, or API, for audit years 2022 to 2024, as of January 3, 2025. | GAO‑25‑107315

Note: When preparing text for topic modeling, each text is cleaned of punctuation and set to lowercase. For example, the keyword “esser” comes from findings mentioning the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief program, after lowercasing. Frequencies were measured as the number of condition statements modeled for which the given topic maximized gamma (γ) (i.e., the findings deemed most representative of the topic) according to our Latent Dirichlet Allocation model. Percentages calculated out of 10,509 total texts modeled, rounded to one decimal place.

Using the same set of findings as of January 3, 2025, used for topic modeling, we extracted the cause statements from those findings, when they could be identified. We then searched within these cause statements for selected root cause terms based on findings we read to identify other findings having the same root causes. Specifically, we wrote our search terms using regular expressions related to the following root cause types: (1) personnel issues, such as inadequate staff and turnover; (2) lack of understanding, knowledge, or awareness of the requirements; (3) lacking evidence, such as documents, records, or tracking; (4) mistakes or errors, including miscalculations; and (5) insufficient internal controls, including lack of supervisory reviews or policies and procedures.[67] We associated a finding with one or more of these root cause types if its cause statement matched to one of our regular expressions search strings. Because we cannot perfectly account for every possible way of phrasing our root cause types, frequencies of root causes based on this analysis are very likely underestimates.

To describe how selected federal agencies and grant program offices oversee grant subawards, we selected three case study programs that received funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).[68] We selected our case study agencies and programs using data from USAspending.gov to identify agencies that received the most IIJA grant funding and programs that had reported subawards. We also consulted with agency and Office of Inspector General (OIG) officials to identify case study programs with diverse recipients to give us exposure to a broad range of perspectives, potential challenges, and oversight approaches. Ultimately, we selected the Department of Energy’s Weatherization Assistance Program for Low-Income Persons, the Department of Transportation’s University Transport Centers Program, and the Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program. The results from our selected case study programs are not generalizable to all programs, but they provide valuable insight into the approaches some agencies take to implement their subaward oversight responsibilities.

To describe our selected agencies’ subaward oversight activities, we interviewed knowledgeable officials from our selected agencies and program offices. We asked them about steps and actions they take to ensure prime recipients fulfill their responsibilities for subrecipient oversight. We also discussed actions they take, if any, to oversee subrecipients directly.

We reviewed selected agencies’ program and agency-level documentation including internal policies or guidance related to grant and subaward management. We also reviewed examples of notices of funding opportunities, grant applications, grant agreements, progress reports, and other relevant records. We discussed subaward oversight with each of our selected agencies’ OIGs.

To describe recent revisions to regulations and guidance that could enhance subaward oversight, we reviewed relevant federal laws, regulations, and guidance, including OMB’s final rule issued in April 2024, which took effect in October 2024.[69] We discussed requirements in regulations and memorandums with OMB staff to confirm our understanding of their purposes.

To identify subaward reporting issues in support of our third objective, we compared subaward information available on USAspending.gov for our three selected programs as of November 1, 2024, to information we obtained from agency records from recent grant years. We looked for potential reporting anomalies including duplicated subawards, missing subawards, subaward amounts exceeding the prime award amount, and examples of award and subaward descriptions that were not consistent with established standards for reporting this information.[70] We discussed our observations with knowledgeable program officials. We also obtained information on recent single audit findings linked to our selected programs and discussed them with knowledgeable agency officials to understand their approaches for resolving relevant findings.

To address all three of our objectives, we reviewed our prior reports, as well as reports from the Congressional Research Service, agency OIGs, Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, and single audits.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to March 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

|

Source |

Requirements |

|

2 C.F.R. pt. 170 app. A(I)(a)(1)-(2) |

Recipients must report each subaward that equals or exceeds $30,000 in federal funds to the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006 Subaward Reporting System (FSRS) by no later than the end of the month after the month in which the subaward was made (unless otherwise exempt). |

|

2 C.F.R. pt. 170 app. A(I)(b) |

If a subrecipient received at least 80 percent of its annual gross revenue from federal awards subject to the Transparency Act (including contracts and financial assistance) and had at least $25 million in annual gross revenue from federal awards, and if the public does not have access to information about the compensation of the subrecipient’s senior executives through periodic reports, the pass-through entity must report information on the subrecipient’s five most highly compensated executive officials if the total award is at least $30,000. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.215, 200.216 |

Awarding agencies and recipients are prohibited from contracting with prohibited or excluded persons or entities. This restriction applies to grants and cooperative agreements exceeding $50,000, are performed outside the United States, and are in support of a contingency operation in which members of the Armed Forces are actively engaged in hostilities. Recipients and subrecipients are prohibited from using grant funds to obtain prohibited telecommunications equipment or services. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.308(f) |

As applied to subawards, the recipient or subrecipient must request prior written approval from the awarding agency or pass-through entity for programmatic or budget changes, including change in scope and subaward activities not proposed and approved for the award. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.325(a) |

As requested by the awarding agency or pass-through entity, the subrecipient must make available for review the technical specifications of proposed procurements to ensure that the item or service specified is the one being proposed for acquisition. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.329 |

The recipient or subrecipient is responsible for the oversight of the federal award. The recipient or subrecipient must monitor its activities under federal awards to ensure they are compliant with all requirements and meeting performance expectations. Monitoring by the recipient or subrecipient must cover each program, function, or activity. Generally, the recipient or subrecipient should submit performance reports at least annually but no more than quarterly. Annual reports submitted by the recipient or subrecipient are due no later than 90 days after the reporting period. When reporting program performance, the recipient or subrecipient should relate financial data and project or program accomplishments to the performance goals and objectives of the federal award, as applicable. The federal agency or pass-through entity may conduct in-person or virtual site visits, as warranted. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(a) |

The pass-through entity must confirm in SAM.gov that a potential subrecipient is not suspended, debarred, or otherwise excluded from receiving federal funds. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(b)(1) |

At the time of award, pass-through entities must ensure that every subaward is clearly identified to the subrecipient as a subaward, and that this identification includes specific information describing the award and subaward. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(b)(2), (3), (6) |

At the time of award, pass-through entities must specify to the subrecipient all legal and other requirements imposed on the award recipients, as well as the terms and conditions for closeout of the subaward. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(b)(4)(i) |

Pass-through entities must ensure that subawards include an approved, federally recognized indirect cost rate. If no rate has been negotiated between the subrecipient and the federal government, the pass-through entity must determine the appropriate rate, in collaboration with the subrecipient. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(b)(5) |

Pass-through entities must ensure subawards include a requirement for the subrecipient to allow the pass-through entity and other auditors to have access to the necessary records and financial statements needed to fulfill monitoring requirements. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(c) |

Pass-through entities must evaluate each subrecipient’s risk of fraud, and noncompliance with federal statutes, regulations, and the terms and conditions of the subaward for purposes of determining the appropriate subrecipient monitoring. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(d) |

Pass-through entities must consider whether it is appropriate to impose specific conditions upon the subrecipient based on potential risks and history of compliance, and they must inform the federal awarding agency of any such conditions imposed. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(e) |

Pass-through entities must monitor the activities of a subrecipient to ensure that the subrecipient complies with federal statutes, regulations, and the terms and conditions of the subaward. The pass-through entity is responsible for monitoring the overall performance of a subrecipient to ensure that the goals and objectives of the subaward are achieved. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(e)(1) |

Pass-through entities must review required financial and performance reports from the subrecipient. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(e)(2) |

Pass-through entities must follow up to ensure subrecipients take corrective action to address any significant developments that negatively affect the subaward. Significant developments include Single Audit findings related to the subaward, other audit findings, site visits, and written notifications from a subrecipient of adverse conditions which will affect their ability to meet the milestones or the objectives of a subaward. Subrecipients must provide the pass-through entity information about the corrective action to be taken and any assistance needed for resolution. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(e)(4) |

Pass-through entities must resolve audit findings related to their subawards. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(g), 200.501 |

Pass-through entities must verify that every subrecipient undergoes the required single audit (or, in limited circumstances, a program-specific audit) performed by an independent auditor if the subrecipient’s federal award expenditure was $1 million or more in the subrecipient’s fiscal year (for federal awards issued prior to October 1, 2024, this expenditure threshold for single audits was $750,000 rather than $1 million). |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(h) |

Pass-through entities must consider whether subrecipient audit results, onsite reviews, or findings from other monitoring efforts necessitate adjusting their records. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.332(i), 200.505 |

Pass-through entities must consider taking enforcement actions when subrecipient noncompliance is identified. If a subrecipient is unable or unwilling to take part in a required audit, the pass-through entity must take appropriate action. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.333 |

With written approval from the federal agency, pass-through entities may provide subawards based on fixed amounts up to $500,000. These awards are subject to other requirements. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.344(a) |

If a subrecipient fails to complete close out requirements, pass-through entities must proceed to close out the federal award with the information available. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.501(i) |

For subawards to for-profit organizations, as necessary, the pass-through entity is responsible for establishing requirements to ensure compliance by the for-profit subrecipient. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.521(c), (d) |

Pass-through entities must issue management decisions within 6 months of the Federal Audit Clearinghouse’s (FAC) acceptance of the audit report for audit findings about federal awards it issues to a subrecipient. Similarly, federal awarding agencies must issue management decisions within 6 months of the FAC’s acceptance of the audit report. |

|

OMB M-24-11 pt. III |

The prime recipient is responsible for reporting quality subaward data to FSRS that is subsequently displayed on USAspending.gov for subawards they make. |

|

OMB M-24-11 pt. III |

Federal award and subaward descriptions should include award-specific activities and avoid acronyms or federal or agency-specific terminology. |

Source: GAO summary of selected regulations and guidance. | GAO‑25‑107315

Note: Pass-through entity is a recipient or subrecipient that provides a subaward to a subrecipient (including lower tier subrecipients) to carry out part of a federal program. 2 C.F.R. 200.1.

|

Source |

Requirements |

|

2 C.F.R. 170.200(b) |

Awarding agencies should ensure that agency-specific requirements do not result in duplicative subaward data reporting. |

|

2 C.F.R. 170.220 |

Awarding agencies should include subaward reporting requirements in the award terms for each grant award for which the total is anticipated to equal or exceed $30,000. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.308(f) |

As applied to subawards, the awarding agency must review requests from the prime recipient for programmatic or budget changes, including change in scope and subaward activities not proposed and approved for the award. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.329(b), (c) |

The federal agency must use Office of Management and Budget (OMB)-approved common information collections when requesting performance reporting information. The federal agency or pass-through entity may not collect performance reports more frequently than quarterly unless specific conditions have been implemented in accordance with OMB regulations. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.331 |

The federal agency does not have a direct legal relationship with subrecipients or contractors of any tier; however, the federal agency is responsible for monitoring the pass-through entity’s oversight of first-tier subrecipients. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.339 |

Awarding agencies may impose additional conditions or take additional actions as appropriate if award recipients fail to comply with the U.S. Constitution, federal statutes, regulations, or the terms and conditions of a federal grant. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.513(a) |

Non-federal entities receiving a Single Audit must have assigned an agency to provide technical audit advice and assistance to them and their auditor, among other responsibilities. If the non-federal entity expends $50 million or more of federal awards in a year, then this agency is called a cognizant agency for audit and also has a role in coordinating management decisions responding to cross-cutting findings, which are defined as findings that affect all federal grants received by the auditee.a |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.513(c)(3) |

Awarding agencies should follow up on audit findings to ensure that non-federal entities take appropriate and timely corrective action. Follow-up activities include issuing a management decision for audit findings affecting awards the federal agency makes within 6 months, as required in 200.521, and monitoring the non-federal entity’s progress implementing corrective action. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.513(c)(3)(iv) |

Awarding agencies are required to develop metrics and baselines to track the effectiveness of their process for following up on audit findings and Single Audits’ effectiveness in improving non-federal entity accountability. |

|

OMB M-22-12, pt. II |

Agencies should implement processes to support quality subaward data and should ensure that their recipients are compliant with reporting requirements. |

|

OMB M-22-12, pt. II |

Agencies should annually review the quality of their subaward data for all programs in their DATA Act Data Quality plans required by Appendix A to A-123. The reviews should include statistical sample testing. |

|

OMB M-24-11, pt. III |

The prime recipient is responsible for reporting quality subaward data to FSRS that is subsequently displayed on USAspending.gov. Federal agencies, in turn, are responsible for holding prime recipients accountable for this reporting taking place. Federal agencies also have a role in ensuring prime recipients understand the reporting requirements and assisting to resolve subaward reporting challenges. Agencies can do this in a variety of ways, including checking USASpending.gov to verify that subaward reporting is taking place as outlined in the federal award term. |

|

OMB M-24-11, pt. III |

Federal award and subaward descriptions should include award-specific activities and avoid acronyms or federal or agency-specific terminology. Agencies should update their federal award terms to clearly convey to prime recipients this requirement to provide complete subaward descriptions to further increase federal award transparency. |

|

2 C.F.R. 200.512, OMB M-24-11, pt. III |

Cognizant agencies or oversight agencies for audit may authorize an extension on the time frame for Single Audit report submission (in most cases, 30 calendar days after the auditee receives the auditor’s report or 9 months after the audit period) by non-federal entities, when complying with the mandatory time frame would be unduly burdensome.a |

Source: GAO summary of selected regulations and guidance. | GAO‑25‑107315

aCognizant agencies for audit may also be assigned by OMB. A federal agency with oversight for an auditee may reassign oversight to another federal agency that agrees to be the oversight agency for audit. 2 C.F.R. 200.513(b).

GAO Contact

Jeff Arkin, (202) 512-6806 or arkinj@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Kathleen M. Drennan (Assistant Director), Samuel A. Gaffigan (Analyst-in-Charge), Michelle B. Bacon, Virginia A. Chanley, Jaqueline Chapin, Ann Czapiewski, and Crystal Wesco made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]A subaward is an award provided by a pass-through entity to a subrecipient to carry out part of a federal award received by the prime recipient or “pass-through” entity. 2 C.F.R. § 200.1.

[2]GAO, Federal Spending Transparency: Opportunities Exist to Improve COVID-19 and Other Grant Subaward Data on USAspending.gov, GAO‑24‑106237 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 16, 2024).

[3]A single audit finding is a deficiency that the auditor is required to report in the schedule of findings and questioned costs under 2 C.F.R. § 200.516. Non-federal entities that expend $1 million or more in federal awards in their fiscal year are generally required to undergo a single audit (an audit of a non-federal entity’s financial statements and federal awards) performed by an independent auditor and conducted pursuant to generally accepted government auditing standards, as set out in OMB’s implementing single audit guidance. 2 C.F.R. § 200.501. See generally, 2 C.F.R. pt. 200, subpart F. During our audit period, the applicable annual expenditure threshold was $750,000. See 2 C.F.R. § 200.501 (2023). A single audit can help identify the federal award recipient’s deficiencies in (1) compliance with the provisions of federal statutes, regulations, and awards that may have a direct and material effect on each major grant program; (2) internal controls pertaining to compliance requirements for each major grant program; and (3) the presentation of information on its financial statements and schedule of expenditures of federal awards under applicable accounting standards. See 31 U.S.C. § 7502(e), 2 C.F.R. § 200.514.

[4]We did not limit our single audit analysis to a specific awarding agency or agencies.

[5]Pub. L. No. 117-58 (2021).

[6]Subrecipients are also able to pass funding on to another entity to carry out or assist with part of the work, which would result in a subaward beyond the first tier (second tier, third tier, etc., as appropriate).

[7]2 C.F.R. §§ 200.331-332. A pass-through entity is a recipient or subrecipient that provides a subaward to a subrecipient (including lower tier subrecipients) to carry out part of a federal program. 2 C.F.R. § 200.1.

[8]Pass-through entity means a recipient or subrecipient that provides a subaward to a subrecipient (including lower tier subrecipients) to carry out part of a federal program. The authority of the pass-through entity under this part comes from the subaward agreement between the pass-through entity and subrecipient.

[9]FSRS is the system into which prime recipients report subaward information. The General Services Administration (GSA) announced that as of March 8th, 2025, it has retired FSRS.gov and transferred its subaward reporting functions to SAM.gov. Throughout this report, FSRS refers to the subaward reporting system housed at FSRS.gov or SAM.gov, as appropriate.

[10]See appendix II for a summary of selected prime recipient subaward oversight requirements laid out in federal regulations and guidance.

[11]2 C.F.R. § 200.339 details remedies for noncompliance, as appropriate. These remedies include temporarily withholding payments until an award recipient or subrecipient takes corrective action, disallowing costs for all or part of the activity associated with the noncompliance of the recipient or subrecipient, or suspending or terminating the federal award in part or in its entirety.

[12]Agencies are required to measure a recipient’s performance and communicate how the recipient must submit performance reports on achievement of the program’s goals and objectives. 2 C.F.R. §§ 200.301, 200.329(c). Throughout this report, we refer to the recipient’s performance reports as progress reports.

[13]See appendix II for a summary of selected agency oversight requirements laid out in federal regulation and guidance.

[14]Topic modeling uses machine learning to detect underlying topics, or groups of related words, within text documents. See appendix I for detailed information about our topic modeling.

[15]To succinctly refer to the topics generated by our topic models in this report, we have assigned shortened names to the ones we will discuss based on the keywords identified by our models and our subjective review of the findings deemed most representative of those topics, according to our models. These names do not summarize all the keywords identified by our model as associated with the topic, nor do all findings associated with that topic relate specifically to the concept captured by our topic name. FFATA reporting is the name we assigned to topic number 2 in appendix I table 1. “FFATA” refers to the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-282, 120 Stat. 1186, which is reprinted as amended at 31 U.S.C. § 6101 note.

[16]Florida Department of Financial Services, Florida Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2023 (Tallahassee, Fl.: Feb. 28, 2024).

[17]We performed this analysis by using a searching methodology on words and phrases related to certain root causes we identified (see appendix I for more information). Findings in our analysis may have more than one root cause type. In addition, because we cannot perfectly account for every possible phrasing, frequencies of root causes based on this analysis may be underestimates.

[18]Subrecipient monitoring activities refers to topic number 1 in appendix I table 1.

[19]Verifying or justifying eligibility decisions is the name we assigned to topic number 5 in appendix I table 1. This topic also included findings about decisions to limit competition for procurements or contracts made with federal grant funds, and how those decisions were justified or documented.

[20]SAM.gov is the System for Award Management administered by GSA.

[21]Agencies reported the first-year IIJA funds are available for obligation spans fiscal year 2022 to fiscal year 2026.

[22]Energy’s Weatherization Assistance Program for Low-Income Persons is intended to increase the energy efficiency of dwellings owned or occupied by low-income persons, reduce their total residential energy expenditures, and improve their health and safety, especially low-income persons who are particularly vulnerable. DOE awards prime grants to states and territories. The states and territories then make subawards to non-profit community action agencies or other public or non-profit entities that use the funds locally.

[23]DOT’s UTC program awards grants to non-profit institutions of higher education to establish and operate centers that are intended to advance transportation research and technology and develop the next generation of transportation professionals. These centers are made up of a lead institution, which is the prime recipient of the grant, and consortium members, which are institutions of higher education that receive funding via subawards from the lead institution.