MODERNIZING THE NUCLEAR SECURITY ENTERPRISE

Opportunities Exist to Better Prepare for Delay in New Uranium Processing Facility

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-25-107330, a report to congressional committees

For more information, contact: Allison Bawden at bawdena@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

In 2004, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) began plans to replace buildings at its Y-12 in Oak Ridge, Tennessee to support processing uranium for nuclear weapons and naval reactor fuel. NNSA expects the new Uranium Processing Facility to be fully operational in 2034. Until then, NNSA will continue using Building 9212, which was built in 1945 and predates modern safety codes.

GAO Key Takeaways

NNSA received approval to re-baseline its Uranium Processing Facility project in December 2024 at a cost estimate of $10.35 billion—adding nearly $4 billion and an 8-year delay to reach full operations.

In January 2023, NNSA identified root causes and factors contributing to the cost increases and schedule delays. For example, NNSA found poor contractor performance, late notice of cost overruns, and limited workforce availability.

NNSA’s contractor estimates that it will costs about $463 million to safely continue operations in Building 9212 until 2035—about a year after the new facility is expected to be fully operational. Some NNSA officials acknowledged increasing risks of continuing to rely on this building, which has degrading infrastructure and does not meet modern nuclear safety codes for earthquakes or high-wind events.

NNSA has a comprehensive plan to continue safe operations in other aging buildings that were originally planned for replacement by the new facility but were scoped out of the project in 2012. In contrast, NNSA does not have a comprehensive plan to safely operate Building 9212 to accommodate the new facility’s delay. A plan would provide consistent information to better manage tradeoffs and address risks to continued safe operations in Building 9212.

How GAO Did This Study

We reviewed NNSA’s 2023 root cause analyses related to project cost and schedule overruns. We analyzed information on the impact of the project delay on NNSA’s mission. We conducted a site visit to the Y-12 National Security Complex to observe construction of the new facility and conditions at existing buildings.

What GAO Recommends

We recommend that NNSA establish a comprehensive plan to maintain safe operations in Building 9212 until 2035 or operations are ceased. NNSA concurred and has begun to take action to address our recommendation.

Abbreviations

APMO Acquisition and Project Management Office

DOE Department of Energy

EVMS earned value management system

HVAC heating, ventilation, and air conditioning

M&O management and operating contractor

NNSA National Nuclear Security Administration

DOE-PM Office of Project Management

UPF Uranium Processing Facility

(Y-12) Y-12 National Security Complex

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 18, 2025

Congressional Committees:

The National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) project is nearly $4 billion over cost and 8 years behind schedule to reach full operations. It is under construction at the Y-12 National Security Complex (Y-12) located in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. When the project is complete, NNSA expects the UPF to replace Building 9212, an 80-year-old uranium processing building central to the production of certain nuclear weapons components and fuel stock to the Navy. In March 2018, the project was estimated to cost $6.5 billion and was to be fully operational by 2026.

In December 2024, NNSA received approval from the Department of Energy (DOE) to re-baseline, or reset, the project’s estimated cost and schedule, at a cost of $10.35 billion and project completion in January 2032, with full operations to begin 2034.[1] This re-baseline reflects the challenges NNSA and its contractor have had over 2 decades in managing the scope, cost, and schedule of the UPF project.[2] We previously found ongoing issues in NNSA’s contract and project management, including in its modernization of uranium processing capabilities. Because of these and other issues, we have long designated program and project management as high risk for waste, fraud, abuse, and mismanagement.[3]

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 and the Senate and House committee reports accompanying bills for energy and water development appropriations for fiscal year 2024 include provisions for GAO to assess the UPF project.[4] This report examines the extent to which (1) NNSA implemented UPF project corrective actions to address the root causes identified for the project’s cost increase and schedule delay and (2) NNSA has identified and taken action to mitigate any impact of the delay in the UPF full operations.

To determine the extent to which NNSA implemented corrective actions to address cost increases and schedule delays for the UPF project, we interviewed officials from the UPF federal project team and analyzed NNSA’s January 2023 and updated March 2024 root cause analysis reports.[5] We reviewed documentation on the implementation of the corrective actions NNSA proposed to address these root causes. We interviewed officials and reviewed documents from DOE’s Office of Project Management (DOE-PM), including external independent reviews of proposed revisions to the UPF project’s cost and schedule estimates and the UPF project contractor’s implementation of its earned value management system (EVMS).

We compared the corrective action implementation and oversight activities of NNSA and DOE-PM officials to relevant project management requirements in DOE Order 413.3B, Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets, and department guidance.[6] In addition, we analyzed the revised UPF project documentation that accompanied the proposed project cost and schedule re-baseline, which was ultimately approved in December 2024. We interviewed UPF federal project officials about the root cause analyses, DOE-PM officials about the proposed revisions, and UPF federal officials and contractor representatives about the risks and uncertainties they identified to successfully complete UPF construction and startup activities.

To determine the extent to which NNSA has identified and taken action to mitigate any impact of the delay in UPF full operations, we analyzed information from NNSA’s uranium customers, programs, facility planning documents, reprogramming, and maintenance and repair and operations budget data. To assess the reliability of the contractor’s maintenance and repair cost estimates, we collected information from the management and operating (M&O) contractor about the process used to develop the estimate and assess the reliability of the estimate. The M&O contractor used prior year cost estimate and other data collected on the maintenance repair needs of Building 9212 during the year to support its estimate. We analyzed the cost estimates to maintain Building 9212 from the Y-12 M&O contractor. The cost estimate data is reliable for our purposes of describing the cost to maintain and repair Building 9212 until the building is expected to cease operations.

We interviewed NNSA officials and contractor representatives from the following offices on how data on Building 9212 and uranium processing support facilities informs and supports funding and tradeoff decisions to address risks to achieve NNSA’s mission:

· Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation (NA-20)

· Defense Programs (NA-10)

· Naval Reactors (NA-30)

· Office of Infrastructure (NA-90)

We compared plans to continue operations in uranium processing and support facilities to nuclear industry practices on planning for use of aging facilities. We conducted site visits to Y-12 in Oak Ridge, Tennessee in June and July of 2024 to observe the status of UPF construction and of the condition of existing facilities. We analyzed Building 9212 maintenance and repair budgets and estimates for fiscal years 2018–2035. We reviewed the Y-12 Field Office’s safety activities and the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board’s review of material hazards in existing uranium processing facilities to determine how Y-12 is reducing safety risks. We interviewed NNSA officials with the Y-12 Field Office, the M&O contractor representatives, and the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board on efforts to improve safety of uranium processing in Y-12’s existing facilities.[7]

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Performance Baseline Metrics in DOE Order 413.3B

DOE Order 413.3B, Program and Project Management for the Acquisition of Capital Assets, governs NNSA’s management of all capital asset projects with an estimated cost of $50 million or more.[8] The goal of the order is to support project management in delivering projects within their original cost and schedule baselines and be fully capable of meeting mission performance and other requirements.[9] A project’s performance baseline metrics include

1. the estimated total project cost, consisting of design, procurement, and construction costs. It also includes management reserve, which is the total of the costs included for risks for which the contractor is responsible, and contingency to cover cost risks related to factors outside of the contractor’s control;

2. an estimate for the date of completion, which represents when construction activities are planned to be complete for the project’s transition to operations; as well as contractor schedule reserve for the time to address risks of delay in completing project tasks; and

3. scope, including key performance parameters that define essential characteristics, functions, or requirements associated with the completed facility or capability.

As part of the development of a project’s performance baseline, the agency is required to conduct an analysis of the risks that might result in cost increases and schedule delays and develops mitigation strategies to lessen or eliminate these risks. Contingency cost and schedule are included in the performance baseline in case risks that are out of the contractor’s control—such as changes to regulations or funding below expected levels—are realized. Management reserve should be included to cover risks for which the contractor is responsible, such as unanticipated effort resulting from accidents, errors, technical redirections, or contractor-initiated studies, and cannot be used to offset or minimize existing cost variances.

Process for Changing a Project’s Performance Baseline in DOE Order 413.3B

DOE Order 413.3B requires the federal project director to promptly notify management when it becomes apparent that a project’s performance baseline cost, schedule, or scope go beyond the approved threshold. When this occurs, the project management executive must make a specific determination whether to terminate the project or establish a new performance baseline by requesting the federal project director to submit a baseline change proposal.[10] For the UPF project, the executive approval authority is the Deputy Secretary of Energy.

In addition, the program office responsible for the project is to conduct an independent and objective root cause analysis to determine the underlying contributing causes of cost overruns, schedule delays, or performance shortcomings.[11] The program office is also required to develop a formal corrective action plan to address the identified root causes for not meeting the approved baselines. The root cause analysis and corrective action plan are submitted to the Deputy Secretary of Energy to inform the decision on the baseline change proposal.[12] The Deputy Secretary reviews and formally approves the updated project performance baseline for projects where the increase in cost is more than $100 million or 50 percent of the original cost baseline, which DOE refers to as “re-baselining.”

In addition, for projects with a total project cost of $100 million or greater, DOE-PM conducts an external independent review or an independent cost review (or both) to validate a project’s proposed performance baseline change. The order requires DOE-PM to assess and validate, as appropriate, the extent and effectiveness of corrective actions that have been taken to address and resolve the identified root causes. Following approval of a project’s re-baseline, the order also requires DOE-PM, as a review team participant or observer, when necessary and as appropriate, to independently assess the effectiveness of the corrective actions taken to address and resolve the identified root causes.

Earned Value Management Requirements in DOE Order 413.3B

Earned value management is a widely accepted best practice used to plan for, manage, and assess the cost and schedule performance of capital asset projects, among other program and project activities. Data from the earned value management system (EVMS) can provide an early warning of problems that could negatively affect a project’s performance.[13] DOE Order 413.3B generally requires all projects with a total project cost of over $50 million to develop and implement an EVMS upon approval of the project’s performance baseline, except for those with a firm fixed-price contract.[14] In addition, for projects with a total project cost of $100 million or greater, DOE-PM is required to certify whether the contractor’s EVMS is in compliance with the national industry standard.[15] DOE-PM is responsible for conducting risk-based, data-driven surveillance reviews during the tenure of the contract, during contract extensions, or as requested by the federal project director, to ensure the certified EVMS remains compliant with some or all of the industry standard.

NNSA Stakeholders for UPF Enriched Uranium Operations

Multiple offices within NNSA have a role in implementing or will be reliant upon the UPF project:

· The Office of Infrastructure (NA-90) carries out maintenance and infrastructure investment, among other activities, in existing buildings at Y-12.

· Within this office, the Y-12 Acquisition and Project Management Office (APMO) provides onsite project and contract requirement oversight for all capital projects at the Y-12 complex and is the primary federal office responsible for oversight of the UPF project.

· The Office of Defense Programs (NA-10) partners with the Department of Defense to provide safe, secure, and reliable nuclear weapons through modernization programs and stockpile and production management. Within Defense Programs

· the Enriched Uranium Modernization Program oversees the development of new technology for the UPF and in existing uranium facilities;

· the Office of Stockpile Management sets requirements for the enriched uranium needed to serve the stockpile programs, among other activities, currently carried out in Building 9212 and ultimately in UPF.

· The Y-12 Field Office is responsible for ensuring safe, secure, and cost-effective operations at Y-12, to include existing uranium processing facilities.

· The Office of Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation (NA-20) provides policy and technical leadership to limit or prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction, to advance the detection of weapons of mass destruction, and eliminate or secure surplus materials and infrastructure usable for nuclear weapons.

· The Office of Reactor Conversion and Uranium Supply is reliant on the existing uranium processing facilities at Y-12 and UPF in the future. The office oversees the downblending of highly enriched uranium stock to support commercial and research activities, including the production of life-saving medical isotopes, while eliminating the need for weapons-usable materials in civilian applications.

· The Office of Naval Reactors (NA-30) program is reliant on the existing uranium processing facilities at Y-12, and UPF in the future, to provide the U.S. Navy with the nuclear fuel it needs for effective nuclear propulsion.

History of the Uranium Processing Facility Project

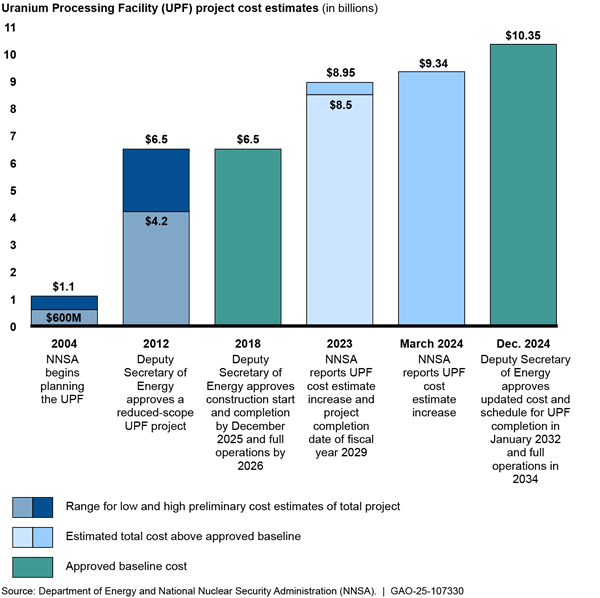

NNSA and its contractors have struggled for years to establish a credible baseline—project scope, cost, and schedule—for the UPF project.[16] Even though the project’s original scope has been much reduced, its cost has grown substantially as shown in figure 1, and schedule delays are resulting in Y-12 and NNSA relying for longer on facilities that are now 70-83 years old.

In 2004, NNSA began planning the UPF project to replace four uranium processing and support buildings at Y-12, including buildings 9212, 9204-2E, 9215, and 9995. The facility was expected to

· consist of a single, consolidated uranium processing and component production facility less than half the size of Y-12’s existing enriched uranium facilities,

· reduce the costs of enriched uranium processing by using modern processing equipment and consolidated operations, and,

· use new technologies and other features.

In addition, the building and new technology—preliminarily estimated to cost $1.1 billion—were expected to provide better worker protection and environmental health and safety than the existing buildings.

|

Building 9212 Decommissioning As of May 2025, National Nuclear Security Administration estimates operations will cease in Building 9212 in fiscal year 2035 and the building will be ready to be turned over to the Department of Energy’s Office of Environmental Management for decontamination and decommissioning activities in 2038.

Sources: Consolidated Nuclear Security, LLC. (photo). | GAO‑25‑107330 |

In 2007, NNSA updated the project’s preliminary cost estimate range to $1.4 billion to $3.5 billion, accounting for increased labor costs and contingency funds to address external project risks, among other factors. In 2010, NNSA refined its preliminary project cost estimate range to $4.2 billion to $6.5 billion. By June 2012, NNSA deferred portions of the original scope of the project and invested in mission, safety, and security risk reduction in Building 9212. The Deputy Secretary of Energy approved the updated preliminary cost range of $4.2 billion to $6.5 billion and scope deferment of the project.

According to NNSA project plans, the scope deferral was in response to a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers project cost estimate challenging NNSA’s 2010 estimate. To implement the deferment of the UPF project scope, NNSA made a tradeoff decision to continue laboratory operations in Building 9995 (built in 1951), weapon components assembly and disassembly in Building 9204-2E (built in 1969), and metal machining operations in Building 9215 (built in 1956) for at least 20 more years, rather than move those capabilities into the UPF.

The following describes the facilities and actions taken to extend safe operations in existing uranium processing and support facilities after portions of the UPF project were deferred.

· Building 9204-2E, built in 1969 and predating modern nuclear safety codes, includes capabilities for assembly, disassembly, dismantlement, inspection, and surveillance of enriched uranium components with other materials. In response to the UPF project deferment, NNSA established an extended life program plan in 2016 to continue safe, reliable operations in Building 9204-2E until replacement facilities are operational, expected in the 2040s at the earliest, according to the plan. Overall, NNSA has invested millions a year to maintain Building 9204-2E and other buildings as part of its plan to continue operations after the deferment of elements of the UPF project. For example, in Building 9204-2E, NNSA is maintaining single-point-of-failure equipment, such as gloveboxes and processing equipment, to support an aggressive production schedule, in part due to the delay in the UPF project.

· The 9215 Complex, specifically Building 9215, built in 1956, predates modern nuclear safety codes. NNSA conducts fabrication operations, or metal machining of its enriched uranium and product inspection. Additional responsibilities were added to conduct uranium purification and process uranium metal scraps from its machining operation when the UPF project was rescoped and elements of the project were deferred. NNSA established an extended life program plan in 2016, to include infrastructure investments, to continue safe, reliable operations to 2040.

· Building 9995, built in 1951 with a major addition completed in 1968, predates modern nuclear safety codes and houses analytical chemistry operations, to include assessing enriched uranium samples to support production. NNSA established an extended life program plan for continued safe, reliable operations into the 2040s. Overall, NNSA has invested millions a year to maintain this and other buildings with plans to extend operations. According to program officials and Y-12 representatives, a new facility was planned for completion in 2032; however, the project has not begun and is expected to be delayed several years.

In addition, in response to the project deferment, NNSA officials established a plan to reduce mission, safety, and security risk for Building 9212, among other objectives, to keep it safely operating until 2026. According to NNSA plans, by deferring other portions of the project, NNSA could use those funds to accelerate the transition of Building 9212 capabilities into UPF—the highest priority elements of the project.

· Building 9212 was built in 1945, predating modern nuclear safety codes, and houses uranium operations. It consists of interconnected buildings containing capabilities for uranium purification and casting, among other things. Since 2012, after other portions of the UPF project were deferred, NNSA developed and continues to implement a building risk reduction plan. With the project scope deferment, NNSA expected to support closure of Building 9212 sooner. However, NNSA officials realized the agency would need to invest in the building to address facility risks. Since 2014, NNSA invested about $78 million in Building 9212 infrastructure and utilities to support continued operations in the facility until 2026, the date of UPF full operations.

By August 2012, just 2 months after deferring laboratory, assembly, and machining capabilities out of the UPF project scope, NNSA determined that due to the project contractor’s mismanagement of its subcontractors’ work products, equipment planned for UPF would not fit in the building. NNSA estimated the project would require an additional $540 million to raise the roof of the UPF facility. Between 2013 and 2016, the project contractor began site preparation and electrical work.

In October 2014, NNSA defined the minimum and desired performance, scope of work, cost, and schedule program requirements for UPF operations.[17] In 2014, the NNSA Acting Administrator stated that NNSA did not plan to continue operations in Building 9212 past 2025. Moreover, increasing equipment failure rates presented challenges to meeting required production targets, in a building that predates modern nuclear safety codes.

By March 2018, the NNSA contractor had completed the site preparation work and infrastructure and services subproject for the UPF, below the combined total cost estimated for these activities.[18] In addition, the Deputy Secretary of Energy approved the scope of work, cost, and schedule baseline estimates for UPF project construction at a cost of $6.5 billion to be completed by December 2025 and fully operational by 2026. NNSA’s project contractor completed the electrical power substation below the estimated cost in December 2019.

From April 2019 to February 2022, project performance reporting indicated the cost and schedule generally exceeded estimates for about 21 and 29 of the 35 months, respectively.[19] In preparation to submit a change to the project’s performance baseline, in July 2022, the contractor developed an updated cost and schedule estimate for the overall project and completed construction of the mechanical electrical support building portion of the project.

NNSA continued to revise cost and schedule estimates for the UPF project. In March 2023, NNSA estimated the project completion at a cost of $8.5 billion to $8.95 billion by the first half of fiscal year 2029. In addition, in 2023 NNSA reprogrammed about $200 million in funding from other projects and programs to support UPF. In March 2024, NNSA included an expected UPF cost estimate of $9.34 billion for the nuclear security program estimated budget for fiscal years 2026-2029. By May 2024, the federal project office revised its project estimate at a cost of $10.3 billion to be completion by October 2031.

In December 2024, the Deputy Secretary of Energy approved NNSA’s re-baseline of cost and schedule estimates for completion of the UPF project at an estimated cost of $10.35 billion with project completion in January 2032. This re-baseline reflects the scope committed to in June 2012.

NNSA Has Implemented Corrective Actions to Address UPF Cost Increases and Schedule Delays, but Risks Remain

Between 2023 and 2024, NNSA and DOE-PM conducted multiple reviews that identified four primary root causes and 14 primary factors that led to UPF cost increases and schedule delays. In coordination with DOE-PM, NNSA developed a plan that included 20 corrective actions to address the root causes and other factors. As of July 2025, NNSA had implemented 19 corrective actions. However, in DOE-PM’s independent reviews, it identified significant areas of concern with the UPF project’s EVMS implementation that will require additional monitoring and review. These and other issues raise risks and uncertainties about NNSA and its contractor successfully completing the project and starting UPF operations within the cost and schedule re-baselines that were approved in December 2024.

NNSA and DOE-PM Identified Root Causes and Contributing Factors of the UPF Project Cost Increase and Schedule Delay

NNSA and DOE-PM conducted multiple reviews between 2023 and 2024 to identify the root causes and primary factors contributing to the UPF project’s cost increase and schedule delay. These reviews included NNSA’s January 2023 root cause analysis and its March 2024 update, as well DOE-PM’s August 2023 assessment of the implementation of the UPF project’s EVMS.[20] Collectively, the reviews identified four root causes:

1. poor contractor performance, including increased subcontractor costs of about $770 million, or approximately 20 percent of the total project cost increase, due to increased complexity and inefficiencies in sequencing the work because of frequently changing plans to accommodate missed delivery dates for equipment and materials;

2. direct and indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including $34.1 million in direct costs for control measures including additional employee buses for social distancing, absenteeism, added disinfecting and cleaning requirements, and time off for testing and recovery;

3. labor availability and procurement costs, including paying unplanned hiring and retention incentives because of limited available workforce that increased construction costs and procurement costs by more than $330 million through July 2022; and

4. performance induced budget shortfalls, including the contractor’s late notification in July 2022 of forecasted cost increases to execute its work plans. The contractor’s notification came after DOE submitted its fiscal year 2023 budget justification in April 2022, causing the agency to request an out-of-budget-cycle congressional re-programming of approximately $200 million for the UPF project from other agency funds.

NNSA’s root cause analysis also identified 14 primary factors that contributed to the UPF project’s cost increase and schedule delay. These included the contractor’s failure to execute the approved baseline as planned, inadequate planning that included overestimating labor productivity rates, frequent project replanning, failure to include incentives for timely delivery or penalties for late delivery of key subcontracted work, and global supply chain challenges.[21]

In addition, DOE-PM’s reviews identified concerns and corrective actions for the UPF project. For example, in August 2023, DOE-PM reviewed the project’s EVMS and concluded that the project management culture at both the contractor and at the federal level demonstrated a lack of commitment to effective EVMS implementation.[22] This management culture, in part, led to DOE-PM identifying several practices that collectively contributed to the lack of credible EVMS cost and schedule forecasts. It found a tendency for using other systems and tools to manage the work rather than EVMS, in large part due to the direction of contractor and Y-12 APMO leadership. In addition, DOE-PM’s review noted that there appeared to be a general lack of discipline by the contractor to consistently follow established EVMS procedures and no accountability or consequence from Y-12 APMO for not doing so.[23]

According to DOE-PM’s review, this management culture contributed to EVMS practices that led to the failure of EVMS to provide early warnings of the magnitude of the project’s performance problems. DOE-PM found that these practices included the contractor’s inadequate indirect cost account management, excessive use of a non-compliant scheduling method, and accelerated use of management reserve. Specifically, DOE-PM’s findings include the following:

· Inadequate indirect cost account management. The UPF project contract structure—which DOE-PM characterizes as unique—uses two indirect cost accounts, or pools, to manage costs not associated with a specific subproject.[24] DOE-PM found that while the indirect cost pools are referenced in the contractor’s approved EVMS system description, there was no specific guidance for their use. It also found that the documentation on roles and responsibilities of staff to manage and control these accounts was inconsistent, inaccurate, incomplete, and outdated. Since the start of the project, the accounts nearly doubled with an increase of $948 million, about 25 percent of the $3.85 billion increase in the total cost of the project. As of April 2025, the project was forecasting $64 million in cost overruns above the December 2024 approved re-baseline levels for the indirect cost pools.

· Excessive use of a non-compliant scheduling method. Another issue related to the project’s unique indirect cost account structure is disagreement over whether the use of a method referred to as “schedule visibility tasks-indirect” in a certified EVMS is compliant with the national standard.[25] DOE-PM found that the main problem presented by the use of these indirect tasks in the schedule is they cannot be tracked to completion in EVMS because they do not have specific budget resources associated with them. For example, testing is typically a direct cost within the scope of a project, but the contractor classified it as schedule visibility task funded through the indirect cost accounts. DOE-PM concluded the contractor’s use of these tasks was improper, excessive, and a non-compliant scheduling method. DOE-PM also found that the contractor’s use was inconsistent with the system description the office approved when it certified the project’s EVMS in June 2018. DOE-PM found the contractor’s use of these tasks materially misrepresented the cost and schedule of completed work. DOE-PM further concluded that their excessive use negatively impacted cost and schedule performance reporting, accuracy of current project status, credibility of completion estimates, and limited management’s ability to use the data for decision-making.

· Accelerated use of management reserve. DOE-PM found that the contractor’s accelerated use of management reserve resulted in unreliable EVMS performance metrics. For example, by April 2021, the project contractor spent 90 percent, or $367 million, of the $412 million designated for the total management reserve for the project that was not expected to conclude until late 2025. DOE-PM found that this use of management reserve obscured EVMS performance metrics used for project oversight by minimizing the magnitude of the variance between the project’s planned and actual costs. Ultimately, DOE-PM concluded that the management reserve budget at project approval was inadequate given the contractor’s performance and realized risks within the project.

NNSA Has Closed Most Corrective Actions, but an Important Action Focused on Effective and Reliable Project Performance Data Remains Open

As required by DOE Order 413.3B, NNSA, in coordination with DOE-PM, developed a corrective action plan to address the identified root causes and primary factors contributing to the UPF project’s performance issues. The plan consisted of 20 corrective actions, including three added at DOE-PM’s request to address the EVMS issues it identified. NNSA categorized the corrective actions into four areas: (1) construction; (2) start-up and commissioning activities, (3) baseline management and reporting; and (4) lessons learned.[26] As part of DOE-PM’s April 2024 review of the proposed project re-baseline, it assessed NNSA’s corrective action plan as being well developed and generally adequate to address the root causes of the project’s performance issues.[27] The Deputy Secretary of Energy formally approved NNSA’s root cause analysis and corrective action plan in December 2024.

NNSA and DOE-PM have implemented and closed most of the corrective actions developed to address the UPF project’s root causes.[28] See appendix I for a list of corrective actions and their status. The remaining open action requires the contractor to complete additional steps to address the contractor’s method of including indirect funded scheduling tasks, which cannot be tracked to completion, in the EVMS performance measurement baseline. The contractor submitted an operational exception for the continued use of this method, which was approved in June 2024.[29]

The approved operational exception includes the additional project controls the contractor will implement to mitigate the risk and impact of schedule visibility tasks-indirect on the scope, schedule, and budget associated with these tasks. The operational exception is subject to an annual review by DOE-PM to ensure it is meeting its intended purpose. According to DOE-PM officials, as of August 2025, the operational exception remains in place and the corrective action remains open. While the contractor has created a process to monitor the indirect-funded scheduling tasks, DOE-PM officials told us they are concerned that there may not be acceptable project controls, as part of the operational exception, to identify a downturn in project performance.

The December 2024 integrated baseline review also identified continued concerns in this area and the need for additional corrective action by the contractor.[30] Specifically, the review concluded that the schedule in the contractor’s performance measurement baseline for completing the UPF project startup and commissioning phases by July 2029 appeared unreasonable and unachievable.[31] Among the schedule concerns for these phases is the lack of visibility and traceability of activities that do not have budget resources assigned to them in EVMS. The review found that the schedule includes a high percentage of activities in long sequences being managed through indirect cost pools and scheduled visibility tasks-indirect, which it observed was not a typical practice. It concluded this could potentially mask project performance in its EVMS—as it had previously—through the riskiest technical scope in the project’s schedule.[32]

To address these concerns, the Y-12 APMO directed the contractor to develop alternative performance metrics and a plan for improving the level of detail in the schedule for both direct and indirect activities. In May 2025, Y-12 APMO approved the contractor’s responses and reached agreement on other terms related to implementing the re-baselines.

The Deputy Secretary’s December 2024 approval of the root cause analysis and corrective action plan included the requirement, from DOE Order 413.3B revision in 2023, that DOE-PM, when necessary and as appropriate, shall independently assess the effectiveness of the corrective actions to address and resolve the identified root causes. According to DOE-PM officials, UPF is the first project to have its corrective actions assessed for effectiveness using this review process. The officials indicated this review would likely occur through the office’s role as an observer during the annual peer review process.[33]

NNSA Faces Several Risks and Uncertainties to Complete the UPF Project Within its Approved Cost and Schedule Re-baselines

NNSA faces several risks and uncertainties with respect to whether the corrective actions will be effective for successful completion and commissioning of the UPF project within the approved cost and schedule re-baselines.

Some of the top project risks NNSA identified in its re-baselining proposal include construction performance below the contractor’s fiscal year 2024 schedule forecast and unexpected or unacceptable equipment performance or failure during startup testing and commissioning. As part of its project risk management process, NNSA has identified actions to mitigate the likelihood of these events occurring and the potential impacts on the UPF project’s cost and schedule. These include providing ongoing input to, and annual assessment of, contractor performance and awarding or retaining fees based on achieving, or failing to achieve, contract milestones.

NNSA faces other uncertainties in completing the UPF project, such as being able to complete the work as scheduled. One of the most recent concerns identified in the December 2024 integrated baseline review is that the schedule for completing construction activities is overly dependent on overtime resources from the outset. It found this could be unsustainable and limit the ability to surge work crews if the project began falling behind schedule. Though the review found this to be a “high-risk, low probability” approach to maintaining the project’s critical path to achieving an operational status, it also found the schedule for completing construction of the UPF project to be reasonable and achievable.

Another uncertainty identified by DOE-PM is associated with the Deputy Secretary of Energy’s approval to proceed with the remainder of the UPF project at a substantially lower level of confidence that it will be completed within the approved re-baselines, as shown in table 1.[34] In considering the UPF baseline change proposal, the Deputy Secretary approved the baseline change at a 70 percent confidence level. This resulted in extending the project completion date to January 2032 with about a $50 million increase in the cost estimate over the June 2024 baseline change proposal. However, this is a lower confidence level than was used in approving the initial UPF project baselines and other reviews of the proposed baseline changes. DOE-PM officials told us that because a project seeking a re-baseline has already experienced mistakes and challenges, using a higher confidence level minimizes the risk of their recurrence that would require subsequent re-baselines.

|

Baseline estimate |

Date of estimate |

Confidence level |

Cost estimate |

Estimated project completion date |

|

UPF initial approved baselines |

March 2018 |

85 percent |

$6.5 |

December 2025 |

|

DOE Office of Project Management external independent review |

April 2024 |

95 percent |

$10.5 |

July 2032 |

|

NNSA baseline change proposal |

June 2024 |

50 percent |

$10.3 |

October 2031 |

|

DOE approved re-baselines |

December 2024 |

70 percent |

$10.35 |

January 2032 |

Source National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and

Department of Energy (DOE) information. | GAO‑25‑107330

NNSA project officials told us recommending the re-baselines at a lower confidence level was intended to challenge the contractor to meet heightened performance expectations for completing the project at a lower cost and shorter schedule. In DOE-PM’s review, officials acknowledged that the contractor’s historical performance did not support this approach, but more recent performance had generated optimism that the revised estimates were achievable. NNSA project officials said a combination of contract fee award incentives and schedule contingency may be sufficient to complete the project within the approved re-baselines.

NNSA Will Spend Millions and Lacks a Comprehensive Plan to Mitigate the Impact of the UPF Delay on Continued Operations in Building 9212

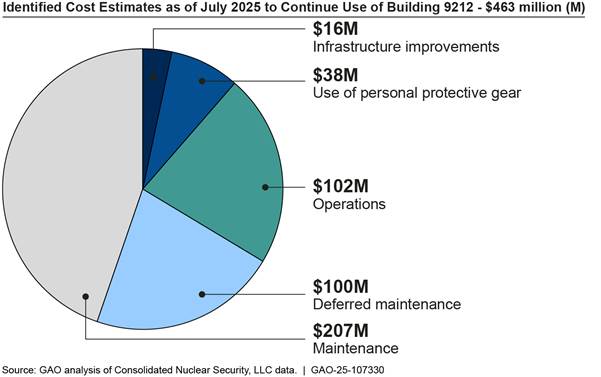

NNSA has begun to identify and mitigate the impact of the delay in UPF full operations. First, the Y-12 M&O contractor has identified about $463 million in additional funds needed from 2026 through 2035 to support continued, safe operations in Building 9212. Second, NNSA plans to produce and store weapon components ahead of when they are needed to mitigate the risk of any disruption of operations in Building 9212. However, NNSA does not have a comprehensive plan, agreed upon by relevant stakeholders—and consistent with other plans NNSA has previously developed—to continue safe operations in Building 9212 until UPF is fully operational.

NNSA Expects to Spend Millions to Continue Processing Uranium in Building 9212

Y-12’s M&O contractor and NNSA have identified about $463 million in additional funds needed from 2026—when NNSA planned to cease operations because of UPF’s planned completion—through 2035 to support continued, safe operations in Building 9212. NNSA plans to conduct enriched uranium processing in Building 9212 for about a year after officials expect the UPF to be fully operational, at an estimated cost of $363 million for operations and maintenance, infrastructure improvements, and protective gear, and an additional $100 million for deferred maintenance through this additional operating period. Figure 2 shows the M&O contractor-identified costs of continued use of Building 9212 through 2035.

Figure 2: Contractor Identified Costs to Continue Use of Building 9212 from 2026 Through 2035 (July 2025)

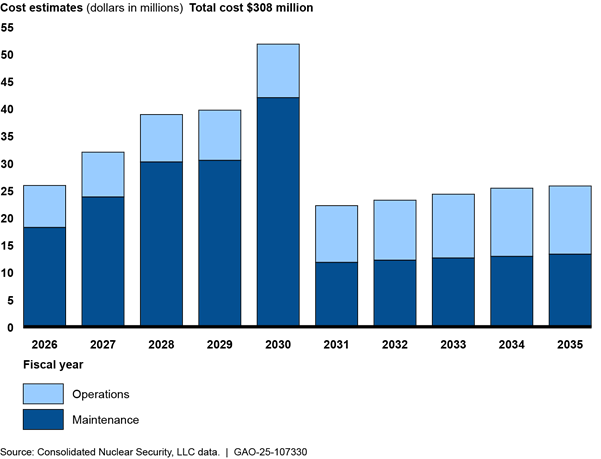

Specifically, the Y-12 M&O contractor estimates it will cost over $308 million to maintain and operate Building 9212 from 2026 through 2035—about $206.6 million estimated for maintenance and about $102 million estimated for operations. See figure 3.

Figure 3: Building 9212 Maintenance and Operations Estimated Costs Until the Uranium Processing Facility is Expected to Be Fully Operational

In addition to costs for maintenance and operations, as of November 2024, the Y-12 M&O contractor has estimated about $16 million will be needed for other infrastructure work, referred to as recapitalization, to improve the condition and extend the life of structures, capabilities, and systems. For fiscal years 2025 through 2030, NNSA contractors told us they plan to use an existing utility energy service contract for recapitalization and other projects for Building 9212, to include electrical, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC); plumbing; roofing; and structural work.[35] Specifically

· most of the work, about $15 million, is planned for fiscal years 2026 and 2027 to conduct maintenance on the roof and replace HVAC exhaust fans to support safe operations in Building 9212. The Y-12 M&O contractor has identified HVAC units as a risk to disrupting operations in Building 9212. The systems are integral to personnel safety by reducing the potential for contaminating the building with uranium and other materials; and

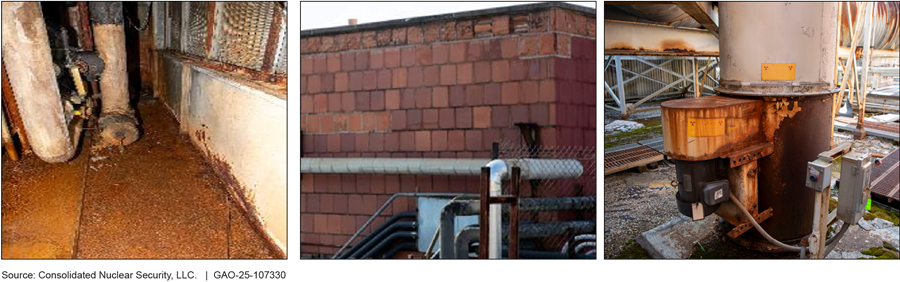

· about $1 million in fiscal year 2030 is planned to be expended to make structural repairs to doors, walls, and the floor in Building 9212. Roofing degradation has caused leaks in the past and continues to be a high risk to disrupting operations in Building 9212.[36] In addition, some piping and degradation of floors and fire barrier walls and doors are considered at high risk to disrupt Building 9212 operations, according to the annual reporting by the Y-12 M&O contractor. See figure 4 photographs of roof, wall, and piping degradation.

Repairs are needed to address degradation to pipes, walls, and the roof of Building 9212 and other support buildings at Y-12.

Further, according to the Y-12 M&O contract representatives, since 2020, high priority maintenance and repair projects for Building 9212 have been deferred, including roof repair, air supply fan repair or replacement, general and emergency lighting, chimney stacks, potable water replacement, electrical transformer work, underground cabling, and sanitary and storm water collections system repair and replacement. According to Y-12 officials, factors contributing to the decision to defer this maintenance include lack of available funding, competing funding priorities, and the expectation that the building would cease operations once UPF was expected to be operational in 2026. More broadly, Y-12’s deferred maintenance estimate, separate from annual maintenance and operations, has grown from about $133 million to $219 million. $100 million for Building 9212, since 2023.[37] According to representatives from the Y-12 M&O contractor, deferred maintenance impacts uranium processing in Building 9212 by reducing equipment reliability, increasing the amount of time equipment is down for repairs, and increasing safety risks to personnel using work-around solutions until equipment or the building is repaired.

Finally, the Y-12 M&O contractor estimates another $38 million will be needed to provide personal protective gear for use in Building 9212. According to Y-12 officials, within the building, personnel and visitors are required to wear personal protective gear to minimize the risk of exposure to uranium because the facility predates modern nuclear safety codes. In contrast, personnel will not need personal protective gear in the UPF due to the modernization of equipment, such as gloveboxes, to process uranium.

Officials from the Enriched Uranium Modernization Program and the Office of Stockpile Management, offices within NNSA’s Defense Programs, and the Y-12 Field Office told us they continue to identify financial impacts of operating in Building 9212 through 2035—8 years after UPF was planned to take over uranium operations. For example, officials from the Enriched Uranium Modernization Program, responsible for enriched uranium technology modernization and the UPF project, told us they are reviewing the impact that the additional funds required to complete UPF and maintain Building 9212 may have on the program’s priorities. Specifically, there may be impacts to the funding planned for the continued operations of buildings deferred from the UPF project scope in June 2012 and other technology programs. See appendix II for information on the cost and schedule of equipment and technology related to the program.

NNSA Is Taking Action to Mitigate the Risk of Production Disruption in Building 9212

NNSA program officials told us how they are mitigating the risk of operational disruption in Building 9212 through 2035 to meet their uranium needs. To mitigate potential delay in the UPF project and to reduce risk to weapons production, NNSA’s Office of Defense Programs is producing components in advance of the planned program schedule using the enriched uranium processing operations and capabilities, such as casting, in Building 9212. In addition, the Office of Naval Reactors will continue to examine opportunities for flexibility in the types of material and processing used to support its fuel stock needs, which mitigates risks of production disruption in Building 9212.[38]

Defense Programs officials expected uranium components for the W87-1 modernization to be manufactured in the UPF beginning in the mid-2020s, using more modern equipment and safer processing than in Building 9212.[39] NNSA officials told us that to mitigate UPF delay and risks of uranium processing disruptions in Building 9212, the W87-1 program office allocated about $50 million in additional funding in fiscal years 2024 and 2025 to produce and store uranium parts and other components for future use.

As of July 2025, officials plan to produce and store parts for the W93—a future warhead intended to support the Navy’s ballistic missile submarine force—beginning in fiscal year 2029. They plan to do so to mitigate the risks of future UPF schedule delays and potential disruption if Building 9212’s production capacity was shut down for an extended period. According to NNSA’s UPF matrix accompanying the fiscal year 2026 budget submission, until stockpile systems program officials have completed their design, the program is unable to fully assess the impact of the UPF delay.

Naval Reactors program officials told us an event that could cause Building 9212 production to be shut down for an extended period is a risk to their mission, heightened by the continued use of Building 9212 for longer than planned due to the delay in UPF full operations. According to officials, the program continues to examine opportunities for flexibility in utilizing different forms of enriched uranium to support its feedstock fuel requirements and use of an off-site processor. Program officials expect this flexibility, and their reserve stocks of enriched uranium, to mitigate any near to mid-term risks from their continued reliance on Building 9212 and its equipment.

However, program officials acknowledged that this strategy of reliance on Building 9212 carries increasing risk to operations and personnel for at least 8 years longer than initially planned. Specifically, operations at the facility could be limited or shut down for some period if a major system needed for safe operations, such as the HVAC, fire suppression system, product casting, or criticality accident alarms systems (which detect radiation levels), breaks down or if there is a significant event (e.g., electrical, fire, flood) or seismic activity or tornadic-level winds.

For example, during the first quarter of fiscal year 2025, multiple events disrupted operations of Building 9212. In one, a pause and “entry into a limited conditions for operations” was declared when fire suppression systems in Building 9212 were unable to operate due to a loss of water pressure and flooding in five buildings. In another example, NNSA and Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board officials confirmed that during the replacement of a sprinkler system component in Building 9212, the contractor led an event investigation and recovery process to resume operations. A sprinkler system drained across a floor designated as a high contamination area into an outside concrete pit.[40] The pit, connected to a storm drain system, did not appear to hold the contaminated water. Finally, in another example, a contractor representative responded to an abnormal condition when uranium material was found on the floor during a maintenance planning inspection of Building 9212. The contractor determined the material leaked from a failed pump outside the area between an unsealed wall of the equipment and stainless-steel floor.[41]

NNSA Does not Have a Comprehensive Plan to Continue Operations in Building 9212

NNSA does not have a comprehensive plan that is agreed upon by relevant stakeholders—and consistent with other plans NNSA has previously developed—to maintain and support continued, safe operations in Building 9212 until UPF is fully operational and Building 9212 uranium processing ceases. NNSA officials told us they will continue operations in Building 9212 to 2035 by relying on the following information:

· The 9212 Transition Strategy Implementation Plan (2023), developed under the assumption that UPF would be operational in 2026, provides steps to improve safety of the move to UPF and to begin decommissioning activities in Building 9212. The four-phased transition plan focuses on the removal of hazardous material and equipment over time and transitioning 9212 personnel to UPF.[42]

· The Enriched Uranium Modernization Mission Strategy (2020) provides a vision of how NNSA expects to integrate the sustainment and modernization of enriched uranium processing and weapons component production capabilities and infrastructure. According to the strategy, the enriched uranium modernization program relies on programs across NNSA to implement agreed-upon activities to extend operations of facilities scoped out of the UPF design in 2012. These facilities include the laboratory (Building 9995), assembly/disassembly and radiography (Building 9204-2E), and metal machining operations (Building 9215).

· In May 2025, NNSA officials at Y-12 and headquarters told us they have begun reviewing Building 9212’s $100 million maintenance backlog, to include planned and unexpected maintenance and repair on the building and equipment. According to these officials, this information, collected through evaluation of the building and equipment by the M&O contractor, was used to inform the fiscal year 2026 annual budget plans and future fiscal years 2027–2030 funding priorities for safe, continued operations.

In March 2024, a Y-12 contractor-led Continued Safe Operating Oversight Team confirmed that the efforts by NNSA outlined in a transition evaluation were sufficient to justify continued safe operations in Building 9212 as late as 2030. In May 2025, the Y-12 contractor-led team recommended an evaluation of Building 9212 to assess operations through 2035.[43] However, this evaluation and the disparate information from the transition plan, program strategy, and maintenance information described previously do not include the same information found in other plans to support safe operations in other uranium processing and support facilities that also need to operate longer than planned.

In contrast, between 2016–2018, the Y-12 M&O contractor produced a comprehensive plan for the uranium processing and support buildings that were scoped out of the UPF project in 2012 due in part to the project’s increased cost estimate of $4.2 to $6.5 billion and to accelerate the completion of the project to transition out of Building 9212. Specifically, following nuclear power industry and others’ leading practices, the Y-12 M&O contractor developed plans that were agreed upon by NNSA stakeholders, such as Y-12 Engineering, Production, and Stockpile Programs, to support safe operations in buildings 9204-2E, 9215 complex, and 9995 into the 2030s and 2040s.[44]

The plan provides information about requirements and funding to sustain capabilities of the facilities for the long term.[45] In addition, Y-12 Field Office officials told us the plans, known together as Extended Life Plans, were developed because the buildings deferred and scoped out of the UPF project would need to continue operations for more than 10 years.

These extended life plans include

· facility and equipment requirements and priorities,

· a 10- to 15-year funding plan for equipment requirements and priorities,

· maintenance and replacement activities,

· natural phenomena hazards information,

· expected operations and associated equipment,

· a log to record changes to the plan, and

· signature of agreement by stakeholders.

NNSA’s supporting documents to continue operations in Building 9212 are not consistent with the comprehensiveness of other plans to extend operations and were not agreed to by stakeholders. Further, the supporting documentation does not include a strategy for safe operations in Building 9212 through 2035, as do the updated plans to extend operations into the 2040s of Building 9204-2E and 9215 complex.

NNSA Y-12 Field Office officials told us NNSA chose not to pursue a similar comprehensive plan for extended operations in Building 9212 despite the building’s condition and industry practices. Officials told us it was not needed because they believed the information from, various documents would be enough to keep the building safely operational until 2026, when the UPF was expected to originally reach full operations. Officials were relying on the transition plan, strategy, and maintenance backlog documents, along with Continued Safe Operations Oversight Team evaluations and ongoing facility and asset management reviews.

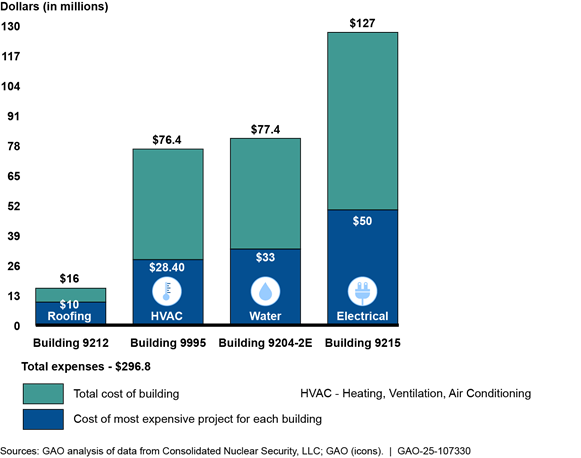

Supported by information in the extended life plans, NNSA officials said they have planned for recapitalization projects, such as electrical and lighting upgrades and new equipment, for the building scoped out of the UPF project. However, officials told us they did not expect to need this type of investment again in Building 9212. Y-12 M&O contractors estimate that it will take an investment of about $16 million in recapitalization projects to continue Building 9212 operations from 2025 through 2030—with 5 years more to reach its estimated date to cease operations. Figure 6 shows the planned investment cost in Building 9212 is primarily for roofing, while investment cost estimates for similarly aging facilities scoped out of the UPF project during the same time frame are for utility infrastructure, with higher cost estimates.[46]

Figure 6: Structural and Utility Recapitalization Investments for Fiscal Years 2025–2030 for Uranium Processing and Support Buildings

The nuclear power industry’s practices recommend plans to support continued operations in facilities over 30 years old, regardless of other factors such as the amount of time before the facility is replaced or recapitalized.[47] NNSA and its Y-12 M&O contractor followed these standard practices, among others, to support the development of plans for the buildings deferred and scoped out of the original UPF project plans, according to NNSA Y-12 Field Office and Enriched Uranium Modernization Program officials. In addition, according to GAO management practices, cost estimate information can be used to determine how budget tradeoffs may progress or hinder a program’s effectiveness.[48]

NNSA decided to develop comprehensive plans with a safety strategy to extend operations of the aging uranium processing and support buildings scoped out the original UPF project. According to Defense Programs officials, the comprehensive plans provide a road map of the actions it will take across NNSA to continue operations and the commitment to take those actions. The plans allow stakeholders a forum to provide input on actions, such as recapitalization investment, needed to continue operations.

Stakeholders also commit—by signature—to the strategy and costs, among other factors, to bridge the gap until new facilities were built. In contrast, the collection of information NNSA is relying on to support operations in Building 9212 do not bridge the gap. In July 2025, the NNSA Y-12 Field Office directed its M&O contractor, as part of its operations, to evaluate whether site and facility infrastructure and required processing equipment support safe mission operations until fiscal year 2035 and as late at 2045.[49] With a comprehensive plan for Building 9212, programs, offices, and NNSA leadership would have information that is consistent with the plans for Buildings 9204-2E, 9215 complex, and 9995. This information could support NNSA leadership’s consideration of risks and priorities when managing tradeoff and funding decisions regarding safe uranium processing for weapons components and fuel material at Y-12 and across the enterprise as the agency conducts large, complex infrastructure projects and modernizes its facilities and equipment.[50]

Conclusions

When it is operational, the UPF will replace Building 9212 as the central hub for uranium processing to support weapon components and the provision of fuel to the Navy. As of December 2024, NNSA estimates the UPF project will cost $3.85 billion more than planned and will take 16 years, instead of 8, from start of construction to full operations for safer uranium processing. NNSA program officials and contractor representatives continue to determine the financial impact of the delay of full operations in the UPF on its uranium processing, having identified about $463 million as of July 2025. The impact of the UPF project’s cost increase and schedule delay will be felt for decades to come at Y-12 and across NNSA’s nuclear enterprises through delays in modernization of equipment and new buildings. We have previously found NNSA has experienced ongoing issues in contract and project management, including in its modernization of uranium processing capabilities.

NNSA developed comprehensive plans to support safe operations in uranium processing and support buildings scoped out of the original UPF project, but not for Building 9212. These plans bridge at least a 10- to 15-year gap that exists until a new building could be built. NNSA directed its M&O contractor to evaluate Building 9212’s site, infrastructure and required processing equipment and report its findings by March 2026. This is a constructive first step to establishing a comprehensive plan. With an estimated 9 to 10 years until the UPF is fully operational, NNSA has an opportunity to develop a comprehensive plan, consistent with the plans for the other buildings that provide stakeholders the type of information needed to address risks to continued safe operations in Building 9212 and better manage tradeoffs among uranium processing and support buildings, modernization projects, and to support the agency’s ability to meet future infrastructure needs.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The NNSA Administrator should direct the Office of Defense Programs to establish a comprehensive plan with relevant stakeholders on actions and related costs to maintain safe operations in Building 9212 until 2035 or when the program operations in the building cease. (Recommendation 1)

We provided NNSA with a draft of this report for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix III, NNSA concurred with our recommendation. In response to our review, NNSA will use the results of the M&O contractor’s evaluation of Building 9212’s site, infrastructure, and required equipment to establish a comprehensive plan with relevant stakeholders on actions and related costs to maintain safe operations. NNSA also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Energy, the Administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at bawdena@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Allison B. Bawden

Director, Natural Resources and Environment

List of Committees

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Chairman

The Honorable Jack Reed

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable John Kennedy

Chair

The Honorable Patty Murray

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Chuck Fleischmann

Chairman

The Honorable Marcy Kaptur

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

Appendix I: Corrective Actions to Address Root Causes of Uranium Processing Facility Project Cost Increase and Schedule Delay

The National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA) Uranium Processing Facility project (UPF), located at the Y-12 National Security Complex (Y-12) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, has experienced performance issues since construction started in 2018. Table 2 provides additional details on NNSA’s implementation of the 20 corrective actions developed to address the four root causes and 14 primary contributing factors to the UPF project’s cost increase and schedule delay.

|

Root cause |

Corrective action |

Status |

|

Contractor performance below expectations |

The UPF contractor will develop a baseline change proposal for approval and the Y-12 National Security Complex (Y-12) federal project office will conduct an integrated baseline review prior to loading a new performance measurement baseline. |

Closed |

|

In addition to standard earned value management reporting, the UPF contractor will measure cumulative variances against two data points: (1) since approval of the original project baselines and start of construction in 2018 and (2) since establishment of the new performance measurement baseline implemented after approval of the baseline change proposal. |

Closed |

|

|

The DOE Office of Project Management (DOE-PM) will update, as needed, department guidelines and requirements for project reporting after a project re-plan or reprogramming. |

Closed |

|

|

DOE-PM will update, as needed, departmental guidance and requirements regarding use of management reserve. |

Closed |

|

|

The Y-12 federal project office will implement additional controls on UPF management reserve draws via formal direction to the contractor. |

Closed |

|

|

The Y-12 federal project office will develop and submit a formal, DOE-wide lessons learned regarding the masking of performance metrics through the early and excessive use of management reserve, under planning the baseline in the near-term to allow for recovery of existing schedule variances, and frequent re-planning. |

Closed |

|

|

The Y-12 federal project office will develop and submit a formal, DOE-wide lessons learned regarding the impacts of the contractor not using schedule incentives or liquidated damages in subcontracted work and for material purchases. |

Closed |

|

|

The Y-12 federal project office will establish incentives for the remainder of the UPF project that place a greater weight on schedule than cost. |

Closed |

|

|

The UPF contractor will conduct a site visit to the Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant to gather lessons learned on startup planning and sequencing and incorporate changes into existing plan and project tools. |

Closed |

|

|

The Y-12 federal project office will assess implementation of startup planning and sequencing changes made as a result of lessons learned from the Waste Treatment and Immobilization Plant. |

Closed |

|

|

The NNSA Office of Infrastructure will standup up a UPF Senior Management Team process to broaden senior leadership visibility to UPF performance. |

Closed |

|

|

The UPF contractor will assess implementation of the estimate at completion monthly update process. |

Closed |

|

|

Direct and indirect impacts from COVID-19 |

The Y-12 federal project office will update the existing federal COVID risk in the UPF risk register to capture potential cost and schedule impacts to remaining work. |

Closed |

|

Labor availability and procurement costs |

The UPF contractor will review the remaining procurements, including spare parts needed before the project completion date, to ensure sufficient lead time has been included in the project schedule. |

Closed |

|

NNSA’s Office of Infrastructure will evaluate the use of complex-wide blanket ordering agreements or indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity vehicles for upcoming nuclear procurements. |

Closed |

|

|

Performance induced funding shortfalls |

The Y-12 federal project office will develop a lessons learned encompassing the impact cost overruns have on future budget requests along with addressing inadequate communication of cost overruns and schedule delays to project stakeholders. |

Closed |

|

The Y-12 federal project office will require consent for use of management reserve and schedule reserve by the contractor. Thresholds will be established by the federal project director and construction contracting officer as part of the integrated baseline review and contract negotiations. |

Closed |

|

|

DOE-PM requested corrective actions |

The UPF contractor will address inadequate cost account manager control of the project specific indirect rate. |

Closed |

|

The UPF contractor will Institute new internal controls to ensure the appropriate use of management reserve. |

Closed |

|

|

The UPF contractor will promptly establish documented processes to limit and manage schedule visibility tasks–indirect while it addresses issues identified in DOE-PM’s review of its implementation of the project’s earned value management system. |

Open |

Source: National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and Department of Energy (DOE) information. | GAO‑25‑107330

Appendix II: Status of the National Nuclear Security Administration’s Equipment and Technology for Uranium Processing

The Enriched Uranium Modernization Program is responsible for modernizing infrastructure for enriched uranium processing, purification, conversion, recycling, and recovery, as well as conducting enriched uranium operations. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to annually submit matrixes relating to uranium capabilities modernization.[51]

In its fiscal years 2025 and 2026 matrices accompanying their budget requests, the program listed activities it accomplished to reduce safety risk in existing facilities, extend the operational life of existing facilities, and further the use of technology to support cleaner, safer operations.[52] The program is developing new uranium processing technology and is investing in key systems such as casting, machining, metal recovery and purification systems, and storage capabilities to ensure long-term reliability of enriched uranium processing. In table 3, we present information on capabilities mentioned in the technology and Uranium Processing Facility matrices. Most of these capabilities have been re-baselined, acknowledging higher costs and later completion dates.

Table 3: National Nuclear Security Administration’s Uranium Processing Technology Status, as of July 2025

|

Capabilities or equipment (location) |

Function |

Examples of causes of project change or re-baseline |

Estimated or baseline completion date |

Revised completion date |

Original total project cost estimate |

Estimated or revised total project cost |

|

Electrorefining (Building 9215) |

Metal purification |

Design, performance, project schedule, delay gas release |

Feb. 2023 |

Jan. 2026 |

$101 |

$139 |

|

Calciner |

Converts low equity solutions |

Design, performance, project management |

Sept. 2023 |

Dec. 2027 |

$108 |

$213 |

|

Chip compactiona (Building 9215) |

Chip compaction and processing |

Funding constraints, design maturity, added scope |

Estimated for April 2032 |

N/A |

— |

$169.8 |

|

Compaction chip processing furnacea |

Chip processing |

Paused due to increase in cost, funding constraint |

Estimated for Sept. 2036 |

N/A |

— |

Estimated at $327 |

|

Microwave casting |

Casting material |

|

N/Ab |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

Source National Nuclear Security Administration information. | GAO‑25‑107330

aThe chip compaction and compaction chip processing furnace projects were initiated as a single project that was expected to be completed by September 2023 at a cost of $108 million. In February 2023, NNSA revised its schedule and cost project baseline to complete the project by June 2026 at a cost of $150 million. Subsequently, the project was split into two separate projects. The chip compaction project baseline was approved in August 2025. The chip processing furnace project is paused.

bN/A is not applicable.

GAO Contact

Allison B. Bawden, bawdena@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the individual mentioned above, Jonathan Gill (Assistant Director), Elizabeth Morris, Mark Braza, Antoinette Capaccio, Gwen Kirby, Michael Meleady, Steven Putansu, Sara Sullivan, and Isis Williams made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]As of April 2025, NNSA has 43 capital asset projects ongoing with a total estimated cost of $58.8 billion. Of these, 13 projects—estimated at $14.2 billion—are meeting their current performance baselines, although nine of the 13 projects have exceeded their original baselines at least once. There are six projects, estimated at nearly $4.7 billion, that are currently expected to exceed their performance baselines. Twenty-one of NNSA’s projects, estimated at $35.5 billion, are in early design and have not yet been baselined, with another three in pre-design, estimated at nearly $4.4 billion, placed on hold.

[2]NNSA relies on management and operations (M&O) contractors to conduct the majority of the work needed to fulfill NNSA’s missions, to include the construction of new facilities such as UPF. M&O contracts are agreements under which the government contracts for the operation, maintenance, or support, on its behalf, of government-owned or government-controlled research, development, special production, or testing establishments wholly or principally devoted to one or more of the major programs of the contracting agency. 48 C.F.R. § 17.601. Consolidated Nuclear Security, LLC. (CNS) has been the Y-12 M&O contractor responsible for UPF construction since July 2014. The UPF project is managed under a separate contract line item included in the overall (M&O) contract for Y-12. As we reported in March 2020, this allows NNSA to incorporate terms and conditions for construction projects not otherwise contained in the overall management and operating contract into that contract. Managing certain construction projects under separate contract line items allows the government to determine strategy and contract type on a case-by-case basis.

[3]GAO, High Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 25, 2025); National Nuclear Security Administration Actions Needed to Improve Integration of Production Modernization Programs and Projects, GAO‑24‑106342 (Washington, D.C.: July 9, 2024).