MEDICARE ADVANTAGE

CMS Oversight of Prior Authorization Criteria Should Target Behavioral Health Services

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107342. For more information, contact Leslie V. Gordon at GordonLV@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25-107342, a report to congressional committees

May 20255

CMS Oversight of Prior Authorization Criteria Should Target Behavioral Health Services

Why GAO Did This Study

Behavioral health conditions were estimated to affect about one-fifth of U.S. adults age 50 or older in 2023 (the most recent data available).

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for GAO to review behavioral health benefits and the use of prior authorization in traditional Medicare and MA. This report describes, for behavioral health services, selected MA organizations’ prior authorization requirements and use of internal coverage criteria for prior authorization decisions. It also examines CMS’s oversight of the use of internal coverage criteria, among other issues.

GAO reviewed information from and interviewed nine selected MA organizations that varied in size, region, and types of plans available and covered about 45 percent of MA beneficiaries in 2024. Specifically, GAO reviewed their reported prior authorization requirements and criteria for behavioral health services. GAO also reviewed CMS guidance and regulations and interviewed CMS officials and provider and beneficiary representatives.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that CMS target behavioral health services in its program audit prior authorization denial reviews and planned reviews of internal coverage criteria. CMS stated that because these services make up a small percentage of MA services, it could not commit to targeting them at this time but would take the recommendation under advisement in the future. GAO maintains the recommendation is warranted, as discussed in the report.

What GAO Found

Medicare covers inpatient and outpatient services for the diagnosis and treatment of behavioral health conditions, which include mental health conditions, such as depression, and substance use disorders, such as opioid use disorder. Medicare Advantage (MA) organizations, which administer Medicare’s private plan alternative, may require providers to request and receive approval before providing some services, a process known as prior authorization. MA organizations must use Medicare coverage criteria when making prior authorization decisions. In some cases, MA organizations may also use internal coverage criteria, which include any criteria not in federal law nor developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) or its contractors. For example, an MA organization might use criteria from a professional society to further define a clinical term in Medicare criteria.

According to CMS, processes like prior authorization are designed to help MA organizations minimize unnecessary services, thereby helping to protect beneficiaries and contain costs. However, studies have indicated that prior authorization and use of internal coverage criteria may hinder MA beneficiaries’ access to care. CMS is responsible for ensuring that MA beneficiaries generally receive at least the same coverage of benefits as beneficiaries enrolled in traditional fee-for-service Medicare, which does not currently require prior authorization for any behavioral health services.

GAO found eight of nine selected MA organizations it reviewed reported requiring prior authorization for behavioral health services, particularly inpatient and other specialized care (see table). In deciding whether to authorize inpatient behavioral health services, seven organizations reported using internal coverage criteria, while the use of internal coverage criteria was less common for other services.

Nine Selected MA Organizations’ Reported Prior Authorization Requirements and Criteria for Key In-Network Behavioral Health Care Services

|

Behavioral health services |

Number of selected MA organizations with prior authorization requirements |

Number of selected MA organizations that used internal coverage criteria to authorize care |

|

Inpatient level of care |

8 |

7 |

|

Partial hospitalization |

6 |

3 |

|

Transcranial magnetic stimulation |

7 |

1 |

Source: Selected Medicare Advantage (MA) organizations. | GAO-25-107342

Note: Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a specialized service used to treat severe depression. For more details, see table 2 and appendix II in GAO-25-107342.

CMS has not targeted behavioral health services in its oversight of MA organization prior authorization. During its annual program audits, CMS reviews MA organization denials of selected authorization requests, including how MA organizations applied any internal coverage criteria used. However, CMS officials said they did not target any behavioral health requests in recent audits even though CMS has a goal of improving access and quality of behavioral health services for beneficiaries in its programs. As a result, CMS does not have enough information to determine whether or to what extent MA organizations’ use of internal coverage criteria affects MA beneficiaries’ access to behavioral health services. CMS also announced plans to annually review MA organizations’ internal coverage criteria for selected services starting in 2026. CMS had not released final plans as of May 2025, including indicating if these reviews will target any behavioral health services.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

ASAM |

American Society of Addiction Medicine |

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HMO |

health maintenance organization |

|

LCD |

local coverage determination |

|

LOCUS |

Level of Care Utilization System |

|

MA |

Medicare Advantage |

|

NCD |

national coverage determination |

|

PPO |

preferred provider organization |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

May 29, 2025

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chair

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chair

The Honorable Frank Pallone, Jr.

Ranking Member

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jason Smith

Chair

The Honorable Richard Neal

Ranking Member

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

Behavioral health conditions, which include mental health conditions and substance use disorders, affect many Medicare beneficiaries. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) estimated that about one-fifth of U.S. adults age 50 or older had a behavioral health condition in 2023.[1] The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the agency within HHS that administers and oversees the Medicare program, stated that addressing the behavioral health needs of its roughly 68 million Medicare beneficiaries is a key priority, and its Behavioral Health Strategy includes the goals of improving access to and quality of behavioral health care and services.[2]

Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage (MA), Medicare’s private plan alternative, are required to cover a range of services for diagnosing and treating behavioral health conditions.[3] Treatment for behavioral health conditions can help individuals manage their symptoms, reduce or stop substance use, and improve their quality of life. When these disorders go untreated, individuals may suffer potential consequences, such as worsening health, frequent emergency department visits, hospitalizations, or premature death. For these reasons, access to services is important to help Medicare beneficiaries manage their behavioral health conditions. However, CMS has stated that older adults face significant barriers to accessing behavioral health services, and poor behavioral health outcomes are especially detrimental to older adults.[4] In March 2024, the HHS Office of Inspector General reported that 3 percent of MA enrollees received treatment from a behavioral health provider in 2023.[5]

CMS and MA organizations may require that providers request and receive approval from CMS or a beneficiary’s MA organization before delivering certain services—a process referred to as prior authorization.[6] However, this requirement is rare in traditional Medicare, and, as with the majority of services, CMS does not currently require prior authorization for any behavioral health services in traditional Medicare.[7]

According to CMS, processes like prior authorization are designed to help MA organizations minimize unnecessary services, thereby helping to contain costs and protect beneficiaries from receiving unnecessary care.[8] When approving or denying requests for care, MA organizations compare a beneficiary’s unique circumstances against criteria to determine if the care is medically necessary and covered by the MA plan. For example, an MA organization might confirm that a beneficiary is diagnosed with an opioid use disorder before approving coverage for an opioid treatment program. MA organizations must apply Medicare coverage criteria to make decisions about whether care is medically necessary. If Medicare coverage criteria are not available, not detailed enough to make consistent decisions, or include flexibility that allows for coverage of care in circumstances not specified in the criteria, MA organizations may also use internal coverage criteria (i.e., any criteria that are not used in traditional Medicare).[9]

We and the HHS Office of Inspector General have identified issues with the prior authorization process and criteria used to decide whether care requests will be approved. For example, in March 2022 we found that prior authorization can cause beneficiaries to experience delays in receiving needed care.[10] We also found that variation in criteria can affect beneficiaries’ access to mental health care.[11] Additionally, a review from the HHS Office of Inspector General found that 13 percent of care requests denied by MA organizations met Medicare coverage criteria.[12] The Inspector General review found that in some cases, this was because MA organizations were applying their own more stringent criteria to decide if care was medically necessary.

CMS has taken steps to help ensure that MA organizations’ prior authorization policies do not delay or discourage medically necessary care. For example, CMS required MA organizations to make internal coverage criteria publicly accessible beginning in 2024.[13] In addition, in 2024, CMS initiated reviews of MA organizations’ compliance with new prior authorization requirements as part of its program audits.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, includes a provision for us to review prior authorization of behavioral health services in traditional Medicare and MA, among other topics.[14] In this report, we

1. describe selected MA organizations’ use of prior authorization requirements for behavioral health services and stakeholders’ views on its potential advantages and disadvantages;[15]

2. examine selected MA organizations’ use of internal coverage criteria for prior authorization of behavioral health services and CMS’s oversight of the use of these criteria; and

3. examine the extent to which selected MA organizations’ internal coverage criteria were publicly accessible.

To describe selected MA organizations’ use of prior authorization requirements for behavioral health services and stakeholders’—MA organizations, provider associations, and others—views on its potential advantages and disadvantages, we reviewed information from a nongeneralizable sample of nine selected MA organizations.[16] We selected these MA organizations for variation in number of enrollees, region, and types of plans available. These MA organizations collectively provided coverage to about 45 percent of MA beneficiaries in 2024. We reviewed information and documentation provided by MA organizations about the behavioral health services for which they required prior authorization in 2024. We also interviewed MA organization representatives about the reasoning for applying prior authorization requirements to behavioral health services and reviewed relevant literature about prior authorization. We interviewed representatives from a nongeneralizable selection of six behavioral health provider associations—including practicing behavioral health providers—and a beneficiary advocacy group about their perspectives on prior authorization for behavioral health services in MA.[17] We selected groups that represent providers of behavioral health services (mental health, substance use disorders, or both) and are national in scope.

To examine selected MA organizations’ use of internal coverage criteria for prior authorization of behavioral health services and CMS’s oversight of criteria, we reviewed information and documentation from selected MA organizations about the source of criteria used to make prior authorization decisions for behavioral health services, including whether or not they used internal coverage criteria.[18] For five of those services—acute inpatient mental health, inpatient alcohol detoxification, opioid treatment programs, outpatient mental health visits, and transcranial magnetic stimulation—we reviewed the specific criteria that MA organizations used.[19] We selected these services based on availability of Medicare criteria and variation in service types and levels of care. We did not assess whether MA organizations were making prior authorization decisions in accordance with the criteria we reviewed. We interviewed five organizations that develop the internal coverage criteria most commonly used by selected MA organizations.[20] We also reviewed CMS guidance, regulations, and other documents, and interviewed CMS officials about their oversight efforts. We compared CMS’s oversight efforts with statutory requirements and with goals established in the agency’s Behavioral Health Strategy.

To examine the extent to which selected MA organizations’ internal coverage criteria were publicly accessible, we compared selected MA organizations’ public websites and plan documents with recent CMS regulations regarding the public accessibility of criteria. We reviewed MA organizations’ public websites to locate the specific criteria that MA organizations told us they used to assess medical necessity for the five selected behavioral health services. We reviewed CMS guidance, regulations, and other documents, and interviewed CMS officials about their related policy efforts.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to May 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Behavioral Health Conditions and Services

Behavioral health conditions include mental health conditions (e.g., anxiety disorders; mood disorders, such as depression; post-traumatic stress disorder; and schizophrenia) and substance use disorders (e.g., alcohol use disorder and opioid use disorder).

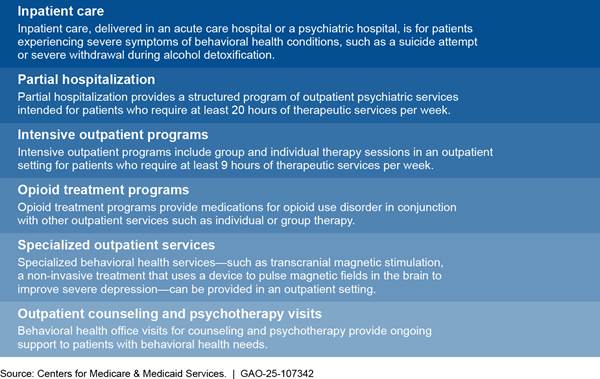

There are a variety of inpatient and outpatient services available to diagnose and treat behavioral health conditions. To help guide behavioral health treatment decisions, professional societies have defined different levels of behavioral health care services corresponding to the intensity of treatment. For example, the American Association for Community Psychiatry describes seven levels of behavioral health care based on factors like setting, security, treatment type and frequency, staff type and amounts, and types of supportive services available in its Level of Care Utilization System for Psychiatric and Addiction Services (LOCUS) guidelines.[21] Similarly, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) describes five levels of substance use disorder care based primarily on care setting.[22] For both mental health and substance use disorder care, inpatient hospital care is the highest level of care, and outpatient services are lower levels. (See fig. 1.)

Medicare and MA Coverage Decision Criteria and Processes

Medicare covers behavioral health services if they are reasonable and necessary for diagnosis or treatment of a behavioral health condition.[23] Coverage criteria for reasonable and necessary care are set forth in federal laws and regulations, Medicare benefit manuals, and national policies called national coverage determinations (NCD).[24] For example, one NCD states that inpatient hospital care is considered reasonable and necessary during alcohol detoxification if there is a high probability of medical complications. Medicare Administrative Contractors, which process claims for traditional Medicare, may also define coverage criteria in local coverage determinations (LCD) for particular services.[25] As a result, LCDs may not be available or identical in every region.

To ensure care is reasonable and necessary for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, CMS generally reviews a small sample of claims to determine if care was delivered in accordance with its coverage policies after a provider has submitted a claim for payment.[26] Like the majority of services, CMS does not currently require prior authorization for any behavioral health services in traditional Medicare.[27]

In MA, CMS contracts with MA organizations to manage the care of beneficiaries enrolled in their plans and pays MA organizations a set prospective amount for each beneficiary. CMS makes these payments regardless of how much the MA organization then pays providers or the number of services beneficiaries use. MA organizations assume the financial risk if their spending exceeds the CMS payments; however, if their spending is less than the CMS payment, the MA organizations are generally permitted to retain some or all of the balance. This can create a financial incentive for MA organizations to limit or inappropriately deny coverage or payment for necessary services. This is in contrast to traditional fee-for-service Medicare, which reimburses providers for each service delivered and can create a financial incentive to perform more services than necessary.

To ensure care is reasonable and necessary for MA beneficiaries, some MA organizations develop processes to verify requests for certain services before treatment (i.e., prior authorization) or during treatment (i.e., concurrent review). MA organizations must have a procedure for making timely decisions on all requests for items or services, including the items and services subject to prior authorization.[28] Generally, MA organizations require providers to submit documentation, such as a diagnosis or description of current symptoms, to the MA organization to support that the requested care is necessary. Reviewers from the MA organization or their contractors will review this documentation to verify that coverage and benefit criteria have been met for the service.[29] MA organizations use Medicare coverage criteria, and if needed, internal coverage criteria. Reviewers may require that providers send additional information or have conversations with a clinical reviewer to aid in their review.

MA organizations must generally cover items or services that would be covered in traditional Medicare and apply Medicare coverage criteria to make decisions about whether care is medically necessary for a specific individual. CMS has a longstanding policy that MA organizations can also use additional internal coverage criteria to make decisions, but the criteria must not be more restrictive than Medicare coverage criteria.[30]

CMS has stated that it does not consider internal coverage criteria to be more restrictive than Medicare coverage criteria if the criteria comply with CMS regulations. Starting in contract year 2024, CMS specified that MA organizations may only use internal coverage criteria if Medicare coverage criteria do not exist, do not include enough detail to make consistent medical necessity decisions, or explicitly allow for coverage flexibility.[31] Furthermore, internal coverage criteria must be based on current evidence in widely used treatment guidelines or clinical literature and can be developed by the MA organization or third-party developers including the MA organization’s contractors, vendors, professional societies, and states. CMS also specified that all internal coverage criteria must be publicly accessible to enrollees, providers, CMS, researchers, and other stakeholders to provide transparency and assurance that the coverage criteria are rational and supportable.

|

Example of Internal Coverage Criteria for an Inpatient Hospital Stay for the Treatment of Alcoholism A Medicare Advantage (MA) beneficiary has decided to start treatment for alcohol use disorder. In the acute stages of alcohol withdrawal, many hospitals offer detoxification services, and the beneficiary’s provider thinks that these services are necessary to manage the beneficiary’s symptoms. Medicare coverage criteria are available for inpatient alcohol detoxification in a national coverage determination (NCD). The NCD states that traditional Medicare will generally pay for up to 5 days of detoxification in an inpatient hospital setting if there is a high probability of medical complications. However, these criteria do not contain details on a consistent approach to deciding whether there is a high probability of complications. An MA organization may choose to supplement the NCD with internal coverage criteria from a professional society. These internal coverage criteria state that inpatient detoxication is considered necessary if the results of a standard assessment are greater than 19. The MA beneficiary’s provider conducts and documents the standard assessment and shares the records with the MA organization to show that the score was high enough to warrant inpatient detoxication services. |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and professional society documents. | GAO‑25‑107342

CMS’s Role in MA Organization Oversight

CMS oversight of MA organizations is designed in part to ensure that, in their pursuit of cost-effective care, MA organizations do not inappropriately restrict beneficiaries’ access to care. CMS oversees MA organizations’ compliance with federal requirements related to access to care by conducting program audits. Routine program audits evaluate MA organizations’ compliance with a variety of core program requirements.[32] Among other things, these audits evaluate prior authorization processes and criteria by reviewing procedures and a selection of denied prior authorization requests.[33] CMS conducts these audits annually for a subset of MA organizations. CMS selects the MA organizations being audited based on its internal risk analysis and factors such as the length of time since their last audit or complaints received from whistleblowers, attorneys, and advocacy groups, according to CMS officials.

CMS can also initiate focused program audits that review MA organizations’ compliance with a limited set of specific regulations. For example, in 2024, CMS conducted focused program audits to specifically evaluate compliance with regulations related to prior authorization, including reviewing a selection of denied prior authorization requests.[34]

Selected MA Organizations Reported Prior Authorization Requirements for Higher Levels of Behavioral Health Care; Stakeholders Noted Potential Advantages and Disadvantages

Most Selected MA Organizations Have Prior Authorization Requirements for Inpatient, Partial Hospitalization, and Specialized Behavioral Health Care

Selected MA organizations most often applied prior authorization requirements to in-network behavioral health services for higher levels of care and a specialized treatment. For example, of the nine selected MA organizations in our review, eight told us that the organization required prior authorization for inpatient levels of care, while six told us that the organization required prior authorization for partial hospitalization.[35] In addition, seven MA organizations required prior authorization for transcranial magnetic stimulation, a specialized service. No selected MA organizations required prior authorization for in-network outpatient counseling and psychotherapy visits, which are lower intensity services. See table 1. See appendix I for available data on all MA organizations’ prior authorization requirements for behavioral health service categories.

Table 1: Selected Medicare Advantage (MA) Organizations’ Reported Prior Authorization Requirements for In-Network Behavioral Health Care Services, 2024

|

Behavioral health services |

Number of selected MA organizations with prior authorization requirement (out of 9) |

|

Inpatient level of care (including psychiatric care and detoxification) |

8 |

|

Partial hospitalization |

6 |

|

Intensive outpatient services |

2 |

|

Specialized outpatient services Transcranial magnetic stimulation Electroconvulsive therapy Psychological testing |

7 2 1 |

|

Outpatient counseling and psychotherapy visitsa |

0 |

Source: GAO analysis of information from selected MA organizations. | GAO‑25‑107342

Notes: GAO collected information from nine selected MA organizations about the behavioral health services for which they required prior authorization. When possible, we corroborated the information with data from the system that populates the CMS Plan Finder website, which provides information to users on Medicare Advantage plan benefits. These nine MA organizations enroll about 45 percent of MA beneficiaries.

CMS requires MA organizations to cover emergency and urgently needed services, including inpatient admissions, and does not allow MA organizations to require prior authorization before beneficiaries access these services.

aOne selected MA organization told us that while they generally do not require prior authorization for outpatient counseling and psychotherapy visits, cases where treatment length or frequency is higher than average are subject to concurrent review.

MA organizations cannot require prior authorization for emergency admissions, which may precede inpatient behavioral health care.[36] Instead, once a beneficiary is admitted, some MA organizations may conduct a concurrent review to authorize a certain number of days of medically necessary inpatient care at a time. Concurrent review, like prior authorization, involves comparison of patient’s circumstances to coverage criteria to decide whether care is medically necessary, although the beneficiary is already receiving care.

Representatives from the selected MA organizations said that they consider applying prior authorization requirements if a service is overutilized, expensive, or high-risk. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission also has reported that prior authorization is most often required for relatively expensive services, such as inpatient hospital stays, and is rarely required for preventive services.[37]

Stakeholders Discussed Potential Advantages and Disadvantages of Prior Authorization Requirements

Stakeholders we spoke with—including representatives from selected MA organizations, providers associations, and others—discussed the potential advantages and disadvantages of prior authorization.

Potential Advantages of Prior Authorization

Representatives from selected MA organizations described the ways that prior authorization can help ensure care is coordinated and necessary. Representatives of six MA organizations said prior authorization can help ensure beneficiaries’ care is coordinated. For example:

· One MA organization’s representatives said a beneficiary experiencing an acute mental health episode will likely require long term care management, especially when they leave inpatient care. Beneficiaries may need support such as transportation, durable medical equipment, or appointments with in-network providers for lower levels of care after discharge, and the authorization process serves as an alert for MA organizations to coordinate these services.

· Four MA organizations’ representatives also mentioned using the authorization process to coordinate members’ transitions to less restrictive care settings at the right time.

· Representatives of one MA organization noted that higher level services are expensive for beneficiaries who share the cost of care, so transitioning to lower levels of care as soon as the beneficiary is ready can reduce financial strain.

MA organizations’ representatives said prior authorization can help ensure members are receiving care that is medically necessary. Representatives of two selected MA organizations said that they may apply prior authorization to reduce increases in utilization or overutilization in some regions. For example, one MA organization’s contractor that reviewed prior authorization requests for behavioral health services said that providers in some regions tended to keep patients in higher levels of care (i.e., inpatient care and partial hospitalization) for longer periods of time than clinical standards require. The MA organization contractor said they would recommend that the plans in those regions add a prior authorization requirement to higher level services to ensure clinical standards are applied consistently.

We have previously found that prior authorization can help reduce the use of unnecessary care, yielding cost savings. In 2018, we reported on prior authorization programs in traditional Medicare. We found that expenditures for services subject to prior authorization were lowered by $1.1 to $1.9 billion compared with what would have been expected had the programs not been implemented, resulting in savings for the Medicare program.[38]

Additionally, representatives of two selected MA organizations said prior authorization requirements can help ensure that specialized and newer services are provided in an evidence-based way. For example, after one MA organization observed an increase in billing for transcranial magnetic stimulation in their service area, they decided to require prior authorization to ensure the service was being provided according to clinical evidence for treating severe depression and not as a first-line treatment.

Potential Disadvantages of Prior Authorization

Stakeholders discussed how prior authorization can adversely affect beneficiaries’ timely access to care and create additional burden for providers. Representatives from four behavioral health provider associations and one MA organization said prior authorization may impede beneficiaries’ access to medically necessary care. For example, one association’s representatives said to get transcranial magnetic stimulation therapy approved, MA organizations may require beneficiaries to go through multiple trials and providers to submit redundant information to demonstrate the necessity of the treatment. A 2022 HHS Office of Inspector General review of denied prior authorization requests in MA found that 13 percent of denials would have been covered in traditional Medicare.[39] These denials—even if approved after an appeal—have direct effects on beneficiaries’ timely access to medically necessary care.

Representatives from five behavioral health provider associations said prior authorization can delay care. For example, a provider may want to discharge a beneficiary in an inpatient mental health unit to a partial hospitalization program or intensive outpatient program. If the beneficiary’s MA organization requires prior authorization for those settings, there may be a delay for the provider to understand what level of care the organization will authorize and then arrange that care. Representatives from one MA organization acknowledged that the wait time for a prior authorization decision can potentially create additional stress for beneficiaries. Five MA organizations’ representatives said they have developed processes and policies to address requests quickly, with four MA organizations allowing providers to submit prior authorization requests virtually to expedite the process.

Prior authorization also may lead to disruptions in care, according to four selected provider organizations in our review. For example, representatives from one behavioral health provider association said it is key to get a beneficiary into treatment for substance use disorder as soon as they are ready. If prior authorization delays care, even by an hour or two, it may lead to negative patient outcomes, according to these representatives. In a 2023 survey of 1,000 physicians, 78 percent of physicians responded that prior authorization can at least sometimes lead to treatment abandonment.[40]

In another example, representatives of two behavioral health provider associations noted that MA organizations may not approve enough days of inpatient care for beneficiaries who may need extra time for providers to ensure that they are well supported after discharge. These beneficiaries may be unhoused, low income, or have comorbidities, and may need time to locate stable housing. If a beneficiary is discharged to a lower level care setting without needed supports in place, providers we spoke with said there may be a greater chance of readmission. Representatives of four behavioral health provider associations commented that MA organizations often do not cover key services to help beneficiaries transition out of inpatient settings, which can compromise recovery.[41]

The prior authorization process is often resource-intensive for providers, according to representatives of four behavioral health provider associations. MA organizations may initially authorize several days of inpatient care, but providers must submit additional requests for more days, which requires additional staff time and attention. When requests are denied, the provider may have multiple conversations with peer clinicians representing the MA organization to review the case. This process varies by MA organization, including whether the MA organization accepts authorizations via fax or web portal. Representatives from one provider organization said MA organizations also vary in whether reviews are conducted by the same plan reviewer or the reviewer changes with every authorization request.

Representatives from one behavioral health provider association described the experience with authorization for inpatient behavioral health care under MA versus traditional Medicare. In MA, they said that they experienced multiple reviews and submitted many documents to demonstrate medical necessity. In contrast, traditional Medicare requires a physician’s certification that the care is medically necessary, and CMS annually reviews a small sample of claims to determine if care was delivered in accordance with its coverage policies.

Several research studies that discuss prior authorization broadly have also found that prior authorization is associated with provider burden.[42] For example, in a 2023 American Medical Association survey of 1,000 physicians, 35 percent reported that they have staff who work exclusively on prior authorizations.[43] Further, 95 percent reported that prior authorization somewhat or significantly increases burnout. Another survey of providers, patients, and private payers found that prior authorization takes up a significant amount of time for clinicians. Among provider respondents, nurses spent approximately 3 hours a week on prior authorizations, and physicians spent 1 hour per week.[44]

Most Selected MA Organizations Reported Using Internal Coverage Criteria to Authorize Behavioral Health Services, but CMS Oversight Has Not Targeted These Services

Most selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria for authorizing at least one behavioral health service. These criteria were developed by a small number of common sources. However, CMS does not know whether or to what extent this use of internal coverage criteria affects access to behavioral health care because current CMS oversight of internal coverage criteria does not target behavioral health services.

Most Selected MA Organizations Reported Using Internal Coverage Criteria to Authorize Behavioral Health Services When Medicare Criteria Were Not Specific or Available

Most selected MA organizations reported requiring authorization for at least some behavioral health services, especially inpatient care. To make these authorization decisions, seven of nine selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria to authorize inpatient behavioral health care. Fewer of the selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria for authorizing other behavioral health services (see table 2).

Table 2: Nine Selected Medicare Advantage (MA) Organizations’ Reported Use of Internal Coverage Criteria for In-Network Behavioral Health Care Services, 2024

|

Behavioral health services |

Number of selected MA organizations that required prior authorization |

Number of selected MA organizations that used internal coverage criteria to authorize care |

|

Inpatient level of care (including psychiatric care and detoxification) |

8 |

7 |

|

Partial hospitalization |

6 |

3 |

|

Intensive outpatient services |

2 |

1 |

|

Specialized outpatient services Transcranial magnetic stimulation Electroconvulsive therapy Psychological testing |

7 2 1 |

1 1 1 |

|

Outpatient counseling and psychotherapy visits |

0 |

1a |

Source: GAO analysis of information from selected MA organizations. | GAO‑25‑107342

Notes: We reviewed prior authorization requirements for behavioral health services reported by nine selected MA organizations that covered about 45 percent of MA beneficiaries in 2024. We also reviewed information reported by selected MA organizations about the criteria used to make decisions about whether care was medically necessary, including whether they used criteria from non-Medicare sources (i.e., internal coverage criteria).

This table includes a variety of behavioral health care services for which MA organizations reported requiring prior authorization. Inpatient behavioral health care includes care for acute mental health and substance use disorder symptoms, such as providing medical support during the alcohol detoxification and withdrawal process. Partial hospitalization is a structured outpatient service for patients who need 20 or more hours of behavioral health care each week, and intensive outpatient programs offer similar services for patients who need 9 or more hours of care a week. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and electroconvulsive therapy are specialized services often used to treat severe depression. Psychological testing is used to identify a diagnosis and guide treatment. Outpatient counseling or psychotherapy visits provide ongoing support.

aOne MA organization reported using internal coverage criteria to conduct concurrent reviews of outpatient mental health visits if the number of visits exceeds the average number of visits for the service as determined by the MA organization, and another reported using internal coverage criteria to approve authorization requests for outpatient mental health visits with out-of-network providers.

|

When Can Medicare Advantage Organizations Use Internal Coverage Criteria? Medicare Advantage organizations must apply Medicare coverage criteria to make decisions about whether care is medically necessary. Medicare Advantage organizations may supplement available Medicare criteria with internal coverage criteria if: · There are no Medicare coverage criteria available for the service, · Reviewers need additional criteria to consistently determine whether a service is medically necessary, or · Medicare coverage criteria include flexibility that explicitly allows for the coverage of care in circumstances not specified in the criteria. Source: 42 C.F.R. § 422.101(b)(6)(i). | GAO‑25‑107342 |

See appendix II for more information on the sources of MA organization prior authorization criteria.

Representatives of six MA organizations said they supplemented Medicare coverage criteria when these criteria were not available or specific enough to make consistent medical necessity decisions. CMS officials noted it is not possible for CMS and its contractors to be prescriptive about every health care scenario or diagnosis in Medicare coverage policies. Internal coverage criteria can fill in gaps in Medicare coverage criteria and help ensure that MA organization reviewers have enough guidance to make consistent authorization decisions for a wide variety of circumstances.

To characterize why selected MA organizations used internal coverage criteria, we reviewed use of Medicare coverage criteria and internal coverage criteria for five selected behavioral health services. We found that seven selected MA organizations supplemented Medicare coverage criteria in federal law and regulations or manuals, and five MA organizations used internal coverage criteria to supplement criteria in national coverage determinations (NCD). The selected MA organizations sometimes used internal coverage criteria to supplement Medicare coverage criteria in available local coverage determinations (LCD), although this varied by service.[45]

Laws, regulations, and manuals. Seven selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria to supplement Medicare coverage criteria in laws, regulations, and manuals for selected behavioral health services. When we asked MA organizations which criteria they used to make prior authorization decisions, two specifically said they used criteria from manuals. These coverage criteria—such as manuals for inpatient mental health care and opioid treatment programs—tended to be general to account for a wide variety of situations and services. For example, the Medicare Benefit Policy Manual for Opioid Treatment Programs focuses on defining the payment methodology and the qualifications of programs to offer services as defined in statute, and only states that services must be reasonable and necessary for the diagnosis or active treatment of the individual’s condition.[46]

NCDs. Five selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria to supplement the NCD for inpatient detoxification, while three reported using the NCD to make prior authorization decisions. NCDs for behavioral health services contained more service-specific details than laws, regulations, and manuals.[47] For example, the NCD for inpatient alcohol detoxification includes a summary description of the medical conditions that qualify and a general time frame for the service. However, this NCD does not provide specific clinical thresholds to apply as criteria, such as a particular score on a standardized instrument to assess and diagnose the severity of alcohol withdrawal, which some internal coverage criteria include.

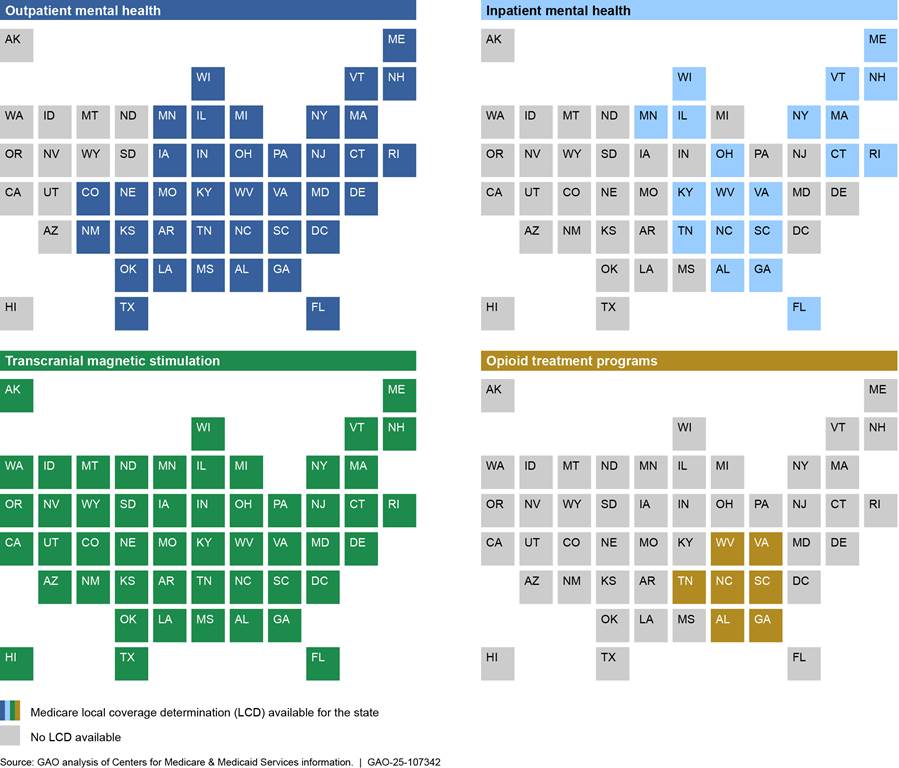

LCDs. Selected MA organizations sometimes reported using internal coverage criteria to supplement LCDs, although use varied depending on whether LCDs contained specific clinical criteria, included flexibility to cover additional circumstances, and were available in the region.[48] One of the seven selected MA organizations with a prior authorization requirement for transcranial magnetic stimulation reported using internal coverage criteria. LCDs for transcranial magnetic stimulation were available nationwide and contained detailed clinical thresholds for judging whether care should be covered. Conversely, four of the five MA organizations with LCDs available for inpatient mental health care also reported using internal coverage criteria to authorize care.[49] LCDs for inpatient mental health care offered flexibility for coverage in unspecified circumstances by stating that the listed criteria were examples rather than an inclusive list. The two selected MA organizations that required authorization for outpatient mental health visits reported using internal coverage criteria in the 13 states without an available LCD.[50] (See fig. 2 for more information on regional availability of LCDs.)

Figure 2: Availability of Medicare Local Coverage Determination Criteria for Four Selected Behavioral Health Services

Notes: Local coverage determinations (LCD) are Medicare coverage criteria that specifically apply to one of the 12 Medicare regions. Medicare Administrative Contractors can opt to define regional coverage criteria if national coverage criteria are not available or there is a need to further define national criteria for the region.

We reviewed available LCDs for five selected services and

identified LCDs for four services. Inpatient mental health care is intended for

patients in need of acute care, whereas outpatient mental health care—such as

psychotherapy or counseling—is ongoing care delivered in an outpatient setting.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a specialized service used to treat severe

depression. Opioid treatment programs provide medications for opioid use

disorder in conjunction with other outpatient services such as individual or

group therapy. There were no LCDs available for one selected service—alcohol

detoxification—which has national coverage criteria available.

Selected MA Organizations Used Internal Coverage Criteria from Common Sources

The seven selected MA organizations that used internal coverage criteria reported sourcing criteria from a small number of common third-party criteria developers: two criteria vendors, three professional societies, and one state agency.[51] Representatives of five MA organizations said that using criteria from common sources was helpful as a common language between providers and MA organizations.

Criteria Vendors

Five selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria from two criteria vendors. These vendors develop criteria based on clinical literature and widely accepted treatment guidelines, and offer products to insurers, providers, and other entities. Vendors make their proprietary criteria available through software applications with a variety of features, including presenting criteria in an assessment format to facilitate reviews. Criteria vendors told us it is possible for MA organizations to modify vendor-developed criteria, but it is uncommon.

When we compared the criteria from the two criteria vendors for the same service, we found the content was similar. For example, in the criteria for inpatient mental health and inpatient detoxification, both vendors cited clinical guidelines from professional societies as well as clinical literature. One vendor’s criteria provided more specific clinical benchmarks and examples of relevant symptoms.

Professional Societies

Three selected MA organizations reported using guidelines from professional societies as internal coverage criteria—American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) criteria for substance use disorder care, Level of Care Utilization System for Psychiatric and Addiction Services (LOCUS) criteria for mental health care, and a guide from the American Psychological Association for psychological and neuropsychological testing. Two of these professional societies license their guidelines—ASAM and LOCUS—to insurers, providers, and other entities to use as criteria for identifying the appropriate level of care for a patient. Both professional societies make these criteria available through software applications that translate the criteria into assessments. The American Psychological Association guide is publicly available.

Representatives from the three professional societies said that their guidelines are well suited for use as internal coverage criteria, although the guidelines were initially intended for use by providers. Representatives from two societies explained that the guidelines assess a variety of factors—such as risk of harm, recovery environment, and co-morbidities—to determine an appropriate level of care for a patient. Representatives from all three professional societies said that more MA organizations have been using their guidelines as criteria in the past few years. In response, professional societies have revised or are working to revise their criteria documentation and are working to increase training to promote appropriate and consistent application for decision making, according to representatives.

States

Two of the selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria developed by a state agency for substance use disorder services. Representatives from these MA organizations said that clinicians in their service areas are required to apply these criteria when developing care plans for certain patients, so they adopted these criteria to use as a common language with providers.

In addition to using criteria from third party developers, two of the selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria developed by the organization or its contractor. For transcranial magnetic stimulation, one MA organization based its internal coverage criteria on a Medicare LCD and added an additional requirement that providers demonstrate that the beneficiary has consented to the service. The other MA organization used internal coverage criteria for psychological testing that was developed by the contractor that manages its prior authorization process for behavioral health services.[52] Representatives from the MA organization and its contractor told us that it used these criteria because professional society criteria do not address all treatment circumstances.

Representatives of five provider organizations we spoke with expressed some frustrations with the way MA organizations apply criteria. For example, one provider representative said that requests for similar services may be denied by one plan and approved by another plan even though both use the same criteria. Another provider said that MA organizations tend to ask for detailed information that does not seem relevant to determining whether a service is necessary.

CMS Oversight Has Not Targeted MA Organizations’ Use of Internal Coverage Criteria to Authorize Behavioral Health Services

CMS has not targeted behavioral health services in its oversight of MA organization prior authorization, so CMS does not have enough information to know if MA organizations’ use of internal coverage criteria for behavioral health services affects MA beneficiary access to care.

CMS is responsible for ensuring that MA beneficiaries generally receive the same coverage of benefits as traditional Medicare beneficiaries through its oversight of MA organizations, including through periodic program audits. During its annual program audits, CMS assesses the application of criteria that MA organizations use to make coverage decisions by reviewing files associated with 30 denied prior authorization requests or payment denials.[53] The file reviews assess, among other things, whether the decision was made in accordance with established time frames, was made by an appropriate clinical reviewer, and whether the criteria used by the MA organization (including internal coverage criteria) were applied correctly. CMS officials said that these reviews do not assess whether any internal coverage criteria used were appropriate and supported by clinical evidence.

CMS officials told us that auditors have reviewed a small number of behavioral health services in program audits. They said that 2024 was the first year that CMS focused its file reviews on selected services, and CMS did not target any behavioral health services for review in 2024.[54] Officials said that CMS selected the seven services it targeted for review based on three criteria:

1. Feedback from stakeholders[55]

2. CMS’s internal analysis of services with high denial rates

3. Services that were most often subject to improper denials according to the 2022 HHS Office of Inspector General report about coverage denials[56]

CMS officials said auditors reviewed a small number of behavioral health denials in 2024, such as in cases when MA organizations reported fewer than 30 total denials for the targeted services. However, CMS officials told us that they have not reviewed enough behavioral health denials to identify patterns across MA organizations. CMS officials said that before the 2024 audits, auditors primarily selected denials for review that were likely to be inappropriate based on a review of data provided by MA organizations.[57] For example, a CMS official said that auditors may select a denied request for emergency care for review since MA organizations are required to cover this care without prior authorization. Officials noted that behavioral health services have not made up a large portion of the denials available for CMS review, but it would be possible for CMS to target these services in the future.

To complement its program audits, in September 2024, CMS announced a plan to annually collect and review information from MA organizations about the specific internal coverage criteria they use to authorize care.[58] In October 2024, CMS officials told us that these reviews will help them ensure that internal coverage criteria are developed only when appropriate and supported by evidence. Officials said the agency will use the results to correct MA organization noncompliance, revise Medicare coverage criteria, and inform future rulemaking.[59] Officials said that the reviews of MA organizations’ internal coverage criteria will complement program audits to ensure that MA organizations comply with all of CMS’s prior authorization requirements—the internal coverage criteria reviews will assess whether criteria are appropriate, and the program audits will assess whether MA organizations are applying these criteria correctly. However, CMS has not determined if behavioral health services will be included in these audits or when these reviews will begin. CMS announced in December 2024 that it plans to start the annual internal coverage criteria reviews in 2026 and will select up to 50 services for a high-level review and 20 of these services for a detailed review.[60] In March 2025, CMS officials told us that plans for these audits had not been finalized, including whether reviews would start in 2026 and how CMS would select services. CMS had not released any final plans as of May 2025.

Targeting behavioral health services in its program audits and in its planned reviews of internal coverage criteria would be consistent with CMS’s statement that addressing beneficiaries’ behavioral health needs is a key priority, and its Behavioral Health Strategy, which includes the goal of improving access to and quality of behavioral health care and services.[61] CMS has also stated that poor behavioral health outcomes are especially detrimental to older adults, and that older adults face significant barriers to accessing behavioral health services.[62] These reviews would help CMS determine whether or to what extent the use of internal coverage criteria hinders beneficiaries’ access to behavioral health services and whether additional oversight of such criteria is needed.

Selected MA Organizations Did Not Always Make Internal Coverage Criteria Accessible, but CMS Is Taking Steps to Improve Public Accessibility

Three Selected MA Organizations Did Not Make All Internal Coverage Criteria Accessible; CMS Identified Delays in Compliance and Will Conduct Further Audits

We could not locate the public internal coverage criteria that three of the nine selected MA organizations used for the five selected behavioral health services (see table 3). CMS required that MA organizations make internal coverage criteria publicly accessible beginning in 2024.

Table 3: Accessibility of Selected Medicare Advantage (MA) Organizations’ Internal Coverage Criteria for Five Selected Behavioral Health Services, 2024

|

Number of internal coverage criteria used for five services |

Accessibility of internal coverage criteria for five services |

|

|

MA organization 1 |

1 |

|

|

MA organization 2 |

3 |

◒ |

|

MA organization 3 |

3 |

|

|

MA organization 4 |

2 |

◒ |

|

MA organization 5 |

0 |

— |

|

MA organization 6 |

3 |

|

|

MA organization 7 |

0 |

— |

|

MA organization 8 |

2 |

|

|

MA organization 9 |

1 |

|

● = all internal coverage criteria accessible; ◒ = some internal coverage criteria accessible; ○ = no internal coverage criteria accessible; — = internal coverage criteria not used for any of the five services

Source: GAO analysis of information from selected MA organizations. | GAO‑25‑107342

Note: GAO reviewed internal coverage criteria website locations provided by selected MA organizations between August 2024 and December 2024. The counts show the number of internal coverage criteria each MA organization used for the selected behavioral health services. The five selected behavioral health services are: acute inpatient mental health, inpatient alcohol detoxification, opioid treatment programs, outpatient mental health visits, and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Some MA organizations used more than one internal coverage criteria for a single service.

When asked why internal coverage criteria were not publicly accessible, two of the three MA organizations provided reasons related to third-party developers. One MA organization said their contract with a third-party developer did not allow criteria to be made public.[63] Another MA organization said they were working with a third-party developer to make one of its internal coverage criteria publicly accessible as of December 2024, and it was accessible as of February 2025.

CMS officials identified two reasons some MA organizations did not post internal coverage criteria based on the agency’s 2024 program audits. First, CMS officials said MA organizations were not always aware that criteria developed by third-party developers were considered internal coverage criteria. Second, CMS officials said MA organizations did not realize they were using internal coverage criteria because they or their contractors had been supplementing traditional Medicare policies for many years, and MA organizations were often working with multiple vendors. As a result, according to CMS, it took additional time for these MA organizations to identify internal coverage criteria and make them publicly accessible.

CMS officials said MA organizations were coming into compliance with the requirements throughout 2024 as they learned from the agency’s 2024 frequently asked questions document and 2024 program audits.[64] CMS officials told us that MA organizations generally understood CMS’s expectations by the time the 2024 program audits started and had either made third-party developers’ criteria accessible or were actively working to do so.[65] In January 2025, CMS announced that it will continue to audit MA organizations’ compliance with these requirements in its 2025 program audits.[66]

Selected MA Organizations’ Internal Coverage Criteria Were Difficult to Locate and Did Not Always Contain Required Components; CMS Considered Improvements to Public Accessibility

Selected MA organizations’ publicly accessible internal coverage criteria were difficult to locate because they were not posted in prominent locations nor clearly identified, which may hinder public accessibility. For example, one MA organization posted the criteria within their website while most posted the criteria on third-party websites. One MA organization made its internal coverage criteria accessible through a webpage for individuals and families. Another MA organization made its behavioral health internal coverage criteria accessible through a webpage designated for learning about mental health and well-being. CMS officials said that they observed—through their 2024 program audits—wide variation in how MA organizations made internal coverage criteria publicly accessible and how difficult the criteria were to find. CMS officials told us they intentionally allowed flexibility during the first year of implementation in terms of how or where internal coverage criteria were to be posted.

As a result of the wide variation in location and difficulty finding the internal coverage criteria, CMS’s proposed rule for contract year 2026 included measures to improve public accessibility, such as requiring that any internal coverage criteria in use be clearly identified and labeled. The proposed rule would have required MA organizations to display a list of services that contains links to all internal coverage criteria in use. CMS also proposed that internal coverage criteria webpages be displayed in a prominent manner and clearly identified in the website footer.[67] In the final rule issued in April 2025, CMS did not finalize these proposed provisions and deferred its decision on whether to finalize these provisions of the proposed rule for subsequent rulemaking, as appropriate.[68]

In addition, the selected MA organizations in our review did not always state which publicly accessible internal coverage criteria were applicable to their MA plans. For example, one of the selected MA organizations made its internal coverage criteria accessible from its member login page, but it was unclear which criteria were specific to MA beneficiaries; the linked document included internal coverage criteria relevant for both MA plans and other types of plans, such as Medicaid plans. Additionally, two MA organizations provided a link to a third-party developer’s website containing many different behavioral health internal coverage criteria but did not specify which internal coverage criteria it used for MA plans.

When MA organizations’ internal coverage criteria were publicly accessible for the selected services, they did not always include all required components. In addition to the criteria in use, MA organizations must also make publicly accessible (1) a summary of evidence considered during the development of the criteria, (2) sources of the evidence, and (3) an explanation of the rationale that supports the adoption of the internal coverage criteria.[69] However, we found that none of the eight publicly accessible internal coverage criteria used by selected MA organizations contained all these components.[70] Two internal coverage criteria contained a summary of evidence; six contained the sources of evidence; and none included the required rationale.

None of the eight publicly accessible internal coverage criteria used by selected MA organizations included, as part of the rationale, an explanation about how the clinical benefits of using the internal coverage criteria likely outweighed the harms.[71] The MA organizations could not explain this gap. Representatives of three MA organizations responded with broad statements about their overall policy on supplementing CMS criteria with internal coverage criteria if needed, such as a brief statement that use of the criteria provides benefits that outweigh any harm. Representatives of one MA organization said their internal coverage criteria contained the required information. However, our review of the rationale did not find a detailed explanation of how the benefits of the criteria likely outweighed the potential harm. Representatives of two MA organizations said they planned to make information about their rationale for applying internal coverage criteria publicly accessible, but this information was not yet accessible as of December 2024.

As part of its proposed rule for contract year 2026, CMS proposed removing the requirement that internal coverage criteria contain an explanation of rationale showing how the clinical benefits of using the internal coverage criteria likely outweigh the harms. CMS proposed replacing it with a new requirement that the MA organization show how the internal coverage criteria support patient safety.[72] In the final rule issued in April 2025, CMS did not finalize these proposed provisions and deferred its decision on whether to finalize these provisions of the proposed rule for subsequent rulemaking, as appropriate.[73] CMS officials also told us that they plan to assess if MA organizations made required components publicly accessible more comprehensively in its upcoming reviews of internal coverage criteria. In March 2025, CMS officials told us that plans for these audits had not been finalized. CMS had not released any final plans as of May 2025.

Conclusions

CMS is responsible for ensuring that MA beneficiaries generally receive the same coverage of benefits as beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, and the agency asserts that access to behavioral health care is a key priority. An HHS Office of Inspector General review indicated that when MA organizations use non-Medicare criteria to make prior authorization decisions, access may be compromised. We found that most selected MA organizations reported using internal coverage criteria to approve or deny requests for care.

CMS has an opportunity to assess if use of internal coverage criteria hinders access to behavioral health services as a part of its upcoming program audits and planned reviews of internal coverage criteria. However, past program audits have not targeted behavioral health services, and it is unclear if these services will be targeted in either oversight effort moving forward. Until CMS’s efforts to oversee MA organizations’ use of criteria target behavioral health services, the agency lacks reasonable assurance that the use of internal coverage criteria does not compromise access to behavioral health care for the 33 million beneficiaries who rely on MA organizations for health coverage.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Administrator of CMS should target behavioral health services in its program audit reviews of prior authorization denials and planned reviews of internal coverage criteria. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix III, HHS neither agreed nor disagreed with the recommendation. However, in its written response, CMS stated that it cannot commit to targeting behavioral health services at this time in its program audits because these services make up a small percentage of MA services. HHS further stated its commitment to ensuring that high-quality behavioral health services and supports are accessible to Medicare beneficiaries but said that it is focusing its oversight on areas where CMS can improve care for the highest number of beneficiaries possible. CMS also noted that it will take the recommendation under advisement as it considers which services to review during audits in future years.

We recognize that behavioral health services comprise a small percentage of MA services. As we reported, 3 percent of MA beneficiaries received behavioral health services in 2023. However, CMS and others have acknowledged that the Medicare population faces significant barriers to accessing behavioral health services and that the consequences of not receiving these services can be quite serious. Further, CMS has asserted that improving access to behavioral health services is a key priority, and we have found it is important for agencies to align oversight efforts with agency priorities. As CMS considers which services to review during audits, targeting behavioral health services, as we recommended, would better position the agency to help ensure behavioral health services are accessible to MA beneficiaries and the agency’s oversight is aligned with its priorities.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at GordonLV@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Sincerely,

Leslie V. Gordon

Director, Health Care

This appendix provides details on prior authorization requirements for in-network behavioral health services by Medicare Advantage (MA) organizations. We analyzed plan benefit package data submitted by MA plans to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for the first quarter of 2024 about categories of services that may require prior authorization and enrollment data as of February 2024.[74] Our analysis included MA plans that were HMO, HMO with a point-of-service option, and PPO plans.[75] We included MA special needs plans, which provide care for beneficiaries in one of three classes of special needs, such as having a severe or chronic condition.[76]

CMS collects information from MA organizations about whether they may require authorization for certain categories of in-network services annually. This approach to data collection results in two limitations: (1) it is difficult to determine which specific services require prior authorization because these categories include multiple services, and (2) these data may overstate an MA organization’s actual prior authorization requirements because these data represent whether authorization may be required. MA organizations can opt to overreport their requirements if, for example, they are considering adding a prior authorization requirement soon. CMS officials noted beneficiaries can access information from MA organizations directly to understand service-specific prior authorization requirements.

We asked several selected MA organizations about cases in which their plan benefit package submission and authorization requirements as reported to us did not align. Two MA organizations told us that they did not require prior authorization for a service category that their submission indicated did require prior authorization. One of these MA organizations said that while their submission was incorrect, it reflects a more restrictive practice than their operations and therefore has no adverse beneficiary impact. One MA organization told us that they plan to remove the prior authorization indication from the given category in future data submissions. As such, the data presented represent the maximum number of beneficiaries who are subject to a prior authorization requirement.

We also assessed the reliability of the plan benefit and enrollment data by reviewing related documentation, interviewing knowledgeable officials, and checking for internal and external consistency for a subset of variables. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of this report.

Table 4: Number and Percentage of Medicare Advantage (MA) Plans Included in Analysis and Number and Percentage of MA Enrollees in These Plans, 2024

|

MA plan type |

MA plans |

MA enrollees as of February 2024 |

|||

|

Number |

Percent |

Number |

Percent |

||

|

Health maintenance organization (HMO) |

2,592 |

45 |

10,902,452 |

40 |

|

|

HMO Point-of-Service |

1,002 |

18 |

6,629,164 |

24 |

|

|

Local and Regional preferred provider organizations (PPO) |

2,105 |

37 |

9,763,767 |

36 |

|

|

Total MA plans |

5,699 |

100 |

27,295,383 |

100 |

|

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. | GAO‑25‑107342

Note: GAO’s analysis included 5,699 MA plans that were HMO plans, HMO point-of-service plans, and PPO plans, including special needs plans. The percent of plans and percent of MA beneficiaries are based on the total number of MA plans in the analysis and beneficiaries enrolled in these plans. Percentages may not add to 100 percent due to rounding.

Table 5: Percent of Medicare Advantage (MA) Enrollees That May Have Prior Authorization Requirements for Behavioral Health Care Service Categories, 2024

|

Service category |

Percent of all MA enrollees in plans that may have prior authorization requirement |

|

Acute inpatient hospitalization |

98 |

|

Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization |

94 |

|

Partial hospitalization |

91 |

|

Individual or group sessions for mental health specialty services |

85 |

|

Individual or group sessions for psychiatric services |

84 |

|

Individual or group sessions for outpatient substance abuse |

83 |

|

Opioid treatment program services |

87 |

|

All behavioral health service categoriesa |

80 |

|

No behavioral health service categoriesa |

1 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. | GAO‑25‑107342

Notes: GAO analyzed in-network authorization requirements for 5,699 MA plans that were HMO plans, HMO point-of-service plans, and PPO plans, including special needs plans.

aThese lines reflect the percentage of MA organizations that may require prior authorization for every service category listed above and those that do not require prior authorization for any of the categories.

Table 6: Percent of Medicare Advantage (MA) Enrollees in MA Organizations That May Have Prior Authorization Requirements for Behavioral Health Care Service Categories, by Plan Type, 2024

|

Service category |

HMOs |

HMO point-of-service plans |

PPOs |

|

Acute inpatient hospitalization |

99 |

98 |

99 |

|

Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization |

88 |

97 |

98 |

|

Partial hospitalization |

84 |

95 |

96 |

|

Individual or group sessions for mental health specialty services |

75 |

91 |

91 |

|

Individual or group sessions for psychiatric services |

73 |

90 |

91 |

|

Individual or group sessions for outpatient substance abuse |

72 |

89 |

90 |

|

Opioid treatment program services |

82 |

89 |

90 |

|

All behavioral health service categoriesa |

68 |

88 |

88 |

|

No behavioral health service categoriesa |

1 |

2 |

1 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. | GAO‑25‑107342

Notes: GAO analyzed in-network authorization requirements for HMO plans, HMO point-of-service plans, and PPO plans, including special needs plans. As of February 2024, 45 percent of MA enrollees were in HMOs, 18 percent were in HMO point-of service plans, and 37 percent were in PPOs.

aThese lines reflect the percentage of MA organizations that may require prior authorization for every service category listed above and those that do not require prior authorization for any of the categories.

Table 7: Percent of Medicare Advantage (MA) Enrollees in Special Needs Plans That May Have Prior Authorization Requirements for Behavioral Health Care Service Categories, 2024

|

Service category |

Chronic condition special needs plan |

Dual-eligible special needs plan |

Institutional special needs plan |

|

|

Acute inpatient hospitalization |

99 |

99 |

100 |

|

|

Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization |

99 |

96 |

100 |

|

|

Partial hospitalization |

98 |

94 |

97 |

|

|

Individual or group sessions for mental health specialty services |

96 |

90 |

78 |

|

|

Individual or group sessions for psychiatric services |

94 |

87 |

74 |

|

|

Individual or group sessions for outpatient substance abuse |

93 |

88 |

87 |

|

|

Opioid treatment program services |

95 |

90 |

88 |

|

|

All behavioral health service categoriesa |

92 |

85 |

73 |

|

|

No behavioral health service categoriesa |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services data. | GAO‑25‑107342

Notes: GAO’s analysis included 1,383 special needs plans. Of beneficiaries enrolled in special needs plans, 10 percent were in chronic condition plans, 88 percent were in dual-eligible plans, and 2 percent were in institutional plans. Percentages may not add to 100 percent due to rounding.

aThese lines reflect the percentage of MA

organizations that may require prior authorization for every service category

listed above and those that do not require prior authorization for any of the

categories.

Table 8: Percent of Medicare Advantage (MA) Enrollees That May Have Prior Authorization Requirements for Behavioral Health Care Service Categories, by Parent Organization Size, 2024

|

Service category |

Large parent organizations |

Medium parent organizations |

Small parent organizations |

|

Acute inpatient hospitalization |

100 |

97 |

98 |

|

Inpatient psychiatric hospitalization |

93 |

94 |

95 |

|

Partial hospitalization |

91 |

92 |

90 |

|

Individual or group sessions for mental health specialty services |

93 |

84 |

68 |

|