BORDER SECURITY

DHS Needs to Better Plan for and Oversee Future Facilities for Short-term Custody

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Travis J. Masters at MastersT@gao.gov and Rebecca Gambler at GamblerR@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107346, a report to congressional requesters

DHS Needs to Better Plan for and Oversee Future Facilities for Short-term Custody

Why GAO Did This Study

CBP relied on contracts to operate and maintain soft-sided facilities (SSF). These facilities provide support and services when additional processing and holding capacity is needed for individuals apprehended along the southwest border. DHS also received funding to construct Joint Processing Centers (JPC)—permanent facilities that DHS expects will be more cost-effective than SSFs in the future.

GAO was asked to review CBP’s and DHS’s use and oversight of SSFs and JPCs. This report examines, among other things, (1) how CBP used contracts to support its SSF needs, and (2) the extent to which CBP and DHS engaged in planning efforts for SSF and JPC related acquisitions.

GAO analyzed contracting data on SSF contract obligations for fiscal years 2019-2024, and reviewed DHS budget plans, acquisition policies, and cost estimates for SSFs and JPCs. GAO also visited four selected SSF locations in Yuma and Tucson, AZ, El Paso, TX, and San Diego, CA based in part on apprehension and cost data; reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of eight of 69 contracts for SSFs and JPC construction contract documents; and interviewed DHS and CBP officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making six recommendations, including that CBP identifies and documents lessons learned from its SSF acquisitions; and that DHS documents its process for identifying future JPC locations and completes a life-cycle cost estimate for the Laredo JPC. DHS concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

Between 2019 and 2024, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)—a component of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—experienced a significant increase in the number of individuals apprehended by U.S. Border Patrol along the southwest border. To address this issue, CBP used temporary soft-sided facilities—steel-framed tent-like structures—to provide additional capacity for processing and holding people in its custody.

Because they are temporary, the number of facilities can change due to trends in the number of people apprehended. In September 2024, CBP had seven soft-sided facilities with different capacities—from 983 to 2,500. In March 2025, CBP ceased operating these facilities due to a significant drop in apprehensions.

CBP obligated over $4 billion total from 2019 through 2024 for soft-sided facilities and related services. But CBP engaged in limited acquisition planning to inform its investments in these facilities. For example, CBP did not take steps to accurately determine the number of contractor staff it needed to operate those facilities. As a result, some locations had either too few or too many staff. While CBP is not currently operating soft-sides facilities, it is likely to do so in the future if there are future surges in apprehensions, according to officials. Thus, CBP has an opportunity to identify and document lessons learned to better inform future investment decisions for these facilities.

In fiscal year 2022, Congress appropriated $330 million to DHS to develop and construct Joint Processing Centers. DHS plans to build and operate up to five of these facilities along the southwest border, which GAO estimates could cost roughly $7 billion. While DHS engaged in some initial planning to acquire Joint Processing Centers, officials did not complete key acquisition planning and oversight steps that leading practices suggest are key to inform large-dollar investments. For example, DHS began construction on the Laredo, Texas Joint Processing Center in October 2024 without reliable and complete operations and cost information. Further, it has not fully documented requirements and criteria for determining its Joint Processing Center locations. Documenting its process for identifying future Joint Processing Center locations and completing a life-cycle cost estimate would ensure that DHS is managing billions of dollars of mission critical services efficiently and effectively.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

CBP |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection |

|

COR |

contracting officer’s representative |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

FAR |

Federal Acquisition Regulation |

|

JPC |

Joint Processing Center |

|

SSF |

soft-sided facility |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 2, 2025

The Honorable James Lankford

Chairman

Subcommittee on Border Management, Federal Workforce, and Regulatory Affairs

Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Chris Murphy

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Homeland Security

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

Between 2019 and 2024, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) experienced a significant increase in the number of individuals apprehended between U.S. ports of entry along the southwest border. The increase in apprehensions by U.S. Border Patrol resulted in overcrowding and difficult humanitarian conditions in CBP short-term processing and holding facilities.[1] To address this issue, CBP began using temporary soft-sided facilities (SSF) in 2019 to provide additional processing and holding capacity for individuals apprehended along the southwest border. Between fiscal years 2019 and 2024, CBP awarded nearly 70 contracts, cumulatively valued at over $4 billion, for SSF mobilization and SSF operations.[2]

CBP’s SSFs are steel-framed tent-like structures with multiple rooms and sections and include services and equipment to temporarily hold and care for apprehended individuals. CBP relies on contracts to operate and maintain the SSFs and provide necessary support and services. These include armed and unarmed guards, child caregivers, food, and porters who move items within the facilities, such as apprehended individuals’ personal property.[3] Because they are temporary, the number of SSFs can change based on trends in apprehensions. As of September 2024, CBP had seven SSFs with different capacities – from 983 to 2,500.[4] Some of the seven SSFs became operational in 2021, while others became operational in 2023. In response to a significant drop in apprehensions, as of March 2025, CBP chose not to extend the term of its SSF contracts and is no longer operating any SSFs.[5] However, CBP officials told us that they anticipate using SSFs again in the future if apprehensions surge.

We previously reported on issues with CBP’s management of SSFs along the southwest border. In March 2020, we found that during the 5-month period between 2019 and early 2020 in which a facility in Tornillo, Texas, was operational, CBP paid approximately $66 million for the facility services.[6] CBP also leveraged significant federal personnel resources that could have been used elsewhere, despite holding an average of 30 individuals per day—about 1 percent of the facility’s capacity. We also identified concerns with how CBP managed the acquisition and its use of resources at the Tornillo SSF. These included how CBP offices and components shared information about the number of individuals at the facility and the costs of services being provided. For example, we found CBP spent $5.3 million on food service it did not need.

In response to previous apprehension surges, DHS also developed plans to construct Joint Processing Centers (JPC) along the southwest border. In fiscal year 2022, DHS received funding to construct JPCs, which DHS expects will co-locate relevant government stakeholders into a single permanent facility to streamline processing, enhance coordination, and minimize time in custody for apprehended individuals.[7] These JPCs, once constructed, are expected to provide additional processing and holding capacity beyond what would be available through SSFs and Border Patrol stations. DHS awarded a contract in April 2024 for the design and construction of the first JPC—a 1,000-person facility in Laredo, Texas—and broke ground in October 2024. DHS expects the Laredo JPC to become operational in early 2027 and plans to award contracts for services to maintain and operate the JPC, similar to those used at SSFs.

You asked us to review CBP and DHS’s use and oversight of SSFs and JPCs for individuals apprehended at the southwest border. This report examines (1) how CBP used contracts to support its SSF needs; (2) the extent to which CBP and DHS engaged in planning efforts to acquire SSF services and JPCs; and (3) the extent to which CBP provided oversight of performance of SSF contractors.

To determine how CBP used contracts to support its SSFs, we reviewed information from Border Patrol and CBP and identified 69 contracts related to SSFs. We analyzed contract obligation data associated with these contracts from the Federal Procurement Data System, a government-wide system for reporting contract data, for fiscal years 2019 through 2024.[8] We assessed the reliability of the data from the Federal Procurement Data System and concluded the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of compiling and assessing obligations related to SSF operations.

To assess CBP and DHS’s planning efforts for SSFs and JPCs, we conducted site visits to four SSF locations to observe contract performance and oversight activities. The sites were Yuma and Tucson, AZ; El Paso, TX; and San Diego, CA. We selected these sites using criteria such as apprehension rate changes, the number of individuals in custody at the Border Patrol sector, and estimated operating costs. We also selected and reviewed a nongeneralizable sample of eight contracts active at the time of our review out of the 69 total contracts CBP identified related to SSFs.[9] These eight contracts included three orders for key service categories used to support SSFs.[10] They also included five orders used to mobilize and operate our selected SSFs and provide wraparound services. These are services provided by the contractor managing the SSF structure, such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning; electricity; meals; and security.[11] All eight contracts we reviewed were also from our four selected SSF locations.

Also, as part of our second objective, we reviewed staffing and operational requirements across our eight selected contracts. We analyzed documents such as DHS budget and expenditure plans and other planning documents. We also assessed CBP’s estimated and actual SSF contracting costs that CBP reported to us for fiscal years 2021 through 2024.[12] In addition, we reviewed planning documentation including DHS cost estimates, and obligations reported in the Federal Procurement Data System for constructing the first JPC. We interviewed officials from DHS headquarters, CBP, and Border Patrol involved in acquiring and managing SSF services and JPCs. We assessed DHS and CBP’s planning efforts against our acquisition and cost estimating leading practices, some of which are reflected in DHS and CBP acquisition policy; Project Management Institute principles; and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[13]

To determine the extent to which CBP provided oversight of contractor performance at SSFs, we reviewed contract file documents related to CBP oversight for our selected contracts. We also assessed the extent to which CBP’s contract oversight at SSFs aligned with DHS guidance and Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.[14] Further, we interviewed CBP and Border Patrol officials involved in overseeing contractor performance at the temporary facilities, as well as contractor staff performing work on our selected contracts.

Appendix I provides more information on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

CBP Processing of Apprehended Individuals at the Southwest Border

CBP is the lead federal agency charged with, among other things, detecting and apprehending individuals unlawfully entering or exiting the United States.[15] Within CBP, Border Patrol is responsible for patrolling the areas between ports of entry to prevent people and goods from entering the U.S. illegally. Border Patrol divides responsibility for southwest border security operations geographically among nine sectors, each with its own sector headquarters:

· San Diego;

· El Centro;

· Yuma;

· Tucson;

· El Paso;

· Big Bend;

· Del Rio;

· Laredo; and

· Rio Grande Valley.

After making an apprehension, Border Patrol may hold individuals in short-term custody—typically no longer than 72 hours. Border Patrol retains custody of individuals at short-term holding facilities to complete processing and determine the next appropriate course of action. Such actions could include a transfer of custody to another agency, such as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement for long-term detention; removal from the U.S.; permission to voluntarily return to their home country; or conditional release within the U.S. pending the outcome of removal proceedings.

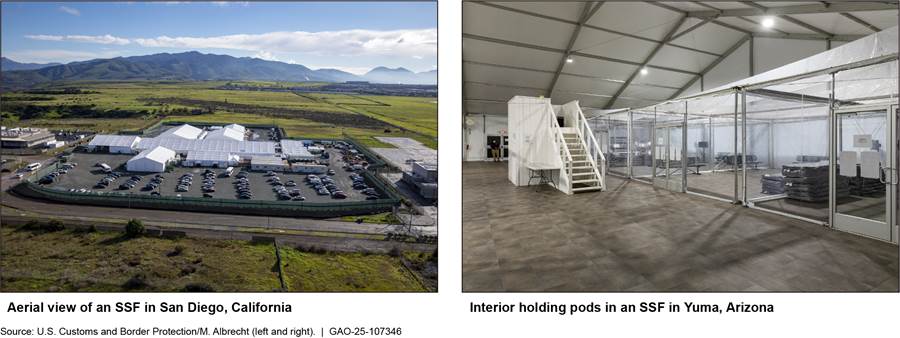

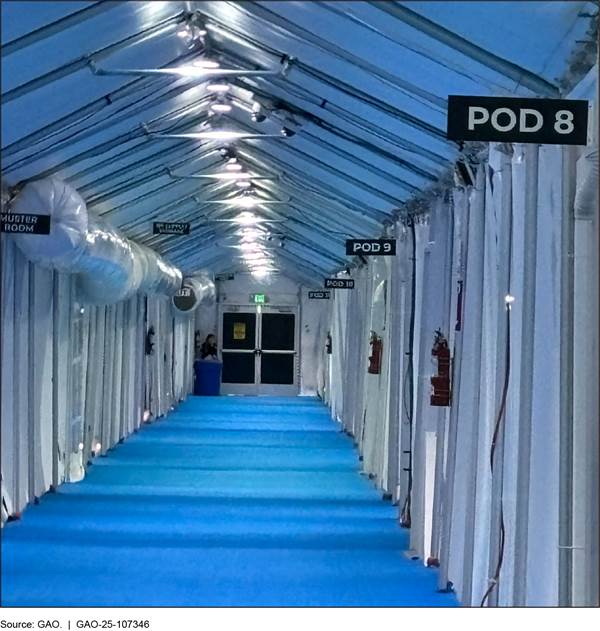

Prior to 2018, Border Patrol relied on permanent facilities such as Border Patrol stations to meet its short-term custody needs. Beginning in late 2018, Border Patrol apprehensions increased significantly along the southwest border, from around 850,000 in fiscal year 2019 to a peak of over 2 million in fiscal year 2022, according to CBP data.[16] This resulted in overcrowding and difficult humanitarian conditions in Border Patrol short-term processing and holding facilities. To address this issue, Border Patrol determined it needed temporary SSFs to provide additional capacity for the influx of individuals and families entering the U.S. See figure 1 for an exterior and interior view of an SSF.

The number and location of SSFs has changed in response to trends in apprehensions. For example, many of the SSFs mobilized in fiscal year 2019 were demobilized during the COVID-19 pandemic, as apprehensions significantly decreased during this period.[17] CBP mobilized SSFs again in early 2021, and, during our review, CBP operated seven SSFs across Border Patrol sectors. Table 1 identifies the SSFs that were operational between February 2021 and March 2025.

Table 1: Details on U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Soft-Sided Facilities (SSF) That Were Operational Between February 2021 and March 2025

|

Border Patrol sector |

Location |

Capacity |

Operational dates |

Duration operational |

|

Rio Grande Valley |

Donna, TXa |

1,000 -1,625 |

February 2021 to March 2025 |

49 months |

|

Laredo |

Laredo, TX |

983 |

September 2021 to March 2025 |

42 months |

|

Del Rio |

Eagle Pass, TX |

1,125 |

May 2022 to March 2025 |

34 months |

|

El Paso |

El Paso, TXb |

1,000 - 3,500 |

January 2023 to March 2025c |

26 months |

|

Tucson |

Tucson, AZ |

1,000 |

April 2021 to March 2025 |

47 months |

|

Yuma |

Yuma, AZ |

1,375 |

April 2021 to March 2025 |

47 months |

|

San Diego |

San Diego, CA |

1,000 |

January 2023 to March 2025 |

26 months |

Source: GAO analysis of CBP documents and interviews. | GAO‑25‑107346

Note: CBP demobilized all of its SSFs in fiscal year 2020 due to COVID-19.

aTwo sections of the Donna SSF, with a combined capacity of 1,000 people, became operational in February 2021. CBP added a third section with an additional 625-person capacity to the Donna SSF in May 2021 and later demobilized this section in September 2022. The third section was mobilized again in December 2022 and demobilized in May 2024. The third section was operational for 16 and 17 months, respectively.

bCBP mobilized a 1,000-person SSF in El Paso in January 2023 and later added an additional SSF that held 2,500 people. CBP demobilized the initial 1,000-person SSF in May 2024.

cIn March 2025, the Department of Homeland Security chose not to exercise the next option period for the El Paso SSF and the contract expired on March 29, 2025. The El Paso facility remains operational, however, under a new contract awarded by the U.S. Army to the incumbent contractor, in support of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement operations.

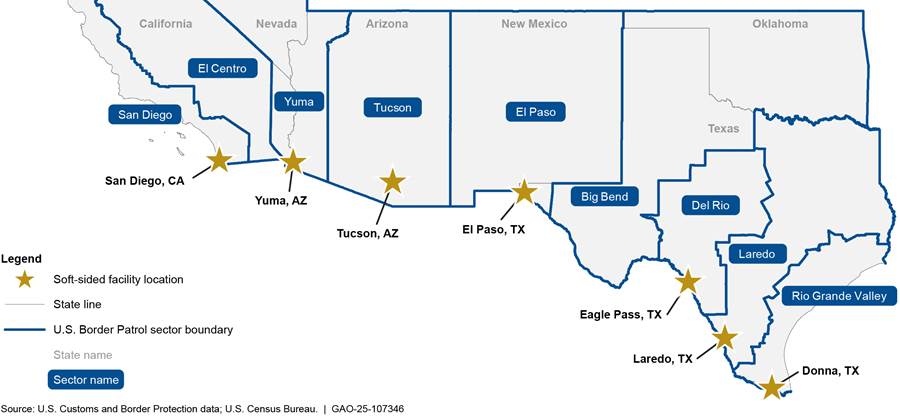

Figure 2 depicts on a map the SSFs that were operational between February 2021 and March 2025.

Figure 2: Locations of U.S. Customs and Border Protection Soft-Sided Facilities Between February 2021 and March 2025

In addition to using SSFs to process and hold apprehended individuals, in fiscal year 2022, DHS received $330 million in appropriations to develop JPCs—permanent structures the department intended to supplement SSFs along the southwest border. As of April 2025, DHS planned to build up to five JPCs to be used by multiple agencies involved in holding and processing apprehended individuals. DHS anticipates this approach will be more cost effective than SSFs.

DHS Policies Guiding SSF Design and Operational Requirements

DHS has policies and guidance on its identification of requirements to fulfill its mission. The requirement’s identification process generally starts with the identification of a need or an operational gap that can be met through either a contract or an acquisition program, depending on the requirement and cost. For example, contract requirements are typically identified and developed through market research and acquisition planning and finalized in a document, like a statement of work. DHS acquisition policy also provides a framework for larger investments that meet certain dollar thresholds. These acquisitions can include large-dollar capital investments in IT or construction, or service acquisition programs—which begin the requirements development process by identifying mission needs and broad capability gaps that then inform the operational requirements the end users need to conduct their mission.

According to officials, requirements for CBP facilities used for short-term processing and holding are based on national standards and relevant laws and regulations that establish standards for the short-term custody of individuals held by CBP components.[18] In addition to these broad standards, CBP must follow other requirements related to holding certain populations, such as children.[19] Further, in the Tucson sector, there are some additional requirements at CBP holding facilities, such as SSFs, as a result of litigation. Specifically, these holding facilities are required to provide items for certain basic needs—such as a raised bed and shower—to individuals for whom CBP has completed processing and whose time in detention at Tucson sector CBP facilities exceeds 48 hours.[20]

CBP contracts for a variety of services to facilitate short-term custody and care of apprehended individuals in accordance with specific standards of care. At SSFs, these services generally fall into two broad categories. The first is wraparound services, which refer to goods and services provided by the contractor managing the structure that make it turnkey. For SSFs, this would include services such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning; electricity; water; and meals. The second category is other services, which refer to contracted services that support facility operations.[21] Table 2 provides additional details on wraparound and other supporting services.

Table 2: Examples of Services Provided in Soft-Sided Facility (SSF) Wraparound and Other SSF Service Contracts

|

Service |

Description |

|

|

|

Wraparound services |

· Developing site plans · Preparing the site for the SSF · Providing and assembling the SSF · Maintaining the SSF · Installing sinks, toilets, showers, and phone booths · Providing furniture |

· Providing beds and blankets · Cleaning the SSF · Installing and maintaining heating, ventilation, and air conditioning; electrical power; and generators (with fuel) · Providing potable water and wastewater |

· Supplying meals and snacks for individuals at the SSF · Laundering clothes · Moving property and items around the facility · Securing entrances and exits with unarmed guards |

|

Other SSF |

· Armed guards for performing security duties on-site and assisting with transportation · Data processing, such as assisting Border Patrol agents who are conducting interviews with apprehended individuals and inputting information into databases |

· Caregivers, who provide supervision of children and direct care for any unaccompanied children · Medical services with medical staff conducting medical intake evaluations, health screenings, and performing certain on-site care |

· Transportation, including supplying buses, vans, and personnel to drive vehicles, and providing personnel for flights to transport individuals to facilities within or between sectors |

Source: GAO analysis of U.S. Customs and Border Protection contracts and interviews. | GAO‑25‑107346

aThese support services may be provided through contracts used across multiple types of facilities.

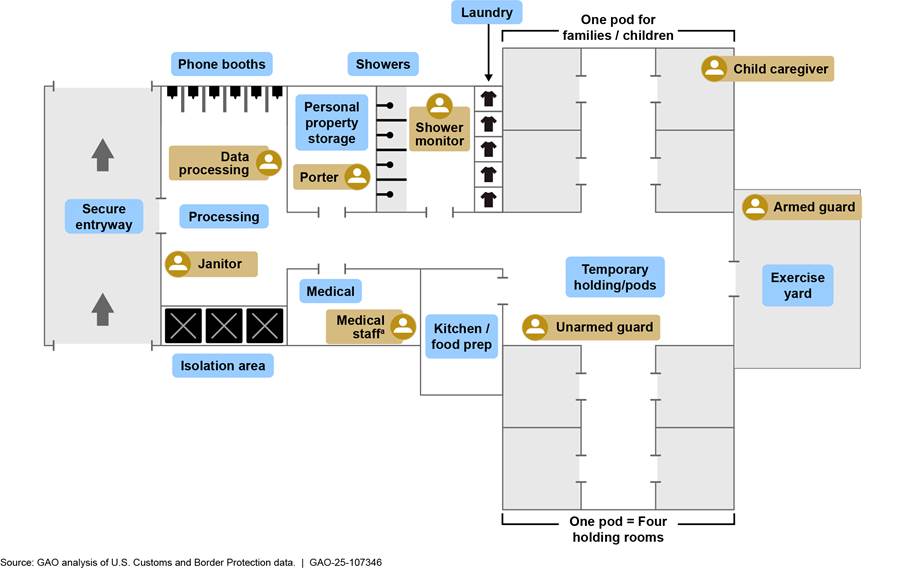

While individual SSFs can vary in size and configuration, there are common structural elements and operational processes, as shown in figure 3.

aAccording to senior CBP officials, medical staff may include a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, among others. Officials noted that on-site medical staff does not include doctors.

Offices and Personnel Involved in Contracting and Oversight for SSFs and JPCs

Numerous offices throughout DHS, CBP, and Border Patrol play a role in SSF and JPC contracting, management, and oversight. Table 3 shows the key offices within CBP involved with managing SSFs, several of which are also involved in efforts to construct and operate JPCs.

Table 3: Key U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Offices Involved with Soft-Sided Facilities (SSF)

|

Office |

Description of responsibilities related to SSFs |

|

CBP Office of Acquisition |

Procured goods and services through its contracting officers, such as the temporary SSFs and associated support services. |

|

CBP Office of Facilities and Asset Management |

Determined facility design requirements and managed facility goods and services procured for SSF wraparound service contracts. |

|

U.S. Border Patrol Law Enforcement Operations Directorate |

Established operational requirements, and oversaw and managed, in coordination with the Office of Facilities and Asset Management, the daily operations and contractor staffing levels at SSFs and managed some of the support services contracts at SSFs.a |

|

CBP Office of the Chief Medical Officer |

Managed the medical service and child caregiving services contracts that operate at SSFs. The Office of the Chief Medical Officer is the medical and health advisory office for CBP and is responsible for consistent, safe, and effective health and medical support. |

Source: GAO analysis of CBP documents and interviews. | GAO‑25‑107346

aFor instance, the Law Enforcement Operations Directorate managed the armed guards, data processing, and transportation contracts used at SSFs.

We previously reported that management and oversight of contracts is essential to ensuring the government receives the goods and services it has contracted for.[22] Contract oversight is largely the responsibility of the contracting officer and the contracting officer’s representative (COR) designated to a particular contract. At DHS, contracting officers may also appoint technical monitors to assist in contract oversight. Contracting officers, CORs, and technical monitors all have roles in contract oversight, as detailed below.

· Contracting officers. The contracting officer has authority to enter into, administer, and terminate contracts and make related determinations. The contracting officer also has the overall responsibility for ensuring the contractor complies with the terms of the contract. As part of their responsibilities, contracting officers may delegate certain oversight responsibilities to a COR, such as reviewing contractor invoices.

· CORs. CORs assist in the monitoring and day-to-day administration of a contract. They are often selected based on their knowledge of the program and are to be certified and receive training on their oversight duties.[23] Per DHS policy, a contracting officer typically must designate a COR to every contract that is above the simplified acquisition threshold, which is generally $250,000.[24] CORs do not have the authority to make any commitments or changes that affect price, quality, quantity, delivery, or other terms and conditions of the contract.

· Technical monitors. According to DHS policy, in addition to a COR, a contracting officer may appoint a technical monitor to assist with oversight.[25] These officials work with the COR to perform contract oversight including monitoring, surveillance, and quality assurance, typically in a very specific area.

Many of the same offices and personnel involved in planning, managing, and overseeing SSFs have been involved in DHS’s effort to construct and operate JPCs. In January 2022, DHS established a JPC Task Force—in coordination with CBP’s Office of Facilities and Asset Management and Border Patrol’s Law Enforcement Operations Directorate—to develop requirements and lead the integrated effort to plan, design, build, and operate JPCs along the southwest border.[26]

CBP Increasingly Used Contracts to Support Soft-Sided Facility Needs

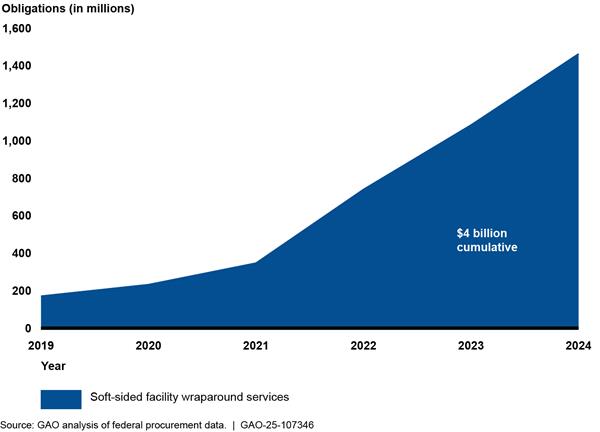

CBP increasingly relied on contracts to support mobilizing and operating SSFs along the southwest border from fiscal years 2019 through 2024, with obligations increasing every year during that period. Based on our analysis of federal procurement data, CBP obligations on SSF wraparound service contracts increased from about $170 million in fiscal year 2019 to $1.4 billion in fiscal year 2024.[27] CBP’s fiscal year 2024 SSF wraparound service obligations constituted about 25 percent of CBP’s total annual agencywide contract obligations and equated to about $4 million in obligations for SSFs per day in fiscal year 2024. Most of CBP’s total SSF contract obligations from fiscal years 2019 through 2024 were on contracts for SSF wraparound services, accounting for around $4 billion (see fig. 4).

Figure 4: U.S. Customs and Border Protection Soft-Sided Facility Wraparound Services Contract Obligations, Fiscal Years 2019-2024

Note: “Wraparound services” is an informal term that U.S. Customs and Border Protection uses to refer to soft-sided facilities and other items or services that make the facility turnkey, such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning; electricity; meals; and security. For this report, GAO defines “wraparound” as the goods and services provided by the contractor managing the soft-sided facility structure.

CBP’s contract obligations for other services that support short-term detention operations at various CBP facilities, including SSFs, also increased each year. These services include medical care, armed guards, caregiving, data processing, and transportation. Based on our analysis of federal procurement data, CBP obligations for these other services accounted for up to $1.8 billion in additional obligations from fiscal years 2019 through 2024, with medical services accounting for about half of those obligations. However, obligations for these other support services were not always specific to SSFs because these contracts can cover larger geographic areas and additional facilities, like Border Patrol stations.[28] For example, the contract to provide caregivers at detention facilities along the southwest border includes SSFs as well as permanent facilities.

Changes in the number of apprehensions along the southwest border resulted in increased obligations for operating SSFs. Between fiscal years 2019 and 2024, CBP increased the number of SSFs it used in response to higher numbers of apprehensions along the southwest border, which resulted in increased contract obligations for the facilities. Specifically, from fiscal years 2019-2020, CBP operated four SSFs, which were later all demobilized in fiscal year 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic as apprehensions significantly decreased during this period. Then, CBP mobilized four SSFs in fiscal year 2021, after holding policies from COVID-19 expired and as apprehensions increased. By 2024, CBP was operating up to seven SSFs.[29]

Additionally, since 2021, CBP expanded the capacity of most of the existing SSFs, increasing the obligations for those facilities. For instance, officials from the Tucson sector explained that, when their current SSF became operational in April 2021, it held 500 people, but they expanded it in September 2023 by adding capacity for 500 more people in response to increases in apprehensions in the sector. Officials in the Yuma sector also explained that they expanded their SSF twice to increase capacity because of increased apprehensions since the SSF became operational in April 2021. In addition to costs associated with expanding SSFs, SSF operational costs may increase during times of higher apprehensions because CBP paid the contractor an overcapacity fee when the number of people held in the SSF exceeded the SSF’s defined capacity.[30] Figure 5 shows an example of the most recent expansion at Yuma’s SSF.

Figure 5: Interior Hallway of the Most Recent Soft-Sided Facility Expansion in Yuma, Arizona (April 2024)

CBP officials told us they relied on contractors to perform services needed to operate SSFs because it gave the agency more flexibility and freed Border Patrol agents to perform their primary mission of patrolling the border. However, Border Patrol officials told us that in cases when there were not sufficient contracted personnel to operate an SSF, agents were reassigned from their primary responsibilities to fill roles for operating the SSFs, such as distributing food, monitoring showers, and providing care for infants. For example, in April 2024, officials in Tucson said they had around 230 Border Patrol agents on-site at the SSF performing administrative and operational functions such as processing and caring for apprehended individuals and coordinating transportation. Senior Border Patrol officials said that ideally, contractor staff would have performed many types of support functions needed to operate an SSF.

DHS Has Not Assessed Soft-Sided Facility Lessons Learned or Completed Key Joint Processing Center Planning and Analyses

CBP has made significant investments in SSFs over the past 6 years but has not assessed or documented lessons learned in key areas, though agency officials said that they are likely to use SSFs again in the future, should apprehensions surge. While CBP officials told us they conducted some planning as part of a working group to refine processes and internal coordination, we found that CBP did not conduct key planning and analyses related to determining SSF staffing requirements, operational status, and costs, which led to inefficiencies in these areas. Similarly, we found that DHS is not following leading practices to guide its decision-making related to JPCs. These leading practices would include (1) conducting key planning and analysis steps to inform development of JPCs; (2) fully analyzing requirements for JPC locations; and (3) fully estimating all costs for the initial JPC. Without following leading practices, DHS faces the risk that its JPC acquisitions could encounter inefficiencies similar to those it experienced with SSFs.

CBP Has Not Assessed Lessons Learned From Its Soft-Sided Facility Investments

SSFs have played a critical role in CBP’s ability to respond to increases and fluctuations in apprehensions since 2019, and CBP previously incorporated some lessons learned into planning its SSF contracting. While CBP no longer operated any SSFs as of March 2025, we identified areas where CBP could benefit from identifying lessons learned from its use of SSFs. This could, in turn, help inform CBP’s use of temporary facilities in the future.

According to leading practices that we and others have identified for both program and project management, which are also reflected in DHS policy, it is important to identify and apply lessons learned from programs, projects, and missions to limit the chance of recurrence of previous failures or difficulties.[31] Although CBP recently ceased operating SSFs, the facilities remain an option for CBP to use if future apprehensions surge. Based on our analysis, there are at least three areas where CBP could identify lessons learned for SSFs: (1) staffing requirements, (2) operational requirements, and (3) cost.

Staffing requirements. Across the contracts for SSF services that we reviewed, we found that CBP determined SSF contractor staffing requirements—the number of contractor personnel needed for each service type—without a standard methodology. This resulted in situations where there were too few or too many contractor staff on-site than were needed for facility operations. According to CBP officials, several CBP stakeholders, including the Office of Facilities and Asset Management, the Office of the Chief Medical Officer, Border Patrol’s Law Enforcement Operations Directorate, and sector-level officials were involved in defining contractor staffing requirements for each SSF, based on a variety of factors such as size, capacity, and layout of the facility. For example, Office of Facilities and Asset Management officials responsible for SSF wraparound services said they identified the initial number of required unarmed guards per SSF based on the SSF layout and number of external doors. CBP Office of the Chief Medical Officer officials responsible for managing the contract for caregivers also told us that they considered several factors in determining the required number of contractor staff to be caregivers at an SSF, such as if the demographics include children and the number of people in custody. These officials added that the availability of funding was also a significant factor in setting staffing requirements for caregivers at SSFs.

While there were various factors involved in setting contractor staffing requirements, some SSFs we visited had fewer contractor staff on-site than sector officials said they needed, which affected Border Patrol operations at those facilities. In particular, Tucson SSF officials told us the staffing requirement for data processing staff in their contract was lower than what they needed for their operations, and Yuma SSF officials told us the staffing requirement for caregivers in their contract was also too low.[32] Officials explained that to address these shortfalls, Border Patrol agents were performing data processing responsibilities in Tucson and monitoring showers in Yuma, thus keeping these agents from performing other activities like patrolling the border.

CBP also identified instances where it had more contracted staff providing services at SSFs than needed. For example, CBP officials told us they had initially used their judgment on a case-by-case basis to identify staffing requirements for the types of contracted services needed at each SSF to respond to surges in apprehensions. These included porters, who are contractor staff responsible for moving supplies and managing individuals’ personal property, among other things. However, during our review, we found that staffing levels for contractor personnel sometimes varied across SSF locations despite facilities having the same capacity.

After we raised questions on overall SSF staffing requirements during our review, CBP reported it reassessed its method for determining staffing requirements for porters and developed a standardized formula to apply across the SSFs. In August and September 2024, CBP implemented the new formula for porter staffing at four SSFs, resulting in a reduction of 81 porters per shift and a cost savings of nearly $2.7 million per month, according to CBP officials. Based on the estimated monthly savings for each contract using the porter formula, we calculated that CBP saved nearly $18 million from August 2024 through March 2025.

During our review, CBP officials said they intended to develop and document formulas to determine staffing requirements for other contracted wraparound and support services for SSFs, such as armed and unarmed guards, but had not done so by the time they ceased operations at all SSFs in March 2025. Because CBP officials expect to use SSFs again in the future, should they be needed to respond to surges in apprehensions, developing and documenting staffing formulas as part of an assessment of lessons learned could benefit future decisions.

Operational requirements. Based on our prior work, CBP added flexibilities to its SSF contracts that allow for changes in operational requirements, or the operational status of an SSF, in response to fluctuations in apprehension trends.[33] However, CBP did not establish standardized criteria for when, or under what circumstances, it would modify an SSF’s operational status, which resulted in CBP spending more on SSF operations than needed in some instances.

Specifically, CBP identified tiers of operational status that allow it to limit or stop operations in part or all of an existing SSF—called warm and mothball status.[34] In warm status, most contractor staff would remain on site and may be reassigned to other duties, but no one is processed or held in the space. Because fewer services are needed in warm status, the cost to CBP is lower. In mothball status, the SSF is not operational, and the contracted staff are laid off or transferred to another facility.[35] Due to the stoppage in services needed, mothball status is the lowest cost operational status for CBP.

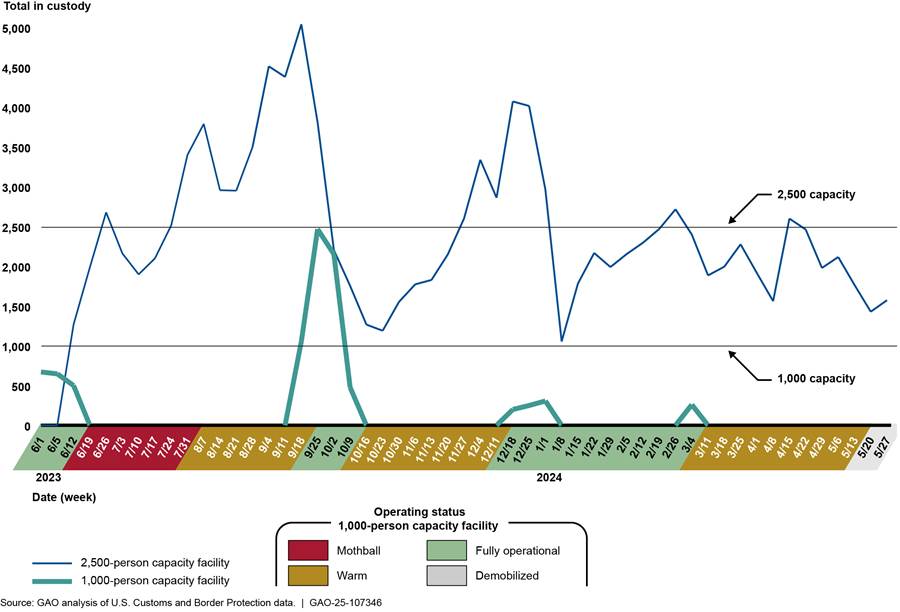

Having the ability to modify operational status provides CBP with flexibility to respond to changing needs, which can save CBP money. However, we found that without any established criteria, Border Patrol made operational status changes that resulted in CBP spending more on SSF operations than needed. For example, during our review, CBP had two SSFs in the El Paso sector—one with a capacity of 2,500 and the other with a capacity of 1,000. In response to increases in custody levels, in August 2023, CBP changed the operational status of the 1,000-person facility from mothball to warm status—opening and staffing the facility but not holding people in it—at a cost of $3.4 million. At the same time, CBP paid about $5 million in overcapacity fees at its 2,500-person SSF due to overcrowding at that facility.[36] Based on our analysis of CBP documents, we found that CBP could have avoided at least some of the $5 million in overcapacity charges and alleviated some overcrowding if it had instead paid an additional $1.1 million to make the 1,000-person facility fully operational instead of simply placing it in warm status.

In another instance, in December 2023, CBP moved the 1,000-person El Paso facility from warm status to fully operational and kept it in that status for nearly 3 months, despite holding an average of 84 people per day in the facility—and 8 consecutive weeks with zero individuals in custody. CBP officials told us they frequently used the 1,000-person facility as a staging point for apprehended individuals moving out of the larger 2,500-person facility. However, this does not explain why they kept the 1,000-person facility in fully operational status, given the challenges officials cited with having enough Border Patrol staff to maintain both facilities and low numbers of individuals in custody at that time. Figure 6 shows changes in custody levels and operational status over time for SSFs in El Paso.

Figure 6: Custody Levels of the Two Soft-Sided Facilities and Operational Status Changes of the 1,000-Person Soft-Sided Facility in El Paso, Texas from June 2023 to May 2024

In May 2024, CBP demobilized the 1,000-person facility. Based on our analysis, we found that the 1,000-person SSF was in a non-operational status—mothball or warm—64 percent of the time in the year before CBP demobilized it and often held significantly fewer people than its capacity. For example, the 1,000-person SSF held 32 people per day on average in the 7 months prior to its demobilization. Figure 7 shows workers demobilizing the 1,000-person SSF in June 2024.

The DHS Office of the Inspector General identified related concerns in its August 2023 report. Specifically, the Inspector General found that CBP officials did not regularly reassess whether to maintain or demobilize SSFs and did not assess the cost-effectiveness of maintaining SSFs in response to changes in apprehension trends.[37] The Inspector General recommended that CBP establish a policy to consistently document and use all available information to make informed facility planning decisions, assess alternative options to temporary facilities, and regularly reassess the continued need for existing temporary facilities, among other things.

In response to this recommendation, CBP officials told us they formed a Facility Planning Working Group, led by the Office of Facilities and Asset Management, that included key SSF stakeholders to refine SSF planning and develop a new policy. Officials told us that they anticipate the policy will provide additional information, such as the costs and savings of different operational statuses and custody data trends. This could assist Border Patrol in determining the continued need for an SSF and understanding the cost tradeoffs from different operational statuses. CBP initially estimated completing this policy in September 2024, but the current estimated completion date is December 31, 2025. Until the policy is completed, it is too soon to tell if it will identify criteria or thresholds for when CBP should implement operational status changes or include other cost considerations such as overcapacity fees.

Costs. We found that CBP estimated costs for SSF wraparound services from fiscal year 2021 through early fiscal year 2024, but its cost estimating process did not fully account for risks and uncertainty associated with operating SSFs.[38] Reliable cost estimating is a critical function for federal agencies and helps minimize risk of cost overruns and performance shortfalls.[39] Moreover, having a realistic estimate of projected costs, such as developing a range of costs that accounts for unknown risks and changing circumstances, can support effective resource allocation and increase the probability of a program’s success. CBP officials stated they received informal guidance to develop cost estimates for future SSF wraparound services by using prior year costs. As such, CBP’s estimates for future costs were based on the existing number of SSFs and the costs associated with maintaining them at that point in time.

CBP officials added that trends in apprehensions are inherently difficult to predict, which makes cost estimating more difficult. To account for unknown future needs, CBP officials explained they also assessed prior year costs for things like overcapacity fees and consumables like clothing, diapers, and shoes, and included these in cost estimates for SSF wraparound services. CBP officials also reported conducting a sensitivity analysis on the previous 2 years of cost information and incorporating the positive variation into their cost estimates.

While CBP’s cost estimates accounted for some key cost elements, we found instances where its approach to cost estimating could omit hundreds of millions of dollars in potential changes. For example, in April 2023, CBP modified its El Paso SSF contract to add additional capacity for 2,500 apprehended individuals. This change in operations resulted in an additional $140 million in contract obligations that CBP had not previously accounted for in its fiscal year 2023 estimate of $786 million.[40] CBP’s process of only using prior year costs for estimating future SSF wraparound services costs does not account for risk and uncertainty, such as mobilizing, expanding, or demobilizing SSFs, all of which could result in a range of cost estimates. As part of assessing lessons learned, understanding potential SSF wraparound costs is important to CBP’s ability to identify and plan for future funding needs, including considering where funding tradeoffs may need to be made. For example, CBP officials told us that SSF funding needs beyond what CBP received appropriations for could result in cuts in other areas within CBP operations.

Leading practices for program and project management emphasize the importance of identifying and applying lessons learned both during and at the end of a program.[41] As noted earlier, SSF wraparound services contract obligations increased from $170 million in fiscal year 2019 to $1.4 billion in fiscal year 2024—a significant investment that would have benefitted from this type of analyses.

Recognizing the value of leading practices that we and others have identified, DHS has incorporated some leading practices into its acquisition policy to inform decisions about high dollar service acquisitions supporting mission critical needs.[42] For example, under DHS and CBP’s acquisition framework, service acquisition programs are to identify program requirements—such as staffing requirements and operational status criteria—and costs in measurable and quantitative terms. Such programs would also collect lessons learned as part of post-implementation reviews, including programmatic successes and failures, to improve DHS acquisition programs and processes based on lessons learned and to minimize the risk of repeating past mistakes. According to CBP officials we spoke with, SSF services were not considered as a service acquisition program and thus CBP was not required to complete these analyses, in part because CBP was reacting quickly to meet urgent operational needs. However, these officials acknowledged that whether to manage SSF requirements as a service acquisition program was a consideration that could still occur in the future.

Since the SSFs are currently no longer operational, we are not recommending that CBP identify program requirements or create a life-cycle cost estimate in accordance with DHS acquisition policy. However, as we and others have previously found, agencies can learn lessons from an event and make decisions about when and how to use that knowledge to change behavior in the future to improve future performance.[43] Identifying lessons learned from its SSF experiences could provide DHS with key information to improve its management of SSFs, if they are needed in the future. These lessons learned could include defining objectives—such as staffing requirements or criteria for operational status changes—to clearly enable the identification of risks and implement control activities. In the case of SSFs, these control activities would include developing policies, such as the draft policy being developed by the Facility Planning Working Group.[44] They could also include steps to develop more reliable cost estimates, such as a range of costs that accounts for risks and uncertainty, which are crucial for realistic planning, budgeting, and management.[45]

CBP has an opportunity to reassess its SSF acquisition planning and management approach for the future and account for lessons learned, including those related to SSF staffing and operational requirements and cost estimating. In light of the requirements and cost estimating concerns we identified, taking steps to identify lessons learned from its experiences over the past 6 years could position CBP to make more informed investment decisions related to temporary facilities in the future. Moreover, identifying lessons learned and the implications of not conducting key planning and analyses steps that would have better informed its staffing and operational requirements and cost estimating will be especially relevant, since some of these services are also expected to support JPCs.

DHS Did Not Conduct Key Planning and Analyses to Inform Requirements for and Costs of Joint Processing Centers

DHS has begun planning efforts for JPCs, which are expected to cost billions of dollars in the coming years, but it is not managing the related investments in accordance with leading acquisition practices. These practices emphasize the importance of conducting key planning and analysis to inform decisions and manage high dollar investments. However, DHS officials told us that they do not think construction projects like JPCs fit within the framework of leading practices, some of which are reflected in DHS’s policy for major acquisition programs. DHS’s Under Secretary for Management has the discretion to designate programs as major acquisitions subject to DHS’s acquisition framework, but did not do so for JPCs.

DHS began its planning efforts for JPCs in 2022 after receiving $330 million for their development and construction in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022.[46] DHS intended for JPCs to provide additional permanent processing and holding capacity and help reduce reliance on SSFs in the future. DHS established a JPC Task Force with representatives from DHS components and other agencies to develop requirements and lead the integrated effort to plan, design, build, and implement JPCs along the southwest border. Officials from the task force said they incorporated some flexibility into the JPC design, with plans to use moveable walls to adjust to user needs. Officials also included more specific design requirements identified by task force stakeholders, such as a dedicated space for non-governmental organizations and design elements to accommodate child welfare and translation service needs.

In October 2024, DHS began construction of the first JPC—in the Laredo sector—and it plans to complete construction in 2027. Based on our review of preliminary operational costs identified by DHS in November 2024 and construction obligations reported as of May 2025, it is expected that the overall life-cycle costs for building and operating the Laredo JPC for a lifespan of at least 30 years could exceed $1.4 billion.[47] Given DHS’s plans to construct five JPCs, the overall costs for building and operations could exceed $7 billion.

Leading practices related to acquisition management emphasize the importance of conducting analyses and documenting plans and strategies for large investments, including construction of capital assets.[48] For example, our Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide states that having a realistic estimate of projected costs allows for effective resource allocation and increases the probability of a program’s success.[49] Additionally, standards for internal control state that to identify and mitigate risk, program objectives such as a baseline for cost and schedule should be clearly defined in measurable terms so performance in attempting to achieve those objectives can be assessed.[50] The standards further state that management should maintain documentation of an internal control system and identify, analyze, and respond to risks and their effect on achieving objectives. DHS acquisition policy for major acquisition programs—including qualifying capital assets and construction projects—aligns with and emphasizes the benefits of these leading acquisition management practices.[51]

DHS’s major acquisition program framework emphasizes the importance of completing additional planning analyses for large-dollar investments, including construction. For example, major DHS programs would be expected to establish a concept of operations document early in the acquisition planning process before beginning construction. The document would identify and define basic operational requirements, like how many staff are needed, which would affect the associated costs. However, DHS did not define its JPC operational needs in a concept of operations or a similar document. According to JPC Task Force officials, the department did not do so because it wanted to wait for JPC construction to be more complete. The officials said they plan to begin drafting a concept of operations in mid to late 2025. DHS also did not complete other planning analyses, such as a life-cycle cost estimate or risk management plan, as identified in DHS’s acquisition management directive. Further, the department does not plan to complete them since it is not managing JPCs as a major acquisition program, according to task force officials.

Table 4 provides examples of the types of planning analyses that leading practices and DHS policy identify as key to effectively planning and managing major acquisitions, which include construction, and our assessment of whether DHS has plans to complete them for its JPCs.[52]

Table 4: Selected Analyses from Leading Practices for Acquisition Management Compared to DHS’s Planning for Joint Processing Centers (JPC)

|

Analysis |

Description |

Planned to complete for JPCs? |

|

Acquisition Program |

The Acquisition Program Baseline formally documents the program’s critical cost, schedule, and performance parameters, expressed in measurable, quantitative terms that must be met to accomplish the program’s goals. Tracking program performance against this baseline can alert management to potential problems, such as cost growth or requirements creep, so they can take early corrective action. |

Ð |

|

Analysis of Alternatives |

The analysis of alternatives is an analytical comparison of selected solution alternatives for fulfilling the specific needs. An analysis of alternatives examines various alternative ways to implement a solution. As a result, it provides leadership and stakeholders with objective information needed to select an optimal solution. |

Ð |

|

Concept of Operations |

The concept of operations describes the ways an acquisition will be used in actual operations and allows stakeholders to visualize how the new solution will operate in the real world, how it will address capability gaps and meet new challenges, and how it will impact stakeholders. It is also a source of information for developers, systems engineers, and design teams to support requirements development, planning, and design activities. |

✔a |

|

Life-Cycle Cost Estimate |

A life-cycle cost estimate determines the program’s affordability and provides an exhaustive and structured accounting of all past, present, and future resources and associated cost elements required to develop, produce, deploy, support and dispose of a program. Life-cycle cost estimates also support DHS’s annual budget planning process. |

Ð |

|

Operational Requirements Document |

The operational requirements document captures operational requirements, identifies which of these requirements are Key Performance Parameters, and establishes initial and full operational capability for performance and schedule baselines. DHS’s ability to acquire major systems that meet operational mission needs within cost and schedule constraints begins with the establishment of operational requirements. |

Ð |

|

Risk Management Plan |

Details the process used to identify, analyze, respond to, and report acquisition program risk. Identifies how the program will manage any risks that arise as program proceeds through the acquisition life-cycle framework. |

Ð |

Legend:

Ð = DHS does not plan to do that analysis

✔ = DHS is planning to do that analysis

Source: GAO assessment of Department of Homeland Security (DHS) policy, GAO analysis on leading practices, and interviews with JPC Task Force officials. | GAO‑25‑107346

aJPC Task Force officials explained they plan to start the concept of operations for the Laredo JPC in mid to late 2025 and expect future JPCs will follow the same processes and procedures outlined in that document.

JPC Task Force officials said they did not conduct key planning analyses to inform current and future JPC investments because they are not managing JPCs as a formal acquisition program. Officials told us that they do not think construction projects like JPCs fit within the framework of the leading practices reflected in DHS’s policy for major acquisition programs because the construction process does not align with the milestones under the framework. However, the DHS instruction that implements and explains the framework for DHS acquisition programs defines such programs to include construction and emphasizes the value of conducting planning and analyses.[53]

A senior DHS official also stated that they believe that managing JPCs as a formal acquisition program would be duplicative, since the office that manages DHS-wide acquisition program policy, governance, and oversight—the Office of Program Accountability and Risk Management—falls under the Management Directorate and the Under Secretary for Management’s purview, as does the office leading the JPC Task Force.[54] Specifically, officials explained that both offices meet with and brief the Under Secretary for Management. As noted above, DHS’s Under Secretary for Management has discretion to designate an acquisition as a major acquisition program and decided not to do so for the JPCs. However, the lack of this designation does not preclude DHS from incorporating leading practices for program management.

Task force officials identified other actions they are taking to plan and manage JPC investments. For example, officials told us the JPC Task Force holds monthly meetings with the Under Secretary for Management to discuss JPCs and review briefing materials provided to congressional committees and the Office of Management and Budget on the status of the project.[55] These materials include details such as JPC design and construction updates, high-level cost estimates and timelines, and contract status. JPC Task Force officials said these materials can substitute for key analyses and decision documents because they reflect the Under Secretary for Management’s decisions. However, the briefing materials are not equivalent to the analyses established in DHS’s acquisition policy, which is used to track program progress and hold programs accountable for meeting their goals. JPC Task Force officials told us that any knowledge gaps or risks associated with not having completed typical acquisition program planning are identified, analyzed, and addressed within the task force. DHS officials acknowledged that there is no documentation of the meetings held to discuss JPCs.

Given that DHS plans to build and operate four additional JPCs after it completes the one in Laredo, at an estimated cost of $7 billion, the lack of key planning analyses poses risks for DHS’s management of its acquisition of JPCs. The completion of key analyses like an analysis of alternatives, operational requirements document, risk management plan, life-cycle cost estimate, and acquisition program baseline help track program progress and provide information to decision-makers in the department and Congress.[56]

In addition, without completing key planning analyses, DHS is not well-positioned to ensure that the Laredo JPC, currently under construction, will meet user needs. If user needs are not considered, the risk for costly changes or rework in the future increases. For example, although some aspects of the facility may allow for operational flexibility, officials from the JPC Task Force told us that DHS opted to design the Laredo JPC with a dedicated space for non-governmental organizations. JPC Task Force officials further stated that they did not consult with any non-governmental organizations on whether or how they would use the space, putting DHS at risk of not knowing whether it has designed the JPC to effectively meet user needs.

By not conducting key acquisition planning analyses identified by leading acquisition practices—including a life-cycle cost estimate, risk management plan, and other steps—DHS is not adequately managing the construction and operation of JPCs. Construction of the Laredo JPC has begun and DHS plans to invest billions of dollars for up to four additional JPCs in the future. Managing future JPCs in accordance with leading acquisition practices, including completing critical planning documents, would provide DHS with key information to inform decision-making. It would also help ensure DHS is meeting its objectives, providing sufficient oversight and information to leadership, and managing potentially billions of dollars of mission critical services efficiently and effectively.

DHS Has Not Fully Analyzed Requirements for Joint Processing Center Locations

DHS took steps to identify requirements for the locations of JPCs, but we identified shortcomings in DHS’s analysis. As of April 2025, DHS planned to build up to five JPCs along the southwest border. DHS expects to co-locate relevant stakeholders in the JPCs to streamline processing, enhance coordination, and minimize time in custody for apprehended individuals. The JPC Task Force led the development of JPC requirements.[57] According to DHS officials, the task force did this through multiple requirements gathering sessions and design standard meetings with task force members. JPC Task Force and Border Patrol officials explained that CBP and Border Patrol led location selection for the first JPC with input from stakeholders on the task force.

In November 2022, Border Patrol identified four Border Patrol locations for potential JPCs—Eagle Pass, Laredo, and El Paso in Texas, and Yuma in Arizona. However, JPC Task Force and Border Patrol officials we spoke with provided limited rationale for how the four locations were determined among the nine Border Patrol sectors along the southwest border.[58] Specifically, task force officials said they did not assess the other Border Patrol sectors—San Diego, El Centro, Tucson, Big Bend, or Rio Grande Valley—as potential JPC locations. Further, the officials told us they were not aware of any documentation or analyses that compared all potential sectors for JPC sites and did not know why other locations were not included.

In addition, we found limitations in how Border Patrol selected the first JPC location from among the four locations initially identified. According to task force officials, Border Patrol developed a set of criteria to assess and score each of the four identified locations. These criteria included proximity to highways, areas of high apprehensions, and airports, as well as the availability of contractors and the attractiveness of the living conditions for agents. Task force officials said that based on this assessment, Border Patrol used the criteria to assign a score to each location and identified the following operational priority locations for the first JPC: (1) Yuma, (2) Eagle Pass, (3) Laredo, and (4) El Paso. Border Patrol officials ultimately reordered the priority locations and CBP awarded a contract for the design and construction of the first JPC at Laredo. Task force officials explained that this was primarily because of cost and space considerations. For example, according to the officials, they narrowed the scope of potential JPC locations to Yuma and Laredo after gathering cost information on selected locations. Ultimately, Laredo was the only location of those two that was able to accommodate a 1,000-person capacity JPC.

We also found limitations in how the selection criteria were identified, defined, and applied.

· Criteria for all relevant factors not identified. The location selection criteria did not include other key factors to assess which potential JPC locations would best be suited to meet DHS’s operational needs, such as availability of other agency staff and resources. Given that the JPCs are intended to be facilities used by multiple agencies, including U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Border Patrol officials we met with noted that considering the resources of these other agencies could have been beneficial in determining JPC locations. For example, Border Patrol officials in the Yuma sector told us they were concerned that a JPC there would largely be operated by Border Patrol staff, instead of the shared operating model DHS envisions, because there are currently few staff from other stakeholder agencies in the Yuma area.

· Criteria not well-defined. The location selection criteria did not include definitions, quantitative thresholds, or measures in each case. For instance, proximity of the JPC to highways was one criterion used but was measured in “ease of minutes” with no quantitative threshold. Other criteria for location selections included “filling gaps between current processing facilities,” “availability of contract forces,” and “proximity to areas of high apprehension” without definitions or explanations of what these terms meant or how to measure them.

· Criteria not clearly applied. It is also unclear how Border Patrol applied the criteria to score sectors. Each criterion was applied to the four JPC locations and assigned a number from 1 to 3, with 3 being the best score. However, the analysis did not provide any additional information or documentation to support how location scores were determined or the threshold for different scoring numbers. For instance, Border Patrol evaluated sectors on the availability of contractor staff, and each of the four selected locations received the highest possible score. However, we found contractor staffing was a recurring challenge for SSFs in multiple sectors we visited, which could also be the case for a JPC. For example, contractor representatives we met with at SSFs cited challenges hiring and retaining armed guards and data entry processors. Furthermore, the analysis considered all criteria equally, without considering whether some criteria may be more important to meeting JPC operational goals than others. For example, the four locations were rated based on their proximity to areas of high apprehensions during a specific period, but the number of apprehensions fluctuate over time across sectors along the border. Therefore, current apprehensions may not be a good predictor of future need for a permanent facility in a specific location.

Our Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide states that appropriately defining and weighting selection criteria are best practices for an analysis of alternatives, which we have previously found can help agencies determine optimal locations for construction.[59] An analysis of alternatives is a process that compares the operational effectiveness, cost, and risks of a number of potential alternatives to address valid needs and shortfalls in operational capability.[60] Weighting selection criteria to reflect the relative importance of each criterion prior to the beginning of analysis helps ensure that the results are not oversimplified, uninformed, and biased.

Additionally, the guide notes that identifying and considering a diverse range of alternatives to meet mission needs and documenting why alternatives were or were not selected helps decision-makers avoid overlooking alternatives that might better meet their needs. Since JPCs are permanent facilities, placing them in the appropriate location is crucial so they are useful now and into the future. While DHS has already begun construction of the first JPC in Laredo, documenting how it will define, weight, and apply criteria as well as its process to identify and select future locations would provide DHS and its stakeholders increased assurance that selected locations will best meet mission needs.

DHS Has Not Fully Estimated All Costs for Its Initial Joint Processing Center in Laredo, TX

Specific to the Laredo JPC, DHS has not fully estimated what the total cost will be to build and operate it, even though DHS is planning to use the Laredo facility as a benchmark for future JPCs. DHS received $330 million in fiscal year 2022 appropriations to construct and develop JPCs and originally planned to build two 500-person capacity JPCs—one in Yuma and one in Laredo. However, DHS officials determined that the cost for two 500-person JPCs would exceed the department’s estimates and appropriated funding. As a result, officials from the JPC Task Force explained that DHS changed its JPC strategy from building two 500-person JPCs to one 1,000-person JPC. As of September 2024, DHS estimated that the Laredo JPC would cost $322 million, and, according to federal procurement data, had obligated about $287 million on its construction.[61]

In addition to design and construction costs for the Laredo JPC, the JPC Task Force identified estimated costs to operate the facility. Specifically, in May 2022 and November 2024, the task force estimated that the annual fixed costs to maintain the building would range from $12 million for a 500-person JPC to about $16 million for a 1,000-person JPC. The fixed cost includes building upkeep and basic services such as electricity and utilities. The task force also identified other costs to operate the facility based on its estimates for those same services at SSFs. For example, it estimated that operational costs for needs like caregivers, guards, food, and other supplies will be about $20 million a year. In total, DHS estimates that the cost of operating a JPC will be between $32 million to $36 million a year.[62]

However, when asked what specific services were included in these estimates, JPC Task Force officials told us they do not have a comprehensive list of services that were included. For example, the JPC Task Force provided estimates for a category called “total facility services” but could not provide a list of what items that entailed. JPC Task Force officials stated the operational costs of a JPC will be clearer by 2026 or 2027, when the operational requirements are more defined, and they will reevaluate the costs then. In the meantime, they said these operational cost estimates will be an evolving number, which we have found can affect the quality of the estimate.

DHS does not have complete information on the services that will be needed to operate the Laredo JPC, or the associated costs. This is because, as noted earlier, DHS has not developed a concept of operations or completed a life-cycle cost estimate for the Laredo JPC. A concept of operations would describe facility operations and allow stakeholders to understand how facility spaces will be used in practice and the number and type of staff required to conduct operations, all of which affect costs. Accurately estimating operational costs is important because they can represent up to 80 percent of a capital asset’s total life-cycle cost, which is an important piece of data for decision-makers.[63] Further, understanding operational requirements is critical to being able to develop a life-cycle cost estimate that includes all direct and indirect costs for planning and procurement, operations and maintenance, and disposal.

Our cost estimating guide and DHS guidance highlight the development of life-cycle cost estimates as a practice that can increase the probability of program success through assessing the program’s technical, schedule, and risk parameters; ensuring leadership involvement; and integrating requirements and funding.[64] However, JPC Task Force officials told us they do not plan to start a concept of operations until mid to late 2025, even though construction in Laredo started in 2024. Further, officials noted that they do not plan to complete a life-cycle cost estimate, since DHS is not managing JPCs as a major acquisition program and thus no estimate is required. Our cost estimating guide states that fully understanding requirements helps increase the accuracy of cost estimates.[65] The guide also notes that cost estimates are necessary for government acquisitions because they can help programs support decisions about funding one program over another, develop annual budget requests, and evaluate resource requirements at key decision points.

Fully estimating the life-cycle costs for the Laredo JPC—including the operational costs that DHS can include after the concept of operations is developed—would provide DHS and Congress with important insights into the resources needed to support the department’s first JPC, which is intended to be the benchmark for future JPC planning. Although DHS has already begun construction on the Laredo JPC, this JPC is expected to be operational for up to 30 years. Developing a life-cycle cost estimate could help mitigate the risk of potential cost overruns, missed deadlines, and performance shortfalls for that location. It would also inform future JPC decisions by providing decision-makers with more information on potential overall costs.

CBP Did Not Fully Oversee Contractor Performance for Selected Soft-Sided Facility Contracts

Border Patrol Agents Did Not Always Have Required Qualifications or Resources to Conduct Contract Oversight

Across the eight contracts we reviewed for SSFs and support services, technical monitors who assisted with contractor oversight at the facilities had varied levels of qualifications, direction on responsibilities, and communication with the contracting officer’s representative (COR).[66] For large or complex contracts, DHS policy allows a contracting officer or COR to work with technical monitors to conduct contract oversight through monitoring and surveillance of the contractor’s performance.[67] All the CORs for the contracts that we reviewed told us that they relied on technical monitors to help with their oversight. For example, technical monitors at one SSF told us they assisted the COR in the invoice review process to help verify that the contractor performed work being billed to the government. Figure 8 shows contractor staff at work at the Tucson SSF.

Though technical monitors performed contract oversight functions across our selected contracts in the same capacity as described in DHS’s guidebook, we identified several issues related to their qualifications, formal designation and clarity of responsibilities, and frequency of communication with CORs.

· Qualifications. Technical monitors for seven of the eight SSF and support services contracts that we reviewed told us that they were not COR-certified. DHS’s COR Guidebook states that if technical monitors are assigned, they must be certified at the same level as the COR. To obtain a COR certification at the level required by DHS, applicants for those positions must complete 40 to 60 hours of training and maintain an additional 40 hours of continued learning every 2 years.[68] Technical monitors in the El Paso sector—the one SSF location with COR-certified technical monitors—told us that while Border Patrol has solicited volunteers to take COR training, there were challenges such as certification costs and there not being a defined career path for COR-certified monitors.

· Formal designation and clarity of responsibilities. None of the technical monitors we spoke with who performed local oversight at SSFs were formally designated through an appointment letter or had their responsibilities clearly documented. DHS’s COR Guidebook states that contracting officers may appoint technical monitors through an appointment letter that delegates and outlines specific contract administration duties at the time of award. The six contracting officers we spoke with across our eight contracts reported limited interaction with technical monitors and two were unaware if there were technical monitors working on the contract. Additionally, Border Patrol officials in the San Diego sector told us there was no formal process to become a technical monitor. Instead, assignments were simply based on who was available when a need arose.

In addition, none of the technical monitors we spoke with who performed local oversight at SSFs identified having a checklist or a set of written responsibilities or instructions for conducting oversight. Technical monitors told us that having a list of tasks contractors should be doing, and metrics to measure contractor performance, would be helpful for conducting oversight and ensuring contractors are meeting their requirements. Without this information, technical monitors described instances where there was confusion among Border Patrol agents and contractor staff on what tasks caregivers, medical service providers, and wraparound service contractor staff should perform. Some technical monitors told us they relied on contract documents—like the statement of work—when providing contractor oversight. However, other technical monitors told us they did not have key contract documents for all the contacts they oversaw or had to rely on the contractor to know the scope of their responsibilities.