INFLATION REDUCTION ACT

Opportunities Exist to Help Ensure GSA Programs Achieve Intended Results

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107349. For more information, contact David Marroni at MarroniD@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107349, a report to congressional requesters

Opportunities Exist to Help Ensure GSA Programs Achieve Intended Results

Why GAO Did This Study

GSA maintains more than 1,500 federally owned buildings. The Council on Environmental Quality has identified these buildings as a major source of the federal government’s greenhouse gas emissions and energy and water use. The IRA provided GSA with a combined $3.375 billion for sustainability improvements.

GAO was asked to review GSA’s IRA activities. The IRA also includes a provision for GAO to support oversight of the use of IRA funds. This report examines, as of December 31, 2024, (1) how GSA planned to use its IRA funds, (2) the extent to which it followed leading practices when selecting projects to fund, and (3) the extent to which it established IRA performance goals, among other issues.

GAO analyzed GSA’s IRA spending plan, including updates as of January 31, 2025, its IRA risk management plan, and other agency documents. GAO interviewed officials who manage GSA’s IRA programs and visited three IRA project sites, representing a range of building types and IRA funding programs to observe progress. GAO assessed GSA’s efforts for project selection against two leading practices for capital decision-making.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations, including that GSA develop a framework with criteria for selecting high-performance green building projects, add interim targets to each of its IRA performance goals, and publicly communicate its IRA goals. GSA agreed with the recommendations and stated that it plans to take actions to address them.

What GAO Found

The General Services Administration (GSA) selected 362 projects in federal buildings across the U.S. to receive Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funding, as of January 31, 2025. The funding was targeted to support low-embodied carbon materials, emerging and sustainable technologies, and high-performance green building features. Selected applications included low-emissions concrete, electric heat pumps, and building-level energy meters. GSA’s estimated costs for these projects accounted for 99 percent of its total available IRA funding. As of January 31, 2025, GSA reported obligating 49 percent of its available IRA funding and had expended 5 percent (see table). As of February 2025, GSA officials stated that the IRA program is under review and priorities and goals could change.

General Services Administration (GSA) Recorded Total Obligations and Expenditures Under the Inflation Reduction Act, as of January 31, 2025

Dollars in millions

|

Inflation Reduction Act program |

Available |

Obligated (%) |

Expended (%) |

|

Low embodied carbon materials |

$2,150 |

$767 (36%) |

$102 (5%) |

|

Emerging and sustainable technologies |

$975 |

$683 (70%) |

$49 (5%) |

|

High-performance green buildings |

$250 |

$204 (82%) |

$25 (10%) |

|

Total |

$3,375 |

$1,654 (49%) |

$176 (5%) |

Sources: GAO (analysis); GSA (data). | GAO-25-107349

GSA followed leading practices in capital decision-making when selecting projects for two of its three IRA programs. Specifically, GSA developed a framework for evaluating and selecting projects for the low embodied carbon and emerging and sustainable technology programs. In contrast, GSA had not established a selection framework for evaluating and selecting projects for the high-performance green building program. GSA officials explained that they focused on developing selection frameworks for the two IRA programs with earlier statutory deadlines of 2026 for obligating funds (the deadline for the high-performance green building program is 2031). Nevertheless, establishing a selection framework with criteria for selecting high-performance green building projects would help ensure that GSA makes sound capital investment decisions for this program, including any adjustments to existing selections that it may choose to make.

GSA established 11 performance goals to track progress across its IRA programs as of December 31, 2024. Each goal had one or more quantitative targets with associated time frames. The time frames were typically upon completion of the final IRA project, which was at least several years in the future. However, GSA had not established interim targets for any of the 11 performance goals, which is a practice that could help the agency assess whether it is achieving its goals over time. In addition, no one public document contained all the goals, and the public descriptions of three of the goals did not mention the goals’ targets. GSA officials noted that the IRA does not require it to publish performance goals. They said that GSA often chooses not to publish goals beyond those required, instead using them internally to help ensure effectiveness. However, without readily accessible and more complete performance information, Congress and the public will have only limited insight into whether GSA’s $3.375 billion in IRA project investments are achieving their intended goals.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Abbreviations

|

Btu |

British thermal unit |

|

CIPMO |

Climate and Infrastructure Program Management Office |

|

E&ST |

emerging and sustainable technology |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

HPGB |

high-performance green building |

|

IIJA |

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act |

|

IRA |

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 |

|

LEC |

low embodied carbon |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

OPD |

Office of Project Delivery |

|

PBS |

Public Buildings Service |

April 29, 2025

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

Chairman

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Bruce Westerman

Chairman

Committee on Natural Resources

House of Representatives

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

The General Services Administration (GSA) maintains more than 1,500 federally owned buildings that federal agencies use for office space, land ports of entry (U.S. border stations), courthouses, laboratories, post offices, and other purposes. The Council on Environmental Quality has identified these buildings as a major source of the federal government’s greenhouse gas emissions and energy and water use.[1] The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) provided GSA with a combined $3.375 billion for low-carbon construction materials; for emerging and sustainable technologies; and to convert buildings to high-performance green buildings.[2] The funding for the first two purposes is available through fiscal year 2026, while the funding to convert buildings to high-performance green buildings is available through the end of fiscal year 2031.[3]

You asked us to review GSA’s IRA activities.[4] Additionally, the IRA includes a provision for GAO to support oversight of the use of funds appropriated in the IRA.[5] This report examines, as of December 31, 2024, (1) how GSA planned to use its IRA funds; (2) the extent to which it followed leading practices when selecting projects to fund; (3) the extent to which it identified, analyzed, and responded to IRA risks; and (4) the extent to which it established IRA performance goals.[6]

To examine how GSA planned to use its IRA funds, we analyzed the agency’s Status of Funds report, which included its IRA spending plan, reviewed project documents, and interviewed officials who manage GSA’s IRA programs.[7] We also reviewed the Status of Funds report to identify how much of GSA’s IRA funding the agency had obligated and expended as of January 31, 2025.[8] To determine the reliability of the funding data, we compared funding amounts in the report to funding information in associated project authorizations for consistency and completeness, and interviewed knowledgeable officials about the data and any discrepancies in the data. We determined the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing the status and use of IRA funds.

In addition, we visited three IRA project sites to observe progress or discuss project plans.[9] We selected project sites that represented a range of building types and IRA funding purposes and were located in GSA regions that had obligated the most IRA funds at the time of our selection. We selected three regions—the Heartland Region (Region 6), the Pacific Rim Region (Region 9), and the National Capital Region (Region 11)—and interviewed GSA officials from those three regional offices. These visits are not generalizable to all regions but provided insights into GSA’s use of IRA funds.

To examine the extent to which GSA followed leading practices when selecting projects to fund, we reviewed internal guidance on project selection and project scorecards the agency used to document project evaluations. We compared GSA’s guidance, scorecards, and process for selecting projects to leading practices for selecting capital investment projects as identified in GAO’s Executive Guide for Leading Practices in Capital Decision-Making and the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Capital Programming Guide.[10] The executive guide identifies five principles and 12 associated leading practices for capital decision-making. We focused on two of the three leading practices under the second principle, “evaluate and select capital assets using an investment approach,” because this aligned with our assessment of GSA’s processes for selecting IRA projects. Those leading practices are (1) establish a review and approval framework supported by analyses and (2) rank and select projects based on established criteria. We did not include the third practice under this principle—”prepare a long-term capital plan”—because our analysis focused on GSA’s processes for selecting projects under the IRA program and not on GSA’s planning decisions for its entire portfolio.

We evaluated the appropriateness of GSA’s selection criteria by comparing them against identified IRA risks and strategic goals identified in GSA’s Public Buildings Service’s (PBS) internal strategic plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027. We also obtained information from GSA on its “core assets,” which we used to determine whether the projects that GSA selected to receive funding for cleaner construction materials were located at those assets.[11] We also interviewed GSA officials who oversee GSA’s IRA programs, GSA’s portfolio of federal buildings, and GSA’s building sustainability efforts.

To examine the extent to which GSA identified, analyzed, and responded to IRA risks, we reviewed GSA’s IRA risk management plan, focusing on risks that GSA prioritized as high risks. We also focused on fraud risk because GSA’s Office of Inspector General identified fraud risk as a challenge GSA faced in executing IRA-funded projects.[12] We also interviewed GSA officials about GSA’s risk management efforts. We compared GSA’s efforts to the internal control principle that agencies should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the agency’s objectives as well as to relevant practices in GAO’s fraud risk framework.[13] Additional information on IRA risks can be found in appendix I.

To examine the extent to which GSA established IRA performance goals, we reviewed GSA’s documentation of such goals in several places, including GSA’s public IRA website; PBS’s internal strategic plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027; an internal GSA IRA status report; and GSA’s Consolidated IRA Investment Plan that it presented to OMB.[14] We also interviewed GSA’s IRA program management officials. We compared the goals and GSA’s external communications about the goals to leading practices for the use of performance information and the internal control principle that agencies should communicate necessary quality information so that both the agency and relevant external parties can achieve the agency’s goals.[15]

We conducted this performance audit from January 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

GSA’s Construction Project Process

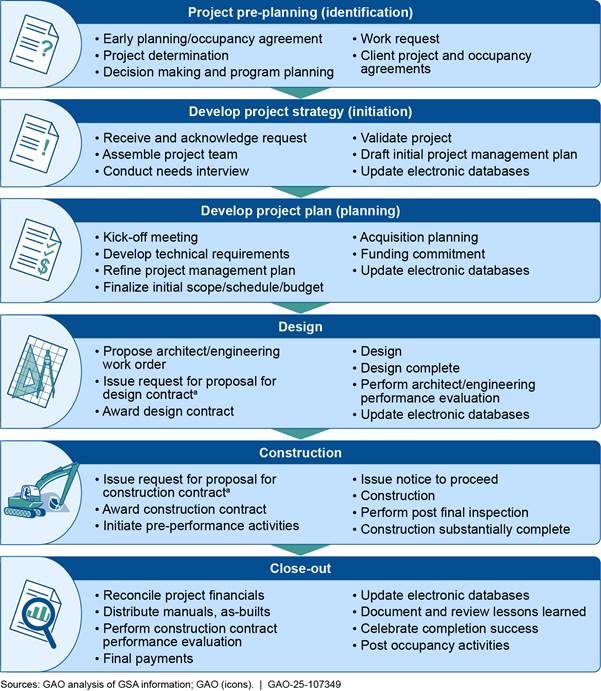

GSA oversees two main types of construction projects: (1) capital projects, which include new building construction and major repairs and alterations with total estimated construction costs that exceed a certain “prospectus threshold,” and (2) minor repair and alterations projects, which are any projects with a total estimated cost below the prospectus threshold.[16] GSA’s construction projects have six phases: identification, initiation, planning, design, construction, and close-out (see fig. 1). For capital projects, the President’s budget request for GSA typically includes funding for projects at the end of the planning phase and prior to the design phase.

aThere are cases where design and construction are awarded on the same contract.

IRA Programs

The IRA provided $3.375 billion to GSA for three programs which enhance the sustainability of its portfolio of federal buildings. These programs relate to (1) using low embodied carbon (LEC) construction materials, (2) supporting emerging and sustainable technologies (E&ST), and (3) converting federal buildings to high-performance green buildings (HPGB).[17] All three programs also support broader sustainability efforts at GSA, about which we have previously reported.[18] As noted in that report, GSA’s sustainability efforts stem from broader executive and congressional directives, which have varied over the last several decades. Some of these directives, such as Executive Order 14057, Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal Sustainability, have been rescinded.[19] The following provides additional details for each of GSA’s IRA programs.

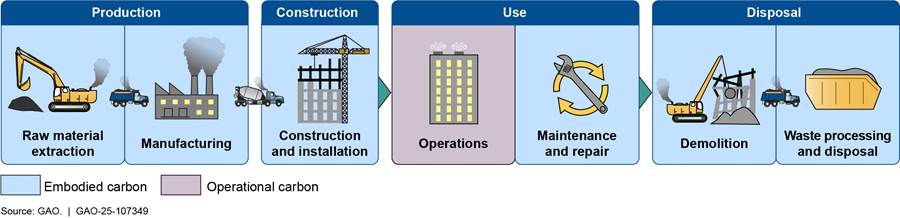

· LEC construction materials: The IRA provided GSA $2.15 billion for the purchase of low embodied carbon construction materials. The act requires the materials to have “substantially lower levels of embodied greenhouse-gas emissions associated with all relevant stages of production, use, and disposal as compared to estimated industry averages of similar materials or products, as determined by the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).”[20] In December 2022, EPA issued an interim determination to provide GSA with actionable guidelines for selecting low embodied carbon materials for its IRA LEC projects.[21] The interim determination prioritizes materials and products that have the lowest “global warming potential” in the production stage, with the intention to address global warming potential in the use and disposal stages in the future.[22] To qualify for use on projects that are LEC-funded, GSA requires contractors to provide it with Environmental Product Declarations that document the materials’ global warming potential.[23] EPA’s interim determination and GSA’s LEC program focus on four materials: asphalt, concrete, glass, and steel. Additionally, the program considers only greenhouse gas emissions reductions from material extraction, transportation to manufacturing, and manufacturing. See figure 2 for examples of embodied carbon and operational carbon.

· E&ST: The IRA provided GSA with $975 million to support emerging and sustainable technologies and related sustainability and environmental programs. GSA viewed the program as supporting several of its pre-existing sustainability efforts. Those efforts include deep energy retrofits, which renovate federal buildings with multiple measures, such as electric heat pump technology, to reduce energy use; smart building technologies, which include advanced meters and sensors that help optimize building operations and energy use and enhance occupant comfort; electric vehicle supply equipment for building an electric vehicle charging network for the federal government’s electric vehicle fleet; and the Green Proving Ground for testing emerging and sustainable building technologies in real-world settings.

· HPGB: The IRA provided GSA with $250 million to convert more GSA buildings into high-performance green buildings. The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 established the GSA Office of Federal High-Performance Green Buildings.[24] This office develops government-wide best practices, guidance, and tools pertaining to budgeting and contracting to minimize the environmental impact of buildings. The Council on Environmental Quality’s 2020 Guiding Principles for Sustainable Federal Buildings includes six principles for sustainable federal buildings that were developed based on fundamental sustainable design practices.[25] According to GSA, practices identified in this guidance serve as a source for identifying investments, such as building-level energy and water meters, that may be funded with IRA HPGB funds.

GSA Roles and Responsibilities

Within GSA, PBS manages real property for many civilian federal agencies and has a large portfolio of federally owned and leased properties. GSA is responsible for approximately 1,500 federally owned buildings, including their design, construction, operation, and maintenance, as well as the sustainability efforts associated with those activities. As of December 31, 2024, PBS staff were located in GSA’s headquarters and in each of GSA’s 11 regions, which at that time were responsible for the buildings in their regions.

The Climate and Infrastructure Program Management Office (CIPMO)—located within PBS at the time of our audit work—oversees the delivery of both IRA-funded projects and projects funded under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).[26] CIPMO assists GSA regions in executing IRA projects across the nation. Its oversight role includes tracking program progress, approving financial allocation requests, monitoring and providing program status information to internal and external stakeholders, and developing a risk management program to help ensure program success. Several offices within PBS also provide support for IRA activities, including the Office of Portfolio Management and Customer Engagement, the Office of Facilities Management, and the Office of Acquisition Management.

GSA Planned to Use Most of Its IRA Funding to Enhance the Sustainability of Courthouses, Land Ports of Entry, and Office Buildings

GSA Selected Projects that Accounted for 99 Percent of Its IRA Funds

As of January 31, 2025, GSA had selected 362 projects to receive IRA funding.[27] According to GSA’s IRA spending plan, estimated IRA costs for these projects total $3.35 billion, or 99 percent, of the agency’s available IRA funding. According to GSA officials, the spending plan is a living document that GSA uses to track its project selections. Until GSA first obligates IRA funds on a selected project, GSA’s selection of the project is subject to change.[28]

GSA officials told us selected IRA projects included both ongoing projects—for which GSA planned to substitute IRA funding for other funding sources, which GSA could then reallocate—and planned projects that were not fully funded prior to the enactment of the IRA. IRA funding can only be spent on items related to the GSA IRA statutory provisions. GSA officials told us that because the IRA funding is limited to particular uses and projects typically include other elements, most selected projects required funding in addition to that provided by the IRA.[29]

According to GSA’s spending plan as of January 31, 2025, estimated LEC costs for selected projects accounted for 100.1 percent of the appropriated LEC funding (see table 1). According to GSA officials, the estimated cost exceeded the available funding because GSA selected extra LEC projects in case some selected projects did not develop as quickly as needed to meet the 2026 fiscal year-end deadline to obligate funds. The officials said that GSA planned to bring the total costs for its LEC projects in line with available funding by adjusting project budgets or not moving forward with some of the selected projects. GSA had planned for most of its available E&ST and HPGB funding. In 2024, GSA officials told us they might use HPGB funding as contingency for projects planned to receive E&ST funding as the HPGB funds can be used for similar purposes.

Table 1: General Services Administration’s (GSA) Total Estimated Costs for Projects Selected to be Funded by GSA’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Programs, as of January 31, 2025

Dollars in millions

|

IRA program |

Total estimated project costs |

Total |

Costs as percentage of available |

|

Low embodied carbon |

$2,152 |

$2,150 |

100.1a |

|

Emerging and sustainable technologies |

$957 |

$975 |

98.2 |

|

High-performance green buildings |

$244 |

$250 |

97.8 |

|

Total |

$3,354 |

$3,375 |

99.4 |

Source: GAO analysis of GSA data. | GAO‑25‑107349

Note: According to GSA’s Inflation Reduction Act Executive Program Status through February 13, 2025, all IRA disbursements were on hold, and obligations were being limited to active construction projects. In addition, GSA officials stated the entire IRA program was under review, and priorities and goals for the program could change.

aAccording to GSA officials in 2024, the estimated cost of low embodied carbon projects exceeded the available funding because GSA included some extra projects to account for projects that might not develop as quickly as needed to meet the 2026 fiscal year-end deadline to obligate funds. The officials said that GSA planned to bring the total costs for these projects in line with available funding and had not obligated this amount of funds.

Selected Projects Ranged in Geographic Location, Facility Use, and Estimated IRA Cost

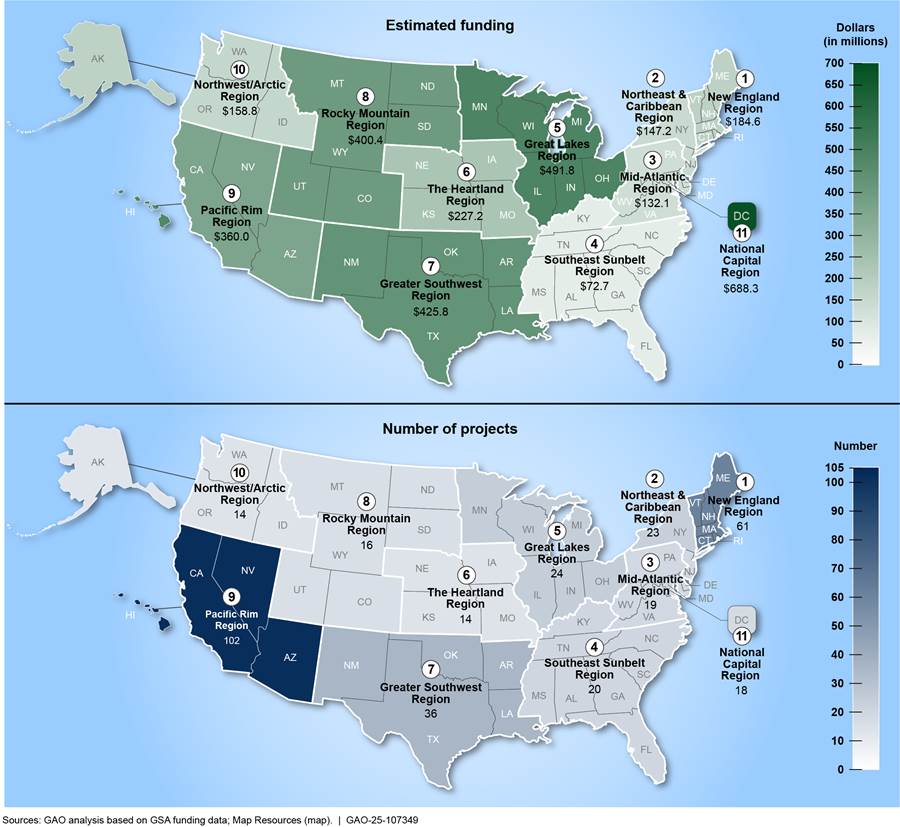

Selected IRA projects spanned across all 11 GSA regions (see fig. 3). According to GSA’s IRA spending plan as of January 31, 2025, selected projects in Region 11 (the National Capital Region) were expected to receive the most IRA funding, and Region 9 (the Pacific Rim Region) had the most selected projects.

Figure 3: Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Estimated Funding and Number of Projects Per Region of the General Services Administration (GSA), as of January 31, 2025

Note: According to GSA’s Inflation Reduction Act Executive Program Status through February 13, 2025, all IRA disbursements were on hold, and obligations were being limited to active construction projects. In addition, GSA officials stated the entire IRA program was under review, and priorities and goals for the program could change.

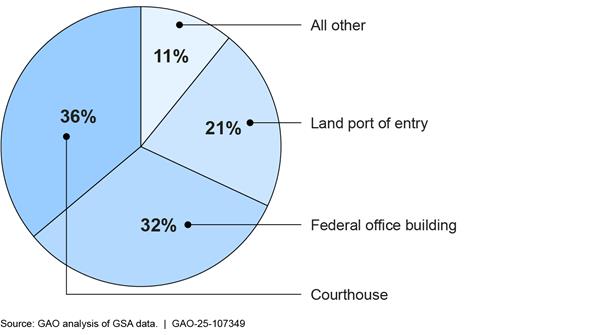

As of July 2024, 89 percent of selected IRA projects were planned to take place in courthouses, federal office buildings, and land ports of entry (see fig. 4). The selected projects in courthouses and federal office buildings were distributed across all 11 regions, though about 22 percent of the federal office buildings selected to receive IRA funding were in the National Capital Region. For example, about $16 million in E&ST funding was planned for the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center in Washington, D.C. In 2024, this building provided federal office space for agencies such as the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Department of Commerce, and the Department of Homeland Security. According to GSA officials we met with, this funding was for an existing National Deep Energy Retrofit project, and GSA planned to use E&ST funding to support the installation of electric heat pumps to lower energy usage for heating and cooling the building.[30] We also found that the land ports of entry receiving IRA funding were distributed across regions with border states. About 60 percent of these land ports of entry projects were located along the northern border, with the remaining along the southern border.

Figure 4: General Services Administration’s (GSA) Planned Project Funding from the Inflation Reduction Act, Percentage of Total Project Funding by Facility Type, as of July 19, 2024

Notes: “All other” includes warehouses, public facing facilities such as post offices, parking structures, laboratories, data centers, and museums.

According to GSA’s Inflation Reduction Act Executive Program Status through February 13, 2025, all Inflation Reduction Act disbursements were on hold, and obligations were being limited to active construction projects. In addition, GSA officials stated the entire IRA program was under review, and priorities and goals for the program could change.

GSA’s planned IRA funding per project ranged from $2,000 to nearly $200 million. Many of the smaller projects, accounting for more than half of the individual buildings that GSA selected to receive IRA funding, are expected to receive E&ST funding to install meters under GSA’s Advanced Metering Program. These meters will replace or supplement existing meters to help GSA collect data and calculate operational greenhouse gas reductions, energy savings, water savings, and operational cost avoidance. The projects with the largest IRA funding amounts—more than $100 million—are capital investment projects that Congress previously approved for funding. For example, in fiscal year 2016, Congress appropriated $341 million for the ongoing process of consolidating the Department of Homeland Security at the St. Elizabeths West Campus in Washington, D.C. GSA selected the portion of the project related to constructing a new building for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency to receive more than $113 million in IRA funds for LEC materials and $27 million in IRA HPGB funding to make it a certified LEED Gold facility.[31]

GSA Obligated 49 Percent of Its IRA Funds and Expended 5 Percent

As of January 31, 2025, GSA reported obligating 49 percent of its available IRA funding and had expended 5 percent.[32] The obligated funds covered about half of GSA’s selected IRA projects, and the expended funds covered about 30 percent of GSA’s selected projects. As shown in table 2, the LEC program—the largest of GSA’s three IRA programs—had the most recorded dollars obligated and expended of the three IRA programs. However, in terms of percentages of available funding, the HPGB program had obligated the highest percentage (82 percent), and the LEC program had obligated the lowest percentage (36 percent). Both the LEC and E&ST programs had expended about 5 percent of their available funding, and the HPGB program had expended about 10 percent.

Table 2: General Services Administration (GSA) Recorded Total Obligations and Expenditures Under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), as of January 31, 2025

Dollars in millions

|

IRA program |

Available |

Obligated (%) |

Expended (%) |

|

Low embodied carbon |

$2,150 |

$767 (36%) |

$102 (5%) |

|

Emerging and sustainable technologies |

$975 |

$683 (70%) |

$49 (5%) |

|

High-performance green buildings |

$250 |

$204 (82%) |

$25 (10%) |

|

Total |

$3,375 |

$1,654 (49%) |

$176 (5%) |

Source: GAO analysis of GSA data. | GAO‑25‑107349

Note: According to GSA’s Inflation Reduction Act Executive Program Status through February 13, 2025, all IRA disbursements were on hold, and obligations were being limited to active construction projects. GSA officials stated the entire IRA program was under review, and priorities and goals for the program could change.

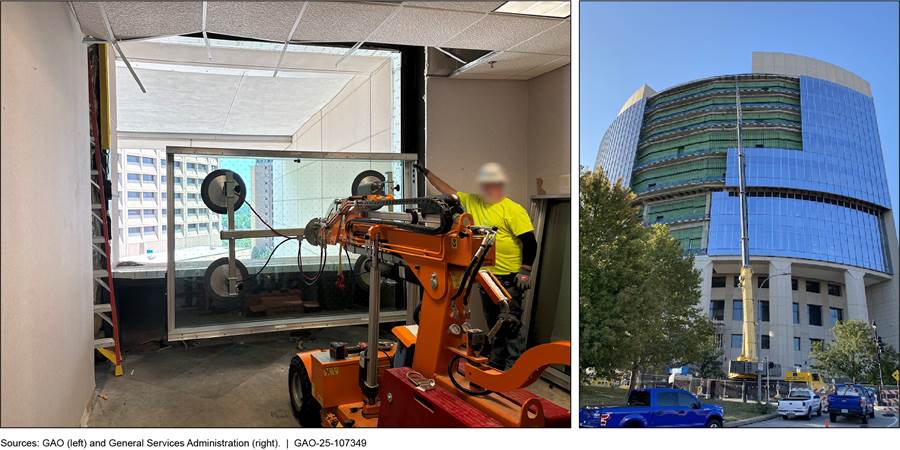

As discussed in more detail later in this report, GSA developed quarterly targets for obligating its LEC and E&ST funds—including final targets of obligating all available funds—and developed a strategy to meet those targets.[33] The Charles E. Whittaker U.S. Courthouse project in Kansas City, Missouri, had the most funds expended ($40 million) at the time of our review. This project’s baseline budget was approved by Congress in 2020 to replace the deteriorating exterior glass curtain wall. According to GSA officials, the project was in the design phase when IRA funding became available, and PBS officials identified it as an opportunity to leverage LEC funding for an estimated 100,000 square feet of glass.[34] When we visited the courthouse in June 2024, contractors were removing the existing glass, and Region 6 officials told us that 60 percent of the LEC glass had been acquired (see fig. 5). According to officials, the project was expected to be completed in 2026.

Figure 5: Installation of Low Embodied Carbon Glass Window at Charles E. Whittaker U.S. Courthouse in Kansas City, Missouri, in June 2024

GSA’s Approach for Selecting Projects for Two of Three IRA Programs Generally Followed Leading Practices

GSA Established a Framework for Selecting Projects for the LEC and E&ST Programs, but Not for the HPGB Program

As of December 31, 2024, we found that GSA had developed a framework for selecting LEC and E&ST projects consistent with GAO’s Executive Guide for Leading Practices in Capital Investment Decision-Making and OMB’s Capital Programming Guide, but not for HPGB projects.[35] More specifically, the executive guide’s principle to evaluate and select capital assets using an investment approach identifies the establishment of a framework that encourages the appropriate level of management review, supported by analyses, as a leading practice that can help ensure capital investment decisions are made more efficiently and are supported by better information. However, at the time of our review, GSA had not established a selection framework for HPGB projects, despite having selected five projects to only receive such funding.

According to GSA officials, CIPMO collaborated with PBS offices, such as the Office of Portfolio Management and Customer Engagement and the Climate and Sustainability Division, to establish the selection framework for LEC and E&ST IRA projects and develop corresponding guidance for offices responsible for evaluating proposed projects. The framework broke down GSA’s selection process into rounds, which corresponded to either the LEC or E&ST program and total project cost (see table 3).[36] GSA officials told us that GSA conducted the first two rounds and submitted its related project selections to OMB for approval in the first quarter of fiscal year 2023. They added that GSA submitted the project selections for rounds 3, 4, and 5 to OMB in June 2023.

Table 3: General Services Administration’s (GSA) Funding Rounds to Select Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Projects

|

Round |

IRA funding program |

Initial pool of proposed projects |

|

1 |

Low embodied carbona |

Capital projects previously approved for funding by Congress |

|

2 |

Low embodied carbona |

Capital projects previously approved for funding by Congress |

|

3 |

Low embodied carbon |

Priority projects identified by GSA regional offices with total project costs of less than $10 million |

|

4 |

Low embodied carbon |

Projects proposed but not selected under rounds one or two |

|

5 |

Emerging and sustainable technologies |

Priority projects identified by GSA regional offices |

Source: GAO analysis of GSA documentation. | GAO‑25‑107349

aIn addition to funding from the low embodied carbon program, some projects in this round received funding from the emerging and sustainable technologies program or the high-performance green buildings program if the projects’ scope allowed those funds to be leveraged.

For each round, GSA’s selection framework included criteria to evaluate proposed LEC or E&ST projects (discussed in more detail in the next section). We found that the criteria were tailored to the IRA funding program and selection round and corresponded with supporting analyses and the appropriate level of management review required under GSA’s framework and consistent with the leading practice to establish a review and approval framework. The key similarities and differences in the various rounds of project selection that we found are summarized below:

· Management review varied based on initial selection pool. For rounds one, two, and four, GSA’s guidance directed the Office of Portfolio Management and Customer Engagement officials to select from large scale projects that needed LEC materials, had previously been approved for funding by Congress, and that met the criteria discussed below. According to GSA officials, that was the appropriate office to select these projects because it was responsible for overseeing GSA’s capital projects. For rounds three and five, GSA’s guidance directed regional offices to propose projects with a need for LEC materials or E&ST, respectively. According to GSA officials, regional offices had a better understanding of their region’s portfolio needs, especially for smaller projects that would not require congressional approval. CIPMO and the Office of Portfolio Management and Customer Engagement then worked with the regional offices to obtain the necessary information to make final selection decisions.

· E&ST project evaluation included environmental analyses and associated management review. GSA’s review of proposed projects in round five, which corresponded to projects with a need for E&ST, included criteria related to meeting GSA’s sustainability goals. Specifically, GSA guidance directed regional offices to provide the data on proposed projects to GSA’s Climate and Sustainability Division so it could calculate energy, water, and/or greenhouse gas reductions based on the building and technologies listed in the projects’ scopes. Evaluation of LEC projects in rounds one, two, and four did not include such criteria or review because these projects were primarily focused on LEC materials, and environmental benefits from LEC projects are estimated through the acquired product’s Environmental Product Declaration.

· Large scale projects were screened for opportunities to leverage funding from multiple IRA programs. While GSA’s review of projects in rounds one and two primarily focused on identifying projects with a need for one of the eligible LEC materials, GSA officials told us that the Office of Portfolio Management and Customer Engagement, with the help of Facilities Management officials, identified projects that could also leverage funding from the E&ST or HPGB programs. Our review of GSA’s data showed that GSA selected 58 projects to receive funding from multiple IRA programs (see table 4). As shown in table 4, nine of these projects were expected to receive funding from all three IRA funding programs. For example, GSA identified the San Luis Land Port of Entry modernization project in round one as an opportunity to use IRA funding from all three programs, totaling almost $100 million. The project included constructing a land port of entry using IRA funding for all LEC eligible materials, solar energy, and other sustainable practices aimed at achieving net-zero operational status.

Table 4: Number of Selected General Services Administration (GSA) Projects with Funding from More than One of the Three Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Programs, as of January 31, 2025

|

Combination of IRA programs providing funding |

Number of projectsa |

|

· Low embodied carbon · Emerging and sustainable technologies |

37 |

|

· Low embodied carbon · High-performance green buildings |

10 |

|

· Emerging and sustainable technologies · High-performance green buildings |

2 |

|

· Low embodied carbon · Emerging and sustainable technologies · High-performance green buildings |

9 |

Source: GAO analysis of GSA information. | GAO‑25‑107349

Note: According to GSA’s Inflation Reduction Act Executive Program Status through February 13, 2025, all IRA disbursements were on hold, and obligations were being limited to active construction projects. GSA officials stated the entire IRA program was under review, and priorities and goals for the program could change.

aThe number of projects in each category is subject to change.

· Project authorizations serve as the final approval for all selected projects. Once IRA projects were selected, GSA regional offices were responsible for developing project authorizations for all selected projects in their region, regardless of selection round. Project authorizations for IRA projects we reviewed generally included a project summary, a summary of sustainability goals based on the planned project scope, a project budget and baseline IRA funding, and signatures from the PBS Regional Commissioner, the PBS Assistant Commissioner of Portfolio Management and Customer Engagement, and the CIPMO Program Executive. According to GSA officials, the project authorization serves as the final project approval; once signed, regional offices may move forward with contract solicitation.

In contrast to LEC projects and E&ST projects, GSA had not established a framework for selecting HPGB projects as of December 31, 2024. In our review of GSA data, we found that GSA had selected five total projects to receive only HPGB funding as of that time. According to CIPMO officials, those five projects were originally expected to receive funding from another IRA program as well. They explained that as the project scopes were refined, the need for LEC materials was deemed insignificant; therefore, the projects would only use HPGB funding. For example, the Edward T. Gignoux U.S. Courthouse in Portland, Maine was initially selected in round one to receive an estimated $1.1 million in LEC funding and $2.1 million in HPGB funding. This project had received congressional approval for $23 million in fiscal year 2020 to upgrade the HVAC system and replace the fire alarm system. The HPGB funding was to be used to partially electrify the building by using electric air-to-water heat pumps for heating and cooling, which was projected to significantly reduce energy used to heat the building. According to GSA officials, the project’s LEC funding was to be reallocated to other projects.

According to GSA officials, three other projects that were planned to receive only HPGB funding were to support GSA’s Good Neighbor Program.[37] For example, the Nathaniel R. Jones Federal Building and Courthouse in Youngstown, Ohio was planned to receive $750,000 in HPGB funding for soil amendment and new vegetation. Original landscaping for the building, which opened in 2002, included native perennial trees, flowering plants, and grasses. However, officials said an insufficient landscape management plan and resource constraints have allowed invasive plants to overtake large portions of the landscape. They explained that GSA selected the project because it confirmed the agency’s commitment toward responsible stewardship of natural resources, federal property, and public space; removed the invasive species that have been encroaching on neighboring properties; and planted native, drought tolerant landscaping in alignment with the criteria on outdoor water use and integrated pest management in the Council on Environmental Quality’s Guiding Principles for Sustainable Federal Buildings.

As of December 31, 2024, GSA officials told us they had yet to develop a selection framework with criteria for ranking and selecting HPGB projects because the expiration date for HPGB funding was further out than the other two IRA funding programs. Establishing a framework with criteria for ranking and selecting HPGB projects would help ensure that GSA makes sound capital investment decisions that align with IRA and GSA strategic goals. GSA could apply such a framework to both future selections as well as to any adjustments to existing selections that it may choose to make. According to GSA in December 2024, the agency was planning to develop a framework for selecting HPGB projects over the next 2 fiscal years to complement E&ST funding that expires at the end of fiscal year 2026.[38] As mentioned previously, GSA officials told us that because the HPGB funding provides the most flexibility, they intended to use it as contingency for planned E&ST projects when E&ST funding ran out. Officials also noted that they were considering using HPGB funding to address emerging priorities. More expeditiously developing a framework could help ensure that GSA selects projects that will meet the agency’s priorities.

GSA Generally Evaluated and Ranked LEC and E&ST Projects Based on the Established Criteria

As of December 31, 2024, we found that, consistent with GAO’s Executive Guide for Leading Practices in Capital Investment Decision-Making and OMB’s Capital Programming Guide, GSA’s selection framework included criteria that it used to rank and select all but one LEC project and all E&ST projects.[39] According to the second leading practice under the executive guide’s principle to evaluate and select capital assets using an investment approach, ranking and selecting projects based on established criteria is beneficial because the amount of funding needed for proposed projects often exceeds the available amount. In addition, establishing criteria that link to risks and goals helps to ensure investments are aligned with agency priorities and achieve desired results. We found that GSA’s selection criteria for LEC and E&ST projects were appropriate because they linked to either IRA risks or strategic goals.

LEC

With one exception, we found that GSA consistently applied, ranked, and selected LEC projects based on the established criteria and documented results in its IRA scorecards. For all four LEC rounds, GSA’s selection framework established four criteria for ranking and selecting projects. Specifically, a project should (1) be “project ready;” (2) be associated with a “core asset;” (3) have a need for at least one eligible LEC material; and (4) improve GSA’s performance towards its strategic goals.

Project ready. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA applied, ranked, and selected LEC projects based on its established definition of “project ready” in all but one instance. As discussed in the next section, GSA identified the ability to obligate funds before they are set to expire as a high risk. Establishing the “project ready” criterion was a strategy GSA adopted to mitigate this risk because the agency is generally able to obligate funds more quickly for these projects. According to GSA officials, projects selected in round three, which corresponded to smaller projects, met the “project ready” criterion if they had detailed analyses supporting the need for the project, cost estimates, and a scope of work developed. Larger projects selected in rounds one, two, and four met the “project ready” criterion if they had been previously approved for funding by Congress.

Officials told us that, to be considered for congressional approval, projects must have detailed analyses supporting the need for the project, cost estimates, and a scope of work developed. However, we identified an instance where GSA selected a project in round four for LEC funding that did not meet GSA’s definition of “project ready” for larger projects. As of December 31, 2024, GSA had tentatively selected the Robert C. Weaver Federal Office Building in Washington, D.C., for LEC funding. GSA’s scorecards showed that this project had yet to be congressionally approved for funding. According to GSA officials, the project was considered “project ready” because the underlying analyses were completed. According to officials, this project was selected because the building was identified as a core asset at that time that needed long-term structural repairs necessary for the continued operation of the building. Officials told us GSA requested the balance of funding needed to complete the project in the President’s Fiscal Year 2025 Budget.[40]

Core asset. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA applied, ranked, and selected LEC projects consistent with the core asset criterion. According to GSA officials, as of December 31, 2024, “core assets” were determined by the financial performance, reinvestment needs, building use, historic status, and anticipated long-term space requirements and plans of federal agencies.[41] Officials told us that the Office of Facilities Management regularly evaluated every building in GSA’s portfolio on its condition, profitability, vacancy risk, use, and local alternative space options and then assigned a score between one and five. Buildings that scored poorly (or received a score of three, four, or five) were then evaluated for disposal. Buildings that received a score of one or two were considered “long-term holds,” and therefore were “core assets.” Officials explained that the PBS’s strategic plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027 identified investing in federally owned facilities and disposing of buildings that cannot meet standards of performance as a key strategy for optimizing its portfolio. According to officials, projects in rounds one, two, and four met the “core asset” criterion if they had been previously approved for funding by Congress because the agency requested funding only for buildings considered long-term holds. For projects selected in round three, CIPMO coordinated with the Office of Facilities Management to confirm that none of the proposed projects were in buildings under evaluation or already approved for disposal by PBS.

LEC materials. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA consistently applied, ranked, and selected LEC projects based on the “need for LEC materials.” Reducing greenhouse gas emissions was consistent with GSA’s IRA program objectives and PBS’s strategic plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027.[42] According to GSA officials, PBS officials reviewed the scopes of proposed projects to determine whether they needed one or more of the four eligible materials and if so, how much. According to GSA officials, the agency then estimated the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions based on industry averages for the LEC version of the needed materials.[43] According to GSA officials, and as our review found, LEC projects were ranked based on the amount of LEC materials needed, and thus the amount of greenhouse gas reductions.

Performance toward strategic goals. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA consistently evaluated proposed LEC projects for their ability to improve GSA’s performance towards strategic goals. One of GSA’s five desired outcomes in PBS’s strategic plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027 included achieving net zero operations, with buildings powered by carbon-pollution-free electricity across the PBS portfolio by 2045. The plan identified designing IRA projects to be sustainable, deep energy retrofit, net zero, or net-zero ready as a key performance goal for achieving the outcome.[44]

E&ST

We found that GSA consistently applied, ranked, and selected E&ST projects based on established criteria and documented results in its IRA scorecards. For these project selections, GSA’s selection framework directed regional offices to first identify projects that (1) were located in a “core asset” and (2) included a need for an “emerging and sustainable technology.”

Core asset. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA consistently applied, ranked, and selected E&ST projects consistent with the core asset criterion. Specifically, similar to LEC projects, CIPMO coordinated with the Office of Facilities Management to confirm none of these proposed projects were in buildings that were being evaluated for disposal or had already been approved for disposal by PBS, thus meeting the “core asset” criterion.

Need for E&ST. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA applied, ranked, and selected projects consistent with the need for E&ST criteria. According to GSA officials, CIPMO reviewed each proposed project’s scope of work to verify the need for E&ST.

For proposed projects that met the three initial criteria, we found that GSA consistently applied, ranked, and selected E&ST projects based on four additional subcriteria established in GSA’s selection framework: (1) project readiness, (2) technology infrastructure, (3) performance outcomes, and (4) strategic outcomes. As shown in table 5, GSA assigned each subcriterion a weight, which factored into each proposed project’s final score documented in scorecards.

Table 5: General Services Administration’s (GSA) Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Emerging and Sustainable Technology Criteria, Subcriteria, and Weight

|

Criterion |

Subcriteria |

Weight |

|

Project readiness (20% of overall score) |

· Anticipated award datea · Study/detailed analysis completed · Cost estimates prepared · Scope of work drafted/Independent Government Estimate completed |

n/a 4% 6% 10% |

|

Technology infrastructure (10% of overall score) |

· Is the building connected to the GSA network? · Is there End of Life Building Automation System equipment onsite? · Is the building on GSALink (Fault Detection and Diagnostics)? |

3% 5% 2% |

|

Performance outcomes (35% of overall score)b |

· Greenhouse gas reductions per IRA $ invested · IRA $ invested vs total project costa · Total operational greenhouse gas reductions · Energy use intensity reduction · Water use intensity reduction · Onsite renewable increase · Broadly deploy electric vehicle charging stations · Operational cost and least cost avoidance |

14% n/a 5% 4% 4% 4% 2% 4% |

|

Strategic outcomes (35% of overall score) |

· Brings building into compliance or keeps building in compliance with the Council on Environmental Quality’s Guiding Principles for Sustainable Federal Buildings · Deep energy retrofit (or 40% reduction from 2019 baseline) · All-electric building · Net zero energy · Supercharging of projects |

7% 9% 9% 7% 4% |

n/a = not applicable

Source: GSA documentation. | GAO‑25‑107349

aPriority factor used for ranking.

bProjects had to meet a minimum threshold to receive the full weight of the score.

Project readiness. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA applied, ranked, and selected projects consistent with the project readiness criterion. As shown in table 5 above, proposed E&ST projects met the project readiness criterion if they had detailed analyses supporting the need for the project, cost estimates, and a scope of work developed. As previously described, GSA had identified the ability to obligate IRA funds before they expire as a high risk. GSA’s risk management strategy included focusing on projects that could spend the money before the expiration date as one strategy to mitigate this risk.

Technology infrastructure and performance outcomes. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA applied, ranked, and selected projects consistent with the technology infrastructure and performance outcomes criteria. For the technology infrastructure, our review of GSA’s scorecards found that GSA ensured selected projects took place in buildings equipped with technology, such as meters, to enable GSA to monitor performance outcomes such as energy and water use savings. PBS’s strategic plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027 identified maximizing building performance and reducing operational greenhouse gas emissions through executing projects that drive toward increased efficiency and significant reduction in energy and water consumption.[45]

Strategic outcomes. We found in our review of GSA’s IRA scorecards that GSA applied, ranked, and selected projects consistent with the strategic outcomes criterion. The strategic outcomes criterion, like for LEC projects, related to PBS’s strategic plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027. GSA officials documented in the scorecards whether the emerging and sustainable technology within the scope of the project would make the building a sustainable, all-electric, or net zero energy building or would be a deep energy retrofit.

GSA Identified, Analyzed, and Took Actions to Address a Variety of Risks to Its IRA Programs

As of December 31, 2024, GSA had developed a risk management plan that identified, analyzed, and proposed actions to mitigate 15 risks to its IRA programs. According to our analysis of information provided by GSA officials, many of the proposed actions had been fully or partially implemented, including 21 of the 22 internal controls designed to help mitigate the five risks GSA designated as high-priority. Actions were ongoing to mitigate the risk of not ensuring effective stewardship of taxpayer funds through fraud controls, which GSA designated as a low priority risk. Officials said they were developing internal fraud training and used various annual reviews to periodically assess and manage fraud risks in construction programs. GSA officials also told us that they were developing a centralized fraud risk management program in fiscal year 2025 to include the creation of an agency fraud risk profile. Such a profile, according to GAO’s 2015 Fraud Risk Management Framework, is essential to an agency’s overall antifraud strategy.

GSA Developed and Was Implementing a Risk Management Plan to Mitigate Program Risks

As of December 31, 2024, GSA had developed a risk management plan that identified, analyzed, and proposed actions to mitigate 15 risks to its IRA programs. Developing such a plan is consistent with Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, which states that agencies should identify, analyze, and respond to risks related to achieving the agency’s objectives.[46] According to the standards, these steps help agencies meet their objectives. According to GSA officials, from September 2023 to August 2024, CIPMO collaborated with several PBS offices to develop the risk management plan, which GSA planned to periodically update. The plan indicated which, if any, of GSA’s four objectives for its IRA programs related to each of the 15 identified risks and identified at least three risks for each of the objectives (see table 6).

Table 6: General Services Administration’s (GSA) Objectives for Its Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Programs and Related Risks Identified by GSA, as of December 31, 2024

|

IRA objective |

Risks related to IRA objective |

|

Reduce harmful emissions. Avoid millions of metric tons in greenhouse gas emissions using low embodied carbon construction materials and improved energy-efficient building operations. |

· Not reducing harmful emissions · Not able to source compliant low embodied carbon materials in accordance with the Environmental Protection Agency’s guidance · Not monitoring and controlling program and project funding · Not obligating funds by legislated deadlines |

|

Improve efficiency and reduce long-term costs. Make federal buildings more energy efficient, thereby reducing long-term operating costs for the taxpayer. |

· Not improving efficiency and reducing long-term costs · Not monitoring and controlling program and project funding · Not obligating funds by legislated deadlines |

|

Catalyze American innovation. Increase demand for low-carbon materials and emerging/sustainable technologies in the United States. |

· Not catalyzing American innovation · Not monitoring and controlling program and project funding · Not obligating funds by legislated deadlines |

|

Create good-paying jobs. Use IRA projects to create good-paying jobs across the country. |

· Not creating good-paying jobs · Not adhering to Buy American Act and Trade Agreements Act requirements in contracts · Not monitoring and controlling program and project funding · Not obligating funds by legislated deadlines |

Source: GAO analysis of GSA information. | GAO‑25‑107349

Note: GSA also identified the following IRA program risks that it determined do not relate to any of the agency’s IRA objectives: not ensuring effective stewardship of taxpayer funds through fraud controls; not accurately coding project funding in financial systems; not addressing needs for qualified contracting officers to meet program execution; not addressing needs for qualified project managers to meet program execution; not managing cost overruns; not maintaining communication with stakeholders; and not prioritizing investments in core (long-term) assets.

For each of the 15 risks, the plan identified existing internal controls that GSA determined are mitigating the risks, such as GSA’s mandatory design standards and performance criteria for federally owned buildings maintained by GSA, as well as its training for project managers. The plan also proposed new internal controls designed to further mitigate the risk; and included two separate analyses of the risk. The first analysis assumed that only the existing internal controls were in place, while the second analysis assumed that both the existing internal controls and proposed internal controls were in place. Each analysis included GSA’s assessment of the risk’s likelihood of occurrence, which it assigned to one of seven levels, ranging from “not expected (less than 5 percent chance)” up to “almost certain (greater than 95 percent chance).” Each assessment also included GSA’s assessment of the risk’s severity of impact should the risk occur, which it assigned to one of five levels that ranged from “insignificant - no effect meeting IRA objectives/goals” to “critical - precludes meeting multiple IRA objectives/goals.” Finally, each assessment included GSA’s prioritization of the risk as either high-, medium-, or low-priority, based on the combination of the assessments of likelihood and severity. According to GSA’s second risk analyses, implementing the plan’s proposed internal controls would lower the likelihood of 10 of the risks, while the likelihood of the other five risks would remain the same. It would not affect the severity of impact of any of the risks.

As shown in table 7, in its first analysis of the risks, GSA designated five of the risks as high-priority, nine as medium-priority, and one as low-priority.[47]

Table 7: Risks Identified by the General Services Administration (GSA) Related to the Agency’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) Programs, as of December 31, 2024

|

Category |

Risk |

Prioritya |

|

Acquisition |

Not being able to source compliant low embodied carbon materials in accordance with the Environmental Protection Agency’s guidance |

High |

|

Environmental |

Not reducing harmful emissions |

High |

|

Human resources |

Not addressing need for qualified project managers |

High |

|

Project management |

Not obligating the agency’s funds appropriated by the IRA by the legislated deadlines |

High |

|

Project management |

Not managing cost overruns |

High |

|

Acquisition |

Not adhering to Buy American Act and Trade Agreements Act requirements in contracts |

Medium |

|

Human resources |

Not addressing need for qualified contracting officers |

Medium |

|

Budget |

Not accurately coding project funding in financial systems |

Medium |

|

Budget |

Not monitoring and controlling program and project funding |

Medium |

|

Political |

Not maintaining communications with stakeholders |

Medium |

|

Strategic |

Not creating good-paying jobs |

Medium |

|

Strategic |

Not improving efficiency and reducing long-term costs |

Medium |

|

Strategic |

Not catalyzing American innovation |

Medium |

|

Strategic |

Not prioritizing investments in core (long-term) assets |

Medium |

|

Acquisition |

Not ensuring effective stewardship of taxpayer funds through fraud controls |

Low |

Source: GSA’s risk management plan for the agency’s IRA programs. | GAO‑25‑107349

aGSA’s priority levels of high, medium, and low are based on the combination of the agency’s assessments of each risk’s (1) likelihood of occurrence and (2) severity of impact should the risk occur.

According to our analysis of information provided by GSA officials, GSA proposed 22 internal controls for the five high-priority risks, with the number of controls per risk ranging from five to nine (some of the controls applied to more than one risk). Based on our analysis, as of December 31, 2024, GSA had fully or partially implemented 21 of the 22 controls. More specifically, 10 of the controls were one-time actions that GSA had completed; nine were established and ongoing; two were initiated but not fully established; and one was planned for fiscal year 2025. The high-priority risks and some of the existing and proposed internal controls are described below, along with our observations. Appendix I describes all the existing and proposed internal controls for the high-priority risks.

Not being able to source compliant LEC materials in accordance with the Environmental Protection Agency’s guidance. This risk reflected GSA’s concern that compliant LEC might not be available at all of GSA’s LEC project locations, especially those outside metropolitan areas. To mitigate this risk, GSA’s risk management plan proposed six new internal controls, which GSA concluded would reduce the likelihood of the risk occurring from “very likely (greater than 70 percent chance)” to “moderate (50 percent chance).” According to our analysis, as of December 31, 2024, GSA had completed the one-time actions that comprised five of the controls, and the other control was established and ongoing. For example, GSA had increased and was targeting its outreach to industry, including explaining IRA requirements and working with them to meet IRA needs.[48] GSA reported the following increases in Environmental Product Declarations from May 2023 to May 2024, demonstrating, according to GSA, that industry was responding to GSA’s and other federal agencies’ market demand for materials made with lower emissions:

· asphalt – 903 to 3,615 declarations (300 percent increase);

· concrete – 96,853 to 111,070 declarations (15 percent increase);

· glass – 19 to 27 declarations (42 percent increase); and

· steel – 173 to 184 declarations (6 percent increase).

Not reducing harmful emissions. GSA prioritized the risk of not reducing harmful greenhouse gas emissions as “high priority,” determining that (1) there was a moderate (i.e., 50 percent) likelihood of occurrence, and (2) it would have a major impact should it occur, meaning it would preclude meeting one program objective or goal. The plan identified three existing internal controls for the risk, consisting of standards and guidance issued by GSA or the Council on Environmental Quality.[49]

To further mitigate this risk, GSA’s risk management plan proposed nine new internal controls, which GSA concluded would reduce the likelihood of the risk occurring to “not expected (less than 5 percent chance).” According to our analysis, as of December 31, 2024, GSA had completed the one-time actions that comprised five of the proposed controls, two of the proposed controls were established and ongoing, and two were initiated but not fully established. The ongoing controls included using contract support to assist in various program activities, including planning, reviewing, and analyzing energy and water specific projects and verifying compliance with contract requirements for IRA-specific deliverables.

Some of GSA’s E&ST projects aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by converting conventional buildings to “all-electric buildings,” using electricity for space and water heating and other building systems instead of using more conventional carbon-based fossil fuel sources, such as natural gas. GSA officials told us that to fully realize the potential of all-electric buildings, the buildings’ electricity needs to be obtained from carbon-free sources, such as wind or solar. However, in 2023, we reported that officials from more than half of GSA’s regions told us that their access to carbon-free electricity was limited.[50] Although GSA’s risk management plan did not identify any existing internal controls or propose any actions to address this challenge, GSA created an office in 2022 to conduct market research and identify opportunities for interagency coordination on carbon-free electricity purchases. We have not assessed the effectiveness of those efforts.

Not addressing need for qualified project managers. In its identification of this risk, GSA’s risk management plan cited a 2022 GSA Office of Inspector General report on several challenges that GSA faced in executing IIJA-funded projects, including addressing the need for qualified project managers and contracting officers.[51] In 2023, the Office of Inspector General reported that GSA faced the same set of challenges in executing IRA-funded projects.[52] With respect to the need for qualified project managers, the earlier report noted that as of May 2022, PBS employed approximately 560 project management staff, a decrease of about 12.5 percent since September 2021, and that PBS faced gaps in guidance, training, and experience levels for its project management staff, which contributed to past audit findings. GSA officials told us that as of November 2024, PBS employed 694 project management staff, an increase of 24 percent since May 2022.

GSA’s risk management plan identified five existing internal controls for this risk, including identifying skill gaps among project management staff, training and developing such staff, and quantifying needed project manager hires. The plan also proposed five new internal controls, which GSA concluded would not change the assigned likelihood level of the risk occurring. Rather, the level would remain unchanged at “very unlikely (less than 20 percent chance).” GSA officials said that while the controls were designed to ensure that projects were staffed sufficiently with trained project managers, they would not reduce the likelihood level of this risk to “not expected (less than 5 percent chance),” the next lower level in GSA’s scale, as this level represents practically eliminating the risk. According to our analysis, as of December 31, 2024, GSA had completed the one-time actions that comprised two of the proposed controls; two of the proposed controls were established and ongoing; and one was planned.

The officials also told us that GSA had assigned its IRA projects to existing project managers, contracting officers, and contracting officer representatives. They also said that the projects had the resources needed to complete them.[53] In addition, the officials told us that GSA planned to further mitigate the risk beginning in fiscal year 2025 by reviving GSA’s Office of Project Delivery Resource Board.[54]

Not obligating the agency’s appropriated IRA funds by the legislated deadlines. CIPMO officials told us that GSA viewed this risk as applying to the LEC and E&ST programs but not to the HPGB program.[55] The risk management plan identified three existing internal controls that mitigate this risk, including a tool to determine the most effective and efficient delivery method to expedite projects. To further mitigate this risk, GSA’s risk management plan proposed nine new internal controls, which GSA concluded would reduce the likelihood of the risk occurring from “moderate (50 percent chance)” to “very unlikely (less than 20 percent chance).” According to our analysis, as of December 31, 2024, GSA had completed the one-time actions that comprised seven of the proposed controls; the other two proposed controls were established and ongoing. One of the completed one-time actions was establishing a new schedule monitoring tool. One of the ongoing actions involved staff analyzing and projecting planned obligations over the life of the IRA program to determine if projects would meet the obligation and award deadlines and focusing on those projects nearing deadlines.

In addition, CIPMO had developed quarterly targets through fiscal year 2026 for obligating all LEC and E&ST funds and had developed a strategy to meet those targets. Among other actions, the strategy called for maximizing obligations by March 31, 2026, to minimize risk; leveraging LEC material funding on projects that used energy savings performance contracts; and identifying additional active capital projects that could use LEC funds. In February 2025, GSA officials noted that the entire IRA program is under review and that priorities and goals for the program could change. According to GSA’s Inflation Reduction Act Executive Program Status through February 13, 2025, all IRA disbursements were on hold, and obligations were being limited to active construction projects.

Not managing cost overruns. The risk management plan cited the 2022 Office of Inspector General report, which identified challenges PBS faced in managing potential project delays and cost overruns. According to the report, these challenges may be driven by supply chain disruptions, inflationary pressures, and—for projects at land ports of entry—the length of time needed to acquire property.[56] In its risk management plan, GSA assessed the likelihood of not successfully managing the risk of cost overruns as “very likely (greater than 70 percent chance)” with three existing internal controls in place, including using market data and considering future inflationary impacts to estimate budgets more accurately.

To further mitigate this risk, GSA’s risk management plan proposed six new internal controls, which GSA concluded would reduce the likelihood of the risk occurring to “likely (greater than 50 percent chance).” According to our analysis, as of December 31, 2024, GSA had completed the one-time actions that comprised three of the proposed controls, and the other controls were established and ongoing. The one-time actions included establishing new financial guidance for using IRA funding alone or in conjunction with other funding. The ongoing controls included using an IRA program contingency to address budget challenges, leveraging IIJA funds to support IRA projects, and adjusting IRA building and technology selections as needed to help ensure program outcomes are met within budget.

GSA Identified Fraud as a Risk and Was Developing a Centralized Fraud Risk Management Program

One of the 15 risks identified by GSA’s IRA risk management plan was the risk of not ensuring effective stewardship of taxpayer funds through fraud controls. In its identification of this risk, the risk management plan cited the 2022 GSA Office of Inspector General report.[57] That report stated that PBS must provide effective oversight of its contract awards and payments by implementing controls designed to proactively prevent, detect, and eliminate fraud, including the unique fraud risks associated with construction contracts. For example, the report cited the potential for fraud related to small business set-aside contracts and overbillings.

Based on the two-factor analysis it applied to all identified risks, GSA prioritized fraud risk as “low priority” for its IRA programs. First, the agency determined that the likelihood of the risk occurring was the lowest likelihood on GSA’s scale, i.e., “not expected (less than 5 percent chance).” Second, GSA determined that the severity of the impact of this risk, should it occur, is “moderate - precludes the program meeting components of one or more of its objectives/goals.”

In its first analysis, GSA considered three existing internal controls, including activities designed to meet the requirements in the Federal Acquisition Regulation’s part on contract cost principles and procedures.[58] To further mitigate this risk, GSA’s risk management plan proposed one new internal control, namely, fraud awareness training. CIPMO officials told us that the training was being developed by GSA’s Office of Inspector General for GSA, including GSA’s IRA project community.

GSA’s identification of fraud risk in the risk management plan mentioned three different types of fraud risk which GSA analyzed and prioritized as a single risk.[59] GAO’s 2015 Fraud Risk Management Framework calls for agencies to conduct fraud risk assessments that include individual assessments for a range of different fraud risks.[60] According to the framework, a fraud risk assessment would consider, on an individual risk basis, all internal and external fraud risks that could affect the IRA program, such as fraud related to financial reporting, misappropriation of assets, corruption, and nonfinancial forms of fraud. When asked about assessing risks on an individual basis, GSA officials told us that in addition to the risk assessment they conducted for their IRA risk management plan, the agency assessed and managed fraud risks for its construction programs at multiple agency levels. They pointed to annual reviews of programs’ internal controls, annual risk assessments of programs’ payment integrity, annual agency Statements of Assurance, and online fraud awareness and recognition courses.

GAO’s framework also calls for agencies to document the results of their fraud risk assessments in a “fraud risk profile.” According to the framework, a fraud risk profile documents the types of internal and external fraud risks the program faces, their perceived likelihood and impact, how much of each type of risk managers are willing to take on, and the prioritization of risks. The profile is an essential piece of an overall antifraud strategy and can inform the specific control activities managers design and implement. Program managers should use the fraud risk profile to help decide how to allocate resources to respond to residual fraud risks (i.e., fraud risks not addressed by existing fraud controls). GSA officials told us GSA was developing a centralized fraud risk management program to include the creation of an agency fraud risk profile in fiscal year 2025. Because these efforts were ongoing at the time of our review, we did not assess their sufficiency.

GSA Had Not Established Interim Targets for Its IRA Performance Goals and Had Not Fully Communicated the Goals

GSA Established Performance Goals and Estimated Economic Effects

As of December 31, 2024, GSA had established 11 performance goals to track the progress of its IRA programs.[61] Each of the goals aligned with one or more of GSA’s IRA objectives at that time (see table 8). For example, the performance goal to “reduce embodied carbon of building materials by 22,030 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent” aligned with the objective to “reduce harmful emissions.”[62] GSA had documented various subsets of the goals in several places, including GSA’s public IRA website, PBS’s internal strategic plan for fiscal years 2023 through 2027, an internal GSA IRA status report, and GSA’s Consolidated IRA Investment Plan that it presented to OMB.[63]

Table 8: General Services Administration’s (GSA’s) Objectives, Performance Goals, and the Goals’ Targets and Time Frames for Its Programs Funded by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), as of December 31, 2024

|

Objective: Reduce harmful emissions. Avoid millions of metric tons in greenhouse gas emissions using low embodied carbon construction materials and improved energy-efficient building operations. |

||

|

Related performance goala |

Quantitative target |

Time frame |

|

Reduce embodied carbon of building materials by 22,030 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalentb, c |

22,030 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalentb |

Length of IRA projects |

|

Reduce operational greenhouse gas emissions by 2.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalentb, d |

2.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalentb |

20 yearse |

|

Achieve net-zero operations in 26 federal buildings |

26 federal buildings |

Length of IRA projects |

|

Objective: Improve efficiency and reduce long-term costs. Make federal buildings more energy efficient, thereby reducing long-term operating costs for the taxpayer. |

||

|

Related performance goala |

Quantitative target |

Time frame |

|

Achieve energy savings in federal buildings of 47 trillion Btud, f |

47 trillion Btuf |

20 yearse |

|

Achieve water use savings in federal buildings of 540 million gallonsd |

540 million gallons |

20 yearse |

|

Avoid $710 million of operating costs in federal buildingsd |

$710 million |

20 yearse |

|

Electrify 100 federal buildings |

100 federal buildings |

Length of IRA projects |

|

Qualify 86 federal buildings as sustainable |

86 federal buildings |

Length of IRA projects |

|

Create 107 deep energy retrofit federal buildings |

107 federal buildings |

Length of IRA projects |

|

Objective: Catalyze American innovation. Increase demand for low-carbon materials and emerging/sustainable technologies in the United States |

||

|

Related performance goala |

Quantitative target(s) |

Time frame |

|

Install low embodied carbon materials |