NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

Monitoring of External Research Can Be Improved

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Hilary M. Benedict at BenedictH@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107362, a report to congressional requesters

Monitoring of External Research Can Be Improved

Why GAO Did This Study

NIH is the largest public funder of biomedical research in the U.S. According to NIH, more than 80 percent of its budget funds extramural research on a broad range of health-related topics. NIH grants management staff and program officers are the primary staff for ensuring that award recipients follow requirements.

GAO was asked to review NIH’s policies and procedures for overseeing extramural research funding. This report focuses on grants and cooperative agreements and, among other things, (1) describes trends in NIH extramural funding and oversight staffing from FY 2014 through 2023, (2) assesses the extent to which NIH policies ensure appropriate use of these funds, and (3) assesses NIH’s policies and procedures for limiting carryover of unused funds in extramural awards.

GAO reviewed agency policies, documents, and data through FY 2023 and performed checks on NIH monitoring data. GAO also interviewed federal officials, including officials from four NIH institutes, which GAO selected based on factors such as funding, staffing, and mission.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that NIH (1) identify and address the factors contributing to delinquent final financial and progress reports, (2) develop an informational resource for managing unused award balances, and (3) require that NIH institutes and centers track unused balances across their award portfolios. NIH concurred with all three recommendations.

What GAO Found

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) supported nearly 65,000 ongoing research grants and other awards to external entities in fiscal year (FY) 2023 (the most recent year of data available at the time of GAO’s review). These “extramural” awards go to entities such as universities and totaled more than $35 billion in FY 2023—an increase of nearly 30 percent from FY 2014 (after adjusting for inflation). During this period, NIH also increased its oversight staff by about 400 positions (20 percent). GAO requested, but NIH could not provide, information about the effect of recent administration actions on oversight staffing levels.

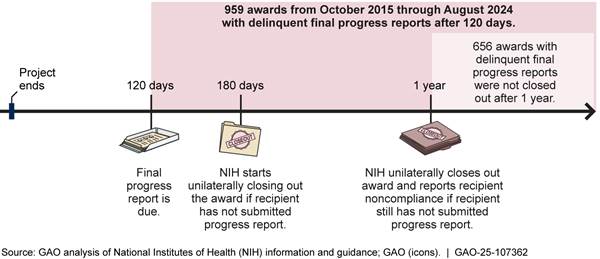

NIH reviews recipients’ financial and progress reports as part of its oversight of awards. For example, NIH program officers check whether recipients’ progress is satisfactory and whether recipients have a plan to address challenges. However, GAO found that NIH has not always closed out awards when recipients do not file final reports within 1 year of a project’s end in accordance with its policy. As of August 2024, nearly 1,000 final progress reports were delinquent, or about 0.2 percent of awards made from FY 2014 through 2024 (see figure). NIH has made recent efforts to better ensure timely closeout, but it has not identified or addressed the factors that contribute to late reports. As a result, NIH cannot ensure that it is holding recipients accountable and identifying misspent funds.

During certain grants, projects may carry over unobligated funds that remain unused at the end of a budget period into the next period. If NIH determines that some funds are not needed, it can restrict the recipient’s ability to automatically carry over funds in the future. NIH allows for flexibility in how its institutes and centers manage carryover, but it has not developed an informational resource to help them choose the best option. Moreover, NIH does not require institutes and centers to track unused balances, even though NIH data show that large unused balances are common. Without an informational resource or tracking requirement, NIH cannot be assured that it is implementing carryover practices effectively and maximizing its funding for higher-value projects.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HHS |

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services |

|

|

ICO |

institutes, centers, and offices |

|

|

NIH |

National Institutes of Health |

|

|

OER |

Office of Extramural Research |

|

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

|

OPERA |

Office of Policy for Extramural Research Administration |

|

|

RePORT |

Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tool |

|

|

RePORTER |

RePORT Expenditures and Results |

|

|

SAM |

System for Award Management |

|

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

April 29, 2025

Congressional Requesters

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), which is part of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), is the largest public funder of biomedical research in the United States. NIH seeks to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability by conducting and supporting research on a broad range of health-related topics, such as cancer, aging, mental health, and health disparities. According to NIH, more than 80 percent of its budget goes toward extramural research, which is largely made up of awards to external organizations such as universities and research hospitals. Data from NIH show that, in fiscal year 2023, it obligated over $35 billion in federal awards (primarily grants and cooperative agreements) for extramural research, which included funding for nearly 65,000 awards. These awards range in size from a few thousand dollars to several million dollars.

NIH conducts oversight of extramural awards to ensure that recipients comply with federal laws, regulations, and the terms and conditions of their awards.[1] Among the issues it monitors are the purposes for which funds are spent, changes in an award recipient’s budget (e.g., the carryover of unused funds from one budget period to the next), and the recovery by NIH of any spending on disallowed costs (e.g., funds used in a manner inconsistent with federal law or award conditions).

You asked us to review NIH’s policies and procedures for administering and overseeing extramural research funding and the extent to which NIH conducts oversight of awarded funds. This report (1) describes trends in NIH funding and oversight staffing for extramural research from fiscal year 2014 through 2023, (2) assesses the extent to which NIH policies and procedures for oversight of extramural research awards ensure award recipients’ appropriate use of funds, (3) assesses NIH’s policies and procedures for limiting carryover of unused funds on extramural awards, and (4) assesses the extent to which NIH identified and recovered disallowed costs from extramural award recipients in fiscal years 2021 through 2023.

The scope of our review includes the 25 NIH institutes, centers, and offices (ICO) that fund extramural research awards.[2] To address our objectives, we reviewed relevant federal guidance, HHS regulations, and HHS and NIH policies and procedures. We interviewed NIH officials, including those responsible for administering NIH extramural research policy and operations. We interviewed officials from four selected ICOs: the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the National Eye Institute. We selected these four to obtain a diversity of perspectives based on factors such as funding, staffing, and mission. These institutes accounted for about 25 percent of all NIH awards in fiscal year 2023.

We analyzed NIH funding and award data from fiscal years 2014 to 2023, as well as data on staffing and on award recipients’ unused funds and disallowed costs. For the award data, we included research project grants, training, construction, and other types of awards but excluded research and development contracts. We performed several checks of the data, such as comparing NIH funding and staffing data with other sources, and determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report. See appendix I for details of our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Roles and Responsibilities of NIH Entities Related to Extramural Research

NIH’s institutes, centers, and offices (ICO) award funding for research projects and are responsible for monitoring projects after making the awards. The primary staff charged with monitoring are program officers and grants management staff in the ICOs. They review reports and correspondence from the recipient, along with other information available to NIH, to ensure that the recipients follow NIH award requirements. Program officers focus on the programmatic, scientific, and technical requirements of the award. Grants management staff are responsible for the business and fiscal management of an ICO’s award portfolio.[3]

NIH’s Office of Extramural Research (OER) provides the overall framework for NIH extramural research administration by, for example, providing policies and procedures to ensure that recipients comply with award requirements and administering an electronic grant administration platform (called eRA).[4] OER also helps oversee compliance with award requirements. For example, within OER, the Office of Policy for Extramural Research Administration (OPERA) provides policy guidance for NIH extramural staff and supports standardization of award administration practices within NIH.[5]

Two divisions within the Office of Management—the administrative arm of NIH—provide key support for monitoring extramural research:

· The Division of Financial Advisory Services provides financial advice to NIH officials and resolves audit findings that affect NIH award recipients.

· The Division of Program Integrity reviews noncriminal allegations of improper employee conduct and misuse of award and contract funds by NIH award recipients, among other responsibilities.

NIH Extramural Research Funding Instruments

NIH awards funds for extramural research primarily through grants and cooperative agreements. To manage and administer these awards, NIH must comply with HHS awards regulations in which HHS has adopted, with some HHS-specific amendments, the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards, commonly referred to as the Uniform Guidance.[6] These regulations provide the framework for the terms and conditions of NIH grants and cooperative agreement that all award recipients must follow. NIH implements these regulations through its policy manual and Grants Policy Statement. Recipients are required to comply with the Grants Policy Statement, except where the notice of award states otherwise.

Individual ICOs can also develop their own policies and procedures to manage extramural research. For instance, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the National Eye Institute have standard operating procedures to manage award recipients’ requests to carry over unused funds from one budget period to the next.

NIH’s most commonly used grant program is the Research Project Grant Program. Such grants typically last 4 to 5 years. For each year of a project, program officers and grants management staff review its scientific and financial progress. Failure to submit complete, accurate, and timely reports may indicate the need for closer monitoring by NIH or may result in possible award delays or enforcement actions. According to NIH, future year funding is contingent upon satisfactory progress, availability of funds, and the continued best interests of the federal government.

At the conclusion of the project period, NIH closes out the award when the recipient and NIH have completed all applicable administrative actions and required work. The award recipient must submit accurate and timely closeout documents as required by the terms and conditions at the end of the project period, which may include final financial and scientific progress reports.

NIH Funding and Oversight Staffing for Extramural Research Increased from 2014 to 2023

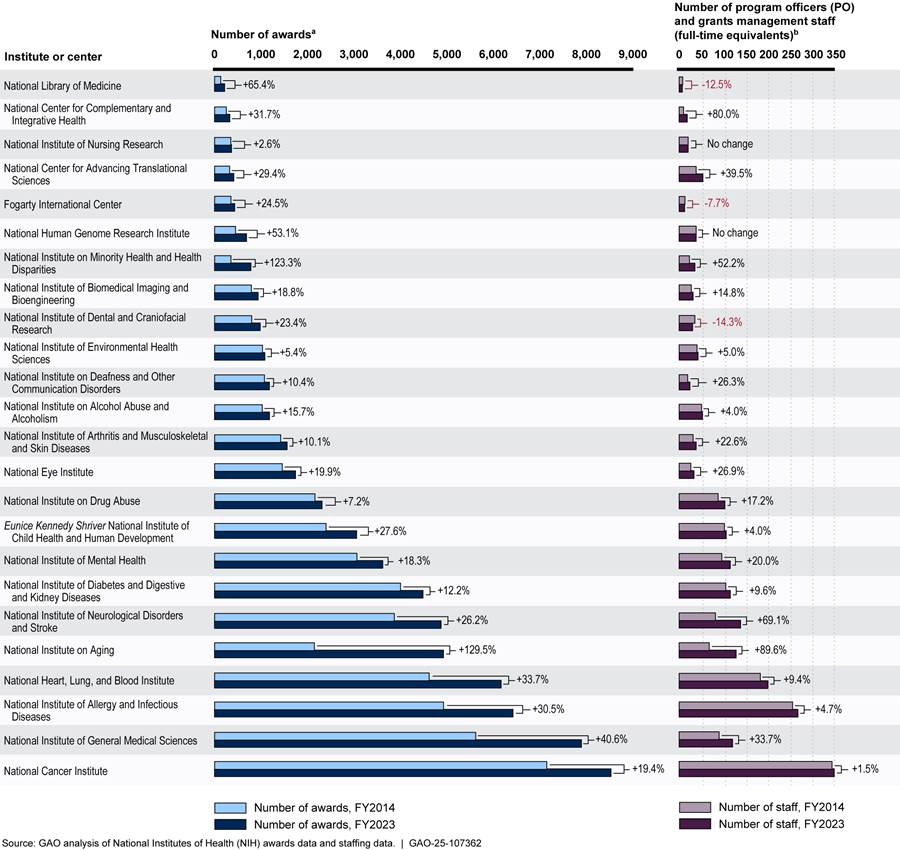

NIH’s inflation-adjusted obligations for extramural research increased by nearly 30 percent from fiscal year 2014 through 2023, consistent with an increase of about 30 percent in the number of extramural awards. The number of oversight staff increased by about 20 percent over the same period. Most ICOs experienced similar patterns of increase for staffing and workload from fiscal year 2014 through 2023, with some variation among them.

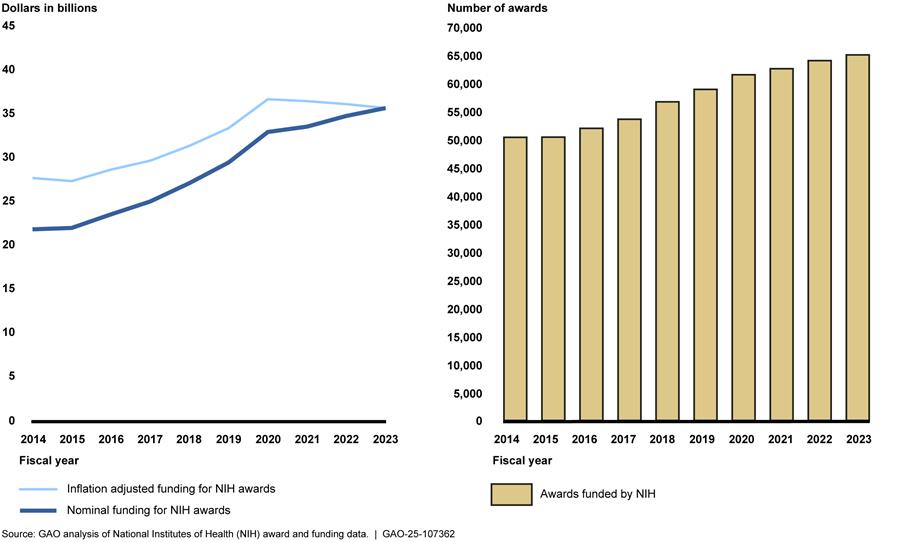

Overall NIH Oversight Staffing Increased Along with Extramural Funding

According to NIH data that we adjusted for inflation to fiscal year 2023 dollars, NIH’s obligations for extramural research increased from $27.7 billion in fiscal year 2014 to $35.7 billion in fiscal year 2023, or by nearly 30 percent (see fig. 1).[7] The inflation-adjusted funding increased most years but leveled off and decreased slightly from fiscal year 2020 through 2023.[8] NIH data show that the number of extramural awards—a measure of NIH’s oversight workload—increased each year, from about 50,000 in fiscal year 2014 to nearly 65,000 in fiscal year 2023, or by nearly 30 percent.

Figure 1: Nominal and Inflation-Adjusted Funding Obligations and Number of NIH Extramural Awards, Fiscal Years 2014-2023

Note: Funding and award data include research project grants, training, construction, and other types of awards but exclude research and development contracts. We used NIH’s Biomedical Research and Development Price Index to adjust for inflation to fiscal year 2023 dollars.

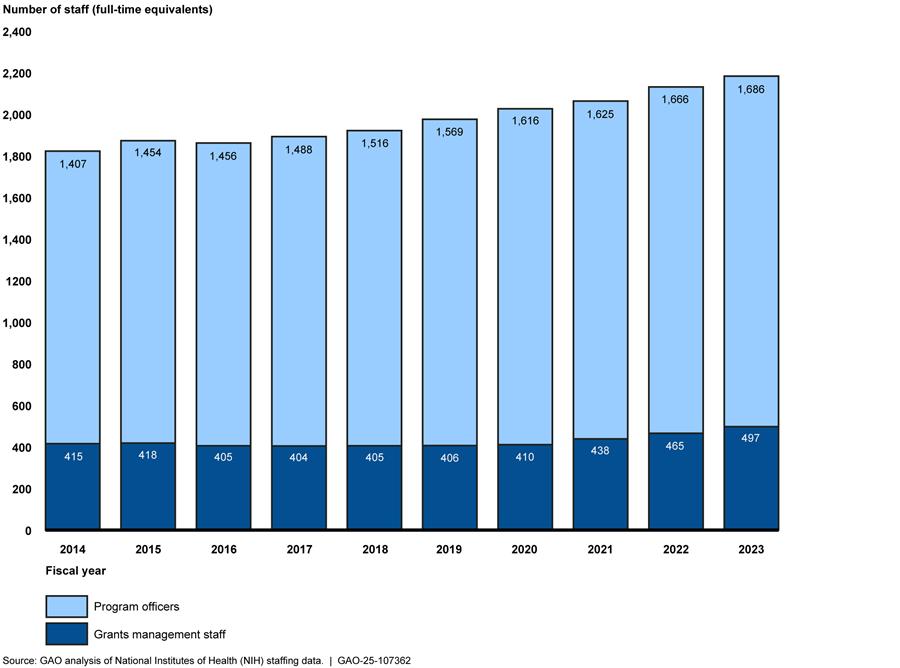

Correspondingly, NIH oversight staffing levels also increased from fiscal year 2014 through 2023, according to data provided by NIH. Combined staffing levels for grants management staff and program officers—the NIH positions with oversight responsibility for extramural research—increased from about 1,800 to 2,200 full-time equivalent positions, or by about 20 percent (see fig. 2).[9] Staffing levels at other parts of NIH with oversight responsibilities varied from fiscal years 2014 to 2023.

· OPERA increased from 19 to 46 full-time equivalent positions, an increase of nearly 150 percent.

· Division of Program Integrity staff conducting reviews of allegations of extramural grants funds misuse decreased from 15 to 13 full-time equivalent positions, a decrease of about 13 percent.

· Division of Financial Advisory Services remained the same at 26 full-time equivalent positions.

The extent of the impact of recent administration actions on NIH oversight staffing levels is unclear. In January 2025, the President issued a memorandum that generally freezes the hiring of federal civilian employees.[10] The President also directed the Director of the Office of Management and Budget to submit a plan to reduce the size of the federal government’s workforce through efficiency improvements and attrition. In February 2025, the President ordered agency heads to promptly undertake preparations to initiate large-scale reductions in force. We requested information in March 2025 about changes, if any, to NIH’s staffing levels as a result of these directives. NIH said they could not provide the information in a timely manner due to competing demands.

Figure 2: Grants Management Staff and Program Officer Staffing Levels at NIH, Fiscal Years 2014-2023

Note: NIH provided actual grants management staff and estimated program officer staffing levels at the 25 NIH institutes, centers, and offices that fund extramural research. NIH officials stated that they were not certain of the total number of program officers because program officers may have the position title of health science administrator, but not all health science administrators are program officers. Grants management staff consist of grants management officers and grants management specialists.

Most NIH Institutes and Centers Also Reported Increases in Awards and Staffing Levels

As shown in figure 3, nearly all ICOs reported an increase in the number of extramural research awards and in oversight staffing between fiscal years 2014 and 2023. For example, the National Institute on Aging, which had the largest percentage increase in the number of awards (about 129 percent), reported an increase in grants management staff and program officers of close to 90 percent. Institute officials stated that this growth was intentional and planned and included an emphasis on recruitment and training.

Unlike the National Institute on Aging, the following two institutes did not have increases in oversight staffing levels proportional to increases in their number of awards:

· The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities saw the number of its awards more than double between fiscal years 2014 and 2023. Over the same 10-year period, its reported grants management and program officer staffing levels increased by about 52 percent, with most of this growth occurring for program officers in fiscal years 2022 and 2023. Institute officials told us that they are working to fill additional staff needs.

· The National Cancer Institute, one of the largest ICOs, had an increase of about 20 percent in the number of awards over the 10-year period with the number of oversight staff remaining almost unchanged (combined grants management staff and program officer staffing increased by about 1.5 percent). Officials at this institute told us that they strive to ensure staffing levels are meeting the demands of the workload and were not aware of any intentional changes in staffing levels for grants management and program officer staff.

Officials from OPERA, the National Cancer Institute, and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities told us that workload is a challenge in post-award oversight. Although the oversight workload increase may not be proportional to the increase in the number of awards, OPERA and National Cancer Institute officials said that the amount of work for staff has increased as the number of awards has grown. Additionally, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities officials noted that workload distribution across the fiscal year is uneven, and because of that they experience intermittent understaffing near the end of the fiscal year.

Figure 3: Change in Number of Awards and Number of Program Officers and Grant Management Staff at NIH Institutes and Centers, Fiscal Years 2014 to 2023

aThe number of awards includes research project grants, training, construction awards, and other types of awards but excludes research and development contracts. We did not include the Office of the Director because it does not directly manage and award grants. NIH officials told us that the Office of the Director funds certain grant programs, such as the NIH Common Fund, and the NIH institutes and centers award and manage the grants.

bNIH provided actual grants management staff and estimated program officer staffing level at the 25 NIH institutes, centers, and offices that fund extramural research. NIH officials stated that they were not certain of the total number of program officers because program officers may have the position title of health science administrator, but not all health science administrators are program officers. Grants management staff consist of grants management officers and grants management specialists.

NIH Has Multiple Layers of Oversight but Has Gaps in Closeout Procedures

NIH oversees extramural research awards by reviewing recipients’ financial reports and progress reports, reviewing government-wide data on current and potential award recipients, and conducting agencywide assessments to identify noncompliance and areas for improvement. However, we found that NIH had not fully ensured award recipients’ timely submission of final reports or performed unilateral closeout of awards.

NIH Monitors Every Award but Has Not Consistently Ensured Timely Submission of Final Reports

NIH grants management staff and program officers provide the first layer of oversight of extramural research awards. Their primary means of doing so is by ensuring recipients file the required financial and scientific progress reports and then evaluating those reports for satisfactory progress and compliance with the terms and conditions of the award.

Grants management staff and program officers from the ICOs review financial reports and scientific progress reports using an electronic checklist. These checklists vary by ICO and include yes-or-no questions and open-ended questions. They cover topics such as whether an award’s terms and conditions from a prior budget period had restrictions, and if so, whether they were acted on appropriately. See table 1 for additional examples from the checklists.

Table 1: Examples of NIH Program Officer and Grants Management Staff Award Review Checklist Question Topics

|

|

Sample question topics |

|

Program officer questions |

· Is award recipient progress satisfactory (based on a narrative describing the progress)? · Has the award recipient provided an acceptable plan to address actual or anticipated challenges and delays? · Has the award recipient proposed a change of major goals and, if so, is it approved? · Are there changes or concerns, such as a significant reduction in level of effort, that require action or documentation? |

|

Grants management staff questions |

· Are there concerns regarding potential accelerated or delayed expenditures? · Have grants management staff confirmed there is no scientific, budgetary, or commitment overlap? · Have grants management staff reviewed the budget and completed a cost analysis? · Does the award recipient have an annual or final progress report due for a prior project period? |

Source: GAO analysis of National Institutes of Health documentation. | GAO‑25‑107362

To identify financial reports and progress reports that have not been submitted by the end of the project period, NIH officials use tools within NIH’s electronic grants management system. NIH sends reminder emails to prompt recipients to submit annual reports. They also send emails 10, 90, 120, and 150 days after the project period end date to remind recipients to submit the required final reports. Failure to submit timely reports may indicate the need for closer monitoring by NIH or may result in award delays or enforcement actions, according to NIH. For example, NIH can delay the funding of the next budget period or reduce the award amount.

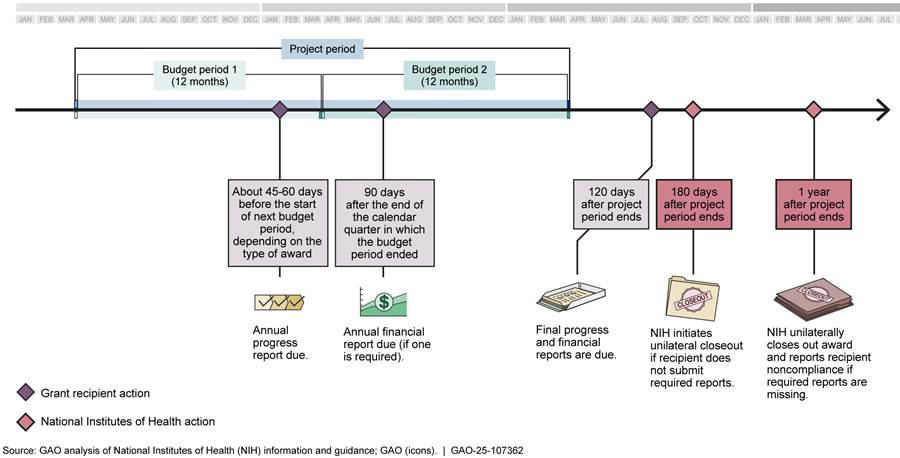

If recipients do not submit final reports within 1 year of the project period’s end date, NIH policy is to unilaterally close out the award. When awards are unilaterally closed out, NIH reports the recipient’s noncompliance to the General Services Administration’s System for Award Management (SAM) and can take enforcement actions such as delaying the recipient’s pending awards.[11] Other federal agencies review referrals to SAM as part of pre-award risk assessment, and such referrals can result in recipients becoming ineligible for a later award from NIH. Additionally, if a final financial report is not submitted, the awarding ICO will close out the award using data from the latest financial report available, which could result in the recipient having to pay back part of the award. Figure 4 provides details about report deadlines and NIH responses to late reports.

Note: Budget periods are usually 12 months, and the length of a project period is determined by the awarding ICO. The two budget periods in the figure are an illustrative example.

OPERA facilitates closeout of awards and monitors awards with delinquent final financial and progress reports through the office’s Closeout Center.[12] OPERA’s closeout standard operating procedure states that the Closeout Center is responsible for helping to ensure submission of final reports. Further, the Center is required to mitigate the potential for unilateral closeout by sending monthly reports to the ICOs identifying awards 150 or more days past their project period end date that have not been closed and do not have all final reports submitted and accepted. However, according to NIH data, there were 1,283 awards with delinquent final financial reports as of September 2024 and 959 awards with delinquent final progress reports as of August 2024. The due dates for these reports ranged from 2015 through 2024. Furthermore, 656 of the 959 awards with delinquent progress reports were more than a year past their project period end dates and had not been unilaterally closed out, as required.[13]

The total delinquency rate across all the ICOs was about 0.2 percent of all awards that should have submitted final reports from January 2014 through August 2024.[14] Two institutes—the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke—accounted for nearly half of the awards with delinquent final progress reports and had delinquency rates of about 0.8 percent.

NIH officials described several efforts to ensure that ICOs unilaterally close out awards. NIH officials stated that they are currently revising the NIH Policy Manual chapter on closeout of NIH grants to more clearly address the required timelines. In addition, NIH officials said that OPERA is now monitoring unilateral closeout actions and has developed a process to issue compliance letters to ICOs that do not meet the policy requirements for closeout.

After our request for delinquent final report data, NIH officials stated that as of December 2024, they closed out over 200 awards from the list they originally provided us and were reviewing the remaining awards to determine appropriate closeout actions. However, these efforts do not address award recipients’ delinquency in submitting financial and progress reports. Moreover, NIH cannot ensure that it will further reduce the delinquency rate because it has not identified the factors that contribute to award recipients submitting final financial and progress reports after the required date.

While delinquent reports are relatively rare, delinquencies that linger over many years without their corresponding awards being closed out indicates a gap in NIH’s oversight process. As a result, some recipients might not be held accountable for delinquent reports when being considered for future awards, and misspent funds from past awards might go undetected.

NIH Uses Government-Wide Data to Supplement Its Monitoring of Awards

A second layer of NIH oversight for extramural research awards is the use of government-wide data to identify high-risk institutions and implement measures to mitigate the risks. To accomplish this, OPERA uses two types of government-wide data on award recipients:

· Single audit data. Recipients that spend $1 million or more in federal awards from federal agencies or programs in a recipient’s fiscal year are required to undergo a single audit, which is an audit covering the entity’s financial statements and federal awards.[15] A single audit may identify deficiencies, known as audit findings, in a recipient’s compliance with award requirements or internal controls. HHS maintains a list of HHS award recipients with negative or potentially negative single audit findings, and OPERA uses this list and updates it for NIH.

· System for Award Management (SAM) data. The General Services Administration maintains SAM.gov, which contains data for all excluded parties (both entities and individuals) that have been disqualified from receiving federal financial assistance for some reason, such as suspension, debarment, proposed debarment, or previous failure to comply with terms and conditions of awards.[16]

Grants management staff within the ICOs review data from these sources as part of their administrative review of awards, according to NIH officials. To aid in the review process, OPERA integrated these data sources into the NIH internal grants management system in November 2023. The system alerts ICO staff if an organization or individual is not eligible for funding or has negative audit findings and prompts staff to coordinate with OPERA to add specific award conditions to an award or take other steps to mitigate risks. For example, NIH can require an award recipient to implement a corrective action plan to address the deficiencies identified in the audit and provide updates to NIH.

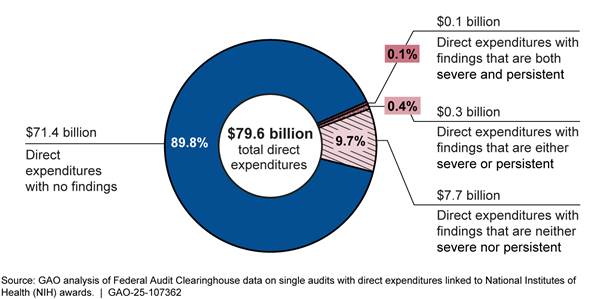

According to our analysis of Federal Audit Clearinghouse data, about 10 percent of the funds that award recipients spent in their fiscal years 2020 through 2022 were linked to one or more single audit findings (see fig. 5).[17] About 0.5 percent of all such expenditures were linked to findings that were severe, persistent, or both.[18] These percentages are low compared to those for all federal awards. Specifically, in an April 2024 report, we found that 16.7 percent of total federal award direct expenditures from recipient fiscal years 2017 through 2021 were linked to severe and persistent findings.[19] See appendix II for examples of severe or persistent single audit findings linked to NIH extramural research award expenditures.

Notes: For the purposes of this report, we define a severe finding as one that the auditor determined contributed to (1) a modified opinion on an audit of compliance with award requirements or (2) a material weakness identified in internal control over compliance. We define a persistent finding as one that is identified in two prior single audits, which has therefore remained unresolved by the recipient’s corrective action for 2 consecutive years.

A direct award is one a federal agency provides directly to a recipient entity that uses the funds. For this report, direct expenditures refer to recipient expenditures of direct award funding.

We performed checks of NIH’s use of SAM and single audit data in three areas, none of which identified a deficiency in NIH’s procedures. Specifically:

· We compared a list of NIH award recipient institutions from fiscal years 2020 through 2023 with the SAM exclusion list and did not find any NIH-funded research institutions on the list.

· We checked for institutions that received at least $750,000 in NIH funding in fiscal years 2019 through 2021 and did not submit a single audit to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse for the audit years 2020 through 2022. We did not identify any.[20]

· We found that NIH’s alert list of award recipients with negative or potentially negative audit findings included the recipients that had severe or persistent single audit findings. In particular, we identified 36 NIH award recipients that had severe or persistent audit findings from audit years 2020 through 2022, and all 36 institutions were on the NIH alert list.

NIH Performs Agencywide Reviews to Identify Noncompliance and Areas for Improvement

At the agency level, NIH works to identify instances of noncompliance, potential policy changes, and corrective actions. To help accomplish this work, NIH conducted three types of reviews of extramural research awards from 2019 through 2024:

· OPERA conducted internal control reviews of awards that received funding from NIH emergency appropriations for COVID-19 response. For example, a 2023 review sampled 60 extramural awards issued in fiscal year 2022 and resulted in revisions to six awards’ terms that did not include the correct COVID-specific terms.

· The Office of Management Assessment conducted assessments related to extramural research awards. For example, according to NIH, an assessment from June 2024 led to the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences implementing a training program and increasing organizational awareness of fraud risks.

· The Office of Management Assessment conducted improper payment assessments, including assessments of extramural research funding at eight ICOs in fiscal year 2023.[21] According to NIH officials, the assessments found that the extramural programs were not susceptible to significant improper payments.

NIH Addresses Carryover of Unused Funds, but Guidance Is Incomplete

NIH has policies that authorize grants management staff to determine whether to limit award recipients’ carryover of unused funds from one budget period to the next or to adjust funding levels. We found that the use of these policies is inconsistent and that NIH’s guidance to the ICOs is incomplete.

NIH Has Several Methods to Address Carryover, but ICOs Differ in Their Use

Under HHS policy, within the project period of certain grants, projects may carry over certain unused funds at the end of the budget period into the next budget period. Award recipients can automatically carry over funds on most grants and do not have to request approval from NIH.[22] However, according to the NIH Grants Policy Statement, if an award recipient anticipates having an unused balance greater than 25 percent of the current budget period’s total approved budget, the grants management staff will review the circumstances resulting in the balance to ensure that these funds are necessary to complete the project, and may request additional information from the recipient, including a revised budget, as part of the review. NIH officials told us that one common justification for carryover at the end of a budget period is recruitment and hiring challenges faced by the award recipient, which can lead to delays in conducting the research.

If a grants management officer determines that some or all of the unused funds are not needed to complete the project, the NIH Grants Policy Statement allows them to restrict the recipient’s authority to automatically carry over unobligated balances in the future. For example, officials at the National Eye Institute said that they may restrict carryover if the recipient provides the same justification as in previous years. NIH may implement such restrictions through offsets, in which unused funds are subtracted from funds awarded in the new budget period. If grants management staff determine that a recipient has a need for unused funds, they may apply a mid-project extension whereby issuance of funds for a new budget period is delayed to give the recipient more time to spend down their unused balance. They may also restructure the project’s award to change its timeline or redistribute funds to later years.

NIH officials said that they did not have agencywide guidance for using these options for addressing unused funds because they preferred to leave these decisions to individual ICOs. As a result, procedures on use of these options varied across the selected ICOs. For example, documentation from the National Eye Institute only referred to offsetting or restricting future carryover authority and did not include options like budget restructuring. National Cancer Institute documentation described situations in which restructuring an award, granting a mid-project extension, or offsetting may be appropriate.

Without agencywide information, the four NIH ICOs we selected differed in how they managed carryover. Officials from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities stated that they typically use offsets, as appropriate. In contrast, officials at National Institute on Aging said that they typically use mid-project extensions when approving carryover requests because they have found that offsets lead to unanticipated project delays. Officials at the National Cancer Institute said that they may use offsets or restructure the award timeline as they deem appropriate. These officials added that it is more common to allow full carryover or to restructure an award to give the recipient more time to expend the full amount of funding, but that offsets may be more common with certain types of research, such as more complex clinical trial studies, or when recipients cannot provide a sufficient justification for carryover.

According to the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should implement control activities through policies, which can include periodically reviewing policies for continued relevance and effectiveness in achieving objectives.[23] While its policy allows for flexibility in how ICOs manage carryover, NIH has not conducted an analysis of the differing methods the ICOs choose to use in different situations. Such situations are common according to our analysis of NIH’s fiscal year 2023 grant monitoring records. In particular, we found that award recipients anticipated having an unused balance of more than 25 percent in at least 12,000 awards, or nearly a fifth of all ongoing NIH awards during that fiscal year.[24] An analysis of options for addressing unused funds could help NIH develop more comprehensive information that would help ensure that the ICOs are implementing carryover polices effectively.

NIH Does Not Require Institutes and Centers to Track Unused Balances Across Portfolios

NIH’s Grants Policy Statement requires recipients to indicate if unused balances are expected on certain individual awards. In particular, it requires that a recipient submit an explanation and spending plan for an unused balance of more than 25 percent of the award for a budget period. According to the Grants Policy Statement, grants management staff may request additional information, including a revised budget. NIH uses this to evaluate whether to continue funding or adjust an award.

The ICOs, however, varied in how they track unused balances across their award portfolios. Among the four selected ICOs, only the National Cancer Institute tracked the extent to which it carried over unused balances for its entire portfolio of research project grants. For instance, National Cancer Institute officials provided data showing that, for fiscal years 2021 through 2023, the institute used offsets to reduce carryover by an annual average of $81.3 million across more than 4,000 research project grants.[25] National Eye Institute officials stated that they track such information for some types of funding, such as institutional training grants. National Institute on Aging officials stated that they may use mid-project extensions to manage carryover requests and track some information about their use through NIH’s electronic grant administration system. Officials at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities stated that they track offsets, extensions, and restructuring of individual grants but do not summarize those data across their portfolio of awards.

According to the Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[26] Because the ICOs do not consistently track the carryover of unused funds, some ICOs may not have complete information on how well they set funding levels to match award recipients’ needs. Having such information could allow grants management staff and program officers to award appropriate funding levels, enabling ICOs to ensure that they are implementing carryover practices effectively, and helping NIH to fund as many deserving awards as funding allows.

NIH Seeks to Identify and Recover Disallowed Costs

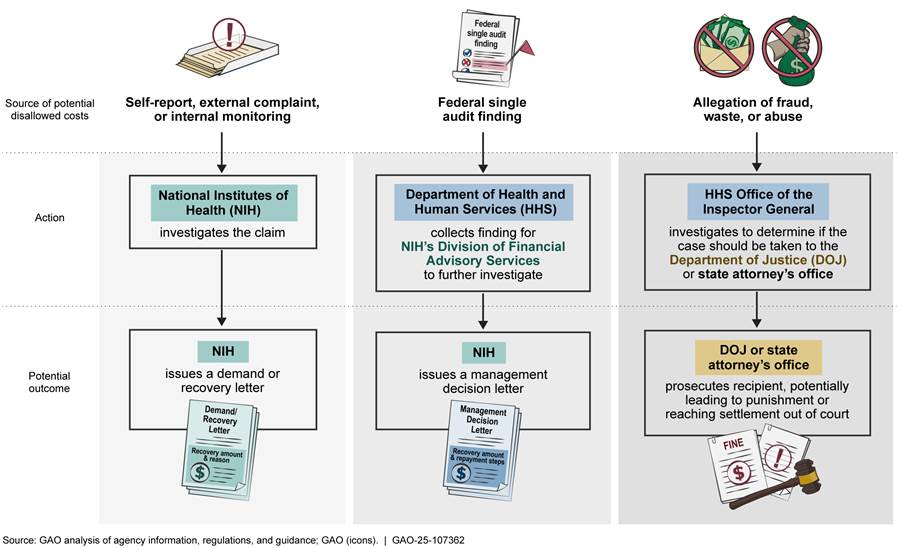

Disallowed costs are awarded funds that the recipients have used in a manner that is inconsistent with federal law or award terms and conditions.[27] As shown in figure 6, there are various ways NIH can learn about and recover potential disallowed costs, including external complaints, internal agency monitoring, and the findings of external audits. In addition, the HHS Office of Inspector General investigates allegations of fraud, waste, and abuse.

Self-report, external complaint, or internal monitoring. NIH can identify disallowed costs through recipient self-reporting and external complaints. Recipients can self-report when they identify a problem, such as from university research integrity offices or workers in the recipient’s lab, who may report instances of research misconduct, nondisclosure of foreign support, nondisclosure of financial conflicts of interest, or accounting errors. Within NIH, the awarding ICOs, the Office of Management Assessment’s Division of Program Integrity, or the Extramural Research Integrity Officer may identify and investigate disallowed costs.[28]

If NIH determines that there are disallowed costs, it issues a letter to the recipient specifying the amount NIH is seeking to recover.[29] Following receipt of the letter, the award recipient must either repay the stated amount within a certain time frame or appeal the decision and provide further information explaining why the cost should be allowed.

According to NIH, it issued five demand letters and 51 recovery letters from fiscal year 2021 through 2023 (see table 2). The five demand letters identified a total of $4.0 million in funds for recovery, of which NIH recovered $3.9 million. The 51 recovery letters identified $26.0 million in funds for recovery, of which NIH recovered $25.8 million.[30] Research misconduct accounted for the largest amount of recovered money—$8.0 million in recovered costs among 12 cases.[31] In one such case, NIH identified and recovered $1.7 million after it found that an associate professor at a university had falsified or fabricated data, results, and other key aspects of multiple papers, reports, and applications. Grant overlap was the most common reason for disallowed costs, accounting for 22 of the 56 letters and $6.5 million in disallowed costs recovered.[32] For example, NIH identified and recovered about $250,000 in disallowed costs from a recipient who had scientific and budgetary overlap between two grants for which the applications contained nearly identical language.

Table 2: Disallowed Costs Identified and Recovered by NIH, by Reasons for Recovery, in Fiscal Years 2021 through 2023

Dollars in millions

|

Reason for disallowed costs |

Number of NIH |

Amount identified |

Actual amount |

|

Grant overlapa |

22 |

$6.5 |

$6.5 |

|

Research misconduct |

12 |

$8.2 |

$8.0 |

|

Nondisclosure of foreign or other additional support |

9 |

$6.5 |

$6.5 |

|

Excess charges made to grant account |

3 |

$3.9 |

$3.9 |

|

Financial conflict of interest |

2 |

$1.6 |

$1.6 |

|

Otherb |

8 |

$3.3 |

$3.2 |

|

Total |

56 |

$30.0 |

$29.7 |

Source: GAO analysis of National Institutes of Health (NIH) demand and recovery letters and related data. | GAO‑25‑107362

aGrant overlap generally consists of three categories: (1) scientific overlap such as when substantially the same research is proposed in more than one application; (2) budgetary overlap, where duplicate or equivalent budgetary items such as equipment or salary are requested in an application while already being provided by another source; and (3) commitment overlap, where an individual’s time commitment exceeds 100 percent of full-time employment for 12 months.

bWe classified a reason as “other” if there was only a single instance of it in fiscal years 2021 through 2023 or if the letter did not specify a reason. Reasons found under this category include accounting errors, change in principal investigator status, and lapse in animal welfare assurance.

Single audit findings. NIH can also identify disallowed costs through findings from single audits of a recipient’s financial statements. An independent auditor (typically either a private firm engaged by the recipient or a state or local government audit agency) issues a single audit report that may contain findings. Such findings may describe potential problems with the recipient’s records, activities, or use of funds that may be associated with a questioned cost.[33] Within NIH, the Division of Financial Advisory Services is responsible for receiving and reviewing single audit findings. Auditors from the division can then request additional documentation from award recipients to determine whether all or a portion of a questioned cost should be considered a disallowed cost. If a recipient is unwilling or unable to correct deficiencies or return funds within a reasonable amount of time, the division will issue an interim management decision letter to the award recipient outlining, among other things, the recovery amount and reason for the recovery.[34]

For fiscal years 2021 through 2023, NIH resolved 76 questioned costs from 56 single audits, according to NIH-provided data. These single audit findings resulted in $9.3 million in questioned costs among NIH awardees. Of this amount, the division determined that $3.3 million in costs should be disallowed, and it recovered that full amount. According to division officials, common reasons for questioned costs included timesheets without supervisory approval, late submissions of federal financial reports, and lack of adherence to NIH cash management policies. For example, the division found that a recipient had not followed NIH cash management policies to separate funds received from other grants, resulting in a disallowed cost of more than $160,000.

Fraud, waste, and abuse allegations. Disallowed costs may be identified from allegations of fraud, waste, and abuse to the HHS Office of Inspector General.[35] According to Office of Inspector General officials, they receive allegations from NIH and other HHS operating divisions; institutions; or whistleblowers, who may come from within NIH or the recipient institutions. In fiscal years 2021 through 2023, NIH referred a total of seven complaints to the HHS Office of Inspector General. Four of these complaints identified potential instances of fraud, while the remaining three identified issues related to contracting conflicts of interest and ethics violations, the misuse of contract funds, or issues submitted to the Office of Management Assessment that were outside of its purview.

The HHS Office of Inspector General conducts criminal, civil, and administrative investigations, potentially leading to the recovery of disallowed costs. For example, an Office of Inspector General investigation from 2021 found that a former employee and NIH award recipient had improperly submitted claims to several NIH awards. The Office of Inspector General determined, among other things, that these payments were disallowed because they were either made without sufficient documentation of whether the activities were for the performance of the awards, or because they were made to entities with which the recipient had an undisclosed conflict of interest. The recipient institution agreed to pay $1.5 million for the violation. HHS Office of Inspector General officials stated that, as of September 2024, they had a total of 49 pending cases involving NIH grants and contracts, of which 22 were criminal and 27 were civil cases.

The Office of Inspector General can also present cases to the Department of Justice—the primary federal agency for prosecuting criminal and civil cases. The Department of Justice will conduct the investigation in tandem with the HHS Office of Inspector General.[36] For example, in a 2023 case, the Department of Justice found that a researcher had committed fraud by lying to federal authorities about affiliations with Chinese funding sources and that he had failed to report income from these sources. The case resulted in a sentence of 6 months of home confinement, a fine of $50,000, and $33,600 in restitution to the Internal Revenue Service, among other penalties.

Conclusions

NIH’s ability to oversee its extramural research funding is critical to its mission of advancing scientific knowledge. NIH’s approximately 2,200 extramural research oversight staff follow agencywide and ICO-specific policies and procedures to perform individual reviews of awards and ensure recipients comply with requirements. However, we found three areas for improvement.

First, for a small number of awards over the past 10 years, NIH did not receive required final reports or meet the NIH requirement to close out awards by a year after the end of the research project. This deficiency might erode accountability for incomplete reporting, and it might allow recipients to spend funds inappropriately without being detected. Second, NIH allows several options for ICOs to manage recipients’ carryover of unused grant funds but does not provide informational resources that could help ICOs determine the most effective option for doing so. Without such resources, NIH may be missing opportunities to further ensure that the ICOs are using the most effective option to manage unused funds. Third, ICOs did not consistently track unused balances across their award portfolios. Having information on unused balances across their research portfolios could allow grants management staff and program officers to award appropriate funding levels, enabling existing grants to achieve their objectives and helping NIH to fund as many higher value projects as funding allows.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to NIH:

· The Director of NIH should identify the contributing factors to delinquent final financial and progress reports and address these factors in revised guidance. (Recommendation 1)

· The Director of NIH should analyze how NIH institutes, centers, and offices use offsets, extensions, and budget restructuring to manage unused balances for projects at the end of the funding period and develop an informational resource on the benefits and risks of each method. (Recommendation 2)

· The Director of NIH should require that its institutes, centers, and offices track award recipients’ unused balances across their respective award portfolios. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. HHS provided written comments, which are reproduced in appendix III. In its comments, HHS stated that NIH concurred with our recommendations and described the steps that NIH will take to implement them. HHS also provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

As agreed with your offices, unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at BenedictH@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Hilary M. Benedict

Acting Director, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

List of Requesters

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Earl L. “Buddy” Carter

Chairman

Subcommittee on Health

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Gary Palmer

Chairman

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Morgan Griffith

House of Representatives

This report (1) describes trends in National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding and oversight staffing for extramural research from fiscal year 2014 through 2023, (2) assesses the extent to which NIH policies and procedures for oversight of extramural research awards ensure award recipients’ appropriate use of funds, (3) assesses NIH’s policies and procedures for limiting carryover of unused funds on extramural awards, and (4) assesses the extent to which NIH identified and recovered disallowed costs from extramural award recipients in fiscal years 2021 through 2023.

The scope of our review included the 25 NIH institutes, centers, and offices (ICO) that fund extramural research as well as NIH offices with responsibility for extramural research oversight. These included the Office of Extramural Research (OER), the Division of Financial Advisory Services, and OER’s Office of Policy for Extramural Research Administration (OPERA) and Office of eRA.[37]

For all our objectives, we reviewed the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Grants Policy and Administration Manual, the NIH Grants Policy Statement, and portions of the NIH Policy Manual relevant to research awards. As needed, we reviewed other relevant NIH policies and procedures, such as those regarding delinquent final financial and progress reports and the identification and recovery of potential disallowed costs through external audits and investigations of allegations of fraud, waste, and abuse. We also reviewed the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB) government-wide Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements (Uniform Guidance).[38]

We interviewed NIH officials knowledgeable about extramural research oversight, including officials from OER, OPERA, Office of eRA, and the Division of Financial Advisory Services. In addition, we interviewed officials and reviewed documents from a subset of the 25 NIH ICOs that make awards for extramural research. We selected four NIH institutes—the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, and the National Eye Institute—to obtain a diversity of views based on factors such as funding, staffing, and mission. These four institutes accounted for about 25 percent of all NIH research grants awarded in fiscal year 2023. The information we obtained from these four institutes was not generalizable to NIH’s other ICOs but provided context and examples for NIH-wide oversight of extramural research awards. We also reviewed relevant reports and interviewed officials from HHS’s Office of Inspector General about their findings related to NIH’s oversight of extramural research awards.

To describe trends in NIH funding for extramural research from fiscal year 2014 through 2023, we downloaded extramural research funding and award data, by ICO, from NIH’s publicly available Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT). According to NIH officials, the funding amounts in RePORT represent the total obligated amount authorized for an award’s budget period. These data included research project grants, training, and construction, and other types of awards. We excluded research and development contracts because they accounted for about 2.1 percent or less of NIH’s extramural research awards in each year from fiscal years 2014 to 2023. We used NIH’s Biomedical Research and Development Price Index to adjust the funding data for inflation.[39] To assess the reliability of the funding and award data, we reviewed background information on RePORT and written responses from NIH to our questions about the data, and we provided our search parameters and resulting data to NIH for confirmation. We also compared fiscal year 2022 funding amounts in RePORT with data from the National Science Foundation in its Survey of Federal Funds for Research and Development.[40] We determined that the RePORT data were sufficiently reliable for describing trends in NIH extramural research funding and number of awards.

We obtained data on grants management staff and program officers for all NIH institutes and centers that award extramural research grants. According to NIH officials, the data for grants management staff included grants management officers and specialists, and the data for program officers included positions with differing names, such as health science administrator, that performed similar functions. NIH also provided fiscal year 2014 through 2023 staffing levels for other parts of NIH responsible for overseeing extramural research, including OPERA, the Division of Program Integrity, and the Division of Financial Advisory Services. To assess the reliability of the staffing data, we reviewed background information on NIH’s system for managing staffing data and written responses from NIH to our questions about the data, and we interviewed four selected ICOs about their staffing numbers. We also compared data for program officers with RePORT data and discussed differences in the data sources with NIH officials. In response, NIH provided revised data on the number of project officers. We determined that the NIH-provided data were sufficiently reliable for describing trends in oversight staffing.

To assess the extent to which NIH policies and procedures for oversight of extramural research awards ensure award recipients’ appropriate use of funds, we reviewed documents and systems that NIH uses as part of award oversight. These included checklists that ICOs use to review award recipients’ financial and scientific progress reports; policies and procedures for delinquent reports; and policies and procedures for checking for award recipients that have negative single audit findings or that are suspended or debarred from eligibility to receive NIH awards. In addition, we examined NIH’s agencywide reviews of extramural research that NIH performed from 2019 through 2024, including reviews by OPERA and the Office of Management Assessment.

We also performed several checks on documents and data we obtained from NIH and other sources:

· We obtained data on delinquent financial reports and progress reports with due dates from 2015 to August 2024 from NIH. We compared these data with award information from NIH’s RePORT Expenditures and Results (RePORTER) tool to calculate delinquency rates for each ICO.[41] After performing a spot check of the data and obtaining written responses regarding edit checks, quality control, and data limitations with NIH officials, we determined that delinquency data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report.

· We downloaded a list of institutions that had been suspended or debarred from federal awards in 2020 through 2024 from the System for Award Management (SAM). We compared the excluded entities on that list with data from RePORT on award recipients that received NIH awards during those years.

· To evaluate NIH’s use of single audit findings stored in the Federal Audit Clearinghouse, we analyzed 2,204 single audit reports from 2020 to 2022 for institutions that expended funds from NIH awards and determined the total amount of NIH-funded expenditures associated with severe and persistent single audit findings. We analyzed reports from audit years 2020 through 2022 because those were years we could access complete data from GAO’s Federal Audit Clearinghouse Exploration Tool, a digital tool that allows for accessing Federal Audit Clearinghouse data. We also compared a list of institutions that received severe and persistent single audit findings with a list of award recipients on NIH’s alert list of high-risk recipients. We determined that the data we obtained from the Federal Audit Clearinghouse were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report.

· We also assessed whether there were any institutions that received at least $750,000 in one year from NIH but did not submit a single audit report to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse.[42] We compared institutions that submitted audit reports to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse from 2020 to 2022 with NIH funding data from RePORTER. We did not analyze data from institutions that received less than $750,000 in one year from NIH but may have received and expended that amount from all federal sources combined.

To assess NIH’s policies and procedures for limiting carryover of unused funds, we reviewed documentation from and conducted interviews with NIH and selected ICOs regarding carryover of unused funds. We compared this information to two principles of internal control that we determined were significant to this objective. These included the principle that management should implement control activities through policies and that management should use quality information to achieve the entity’s objective.[43] We obtained data on unused funds from fiscal year 2021 through 2023 from the National Cancer Institute—the one ICO that had such data. Through interviews, we determined that the three other ICOs we selected did not track their unused balances across their award portfolios in a similar away. We also analyzed NIH data across all ICOs except for the National Cancer Institute—which collects such data in a separate system—to determine the number award recipients in fiscal year 2023 that anticipated having an unused balance of greater than 25 percent.

To assess the extent to which NIH identified and recovered disallowed costs in fiscal years 2021 through 2023, we reviewed documentation from and interviewed officials from NIH and selected ICOs about how they identify questioned costs and recover disallowed costs. NIH also provided a copy of 56 demand and recovery letters they sent from fiscal year 2021 through 2023. We reviewed the letters and categorized the reasons for the disallowed costs. To assess the reliability of the NIH-identified disallowed costs, we compared the amounts sought in the demand and recovery letters and the amounts in a record of disallowed costs maintained by NIH. We found a few discrepancies that NIH resolved. NIH’s Division of Financial Advisory Services provided a list of 76 questioned costs for fiscal year 2021 through 2023 that NIH sought to recover. To assess the reliability of these data, we conducted spot checks and noted some discrepancies that NIH was able to resolve. We determined that the NIH data were sufficiently reliable for reporting on the total amount of disallowed costs in fiscal years 2021 through 2023. We also interviewed and obtained written answers to questions from officials from the HHS Office of Inspector General about their role in recovering disallowed costs following their investigating allegations of fraud, waste, and abuse related to NIH extramural grants.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to April 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

A single audit report stored in the Federal Audit Clearinghouse may identify deficiencies, known as findings, in a recipient’s compliance with award requirements, accounting standards for financial reporting, or internal controls. Table 3 shows the number of severe or persistent single audit findings linked to direct expenditures from National Institutes of Health extramural research awards from 2020 through 2022.

Table 3: Compliance Areas of Severe or Persistent Single Audit Findings Linked to Direct Expenditures of National Institutes of Health Awards, 2020 to 2022

|

Compliance areaa |

Number of findings |

Example of severe or persistent findings |

|

Allowable costs/cost principles |

44 |

Not properly reconciling credit card statements to the general ledger, resulting in a material dollar amount of expenses not being recorded in the accounting records at year-end |

|

Activities allowed or unallowed |

32 |

Not maintaining adequate documentation to support expenditures |

|

Special tests and provisions |

17 |

Key personnel’s effort did not equal the effort reported to the awarding federal agency, and there was no evidence of prior approval from the awarding federal agency for change in key personnel |

|

Procurement and suspension and debarment |

13 |

No written procurement policy in place that covers the federal procurement requirements |

|

Subrecipient monitoring |

12 |

Auditors could not ascertain that the recipient institution verified that subrecipients had been audited as required |

|

Cash management |

11 |

Not having controls to ensure that incurred costs had been paid before an invoice to the awarding federal agency is issued |

|

Period of performance (or availability) of Federal funds |

7 |

Expenditures incurred after the end of the period of performance |

|

Other |

6 |

Not having properly performed management review of compliance requirements |

|

Equipment and real property management |

5 |

Not properly tagging federally funded equipment to indicate federal ownership |

|

Reporting |

4 |

List of recipient expenditures did not reflect the federal expenses incurred |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Audit Clearinghouse data. | GAO‑25‑107362

Note: Some findings are linked to multiple compliance requirements.

aCompliance areas are defined in 2 CFR Part 200, Appendix XI, OMB Compliance Supplement. The Compliance Supplement is an annually updated authoritative source for auditors that identifies existing important compliance requirements that the federal government expects to be considered as part of a single audit. 2 C.F.R. 200.1.

GAO Contact

Hilary M. Benedict, BenedictH@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Joseph Cook (Assistant Director), Arvin Wu (Analyst-in-Charge), Jenny Chanley, Justin Cubilo, Elena Granowsky, Ryan Han, Megan Harries, Won (Danny) Lee, Angela Marler, Ben Shouse, and Ashley Stewart made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]In this report, we use the term “award” to refer to extramural research under grants and cooperative agreements and to exclude contracts. We excluded contracts because they made up 2.1 percent or less of NIH’s extramural research funding in each year from fiscal years 2014 to 2023. In addition, contracts are not part of institute, center, and office (ICO) extramural oversight workload, according to NIH officials.

[2]NIH is organized into 27 institutes and centers, which have their own mission and functions, separate appropriations, and statutory authorities. Twenty-four of these institutes and centers and NIH’s Office of the Director fund extramural research.

[3]NIH refers to program officers by additional titles, such as program officials and project officers. In this report, we use the term “program officer” to include all these positions. We use the term “grants management staff” to include grants management officers and grants management specialists. Both positions are responsible for the business aspects of grants and cooperative agreements, and grants management officers also have the authority to obligate NIH expenditure of funds and permit changes to approved projects.

[4]NIH previously used eRA as an abbreviation for “electronics Record Administration,” which was part of an NIH initiative in the 1990s to improve access to federal grants through the internet.

[5]Recent reports by GAO and HHS’s Office of Inspector General have examined NIH’s oversight of extramural award recipients. For example, see GAO, NIH Could Take Additional Actions to Manage Risks Involving Foreign Subrecipients, GAO‑23‑106119 (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 14, 2023) and HHS Office of Inspector General, The National Institutes of Health Could Improve Its Post-Award Process for the Oversight and Monitoring of Grant Awards, A-03-20-03001 (Washington, D.C.: February 2022).

[6]OMB’s Uniform Guidance is reprinted in 2 C.F.R. part 200, and HHS’s related regulations incorporating OMB’s Uniform Guidance are codified in 45 C.F.R. part 75. See 2 C.F.R. § 300.1.

[7]We obtained funding amounts from NIH’s publicly available Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT), which represent the total obligated amount authorized for an award’s budget period, according to NIH. These funding amounts include research project grants, training, construction, and other types of awards. We excluded research and development contracts because they account for about 2.1 percent or less of NIH’s extramural research funding in each year from fiscal years 2014 to 2023.

[8]We used the Biomedical Research and Development Price Index to adjust for inflation. This index estimates changes in the prices of personnel services, supplies, and equipment purchased with NIH-issued awards to support biomedical research. The Bureau of Economic Analysis in the Department of Commerce updates the index annually under an interagency agreement with the NIH. When not adjusted for inflation, NIH’s funding for extramural research increased every year from $21.8 billion in fiscal year 2014 to $35.7 billion in fiscal year 2023.

[9]NIH officials stated that they were not certain of the total number of program officers because individuals with differing job titles, such as health science administrator, can fill those positions. NIH stated that the agency is undertaking a project for more consistent titling to assist with reporting.

[10]This does not apply to military personnel of the armed forces or to positions related to immigration enforcement, national security, or public safety.

[11]NIH issued policy notice NOT-OD-24-055 on January 23, 2024, to alert the NIH extramural community that NIH was strengthening enforcement of its longstanding closeout policies, including reporting all unilateral closeouts to SAM.gov.

[12]For the purposes of this report, final financial reports and final progress reports are considered delinquent if they were not submitted within 120 calendar days of the end of the project period end date.

[13]See NIH Grants Policy Statement section 8.6 referencing OMB’s Uniform Guidance requiring NIH to make “every effort” to close out awards within 1 year after a project ends. 2 C.F.R. § 200.344.

[14]We estimated the delinquency rate by dividing the number of delinquent progress reports by the number of NIH extramural research awards that were 120 days or more past their project end dates during that time frame, of which there were nearly 426,000. We did not take into consideration if any of the awards with delinquent reports had any extensions provided for their reporting deadlines.

[15]31 U.S.C. § 7502(a)(1); 2 C.F.R. § 200.501. In April 2024, OMB issued revisions to the Uniform Guidance, including 2 C.F.R. § 200.501 raising the threshold of annual expenditures from $750,000 (the amount applicable during our audit period) to $1 million, effective for federal awards issued beginning October 1, 2024. 89 Fed. Reg. 30,046 (Apr. 22, 2024). The Single Audit Act requires nonfederal entities that expend above a certain amount in federal awards in a fiscal year to undergo a single audit—an audit of an entity’s financial statements and federal awards—or in select cases a program-specific audit.

[16]NIH follows HHS’s regulations for non-procurement transactions (codified at 2 C.F.R. part 376) that implement OMB’s government-wide debarment and suspension system guidance (reprinted in 2 C.F.R. part 180).

[17]The Federal Audit Clearinghouse is an internet-based repository of record that stores single audit reporting packages and related data. 31 U.S.C. § 7502(h); 2 C.F.R. § 200.512; and 45 C.F.R. § 75.512. It is currently administered by the General Services Administration, as designated by OMB.

[18]For this report, we define a severe finding as one that the auditor determined contributed to (1) a modified opinion on a compliance audit or (2) a material weakness on an internal control audit. We define a persistent finding as one that two consecutive prior audits have identified.

[19]GAO, Single Audits: Improving Federal Audit Clearinghouse Information and Usability Could Strengthen Federal Award Oversight, GAO‑24‑106173 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 22, 2024).

[20]The 12 months covered by a recipient’s single audit, referred to as the audit year, align with the recipient’s fiscal year, which may differ from the federal fiscal year. We checked entities that received at least $750,000 in NIH funding in a fiscal year because the $1,000,000 expenditure threshold was not in effect for awards issued prior to October 2024. Because the single audit threshold is based on a recipient’s expenditure and not its receipt of federal funds, some recipients may correctly have not submitted a single audit reporting package to the Federal Audit Clearinghouse because they did not spend at least $750,000 in their fiscal year (the applicable expenditure threshold during our audit period).

[21]The Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 (PIIA) defines improper payments as those payments that should not have been made or were made in an incorrect amount, including overpayments and underpayments under statutory, contractual, administrative, or other legally applicable requirements. PIIA further states that this definition includes any payment to an ineligible recipient, any payment for an ineligible good or service, any duplicate payment, any payment for a good or service not received (except for such payments where authorized by law), and any payment that does not account for credit for applicable discounts. See PIIA, Pub. L. No. 116-117, 134 Stat. 113, 114 (Mar. 2, 2020), codified at 31 U.S.C. § 3351(4).

[22]Examples of awards that do not include automatic carryover include cooperative agreements, awards to individuals, and clinical trials.

[23]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014).

[24]The estimate of 12,000 awards anticipated to have an unused balance of more than 25 percent is likely a conservative estimate because it does not include data from the National Cancer Institute, which uses a separate data system to track such data.

[25]Nominal extramural research funding amounts for the National Cancer Institute ranged from $4.0 to $4.6 billion during fiscal year 2021 through 2023.

[27]2 C.F.R. § 200.1; 45 C.F.R. § 75.2.

[28]The HHS Office of Research Integrity can also conduct allegation assessments and forward allegations to the appropriate HHS component, such as NIH, for inquiry or investigation and potential recovery of funds.

[29]According to NIH officials, demand letters are issued in cases where the disallowed cost is officially considered a debt to the federal government, such as when two duplicate grant applications are fully funded. Recovery letters are issued in cases of foreign interference, research misconduct, and harassment, among other things. NIH officials stated that amounts owed that are identified in recovery letters are not considered a debt to the federal government and, therefore, that NIH has greater freedom to negotiate with recipients in these cases.

[30]NIH officials attributed the difference between the amount identified for recovery and the amount actually recovered to various circumstances. For example, not all funds had been drawn down by one recipient at the time of recovery, so the recipient only returned what they had expended—an amount that was lower than that sought by NIH.