FEDERAL HIGHWAYS

DOT Should Improve Communications on Its Cost-Effectiveness Tool for Emissions Reductions

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Elizabeth Repko at RepkoE@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107366, a report to congressional committees

DOT Should Improve Communications on Its Cost-Effectiveness Tool for Emissions Reductions

Why GAO Did This Study

Cars, trucks, and other vehicles can emit air pollutants harmful to human health. CMAQ supports projects in areas that do not currently, or did not in the past, meet federal air quality standards for certain air pollutants—carbon monoxide, ozone, or particulate matter. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provided about $2.7 billion for CMAQ in fiscal year 2025 and authorized about $2.7 billion for fiscal year 2026. While DOT created tools—cost-effectiveness tables and emissions calculators—to help states evaluate CMAQ projects, DOT has not tracked data on the use of these tools by states.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act includes a provision for GAO to review CMAQ. This report discusses, among other issues, (1) how states have used CMAQ funds, (2) the cost effectiveness of CMAQ projects at reducing emissions, and (3) the extent to which DOT has communicated to states about tools for evaluating CMAQ projects. GAO analyzed DOT project data for fiscal years 2015 through 2023 and DOT financial data for fiscal years 2015 through 2024, the most recent years for which data were available. GAO also interviewed agency officials, reviewed DOT CMAQ documents, and surveyed the 50 states and Washington, D.C. on FHWA’s CMAQ tools. GAO assessed DOT’s communication of its tools against federal internal control standards.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that DOT provide ongoing and formal communications about its CMAQ cost-effectiveness tables.

DOT agreed with our recommendation.

What GAO Found

Since 1991, the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) has provided funding to states through a statutory formula; this funding is for transportation projects that aim to reduce congestion and improve air quality. GAO found that during fiscal years 2015 through 2023, states spent between $900 million and $1.9 billion annually to start about 700 to 1,200 new CMAQ projects. About 80 percent of projects were for transit improvement, traffic flow improvement, and bicycle and pedestrian projects (see figure).

DOT published tables in 2020 to assist states in evaluating the cost effectiveness (in terms of median cost per ton of emissions reduced) of 21 types of CMAQ projects. Using these tables for projects started in fiscal years 2015 through 2023, GAO found that 88 percent of projects, and 82 percent of their costs, were in project types rated by DOT as having mixed or weak cost effectiveness in reducing emissions. States have discretion in selecting projects, and factors, including regional priorities, may affect the cost effectiveness of those projects. For example, a state may use CMAQ funds on bicycle and pedestrian projects to reduce emissions as well as to support other transportation modes in a region, even if such projects may not be as cost effective as projects of other project types in reducing emissions.

While DOT has communicated to states about its tools for evaluating CMAQ projects, it has not done so on an ongoing basis. Federal internal control standards state that agencies should externally communicate information on a timely basis to help stakeholders achieve their objectives. However, most of DOT’s communications to states about one of its tools—the cost-effectiveness tables—occurred when DOT last published the tables in 2020. Moreover, about one-third of states that responded to a GAO survey said they or other relevant entities in their states were unaware of these tables. Ongoing communication from DOT about the tables could increase states’ awareness and, ultimately, contribute to states selecting CMAQ projects that are more cost effective in reducing emissions of pollutants.

Abbreviations

|

CMAQ |

Congestion Mitigation and Air

Quality Improvement |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FHWA |

Federal Highway Administration |

|

MPO |

metropolitan planning organization |

|

PM |

particulate matter |

|

State DOT |

state department of transportation |

|

STBG |

Surface Transportation Block Grant Program |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 18, 2025

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

Chairman

The Honorable Sheldon Whitehouse

Ranking Member

Committee on Environment and Public Works

United States Senate

The Honorable Sam Graves

Chairman

The Honorable Rick Larsen

Ranking Member

Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure

House of Representatives

Cars, trucks, and other modes of transportation are a major source of emissions that can affect air quality and human health. Adverse health effects from exposure to emitted pollutants may include respiratory and cardiovascular diseases that can lead to premature death. One study estimated that emissions from cars, trucks, and other vehicles will contribute to between 6,700 and 18,000 premature deaths in the U.S. in 2025.[1]

Since 1991, the Department of Transportation’s Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) has provided funding to states, under a formula established in statute, to support transportation projects that reduce emissions of certain criteria pollutants.[2] The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provided CMAQ approximately $13.2 billion for fiscal years 2022 through 2026.[3] CMAQ funds support projects in areas that do not currently, or did not previously, meet federal air quality standards for certain criteria pollutants—carbon monoxide, ozone, or particulate matter.[4] The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets these standards pursuant to the Clean Air Act.[5] EPA defines geographic areas that do not meet federal air quality standards for criteria pollutants as “nonattainment areas” and areas that previously did not but now meet the standards as “maintenance areas.”

Within the Department of Transportation, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) oversees and assists states with administering CMAQ. FHWA has developed tools to help entities—primarily state departments of transportation (DOT) and metropolitan planning organizations (MPO)—implement CMAQ and select projects that will reduce emissions of pollutants.[6] For instance, FHWA developed a calculator toolkit that, according to FHWA, state DOTs and MPOs can use to estimate emissions reductions for the majority of CMAQ-eligible projects. Also, as required by statute, FHWA developed cost-effectiveness tables for state DOTs and MPOs to consider when selecting CMAQ projects that show the cost effectiveness of reducing emissions for a range of project types.[7] However, FHWA has not tracked data on the extent to which state DOTs and MPOs use these tools.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act includes a provision for GAO to review the CMAQ program.[8] This report examines (1) how states have used CMAQ funds since fiscal year 2015, (2) the emissions outcomes of CMAQ projects since fiscal year 2015 and how FHWA tracks CMAQ outcomes, (3) the cost effectiveness of CMAQ projects at reducing emissions since fiscal year 2015 according to available FHWA data and reports, and (4) the extent to which FHWA has communicated to state DOTs and MPOs about FHWA tools for evaluating emissions reductions and cost effectiveness of CMAQ projects.

To inform all objectives, we reviewed relevant statutes; examined Department of Transportation and FHWA guidance and other documentation for CMAQ; and interviewed FHWA and EPA officials. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with a non-generalizable selection of relevant state and local agencies—such as state DOTs and MPOs—in six states.[9] We selected states to represent a range of population, location, extent of attainment of federal air quality standards, and other factors. Across objectives, our scope was the 50 states and Washington, D.C. (referred to collectively as 51 states), as they were the direct recipients of CMAQ funding for the time frame examined for this report.

In addition, to inform all objectives, we analyzed data from FHWA’s CMAQ project database on projects that started in fiscal years 2015 through 2023, the latest year for which data were available at the time of our review. Because CMAQ funding can support projects over multiple years, we conducted our analysis at the project level. We used a project identification field to combine individual project data, including project costs and estimated reductions of emissions of CMAQ pollutants, over multiple years. As a result, we report on projects only in the first year in which they were funded and include any additional costs and estimated emissions reductions in future years in that first year.

We analyzed data to determine trends in the categories, costs, and estimated emissions reductions of projects over time.[10] To focus our analysis on the use of federal funds, we analyzed CMAQ funds used for projects and not funds from other sources. To determine the reliability of these data, we reviewed FHWA documentation on the database, interviewed FHWA officials, and manually reviewed the data for any obvious missing data, errors, or outliers. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting on trends in the project categories funded with CMAQ and the costs and emissions reductions of those projects.

To inform our objective on how states have used CMAQ funds, we also analyzed financial data from FHWA’s Financial Management Information System regarding transfers between CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs from fiscal years 2015 through 2024, the latest year for which data were available at the time of our review.[11] To determine the reliability of the financial data we reviewed FHWA documentation on the database, interviewed FHWA officials, and manually reviewed the data for any obvious missing data, errors, or outliers. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting on transfers of funds among CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs.

To inform our objective on the emissions outcomes of CMAQ projects and how FHWA tracks outcomes, we analyzed FHWA data on CMAQ performance measures for FHWA’s first performance period (October 2017 through December 2021). From this analysis, we determined whether state DOTs and MPOs met their targets for relevant performance measures. To determine the reliability of these data, we reviewed FHWA documentation on the data, interviewed FHWA officials, and manually reviewed the data for any obvious missing data, errors, or outliers. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting on the extent to which state DOTs and MPOs have set and met CMAQ performance measures.

To inform our objective on the cost effectiveness of CMAQ projects at reducing emissions, according to available FHWA data and reports, we analyzed data from FHWA’s CMAQ project database on projects started from fiscal years 2015 through 2023, as described above, along with information on cost-effectiveness ratings in FHWA’s 2020 tables.[12] Specifically, we applied FHWA’s cost-effectiveness ratings for 21 project types from the 2020 tables to the funded projects listed in the CMAQ project database for those fiscal years.[13] The 2020 tables rate 21 types of CMAQ projects based on the median cost per ton of emissions reduction calculated from a range of scenarios for each project type; the tables rate cost effectiveness (1) across all pollutants and (2) for each specific pollutant.

We applied both ratings to projects. We applied the most relevant project type from the 2020 tables to each funded CMAQ project by reviewing the project category, title, and description. (For about 20 percent of the projects, we were unable to apply a project type.[14]) We then analyzed the data to describe the cost effectiveness of funded CMAQ projects in reducing emissions. We reviewed FHWA’s cost-effectiveness tables, including their methodology, and interviewed FHWA and Department of Transportation staff about the table’s methodology and limitations and our methodology for using the tables.

Finally, to inform our objective on how FHWA communicated to state DOTs and MPOs about FHWA tools on emissions reductions and cost effectiveness of CMAQ projects, between August and October 2024 we surveyed all state DOTs regarding their experiences with those tools. We received responses from 51 state DOTs. In addition, we reviewed FHWA communications on those tools and interviewed FHWA officials; then we evaluated FHWA’s actions against internal control standards on external communication.[15] For more information on our scope and methodology, see appendix I. We also present additional information on the CMAQ project categories and our survey of state DOTs in appendixes II and III, respectively.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal-Aid Highway Funding and CMAQ

CMAQ is one of nine federal-aid highway formula funding programs through which FHWA provides funding to states.[16] States have the discretion to prioritize and select which eligible projects will receive federal-aid highway formula program funding. For fiscal year 2025, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provided about $55.7 billion for these nine programs, with CMAQ receiving approximately $2.7 billion.[17]

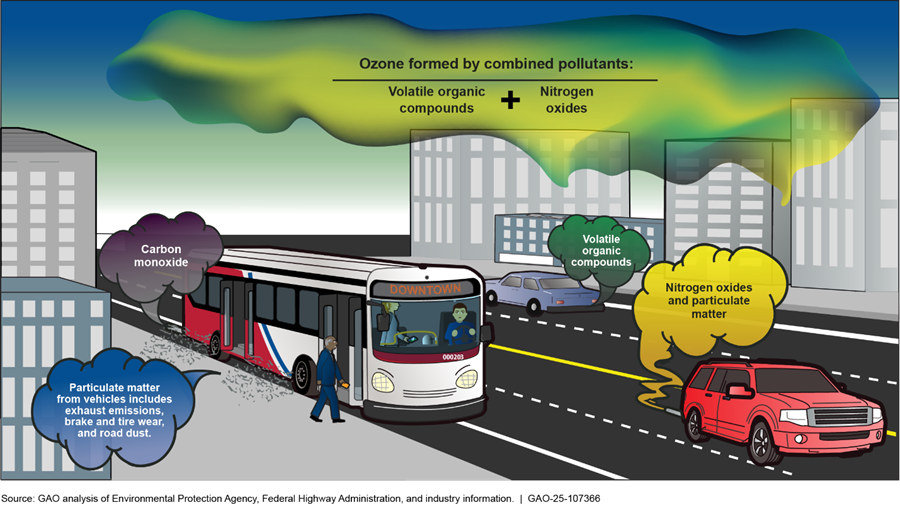

CMAQ provides funding to states to help meet the requirements of the Clean Air Act. Specifically, CMAQ funding is for transportation projects and programs that aim to reduce congestion and contribute to air quality improvements in areas that are in nonattainment or maintenance of federal air quality standards for ozone, carbon monoxide, or particulate matter.[18] CMAQ projects must contribute to the attainment or maintenance of at least one of the CMAQ-specified pollutants or its precursors, which we refer to as CMAQs pollutants. Those pollutants can come from a variety of transportation sources (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Examples of Sources of Emissions of Pollutants Addressed by the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program

EPA sets federal air quality standards for criteria pollutants, such as those addressed by CMAQ, at levels intended to protect public health, including the health of susceptible and vulnerable populations—people with pre-existing respiratory disease, children, and older adults, among others.[19] According to EPA, in 2023, more than 126 million people lived in counties where ozone levels exceeded federal air quality standards—more than for any other CMAQ pollutants.[20]

Each state’s annual CMAQ funding, or apportionment, is based on a formula specified in statute.[21] All states receive a minimum apportionment, but states with nonattainment or maintenance areas for CMAQ pollutants generally received larger apportionments. In fiscal year 2025, states’ apportionments for CMAQ ranged from approximately $11 million to approximately $537 million.[22] States have 3 years after the last day of the fiscal year in which funds were made available to obligate CMAQ funds.

CMAQ Project Selection

A project’s eligibility for CMAQ is set in statute.[23] According to 2024 FHWA guidance, project must meet three criteria to be eligible for CMAQ: (1) be a transportation project, (2) be located in or benefit a nonattainment or maintenance area, and (3) reduce emissions for CMAQ pollutants.[24] Many different projects are eligible for CMAQ (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Examples of Projects that are Eligible for the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program

Note: Federal Highway Administration information is from publications including Federal Highway Administration, The Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) Program Interim Program Guidance as Revised by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (Oct. 28, 2024) and Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program, 2020 Cost-Effectiveness Tables Update (Washington, D.C.: July 20, 2020).

A state DOT, on its own or in conjunction with MPOs, selects projects to fund with CMAQ dollars.[25] State DOTs and MPOs develop their own processes to evaluate and select CMAQ projects, but statute specifies some requirements related to CMAQ project selection, including the following:[26]

· Any state with a nonattainment or maintenance area for fine particulate matter (PM2.5), with some exceptions, is required to invest a portion of its CMAQ funds in projects to reduce PM2.5 emissions. Specifically, any such state must use 25 percent of its CMAQ apportionment, based on the weighted population of the PM2.5 nonattainment area in the state, for projects that reduce PM2.5 in these areas.[27]

· States must prioritize projects proven to reduce PM2.5, including diesel replacements or retrofits, when distributing CMAQ funds in PM2.5 nonattainment or maintenance areas.[28]

· States must consider cost effectiveness in mitigating congestion and improving air quality when selecting CMAQ projects.[29]

Although the goal of CMAQ is to fund transportation projects that reduce emissions of CMAQ pollutants, states have flexibilities to use some CMAQ funding for other purposes.

· Transfers. A state may transfer up to 50 percent of its CMAQ funds each fiscal year to other federal-aid highway formula programs. A state may also transfer funds from other federal-aid highway formula programs into CMAQ.[30] This ability to transfer funds helps states use funds to address their transportation priorities. Any CMAQ funds transferred to another program become subject to the requirements of that program.[31]

· Flexible CMAQ funds. Some states can use some or all of their CMAQ funds as CMAQ flexible funds for projects eligible for either CMAQ or the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program (STBG).[32] Examples of STBG projects include: (1) projects that preserve and improve the conditions and performance on federal-aid highways, (2) bridge and tunnel projects on any public road, (3) certain pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, and (4) transit capital projects. States that do not have, and have never had, a nonattainment or maintenance area for ozone, carbon monoxide, or particulate matter can use all their CMAQ funds as flexible funds. Some other states can use some CMAQ funds as flexible funds, while others cannot use any CMAQ funds that way.[33]

When transferring funds to other programs or using funds on STBG-eligible projects, state DOTs can use CMAQ funds for projects that may not reduce emissions of CMAQ pollutants.

FHWA Oversight and Tools

FHWA headquarters and division offices share oversight responsibility for CMAQ.[34] FHWA headquarters issues guidance, develops resources, and offers training, among other responsibilities. For example, in 2024 FHWA issued interim CMAQ guidance that includes information on how states can use CMAQ funds, project eligibilities, and FHWA tools to help state DOTs and MPOs evaluate potential projects.[35] Division offices in each state and the District of Columbia provide CMAQ technical assistance to state DOTs and MPOs, including answering questions about project eligibility and reviewing funding proposals.[36]

State DOTs annually report data on their CMAQ projects to FHWA, and FHWA maintains these data in a publicly available CMAQ project database.[37] Data include project category, title and description, amount of CMAQ and non-CMAQ funding, and estimated emissions reductions.[38] FHWA headquarters and division office staff review reported data for completeness and accuracy.

States Used CMAQ Funds in Various Ways, Including for Projects to Improve Traffic Flow and Transfers to Other Programs

During fiscal years 2015 through 2023, we found states overall used a majority of their CMAQ apportionments to fund projects eligible for CMAQ that aim to improve air quality and reduce congestion—such as traffic flow improvements and bicycle and pedestrian projects. We also found that states are increasingly transferring CMAQ funds to other federal-aid highway formula programs and using their CMAQ funds as flexible funds for STBG-eligible projects that may not improve air quality.

CMAQ Mostly Funded Traffic Flow Improvement, Bicycle and Pedestrian, and Transit Projects

Most CMAQ projects that started in fiscal years 2015 through 2023, and most of the costs of those projects, were in three of 10 categories of CMAQ-eligible projects tracked by FHWA: congestion reduction and traffic flow improvements, transit improvements, and bicycle and pedestrian facilities and programs (see table 1).[39] Some of the project categories in FHWA’s CMAQ database, such as congestion reduction and traffic flow, are broad, encompassing a variety of different projects. Others, such as advanced diesel truck and engine technologies, are more limited.[40] See appendix II for more information on the CMAQ project database categories.

|

Project category |

Percentage of all CMAQ projects |

Percentage of all CMAQ project costs |

|

Advanced diesel truck/engine technologies |

1.7 |

1.0 |

|

Alternative fuels and vehicles |

3.3 |

2.7 |

|

Bicycle and pedestrian facilities and programs |

23.5 |

13.5 |

|

Congestion reduction and traffic flow improvements |

39.8 |

38.9 |

|

Freight/intermodal |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Inspection/maintenance programs |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Other |

5.0 |

1.9 |

|

Ride sharing |

4.3 |

1.6 |

|

Transit improvements |

14.8 |

33.9 |

|

Travel demand management |

6.1 |

5.5 |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Highway Administration Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) project data. | GAO‑25‑107366

Notes:

States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. For our analysis, we count projects only in the first fiscal year in which the projects were funded. Any costs in subsequent fiscal years for the same project are included in that first fiscal year. Our analysis does not include project costs from other sources.

States are allowed, under statute, to transfer up to 50 percent of their CMAQ funds to other federal-aid highway formula programs. Some states are also able to use some or all of their CMAQ funds on projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program. These numbers represent the share of CMAQ projects and CMAQ funds after accounting for those transfers and Surface Transportation Block Grant-eligible projects.

|

Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) Project Eligibility We asked state departments of transportation (DOTs) and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) we interviewed about projects or project expenses currently ineligible for CMAQ that could help reduce emissions of CMAQ pollutants. Those we interviewed did not offer consistent suggestions on potential projects or project expenses. Officials from three state DOTs and eight MPOs we interviewed provided examples, such as funding operating costs of new transit services beyond the initial period that the statute allows. In addition, officials with one state DOT and one MPO explained that the demand for CMAQ funding is great, and they have several projects that fall under existing CMAQ eligibilities awaiting such funding. Therefore, that state DOT and MPO do not have a need to identify other projects that could reduce emissions. Source: GAO interviews with state DOTs and MPOs. | GAO‑25‑107366 |

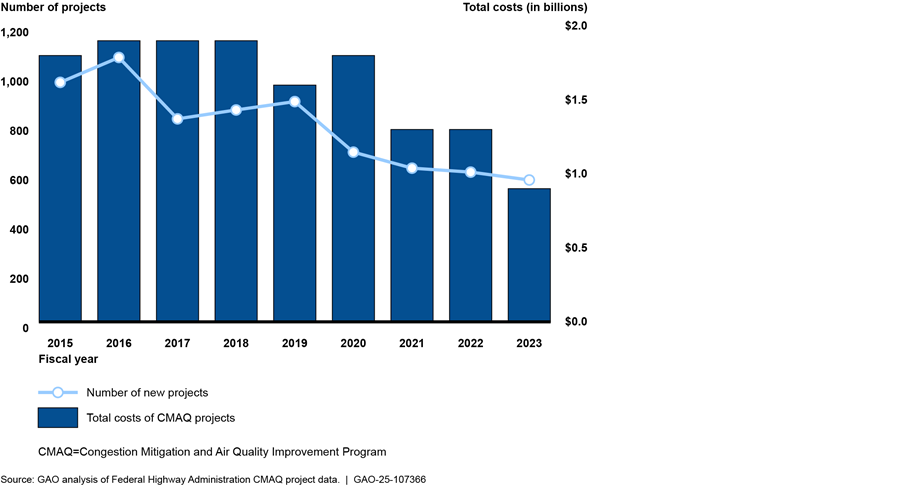

The total number of CMAQ projects started in fiscal years 2015 through 2023, and the total CMAQ costs of those projects, decreased over time (see fig. 3).[41]

Notes:

States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. For our analysis, we count projects only in the first fiscal year in which the projects were funded. Any costs in subsequent fiscal years for the same project are included in that first fiscal year. Therefore, the total costs of CMAQ projects started in fiscal years 2022 and 2023 could increase in the future if states obligate CMAQ funds apportioned in later years for projects started in fiscal year 2022 or 2023. In addition, our analysis includes project costs only supported by CMAQ and not project costs from other sources.

States are allowed, under statute, to transfer up to 50 percent of their CMAQ funds to other federal-aid highway formula programs. Some states are also able to use some or all of their CMAQ funds on projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program. These numbers represent the share of CMAQ projects and CMAQ funds after accounting for those transfers and Surface Transportation Block Grant-eligible projects.

The reduction in the number of projects funded every year could be due to a few factors. Officials with one MPO and one state DOT we interviewed said CMAQ projects have become more expensive in recent years. This could have reduced the number of projects that state DOTs and MPOs are able to fund in a single year. In addition, transfers to other programs and use of CMAQ flexible funds for STBG-eligible projects increased over time, as described below, affecting the total funding remaining for CMAQ-eligible projects.

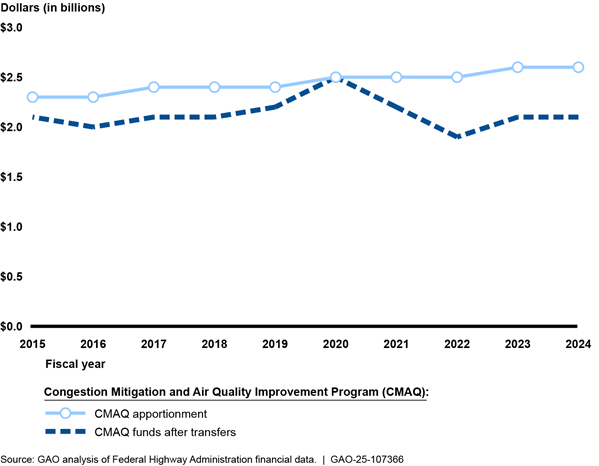

States Increasingly Transferred Funds to Other Federal-Aid Highway Formula Programs

Transfers out of CMAQ to other federal-aid highway formula programs increased from 10 percent of apportionments in fiscal year 2015 to 19 percent in fiscal year 2024, based on our analysis of FHWA financial data.[42] Across years, transfers represented about 13 percent of total CMAQ apportionments. While states can transfer funds from other programs into CMAQ, states primarily transferred funds out of CMAQ. As a result, while apportionments to CMAQ increased over time, funds available for CMAQ projects after transfers remained relatively flat (see fig. 4). For example, while CMAQ apportionments in fiscal year 2024 were $2.6 billion, CMAQ funds after transfers were $2.1 billion.

Figure 4: Total Apportionments to CMAQ and Funds Remaining After Transfers to Other Federal-Aid Highway Formula Programs, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

Note: Because states have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate or transfer funds, transfers in one year may be of funds apportioned in other years. We based our analysis on the year of the apportionment of funds, regardless of when the funds were transferred.

Once transferred out of CMAQ, funds may be used to support a broader range of goals. For example, a state could transfer funds from CMAQ—a program that aims to improve air quality—to the Highway Safety Improvement Program—a program that aims to reduce fatalities and serious injuries on public roads. The Highway Safety Improvement Program has funded projects such as work zone safety messages and outreach programs on highway safety matters. According to FHWA, transferring funds between programs could help a state use its federal-aid highway formula funds on projects that better align with its specific needs.

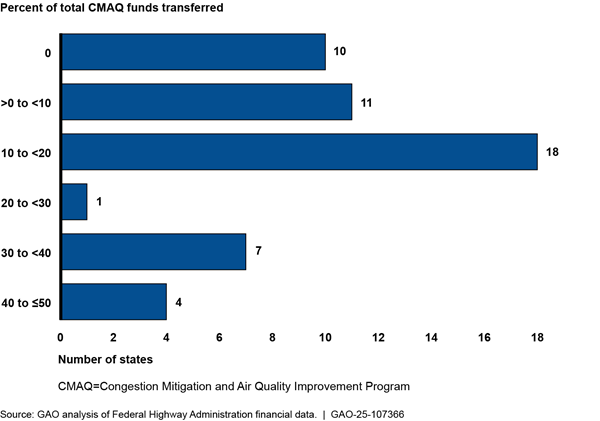

During fiscal years 2015 through 2024, 40 states plus Washington, D.C. transferred funds between CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs such as the Highway Safety Improvement Program and the National Highway Performance Program. Their net transfers out of CMAQ varied. For example, 29 states transferred up to 20 percent of their apportioned CMAQ funds and four states transferred over 40 percent (see fig. 5).[43]

Figure 5: Number of States by Share of Net Transfers from CMAQ to Other Federal-Aid Highway Formula Programs, Fiscal Years 2015–2024

Note: Our scope includes 50 states plus Washington, D.C. Because states have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds, including transferring funds between programs, transfers in one year may be of funds apportioned in other years. As a result, for example, funds apportioned in fiscal year 2024 may be transferred in the future. Our analysis is based on the fiscal year for which the funds were apportioned, regardless of whether those funds were transferred.

States may transfer CMAQ funds to other federal-aid highway formula programs to use funds more easily. For example, a state may transfer funds to the National Highway Freight Program if it had greater funding needs for freight projects in a given year. According to a 2022 study, transfers among all federal-aid highway formula programs have generally increased over time, and states tend to transfer funds from programs with more restrictions on the use of funds to programs with fewer restrictions.[44] The report noted that states may be less likely to transfer funds into CMAQ, since CMAQ projects can be complex and challenging to implement. Officials with two state DOTs told us they transfer CMAQ funds to other programs where funds can be spent more quickly. One of those state DOTs added that they transfer CMAQ funds to programs that have fewer restrictions on the use of funds. On the other hand, officials with two other state DOTs said their states have enough projects to fund with CMAQ and, therefore, do not transfer any of their CMAQ funding.

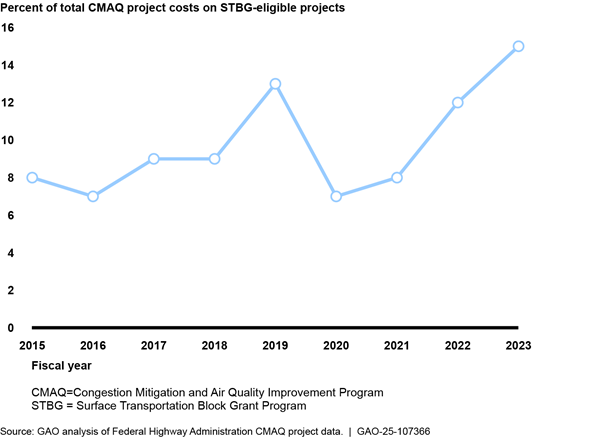

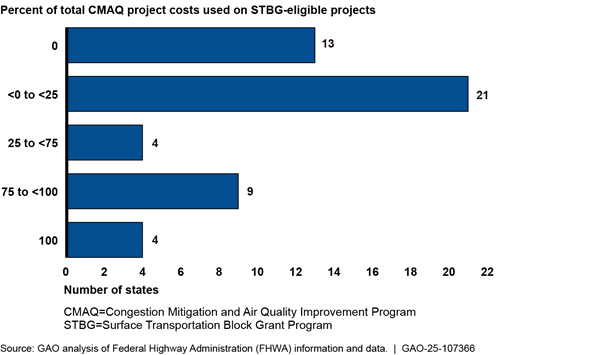

States, to Varying Extents, Used CMAQ Flexible Funds for a Broad Range of Transportation Projects

Within CMAQ, states also increased their use of flexible CMAQ funds. A state with flexible CMAQ funds can use those funds throughout the state for projects eligible for either CMAQ or STBG, without having to transfer the funds out of CMAQ. We found the percentage of total CMAQ project costs used on STBG-eligible projects increased from 8 percent of the total costs of projects started in fiscal year 2015 to 15 percent in fiscal year 2023 (see fig. 6).[45] Overall, across all states, 10 percent of the costs of CMAQ projects started from fiscal years 2015 through 2023 were for STBG-eligible projects. On average, this was approximately $171 million per year.

Figure 6: Percentage of CMAQ Funds Spent on Projects Eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program, Fiscal Years 2015–2023

Notes:

States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. Our analysis considers projects in the first year that they were funded and any project costs in subsequent years are included in that first year. Our analysis does not include project costs from other sources.

States are allowed, under statute, to transfer up to 50 percent of their CMAQ funds to other federal-aid highway formula programs. This analysis considers the percentage of CMAQ funds after accounting for transfers between CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs.

The percentage of CMAQ funds that states can use for STBG-eligible projects varies. Based on our analysis of FHWA’s CMAQ apportionment data for fiscal year 2024, 17 states were able to use all their CMAQ funds as flexible funds. In addition, 13 states were able to use some but not the full amount of their CMAQ funds as flexible funds and 21 states could not use any of their CMAQ funds in this way.

However, states varied in the extent to which they used their CMAQ funds as flexible funds for STBG-eligible projects. In total, 38 of 51 states used CMAQ funds on STBG-eligible projects started in at least 1 fiscal year from 2015 through 2023. In 21 of those 38 states, less than 25 percent of the total costs of CMAQ projects, after transfers, were on STBG-eligible projects. Four states exclusively funded STBG-eligible projects with CMAQ (see fig. 7). One state DOT we interviewed, for example, is allowed to use all its CMAQ funds for STBG-eligible projects and has done so to fund a range of projects to help maintain the state’s roadway system. On the other hand, another state DOT we interviewed has used less than 1 percent of its flexible CMAQ funds for STBG-eligible projects because there were enough demands in its state for CMAQ-eligible projects.

Figure 7: Number of States by Percentage of CMAQ Funds Used on Projects Eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program, Fiscal Years 2015–2023

Notes:

Our scope includes 50 states plus Washington, D.C. States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. Our analysis considers projects in the first year that they were funded and any project costs in subsequent years are included in that first year. Our analysis does not include project costs from other sources.

States are allowed, under statute, to transfer up to 50 percent of their CMAQ funds to other federal-aid highway formula programs. This analysis considers the percentage of CMAQ funds after accounting for transfers between CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs.

CMAQ Projects Most Often Reduced Pollutants Related to Ozone, and FHWA Has Started to Track CMAQ Performance Measures

CMAQ Data Show Most Projects Since Fiscal Year 2015 Reduced Ozone-Related Pollutants

Pollutants Addressed by CMAQ Projects

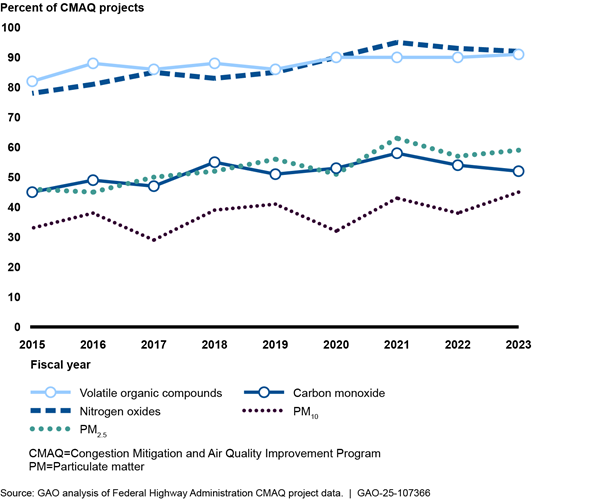

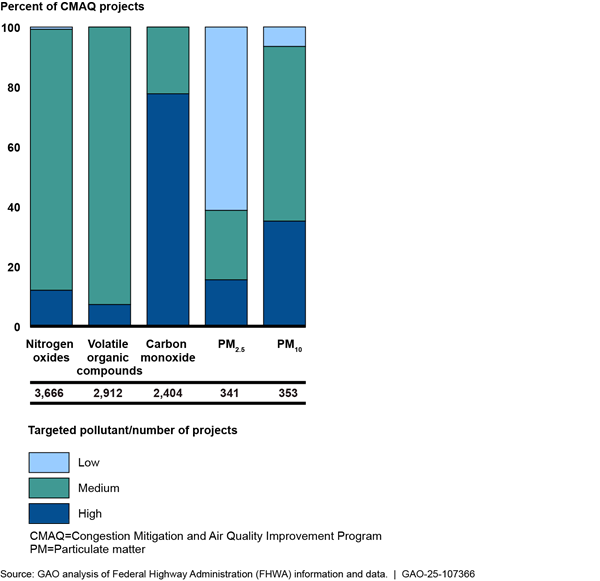

The share of projects reporting emissions reductions increased for each pollutant from fiscal years 2015 through 2023, based on our analysis of CMAQ data of projects that begin in these fiscal years.[46] Overall, the greatest share of projects reported estimated emissions reductions for two ozone precursors—nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds (see fig. 8).[47] This is consistent with EPA data showing that more people lived in areas where ozone levels exceeded federal air quality standards compared to such areas for other CMAQ pollutants in 2023.[48] The smallest share of CMAQ projects reported estimated emissions reductions of PM10.[49]

Figure 8: Percentage of CMAQ Projects Reporting Estimated Emissions Reductions, by Pollutant, Fiscal Years 2015–2023

Note: States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. Our analysis considers projects in the first year that they were funded. Some states are also able to use some or all of their CMAQ funds on projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program. This analysis considers the percentage of CMAQ projects after excluding projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program.

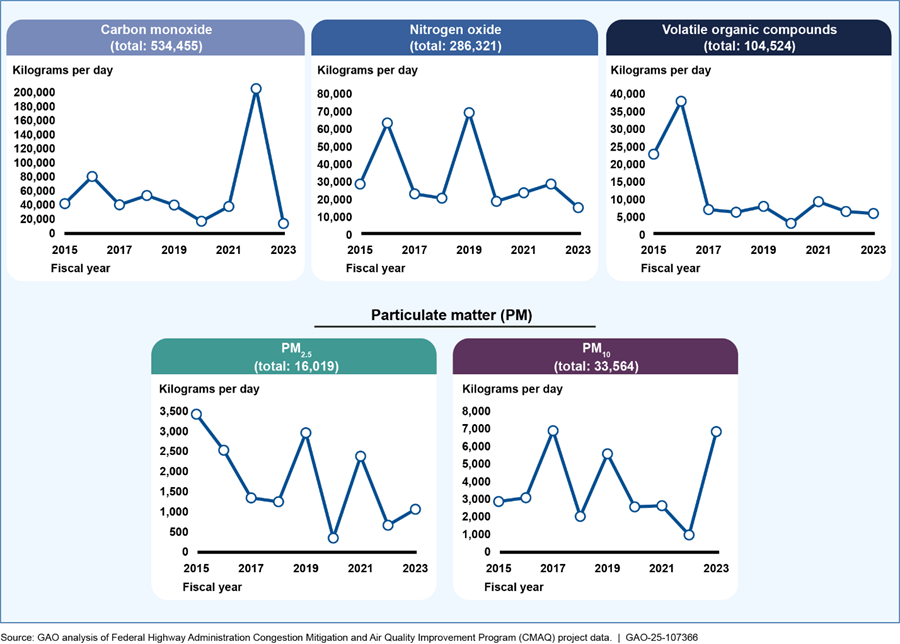

Estimated Emissions Reductions of Pollutants

Based on our analysis, the yearly estimated emissions reductions for most pollutants generally decreased between fiscal years 2015 and 2023, although the estimated reductions varied substantially year-to-year for most pollutants (see fig. 9).[50]

Figure 9: Estimated Total Reduced Emissions from CMAQ Projects, by Pollutant, Fiscal Years 2015–2023

Note: States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. Our analysis considers projects in the first year that they were funded. Some states are also able to use some or all of their CMAQ funds on projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program. This analysis considers the percentage of CMAQ projects after excluding projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program.

Downward trends in emissions reductions may be explained by a number of factors. Over time, as state DOTs and MPOs fund more projects with CMAQ, they may have fewer available projects that provide high emissions reductions. One MPO we interviewed said that some of the projects that are the most cost effective at reducing emissions have already been done, so the “low hanging fruit” to reduce emissions is no longer available. As a result, they may have funded projects in more recent years that have lower emissions reductions. In addition, as passenger vehicles have become more fuel efficient and cleaner over the last 2 decades, projects that reduce vehicle miles traveled may result in lower emissions reductions over time. In addition, as shown in figure 3 above, the total number of CMAQ projects has decreased over time. According to FHWA officials, the number of projects in each category has also changed over time. As a result, if some state DOTs and MPOs have shifted to funding project categories whose projects generally have lower emissions reductions, then emissions reductions may decrease.

Emissions Reductions in Disadvantaged Communities

The Department of Transportation found that 34 percent of CMAQ funds benefited disadvantaged communities in fiscal year 2023, and 36 percent did so in fiscal year 2022.[51] Some states must prioritize CMAQ projects that reduce emissions of PM2.5 in disadvantaged areas.[52] However, one state DOT and five MPOs we interviewed consider location in disadvantaged communities as part of their project selection process.[53] For example, officials with one MPO told us they score projects on a points system that provides additional points to projects in disadvantaged communities as part of the process for evaluating CMAQ projects. In addition, this MPO identifies disadvantaged communities as areas where at least 20 percent of the population is low-income or at least half of the population are individuals who identify as part of racial or ethnic minority groups.

FHWA Established CMAQ Performance Measures for Emissions Reductions and Traffic Congestion

Since fiscal year 2018, FHWA has tracked three performance measures for the CMAQ program—one for emissions of CMAQ pollutants and two for traffic congestion.[54] Certain state DOTs and MPOs are required to establish targets and report performance to FHWA on these performance measures based in part on their state’s or area’s attainment of federal air quality standards.[55]

|

Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) Performance Measures · On-Road Mobile Source Emissions: A measure of reductions in estimated emissions of each criteria pollutant and precursors under the CMAQ program for projects in areas that are not currently, or previously were not, in compliance with federal air quality standards. This includes emissions for carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), and volatile organic compounds. · Percent of Non-Single Occupancy Vehicle Travel: A measure of the share of travelers using modes of transportation other than driving by themselves in their cars. · Annual Hours of Peak Hour Excessive Delay Per Capita: A measure of traffic congestion during peak hours that accounts for the longest travel time compared to the average travel time, the number of vehicles on the road, and number of vehicle occupants. Source: Federal Highway Administration, Transportation Performance Management: CMAQ Performance Measures (Washington, D.C., 2019). | GAO‑25‑107366 |

The state DOTs and MPOs that are subject to the performance measures set targets for 2 years and 4 years, and then report performance at these points, for a 4-year reporting period. The first reporting period ended in 2021; the second reporting period is underway and will end in 2025.[56]

For the first reporting period, the majority of states that were required to set targets met their targets for the on-road mobile source emissions measure for all pollutants (see table 2). For the traffic congestion measures in the first performance period, most areas met their targets for the percent of non-single occupancy vehicle travel, while nearly all met their targets for annual hours of peak hour excessive delay per capita.[57]

Table 2: Performance Outcomes for On-Road Mobile Source Emissions Measure, October 1, 2017–September 30, 2021

|

|

Carbon monoxide |

Nitrogen oxides |

Particulate matter (PM)2.5 |

PM10 |

Volatile organic compounds |

|

State departments of transportation (DOT) required to set targets and report performance |

18 |

36 |

19 |

19 |

27 |

|

State DOTs that met 2-year target |

11 (61%) |

22 (61%) |

12 (63%) |

11 (58%) |

18 (67%) |

|

State DOTs that met 4-year target |

14 (78%) |

25 (69%) |

15 (79%) |

13 (68%) |

19 (70%) |

Source: GAO analysis of Federal Highway Administration data. | GAO‑25‑107366

Note: Statute required the Department of Transportation to establish performance measures for on-road mobile source emissions (23 U.S.C. § 150(c)(5)). The Department of Transportation established performance measures for some state DOTs and MPOs in regulation (23 C.F.R. Part 490). Specifically, state DOTs and MPOs with CMAQ-funded projects in nonattainment or maintenance areas for ozone, carbon monoxide, or particulate matter must establish performance requirements for emissions for each applicable CMAQ pollutant within the boundaries of that area.

In responding to our survey, the largest number of state DOTs that answered questions on the performance measures said that each of the measures were somewhat useful (see table 3).

|

|

Annual hours of peak hour excessive delay per capita |

Percent of non-single occupancy vehicle travel |

On-road mobile |

|

Very useful |

6 |

6 |

7 |

|

Moderately useful |

6 |

4 |

8 |

|

Somewhat useful |

13 |

15 |

14 |

|

Not at all useful |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

Total |

31 |

31 |

35 |

CMAQ = Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program

State DOT = state department of transportation

Source: GAO survey of state DOTs. | GAO‑25‑107366

Note: We asked state DOTs about usefulness of the three performance measures only if they responded that they must set a target and report on the measures.

MPOs we interviewed provided some insights into why they believed the performance measures were, or were not, useful. Officials with one MPO stated that the measures can help MPOs better identify projects, assess results, and justify investments to the public. However, officials with two MPOs said that the congestion measures focus on regional or highway traffic, while their CMAQ projects address congestion in a more local area. In addition, officials with two other MPOs stated that their performance on the three measures is not necessarily correlated with the outcomes of projects funded by CMAQ.

As of January 2025, FHWA was taking steps to improve technical assistance for state DOTs and MPOs on the performance measures. For example, FHWA was identifying potential inconsistencies in reporting performance data during the first performance period to better target training materials. In addition, FHWA was reviewing MPO reporting to facilitate the exchange of notable practices in setting targets.

Most CMAQ Projects Since 2015 Were in Project Types FHWA Rated as Having Weak Cost Effectiveness for Reducing Emissions

FHWA Created Cost-Effectiveness Ratings for Reducing Emissions for Several Types of CMAQ Projects

FHWA developed a set of cost-effectiveness tables that rate the cost effectiveness (i.e., dollars per ton of emissions reduced) for several types of eligible CMAQ projects. FHWA published these tables as a resource for state DOTs and MPOs to assess the cost effectiveness of projects at reducing emissions of CMAQ pollutants. FHWA first published these tables in 2015, then updated them in 2020.[58]

According to FHWA’s CMAQ guidance, prioritizing CMAQ projects that are cost effective in reducing emissions may better position state DOTs and MPOs to reach attainment or maintenance of federal air quality standards. In addition, statute requires state DOTs and MPOs to consider the cost-effectiveness information in these tables when selecting projects for CMAQ funding.[59] The statute is not specific as to how state DOTs and MPOs should consider that information.

Overall FHWA Cost-Effectiveness Ratings

|

Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) Cost-Effectiveness Analysis FHWA determined a median cost-effectiveness estimate for 21 project types based on projects in FHWA’s CMAQ project database. To develop the 21 project types, FHWA examined projects in the CMAQ project database and worked with experts in FHWA and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The 21 project types do not cover all projects eligible for CMAQ. For project costs, FHWA used data from the CMAQ project database, supplemented with data from outside sources such as publications from state and local governments and professional organizations. Project costs in FHWA’s analysis include all project costs, not just those supported by CMAQ. FHWA modeled emissions reductions using EPA’s MOtor Vehicle Emissions Simulator (MOVES). FHWA also factored in other assumptions, such as project lifetimes. FHWA calculated the cost effectiveness for a range of scenarios for each project type and then reported on the median cost effectiveness. Source: Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) Program: 2020 Cost-Effectiveness Tables Update (Washington, D.C., July 20, 2020). | GAO‑25‑107366 |

FHWA’s 2020 CMAQ tables calculated a median cost effectiveness (in terms of the cost per ton of estimated emissions reduced across all CMAQ pollutants) for 21 types of eligible CMAQ projects. To evaluate cost effectiveness, FHWA estimated the cost per ton of emissions reduction for each pollutant in a range of scenarios for each project type, determined the median value of that range, and then determined the median across all pollutants. However, FHWA acknowledges that projects are typically selected based on their effectiveness at reducing specific pollutants, rather than across all pollutants.[60] While those 21 project types include a wide range of eligible projects, they do not include all projects that are CMAQ-eligible.[61]

The tables rate the cost effectiveness in reducing emissions of the 21 project types with the seven most cost effective rated as “strong,” the next seven as “mixed,” and the seven least cost effective as “weak” (see table 4).[62] Some of these 21 project types may have more potential projects for state DOTs and MPOs to fund than others. For example, while traffic signal synchronization projects have wide potential use, extreme temperature cold start technologies have application only in cold climate locations.

Table 4: Rating of Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions by CMAQ Project Type, Federal Highway Administration 2020 Cost-Effectiveness Tables

|

Strong |

Mixed |

Weak |

|

Dust mitigation |

Traffic signal synchronization |

Extreme temperature cold-start technologies |

|

Idle reduction strategies |

Park and ride |

Bikesharing |

|

Diesel engine retrofit technologies |

Natural gas re-fueling infrastructure |

Bicycle and pedestrian improvements |

|

Intermodal freight facilities and programs |

Electric vehicle charging stations |

Intersection improvements |

|

Carsharing |

Transit amenity improvements |

Subsidized transit fares |

|

Incident management |

Rideshare programs |

Employee transit benefits |

|

Transit service expansion |

Roundabouts |

Heavy-duty vehicle replacements |

CMAQ = Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program

Source: Federal Highway Administration information. | GAO‑25‑107366

Notes:

Information from Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) Program: 2020 Cost-Effectiveness Tables Update (Washington, D.C., July 20, 2020).

The 2020 tables classify project types with strong cost effectiveness as those that cost less than $2.8 million per ton of emissions reduced across all CMAQ pollutants, mixed cost effectiveness as those that cost between $2.8 and $8.8 million per ton of emissions reduced across all CMAQ pollutants, and weak as those costing $8.8 million or more per ton across all CMAQ pollutants.

According to the 2020 tables, cost effectiveness, in terms of dollars per ton of emissions reduced, tends to be stronger for projects that reduce the number of vehicles on the road to reduce emissions. Carsharing projects, for example, encourage shifts from individual to shared vehicle travel, thus reducing single occupancy vehicle trips and their emissions. Intersection improvement projects, on the other hand, may reduce congestion and idling at intersections but do not remove vehicles from the road, and the tables rate those projects as having weak cost effectiveness. In addition, according to the tables, when projects have high costs, those high costs can result in weaker overall cost effectiveness. For example, while bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure projects may remove vehicles from the road, their large overall costs relative to their estimated emission reductions may result in weak cost effectiveness.

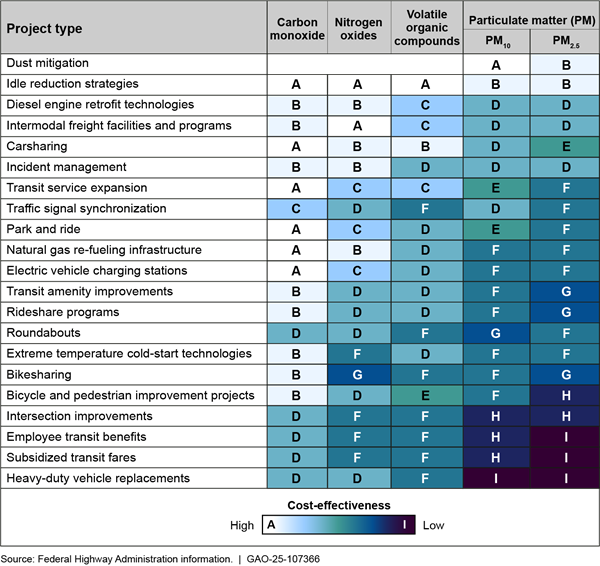

FHWA Cost-Effectiveness Ratings by Pollutant

The 2020 tables also rate each project type for how cost effective it is at reducing emissions of each CMAQ pollutant on a letter scale based on the median cost per ton of emissions reduction (see fig. 10).

Figure 10: Ratings for Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions for CMAQ Project Types, by Pollutant

CMAQ = Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program

Notes:

Information from Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) Program: 2020 Cost-Effectiveness Tables Update (Washington, D.C., July 20, 2020).

The tables applied a rating of A (highest) through I (lowest) for cost effectiveness based on the median estimated cost per ton of emissions reduction for each project type for each pollutant. Project types with a lower median cost per ton of emissions reduction have a higher cost-effectiveness rating. Blank cells for dust mitigation indicate that those pollutants do not apply to that specific project type.

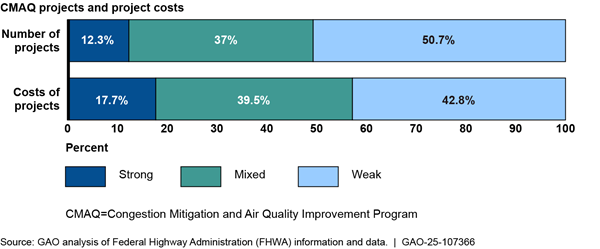

About 80 Percent of CMAQ Projects Funded Since 2015 Were of a Project Type with Mixed or Weak Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions

Overall Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions

Our analysis found that most CMAQ projects started in fiscal years 2015 through 2023, and most of the costs of those projects, were in project types that FHWA rated as having mixed or weak cost effectiveness at reducing emissions.[63] Specifically, 88 percent of CMAQ projects and 82 percent of the total costs of those projects were in project types with mixed or weak cost effectiveness (see fig. 11). For this analysis, we were able to apply the 2020 tables’ cost-effectiveness ratings by project type to about 80 percent of projects in the CMAQ project database, after excluding STBG-eligible projects, for fiscal years 2015 through 2023.[64] This analysis applies a rating across all pollutants, but as noted above, CMAQ projects are often selected based on their effectiveness in reducing only certain pollutants.

Figure 11: Percentage of CMAQ Projects and Funding by Rating of Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions, Fiscal Years 2015–2023

Notes:

Information from Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) Program: 2020 Cost-Effectiveness Tables Update (Washington, D.C., July 2020) and data from FHWA CMAQ project data.

States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. Our analysis considers projects in the first year that they were funded, and any project costs in subsequent years are included in that first year. In addition, our analysis does not include project costs from other sources. This analysis considers the percentage of CMAQ funds after accounting for transfers between CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs and CMAQ funds spent on projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program.

The 2020 tables classify project types with strong cost effectiveness as those that cost less than $2.8 million per ton of emissions reduced across all CMAQ pollutants, mixed cost effectiveness as those that cost $2.8 million to $8.8 million per ton of emissions reduced across all CMAQ pollutants, and weak as those costing $8.8 million or more per ton across all CMAQ pollutants.

Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions by Pollutant

In applying the FHWA cost-effectiveness ratings to CMAQ projects by pollutant targeted, we found the greatest number of projects targeted nitrogen oxides and were mostly project types with medium cost-effectiveness ratings (see fig. 12).[65] Several projects targeted carbon monoxide and these projects generally were of a project type that had high cost-effective ratings. Few projects targeted PM2.5 emissions, and those projects generally had low and medium cost-effective ratings. We found similar trends when analyzing the costs of CMAQ projects by pollutant. However, some pollutants have more options for project types that are high for cost effectiveness in reducing emissions than others, as shown in figure 10 above. For example, for carbon monoxide, 15 of 21 project types are rated high, whereas for volatile organic compounds, only five of 21 are rated high.

Figure 12: Percentage of CMAQ Projects, by Targeted Pollutant and Rating of Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions, Fiscal Years 2015–2023

Notes:

Information from Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) Program: 2020 Cost-Effectiveness Tables Update (Washington, D.C., July 2020) and data from FHWA CMAQ project data.

States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. Our analysis considers projects in the first year that they were funded. This analysis considers CMAQ projects after accounting for transfers between CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs and CMAQ funds spent on projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program.

FHWA’s 2020 cost-effectiveness tables assigned a letter grade from A to I for each project type and each pollutant based on the median cost per ton of emissions reduction. For our analysis, we consider letters A through C to indicate high cost effectiveness, letters D through E to indicate medium cost effectiveness, and letters G through I to indicate low cost effectiveness.

The numbers represent the number of projects that targeted each pollutant.

Several Factors Affect Which Projects Are Funded and the Projects’ Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions

A variety of factors can influence what CMAQ project types state DOTs and MPOs fund and the cost effectiveness of those projects at reducing emissions.

Targeted CMAQ Pollutants

The cost effectiveness of CMAQ projects at reducing emissions, overall, may be influenced by which CMAQ pollutants state DOTs and MPOs address based on their attainment of federal air quality standards. As discussed earlier, for some CMAQ pollutants there are few project types that are high in cost effectiveness for reducing emissions. For example, if a state or MPO had areas in nonattainment for PM2.5 and, therefore, selected projects to reduce those emissions, it had limited options for project types that the 2020 tables rate as more cost effective. Conversely, a state or MPO with areas in nonattainment for ozone or carbon monoxide would have more options for project types that the 2020 tables rated as having higher cost-effectiveness. For carbon monoxide areas, where, according to EPA, the fewest number of people live in nonattainment areas amongst CMAQ pollutants, most of the project types have high cost-effective ratings.[66]

Additional Factors in Project Selection

State DOTs and MPOs have broad discretion in selecting projects and may consider and use factors in addition to cost effectiveness in reducing emissions. For example, FHWA’s 2024 CMAQ interim guidance suggests they may also consider safety and identify opportunities for investments to advance job creation.[67] All state DOTs and MPOs we interviewed that select CMAQ projects consider additional factors when evaluating and selecting CMAQ projects. For example, one MPO considers how each potential project would connect with the region’s transportation network. As discussed above, several state DOTs and MPOs consider location in disadvantaged communities when selecting projects. Project location may factor in selection in other ways as well. EPA officials told us that there may be other considerations besides cost effectiveness when selecting projects. For example, there may be specific projects that are relevant for reducing emissions to improve air quality in an area affected by a port.

Two state DOTs and eight MPOs told us they consider regional priorities when selecting CMAQ projects. Those priorities may affect the types of projects they focus on and, thus, the FHWA rating for cost effectiveness in reducing emissions of the CMAQ project types they fund.[68] For example, one MPO told us it uses CMAQ primarily to support bicycle and pedestrian and transit projects to align with regional goals to reduce vehicle miles traveled and support other transportation modes. Another MPO mostly funds intersection improvement projects to help address congestion, which is a key concern in its fast-growing area. Even though intersection improvement projects have weak cost effectiveness according to the 2020 tables, that MPO finds that such projects are the most cost effective at reducing emissions among the potential projects it considers. Another MPO told us that, to help support its regional mobility goals, it funds many bikeshare projects with CMAQ—a project type that rates weak in cost effectiveness in the 2020 tables.

How Cost Effectiveness is Considered in Project Selection

State DOTs and MPOs we interviewed use different methods to consider cost effectiveness in reducing emissions in their CMAQ project evaluation and selection processes. For example, one state DOT we interviewed conducts its own calculation of the estimated cost effectiveness for potential projects in reducing emissions; it uses that calculation as the primary of three key criteria used to evaluate potential projects. One MPO we interviewed said that cost effectiveness is calculated and considered when ranking potential CMAQ projects amongst themselves. In contrast, two MPOs said they calculate cost effectiveness but that that calculation is not a major factor in selecting projects.[69]

Project-Specific Conditions

Individual projects within any CMAQ project type can vary widely in their cost effectiveness in reducing emissions based on project specifics, such as location and scope. By contrast, the 2020 cost-effectiveness tables used median cost effectiveness estimates across a range of project conditions to determine the ratings. According to EPA officials, for example, the cost effectiveness of a new transit project could vary based on the transit network already in place and existing ridership levels. Similarly, one MPO told us a bicycle project in an urban area is likely to have more use and therefore be more cost effective than one located in a suburban area—even though the tables rate that project type as having low cost effectiveness, regardless of its location. In addition, one MPO we interviewed said it now focuses CMAQ funding for traffic signal projects in areas with high levels of heavy-duty vehicle traffic. This is because projects in such locations have a greater effect on emissions (and therefore, higher cost effectiveness in reducing emissions) than in other areas where such projects may be less cost effective given improvements in passenger vehicle emissions over time.

FHWA Consistently Communicated About its Emissions Calculator Toolkit But Not its Cost-Effectiveness Tables

FHWA Has Provided Ongoing Communication on the Emissions Calculator Toolkit

FHWA has communicated on an ongoing basis on the emissions calculator toolkit that it first released in 2016 to assist state DOTs and MPOs with estimating emissions reductions for projects. The calculator toolkit contains 18 calculators to estimate emissions reductions for certain eligible CMAQ projects. State DOTs and MPOs are not required to use FHWA’s calculator toolkit, and state DOTs and MPOs may use other methods to estimate emissions reductions. FHWA has communicated with state DOTs and MPOs on an ongoing and proactive basis about the toolkit through several formal methods.

· Bimonthly newsletter. FHWA produces bimonthly air quality newsletters that have often provided information on updates to the calculator toolkit.[70] About 80 percent (23 out of 29) of newsletters from January 2020 through October 2024 discussed the calculator toolkit.

· Division offices. These offices disseminate information from headquarters to state DOTs and MPOs. For example, division offices share information on new training webinars on the calculator toolkit.

· Conferences and meetings. FHWA communicates information on the calculator toolkit at conferences—most recently in 2023—and attends bimonthly meetings with an industry association to discuss CMAQ topics such as the calculator toolkit.

FHWA also included information about the calculator toolkit as part of program resources available to state DOTs and MPOs. This type of communication on the toolkit may require state DOTs and MPOs to seek out the information.

· FHWA’s website. In addition to hosting the toolkit, the FHWA website includes a video with instructions on using the calculator toolkit.

· CMAQ guidance. FHWA’s 2024 CMAQ interim guidance discusses the calculator toolkit, among many CMAQ topics. Specifically, the guidance discusses the purpose of the toolkit and provides a link to the toolkit on FHWA’s website.[71]

In our survey, nearly all state DOTs (47 of 51) stated that they or another transportation entity in their state (MPO or local transportation agency) were aware of the calculator toolkit.

FHWA Has Not Provided Ongoing Communication on the Cost-Effectiveness Tables

In contrast to its communication on the calculator toolkit, FHWA did not provide ongoing and proactive communication on the 2020 cost-effectiveness tables. FHWA generally communicated about the tables from January 2020 through December 2020. FHWA focused its communication on how the 2020 tables were different from the 2015 tables. According to FHWA officials, FHWA communicated with state DOTs and MPOs about the tables through similar formal methods it used for the calculator toolkit, with limited efforts after December 2020.

· Bimonthly newsletter. FHWA’s air quality newsletters provided information on the 2020 tables in three of out 28 newsletters from July through December 2020 but not after this time.

· Conference and meetings. FHWA shared information about the 2020 tables at conferences and at meetings with industry associations in 2020.

· Division offices. Offices disseminated information from headquarters to state DOTs and MPOs when FHWA updated the tables in 2020.

As with the calculator toolkit, FHWA included information about the tables as part of program resources available to state DOTs and MPOs. However, because this type of communication is static, it may require state DOTs and MPOs to seek out the information.

· FHWA’s website. The website includes the 2020 tables and a July 2020 FHWA webinar that discussed the purpose, methodology, limitations, and findings of the tables.

· CMAQ guidance. FHWA’s 2024 interim CMAQ guidance mentions the cost-effectiveness tables, among many CMAQ topics. It also notes the statutory requirement that state DOTs and MPOs consider the cost-effectiveness information in the tables when selecting CMAQ projects.[72]

Federal internal control standards state that agencies should externally

communicate information on a timely basis to help stakeholders achieve their

objectives.[73]

According to FHWA officials, FHWA did not provide ongoing communication on the

cost-effectiveness tables after 2020 because it believed that state DOTs and

MPOs were sufficiently aware of the tables through FHWA’s various methods of

communicating at the time it released them.

FHWA also noted that it included information about the tables on its website and in program guidance. However, FHWA did not continue to proactively communicate about the cost-effectiveness tables. For instance, as noted above, FHWA did not mention them in most of its communication after 2020. As such, state DOTs and MPOs may not know to seek out the cost-effectiveness tables on the website. This contrasts with FHWA’s efforts to communicate on the calculator toolkit. For that tool, FHWA communicated through bimonthly newsletters and other ongoing methods to provide potential users with regular reminders, in addition to providing information on its website and in program guidance. Because FHWA’s approach results in state DOTs and MPOs needing to seek out the cost-effectiveness tables, we do not consider it to be ongoing and proactive.[74]

FHWA’s approach to communication for the cost-effectiveness tables may have contributed to state DOTs and MPOs being less aware of the tables, compared to the calculator toolkit. In our survey, 16 state DOTs—roughly one-third—said they or other transportation entities in their states were unaware of the tables. By comparison, as reported above, nearly all (47) state DOTs reported they or other transportation entities in their state were aware of FHWA’s calculator toolkit.

Providing ongoing, proactive communication to state DOTs and MPOs on the tables could enhance awareness. According to FHWA officials, in recent years there has been a high level of turnover among state DOT officials that manage the CMAQ program. As such, the lack of ongoing communication on the tables may have led to newer staff within state DOTs being unaware of the cost-effectiveness tables as a resource for evaluating and selecting projects. New staff may not know, for example, to look for the tables on FHWA’s website. In addition, state DOTs and MPOs have different cycles for evaluating and selecting CMAQ projects. For example, one MPO we interviewed evaluated and selected CMAQ projects from February through June of a recent year, whereas an MPO in a different state completed this process from January through April of the same year. While one state DOT requests that MPOs submit potential CMAQ projects twice each year, another state DOT does so every 2 years. Ongoing communication from FHWA could provide information to state DOTs and MPOs when they need it.

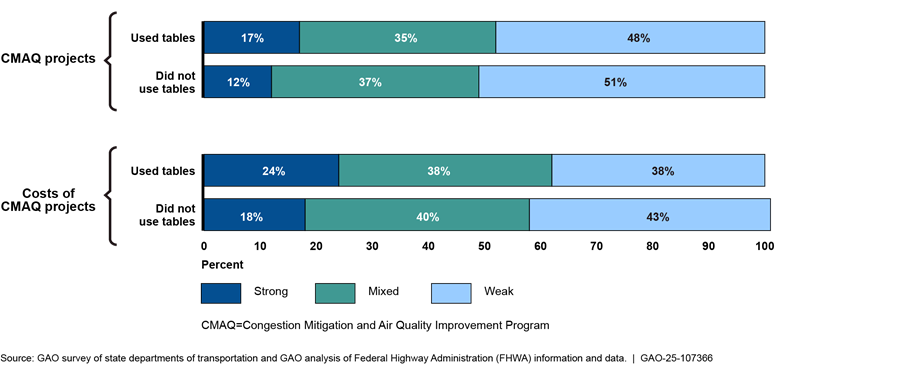

Moreover, greater awareness of the tables could contribute to state DOTs and MPOs selecting CMAQ projects that are more cost effective in reducing emissions of pollutants. While state DOTs and MPOs are not required to use the cost-effectiveness tables when selecting and evaluating CMAQ projects, six state DOTs reported in our survey that they used the tables in fiscal year 2023 or earlier.[75] Our analysis found those six state DOTs selected a greater share of projects with strong cost-effective project types compared to states overall. Specifically, 17 percent of all projects started in fiscal years 2015 to 2023 in these six states had a project type with a strong cost-effectiveness rating from FHWA’s cost-effectiveness tables compared to 12 percent of projects for all other states (see fig. 13). Further, five of those six state DOTs responded to a question in our survey on the helpfulness of the tables and stated that the tables were moderately or very helpful during the project selection process.

Figure 13: Percentage of CMAQ Projects and Funding by Rating of Cost Effectiveness in Reducing Emissions, Fiscal Years 2015–2023, by State Use of Cost-Effectiveness Tables

Notes:

Information from Federal Highway Administration, Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ) Program: 2020 Cost-Effectiveness Tables Update (Washington, D.C., July 2020) and data from FHWA CMAQ project data.

Percentages may not total to 100 percent due to rounding.

States have up to 3 years after the end of the fiscal year in which funds are apportioned to obligate the funds. Our analysis considers projects in the first year that they were funded and any project costs in subsequent years are included in that first year. In addition, our analysis does not include project costs from other sources. This analysis considers the percentage of CMAQ funds after accounting for transfers between CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs and CMAQ funds spent on projects eligible for the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program.

The 2020 tables classify project types with strong cost effectiveness as those that cost less than $2.8 million per ton of emissions reduced across all CMAQ pollutants, mixed cost effectiveness as those that cost between $2.8 and $8.8 million per ton of emissions reduced across all CMAQ pollutants, and weak as those costing $8.8 million or more per ton across all CMAQ pollutants.

FHWA officials told us FHWA plans to publish an update to the cost-effectiveness tables in 2025 and that the agency plans to use similar approaches to communicating about those updated tables as it did with the 2020 tables. However, that approach limited communication to the 6-month period after FHWA published the tables in 2020 and, therefore, may have limited state DOTs’ and MPOs’ awareness of the tables. Ongoing communications about the tables, in addition to information on FHWA’s website, could increase state DOT and MPOs awareness and use of the forthcoming tables.

Conclusions

CMAQ supports transportation projects that address vehicle emissions of pollutants to help states meet federal air quality standards set pursuant to the Clean Air Act. Per statute, FHWA developed and updated cost-effectiveness tables to help state DOTs and MPOs consider the cost effectiveness of reducing emissions when selecting CMAQ projects.

However, most CMAQ projects we analyzed were not of project types that FHWA found to be the most cost effective at reducing emissions. Moreover, nearly one-third of state DOTs responded in our survey that they were unaware of the cost-effectiveness tables, and FHWA’s formal communications on the tables stopped 6 months after FHWA published the most recent iteration in 2020. Providing ongoing communication on the cost-effectiveness tables will help ensure that state DOTs and MPOs are aware of the tables and the statutory responsibility to consider them. Such communication is especially important as staff changes at state DOTs and given the varied timing and processes states have for selecting CMAQ projects.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Administrator of FHWA should provide ongoing formal communications to state DOTs and MPOs on the CMAQ cost effectiveness tables beyond their initial release, including information on the statutory requirement that state DOTs and MPOs consider the tables when selecting CMAQ projects. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Transportation and EPA for review and comment. The Department of Transportation provided a letter, reproduced in appendix IV, in which it agreed with our recommendation. The Department of Transportation also provided technical comments that we incorporated as appropriate. EPA did not have any comments.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Transportation, the Administrator of the EPA, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at repkoe@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Elizabeth Repko

Director, Physical Infrastructure Issues

This report examines (1) how states have used Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Improvement Program (CMAQ) funds since fiscal year 2015, (2) the emissions outcomes of CMAQ projects since fiscal year 2015 and how the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) tracks outcomes, (3) the cost effectiveness of CMAQ projects at reducing emissions since fiscal year 2015 according to available FHWA data and reports, and (4) the extent to which FHWA has communicated to state departments of transportation (DOT) and metropolitan planning organizations (MPO) about FHWA tools for evaluating emissions reductions and cost effectiveness of CMAQ projects.

To inform all objectives, we reviewed relevant statutes and FHWA documents such as CMAQ guidance. We also interviewed officials with FHWA, the Environmental Protection Agency, and relevant industry associations including organizations representing state DOTs, MPOs, and state air quality agencies. Across objectives, our scope was the 50 states and Washington, D.C. (collectively referred to as 51 states), as they were the recipients of CMAQ funding for fiscal years 2015 to 2023, the latest fiscal year for which CMAQ project data were available at the time of our review.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with officials with a non-generalizable sample of relevant agencies in six selected states regarding use of CMAQ funds, FHWA’s calculator toolkit and cost-effectiveness tables, outcomes of CMAQ projects, and other topics. We selected states (California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Texas) to obtain a range of the following characteristics: population, geographic location, extent of attainment of federal air quality standards, and extent of transfers to other federal-aid highway formula programs.

In each state, we aimed to interview the state DOT, two MPOs, the FHWA division office, and the state air quality agency. However, we did not interview all entities in all states as in some cases it was not relevant to do so. For example, in recent years one state used its entire CMAQ apportionment on Surface Transportation Block Grant (STBG)-eligible projects, so we did not interview any MPOs or the state air quality agency. In another state, because only one MPO receives CMAQ funding from the state DOT, we did not interview a second MPO in the state. In some other cases, entities we reached out to for interviews declined to meet with us. Specifically, two state air quality agencies declined to meet with us, with one citing a lack of involvement with CMAQ. In total we met with six state DOTs, six FHWA division offices, three state air quality agencies, and nine MPOs. Following these interviews, we conducted a content analysis to determine trends in responses.

Analysis of FHWA Financial Data

To describe how states have used CMAQ funds since fiscal year 2015, we analyzed financial data from FHWA’s Financial Management Information System that FHWA provided to us in April and October 2024. We reviewed data on transfers between CMAQ and other eligible federal-aid highway formula programs with CMAQ-apportioned funds for fiscal years 2015 through 2024, the latest fiscal year for which funds were available. As the data included both transfers to and from CMAQ, we calculated the net transfers between CMAQ and other programs. We also analyzed separate data on CMAQ apportionments by fiscal year, provided to us by FHWA, to determine the net percentage of CMAQ apportionments transferred between CMAQ and other programs. To determine the reliability of these data, we reviewed FHWA documentation on the database, interviewed FHWA officials, and manually reviewed the data for any obvious missing data, errors, or outliers. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for reporting on transfers of funds between CMAQ and other federal-aid highway formula programs.

Analysis of FHWA’s CMAQ Project Data

To describe how states used CMAQ funds and the emission reduction outcomes of CMAQ projects, we analyzed data from FHWA’s CMAQ project database on CMAQ projects for fiscal years 2015 through 2023, the latest year for which data were available. According to FHWA guidance, state DOTs and MPOs report annually on CMAQ obligations and deobligations taking place in each fiscal year. We downloaded the data from FHWA’s website. We selected 2015 as the first year for our analysis because the database used different project categories prior to that year. There were 13,922 project records in the database for fiscal years 2015 through 2023. Because state DOTs and MPOs can fund CMAQ projects over multiple years, we used the project identification field to combine individual project data on costs and estimated emissions data over multiple years. This resulted in 9,318 projects with a unique project identification number. We analyzed CMAQ project data to determine trends in the categories of projects funded over time, project costs, and estimated emissions reductions.[76]