TRANS-ALASKA PIPELINE

Clarifying the Roles of Joint Pipeline Office Agencies Would Enhance Safety Oversight

Report to congressional requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Elizabeth Repko at repkoe@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107390, a report to congressional requesters

Clarifying the Roles of Joint Pipeline Office Agencies Would Enhance Safety Oversight

Why GAO Did This Study

In 1989, the supertanker Exxon Valdez spilled over 11 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound. Since its formation in response to this incident, JPO has played a critical role in coordinating TAPS oversight among federal and state agencies. Almost 35 years after the spill, some stakeholders have expressed concern that JPO no longer effectively coordinates safety oversight.

GAO was asked to review changes in JPO’s activities, as well as JPO’s collaborative efforts. This report (1) describes how JPO’s safety oversight activities have changed since 1990, and (2) evaluates the extent to which JPO’s safety oversight activities align with leading collaboration practices.

GAO reviewed documents and interviewed officials from four federal and four Alaska state JPO agencies. GAO conducted site visits in Valdez and Anchorage, Alaska. GAO also analyzed PHMSA data on pipeline accidents; reviewed relevant statutes and regulations; and interviewed 13 stakeholders from industry, safety, environmental, and other groups. In addition, GAO compared JPO’s safety oversight activities with leading collaboration practices.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that BLM, in collaboration with other JPO agencies, (1) redefine and document the intended outcomes of JPO’s safety oversight activities, and (2) clarify and document agencies’ roles and responsibilities, including identifying any potential gaps in safety oversight. The Department of the Interior did not provide comments on the report.

What GAO Found

The Joint Pipeline Office (JPO) coordinates oversight of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) among six federal agencies—including the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM), which is the lead federal agency and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA)—as well as six Alaska state agencies. TAPS includes an 800-mile pipeline and the Valdez Marine Terminal, where the oil is loaded onto tankers. Since JPO’s formation in 1990, member agencies have scaled back their approach to joint oversight and reporting. JPO agencies initially shared a physical office and published public reports on their joint monitoring activities. Starting in 2005, JPO reduced its joint activities and public reporting due to fewer projects along the pipeline and shifts in federal roles. In recent years, individual JPO agencies have continued to provide oversight and JPO has served as a forum for participating agencies to share information and coordinate oversight.

GAO found that JPO’s activities generally align with five of eight leading practices that are critical for effective interagency collaboration, such as identifying and sustaining leadership and including relevant participants. However, JPO’s activities do not align with three leading collaboration practices: defining common outcomes, clarifying roles and responsibilities, and updating written agreements. Specifically, JPO no longer works toward several intended outcomes that it documented in 2008, including producing public reports. In addition, some JPO agencies and stakeholders said JPO members’ roles and responsibilities were unclear and raised concerns about possible gaps in oversight, especially at the Valdez Marine Terminal. Redefining and documenting the intended outcomes of JPO’s oversight activities, such as those aiming to inform the public of its oversight efforts, would help JPO agencies work toward shared goals. In addition, clarifying and documenting participating agencies’ roles and responsibilities would help it identify any potential gaps in oversight that could affect safety.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

ADNR |

Alaska Department of Natural Resources |

|

BLM |

Bureau of Land Management |

|

The Council |

Prince William Sound Regional Citizens Advisory Council |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

EPA |

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency |

|

JPO |

Joint Pipeline Office |

|

PHMSA |

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration |

|

TAPS |

Trans-Alaska Pipeline System |

|

The Terminal |

Valdez Marine Terminal |

|

USCG |

United States Coast Guard |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 12, 2025

The Honorable Lisa Murkowski

Chair

Subcommittee on Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Dan Sullivan

United States Senate

On March 24, 1989, the maritime supertanker Exxon Valdez struck a reef and spilled over 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound. The Exxon Valdez contained oil extracted from Alaska’s North Slope and transported by the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), which includes an 800-mile pipeline and the Valdez Marine Terminal (the Terminal), where the oil is loaded onto tankers. Following this catastrophic spill, the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 established new requirements, including the issuance of more stringent regulations for preventing and responding to maritime oil pollution incidents.[1] Within Alaska, the act also permitted a local organization, the Prince William Sound Regional Citizens’ Advisory Council (the Council), to monitor and advise on the environmental safety of the Terminal’s facilities and oil tankers operating in the area.

Also in response to the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (ADNR) formed the Joint Pipeline Office (JPO) in 1990 to better coordinate among 12 federal and Alaska state agencies that oversee TAPS. JPO aimed to work proactively with the oil and gas industry in Alaska to ensure the safe operation of TAPS, environmental protection, and continued transportation of oil and gas in compliance with legal requirements.[2] Almost 35 years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill, in an April 2023 letter to Congress, the Council expressed concerns that JPO no longer effectively coordinated oversight of TAPS safety.

You asked us to review how JPO’s activities have changed since 1990, and the extent to which JPO members have effectively collaborated to ensure the safety of TAPS. This report

1. describes how JPO’s safety oversight activities have changed since 1990, and

2. evaluates the extent to which JPO’s safety oversight activities align with leading collaboration practices.

To address both objectives, we selected the JPO agencies with oversight roles that most closely align with safety oversight of TAPS.[3] Specifically, we selected four federal agencies: BLM, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA), United States Coast Guard (USCG), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). We also selected four Alaska state agencies: ADNR, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development, and Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation.[4] We interviewed officials and reviewed documentation from the eight selected JPO agencies, including the minutes of JPO meetings from January 2020 to September 2024. In August 2024, we conducted site visits to Valdez and Anchorage, Alaska, to meet with federal and state officials and stakeholders and visit the Terminal and TAPS control center. In addition, we analyzed PHMSA data on accidents on hazardous liquid pipelines from 2015 through 2025.[5] We assessed the reliability of the data by reviewing documents and interviewing PHMSA officials, and we determined the data to be sufficiently reliability for the purposes of our reporting objectives.

We reviewed applicable federal and Alaska state statutes, regulations, and administrative orders and coordinated with the Alaska Division of Legislative Audit. We also interviewed selected stakeholders to obtain external perspectives on TAPS oversight. We selected stakeholders that have experience with or knowledge of JPO or the TAPS regulatory landscape, and historical knowledge of these aspects from 1990 through 2024. We selected 13 stakeholders representing three groups relevant to safety oversight of TAPS: 1) five stakeholders representing the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company (which operates TAPS), an industry association, and former Alyeska employees; 2) four stakeholders representing environmental, safety, and technical groups and experts, including the Council; and 3) four former JPO officials from federal and Alaska state agencies.

To evaluate the extent to which JPO’s safety oversight activities align with leading collaboration practices, we analyzed JPO documents and interviews with JPO agency officials. Specifically, we compared JPO agency responses and documentation with each of eight key collaboration practices identified in our prior work.[6] Using this evidence, we determined whether JPO generally aligns or does not align with each collaboration practice.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

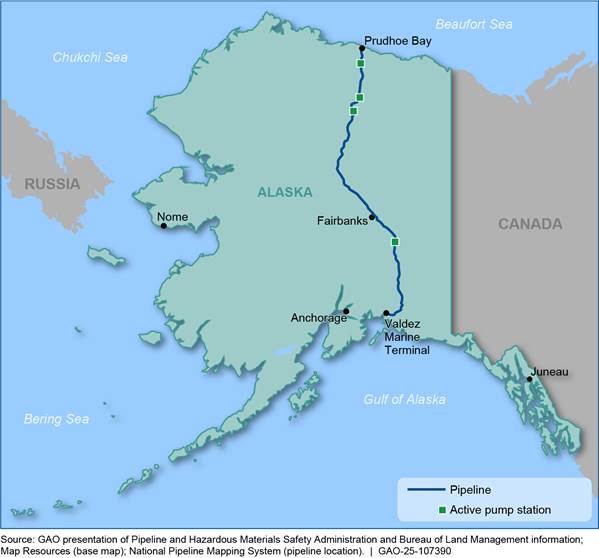

TAPS Characteristics and Recent Safety Record

Built between 1975 and 1977, TAPS starts north of the Arctic Circle at Prudhoe Bay Oil Field and extends 800 miles to the Port of Valdez in Prince William Sound, Alaska. The pipeline has a 48-inch diameter and crosses arctic permafrost, three mountain ranges, about 800 rivers and streams, three known seismic fault zones, and federal, state, and private lands. Approximately 420 miles of the pipeline was constructed aboveground and rests on vertical supports to mitigate damage from permafrost. The remainder of the pipeline was constructed belowground.

A series of four pump stations help move the oil from Prudhoe Bay to the Terminal at the Port of Valdez (see fig. 1). Although TAPS was originally designed with 12 pump stations, only 11 were constructed.[7] Due to decreased oil throughput and operational improvements along the system, seven of the pump stations have been decommissioned or now exist as dedicated spill response bases. Today, there are four operating pump stations, one relief station, and two dedicated spill response bases. Since it began operation in 1977, TAPS has transported 18.9 billion barrels of oil.

Note: We estimated the location of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System using publicly available pipeline maps from the National Pipeline Mapping System on Oct. 22, 2024.

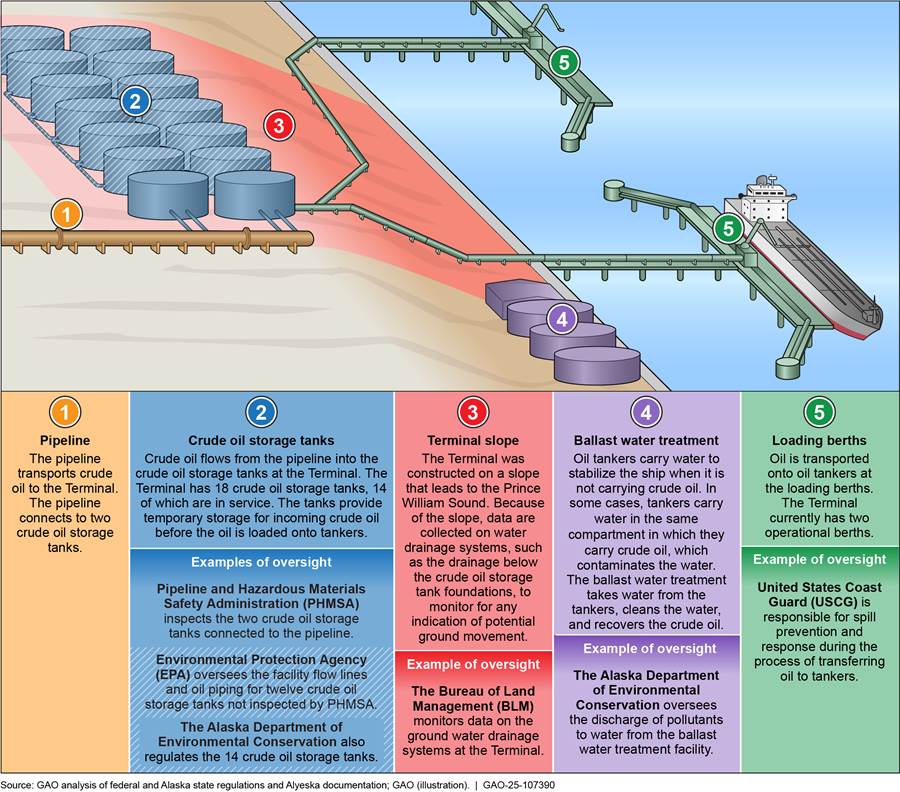

TAPS ends at the Terminal, which was designed to load oil onto tanker ships and provide temporary storage capacity to help manage the flow of oil. Originally, the Terminal operated with four loading berths and 18 crude oil storage tanks. Currently, it operates with two loading berths, 14 crude oil storage tanks in service, and a working inventory capacity of 6.6 million barrels of crude oil. The Ship Escort/Response Vessel System was established in 1989 after the Exxon Valdez spill. This system monitors vessel traffic and provides tug escorts to tankers traveling through Prince William Sound, and is equipped to recover 300,000 barrels of oil in the first 72 hours of an oil spill. Spill response equipment and crews are staged in areas around Prince William Sound.

Alyeska, a private corporation, operates TAPS for the owner companies and has its own permanent staff. TAPS is owned by three companies: ExxonMobil Pipeline Company LLC, which owns 21 percent; ConocoPhillips Transportation Alaska, Inc, which owns 30 percent; and Harvest Alaska, LLC (Hilcorp), which owns 49 percent and acquired its shares from BP in 2019. The owner companies approve and fund Alyeska’s budget.

According to PHMSA data, Alyeska had two accidents along the pipeline impacting people or the environment from 2015 to 2025.[8] During this period, Alyeska had a better accident rate than half of the other hazardous liquid pipeline operators with 300 miles or more of pipeline. One 2022 accident, an oil spill, met PHMSA’s definition of an accident impacting people or the environment because it was not entirely contained on operator-controlled property, and it released more than five barrels of oil outside a high consequence area.[9] The second accident, in 2016, met the definition because vapors ignited during an inspection at a pump station.

In addition, safety incidents have occurred at the Terminal. For example, in 2022, a series of vapor leaks were discovered on 12 of the 14 crude oil storage tanks at the terminal. Following the vapor leaks, the Council commissioned a report reviewing safety risks at the Terminal.[10]

Changes, such as decreased oil throughput and thawing permafrost, have impacted the operation of TAPS.

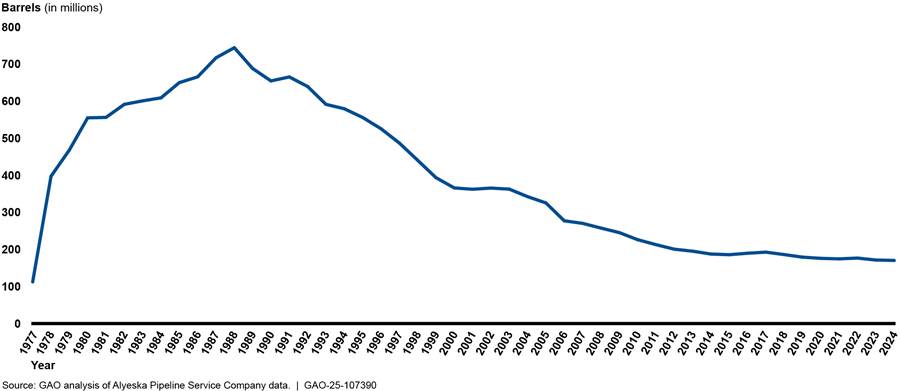

· Decreased oil throughput. Due to decreased North Slope oil production, TAPS throughput has decreased from around 744 million barrels in 1988 to 170 million barrels in 2024 (see fig. 2). As a result, the oil takes longer to move through the pipeline and gets colder. As crude oil slows and cools, water begins to separate from the oil and accumulate at the bottom of the pipeline, increasing the risk of corrosion. In addition, the colder oil increases the amount of wax that sticks to the pipe walls, which can also increase corrosion. Alyeska addresses these issues by allowing frictional heat to build in the crude oil stream and operating a mainline heating system at one location and mobile heaters at two other locations on TAPS, among other efforts.

· Thawing permafrost. Thawing permafrost jeopardizes the structural integrity of the pipeline due to settling of vertical supports holding up elevated portions of the pipeline. To address this, Alyeska implemented mitigation measures, including cooling the subsurface to maintain permafrost conditions and replacing and redesigning vertical supports.

TAPS Oversight

The foundational federal requirements governing TAPS are contained in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act, enacted in 1973, and the 2003 renewal of the TAPS Agreement and Grant of Right-of-Way (right-of-way agreement) from 1974.[11] This agreement governs the construction, operation, and maintenance of the pipeline on federal lands and is administered by BLM. The agreement allows BLM to request data related to the construction, operation, and maintenance of TAPS and monitor certain aspects of TAPS. For example, BLM collects data on aspects of the Terminal’s surface water drainage system, such as the drainage below crude oil tank foundations. It also requires that Alyeska reimburse BLM for all reasonable oversight costs associated with monitoring TAPS. A similar 2002 renewal of a state agreement from 1974 governs TAPS construction, operation, and maintenance on state and certain private lands and is administered by ADNR.[12] Similar to BLM, ADNR oversight activities related to TAPS are reimbursed by Alyeska. ADNR and BLM renewed the state and federal right-of-way agreements in 2002 and 2003, respectively.[13]

Following the Exxon Valdez oil spill, the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 required a regional citizen’s advisory council to be responsible for environmental monitoring of the terminal facilities in Prince William Sound and associated crude oil tankers. Council members represent Alaska communities and organizations that were affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill, including aquaculture, commercial fishing, Alaska Native, recreation, environmental, and tourism groups. Under the Council’s contract with Alyeska, Alyeska provides funding for the Council’s eligible expenses for operations, technical studies, and expert support.

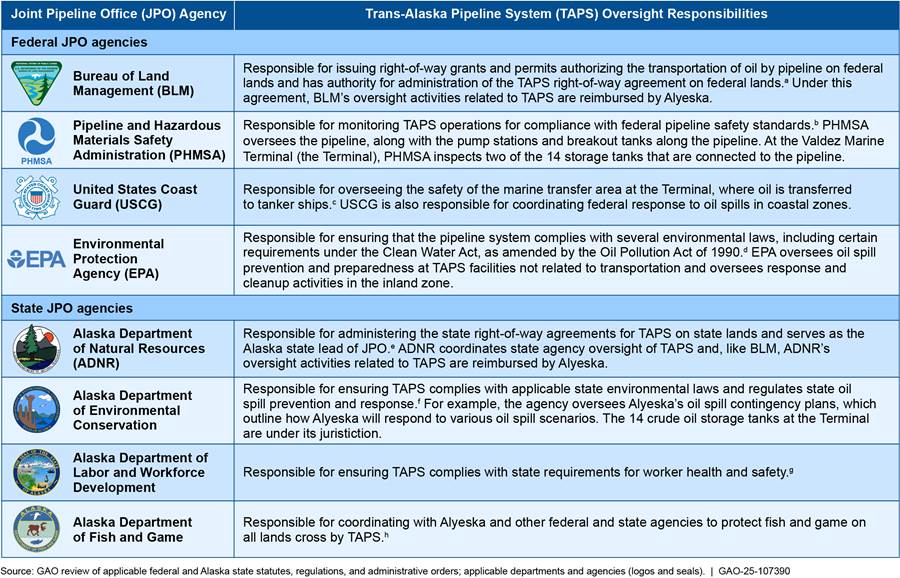

In 1990, BLM and ADNR created JPO to better coordinate federal and state regulatory efforts. JPO is led by BLM and ADNR and consists of six federal and six state agencies. Of these 12 agencies, eight are primarily involved with safety oversight of TAPS (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Responsibilities of Selected Joint Pipeline Office (JPO) Agencies Involved in Safety Oversight

aBLM’s authorities related to TAPS oversight are under the Trans-Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act of 1973, Pub. L. No. 93-153, 87 Stat. 584 (1973) (codified as amended at 43 U.S.C. § 1651 et seq.), and the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, Pub L. No. 66‑146, 41 Stat. 437 (codified as amended at 30 U.S.C. § 181 et seq.).

bPHMSA’s general authority over pipeline safety is codified at 49 U.S.C. § 60101 et seq. PHMSA’s regulations governing the transportation of hazardous liquids by pipeline are located in 49 C.F.R. Part 195.

cUSCG’s general authorities related to TAPS are under 46 U.S.C. § 70011 and 33 U.S.C. § 1321. USCG’s regulations governing facilities transferring oil or hazardous material in bulk are located in 33 C.F.R. Part 154. Its maritime security regulations located in 33 C.F.R. Part 105 also apply to the Terminal.

dEPA has authority and has been delegated certain authorities related to TAPS oversight from the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, as amended by the Oil Pollution Act of 1990, and known as the Clean Water Act. See Pub. L. No. 92-500, 86 Stat. 816 (1972); Oil Pollution Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-380, 104 Stat. 484 (1990); Exec. Order 12777, Implementation of Section 311 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of October 18, 1972, as Amended, and the Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (Oct. 22, 1991). Relevant EPA regulations governing oil pollution prevention and contingency planning are located in 40 C.F.R. Parts 112 and 300.

eADNR’s authority related to TAPS oversight is under Chapter 35 of Title 38 of Alaska Statutes (Right-of-Way Leasing Act) and Alaska Administrative Order No. 134.

fAlaska Department of Environmental Conservation’s authority related to TAPS oversight is under Chapter 4 of Title 46 of Alaska Statutes (Oil and Hazardous Substance Pollution Control), and relevant regulations governing oil pollution control are located in Chapter 75 of Title 18 of the Alaska Administrative Code.

gAlaska Department of Labor’s authority related to TAPS oversight is under Chapter 60 of Title 18 of Alaska Statutes.

hAlaska Department of Fish and Game’s statutory authority related to TAPS oversight is under Chapter 5 of Title 16 of Alaska Statutes.

Federal and Alaska state JPO agencies oversee various aspects of the Terminal (see fig. 4). For example, BLM, PHMSA, EPA, USCG, and the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation oversee aspects of the crude oil storage tanks.

Figure 4: Flow of Crude Oil Through the Valdez Marine Terminal (the Terminal) and Examples of Federal and Alaska State Agency Oversight.

We issued two reports in the early 1990s regarding government oversight of TAPS.[14] In 1991, we reported that the principal federal and state regulatory agencies did not have the systematic, disciplined, and coordinated approach needed to regulate TAPS. We noted that the formation of JPO was a positive step toward more effective TAPS oversight, and recommended several additional steps for oversight agencies, such as assessing Alyeska’s corrosion and leak- detection systems.[15] In 1995, we reported that federal and state oversight of TAPS had improved due to JPO’s coordination efforts.

JPO Has Scaled Back Joint Safety Oversight Activities Since 1990, But Participating Agencies Continue to Share Information and Coordinate Oversight

Since JPO’s formation in 1990, JPO agencies have scaled back their approach to joint oversight and reporting but continued to share information and coordinate oversight. From 1990 to 2004, JPO agencies shared a physical office and published public reports on their joint monitoring activities. From 2005 through 2017, JPO reduced its joint activities and public reporting due to fewer projects occurring along the pipeline and shifts in federal roles. In recent years, JPO has served as a forum for participating agencies to share information and coordinate oversight.

1990–2004: JPO Agencies Conducted and Reported on Joint Oversight Activities and Shared a Physical Office

According to three former JPO officials and an industry stakeholder, JPO conducted joint oversight activities along the pipeline and at the Terminal from 1990 to 2004. JPO’s initial oversight activities focused on producing Comprehensive Monitoring Program Reports, reviewing pipeline projects, preventing and responding to oil spills, preparing for the renewal of the TAPS right-of-way agreement, and responding to Alyeska employee concerns.

· Comprehensive Monitoring Program reports. JPO agencies collaborated on a Comprehensive Monitoring Program. The aim of the program was to encourage continual improvement in Alyeska’s management of TAPS construction, operations, and maintenance activities, and to ensure environmental protection, public safety, and pipeline integrity, according to a prior Comprehensive Monitoring Program report. A former JPO official said the program began as an effort to prevent future problems with corrosion in response to deficiencies raised by Alyeska employees. JPO issued 12 Comprehensive Monitoring Program reports, which periodically communicated to the public findings and recommendations based on JPO monitoring efforts.[16] For example, for a 1998 report, JPO selected eight TAPS projects from the previous year for in-depth review and evaluation. JPO conducted inspections and reviewed project documents to evaluate whether the projects followed procedures and improved pipeline system integrity. Topics covered by other reports included TAPS employee safety and environmental protection.

· Reviewing pipeline projects. Two former JPO officials and an industry stakeholder said that JPO conducted comprehensive reviews of Alyeska projects, including the company’s “Strategic Reconfiguration” initiative. Beginning in 2001, the goal of this initiative was to electrify and remotely control the pipeline from a consolidated operations center, among other things. This process was intended to reduce physical infrastructure, simplify operations, and accommodate decreases in pipeline throughput. As a part of strategic reconfiguration, Alyeska replaced diesel-fueled, turbine driven pumps with electrically driven pumps at pump stations. According to BLM officials, this process concluded in 2015 when pump station 1 was completed.

· Preventing and responding to oil spills. JPO coordinated multiple agency reviews and approval of oil spill contingency plans for the pipeline and Terminal. In addition, JPO participated in oil spill drills.

· Preparing for the renewal of the TAPS right-of-way agreement. The original state and federal right-of-way agreements for TAPS were set to expire after 30 years in 2002 and 2003, respectively. In 2002 and 2003, federal agencies, state agencies, and Alyeska renewed the right-of-way agreements to continue for another 30 years. According to a former JPO official, JPO hired a lawyer to review the right-of-way agreements and a consultant to complete an environmental impact statement in preparation for the renewals.

· Responding to Alyeska employee concerns. Following congressional hearings about safety concerns from Alyeska employees in the early 1990s, JPO established a program to identify and resolve employee concerns and hired a consultant to assess the safety of the pipeline.[17] JPO created a toll-free hotline for employees to report safety, environmental, and pipeline integrity issues. A former JPO official said that JPO worked with Alyeska closely to address the management and electrical code deficiencies that the consultant identified.

In addition to publishing Comprehensive Monitoring Program reports, JPO communicated with the public through a bi-monthly newsletter, joint annual reports, and a website. A former JPO official said that the JPO office included staff who were tasked with external communications. The website, hosted by the Department of the Interior, included agency contact information, links to JPO monitoring and annual reports, and the newsletter Coming Down the Pipe. This newsletter included articles about oil spill drills, public notices and comment periods, and information about upcoming public meetings.

During this period, JPO agencies shared a physical office in Anchorage, where staff from participating state and federal agencies conducted joint oversight activities. BLM and ADNR’s expenses for the shared office were reimbursed by Alyeska, as permitted by their respective right-of-way agreements. A former JPO official said that state and federal agencies within the office shared an information technology system and administrative staff. JPO reports were signed jointly by JPO or JPO staff, rather than individual contributing agencies.

2005–2017: JPO Scaled Back Its Activities Due to Fewer Projects Requiring Oversight and Shifts in Federal Roles

According to stakeholders, JPO scaled back its oversight activities during the period from 2005 through 2017 due to a decrease in TAPS projects requiring oversight. Stakeholders said that the number of projects requiring JPO oversight decreased during this period, including when Alyeska’s Strategic Reconfiguration concluded. State agency officials said that the remote control of the pipeline allowed engineers to identify pump station issues from the control center in Anchorage and make fewer field inspections. According to officials from an Alaska state agency, JPO did not meet as regularly from 2008 to 2017, due in part to the decrease in TAPS projects. During this period, JPO closed the physical office in which staff from state and federal participating agencies were collocated. In 2010, BLM moved into separate offices in Anchorage and were no longer collocated with other federal JPO agencies. According to officials from an Alaska state agency, most state JPO agencies moved to a shared state building. Former JPO officials said that this move was initiated at the state executive office level.

In addition, JPO oversight of TAPS was impacted by shifts in the roles of PHMSA and BLM:

· PHMSA. In 1990, the DOT Office of Pipeline Safety within the Research and Special Programs Administration oversaw pipeline safety issues for DOT. Between 1990 and 2001, DOT’s authorities were amended enhancing its oversight of pipeline safety, such as increasing inspection requirements. DOT also updated and set more rigorous standards for pipeline safety, including that of TAPS.[18] For example, in 1995, DOT required operators of certain hazardous liquid pipelines to carry out a written damage prevention program. According to PHMSA officials, DOT integrated a review of these damage prevention programs into its 3-year inspection cycle for TAPS; this damage prevention program review remains in place for inspections. Within the next 4 years, the agency adopted new safety standards for certain crude oil storage tanks and leak detection. DOT also established new operator qualifications for the pipeline workforce. In 2000, the Research and Special Programs Administration required the operators of some hazardous liquid pipelines, including TAPS, to develop and implement pipeline integrity management programs, which cover those pipelines that could affect high consequence areas.[19]

In 2004, the Research and Special Programs Administration was abolished, and the Office of Pipeline Safety was moved to the newly established PHMSA.[20] A former industry stakeholder said that in the early 2000s, PHMSA began to take a more active and independent role in TAPS oversight, in addition to its activities with JPO.

· BLM. From 1990 to 2004, BLM conducted inspections, hired consultants, and employed engineers to inspect the pipeline and Terminal. According to a former industry official, BLM and JPO staff were often present at the Terminal to directly observe construction and other projects. BLM officials said that after 2005, the agency began reviewing its authorities and shifting its focus from technical oversight to permitting, in part because PHMSA was taking a more active role in oversight of the operation and maintenance of the pipeline.

During this period, JPO ended much of its external reporting. JPO published its last joint annual report in 2005. In subsequent years, BLM and ADNR published separate annual reports on TAPS oversight. In addition, JPO published six Comprehensive Monitoring Program reports in this period, with its final one in 2007. The reports reviewed Alyeska’s programs on maintenance, environmental oversight, and compliance with the right-of-way agreement. JPO published its last newsletter in 2009. According to an archived version of the website, the page was last updated in 2011 before it was shut down.

Since 2018, JPO Has Operated as a Forum for Sharing Information and Coordinating Oversight

Since 2018, JPO has operated as a forum for sharing information and coordinating oversight. During this period, JPO agencies have continued to perform oversight duties. For example, according to PHMSA officials, PHMSA performs integrated inspections of the entire pipeline at least every 3 years and uses a risk-based assessment for additional inspections. Officials from four JPO agencies said that JPO continues to participate in spill drills, where agencies practice their coordinated response to an oil spill.

According to BLM and ADNR officials, JPO meets regularly to discuss “hot topics” and for coordination meetings. In addition, JPO leadership meets with Alyeska in a Senior Land Managers Meeting. According to JPO officials, they generally conduct each of these meetings on a monthly basis.

· Hot topics meetings. These meetings are open to all JPO agencies and cover topics related to TAPS activities, among other things. According to ADNR officials, these meetings are led by Alyeska. According to meeting minutes, topics in the past have included strategies to prevent ice buildup along the pipeline, snow removal plans at the Terminal, and results from internal inspections.

· Coordination meetings. These meetings are a forum for all JPO agencies to provide updates about their oversight of TAPS. JPO agencies use these meetings to discuss stakeholders’ concerns and coordinate agencies’ inspections of TAPS, among other things. PHMSA officials said that JPO meetings are helpful for coordinating their individual reviews of issues along the pipeline and Terminal with other agencies. Similarly, EPA officials said that EPA staff share updates during JPO meetings and coordinate visits to the Terminal with other agencies as needed.

· Senior Land Managers Meeting. In these meetings, BLM, ADNR, and Alyeska identify key issues that require clarity or follow-up and develop agendas for JPO’s hot topics meetings. For example, according to meeting minutes, the group has discussed sharing information online between Alyeska and JPO agencies, planned construction, and other topics.

In 2018, BLM reorganized to transition staff away from performing engineering reviews to managing land and permits. As part of this reorganization, BLM reduced the number of TAPS engineering positions and consolidated the remaining staff under the Branch of Lands and Realty, which manages public land transactions, including leases, permits, and right-of-way authorizations. BLM reduced the number of staff located in Valdez from three to one staff position. BLM refocused the remaining staff member’s duties from technical oversight to permitting, according to a BLM official.

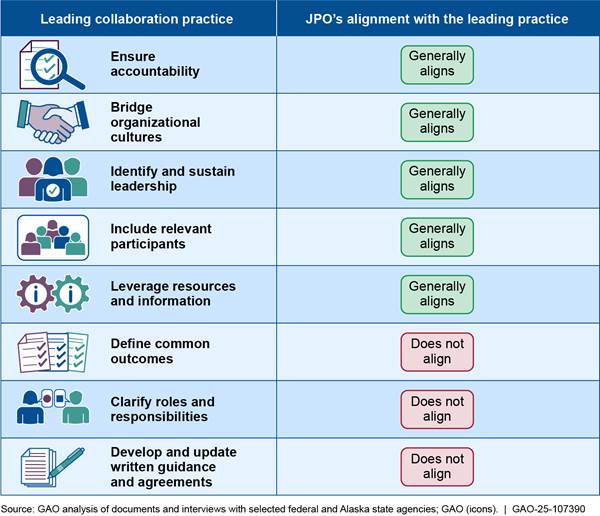

JPO’s Activities Do Not Align with Leading Collaboration Practices Related to Outcomes, Roles, and Documentation

We found that JPO’s activities generally align with five of eight leading practices that we identified in prior work as being critical for effective interagency collaboration.[21] However, JPO’s activities do not align with three of these practices related to outcomes, roles, and documentation (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: Assessment of the Extent to which the Interagency Oversight Activities of the Joint Pipeline Office (JPO) Align with Leading Collaboration Practices

JPO’s Activities Generally Align with Five Leading Collaboration Practices

We found that JPO’s interagency collaboration activities generally align with the following five leading collaboration practices:

· Ensure accountability. Ensuring accountability better enables collaborating agencies to encourage participation, assess progress, and make necessary changes. Officials from seven of the eight selected JPO agencies said that JPO promotes accountability. For example, officials from four agencies said that JPO’s regular meetings are an opportunity to discuss agencies’ progress in TAPS oversight. Further, officials from three selected JPO agencies noted that individual agencies have their own accountability mechanisms to track and monitor progress.

· Bridge organizational cultures. Addressing differences between diverse organizational cultures can create the mutual trust that is critical to enhancing and sustaining the collaborative effort. Officials from six of the eight selected JPO agencies said that JPO is effective at bridging organizational cultures. Officials from some JPO agencies said that JPO also collaborates in forums outside of JPO, such as an Alaska regional pollution response organization and Area Contingency Planning committees.

· Identify and sustain leadership. Sustained leadership provides the authority, support, and decision-making capabilities that allow interagency efforts to function, and this leadership facilitates oversight and accountability. BLM and ADNR have been co-leads since JPO was created in 1990. Officials from all eight selected JPO agencies we interviewed said that BLM and ADNR continue to lead JPO.

· Include relevant participants. Including relevant participants helps ensure that collaborating agencies involve everyone that has a stake in the effort. Officials from six of the eight selected JPO agencies said that the agencies relevant to TAPS oversight attend JPO meetings. Our analysis of JPO meeting minutes confirmed that the JPO agencies regularly attended the monthly meetings.

·

Leverage resources and information. Leveraging resources

and information helps collaborating agencies successfully address crosscutting

challenges and opportunities. Officials from five of eight selected JPO

agencies said that JPO effectively leverages resources and information. In

addition to sharing information in meetings, officials from four agencies said

that JPO primarily shares information via email, which was sufficient for the

purposes of JPO.

JPO Has Not Redefined or Documented Its Intended Outcomes, Including Those Aiming to Inform the Public of Its Oversight Efforts

Collaborative efforts between organizations benefit from the leading practices of defining intended outcomes and developing and updating written guidance and agreements.[22] We found that JPO’s interagency collaboration activities do not align with these two leading practices. While JPO documented intended outcomes in 2008, including several aiming to inform the public of its efforts, in many cases it no longer works toward them.

In 2008, JPO agencies signed a memorandum establishing an Operating Agreement, which outlined the goal, purpose, and structure of JPO. This agreement listed several intended outcomes of JPO’s safety oversight, including providing coordinated reviews of all permitting actions and oversight of TAPS; setting oversight priorities; producing public reports; and providing unified communication to the public, industry groups, and other stakeholders. However, JPO has not updated its intended outcomes and no longer works toward these four outcomes.

· Coordinated reviews and oversight. Officials from five of the eight selected JPO agencies said that JPO does not provide coordinated reviews of permitting actions or oversight of TAPS. Instead, officials from four of these five agencies said JPO serves as a forum for agencies to discuss individual agencies’ oversight of operations and permitting actions.

· Oversight priorities. Officials from six of the eight selected JPO agencies said that JPO does not establish administrative, technical, or regulatory oversight priorities. Rather, officials from four of these six agencies said that each agency sets its own priorities for TAPS oversight.

· Public reports. Officials from seven of the eight selected JPO agencies said that JPO no longer issues public reports. Specifically, JPO has not issued public reports since its last Comprehensive Monitoring Program report in 2007 and its last annual report in 2005.

· Unified communication. Officials from four of the eight selected JPO agencies said JPO does not generally provide unified communication to the industry and stakeholders.[23] BLM officials said that the JPO agencies can do so through letters with JPO letterhead signed by multiple JPO agencies. In addition, JPO no longer has a webpage informing the public of its oversight activities and providing access to JPO reports, organizational documents, and contact information.

BLM officials said JPO no longer works toward these outcomes due to changes in regulatory responsibilities and in individual agencies’ roles for TAPS oversight. In addition, JPO has not updated its written agreements to reflect its intended outcomes. JPO drafted an update to the operating agreement in 2023. However, as of February 2025, JPO agencies had not signed the update. To coordinate efforts effectively, we previously found that collaborating agencies should identify opportunities to create buy-in from all parties. Without redefining and documenting the intended outcomes of JPO’s oversight of TAPS, JPO agencies cannot work toward shared oversight goals.

JPO Has Not Clarified or Documented Agencies’ Roles, Including Areas of Oversight

A key leading practice for interagency collaboration is that agencies should work together to define and agree on their respective roles and responsibilities.[24] In doing so, agencies can clarify who will do what, organize their joint and individual efforts, and facilitate decision-making. We found that JPO has not fully clarified or documented JPO agencies’ roles and responsibilities, either for TAPS oversight or within JPO. Specifically, we found that JPO agencies have not updated or agreed on updates to two documents related to roles and responsibilities: (1) a matrix that describes oversight roles and responsibilities for individual agencies, and (2) JPO’s internal structure as documented in the 2008 Operating Agreement.

BLM and PHMSA officials said a 2017 matrix is the most recent document outlining agencies’ oversight roles and responsibilities. However, BLM officials said that BLM also created an internal matrix in 2018. BLM’s 2018 matrix updated its roles and responsibilities to reflect BLM’s transition from performing engineering reviews of TAPS to managing land and permits. The 2018 document also lists regulatory authorities for other JPO agencies, BLM’s planned actions related to those authorities, and recommendations for improvement to TAPS oversight. Although BLM officials said that the 2018 matrix is intended to be an internal document, changes to BLM’s role in the 2018 matrix were based on assumptions about other JPO agencies’ roles and responsibilities. For example, the 2018 matrix notes that PHMSA has taken a larger role in TAPS oversight since PHMSA was created in 2004. BLM provided the 2018 matrix to JPO agencies and received comments from four of the 12 agencies. Officials from six of the eight selected JPO agencies, including PHMSA, said they were unfamiliar with the 2018 matrix.

Further, officials from three selected JPO agencies and some stakeholders said they found agency oversight roles and responsibilities unclear.[25] For example, stakeholders raised concerns about possible gaps in oversight, especially for tank bottom cleaning and deferred maintenance at the Terminal. On August 30, 2023, a fire occurred during tank cleaning at the Terminal. Following the fire, the Council asked JPO to clarify agencies’ oversight in these kinds of incidents. In response, JPO provided a letter signed by three JPO agencies that summarized the responsibilities of five JPO agencies related to tank bottom processing. The letter stated that no single JPO agency had regulatory authority over every aspect of conducting this process. The letter indicated that the five JPO agencies listed did not have specific, if any, regulatory authority over this process. In addition, two stakeholders familiar with the Terminal said that deferred maintenance at the Terminal had increased in recent years, and it was unclear which JPO agency would have the authority to oversee efforts to address deferred maintenance.[26]

The 2008 Operating Agreement outlines agencies’ roles within JPO, including their participation in an Executive Council, a Management Team, and standing as well as ad hoc teams.[27] However, officials from all eight selected JPO agencies said that JPO no longer operates under the structure identified in the 2008 Operating Agreement. For example, officials from four agencies said that JPO no longer has an Executive Council. Officials from a JPO agency said that the operating agreement should be updated to reflect JPO’s current structure.

Given changes to JPO’s structure and uncertainty about roles, clarifying and documenting agencies’ roles and responsibilities within JPO and related to agency oversight could help JPO identify any potential gaps in oversight. Such clarification and documentation would be consistent with recommendations for TAPS oversight that BLM made in its 2018 matrix, which included updating JPO written agreements with changes to agencies’ roles and responsibilities, and examining the impacts of adjusting oversight roles in key areas, such as the Terminal.

Conclusions

Since its formation in 1990 in response to the Exxon Valdez oil spill, JPO has played a critical role in overseeing the 800-mile pipeline and marine terminal that comprise the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. Initially, JPO agencies conducted joint monitoring activities, but as the pipeline’s infrastructure has been modernized and the roles of federal agencies have shifted, JPO’s approach to oversight has changed. Despite these changes, agency officials generally believe that JPO’s current function—as a forum through which participating agencies share information and coordinate activities—facilitates agencies’ effective collaboration on oversight of TAPS. However, JPO’s intended outcomes are unclear, as JPO no longer works toward many of the outcomes it outlined more than 15 years ago. Redefining and documenting the intended outcomes of JPO’s oversight activities, including those aiming to inform the public of its oversight efforts, would enable JPO agencies to work toward shared goals and ensure accountability. Moreover, given the shift in roles of federal agencies over time, it is important that JPO agencies review, agree upon, and document their roles and responsibilities. Clarifying roles and responsibilities would enhance coordination among JPO agencies and help JPO identify any potential gaps in oversight.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following two recommendations to BLM:

The Director of BLM should, in collaboration with other JPO agencies, redefine and document the intended outcomes of JPO’s safety oversight activities, such as outcomes aiming to inform the public of JPO’s oversight efforts. (Recommendation 1)

The Director of BLM should, in collaboration with other JPO agencies, clarify and document JPO agencies’ roles and responsibilities, including identifying any potential gaps in TAPS safety oversight. (Recommendation 2)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of the Interior (Bureau of Land Management), the Department of Transportation (Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration), the Department of Homeland Security (U.S. Coast Guard), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for review and comment. The Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Transportation, and EPA did not have any comments on the report. The Department of the Interior did not provide comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Transportation, the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Administrator of EPA, and other interested parties. In addition, the report will be available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at repkoe@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs are on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Elizabeth (Biza) Repko

Director, Physical Infrastructure

GAO Contact

Elizabeth (Biza) Repko, repkoe@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Sara Vermillion (Assistant Director) and Emily Larson (Assistant Director), Mikey Erb (Analyst in Charge); Natalie Hurd, Josh Ormond, Mary-Catherine P. Overcash, Kathleen Padulchick, Kelly Rubin, and Laurel Voloder made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]See Pub. L. No. 101-380, 104 Stat. 484 (1990) (primarily codified as amended at 33 U.S.C. § 2701 et seq.).

[2]Joint Pipeline Office, Evaluation of Alyeska Pipeline Service Company's Project Performance for TAPS - Comprehensive Monitoring Report (September 1998).

[3]We define safety oversight of TAPS as minimizing the risk of, preventing, and responding to oil spills that could damage the environment or threaten public safety. We define security of TAPS as preventing and responding to sabotage, cyberthreats, etc.

[4]For the purposes of this report, we use the term agency to include executive branch agencies and components within agencies. The four JPO agencies not included in this review are the U.S. Transportation Security Administration, Alaska Department of Public Safety, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Alaska Department of Transportation. We excluded these agencies because they focused either on the security of the pipeline or on other issues unrelated to safety.

[5]PHMSA hazardous liquid pipeline data are available on PHMSA’s website, https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/data-and-statistics/phmsa-data-and-statistics.

[6]GAO, Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington D.C.: May 24, 2023)

[7]Of the 11 pump stations, 10 were active and one was used as a relief station.

[8]PHMSA defines an accident as impacting people or the environment if it meets one of two criteria: (1) regardless of the accident’s location, any of the following occur: a fatality, injury requiring in-patient hospitalization, ignition, explosion, evacuation, wildlife impact, contamination of specific water sources, or damage to public or private, non-operator property; or (2) where the accident’s location is not totally contained on operator-controlled property, any of the following occur: an unintentional release equal to or greater than 5 gallons in a high consequence area, an unintentional release equal to or greater than 5 barrels or more outside of a high consequence area, surface water contamination, or soil contamination.

[9]PHMSA regulations generally define high consequence areas as high population areas, other populated areas, certain navigable waterways, and certain areas unusually sensitive to environmental damage from a hazardous liquid pipeline release. See 49 C.F.R. § 195.450.

[10]Billie Pirner Garde, Assessment of Risks and Safety Culture at Alyeska Valdez Marine Terminal (Washington, D.C.: April 2023).

[11]See Pub. L. No. 93-153, tit. II, 87 Stat. 584 (1973) (codified as amended at 43 U.S.C. ch. 34); Renewal of the Agreement and Grant of Right-of-Way for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and Related Facilities (effective Jan. 22, 2004).

[12]See Renewal and Amendment of Right-of-Way Lease for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and Associated Rights (2002). This state agreement provides that any interest in private land in Alaska that is: 1) acquired by lease, easement, or right-of-way by ADNR or its authorized agent, and 2) required for the purposes of a pipeline right-of-way, will become part of the land covered by the state agreement. See id. § 15; Alaska Stat. § 38.35.130.

[13]The renewed state agreement went into effect on May 2, 2004, and will expire on May 2, 2034. The renewed federal right-of-way agreement went into effect on January 22, 2004, and will expire on January 22, 2034.

[14]GAO, Trans-Alaska Pipeline: Regulators Have Not Ensured That Government Requirements Are Being Met, GAO/RCED‑91‑89 (Washington D.C.: July 19, 1991); and Trans-Alaska Pipeline: Actions to Improve Safety Are Under Way, GAO/RCED‑95‑162 (Washington D.C.: Aug. 1, 1995).

[15]In 1991, we made 15 recommendations and one matter for congressional consideration. Specifically, we made ten recommendations to the Department of the Interior, including to reassess the adequacy of Alyeska’s corrosion prevention efforts, assess Alyeska’s leak detection system, and ensure the JPO provides systematic oversight of TAPS. The Department of the Interior implemented eight of these recommendations. Two recommendations related to establishing oil spill cleanup standards and evaluating technology for future oil spills were closed as not implemented. We made three recommendations to DOT to reassess the adequacy of Alyeska’s corrosion prevention efforts, assess Alyeska’s leak detection system, and ensure the JPO provide systematic oversight of TAPS. We made two recommendations to EPA to ensure the JPO provide systematic oversight of TAPS and revise its regulations related to crude oil storage tanks. These five recommendations were closed as implemented. Finally, we issued a matter for congressional consideration to require Alyeska to fully reimburse JPO agencies for oversight. This matter was closed as not implemented. We did not make any recommendations in 1995.

[16]JPO published 18 Comprehensive Monitoring Program reports: 12 reports between 1997and 2002 and six reports in 2007.

[17]In July 1993 and November 1993, the House Committee on Energy and Commerce's Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations held hearings in response to concerns raised by employees, safety issues identified by congressional staff, and concerns about how JPO was regulating TAPS.

[18]PHMSA’s general authority over pipeline safety is codified at 49 U.S.C. § 60101 et seq. Its regulations governing the transportation of hazardous liquid by pipeline are located in 49 C.F.R. Part 195.

[19]The final rule establishing these regulations became effective in 2001.

[20]In addition to the Office of Pipeline Safety, certain other duties, such as regulating the safe transportation and security of hazardous materials in commerce, were moved to the newly established PHMSA. See Norman Y. Mineta Research and Special Programs Improvement Act, Pub. L. No. 108-426, 118 Stat. 2423 (2004).

[23]Officials from three selected JPO agencies said that JPO generally provides unified communication and officials from one selected JPO agency was unsure whether JPO does so.

[25]Officials from four selected JPO agencies said that roles and responsibilities for TAPS oversight were clear. Officials from one Alaska state agency said that Alaska state agency roles and responsibilities were clear, but they could not comment on the clarity of federal agency roles.

[26]In 2002, Alyeska and JPO signed a memorandum of agreement for Alyeska to, in part, identify and prioritize maintenance activities for new and existing TAPS equipment and systems based on an industry-recognized methodology, such as reliability-centered maintenance. JPO closed this memorandum of agreement in 2010, as Alyeska had fully complied with its provisions.

[27]A 2008 executive council agreement defined the executive council’s structure and responsibilities.