DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

Gaps in Federal Student Aid Contract Oversight and System Testing Need Immediate Attention

Report to Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Marisol Cruz Cain at cruzcainm@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

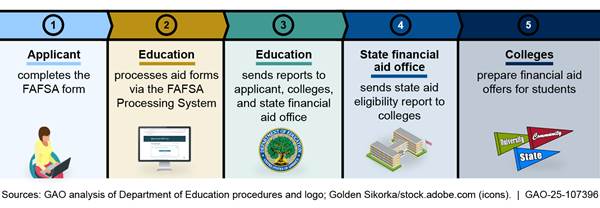

The Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA) manages the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which students and parents submit to determine a student’s eligibility for receiving financial aid. The FAFSA Processing System (FPS)—the system that underpins federal student aid—processes these applications (see figure).

In September 2024, GAO testified that nine of the 25 contractual requirements that defined FPS were not deployed. Examples of the nine requirements not yet deployed included allowing FSA to (1) make corrections to FAFSA applications and (2) modify eligibility rules and requirements. Education officials had stated that these remaining requirements would be deployed by 2026.

However, as of May 2025, Education was unable to provide the status of the complete system. FSA officials said they could not readily provide the status because they were no longer tracking requirements. This raises questions about FSA ensuring required work under the contract is being performed.

Further doubts about contract oversight surfaced when GAO determined that FSA was not validating contractor performance data. Although FSA had established processes for monitoring contractor performance, it did not fully implement them.

In addition, FSA could not demonstrate that contracting officer’s representatives and project management staff had complied with certification requirements. The agency also did not ensure key acquisition staff had specialized training related to the systems development methodology used to develop FPS.

Testing of IT systems is critically important. Although leading practices highlight the importance of thoroughly testing IT systems prior to deployment, FSA did not fully apply these practices. For example, test cases—used to determine whether an application, system, or system feature is working as intended—lacked information that would allow for traceability to underlying requirements. Contributing to this lack of traceability was the absence of agency guidance on what information to include in a test case. In addition, FSA does not have a plan to guide future FPS user testing efforts. This increases the risk that testing will be incomplete and inconsistently executed. Overall, such testing shortfalls can lead to the discovery of significant system deficiencies when deployment occurs.

Why GAO Did This Study

In December 2023, FSA, the largest provider of student financial aid in the nation, deployed a new system with limited functionality to process student aid applications. However, the system—FPS—had availability issues, recurring errors, and long wait times that affected students’ ability to receive aid. Since then, FSA has continued to work to deploy additional functionality.

Among other things, this report addresses the extent to which FSA conducted selected contract oversight activities and applied leading systems testing practices.

GAO examined how FSA tracked the contractor’s progress in meeting contract requirements and compared FSA actions to established contract oversight processes and agency standards. GAO also identified key contract oversight staff for FPS and compared federal certification and training requirements against relevant documentation for these staff. In addition, GAO compared the actions taken by FSA to leading practices for system testing.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making seven recommendations to Education, including improving its contract oversight; establishing a process to ensure contracting staff receive proper certifications and training; and developing appropriate testing guidance, ensuring that FPS testing is linked to requirements, and developing and implementing a plan for testing with system users.

FSA disagreed with portions of the report, generally agreed with four recommendations, and did not indicate agreement or disagreement with the remaining three. As discussed in the report, GAO maintains that all its recommendations are warranted.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

DITAP |

Digital IT Acquisition Program |

|

FAC |

Federal Acquisition Certification |

|

FAC-C |

Federal Acquisition Certification in Contracting |

|

FAC-COR |

Federal Acquisition

Certification for Contracting |

|

FAC-P/PM |

Federal Acquisition Certification for Program and Project Managers |

|

FAFSA |

Free Application for Federal Student Aid |

|

FPS |

FAFSA Processing System |

|

FSA |

Office of Federal Student Aid |

|

FUTURE Act |

Fostering Undergraduate Talent by Unlocking Resources for Education Act |

|

IEEE |

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers |

|

ISIR |

Institutional Student Information Records |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

QASP |

Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan |

|

SLA |

service level agreement |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 3, 2025

The Honorable Bill Cassidy, M.D.

Chair

Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions

United States Senate

The Honorable Tim Walberg

Chairman

Committee on Education and Workforce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Virginia Foxx

House of Representatives

The Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA) is the largest provider of student financial aid in the nation. It manages the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which is used to determine a student’s eligibility for receiving financial aid. The office processes nearly 18 million FAFSA forms (paper and electronic) each year. It also provides approximately $120.8 billion in grant, work-study, and loan funds each year to help students and their families pay for college or career school.

Historically, most FAFSA forms submitted by applicants were processed electronically by FSA’s Central Processing System. In 2019, we reported that this system was among the 10 most critical federal systems in need of modernization.[1] In February 2021, the agency subsequently initiated a project—the Award Eligibility Determination project—to, among other things, develop a system to replace the Central Processing System.[2]

The FAFSA Processing System (FPS)—a key component in the replacement for the Central Processing System—was deployed in December 2023 to process the 2024-2025 FAFSA forms. However, issues encountered by its development contractor led FSA to deploy the system without the full planned functionality. Instead, FSA directed its contractor to focus on including functionality that would allow students and families to submit financial aid applications and delayed other functionality, such as allowing students and colleges to correct errors on those applications.

Shortly after the initial launch of the 2024-2025 FAFSA form, student aid applicants reported availability issues, submission errors, and significant load times,[3] among other things.[4] For example, students that were born in 2000 were unable to proceed past a certain section of the application and graduate students were erroneously informed that they were eligible for Pell Grants. These issues left students and colleges without the information they needed to make important financial decisions about the upcoming school year.

Since then, FSA has launched the 2025-2026 FAFSA form with minimal applicant-reported issues. The 2026-2027 form is scheduled to be launched by October 1, 2025, but it is unclear whether the form will include the full planned functionality.

You asked us to review FSA’s launch of FPS. Our objectives were to determine (1) the status of delivering the complete FPS and the causes of any delays, (2) the extent to which FSA provided contract oversight of the FPS effort, (3) the extent to which the qualifications of key FPS contract and project oversight staff aligned with federal requirements and Education policy, and (4) the extent to which FSA applied disciplined systems testing practices in deploying FPS.

To address the first objective, we requested documentation that would show FSA’s progress towards meeting specific contractual requirements to determine the status of the delivery of the complete FPS system. However, the agency was not able to provide sufficient information for us to complete our analysis. In the absence of this information, we reviewed FSA documentation describing, at a high-level, the release schedule for FPS. This included planned features to deploy from February 2025 through August 2025. We also reviewed information about future functionality releases on FSA’s website.

To address our second objective, we reviewed Education’s standards and guidelines for the monitoring of contracts by program officials.[5] We also assessed the contract for developing FPS (hereinafter referred to as the FPS contract) and its associated documentation, such as the Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan and Performance Work Statement. We then compared actions taken by the agency to monitor the contractor against Education’s established standards and guidelines and contract requirements. To do this, we analyzed customer feedback, contractor-provided reports on performance, and meeting minutes between FSA and its FPS contractor.

To address the third objective, we identified key oversight and program management personnel for the FPS project: the Contracting Officer, Contracting Officer’s Representative, Project Manager, Product Manager, and Systems Integrator. We did so by reviewing project management documentation, such as the contract and documentation identifying key roles and responsibilities for the project. We then reviewed federal regulations and guidance that identified certification and training requirements for acquisition-related work in civilian agencies.[6] We also reviewed information from the Federal Acquisition Institute to identify other relevant federal workforce qualification requirements, such as the Digital IT Acquisition Program.[7]

Further, we reviewed Education and FSA guidance to identify certification requirements for the key personnel. For example, we reviewed Education’s guidance describing standards and guidelines for the monitoring of contracts by program officials.[8] We compared the requirements and guidance to available certification and training documentation for the key FSA personnel.

To address our fourth objective, we assessed FSA’s test management standards and associated testing documentation to determine if they were consistent with leading system development practices from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.[9] These practices describe, among other things, key elements to include in system test cases. We focused our review on seven practices that are considered baseline requirements. To conduct the assessment, we compared the test cases for FPS to the seven leading practices.

We supplemented our analysis for each objective with interviews of relevant FSA and contractor officials, such as those responsible for Award Eligibility Determination project management, FPS contract oversight, system testing, and system integration.[10] These interviews allowed us to corroborate evidence and provide additional context to the actions taken by the agency and its contractor prior to and after implementation of FPS. A more detailed description of our objectives, scope, and methodology can be found in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

To be considered for federal student aid, a student must apply and complete a FAFSA form by paper or electronically on FSA’s website. FPS is the system that underpins federal student aid and processes the applications.

The FAFSA form currently collects personally identifiable information and financial information about the student, and the student’s spouse and parent(s) (if applicable).[11] The agency uses the information to determine aid eligibility for award.

Although the primary purpose of the FAFSA is to help distribute federal student aid, the application also assists state and institutional aid programs who rely on the data to calculate their own aid offers. Specifically, after Education processes a FAFSA form via FPS, a report is sent to the applicant or made available for online viewing. This report includes the applicant’s Student Aid Index, the types of federal aid for which they qualify, and information about any errors (e.g., questions the applicant did not complete) that Education identified when processing the FAFSA.[12]

The applicant’s selected colleges are also sent reports from Education with the Student Aid Index and from state financial aid offices with aid eligibility. Colleges then use this information to send applicants financial aid offers after admission, providing students with types and amounts of federal, state, and institutional aid they are eligible to receive, should the student decide to enroll. Figure 1 provides an overview of the financial assistance process.

aThe Student Aid Index is a formula-based number that helps to determine how much financial support a student may need.

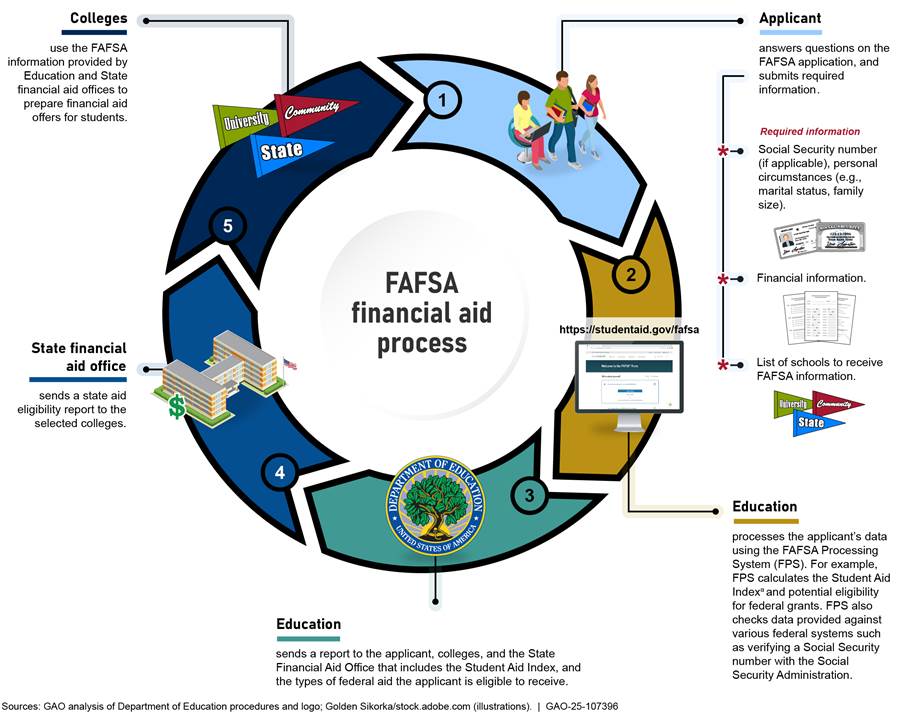

After the student submits the FAFSA form, FPS stores and uses the information collected from the form (e.g., student’s name, address, Social Security number, and financial information) to determine whether the student is eligible to receive federal student aid. FPS also performs checks against data maintained in other systems, including FSA’s National Student Loan Database System and those maintained by other federal agencies, including the Departments of Homeland Security, Justice, and Veterans Affairs; and the Social Security Administration. Figure 2 depicts the process for determining student financial aid eligibility.

Figure 2: The Role of the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Processing System in Determining Student Aid Eligibility

aThe Student Aid Index is a formula-based number that helps schools determine how much financial support a student may need. The Institutional Student Information Record (ISIR) and the FAFSA Submission Summary show the information the student originally provided, the Student Aid Index, results of the eligibility matches, information about aid history, and information about any inconsistencies identified.

FSA Awarded Contracts to Modernize Its Student Aid System and Assigned Staff Key Oversight Responsibilities

In February 2021, FSA initiated a multi-project program called the Student Aid Borrower Eligibility Reform initiative. Among other things, this program is intended to modernize the student financial aid process and its legacy system—the Central Processing System.[13] According to FSA, the following components make up this initiative:

· FPS, which is the back-end processing of the FAFSA. This system is where aid eligibility is determined, and records are generated for colleges and state financial aid offices.

· Digital Customer Care, which is the front-end (or website) for the FAFSA. This is the user interface and contains the form that students and parents fill out for student aid.

· Federal Tax Information Module, which provides (1) a centralized interface used to access tax data from the Internal Revenue Service, (2) a storage of federal tax information, and (3) capabilities to calculate the Student Aid Index and eligibility determination checks, among other things.

There is also underlying infrastructure that supports the overall FAFSA system and an identity and access management system.

Each of these components were to be developed or provided by four separate contractors.[14] This review focused on the contract related to FPS, which was awarded in March 2022.

This contract was originally valued (if all options were exercised) at approximately $121.7 million. The contract was for an initial base period from March 2022 through September 2023, which included the design, development, testing, and deployment of a fully functional FPS. Nine additional 1-year option periods for operating and maintaining FPS were also included in the contract.

The contract type for most contract line items—including those pertaining to system design, development, testing, and deployment—was firm fixed price.[15] Such a structure generally provides for a price that is not subject to any adjustment based on the contractor’s actual costs incurred in performing the contract. The contract also included performance standards, or metrics, that the contractor was to meet. These standards are then to be used by FSA to evaluate the contractor’s performance.

In April 2023, FSA modified the FPS contract to extend the base period’s end date from September 2023 to December 2023.[16] In September 2024, the agency further modified the contract to exercise option period 2 and increased the base and all options value of the contract.[17] As of May 2025, the estimate of the total cost of the contract (if all options are exercised) is approximately $236.8 million. Similar to the initial contract, the September 2024 contract modification had most contract line items as firm fixed prices and included performance standards.[18]

As of May 2025, FSA had obligated approximately $100.3 million for the contract. Table 1 shows the various periods of performance and their actual or estimated costs.

Table 1: Free Application for Federal Student Aid Processing System Contract Costs and Cost Estimates for Base Contract and Option Periods as of May 2025

|

Option period |

Periods of performance |

Actual costs and cost estimates |

|

Base Period |

March 31, 2022 – December 29, 2023 |

$20,895,418* |

|

Option Period 1 |

December 30, 2023 – September 29, 2024 |

$13,917,144* |

|

Option Period 2a |

September 30, 2024 – September 29, 2025 |

$72,520,047 |

|

Option Periods |

September 30, 2025 – September 29, 2032 |

$129,562,702 |

|

Estimated total if all options are exercised |

$236,895,311 |

|

Legend: *=actual costs funded by the Office of Federal Student Aid

Source: GAO (analysis). Office of Federal Student Aid (data). | GAO‑25‑107396

aAt the time of this report, the information

for Option Period 2 only included September 2024 through May 2025. Therefore,

this information includes a mix of actual costs and estimated costs for this

option period.

Several acquisitions and project management staff, such as the Contracting Officer, Contracting Officer’s Representative, Project Manager, Product Manager, and Systems Integrator were assigned various execution and oversight responsibilities throughout the duration of the contract. For example, according to the FPS contract and other relevant documentation:

· the Contracting Officer is the exclusive agent of the government with authority to enter into and administer contracts. The Contracting Officer is responsible for, among other things, monitoring contract compliance, contract administration, and cost control. As part of their responsibilities, the Contracting Officer is to designate one full-time Contracting Officer’s Representative as the government authority for performance management.

· the Contracting Officer’s Representative is to communicate with the contractor as necessary to ensure they are making satisfactory progress in performance of the contract. The representative is responsible for technical administration of the project and is to ensure proper government surveillance of the contractor’s performance. This includes inspection and testing of deliverables and evaluation of reports in accordance with the contract terms. The representative is also to communicate serious concerns or issues to the contractor. However, the Contracting Officer’s Representative is not empowered to make contractual commitments or authorize any contractual changes on the government’s behalf.

· the Project Manager works with the Contracting Officer’s Representative to ensure proper government surveillance of the contractor’s performance. They are to do this by monitoring and providing feedback on the contractor’s performance and reviewing deliverables to ensure that they meet quality standards.

· the Product Manager and Systems Integrator, among other things, manage and prioritize the product’s scope and backlog. Additionally, they collaborate with the contractor to define product increment commitments for each sprint.[19] According to agency officials, the Systems Integrator’s daily tasks, among other things, include aligning and coordinating with FAFSA’s main vendors, various other relevant FSA systems, and external federal agencies.

FSA Encountered Significant Delays and Development Issues with FPS

After awarding the contract for FPS development in March 2022, FSA encountered development issues (e.g., complex scope and lack of expertise). This led to two separate decisions to delay key FPS functionality. Specifically:

· In August 2022, FSA began the process of re-baselining the FPS schedule to move the delivery of a fully functional system from October 2023 to December 2023.[20] Agency officials stated that the final decision for this schedule change was made in early 2023 after briefing leadership from the department and the Executive Office of the President. On March 21, 2023, FSA posted an announcement to its website notifying the public about this decision.[21]

Officials explained that several factors contributed to this decision, including the complexity of scope to implement both the Fostering Undergraduate Talent by Unlocking Resources for Education (FUTURE) Act and FAFSA Simplification Act, while modernizing a process that had not been significantly altered in 40 years.[22] These officials also noted that system development delays had cascading effects on other schedule dependencies and there was a lack of available experts to focus on the implementation.[23]

· In November 2023, FSA decided that it would deploy a limited amount of FPS functionality in December 2023. The agency prioritized functionality that would allow financial aid applicants to submit an electronic FAFSA form but deferred other functionality, such as determining a student’s financial aid eligibility, until a later date. This delay occurred because, according to officials, development of the remaining functionality was behind schedule and the contractor needed additional time to finish development and testing.

As previously discussed, FSA deployed the 2024-2025 FAFSA form in December 2023, which resulted in significant user-reported issues.[24] According to officials, in late March and early April 2024, processing and data errors were identified that affected approximately 30 percent of FAFSA forms. As a result, students and colleges lacked the information they needed to make important financial decisions about the upcoming school year.

FSA described the key challenges it encountered with the initial launch of the FAFSA form in December 2023. Specifically:

· The development teams for the Digital Customer Care, or front-end system, and FPS had to rely on each other and collaborate closely throughout the development process. This was a challenge because the contractors developing these systems were different. Adding to this challenge was the need to integrate these systems with the Federal Tax Information Module and the identity and access management systems, also managed by another contractor.

· FSA lacked internal engineering expertise when it launched the FAFSA form in December 2023. FSA stated it brought in a team of technical leaders in the summer of 2024 and began hiring engineers and technical project managers in the fall of 2024.

· Each contractor created their own development environment and utilized their own tools that did not integrate with each other. This created issues that FSA stated it is still trying to mitigate.

Compounding these issues, according to FSA, was the timeline pressure to develop each component of the system all at once and launch them to the public in a single release. In addition, FSA stated that it had no additional time in the schedule to remediate any issues.

Education Reduced Its Workforce by Nearly Half in 2025

On March 11, 2025, Education announced that it was initiating a reduction in force that would impact nearly 50 percent of its workforce—approximately 2,000 employees.[25] According to the Secretary of Education, the reduction in force reflected the department’s commitment to efficiency, accountability, and ensuring that resources are directed where they matter most—students, parents, and teachers.

According to the announcement, the department stated it intended to continue to deliver on all statutory programs that fall under its purview. However, the announcement also stated that all divisions within the department would be impacted by the reduction, including FSA.

In May 2025, FSA officials stated that the agency had lost nearly half of its certified Contracting Officer’s Representatives during the first quarter of the calendar year. The officials added that they were working to identify and train new Contracting Officer’s Representatives, as well as acquire new resources to support FPS. Therefore, it is unclear if and how the reductions in staff will affect the agency’s ability to carry out its mission to manage and oversee student financial assistance programs, such as FAFSA.

GAO and Education’s Office of Inspector General Have Previously Reported and Have Plans to Report on FSA Challenges

We and Education’s Office of Inspector General have issued reports highlighting various challenges in the department’s management of FPS and other IT modernization efforts. For example:

· In June 2023, we reported that FPS had critical gaps in its process to manage the project’s cost and schedule.[26] We recommended that Education (1) ensure that a life cycle cost estimate is developed for the project and that the budget is updated based on this estimate, and (2) ensure that the project’s schedule includes assumptions and constraints. The department agreed with the recommendations; however, as of August 2025 neither of them had been implemented. According to FSA officials, they had planned to fully address these recommendations by July 2025. At the time of this report, we were still working with Education to determine whether it has taken action to address the recommendations.

· In September 2024, we reported that FSA established agency guidance on how to define and manage IT requirements and carry out testing activities.[27] However, it did not always follow this guidance because, according to FSA, it was designed for projects that release all functionality at one time—not across several releases, like FPS. In addition, the agency did not establish or implement guidance to carry out independent verification and validation reviews for FPS.[28] Compounding these issues, the department lacked consistent leadership in its Chief Information Officer role. We made six recommendations to Education, including adhering to agency policy in managing requirements and testing, developing policy for independent acquisition reviews, and hiring a permanent departmental Chief Information Officer. The department neither agreed nor disagreed with our recommendations. As of August 2025, Education had implemented one recommendation and had not yet implemented the remaining five. At the time of this report, we were still working with Education to determine whether they had taken further action to address the remaining recommendations.

· We also reported in September 2024 that the launch of FPS, which was delayed by 3 months, was hampered by a series of technical problems that blocked some students from completing the FAFSA application.[29] For example, students with parents or spouses that did not have a Social Security number encountered significant barriers to accessing and completing the FAFSA application form. In addition to system issues, nearly three quarters of all calls (4.0 million out of 5.4 million calls) to the call center—the main resource for applicant assistance—went unanswered during the first 5 months of the rollout. We made seven recommendations to Education, including that the department overhaul the submission process for parents and spouses without Social Security numbers and ensure sufficient call center staffing. Education neither agreed nor disagreed with our recommendations. As of August 2025, one of the recommendations had been implemented.

· In June 2024, Education’s Office of Inspector General reported on weaknesses in the way FSA adhered to its Lifecycle Management Methodology, its IT project delivery, and governance methodology for its Business Process Operations project.[30] For example, the Office of Inspector General attempted to review test summary reports to confirm that the project’s various systems had been successfully tested and what defects, if any, had been identified. However, FSA was unable to provide 22 of the 32 required reports (69 percent). The Office of Inspector General made several recommendations to FSA to improve testing practices, among others.

In April 2025, Education’s Office of Inspector General initiated a series of reviews to provide information on the impact to the department’s programs and operations following the reductions in the workforce. According to officials in the office, the work is currently ongoing. In addition, in April 2025, we began work on the impact of the reductions in force on the capacity of the agency to carry out its statutory functions. As of August 2025, this work was ongoing.

FSA Was Unable to Report the Current Status of FPS or Causes for Delays

In September 2024, we reported that, according to FSA, the status of FPS was incomplete. Specifically, nine of the 25 contractual requirements that define FPS’s capabilities had not yet been deployed as of August 2024.[31] Examples of the nine requirements not yet deployed included allowing FSA to (1) make corrections to FAFSA applications and (2) modify eligibility rules and requirements. Officials stated in September 2024 that these remaining requirements would be deployed across several releases starting in the fall of 2024 and ending in calendar year 2026.

As of May 2025, the agency was unable to provide the status of the remaining nine requirements for delivering the complete FPS system or the causes for any delays in completing them. In lieu of this, FSA provided high-level documentation describing the release schedule for the system, including planned features to deploy through May 2025. In addition, in June 2025, FSA stated that in the coming months, it would release the following functionality connected to the FAFSA:

· An overhaul of how contributors interact with the form, which FSA stated represents the top complaint of users and number one call driver to the contact center.[32] For example, students completing a 2026-2027 FAFSA form will be able to invite a parent or spouse as a contributor simply by entering their email, instead of asking students for a contributor’s personally identifiable information. FSA stated that this functionality would be deployed in August 2025.[33]

· Real-time matching with the Social Security Administration to confirm a user’s identity. This will allow students to complete the form in a single sitting versus having to wait 1 to 3 days to have their identity verified. According to FSA, this will also allow for the immediate ingestion of tax information from the Internal Revenue Service. FSA stated that this functionality would be deployed in August 2025.[34]

· Real-time processing for a vast majority of students, providing students with an immediate understanding of their eligibility for aid. FSA did not provide a specific time frame for the release of this functionality.

At the time of this report, we were unable to determine whether this functionality would be included in the 2026-2027 FAFSA form.

The information FSA provided did not make clear how the planned releases aligned with the outstanding contract requirements nor did it outline detailed plans for future releases. FSA officials stated that they could not easily provide information on the status of the nine outstanding contractual requirements because they were not tracking the delivery of FPS in terms of the contractual requirements. Instead, officials stated that FSA prioritized features based on the value that they add to users and their alignment to its core goals and metrics. Officials added that they release software throughout the year and are moving away from an outdated model of planning years in advance for single annual releases.

Education’s guidance states that every contract should be monitored to the extent appropriate to provide assurance that the contractor performs the work called for in the contract and develops a clear record of accountability for performance. Without tracking the status of FPS functionality in terms of the initial contractual requirements, the agency significantly increases the risk that it will not be able to ensure that the functionality called for in the contract is provided.

FSA Established Two Contract Oversight Approaches but Did Not Fully Implement Them

FSA established two different approaches to monitoring its contractor’s performance for FPS. However, the agency did not fully implement either approach because it had not: (1) established all performance metrics prior to September 2024, (2) received data for all of the established performance metrics prior to November 2024, (3) validated contractor performance data, and (4) documented the actions it took to oversee contractor performance.

FSA Established Two Approaches to Contractor Oversight Throughout the Life of the Contract

Federal regulations generally require that government officials use performance-based acquisitions for services to the maximum extent practicable and then use measurable performance standards to oversee such contracts and perform government contract quality assurance.[35] To that end, FSA established two different performance-based approaches to oversee the FPS contract. One was established with the initial contract in March 2022. The other, a modified process, was established with a change to the contract in September 2024.

FSA’s Initial Contract Oversight Process

FSA’s initial process to oversee the contractor’s performance was documented as part of the original March 2022 contract in a Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan (QASP). This oversight process included performance metrics, surveillance methods, and customer feedback.

· Performance metrics. FSA’s initial oversight process identified performance metrics, known as service level agreements (SLA), that were to be used to ensure the contractor was meeting the desired program outcomes. The FPS contract defined 28 SLAs across six categories: (1) system performance, (2) system testing, (3) system security, (4) Electronic Questionnaires for Investigations Processing, (5) contractor employee clearance monitoring, and (6) Student Aid Information Gateway Tier II help desk.[36]

Each SLA had an established performance target that the agency expected the contractor to achieve. Sixteen of the 28 SLAs included disincentive parameters for not meeting the expected service level targets. These SLAs were represented in each of the six categories the contract defined.

According to the QASP, FSA was to receive information on the compliance of performance metrics via reports from its contractor. The QASP notes that these reports could be produced in various forms, such as monthly and weekly contractor-provided progress reports, internal trackers for contract issues, and project boards.

In addition to SLAs, the agency was to work with its contractor to develop additional performance metrics—key performance indicators (KPI) and sprint metrics.[37] These metrics were to be developed after contract award and used by agency officials to monitor contractor performance.

· Surveillance methods. According to the QASP, performance metrics were to be assessed using performance monitoring techniques and tools. The QASP defined three surveillance methods that could be applied to surveil and validate contractor performance:

· 100 percent inspection where each month the agency would perform a complete review of performance reports and document the compliance results for contract requirements;

· periodic inspection where an inspection would be performed periodically to evaluate some part, but not all, of the contractor’s level of performance of a product or service being monitored; and

· random sampling where statistical methods may be used to estimate the overall level of performance of some, but not all, of a specific contract requirement based on a representative sample drawn from a population.

The QASP also defined a suite of surveillance tools that contract oversight officials were to use to assess contractor performance reports. For example, these included the FSA Operations Tool that was intended to provide the agency with access to available real-time and historic operational data. The tool was to show system health, performance metrics, and enable operational functions.

According to the QASP, FSA was to record the results of its surveillance activities each month in a written report to include the contractor’s submitted reports and other supporting evidence. The surveillance report was intended to demonstrate whether the contractor was meeting the stated objectives and performance standards.

· Customer feedback. The QASP established customer feedback as another method to assess contractor performance based on communication between the contractor and its customer—FSA.[38] According to the plan, the objective of this communication is customer satisfaction, which the QASP described as an indicator of the success and effectiveness of all services provided. The plan further notes that customer feedback can be provided in a variety of ways, including formal surveys, written complaints, and weekly and monthly progress meetings, among others.

FSA Revised Its Contractor Oversight Approach in Late 2024

FSA officials reported that they experienced challenges in implementing their initial oversight plans due to the staggered release schedule of the 2024-2025 FAFSA form. In addition, officials stated that elements of their initial oversight plan were inappropriately designed and implemented. For example, officials stated that their established performance measures targeted a system that was operational versus a system that was still in development.

To improve FSA’s ability to monitor its contractor’s performance in developing and operating the FPS system, the agency worked with its contractor and the U.S. Digital Service to establish, among other things, a new process for overseeing contractor performance.[39] This new contract oversight process was established with a contract modification in September 2024.

FSA’s new approach to contract oversight focused primarily on performance metrics and surveillance methods and removed the previous requirement for customer feedback. In addition, the new process replaced the general surveillance methods with specific methods that are to be used to verify performance data for each identified metric.

FSA’s newly established oversight process identified 13 performance metrics across seven categories: (1) planning, (2) requirements, (3) design, (4) development, (5) testing, (6) security, and (7) release. For each of these metrics, FSA defined the acceptable quality level and surveillance method to be used to determine whether the metric had been met. These methods of surveillance included manual reviews, automated checks, meetings, and documentation reviews.

In addition to the performance metrics, the new oversight approach also included 28 SLAs across nine categories: (1) system performance; (2) testing; (3) security; (4) FPS help desk; (5) annual development; (6) interfacing with other FSA systems; (7) stakeholder communications; (8) customer experience; and (9) production, operations, and maintenance.

Each SLA has an established performance target, and three of the 28 SLAs included financial disincentive parameters for not meeting the expected service level targets:

· system availability under the system performance category,

· incident notification timeliness under the system performance category, and

· employee departure notifications under the security category.

As with the previous oversight process, FSA was to receive information on the compliance with performance metrics through various reports from its contractor. For example, most SLAs are reported to FSA via a monthly progress report deliverable. Other performance metrics, such as sprint planning metrics, as defined by the QASP, are to be reported by the contractor through weekly progress reports and biweekly end-of-sprint reports.[40]

FSA Has Not Fully Implemented Its Approaches to Overseeing the Contractor’s Performance

Education policy requires that every contract be monitored to provide assurance that the contractor performs the work called for in the contract and to develop a clear record of accountability for performance. To do this, government contract oversight officials are to

· validate monitoring efforts by obtaining supporting evidence to determine the reliability of contractor reports, and

· document officials’ evaluation of contractor performance reports.

As previously mentioned, FSA’s two oversight processes included performance metrics, surveillance methods, and customer feedback.[41] Although the agency modified its approach to improve contract oversight, it has continued to struggle with overseeing FPS system implementation. In particular, the agency has not fully implemented either its previous or current oversight approach (see table 2).

Table 2: Office of Federal Student Aid Implementation of Contractor Oversight Approaches for the Free Application for Federal Student Aid Processing System

|

Oversight practice |

Implemented by initial oversight approach? |

Implemented by revised oversight approach? |

|

Provide customer feedback |

● |

Not applicablea |

|

Establish performance metrics |

◐ |

● |

|

Receive status information for performance metrics |

◐ |

● |

|

Surveil contractor performance |

○ |

○ |

|

Document oversight |

○ |

○ |

Legend: ●=Generally addressed. ◑=Partially addressed. ○=Not addressed.

Source: GAO analysis of Office of Federal Student Aid information. | GAO‑25‑107396

aIn the revised contract oversight plan established by the September 2024 contract modification, customer feedback was removed as a method to monitor contractor performance.

FSA Conducted Customer Feedback in Its Initial Oversight Plan but Removed It from Its Revised Plan

According to its initial oversight plan, FSA was to assess contractor performance based on communication between the contractor and the agency by providing customer feedback through formal surveys, written complaints, and weekly and monthly progress meetings, among other methods. To that end, FSA officials provided detailed, written feedback to its FPS contractor so it could adjust how it was providing services as needed.

For example, from June 2022 to January 2024, FSA sent at least three letters to the contractor and expressed concerns with the way they were providing services to the agency. These concerns related to:

· the contractor’s implementation of the Agile process and requirements development practices,[42]

· the scope of the work required for the Award Eligibility Determination project,

· Agile coaching,

· government team integration into product planning, and

· the contract-required tools for supporting and managing FPS.

In response to these concerns, the contractor identified the remediation actions it took or planned to take.

In addition to the formal written complaints, FSA conducted surveys of its staff in December 2022 and June 2023 regarding their satisfaction with contractor performance. The survey covered an overall satisfaction rating, as well as results related to timeliness, quality, communication, issue management, and staffing. For example, about 54 percent of respondents reported that they were satisfied with the contractor’s performance and 9 percent reported dissatisfaction.[43] However, in June 2023, satisfied responses dropped to 31 percent, while dissatisfied responses rose to 31 percent.[44]

Finally, FSA provided customer feedback through weekly progress meetings and biweekly contract meetings. In these meetings the agency tracked open issues, action items, status of performance metrics, contract discrepancies, as well as corrective actions taken by the contractor. In its September 2024 modification to the FPS contract, FSA did not include customer feedback as part of its revised contract oversight process.

FSA Initially Lacked Certain Performance Metrics but Fully Established Metrics in Its 2024 Contract Modification

As previously discussed, the FPS contract states that KPIs and sprint metrics were to be developed and finalized after contract award to provide additional metrics to measure the contractor’s performance. Once established, these metrics were to be reported via monthly progress reports and sprint reports by the contractor to the agency.

However, under FSA’s initial oversight approach, the KPIs and sprint metrics were not finalized as planned. Officials stated that they deprioritized finalizing these metrics and, instead, focused on developing and delivering FPS functionality.

With the 2024 contract modification, FSA moved away from establishing KPIs and sprint metrics, as defined in their initial oversight process, and established new QASP performance metrics and revised the SLAs as previously discussed. By establishing and finalizing these metrics, FSA is better positioned to make data-driven decisions, reduce costs, and improve project outcomes.

FSA Initially Lacked Status Information for All Performance Metrics Until It Modified Its Approach

FSA was not initially receiving status information from the contractor for most of the established performance metrics, hindering its ability to monitor them. Specifically, from June 2023 to March 2024,[45] FSA received status information from the contractor for nine of the 28 defined SLAs (approximately 32 percent) through monthly progress reports.[46]

FSA officials stated that certain SLAs were not monitored because they were focused on delivering functionality supporting the 2024-2025 FAFSA form. The officials added that they also had not yet established a process to receive information about all SLAs. Officials further stated that they had planned to use the FSA Operations Tool to monitor the contractor’s work, but it was not yet available. Agency officials stated that without the tool they were hindered in their ability to monitor the SLAs as planned.

Under its revised oversight approach, established in September 2024, FSA was to receive information on the newly established performance metrics via reports from its contractor. In November 2024, the contractor began reporting on all the applicable QASP performance metrics and SLAs.[47] Specifically, the reports identified which metrics the contractor was able or not able to successfully achieve, an explanation of why a metric was not achieved, and a description of any applicable waivers for not meeting a metric. For example, the contractor could not meet two SLAs related to the FPS help desk in the months of November and December 2024 and January 2025 because of high call volumes. The contractor stated in these reports that it was working to increase staffing, but that the staffing candidates were waiting for preliminary clearance from FSA to begin work.

By receiving status information on all established performance metrics, FSA is better positioned to make informed decisions on how well the system is performing and how effective its contractor is at meeting the needs of the agency.

FSA Did Not Validate Performance Data Using Surveillance Methods

As previously discussed, Education contract monitoring guidance requires contract oversight officials to validate monitoring efforts by obtaining supporting evidence to determine the reliability of contractor reports. However, FSA did not validate contractor performance data through established surveillance techniques in either of its oversight approaches.

According to agency officials, validating contractor-provided performance data has been a challenge because the agency does not have a way to do so independently. Specifically, during the initial process, FSA officials stated that they had planned to develop a method to independently validate data using the assistance of a support contractor. However, these efforts were not finalized by the time the support contract was terminated.

Under its revised oversight approach, FSA continues to lack a process to validate contractor performance data. According to officials, they are assessing whether to continue with plans to develop the FSA Operations Tool, as described by the contract, or some other alternative. FSA officials estimated that the tool or another alternative could be available by the end of 2025 or in 2026. According to the same officials, there are higher-priority items to be addressed first, such as the ability for school Financial Aid Administrators to track verification of student identities and finances.

Without surveilling and validating contractor performance, FSA continues to be limited in its ability to provide assurance that the contractor performs the work called for in the contract. In addition, the agency is unable to develop a clear record of accountability for performance.

FSA Did Not Document Its Oversight of Contractor Performance

In addition to validating the reliability of contractor reports, Education guidance requires contract oversight officials to document their oversight activities. Specifically, the guidance requires a written evaluation of contractor performance reports provided to the agency.

However, FSA did not document the actions it took to evaluate reports from the contractor on progress towards meeting performance metrics in either of its oversight processes. During the initial process, according to agency officials, performance reports were reviewed, but no formal process to document the outcomes of the review existed. Instead of documenting their review, officials stated that they held meetings with the contractor to convey any feedback on performance. FSA officials also noted that the lack of documentation was due, in part, to the fact that they were under resourced given the size of the contract.

Under its revised oversight approach, FSA continues to lack a process to document the actions it is taking to evaluate reports from the contractor on progress towards meeting performance metrics. Officials stated that they continue to rely on meetings with the contractor to convey any feedback on performance. However, without documenting the actions taken to evaluate contractor performance, FSA has limited assurance that proper steps are taken to ensure that contractor performance for FPS meets established standards. Further, the agency lacks a clear record of accountability for contractor performance, per Education’s policy.

FSA Could Not Always Demonstrate That Key Oversight Staff Had Necessary Qualifications

FSA could not always demonstrate that key officials responsible for overseeing FPS had the proper qualifications to perform their job duties. In addition, the agency could not show that these key officials took specialized training related to the Agile system development methodology that was selected for developing FPS in a timely manner.

Key Contracting Officials Did Not Always Have Necessary Certifications

Federal regulations and Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance requires that key staff obtain and maintain federal certifications for acquisition- and project management-related work in civilian agencies.[48] To that end, OMB and the General Services Administration created Federal Acquisition Certification (FAC) programs to establish consistent competencies and standards for those performing acquisition-related work in civilian agencies:

· FAC in Contracting (FAC-C) (Professional). According to OMB guidance, acquisition workforce members performing the role and responsibilities of a Contracting Officer are required to obtain this certification.[49] The FAC-C (Professional) is a single-level certification with specific experience and training requirements.

· FAC for Contracting Officer’s Representatives (FAC-COR). This is a three-level certification with different training and experience requirements based on the level for which an individual is certified. For example, a level three FAC-COR will have higher training and experience requirements in comparison to a level two FAC-COR.

· FAC for Program and Project Managers (FAC-P/PM). According to General Services Administration guidance, this certification is meant for acquisition professionals performing program and project management activities and functions. This could include roles such as the Project Manager, Product Manager, and Systems Integrator.[50] This is a three-level certification where requirements increase as the level increases. The FAC-P/PM certification also has specialization options, such as its FAC-P/PM with IT specialization for program and project managers supporting IT acquisitions.[51]

According to OMB policy, to maintain each certification, individuals must meet specific continuous learning requirements over a 2-year period. These requirements can be met through a variety of acquisition-related learning activities, including training.

However, FSA was not able to demonstrate that all the key contracting officials for FPS met these requirements while they were assigned to the project. Table 3 provides details on the extent to which FSA showed that these officials possessed or maintained required certifications.

Table 3: Extent to Which Key Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Processing System (FPS) Contracting and Program Officials Obtained and Maintained Certifications

|

Contracting official |

Required certification |

GAO rating |

GAO assessment |

|

Contracting Officer |

Federal Acquisition Certification (FAC) in Contracting (Professional) · Both Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Department of Education guidance require Contracting Officers to obtain the certification before being appointed to any contract. · Education guidance requires Contracting Officers to maintain the certification while appointed to any contract. OMB guidance requires certification holders to meet continuous learning requirements. |

● |

Since the award of the FPS contract in March 2022, the Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA) has assigned one Contracting Officer to the FPS contract. · FSA demonstrated that the Contracting Officer for FPS obtained the certification in September 2008, which was prior to the award of the FPS contract. · According to training records provided by FSA, the Contracting Officer met the continuous learning requirements to maintain this certification through the time of our review in May 2025.a |

|

Contracting Officer’s Representative |

FAC for Contracting Officer’s Representatives · Federal regulations and Education guidance require Contracting Officer’s Representatives to obtain the certification before being appointed to any contract. · Education guidance requires that Contracting Officer’s Representatives appointed to complex, high-risk contracts, such as FPS, obtain a level three certification. · Federal regulations and Education guidance require Contracting Officer’s Representatives to maintain the certification while appointed to any contract. OMB guidance requires certification holders to meet continuous learning requirements. |

◕ |

Since the award of the FPS contract in March 2022, FSA has assigned three Contracting Officer’s Representatives.b One was assigned in March 2022, another in October 2024, and the third in April 2025. · FSA demonstrated that all three representatives obtained their certifications prior to being assigned to the contract. · The representative appointed at contract award (March 2022) until March 2025 obtained a level two and not a level three certification as required by Education.c The other two representatives obtained a level three certification. · According to training records provided by FSA, all three Contracting Officer’s Representatives met the continuous learning requirements to maintain their certifications throughout the remainder of their assignment, or by the time of our review in May 2025.a |

|

Project Manager and other project management staff |

FAC for Program and Project Managers · OMB and Education guidance require Project Managers for major IT acquisitions, such as FPS, to obtain a level three certification with the IT specialization. · Education guidance requires Project Managers to maintain the certification while leading any project. OMB guidance requires certification holders to meet specific continuous learning requirements. · According to General Services Administration guidance, this certification is also for acquisition professionals in the federal government performing program and project management activities and functions. This could include other key staff, such as the Product Managers and Systems Integrators. |

◔ |

Since the award of the FPS contract in March 2022, FSA has assigned two FPS Project Managers in March 2022 and March 2025, two Product Managers in March 2022 and August 2022, and a Systems Integrator in June 2022. · Both FPS Project Managers obtained their level three certifications with IT specialization prior to being assigned to the contract, in March 2017 and January 2024 respectively. · According to training records provided by FSA, the Project Managers respectively met the continuous learning requirements to maintain their certifications throughout their assignment to the contract or by the time of our review in May 2025.a · The FPS Product Managers and the Systems Integrator had not obtained this certification.d |

○ = Requirement not met, ◔ = Requirement mostly not met, ◑ = Requirement partially met, ◕ = Requirement mostly met, ● = Requirement fully met

Source: GAO analysis of FSA information. | GAO‑25‑107396

aFSA officials stated that they can only view records from the current continuous learning period and one period prior, which at the time of our review was from May 1, 2022 through April 30, 2024. FSA provided documentation showing that the Contracting Officer, one of the Contracting Officer’s Representatives, and one of the Project Managers maintained their certification during the prior continuous learning period. Although this does not cover the beginning of these officials’ assignment periods, March 31, 2022, we considered this short period of time inconsequential.

bAccording to FSA documentation, the agency assigned the first Contracting Officer’s Representative to the FPS contract at award in March 2022. This individual served in that role until they left the agency in March 2025. In October 2024, FSA assigned a second Contracting Officer’s Representative to serve until around March 2025. In April 2025, FSA assigned a third representative who will remain on the contract through termination, according to FSA officials.

cAccording to FSA, this Contracting Officer’s Representative completed all necessary training for the level three FAC for Contracting Officer’s Representatives but did not submit the request to receive the level three certification.

dAccording to FSA, the Systems Integrator completed all necessary training for the FAC for Program and Project Managers but did not submit the request to receive the certification.

Several FSA key oversight officials did not obtain the necessary certifications for various reasons. FSA officials stated that the Contracting Officer’s Representative had not obtained the required level three certification because, although the representative completed the necessary training, they did not submit the request to receive the level three certification. In addition, FSA officials stated that the Product Manager was unable to attend the training required for the project management certification and that the Systems Integrator completed all necessary training for the certification but did not submit the request to receive it.

According to FSA, workload and budgetary constraints were contributing factors to the lack of certifications. Officials added that they are taking proactive steps to address the certification needs related to the FPS effort, while adjusting to the recent loss of significant resources. Until FSA ensures that key contracting and program officials obtain and maintain required certifications, it increases the risk that the officials will lack the necessary qualifications to effectively oversee major acquisitions, such as FPS.

Key Acquisition Staff Lacked Specialized Training in Agile Systems Development Practices

OMB and the U.S. Digital Service collaborated to develop the Digital IT Acquisition Program (DITAP) to provide timely, relevant, and continuous training for acquisition professionals procuring digital services.[52] OMB guidance requires or encourages specific acquisition professionals to attend DITAP training if they are assigned to large acquisitions consisting primarily of digital services, such as FPS.[53]

DITAP includes training on the Agile development methodology and is required by OMB and Education for Contracting Officers. The training is encouraged by OMB for Contracting Officer’s Representatives and other key acquisition personnel performing program and project management activities and functions, such as Project and Product Managers and Systems Integrators.

However, these key acquisition personnel did not attend DITAP training, according to FSA. Agency officials stated that due to budget limitations, the agency has only been able to provide half of its contracting professionals with DITAP training. In addition to budget limitations, officials stated that the Contracting Officer was unable to attend the training because of the departure of multiple staff supporting contract oversight and challenges they experienced with the FPS contract.

FSA staff overseeing the contract reported difficulties in performing their roles because they lacked experience and training with the Agile methodology that was selected for developing FPS. For example, according to agency staff, their lack of experience and training in Agile made it difficult for them to use reported information to effectively monitor FPS’s progress.[54] For example, the contractor provided oversight officials with information, such as sprint velocity and burndown, but the FSA officials were not aware of how to use the information effectively to determine what progress was being made in the FPS effort.[55]

FSA officials stated that the Contracting Officer attended other training related to Agile, but this was 2 years before the FPS contract award. FSA officials also stated that multiple FAFSA team members, including the FPS Product Manager, attended Agile project management training in April 2019, nearly 3 years prior to contract award. The extensive amount of time between the staff attending the training and the need to apply the training to fulfill their job duties for the FPS effort likely contributed to the lack of Agile knowledge.

The contract’s initial performance work statement in the March 2022 contract noted that the FPS program team, which would include staff overseeing the contract, is less familiar with Agile methodologies and would require additional training and support from the contractor. This statement demonstrated that FSA knew that the staff needed to take specialized training but did not ensure it happened.

By not providing its contract oversight staff with the appropriate Agile-based training in a timely manner prior to contract execution, FSA increased its risk that staff would lack the knowledge they needed to effectively monitor the FPS contract. Proper training of staff will become continuously more important with the increase in FSA personnel turnover in 2025.

FSA Did Not Fully Apply Disciplined System Testing Practices for FPS

We have previously reported that FSA’s test plan for FPS development did not align with leading system testing practices. In addition, FSA developed test cases that were to guide its efforts in testing the FPS system prior to launch, but most of them lacked key information. Further, while FSA has improved its testing efforts by engaging users, the agency does not have a plan to guide its future efforts.

FPS Has Not Implemented Prior Recommendation Related to Test Planning

Testing an IT system is essential to validate that the system will satisfy the requirements for its intended use and user needs. Effective testing facilitates early detection and correction of software and system anomalies. It also provides information to key stakeholders for determining the business risk of releasing the product in its current state. Leading industry practices for systems development identified by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) state that entities should document their planned activities for systems testing in a test plan.[56] The leading practices also identify what information should be included in a test plan, such as roles and responsibilities, entry and exit criteria, and deliverables, among other things.

In September 2024, we reported that although FSA had guidance for testing IT systems that aligned with leading practices, the agency had not ensured that its FPS system development contractor developed well-defined test plans.[57] Our report states that although the contractor developed a draft plan for testing major FPS releases, the plan was not finalized before testing began. In addition, according to the report, the plan did not include key details for each of the test events, such as roles and responsibilities, entry and exit criteria, and deliverables. Nevertheless, FSA gave approval for its contractor to perform various testing activities.

The report also highlighted that FSA had conducted several test events for FPS prior to initial deployment in December 2023 consistent with the agency’s guidance, including integration and performance testing. However, the agency lacked system testing with actual end users (e.g., student and parent applicants, and colleges) prior to deploying the system. Further, FSA’s guidance on system testing did not describe how to carry out such testing.

FSA’s Assistant Deputy Chief Operating Officer at the time of the September 2024 report told us that the agency’s guidance for managing projects was designed for projects that deploy all functionality at one time—not across several releases, like FPS. That official added that FSA made every effort to follow its guidance, but that the guidance did not always fit the agency’s approach for implementing FPS.

However, FSA had not developed a plan that tailored its guidance on system testing to fit its current incremental deployment approach. In the September 2024 report, we recommended that Education develop a plan that tailors the agency’s guidance on system testing to fit its current incremental deployment approach and to implement the plan.

As of June 2025, this recommendation had not been addressed. In our prior report, the FSA Assistant Deputy Chief Operating Officer stated that the agency had begun to draft a plan that tailors the agency’s approach for following its guidance and expected to finalize that plan in early fall 2024. However, FSA has not provided an update on the actions it has taken to address the recommendation.

Further, according to officials in January 2025, they do not intend to update the master test plan for future FPS releases to align with leading practices because they want to focus on delivering additional system functionality. However, focusing on delivering functionality without having the tailored guidance or a master test plan increases the risk that the resulting functionality will not fully meet the needs of the agency and its users. Further, until FSA updates its guidance and test plan, the agency unnecessarily increases the risk of problems going undetected until late in the system’s release, such as the issues FSA encountered during the initial launch.

FPS Test Cases Lacked Key Information

Test cases describe scenarios that the system must perform to meet intended requirements. They are used to determine whether an application, system, or a particular system feature is working as intended. Leading practices in systems development identified by IEEE call for each test case to:

· include a unique identifier so that each test case can be distinguished from all other test cases,

· identify and describe the objective,

· define the priority for the testing,

· describe the preconditions of the test environment,

· describe traceability,

· specify the inputs required for execution, and

· specify expected results required of the test items.[58]

IEEE also states that the actual results of the executed test cases should be documented. They should then be compared to the expected results to determine the final test result.

FSA developed test cases for FPS user acceptance and end-to-end testing for the 2024-2025 and 2025-2026 FAFSA cycles. These test cases included some, but not all, of the recommended components. Specifically, for the 2024-2025 FAFSA cycle, most of the test cases specified inputs (242 of the 244) and expected results (241 of the 244). However:

· 232 did not include a unique identifier,

· 86 did not describe an objective,

· 244 did not define testing priorities,

· 238 did not describe preconditions, and

· 244 did not describe traceability.

For the 2025-2026 FAFSA cycle, most of the test cases specified inputs (107 out of 108) and expected results (98 out of 108). However:

· 89 did not include a unique identifier,

· 85 did not describe an objective,

· 108 did not define testing priorities,

· 96 did not describe preconditions, and

· 95 did not describe traceability.

In addition, many of the test cases did not include enough information to determine whether the tests passed, failed, or were executed at all. Specifically, FSA did not document actual results for 186 of the 244 test cases from 2024-2025 and 59 of the 108 test cases from 2025-2026. Therefore, it was unclear whether the tests were ever performed. FSA staff could not explain why the test cases lacked key information.

This occurred, in part, because FSA’s existing test management standards did not include guidance on what information is required when developing test cases. Without such a standard, FSA could likely continue to lack key information needed to ensure that the test cases support system requirements and reflect the system’s ability to perform as intended, regardless of the testing method used.

In June 2025, FSA officials stated that testing at the agency is migrating from traditional manual testing of discrete business functionality to establishing an environment that allows for maximum automated testing. The officials added that this would allow for immediate and comprehensive testing in minimal amounts of time using much fewer resources.

However, the officials did not have a time frame for when this migration to automated testing would take place and did not provide details on how the automated testing would be implemented. Nonetheless, without guidance on how FSA should develop test cases, future testing will likely continue without the information necessary to effectively carry it out.

FSA Improved Testing by Engaging Users and Mitigating Errors but Does Not Have a Plan to Guide Future Efforts

Leading practices developed by IEEE suggest that systems testing should be conducted early and often in the life cycle of a systems development project. This allows for the modification of products in a timely manner, thereby reducing the overall project and schedule impacts. In addition, as previously stated, test plans are key to ensuring that testing is carried out effectively.

One type of system testing—beta testing—allows an entity to release a nearly finished product to a limited group of external users to test and provide feedback before its official launch. This allows developers to identify errors, usability issues, and make improvements based on real-world user experiences before releasing the product to the wider public.

FSA Engaged with Users to Perform Beta Testing for the 2025-2026 FAFSA Award Cycle

In September 2024, we reported that FSA had not tested the FPS system with actual end users (e.g., student and parent applicants, and colleges) prior to deploying the system for the 2024-2025 FAFSA award cycle. FSA officials explained that they did not conduct such testing due to time constraints. As a result, the officials did not have assurance that FPS would meet end user needs.

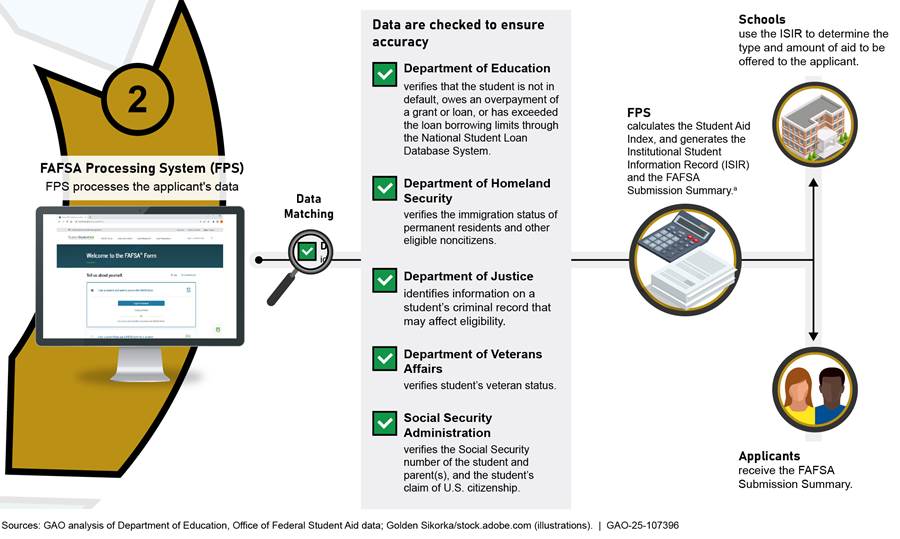

To mitigate this, FSA conducted four rounds of beta testing with a variety of students prior to the launch of the 2025-2026 FAFSA cycle. These tests were intended to help instill trust in its users that the system would work as promised. The agency conducted beta testing from October 1, 2024, through late November 2024 in four phases (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Timeline of Beta Testing Activities for the Free Application for Federal Student Aid Processing System

aFSA opened the form to any interested student or family in an expanded beta four phase.

With each phase, FSA engaged with an increasing number of students and, as a result, more FAFSA forms were submitted by student testers with each phase. Specifically, the agency reported that:

· beta phase one had a total of approximately 680 FAFSA form submissions.

· beta phase two had more than 700 submissions within the first 2 days and there were approximately 1,000 total submissions.

· beta phase three had a total of 10,000 submissions.

· beta phase four had an additional 4,000 submissions.

FSA opened the form to any interested student or family in the expanded beta four phase on November 18, 2024. The agency reported that at the end of its beta testing, there were 122,340 submissions. According to officials, the beta testing effort resulted in the 2025-2026 FAFSA form launching without any known critical defects.[59] Officials added that this was due to their efforts in identifying and resolving defects during testing, which we discuss in more detail later in this report.

Agency officials emphasized that the complexity of different FAFSA user types necessitated beta testing with actual users. In addition to testing the FPS system with users, FSA also wanted to ensure that beta testing included the external support capabilities for the FAFSA form. For example, agency officials stated that FSA wanted to test support operations and call center support for accuracy and timeliness before the 2025-2026 FAFSA form fully launched.

FSA stated that the agency focused on several key requirements when planning for the beta testing effort. Specifically, the agency focused on:

· Creating a substantial scale with a variety of users. According to FSA officials, they wanted beta testing to include a large number of students with a variety of circumstances to ensure that they adequately tested the system. To do this, they engaged with different types of users that would interact with the form in different ways. FSA wanted to avoid only testing with “typical” users. Beta testing with user groups like students who are provisionally independent, have mixed status families, or are incarcerated allowed the agency to test how the form responded to the atypical information these users provided.[60]

To ensure its beta testing included a variety of student types, FSA recruited testers from community-based organizations, high schools (both public and private), school districts, colleges, and universities.[61] According to agency officials, these organizations were important because they are familiar with the FAFSA form, are good at recruiting, and typically have access to specific populations, such as unhoused or incarcerated students. FSA also wanted to include various types of relevant organizations in its beta tests. This included colleges that were customers of major financial aid software vendors that processes student information to test that the system was compatible with their software.

· Performing end-to-end testing. According to FSA officials, they wanted the beta testing effort to not only include the submission of the FAFSA form, but also the system’s functionality beyond that. For example, the agency wanted to ensure that colleges were able to load Institutional Student Information Records (ISIR) into their financial aid software.[62]