PERSISTENT CHEMICALS

DOD Needs to Provide Congress More Information on Costs Associated with Addressing PFAS

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

|

On February 25 2025 GAO reissued this report to include comments from the Department of Defense in Appendix VII. |

View GAO‑25‑107401. For more information, contact Alissa Czyz, 202-512-4300 or CzyzA@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107401, a report to congressional committees

DOD Needs to Provide Congress More Information on Costs Associated with Addressing PFAS

Why GAO Did This Study

DOD has spent $2.6 billion since 2017 addressing PFAS releases. PFAS are a large group of chemicals developed decades ago that can persist in the environment and cause adverse health effects. DOD’s use of certain firefighting agents and other activities, such as metal plating, have led to PFAS releases from DOD installations, potentially exposing service members, their families, and surrounding communities. Investigating and cleaning up PFAS releases is an endeavor that could take DOD decades and billions of dollars to complete.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for GAO to review DOD’s efforts to test and remediate PFAS contamination. This report (1) describes the status of DOD’s efforts, and (2) assesses DOD’s pace, thoroughness, and cost of its efforts, among other things. GAO analyzed DOD’s PFAS-related reports to Congress, reviewed DOD and Environmental Protection Agency guidance and regulations, and interviewed officials.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that DOD provide additional information to Congress on total fiscal exposure related to PFAS investigation and cleanup and a detailed explanation and examples of changing key cost drivers. DOD partially concurred and GAO modified the recommendation based on DOD’s feedback.

What GAO Found

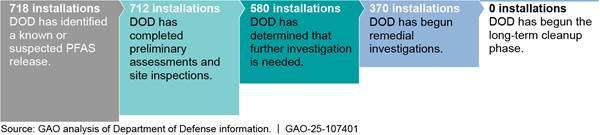

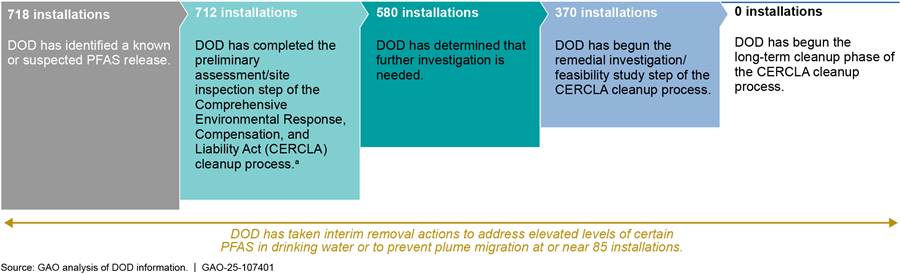

As of June 2024, the Department of Defense (DOD) had completed preliminary assessments and site inspections for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) at nearly all 718 installations identified to have a potential PFAS release and had proceeded to the next step of the cleanup process at more than half. No locations have entered the long-term cleanup phases.

Department of Defense (DOD) Actions Related to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) at Current or Former Military Installations, as of June 2024

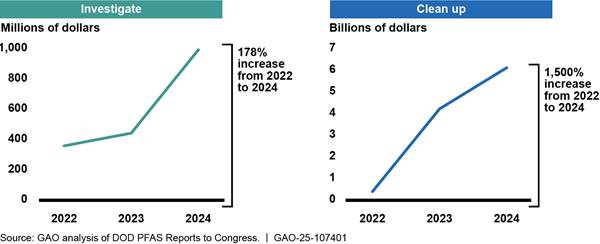

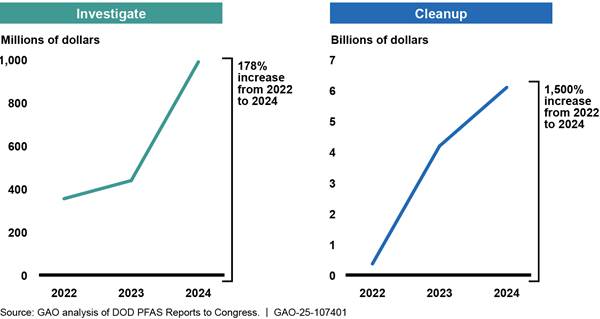

DOD efforts to investigate its PFAS releases have generally been thorough, and the department reports on the pace and cost of its efforts to Congress. DOD estimates that its future PFAS investigation and cleanup costs will total more than $9.3 billion in fiscal year 2025 and beyond. DOD’s estimated future PFAS investigation and cleanup costs have more than tripled since 2022. GAO found that costs will continue to increase as DOD learns more about the extent of its PFAS releases—including the breadth and depth—through remedial investigations and determines what cleanup actions are required.

Department of Defense (DOD) Estimated Future Costs for the Investigation and Cleanup of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)by Fiscal Year

DOD has not communicated to Congress the full range of cost variables for future PFAS cleanup, referred to as total fiscal exposure. By including a detailed explanation and examples of changing key cost drivers for PFAS investigation and cleanup in its semi-annual cost report to Congress or other congressional reporting mechanism, Congress will be better equipped to make decisions regarding future funding for PFAS investigation and cleanup activities.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

AFFF |

Aqueous Film Forming Foam |

|

BRAC |

Base Realignment and Closure |

|

CERCLA |

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DLA |

Defense Logistics Agency |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FUDS |

Formerly Used Defense Sites |

|

HFPO-DA |

hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid |

|

NCP |

National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan |

|

PFAS |

per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

|

PFBA |

perfluorobutanoic acid |

|

PFBS |

perfluorobutanesulfonic acid |

|

PFHxA |

perfluorohexanoic acid |

|

PFHxS |

perfluorohexanesulfonic acid |

|

PFNA |

perfluorononanoic acid |

|

PFOA |

perfluorooctanoic acid |

|

PFOS |

perfluorooctane sulfonate |

|

PFPrA |

perfluoropropanoic acid |

|

ppt |

parts per trillion |

|

RCRA |

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, as amended |

|

TFSI |

bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)amine |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

February 24, 2025

Congressional Committees

The Department of Defense (DOD) has spent $2.6 billion since 2017 investigating and cleaning up per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), chemicals that are heat and stain resistant and can persist in the environment—including in water, soil, and air—for decades or longer. Investigating where PFAS may have been released and cleaning them up are complex and time intensive processes that have been affected by evolving regulations, emerging technologies, barriers presented by the natural environment, and a changing understanding of the potential risks posed by these chemicals.

PFAS are found in many consumer products, as well as in industrial products such as certain firefighting agents called aqueous film forming foam (AFFF). Since 1970, DOD used AFFF to extinguish fires quickly and keep them from reigniting, and until recently, AFFF was the designated firefighting agent for fuel fires at military facilities. Use of AFFF for fire training and suppression, accidental spills, and other activities in and around DOD installations, has led to releases of PFAS into the environment, potentially exposing service members, their families, and surrounding community members to these chemicals.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), exposure to certain PFAS—such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)[1]—may have adverse effects on human health, including effects on fetal development, the immune system, and the thyroid, and may cause liver damage and cancer.[2] DOD has developed strategic performance goals to address past DOD PFAS releases and to find and implement alternatives to the use of AFFF.[3]

Our prior work has examined the department’s efforts to investigate PFAS, respond to contamination, eliminate the use of AFFF, and report future costs to Congress.[4] For example, in June 2021 we found that DOD had not reported future PFAS investigation and cleanup cost estimates, or the scope and limitations of those estimates, in its annual environmental reports to Congress.[5] We recommended that the department annually include the latest cost estimates for future PFAS investigation and cleanup in DOD’s environmental reports to Congress. Thereafter, DOD issued its fiscal year 2020 environmental report to Congress in March 2022, which includes estimated future PFAS remediation costs.[6] Additionally, we have examined current and promising technologies and methods that could improve the detection and treatment of PFAS in the environment and provided policy options to Congress and other stakeholders that could enhance benefits or mitigate challenges of these technologies.[7]

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 includes a provision for us to examine the state of ongoing testing and remediation by DOD of current or former military installations contaminated with PFAS.[8] This report 1) describes the status of DOD’s efforts to test and remediate PFAS at current or former military installations; 2) assesses the extent to which DOD has analyzed whether its efforts to test and remediate PFAS are on pace, thorough, and cost-effective; and (3) discusses the steps taken to address challenges related to testing and remediation of PFAS at current or former military installations.

To address these objectives, we obtained and analyzed data from fiscal years 2017 to June 2024 on the status of the department’s efforts to investigate and cleanup PFAS. To identify any trends in DOD’s efforts, we also analyzed the department’s PFAS investigation and cleanup progress reports submitted to Congress. In addition, we randomly selected a nongeneralizable sample of 18 installations allocated across a range of cost and pace categories and analyzed certain DOD reports from those installations to identify, among other things, specific activities that demonstrate thoroughness, including environmental analyses, land surveying, and sampling procedures. We determined the data to be sufficiently reliable for the purpose of reporting the status of DOD installations where PFAS testing and remediation is taking place.

In addition to our data collection and analysis, we interviewed officials from the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and the Environment, the EPA, and the military services to determine how the cleanup program is managed and evaluated. We also reviewed regulations relevant to PFAS cleanup. A detailed discussion of our scope and methodology is in appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to February 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

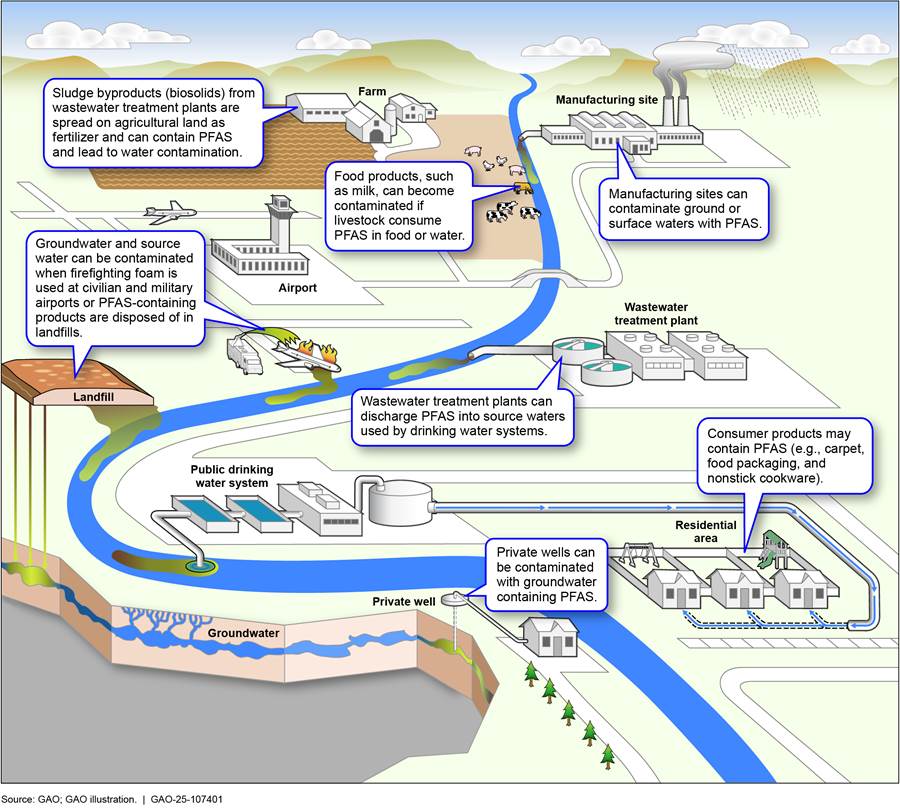

Background

The Characteristics, Sources, and Health Impacts of PFAS

PFAS are a group of synthetic chemicals that have been linked to harmful health effects. For decades, PFAS have been used in a wide range of products including stain-resistant furniture, waterproof clothing, nonstick cookware, and certain firefighting foams like AFFF. PFAS have entered and spread throughout the environment and can be persistent, as they are resistant to degradation and can bioaccumulate in humans, animals, and plants. There are many contributors to PFAS contamination, including private industry, and PFAS can enter the environment through numerous pathways (see fig. 1). Releases of PFAS from AFFF as well as from other DOD activities—such as metal plating—have resulted in PFAS contamination of drinking water, groundwater, and soil in and around military installations.[9]

Figure 1: Examples of How Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Can Enter the Environment and Drinking Water

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most Americans have PFAS in their blood. Human exposure to PFAS can increase the risk of certain cancers, immune system damage, developmental delays, and fertility issues, according to the EPA.

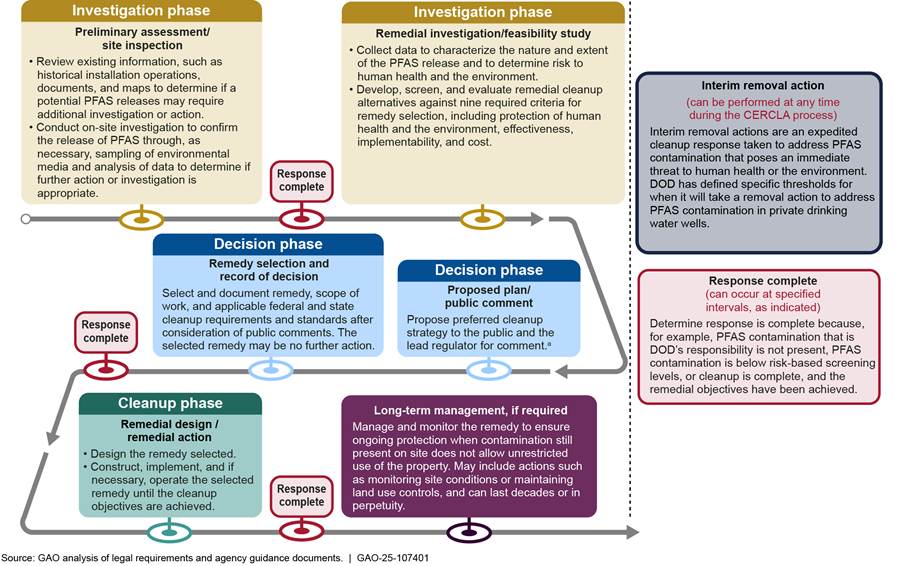

DOD’s Environmental Restoration Process for Addressing PFAS

DOD conducts environmental restoration activities under the Defense Environmental Restoration Program to reduce risk to human health and the environment resulting from the department’s actions.[10] The Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment is responsible for establishing policy, issuing guidance, and providing oversight for the department’s environmental restoration program. DOD components—which include the military departments and the Defense Logistics Agency—are to budget for and conduct environmental restoration activities at their installations. Moreover, in July 2019, DOD established a PFAS Task Force, which oversees DOD’s PFAS-related activities and provides strategic leadership and direction to ensure a consistent and holistic approach.[11] The task force is composed of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Energy, Installations, and Environment; the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs; and the assistant secretaries of the Army, Navy, and Air Force with responsibility for energy, installations, and the environment.[12]

DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are conducted in accordance with the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, as amended (CERCLA), as well as other relevant statutes and regulations.[13] CERCLA, commonly known as Superfund, authorizes the President to respond to releases or threatened releases of any hazardous substances into the environment or of any pollutants or contaminants into the environment that may present an imminent and substantial danger to public health or welfare. In the late 1980s, the President delegated CERCLA’s response authorities to EPA and other federal agencies. If there is a release from a federal facility, the agency that administers the facility—such as DOD—is authorized to take response actions under CERCLA, subject to oversight by EPA and the states in which those facilities are located.[14] Subject to limited exceptions, CERCLA requires DOD and other federal agencies to comply with the statute and all guidelines, rules, regulations, and criteria applicable to remedial actions to the same extent as non-federal entities.[15]

The National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan outlines procedures and standards for implementing the CERCLA process and designates DOD as the lead agency for planning and implementing response actions for releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants from defense sites.[16] There are several activities in a typical CERCLA response, including investigation, decision-making, and cleanup activities. For example, under CERCLA, DOD identifies, evaluates, and, where appropriate, responds to known or potential DOD releases of PFAS into the environment—such as releases of PFAS from the use of certain firefighting foam.[17] Figure 2 outlines DOD’s approach to addressing PFAS contamination within the steps of the CERCLA process. See appendix III for additional details on each phase.

Figure 2: Department of Defense’s (DOD) Process for Implementing the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, as amended (CERCLA) Cleanup Process to Address Releases of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from DOD Activities

Note: This figure groups the CERCLA cleanup framework into the high-level phases of investigation, decision, and cleanup, as generally set forth in the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan (NCP) at 40 C.F.R. Part 300. DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix 1 in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

aThe Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which generally oversees the CERCLA program, defines the lead regulator as the primary agency (i.e. EPA or the state) that oversees the cleanup. See EPA, Lead Regulator Policy for Cleanup Activities at Federal Facilities on the National Priorities List (Nov. 6, 1997).

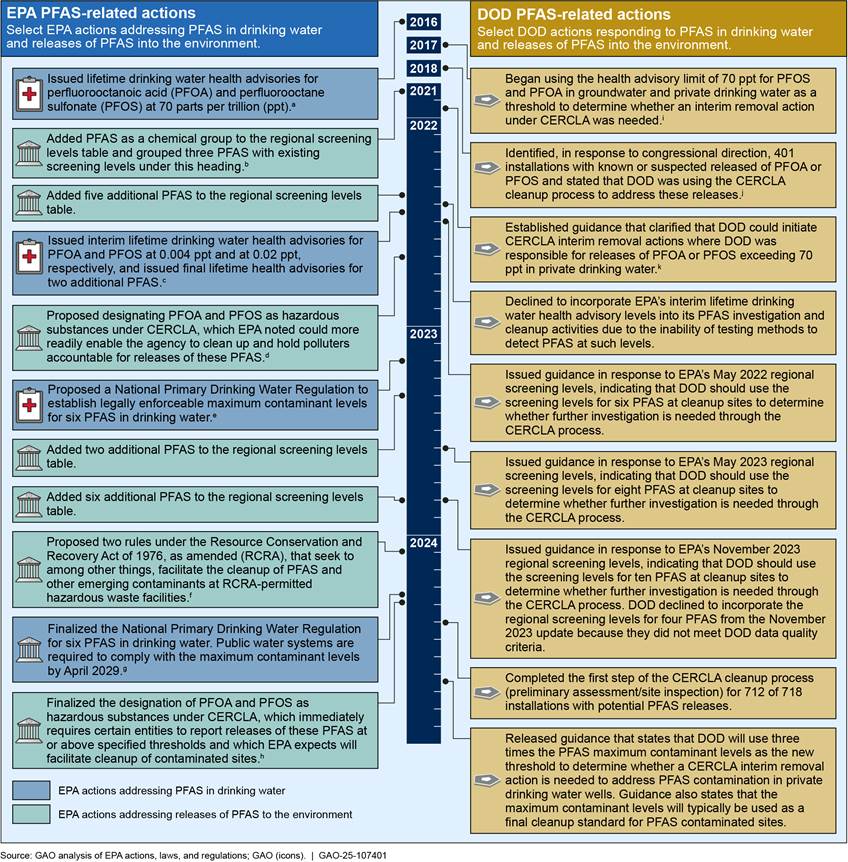

Environmental Protection Agency PFAS Screening Levels and Recent Regulations

While CERCLA authorizes federal agencies like DOD to respond to releases of hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants from their activities, the Superfund program and certain other federal environmental statutes (like the Safe Drinking Water Act) are generally administered by EPA. In this role, EPA has taken a number of regulatory and other actions in recent years to address PFAS contamination in the environment, including (1) issuing regional screening levels for PFAS in contaminated media at cleanup sites, (2) issuing health advisory levels for certain PFAS in drinking water, (3) promulgating enforceable maximum contaminant levels for specific PFAS in drinking water, and (4) designating two PFAS as hazardous substances under CERCLA. Generally, DOD has incorporated EPA’s efforts into its approach to addressing PFAS contamination, as discussed below.

Regional screening levels. EPA develops regional screening levels for chemical contaminants at Superfund sites. These screening levels are risk-based values that are used to identify contaminated media (e.g., tap water, and soil) at cleanup sites that may need further investigation. EPA calculates these values based on standard exposure assumptions and toxicity data. Regional screening levels are not final cleanup standards, but rather are risk-based values that help agencies determine whether to proceed in the CERCLA investigation process at a site.

In recent years, EPA has added a range of PFAS to its regional screening levels tables. In 2021, EPA added PFAS as a chemical group to the regional screening level tables. Thereafter, in 2022 and 2023, EPA added screening levels for 13 additional PFAS in residential and industrial soil, groundwater, and tap water. For example, the May 2023 regional screening levels for PFOS and PFOA in residential tap water were 4 parts per trillion (ppt) and 6 ppt, respectively.[18] As of November 2024, EPA has identified regional screening levels for 15 PFAS.

DOD guidance instructs DOD components to incorporate certain EPA regional screening levels for 10 specific PFAS into ongoing and future preliminary assessments and site inspections, and to use those screening levels to determine if further investigation in the remedial investigation phase is warranted or if no further action is required at a site.[19] Further, this guidance instructs that sites determined to require no further action under outdated screening levels should be reassessed as levels are updated. The guidance indicates that screening levels for PFAS from EPA’s regional screening levels tables are incorporated into DOD’s environmental cleanup investigations when DOD determines that the levels are derived from final, peer reviewed toxicity values that meet certain DOD-identified criteria.[20]

Health advisory levels. Under the Safe Drinking Water Act, EPA issues health advisories to provide information on contaminants not subject to drinking water regulations, including those that can cause adverse human health effects and that are known or anticipated to occur in drinking water. Drinking water health advisory levels are nonenforceable and nonregulatory, but rather provide technical information on the health risk of identified but unregulated chemicals to drinking water system managers, government officials, and others with primary responsibility for overseeing water systems. Health advisories may offer a margin of protection by defining a level of drinking water concentration at or below which exposure is not anticipated to lead to adverse health effects.

In 2016, EPA issued two lifetime drinking water health advisories for PFOA and PFOS at 70 ppt individually or summed.[21] Thereafter, DOD required military installations to test drinking water in DOD-owned drinking water systems for PFOS and PFOA and established required actions if test results were greater than 70 ppt.[22]

In June 2022, EPA issued updated interim drinking water health advisory levels for PFOS and PFOA—at 0.02 ppt and 0.004 ppt respectively.[23] These superseded EPA’s 2016 health advisory levels. EPA also issued final health advisories for two additional PFAS.[24] The updated 2022 interim health advisory levels were lower than available EPA testing methods could detect, so DOD elected not to revise its drinking water policies to reflect the new interim levels.

Maximum contaminant levels. The Safe Drinking Water Act authorizes EPA to establish legally enforceable standards for public water systems—called National Primary Drinking Water Regulations—that generally limit the levels of specific contaminants in drinking water.[25] In April 2024, EPA promulgated such a regulation—the PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation—that established enforceable maximum contaminant levels for six PFAS in drinking water. EPA set individual maximum contaminant levels for five PFAS and a maximum contaminant level for mixtures, which includes a sixth PFAS.[26] For example, the rule sets individual maximum contaminant levels for PFOA and PFOS at 4 ppt each. This regulation applies to certain public water systems, including those owned by DOD.[27] Such systems will be required to monitor drinking water for the regulated PFAS, and systems with any of the regulated PFAS above allowable levels will be required to take actions to reduce their levels of PFAS, such as by implementing a treatment method by April 2029, when all public water systems are required to comply with the maximum contaminant levels. DOD is conducting sampling of its water systems and is taking actions to ensure compliance with the regulation within the 5-year time frame.

CERCLA designation. Among other things, CERCLA (1) gives EPA the authority to respond to actual and threatened releases of hazardous substances to the environment, (2) authorizes EPA to compel parties potentially responsible for those releases to clean up contaminated sites, (3) allows EPA to pay for cleanups and seek reimbursement from potentially responsible parties,[28] and (4) establishes a Hazardous Substance Superfund (trust fund) to provide funding for cleanups at certain nonfederal sites and related program activities. Federal agencies like DOD, however, are prohibited from using the Superfund trust fund to finance their cleanups and must, instead, use their own or other appropriations.

In April 2024, EPA finalized a rule designating PFOS and PFOA as hazardous substances under CERCLA.[29] The new rule is expected to strengthen EPA’s ability to clean up non-federal sites contaminated with PFOS and PFOA and to hold responsible parties accountable for addressing significant contamination and cleanup costs. However, as noted above, because DOD has already been using its CERCLA authorities to respond to its releases of PFAS, DOD officials do not anticipate that this new rule will result in substantial changes to DOD’s approach to PFAS cleanup.

As discussed in detail below, DOD incorporated EPA’s 2016 PFAS drinking water health advisory levels and 2024 maximum contaminant levels into the department’s efforts to address PFAS contamination under CERCLA.[30] See appendix V for a summary of EPA’s PFAS-related actions and the department’s response.

DOD’s Methods for Testing, Remediating, Disposing of, and Destroying PFAS

PFAS can contaminate multiple types of media, including soil, groundwater, surface water, wastewater, and drinking water. DOD uses different methods for testing, remediating, disposing of, and destroying PFAS based on the type of media.

Testing. DOD uses different testing methods for drinking water versus all other types of contaminated media. DOD guidance states that the services should use one EPA method that tests for certain PFAS in drinking water and another EPA method that measures or tests for PFAS in all other media.[31] Both methods use similar laboratory techniques to test for PFAS; however, they differ in sensitivity and types of PFAS detected. The methods used to test drinking water are “targeted methods,” which means they can be highly sensitive and accurate, and they can detect 29 different PFAS. The method used for other media like soil and groundwater can detect a greater number of PFAS (40).[32]

Remediation, Disposal, or Destruction. DOD uses different approaches for remediating, disposing of, or destroying PFAS-contaminated media (see table 1 below). After removal or remedial actions are conducted, there may be a need for disposal or destruction of PFAS-impacted materials. Remediation, disposal, or destruction decisions are made based on site-specific characteristics, resources, and objectives.

Table 1: Types of Department of Defense (DOD) Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Remediation, Disposal, and Destruction Options

|

Remediation |

The primary remediation technology for removing PFAS in groundwater is “pump and treat” or variations of it. For example, contaminated groundwater is pumped out of the ground, run through a filter, and injected back underground or otherwise discharged. Similarly, PFAS can be filtered out of drinking water using a point of entry system. |

|

Disposal |

According to a DOD memo from July 2023, PFAS contaminated media can be disposed of in hazardous waste landfills with environmental permits or solid waste landfills with environmental permits, composite liners, and gas/leachate collection and treatment systems.a DOD guidance also allows on-site hazardous waste storage and underground injection control on a site-specific basis. |

|

Destruction |

Incineration is the primary destruction option. DOD identified hazardous waste incineration with an environmental permit as an option but has not utilized this option per a DOD memo from July 2023.b Incineration has the potential to fully destroy PFAS with optimal temperature, incineration time, and mixture of media; however, there is a possibility that smaller PFAS molecules may not be destroyed or captured in air pollution equipment. Additionally, methods to identify and quantify PFAS in the air are under development; however, the lack of standardized testing methods for PFAS emissions introduces uncertainty in the understanding of PFAS releases into the air. |

Source: GAO analysis of DOD and Environmental Protection Agency information. | GAO‑25‑107401

Note: DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix I in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

aSee Assistant Secretary of Defense (EI&E) Memorandum, Memorandum for Sampling of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in DOD-Owned Drinking Water Systems. (July 11, 2023).

bSee Assistant Secretary of Defense Memorandum, Guidance on Incineration of Materials Containing Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. (July 14, 2023).

DOD Has Completed Nearly All Preliminary Assessments and Site Inspections of PFAS Releases, and Some Remediation Efforts Are Underway

DOD Has Completed Assessments and Inspections at 712 of 718 Installations Identified with Potential PFAS Releases

As of June 2024, DOD had identified 718 military installations where PFAS was used or may have been released, and nearly all (712 of 718) have completed the first step of the CERCLA process—the preliminary assessment and site inspection—as shown in figure 3. The Explanatory Statement for the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, directed DOD to submit a report to the congressional defense committees that assessed the number of current and former military installations where AFFF was used or in use and the impact of PFAS contaminated drinking water on surrounding communities.[33] DOD officials told us they reviewed their inventory of nearly 4,700 installations that had reported the release of any contaminant, pollutant, or hazardous substance and identified installations where PFAS may have been released.[34]

Figure 3: Department of Defense (DOD) Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Cleanup Status of Current or Former Military Installations, as of June 30, 2024

Note: DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix I in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

aDOD is following the CERCLA cleanup process to address releases of PFAS from DOD activities. For a description of the phases in a typical CERCLA cleanup, see figure 2 in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

Of the 712 that have completed the first step of the CERCLA process, 132 installations required no further action because either the preliminary assessment did not identify any PFAS releases, or the site inspection found PFAS at concentrations less than the regional screening levels, according to DOD officials.[35] DOD determined that for the remaining 580 installations, further investigation is needed and is proceeding to the next step of the CERCLA process. Nearly two-thirds (370 of 580) of these installations have started the remedial investigation and feasibility study step. According to DOD officials, while no installation has started the cleanup phase, DOD has taken interim removal actions to address immediate risks at or near (i.e. on base or off base) 82 installations and plans to take interim removal actions at 3 additional installations, as discussed below.

DOD Has Taken Interim Removal Actions to Address Immediate Health and Safety Concerns Related to Releases of Certain PFAS

As of June 2024, 85 on-base interim removal actions have been completed or are underway at 47 installations and on-base interim removal actions are planned at 15 installations to address releases of certain PFAS that may pose immediate health concerns. Additionally, 55 installations performed or are performing off-base interim removal actions to address releases of certain PFAS that posed immediate health concerns.[36] At any point during the CERCLA process, DOD may perform a removal action where there is a release or substantial threat of a release into the environment of any hazardous substance or where there is a release or substantial threat of a release into the environment of any pollutant or contaminant which may present an imminent and substantial danger to the public health or welfare. According to officials, DOD has performed interim removal actions on-base to prevent further plume migration (the movement of contaminants through soil and water) and off-base to address a drinking water exposure. Also, DOD officials explained that groundwater extraction or soil removal has been used to prevent PFAS contaminated plumes from spreading. DOD has addressed PFAS-contaminated drinking water by providing alternative drinking water (e.g. bottled water), installing point of use or whole house filtration systems, or connecting homes to a public water system without contamination.[37]

Until recently, DOD’s threshold for determining when an interim removal action was needed to address DOD releases of PFAS in drinking water was EPA’s 2016 lifetime drinking water health advisory level of 70 ppt for PFOS and PFOA (individually or summed). If either PFOS, PFOA, or a combination of the two chemicals were found in a drinking water sample higher than 70 ppt, DOD performed an interim removal action.[38]

DOD updated its guidance in September 2024 electing to implement a new lower threshold for interim removal actions to address PFAS contamination in private drinking water.[39] This update was in response to EPA’s April 2024 promulgation of the new PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation—which set maximum contaminant levels for PFOS and PFOA at 4 ppt each. Specifically, DOD’s new threshold is three times the maximum contaminant levels. According to DOD officials, this threshold was selected based on factors such as prioritizing action where PFAS levels in drinking water are the highest and ensuring contamination is above background concentrations of PFAS.[40] The guidance also states that the updated threshold for interim removal actions will result in DOD returning to private drinking water wells where PFOS or PFOA levels were detected below 70 ppt but above 12 ppt to consider performing a removal action.[41] Officials told us that DOD does not have the data on how many additional private drinking water wells will need to be addressed. The guidance also notes that in most cases the PFAS maximum contaminant levels will be applied as a final cleanup standard to be attained for groundwater and drinking water during CERCLA remedial actions.

Interim removal actions are often not a final solution, and a site may continue through the CERCLA process after a removal action has been implemented. See table 2 for a summary of DOD’s interim removal actions performed to address releases of certain PFAS as of June 2024.

Table 2: Department of Defense (DOD) On-Base Interim Removal Actions to Address Releases of Certain Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), as of June 2024

|

On-base Interim Removal actions |

Army |

Air Force |

Navya |

Defense Logistics Agencyb |

Formerly Used Defense Sitesc |

Total |

|

Planned |

0 |

15 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

19 |

|

Underway |

6 |

52 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

65 |

|

Completed |

0 |

18 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

20 |

|

Total |

6 |

85 |

11 |

2 |

0 |

104 |

Source: DOD PFAS data. | GAO‑25‑107401

Note: DOD is following the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) cleanup process to address releases of PFAS from DOD activities. Under CERCLA, DOD may perform a removal action to address contamination that poses an immediate threat to public health or the environment. Certain types of removal actions, such as providing bottled water, may not provide the protection or permanence of long-term remediation. DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix I in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

aThe Department of the Navy consists of two services—the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps.

bDefense Logistics Agency is a combat support agency involved in hazardous waste storage or disposal as well as environmental compliance and cleanup. Defense Logistics Agency installations include six fuel support points, one distribution center, and two supply centers.

cFormerly Used Defense Sites are sites located on properties that were once under DOD’s jurisdiction and owned, leased, or otherwise possessed by the United States at the time of the actions leading to contamination but were conveyed out of DOD’s jurisdiction prior to October 17, 1986.

DOD Assesses Pace, Thoroughness, and Cost of Its PFAS Testing and Remediation Efforts, but Full Costs Are Unknown

DOD Has Made Some Progress in Addressing PFAS Releases and Has Reported on Its Pace to Congress

DOD has made some progress conducting PFAS testing through preliminary assessments and site inspections and beginning or planning for remedial investigations, and the department continues to assess its pace while preparing required reports to Congress.[42] The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022 required DOD to complete the preliminary assessment and site inspection testing for PFAS no later than December 2023 at all military installations and National Guard facilities located in the United States that were identified as having a release of PFAS as of March 31, 2021.[43]

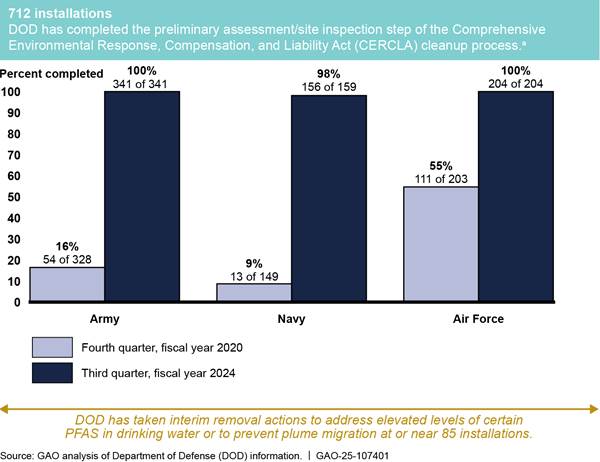

In 2021, we reported that DOD had completed about one-quarter (181 of 687) of the preliminary assessments and site inspections at installations identified for potential remediation of PFAS.[44] As of June 2024, DOD has completed nearly all (712 of 718) preliminary assessments and site inspections. Progress by military department is shown in figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Department of Defense (DOD) Progress Since 2020 in Completing Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Preliminary Assessments and Site Inspections, as of June 2024

Note: The Department of the Navy consists of two services—the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. The Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) installations and Formerly Used Defense Sites (FUDS) comprised less than 10 each and are not shown in the figure. According to DOD officials, as installations where PFAS was used or may have been released were identified, they were added to the department’s list of installations potentially needing PFAS remediation. The number of installations identified to have a PFAS release has increased over the past several years, which accounts for different totals between fiscal years 2020 and 2024.

aDOD is following the CERCLA cleanup process to address releases of PFAS from DOD activities. For a description of the phases in a typical CERCLA cleanup, see figure 2 in this report (GAO‑25‑107401). DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix I in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

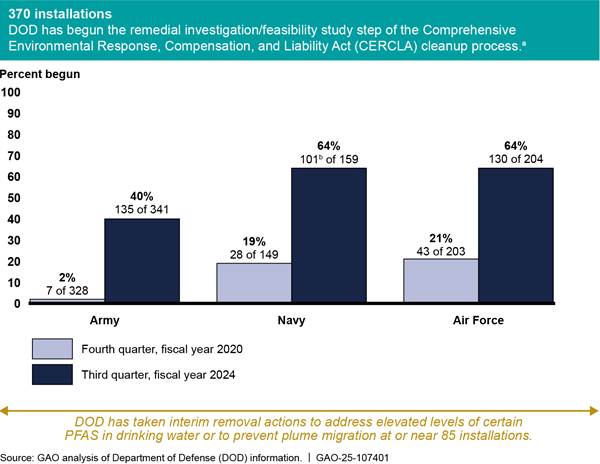

Moreover, as shown in figure 5, DOD has also made progress in its remedial investigations of PFAS releases to determine the release source, exposure pathway, nature and extent of contamination, and level of risk to human health. In 2021, we reported that DOD had begun 78 remedial investigations to address releases of PFAS at installations determined to need further action under CERCLA. As of June 2024, DOD had 370 (of 580) installations where remedial investigations were underway and has planned remedial investigations to address releases of PFAS at the remaining 210 installations.[45] DOD guidance notes there is variability in the amount of time CERCLA phases can take because conditions can vary from one site to the next. The Army and Air Force estimate completing remedial investigations and feasibility studies for PFAS releases over the next 6 years, and the Navy estimates nearly 10 years.

Figure 5: Department of Defense (DOD) Progress Since 2020 in Beginning Remedial Investigations and Feasibility Studies to address Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), as of June 2024

Note: The Department of the Navy consists of two services—the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. The Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) installations and Formerly Used Defense Sites (FUDS) comprise less than 10 each and are not shown in the figure. According to DOD officials, as installations where PFAS were used or may have been released were identified, they were added to the department’s list of installations potentially needing PFAS remediation. The number of installations identified to have a PFAS release has grown over the past several years, which accounts for different totals between fiscal years 2020 and 2024.

aDOD is following the CERCLA cleanup process to address releases of PFAS from DOD activities. For a description of the phases in a typical CERCLA cleanup, see figure 2 in this report (GAO‑25‑107401). DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix I in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

bAccording to DOD officials, two installations of the 101 for the Navy have the preliminary assessment and site inspection underway concurrently.

DOD Efforts to Investigate PFAS Releases Have Generally Been Thorough, and DOD Is Adapting to New EPA Regulations

|

Air Force National Guard Soil Sampling The Air Force National Guard Truax Field facility in Wisconsin underwent extensive soil sampling for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Spring of 2022. Using a large drill, over 220 “bore sites” were dug and sampled to decide which sites needed further PFAS testing and remediation. To determine the permeability and conductivity of the soil, tests were performed at 30 targeted points. Permeability and conductivity of the soil define the preferred pathway for contaminant migration. The data collected inform where the PFAS contamination could spread to and where remediation efforts should be targeted.

Source: Department of Defense documentation; Department of Defense/SMSgt Paul Gorman (photo). | GAO‑25‑107401 |

Our analyses—which included analysis of 18 randomly selected preliminary assessment and site inspection reports—found that DOD efforts for investigating releases and potential releases of PFAS from its activities have generally been thorough. For example, DOD conducted a range of activities during the preliminary assessment and site inspection step of the CERCLA process to ensure thoroughness, including extensive soil sampling (see sidebar). DOD and military service officials responsible for PFAS testing and remediation told us that they have used EPA’s evolving PFAS regional screening levels in accordance with DOD policy to ensure thoroughness in testing for PFAS releases and to appropriately determine if sites should move onto the next phase of CERCLA cleanup. As the regional screening levels have been updated, DOD has released guidance instructing the services how to apply the revised screening levels when testing for PFAS.[46] Further, according to DOD officials and documentation, the department seeks input from relevant regulators throughout the process. Table 3 below shows examples of activities conducted during the first step of the CERCLA process, including environmental analyses, conceptual site models, land surveying, and sample collection that demonstrate general thoroughness.

Table 3: Examples of Department of Defense’s (DOD) Efforts to Investigate Releases or Potential Releases of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)

|

Preliminary assessment |

Site inspection |

|

· Reviewing historical documents, such as historical aerial photos or Sanborn maps · Conducting site visits to complete visual inspections at suspected PFAS-release locations · Interviewing relevant personnel, such as those in environmental management and nearby fire departments · Identifying areas of interest to develop conceptual site models that summarize potential source-pathway-receptor linkages · Conducting environmental analysis of surrounding geology, hydrogeology, climate, land use, sensitive habitats, and threatened or endangered species · Analyzing past and present activities at each area of interest identified during the preliminary assessment |

· Obtaining clearance from nearby utilities · Performing direct push boring for soil sample collection · Installing temporary monitoring wells for groundwater sample collection · Surveying surrounding land · Conducting readiness reviews, which cover anticipated hazards, types and proper use of equipment needed for the field activities, sampling procedures, and procedures used to prevent cross-contamination · Sending collected samples to accredited laboratories for testing |

Source: GAO review of DOD information. | GAO‑25‑107401

Note: DOD is following the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) cleanup process to address release of PFAS from DOD activities. The first step in the CERCLA cleanup process is the preliminary assessment/site inspection. For a description of the phases in a typical CERCLA cleanup, see figure 2 in this report (GAO‑25‑107401). DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix I in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

While DOD’s efforts have been thorough thus far, EPA’s April 2024 PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation, which established maximum contaminant levels covering six PFAS, could require reevaluation of past site inspections of some installations, according to DOD officials. DOD officials stated that, as of June 30, 2024, 132 installations were deemed “no further action needed” to address PFAS releases. Of those installations, officials stated that 72 did not have PFAS detected during the preliminary assessment or site inspection, leaving 60 installations that are or will be reevaluated and may need remedial investigations.

DOD Estimates PFAS Investigation and Cleanup Costs Near $9 Billion and Expects Significant Increases, As Full Costs Are Unknown

DOD Estimates for Future PFAS Investigation and Cleanup Costs Have More than Tripled Since 2022 and Costs Are Expected to Rise

DOD has spent $2.6 billion on the investigation and cleanup of PFAS from 2017 to 2023.[47] In a May 2024 report to Congress, DOD provided a point estimate of at least another $7 billion in expected future PFAS investigation and cleanup costs, as shown in table 4 below.[48]

Table 4: Department of Defense (DOD) Actual and Estimated Costs for the Investigation and Cleanup of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) at Military Installations, as of May 2024 (in millions)

|

|

Through FY2021 actual |

FY2022, |

FY2023, |

FY2024, estimates |

FY2025 and beyond |

Total, actual and estimated |

|

Investigate |

673.1 |

352.1 |

339.5 |

142.3 |

989.7 |

2,496.7 |

|

Cleanup |

351.1 |

62.3 |

82.7 |

55.3 |

6,100 |

6,651.4 |

|

Total |

1,024.2 |

414.4 |

422.2 |

197.6 |

7,089.7 |

9,148.1 |

Source: DOD PFAS Report to Congress. | GAO‑25‑107401

Note: DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix I in this report (GAO‑25‑107401). The table includes active installations, National Guard facilities, and Formerly Used Defense Sites with funding provided by either the environmental restoration or operation and maintenance appropriation accounts. This table does not include PFAS investigation and cleanup costs at Base Realignment and Closure locations with funding provided by military construction appropriation accounts.

In 2023, the department was directed to report semiannually to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees on the costs associated with investigating and cleaning up PFAS at sites where funding is provided by either environmental restoration or operation and maintenance appropriations.[49] In response, DOD submitted its first required report to Congress in May 2024 that included—by component and installation—planned, actual, and estimated obligations separately for PFAS investigations and cleanup.[50] Our analysis shows that the department’s estimated future PFAS investigation costs more than tripled since 2022, while estimates for future PFAS cleanup costs have increased 15-fold, as shown in figure 6 below. We found that future costs will continue to increase as DOD learns about the extent of its PFAS releases—including the breadth and depth—through remedial investigations and determines what cleanup actions are required.

Figure 6: Department of Defense (DOD) Estimated Future Costs, by Fiscal Year, for the Investigation and Cleanup of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) at Military Installations, as of May 2024

Note: DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup activities are focused on 10 specific PFAS. For more information about these specific chemicals, see appendix I in this report (GAO‑25‑107401). The table includes active installations, National Guard facilities, and Formerly Used Defense Sites with funding provided by either the environmental restoration or operation and maintenance appropriation accounts. This figure does not include PFAS investigation and cleanup costs at Base Realignment and Closure locations with funding provided by military construction appropriation accounts.

DOD acknowledged in the May 2024 report that estimated future PFAS investigation and cleanup costs are expected to increase as the DOD components complete ongoing remedial investigations, determine what cleanup actions are required, and implement new guidance and regulations issued by the EPA.[51] More specifically, according to officials, as these investigations are completed, installations will have more information on the extent of releases and can determine what cleanup actions are required, which will allow the department to develop better cost estimates. The department does not yet have data at many of its installations that show the speed of groundwater flow based on the type of soil or depth of any single plume, nor does it have complete data from monitoring wells that could indicate where the end of the plume is located (e.g., 1 mile, 10 miles, 30 miles), or the concentrations throughout the plume.

Additionally, in nearly all cases, the department also does not yet know the volume of PFAS released at each site or the background concentrations of PFAS. These factors could affect the final cleanup decisions, which in turn directly affects the length of time to operate the remedy and affects associated costs. DOD also cited EPA guidance and regulations, such as the updated regional screening and maximum contaminant levels, as drivers of increasing costs. The May 2024 report notes that the department will plan and program for these requirements as they are defined.

DOD Reports Limited Information About Full Estimated Costs for Future PFAS Investigations and Cleanup

DOD’s May 2024 report provides limited information about the full estimated future costs to be incurred by DOD for PFAS investigation and cleanup. Specifically, as described above, the department has identified 580 installations—active, national guard, formerly used defense sites, and Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) locations—that need to complete their remedial investigations to address releases of PFAS. However, the May 2024 report recorded zero dollars as DOD’s planned future cleanup obligations after fiscal year 2024 for more than half of the other identified installations.[52]

According to DOD officials, in some cases the report recorded zero dollars as DOD’s planned future cleanup obligations after fiscal year 2024 because DOD has developed these cost estimates based on the federal accounting standards. These standards have specific rules about including or excluding certain costs from estimates regarding expected future cleanup work. For example, for costs to be included in cleanup estimates based on the federal accounting standards, they must be both probable and reasonably estimable.[53]

DOD officials explained that the department cannot estimate how long it will take or how much it will cost to completely address its PFAS releases at its installations until it knows the extent of those releases, meaning that many expected future costs are not currently reasonably estimable. DOD’s current PFAS investigation and cleanup estimates based on the federal accounting standards give DOD leadership insight into the likely minimum costs for PFAS investigation and cleanup. However, the estimates provide little insight into how high those costs might rise, thus limiting their utility for congressional planning purposes.

As noted above, DOD has been directed to report to the congressional appropriations committees on the estimated future costs, after fiscal year 2024, associated with investigating and cleaning up PFAS. However, when directing DOD to report on these costs, congressional committees did not require DOD to adhere to the federal accounting standards and report only those expected PFAS investigation and cleanup costs that meet such standards.

Moreover, the May 2024 report includes expected future costs associated with investigating and cleaning up PFAS at sites with funding provided by either environmental restoration or operation and maintenance appropriation accounts. These appropriations include active installations, National Guard facilities, and Formerly Used Defense Sites. However, the May 2024 report does not include estimated costs for PFAS investigation and cleanup at 116 BRAC locations with funding provided by military construction appropriation accounts. The department estimates at least another $2 billion in expected future PFAS investigation and cleanup costs for these BRAC locations in addition to the $7 billion in expected future costs for the other installations included in the May 2024 report. DOD is not required to include future PFAS cleanup cost estimates for BRAC locations in its required semiannual cost report to Congress; however, without this detail, Congress lacks full visibility into additional billions of dollars needed for PFAS investigation and cleanup activities at all DOD sites.

Since 2003, we have consistently recommended that agencies maintain clear and open communication with Congress concerning their future financial obligations, which include both known and unknown future fiscal exposures.[54] Fiscal exposures are responsibilities, programs, and activities that may legally commit the federal government to future spending or create expectations for future spending based on current policy, past practices, or other factors. While federal accounting standards require certain expected future cleanup costs to be reported or disclosed in federal agencies’ financial statements, these do not represent the total federal fiscal exposure, meaning the total amount that the federal government may have to pay to clean up contamination. The total fiscal exposure includes costs to clean up known sites that are not currently reasonably estimable and unknown cleanup costs that may be identified in the future as remedial investigations are completed. Additionally, we have previously reported on concerns with the department’s cleanup cost estimates and the importance of providing Congress with visibility into significant cost increases to clean up PFAS.[55]

Moreover, GAO’s Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide provides guidance on developing various kinds of cost estimates for federal agencies.[56] The cost guide acknowledges that developing reliable cost estimates can be challenging, but that it is proper and prudent to complete estimates with the best available information at the time, while also documenting the estimate’s shortcomings. For example, the guide includes a best practice that a risk and uncertainty analysis should be conducted, which quantifies the imperfectly understood risks and uncertainties and identifies the effects of changing key cost driver assumptions and factors.[57] Using risk and uncertainty analysis can inform decision-makers about a program’s potential range of costs and cost drivers, while a point estimate by itself provides no information about the underlying uncertainty of the estimate and is insufficient for making good decisions about the program.

While DOD knows there will be future PFAS investigation and, likely, cleanup needed at 580 installations, DOD has not communicated information to Congress about total fiscal exposures for future PFAS remediation. DOD emphasized that the scope of PFAS cleanup is unknown and until remedial investigations are completed, the department will not have data on future PFAS cleanup costs that are reasonably estimable, given the many unknowns faced by the department.

However, DOD is aware of billions of dollars of costs that it likely will incur as part of PFAS investigation and cleanup. DOD is also aware of many other significant remediation tasks whose costs it cannot precisely estimate at this time, which could total significantly more than the current estimated future costs. While estimates of future fiscal exposures are not required to be reported or disclosed in financial statements based on federal accounting standards, such estimates are relevant information for congressional oversight.

An essential element for providing Congress with a more comprehensive picture of fiscal exposures for PFAS investigation and cleanup is transparency through reporting and expanding the availability of information about agencies’ estimated remediation costs. By including in its semiannual cost report to Congress or other congressional reporting mechanism: (1) additional information regarding DOD’s potential total fiscal exposure related to PFAS investigation and cleanup, including cost estimates at BRAC and other sites expected to be funded by DOD appropriations, and (2) a detailed explanation and examples of how changing assumptions about key cost drivers may affect future cost estimates, DOD will provide Congress better visibility into the significant costs and efforts associated with the cleanup of PFAS. With this information, Congress would have greater visibility into the agency’s total fiscal exposure and be better equipped to make decisions regarding future funding for PFAS investigation and cleanup activities.

DOD Is Taking Steps to Address Challenges with Remediating PFAS

DOD faces several challenges in testing and remediating PFAS, including limited technology to address PFAS, the large number of installations identified to have PFAS contamination, evolving regulations and guidance pertaining to PFAS, changing laboratory methods to meet evolving screening levels, and the ubiquitous nature of PFAS.

|

Innovative Technologies to Test and Remediate Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances The Department of Defense (DOD) has invested significant funding into research and development efforts to create innovative ways to treat per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in all media. DOD is testing a new technology on a small scale to demonstrate the effectiveness. The Naval Air Station Oceana team has been working with the Environmental Security Technology Certification Program on “D-FAS Technology” also referred to as in situ foam fractionation technology. D-FAS can remove PFAS from water and soil by forcing the PFAS molecules to adhere to foam; the foam is then highly concentrated and easily removable. The PFAS-contaminated foam must be destroyed. The Environmental Security Technology Certification Program is also working on a PFAS destruction technology—hydrothermal alkaline treatment—which can be used to destroy the waste product from “D-FAS Technology.”

Source: GAO analysis of DOD information; DOD/SMSgt Paul Gorman (photo). | GAO‑25‑107401 |

Limited technology. According to agency documentation, there is no commercially available remediation technology that quickly removes 100 percent of PFAS contamination in all media. DOD officials told us that filtration is the primary option for removal of PFAS from water—also known as pump-and-treat. We have previously reported that as of July 2024, three drinking water treatment technologies—granular activated carbon, ion exchange resin, and high-pressure membranes—generally remove 99 percent or more of the six PFAS for which EPA has established maximum contaminant levels.[58] DOD officials explained that groundwater pump-and-treat requires contaminated water to be pumped out of the ground, run through a filter, and then inserted back underground or otherwise discharged. The cleanup process can take years and sometimes decades—5 to 10 decades—to complete. According to DOD officials, effective treatment options for contaminated media like soil and groundwater are in development, and at DOD installations, soil is often sent offsite for disposal through landfilling. To address this challenge, officials stated that DOD has invested significant funding (about $250 million through fiscal year 2023) into research and development efforts to create innovative ways to treat PFAS in all media. DOD’s environmental research programs—Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program and the Environmental Security Technology Certification Program—are funding over 200 projects related to the management of PFAS in the environment, according to DOD officials (see sidebar). Moreover, we have previously reported that while current and promising technologies and methods could improve the detection and treatment of PFAS, there are challenges associated with them, and we offered policy options to policymakers, which may include Congress, federal agencies, state and local governments, academia, and industry that could help mitigate the challenges.[59]

Large number of installations and base-wide investigations. According to DOD officials, the large number of installations nationwide that required PFAS investigations was overwhelming. In addition to the high number of installations, officials stated that the entire installation required investigations. DOD officials told us that they normally address chemical spills as they happen and conduct investigations of the specific spill area. According to DOD officials, there was very little historical documentation of PFAS releases, since there was no need or requirement to record such information. As a result, the entire installation had to be investigated to identify all potential releases. DOD officials said they had not conducted this type of investigation for any other specific contaminant in recent decades.

Moreover, according to officials, DOD must investigate if PFAS is migrating off-base and onto or under private property. DOD officials stated that to conduct sampling and cleanup activities on private property, DOD must receive signed permission from owners, and this process can slow down the investigation. Regulators are also involved in the process; for example, they must have an opportunity to comment at various points in the CERCLA cleanup process before DOD is able to move forward. According to officials, to address these challenges, DOD establishes schedules to include estimated start and end dates for each CERCLA phase and accounts for environmental variability in its assessment documents.

Changing laboratory methods and lab availability. According to DOD officials and agency documentation, EPA has released three laboratory methods for testing PFAS since DOD began officially investigating PFAS in 2017. Additionally, EPA’s screening levels for PFAS have been decreasing over the years, requiring more sensitive testing. PFAS are measured in “parts per trillion”, while most other contaminants are measured in “parts per billion” or “parts per million.” The most recent EPA regional screening levels from May 2024 for certain PFAS in tap water are in the “parts per quadrillion,” which is presently an undetectable level given the current testing technology.

While the methods and equipment used to test for PFAS are common across laboratories, according to DOD officials, equipment must be specifically dedicated to testing for PFAS to prevent cross-contamination. As we have previously reported, some laboratory equipment or sample containers can contain PFAS, which would interfere with an accurate result. This can present challenges for the laboratories conducting the PFAS testing. According to DOD guidance, samples containing PFAS must be tested in an accredited lab. There are specific criteria that a laboratory must meet to be accredited. According to DOD officials, there is a limited number of accredited labs. As a result, there can be long wait times to receive sample testing results, according to Army officials. To address these challenges, DOD officials told us the department has an accreditation process with clear steps for laboratories to take to become accredited. Additionally, DOD officials explained that the department plans to issue guidance on the updated regional screening levels in the first quarter of fiscal year 2025. We have previously reported on detection capabilities, including high-resolution mass spectrometry and total fluorine analysis.[60]

Evolving PFAS regional screening levels and regulations. According to DOD officials and agency documentation, since DOD began investigating PFAS in 2017, EPA has updated its regional screening levels for certain PFAS and added new PFAS compounds to the regional screening levels table on several occasions. When EPA has updated its regional screening levels for PFAS, DOD has generally released guidance addressing how the updated levels should be incorporated into DOD’s PFAS investigations. See table 5 for examples of changing levels for PFOS and PFOA established by EPA and DOD and how DOD has applied the levels to its cleanup activities.

Table 5: Select Levels for Certain Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Established by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of Defense (DOD) since 2016 and DOD’s Use of Those Level During PFAS Investigation and Cleanup

|

Select levels of certain PFAS in drinking water established by EPA and DOD since 2016a

|

Levels established for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water (in parts per trillion)b

|

Description of the levels and DOD’s application to PFAS cleanup activitiesb

|

||

|

Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)

|

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

|

|||

|

2016 lifetime drinking water health advisory levels |

70 Individually or summed |

Description: Nonenforceable and nonregulatory levels that provided information on health risks of identified but unregulated contaminants. DOD application: Used until 2024 as the threshold in drinking water above which DOD would perform an interim removal action during the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) process.c |

||

|

2019 interim recommendation for addressing groundwater |

40 |

40 |

Description: Interim recommended levels for federal cleanup activities to be used to determine if PFOA and/or PFOS was present at a site and may warrant further investigation. DOD application: Used until 2022 as the threshold in groundwater above which DOD would determine that further action was needed to investigate releases through the CERCLA cleanup process. |

|

|

2022 interim, updated lifetime drinking water health advisory levels |

0.02 |

0.004 |

Description: Updated, interim nonenforceable and nonregulatory levels for these PFAS, based on new science and considering lifetime exposure. DOD application: Not implemented in DOD’s PFAS cleanup activities due to lack of technology to detect PFOA or PFOS at these levels. |

|

|

2023 (May) tap water regional screening levels |

4 |

6 |

Description: Risk-based levels used by agencies to identify cleanup sites may need further investigation or action.e DOD application: Used as the threshold in tap water above which DOD will determine that further action is needed to investigate releases through the CERLCA cleanup process. |

|

|

2024 PFAS drinking water maximum contaminant levels |

4 |

4 |

Description: Enforceable maximum allowable levels of contaminants in drinking water provided by certain public water systems.d DOD application: Will be used in most cases as a final level to remediate contaminated drinking water, including groundwater and drinking water in private wells, through the CERCLA cleanup process. |

|

|

2024 (May) tap water regional Screening levels |

0.2 |

0.0027 |

Description: Risk-based levels used by agencies to identify cleanup sites that may need further investigation or action.e DOD application: Officials stated that DOD plans to issue guidance on the updated regional screening levels in the first quarter of fiscal year 2025. |

|

|

2024 three times EPA’s drinking water maximum contaminant levels |

12 |

12 |

Description: Levels established by DOD in updated guidance based on EPA’s PFAS Primary Drinking Water Regulation maximum contaminant levels. DOD application: Used since September 2024 as the threshold in drinking water above which DOD will perform an interim removal action during the CERCLA cleanup process.c |

|

Legend:

|

|

EPA-established levels |

|

|

DOD-established levels |

Source: GAO analysis of DOD and EPA guidance and regulations and GAO reports. | GAO‑25‑107401

aSome of the actions referenced in this column address PFAS other than PFOA and PFOS. Because PFOA and PFOS are some of the most common and studied PFAS, we include only the levels established for those PFAS here for illustrative purposes.

bDOD is following the CERCLA cleanup process to address releases of PFAS from DOD activities. For a description of the phases in a typical CERCLA cleanup, see figure 2 in this report (GAO‑25‑107401).

cAt any point during the CERCLA process, DOD may perform a removal action where there is a release or substantial threat of a release into the environment of any hazardous substance, or where there is a release or substantial threat of a release into the environment of any pollutant or contaminant which may present an imminent and substantial danger to the public health or welfare. Removal actions, such as providing bottled water, may not provide the protection or permanence of long-term remediation.

dThe maximum contaminant levels legally apply to certain public water systems—including those owned by DOD—which must comply with the established levels in drinking water by 2029. See PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulations, 89 Fed. Reg. 32532 (Apr. 26, 2024).

eDepicted levels represent default exposure assumptions for the residential scenario based on a Target Hazard Quotient of 0.1. Levels established for different scenarios are not depicted here and Target Hazard Quotients are not shown here.

The changing regional screening levels have resulted in additional costs and extended the timeline for identifying and remediating PFAS, according to military service officials. For example, when a screening level is updated, the contract may need to be updated as well. DOD officials reported that sometimes a change in scope requires an extension of the contract’s period of performance. EPA has also added additional PFAS to the regional screening levels table over the last several years, and military service officials said they had to redo work and update contracts to include the new PFAS compounds.

To address this challenge, service officials stated that they adjusted contract language or changed the type of contract they use to address PFAS. For example, Air Force officials told us that going forward in their contracts, they will not specifically list the regional screening levels in the performance work statement to allow for more flexibility. Additionally, Navy officials said that in some instances, they have opted to use cost contracts under which DOD reimburses the contractor for any work done, which can allow for flexibility if work needs to be changed or redone.

In addition to changing regional screening levels, changing regulations pertaining to PFAS have impacted DOD efforts to address PFAS releases. For example, now that EPA has established maximum contaminant levels for certain PFAS, DOD is planning to use those levels as final cleanup standards for drinking water in most CERCLA remedial actions addressing PFAS. DOD officials told us that their efforts may also be affected by other final and anticipated EPA regulatory actions addressing PFAS, including EPA’s April 2024 rule designating PFOS and PFOA as CERCLA hazardous substances. The designation itself is not expected to change how DOD applies the CERCLA process to address its releases of PFAS. However, it does open DOD up to potential liability for PFAS contamination that has migrated from DOD installations.

Assuming certain conditions are met, CERCLA can impose liability for cleanup costs on parties responsible in whole, or in part, for releases of hazardous substances into the environment. A party that has incurred cleanup costs or been held liable for such costs under CERCLA may seek to recover those costs from other potentially responsible parties, which could include DOD. Thus, DOD may be subject to lawsuits from parties seeking to recover costs associated with cleaning up PFAS contamination that may have resulted from DOD activities. For example, the State of New Mexico recently brought such claims against the Army and Air Force to recover costs associated with addressing PFAS contamination allegedly stemming from several DOD installations in the state.[61]

Moreover, EPA has proposed adding nine PFAS to the list of hazardous constituents under Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, as amended (RCRA).[62] In short, if this rule is finalized, it would likely give EPA and specific states clearer regulatory power over DOD’s PFAS investigation and cleanup efforts at certain sites with RCRA-permitted facilities.[63] To mitigate challenges with changing regulations, DOD officials told us they monitor changes in PFAS regulations and the department updates its policies and guidance based on regulatory developments.

Ubiquitous nature of PFAS. According to DOD officials, PFAS are uniquely difficult contaminants to clean up due to their ubiquitous, persistent nature, and numerous pathways for release. PFAS do not breakdown easily; they can persist in the environment for decades or longer. PFAS contamination can spread through the environment, and PFAS are found in many consumer products such as clothes, cosmetics, and furniture. Its common use has made the presence of PFAS ubiquitous across our environment. For example, PFAS have been detected in groundwater, soil, dust, wildlife, and rainwater across the United States and worldwide. Background concentrations refer to levels of PFAS found in the environment that are not directly caused by one specific release, but instead are the culmination of decades of prevalent use.

EPA has recognized that background concentration of hazardous substances, pollutants, and contaminants may affect the CERCLA cleanup process and has issued guidance for how background concentrations can be considered during the CERCLA process.[64] According to this guidance, final cleanup levels under CERCLA are generally not set below anthropogenic background concentrations. Therefore, cleanup activities conducted under CERCLA may not address background levels of PFAS. In these instances, according to EPA guidance, EPA may be able to help identify other programs or regulatory authorities that are able to address the sources of area-wide contamination that cannot be attributed to DOD activities.

Per DOD documentation, to address this challenge, DOD will work with EPA and state regulators, as appropriate, to evaluate background concentrations of PFAS during remedial investigations. This documentation states that, if background concentrations of PFAS are found to be above the PFAS maximum contaminant levels, DOD Components will work with regulators and the public to determine the appropriate final cleanup levels at that site.

Conclusions

DOD has spent billions since 2017 investigating and starting to clean up PFAS at its current and former installations. DOD has completed most preliminary assessments and site inspections at military installations identified with potential PFAS releases and has taken more than 100 interim removal actions to address immediate health concerns associated with PFAS exposure through drinking water or prevent mitigation of PFAS through groundwater, soil, or sediment. DOD has also made progress in the PFAS remedial investigations to determine the release source, exposure pathway, nature and extent of contamination, and level of risk to human health, with investigations underway at more than half of the installations identified to have had a release of PFAS. DOD also reports on the thoroughness and pace of its efforts to Congress and has taken steps to address significant challenges, including limited technology, scale of contamination, and changing regulations.

However, the department reports limited information about the full estimated future costs to be incurred by DOD for PFAS investigations and cleanup. Investigating and cleaning up PFAS are costly and time-intensive endeavors, and DOD’s estimated costs for completing its efforts have more than tripled since 2022. The department acknowledges that the estimated future costs are likely to increase significantly since full contamination is unknown until remedial investigations are completed. While DOD knows there will be future PFAS investigation and, likely, cleanup needed at 580 installations, DOD has not communicated information to Congress about total fiscal exposures for future PFAS remediation. By including additional information and a detailed explanation and examples of how changing assumptions about key cost drivers may affect future cost estimates, Congress would have greater visibility on the agency’s total fiscal exposure and be better equipped to make decisions regarding future funding for PFAS investigation and cleanup activities.

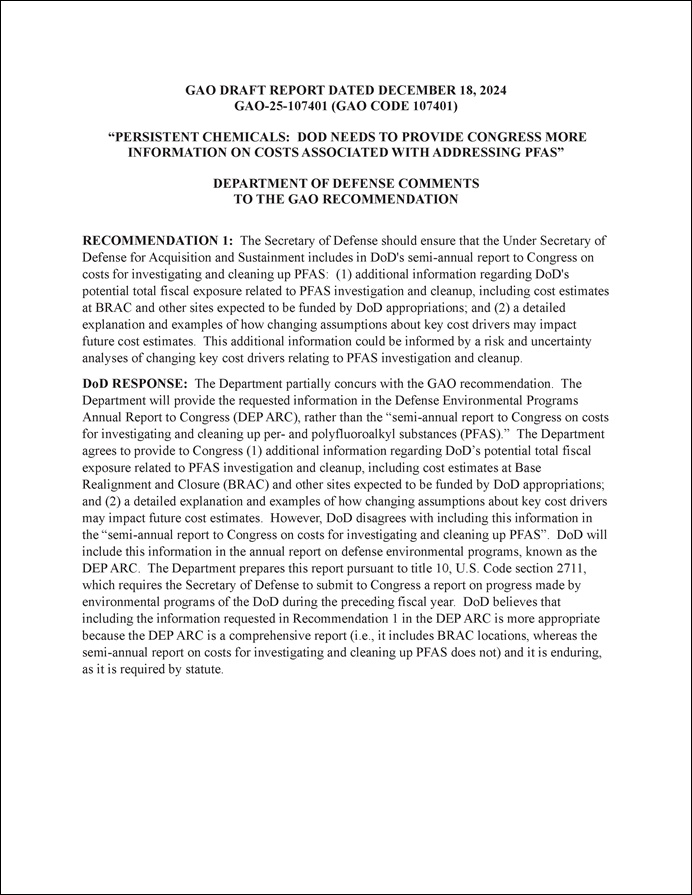

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Secretary of Defense should ensure that the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment includes in DOD’s semiannual report to Congress on costs for investigating and cleaning up PFAS or other congressional reporting mechanism: (1) additional information regarding DOD’s potential total fiscal exposure related to PFAS investigation and cleanup, including cost estimates at BRAC and other sites expected to be funded by DOD appropriations, and (2) a detailed explanation and examples of how changing assumptions about key cost drivers may affect future cost estimates. This additional information could be informed by a risk and uncertainty analyses of changing key cost drivers relating to PFAS investigation and cleanup. (Recommendation 1)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to DOD for review and comment. In written comments, reprinted in appendix VII, DOD partially concurred with the recommendation. DOD separately provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

DOD partially concurred with our recommendation. In its written comments, DOD stated that the department will provide the requested information in the Defense Environmental Programs Annual Report to Congress rather than the semi-annual report to Congress on costs for investigating and cleaning up per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. DOD believes that this report is more appropriate because it is a comprehensive report (i.e., it includes Base Realignment and Closure locations, whereas the semi-annual report on costs for investigating and cleaning up PFAS does not) and it is enduring, as it is required by statute.

We believe DOD’s proposed action would meet the intent of the recommendation aimed at providing Congress with greater visibility into additional billions of dollars needed for PFAS investigation and cleanup activities at DOD sites. Therefore, we modified the recommendation to state that DOD can provide the requested information in either the semi-annual report to Congress on costs for investigating and cleaning up per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or other congressional reporting mechanism.