SMALL BUSINESS RESEARCH PROGRAMS

Agencies Identified Foreign Risks, but Some Due Diligence Programs Lack Clear Procedures

Report to Congressional Committees

November 2024

GAO-25-107402

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO-25-107402. For more information, contact Candice N. Wright at (202) 512-6888 or wrightc@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107402, a report to congressional committees

November 2024

SMALL BUSINESS RESEARCH PROGRAMS

Agencies Identified Foreign Risks, but Some Due Diligence Programs Lack Clear Procedures

Why GAO Did This Study

U.S. intelligence agencies have warned that emerging technology companies in the U.S could be targeted by foreign actors seeking to obtain proprietary data, advance their nation’s economic and military capabilities, and threaten our national security. Small businesses seeking a SBIR or STTR award may face such risks. In fiscal year 2022, the 11 participating agencies collectively provided more than 6,500 SBIR and STTR awards valued at more than $4.4 billion to over 4,000 small businesses, according to the Small Business Administration.

The Extension Act includes a provision for GAO to issue a series of reports on the implementation of agencies’ due diligence programs to assess security risks presented by small businesses seeking a federally funded award. This report, the second in the series, examines (1) the types of foreign risks agencies identified and mitigated; and (2) agencies’ activities to refine their SBIR/STTR due diligence programs.

GAO reviewed 11 participating agencies’ documents and interviewed relevant officials on their program implementation.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations—one each to DHS, EPA, and NASA—to document agreed-upon procedures between the SBIR/STTR program office and counterintelligence office for supporting due diligence reviews. All three agencies concurred with our recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs were established to enable small businesses to engage in federally funded research. However, these programs face risks of foreign actors seeking to illicitly acquire federally funded research and technologies. In response to requirements in the SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 (Extension Act), the 11 federal agencies that participate in one or both programs implemented due diligence programs to assess the security risks posed by small business applicants.

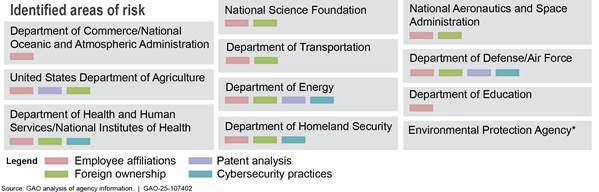

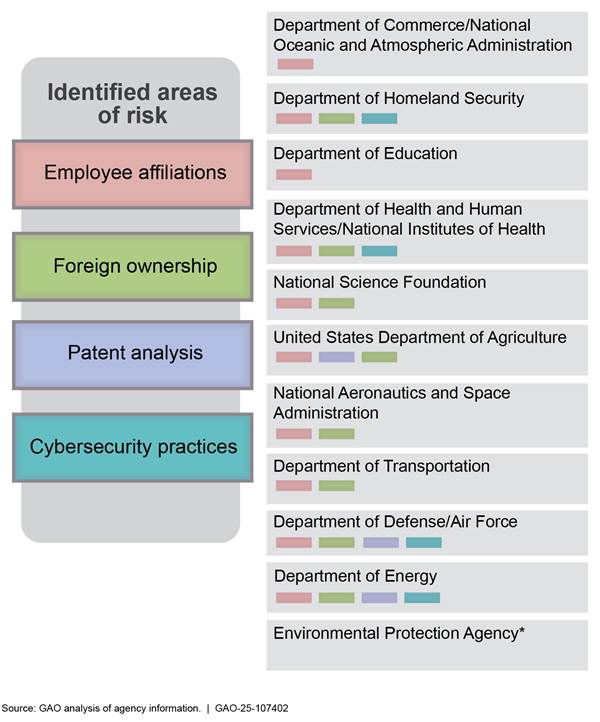

GAO found that most participating agencies identified risks in at least one of the four required assessment areas: cybersecurity practices, patents, foreign ownership, and employee affiliations. Agencies most commonly told GAO they had identified risks associated with employee affiliations and ownership in foreign countries of concern (see figure). For example, one agency found that although an applicant did not disclose foreign affiliations for key personnel on their disclosure form, the Principal Investigator had likely received funding from a Chinese malign talent recruitment program—which seek to recruit researchers, sometimes with malign intent. Therefore, the agency did not make an award to that small business.

*According

to Environmental Protection Agency officials, no risks have been identified to

date.

*According

to Environmental Protection Agency officials, no risks have been identified to

date.

GAO found that all participating agencies undertook activities to refine their due diligence programs in the first year of implementation. For example, some agencies acquired tools to aid in vetting applicants and conducted training for staff or applicants, and all used intra-agency support in conducting due diligence reviews. However, GAO found that three participating agencies—the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)—did not have documented processes for requesting analytical support and sharing information, including classified information, to support due diligence activities. For example, officials from EPA told GAO that there is no documented process for the program office to request counterintelligence analysis or for the counterintelligence office to communicate the resulting information to the program office. In interviews, all three agencies noted they plan to continue to use counterintelligence resources in their due diligence programs. Documenting processes and ensuring program officials have necessary information gathered and analyzed will be key as agencies continue to identify and mitigate risk in award decisions.

Abbreviations

Air Force Department of the Air Force

Commerce Department of Commerce

DHS Department of Homeland Security

DOD Department of Defense

DOE Department of Energy

DOT Department of Transportation

Education Department of Education

EPA Environmental Protection Agency

Extension Act SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022

FY fiscal year

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration

NIH National Institutes of Health

NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NSF National Science Foundation

NSPM-33 National Security Presidential Memorandum – 33

OCEA Air Force Office of Commercial and Economic Analysis

OSTP Office of Science and Technology Policy

R&D research and development

SBA Small Business Administration

SBIR Small Business Innovation Research

STTR Small Business Technology Transfer

USDA U.S. Department of Agriculture

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

November 21, 2024

Congressional Committees

The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs were established to enable small businesses to undertake and obtain the benefits of research and development (R&D). According to the Small Business Administration (SBA), in fiscal year (FY) 2022, collectively the 11 participating agencies provided more than 6,500 SBIR and STTR awards valued at more than $4.4 billion to over 4,000 small businesses. SBA is responsible for overseeing the SBIR and STTR programs, with six federal agencies participating in both programs and five others participating only in SBIR.[1] These 11 participating agencies provide support through awards (contracts, grants, or cooperative agreements) for projects on diverse topics ranging from information technology to defense.

A joint statement by several U.S. intelligence agencies in July 2024 warned that U.S. emerging technology companies could be targeted by foreign threat actors seeking to obtain proprietary data, advance their nations’ economic and military capabilities, and threaten U.S. national security. Small businesses seeking SBIR and STTR awards can expose U.S. R&D to foreign security risks, according to the National Science and Technology Council, as certain foreign governments are actively working to illicitly acquire the most advanced U.S. technologies.[2]

The SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 (Extension Act) defines a “foreign country of concern” as the People’s Republic of China, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Russian Federation, the Islamic Republic of Iran, or any other country determined to be a country of concern by the Secretary of State.[3] The Extension Act also requires SBIR and STTR participating agencies to establish due diligence programs to assess security concerns posed by small businesses applying for federally funded awards.[4]

We previously reported that all 11 participating agencies established their programs by the Extension Act’s June 2023 deadline and were planning to take various actions to assess risks and further refine their approaches.[5] According to SBA, the due diligence programs required by the Extension Act are intended to help agencies’ SBIR programs manage any potential foreign risks associated with small business awards in accordance with the established federal research security strategy detailed in the National Security Presidential Memorandum – 33 (NSPM-33).[6]

The Extension Act also includes provisions for GAO to issue a series of reports on the implementation and best practices of agencies’ due diligence programs to assess security risks presented by small businesses seeking a federally funded award. This report, the second in the series, examines (1) the types of foreign risks identified and mitigations used in SBIR/STTR programs and (2) agencies’ activities to refine their due diligence programs.

The scope of our work includes SBA and the 11 participating agencies. Five of these participating agencies—the Departments of Commerce, Defense (DOD), Energy (DOE), Health and Human Services (HHS), and Homeland Security (DHS)—have multiple components that issue SBIR and STTR awards. For those agencies, we selected the component that issues the highest volume of awards annually based on FY2022 award data, which are the most complete data available at the time of our review. The selected components include: the Air Force in DOD; National Institutes of Health (NIH) in HHS; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Commerce; Science and Technology Directorate in DHS; and Office of Science in DOE.

For the six remaining participating agencies—the Departments of Agriculture (USDA), Education, and Transportation (DOT), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and National Science Foundation (NSF)—we reviewed the one component that issues all of the SBIR or STTR awards for each agency.[7]

We also interviewed SBIR and STTR program officials at the selected participating agencies and collected and reviewed supporting documentation on guidance, policies, and due diligence processes. Additionally, we spoke with other relevant officials within the agencies involved in supporting the SBIR and STTR program offices with due diligence activities, such as the counterintelligence and inspector general offices. For more information on the objectives, scope, and methodology, see app. I.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

SBIR/STTR Program Overview

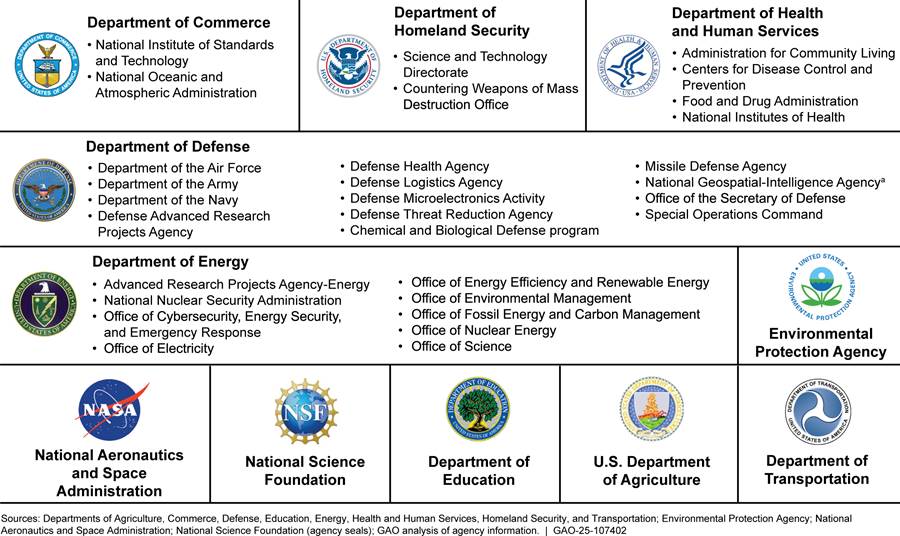

Pursuant to the Small Business Act, federal agencies with an extramural research or R&D budget greater than $100 million are required to participate in the SBIR program, and agencies with R&D obligations greater than $1 billion are required to participate in the STTR program.[8] Through the competitive SBIR/STTR programs, awards are issued to small businesses to explore their technological potential and provide incentives for commercialization. See figure 1 for a list of the 11 participating agencies and their components.

Figure 1: Eleven Agencies Participating in the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs

Note: Six agencies currently participate in STTR: the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, and Health and Human Services; the National Aeronautics and Space Administration; and the National Science Foundation.

aThe National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s SBIR/STTR program is operated by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, according to an official with that office. The figure shows the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency as a distinct component because the agency voluntarily participates in the SBIR/STTR programs.

According to SBA’s SBIR/STTR Policy Directive, at least once per year each participating agency must issue a solicitation requesting proposals, which can cover a variety of topics.[9] Each participating agency must (1) review the proposals it receives; (2) determine which small businesses should receive awards; (3) notify pending awardees within their required time frame; and (4) negotiate contracts, grants, or cooperative agreements to issue the awards within recommended time frames.

Due Diligence for Foreign Risk in SBIR/STTR Programs

The Extension Act requires each federal agency with an SBIR or STTR program to develop and implement a due diligence program by June 27, 2023, to assess security risks posed by small businesses seeking federally funded awards.[10] The Extension Act’s due diligence requirements expand on NSPM-33 by mandating all SBIR/STTR participating agencies use a risk-based approach, as appropriate, to assess foreign risks associated with small businesses seeking an award in four areas:

· Cybersecurity practices. Despite the increase in cybercrime awareness, many small businesses remain vulnerable due to a lack of resources and knowledge, according to SBA. Incorporating cybersecurity practices can help protect information related to federally funded research.[11]

· Patents. SBIR/STTR awards are potentially subject to technology and intellectual property risks that may be identified through patent analysis. Agencies can use data from patent applications and issued patents to uncover potential relationships between entities or individuals and foreign actors.

· Employee affiliations. Employees who perform R&D using an SBIR/STTR award may be subject to exploitation attempts to obtain sensitive research information. Employee analysis will assess potential risks of employee affiliations and financial obligations and ties with foreign countries. Agencies may focus particularly on those employees who can significantly influence the direction of the research, the acquisition of data, or the method and analysis of the research.

· Foreign ownership. Consistent with federal regulations and to be eligible for SBIR/STTR awards, businesses must meet specific eligibility requirements.[12] For example, an SBIR/STTR awardee must generally be at least 50 percent directly owned and controlled by U.S. citizens or permanent residents. Due diligence programs will assess a small business’s financial ties and obligations to a foreign country, person, or entity.

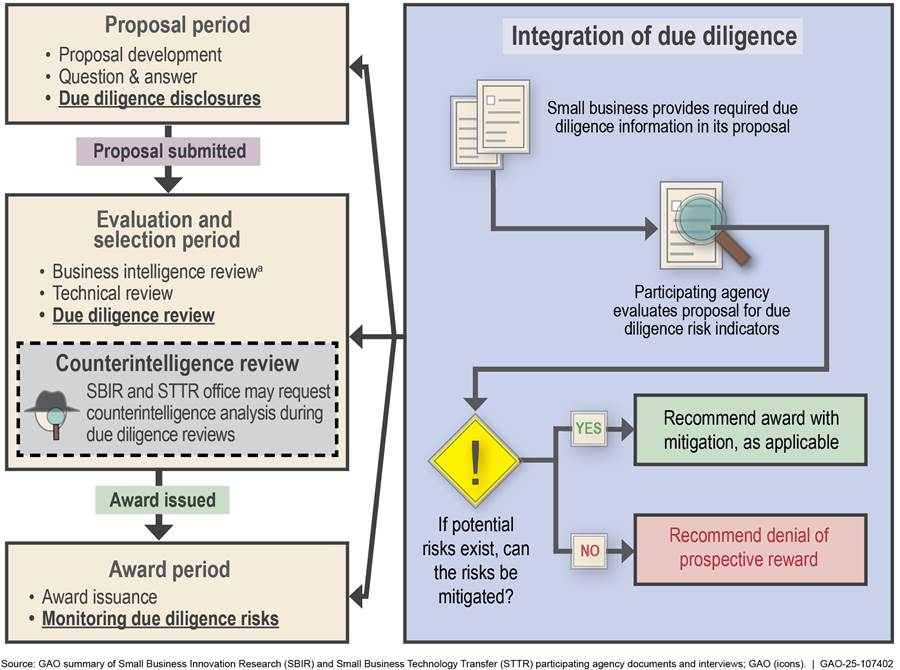

Although each agency’s due diligence programs may vary in procedure, a general three-step process is used to navigate the proposal, evaluation and selection, and award periods. All selected participating agencies require applicants to complete the standardized disclosures (issued by the SBA in May 2023) during the proposal period, except EPA, NSF, and NIH which require the disclosures only from applicants being considered for awards.[13] During the evaluation and selection period, agencies review applicants’ disclosures and conduct technical reviews of the proposals. Agencies may decline to make an award or may apply any necessary risk mitigation before issuing an award. Agency officials also stated that during the award period, they continue to monitor the risks identified earlier (such as through required reports) and conduct additional due diligence reviews as needed to address any new risks (such as a change in key personnel) discovered after the award. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of this process.

Figure 2: Generalized Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Award Process Flow with Due Diligence Activities

aAgencies conduct business intelligence reviews to assess a small business’s ability to collect, analyze, and transform data to improve decision-making and optimize the business.

After the Extension Act was enacted in September 2022, the 11 participating agencies established and implemented due diligence programs using various approaches, and all met the June 2023 implementation deadline. As of August 2024, of the 11 participating agencies, seven (Air Force, DHS, DOE, Education, EPA, NASA, and NOAA) have completed a full award issuance cycle using the new due diligence requirements while the remaining four (DOT, NIH, NSF, and USDA) are in process.[14]

Agencies Have Begun to Identify and Mitigate Potential Foreign Risks

All the agencies we reviewed except EPA reported that they identified potential foreign risks for SBIR/STTR applicants through the due diligence programs they established in 2023. Agencies identified risks in one or more of the four areas noted in the Extension Act: employee affiliations, foreign ownership, patent analysis, and cybersecurity. Agencies mitigated these risks in various ways, including by preventing applications from moving forward in the award process or by requiring changes to the award application or contract, according to agency officials.

Of the four risk categories identified in the Extension Act, selected agencies most commonly told us they had identified risks associated with employee affiliations and ownership in foreign countries of concern. See figure 3 below for risk areas identified by participating agencies as of August 2024.

Figure 3: Risk Areas Identified by Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Participating Agencies and Selected Components, as of August 2024

*According to Environmental Protection Agency officials, no risks have been identified to date.

Note: In addition to the four risk areas specified in the Extension Act, two agencies (Education and NASA) told us they identified risks associated with applicants’ supply chains.

In our review, we found the level of the risk may play a role in how the agency responds to it. For example, an applicant may disclose an employee affiliation with a foreign country. If the country is not a country of concern, the agency may consider the affiliation to present a low risk. In one instance, an applicant disclosed to one participating agency (DOT) that it had a subsidiary in Canada. Because Canada is not a country of concern, the agency did not remove the application from consideration for an award. If an applicant discloses that an employee has close affiliations in a country of concern or with foreign entities or organizations that may compromise the integrity of R&D activities, the agency may consider the risk to be of greater magnitude. For example, USDA denied two awards based on information it discovered through its due diligence process. In one case, one of the key personnel on the application was affiliated with a university in China. In another case, the applicant had investors located in China.

When an agency identifies potential risk for an applicant, if it considers those risks low enough or sees a significant benefit in moving forward with an award, the agency may advance an application in the award process. If it makes an award to the applicant, the agency may add requirements to the award to mitigate the potential risk. For example, a contract could require more frequent or detailed monitoring of the awardee. When an agency determines that an applicant presents an unacceptable level of risk of foreign influence, the agency will remove the applicant from consideration for an award. Table 1 provides illustrative examples of risks that selected agencies have identified, along with steps, if any, taken to mitigate each risk.

|

Agency |

Risk Area |

Risk |

Mitigation |

|

Department of Commerce: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) |

Employee affiliation |

NOAA found that several of the personnel on an application had publications with co-authors in foreign countries. |

NOAA made an award to the applicant without requiring mitigation measures because the foreign co-authors were not listed as contributors on the application.a |

|

Department of Homeland Security (DHS) |

Cybersecurity |

DHS found that an applicant with offices overseas—including in Hong Kong—had major deficiencies in certain cybersecurity areas. |

DHS did not make an award to the applicant. |

|

Defense of Defense: Air Force |

Patent analysis |

The Air Force found that an applicant had patents filed with a Chinese government-affiliated university and had failed to disclose significant funding received from a Chinese venture capital firm. |

The Air Force did not make an award to the applicant. |

|

Department of Energy (DOE) |

Cybersecurity |

An applicant disclosed its cybersecurity practices to DOE, and DOE determined those practices posed a high risk of intellectual property theft. |

DOE required that the applicant mitigate the risk by implementing selected cybersecurity practices during the initial period of the award. |

|

Department of Transportation (DOT) |

Employee affiliation |

An applicant disclosed to DOT that it was funding the work of a graduate student who was a foreign national. |

DOT made an award to the applicant because the graduate student was not affiliated with a foreign country of concern. |

|

Department of Education (Education) |

Employee affiliation |

Education found that one of the personnel on an award application was educated in a foreign country of concern. |

Education made an award to the applicant without requiring mitigation measures since the individual had no affiliations with a foreign country of concern within the last 10 years. |

|

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) |

N/A—no risks identified to date. |

N/A—no risks identified to date. |

N/A—no risks identified to date. |

|

Department of Health and Human Services: |

Employee affiliation |

NIH found that although an applicant did not disclose foreign affiliations for key personnel on their disclosure form, the Principal Investigator had likely received funding from a Chinese malign talent recruitment program.b |

NIH did not make an award to the applicant. |

|

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) |

Foreign ownership |

An applicant disclosed to NASA that it had a small equity investment from a company that was partly owned by a Chinese government-owned aerospace and defense corporation. |

NASA determined that it could mitigate the risk with increased monitoring and made an award to the applicant. |

|

National Science Foundation (NSF) |

Foreign ownership |

NSF found that the Principal Investigator on an application had raised significant investment from a firm located in a foreign country of concern (China). NSF also found that the business had generated revenue through a Chinese subsidiary in recent years. |

NSF did not make an award to the applicant, although foreign ownership was not the only factor in the agency’s decision. |

|

Department of Agriculture (USDA) |

Employee affiliation |

USDA found that as recently as 2020, one of the key personnel listed on an application had failed to disclose foreign relationships and activities. |

USDA notified the applicant of the failure to disclose. Upon notification, the applicant took corrective action and removed the key personnel from the project. USDA issued the award following this corrective action. |

Source: GAO analysis of interview responses and documentation provided by selected Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) participating agencies. | GAO‑24‑107402

aAccording to NOAA officials, the project also did not meet the award prohibition criteria of 15 U.S.C. 638(g)(15).

bForeign talent recruitment programs seek to recruit researchers, sometimes with malign intent.

Participating agencies we reviewed said they may view an applicant’s failure to disclose foreign ownership or affiliations as increasing the level of associated risk, even if they would consider the undisclosed risk itself to be low. For example, DHS officials told us they had denied an award because of undisclosed foreign affiliations. The project involved work that was intended to be shared internationally, so the applicant’s foreign ties were unlikely to pose an actual risk. However, DHS considered the applicant’s failure to disclose required information sufficient reason to deny the award.

Participating agencies more often told us about denying awards with identified risks than about making such awards with mitigation measures. For example, Air Force officials told us that they typically deny awards and remove such applicants from consideration rather than mitigate risks, in part because implementing mitigation measures would involve a large investment of staff time. Air Force officials explained that personnel could be needed to oversee mitigation measures such as tracking reporting requirements, conducting site visits, performing audits, and, when appropriate, documenting non-compliance. These officials also told us that mitigation measures may not be effective, and, if they fail, it could compromise large amounts of protected information.

Agencies Implemented Several Refinement Activities but Some Did Not Have Processes to Handle Sensitive Information

All 11 participating agencies and selected components we reviewed undertook activities to refine their due diligence programs in the first year of implementation, and some identified refinement activities they plan to address in future award cycles. Some agencies did not have documented processes on how they incorporate or manage intra-agency counterintelligence analytical support into their due diligence programs.

Agencies Have Taken Initial Steps to Refine Due Diligence Programs

As of August 2024, the participating agencies we reviewed described activities to refine their due diligence programs based on feedback from early implementation. We reported in November 2023 that these agencies had plans to further refine their due diligence programs in the following six areas:[15]

· Hire additional staff;

· Support additional training;

· Acquire due diligence vetting tools;

· Conduct workload assessments;

· Address timeliness concerns; and

· Leverage intra-agency assistance in due diligence evaluations.

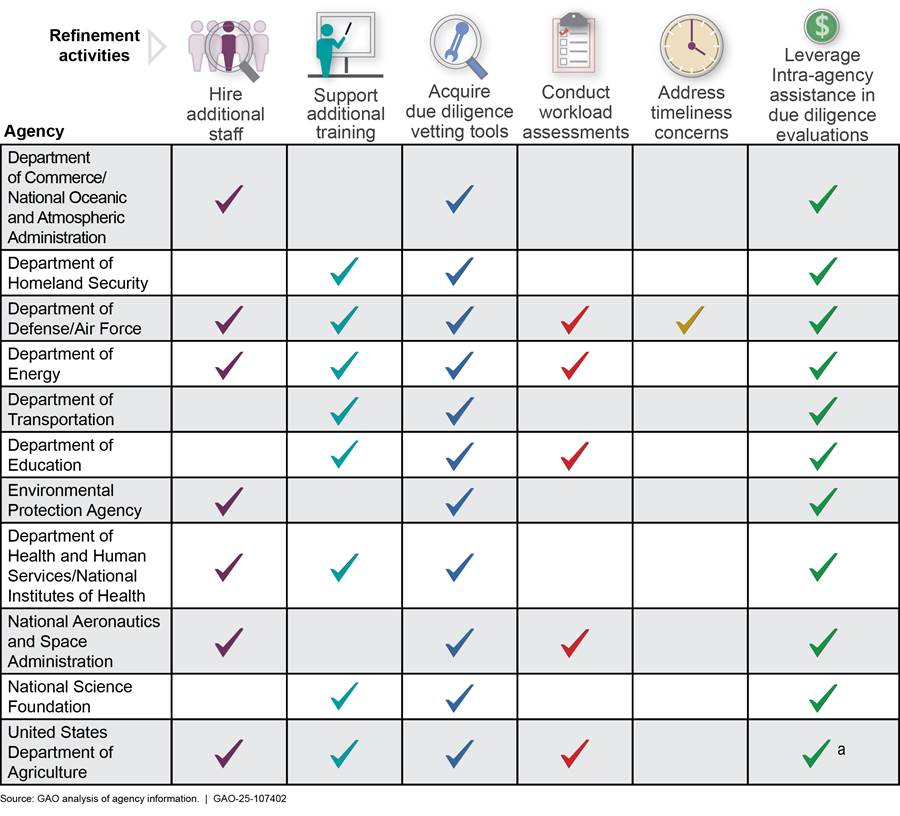

As shown in figure 4, all the agencies acquired vetting tools and leveraged intra-agency assistance—such as counterintelligence analysis. Figure 4 illustrates various agency actions and processes under each of the six refinement areas.

Figure 4: Activities Implemented by Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Participating Agencies and Selected Components to Refine Due Diligence Programs

aNote: USDA officials told us they initially used intra-agency resources in their due diligence review but found the information did not impact decision-making and have discontinued use of the resource.

Hiring additional staff. Some participating agencies and selected components—Air Force, DOE, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA, and USDA—hired staff within their SBIR/STTR program office or in other offices that provide support to the due diligence processes.[16] According to officials, such staff can help agencies build capacity to implement the new due diligence requirements and provide specific expertise, such as in cybersecurity or counterintelligence.

Seven participating agencies—Air Force, DOE, EPA, NASA, NIH, NOAA, and USDA—hired staff within their SBIR/STTR program offices. Some of these staff were hired specifically to support the new due diligence requirements. For example, NOAA hired a due diligence specialist to support its reviews, and NIH hired multiple positions, including a program coordinator, to help meet the new due diligence requirements. EPA officials stated that newly hired personnel will also provide support to the SBIR due diligence process, among other duties. Similarly, USDA hired a SBIR Program Analyst to analyze data to assess program goals and outcomes, maintain compliance with legislative requirements, and recommend improvements to increase effectiveness of its foreign influence due diligence program. NASA used Skillbridge interns—a DOD program that provides transitioning military members with non-military work experience—to support the additional workload required by the due diligence reviews. Air Force used personnel from another program to provide additional support during high-demand situations.

Two participating agencies—DOE and NOAA—hired or are in the process of hiring staff for offices that provide support to due diligence processes. For example, DOE hired three counterintelligence specialists for its Office of Intelligence and Counterintelligence specifically to support the SBIR/STTR due diligence program.[17] NOAA officials told us they are in the process of hiring staff for their Research Security Office to support due diligence reviews, particularly for cybersecurity, alongside other job responsibilities.

Acquiring due diligence vetting tools. All the participating agencies and selected components we reviewed stated they have obtained or plan to obtain tools for use in due diligence reviews. Tools include federal government data sources, commercial off-the-shelf business intelligence tools, or agency-developed software programs.

USDA officials told us they use federal government data sources to verify information provided in applicants’ due diligence disclosure forms. For example, USDA said they use the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office patent database—which provides information on issued and proposed patents—and the Department of the Treasury’s Do Not Pay System—which, among other information, includes the list of individuals and companies owned or controlled by targeted countries, as well as other entities, such as terrorists and narcotics traffickers designated under programs that are not country specific.

All the participating agencies told us they are exploring, have previously acquired, or recently acquired commercial off-the-shelf business intelligence tools for conducting due diligence reviews. Commercial tools may include a variety of capabilities, including access to datasets with company financial history and investor information, or artificial intelligence-created analytic dashboards that provide real-time risk ratings across multiple categories, such as financial and foreign influence.

Three participating agencies—Air Force, NASA, and NSF—are in the process of developing other tools, either to automate the processing of due diligence disclosure forms or support the vetting of applicants and identify associated risks. For example, NASA is developing tools to automate aspects of the due diligence review process to allow for the review of all proposals rather than just those most likely to receive awards. According to NASA officials, this automation will allow for more in-depth analysis of the proposals and the ability to make connections. Air Force’s Office of Commercial and Economic Analysis (OCEA) has contracted with a commercial provider to tailor its business intelligence platform to support federal agencies’ due diligence vetting using unclassified information. For example, the tool seeks to corroborate that the personnel listed on a SBIR or STTR application are indeed associated with the company in its public facing information. Furthermore, OCEA officials stated that information provided back to the SBIR program office would allow for monitoring changes over the course of the award, such as changes in the company profile. Air Force has made this tool available for a fee to other agencies. Officials from other agencies, including DOE, DHS, Education, EPA, NASA, NOAA, and USDA, told us they are exploring this tool for their SBIR/STTR due diligence reviews.

Supporting additional training. Some participating agencies—Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, NIH, NSF, and USDA—conducted training for either staff or applicants, such as creating new or updating existing training or guidance, facilitating staff briefings, or mandating training for applicants. Five agencies—Air Force, DHS, NIH, NSF, and USDA—provided guidance and training to internal teams to educate them on the new due diligence requirements and review processes. For example, NIH provided written guidance, targeted training, and presentations to program and grants management staff on the new due diligence requirements to explain how NIH will implement them. USDA SBIR program officials told us they trained all employees on the new legislative requirements as well as the new tools USDA is using or plans to use to perform due diligence reviews. Additionally, NSF officials stated they provided updates for program staff on the new due diligence requirements.

In some cases, agencies also provided cybersecurity training to agency staff or SBIR/STTR applicants. DHS officials stated this training may inform small businesses that are vulnerable to cybersecurity threats and lack necessary resources to meet government standards. Six agencies—Air Force, DHS, DOE, DOT, Education, and NSF—incorporated training programs or guidance to educate applicants of potential threats or educate staff on best practices for evaluating applicants. For example, to provide cybersecurity resources for small business applicants and awardees, DHS officials told us the SBIR program office collaborates with the DHS Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and DOT shares materials from this agency on its website. In addition, DOT’s Office of Sector Cyber Coordination has developed a curriculum to aid awardees in understanding cybersecurity requirements and resources. DOE hired a cybersecurity contractor to develop training for SBIR and STTR applicants beginning in 2024. Education requires all awardees to complete a cybersecurity basics course, and awardees must also designate a security liaison who is required to complete two additional training sessions on cybersecurity.

Conducting workload assessments. Five participating agencies—Air Force, DOE, Education, NASA, and USDA—stated that they have conducted workload assessments including informal assessments, real-time analysis of metrics, or in response to specific due diligence requirements. For example, Air Force officials told us they conduct real-time workload analyses which include forecasted scheduling, volume, and deadline achievement rates for award proposals. According to these officials, these metrics resulted in changes to both operations and procedures for their due diligence activities. Education officials told us they conducted an informal workload assessment after completing their FY 2023 due diligence process. NASA officials told us they reorganized their SBIR program as a result of a new SBIR/STTR strategy established in 2021 and created a new Business Intelligence Unit, which they said was a natural fit for the due diligence program established in June 2023. These officials explained that the agency continues to assess the workload of those in the new unit as due diligence activities are not their sole responsibility.

Addressing Timeliness Concerns. One agency we reviewed—Air Force—told us that it has addressed timeliness concerns to mitigate the impact of due diligence on award timeliness. We have previously reported on agencies’ varied success in meeting award timeliness parameters.[18] In November 2023, we also reported that agencies plan to assess the effects of the new due diligence reviews on timeliness before applying mitigation measures.[19]

In this review, Air Force said that in response to delays experienced in the first year of implementation, it conducted an analysis to identify bottlenecks and adjusted its future solicitation schedule to reduce the risk of delays. In addition, to address timeliness of awards in future cycles, NASA said that it is developing an automated process to conduct initial screening of the due diligence disclosure forms. The agency intends for this automation to help meet timeliness requirements in future proposal cycles by allowing it to focus on applicants that raise an initial concern and need additional screening or coordination with other offices. All the agencies said that the requirement to perform due diligence reviews has made it more difficult to meet required timelines to notify applicants of award status, with some stating that it imposes additional work on program staff or may require coordination between multiple offices within the agency.

Three agencies—DOE, Education, and NOAA—told us that they have experienced delays or impacts to timeliness in the first year of implementing the new due diligence requirements.[20] These agencies requested and received waivers from SBA to extend the award notification date because they were unable to meet the 90-day notification period due, at least in part, to implementing their due diligence programs, according to SBA officials. Education officials said that refinements to the agency’s due diligence program allowed it to meet its FY 2024 notification deadlines.

Most Agencies Leverage Intra-Agency Resources, but Some Did Not Have Documented Processes to Handle Sensitive Information

Intra-agency assistance in due diligence evaluations. All the participating agencies we reviewed leveraged other agency resources or offices within the agency to support the due diligence process. For example, Education’s SBIR program office receives due diligence support from both its Information Assurance Services branch (under the Office of the Chief Information Officer) as well as from its National Library of Education. These entities aid the program office in determining whether a potential small business applicant has financial ties and obligations to a foreign country, person, or entity. Additionally, some participating agencies—DOT, Education, EPA, NASA, and NSF—also noted receiving support from their respective Offices of the Inspector General (OIG) with vetting small business applicants or refining their due diligence programs. For example, EPA received guidance from its OIG on process or investigations. NASA and DOT OIGs conduct due diligence vetting of key personnel listed in SBIR proposals, according to OIG officials.

In November 2023, we reported that some of these agencies may also use counterintelligence or security offices to assist in information gathering and analysis.[21] We also reported that although counterintelligence was not specifically identified as a requirement in the Extension Act, such activities may help agencies to detect, identify, assess, and counter damaging efforts by foreign entities.[22] For example, agencies may perform due diligence evaluations that include counterintelligence reviews as a part of their risk-based approaches.

|

Counterintelligence Support in Foreign Risk Management Counterintelligence offices have specialized expertise and access to information which may allow them to provide unique support to Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs’ due diligence reviews. Counterintelligence personnel can access classified information and perform analysis that could help program officials assess the potential risk posed by an applicant. In addition to the classified information, some counterintelligence offices incorporate open-source information into their analysis and may have access to analytical tools that may not be available in the SBIR/STTR program offices. Counterintelligence offices may also provide support to due diligence reviews for other non-SBIR/STTR award proposals. Source: GAO analysis of agency information. | GAO‑25‑107402 |

Currently, six participating agencies—Air Force, DHS, DOE, EPA, NASA, and NIH—told us they are using intra-agency resources to perform counterintelligence analysis, which includes vetting applicants using classified sources and unclassified or open-source information (see sidebar). The remaining five agencies are not using counterintelligence analysis in their due diligence reviews because they either lack the resources to conduct such reviews; focus primarily on unclassified or open-source information; or have not needed counterintelligence support for decision-making purposes.

The participating agencies using counterintelligence resources explained that especially when foreign affiliations such as a foreign country of concern are identified, they may work with their counterintelligence offices to gather additional information on such applicants. We spoke to some of these counterintelligence offices about their role in the due diligence process. These officials told us they search both unclassified and classified databases, provide relevant information on foreign personnel and potential company foreign ties, and, in some cases, may make recommendations to the SBIR program offices on whether to fund the award based on the risks identified.

We found three participating agencies—Air Force, NIH, and DOE—have documented processes to use information gathered and analyzed by their counterintelligence offices. For example, the Air Force Office of Special Investigations provided documentation on its role in the Air Force’s due diligence process. HHS provided a documented memorandum of understanding between its Office of National Security and NIH on support to the NIH SBIR/STTR due diligence process. Specifically, the memorandum describes how they will share, record, and disseminate information between each other, including roles and responsibilities. DOE also provided a copy of its documented process for its counterintelligence review of SBIR/STTR awards such as identifying whether a foreign nexus exists (e.g., training, education, or foreign ownership in countries of concern).[23]

The remaining three agencies that are using counterintelligence support in their SBIR/STTR due diligence—EPA, DHS, and NASA—do not have documented procedures for requesting analytical support and sharing information, which may include classified information, gathered and analyzed by counterintelligence. For example, EPA’s SBIR program office works with its Office of National Security, which may perform counterintelligence analysis on some applicants using classified sources. However, there is no documented process for the program office to request counterintelligence analysis or for the Office of National Security to communicate the resulting information to the program office. EPA’s SBIR program office noted that the agency’s due diligence program is early in its implementation and that they had not documented these activities.

Similarly, DHS’s SBIR program office does not have a documented process for its collaboration with its counterintelligence office for conducting due diligence analysis. We also found some disagreement between the offices on the clearance levels (i.e., secret versus top secret) for staff using the classified information gathered and analyzed by counterintelligence. According to the counterintelligence office, the program office should have personnel with top secret clearances to use the information gathered and analyzed by them. The program office, however, stated that to date there has not been a need for that clearance level in its SBIR due diligence reviews. Regardless, DHS’s SBIR program office noted that they had not documented any processes for collaboration with its counterintelligence offices as it was still early in implementing the due diligence activities.

NASA officials also told us that the SBIR/STTR program office works with their Office of General Counsel to determine whether counterintelligence analysis on some applicants is warranted and to engage the agency’s Office of Protective Services, Counterintelligence/Counterterrorism Division to perform such analysis. NASA officials described a process for involving counterintelligence-developed information at certain pre-award review and decision-making panels. However, this process is not documented. NASA’s officials noted they preferred not to document the specific details on counterintelligence office’s process for security reasons. But in an interview, officials from both offices agreed that some documentation was needed on how such counterintelligence analysis may be requested or how the results are communicated with the program office. NASA program officials said that several people in the SBIR/STTR program’s leadership have the necessary security clearance to view any classified information the counterintelligence office may find.

All three agencies noted they plan to continue to use counterintelligence resources in their due diligence programs. Leading practices on collaboration that we have identified in prior work state that written guidance and agreements to establish the “rules of the road” for the collaboration can promote information sharing and help to ensure participants agree.[24] Such documentation can provide a framework for how a collaborative effort operates and how decisions will be made. Additionally, the Standards for Internal Control states that management should document policies and procedures to ensure a common understanding of roles, responsibilities, and processes and mitigate the risk of having key institutional knowledge that is limited to a few personnel.[25] Developing such documentation can better position EPA, DHS, and NASA to more effectively implement their SBIR/STTR due diligence activities and help ensure all relevant stakeholders have the necessary and critical information to identify possible risks when making award decisions.

Conclusions

Small businesses can expose U.S. R&D to foreign security risks. Certain foreign governments are actively working to illicitly acquire the most advanced U.S. technologies. Participating agencies have taken steps to identify and mitigate possible foreign risks through their implementation of the SBIR/STTR due diligence programs and have taken steps to refine activities. However, we found that three participating agencies—DHS, EPA, and NASA—do not have documented processes for requesting counterintelligence support and information sharing, including classified information, to support due diligence activities.

These three participating agencies noted that the lack of documentation is partially because the due diligence programs are early in their implementation stages or for security concerns. But these agencies also noted that they plan to continue to use such resources in future due diligence reviews. Leading practices on collaboration and internal control standards note that written guidance and agreements can provide a framework for how decisions will be made and ensure a common understanding of roles, responsibilities, and processes.

Documenting processes will be key as agencies seek to ensure program officials have necessary information to identify and mitigate risk in award decisions. Furthermore, documenting such processes would also help ensure that procedures remain consistent and that key resources remain available to the SBIR/STTR program officials as they mitigate the risk of federally funded research diverting to illicit foreign actors.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making three recommendations—one to EPA, one to DHS, and one to NASA. Specifically:

The Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency should ensure that the SBIR/STTR program office and the Office of National Security develop and document agreed-upon procedures for requesting analytical support and sharing information—including classified information, as applicable—to support due diligence reviews. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Homeland Security should ensure that the SBIR/STTR program office, the Office of the Chief Security Officer, and the Office of Intelligence and Analysis develop and document agreed-upon procedures for requesting analytical support and sharing information—including classified information, as applicable—to support due diligence reviews. (Recommendation 2)

The Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration should ensure that the SBIR/STTR program office and the Office of Protective Services, Counterintelligence/Counterterrorism Division develop and document agreed-upon procedures for requesting analytical support and sharing information—including classified information, as applicable—to support due diligence reviews. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to Commerce, DHS, DOD, DOE, DOT, Education, EPA, HHS, NASA, NSF, SBA, and USDA for review and comment. EPA, DHS, and NASA concurred with our recommendations, and their written responses are reprinted in appendices III through V. DHS, DOE, Education, NIH, NSF, and USDA provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. Commerce, DOD, DOT, and SBA told us they had no comments on this report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees; the Secretaries of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, and Transportation; the Administrators of the SBA, EPA, and NASA; the Director of the NSF; and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at (202) 512-6888 or wrightc@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix VI.

Candice N. Wright

Director, Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics

List of Committees

The Honorable Jack Reed

Chairman

The Honorable Roger Wicker

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

United States Senate

The Honorable Jeanne Shaheen

Chair

The Honorable Joni Ernst

Ranking Member

Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship

United States Senate

The Honorable Mike Rogers

Chairman

The Honorable Adam Smith

Ranking Member

Committee on Armed Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Frank D. Lucas

Chairman

The Honorable Zoe Lofgren

Ranking Member

Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

House of Representatives

The Honorable Roger Williams

Chairman

The Honorable Nydia M. Velázquez

Ranking Member

Committee on Small Business

House of Representatives

The SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) and STTR (Small Business Technology Transfer) Extension Act of 2022 (Extension Act) includes provisions for GAO to issue a series of reports on the implementation and best practices of agencies’ due diligence programs to assess security risks presented by small businesses seeking a federally funded award.[26]

This report, the second in the series, examines (1) the types of foreign risks identified and mitigations used in SBIR/STTR programs; and (2) agencies’ activities to refine their due diligence programs based on their early experiences implementing them.

The scope of work includes the Small Business Administration (SBA) and the 11 participating agencies.[27] For the five agencies with more than one component that issues awards, we selected the component that issues the highest volume of awards annually based on fiscal year (FY) 2022 award data, which are the most complete data available at the time of our review. Specifically, we focused on the Department of the Air Force in the Department of Defense (DOD), the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the Department of Commerce (Commerce). We refer to these three component entities throughout the report inclusively in our “participating agencies” (i.e., Air Force, NIH, and NOAA).

In addition, the Science and Technology Directorate in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Office of Science in the Department of Energy (DOE) both issue the most SBIR/STTR awards for their agencies and coordinate these programs on behalf of other components in their agencies, and, therefore, we refer to the parent agency (DHS and DOE, respectively) in our collective “participating agencies.”[28]

The remaining six participating agencies issue SBIR and STTR awards through a single component, and for these six we refer to the entire agency as the participating agency (e.g., USDA). In addition, to characterize agency responses to our inquiry, we use “some” to refer to 4 to 9 agencies and “most” to refer to 10 agency responses.

To address our first objective, we collected and reviewed documentation, interviewed officials, and collected written questionnaire responses from the 11 participating agencies on risks they identified in the early implementation of their due diligence programs and how they mitigated those risks. Specifically, we created semi-structured interview questions on the types of risks agencies identified and whether those fell into the four issue areas described in the Extension Act (employee affiliations, foreign ownership, patents, and cybersecurity) or in other areas.

We received and analyzed responses to that questionnaire from all 11 agencies. We also interviewed officials from each agency’s SBIR/STTR program office, along with, when applicable, other offices that support agencies’ due diligence processes. We requested illustrative examples from the agencies for each of the types of risks they identified and any supporting documentation, such as applicant disclosure forms. We also requested and obtained information and documentation from the agencies on how they mitigated those risks. These examples are not reflective of all of the risks agencies have identified, but they provide valuable insight into these risks from across the selected agencies.

To address our second objective, we reviewed participating agencies’ documentation and interviewed agency officials in the SBIR and STTR program offices on their early experiences in implementing the due diligence programs they were required to establish by June 2023. We used the same categories of activities developed in our first report in this series, published in November 2023, to identify activities agencies have taken or plan to take to further refine their due diligence programs.[29] We then categorized the actions taken across the six refinement areas:

· Hire additional staff;

· Support additional training;

· Acquire due diligence vetting tools;

· Conduct workload assessments;

· Address timeliness concerns; and

· Leverage intra-agency assistance in due diligence evaluations.

We also conducted interviews and obtained documentation from other intra-agency entities that have provided support to their agencies’ due diligence processes. Specifically, we interviewed officials in entities that either provided open-source information or classified information (or both) to the SBIR/STTR awarding program offices. For example, within DOD we met with officials in the Office of Commercial and Economic Analysis (OCEA) that provides open-source information on SBIR/STTR applicants to awarding program offices across DOD. We also met with officials in the Air Force Office of Special Investigations which has provided counterintelligence information from classified resources to the Air Force SBIR/STTR awarding program offices on their small business applicants.

We compared the information we obtained from our interviews and review of documents to determine whether selected leading practices on agency collaboration were met.[30] Specifically, we identified the leading practice of developing and updating written guidance and agreements as most relevant for our review based on aspects of collaboration one would expect to see in early phases of a program’s implementation. To assess agency actions against this practice, we asked the SBIR/STTR program offices and the counterintelligence offices if agreements regarding the collaboration have been documented. We also reviewed agencies’ practices against internal control standards for documenting guidance.[31]

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to November 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

In May 2023, the Small Business Administration (SBA) issued the standardized disclosures required by the SBIR (Small Business Innovative Research) and STTR (Small Business Technology Transfer) Extension Act of 2022. SBA makes these disclosures publicly available as an appendix to its SBIR/STTR Policy Directive (see https://www.sbir.gov/about/policies). The disclosures are reproduced below with SBA permission.

GAO Contact

Candice Wright at (202) 512-6888 or wrightc@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Farahnaaz Khakoo-Mausel (Assistant Director), Sharron Candon (Analyst-in-Charge), Maggie Bryson, Kirby Callaway, and Madeline Mara made key contributions to this report. In addition, Jenny Chanley, Patrick Harner, Mark Kuykendall, and Curtis R. Martin contributed to the report.

GAO’s Mission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]In this report, we refer to the agencies that issue SBIR and STTR awards as “participating agencies.”

[2]National Science and Technology Council, Guidance for Implementing National Security Presidential Memorandum 33 (NSPM-33) on National Security Strategy for United States Government-Supported Research and Development (Washington, D.C.: January 2022).

[3]We have previously reported on federal R&D funding to foreign entities of concern, see GAO, Research Security: Strengthening Interagency Collaboration Could Help Agencies Safeguard Federal Funding from Foreign Threats, GAO‑24‑106227 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 11, 2024). In that report we recommended that the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) facilitate the sharing of information on identifying foreign ownership, control, or influence with federal R&D awarding agencies. In August 2024, we included this as a priority recommendation for OSTP to address.

[4]Pub. L. No. 117-183, § 4,136 Stat. 2180, 2181-86.

[5]GAO, Small Business Research Programs: Agencies Are Implementing Programs to Manage Foreign Risks and Plan Further Refinement, GAO‑24‑106400 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 16, 2023).

[6]In January 2021, the National Security Presidential Memorandum – 33 (NSPM-33) was issued to strengthen protections of U.S. government-supported R&D against foreign interference. The memorandum’s implementation guidance instructs federal agencies to prevent foreign countries from illicitly acquiring U.S. research and technology. It requires agencies funding R&D activities to establish and administer policies and processes that identify and mitigate risks to research security and integrity, including potential conflicts of interest and commitment. National Science and Technology Council, Guidance for Implementing NSPM-33 (Washington, D.C.: January 2022).

[7]In this report, for DOD, HHS and Commerce, we refer to the component—Air Force, NIH, and NOAA, respectively—we reviewed rather than the agency. For DHS and DOE, we refer to the Department name rather than the component because they are responsible for developing agencywide policy, guidance, and coordination on SBIR and STTR programs for their respective agencies. We use the term “selected participating agencies” or “selected agencies” throughout this report to refer to both the five components we reviewed individually (Air Force, DHS, DOE, NIH, and NOAA) and to the six agencies where one component issues all SBIR/STTR awards.

[8]15 U.S.C. § 638(f)(1), (n)(1)(A). Agencies’ R&D programs generally include funding for two types of R&D: intramural and extramural. Intramural R&D is conducted by employees of a federal agency in or through government-owned, government-operated facilities. Extramural R&D is generally conducted by nonfederal employees outside of federal facilities. Federal agency, as defined under the statute, does not include agencies within the intelligence community. 15 U.S.C. § 638(e)(2).

[9]SBIR/STTR Policy Directive § 5(a).

[10]The Extension Act also states that agencies are required to submit a report annually to Congress and SBA that contains information related to the development of their due diligence program. SBA is also required to report to Congress on a yearly basis whether participating agencies are utilizing the additional 2 percent funding, permitted to be set aside from the SBIR program funding by the Extension Act, for the cost of establishing the due diligence programs. 15 U.S.C. § 638(vv)(3). Additionally, 15 U.S.C. § 638(mm) permits federal agencies required to conduct a SBIR program to use up to 3 percent of the funds allocated to the SBIR program for the administration of the SBIR/STTR program.

[11]The National Institute of Standards and Technology describes cybersecurity practices as measures to prevent, detect, and respond to attacks (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1 (April 16, 2018)).

[12]SBIR/STTR Size and Eligibility Requirements for SBIR/STTR Programs, 13 C.F.R. §§ 121.701-05 (2023).

[13]See app. II for the standardized disclosure form—Required Disclosures of Foreign Affiliations or Relationships to Foreign Countries—issued by SBA in May 2023.

[14]GAO‑24‑106400. In May 2024, DOD released an agencywide memorandum on the policy and implementation guidance for its SBIR and STTR due diligence program, aiming to ensure that common standards are applied consistently across all DOD components. For example, the policy requires, among other things, that (1) all applicants submit the SBA-approved “Disclosures of Foreign Affiliations or Relationships to Foreign Countries” form; (2) DOD components review applicants’ disclosure information and publicly and commercially available information on applicants and compare it against the “Review Decision Matrix” included in the memorandum; and (3) components make referrals to counterintelligence as deemed necessary. DOD made the memorandum publicly available on its website: https://media.defense.gov/2024/May/23/2003471996/-1/-1/1/DUE_DILIGENCE_PROGRAM_OSD003584_24_RES.PDF. The public release notice also provided a link to a DOD online course created for small businesses on foreign ownership, control, or influence (FOCI), which defines the issue and details its potential effect on a SBIR/STTR applicant.

[16]We use “some” and “most” to characterize agency responses. We define “some” as 4 to 9 and “most” as 10 agencies. For further information on our methodology, see app. I.

[17]Officials from both the DOE SBIR program and the Office of Intelligence and Counterintelligence told us they also have a Memorandum of Understanding to clarify roles and responsibilities for staff supporting the due diligence program.

[18]GAO, Small Business Research Programs: Reporting on Award Timeliness Could Be Enhanced, GAO‑23‑105591 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 12, 2022). According to the SBA SBIR/STTR Policy Directive, all but two participating agencies are required to review proposals and notify applicants of the agency’s award decision within 90 calendar days after the closing date of a solicitation and recommended to issue an award within 180 days after the closing date. The directive requires two agencies—NIH and NSF—to notify applicants no more than 1 year after the closing date of the solicitation and recommends award issuance no more than 15 months after the closing date. SBIR/STTR Policy Directive § 7(c)(1).

[20]Not all agencies—NOAA, DOT, NIH, USDA—had completed a full award cycle during this review.

[22]GAO‑24‑106400. The Extension Act requires agencies to at least include open-source information in their due diligence reviews.

[23]DOE SBIR/STTR program officials stated they are in process of revising their due diligence procedures to transition from the counterintelligence office to its Research, Technology, and Economic Security Office (established in 2023) to perform open-source analysis on SBIR applicants. That office will then reach out to DOE’s counterintelligence office to conduct a more in-depth analysis using classified resources, if needed. This transition is under development and, once it is finalized (expected by December 2024), DOE plans to update the prior agreement with counterintelligence accordingly.

[24]GAO, Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2023).

[25]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014).

[26]Pub. L. No. 117-183, § 4, 136 Stat. 2180, 2183.

[27]In this report, we refer to the agencies that issue SBIR and STTR awards as “participating agencies.” Six agencies participated in STTR at the time of our review.

[28]DHS’ Science and Technology Directorate provides agency-wide guidance, policies, and procedures for DHS’ SBIR/STTR awarding components. Similarly, DOE’s Office of Science coordinates policies and procedures for all the SBIR/STTR awarding DOE components except for the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy.