EXPORT CONTROLS

Commerce Should Improve Workforce Planning and Information Sharing

Report to the Honorable Charles E. Schumer, Minority Leader, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Nagla'a El-Hodiri at elhodirin@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107431, a report to the Honorable Charles E. Schumer, Minority Leader, U.S Senate

Commerce Should Improve Workforce Planning and Information Sharing

Why GAO Did This Study

To address varied foreign policy and national security concerns, the U.S. government has increasingly used export controls. For example, the U.S. has imposed export controls to restrict access to advanced semiconductors that could aid the People’s Republic of China in developing military systems powered by artificial intelligence.

BIS is primarily responsible for reviewing applications and issuing licenses to exporters of dual-use technologies that could be used for both civilian and military purposes. DOD, DOE, and State also play roles in reviewing export license applications.

GAO was asked to review BIS’s resources and processes for export licensing. This report examines (1) BIS's resources from fiscal years 2013 through 2024, (2) the extent to which BIS has conducted workforce planning, and (3) the extent to which BIS shares information and consults with reviewing agencies. GAO reviewed legislation and agency documents; interviewed Commerce, DOD, DOE, and State officials; and analyzed agency funding, staffing, and workload data

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making four recommendations, including that Commerce conduct long-term workforce planning, provide reviewing agencies access to all relevant information, and consult with reviewing agencies prior to changing license conditions. Commerce concurred with the recommendations.

What GAO Found

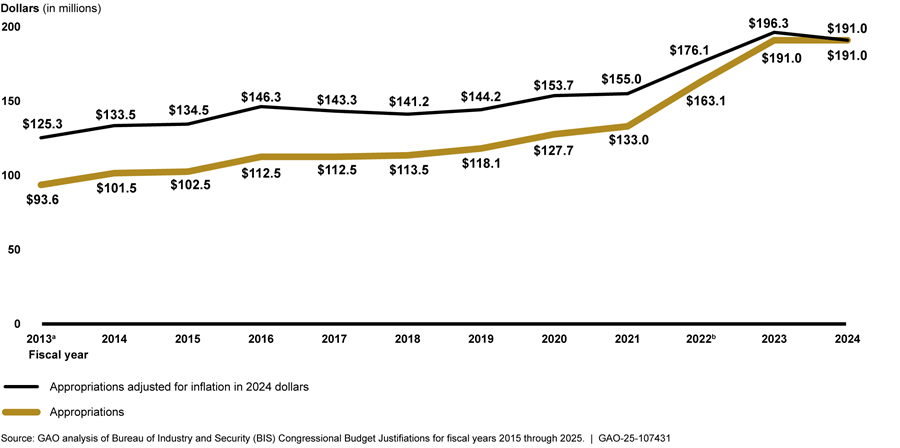

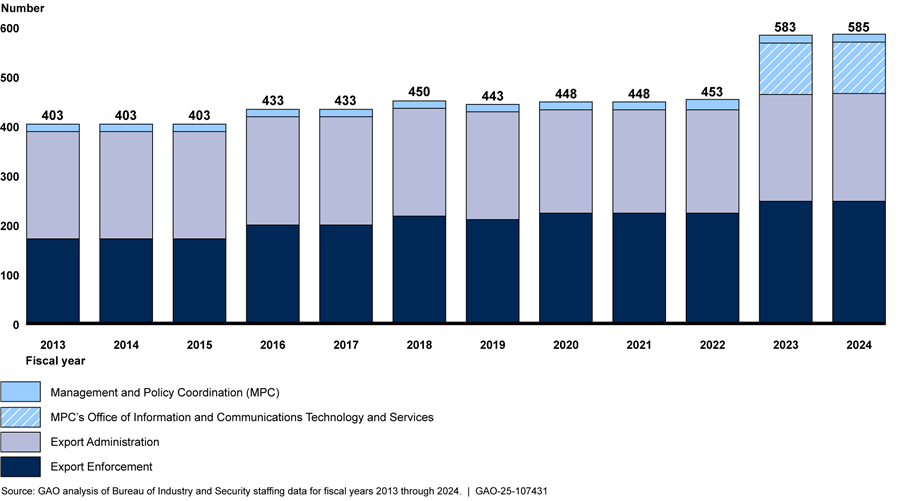

Funding for Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) grew by $97 million and roughly doubled from fiscal years 2013 through 2024. During this timeframe, the number of funded positions in BIS went from 403 to 585—an overall increase of 182 positions. About $58 million (60 percent) of BIS’s 12-year funding increase was appropriated in fiscal years 2022 and 2023. BIS primarily used these recent increases in two areas. First, to bolster implementation and enforcement of export controls in response to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Second, to create a new office focused on securing the U.S. information and communications technology and services supply chain.

However, BIS does not have a long-term workforce plan to determine its resource needs. Instead, BIS assesses its staffing needs on an annual basis as part of the budget request process. BIS last conducted a bureau-wide workforce planning effort in 2016. Comprehensive, long-term workforce planning would help BIS leadership determine the size and composition of its workforce needed to meet its expanding workload and better position it to reduce the risk of exporting sensitive, dual-use items to an adversary.

BIS oversees an interagency export license review process which includes reviews by the Departments of Defense (DOD), Energy (DOE), and State. However, challenges to information-sharing and limited consultation compromise the integrity of these reviews. For example, BIS does not provide the agencies ready access to all relevant information about export license applications, which is housed in multiple classified and unclassified systems. Providing reviewing agencies with easy access to all information relevant to license applications would help ensure reviews are well informed. In addition, officials from reviewing agencies told us that BIS has sometimes removed agreed upon license conditions without consultation. According to BIS, it removed conditions that were redundant or inconsistent with standard licensing provisions. Consulting with reviewing agencies prior to changing or removing conditions would help ensure that licensing decisions fully reflect national security risks and other concerns.

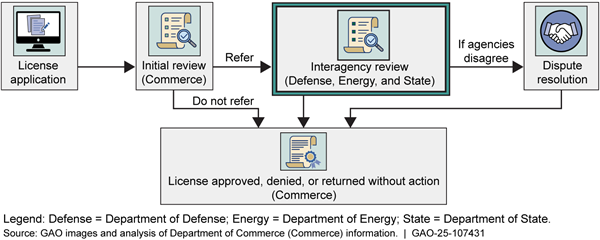

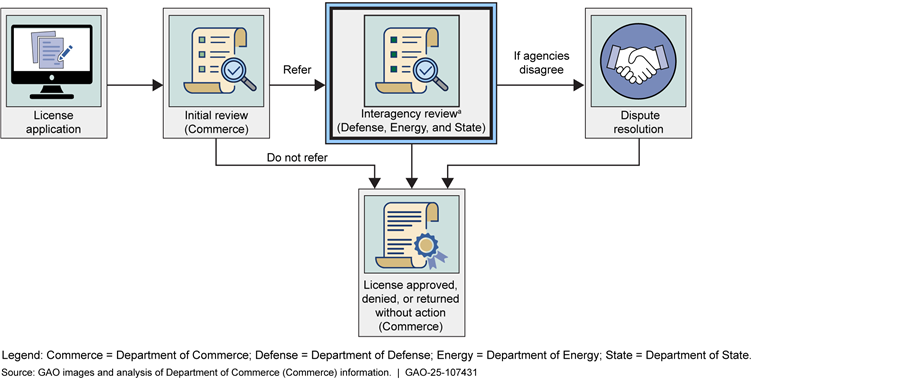

Key Steps in Interagency Review Process for Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security Export License Applications, as of April 2025

Abbreviations

|

ANPRM |

Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking |

|

AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

|

BFIRS |

Bona Fides Information Reports |

|

BIS |

Bureau of Industry and Security |

|

CUESS |

Commerce Exporter Support System |

|

Commerce |

Department of Commerce |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

EA |

Export Administration |

|

EAR |

Export Administration Regulations |

|

ECRA |

Export Control Reform Act of 2018 |

|

EE |

Export Enforcement |

|

MPC |

Management and Policy Coordination |

|

OICTS |

Office of Information and Communications |

|

State |

Department of State |

|

USXPORTS |

U.S. Exports System |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

June 26, 2025

The Honorable Charles E. Schumer

Minority Leader

United States Senate

Dear Minority Leader Schumer:

The U.S. government administers an export control system to manage national security and other risks linked with exporting sensitive items while also facilitating legitimate trade. The U.S. has increasingly used export controls to address a wide range of national security risks by curtailing the export of sensitive “dual-use” items—such as advanced semiconductors and radars that could be used for both civilian and military purposes. For example, the U.S. has recently restricted certain technological exports to China that could aid its efforts to develop advanced military systems powered by artificial intelligence (AI).

The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) at the Department of Commerce is responsible for implementing export controls for dual-use items, specified commercial satellite items, and certain firearms and related munitions. In carrying out these responsibilities, BIS engages with interagency partners to review export license applications.

Some members of Congress have questioned whether BIS possesses the resources to address growing workload demands resulting from factors such as:

· the March 2020 transfer of responsibility for export controls over certain firearms and related items (for example, ammunition and optical sighting devices) from the Department of State’s jurisdiction to Commerce’s jurisdiction, and

· the increased use of export controls related to Russia and China.

In addition, there is concern about how expeditiously BIS can identify and impose controls on emerging and foundational technologies, as required by the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (ECRA).

You asked us to review BIS’s resources and processes for implementing export controls. This report examines (1) changes to BIS’s funding and staffing resources from fiscal years 2013 through 2024, (2) the extent to which BIS has conducted workforce planning to address its resource needs, and (3) the extent to which BIS shares information and consults with external reviewing agencies. In addition, appendix I of this report includes information on actions BIS has taken to implement selected requirements of ECRA.

To understand changes to BIS’s resources over the last decade, we analyzed BIS funding and staffing data from fiscal years (FY) 2013 through 2024. To assess the extent to which BIS has conducted workforce planning to address its resource needs, we analyzed its budget requests from FY 2015 through FY 2025 and other workload data on selected agency activities, such as the number of licenses processed, and end-use checks conducted. We also interviewed agency officials about their workforce planning activities. We assessed these activities against the U.S. Office of Personnel Management Workforce Planning Guide criteria.[1]

To examine the extent to which BIS shares information and consults with external reviewing agencies, we reviewed standard operating procedures from Commerce regarding the review of export license applications and the sharing of information with external reviewing agencies. We interviewed officials from BIS, the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Energy (DOE) and State who are involved in the review of export license applications, and the dispute resolution process. We discussed with them the data systems they use to share information relevant to the licensing process. In addition, we reviewed documentation, including a 2014 memorandum BIS developed to provide guidance for reviewing agencies on placement of conditions on export licenses. We assessed these activities by comparing them with federal internal controls standards related to external communication.[2]

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

The U.S. government implements an export control system to manage the risks involved with exporting dual-use items and certain munitions items, and ensure legitimate trade.[3] For example, the U.S. might restrict the export of certain items to an adversary while permitting the export of the same items to an ally.

Export Control System for Dual-Use Items and Agency Roles

BIS administers export controls for dual-use items, certain firearms and related munitions, and specified commercial satellite items.[4] To implement these controls, BIS imposes licensing requirements, screens license applications against internal watch lists, performs end-use checks, and conducts investigations of possible violations of export control laws and regulations.[5]

External agencies, including DOD, DOE, and State play roles in reviewing dual-use export license applications to mitigate national security risks and other foreign policy concerns as necessary. Through this interagency review process, each agency makes an independent recommendation as to the decision to approve, deny, or return the license application without action.[6]

In cases where the agencies disagree, the export license application is escalated through an interagency dispute resolution process.[7] Once the disagreement is resolved, BIS records a final determination to either approve the license, deny it, or return the application without action (see fig.1). Once a license is approved, BIS monitors exports, including compliance with license conditions.

Figure 1: Key Steps in Interagency Review Process for the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security Export License Applications, as of April 2025

aThese agencies along with Commerce, are involved in the interagency review, although depending on the application, other agencies may be involved. Furthermore, while reviewing agencies have the authority to review any export license application submitted to Commerce, these agencies may determine that they do not need to review certain types of applications.

Note: Commerce’s interagency license review process, including dispute resolution, is outlined in Executive Order 12981: Administration of Export Controls, 60 Fed. Reg. 62,981 (Dec. 8, 1995) and set forth in the Export Administration Regulations at 15 C.F.R. § 750.4.

Aside from licensing, BIS performs several additional functions related to export controls. For example, BIS:

Conducts end-use checks. BIS may conduct end-use checks to verify the reliability of foreign end-users and legitimacy of proposed transactions, and to provide reasonable assurance of compliance with the terms of the license and proper use of the licensed items.[8] End-use checks include pre-license checks in support of the license application review and post-shipment verifications after the license has been approved and items have shipped.[9]

Maintains screening lists. BIS maintains various screening lists that may restrict access to U.S. exports. For example, the Entity List identifies persons reasonably believed to be involved in or believed to pose a significant risk of becoming involved in, activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy of the United States. BIS oversees an interagency process for adding and removing entities from this list.[10]

Educates and coordinates. BIS educates exporters on their compliance obligations, works with interagency partners to develop new export controls or revise existing controls, and coordinates with foreign partners and multilateral regimes on export controls.

Investigates. BIS investigates suspected violations of export controls and pursues criminal and administrative penalties against violators.

According to BIS, its workload has increased significantly in recent years due to increased export controls in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the increased scrutiny on exports to China, and the transfer of responsibility for certain firearms from State’s to BIS’s jurisdiction. BIS officials noted that they have also taken on various tasks following the passage of the ECRA, including provisions related to the identification and control of emerging and foundational technologies as well as specific activities of U.S. persons related to weapons of mass destruction and foreign military intelligence end uses and end-users.

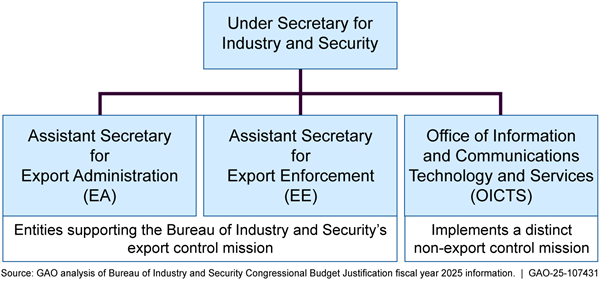

BIS Mission and Structure

BIS’s mission is to advance U.S. national security, foreign policy, and economic objectives by ensuring an effective export control and treaty compliance system and promoting continued U.S. strategic technology leadership. Historically, BIS was structured around two main lines of effort supporting its export controls mission: Export Administration (EA) and Export Enforcement (EE).

A third line of effort separate from BIS’s traditional export control mission, the Office of Information and Communications Technology and Services (OICTS), was added in FY 2022 to protect the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the U.S. from risks posed by foreign adversaries in the U.S.’s information and communications technology and services supply chain.[11] OICTS is housed within BIS’s Management and Policy Coordination (MPC), a preexisting office that provides leadership, management, policy guidance, and other support to all of BIS. See figure 2 for a simplified BIS organizational chart.

Figure 2: Simplified Organizational Chart for the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), as of March 2025

Note: BIS’s budget has three components: EA, EE, and Management and Policy Coordination (MPC), and overhead personnel that support all components. At the time OICTS was created, BIS determined oversight for the program fit under its Office of the Under Secretary which is funded under MPC.

Export Administration activities include:

· reviewing export license applications in coordination with interagency partners and issuing licenses for the export, re-export, or transfer of items consistent with national security and foreign policy goals;

· developing policies and issuing regulations related to items subject to the Export Administration Regulations (EAR);[12] and

· working with international partners to develop and implement frameworks for the transfer of items useable in conventional, chemical, nuclear, and missile armaments (arms) and systems, and assuring consistent international controls on items of concern.

Export Enforcement activities include:

· using Special Agents with law enforcement authority to investigate violations of the EAR, exports to unauthorized military end uses, illicit proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, terrorist activities, human rights abuses, and other noncompliant actions to safeguard U.S. national security;

· advising U.S. and foreign exporters, manufacturers, universities, banks, and the public on the substance and application of the EAR; and

· identifying reliable parties through its compliance efforts, and conversely identifying unreliable parties through its end-use monitoring program and taking enforcement action or regulatory action such as designation on the Entity List or Unverified List.[13]

Office of Information and Communications Technology and Services aims to protect the nation’s information and communication systems from foreign adversary threats. Adversarial countries could use critical technologies within U.S. supply chains for surveillance and sabotage to undermine national security. Broadly speaking, the OICTS focuses its investigations on information and communications technology and services used in the digital economy. In other words, technologies that: (1) use, process, or retain sensitive personal data of U.S. persons; and (2) connect with and communicate via the internet.[14]

For example, connected vehicles enable the capture of information about geographic areas or critical infrastructure, and present opportunities for malicious actors to disrupt the operations of infrastructure or the vehicles themselves, according to BIS. Accordingly, in January 2025, BIS issued a final rule prohibiting certain transactions involving the sale or import of connected vehicles integrating specific pieces of hardware or software, or those components sold separately, with a sufficient nexus to the People’s Republic of China or Russia.

BIS Used Recent Funding and Staffing Increases in Efforts to Counter Foreign Adversaries

BIS Funding Has Increased Since 2013, Mostly in Recent Years

BIS’s appropriations grew by about $97 million (104 percent) from FY 2013 through FY 2024. About $58 million (60 percent) of this 12-year increase occurred in FY 2022 and FY 2023, including $22 million from a supplemental Ukraine appropriation in FY 2022.[15] BIS primarily used these FY 2022 and FY 2023 funding increases to (1) bolster implementation and enforcement of export controls in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and (2) support the creation of OICTS, which focuses on protecting the U.S. information and communications technology and services supply chain from foreign adversaries—a mission distinct from BIS’s historical export controls focus.[16]

Adjusting for inflation, BIS’s appropriation increased by about $66 million (52 percent) from FY 2013 through FY 2024, averaging about 4.8 percent growth annually over the period (see fig. 3).

Figure 3: Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security’s Nominal and Inflation Adjusted Appropriations, Fiscal Years 2013 through 2024

aThe BIS nominal appropriation for FY2013 includes a $8.2 million recission.

bThe $163.1 million includes the $141 million FY 2022 annual appropriations for BIS and $22.1 million from the Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022. These Ukraine supplemental funds were available to be expended through September 30, 2024. Pub. L. No. 117-103, Div. N, 136 Stat. 776 (Mar. 15, 2022).

Office Created in 2022 Accounted for the Majority of BIS’s Staffing Growth since 2013

The number of BIS funded positions increased from 403 to 585—an overall increase of 182 positions—from fiscal years 2013 through 2024 (see fig. 4).[17] Of the 182 positions,104 (57 percent) were allocated in FY 2023 to support implementation of the newly-created OICTS.[18] Seventy-seven positions (42 percent) were allocated for the offices that implement BIS’s traditional export controls mission, EA and EE.

· EA staffing remained largely unchanged from FY 2013 (217 positions) to FY 2024 (218 positions), with some fluctuations in the number of positions over those years.

· EE staffing, on the other hand, grew from 171 to 247 positions (44 percent) over this period. To keep pace with the increased work related to China, Russia, and other foreign adversary threats, BIS requested staffing increases to hire additional special agents and enforcement analysts, according to BIS’s FY 2023 Congressional Budget Justification report.

As of the end of FY 2024, about 9 percent of BIS’s funded positions (52 of 585) were vacant, spread evenly across EA, EE, and OICTS.[19]

Figure 4: Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security’s Funded Positions by Office, Fiscal Years 2013 through 2024

Note: The 585 positions in FY 2024 include 56 temporary positions that were funded from amounts made available by the Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022 and subsequently converted to permanent positions.

BIS used some of the $22 million from the Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2022 to create 57 temporary positions.[20] In FY 2023 and FY 2024, BIS converted 56 of the 57 temporary positions to fill existing permanent positions that were vacant (26 in EE and 30 in EA).[21] According to BIS officials, it converted the temporary hires using FY 2023 and FY 2024 funding.

BIS Has Not Conducted Comprehensive Long-term Workforce Planning Needed to Address Increases in Workload Demand

BIS does not have a comprehensive long-term workforce plan to assess its resource needs to meet increasing demands and BIS did not make long-term use of the workforce plan it developed in 2016. Conducting long-term workforce planning would help BIS determine the funding and staff it needs to accomplish its national security mission as the use of export controls expands.

Agencies should conduct workforce analyses to identify the number of employees needed in the future based on business needs and generally develop a long-term (2 to 3 years) workforce plan, according to Office of Personnel Management’s Workforce Planning Guide.[22] Furthermore, as we have previously reported, workforce planning is not possible without a complete analysis of workload, which among other things includes a workload assessment incorporating work activities, frequency, and time required to conduct them, which is a key practice in designing staffing models.[23]

BIS’s Long-term Planning Efforts

BIS last conducted a long-term planning effort in 2016 when it released a workload assessment that was to serve as the basis for a 5-year budget strategy.[24] The workload assessment addressed work activities, frequency, and time required to conduct them. The assessment recommended a growth path and a set of potential workforce investments for BIS to meet its mission beginning in FY 2018 and continuing through FY 2022.

However, our review of budget requests from FY 2018 through FY 2022, the timeframe the plan referenced, found that the plan was not mentioned after FY 2017. BIS officials stated that they were unable to provide additional confirmation regarding the use of the plan after FY 2017 since the employees previously associated with it were no longer employed at BIS.

Although BIS has not conducted a comprehensive workload assessment or long-term workforce plan since the 2016 effort, it has undertaken some targeted workforce planning. Specifically, Commerce hired a contractor to help it determine OICTS’s internal structure, office placement, and resources. The assessment included an estimate of workload and workforce resources.[25] However, this assessment did not include EE and EA activities.

According to BIS officials, BIS conducts its resource planning annually. BIS officials told us that “volatility in the fiscal environment” and BIS’s recent focus on other sources of funding like supplemental funding for Ukraine discourages them from forecasting beyond annual budget requests. BIS officials said that BIS identifies its most critical mission needs for financial and personnel resources every year and requests these resources from Congress through its President’s Budget Requests.[26] However, BIS did not provide documentation or analysis of how it arrived at the requested number of positions in its annual requests to Congress.

BIS’s Efforts to Measure Workload

BIS described other ways it has tracked its workload and assessed its resource needs. However, we found these efforts fall short of some of GAO’s key practices for designing staffing models and commonly used practices in workforce analysis. BIS provided data showing how its workload across various activities had changed from FY 2013 and FY 2023 (see table 1). BIS officials told us that these workload measures are critical to understanding the volume, complexity, and efficiency of tasks performed by BIS individuals. For example, BIS data show that the number of export license applications processed by BIS increased by 53 percent and the number of additions to the Entity List increased by 151 percent since FY 2013.

Table 1: Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security’s Selected Workload Measures, Fiscal Years 2013 and 2023

|

Activity |

Description |

2013 |

2023 |

Percent Change |

|

Export Administration |

|

|

|

|

|

License Applications Processed |

Export license applications reviewed and approved by licensing officers |

24,782 |

37,943 |

+53.1% |

|

Licensing Determinations Processed |

Determination whether a license was required for a specific transaction |

2,222 |

3,411 |

+53.5% |

|

Entity List Additions |

Number of parties identified and listed that pose a risk to national security/foreign policy |

185 |

465 |

+151.4% |

|

Commodity Classification Requests Processed |

Requests to classify items under Commerce’s export control regulations |

5,577 |

3,700 |

-33.7% |

|

Commodity Jurisdictions Reviewed |

Requests related to reviewing agency jurisdiction over exported items |

1,203 |

191 |

-84.1% |

|

Export Enforcement |

|

|

|

|

|

End-Use Checks |

End-use checks, both pre-license and post-shipment verification checks, to ensure exports of items subject to the Commerce’s regulations are used properly by end-users |

1,033 |

1,509 |

+46.0% |

|

Actions Resulting in a Deterrence or Prevention of a Violation, and Cases Resulting in a Criminal or Administrative Charge |

Preventive enforcement actions such as detention of suspect exports, seizures of unauthorized shipments, and issuance of warning letters. |

1,403 |

1,846 |

+31.6% |

Source: GAO analysis of Bureau of Industry and Security data. | GAO‑25‑107431

These metrics shown in table 1 are helpful to understand changes over time in BIS’s workload related to certain activities. However, the metrics do not address the time required to conduct the activities or the number of staff needed to conduct them.

BIS also shared with us a document it referred to as a workload assessment, created in March 2024, in which it described its growing workload and identified the need for more enforcement and technical experts.[27] In written responses to our questions, BIS noted:

“The assessment involved collaboration across various BIS offices, including EE, EA, and the Office of the Chief Counsel. A workforce planning and staffing allocation model was utilized to arrive at the proposed numbers. This model involved analyzing current workload metrics, forecasting future demands, and identifying critical gaps in staffing.”

Although we asked BIS for the analysis underlying its assessment, the material BIS shared did not clearly lay out how BIS determined its anticipated workload and staffing needs. Specifically, the material BIS provided did not include the model used to develop the estimates.

Without comprehensive long-term workforce planning, BIS cannot determine the resources and personnel it needs to meet future organizational demands. Conducting such planning would better position BIS to protect sensitive, dual-use items from adversaries and meet its national security mission well into the future.

BIS Did Not Provide Reviewing Agencies Ready Access to All Relevant Information or Consult with Them When Removing License Conditions

BIS Data Systems Do Not Provide Ready Access to All Relevant Information

According to officials from State, DOD, and DOE, the data systems BIS uses do not provide reviewing agencies easy access to all relevant information on the legitimacy and reliability of parties to export transactions. BIS and reviewing agencies use a variety of data systems to process export license applications and share information relevant to these applications. BIS processes export license applications using the Commerce USXPORTS Exporter Support System (CUESS). Interagency referrals made in CUESS are then transmitted to DOD, DOE, and State for their review and licensing recommendations via USXPORTS, a classified system.[28]

BIS uses other systems to share supporting documents important to agencies’ review of export license applications. BIS produces and stores information on a classified SharePoint website to share documentation and other reporting that may contain important information about parties to a proposed export transaction, according to agency officials.[29] Also, according to BIS, when reviewing agencies disagree on the disposition of a license application, BIS shares information with them through classified email in preparation for interagency license review meetings (see table 2).

|

System |

Description |

Available to reviewing agencies |

|

Commerce USXPORTS Exporter Support System (CUESS) |

BIS’s unclassified system that BIS uses internally to process export license applications. |

Intermittenta |

|

USXPORTS |

DOD’s classified system that BIS uses to transmit export license applications from CUESS to reviewing agencies and reviewing agencies use to provide their licensing recommendations. |

Yes |

|

BIS classified SharePoint website |

BIS’s classified website that includes a searchable repository for BIS reporting and other documentation created since 2016 that may be relevant to an export transaction. |

Upon request and approval |

|

Classified email |

Classified email used by BIS to disseminate relevant information to reviewing agencies in advance of interagency license review meetings. |

Yes |

BIS = Bureau of Industry and Security; DOD = Department of Defense; DOE = Department of Energy

Source: GAO analysis of BIS, DOD, DOE, and State information. | GAO‑25‑107431

aAccording to BIS, it has made CUESS available to reviewing agency officials at times, such as during the pandemic and prolonged USXPORTS outages.

Officials from reviewing agencies cited examples of challenges in accessing information needed for license application reviews. For example, DOE noted that searching through multiple systems for relevant documentation, such as Bona Fides Information Reports (BFIR), is time consuming. BIS produces BFIRs to assess the degree of risk of a foreign party involved in an export transaction. However, according to DOD and DOE officials, a limited number of staff at the agencies have access to a secret-level classified SharePoint site managed by BIS where BFIRs are stored, and requesting additional access takes time. Moreover, DOE officials stated that because BIS does not upload BFIRs to USXPORTS, DOE is not always aware that a BFIR exists or has been requested, and therefore may not know to search the classified SharePoint site.

Reviewing agency officials said they sometimes use the EAR dispute resolution process to ensure they have full information about an export license application. Specifically, agency officials stated that they have at times recommended denial for an application to trigger an interagency dispute resolution process where additional information is made available to all the parties.[30] However, using the dispute resolution process in this manner, rather than resolving issues between the licensing and reviewing officials may result in unnecessary and inefficient use of resources and increased process time, according to agency officials.

BIS officials acknowledged that no single system fully accommodates all relevant information that agencies stated they need to conduct their reviews. DOD officials noted that USXPORTS was intended to serve as the official export licensing database for all agencies, but BIS does not use it as the system of record. Instead, BIS primarily uses CUESS to process applications internally and uses USXPORTS solely to facilitate interagency license referrals. This inhibits information-sharing because CUESS is an unclassified system and USXPORTS is a classified system.

BIS stated that potential adjustments to CUESS to allow documents uploaded by BIS to be transferred into USXPORTS would improve interagency access to information, as would the creation of a dedicated portal for classified information with access for all reviewers. BIS noted that it has continued to make incremental improvements to its data systems as resources allow. Its 2025 budget request asked for $3.5 million for resources to begin broader IT modernization efforts.[31] According to BIS officials, improvements to add information-sharing functionality to USXPORTS would be the responsibility of DOD.

Federal internal control standards state that management should communicate necessary quality information externally so that external parties can help the agency achieve its objectives and address related risks.[32] Additionally, information sharing is supported by a policy statement included in the ECRA.[33] Without ready access to all relevant information, the licensing recommendations of reviewing agencies—and therefore the ultimate licensing determination by BIS—may not reflect important foreign policy and national security considerations.

BIS Did Not Consult with Reviewing Agencies When It Removed Proposed Export License Conditions

According to officials from DOD, DOE, and State, BIS officials have removed export license conditions recommended by reviewing officials without consulting with the reviewing agencies. Specifically, DOD officials identified seven licenses where BIS removed one or more license conditions that had been agreed to through the dispute resolution process, by the Operating Committee.[34]

According to BIS, it removed conditions for five of the seven licenses cited by DOD because the conditions did not comply with a November 2014 memorandum BIS sent to the reviewing agencies.[35] The memorandum provided guidance on standard terms, conditions, and riders on BIS licenses.[36] BIS told us that it ultimately imposed conditions for two of the seven licenses cited by DOD. For the five licenses where BIS acknowledged removing conditions, BIS stated that

· for three licenses, it removed conditions that repeated exporter assurances; and

· for two licenses, it removed conditions related to items or end-uses that were not requested for export or did not apply to the transaction.

According to DOD officials, its leadership discussed the 2014 memorandum with BIS leadership and both agencies agree that it does not allow for unilateral action on the part of BIS to remove license conditions without consulting with the agency that recommended them. Moreover, according to officials from DOD responsible for reviewing export license applications, the 2014 memorandum is outdated and confusing. Further, DOD officials told us it was not clear whether reviewing agencies had agreed to the memorandum’s directives. DOD officials expressed concern that there had been misinterpretations of the memorandum, including BIS’s removal of conditions without discussion. The officials noted that they learned of the removals while, in the process of reviewing new license applications, they searched for precedent information and found the conditions removed. Comments from officials at State and DOE corroborated the concern that BIS guidance on placement of conditions has led to misinterpretation.

BIS stated that it agreed in 2023 to no longer remove conditions inconsistent with the 2014 memorandum and instead escalate these cases for interagency discussion and dispute resolution. However, it is not clear that escalation alone would resolve the issue that DOD brought to our attention. DOD officials told us that in the seven cases they cited, BIS removed the conditions after the license applications had been escalated for dispute resolution and agreed to by the Operating Committee. Moreover, escalating cases requires additional agency resources and, according to BIS, contributes to longer license processing times. Clearer guidance on the application of conditions could prevent some agencies from proposing conditions that require escalation.

Federal internal control standards state that management should communicate necessary quality information externally so that external parties can help the agency achieve its objectives and address related risks.[37] Moreover, leading practices for interagency collaboration note that updating written guidance and agreements provides consistency in the long-term.[38]

According to reviewing agency officials, it takes considerable effort to craft specific conditions for license applications and these conditions are critical to mitigating national security concerns. For example, agencies tend to add conditions on sending certain technologies to China or countries that are manufacturing aerospace components for the People’s Republic of China. According to multiple officials, removing conditions without consulting with the reviewing agencies increases national security risks. Moreover, the lack of clarity and agreement with directives in the BIS 2014 memorandum has fostered confusion between interagency reviewers and BIS, contributing to additional cases being escalated for dispute resolution.

Conclusions

The expanded use of export controls in recent years to address an array of geopolitical challenges and national security risks has placed increasing demands on BIS’s workforce. With the continued emergence of AI and other strategically important technologies, this trend shows no sign of abating. Without the appropriate personnel, BIS may have difficulty meeting its national security mission, increasing the risk of foreign adversaries obtaining access to U.S. technologies that could cause the U.S. harm. Strategic workforce planning would help BIS leadership determine the size and composition of the workforce needed to meet its evolving mission and better position BIS to justify its resource requests.

Interagency reviews by DOD, DOE, and State play a critical role in ensuring that export license determinations reflect U.S. national security interests, among other things. The effectiveness of these appraisals hinge on seamless information-sharing between agencies, a key internal control principle reflected in ECRA. Providing reviewing agencies with ready access to all information relevant to a license application would help ensure their reviews are well informed. Moreover, consultation prior to BIS changing or removing conditions would help guarantee that licensing decisions fully reflect the concerns of reviewing agencies. Lastly, updated guidance on the appropriate use of license conditions would mitigate confusion among reviewing agencies and limit the number of cases that need to be escalated for dispute resolution.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following four recommendations to Commerce:

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Under Secretary for Industry and Security develops a long-term workforce plan to determine the resources and personnel it needs to meet its growing workload. (Recommendation 1)

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Under Secretary for Industry and Security works with DOD, DOE, and State to facilitate access to all relevant information on each export license application. (Recommendation 2)

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Under Secretary of Industry and Security consults with reviewing agencies prior to changing export license application conditions recommended by one or more of those agencies. (Recommendation 3)

The Secretary of Commerce should ensure that the Under Secretary for Industry and Security clarifies and reaches agreement with State, DOD, and DOE on written guidance for the use of export license conditions. (Recommendation 4)

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to Commerce, State, DOD, and DOE for review and comment. Commerce provided comments via email and concurred with the four recommendations. Commerce also provided technical comments, which we incorporated where appropriate. State, DOD, and DOE did not have any comments on the report.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Commerce, the Secretary of State, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of Energy, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at ElHodiriN@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Sincerely,

Nagla’a El-Hodiri

Director, International Affairs and Trade

Appendix I: Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) Actions to Implement Selected Export Control Reform Act Provisions

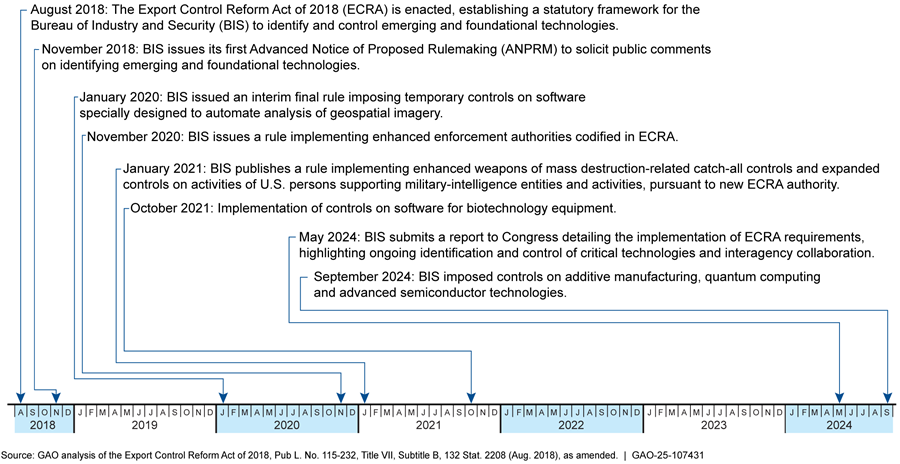

The Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (ECRA) authorized pre-existing export control regulations and processes developed to implement the Export Administration Act of 1979 and continued under authority of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act when the act lapsed. According to written responses from BIS, ECRA also imposed new requirements on BIS related to dual-use export control including a requirement to identify and control emerging and foundational technologies, which BIS refers to as “Section 1758 technologies.”[39] BIS identified several actions it has taken to implement these new requirements since 2018, described below (see fig. 5).

Figure 5: Timeline of Bureau of Industry and Security Actions Implementing Selected Export Control Reform Act of 2018 Provisions

The ECRA provisions that BIS identified as imposing new requirements on BIS include:

Identification of Emerging and Foundational “1758” Technologies. Section 1758 of ECRA requires the identification and control of emerging and foundational technologies essential to national security. According to BIS, it has built upon existing processes to identify and control 1758 technologies. This process includes obtaining input through Technical Advisory Committees, public consultations, and interagency collaboration, and making regular updates to export controls.[40] BIS also identified actions it has taken to implement several provisions within Section 1758:

· Interagency collaboration. ECRA requires establishment of a regular, ongoing interagency process including the Departments of Energy (DOE), Defense (DOD), and State, as well as other agencies as appropriate, to identify emerging and foundational technologies.[41] According to BIS, this approach is essential for the dynamic evaluation of technologies like quantum computing and artificial intelligence. Moreover, BIS continued to work with State, DOE, and DOD in the review and approval of export licenses—a process that predated ECRA. In addition, BIS works with the same agencies by focusing on identifying and developing potential control parameters for emerging and foundational 1758 technologies. These agencies are core members of BIS’s Emerging Technology Steering Committee, which spearheads BIS’s Section 1758 work.

· Public consultations. ECRA requires BIS to provide a notice and comment period.[42] Under this requirement BIS engages in public consultations on emerging and foundational technology controls by issuing public notices, such as advanced notices of proposed rulemaking (ANPRM), to gather feedback from industry stakeholders and the public on potential controls.[43] According to BIS, this practice is intended to ensure transparency and consider the perspectives of those affected by export controls. Consistent with this requirement, beginning in November 2018, Commerce published a series of ANPRMs or proposed rules in the Federal Register to seek public comment. While the practice of engaging in public consultation pre-dated the Act, BIS noted ECRA’s specific focus on consultations for 1758 emerging and foundational technologies.

· Alignment with international standards. ECRA requires BIS to seek to align multilateral export control regimes with proposed U.S. export controls on emerging and foundational technologies.[44] According to BIS, this requirement includes working with international partners to develop and implement controls addressing global security threats consistently. For example, BIS coordination with the Wassenaar Arrangement and the Australia Group exemplifies this requirement.[45] While international alignment and coordination on standards and agreements with partners and allies predated ECRA, BIS noted that the Act’s focus on consultations regarding 1758 emerging and foundational technologies was a new requirement.

Enhanced control mechanisms. According to BIS, ECRA provides BIS with authority over certain activities of U.S. persons wherever located, even when there is no related export, such as the provision of consulting and transportation services. In July 2024, BIS proposed rules to control U.S. person activities that could support military, intelligence, and security services.[46]

Enhanced enforcement. ECRA adds specific provisions for BIS to enhance enforcement and compliance including greater investigative authority and authority to conduct border searches and undercover operations.[47] According to BIS, initiatives like the Disruptive Technology Strike Force to counter threats from sensitive technology acquisitions by nation-state adversaries also aim to deter noncompliance and ensure robust enforcement of export control regulations.

Enhance technological and analytical capabilities. According to BIS, implementation of ECRA requires enhancements in technological and analytical capabilities within BIS to handle the increased complexity and volume of data related to export controls. According to BIS, this includes investments in modern data analytics systems and updated case management systems. For example, BIS implemented incremental improvements to its IT systems, including incremental functionality enhancements to its internal licensing database.

In addition, ECRA imposed new reporting requirements on BIS.[48] BIS has provided ten reports regarding implementation of section 1758 to Congress since 2018.

This report examines (1) changes to Bureau of Industry and Security’s (BIS) funding and staffing resources from fiscal years 2013 through 2024, (2) the extent to which BIS has conducted workforce planning to address its resource needs, and (3) the extent to which BIS shares information and consults with external reviewing agencies. In addition, appendix I of this report includes information on actions BIS has taken to implement selected requirements of the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (ECRA) that BIS determined imposed new requirements on the bureau.

To address the first objective, we analyzed BIS funding and staffing from fiscal years (FY) 2013 through 2024 using BIS’s annual budget submissions to Congress from FY 2015 through 2025.[49] We also interviewed agency officials about their funding and staffing over this period. We compared budget and staffing data published in the annual budget submissions with similar data we obtained from BIS. We discussed and resolved any differences we identified with BIS officials. We reviewed appropriation laws to corroborate funding levels and to determine funding and congressional direction related to the creation of the Office of Information and Communications Technology and Services. In this report, we present BIS’s annual appropriations in nominal and inflation-adjusted values. We adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index for the most recent year (FY 2024) as the reference period.

To address the second objective, we analyzed information on BIS’s workforce planning activities including a 2016 workload assessment. We also analyzed BIS’s annual budget requests from FY 2015 through FY 2025, as BIS stated that it identifies its most critical mission needs for financial and personnel resources and requests these needs from Congress through its annual budget requests. We reviewed Commerce’s Human Capital Strategic Plan 2023-2026, Commerce’s Strategic Plan 2022-2026, and BIS’s Annual Reports to Congress from FY 2021 through FY 2023 to determine if these documents supported BIS’s workforce planning efforts.[50]

We interviewed agency officials from BIS’s Office of the Chief Financial Officer to discuss any workforce planning activities it conducts. We also interviewed officials from Commerce’s Office of Human Resource Management to discuss any workforce planning support it provides to BIS. We obtained written responses from BIS’s Office of Policy and Strategic Planning regarding a March 2024 document it developed which it referred to as a workforce assessment. We assessed BIS’s workforce planning activities against the criteria in the U.S. Office of Personnel Management Workforce Planning Guide and GAO leading practices related to developing staffing models.[51]

In addition, we obtained and analyzed BIS data on 15 metrics it characterized as performance measures, performance goals, or workload measures. We cross checked data for selected metrics with data reported publicly by BIS on its performance dashboard website as well as with data it publishes in its annual congressional budget submissions. Based on our assessment, we found these data sufficiently reliable for discussing changes in BIS’s workload and providing an overview of selected BIS activities from FY 2013 through FY 2023.

To address the third objective, we interviewed and obtained written responses from agency officials at BIS and the Departments of Defense (DOD), Energy (DOE) and State involved in the review of export license applications, and the dispute resolution process for licensing disagreements. We obtained and reviewed standard operating procedures from BIS and DOD regarding the review of export license applications and sharing of information with external reviewing agencies as well as systems used to share information.

We assessed these activities by comparing them with federal internal control standards related to external communication. We obtained and reviewed a November 2014 memorandum BIS developed and shared with external reviewing agencies that specified appropriate placement of conditions on export licenses. We followed up with DOD, DOE, and State to understand and corroborate their responses regarding access to relevant licensing information and placing conditions on licenses. Finally, we followed up with BIS for its response to the reviewing agencies’ concerns.

We determined that the information and communication components of internal control were significant to this objective along with the underlying principle that management should externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[52] We assessed our findings from our reviews and interviews against this principle.

To identify actions BIS has taken to implement selected ECRA requirements, we reviewed the law establishing ECRA and created a list of requirements that we determined were new (in other words, requirements that did not exist before ECRA). We then asked BIS to identify ECRA requirements it viewed as new and compared its list with our analysis. Based on this comparison, we excluded activities BIS has historically conducted prior to ECRA. We obtained written responses from BIS officials regarding why they identified selected ECRA provisions and how these requirements differed from past efforts. The written responses included actions taken by BIS to implement the new ECRA requirements.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to June 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Nagla’a El-Hodiri, Elhodirin@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the individual named above, Drew Lindsey (Assistant Director), Tom Zingale (Analyst-in-Charge), Julie Hirshen, Neil Doherty, Mark Dowling, Jeff Isaacs, Steven Lozano, Donna Morgan, and Terry Richardson made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]U.S. Office of Personnel Management, Workforce Planning Guide (Washington, D.C.: November 2022).

[2]See, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014). Principle 15.

[3]The U.S. government implements a separate export control system for items with inherently military applications that provide a critical military or intelligence advantage. See 22 C.F.R. §§ 120-130. State is the lead agency for these controls, which were outside the scope of our review.

[4]Commerce controls dual-use exports through the implementation of the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) codified at Parts 730 to 774 of Title 15 of the Code of Federal Regulations, which contain the Commerce Control List. The Commerce Control List classifies less sensitive military items, dual-use items, and basic commercial items in 10 categories (e.g., Electronics, Lasers and sensors) and five product groups (e.g., Material, Software). Basic commercial items under BIS’s jurisdiction generally do not require the bureau’s authorization unless destined to a prohibited end use, end-user, or to an embargoed or sanctioned destination. As a general matter, these items are designated as “EAR99” items.

[5]BIS may also support investigations of possible export control violations conducted by the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security.

[6]Agencies can return export license applications without action if they are missing information or contain errors. Exporters may then correct the deficiencies and resubmit the application.

[7]The interagency review and dispute resolution process for Commerce export license applications is specified in Executive Order 12981: Administration of Export Controls, 60 Fed. Reg. 62,981 (Dec. 8, 1995) and set forth in the EAR at 15 C.F.R. § 750.4.

[8]In February 2025, we reported that Commerce’s end-use monitoring of firearms is hampered by staffing gaps, limited training, potentially conflicting duties, and insufficient data. See GAO, Export Controls: Improvements Needed in Licensing and Monitoring of Firearms, GAO‑25‑106849 (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 12, 2025).

[9]BIS may also conduct end-use checks for unlicensed exports of controlled items, such as those that qualified for a license exception.

[10]The U.S. End-User Review Committee is the interagency group that makes these decisions.

[11]According to OICTS officials, the office is charged with implementing three Executive Orders: (1) Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain, (2) Taking Additional Steps to Address the National Emergency with Respect to Significant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities, and (3) Protecting Americans’ Sensitive Data from Foreign Adversaries.

[12]Commerce controls the export, reexport, and in-country transfer of dual-use and certain less sensitive military items through the implementation of the EAR. ECRA provides statutory authority for the EAR.

[13]As previously noted, the Entity List restricts exports to persons reasonably believed to be involved, or posing a significant risk of becoming involved in activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy of the United States. The Unverified List contains the names and address of foreign persons who have exported, re-exported, or transferred in-country items subject to the EAR and whose legitimacy and reliability such as the end-use or end-user cannot be verified during an end-use check.

[14]The investigations focus on information and communications technology and services transactions (acquisition, importation, transfer, installation, dealing in, or use) with a foreign adversary nexus.

[15]Pub. L. No. 117-103, Div. N, 136 Stat. 776 (Mar. 15, 2022). The funding was available until September 30, 2024. We have a separate ongoing review (107079) examining Commerce’s use of these supplemental funds.

[16]The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 provided $141 million for BIS, an increase of approximately $8 million over the FY 2021 enacted level. Pub. L. No. 117-103, Div. B. The associated explanatory statement of the conference committee for this legislation noted the conference committee’s expectation that BIS would be the bureau that would execute Commerce’s responsibilities for implementation of Executive Order 13873, ‘‘Securing the Information and Communications Technology and Services Supply Chain.” The statement further noted that BIS’s appropriation was intended to provide funding necessary to carry out that responsibility. According to BIS officials, the bureau used $26 million of a $50 million increase in appropriated funding it received in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (Pub. L. No. 117-328) to support the establishment and operation of the OICTS.

[17]Funded positions represent both filled and vacant positions.

[18]One additional position was allocated to the part of MPC unrelated to OICTS.

[19]The number of vacancies in EA was 14, EE 19, and OICTS 18. Additionally, there was one vacancy in the part of MPC unrelated to OICTS.

[20]The act stipulated that the $22 million could not be used to increase the number of permanent positions but authorized BIS to appoint temporary personnel without regard to provisions of law governing appointments in the competitive service. Pub. L. No. 117-103, Div. N, 136 Stat. 777 (Mar. 15, 2022).

[21]BIS leveraged Office of Personnel Management direct hiring authority to convert temporary positions to permanent positions.

[22]Office of Personnel Management, Workforce Planning Guide (Washington, D.C.: November 2022). The guide is intended to help agencies comply with an Office of Personnel Management requirement, set forth at 5 C.F.R. § 250.204(a)(2), that human capital policies and programs be based on comprehensive workforce planning and analysis.

[23]GAO has identified four key practices for designing staffing models. The other practices are (1) incorporating risk factors, (2) involving key stakeholders, and (3) ensuring data quality to provide assurance that staffing estimates produced from the model are reliable. GAO‑16‑384.

[24]U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Industry and Security Five-Year Budget Strategy Plan (Falls Church, VA.; June 1, 2016).

[25]Deloitte provided BIS the assessment on August 3, 2021.

[26]According to BIS officials, its requests for staff are constrained by statutory budgetary restraints, such as the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (Pub. L. No.118-5,137 Stat. 10 (June 2023)) and thus it often substantially pares down its requests.

[27]The workload assessment was conducted by Commerce’s Office of Policy and Strategic Planning, whereas BIS’s annual budget justification documents are compiled by BIS’s Office of the Chief Financial Officer. The workload assessment included specific numbers for enforcement and technical experts. We have not included those numbers in this report because BIS noted they were highly preliminary.

[28]Though the external reviewing agencies have the authority to review any export license application submitted to Commerce, these agencies may determine that they do not need to review certain applications.

[29]Reporting and documentation may include Bona Fides Information Reports (BFIRs) and End-Use Statements. The purpose of BFIRs is to provide all interagency partners with the information needed to ascertain the degree of risk that foreign parties to export transactions will use items subject to the EAR for or divert them to end-uses or end-users of concern.

[30]The interagency dispute resolution is for instances where reviewing agencies are not in agreement on whether to approve, approve with conditions, or deny a license application. See 15 C.F.R. § 750.4(f).

[31]BIS currently is operating under a continuing resolution for the remainder of FY 2025 pursuant to which it was granted authority to obligate same amounts as was provided for FY 2024. See Pub. L. No. 119-4, 139 Stat. 10 (Mar. 2025).

[32]GAO‑14‑704G, Principle 15.

[33]ECRA states that the export control system “must ensure that it is transparent, predictable, and timely, has the flexibility to be adapted to address new threats in the future, and allows seamless access to and sharing of export control information among all relevant United States national security and foreign policy agencies.” See 50 U.S.C. § 4811(8).

[34]The EAR sets forth procedures for resolution of disagreements between reviewing agencies on whether to grant a license application or on conditions to be imposed on applications. These procedures include a four-stage escalation process for dispute resolution beginning with: (1) review by the Operating Committee chaired by an appointee of the Secretary of Commerce and consisting of representatives of appropriate agencies within the Departments of Commerce, State, Defense and Energy and with representatives of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Non-proliferation Center of the Central Intelligence Agency serving as non-voting members; (2) escalation to the Advisory Committee on Export Policy, if any agency disagrees with the Operating Committee Chair’s decision; (3) escalation to the Export Administration Review Board, if any agency disagrees with the Advisory Committee on Export Policy’s decision; and (4) the process culminates in potential appeal to the President from the Export Administration Review Board chaired by the Secretary of Commerce and whose other voting members are the Secretaries of State, Defense, and Energy, if any agency disagrees with the Export Administration Review Board’s decision. See 15 C.F.R. § 750.4.

[35]The seven cases included license applications for end users in China, India, Singapore, Ukraine, and others.

[36]The memorandum announced the creation of a new standard introductory statement to be included at the beginning of each license because the application of conditions that restated prohibitions or license requirements found elsewhere in the EAR caused confusion among some exporters. The memorandum noted that the inclusion of the statement would mean that reviewers would not need to put in conditions if no additional conditions to the EAR requirements were needed.

[37]GAO‑14‑704G, Principle 15.

[38]See, Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges, GAO‑23‑105520 (Washington, D.C.: May 24, 2023).

[39]See Pub. L. No. 115-232, § 1758, 132 Stat 2218 (Aug. 2018) codified at 50 U.S.C. § 4817.

[40]BIS uses Technical Advisory Committees, which consist of experts from various industries, academia, and government. These committees provide recommendations on the technical parameters for export controls and help identify technologies that may need regulation to protect national security. To support its work pursuant to Section 1758 of ECRA, BIS established the Emerging Technology Technical Advisory Committee (ETTAC) by issuing a notice of recruitment in August 2018. The ETTAC first met in May 2020 and has convened approximately quarterly since that time.

[41]See 50 U.S.C. § 4817(a).

[42]See 50 U.S.C. § 4817(a)(2)(C).

[43]See 50 U.S.C. § 4817(a). An ANPRM is a preliminary notice, published in the Federal Register, announcing that an agency is considering a regulatory action. The agency issues an ANPRM before it develops a proposed rule. The ANPRM describes the general area that may be subject to regulation and usually asks for public comment on the issues and options being discussed. An ANPRM is issued only when an agency believes it needs to gather more information before proceeding to a notice of proposed rulemaking.

[44]See 50 U.S.C. § 4817(c).

[45]The Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Arms and Dual-Use Goods and Technologies was established in July 1996 to contribute to international and regional security and stability by promoting transparency and greater responsibility in the transfer of conventional arms and dual use goods and technologies. The Australia Group is an informal arrangement that enables exporting and transshipping countries to minimize the risk of chemical or biological weapons proliferation.

[46]See 89 Fed. Reg. 60,985 (July 29, 2024).

[47]See 50 U.S.C. § 4820.

[48]See 50 U.S.C. § 4817(d), (e).

[49]The FY 2015 through FY 2025 budget requests contain the actual funding and personnel totals for FY 2013 through FY 2024.

[50]As of April 2025, the FY 2024 Annual Report had not been issued.

[51]U.S. Office of Personnel Management, Workforce Planning Guide (Washington, D.C.: November 2022) and GAO leading practices in developing staffing models. We identified leading practices from our previous reports that discussed staffing models, and staff within our agency with workforce-planning expertise.

[52]See, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: September 2014). Principle 15.