ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

DHS Needs to Improve Risk Assessment Guidance for Critical Infrastructure Sectors

Report to Congressional Addressees

United States Government Accountability Office

View GAO‑25‑107435. For more information, contact David B. Hinchman at (214) 777-5719 or hinchmand@gao.gov; or Tina Won Sherman at (202) 512-8461 or shermant@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO‑25‑107435, a report to congressional addressees

DHS Needs to Improve Risk Assessment Guidance for Critical Infrastructure Sectors

Why GAO Did This Study

AI has the potential to introduce improvements and rapidly change many areas. However, deploying AI may make critical infrastructure systems that support the nation’s essential functions, such as supplying water, generating electricity, and producing food, more vulnerable. In October 2023, the President issued Executive Order 14110 for the responsible development and use of AI. The order requires lead federal agencies to evaluate and, beginning in 2024, annually report to DHS on AI risks to critical infrastructure sectors.

GAO’s report examines the extent to which lead agencies have evaluated potential risks related to the use of AI in critical infrastructure sectors and developed mitigation strategies to address the identified risks. To do so, GAO analyzed federal policies and guidance to identify activities and key factors for developing AI risk assessments. GAO analyzed lead agencies’ 16 sector and one subsector risk assessments against these activities and key factors. GAO also interviewed officials to obtain information about the risk assessment process and plans for future templates and guidance.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is recommending that DHS act quickly to update its guidance and template for AI risk assessments to address the remaining gaps identified in this report. DHS agreed with our recommendation and stated it plans to provide agencies with additional guidance that addresses gaps in the report including identifying potential risks and evaluating the level of risk.

What GAO Found

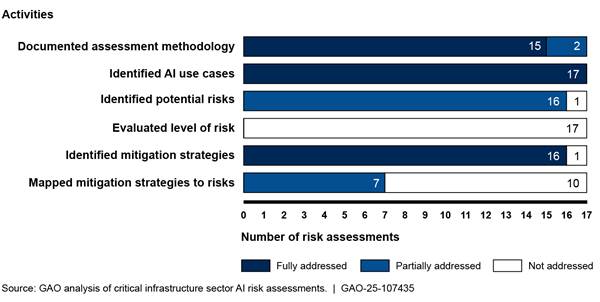

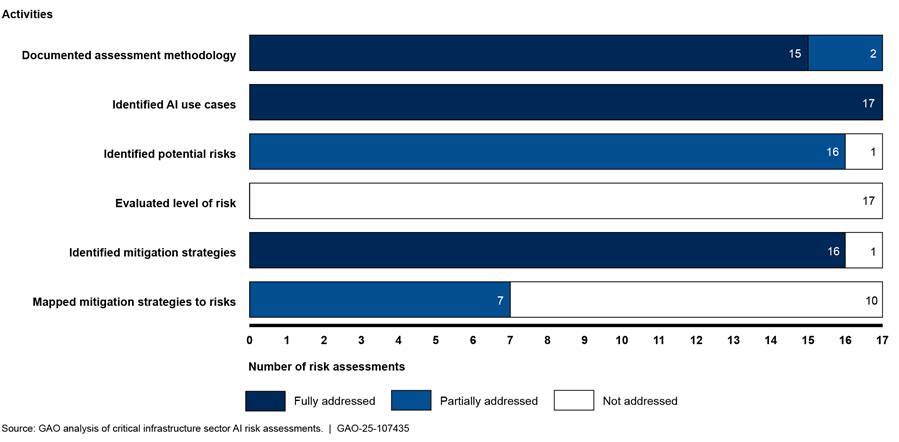

Federal agencies with a lead role in protecting the nation’s critical infrastructure sectors are referred to as sector risk management agencies. These agencies, in coordination with the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), were required to develop and submit initial risk assessments for each of the critical infrastructure sectors to DHS by January 2024. Although the agencies submitted the sector risk assessments to DHS as required, none fully addressed the six activities that establish a foundation for effective risk assessment and mitigation of potential artificial intelligence (AI) risks. For example, while all assessments identified AI use cases, such as monitoring and enhancing digital and physical surveillance, most did not fully identify potential risks, including the likelihood of a risk occurring. None of the assessments fully evaluated the level of risk in that they did not include a measurement that reflected both the magnitude of harm (level of impact) and the probability of an event occurring (likelihood of occurrence). Further, no agencies fully mapped mitigation strategies to risks because the level of risk was not evaluated.

Extent to Which the Sector Risk Management Agencies (SRMA) Have Addressed Six Activities in Their Sector Risk Assessments of Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Lead agencies provided several reasons for their mixed progress, including being provided only 90 days to complete their initial assessments. A key contributing factor was that DHS’s initial guidance to agencies on preparing the risk assessments did not fully address all the above activities.

DHS and CISA have made various improvements, including issuing new guidance and a revised risk assessment template in August 2024. The template addresses some—but not all—of the gaps that GAO found. Specifically, the new template does not fully address the activities for identifying potential risks including the likelihood of a risk occurring. CISA officials stated that the agency plans to further update its guidance in November 2024 to address the remaining gaps. Doing so expeditiously would enable lead agencies to use the updated guidance for their required January 2025 AI risk assessments.

Abbreviations

|

AI |

artificial intelligence |

|

CISA |

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency |

|

DHS |

Department of Homeland Security |

|

DOD |

Department of Defense |

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

DOT |

Department of Transportation |

|

EPA |

Environmental Protection Agency |

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

FPS |

Federal Protective Service |

|

GSA |

General Services Administration |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

NSM |

National Security Memorandum |

|

SCC |

sector coordinating council |

|

SRMA |

sector risk management agency |

|

Treasury |

Department of the Treasury |

|

TSA |

Transportation Security Administration |

|

USCG |

United States Coast Guard |

|

USDA |

Department of Agriculture |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

December 18, 2024

Congressional Addressees

Critical infrastructure provides the essential functions––such as supplying water, generating energy, and producing food––that underpin American society.[1] Disruption or destruction of this infrastructure could have debilitating effects on the nation’s safety, security, and economic well-being. Recent events demonstrate that threats to this infrastructure are varied and constantly changing, and cybersecurity has emerged as one of the most significant among them. For example, federal agencies and international partners issued an advisory in February 2024 stating that Chinese-sponsored cyber actors were seeking to preposition themselves on critical infrastructure technology systems to carry out cyberattacks in the event of a major crisis or conflict with the U.S.[2]

Our ongoing high-risk series, which serves to identify and help resolve serious weaknesses in government operations, has highlighted cybersecurity threats to critical infrastructure.[3] Further, as we have previously reported, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) could allow attackers to conduct cyberattacks more effectively.[4]

According to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), AI also has the potential to deliver transformative solutions for U.S. critical infrastructure, including improvements to cybersecurity. In October 2023, the President issued Executive Order 14110 to address the safe and responsible development and use of AI.[5] According to the Executive Order, AI is a machine-based system that can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, make predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing real or virtual environments.

Executive Order 14110 required the nation’s sector risk management agencies (SRMA) to evaluate and report on potential AI risks to critical infrastructure sectors, including ways to mitigate these risks.[6] These agencies, in coordination with DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), were required to submit an assessment of risks related to the use of AI in critical infrastructure sectors to DHS within 90 days of issuance (by January 29, 2024) and annually thereafter.[7]

We performed our work under the authority of the Comptroller General to initiate work to evaluate the results of a program or activity the government carries out under existing law, in this case the risk assessments required by the Executive Order.[8] Specifically, our objective was to determine the extent to which the SRMAs have evaluated potential risks and developed mitigation strategies to address the identified risks related to the use of AI in the critical infrastructure sectors.

To address this objective, we reviewed federal policies and guidance related to evaluating AI risks and performing risk assessments, issued by the White House and by agencies such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and DHS.[9] We also reviewed previous GAO work on assessing AI implementation at federal agencies.[10] These materials included best practices for assessing IT risks and mitigation strategies, AI risks, and risks related to critical infrastructure sectors. From our review, we analyzed each federal policy and guidance to identify applicable activities that were in scope of our review. We selected six key activities. These activities ensure that an AI risk assessment contains

1. documentation of the assessment methodology,

2. identification of the uses of AI in the sector,

3. identification of the potential risks associated with the uses of AI (to include threats, vulnerabilities, likelihood of occurrence, and level of impact),[11]

4. evaluation of the level of risk,[12]

5. identification of mitigation strategies, and

6. mapping of mitigation strategies to risks.

We determined that the six selected activities are foundational and establish a framework for assessing the risks and mitigation strategies of AI usage in critical infrastructure sectors. We validated this framework with internal and external subject matter experts, such as DHS.

We analyzed all 17 AI risk assessments submitted by the nine SRMAs in response to Executive Order 14110 against the activities we selected. The risk assessments addressed 16 critical infrastructure sectors and one subsector.[13] We considered a selected activity fully addressed if the SRMA’s risk assessment addressed all elements of that activity. We considered a selected activity partially addressed if the SRMA’s risk assessment addressed one or more elements of the activity, but not all of them. Finally, we considered a selected activity as not addressed if the SRMA’s risk assessment did not address any of the elements of the activity. Given the potential sensitivity of the information contained in the risk assessments, this report does not identify the SRMAs or sectors associated with specific findings.

We also administered a structured questionnaire to the relevant Sector Coordinating Councils (SCC), which are comprised of private sector stakeholders, to describe coordination between the SRMAs and the sectors.[14] We interviewed relevant officials to obtain information about the risk assessment process, challenges encountered, limitations identified, and plans for future work.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to December 2024 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objective.

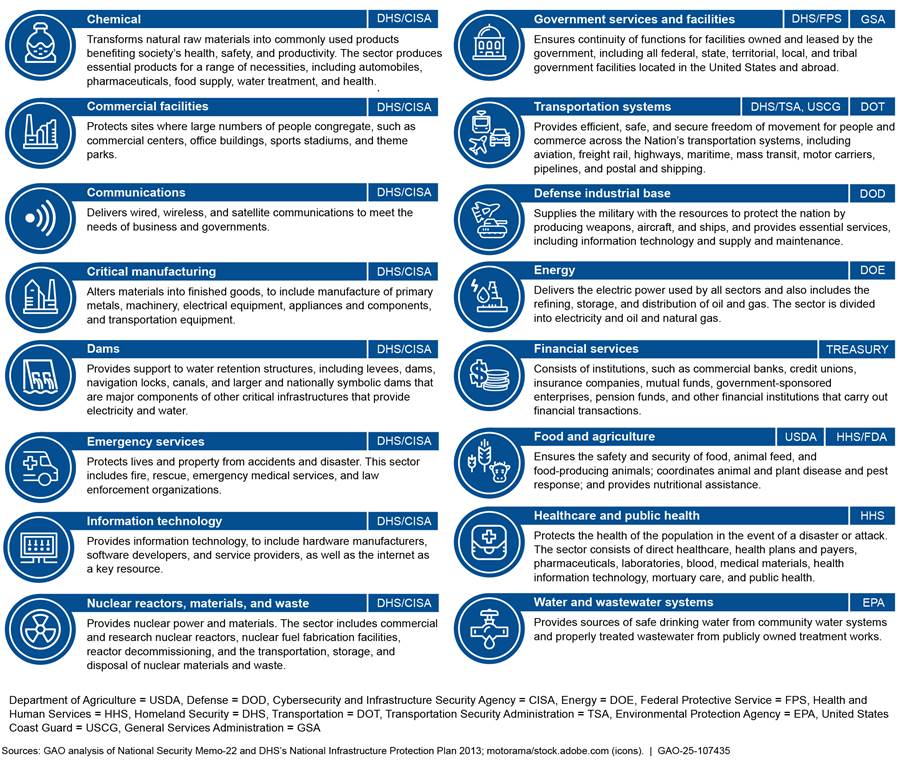

Background

The nation’s critical infrastructure is categorized into 16 sectors with at least one federal agency designated as the lead SRMA for the sector.[15] SRMAs serve as the day-to-day federal interface for the prioritization and coordination of sector-specific risk management and resilience activities within their respective sectors. SRMAs coordinate with the federal cross-sector lead for risk management and resilience activities, DHS’s CISA, to provide specialized expertise to critical infrastructure owners within the relevant sector and support programs and associated activities of their sector. SRMA responsibilities include coordination with CISA to conduct risk assessments and other tasks. Figure 1 shows these critical infrastructure sectors and the SRMAs responsible for leading them.

Figure 1: The 16 Critical Infrastructure Sectors and Their Respective Sector Risk Management Agencies

Note: Some sectors have co-lead agencies in which more than one agency shares leadership responsibilities. The Elections Infrastructure Subsector is part of the Government Services and Facilities Sector.

SRMAs Are Directed by Federal Laws, Policies, and Guidance

Various statutes and national-level plans and strategies provide guidance and direction for the SRMAs. These laws, policies, and guidance include the following:

2013 National Infrastructure Protection Plan. Issued in December 2013, the National Infrastructure Protection Plan details federal roles and responsibilities in protecting the nation’s critical infrastructure and how sector stakeholders should use risk management principles to prioritize protection activities within and across sectors.[16] It emphasizes the importance of collaboration, partnerships, and voluntary information sharing among DHS; SRMAs; industry owners and operators; and state, local, and tribal governments. Under this partnership, designated federal agencies serve as the lead coordinators for the security programs of their respective sectors.

Fiscal Year 2021 National Defense Authorization Act. Enacted in January 2021, this act amended the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish additional roles and responsibilities for the SRMAs in securing critical infrastructure.[17] For example, the act requires designated SRMAs to provide specialized expertise, assess risks to the sector, and support risk management of their respective critical infrastructure sectors.

Executive Order 14110. Issued in October 2023, the Executive Order required the SRMAs to evaluate and report on potential AI risks to critical infrastructure sectors.[18] The SRMAs were required to develop these risk assessments in coordination with CISA for the consideration of cross-sector risks and submit them to DHS within 90 days of enactment by January 29, 2024, and annually thereafter.

National Security Memorandum on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience (NSM-22). Issued in April 2024, this memorandum updated national principles and objectives related to strengthening U.S. critical infrastructure security and resilience.[19] These principles include advancing security and resilience through a risk-based approach, establishing and implementing minimum requirements for risk management, and leveraging expertise and technical resources from relevant federal departments and agencies to manage sector-specific risks. NSM-22 affirmed the 16 critical infrastructure sector designations and the SRMAs for each sector. It also established CISA as the National Coordinator for Security and Resilience of Critical Infrastructure and required the Secretary of Homeland Security to prepare a biennial National Infrastructure Risk Management Plan.[20]

Advancing the Responsible Acquisition of Artificial Intelligence in Government. Issued in September 2024, this memorandum directs agencies to improve their capacity for the responsible acquisition of AI.[21] This guidance requires executive branch agencies to share information on the acquisition of AI, implement risk management practices for rights-impacting and safety-impacting AI, and encourage competition among AI vendors.

Federal Guidance for Identifying and Mitigating AI Risks

We have previously reported that AI is a transformative technology with applications in medicine, agriculture, manufacturing, transportation, defense, and many other critical infrastructure sectors. We noted that, while it holds substantial promise for improving operations, it also poses unique challenges, many of which may be unknown or unforeseen at this time.[22] NIST and CISA have issued federal guidance and policies related to assessing and mitigating risks, including AI risks:

Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments. In September 2012, NIST published guidance for conducting risk assessments of federal information systems and organizations.[23]

Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework. In January 2023, NIST developed a voluntary framework for all organizations and operators involved in AI, such as AI designers, auditors, executives, and governance experts, for the deployment, use, verification, and management of AI-related risks.[24] According to NIST, without proper controls, AI systems can amplify, perpetuate, or exacerbate inequitable or undesirable outcomes for individuals and communities. With proper controls, AI systems can mitigate and manage inequitable outcomes.[25]

Assessment of Potential Risks Related to the Use of Artificial Intelligence. In December 2023, CISA provided this template to the SRMAs for consideration in preparing their AI risk assessments.[26] The template included a preliminary set of AI risk categories as well as sections for SRMAs to document their sector’s risk assessment methodology, uses of AI and risks in the sector, and mitigation strategies.

Artificial Intelligence Risk Categories and Mitigation Strategies for Critical Infrastructure. In December 2023, CISA’s National Risk Management Center[27] issued this guidance,[28] which included a preliminary set of AI risk categories:

· Attacks using AI. The use of AI to automate, enhance, plan, or scale physical or cyberattacks on critical infrastructure, for example by using AI to conduct social engineering attacks that trick people into revealing sensitive information about critical infrastructure or taking actions that compromise its security.

· Attacks targeting AI systems. Attacks targeting AI systems supporting critical infrastructure, for instance by manipulating these systems into acting in ways that are harmful to critical infrastructure.

· Failures in AI design and implementation. Deficiencies or inadequacies in the planning, structure, implementation, or execution of AI that cause malfunctions or unintended behavior harmful to critical infrastructure.

SRMAs' Initial AI Risk Assessments Did Not Incorporate All Aspects of Risk Identification and Mitigation

As previously established, Executive Order 14110 required SRMAs to evaluate potential risks related to the use of AI in critical infrastructure sectors and identify ways to mitigate these risks. Risk assessments, such as those required in the Executive Order, should include key activities identified in federal guidance. Implementing these activities is critical to adequately assessing and mitigating AI risks to critical infrastructure sectors to protect the sectors from a range of vulnerabilities and threats. Table 1 identifies selected activities and key factors from federal policies and guidance for evaluating and mitigating potential AI risks in critical infrastructure sectors.

Table 1: Selected Activities for Assessing Potential Artificial Intelligence (AI) Risks and Mitigation Strategies in Critical Infrastructure Sectors

|

Activity / Key factor |

Description |

|

1. Documented the assessment methodology |

The risk assessment documented the methodology used to assess risks, including the purpose and scope of the review, sources of information used, the analytical approach, and defined constraints or assumptions of the assessment, as applicable. |

|

2. Identified the uses of AI in the sector |

The risk assessment identified the potential or actual uses of AI relevant to the sector’s critical infrastructure. |

|

3. Identified the potential risks associated with the uses of AI |

The risk assessment documented the potential risks related to the use of AI in the sector, to include the key factors of risk (i.e., threats, vulnerabilities, likelihood of occurrence, and level of impact). |

|

4. Evaluated the level of risk associated with the uses of AI |

The risk assessment documented the level of risk, which refers to a measure of an event’s probability of occurring and the magnitude or degree of the consequences of the corresponding event. To evaluate the level of risk, both the likelihood of occurrence and the level of impact need to be identified. |

|

5. Identified mitigation strategies |

The risk assessment documented mitigation strategies. |

|

6. Mapped mitigation strategies to risks |

The risk assessment documented the risks that the mitigation strategies are intended to help address. |

Source: GAO analysis of federal policy and guidance. | GAO‑25‑107435

SRMAs took steps to evaluate potential risks and develop mitigation strategies as called for in federal policy and guidance. However, none fully addressed the six selected activities for evaluating and mitigating potential AI risks in their sector risk assessments. Figure 2 shows the SRMAs’ implementation of the six activities for the 17 critical infrastructure sector risk assessments.[29] A more detailed discussion of the findings related to each activity follows the figure.[30]

Figure 2: Extent to Which Sector Risk Management Agencies (SRMA) Have Addressed the Selected Activities for the 17 Critical Infrastructure Sector Artificial Intelligence (AI) Risk Assessments

Fully Addressed – The SRMA addressed all elements of the activity or key factor.

Partially addressed – The SRMA addressed one or more of the elements of the activity or key factor, not all of them.

Not addressed – The SRMA did not address any of the elements of the activity or key factor.

Note: “Identified potential risks” includes the key factors of threats, vulnerabilities, likelihood of occurrence, and level of impact.

Documented assessment methodology. Fifteen of the 17 sector risk assessments fully addressed this activity. For example, the risk assessments included the purpose (e.g., responding to Executive Order 14110); described the analytical approach for developing the assessment (e.g. literature reviews and stakeholder coordination[31]); and identified sources (e.g., DHS’s AI Risk Categories and Mitigation Strategies guidance). Two of the risk assessments partially addressed this activity. For example, one risk assessment included the purpose, scope, analytical approach, but did not note sources of the information it used or defined constraints within the assessment.

Identified AI use cases. All 17 sector risk assessments fully addressed this activity. For example, one risk assessment noted that AI is currently used to ensure infrastructure safety, identify operational efficiencies, and support decision-making. The risk assessment also noted that AI could be used in the future for monitoring infrastructure, augmenting the cybersecurity of facilities, and enhancing digital and physical surveillance.

Identified potential risks. Sixteen of the 17 sector risk assessments partially addressed this activity. Specifically, most of the risk assessments identified threats, vulnerabilities, and level of impact, which are needed to identify potential risks within the sector. However, except for one sector risk assessment, none of the other assessments identified the likelihood of occurrence, which is the probability that a given threat is capable of exploiting a given vulnerability. One sector risk assessment did not address this activity.

Evaluate level of risk.[32] None of the 17 sector risk assessments fully addressed this activity. Specifically, the risk assessments did not include a measurement of both the magnitude of harm (level of impact) and the probability of an event occurring (likelihood of occurrence).

Identified mitigation strategies. Sixteen of the 17 sector risk assessments fully addressed this activity. For example, one risk assessment identified mitigation strategies regarding the risk of AI use within the sector. These included testing and validation of AI systems and incorporation of redundancy, or fail-safe, systems in addition to kill-switch mechanisms that would be used in the event an AI system is compromised. Another risk assessment identified strategies such as employing risk management models applicable to AI-related risks and tracking the data sources that feed into AI models to ensure that data has not been compromised. One sector risk assessment did not address this activity.

Mapped Mitigation Strategies to Risks. Seven of the 17 sector risk assessments partially addressed this activity; however, 10 did not address this activity. For example, one risk assessment identified risks associated with using AI to enhance the process of configuring, managing, testing, deploying, and operating physical and virtual network infrastructure and stated that there are multiple strategies aimed at ensuring network reliability and redundancy. However, the risk assessment did not state what the strategies are. Another risk assessment identified mitigation strategies for risks created by attacks using AI but did not link mitigation strategies to the specified risks. A contributing factor for agencies not fully addressing this activity is that they had not yet evaluated the level of risk.

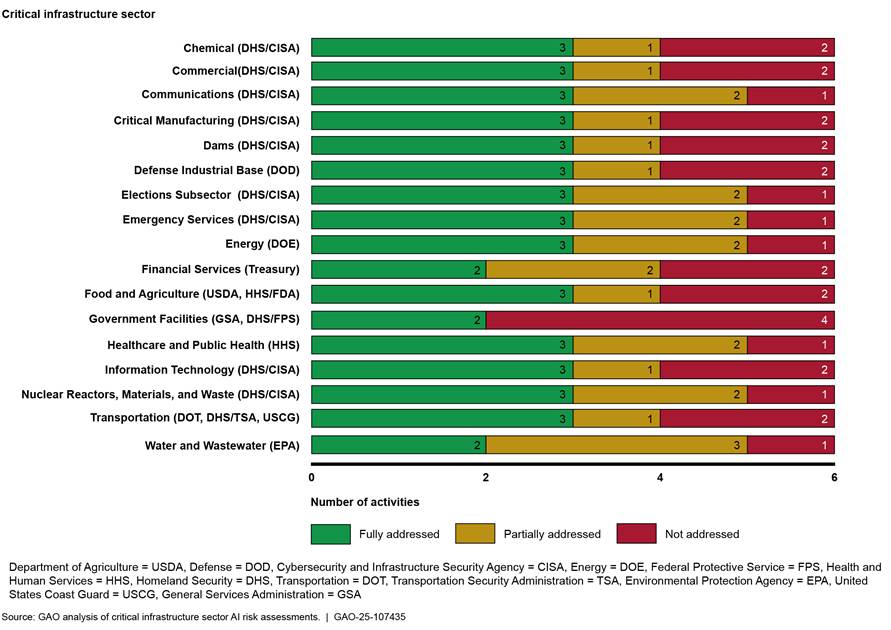

Figure 3 provides an overview of implementation of the six activities for each critical infrastructure sector. There are 16 critical infrastructure sectors and one sub-sector.

Figure 3: Implementation of the Six Artificial Intelligence Risk Assessment Activities for Each Critical Infrastructure Sector and One Subsector

Several Reasons Accounted for SRMAs’ Mixed Progress

SRMAs provided several reasons for their mixed progress in addressing the selected activities for assessing and mitigating potential AI risks in critical infrastructure sectors.

Short time frame. SRMAs stated that the 90-day time period set forth in the Executive Order was a significant challenge for completing the assessments submitted in January 2024.

Evolving nature of AI. Most SRMAs noted that identifying AI use cases was difficult because of the rapid evolution of uses and a lack of data on uses and risks in the sectors. CISA officials stated that both AI technology and its applications by critical infrastructure are constantly evolving. As a result, officials stated that they focused primarily on identifying use cases for AI and identifying risk information relevant to those specific use cases. Further, CISA officials stated that, because the technology is still emerging, there was—and may continue to be—limited historical data and use cases within the sectors to better inform the risk assessments. We previously reported that AI is evolving at a pace at which we cannot afford to be reactive to its complexities and potential risks.[33]

Incomplete guidance. Another contributing factor was that DHS guidance did not fully address the activities needed for assessing and mitigating potential AI risks. Most SRMAs stated that they followed DHS’s November 2023 guidance and template in preparing the risk assessments.[34] However, the 2023 DHS guidance and template did not include identifying potential risks to include the likelihood of occurrence, evaluating the level of risk associated with use cases of AI, and mapping the mitigation steps to the identified risks. CISA officials acknowledged areas for improvement moving forward.

DHS and CISA Improved the Process for Annual AI Risk Assessments, but More Remains to Be Done

DHS and CISA have since made various improvements as part of the annual refresh process for the AI risk assessments. Specifically, in April 2024, DHS issued safety and security guidelines entitled Mitigating Artificial Intelligence Risk: Safety and Security Guidelines for Critical Infrastructure Owners and Operators in response to Executive Order 14110.[35] The guidelines provide insights learned from CISA’s cross-sector analysis of sector-specific AI risk assessments SRMAs completed in January 2024. The CISA analysis includes a profile of cross-sector AI use cases and patterns in adoption. DHS drew upon this analysis, as well as analysis from existing U.S. government policy, to develop specific safety and security guidelines— which critical infrastructure owners and operators can follow—for mitigating cross-sector AI risks to critical infrastructure.[36] These guidelines also included beneficial uses for AI, which are discussed in appendix I.

Further, in May 2024, CISA officials briefed the SRMAs on preliminary requirements, tentative dates, and timelines for the 2025 AI sector risk assessments. In July 2024, CISA held two workshops with the SRMAs to discuss updated guidance on AI risk categories and mitigations. In August 2024, CISA updated and issued new guidance, including a risk assessment template, to all the SRMAs that addresses most of the gaps we found. The updated template included enhancements in areas such as

· risk categories on attacks against AI, attacks using AI, and design implementation failures;

· defining the specific threats, vulnerabilities, consequences, and potential mitigations;

· characterizing sector specific consequences and cross-sector risks;

· mapping of mitigation strategies to specific use cases; and

· assessing the quantitative aspect of the risks, such as incorporating percentages or rankings.

While CISA has made enhancements to its guidance, the template does not address all of the gaps we found. Specifically, the updated template does not fully address the activities for identifying potential risks to include likelihood of occurrence and evaluating the level of risk associated with AI.

CISA officials stated that in November 2024 the agency plans to hold a workshop for CISA-led sectors and issue and share new guidance that would continue to address some of the gaps we identified. However, the agency did not state if it plans to share the enhancements to its guidance with all the SRMAs to improve their future risk assessments or only with the CISA-led sectors.

According to CISA officials, DHS’s Roles and Responsibilities Framework for Artificial Intelligence in Critical Infrastructure (framework), issued in November 2024, addresses level of impact but not the likelihood of occurrence.[37] By not addressing the likelihood of occurrence, the guidance, including subsequent updates to the template, will not address all the gaps associated with identifying potential risks and evaluating the level of risk. Officials also noted that this framework will provide specific recommended safety and security practices for critical infrastructure owners and operators. In moving forward, CISA officials noted that their goal is to be flexible and improve the risk assessments to keep up with emerging technologies involving AI.

Updating the guidance and template expeditiously to address the gaps we found, and sharing these updates with SRMAs, would enable the SRMAs to use the updated guidance for their required January 2025 AI risk assessments. Not doing so could lead to SRMA’s assessments not comprehensively addressing all the potential risks AI poses. Thus, their efforts to proactively prepare for AI complexities as well as potential benefits and risks will be impaired. Further, not sharing the updates with all the SRMAs could lead to the introduction of vulnerabilities into critical infrastructure, with severe consequences for our national security, health, and safety.

Conclusions

AI technologies could allow critical infrastructure owners and operators to improve operations and protect their systems. However, the use of AI could also lead to unexpected or harmful behavior that disrupts critical infrastructure operations or vulnerabilities that adversaries could exploit to do the same. SRMAs took an important step by developing initial sector risk assessments in a complex and evolving environment. However, the assessments did not address several key activities, such as evaluating the level of risk and the likelihood that a risk will occur.

Part of the reason for these gaps was lack of complete guidance and templates. DHS has updated its guidance in recent months, but gaps still remain. By updating its guidance and template expeditiously to include these key activities, SRMAs would have the information necessary to inform their January 2025 AI risk assessments and shape the mitigation efforts necessary to address AI risks to critical infrastructure. This would also ensure that SRMAs prepare risk assessments that contain complete information, which would improve DHS’s ability to address the cross-sector risks to critical infrastructure associated with AI. Doing so will also equip sectors with approaches that increase the trustworthiness of AI systems and help foster the responsible design, development, deployment, and use of AI systems over time.

Recommendation for Executive Action

We are making the following recommendation to DHS:

The Secretary of Homeland Security should expeditiously update its guidance and template for AI risk assessments to address the gaps identified in this report, including activities such as identifying potential risks and evaluating the level of risk, and ensure that the updates are shared with all the SRMAs.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to the Department of Homeland Security and the eight other SRMAs (the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, Health and Human Services, Transportation, and the Treasury; and the Environmental Protection Agency and General Services Administration) for their review and comment. The Department of Homeland Security, to which we made a recommendation, agreed with the recommendation, as summarized below. We also received responses from the other eight agencies.

In written comments, reprinted in appendix II, the Department of Homeland Security agreed with our recommendation and, among other things, noted that it remains committed to enhancing the understanding of the risks associated with AI across critical infrastructure and to working with the SRMAs to identify strategies to mitigate potential AI risks. It also noted that the resources it issued to date, including the August 2024 guidance and template, will help facilitate the completion of the second round of sector-specific AI risk assessments by the end of January 2025.

Additionally, the department noted that it plans to provide SRMAs with additional guidance that will address the activities for identifying potential risks, mitigation strategies, and evaluating the level of risk. The estimated completion date for the guidance is March 31, 2025. The department also provided technical comments, which we addressed as appropriate.

In addition to DHS, the other eight agencies responded as follows. In written comments, reprinted in appendix III, the Department of Defense agreed with our report and provided a technical comment in a separate document, which we addressed as appropriate. Additionally, three agencies stated that they had no comments (the Departments of Agriculture, Health and Human Services, and the Environmental Protection Agency) and four provided technical comments (the Departments of Energy, Treasury, Transportation, and the General Services Administration), which we addressed as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees; the Secretaries of the Departments of Homeland Security, Agriculture, Defense, Energy, Health and Human Services, Transportation, and the Treasury; the Administrators of the Environmental Protection Agency and General Services Administration; and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any

questions regarding this report, our primary point of contact is David B.

Hinchman at (214) 777-5719 or hinchmand@gao.gov. You may also contact Tina Won Sherman at (202) 512-8461 or shermant@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional

Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO

staff who made major contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

David B. Hinchman

Director, Information Technology and Cybersecurity

Tina Won Sherman

Director, Homeland Security and Justice

List of Addressees

The Honorable Maria Cantwell

Chair

Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

United States Senate

The Honorable Gary C. Peters

Chair

United States Senate

The Honorable Bennie G. Thompson

Ranking Member

Committee on Homeland Security

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jamie Raskin

Ranking Member

Committee on Oversight and Accountability

House of Representatives

The Honorable Anna G. Eshoo

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Health

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Bill Foster

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Monetary Policy

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

The Honorable Nancy Mace

Chairwoman

The Honorable Gerald E. Connolly

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Information Technology, and Government

Innovation

Committee on Oversight and Accountability

House of Representatives

The Honorable Jay Obernolte

Chair

The Honorable Valerie P. Foushee

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Investigations and Oversight

Committee on Science, Space, and Technology

House of Representatives

The Honorable Donald S. Beyer, Jr.

House of Representatives

The Honorable Ted W. Lieu

House of Representatives

The Honorable Richard McCormick

House of Representatives

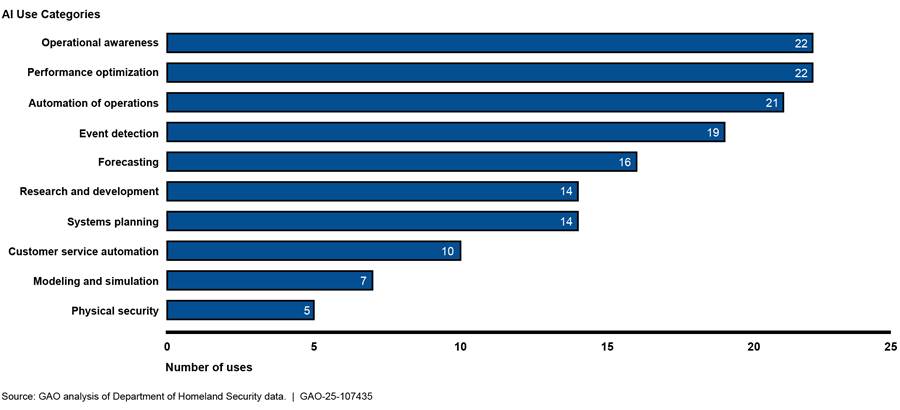

In April 2024, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued safety and security guidelines, which critical infrastructure owners and operators can follow to mitigate artificial intelligence (AI) risks.[38] These guidelines included 10 categories that describe the beneficial uses of AI.

· Operational awareness. Gaining a clearer understanding of critical infrastructure operations.

· Performance optimization. Improving efficiency and effectiveness, for instance by using AI to optimize supply chains.

· Automation of operations. Automating routine tasks and processes, such as data entry.

· Event detection. Detecting events or changes in systems or the environment, such as unusual heart rates.

· Forecasting. Predicting future trends or events based on current and historical data, such as sales projections.

· Research and development. Developing new products, services, or technologies.

· Systems planning. Planning and design of new systems, such as information technology infrastructure.

· Customer service automation. Automating customer service activities such as answering frequently asked questions.

· Modeling and simulation. Creating models and simulations of real-life scenarios, such as automobile traffic.

· Physical security. Maintaining the physical security of a facility or area, such as the use of surveillance systems.

According to DHS, the sector risk management agencies (SRMA) identified more than 150 beneficial uses of AI in their risk assessments. As shown in Figure 4, some of these beneficial uses of AI identified by the SRMAs are more prevalent than others.

According to DHS, these categories in the guidelines are likely to evolve in the future as the use of AI for more complex tasks by critical infrastructure owners and operators increases. Further, these DHS guidelines included findings from the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s (CISA) cross-sector review of the SRMA AI risk assessments. For example, SRMAs:

· consistently highlighted the possibilities of AI as a transformative technology for many critical infrastructure functions, but they also noted the tension between the benefits of AI and the risks introduced by a complex and rapidly evolving technology.

· reported their sectors have adopted AI primarily to support functions that were already partially automated, and they envision the application of AI to more complex functions as a future advancement.

· noted the possibility that AI could support solutions for many long-standing, persistent challenges, such as logistics, supply chain management, quality control, physical security, and cyber defense.

· consistently viewed AI as a potential means for adversaries to expand and enhance current cyber tactics, techniques, and procedures; and

· identified the following methods to manage and reduce risk to critical infrastructure operations:

· Established risk mitigation best practices, such as information and communications technology supply chain risk management, incident response planning, ongoing workforce development, including awareness and training; and

· Mitigation strategies more specific to AI, such as dataset and model validation, human monitoring of automated processes, and AI use policies.

DHS noted that as individuals and organizations develop new AI systems and use cases, and as corresponding risks and mitigations evolve, DHS plans to update these guidelines and consider developing additional resources that support critical infrastructure owners and operators in navigating the new opportunities and risks that advances in AI technologies bring in the future.

GAO Contacts

David B. Hinchman, (214) 777-5719 or hinchmand@gao.gov

Tina Won Sherman, (202) 512-8461 or shermant@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contacts listed above, the following staff made significant contributions to this report: Neela Lakhmani (Assistant Director), Ben Atwater (Assistant Director), David Hong (Analyst-in-Charge), Scott Borre, Jillian Clouse, Christopher Cooper, Kristi Dorsey, Rebecca Eyler, Peter Haderlein, Smith Julmisse, Jess Lionne, Claire McLellan, Sachin Mirajkar, Claire Saint-Rossy, and Andrew Stavisky.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, X, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7700

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, ClowersA@gao.gov, (202) 512-4400, U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125, Washington, DC 20548

Public Affairs

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, KaczmarekS@gao.gov, (202) 512-4800, U.S.

Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

Strategic Planning and External Liaison

Stephen J. Sanford, Managing

Director, spel@gao.gov, (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814, Washington,

DC 20548

[1]The term “critical infrastructure” refers to systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, so vital to the United States that their incapacity or destruction would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination of these matters. 42 U.S.C. § 5195c(e). Federal policy identifies 16 critical infrastructures: chemical; commercial facilities; communications; critical manufacturing; dams; defense industrial base; emergency services; energy; financial services; food and agriculture; government facilities; health care and public health; information technology; nuclear reactors, materials, and waste; transportation systems; and water and wastewater systems.

[2]Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Cybersecurity Advisory: PRC [People’s Republic of China] State-Sponsored Actors Compromise and Maintain Persistent Access to U.S. Critical Infrastructure, AA24-038A (February 2024).

[3]Protecting the cybersecurity of critical infrastructure has been part of GAO’s high-risk list since 2003. We continue to identify the cybersecurity of critical infrastructure as a component of the cybersecurity high-risk area, as reflected in our high-risk updates on major cybersecurity challenges. See GAO, High-Risk Series: Efforts Made to Achieve Progress Need to Be Maintained and Expanded to Fully Address All Areas, GAO‑23‑106203 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 20, 2023).

[4]GAO, Critical Infrastructure: EPA Urgently Needs a Strategy to Address Cybersecurity Risks to Water and Wastewater Systems, GAO‑24‑106744, (Washington, D.C.: Aug.1, 2024).

[5]Exec. Order 14110, Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (Oct. 30, 2023).

[6]Exec. Order 14110, Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (Oct. 30, 2023). Federal agencies with a lead role in assisting and protecting one or more of the nation’s 16 critical infrastructures are referred to as sector risk management agencies. SRMAs are federal departments or agencies, designated by law or presidential directive, with specific responsibilities for their designated critical infrastructure sectors. See 6 U.S.C. § 651(5). The nine SRMAs are the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Transportation, and the Treasury; the General Services Administration; and the Environmental Protection Agency. The Department of Homeland Security is a co-SRMA for multiple sectors.

[7]Established by the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency Act of 2018, CISA is responsible for coordinating national efforts to secure and protect against critical infrastructure risks. The act renamed the Department of Homeland Security’s National Protection and Programs Directorate as CISA and specified CISA’s responsibilities. See Pub. L. No. 115-278, §2201(4), 132 Stat. 4168, (2018) (codified at 6 U.S.C. § 652).

[8]31 U.S.C. § 717(b)(1).

[9]Exec. Order 14110, Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (Oct.30, 2023); White House, National Security Memorandum on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience, National Security Memorandum 22 (NSM-22) (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 30, 2024); NIST, Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments, SP 800-30 (Gaithersburg, MD: September 2012); NIST, Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1 (Gaithersburg, MD: Apr. 16, 2018); and NIST, Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) (Gaithersburg, MD: Jan. 26, 2023); DHS, Supplemental Tool: Executing A Critical Infrastructure Risk Management Approach (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 17, 2020) and National Infrastructure Protection Plan 2013: Partnering for Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience (Washington, D.C.: Feb. 12, 2013).

[10]GAO, Artificial Intelligence: An Accountability Framework for Federal Agencies and Other Entities, GAO‑21‑519SP (Washington, D.C.: June 30, 2021).

[11]To identify potential risks, a risk assessment should document four key factors: threats (circumstances or events with the potential to adversely impact organizational operations and assets, individuals, other organizations, or the nation); vulnerabilities (a weakness in an information system, security protocols, internal controls, or implementation that can be exploited by a threat source); likelihood of occurrence (the probability that a given threat is capable of exploiting a given vulnerability); and level of impact (the magnitude of harm expected to result from consequences of unauthorized disclosure of information, unauthorized modification of information, unauthorized destruction of information, or loss of information or information system availability).

[12]To evaluate the level of risk, both the likelihood of occurrence and the level of impact need to be identified since it is the measure of an event’s probability of occurring and the magnitude or degree of the consequences of the corresponding event.

[13]The Elections Infrastructure Subsector, which is part of the Government Services and Facilities Sector, submitted a separate risk assessment. This subsector includes voter registration databases, voting systems, and polling places.

[14]Sector coordinating councils are self-organized, self-run, and self-governed private sector councils that interact on a wide range of sector-specific strategies, policies, and activities. Membership on the councils can vary from sector to sector but is meant to represent a broad base of stakeholders, including owners, operators, associations, and other entities within the sector. All the sectors have at least one sector coordinating council.

[15]Presidential Policy Directive-21 (PPD-21) previously called these agencies Sector-Specific Agencies. The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021 codified Sector-Specific Agencies as SRMAs. In 2013, PPD-21 categorized the nation’s critical infrastructure into 16 sectors with at least one federal agency designated as SRMA for the sector, although the number of sectors and SRMA assignments are subject to review and modification. Those designations are still in effect. See 6 U.S.C. § 652a(b).

[16]DHS, National Infrastructure Protection Plan 2013.

[17]National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2021, Pub. L. No. 116-283, § 9002, 134 Stat. 4768 (2021).

[18]Exec. Order 14110, Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence (Oct. 30, 2023).

[19]NSM-22 rescinded and replaced Presidential Policy Directive-21, which previously guided national efforts to protect critical infrastructure. The White House, National Security Memorandum on Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience.

[20]In June 2024, DHS issued strategic guidance for improving the security and resilience of our nation's critical infrastructure, including priorities to guide shared efforts throughout the 2024-2025 national critical infrastructure risk management cycle established in NSM-22. For example, the guidance states that SRMAs are to manage the evolving risks and opportunities presented by AI and other emerging technologies. See DHS, Strategic Guidance and National Priorities for U.S. Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience (2024-2025) (Washington, D.C.: Jun. 14, 2024).

[21]Office of Management and Budget, Advancing the Responsible Acquisition of Artificial Intelligence in Government, M-24-18 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 24, 2024).

[23]NIST, Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments.

[24]NIST, Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0).

[25]In March 2024, the Office of Management and Budget issued guidance that requires executive branch agencies to establish new agency requirements and guidance for AI governance, innovation, and risk management. For example, it encourages agencies to continue developing their risk management policies in accordance with Executive Orders such as E.O. 14110 and best practices for AI risk management such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework. See, Office of Management and Budget, Advancing Governance, Innovation, and Risk Management for Agency Use of Artificial Intelligence, M-24-10 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 28, 2024).

[26]CISA, Assessment of Potential Risks Related to the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 2023).

[27]The National Risk Management Center is an office within CISA responsible for identifying significant risks to critical infrastructure and promoting risk reduction activities. According to CISA officials, in November 2023, CISA’s National Risk Management Center held a workshop with officials representing the SRMAs from each of the critical infrastructure sectors to discuss cross-sector risks. According to CISA, this workshop informed the development of guidance that was later shared with the SRMAs in December 2023. CISA, “Artificial Intelligence Workshop: NRMC and Sector Risk Management Agencies,” (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 6, 2023).

[28]CISA, Artificial Intelligence (AI) Risk Categories and Mitigation Strategies for Critical Infrastructure (Version 1.0), (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 2023).

[29]The risk assessments addressed 16 critical infrastructure sectors and one subsector. The Elections Infrastructure Subsector, which is part of the Government Services and Facilities Sector, submitted a separate risk assessment.

[30]As noted earlier, given the potential sensitivity of the information contained in the risk assessments, this report does not identify the SRMAs or sectors associated with our specific findings.

[31]In developing the risk assessments, nearly all of the SRMAs indicated that they solicited input from their respective SCCs. Almost all (17 of 18) SCCs responded that the SRMAs solicited input from their SCC on the risks associated with AI use in their sector.

[32]Level of risk refers to a measure of an event’s probability of occurring and the magnitude or degree of the consequences of the corresponding event.

[34]Specifically, DHS provided SRMAs with guidance documentation such as a template, AI Sector Specific Risk Assessment Template Version 1.0, and a document to assist in categorizing risks and mitigation strategies, AI Risk Categories and Mitigation Strategies Dec. 2023 v1.0. Further, as previously noted, CISA held an AI risk assessment workshop for SRMAs in November of 2023.

[35]Section 4.3(a)(iii) of Executive Order 14110 directs DHS as follows: “Within 180 days of the date of this order, the Secretary of Homeland Security, in coordination with the Secretary of Commerce and with SRMAs and other regulators as determined by the Secretary of Homeland Security, shall incorporate as appropriate the AI Risk Management Framework, NIST AI 100-1, as well as other appropriate security guidance, into relevant safety and security guidelines for use by critical infrastructure owners and operators.”

[36]DHS, Mitigating Artificial Intelligence (AI) Risk: Safety and Security Guidelines for Critical Infrastructure Owners and Operators (Washington, D.C.: April 26, 2024).

[37]DHS, Roles and Responsibilities Framework for Artificial Intelligence in Critical Infrastructure (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 14, 2024).

[38]Department of Homeland Security, Mitigating Artificial Intelligence (AI) Risk: Safety and Security Guidelines for Critical Infrastructure Owners and Operators (Washington, D.C.: April 26, 2024).