SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

Actions Needed to Address IT Acquisition Workforce Challenges

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to congressional committees.

For more information, contact: Mona Sehgal at sehgalm@gao.gov

What GAO Found

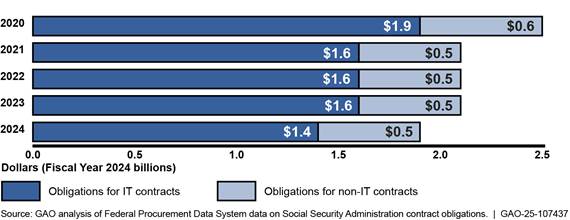

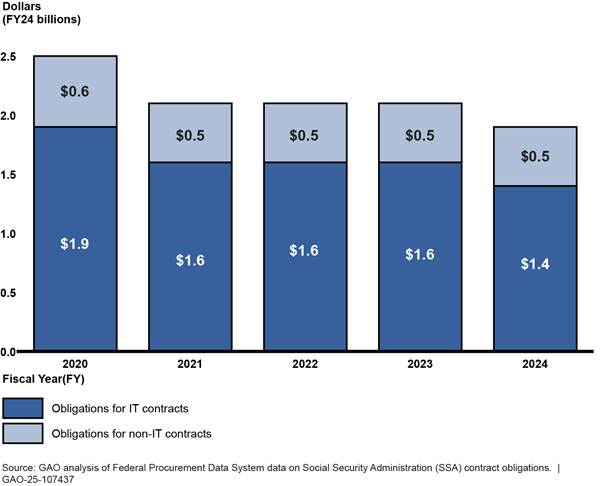

The Social Security Administration (SSA) relies on IT hardware and software to deliver services that touch the lives of virtually every American. From fiscal years 2020 through 2024, SSA obligated $1.4 billion or more annually on IT acquisitions.

SSA’s IT acquisition staff include contracting officers, who award and manage contracts, and contracting officer’s representatives, who assist contracting officers with contract administration functions. These staff reside in the Office of Acquisition and Grants and the Office of the Chief Information Officer, respectively, which face staffing and training challenges.

· Staffing. The Office of Acquisition and Grants has limited data on contracting officer workloads to inform staffing assessments. Similarly, the Office of the Chief Information Officer completed workload assessments for contracting officer’s representatives who support software contracts, but it has conducted limited assessments for those supporting hardware and service contracts. Executive orders and related guidance from early 2025 direct executive agencies, including SSA, to reduce their workforces and consolidate certain procurements at the General Services Administration. SSA is in the process of identifying changes to its IT acquisition workforce as of May 2025. To operate effectively in this changing environment, SSA needs quality workload information that accounts for complexity to ensure it can accurately assess and document its IT acquisition staffing needs to accomplish its future goals.

· Training. An SSA assessment found that senior-level contracting officers had deficiencies in acquisitions-related competencies. SSA officials said they are seeking trainings to address these deficiencies; however, SSA’s existing training plan has not been updated since 2019. Given the time since the last training plan update and ongoing organizational changes, it is not clear if SSA will prioritize implementing training to address these gaps. A training plan that addresses the acquisitions-related competency gaps identified for contracting officers, including those who support IT contracts, remains vital as it would help ensure that contracting officers have the skills to support SSA’s current and future IT contracting needs.

Why GAO Did This Study

SSA’s IT acquisition staff oversee how the agency buys and maintains technology resources. SSA, however, has experienced long-standing human capital and IT modernization planning challenges. These challenges preceded SSA’s efforts to reduce the size of its workforce and contractor and IT spending.

GAO was asked to review SSA’s workforce planning practices for staff who support IT contracts. This report examines SSA’s obligations for IT products and services from fiscal years 2020 to 2024; and the extent to which the Office of Acquisition and Grants and the Office of the Chief Information Officer assessed and addressed their IT acquisition workforce needs.

To conduct this work, GAO analyzed SSA’s contract obligation data for fiscal years 2020 to 2024 (the latest available information for a full fiscal year) and determined that the data were reliable. GAO also reviewed SSA guidance, data on contracting officer and contracting officer representative assignments, and a competency assessment report for contracting officers.

What GAO Recommends

GAO is making three recommendations to inform SSA’s decisions as the current reorganization unfolds, including that SSA assesses and documents contracting officer and contracting officer’s representative staffing needs based on quality workload information; and that it develops and implements a training plan to address identified acquisitions-related competency gaps for IT contracting officers. SSA concurred with the recommendations.

Abbreviations

COR Contracting Officer’s Representative

DIMES Division of Investment Management and Enterprise Services

DITA Division of Information Technology and Acquisition

DRMA Division of Resource Management and Acquisitions

FAR Federal Acquisition Regulation

IT Information Technology

OAG Office of Acquisitions and Grants

OCIO Office of the Chief Information Officer

SSA Social Security Administration

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

August 14, 2025

The Honorable Mike Crapo

Chair

The Honorable Ron Wyden

Ranking Member

Committee on Finance

United States Senate

The Honorable Ron Estes

Chair

The Honorable John B. Larson

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Social Security

Committee on Ways and Means

House of Representatives

The Social Security Administration (SSA) is responsible for delivering services that touch the lives of virtually every American. To provide these services, the agency relies on a variety of IT systems, ranging from those that support the processing and payment of Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income benefits to those that facilitate the calculation and withholding of Medicare premiums. The agency relies extensively on IT hardware and software to carry out its core mission. SSA’s acquisition workforce, which includes contracting officers and contracting officer’s representatives (COR), plays a key role in overseeing and managing IT acquisitions that support the agency.

We and others have reported on the challenges SSA has faced in modernizing its IT systems and planning for its human capital needs. In May 2014, we reported that SSA had not adequately planned for its long-term IT workforce needs.[1] In November 2023, SSA’s Office of the Inspector General reported that SSA did not have a clear human capital plan that addressed human capital risks, such as a large and expected retirement wave.[2] Similarly, in September 2024, SSA’s Office of the Inspector General reported that the agency’s IT modernization program was not effectively designed or, in some instances, had not implemented or complied with its own processes to fully address federal requirements.[3] For example, SSA did not have an approved strategy or guidance for defining and implementing plans to modernize, replace, or retire its legacy IT systems. Our June 2025 report also reviewed SSA’s IT investment management processes and made recommendations to improve these processes.[4]

In 2002, we reported that successful transformation of an organization’s acquisition environment included having the right people with the right skills.[5] Strategic human capital management has been a government-wide high-risk area since 2001 because skills gaps can undermine agencies’ abilities to effectively meet their missions.[6] These skills gaps can be due to an insufficient number of individuals or individuals without the appropriate skills or abilities to successfully perform their work. Government-wide skills gaps have been identified in fields such as IT and acquisitions. Agencies often experience skills gaps because of a shortfall in a talent management activity, such as workforce planning or training.

You asked us to review SSA’s workforce planning practices for staff who support IT contracts. This report examines (1) how much SSA obligated for IT products and services from fiscal years 2020 through 2024; and the extent to which (2) the Office of Acquisition and Grants (OAG) took steps to assess and address its needs for contracting officers who support IT contracts, and (3) the Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) took steps to assess and address its needs for contracting officer’s representatives who support IT contracts.

To examine how much SSA obligated for IT products and services, we analyzed SSA’s contract awards and contract obligation data from the Federal Procurement Data System for fiscal years 2020 through 2024. We reviewed contract obligations through fiscal year 2024 because it was the most recent full fiscal year for which data were available at the time of our review. To determine the reliability of these data, we reviewed the data dictionary and data validation rules for the system. We determined that the Federal Procurement Data System data were reliable for reporting SSA’s contract obligations and number of contracts from fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

To examine the extent to which OAG took steps to assess and address its workforce needs, we reviewed SSA’s acquisition handbook and training guidance for acquisition personnel, including contracting officers. We also reviewed OAG organizational charts and spreadsheets used to track contracting officer assignments. We assessed the reliability of these data by reviewing OAG’s processes for collecting this data and conducting manual data testing of contracting officer assignments, such as checking for missing values and duplicate entries. We found the data to be generally reliable to report the number of contracting officers as of November 2024. We described the types of information in OAG’s contracting officer workload spreadsheet but did not analyze the data. We determined these data were unreliable due to discrepancies in the number of contracts reported by OAG and OCIO, and duplicate entries in the spreadsheet for some contracts. We also interviewed key officials from OAG and its subcomponents.

To examine the extent to which OCIO took steps to assess and address its workforce needs, we reviewed spreadsheets on contracting officer’s representatives’ workloads, and documents outlining a streamlined software acquisition process. We assessed the reliability of OCIO’s spreadsheets by reviewing OCIO’s processes for collecting the data and conducting manual data testing of contract assignment data, including checking the summary data against totals provided by SSA. We describe the information in OCIO’s spreadsheets but did not analyze the data because we determined that the data on contracts assigned to contracting officer’s representatives were not reliable due to discrepancies in the number of contracts reported by OAG and OCIO. In addition, we interviewed key officials in relevant OCIO divisions.

We assessed OAG’s and OCIO’s efforts to assess their workforce needs against Standards for Internal Controls in the Federal Government, specifically principle 13 on using quality information; and key workforce planning practices and activities.[7] For additional details on our scope and methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to August 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Key SSA Staff Supporting IT Contracts

Key acquisition staff who support SSA’s IT contracts reside in OAG and OCIO. These staff include contracting officers and contracting officer’s representatives.

Contracting Officer Duties and Reporting Chain

Contracting officers are responsible for the award and management of a contract, including reviewing and approving proposed solicitations and signing contract modifications, among other duties.[8] For example, contracting officers are expected to perform cost and price analyses on contractor proposals, accurately maintain contract data in the Federal Procurement Data System, and close out contract files.

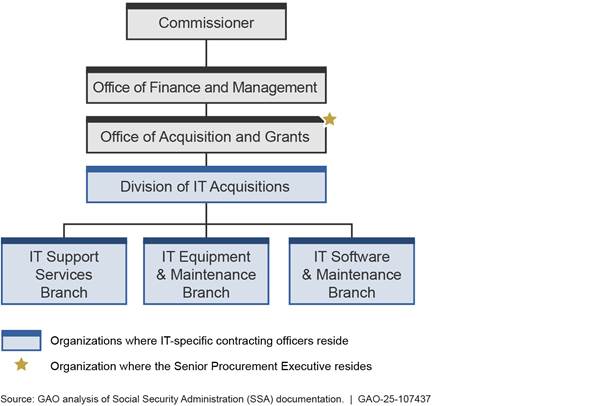

Contracting officers who support IT contracts reside in OAG, which is responsible for SSA-wide acquisition programs in support of the agency’s mission and strategic goals. OAG’s Division of Information Technology Acquisition (DITA) is responsible for the acquisition of IT products and services. DITA is led by a division director and has three IT-related branches: (1) IT Software & Maintenance Branch (software), (2) IT Equipment & Maintenance Branch (hardware), and (3) IT Support Services Branch (services). Each branch is led by a branch chief who is responsible for assigning work to contracting officers.

OAG is led by an Associate Commissioner who also serves as SSA’s Senior Procurement Executive. This official is responsible for the overall management of SSA’s procurement process, including the implementation of SSA’s procurement policies, regulations, and standards. In addition, OAG houses the Acquisition Career Manager, who manages the training needs and certifications for acquisition staff.

OAG is a component of the Office of Finance and Management, which is the office that leads SSA’s budget, acquisition and grants, facilities and security management, and financial policy and program integrity.[9] This office reports to SSA’s Commissioner. Figure 1 is an organizational chart showing the location of SSA’s IT-specific contracting officers.

Contracting Officer’s Representative Duties and Reporting Chain

CORs, who are designated by the contracting officer, serve as the technical representative assisting contracting officers with contract administration functions.[10] These duties may include resolving day-to-day matters, maintaining contract files, completing Contractor Performance Assessment Reports, and providing contracting officers with status updates and recommendations for corrective actions, among other responsibilities. CORs are not involved in functions that would contractually bind or obligate the government, including changes related to the terms and conditions of any contract. These functions remain the responsibility of the contracting officer.

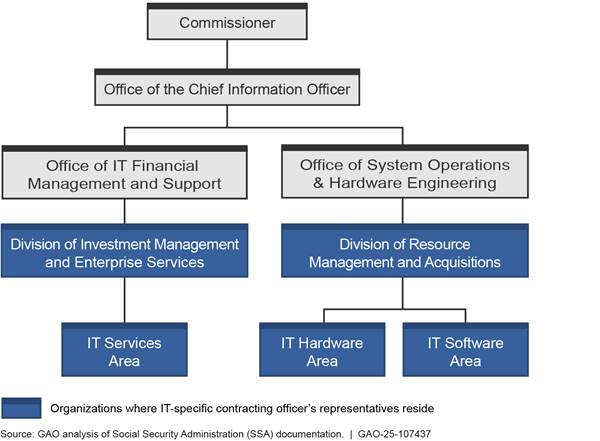

SSA CORs who support IT contracts primarily reside in one of two OCIO divisions, which are led by division directors:

· The Division of Resource Management and Acquisitions (DRMA) houses CORs responsible for IT software and hardware contracts.[11] DRMA is under the Office of Systems Operations and Hardware Engineering.

· The Division of Investment Management and Enterprise Services (DIMES) houses CORs responsible for IT services contracts.[12] DIMES is under the Office of IT Financial Management and Support.

The offices that house DIMES and DRMA report to OCIO. Figure 2 is an organizational chart showing the location of SSA’s IT-specific CORs.

Figure 2. Organizational Chart of SSA’s IT-specific Contracting Officer’s Representatives, as of July 2025

SSA officials said that CORs supporting IT contracts in DRMA and DIMES do so as their primary duty. In other agencies, COR duties may be just one of an employee’s assigned duties.[13] For example, an employee at the Department of Veterans Affairs may have a primary role as a doctor, but the employee may also be a COR overseeing the performance of a contract for medical supplies. SSA officials said that CORs supporting IT contracts are hired under the “IT management job series” but do not perform typical duties under this job series, such as IT help desk functions.[14] Instead, they carry out the functions noted above.

Recent Executive Memorandums, Guidance, and Orders, Affecting SSA’s Workforce and Acquisitions

In February 2025, SSA began efforts to reorganize and reduce its staff and consolidate its procurements, in response to executive memorandums and orders and subsequent guidance. These memorandums, guidance, and orders include the following (in chronological order from earliest to most recent):

· Executive memorandums to freeze hiring. In late January 2025, the President signed a memorandum to freeze the hiring of federal civilian employees in the executive branch.[15] Within 90 days of the issuance date of the memorandum, the Office of Management and Budget was required to submit a plan to reduce the size of the federal government’s workforce through efficiency improvements and attrition. Upon issuance of the Office of Management and Budget plan, the January memorandum instituting the freeze expired, with respect to most executive agencies. In April 2025, the President signed another memorandum extending the hiring freeze through July 15, 2025.[16] Both of these freezes included provisions that nothing in those memorandums should adversely impact the provision of Social Security benefits.

· Guidance on reorganization plans. In February 2025, the Office of Management and Budget and the Office of Personnel Management issued guidance for agencies to develop reorganization plans.[17] The guidance states that agencies should seek reductions in components and positions that are noncritical, implement technological solutions that automate routine tasks, and maximally reduce the use of outside consultants and contractors, among other things. The guidance states that agencies or components that provide direct services to citizens, such as Social Security, shall not implement any proposed agency reorganization plans until the Office of Management and Budget and the Office of Personnel Management certify that the plans will have a positive effect on the delivery of such services.

· Executive order on consolidation of procurements. On March 20, 2025, the President signed an executive order to consolidate agencies’ domestic procurements, including SSA, at the General Services Administration, whose Administrator was to be the executive agent for all government-wide IT acquisition contracts within 30 days of the order.[18] In April 2025, General Services Administration officials said they were in the process of transitioning certain civilian agencies’ procurement functions—including the Small Business Administration, Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Department of Education—to their agency. These officials added that by mid-May 2025, agencies were required to submit a template identifying common spending categories that could be transferred to the General Service Administration.

SSA’s efforts to address these executive memorandums and orders, and subsequent guidance, include plans to reduce the size of its workforce from 57,000 to 50,000 and reduce costs across all spending categories, including spending on contracted services.[19] OCIO officials told us that the agency’s hiring efforts were also halted. SSA took several actions to reduce the size of its workforce across the agency through voluntary mechanisms. It plans to use reduction-in-force actions to achieve its targeted workforce number:

· As of April 2025, the agency reported that 365 employees accepted deferred resignations.

· The agency is offering Voluntary Early Out Retirement to employees through the end of 2025.

SSA also offered all employees voluntary reassignments to mission critical positions, which may include contracting officers and CORs. These reassignments included positions in local field offices or teleservice centers. Over 2,000 employees volunteered for reassignment as of March 2025 and slightly less than half of these employees were to be reassigned as of April 2025, according to SSA.

In May 2025, SSA officials stated that they planned to implement these executive orders and related guidance, and that their reorganization efforts could affect the IT acquisition workforce. SSA officials said they would need to reassess and address their IT acquisition workforce needs after implementation of the March 2025 executive order on consolidating procurements at the General Services Administration.

SSA Obligated over a Billion Dollars Annually on IT Contracts in 2020‑2024, Mostly on IT Services

SSA obligated over $1 billion annually on IT acquisitions from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, though these obligations decreased overall during that time period. While most of SSA’s new IT contract awards and orders were for products during this time frame, most of its obligations on IT contracts were for services.

SSA Obligated Billions on IT Acquisitions in Fiscal Years 2020-2024, but Amount Decreased over That Period

SSA obligated more than $1 billion on IT acquisitions each year from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, but this amount decreased over that period. Adjusted for inflation, the agency’s total annual obligations on IT contracts decreased from $1.9 billion in 2020 to $1.4 billion in 2024. The number of SSA IT contract awards and orders also generally decreased over this period. Overall, SSA’s obligations on IT contracts accounted for approximately three-quarters of the agency’s total contract obligations each year during this period. Figure 3 shows SSA’s annual contract obligations on IT and non-IT contracts for fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

Figure 3. SSA’s Obligations on IT and Non-IT Contracts, Fiscal Years 2020-2024 (in fiscal year 2024 dollars)

About half (52 percent) of the 1,277 IT contract awards from fiscal years 2020 through 2024 were under the simplified acquisition threshold, generally $250,000.[20] Simplified acquisition procedures reduce administrative costs, promote efficiency and economy in contracting, and avoid unnecessary burdens for agencies and contractors.[21]

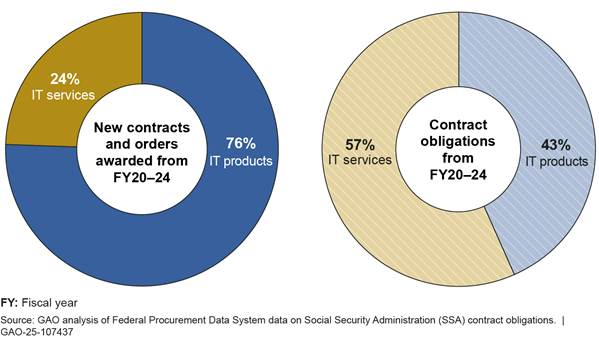

Most IT Contract Awards Were for Products While Most Obligations for IT Contracts Were for Services

From fiscal years 2020 through 2024, most of SSA’s IT contract and order awards were for IT products, while IT services made up more than half of SSA’s IT contract obligations in those years.[22] These trends were consistent across the 5-year period. The data indicate that on average, SSA’s IT services contracts had a higher dollar value than IT product contracts. Figure 4 shows the percentage of new contract and order awards and the percentage of contract obligations for IT products and IT services in the 5-year period.

Figure 4. Percentages of SSA’s Contract Awards and Obligations for IT Products and IT Services, Fiscal Years 2020-2024

Note: These data only include contracts and orders awarded from fiscal years 2020 through 2024.To identify IT products and services, GAO used the government-wide category management taxonomy to identify product and service codes aligned with IT and identified contract actions with those product and service codes in the Federal Procurement Data System.

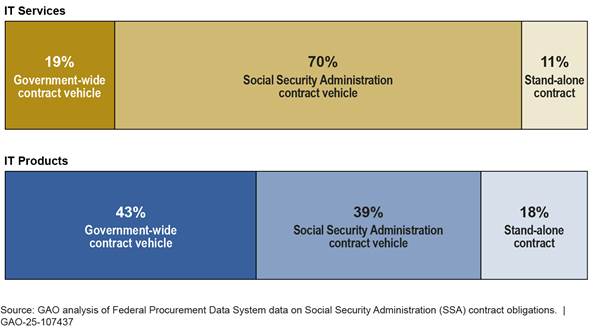

SSA’s use of different contract vehicle types varied for IT products and IT services.[23] Specifically, SSA used government-wide contract vehicles for about 20 percent of IT service awards and over 40 percent of its awards for IT products from 2020 through 2024.[24] Similarly, SSA used an SSA contract vehicle for 70 percent of its new IT service awards and almost 40 percent of its new IT product awards. Figure 5 shows the proportion of contracts for IT products and services by contract vehicle type.

Note: For this analysis, GAO defined government-wide vehicles as orders awarded on federal supply schedules, government-wide acquisition contracts, and basic ordering agreements. GAO defined SSA contract vehicles as indefinite delivery vehicles that were awarded by SSA. According to the Federal Procurement Data System, indefinite delivery vehicles may be established through awarding a federal supply schedule, government-wide acquisition contract, basic ordering agreement, blanket purchasing agreement, or other indefinite delivery contract described in FAR 17. Finally, SSA stand-alone contracts are definitive contracts or purchase orders awarded by SSA.

OAG Has Limited Workload Data and Lacks a Training Plan to Address Known Skills Gaps

OAG had limited data on contracting officers’ workload to enable it to determine its staffing needs. We found that OAG’s data on contracting officers’ contract assignments were unreliable for reporting, and that OAG did not have information on the complexity of assigned contracts. In addition, a November 2024 SSA-led contracting officer competency assessment report identified gaps in competencies such as contracting principles for staff in higher-grades. However, OAG has not yet developed or implemented a training plan for addressing these gaps. SSA’s implementation of executive orders and related guidance is ongoing and could affect contracting officers’ workloads and opportunities for training.

OAG Has Limited Workload Data to Inform Staffing Assessments

OAG had limited workload data on contracting officers who support IT contracts to inform its staffing assessments. In November 2024, OAG’s organization chart showed that about a third of the contracting officers (28 out of 97) were assigned to DITA’s IT branches: there were 10 contracting officers in IT software, 11 in IT hardware, and seven in IT services.[25] As noted in the previous objective, SSA’s obligations on IT contracts accounted for approximately three-quarters of the agency’s total contract obligations each year during this period. The November 2024 staffing numbers are a snapshot and, according to the Senior Procurement Executive, OAG’s contracting officers can rotate through OAG’s different offices.

The Senior Procurement Executive’s fiscal year 2024 hiring request for OAG staff was not based on contracting officer workload data. This official submitted a request to the Office of Finance and Management to reach a hiring limit of 120 full-time equivalents—including contracting officers and support staff—for fiscal year 2024.[26] This request did not specify how many of the 120 full-time equivalents requested would be needed to support IT contracts. In the request, the official noted that OAG had 108 full-time equivalents at the time. This official said the request was based on information related to OAG’s hiring and retention challenges rather than staff workload data. Specifically, they said the request was based on (1) historical staffing levels, (2) manager concerns about their need for additional staff to reduce the burden on existing staff and help prevent burnout, (3) OAG’s attrition rate, (4) the time it takes to train contracting officers, and (5) past difficulties hiring higher-grade staff from other federal agencies. The Office of Finance and Management denied the request for 120 full-time equivalents without providing further information.

OAG officials also told us that they received contradictory employee feedback information on contracting officers’ workloads. According to the Senior Procurement Executive, the 2024 Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey showed that about 70 percent of OAG staff who responded to the survey felt their workload was reasonable, while only 16 percent expressed a negative viewpoint.[27] This official explained that the survey responses contradicted OAG managers’ views as they consistently received feedback that contracting staff were overworked.

Despite a lack of workload data, discussed below, and contradictory feedback about IT and non-IT contracting officer workloads, OAG officials described taking actions to reduce staff workloads. The Senior Procurement Executive said that OAG decreased its contract actions by taking a more strategic approach to certain types of acquisitions, partly to help reduce staff workload. As previously noted, we found that SSA’s contract actions generally decreased from fiscal years 2020 through 2024. However, these decreases in contract actions may not account for the complexity of the contracts, which OAG officials said is a factor for staff assignments.

DITA also has limited workload data for its contracting officers who support IT contracts. The DITA division director said that DITA does not analyze individual contracting officer workloads or IT contract-related staffing needs because the work changes every year. DITA’s division director provided a spreadsheet in November 2024 identifying contract assignments for each contracting officer and said that DITA’s branch chiefs manually updated it. The spreadsheet included information such as contract number, contractor name, contract description, period of performance, and the estimated contract value. The DITA division director said that contracting officers were assigned to contracts based on their complexity, risks, and time frames; however, the spreadsheet did not include an assessment of contracting officers’ workloads or the workloads associated with these contracts. Further, we found errors such as duplicate entries in the spreadsheet for the same contract. In commenting on a draft of this report, SSA officials said that the absence of information on contract complexity in the spreadsheet does not mean DITA’s managers do not understand the complexity of the work assigned to contracting officers. However, none of the information provided by SSA during our review showed how they factored in the complexity of contracts in determining staff workloads.

In July 2024, OAG sought to collect additional information to determine if it had the right number and grade level of staff across OAG’s IT and non-IT divisions. OAG leadership requested that each OAG division submit written staffing plan requests for fiscal year 2025. Each staffing plan was to include the number of staff by grade and the number of contract awards in fiscal year 2023 by contracting value, such as the total number of contract awards under $250,000. The request for information allowed divisions to include information related to contract complexity.

DITA did not report contracting officers’ workload data when responding to the staffing plan request. In August 2024, DITA requested seven additional contracting officers across its three IT branches. All three branches reported staff departures as well as information on upcoming or anticipated contracts. For example, DITA’s services branch described losing two staff and noted that it was unsustainable for the remaining staff to take on that workload. The branch also described its anticipated contracts for fiscal year 2025 and reported information on the number of contracts by contracting amount at an aggregate level. Additional information on contracting officers’ workloads would have been useful to provide a more complete picture of DITA’s current staffing capacity.

Our key workforce planning activities state that agencies should regularly assess staffing needs and gaps in staffing, and develop staffing requirements.[28] Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that key information used to achieve objectives should be relevant and based on reliable data that are appropriate, current, complete, accurate, accessible, and provided on a timely basis.[29] Furthermore, we previously reported that assessing workload data is a key component of workforce planning.[30]

While OAG made an effort to collect data on the number of staff and contract values, it lacks quality workload data for contracting officers supporting IT acquisitions. For example, we determined that DITA’s contract assignment data were unreliable for our analysis due to duplicate entries. Additionally, the number of contract actions and the dollars awarded may not provide helpful insight into actual work performed because they do not account for contract complexity. Nevertheless, OAG is using these data to make staffing decisions. As SSA implements recent executive orders and related guidance, develops its reorganization plans, and determines the extent to which procurement activities will be transferred to the General Services Administration, SSA’s officials acknowledged that they will also need to reassess its contracting officer staffing needs to ensure it can accomplish its future goals. Informing such an assessment with quality workload data will enable OAG to more accurately determine whether its contracting officers can support current and future IT contracting needs.

SSA Assessed Contracting Officers’ Competencies, but OAG Lacks a Training Plan to Address Identified Skill Gaps

SSA assessed the capabilities of all its contracting officers, which include those that support IT contracts, but has not developed a training plan to address skills gaps it identified. In November 2024, SSA’s Office of Human Resources worked with a contractor to adapt the federal contracting competency model and assess the capabilities of the agency’s contracting officers by grade level (from GS-7 to GS-15).[31] The assessment compared contracting officers against varying degrees of expected proficiency at each grade level.[32] According to an SSA official, this assessment was part of an agencywide strategic workforce planning effort to identify workforce skills gaps, among other things. Table 1 describes the seven technical competencies that SSA used to assess the capabilities of its contracting officers.

|

Competency |

Definition |

|

Business Skills and Acumen |

Knowledge of establishing and managing contracts throughout the contract life cycle while ensuring customer satisfaction. |

|

Contracting Principles |

Knowledge and application of techniques and requirements for developing an acquisition strategy and leveraging various contract methods and types for effective and efficient execution of all contracting phases (e.g., solicitation, negotiation, award, and administration). |

|

Standards of Conduct |

Create trust and confidence in the integrity of contracting by exhibiting ethical and productive behavior. |

|

Situational Assessment |

Apply knowledge through lessons learned and best practices to ensure best value and implement innovative solutions. |

|

Team Dynamics |

Comprehensive understanding of all team roles and responsibilities, including those of government and contract personnel, to enhance cohesion and drive acquisition success. |

|

Written Communication and Documentation |

Facilitate communication through clearly written, comprehensible documentation and correspondence. |

|

Regulatory Compliance |

Knowledge of and adherence to all applicable laws, regulations, policies and procedures in performing the various contracting life cycle functions (e.g., solicitation, contract formation, administration, and closeout). |

Source: Social Security Administration (SSA) Office of Human Resources and Center for Organizational Excellence competency assessment report for SSA’s contracting officers, November 2024. | GAO‑25‑107437

Note: To develop this competency model, SSA’s contractor adapted the Department of Defense contracting competency model—which Office of Management and Budget guidance identified as being the standard for federal contracting specialists—to align with SSA’s technical competency model structure. Specifically, the contractor customized the competency definitions and example behaviors for SSA.

This assessment identified competency gaps for contracting officers at higher grades and no gaps for contracting officers at lower grades. Specifically, contracting officers at lower grades (GS-7 to GS-11) met or exceeded expected proficiency levels in all seven competencies. On the other hand, the competency assessment found that contracting officers at higher grades (GS-12 to GS-15) had deficiencies across three to seven competencies.

Furthermore, the assessment identified deficiencies in the Contracting Principles area across all higher grades. For example, contracting officers at the GS-12 level were expected to have an advanced level of proficiency (i.e., applies the competency in considerably difficult situations, and requires little to no guidance) for this competency. Instead, the assessment found that these contracting officers had an intermediate level of proficiency (i.e., applies the competency in difficult situations, and requires occasional guidance). The November 2024 competency assessment report recommended that SSA provide targeted training and development on the competencies that had lower proficiency levels than expected.

OAG does not have an updated training plan to address the competency gaps for contracting officers. Furthermore, OAG’s Training Plan for Purchasing Agents and Contract Specialists from 2019 describes general training guidance for contracting officers but has not been updated to align with current Federal Acquisition Certification requirements. OAG officials acknowledged that they have not updated this training plan. Nevertheless, despite not updating the 2019 Training Plan or having a plan to do so, they said that SSA’s Acquisition Career Manager is seeking training opportunities to address the competency gaps. In commenting on this draft, SSA officials did not say when they will update the 2019 Training Plan but noted that they intend to document training opportunities to address the competency gaps in a revised fiscal year 2026 training schedule.

Our key workforce planning activities state that agencies should develop strategies and plans to address gaps in competencies and implement activities to address gaps.[33] SSA’s contracting officers, including those who support IT contracts, may not be aware of the competency gaps identified and what courses would be needed to address them, if specific training is not included in an updated OAG training plan. Given the time since the last training plan update in 2019 and ongoing organizational changes, it is unclear that SSA will prioritize the implementation of trainings to address the acquisitions-related competency gaps identified. Developing and implementing a training plan that addresses the acquisitions-related competency gaps identified for contracting officers, including those who support IT contracts, remains vital as it would help OAG ensure that its contracting officers have the skills to support SSA’s current and future IT contracting needs.

OCIO Reported COR Staffing Shortages but Has Not Assessed Workloads Across all IT Acquisition Areas

OCIO officials told us they were understaffed but the two units supporting IT acquisitions varied in the information they provided on their COR staffing needs at the end of 2024. They also told us that a shortage of CORs supporting software contracts caused SSA to pause a streamlined IT acquisition process in June 2024. OCIO analyzed the workloads of CORs supporting IT software contracts and found eight of nine staff exceeded a full workload, but has conducted only limited assessments of the workloads of CORs supporting IT hardware and service contracts. SSA’s implementation of executive orders and related guidance are ongoing and could affect COR workloads.

OCIO Units Varied in Amount of Information They Provided on COR Staffing Needs

OCIO officials said they were understaffed but OCIO’s units varied in the amount of information they had on specific staffing needs. These officials said that 51 CORs supported SSA’s IT software, hardware, and service contracts as of November 2024.[34] Of these 51, nine supported IT software contracts and 25 supported IT hardware contracts within DRMA (34 combined).[35] DRMA’s director said this was about half of the division’s staff allocation of 65 staff. The other 17 CORs supported IT service contracts within DIMES.[36] DIMES’s acting director stated that this division was also understaffed but did not provide information on the unit’s staff allocation as DRMA’s director did.

In late 2024, DRMA and DIMES told us that they were understaffed with CORs due to staff departures and hiring constraints.

· Staff departures. In October and November 2024, both DRMA and DIMES officials told us that some of their CORs had left SSA and had not been replaced. DRMA documentation showed that since 2020, DRMA lost 15 CORs and hired three. The DIMES acting director said the division did not replace several CORs who had left, but could not provide additional details; this official had been recently appointed. These directors described two primary causes for COR departures: retirements and CORs seeking promotion opportunities at other agencies.[37]

· Hiring constraints. In October 2024, DRMA and DIMES directors told us that they were understaffed due to COR hiring constraints. The directors said OCIO retains authority over all vacancies within OCIO. When staff depart from DRMA or DIMES, those open positions (i.e., “hiring slots”) return to OCIO and may be redistributed to other offices. However, OCIO also reported that the office as a whole was facing workforce shortages beyond CORs.

COR Shortages Halted a Streamlined Acquisition Process for Software Contracts

DRMA’s shortage of CORs supporting IT software contracts caused SSA to pause a streamlined IT acquisition process for software contracts, according to SSA officials. This streamlined process, which the DRMA director said was paused in June 2024, applied to all software acquisition requests. Its intent was to centralize SSA’s software licensing purchases and leverage negotiated discounts, among other things. SSA documentation stated that this process resulted in $430 million in cost savings from fiscal years 2013 through 2024.

According to SSA documentation, DRMA does not have enough CORs to support the streamlined acquisition process. Specifically, DRMA needed 33-35 full-time CORs to support the streamlined acquisition process for software contracts. Under this process, CORs reviewed the current inventory of SSA-owned licenses to identify those that could be used to meet requirements before moving forward with a purchase. CORs also assisted in the development of pre-award planning documents for new IT contracts, such as the requests for information and analyses of alternatives. As noted above, DRMA had nine CORs assigned to software acquisitions in November 2024.

Without the streamlined process, SSA officials said that awarding software contracts will be more time-consuming and potentially lead to higher costs. OCIO officials said that SSA customers in need of software will have to work directly with OAG contracting officers to plan software purchases, rather than working with DRMA’s CORs to do so. In November 2024, the Senior Procurement Executive said that software COR shortages also contributed to late requirement submissions to contracting officers, which could delay contract awards. This official told us that contracting officers could handle delayed software requirements in the past because DRMA CORs served as an intermediary between SSA customers in need of software and the contracting officers who award contracts. We are not making a recommendation to SSA on re-instituting the streamlined process because SSA’s reorganization efforts are underway.

OCIO Conducted Limited Assessments of COR Workloads for IT Hardware and Services

Within OCIO, DRMA and DIMES have conducted limited assessments of IT hardware and services COR workloads. According to the DRMA and DIMES directors, the number of contracts that a COR supports varies depending on the complexity of the contracts assigned. Complex contracts have an alternate or secondary COR to ensure adequate oversight of the contract. OCIO provided us with spreadsheets showing the CORs’ workloads, which officials said were monitored and reviewed on a regular basis. However, the spreadsheets assessed workloads for software CORs but not for hardware and services CORs.

· DRMA’s spreadsheet for software CORs from November 2024 shows that eight of nine staff exceeded a full workload.[38] DRMA’s definition of a full workload accounts for the number of contracts and the amount of work associated with each contract, such as the level of vendor interaction required. Each contract is classified as being in one of six tiers, which have varying definitions for a full workload. For example, tier one contracts are defined as those that require the COR to spend 75 percent of their time on the contract; being assigned to a single tier one contract represents a complete workload for one COR. In contrast, a tier six contract is less than $100,000 and generally requires attention once a year; the analysis states that a COR will be able to handle over 50 tier six contracts for a complete workload.

· Spreadsheets for service and hardware CORs identified limited contract assignment information. For example, OCIO initially provided spreadsheets that lacked contract numbers while subsequent spreadsheets included them; however, none of the spreadsheets included information on the complexity of staff workloads. OCIO officials did not tell us why the service and hardware CORs’ spreadsheets did not include workload analysis as DRMA does for its software CORs.

Our key IT workforce planning practices state that agencies should regularly assess staffing needs, as well as gaps in staffing.[39] In addition, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government states that key information used to achieve objectives should be relevant and based on reliable data that are appropriate, current, complete, accurate, accessible, and provided on a timely basis.[40] We also previously reported that assessing workload data is a key component of workforce planning.[41] Further, Office of Management and Budget guidance states that COR assignments should consider risk factors, such as complexity and contract type.[42]

As SSA implements recent executive orders and related guidance, develops its reorganization plans, and determines the extent to which procurement activities will be transferred to the General Services Administration, SSA officials acknowledged that they will also need to reassess its COR staffing needs to ensure it can accomplish its future goals. As we previously noted, OCIO’s software COR shortages caused the agency to halt a streamlined acquisition process that had produced reported cost savings. Without comprehensive assessments of COR staffing needs using quality workload data, OCIO might have difficulty determining whether its CORs can support its current and future IT contracting needs.

Conclusions

We and others have reported on the challenges SSA has faced in modernizing its IT systems and planning for its human capital needs. Addressing these challenges will be key as SSA implements recent executive orders and related guidance, develops its reorganization plans, and determines the extent to which procurement activities will be transferred to the General Services Administration. More than 20 years ago, we identified that strategic human capital management was critical to transforming the cultures of government agencies, including having the right people with the right skills to successfully change the acquisition environment. SSA officials acknowledged that they will need to reassess and address their IT acquisition workforce needs after implementation of the executive order on consolidating procurements.[43]

To operate effectively in this changing acquisition environment, SSA needs quality workload data and well-trained contracting staff to support IT contracts. It is important for offices managing contracting officers and CORs who support IT contracts to determine their staffing needs using quality workload data to ensure SSA can accomplish its future goals. In addition, it is important for SSA to develop a training plan to address known competency gaps for contracting officers so that they are equipped to support SSA’s current and future contracting needs.

Recommendations for Executive Action

We are making the following three recommendations to SSA to inform its decisions as the current reorganization unfolds:

The SSA Commissioner should ensure that the Senior Procurement Executive assesses and documents IT contracting officers’ staffing needs based on quality workload information, such as the quantity and complexity of individual workloads. (Recommendation 1)

The SSA Commissioner should ensure that the Senior Procurement Executive develops and implements a training plan that addresses acquisitions-related competency gaps identified for IT contracting officers. (Recommendation 2)

The SSA Commissioner should ensure that the Chief Information Officer assesses and documents IT contracting officer’s representatives’ staffing needs based on quality workload information, such as the quantity and complexity of individual workloads. (Recommendation 3)

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation

We provided a draft of this report to SSA for review and comment. In its written comments, reproduced in appendix II, SSA agreed with our recommendations. In a separate response to our draft report over email, SSA officials stated that their managers consider workload complexity in making workload decisions, and OAG is planning to address the training needs for contracting officers. We responded to these comments in our report. We noted that SSA did not provide any documentation that showed consideration of workload complexity in assessing staffing needs. Additionally, SSA’s existing training plan dates to 2019 and has not yet been updated. Finally, SSA provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

As agreed with your offices unless you publicly announce the contents of this report earlier, we plan no further distribution until 30 days from the report date. At that time, we will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees and the Administrator of the Social Security Administration. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at sehgalm@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix III.

Mona Sehgal

Director, Contracting and National Security Acquisitions

This report examines (1) how much the Social Security Administration (SSA) obligated for IT products and services from fiscal years 2020 through 2024; and the extent to which (2) the Office of Acquisition and Grants (OAG) took steps to assess and address its needs for contracting officers who support IT contracts, and (3) the Office of the Chief Information Officer (OCIO) took steps to assess and address its needs for contracting officers’ representatives (COR) who support IT contracts.

To examine how much SSA obligated for IT products and services from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, we relied on information from the Federal Procurement Data System.[44] We reviewed contract obligations through fiscal year 2024 because it was the most recent full fiscal year for which data were available at the time of our review. To assess the reliability of these data, we reviewed the data dictionary and data validation rules for the system. We also reviewed SSA’s quality reports for this data system and excluded data fields that were identified as having accuracy issues. Specifically, we excluded fiscal year 2019 data from our analysis because SSA’s quality report stated that the “base and all options value” data field had accuracy issues in that year. We also excluded the “extent competed” data field due to accuracy issues in fiscal years 2020, 2021, and 2023. We determined that the Federal Procurement Data System data were reliable for reporting SSA’s contract obligations and number of contracts from fiscal years 2020 through 2024.

Also for objective one, to analyze SSA’s IT contract actions from fiscal years 2020 through 2024, we created an ad hoc query on SAM.gov to identify contract action reports awarded by SSA. To identify IT products and services, we used the government-wide category management taxonomy to identify product and service codes aligned with IT, and we identified contract actions with those product and service codes in the Federal Procurement Data System. To categorize contract actions by type of contracting vehicle, we grouped contracts as stand-alone contracts, government-wide vehicles, and SSA vehicles, as follows:

· Stand-alone contracts include definitive contracts and purchase orders;

· Government-wide vehicles include orders on Government-Wide Acquisition Contracts, Federal Supply Schedules, and Indefinite Delivery Contracts and Basic Ordering Agreements not awarded by SSA; and

· SSA vehicles include all Blanket Purchase Agreements awarded by SSA, calls (orders) on those Blanket Purchase Agreements, Indefinite Delivery Contracts awarded by SSA, and orders on those Indefinite Delivery Contracts.

To examine the extent to which OAG took steps to assess and address its IT contracting officer workforce needs:

· We reviewed SSA’s Acquisition Handbook, dated January 2024; training guidance; position descriptions; staffing plans submitted by OAG’s offices, including the Division of IT Acquisitions (DITA); delegation memorandums for the Senior Procurement Executive and the Acquisition Career Manager; and OAG’s Federal Employee Viewpoint survey results for 2024.

· We reviewed SSA’s November 2024 competency assessment report for contracting officers. SSA’s Office of Human Resources worked with the Center for Organizational Excellence to (1) develop, validate, and assess technical competencies for contracting officers, and (2) identify trainings to close technical skill gaps.

· We interviewed several key OAG staff, including the Senior Procurement Executive/Associate Commissioner of OAG, Deputy Associate Commissioner of OAG, the Acquisition Career Manager, and the DITA division director. Our interviews covered their roles and responsibilities, contract assignment processes, contracting officer rotations, staffing needs and challenges, workload analysis, changes in SSA’s IT contract awards in recent years, competency assessments, training requirements and offerings, and their involvement in SSA’s human capital planning efforts.

· We interviewed officials from SSA’s Office of Human Resources to collect information on the contracting officer competency assessment.

· We reviewed OAG organizational charts and information provided by DITA on contracting officer assignments. To determine the reliability of these data, we requested information about how OAG collected this information, identified data limitations, and conducted data testing of contracting officer assignments, such as checking for missing values and duplicate entries. We determined that the reliability of OAG’s organizational charts was sufficient to report the number of contracting officers as of November 2024. We described the types of information in DITA’s spreadsheet at a high-level in our report but did not analyze the data—we determined that DITA’s spreadsheets were unreliable for reporting which contracts were assigned to each contracting officer because of discrepancies in the number of contracts reported by OAG and OCIO. OAG officials said the spreadsheet is updated manually and there can be lags in updating the data when staff rotate to other offices. We found duplicate entries in the spreadsheet for some contracts. We also found that there was a mismatch in the reported number of IT contracts supported by contracting officers versus the reported number supported by the CORs in the Division of Resource Management and Acquisitions (DRMA) and the Division of Investment Management and Enterprise Services (DIMES). Neither office could confirm information as to why these discrepancies were present.

· We assessed OAG’s efforts to assess its workforce needs against Standards for Internal Controls in the Federal Government, specifically principle 13 on using quality information; and a general version of key workforce planning practices and activities.[45]

To examine the extent to which OCIO took steps to assess and address its COR IT workforce needs:

· We reviewed documentation on COR position descriptions, the centralized IT acquisition process, and OCIO’s survey report of its staff who separated from the agency in fiscal year 2024.

· We interviewed the DRMA division director and DIMES acting division director about their roles and responsibilities, COR assignment process, staffing needs and challenges, workload analysis, and the plans to centralize and streamline the IT acquisition process.

· We reviewed spreadsheets provided by DRMA and DIMES on COR workloads, as well as data provided by OAG on the number of staff who held a Federal Acquisition Certification for CORs. OAG provided a report that combines data from the Federal Acquisition Institute’s Cornerstone OnDemand system with SSA’s contract writing system. We determined the reliability of these data by requesting information on data collection methods, identifying data limitations, and conducting data tests of contract assignment data, including checking the summary data against totals provided by SSA. We determined that the total number of staff who held the Federal Acquisition Certification for CORs and had an active account in SSA’s contract writing system as of September 2024 was sufficiently reliable for us to report. We described the information in OCIO’s spreadsheets but did not analyze the data—we determined that OCIO’s data were unreliable for reporting which contracts CORs were assigned to because of discrepancies in the number of contracts reported by OAG and OCIO. We found a mismatch in the reported number of IT contracts supported by contracting officers versus the reported number supported by the CORs in DRMA and DIMES. Neither office could confirm information as to why these discrepancies were present.

· We assessed DRMA’s and DIMES’s efforts to assess their workforce needs against Standards for Internal Controls in the Federal Government, specifically principle 13 on using quality information; and key IT workforce planning practices and activities.[46]

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to August 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

GAO Contact

Mona Sehgal, sehgalm@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact above, the following staff made key contributions to this report: Guisseli Reyes-Turnell (Assistant Director), Joy Kim (Analyst in Charge), Hannah Bisbing, Christina Cota-Robles, Andrea Evans, Suellen Foth, Edward Harmon, Sylvia Schatz, and Adam Wolfe.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]GAO, Information Technology: SSA Needs to Address Limitations in Management Controls and Human Capital Planning to Support Modernization Efforts, GAO‑14‑308 (Washington, D.C.: May 8, 2014).

[2]Social Security Administration, Office of the Inspector General, Management Advisory Report: The Social Security Administration’s Major Management and Performance Challenges During Fiscal Year 2023, 022330 (Nov. 3, 2023).

[3]Social Security Administration, Office of the Inspector General, Audit Report: Legacy Systems Modernization and Movement to Cloud Services (Sept. 26, 2024). This audit was performed by an independent certified public accounting firm; the Office of the Inspector General provided technical and administrative oversight.

[4]GAO, IT Investment Management: Social Security Administration Needs to Oversee Investments in Operations and Better Evaluate Investment Outcomes, GAO‑25‑107200 (Washington, D.C.: June 26, 2025).

[5]GAO, Acquisition Workforce: Status of Agency Efforts to Address Future Needs, GAO‑03‑55 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 18, 2002).

[6]GAO, High-Risk Series: Heightened Attention Could Save Billions More and Improve Government Efficiency and Effectiveness, GAO‑25‑107743 (Washington, D.C.: Feb.25, 2025).

[7]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014); Data Science: NIH Needs to Implement Key Workforce Planning Activities, GAO‑23‑105594 (Washington, D.C.: June 22, 2023); and IT Workforce: Key Practices Help Ensure Strong Integrated Program Teams, Selected Departments Need to Assess Skill Gaps, GAO‑17‑8 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 30, 2016).

[8]Social Security Administration’s (SSA) Acquisition Handbook distinguishes between Contracting officers, Contract Specialists, and Purchasing agents. Contracting officers are often simultaneously a contract specialist or purchasing agent. For the purposes of this report, we refer to all staff in the contracting job series (GS-1102) as contracting officers.

[9]The Office of Finance and Management was previously called the Office of Budget, Finance, and Management. SSA renamed it in June 2025 as part of its reorganization effort.

[10]FAR 1.604.

[11]The DRMA director said that most of SSA’s hardware contracts are handled by DRMA CORs, but that some hardware contracts are managed by CORs on another hardware team.

[12]The DRMA director said that DRMA had a few IT service contracts for network installation support services but the rest of the IT service contracts were managed by DIMES.

[13]See GAO, VA Acquisition Management: Actions Needed to Better Manage the Acquisition Workforce, GAO‑22‑105031 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 29, 2022); and Defense Workforce: Steps Needed to Identify Acquisition Training Needs for Non-Acquisition Personnel, GAO‑19‑556 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 5, 2019).

[14]GS-2210 is the Federal Employee General Schedule Information Technology Management Series.

[15]Presidential Memorandum, Hiring Freeze, 90 Fed. Reg. 8247 (Jan. 20, 2025).

[16]Presidential Memorandum, Extension of Hiring Freeze (Apr. 17, 2025).

[17]Office of Management and Budget and Office of Personnel Management, Memorandum on Guidance on Agency RIF and Reorganization Plans Requested by Implementing the President’s ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ Workforce Optimization Initiative (Feb. 26, 2025).

[18]Exec. Order 14,240, 90 Fed. Reg. 13,671 (Mar. 20, 2025). The Administrator of General Services must defer or decline the executive agent designation for government-wide IT acquisition contracts when necessary to ensure continuity of service or as otherwise appropriate. The executive order’s definition of “agency” includes but is not limited to executive departments, military departments, and other establishments in the executive branch of the Government. 44 U.S.C. § 3502. SSA is defined in 42 U.S.C. § 901 as an independent agency in the executive branch of the government.

[19]“Social Security Announces Workforce and Organization Plans,” Social Security Administration, accessed Apr. 16, 2025, https://blog.ssa.gov/social‑security‑announces‑workforce‑and‑organization‑plans/.

[20]The micro-purchase threshold is generally $10,000. The simplified acquisition threshold is generally $250,000. FAR 2.101. Agencies must use simplified acquisition procedures to the maximum extent practicable for all purchases of supplies or services not exceeding the simplified acquisition threshold (including purchases at or below the micro-purchase threshold). FAR 13.003.

[21]FAR 13.002.

[22]The number of contracts and the value of obligations are sometimes treated as a simple way to measure workload for acquisition staff. These data points do not account for factors that may influence contract complexity such as the degree of technical certainty or level of skill labor needed.

[23]A contract vehicle is a contract, or group of contracts, that provides a streamlined process for government agencies to place multiple orders for certain products and services with a preselected vendor or group of vendors.

[24]Government-wide contract vehicles are a way to maximize efficiencies in the procurement process and achieve cost savings by leveraging the government’s buying power when acquiring IT products and services. In addition, these contract vehicles can affect contracting officer workload because agencies can procure products and services without the time and expense of a full and open competition for each order.

[25]This count only includes staff in the contracting job series (GS-1102).

[26]OAG also houses IT specialists, auditors, and management analysts.

[27]The Office of Personnel Management Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey is an annual organizational climate survey that assesses how employees experience the policies, practices, and procedures characteristic of their agency and its leadership. The office administers the survey to employees of federal agencies that accept an invitation to participate. Eighty-four staff in the Office of Acquisition and Grants responded to the question about “My workload is reasonable.”

[28]We previously established a general workforce planning framework based on federal guidance, including the Office of Personnel Management Workforce Planning Model, and our prior work, such as our key principles for effective strategic workforce planning. See GAO‑23‑105594 for more information.

[30]GAO, DOJ Workforce Planning: Grant-Making Components Should Enhance the Utility of Their Staffing Models, GAO‑13‑92 (Washington, D.C.: Dec. 14, 2012)

[31]The general schedule classification and pay system covers most federal employees in professional, technical, administrative, and clerical positions. The general schedule has 15 grades—GS-1 is the lowest and GS-15 is the highest. According to OAG officials, contracting officers at GS-7 to GS-11 are generally considered to be junior staff, and supervisory positions begin at GS-13.

[32]The contractor developed a draft competency model and solicited input from representative groups of nonsupervisory and supervisory level contracting officers on the expected proficiency levels, at each grade level, for each competency.

[34]As of September 2024, SSA had nearly 900 CORs agencywide who may have supported a contract. This count was based on an SSA-produced report that identifies staff who had the Federal Acquisition Certification for CORs and an active account in SSA’s contract writing system.

[35]In May 2025, SSA officials stated that DRMA’s IT Software Area moved to DIMES and that the IT Software Area had eight CORs. They added that DRMA had two CORs.

[36]In May 2025, SSA officials said that DIMES had five CORs in the IT Services area.

[37]According to a 2024 SSA exit survey, retirement eligibility and career advancement opportunities were also common causes for staff departures in OCIO as a whole (42 percent retirements, 9 percent leaving for other agencies).

[38]This analysis was for contract renewals only.

[42]Office of Management and Budget, Revisions to the Federal Acquisition Certification for Contracting Officer’s Representatives (Sept. 6, 2011).

[43]Exec. Order 14,240, 90 Fed. Reg. 13,671 (Mar. 20, 2025).

[44]The Federal Procurement Data System is the central repository for capturing information on federal contracting that is managed by the General Services Administration. Federal agencies, including SSA, are responsible for collecting and reporting data into the system as required by the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). See FAR subpart 4.6.

[45]GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO‑14‑704G (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 10, 2014). We applied a general version of our key workforce planning practices and activities. These practices and activities were based on an IT workforce planning framework for assessing federal agencies’ IT workforce planning efforts. See GAO, Data Science: NIH Needs to Implement Key Workforce Planning Activities, GAO‑23‑105594 (Washington, D.C.: June 22, 2023).

[46]GAO‑14‑704G. We applied IT workforce planning practices, which were developed based on federal laws and Office of Management and Budget and Office of Personnel Management guidance on IT workforce planning activities. See GAO, IT Workforce: Key Practices Help Ensure Strong Integrated Program Teams; Selected Departments Need to Assess Skill Gaps, GAO‑17‑8 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 30, 2016).