TRIBAL ENERGY FINANCE

Changes to DOE Loan Program Would Reduce Barriers for Tribes

Report to the Committee on Indian Affairs, U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-25-107441, a report to the Committee on Indian Affairs, U.S. Senate

For more information, contact: Anna Maria Ortiz at OrtizA@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

Tribes can get important economic benefits from energy projects on their lands, such as revenue for government operations. The Department of Energy’s (DOE) Tribal Energy Financing Program (TEFP) offers loans and loan guarantees for such projects.

However, Tribes may be experiencing barriers to participation, which could limit development of untapped energy resources on tribal lands.

GAO Key Takeaways

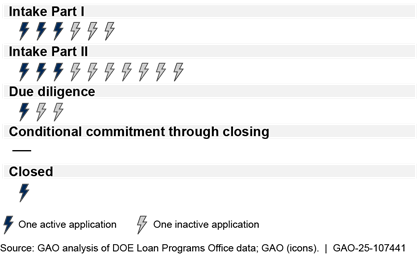

Since its first solicitation in 2018, TEFP has received 20 applications for loans and loan guarantees for various project types and amounts. Requests ranged from $23.7 million for a solar project to $8.7 billion for an ammonia production facility for low-carbon fuel. DOE’s Loan Programs Office, which manages TEFP, has closed one loan guarantee and no loans. According to DOE officials, seven other applications were active as of July 18, 2025.

Tribes said TEFP can finance a variety of energy projects needed for energy production and economic development. However, aspects of TEFP’s design and implementation create barriers. For example, DOE hires outside lawyers and technical experts to review projects. Tribal applicants are required to cover the costs of these services, which can be high and unpredictable. Tribes may avoid applying for the program until DOE revises its review processes to reduce or eliminate the cost.

Additionally, there are few DOE program staff with tribal experience to review applications, which can lengthen reviews. Without staff with the necessary expertise, Tribes may continue to experience barriers to securing TEFP financing.

Note: Active applications include closed loans, which DOE has finalized with the applicant and continues to monitor throughout the loan term. Inactive applications have been put on hold, withdrawn, or abandoned. DOE officials confirmed that they had not received any new applications for the program as of July 18, 2025.

How GAO Did This Study

We analyzed agency data and documents and interviewed agency officials, potential tribal participants, and tribal stakeholders. We compared agency efforts with relevant laws, regulations, guidance, and executive orders.

What GAO Recommends

We are making five recommendations to DOE, including that it revise its review process to reduce fees. We are also recommending that DOE maintain designated staff to review TEFP applications and provide them more training.

|

Abbreviations |

|

|

|

|

|

DOE |

Department of Energy |

|

IE |

Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs |

|

IRA |

Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 |

|

LPO |

Loan Programs Office |

|

OMB |

Office of Management and Budget |

|

TEDO |

tribal energy development organization |

|

TEFP |

Tribal Energy Financing Program |

|

USDA |

U.S. Department of Agriculture |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

August 11, 2025

The Honorable Lisa Murkowski

Chairman

The Honorable Brian Schatz

Vice Chairman

Committee on Indian Affairs

United States Senate

Considerable energy resources exist throughout Indian country, including conventional mineral resources such as oil, gas, and coal, and resources with significant potential for renewable energy development, including wind and solar. Developing these energy resources through tribal energy projects can help address the nation’s energy needs.[1] Tribal energy projects can also offer important economic development opportunities for tribal communities, such as high-quality jobs and revenue for government operations and social service programs.[2] Tribes may also seek to increase access to reliable and affordable energy.

However, lack of access to capital and other unique challenges in tribal communities have created barriers to such projects. Tribes may need financial and technical assistance to develop energy projects because they may not have sufficient revenue or capacity to independently develop projects, as we reported in July 2024.[3] They also can face challenges with obtaining loans from private lenders. Furthermore, tribal applicants experience systemic barriers to accessing federal programs, funding, and services such as administrative burdens and financial constraints, as we have previously reported.[4]

The Department of Energy’s (DOE) Tribal Energy Financing Program (TEFP), established in 2005, provides loans and loan guarantees for tribal energy development.[5] DOE’s Loan Programs Office (LPO) is responsible for administering the program. The program supports federally recognized Indian Tribes or tribal energy development organizations that develop energy resources, products, or services using commercial technology. This development can increase Tribes’ access to low-cost capital, community energy ownership, and other economic benefits, according to DOE documents.

However, DOE officials have raised concerns that Tribes may be experiencing barriers when applying for TEFP. For example, in a 2023 hearing, a DOE official testified about barriers to tribal participation in the program.[6] At that time, the program had yet to close any loans or loan guarantees. More broadly, the DOE Office of the Inspector General has identified concerns about risk areas within LPO, including insufficient federal staffing; inadequate policies, procedures, and internal controls; lack of accountability and transparency; and potential conflicts of interest and undue influence.[7] We issued nine reports on DOE’s loan programs from 2007 to 2025 and made multiple recommendations to improve the programs, including several recommendations focused on ensuring LPO had appropriate guidance and procedures in place.[8] DOE has implemented most of these recommendations.[9]

You asked us to describe the status of TEFP applications, views on the strengths and limitations of the program, and ways to improve its design and implementation. This report (1) describes the status of TEFP applications since DOE’s first solicitation in 2018; (2) examines the strengths and limitations of the program’s design and the extent to which DOE and Congress could address limitations that may affect program uptake; and (3) examines the strengths and limitations of the program’s implementation and the extent to which DOE could address these limitations.

To describe the status of TEFP applications since 2018, we reviewed relevant laws, regulations, agency policies, and guidance documents; analyzed LPO data and TEFP application documents; and interviewed LPO officials about the application process. Specifically, to describe proposed energy projects, requested loan amounts, the status of applications, and the duration of the application review process, we analyzed LPO data from DOE’s Quicksilver database as of February 2025, the most recent available at the time of our review.[10] We assessed these data and found them to be sufficiently reliable for our purposes for this review.[11] We also reviewed application documents for additional details on proposed energy projects, such as their purpose and power generation capacity.

To examine the strengths and limitations of the program’s design and implementation and the extent to which DOE and Congress could address limitations that could affect program uptake, we reviewed laws, regulations, and agency policies that affect program design and implementation.[12] We also reviewed internal and external program documents that LPO uses to implement the program. These include internal staffing charts, training materials, program workflow documents, and application review tools, as well as publicly available documents such as the program solicitation and frequently asked questions about the program on LPO’s website. We compared the design and implementation of the program against applicable requirements in federal laws, regulations, guidance, and directives in relevant executive orders.

In addition, we interviewed DOE officials, potential participants including tribal officials, and tribal stakeholders:[13]

· DOE officials. We interviewed LPO officials responsible for administering TEFP about their perspectives on the strengths and limitations of the program’s design and implementation, actions LPO has taken to improve the program, and the extent to which DOE and Congress could take further actions to address limitations or improve the program. We also interviewed officials from DOE’s Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs (IE)—a primary office responsible for providing technical and financial assistance to Tribes for tribal energy projects—about their interactions with LPO and their perspectives on the strengths and limitations of the program.[14]

· Potential participants. We interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of 12 potential participants (e.g., Tribes and lenders) that applied or considered applying to the program.[15] Six were entities that had applied to the program since the first program solicitation in 2018—in this report, we refer to them as tribal applicants.[16] We met with two of these applicants in person during site visits. The other six potential participants had considered the program but did not apply. We asked all 12 about their proposed projects and for their perspectives on (1) the strengths and limitations of the program and (2) actions LPO and Congress could take to improve the design and implementation of the program.

· Tribal stakeholders. We interviewed a nongeneralizable sample of five tribal energy stakeholders (e.g., lenders, consultants, and nongovernment organizations) for additional perspectives.

We reviewed our prior work on tribal energy and barriers to tribal participation in federal programs, as well as leading practices and lessons learned from comparable loan and loan guarantee programs identified by potential participants and that could be used to finance tribal energy projects. Specifically, we reviewed documents and interviewed officials from the Department of the Interior’s Indian Affairs organization about its Indian Loan Guarantee and Insurance Program. We also reviewed documents and interviewed officials from U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Rural Development agency about how they administer similar programs, including the Electric Infrastructure Loan and Loan Guarantee Program.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Federal Trust Responsibility

The United States has a government-to-government relationship with federally recognized Tribes. Through treaties, statutes, and historical relations, the United States has undertaken a unique trust responsibility to protect and support Tribes and their citizens.[17] In 2018, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights assessed whether the federal government was meeting its responsibilities to Tribes and found that Native Americans continued to rank near the bottom of all Americans in terms of health, education, and employment.[18] In its assessment, the commission attributed this disparity in part to federal policies that have historically been discriminatory toward Tribes, as well as insufficient resources and inefficiencies in federal programs that serve Tribes. For example, the commission found that federal funding for certain programs and services for Tribes and their citizens continued to be disproportionately lower than federal funding for similar programs and services to non-Native populations.

Tribal Energy Project Opportunities

Developing tribal energy resources can create economic development opportunities for some Tribes and their members. For example, they can help improve living conditions, decrease poverty, and increase employment within the Tribe and surrounding areas. Economic development is particularly important for tribal governments, which have many of the same responsibilities to provide government and social services as state and local governments. However, unlike state and local governments, tribal governments typically do not have access to traditional tax bases. As a result, they must overwhelmingly rely on revenues earned through their ownership of businesses—such as energy projects—as a source of financial support for the programs and services they provide to their communities.

In addition, energy projects may help Tribes meet their energy goals. For example, tribal communities are more likely to live without access to electricity and to pay some of the highest energy rates in the country, according to our prior work.[19] Tribal energy projects can help address these challenges by increasing reliable access to electricity and lowering energy costs. Tribes may also pursue energy projects to meet other goals such as energy sovereignty or environmental protection.

Energy projects on tribal lands can help the nation meet its demand for energy and electricity. According to DOE, while tribal lands account for only 2 percent of all U.S. land, they contain an estimated 50 percent of potential uranium reserves, 30 percent of coal reserves west of the Mississippi, 20 percent of known oil and gas reserves, and 6.5 percent of all utility-scale potential U.S. renewable energy resources.[20] However, 86 percent of tribal lands with energy potential are undeveloped, according to DOE.

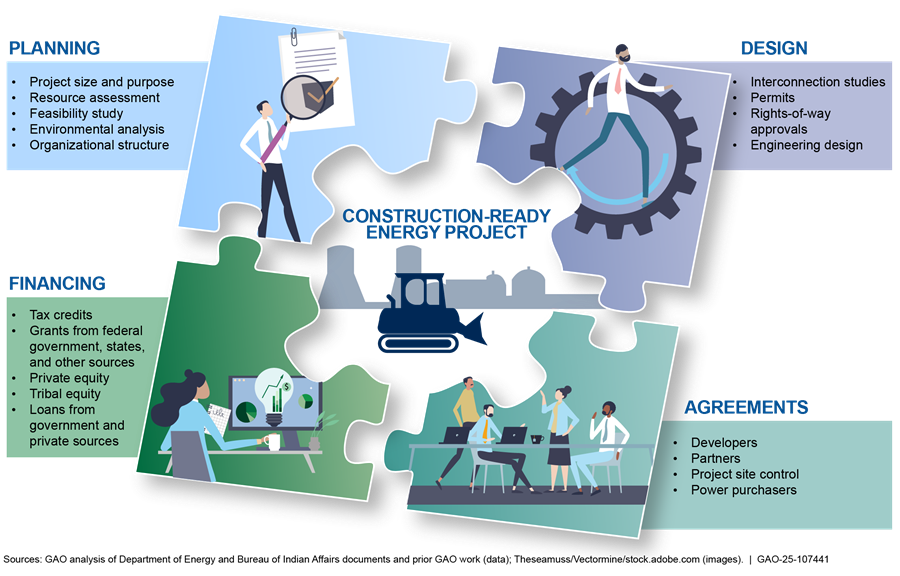

Tribal Development of Energy Projects

Developing tribal energy resources can be a complex process, and Tribes must accomplish many steps before construction on an energy project can begin (see fig. 1). For example, during the planning phase, a Tribe has to decide whether it will own the project, co-own with partners, or lease tribal land to a third party that will own the project, according to a 2023 Bureau of Indian Affairs report.[21]

Tribal ownership of an energy project has potential advantages, including more control over the design and operation of projects, direct benefit from revenue generation, and potential reduction in state and federal regulatory hurdles for projects. However, ownership carries risk. Partnerships with developers and other investors can mitigate some of the risks to Tribes, reduce Tribes’ responsibility for developing and maintaining projects, and provide a source of expertise.

Note: These steps in energy project development are generally completed before construction on a project can begin and are not linear. We identified these steps by reviewing energy project documents from the Department of Energy and Bureau of Indian Affairs and our prior work.

In determining whether to pursue a project, Tribes must evaluate the energy resources available and costs of the project, and identify project goals (e.g., selling power to a utility for revenue, providing electricity to the community, or improving local grid resiliency). Tribes conduct planning activities, including feasibility studies and other analyses, to determine the best solution to address their energy needs and to establish the technical and economic viability of a system. In addition to their own funds, Tribes may use various sources of funding for energy projects, including loans, federal or state grants, and equity from partners.

Tribes have varying levels of experience and resources for developing energy projects. Tribes have developed energy projects that range from facility- and community-scale production, such as rooftop solar panels or a wind turbine to power a community center, to utility-scale production of hundreds of megawatts of electricity. Many Tribes have developed successful economies and businesses across a variety of industries, including energy. Oil and gas resources are among the largest revenue generators for tribal lands, according to the Department of the Interior. Further, at least 70 of the 347 federally recognized Tribes in the contiguous United States have pursued microgrids—electricity systems that can operate independently of a traditional electricity grid. However, other tribal communities may need assistance developing such projects because they have no experience with energy projects or very limited financial resources to invest in designing and developing these projects.

TEFP History and Status

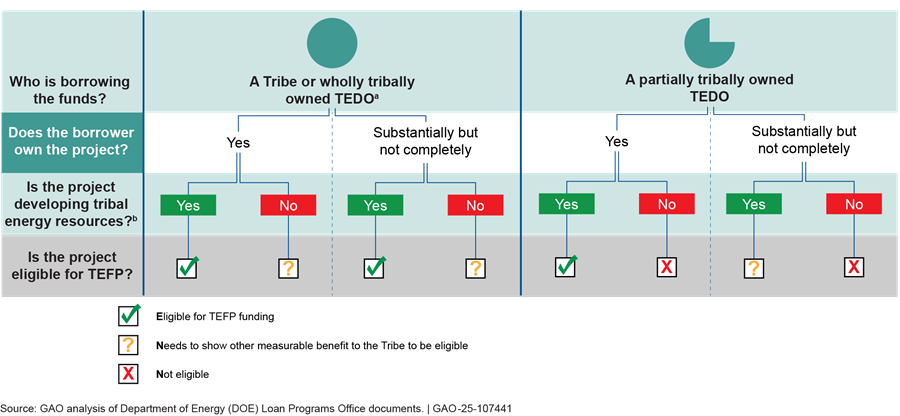

Congress established TEFP in 2005 to provide loan guarantees for energy development to federally recognized Tribes, including Alaska Native villages, as well as Alaska regional and village corporations.[22] The program is also available to tribal energy development organizations that are wholly or substantially owned by a federally recognized Tribe or Alaska Native village.[23]

Congress first funded the program in 2017.[24] LPO issued the first solicitation for TEFP in 2018.[25] Since then, TEFP has undergone several significant changes. In 2022, Congress first temporarily established TEFP’s direct lending authority, enabling the program to offer direct loans in addition to loan guarantees.[26] The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) expanded DOE’s statutory authority to provide guarantees for loans from an Eligible Lender, which, as defined in DOE’s Title XVII regulations, includes the Federal Financing Bank.[27] Permanent authority to provide loans under TEFP, in addition to loan guarantees, was provided in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023.[28] Concurrently, the IRA also expanded loan authority from $2 billion to $20 billion and appropriated $75 million for credit subsidy and to administer the program.[29] LPO announced its first conditional commitment in March 2024.[30]

Under the current administration, TEFP has experienced further changes. Since January 20, 2025, the current administration has issued executive orders and associated memos that could affect the program, including Executive Order 14154 of January 20, 2025, “Unleashing American Energy.” This executive order requires agencies to review all agency actions to identify any that impose undue burden on the identification, development, or use of domestic energy resources.[31] This order also (1) directs agencies to immediately pause disbursement of funds appropriated under the IRA or Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act; (2) directs agencies to review such disbursements for alignment with policies specified in the order, and report and provide recommendations to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the National Economic Council within 90 days of the order; and (3) prohibits agencies from disbursing such funds until the Director of OMB and Assistant to the President for Economic Policy have determined that such disbursements are consistent with any review recommendations they have chosen to adopt.[32] TEFP received IRA appropriations, which were subject to the pause and review in E.O. 14154. In July 2025, Congress rescinded the unobligated balance of TEFP’s IRA appropriations in Public Law 119-21—commonly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.[33] As a result, the program has only pre-IRA appropriations, if any remain unobligated, of $8.5 million.[34]

TEFP Requirements and Application Process

TEFP is intended to support a broad range of projects and activities to develop energy resources, products, and services. TEFP is technology-neutral, which means it offers financing for projects that use various types of energy technology. For example, Tribes may use TEFP to support electricity generation, transmission, or distribution facilities that use conventional (e.g., diesel and natural gas) or renewable (e.g., solar and wind) energy sources; energy resource extraction, refining, or processing facilities; or energy storage facilities. Eligible applicants include Tribes, tribal energy development organizations, and lenders that apply on behalf of Tribes. Eligible projects can be on or off tribal land (see fig. 2).

aA tribal energy development organization (TEDO) can include business organizations, such as partnerships, owned or partially owned by Tribes and that are established to develop tribal energy resources.

bFor the purposes of TEFP’s guidance, it would satisfy the condition of developing tribal energy resources if a project is on tribal lands, provides energy services to tribal lands, or integrates with tribal energy resources.

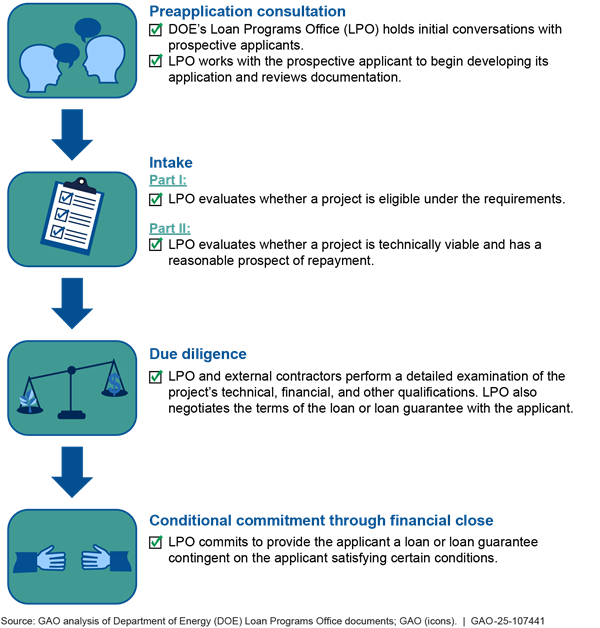

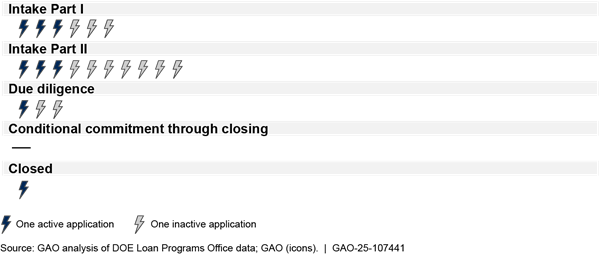

LPO offers an optional preapplication consultation for potential TEFP applicants, as it does with several other LPO programs. LPO’s loan application review process includes three phases: intake, which consists of two parts; due diligence; and conditional commitment through financial close (see fig. 3).

The phases include the following activities, according to LPO documents:

· Optional preapplication consultation. LPO encourages applicants to engage in no-commitment consultations to discuss a proposed project. In these consultations, LPO works with the applicant to determine whether the proposed project may be eligible for a loan or guarantee and assesses their readiness to apply to the program.

· Intake, part I. LPO determines a project’s eligibility, including by reviewing the technology type, project location, and tribal eligibility.

· Intake, part II. LPO assesses a project’s viability—the extent to which a project can perform adequately—against programmatic, technical, and financial criteria to determine whether to move forward with that project. During this phase, LPO makes an initial determination of whether a project will have a reasonable prospect of repayment, as well as the level of due diligence that will be required. The intake stage concludes when an applicant accepts an invitation from LPO to proceed to the due diligence stage. Alternatively, LPO can reject an application, or an applicant can withdraw its application from consideration.

· Due diligence. LPO staff perform a more detailed examination of the project’s financial, technical, legal, and other qualifications. In part, to ensure that the loan has a reasonable prospect of repayment, LPO identifies technical and project management risks and mitigation strategies, conducts a technical evaluation of the application, and proposes technical terms and conditions for a potential loan. For example, in most cases LPO commissions an independent engineer’s report to provide an independent technical review of the application.[35] LPO then negotiates the financial terms of the loan or loan guarantee with the applicant, and LPO then submits the proposed loan or loan guarantee for review and approval by OMB, the Department of the Treasury, and the DOE Credit Review Board.[36] Once they approve the application, the Secretary of Energy decides whether to offer a conditional commitment to the applicant.

· Conditional commitment through financial close. After the Secretary of Energy approves the application, LPO commits to providing the applicant a loan or loan guarantee, contingent on the applicant meeting certain terms and conditions. According to LPO documentation, examples of these terms and conditions include confirmation of project performance targets, providing a project management plan and risk mitigation plan, and confirming that the project will proceed using the identified construction budget. LPO and the applicant then sign an agreement that closes (i.e., finalizes) the loan or guarantee, and the applicant can draw on the loan, subject to the terms and conditions of the agreement.

According to LPO, once a loan closes, LPO monitors the loan through the end of its term. LPO’s monitoring activities include assessing performance against the project’s schedule and budget, according to LPO documents.

Since 2018, DOE Has Closed One Loan Guarantee and More than Half of Applications Are Inactive

From 2018 (the year the program first solicited applications) through July 2025, DOE received 20 TEFP applications for approximately $15 billion in loans and loan guarantees.[37] Of these applications, DOE closed one loan guarantee in August 2024 for $100 million for the Viejas project, a solar and long-duration storage microgrid project on tribal lands of the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians in California.[38]

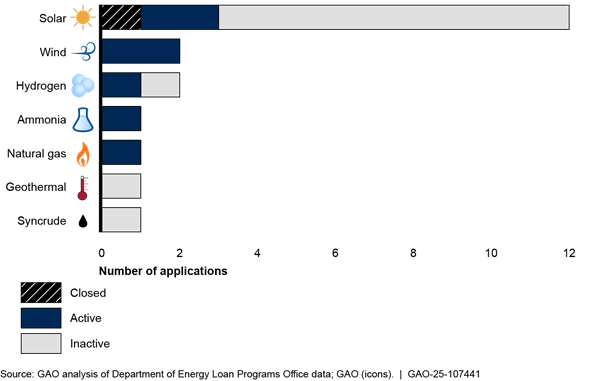

Of the other 19 applications, as of February 2025, 12 applications were inactive (i.e., put on hold, withdrawn, or abandoned). Progress on seven active applications was limited by a pause that began in January 2025 as the current administration reviewed the program. According to DOE officials, as of July 2025, the program had received no additional applications. In addition, in July 2025, all unobligated program appropriations provided by the IRA were rescinded, reducing the funding available for applications.[39] The 20 applications were for proposed projects with varying types of financing and amounts, energy technologies, energy production capacities, and locations:

|

First Approved Loan Guarantee from the Tribal Energy Financing Program: Viejas Solar Microgrid Project In August 2024, the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office (LPO) closed a $100 million partial loan guarantee for the development of the Viejas Microgrid—a 15 megawatt solar energy system plus a 70 megawatt-hour long-duration storage system—on the tribal lands of the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians in California. The project seeks to provide the Viejas Band reliable, utility-scale renewable energy generation and storage infrastructure. The project was developed to increase energy reliability for a casino—the Tribe’s primary enterprise. In the past, the casino had been cut off from transmission lines during times of wildfire danger, resulting in lost revenues for the Tribe. When the installation is complete, the Tribe should benefit from lower energy costs, according to LPO. The project is expected to generate 250 construction jobs and eight permanent operations jobs.

Viejas project battery yard. Sources: GAO analysis of LPO information; Viejas Enterprise Microgrid (photo). | GAO‑25‑107441 |

· Financing and amounts. Tribal applicants submitted applications for varying loan types and a broad range of amounts and corresponding total project costs (i.e., the loan request plus equity paid by Tribes). Four applications were for loan guarantees, and 16 were for direct loans. Loan and loan guarantee requests ranged from $23.7 million for a solar project, with a total project cost of $29.6 million, to $8.7 billion for an ammonia production facility, with a total project cost of $12.1 billion.[40] The median requested loan amount was $108 million, while the median total project cost was $177 million.

· Energy technology. Most applications (12 of 20) were for solar projects. Other technologies in proposed projects included wind, hydrogen, and natural gas. A few applicants requested financing to develop a microgrid using solar or natural gas to generate electricity. Three applications were for the development of other types of energy-related production facilities. Specifically, one application was for an ammonia production facility, another application was to develop a commercial-scale syncrude production plant that would use a carbon dioxide-to-fuels technology,[41] and a third application was for a wind turbine blade recycling facility.

· Energy production capacity. Proposed projects varied in energy production capacity. For example, 15 proposed projects that involved electricity generation ranged from 15 megawatts to 500 megawatts. The five proposed projects for energy-related production facilities ranged from 27 to 5,200 metric tons of production capacity per day.

· Location. The proposed energy projects were in various locations across the country. For instance, as noted above, the Viejas project is in California, while other projects were located throughout the continental United States and Alaska. Some projects were located on tribal lands and others were not.[42]

While Tribes had various reasons for pursuing energy projects, many proposed projects aimed to generate revenue for the Tribe and expand economic development. According to our review of TEFP application documents, 14 projects were designed primarily to earn revenue for the Tribe; three to generate electricity for use by the Tribe; and three to generate both revenue and electricity for the Tribe. For example, a hydrogen project was designed to earn revenue for the Tribe with an initial focus on selling the hydrogen to the trucking sector to use as transportation fuel. Other projects were designed to support Tribes’ electricity needs and to keep energy rates affordable for tribal members. For example, one Tribe told us it proposed a solar project to reduce its reliance on natural gas to keep customer rates as stable and low as possible, since its natural gas prices can fluctuate significantly from $1 to nearly $50 per MMbtu.[43]

As of February 2025, 12 applications were inactive for various reasons according to our interviews with tribal applicants. For example:

· A direct loan application for a solar project was put on hold because an external bank working with a project partner changed the way it evaluated loans, which created less favorable terms for the project.

· A potential borrower discontinued activity on its application after losing its agreement with a nearby city to purchase electricity from the proposed energy facility because of increased project costs and delays it said were related to unexpected TEFP requirements from LPO. For example, LPO required the potential borrower to conduct additional testing of the energy resource to be developed and tripled the equity requirement.

· Another tribal applicant abandoned its application after it learned that integrating a short-term partner with majority ownership of the project would render its proposed project ineligible for TEFP financing.[44]

Most active and inactive applications (16 of 20) remained in the intake phases of the application process as of February 2025, as figure 4 shows.

Note: This figure shows the status of 20 applications received by DOE’s Tribal Energy Financing Program as of February 2025. Active applications are project applications undergoing review by DOE and include closed loans that DOE continues to monitor through the end of the loan term. Inactive applications are those that were withdrawn, abandoned, or otherwise put on hold. According to DOE officials, as of July 18, 2025, DOE had not received any new applications for the program.

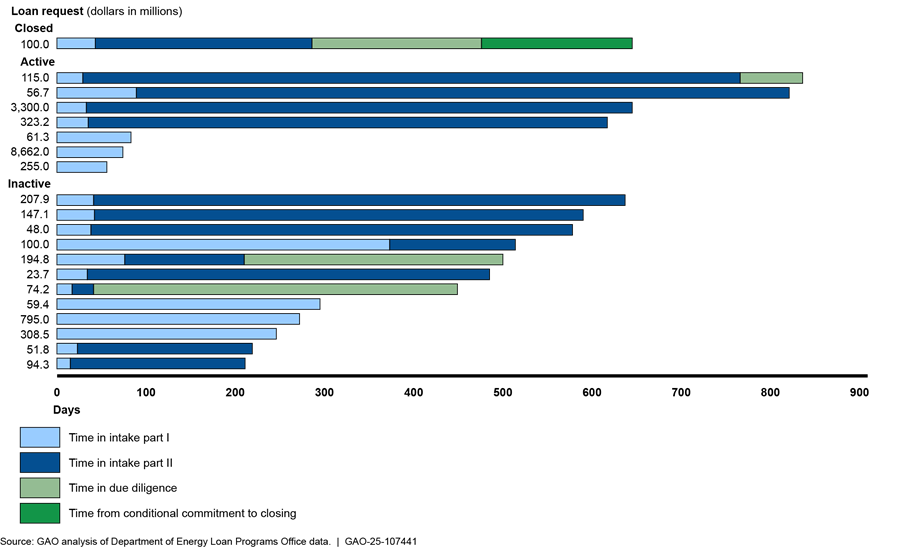

Time spent in the TEFP application process varied, with many applications spending considerable time in the intake phases. For all 20 applications, time spent in both parts of the intake phases ranged from 41 days to 821 days, as of February 2025.[45] Four applications that completed both intake phases and were further along in the process also varied in the amount of time it took to reach subsequent phases. The closed loan guarantee (for the Viejas project) took 645 days from intake to closing.

Various factors, such as project readiness and the applicant’s familiarity with the application process, can influence how quickly an application progresses, according to LPO officials. They said time spent in the application process can include extended periods of coaching and preparation and the applicant’s turnaround time to submit requested supporting materials. For example, one tribal applicant described its lengthy process for refining its project after applying for TEFP. These revisions included conducting transmission line work, developing agreements for the purchase of electricity from the proposed project, addressing challenges identifying a feasible project site, and taking steps to obtain local buy-in for the proposed project.

By March 2025—2 months after LPO paused application processing while the administration reviewed all of its programs—LPO staffing had decreased and the program was still paused. However, LPO staff were still available to meet and talk with potential participants, according to written correspondence one potential tribal applicant received from LPO in March 2025. Also as of March 2025, LPO was completing the review process and beginning to move forward with applications in the pipeline, according to LPO officials. However, in July 2025, Congress rescinded the unobligated balance of IRA appropriations for the program, reducing the funding available for applicants.[46]

Appendix I provides additional information on energy technology type, requested loan amount, application status, and time spent in each phase of the process for each TEFP application LPO has received since 2018.

TEFP Offers Tribes Financing for a Variety of Energy Projects, but Its Design Has Restrictions That Can Discourage Participation

TEFP supports large-scale tribal energy projects that can advance economic development opportunities for Tribes and that use various types of conventional and renewable technology. However, aspects of the program’s design have created significant financial barriers that can discourage tribal participation. These aspects include equity requirements, a statutory limitation on combining TEFP with certain other funds, limited project development funding, and potentially high due diligence fees. DOE’s LPO has taken some steps to help address these limitations, but Tribes continue to face barriers with accessing financing through the program.

TEFP Can Provide Financing for a Range of Tribally Led Energy Projects

TEFP can provide Tribes economic development opportunities by supporting a variety of tribally led, large-scale energy projects. These projects range from energy generation and distribution to resource extraction and processing facilities, according to a TEFP solicitation last updated in July 2023. They can incorporate conventional (e.g., oil and natural gas) and renewable (e.g., solar and wind) technologies. The economic development opportunities that these projects offer Tribes are significant, according to potential participants and tribal stakeholders we spoke to. For example:

· Reliable energy sources. One tribal applicant said its proposed energy project would help address a need for a reliable, cost-effective energy source in the local area.

· Economic diversification. One tribal stakeholder stressed that Tribes seeking to expand their economic development ventures beyond gaming could leverage TEFP for projects in the energy sector and attain substantial benefits for their Tribes. A tribal applicant said its proposed project would offer opportunities to diversify the local economy, which currently relies heavily on a single industry.

· Benefits to national economy. Projects help tap into tribal energy resources for the overall good of the U.S. economy and energy availability, according to another tribal applicant.

· Job creation. Tribal and potential applicants told us they expected their proposed projects to generate jobs for tribal members, such as temporary construction jobs and permanent jobs to manage operations. These could build careers that extend beyond those members’ reservations, they said.

TEFP’s design has several advantages, according to Tribes, including the following:

· Focus on tribal ownership. Tribal applicants cited the importance of tribal ownership for economic development prospects. One applicant estimated that owning a large-scale energy project would significantly increase the Tribe’s annual revenue, which it plans to reinvest into the community. A potential program participant said the program can accept applications from a consortium of Tribes, which enables small Tribes with limited resources to own a large-scale energy project.

· Financing for variety of projects. The ability to use TEFP to finance a range of energy projects gives Tribes more flexibility to pursue projects that leverage these Tribes’ interests and resources, according to a potential participant.

· Direct loan option. The direct loan option is useful because it eliminates the need to find a lender, one tribal applicant said. Since 2022, when Congress first authorized direct loans under TEFP, general tribal interest in the program has increased, according to LPO officials and tribal applicants.[47]

LPO Provides Flexibilities to Address Statutory Equity Requirements That Otherwise Can Be Too High for Some Tribes

A significant equity contribution requirement can limit many Tribes’ participation in TEFP. By statute, Tribes are required to pay at least 20 percent of total project costs as equity for loan guarantees, and this requirement extends to direct loans.[48] The equity requirement means that for a $100 million energy project, a tribal applicant would need to cover at least $20 million of total project costs.

This requirement can be too high for some Tribes, particularly smaller Tribes, and is a barrier to Tribes using TEFP for tribal energy projects, according to potential participants we interviewed and tribal input LPO officials told us they received on the program. As we previously reported, requirements for tribal applicants to provide a portion of total project costs are among the historic barriers to tribal participation in federal programs.[49] The restriction on combining TEFP financing with other federal funding, as we discuss below, worsened this barrier because it limited the funding sources Tribes could use to meet DOE’s equity requirements.

LPO officials said equity is an important consideration in underwriting a loan or loan guarantee because it can indicate an applicant’s creditworthiness. LPO often expects a tribal applicant’s equity to comprise more than 20 percent—and possibly as much as 30 to 50 percent—of total project costs, depending on project details and risk, according to LPO guidance and officials. LPO officials also cited OMB guidance that encourages the practice of not financing more than 80 percent of the cost of a project.[50] However, LPO officials acknowledged that such strict equity requirements may not be appropriate for tribal entities.

LPO officials told us that after discussing the issue with the Department of the Treasury, LPO recently gave tribal applicants flexibility in how they meet equity requirements. For example, according to LPO officials, borrower contributions can come from a range of sources, such as interfund transfers, bridge loans, tax equity, and state or other grants. They also do not all need to be provided by the borrower. In addition, in lieu of cash, Tribes can use in-kind contributions such as materials, land, and staff time to meet the requirement. Tribes are also allowed to count their project development expenses as equity. LPO officials said a borrower’s cash equity contribution ultimately could be as low as 5 percent, considering the specific project and factors. In October 2024, LPO began communicating these flexibilities to Tribes in conference presentations.

A Statutory Limitation Historically Restricted Tribes from Combining TEFP Financing with Other Federal Funding

One aspect of TEFP’s design that historically created a barrier for Tribes was a statutory limitation in the IRA that restricted applicants from directly or indirectly combining TEFP financing from IRA appropriations—the unobligated balance of which was rescinded as of July 2025—with other federal funds.[51] Many Tribes have limited capital and frequently combine multiple federal and other funding sources for projects to make their projects financially viable, according to tribal applicants and LPO officials. For example, Tribes may seek federal and other funding from multiple sources at different stages of the project development process to meet equity requirements, pay for project design, and complete project development activities such as environmental reviews and permitting. One tribal applicant told us that these resources are essential to making the Tribe’s projects financially viable.

|

Federal Programs That Allow Tribes to Use Other Federal Funding Sources Tribes can supplement the following federal programs with other federal funding sources: · The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Electric Infrastructure Loan and Loan Guarantee Program, managed by Rural Development, offers loans and loan guarantees to most power supply providers servicing qualified rural areas, including federally recognized Tribes. Eligible projects include construction of electric generation, transmission, and distribution facilities, including system improvements. In fiscal year 2024, $7.4 billion was available through the program. USDA may also waive program equity requirements on a case-by-case basis. · The Department of the Interior’s Indian Loan Guarantee and Insurance Program, managed by Indian Affairs, offers loan guarantees and insurance to federally recognized Tribes and individuals to secure reasonable interest rates. The program also reduces the risk to lenders by providing financial backing from the federal government. Eligible projects must benefit the economy of a reservation or tribal service area and can support a range of project types (e.g., retail, community services, and utilities) including energy projects. In fiscal year 2024, $150 million was available through the program. Sources: GAO analysis of USDA and Indian Affairs information. | GAO-25-107441 |

However, the statutory restriction made it more difficult for Tribes to apply to TEFP, according to LPO officials. Officials said that though LPO had some limited flexibilities in allowing for use of federal funding in early project development stages, Tribes could not apply for TEFP financing if they expected to receive other federal support for their project in the future. For example, one tribal applicant, whose project became infeasible in part because of increasing project costs, told us it decided not to pursue other federal funding sources that could have been helpful for its project after beginning the TEFP application process because of the restriction on combining TEFP financing with these funding sources.

Other federal programs do not have such restrictions on combining federal funds, according to USDA and Indian Affairs officials. These include USDA Rural Development’s Electric Infrastructure Loan and Loan Guarantee Program and Indian Affairs’ Indian Loan Guarantee and Insurance Program, which also provide funding for tribal energy projects under different conditions.[52]

LPO officials identified the federal support restriction as a barrier and requested that DOE raise the federal support restriction issue with Congress in fiscal years 2023 and 2024. However, DOE did not move this issue forward to Congress. DOE officials told us that DOE did not do so because the department put all proposals on hold in fiscal year 2024 because of the upcoming change in administration. In July 2025, Congress rescinded the unobligated balance of IRA appropriations for TEFP.[53] Future loans or guarantees made using existing program appropriations from another statute are not subject to this restriction.

DOE Has Not Identified and Assessed Available Options for Federal Funding and Assistance to Help Tribes Develop Projects

DOE has not taken certain steps that could help Tribes address challenges resulting from a gap in funding and assistance for them to develop energy projects that are “application ready” for TEFP. This gap limits the pool of potential applicants to the program, according to potential participants, tribal stakeholders, and LPO officials.

LPO expects applicants to its programs, including TEFP, to have projects that are well defined and significantly beyond the concept stage, according to LPO documentation and officials. For example, LPO guidance states that a well-prepared applicant will start the application process once the applicant has completed most project development activities and the project is ready for construction. Project development activities can include finalized agreements for electricity purchase; signed engineering, procurement, and construction contracts; site control; all necessary federal, state, and local permits; and interconnection agreements. Although LPO can begin preapplication consultations for prospective applicants without some of these items, the office encourages Tribes to be able to describe the status of project development activities before starting discussions.

LPO has taken some steps to help Tribes with development costs on a project-by-project basis. For example, project development costs that a Tribe incurs after it passes a Tribal Resolution to initiate project development can count toward the applicant’s required equity contribution or be included in the TEFP loan, LPO officials said.

However, because many Tribes do not have the upfront cash resources to carry out these early project development activities, the flexibilities LPO may offer do not address Tribes’ immediate needs for assistance and funding for project development activities. Project development costs can be high, particularly for items such as interconnection studies, land leases, and salaries to put deals together, according to one potential applicant. During the project development stage, a Tribe could spend a total of $10 million to $30 million to make a project “shovel ready” and sufficiently prepared to apply for TEFP, according to another tribal applicant.

Many Tribes also have limited technical expertise and resources to complete the concept planning and early project development activities needed for large-scale energy projects to apply for TEFP financing, according to potential participants and tribal stakeholders we interviewed. One stakeholder said Tribes often need assistance defining the project, who their partners will be, the estimated cost, and whether a feasibility study is needed. In addition, tribal stakeholders told us some Tribes may be reluctant to take on debt and need education on the value of loan products (versus grants) and how these products can support their energy development plans.

Some options exist for Tribes to help address these challenges. For example, the following types of resources are available to assist Tribes with developing energy projects:

· Partnerships with developers and consultants. Some Tribes have partnered with energy developers or consultants to help them further develop their projects and secure funding to pay for project development activities. For example, one tribal applicant told us it has nine partners supporting development for its project, providing technical and financial expertise.

· Nonfederal resources. For example, the Alliance for Tribal Clean Energy partnered with several philanthropic partners to establish a fund that provides predevelopment funding to Tribes to cover early project expenses for tribal clean energy projects.[54]

· Federal resources. Some federal resources may be available, depending on whether a Tribes’ project matches the program’s criteria and timing.[55] For example, within DOE, several programs may be able to support Tribes with project development for large-scale energy projects. These include an IE Tribal Energy Planning and Development grant program; the Grid Deployment Office’s Grid Resilience State and Tribal Formula Grant Program and the Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships; and DOE’s Communities Local Energy Action Program and Energy Transitions Initiative Partnership Project.[56] In addition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Energy and Mineral Development Program offers some resources.[57]

However, Tribes may need help identifying and accessing these funding and assistance options, and it is unclear how comprehensively these options would address Tribes’ energy project development support needs. In addition, one tribal energy stakeholder told us there is a gap in funding for energy project development activities, particularly for large projects where the development costs are likely to be high. This is consistent with views Tribes expressed during tribal listening sessions DOE held in 2021.[58]

LPO officials told us that as part of their outreach efforts, on a case-by-case basis, they can help identify other programs that can support an applicant’s needs for development assistance, if needed. In addition, according to LPO officials, as of March 2025, LPO had compiled a list of development grants used to support larger-scale tribal energy projects that other programs awarded from fiscal year 2021 through fiscal year 2024. They said they anticipate using this list in future outreach on the program. However, LPO did not have plans to systematically identify and assess the applicability of potential sources of federal development funding and assistance for larger-scale energy projects. As of March 2025, LPO also had not provided information to Congress on the extent to which gaps in development funding exist that could affect tribal participation in TEFP so Congress can consider addressing them.[59]

DOE’s tribal consultation and engagement order requires departmental elements to identify and reduce barriers for Tribes to accessing DOE programs.[60] This can include identifying and disseminating information on federal resources that could help Tribes conceptualize and develop energy projects that are eligible for TEFP. In addition, federal internal control standards state that management should design specific actions to help achieve objectives and respond to risks, such as by identifying and disseminating information to external stakeholders, as appropriate.[61] By identifying, with input from IE, and disseminating information to Tribes on options for funding and assistance to develop energy projects and providing information to Congress about any gaps, DOE would better address barriers Tribes face in developing projects with the scale and level of readiness needed to apply to TEFP. Addressing these barriers could expand TEFP’s pipeline of future projects and help ensure more Tribes can benefit from the program.

Potentially High and Unpredictable Due Diligence Costs Can Pose a Barrier for Tribes

High and unpredictable due diligence costs pose another barrier to Tribes seeking to participate in TEFP. Specifically, DOE requires tribal applicants to pay fees and expenses for external legal and expert services (e.g., technical, financial, and environmental), as needed, that help DOE evaluate projects and requested financing.

However, the level and unpredictability of due diligence costs discourages Tribes from applying to TEFP, according to potential participants and stakeholders we interviewed. One Tribe that decided not to apply to the program noted that the costs could translate into millions of dollars, making it difficult for Tribes to plan. Another tribal applicant with previous experience seeking energy financing noted that the expected due diligence costs under the TEFP application were double what it would expect from other financing sources for its proposed energy project. This Tribe told us it likely would withdraw its TEFP application in part because of the high application costs.

Furthermore, another tribal applicant told us that the contracted legal counsel DOE uses for all legal work related to TEFP loan issuance was not sufficiently knowledgeable about the particulars of tribal law and energy projects, resulting in a steep learning curve and by extension more hours billed to the Tribe. In addition, the applicant noted that there was no incentive for LPO or its contracted counsel to keep legal costs as low as possible. As noted, under the terms of the TEFP solicitation, applicants, borrowers, or project sponsors are responsible for the costs of independent legal counsel and other consultants whom DOE may engage for its due diligence.

In contrast, according to USDA and Indian Affairs officials, other federal loan and loan guarantee programs that issue loans to tribal applicants complete underwriting in-house and have limited or no additional due diligence fees. For example, USDA’s Electric Infrastructure Loan and Loan Guarantee Program and Indian Affairs’ Indian Loan Guarantee and Insurance Program are two such programs. These programs can provide financing for projects of comparatively similar dollar size to some TEFP projects.[62]

For higher-risk, higher-cost projects (e.g., using new technologies and costing hundreds of millions or billions of dollars), LPO may need to use external legal counsel and other technical experts. However, according to LPO officials, review by external consultants may not be as necessary for lower-risk tribal energy projects that use established technologies or are lower cost. The officials said that LPO may be able to achieve an appropriate amount of due diligence at a lower cost to Tribes for lower-risk projects.

DOE has begun taking some steps to address this issue, but these efforts have not been finalized and their effectiveness is uncertain. For example:

· In its program solicitation, DOE states it seeks to keep due diligence costs to less than 1 percent of the loan request and to avoid requiring nonlegal consultants for projects with total costs of less than $25 million. However, for larger projects, the program solicitation does not limit due diligence costs, making them unpredictable and potentially high. For example, projects with loans greater than $100 million could have due diligence fees and expenses much greater than 1 percent of the loan request, amounting to well over $1 million. These can be substantial costs for tribal applicants.

· DOE plans to apply $5 million in technical assistance funding to help tribal applicants develop their application materials before the due diligence phase. DOE said this could help reduce overall application preparation costs for tribal applicants, which would help offset due diligence work and associated costs charged to tribal applicants. However, it is uncertain whether this initiative will be completed before September 30, 2025, the deadline for obligating fiscal year 2024 annual appropriations.[63] In October 2024, DOE published a solicitation for contractors to provide assistance to Tribes that submitted intake part I materials but were facing financial barriers to meeting intake part II requirements. As of July 2025, DOE had not taken additional steps to award a contract and obligate this funding because of a pause in issuing new contracts by the current administration. As of July 2025, DOE officials said they were continuing to work with applicants to determine their interest in, and readiness for such funding, but the funding’s status for fiscal year 2026 was uncertain.

|

Public Finance Public finance is a lending model that public bodies—cities, states, and Tribes—use to finance projects that have a public purpose, such as stadiums, roads, and infrastructure. According to LPO documentation, public finance debt is considered less risky than other types of debt LPO handles because public bodies often cannot declare bankruptcy, and they have access to additional streams of revenue to pay their loans, such as utility revenues, fees, and taxes. Tribes may also have revenue from other tribal businesses, including gaming, government contracting, hospitality, tourism, agriculture, and energy. Source: GAO analysis of LPO documentation and prior GAO work. | GAO‑25‑107441 |

· LPO is developing a public finance “application pathway,” which it identified from USDA tribal lending programs. LPO’s typical pathway assumes a riskier corporate finance project structure. In contrast, the public finance pathway would support lower-risk projects—such as projects that are smaller scale or use established technologies—that are backed by a Tribe’s government. Implementing a second pathway for Tribes could resolve some barriers, according to LPO officials. For example, this pathway would require less overall due diligence—and thus lower fees and expenses—and reduce application time frames. As part of this effort, LPO officials told us they were developing options to limit the use of external contractors for lower-risk projects. These options include reducing the scope of work that external contractors perform or performing certain tasks internally. As of March 2025, LPO was working with one Tribe that was interested in testing use of the approach, but details and guidance remained undetermined and LPO officials said that the viability of the pathway was uncertain.

DOE’s tribal consultation and engagement order requires departmental elements to identify and reduce barriers to accessing DOE programs.[64] In addition, E.O. 14058 states that agencies’ efforts to improve federal customer experience should include identifying and resolving the root causes of customer experience challenges, regardless of the source—including budgetary or process-based sources.[65] Until LPO further develops and implements options to revise its due diligence review processes to reduce or eliminate due diligence fees and expenses for TEFP applicants, Tribes may continue to avoid applying to the program because of uncertainty about the costs of securing the loan. As a result, they may miss opportunities to develop untapped energy resources that could help stabilize energy costs and spur local economic development, as well as provide jobs for tribal members.

Tribes Experience Barriers Because of Complex and Unclear Agency Processes That Can Derail TEFP Applications

DOE has improved its outreach to Tribes about TEFP, but barriers remain that can hinder Tribes’ ability to complete the application process and close on loan guarantees or direct loans. For example, the application process is long and complex, and LPO does not have clear program guidance or staff with tribal experience to review applications. These barriers have created uncertainties for potential participants, lengthened application time frames, and may have reduced interest in the program.

TEFP Has Improved Outreach to Potential Participants

LPO has taken steps to enhance outreach to potential participants. In 2021, LPO created a dedicated team responsible for conducting outreach and managing relationships with potential participants. These staff connect with potential participants at conferences and events to generate interest in the program and meet one-on-one with prospective applicants to assess their projects and help them with their applications. In addition, once a tribal applicant submits its application, outreach staff do an initial review of the application and help applicants in the early stages of the process.

Potential participants and stakeholders told us that, overall, DOE is actively recruiting Tribes for the program. They also said DOE staff have been good at following up with prospective applicants, responsive to applicant requests for meetings, and helpful in brainstorming ideas. Applicants reported that LPO reached out to them individually to discuss TEFP, including suggesting potential project partners. Other applicants and potential participants reported that outreach staff scheduled regular meetings with them to discuss the progress of their applications.

DOE Has Not Implemented Changes to Address Tribal Concerns About the Length and Complexity of the Application Process

Tribes expressed concerns about the length and complexity of the TEFP application process, which they indicated can be burdensome for participants. Lengthy application processes have resulted in delayed project timelines, increased project costs, and loss of project partners in some cases, according to potential participants.

For example, one tribal applicant said it lost its power purchaser and access to a multimillion-dollar bridge loan because of the long application process, which made its project unviable. Another potential participant said it lost its project partner and its place in the interconnection queue because of LPO delays in deciding whether the project was eligible for financing. In both cases, the interviewees said LPO officials had given them the impression that their project was likely to receive financing; otherwise, they would not have put as much time and effort into the application process. Potential participants also said that LPO sometimes took months to find answers to their questions about their applications, which lengthened the process.

The two intake steps in LPO’s application process can each take substantial time, according to our analysis of TEFP applications. LPO guidance indicates that the two intake steps can take a total of 90 business days or longer. Our analysis found that the median time in intake was 334 days (see app. I for more information). The Viejas project, the only application to complete the full process, spent 286 days in intake and 359 days in due diligence and conditional commitment—a total of almost 2 years (645 days) from entering intake to closing. LPO officials noted that these timelines may include extended periods of guidance and preparation to assist applicants with their applications, as well as the applicant’s turnaround time to submit additional application support documents.

Tribal applicants we spoke with indicated that the ongoing cost of project development over such long time frames requires a lot of financial resources from the Tribe. For example, one applicant said LPO required it to provide vendor contracts during intake. Such contracts typically require payment within a few weeks, so the applicant must pay those project costs up front while waiting for LPO to review its application, with no certainty that LPO will approve these costs, the applicant said. The applicant told us that based on the continued uncertainty and slow application process with DOE, it planned to pursue other funding options that had more efficient processes. LPO officials said they require certain contracts to be in place as an indication that a project is mature enough for financing. They also said they are aware that this is an ongoing cost for tribal applicants.

In addition to concerns about the overall length of the application process, tribal applicants also expressed concerns about its complexity. The TEFP application process involves multiple stages of review and feedback, including redundant information requests, according to our review of program documents. LPO officials said they were aware that applicants could misunderstand the iterative process. Tribal applicants’ concerns included the following:

· One potential participant noted that LPO officials were repeating questions about the project’s eligibility, even after 6 months of preapplication consultations. This reduced the potential participant’s confidence in the officials’ understanding of the process.

· LPO’s intake process requires tribal applicants to submit an executive summary twice, which one applicant found duplicative.

· The timing of LPO’s review process was out of sync with the realities of the lending and project development process, which added complexity, according to some applicants. For example, one applicant said it was required to provide actual quotes for work costs earlier in the process than appropriate, since getting quotes is an iterative process as the project’s design details develop.

One potential participant said that because of this complexity, many Tribes do not have the capacity to move through the application process without third-party assistance—which costs significant amounts of money that the Tribe often must pay before it can submit an application. LPO officials said they understood that tribal applicants might see the program as complex, but that to be successful, applicants must complete significant work up front with the aid of legal counsel, engineering firms, and consultants.

According to LPO officials, LPO based the TEFP application process on the model it used for its Title XVII Clean Energy Finance Program. This program serves both clean energy and infrastructure reinvestment projects by providing financing for projects that may not otherwise be able to secure commercial financing, according to program guidance. For example, some projects must deploy innovative technology to be eligible for Title XVII support. However, LPO officials said TEFP projects—particularly those that are smaller, lower cost, and use proven technologies—could benefit from alternative application review approaches that are commensurate with their lower risk.

LPO is taking some actions to revise its application processes, including identifying timeliness goals, but these steps may not be sufficient to address Tribes’ concerns. In addition, one of the actions has not been finalized or fully implemented. For example:

· Adjusting rigor of review. LPO implemented a classification system for all its programs, including TEFP, that adjusts the rigor of LPO’s due diligence review depending on the type of project proposed, according to LPO documentation. For example, innovative, technologically complex projects will receive higher levels of review than projects that will use technologies already in use, according to LPO documentation. As part of this effort, LPO identified target review timelines for due diligence, based on private sector benchmarks and input from LPO staff. However, LPO officials said these efforts have not resulted in shorter reviews for TEFP applications.

· Second application pathway. In late 2024, LPO identified two applicants to test the new public finance application pathway intended to support lower-risk, Tribe-backed projects and shorten review times, as described above. However, these applicants withdrew from the program after learning that LPO could not guarantee that it would meet the timelines the applicants needed for financing. LPO has since selected another application currently in due diligence to test some features of the pathway. However, LPO officials said they were not yet certain whether the pathway would be viable and had not begun developing formal documents to guide the effort. Further, to effectively implement the pathway, TEFP needs outreach and underwriting staff who are trained in public finance, which LPO currently does not have, according to LPO officials.

We have previously reported that agencies can encounter challenges implementing programs for Tribes when programs are structured for other entities, such as states or corporations, and do not consider the unique circumstances of tribal governments or tribal economies.[66] Further, Tribes can have limited administrative capacity to navigate complex programs. Managing administrative burdens, such as application requirements designed for other entities, can strain Tribes’ staffing capacity and limit their access to needed federal assistance. Some agencies have minimized this burden by streamlining applications.[67]

DOE’s tribal consultation and engagement order requires that departmental elements purposefully seek to identify and reduce as many barriers as possible to meaningful participation in and access to DOE’s program opportunities, including, but not limited to, funding opportunities.[68] Such action is consistent with E.O. 14058, which states that agencies’ efforts to improve customer experience should include reducing administrative hurdles and paperwork burdens to enhance transparency and minimize time lost waiting on application processing.[69]

Until DOE takes steps to reduce the length and complexity of LPO’s application processes for lower-risk tribal energy projects, LPO may face challenges meeting its timeliness goals and Tribes may continue to experience delays and administrative burdens in TEFP application processes that can derail their projects. This may reduce confidence in the program and discourage other Tribes from applying to the program in the future.

Unclear and Changing Internal and External Guidance Contributes to Confusion About Program Requirements

Tribal applicants we interviewed have experienced communication challenges with LPO throughout the application process. For example, they said they received different information from different LPO officials about certain program rules, such as equity requirements or whether TEFP could cover development costs.

Individual tribal applicants reported being told the following:

· The loan could be used for development costs, such as environmental reviews, site control leases, and legal costs. However, LPO later told the applicant that such costs were not covered. When the applicant stated it could no longer move forward with the loan without help with development costs, LPO agreed to cover the costs.

· The original terms of the draft agreement had to be changed because they were against regulations. LPO retracted the change after the applicant asked to see the regulations and LPO consulted counsel.

· The program would cover 100 percent of the applicant’s project’s costs. Later, the applicant was told the loan would only cover 80 percent, and it had to quickly get another loan to cover the equity difference. The applicant said the lack of clear requirements made applying to the program challenging.

LPO also seemed to frequently add new or unexpected requirements during the application process, tribal applicants said. For example:

· Each time an applicant met with LPO, the office introduced additional financing conditions, according to the applicant. Sometimes as many as 50 conditions were introduced simultaneously, requiring the applicant to spend additional time and money on its application.

· LPO’s outreach and underwriting teams had different understandings of the program, another applicant said. This resulted in unexpected requirements when the project moved into later stages of the application process.

LPO’s guidance is not clear on some TEFP requirements, as we found during our review of LPO program documents. For example:

· Loan sizes. One external guidance document that LPO provides to TEFP applicants states that LPO loans are less attractive to borrowers for projects under $100 million and that the smallest loan requests are typically at that size, while another document discusses projects that are less than $25 million. According to potential participants and stakeholders, some Tribes may prefer smaller projects, and a lack of clarity on loan sizes could discourage such Tribes from participating if they are uncertain whether their project is large enough to be eligible. For example, according to one tribal applicant, LPO officials told the applicant that its project likely would not be prioritized because of the project’s small size, which created uncertainty for the applicant.

· Equity. A DOE presentation about TEFP requirements states that the 20 percent equity requirement for TEFP can be funded by a variety of sources, including bridge loans. However, another guidance document LPO provides to TEFP applicants states that equity may not include the proceeds from other loans.

· Technology types. The TEFP solicitation states that the program can finance multiple technology types. However, there is uncertainty whether all technologies will continue to be eligible. In March 2025, one Tribe received written correspondence from LPO stating that DOE was prioritizing certain energy technologies such as nuclear, critical minerals, transmission, and natural gas. Further, the status of projects using other technologies, such as wind, was uncertain because of a January 20, 2025 Presidential Memorandum suspending leasing and permitting of offshore and onshore wind energy projects.[70] In March 2025, when we asked LPO officials if DOE was prioritizing certain technologies, they said their goal was to support all projects eligible under the law—including conventional sources such as natural gas, as well as renewables such as wind and solar.

· Requirements for outreach and intake. Some LPO staff told us they did not have internal clarity on TEFP requirements because until recently the program did not have established procedures and best practices for outreach and intake to draw on from previously closed loans. For example, they said that it is difficult to know when to involve other LPO staff with specific expertise. In one instance, an applicant was months into the application process before the correct technical staff were brought in, and these staff determined that the project’s technology was not eligible. LPO staff said they should have been able to let the Tribe know earlier in the process that the project was not eligible.

Further, in 2024, LPO introduced an initiative to focus its efforts on high-quality applications, which would help the office make sound loans to protect the taxpayers’ interest, according to LPO officials. However, this additional change could make some applicants feel like LPO was moving the goalposts, which could undermine their confidence in LPO, according to LPO staff. It could also discourage Tribes that could meet the basic requirements in the solicitation but might struggle to meet the new standards.

LPO is taking steps to correct misconceptions it believes exist about program requirements, but it has not documented updated information for the benefit of tribal applicants. LPO has begun verbally clarifying several internal misconceptions about project development costs, project sizes, and equity requirements, according to LPO officials. Officials also began sharing information about these elements verbally at conferences and in meetings with Tribes. LPO officials have been working on an updated TEFP solicitation to address other changes that LPO is considering, including the public finance pathway, but said they do not expect the new solicitation to include information that would correct prior misconceptions about program requirements. Further, LPO is making other changes to TEFP such as adding technical assistance funding, which may require additional updates to guidance.

In our May 2025 report on LPO’s loan programs, we found that LPO’s application review guidance was outdated and did not always match practice and that LPO guidance and procedures could not ensure LPO staff consistently and accurately implement application reviews.[71] We recommended that LPO undertake a comprehensive annual review to identify and correct errors in application review guidance. Further, according to standards for internal control, management should periodically evaluate the entity’s methods of communication so that the organization has the appropriate tools to communicate quality information throughout the entity on a timely basis, and externally communicate the necessary quality information to achieve the entity’s objectives.[72]

Without developing, documenting, and distributing accurate program guidance, LPO cannot ensure its staff consistently apply program requirements and provide Tribes with complete and accurate information about TEFP processes and requirements. Without such information, Tribes may be discouraged from applying to TEFP or continue to experience barriers to completing their applications and receiving financing for energy projects that can provide them critical economic opportunities.

DOE Has Few Designated Staff with Tribal Experience to Review TEFP Applications

Most LPO staff reviewing TEFP applications have limited experience in tribal energy finance, according to our analysis of LPO staffing practices. As of May 2025, LPO had designated 12 of its 274 federal staff to focus primarily on TEFP or to work for the program on a recurring basis. Of these, two outreach positions were staffed to work solely with TEFP, but both were vacant.[73] LPO’s outreach staff for TEFP are hired for their tribal cultural competency and receive in-house training on energy projects and finance.

In 2023, LPO began designating staff for TEFP in other offices that review TEFP applications, according to our analysis of LPO staffing documents. As of May 2025, these offices had 10 staff positions that supported TEFP on a regular basis. However, these staff were shared with other programs, their positions have not been filled consistently, and as of May 2025, more than half were vacant. For example, according to our analysis of LPO staffing documents:

· Legal. LPO created a designated legal staff position for TEFP in 2023, but this position remained vacant until late 2024. During 2024 and 2025, LPO hired two tribal legal specialists for the position, but both left LPO, according to LPO officials and staffing documents. As of May 2025, LPO staffing documents no longer had a designated legal staff position for TEFP.

· Origination. In 2023, LPO created designated origination staff positions for TEFP, which are shared with other LPO programs. As of May 2025, LPO’s origination division had five staff positions, but four of those positions were vacant.

· Technical and Environmental. In late 2024, LPO created designated technical and environmental staff positions for TEFP, which are shared with two other LPO programs. As of May 2025, LPO’s technical and environmental division had four staff positions for TEFP, all of which were filled.

LPO’s practice is to assign staff to projects based on availability, without prioritizing tribal expertise, according to LPO officials. This currently includes LPO’s legal and risk management divisions. Until recently, it also included LPO’s origination and technical and environmental divisions. For example, LPO officials said TEFP applications would be supported by other LPO legal staff and contracted tribal legal experts, absent a TEFP legal position.

LPO has provided its staff with general training about working with Tribes and recently began providing some staff with specific training on working with Tribes that addresses topics such as awareness of tribal law and government procedures. For example, in 2024, LPO began providing origination staff with specialized training on tribal consultation, treaties, and rights, according to LPO officials.