MEDICAID DEMONSTRATIONS

Action Needed to Address New Cost Concerns

Congressional Requesters

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-25-107445, a report to congressional requesters.

For more information, contact: Michelle B. Rosenberg at RosenbergM@gao.gov.

Why This Matters

Medicaid section 1115 demonstrations allow states to test new approaches for delivering services and have become a significant feature of the program. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) policy is for demonstrations to be budget neutral (i.e., not raise costs for the federal government). We have previously recommended CMS use valid methods to determine budget neutrality.

GAO Key Takeaways

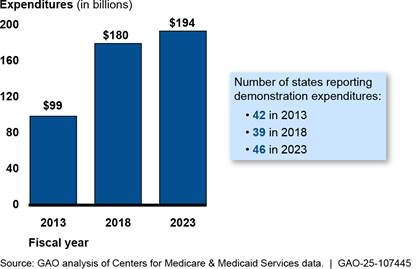

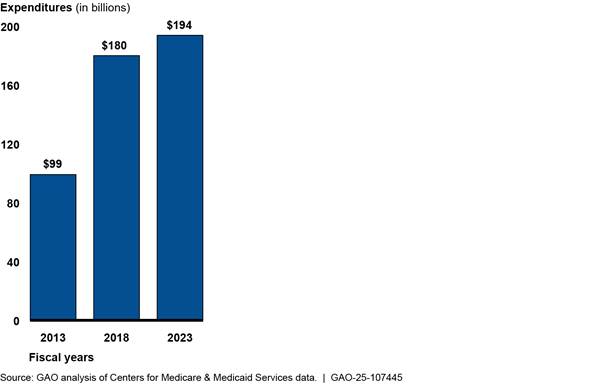

Federal spending on Medicaid demonstrations nearly doubled from 2013 through 2023—the latest available data. CMS sets spending limits for each demonstration that are intended to ensure that demonstrations are budget neutral. The limits are based on projections of what Medicaid would have spent without the demonstration. The higher the projected spending, the higher the spending limit.

In 2021, CMS began requiring states to use recent spending data rather than outdated historical spending projections when calculating spending limits—a method that better ensures budget neutrality. We estimated that this reduced potential federal spending by about $123 billion for two selected demonstrations.

However, in 2022, CMS adjusted this policy and allowed spending limits to partially reflect outdated historical spending projections. This increased potential federal spending by an estimated $17 billion in three selected demonstrations.

Also in 2022, CMS began allowing spending limits to include certain costs for services to address health-related social needs, such as housing assistance. Some of these costs could not have occurred absent the demonstration because they are not allowable under Medicaid. This increased potential federal spending by almost $4 billion in five selected demonstrations and did not ensure budget neutrality.

Federal Expenditures Under Medicaid Demonstrations

Note: Expenditures are adjusted for inflation.

How GAO Did This Study

We analyzed CMS expenditure data on Medicaid demonstration spending. We reviewed CMS policy changes from 2020 through 2024 and approval documents for six state demonstrations, selected for variation in approval dates. We estimated how the changes in CMS policies would affect federal spending.

What GAO Recommends

CMS should fully implement our 2002 recommendation to use valid methods for budget neutrality. CMS should also stop allowing costs that could not occur absent the demonstration in demonstration spending limits. CMS said it will consider this as it implements new budget neutrality requirements.

Abbreviations

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

HRSN |

health-related social needs |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 16, 2025

Congressional Requesters

Medicaid section 1115 demonstrations—which allow states to test and evaluate new approaches for delivering services under the federal-state Medicaid program—have become a significant feature of the program.[1] Under section 1115 of the Social Security Act, the Secretary of Health and Human Services may waive certain federal Medicaid requirements and approve new types of expenditures that would not otherwise be eligible for federal Medicaid matching funds for experimental, pilot, or demonstration projects that in the Secretary’s judgment are likely to promote Medicaid objectives.

The Secretary delegated responsibility for overseeing Medicaid demonstrations to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that oversees the program. CMS has approved demonstrations for a variety of purposes. For example, under demonstrations, states have extended coverage to populations or for services not otherwise eligible for Medicaid, made payments to providers to incentivize delivery system improvements, and introduced new requirements for enrollees. Demonstrations vary in size and scope and can be comprehensive in nature, affecting multiple aspects of states’ Medicaid programs. As of May 2025, nearly every state had an approved Medicaid section 1115 demonstration.

CMS policy requires that demonstrations be budget neutral to the federal government; that is, the federal government should spend no more for Medicaid under a state’s demonstration than it would have spent without the demonstration.[2] Once approved, each demonstration operates under a negotiated budget neutrality agreement that places a limit on federal Medicaid spending over the life of the demonstration, generally 5 years. The spending limit set by CMS is generally based on projections of what the state’s existing Medicaid program would have cost the federal government absent the demonstration.

CMS’s budget neutrality policies, including the methods used to set demonstration spending limits, have significant implications for the level of federal spending under demonstrations. For example, we have previously found the base year used and the growth rate that CMS applies in projecting spending over the life of the demonstration can add billions to demonstration spending limits.[3]

Historically, CMS’s budget neutrality policies have not been defined in statute or regulations and have not always been transparent. As such, the implications of policy changes are not always clear.[4] For example, in January 2021, CMS implemented a change—first announced in 2016—to how it sets spending limits when states seek to extend a demonstration. In September 2022, CMS began implementing additional changes to this and other budget neutrality policies. CMS issued guidance communicating those changes and their applicability across demonstrations in 2018 and 2024, respectively.[5] However, there are no publicly available estimates of the effects of those policy changes on spending under demonstrations.

You asked us to examine the potential effects on federal spending of changes CMS has made to its budget neutrality policies. This report

1. describes how spending on Medicaid demonstrations has changed over time; and

2. examines how changes CMS made to its budget neutrality policies over the last 5 years could affect federal spending.

To describe changes in Medicaid demonstration spending over time, we analyzed state-reported expenditure data from CMS’s Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System.[6] We analyzed data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia for fiscal years 2013 through 2023 (the most recent year of sufficiently complete data at the time of our review), including demonstration spending and total Medicaid expenditures.[7] We analyzed the federal share of demonstration expenditures nationwide and variation in expenditures across states.[8] We also interviewed CMS officials about factors that affected demonstration spending over time. To assess the reliability of the federal expenditure data, we reviewed related documentation, including the forms used to collect the data and their instructions, and the steps CMS takes to ensure data reliability. We also interviewed and obtained written responses from knowledgeable CMS officials about the data. We determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for our purposes.

To examine how changes CMS made to its budget neutrality policies over the last 5 years could affect federal spending, we reviewed CMS policy changes from 2020 through 2024, including CMS’s guidance to states that outlined the agency’s changes to its budget neutrality policies. In addition, we reviewed demonstration approval documents that included information on the amounts states could spend under the demonstrations. This included analyzing CMS worksheets documenting their calculations for setting demonstration spending limits for a nongeneralizable sample of six selected state demonstrations. Using those worksheets, we compared approved spending limits to what those limits would have been absent the policy changes and estimated the federal share of any differences in expected spending.[9] We selected the demonstrations to ensure a mix of those approved under the 2021 change to CMS’s budget neutrality policies (Arkansas, New York, and Tennessee) and those approved after the September 2022 policy changes (Arizona, Massachusetts, and Washington).

Our analysis was based on the terms and conditions applicable to each selected demonstration as of July 2024, including any amendments that affected the states’ budget neutrality agreements. In addition, where possible, we estimated the effect of the policy changes on demonstration spending limits beyond our selected state demonstrations using publicly available information. We also interviewed state Medicaid officials from the states for the six selected demonstrations and CMS officials about CMS’s budget neutrality policies and processes for setting demonstration spending limits. Finally, we reviewed past GAO findings on CMS’s approval of demonstrations and assessed the policy changes against CMS’s policy goal that demonstrations be budget neutral to the federal government. See appendix I for background information about the six selected demonstrations, including their approval dates and effective periods.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 through September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Medicaid is a health care program that is jointly financed by the federal government and states. States receive federal matching funds for state spending to provide coverage for enrollees. Medicaid enrollment totaled 71.5 million individuals as of December 2024.

Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstrations

As of May 2025, 48 states and the District of Columbia operated at least part of their Medicaid programs under demonstrations. As previously noted, state demonstrations can vary in size and scope, and many demonstrations are comprehensive in nature, affecting multiple aspects of states’ Medicaid programs. CMS typically approves demonstrations for an initial 5-year period that can be extended in 3- to 5-year increments with CMS approval.[10] Some states have operated some or all of their Medicaid programs under section 1115 demonstrations for decades.

Each demonstration is governed by special terms and conditions that reflect the agreement reached between CMS and the state, and describe the authorities granted to the state. For example, the special terms and conditions may define what demonstration funds can be spent on—including which populations and services—as well as specify spending limits. A state can seek to make changes to its demonstration, including substantive modifications, by submitting a request to amend the demonstration to CMS for review and approval.

Budget Neutrality and Demonstration Spending Limits

CMS policy requires Medicaid spending under a demonstration be budget neutral to the federal government, meaning that the federal government will spend no more under a state’s demonstration than it would have spent without the demonstration.[11] CMS requires states to show that their demonstrations will be budget neutral as part of their application.

Once approved, each demonstration operates under a negotiated budget neutrality agreement that places a limit on federal Medicaid spending over the life of the demonstration. This limit is referred to as the demonstration spending limit. According to CMS policy, the spending limit for a demonstration is to be based on the projected cost of continuing the state’s existing Medicaid program without a demonstration. The higher these projected costs, the higher the spending limit, and the more federal funding states are potentially eligible to receive for the demonstration in the form of a federal match on their actual expenditures.

Demonstration spending limits are set in different ways. CMS can approve a per person per month limit that sets a dollar limit for each Medicaid enrollee included in the demonstration; CMS can set an aggregate dollar amount for the entire demonstration period regardless of the level of enrollment; or CMS can use a combination of a per person limit for some costs and an aggregate limit for others.

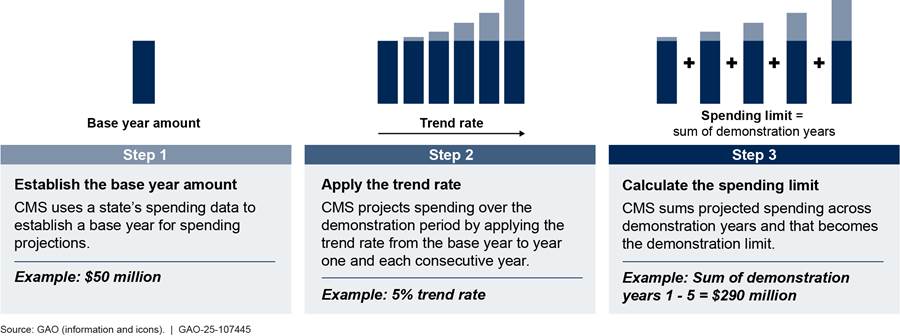

In general, CMS calculates demonstration spending limits by establishing a base year spending amount, which reflects spending for each population included in the proposed demonstration. To account for expected cost growth, CMS then applies a trend rate, which can vary by population, to estimate spending for each year of the demonstration. The sum of projected spending across the demonstration period serves as the spending limit.[12] The decisions by CMS regarding which costs it allows states to include in the base year and which trend rates to apply affect the size of demonstration spending limits. (See fig. 1).

Note: Figure depicts the process used by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as of May 2025. For demonstrations that include multiple populations, steps 1 and 2 are performed for each population.

To establish the spending limit, states provide CMS with recent data on their spending for the populations included in the proposed demonstration, referred to as the base populations. Historically, CMS has also allowed states to add amounts the state did not actually expend, but hypothetically could have spent for populations or services otherwise allowable under Medicaid, referred to in this report as “hypothetical costs.” By adding these hypothetical costs to the spending limit, the state is given additional spending authority to provide these services under the demonstration.[13]

Changes in Budget Neutrality Policies Over Time

CMS’s stated policy has long been that demonstrations are to be budget neutral. The agency’s budget neutrality policies, particularly policies for setting spending limits, have changed over time. When CMS announces a policy change, the agency generally begins applying it as applications for new demonstrations or when extensions of existing demonstrations are submitted. CMS has made a number of changes to its budget neutrality policies over the last 5 years, one of which the agency began applying in January 2021 and others the agency began applying in September 2022.

· Base year spending. Beginning with demonstration extensions approved in 2021, CMS began requiring that states use recent, actual spending data when establishing the base year spending amount for the demonstration extension period.[14] Prior to this change, for states applying to extend their demonstrations, CMS had allowed states to further trend their historical spending projections forward to serve as the base year. Then, in September 2022, CMS revised this policy once more, allowing spending limit calculations to partially reflect states’ historical spending projections. Specifically, under the 2022 policy, rather than solely using recent, actual spending data, the base year is composed of a weighted average of recent, actual spending data (80 percent) and states’ historical spending projections (20 percent).

· Trend rates. Prior to September 2022, CMS applied the lower of the states’ historical spending growth or the President’s Budget trend rate for each Medicaid population under the demonstration when calculating spending limits.[15] Beginning in September 2022, CMS began applying the trend rate from the President’s Budget proposal in all cases (e.g., regardless of whether it was higher or lower than the state’s historical spending growth for a given population).

· Hypothetical costs. In September 2022, CMS began allowing states to include new types of hypothetical costs in their demonstrations, including costs, subject to limits, for services to address enrollees’ health-related social needs (HRSN), such as housing and food supports.[16] In addition, beginning in January 2023, CMS began treating as hypothetical costs for pre-release services for incarcerated individuals, such as behavioral health services for individuals in the 90 days preceding their release from incarceration.

CMS initially communicated these changes in its approval letters to states for individual demonstrations. The agency issued a letter to state Medicaid directors in August 2024 clarifying their current budget neutrality policies, including these changes as well as others.[17] Additional changes noted in the letter include the following:

· Allowing states to seek mid-course corrections to budget neutrality terms, including spending limits, without having to submit an amendment, which would otherwise be subject to certain transparency requirements.[18]

· Changing the extent to which any unused spending authority can be carried over by a state from one demonstration approval period to the next. Specifically, in 2022, CMS began allowing states to carry over unused spending authority from the previous 10 years of a demonstration, rather than just the previous 5 years, which had been its policy since 2016. See appendix II for additional information on this change.

Recently enacted legislation includes a statutory budget neutrality requirement effective in 2027.[19] When that provision of the law goes into effect, it will prohibit the approval of demonstrations unless CMS’s chief actuary certifies that they are budget neutral. It is too early to know how CMS will change its budget neutrality policies as a result of the act.

Federal Medicaid Demonstration Spending Nearly Doubled from 2013 through 2023

Federal spending under section 1115 Medicaid demonstrations nearly doubled from about $99 billion in fiscal year 2013 to about $194 billion in fiscal year 2023, though the growth in spending was smaller over the second half of this time period.[20] (See fig. 2.) The number of states reporting demonstration expenditures fluctuated during this period, with 42 states reporting expenditures for fiscal year 2013, 39 states for fiscal year 2018, and 46 states for fiscal year 2023.

Figure 2: Federal Expenditures Under Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstrations, Fiscal Years 2013, 2018, and 2023

Notes: Amounts include medical and administrative expenditures for demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act. The number of states with approved demonstrations was 42 in fiscal year 2013, 39 in fiscal year 2018, and 46 in fiscal year 2023. Data are as of April 2025. Because states generally have up to 2 years to adjust their reported expenditures, expenditures for fiscal year 2023 may be incomplete. For this analysis, adjustments for prior periods were applied to the year the expenditures occurred. Expenditures were also adjusted for inflation to 2023 dollars using the Gross Domestic Product Price Index.

CMS officials cited a number of factors that may have contributed to the trends in demonstration spending during this time period, when total Medicaid spending was also increasing. For example:

· States using demonstrations to cover the expansion population—low-income adults who became newly eligible for Medicaid beginning in 2014—likely contributed to increases in demonstration spending during this period. States receiving increased federal matching funds for that population further contributed to that effect.[21]

· Temporary increases in federal matching rates during the COVID-19 pandemic likely also contributed to the growth in federal spending for demonstrations. For example, the federal matching rate was temporarily increased by 6.2 percentage points beginning January 1, 2020.[22]

· Yearly fluctuations in demonstration spending, particularly in large states, could also have had substantial effects on expenditure trends and may have contributed to slower growth between 2018 and 2023. For example, when California removed Medicaid managed care from its demonstration in 2021, it resulted in a significant decrease in expenditures, according to CMS officials, which contributed to the slower growth in spending after this time.[23]

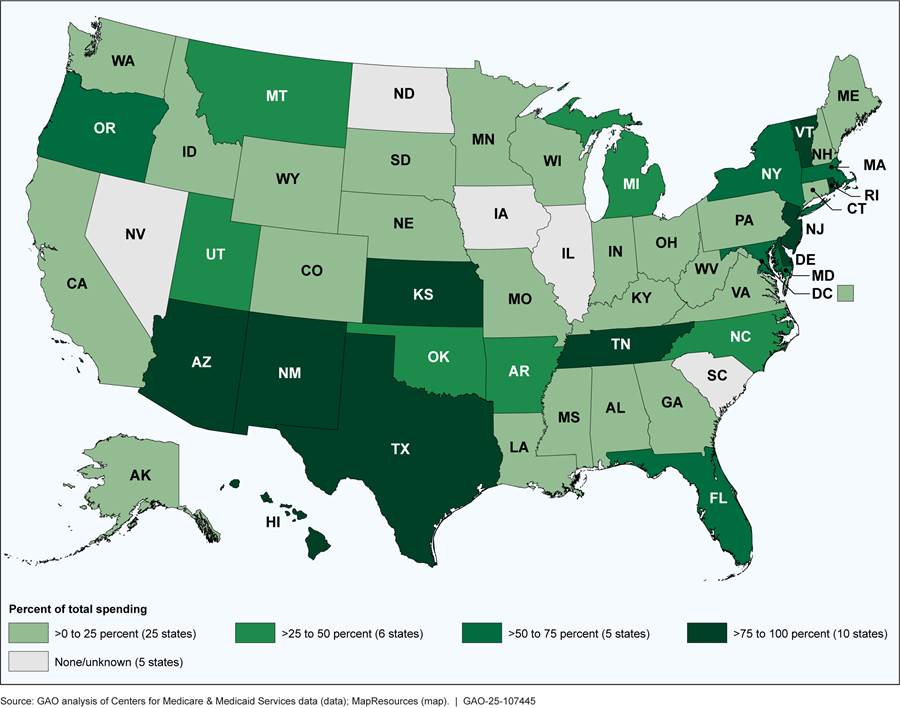

In fiscal year 2023, federal demonstration spending accounted for about one-third (33 percent) of total federal Medicaid spending, but this percentage varied widely across states.[24] In 10 states, demonstration spending accounted for over 75 percent of their total federal Medicaid spending; in five of these states, demonstration spending accounted for 90 percent or more of total federal Medicaid spending.[25] (See fig. 3.)

Figure 3: Federal Expenditures Under Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstrations as a Percentage of Total Federal Medicaid Expenditures, by State, Fiscal Year 2023

Notes: This analysis included data reported by states on medical spending and administrative costs for demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act and did not account for prior period adjustments. The none/unknown category includes one state (South Carolina) that did not have an ongoing Medicaid demonstration in fiscal year 2023 and four states that had ongoing demonstrations but, according to CMS officials, either had known difficulties reporting demonstration expenditures (Illinois and Nevada) or were not required to separately report demonstration expenditures (Iowa and North Dakota).

CMS’s Policy Changes Likely to Have Mixed Effects on Federal Spending and Do Not Always Ensure Budget Neutrality

The change CMS implemented beginning January 2021 to its policy for setting base year spending amounts significantly reduced demonstration spending limits and potential federal spending in our selected state demonstrations. However, the agency’s September 2022 adjustments to its base year and trend rate policies diminished the effects of the 2021 policy change and increased spending limits in selected state demonstrations. Further, CMS’s decision to allow new types of hypothetical costs in Medicaid demonstrations has inflated states’ demonstration spending limits. The changes in base year, trend rate, and hypothetical cost policies begun in September 2022 do not ensure that demonstrations are budget neutral.

CMS’s 2021 Policy Change Significantly Reduced Potential Federal Spending, but Subsequent Changes Diminished the Effect

CMS’s 2021 change to its policy for setting base year spending for demonstration extensions significantly reduced spending limits and potential federal spending in selected state demonstrations. However, subsequent changes beginning in September 2022 to the base year policy and in the policy around the trend rates used in setting spending limits resulted in increases in spending limits. These changes diminished the effects of the 2021 policy, increased potential federal spending, and do not ensure budget neutrality.

CMS’s 2021 and 2022 Base Year Policy Changes

|

Changes in Base Year Policy for Demonstration Extensions Over Time · Prior to January 2021. Base year spending could be estimated by continuing to trend forward a state’s historical spending projections. · January 2021 through August 2022. Base year spending was determined using a state’s recent, actual spending. · Since September 2022. Base year spending is determined using a weighted average of recent, actual spending (80 percent) and the state’s historical spending projections (20 percent). Source: GAO summary of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’s Information. | GAO‑25‑107445 |

We estimate that CMS’s 2021 requirement to calculate the base year using recent, actual spending data reduced spending limits in two selected states’ demonstrations (New York and Tennessee) by about $233 billion compared to what the spending limits would have been if based on the continued use of the states’ historical spending projections. These two demonstrations were approved before September 2022 and were subject to CMS’s 2021 base year policy. The estimated federal share of this decrease was about $123 billion. (See table 1.) For the third selected demonstration approved before September 2022 (Arkansas), we could not estimate the effect because the approval documents did not include the information to do so.[26]

Table 1: Estimated Effect on Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstration Spending Limits Under January 2021 Change in CMS’s Base Year Policy, Selected State Demonstrations

(dollars in billions)

|

State |

Estimated spending limit under pre-January 2021 policy |

Approved spending limit under January 2021 policy |

Decrease in approved spending limit under January 2021 policy |

Estimated federal share of decrease |

|

New York |

$529.5 |

$340.4 |

-$189.1 |

-$94.6 |

|

Tennessee |

$104.0 |

$60.5 |

-$43.5 |

-$27.9 |

|

Total |

$633.6 |

$401.0 |

-$232.6 |

-$122.5 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data. | GAO‑25‑107445

Notes: For demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act, beginning with demonstrations approved in January 2021, CMS policy required that base year spending for demonstration extensions be determined using a state’s recent, actual spending. Prior to this change, base year spending could be estimated by continuing to trend a state’s historical spending projections forward. Estimates were for the full budget neutrality period, which were as follows: April 2022 through March 2027 for New York, and January 2021 through December 2025 for Tennessee. The federal share of the decrease was estimated using states’ Federal Medical Assistance Percentages for fiscal year 2026, the most recent set of published rates at the time of the analysis.

The January 2021 base year policy change was consistent with our 2002 recommendation—which we elevated to a matter for congressional consideration in 2008—that CMS ensure valid methods are used when determining budget neutrality.[27]

In contrast, CMS’s subsequent 2022 adjustment to the base year policy—to use a weighted average of recent, actual spending experienced in the previous demonstration period (80 percent) and states’ historical spending projections (20 percent) when extending a demonstration—increased demonstration spending limits. It increased spending limits by about $28 billion in the three selected state demonstrations where CMS applied the adjusted policy. The estimated federal share of this increase was almost $17 billion. (See table 2.)

Table 2: Estimated Effect on Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstration Spending Limits Under September 2022 Change in CMS’s Base Year Policy, Selected State Demonstrations

(dollars in billions)

|

State |

Estimated spending limit under January 2021 policy |

Approved spending limit under September 2022 policy |

Increase in approved spending limit under September 2022 policy |

Estimated federal share of increase |

|

Arizona |

$112.8 |

$129.6 |

+$16.8 |

+$10.8 |

|

Massachusetts |

$71.1 |

$81.4 |

+$10.3 |

+$5.1 |

|

Washington |

$18.1 |

$19.3 |

+$1.2 |

+$0.6 |

|

Total |

$202.0 |

$230.3 |

+$28.4 |

+$16.6 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data. | GAO‑25‑107445

Notes: For demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act, beginning with demonstrations approved in September 2022, CMS policy required that base year spending for demonstration extensions be determined using a weighted average of recent, actual spending (80 percent) and the state’s historical spending projections (20 percent). Prior to that, CMS policy required base year spending to be entirely determined using a state’s recent, actual spending. Estimates were for the full budget neutrality period, which were as follows: October 2022 through September 2027 in Arizona, October 2022 through December 2027 in Massachusetts, and July 2023 through June 2028 in Washington. The federal share of the increase was estimated using states’ Federal Medical Assistance Percentages for fiscal year 2026, the most recent set of published rates at the time of the analysis.

CMS officials told us the agency made the 2022 change to its base year policy to address concerns raised among states that the 2021 policy change limited the states’ ability to test coverage of new services or populations. In interviews with selected states, officials from one state subject to the 2021 policy said that it did not affect the scope of the demonstration, whereas officials from another state indicated that the state scaled back their demonstration as a result of the 2021 policy.

However, moving away from estimates that are fully based on recent, actual spending diminishes the validity of those estimates and increases demonstration spending limits and potentially federal spending. Moreover, the change appears to conflict with concerns CMS raised in its 2018 guidance about using outdated data when calculating demonstration spending limits, and does not ensure that demonstrations are budget neutral.[28] Thus, it is inconsistent with our 2002 recommendation that CMS ensure that valid methods are used when determining budget neutrality.

CMS’s 2022 Trend Rate Policy Change

|

Changes in Trend Rate Policy Over Time · Prior to September 2022. Projected spending for each population was trended forward using the lesser of a state’s historical growth during the preceding demonstration period or the trend rate used in the President’s Budget proposal. · Since September 2022. Projected spending is trended forward using the trend rate in the President’s Budget proposal in all cases. Source: GAO summary of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’s information. | GAO‑25‑107445 |

The effect of CMS’s September 2022 policy change to trend base year spending forward using the President’s Budget trend rate in all cases—even when the rate is higher than the growth in spending actually experienced by the state—resulted in billions of dollars in increases to selected state demonstration spending limits and is likely to increase federal spending. Specifically, the policy change resulted in an additional $8.5 billion available under the spending limits for the three selected state demonstrations approved after the policy went into effect. The estimated federal share of the increase was about $4 billion. (See table 3.)

Table 3: Estimated Effect on Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstration Spending Limits Under September 2022 Change in CMS’s Trend Rate Policy, Selected State Demonstrations

(dollars in billions)

|

State |

Estimated spending limit under pre-September 2022 policy |

Approved spending limit under September 2022 policy |

Increase in approved spending limit under September 2022 policy |

Estimated federal share of increase |

|

Arizona |

$128.9 |

$129.6 |

+$0.7 |

+$0.4 |

|

Massachusetts |

$76.9 |

$81.4 |

+$4.5 |

+$2.3 |

|

Washington |

$16.0 |

$19.3 |

+$3.3 |

+$1.7 |

|

Total |

$221.8 |

$230.3 |

+$8.5 |

+$4.3 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data. | GAO‑25‑107445

Notes: For demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act, beginning with demonstrations approved in September 2022, CMS policy required that base year spending be trended forward using the same rates as used in the President’s Budget. Prior to this change, base year spending was trended using the lesser of the President’s Budget trend rates or the growth rates actually experienced by the state during the previous demonstration period. Estimates were for the full budget neutrality period, which were as follows: October 2022 through September 2027 in Arizona, October 2022 through December 2027 in Massachusetts, and July 2023 through June 2028 in Washington. The federal share of the increase was estimated using states’ Federal Medical Assistance Percentages for fiscal year 2026, the most recent set of published rates at the time of the analysis.

In all three selected demonstrations approved since CMS changed its trend rate policy, the President’s Budget trend rate was higher than historical spending growth for one or more of the populations in the demonstration. For example, in Massachusetts’s demonstration, the historical spending growth for the largest population group was less than 1 percent, but CMS applied the President’s Budget trend rate of 4.8 percent. This difference accounted for a $3.4 billion increase in the demonstration spending limit; the estimated federal share of which is $1.7 billion.

Though approved prior to September 2022, CMS similarly applied the President’s Budget trend rate in all cases to another selected state demonstration—Tennessee’s—despite the state experiencing a lower level of growth during the state’s previous demonstration for all but one covered population.[29] This exception to the policy to use the lower rate increased Tennessee’s spending limit by $1.7 billion ($1.1 billion estimated federal share). Tennessee officials we spoke with explained that they asked CMS for an exception to the official policy at the time, which CMS granted. CMS officials confirmed granting the exception, and did not cite a rationale other than the state having requested it. The exception was not noted in the demonstration approval letter.

CMS’s change to its trend rate policy would have had a similar effect in another selected state demonstration approved prior to the policy change. New York’s demonstration was approved prior to September 2022, and having not received an exception, was subject to the previous policy of trending base year spending using the lesser of the state’s historical spending growth during the preceding demonstration years or the trend rates used in the President’s Budget proposal. Applying the President’s Budget trend rate in all cases would have increased New York’s 5-year spending limit by about $7.8 billion ($3.9 billion estimated federal share).

In the agency’s 2024 guidance, CMS indicated that the rationale for the change in trend rate policy was to align its approach to budget neutrality with federal budgeting principles.[30] According to CMS officials, requiring demonstration spending estimates to be trended using the same rates as the President’s Budget ensures that the estimates are based on the same assumptions about future medical care costs and program demographics. However, it is unclear why the change was needed other than to provide more flexibility to states. CMS’s September 2022 change to its trend rate policy adds billions in potential federal spending and does not ensure that demonstrations are budget neutral to the federal government. As with the 2022 change to the base year policy, the trend rate policy is inconsistent with our prior recommendation that CMS ensure valid methods are used when determining budget neutrality.

CMS Policy Changes on Hypothetical Costs Have Inflated Spending Limits and Potential Federal Spending

CMS’s policy changes beginning in September 2022 to treat certain costs for HRSN services and pre-release services for incarcerated individuals as hypothetical increased demonstration spending limits by billions compared with what the limits would have been had these costs not been treated as hypothetical.[31] Including these costs in the spending limit, rather than requiring states to offset the costs with savings elsewhere in the demonstration, results in the potential for federal Medicaid spending to be higher than it would have been absent the demonstration. This is inconsistent with CMS’s policy that demonstrations be budget neutral to the federal government.

Health-Related Social Needs

|

What Are Health-Related Social Needs Services? · Services addressing health-related social needs, include: housing supports, such as assistance finding and securing housing and moving costs; · nutrition supports, such as nutrition counseling and home-delivered meals; and · case management, such as linking individuals to other state and federal programs. Source: GAO summary of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’s information. | GAO‑25‑107445 |

Treating certain costs to address HRSN as hypothetical increased spending limits by a total of almost $7.5 billion, in the five selected state demonstrations that had such services approved. We estimated the federal share of that to be about $3.8 billion. (See table 4.)

Table 4: Increase in Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstration Spending Limits Due to Treating Health-Related Social Needs Costs as Hypothetical, Selected State Demonstrations

(dollars in millions)

|

State |

Increase in spending limit |

Estimated federal share of increase |

|

Arizona |

$549 |

$353 |

|

Arkansas |

$95 |

$66 |

|

Massachusetts |

$1,369 |

$684 |

|

New York |

$3,673 |

$1,837 |

|

Washington |

$1,802 |

$901 |

|

Total |

$7,488 |

$3,841 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data. | GAO‑25‑107445

Notes: Analysis shows, for selected state demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act, the amounts that spending limits increased due to CMS treating expenditures for health-related social needs (HRSN) as hypothetical costs. Increases reflect estimated expenditures for both HRSN services and HRSN infrastructure. Estimates were for the full budget neutrality period, which were as follows: October 2022 through September 2027 in Arizona; January 2022 through December 2026 in Arkansas; October 2022 through December 2027 in Massachusetts; April 2022 through March 2027 in New York; and July 2023 through June 2028 in Washington. The federal share of the increase was estimated using states’ Federal Medical Assistance Percentages for fiscal year 2026, the most recent set of published rates at the time of the analysis.

CMS’s treatment of certain HRSN costs as hypothetical is a departure from CMS’s previous practices. Historically, CMS has treated costs as hypothetical when assessing budget neutrality only if those costs could have otherwise been covered, absent the demonstration, under existing Medicaid authorities.[32] Costs that could not otherwise be covered under other Medicaid authorities were not treated as hypothetical. Instead, CMS only allowed them to be included in the demonstration if the state identified offsetting savings elsewhere within the demonstration to ensure the demonstration remained budget neutral. For example, the state would need to spend sufficiently less under the demonstration than it would have without the demonstration to offset the additional spending for costs that were not otherwise eligible for federal matching funds. This was CMS’s policy as recently as 2021.[33]

In our selected state demonstrations, CMS approved costs that it treated as hypothetical for a range of HRSN services, some of which appear not to be covered under existing Medicaid authorities.

· Rent or temporary housing for up to 6 months. CMS approved, and treated as hypothetical, the costs of covering up to 6 months of rent or temporary housing for eligible individuals in the demonstrations we reviewed in Arizona, Massachusetts, New York, and Washington.[34] In three of these demonstrations, approved coverage also included utility costs, including activation expenses and back payments to secure utilities for individuals receiving rent or temporary housing. According to CMS guidance, federal matching funds are generally not available to state Medicaid programs for room costs, which CMS defines to include all property-related costs, including rental costs and utilities.[35]

· Up to three meals per day delivered to the home or private residence for up to 6 months. CMS approved, and treated as hypothetical, these costs in the demonstrations we reviewed from Massachusetts, New York, and Washington.[36] While some Medicaid authorities provide coverage for certain populations for up to two meals a day, federal matching funds are generally not available for board, which CMS defines as three meals a day.[37]

· One-time transition costs, such as first month’s rent. CMS approved, and treated as hypothetical, one-time transition costs in the demonstrations we reviewed in Arkansas, Massachusetts, New York, and Washington. Such costs may be allowable under certain existing Medicaid authorities for specific populations–typically Medicaid enrollees transitioning from institutional to community-based settings.[38] However, the populations approved to receive these services in the selected demonstrations are broader. For example, populations eligible for one-time transition costs in Arkansas’s demonstration include individuals with high-risk pregnancies, serious mental illness or substance use disorder living in rural areas, and young adults most at risk of long-term poverty. In Washington’s demonstration, these services were approved for individuals who are homeless or at risk of homelessness, youth transitioning out of the child welfare system, and individuals transitioning out of institutional care or congregate settings.

CMS’s current budget neutrality policy acknowledges that some HRSN costs could not otherwise be covered under Medicaid absent the demonstration. CMS’s rationale for treating these costs as hypothetical, despite not meeting the agency’s previous criteria, is that there are insufficient or inconsistent data to calculate the cost of providing these services absent the demonstration.[39] CMS guidance also states that treating HRSN costs as hypothetical gives states more flexibility to test these interventions, which the agency anticipates could reduce future Medicaid program costs.[40] Noting the potential negative fiscal impact that treating HRSN spending as hypothetical costs could have on Medicaid, CMS set a limit for states’ HRSN costs at 3 percent of a state’s total Medicaid spending.

Beyond the selected demonstrations we reviewed, as of March 2025, CMS had approved demonstrations covering HRSN, and treated these as hypothetical costs, in 13 additional states. Including these costs increased demonstration spending limits by over $16 billion across these demonstrations, with the federal share being at least $8 billion.[41] (See app. III for a list of state demonstrations approved to cover HRSN services.)

It is unclear how many additional states will apply and be approved to provide HRSN services under demonstrations; in March 2025, CMS announced that the agency was rescinding two prior policy documents that discussed opportunities for states to cover services and supports to address HRSN under various state Medicaid programs, including demonstrations. The agency indicated that its plan going forward was to consider states’ applications to cover HRSN services and supports on a case-by-case basis to determine whether they satisfy federal requirements for approval under applicable provisions of the Social Security Act and implementing regulations.[42] As of May 2025, CMS officials said the agency had not issued any changes to its guidance regarding how costs for HRSN services will be treated for budget neutrality purposes. However, continuing to include these as hypothetical costs when calculating demonstration spending limits, rather than requiring states to offset the costs with savings elsewhere in the demonstration, does not ensure budget neutrality.[43]

Pre-Release Services for Incarcerated Individuals

CMS’s decision to approve, and treat as hypothetical, costs for pre-release services for incarcerated individuals also increased demonstration spending limits. At the time of our analysis, two of our selected state demonstrations (Massachusetts and Washington) included approval to provide such services, including medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders, physical and behavioral health consultations, lab and radiology services, and a 30-day supply of prescription and over-the-counter medications provided upon release.[44] Treating these as hypothetical costs increased spending limits for these demonstrations by about $814 million, or an estimated $407 million in federal spending. According to CMS officials, as of March 2025, the agency approved demonstrations in 17 additional states to provide pre-release services for soon-to-be-former inmates of public institutions.[45]

As with HRSN services, pre-release services do not appear to be coverable under other Medicaid authorities. Federal law generally excludes coverage of services to Medicaid enrollees while they are inmates of a public institution (sometimes referred to as the inmate payment exclusion).[46] In 2023, CMS issued guidance to states on opportunities to design demonstrations to cover pre-release services as directed by the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act.[47] However, neither the guidance nor the act addressed treating these costs as hypothetical for budget neutrality purposes. CMS’s rationale for treating these costs as hypothetical, despite them not meeting the agency’s previous criteria, is that the costs would have been otherwise allowable under Medicaid were it not for Medicaid’s inmate payment exclusion. Previously, CMS required that proposed costs for services or populations not otherwise eligible for federal Medicaid funds (e.g., the costs for pre-release services for incarcerated individuals) be offset with demonstration savings for a demonstration to be considered budget neutral. If CMS continues to treat the costs of pre-release services as hypothetical, it cannot ensure that demonstrations are budget neutral.

Conclusions

Section 1115 demonstrations provide a vehicle for states to test new approaches in their Medicaid programs. CMS’s longstanding policy that demonstrations be budget neutral to the federal government should serve as a fiscal control to balance the flexibility granted to states. However, we have raised concerns over the past three decades about the weaknesses in CMS’s efforts to ensure that all demonstrations are budget neutral. In just the last decade, federal spending for demonstrations has nearly doubled and now represents about a third of total federal Medicaid spending.

The policy changes CMS announced in 2016—including the 2021 requirement to use recent, actual spending data when setting the demonstration base year—was a step forward in better ensuring that demonstrations are budget neutral. In contrast, the more recent 2022 policy changes related to demonstration base years and trend rates have partially undone that progress. Those changes are likely to increase federal spending by billions of dollars compared to previous policy and call into question the agency’s commitment to limiting federal fiscal exposure resulting from states’ use of demonstrations. Because of the risks these changes present and the uncertainty around how the new statutory requirements—not effective until 2027— will affect CMS’s policies, we reiterate the need for CMS to fully implement our 2002 recommendation to use valid methods when determining budget neutrality.

Potentially more concerning than the 2022 changes to its base year and trend rate policies is CMS’s expansion of the types of costs it treats as hypothetical to those not otherwise coverable under Medicaid, which by definition could not have been made absent the demonstration. By treating HRSN services—for example, up to 6 months of rental assistance—and pre-release services for incarcerated individuals as hypothetical costs without requiring offsetting savings, CMS has rendered the assessment of budget neutrality a hollow exercise. Without changes, this erosion of fiscal guardrails will continue to allow for increased federal spending under demonstrations.

Recommendation for Executive Action

The Administrator of CMS should revise the agency’s section 1115 budget neutrality policy to stop treating costs for populations or services that could not have otherwise been covered under existing Medicaid authorities as hypothetical when setting demonstration spending limits. Instead, CMS should require the costs of those populations or services to be offset by other reductions in demonstration spending.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS for review and comment. In its comments, reproduced in appendix IV, HHS stated that it will consider GAO’s recommendation as implements the new requirement prohibiting the agency, effective January 1, 2027, from approving a demonstration unless the CMS chief actuary certifies that it is expected to be budget neutral.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at RosenbergM@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix V.

Michelle B. Rosenberg

Director, Health Care

List of Requesters

The Honorable Brett Guthrie

Chairman

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable H. Morgan Griffith

Chairman

Subcommittee on Health

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable John Joyce, M.D.

Chairman

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Earl L. “Buddy” Carter

House of Representatives

The Honorable Gary Palmer

House of Representatives

|

Arizona |

Demonstration name: Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System Approval date: Oct. 14, 2022 Effective dates: Oct. 14, 2022, through Sept. 30, 2027 Total estimated spending limit: $129,586,654,062 |

|

Arkansas |

Demonstration name: Arkansas Health and Opportunity for Me Approval date: Dec. 21, 2021 Effective dates: Jan. 1, 2022, through Dec. 31, 2026 Total estimated spending limit: $11,597,875,194 |

|

Massachusetts |

Demonstration name: MassHealth Approval date: Sept. 28, 2022 Effective dates: Oct. 1, 2022, through Dec. 31, 2027 Total estimated spending limit: $81,406,541,243 |

|

New York |

Demonstration name: Medicaid Redesign Team Approval date: Mar. 23, 2022 Effective dates: Apr. 1, 2022, through Mar. 31, 2027 Total estimated spending limit: $340,412,221,623 |

|

Tennesseea |

Demonstration name: TennCare III Approval date: Jan. 8, 2021 Effective dates: Jan. 8, 2021, through Dec. 31, 2030 Total estimated spending limit: $60,537,893,884 |

|

Washington |

Demonstration name: Medicaid Transformation Project 2.0 Approval date: June 30, 2023 Effective dates: July 1, 2023, through June 30, 2028 Total estimated spending limit: $19,340,604,177 |

Source: GAO summary of documents from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) | GAO‑25‑107445

Note: Demonstrations were conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act.

aTennessee received approval for a 10-year demonstration; however, the terms of the demonstration require that CMS reassess the state’s budget neutrality agreement at the end of year five (Dec. 31, 2025).

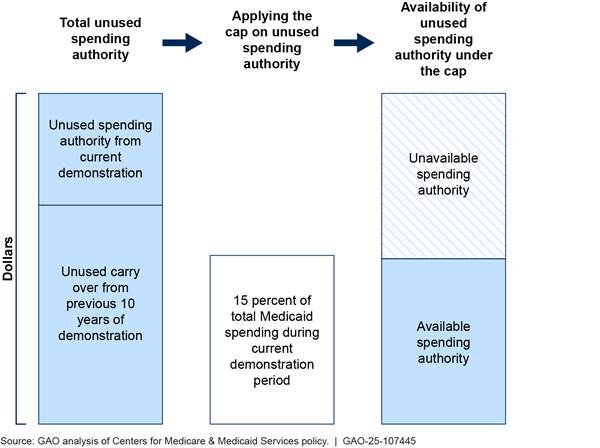

Appendix II: Information on CMS’s September 2022 Policy on the Availability of Unused Demonstration Spending Authority

In September 2022, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) changed its policies for ensuring that Medicaid section 1115 demonstrations are budget neutral to the federal government. Unused demonstration spending authority may result when a state spends less than its demonstration spending limit. One of the policy changes CMS made was to increase the time period of unused spending authority that states can carry over from one demonstration period to another. Specifically, CMS began allowing states to carry over unused spending authority from the previous 10 years, rather than the previous 5 years as had been its policy since 2016. However, CMS also placed a cap, or overall limit, on the amount of unused spending authority states may use. Specifically, the total unused spending authority a state may access in its current demonstration, which includes any unused spending authority carried over from prior demonstration periods, may not exceed 15 percent of the state’s projected total Medicaid expenditures for the demonstration period. Additionally, under CMS’s September 2022 policy, states are required to use their unused spending authority in the order it was accrued. Figure 4 illustrates the comparison CMS makes between the total unused spending authority potentially available and the new 15 percent cap.

Figure 4: Illustration of CMS’s September 2022 Policy on the Availability of Unused Section 1115 Demonstration Spending Authority

Notes: For demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act, beginning with demonstrations approved in September 2022, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) policy allowed states to carry over up to 10 years of unused spending authority from one demonstration period to the next, subject to a cap equal to 15 percent of a state’s Medicaid spending. (Since 2016, CMS policy had been to allow five such years of “carry over.”) Total unused demonstration spending is defined as the sum of any unused demonstration spending authority from a state’s current demonstration plus any carry over from the previous 10 years. The 15 percent cap is based on CMS estimate of a state’s total Medicaid expenditures during the demonstration period, including for expenditures outside of the demonstration. The lesser of these two amounts represents the unused spending authority available under the current demonstration.

In August 2024, CMS formalized its September 2022 policy changes in a State Medicaid Director Letter.[48] The letter included an additional policy change that interacts with CMS’s policy on demonstration carry over. Specifically, the letter indicated that any unused spending authority above the 15 percent cap is not immediately forfeited; rather, it may be deferred to the subsequent demonstration period or transferred to another one of the state’s demonstrations (if the state has more than one).[49]

The revised carry over policy and 15 percent cap were applicable to three of the selected state demonstrations we reviewed. The cap significantly reduced the amount of unused spending authority two states could use in their current demonstration periods (Arizona and Massachusetts) and had no effect on the third demonstration (Washington). However, the net effect of the changes on federal spending for demonstrations in Arizona and Massachusetts will depend on whether those states seek to leverage any unused spending authority above the cap in future demonstration periods or for other demonstrations. The amounts of unused spending authority above the cap totaled $38.6 billion for the Arizona demonstration and $27.0 billion for the Massachusetts demonstration. (See table 6.)

Table 6: Estimated Effect of CMS’s September 2022 Policy on the Availability of Unused Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstration Spending Authority, Selected State Demonstrations

(dollars in billions)

|

|

Unused spending authority |

Medicaid cap |

Availability of unused spending authority under current demonstration |

|||

|

State |

Carry over from previous 10 years |

Unused spending authority from current demonstration period |

Total unused demonstration spending authority potentially available |

15 percent of total Medicaid spending during current demonstration period |

Available under the 15% cap |

Unavailable due to the 15% cap |

|

Arizona |

$42.1 |

$12.8 |

$55.0 |

$16.4 |

$16.4 |

$38.6 |

|

Massachusetts |

$28.2 |

$17.6 |

$45.7 |

$18.7 |

$18.7 |

$27.0 |

|

Washington |

$1.1 |

$1.2 |

$2.2 |

$15.1 |

$2.2 |

$0 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data. | GAO‑25‑107445

Notes: For demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act, beginning with demonstrations approved in September 2022, CMS policy allowed states to carry over up to 10 years of unused spending authority from one demonstration period to the next, subject to a cap equal to 15 percent of a state’s Medicaid spending. (Since 2016, CMS policy had been to allow five such years of “carry over.”) Total unused demonstration spending is defined as the sum of any unused demonstration spending authority from a state’s current demonstration plus any carry over from the previous 10 years. The 15 percent cap is based on CMS estimate of a state’s total Medicaid expenditures during the demonstration period, including for expenditures outside of the demonstration. The lesser of these two amounts represents the unused spending authority available under the current demonstration. Estimates were for the full budget neutrality period, which were as follows: October 2022 through September 2027 in Arizona, October 2022 through December 2027 in Massachusetts, and July 2023 through June 2028 in Washington.

Appendix III: Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstrations with Services to Address Health-Related Social Needs

As of March 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) had approved 18 states to cover services addressing beneficiaries’ health-related social needs (HRSN) through 19 Medicaid section 1115 demonstrations. (See table 7.) According to CMS, HRSN are social and economic needs that individuals experience that affect their ability to maintain their health and well-being.[50] CMS has approved states to provide a range of HRSN services under Medicaid demonstrations, such as various housing and nutrition supports. In each demonstration, HRSN costs were added as hypothetical costs to states’ demonstration spending limits for the purposes of determining budget neutrality.

Table 7: Spending Limits for Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) in Medicaid Section 1115 Demonstrations, Approved as of March 2025

|

State |

Demonstration name |

Approval date for HRSNa |

Total HRSN spending limitb |

Sublimit for HRSN infrastructureb,c |

|

Arizona |

Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System |

Oct. 14, 2022 |

$549,250,000 |

$67,500,000 |

|

Arkansas |

Arkansas Health and Opportunity for Me |

Nov. 1, 2022 |

$95,270,000 |

$10,470,000 |

|

California |

Behavioral Health Community-Based Organized Networks of Equitable Care and Treatment |

Dec. 16, 2024 |

$2,469,168,000 |

— |

|

California |

California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal |

Jan. 26, 2023 |

$1,964,340,279 |

— |

|

Colorado |

Expanding the Substance Use Disorder Continuum of Care |

Jan. 13, 2025 |

$46,883,739 |

$6,915,303 |

|

Hawaii |

Hawaii QUEST Integration |

Jan. 8, 2025 |

$512,600,000 |

$76,890,000 |

|

Illinois |

Illinois Healthcare Transformation |

July 2, 2024 |

$5,275,000,000 |

$765,000,000 |

|

Kentucky |

TEAMKY |

Dec. 12, 2024 |

$51,265,877 |

$2,738,300 |

|

Massachusetts |

MassHealth |

Apr. 19, 2024 |

$1,368,618,484 |

$25,000,000 |

|

New Jersey |

New Jersey FamilyCare Comprehensive Demonstration |

Mar. 30, 2023 |

$826,960,123 |

$78,750,000 |

|

New Mexico |

Turquoise Care |

July 25, 2024 |

$904,311,142 |

$99,474,270 |

|

New York |

Medicaid Redesign Team |

Jan. 9, 2024 |

$3,673,261,334 |

$500,000,000 |

|

North Carolina |

North Carolina Medicaid Reform Demonstration |

Dec. 10, 2024 |

$2,299,250,000 |

$299,250,000 |

|

Oregon |

Oregon Health Plan |

Sept. 28, 2022 |

$1,023,000,000 |

$119,000,000 |

|

Pennsylvania |

Keystones of Health |

Dec. 26, 2024 |

$607,920,000 |

$91,000,000 |

|

Utah |

Utah Medicaid Reform 1115 Demonstration |

Jan. 8, 2025 |

$221,514,714 |

$33,200,000 |

|

Vermont |

Global Commitment through Health |

Jan. 2, 2025 |

$83,823,144 |

$10,933,454 |

|

Washington |

Medicaid Transformation Project 2.0 |

June 30, 2023 |

$1,801,899,136 |

$270,000,000 |

|

West Virginia |

Evolving West Virginia Medicaid’s Behavioral Health Continuum of Care |

Dec. 11, 2024 |

$68,205,387 |

— |

|

Total |

|

|

$23,842,541,359 |

$2,456,121,327 |

Source: GAO analysis of Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) approval documents. | GAO‑25‑107445

Note: Amounts reflect total computable costs (federal and non-federal share) for demonstrations conducted under section 1115 of the Social Security Act.

aSome states received CMS approval for HRSN through an amendment to the special terms and conditions for their demonstration. In such cases, the HRSN approval date may differ from the demonstration approval date.

bDemonstration approvals set HRSN spending limits for each year of the demonstration period; the amounts shown reflect the sum of these limits for the entire demonstration period.

cAmounts reflect approved spending limits for HRSN infrastructure, which is a subset of the total HRSN spending limit. Under current CMS policy, any unspent expenditure authority for HRSN infrastructure can be applied to HRSN services in the same demonstration year. The federal government pays for 90 percent of infrastructure costs that are for the design, development, or installation of systems used for eligibility determination and enrollment, and 75 percent of the maintenance and operation of such systems; otherwise, the federal share is generally 50 percent. In some cases, HRSN infrastructure costs were not specified in the demonstration’s special terms and conditions; these are indicated with —.

GAO Contact

Michelle B. Rosenberg at RosenbergM@gao.gov

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, key contributors to this report were Susan Barnidge (Assistant Director), Perry Parsons (Analyst-in-Charge), Fritz Manzano, and Linda McIver. Also contributing were Julie Flowers, Drew Long, Jennifer Rudisill, and Roxanna Sun.

Medicaid Demonstrations: Approvals of Major Changes Need Increased Transparency. GAO‑19‑315. Washington, D.C.: April 17, 2019.

Medicaid Demonstrations: Federal Action Needed to Improve Oversight of Spending. GAO‑17‑312. Washington, D.C.: April 3, 2017.

Medicaid Demonstrations: Approval Criteria and Documentation Need to Show How Spending Furthers Medicaid Objectives. GAO‑15‑239. Washington, D.C.: April 13, 2015.

Medicaid Demonstrations: HHS’s Approval Process for Arkansas’s Medicaid Expansion Waiver Raises Cost Concerns. GAO‑14‑689R. Washington, D.C.: August 8, 2014.

Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: Approval Process Raises Cost Concerns and Lacks Transparency. GAO‑13‑384. Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2013.

Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: Recent HHS Approvals Continue to Raise Cost and Oversight Concerns. GAO‑08‑87. Washington, D.C.: January 31, 2008.

Medicaid and SCHIP: Recent HHS Approvals of Demonstration Waiver Projects Raise Concerns. GAO‑02‑817. Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2002.

Medicaid Section 1115 Waivers: Flexible Approach to Approving Demonstrations Could Increase Federal Costs. GAO/HEHS‑96‑44. Washington, D.C.: November 8, 1995.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard, Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

Connect with GAO

Connect with GAO on X,

LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our Email Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

To Report Fraud, Waste, and Abuse in Federal Programs

Contact FraudNet:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/about/what-gao-does/fraudnet

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454

Media Relations

Sarah Kaczmarek, Managing Director, Media@gao.gov

Congressional Relations

A. Nicole Clowers, Managing Director, CongRel@gao.gov

General Inquiries

[1]Medicaid is a joint, federal-state program that finances health care coverage for low-income and medically needy individuals. Medicaid spending totaled $871.7 billion in 2023, according to estimates from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’s Office of the Actuary.

[2]Legislation enacted on July 4, 2025, commonly known as the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, prohibits the approval of a demonstration, effective January 1, 2027, unless CMS’s chief actuary certifies that the demonstration is budget neutral. An Act To provide for reconciliation pursuant to title II of H. Con. Res. 14, Pub. L. No. 119-21, § 71118, 139 Stat. 72, 306 (2025) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 1315(g)) (hereafter OBBBA).

[3]See GAO, Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: Approval Process Raises Cost Concerns and Lacks Transparency, GAO‑13‑384 (Washington, D.C.: June 25, 2013).

[4]See GAO, Medicaid Demonstrations: Approvals of Major Changes Need Increased Transparency, GAO‑19‑315 (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 17, 2019).

[5]See CMS, RE: Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects, SMD #18-009 (Baltimore, Md: Aug. 22, 2018) and CMS, RE: Budget Neutrality for Section 1115(a) Medicaid Demonstration Projects, SMD #24-003 (Baltimore, Md: Aug. 22, 2024).

[6]The Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System is a web-based application that state Medicaid agencies use to enter and report both states’ budgeted expenditures and the actual quarterly expenditures that occur. States upload the information using electronic forms, such as the CMS-64 for quarterly expenditures. CMS uses these data to compute the amount of federal matching funds the agency will provide to the state for program operations.

[7]We adjusted the data in two ways. First, when reporting on Medicaid demonstration spending, we accounted for prior period adjustments submitted by states. These are adjustments that states report in subsequent quarters to adjust their reported expenditures for any underreporting, overreporting, or miscategorized spending in prior periods, including prior years. Second, because the data span a significant period of time, we converted all amounts to fiscal year 2023 dollars, the last year in our analysis, using the Gross Domestic Product Price Index. Our analysis included both medical assistance and administrative expenditures.

[8]For the purposes of this report, we refer to the District of Columbia as a state.

[9]The federal government matches most state Medicaid spending according to the state’s Federal Medical Assistance Percentage. This percentage is calculated using a statutory formula based on the state’s per capita income in relation to the national per capita income. To estimate the federal share of spending, we applied the standard federal matching rate for each state to the reported total Medicaid spending (i.e., federal and nonfederal share combined). Our selected demonstrations generally spanned 5 years, with varying start and end dates, ranging from 2021 to 2030. To simplify our analysis, we applied the matching rate from a single year (fiscal year 2026), although these rates may change slightly from year to year. We chose fiscal year 2026 because it was the most recently published set of rates at the time of our analysis and because it is included within the approval period of each of the six selected states. Among our selected states, the federal matching rate in fiscal year 2026 ranges from 50 to 69 percent.

[10]According to CMS officials, CMS’s policy as of May 2025 is that demonstration approval periods may not exceed 5 years. The agency has made exceptions in the past and approved demonstrations for up to 10 years. For example, in January 2021, CMS approved Tennessee’s demonstration for a 10-year period.

[11]As mentioned previously, legislation enacted on July 4, 2025, prohibits the approval of a demonstration unless CMS’s chief actuary certifies that it will be budget neutral to the federal government. That provision is effective January 1, 2027. See OBBBA § 71118.

[12]The spending limit may also include any aggregate amounts set under the demonstration for spending that is not based on enrollment.

[13]For example, we found that when approving a state demonstration that expanded coverage for adults by paying premiums for private insurance, CMS set a spending limit that was based, in part, on hypothetical costs. Specifically, CMS included costs for significantly higher payment amounts to providers than what the state would have paid if the state expanded coverage under the traditional Medicaid program. See GAO, Medicaid Demonstrations: HHS’s Approval Process for Arkansas’s Medicaid Expansion Waiver Raises Cost Concerns, GAO‑14‑689R (Washington, D.C.: Aug. 8, 2014).

[14]The requirement beginning in January 2021 to use recent cost data to determine the base year was initially announced to state Medicaid programs in May 2016. It was then formalized in a 2018 guidance letter to state Medicaid directors. See CMS, SMD #18-009.

[15]The President’s Budget trend rates are provided by CMS’s Office of the Actuary annually and are based on the expected expenditures by year for each Medicaid expenditure group, such as low-income children, people with disabilities, and people aged 65 and older.

[16]According to CMS, HRSN are social and economic needs that individuals experience that affect their ability to maintain their health and well-being. They put individuals at risk for worse health outcomes and increased health care use. HRSN refers to individual-level factors such as financial instability, lack of access to healthy food, lack of access to affordable and stable housing and utilities, lack of access to health care, and lack of access to transportation. See: https:// www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/key-concepts/social-drivers-health-and-health-related-social-needs, accessed May 9, 2025.

[17]See CMS, SMD #24-003.

[18]CMS officials indicated that as of March 2025, two states (Minnesota and New Hampshire) have avoided corrective action plans for exceeding spending limits, in part, because of the new mid-course correction policy.

[19]See OBBBA § 71118.

[20]States may submit adjustments to their prior reported Medicaid expenditures. For this analysis, adjustments for prior periods were applied to the year those expenditures occurred. Expenditures were also adjusted for inflation to 2023 dollars, using the Gross Domestic Product Price Index. Data for fiscal year 2023 may be incomplete, as states generally have up to 2 years to adjust their reported expenditures and these data are as of April 2025.

[21]In states that chose to expand their Medicaid programs as authorized by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the federal government provided a federal matching rate of 100 percent beginning in 2014 to cover spending for the newly eligible adult population. This increased federal matching rate for the newly eligible population gradually diminished to 90 percent in 2020. See 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(y).

[22]The Families First Coronavirus Response Act temporarily increased the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage by 6.2 percentage points for eligible states in response to the COVID-19 public health emergency, beginning January 1, 2020, and ending December 31, 2023. See Pub. L. No. 116-127, 134 Stat. 178 (2020), as amended by Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, Pub. L. No. 117-328, 136 Stat. 4459 (2022).

[23]Under a managed care delivery model, states contract with managed care plans to provide a specific set of covered services in return for a fixed periodic payment per enrollee—typically per member per month. Managed care is the predominant method for delivering services in Medicaid.

[24]This analysis is based on the expenditures states reported in fiscal year 2023. Since states may submit adjustments to prior reported expenditures, the analysis may include expenditures reported in fiscal year 2023 that were for prior years and does not include expenditures for fiscal year 2023 reported in later years.

[25]The five states whose reported demonstration expenditures accounted for 90 percent or more of their federal Medicaid expenditures were Arizona (99 percent), Kansas (96 percent), New Jersey (90 percent), Rhode Island (91 percent), and Vermont (96 percent).

[26]Arkansas’s demonstration uses a premium assistance model to purchase coverage through qualified health plans at the market rates charged by insurers.

[27]See GAO, Medicaid and SCHIP: Recent HHS Approvals of Demonstration Waiver Projects Raise Concerns, GAO‑02‑817 (Washington, D.C.: July 12, 2002) and Medicaid Demonstration Waivers: Recent HHS Approvals Continue to Raise Cost and Oversight Concerns, GAO‑08‑87 (Washington, D.C.: Jan. 31, 2008). Because our 2002 recommendation had not been addressed, we asked Congress in 2008 to consider requiring increased fiscal responsibility in the approval of Medicaid demonstrations. As indicated above, CMS, in 2021, revised its policy to improve its methods for setting spending limits for determining budget neutrality. Furthermore, as noted previously, Congress recently passed and the President signed legislation that, effective January 1, 2027, prohibits the approval of a demonstration unless CMS’s chief actuary certifies that it will be budget neutral to the federal government. See OBBBA § 71118. While the legislation addresses our matter for congressional consideration, the recommendation to CMS has not been fully implemented because the agency has not addressed other concerns with the methods used when determining budget neutrality. We will monitor CMS’s implementation of the new legislation to see if that addresses the outstanding concerns.

[28]In its 2018 guidance, CMS noted that states’ demonstration spending limits “came to be based on antiquated historical data after multiple extensions, with little grounding in the state’s current health care environment and associated expenditures.” See CMS, SMD #18-009, 7.

[29]Tennessee’s demonstration was approved January 8, 2021.

[30]See CMS, SMD #24-003, 6.

[31]See CMS, SMD #24-003. In addition to expenditures for certain HRSN and pre-release services, CMS has treated other costs as hypothetical that appear not to be otherwise coverable under Medicaid authorities. For example, in two of our selected state demonstrations (Massachusetts and Washington) CMS approved, and treated as hypothetical, costs for services provided in institutions for mental diseases, including for the treatment of patients with serious mental illness. This increased spending limits in those demonstrations by over $650 million. These expenditures were treated as hypothetical even though states likely could not have provided these services absent the demonstration because Medicaid generally excludes coverage of services to residents of institutions for mental diseases—which are certain facilities larger than 16 beds that primarily provide diagnosis, treatment, or other services to persons with behavioral health conditions. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396d(a)(B), (i). Exceptions include services provided to inpatients age 65 and older and a state option to cover up to 30 days of services for adults with at least one substance use disorder at an eligible institution. See 42 U.S.C. §§ 1396d(a)(14), 1396n(l).