HEALTH CARE CONSOLIDATION

Published Estimates of the Extent and Effects of Physician Consolidation

Report to Congressional Committees

United States Government Accountability Office

For more information, contact Leslie V. Gordon at GordonLV@gao.gov.

Highlights of GAO-25-107450, a report to congressional committees

Published Estimates of the Extent and Effects of Physician Consolidation

Why GAO Did This Study

In recent years, the health care sector in the United States has become increasingly consolidated. This has given rise to concerns that consolidation may result in decreased competition and increased costs to patients, employers, health insurers, and federal health care programs. Physician consolidation occurs when practices merge together or are acquired by or affiliate with other entities.

House Report 117-403 includes a provision for GAO to study the extent health care consolidation is taking place across Medicare and Medicaid markets, and how private equity could be contributing. This report describes what available research indicates about (1) the extent of physician consolidation, including practice ownership by hospital systems, corporate entities, or private equity firms; and (2) the effects of these types of physician consolidation on health care spending and prices, quality of care, and access.

GAO reviewed relevant literature, including peer-reviewed studies and reports published from January 2021 through July 2025 by researchers, stakeholder groups, and others. GAO also interviewed or received written responses from 14 selected stakeholders, as well as four organizations that collect or analyze relevant data on physician employment. Stakeholders included groups representing physicians, hospitals, health insurers, private equity firms, retail companies, and employers.

What GAO Found

Physicians have become increasingly consolidated as the share of physicians in practices owned by other entities has increased over time. For example, studies show that at least 47 percent of physicians were employed by or affiliated with hospital systems in 2024, up from less than 30 percent in 2012. Estimates of the share of physicians consolidated with health insurers and corporate entities vary. Private equity ownership of or investment in physician practices represents a small but growing share of physicians nationally—about 6.5 percent in 2024—but shares varied by specialty and geographic market, according to studies GAO reviewed.

Studies indicate that physician consolidation with hospital systems can lead to increased spending and prices. For example, several studies found increased Medicare spending due to services being provided in more expensive hospital-based settings and increases to prices paid by commercial insurers following hospital-physician consolidation. In contrast, this type of consolidation generally resulted in no changes in the quality of care.

Studies examining the effects of physician consolidation involving private equity firms were limited, but provided some evidence of price increases for commercial insurance.

There were several areas where GAO did not identify rigorous studies on the effects of physician consolidation. These areas include the effects of

· consolidation by hospital systems on patient access to care;

· consolidation by insurers or other corporate entities on spending, prices, quality, or access; and

· private equity investment on quality and access.

Abbreviations

|

CMS |

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services |

|

DOJ |

Department of Justice |

|

FTC |

Federal Trade Commission |

|

HHS |

Department of Health and Human Services |

|

MSO |

management services organization |

|

MedPAC |

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission |

|

MSA |

metropolitan statistical area |

|

PECOS |

Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

September 22, 2025

The Honorable Shelley Moore Capito

Chair

The Honorable Tammy Baldwin

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

United States Senate

The Honorable Robert Aderholt

Chairman

The Honorable Rosa DeLauro

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

Many health care markets have become consolidated as providers and other entities have merged, acquired, or affiliated. For example, 1,500 hospitals were acquired by or merged with another hospital or health system from 2010 through 2019.[1] We have previously reported on consolidation of certain types of health care entities, including physicians and nursing homes.[2] Physician practices are also consolidating with other entities, leaving fewer private or independent practices.[3] Physician practices can merge together or be acquired by other types of entities, such as hospital systems; corporate entities, including health insurers; and private equity firms.[4] Physician practices can also affiliate with other entities—sometimes referred to as a form of “soft consolidation”—in which they typically share billing and administrative functions while retaining some degree of practice ownership.[5]

While consolidation has the potential to improve efficiency, it also has the potential to impede competition and contribute to increased costs to patients, employers, health insurers, and federal health care programs, such as Medicare and Medicaid. Further, questions have arisen about the effects of consolidation on quality and access to care.[6] For example, in 2024, the Department of Justice (DOJ), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) requested public comments on the effects of consolidation, including on patients, communities, employers, and others, due to concerns that some consolidation transactions may enhance profits at the expense of patient care.[7]

House Report 117-403 included a provision for us to study the extent health care consolidation is taking place across Medicare and Medicaid markets, and how private equity could be contributing.[8] In this report, we describe what available research indicates about

1. the extent of physician consolidation, including practice ownership by hospital systems, corporate entities, or private equity firms; and

2. the effects of these types of physician consolidation on health care spending and prices, quality of care, and access.

To answer both objectives, we reviewed relevant literature, including peer-reviewed studies and reports published by researchers, stakeholder groups, and others. To the extent we obtained information about physician consolidation and its effects on Medicare or Medicaid, we report this, but our scope was not limited to these programs.[9] To identify relevant literature, we conducted searches in selected research databases for empirical studies published from January 2021 through August 2024.[10] We supplemented these studies with relevant literature published from January 2021 through July 2025 recommended to us by stakeholders, cited in other published literature reviews, or that we identified ourselves. We excluded studies that only analyzed data from 2014 or earlier.

We initially identified and reviewed 100 studies that estimated the extent or effects of physician consolidation on health care spending, prices, quality of care, or access. For studies that examined extent, we reviewed those that examined practice size, number of practices by specialty, and consolidation between physician practices and other entity types (e.g., hospital systems, health insurers, and private equity firms) that involved physician employment, practice ownership, acquisition, integration, or affiliation arrangements. For studies that examined effects, we primarily limited our review to those that aimed to establish causality between physician consolidation involving these entity types and changes in prices (i.e., payment rates), spending, quality, or access. Of those, we assessed whether the identified studies applied a robust and recognized methodological approach, such as difference-in-difference regression, to control for other factors, such as regional variation in market concentration, that could simultaneously affect the measured outcomes.[11] Further, we assessed the studies’ selection of outcome measures and populations they examined. We did not include in our analysis studies that used methods that could not support causal inferences, such as correlations and surveys, or that had insufficient data or limited controls for potential confounding factors.[12]

We reviewed studies that examined changes in spending and prices, because increases in prices do not always lead to an increase in spending and vice versa.[13] The studies we reviewed that examined the effects on Medicare were limited to looking at changes in spending in traditional fee-for-service Medicare because these prices are set administratively by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) through regulations and policy.[14] In contrast, studies about commercially insured patients can examine effects on prices because they are negotiated between health plans and providers.

We also drew on a literature review published by RAND Health Care that examined studies published from 2004 through 2022 on the effects of consolidation among physicians to supplement our understanding of these effects based on studies that were largely completed prior to our period of review.[15]

In addition, to help inform both objectives, we interviewed stakeholders and other organizations representing the types of parties involved in or affected by physician consolidation. Specifically, we interviewed a nongeneralizable selection of 14 stakeholder associations or groups representing physicians, hospitals, health insurers, private equity firms, retail companies, and employers.[16] We also spoke with individuals representing four organizations that collect or analyze relevant data sources on physician employment, including the American Medical Association and IQVIA, to better understand the benefits and limitations of those data sources. Lastly, we interviewed selected researchers and actuaries to gather additional background information and an understanding of the published literature.

We also interviewed officials from HHS, including from the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation and CMS; as well as FTC and DOJ about their roles in monitoring physician consolidation. Finally, we reviewed a nonrandom sample of public comments submitted in response to a request for information on health care consolidation issued by DOJ, HHS, and FTC in February 2024, as well as a summary report on the public comments issued in January 2025 by HHS, in consultation with DOJ and FTC.[17]

We conducted this performance audit from March 2024 to September 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Types of Physician Consolidation

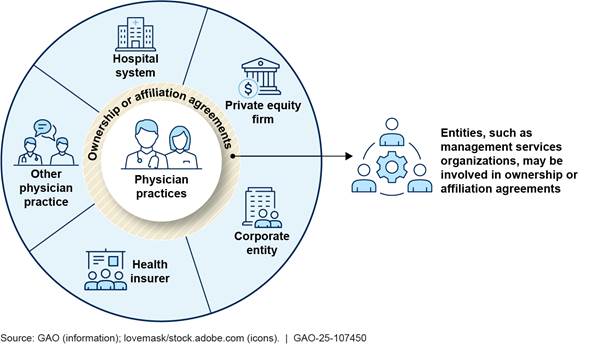

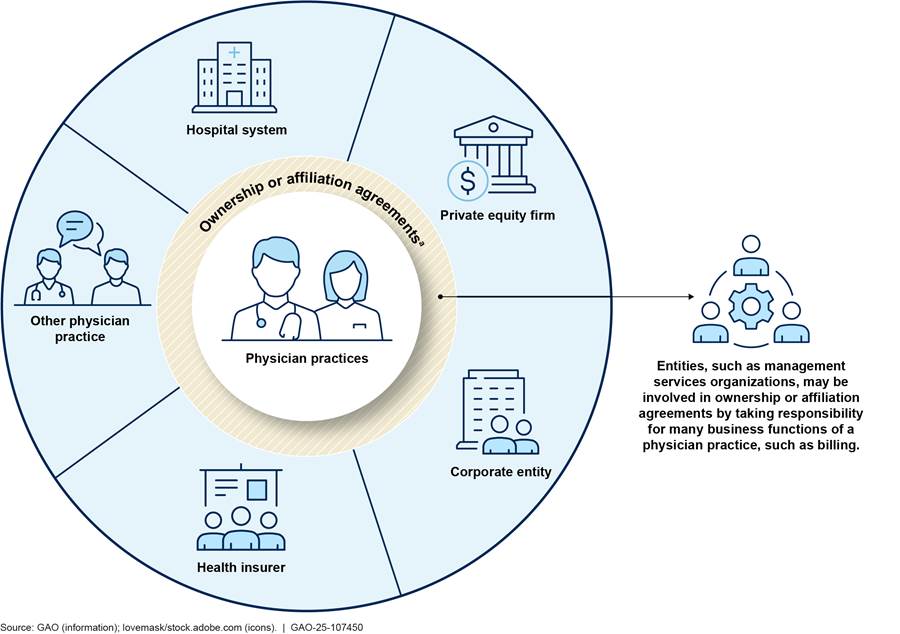

Physician consolidation can occur when physician practices merge together (horizontal consolidation) or when practices are acquired by other types of entities (vertical consolidation).[18] The types of entities that may acquire physician practices range from hospital systems and health insurers, to corporate entities (e.g., retail companies and medical supply companies), and private equity firms (see fig. 1). These entities may be publicly traded for-profit companies, private for-profit companies, or nonprofit organizations, and can acquire physician practices wholly or partially along with other investors. The nature of these arrangements can be complex and not easily understood. Physician practices can also affiliate with entities such as clinically integrated networks or management services organizations (MSO) that enable physicians to maintain ownership of the practice while still exhibiting some characteristics of consolidation, such as joint negotiations with insurers, shared billing, and care coordination.

aPhysician consolidation can occur through acquisitions of physician practices by other entities, as well as affiliation agreements between physician practices and other organizations.

MSOs may be involved in physician consolidation through ownership or affiliation agreements.[19] In exchange for a fee or equity stake in the practice, MSOs provide services that can include billing and collection, negotiating prices with insurers, information technology (e.g., electronic health records), human resources, marketing, and space and equipment. The American Independent Medical Practice Association describes affiliation with MSOs as a way for practices to maintain their independence in an increasingly consolidated landscape.[20] MSOs also can serve as the vehicle through which corporate entities and private equity firms invest in or acquire physician practices. For example, private equity firms or corporate investors may acquire MSOs that physician practices affiliate with rather than acquiring the practices directly. In this way, investors can hold equity in physician practices while complying with state laws that can prohibit non-physicians from owning or operating medical practices, referred to as “corporate practice of medicine” laws.[21]

Physician management companies also are involved in consolidating physician practices and employing physicians. These companies, also known as physician staffing firms, provide physician services that include staffing physicians at hospitals and negotiating payments amounts with insurers. Physician management companies have various ownership structures and can be physician-owned, publicly traded, or backed by private equity investment.[22]

Factors that May Contribute to Physician Consolidation

Physician practices, hospital systems, corporate entities, and investors, such as private equity firms, may seek to acquire, affiliate with, merge, or invest in physician practices for a variety of reasons. These reasons include to attain higher reimbursement, gain greater market share, increase profitability, preserve access to care, better manage costs, or advance other interests, according to researchers and stakeholder groups we spoke with.

Physician practices. According to a survey conducted by the American Medical Association, the most common reasons physicians sell their practice include a desire to enhance their ability to negotiate higher payment rates with insurers, to improve their access to costly resources, or to reduce administrative and regulatory burdens.[23] Stakeholders that represent physicians told us that maintaining a private practice has become increasingly difficult, as certain practice expenses have increased faster than revenues. With greater consolidation, remaining independent practices may face additional challenges, such as reduced ability to negotiate contracts and payments with insurers or to receive referrals from other physicians. This could, in turn, lead them to look for partners to acquire or affiliate with their practice. For physicians approaching retirement, selling their practice may also be an attractive option.

Rather than sell or merge with another practice, physician practices may opt to affiliate with other entities. For example, practices may affiliate with a local hospital system to allow the physicians to perform procedures at the hospital, bill using the hospital’s negotiated rates, participate in the hospital’s value-based care programs, and use the hospital’s electronic health records system.

Hospital systems. Hospital systems, also known as health systems, may acquire or affiliate with physician practices to gain additional revenue for physician services.[24] For example, consolidation between hospitals and physicians can result in higher payments for certain physician services when provided in a hospital outpatient department.[25] Hospital system acquisition of physician practices may also increase their market share and, in turn, their bargaining power to negotiate higher payment rates from commercial insurers. They may also acquire physician practices to generate referrals for services offered within the hospital system.

In addition, according to hospital stakeholders we spoke with, acquiring physician practices may help hospital systems navigate the shift away from fee-for-service payment to value-based payment models.[26] They said acquiring physician practices could help hospital systems coordinate care across health care settings. Hospital systems may also acquire physician practices to maintain access to services by preventing practice closures, particularly in rural areas, and ensuring that these services will be available to patients seeking care within their system, according to hospital stakeholders we spoke with.

Health insurers. Health insurers may acquire physician practices to gain leverage for negotiating with hospital systems and other providers, lower the costs of care, and facilitate participation in value-based payment models, among other reasons. Improving their ability to negotiate prices with hospitals may allow insurers to reduce payments for services, and acquiring their own network of providers may prevent hospitals from steering patients to higher cost providers within their systems. Acquiring physician practices may also give insurers influence over the care provided by physicians in their network, with a goal of improving quality and patient outcomes while reducing or holding greater control over costs. It could also enable them to refer members to care provided by other subsidiary providers, such as ambulatory surgery centers. Insurers that have acquired physician practices can also design plan benefits to encourage members to seek care within the insurer’s affiliated group of practices.

Acquiring or affiliating with physician practices could also provide insurers that cover Medicare beneficiaries with additional influence over how physicians document patient conditions and how insurers assess patient risk. For example, Medicare Advantage organizations have a financial incentive to ensure that their physicians record all possible patient diagnoses because adding them can result in higher payments for enrolled Medicare beneficiaries.[27] Also, some have posited that another potential advantage may be to apportion payments to physician practices they own as medical expenses or costs and not excess revenues or profits for the purposes of meeting medical loss ratio requirements for Medicare Advantage or other payers.[28]

Other corporate entities, including retail companies. Retail companies and other corporate entities, such as medical distributors, may view acquiring or investing in physician practices as a business opportunity. For example, some retail companies acquire physician practices that primarily serve Medicare Advantage beneficiaries, in part, due to the projected growth of the population and increasing enrollment in Medicare Advantage.[29] Retail companies may be motivated to acquire physician practices to increase access to patient data to inform their marketing and ultimately, increase revenue for the company. Retailers may also seek to attract patients to physician practices located within or near their stores.

|

Private Equity Investments Private equity firms commonly invest funds from large institutional investors, such as pension funds or university endowments, and smaller investors such as family offices. They often invest in companies that are not publicly traded and may finance their investments through a combination of borrowed funds (debt) and equity. Known as a leveraged buyout, the assets of the acquired business are used as collateral for the loan and the acquired business becomes responsible for making payments on the loan. In addition, private equity firms may charge management or consulting fees to the entities they acquire. Source: Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Report to Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, Chapter 3: Congressional Request: Private Equity and Medicare (Washington, D.C.: June 2021); and Congressional Research Service, Private Equity and Capital Markets Policy, R47053 (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 28, 2022). | GAO‑25‑107450 |

Private equity firms. Firms that manage private equity funds invest in physician practices with a goal to improve financial performance and typically look to sell their shares for a profit within 3 to 10 years. One strategy to do so is to link multiple physician practices to shared administrative and financial functions, often via an MSO, with the goal of reducing costs. Private equity firms may also consolidate several smaller physician practices in the same or related specialties, known as a roll-up or serial acquisition strategy, in order to increase market share and improve negotiating leverage with insurers. According to private equity stakeholders we spoke with, some private equity firms are focused on the Medicare population and invest in practices in geographic areas with growing senior populations and practices that are transitioning from fee-for-service to value-based care models, which can offer new revenue streams and cost-saving opportunities.

Government Agency Roles

Federal agencies have a role enforcing federal antitrust laws and overseeing Medicare enrollment of individual and organizational health care providers. Specifically, FTC and DOJ review certain mergers and acquisitions of physician practices as part of their responsibilities for enforcing federal antitrust laws.[30] One of these laws, the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, requires parties involved in certain mergers and acquisitions, including those involving health care entities, valued at $126.4 million or greater (as of 2025) to report their transactions to both agencies before closing.[31] The agencies can sue in federal court to block transactions or behaviors they believe would be anticompetitive, including roll-ups facilitated by private equity firms, even if the agencies did not receive notification of the transactions, according to FTC and DOJ officials.[32]

However, parties involved in mergers and acquisitions are not required to report transactions that fall below the statutory reporting threshold, which includes many physician practice acquisitions, according to agency officials. As a result, the FTC and DOJ may not become aware of such mergers and acquisitions. As of June 2025, FTC was studying the effects of mergers of physician practices, including acquisitions by hospital systems, on provider prices, patient outcomes, and competition.[33] FTC stated that through these studies, it seeks to better understand how consolidation in these markets has affected competition to assist the agency to better utilize its enforcement resources and evaluate its merger forecasting tools. FTC intends to release a series of research papers with their findings over time.[34]

CMS, the agency within HHS that oversees Medicare and Medicaid, has responsibility for enrolling providers in the Medicare program.[35] As a part of that activity, the agency collects some ownership information from physicians and physician practices that provide services to Medicare beneficiaries through the Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS).[36] This information is self-reported, and CMS does not independently verify it or use it to conduct research on physician consolidation.[37]

In 2024, federal agencies sought information from the public about the effects of health care consolidation. For example, as noted above, DOJ, HHS, and FTC issued a joint request for information, which collected comments from the public on the effects and objectives of health care consolidation transactions and how federal agencies should respond.[38] HHS, in consultation with DOJ and FTC, also published a report summarizing the comments.[39] In addition, CMS requested information from the public in 2024 about data related to the Medicare Advantage program, including about the effect of mergers and acquisitions by insurers, and the effects of consolidation with physician practices.[40] According to CMS officials, CMS has not taken additional action related to this request as of May 2025.

In addition to federal reporting requirements, some states have enacted laws that mandate notification to state attorneys general or state agencies by parties involved in health care mergers and acquisitions when those transactions meet certain criteria. For example, Massachusetts law requires health care providers to notify the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission of mergers and acquisitions and affiliation agreements if any of the companies involved in the transaction exceed $25 million in net patient revenue in the state, and transactions can be referred to the state attorney general for action, as needed.[41]

Data Limitations to Estimating Physician Consolidation

No single data source exists to accurately identify physicians who work in consolidated practices and those who remain independent. Available data sources that researchers may use to examine physician practices include PECOS, claims data (e.g., from Medicare or commercial insurers), physician survey data, or other proprietary data that tracks acquisitions, physicians, and their places of practice and practice ownership. Differences in how researchers define and measure consolidation can lead to different estimates for the extent and effects of physician consolidation. For example:

· Some estimates measure only physicians who are directly employed or whose practice is owned by another entity, while others include affiliation relationships in their estimates.

· Associating physicians with a physician practice can be complex because physicians can work in or be affiliated with multiple settings with different owners. Claims-based estimates may necessitate a judgment about how to consider each physician’s consolidation status based on the tax identification numbers or place of service codes they use when billing for services.[42] Survey-based estimates rely on the physicians’ response to questions about who owns the practice where they work. Thus, estimates of consolidation based on claims and surveys would likely vary. For example, physicians who consider themselves independent, yet are affiliated with a hospital, may appear in a claims-based estimate as being consolidated with the hospital, but could appear in a survey-based estimate as being independent. Also, researchers from RAND Health Care noted a lack of data that identifies nonowner affiliations between hospital systems and physicians because existing administrative data sets do not capture these relationships.[43]

· Studies that report on private equity ownership of physician practices often use data on private equity transactions, but they do not differentiate between private equity acquisitions of practices, in whole or in part, versus acquisitions of MSOs that practices affiliate with. As a result, the specific ownership arrangements between private equity firms and physician practices, including ownership shares, are not always known.

· Practices that are owned by physicians are generally considered to be independent or private; however, data sources may measure this differently. For example, physicians in practices affiliated with MSOs may consider themselves independent when responding to a survey, but their practices may appear in other data sources as being private equity-backed for the reasons described above.

In addition, obtaining accurate estimates can require time-intensive work. For example, this research may require manual internet searches to track physician practice acquisitions. Challenges in measuring physician employment, practice ownership, and affiliation could contribute to gaps in understanding the extent and effects of physician consolidation by hospital systems, corporate entities, and private equity firms.

Studies Indicate Physician Consolidation Has Increased Due to Acquisitions by Hospital Systems and Others

Studies we reviewed show physicians are increasingly consolidated with hospital systems and other types of entities, including corporate entities and private equity firms, although estimates of ownership by these entities vary. Private equity investment in physician practices represents a small but growing share of physicians nationally, but their investment can vary by specialty and geographic market, according to studies we reviewed.

Estimates indicate that the share of physicians working in a physician-owned independent or private practice has decreased as ownership by other entities has increased. For example, the American Medical Association estimates that the share of physicians working in private practice decreased from 60 percent in 2012 to 42 percent in 2024.[44]

Hospital Systems

Studies we reviewed indicate that a large share of physicians are consolidated with hospital systems and that this share has increased over time. For example, available estimates of hospital-physician consolidation indicate that at least 47 percent of physicians were employed by or affiliated with hospital systems in 2024, up from less than 30 percent in 2012 (see table 1).

|

Source of study |

Description of findings and measurement parameters |

|

American Medical Association |

About 47 percent of physicians nationally were employed by a hospital system or worked for a practice that was wholly or partially owned by a hospital system in 2024, up from 29 percent in 2012.a |

|

Physicians Advocacy Institute |

About 55 percent of physicians were employed by or affiliated with hospital systems in 2024, up from 26 percent in 2012.b About 28 percent of physician practices were owned by hospital systems in 2024. |

|

Compendium of U.S. Health Systems |

Fifty-seven percent of physicians were affiliated with hospital systems in 2023, up from 51 percent in 2018.c |

Source: Estimates from the American Medical Association, Physicians Advocacy Institute, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. | GAO‑25‑107450

aSee Carol Kane, Physician Practice Characteristics in 2024: Private Practices Account for Less Than Half of Physicians in Most Specialties (Chicago, Ill.: American Medical Association, 2025). The American Medical Association’s estimate is based on a biennial survey of physicians.

bSee Physicians Advocacy Institute, Updated Report: Hospital and Corporate Acquisition of Physician Practices and Physician Employment 2019-2023 (Avalere Health, April 2024). This estimate is based on an analysis of IQVIA OneKey data and represents physicians whose primary place of practice is part of a hospital or health system.

cThe 2023 estimate was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The 2018 estimate is from Health Affairs Forefront, “Consolidation and Mergers Among Health Systems in 2021: New Data from the AHRQ Compendium” (June 2023).

While these estimates show that significant hospital-physician consolidation has occurred, an analysis by the American Hospital Association looked at acquisitions differently. They reported that acquisitions by hospital systems accounted for a small share of physicians whose practices were acquired between 2019 and 2023, suggesting that hospitals may not have been the primary acquirers of physician practices in recent years.[45]

Variation in the magnitude of these estimates is likely due to how researchers defined and measured hospital-physician consolidation, as noted earlier in this report. For example, the American Medical Association’s estimate is based on physicians who self-reported that they were either employed by or their practice was wholly or partially owned by a hospital system. In comparison, the Physician Advocacy Institute’s estimate is based on a data source that combines market research and administrative data to determine each physician’s practice ownership status, be it with a hospital system, corporate entity, or neither. Their estimate of hospital-physician consolidation likely includes a broader number of physicians because it includes physicians who were affiliated with hospital systems, in addition to those employed by a hospital system.

Studies also presented estimates of the extent of hospital-physician consolidation by geography and specialty. The Physicians Advocacy Institute study found that hospital-physician consolidation was highest in the Midwest, with 66 percent of physicians employed by or affiliated with hospital systems in 2024. Another study by this organization reported that the share of physicians employed by or affiliated with hospitals systems in 2024 was 58 percent in rural areas in 2024, up from 48 percent in 2019.[46] Regarding physician specialty, one study found that nearly half—48 percent—of primary care physicians were consolidated with hospitals and another found that one-third of orthopedists were hospital-consolidated in 2022.[47] Another study found that the proportion of patients treated by oncologists that were consolidated with a hospital system increased from 28 percent in 2008 to 55 percent in 2017.[48]

Insurers and Other Corporate Entities

Estimates of physician consolidation by health insurers and corporate entities vary, but some evidence suggests an increase in recent years. One estimate that focused on physician-insurer consolidation found that about 2 percent of physicians worked in practices owned by health insurers; however, this estimate likely does not include physicians who are in practices that are affiliated with, but not owned by, insurers. Other studies estimated the extent of physician practice ownership by insurers combined with other corporate entities. For example, a study by the Physicians Advocacy Institute found physician employment by corporate entities increased from 15 percent in 2019 to 23 percent in 2024. See table 2 for more detailed summaries of these studies. In addition, another study that examined primary care practices found that insurer-operated primary care physician practices accounted for about 4 percent of the national primary care market that serves the Medicare population by service volume in 2023, up from less than 1 percent in 2016.[49] This study also found that insurer-operated primary care market share was higher (5.5 percent) in counties with higher Medicare Advantage penetration compared to the market share (1.5 percent) in counties with lower penetration.[50]

Table 2: Estimates of Physician Consolidation with Health Insurers and Other Corporate Entities from Selected Studies

|

Source of study |

Description of findings and measurement parameters |

|

American Medical Association |

About 2 percent of physicians worked in practices owned by health insurers in 2024.a |

|

Physicians Advocacy Institute |

About 23 percent of physicians nationally were employed by corporate entities—which includes health insurers and private equity firms—in 2024, up from 15 percent in 2019.b This share was lower in rural areas where about 18 percent of physicians were employed by corporate entities in 2024.c |

|

Avalere |

About 37 percent of physicians in five specialties (cardiology, gastroenterology, medical oncology, orthopedics, and urology) were affiliated with corporate entities, which included insurers and management services organizations owned or operated by a corporate entity in 2022.d |

Source: American Medical Association, the Physicians Advocacy Institute, and Avalere. | GAO‑25‑107450

aSee Carol Kane, Physician Practice Characteristics in 2024: Private Practices Account for Less Than Half of Physicians in Most Specialties (Chicago, Ill.: American Medical Association, 2025). The American Medical Association’s estimate is based on a biennial survey of physicians. This estimate represents physicians who responded that they worked in a practice owned by a health insurer. This specific estimate was provided to GAO by the American Medical Association.

bSee Physicians Advocacy Institute, Updated Report: Hospital and Corporate Acquisition of Physician Practices and Physician Employment 2019-2023 (Avalere Health, April 2024). This estimate is based on an analysis of IQVIA OneKey data.

cSee Physicians Advocacy Institute, “Rural Areas Face Steep Decline in Independent Physicians and Practices.”

dSee Avalere, “Medicare Service Use and Expenditures Across Physician Practice Affiliation Models” (September 2024). This estimate is based on an analysis of IQVIA OneKey data.

As with estimates of hospital-physician consolidation, variation in estimates of physician consolidation with corporate entities and insurers is likely due to how the data sources measure practice ownership. For example, survey-based estimates rely on physicians to self-report who owns their practice, which in some cases may be unclear when physicians are part of organizations with complex ownership structures. Estimates based on other data sources must make ownership determinations based on available information and may not distinguish between practices that are owned by versus affiliated with a corporate entity.

Although estimates of physician employment or practice ownership by health insurers are limited, our review of company press releases and reporting on insurer acquisitions found that all 10 of the nation’s largest health insurers have acquired a physician practice or MSO in recent years, suggesting an increase in this type of vertical consolidation.[51] For example:

· UnitedHealth Group formed its Optum subsidiary in 2011, which has acquired many physician practices. As of May 2024, Optum reportedly employed about 9,000 physicians and was affiliated with another 90,000, representing about 10 percent of physicians nationwide.[52] According to one study, Optum held 2.7 percent of the national primary care market in 2023.[53]

· CVS Health, which owns Aetna, acquired Oak Street Health in 2023. Oak Street Health is a network of primary care centers focusing on the Medicare population, some of which are located inside or next door to CVS’s retail stores. According to the company’s website, in July 2025 they operated over 200 locations and employed more than 900 primary care providers.

· Elevance Health (formerly Anthem, Inc.) merged various aspects of its business to form Carelon Health in 2022, an integrated health plan and care delivery system for Medicare and Medicaid patients. As of July 2025, Carelon Health operated primary care centers in seven states.[54]

Similarly, the extent of physician consolidation by retail organizations is unknown as we did not identify any estimates that examined this type of consolidation. However, there are recent examples of large retail corporations acquiring or affiliating with physician practices, although some have subsequently sought to sell their practices. For example:

· Amazon partnered with One Medical, a network of primary care clinics, in 2023. As of April 2024, One Medical was reported to operate nearly 240 primary care clinics in more than 20 U.S. markets. Amazon acquired the MSO that provides all of One Medical’s management functions, such as billing and information technology.[55]

· In 2021, Walgreens became the majority owner of VillageMD. In 2023, VillageMD acquired Summit Health-CityMD, expanding its provider network to 680 locations in 26 markets. However, the company later closed 140 of these clinics, reportedly to cut costs and improve profitability. In August 2025, Walgreens’ parent company was acquired by a private equity firm, which announced its intention to sell its shares of VillageMD.

· Walmart opened 51 Walmart Health Clinics in five states beginning in 2019, but closed them all in April 2024. The company stated that reimbursement issues and increasing operating costs made the business unsustainable.

Further, some large health care corporations whose businesses include distributing medical products to health care providers have acquired MSOs that serve certain physician specialties. For example:

· McKesson purchased U.S. Oncology in 2010, which has continued to expand since then. U.S. Oncology is a network of independent oncology practices with over 2,700 physicians.

Cardinal Health acquired two MSOs in 2024: GI Alliance, an MSO that supports over 900 gastroenterologists, and Integrated Oncology Network, an MSO with over 100 oncologists in 10 states.

Private Equity

|

Example of a Private Equity Firm’s Roll-Up of Gastroenterology Practices Private equity firms can facilitate the consolidation of physician practices through acquisition of multiple smaller practices, known as roll-up acquisitions. For example, in 2018, a private equity firm invested in a large gastroenterology practice that had 110 locations across several states to jointly create and partially own a management services organization (MSO). From 2018 to 2022, the newly created MSO added 33 additional gastroenterology practices to its portfolio, resulting in a network of over 400 locations, and a valuation of $2.2 billion. In 2022, the private equity firm sold its minority ownership stake in the MSO back to the physicians, who funded their buyback with support from another private equity firm. Source: Scheffler, Richard et al., Monetizing Medicine: Private Equity and Competition in Physician Practice Markets, American Antitrust Institute, Petris Center, and Washington Center for Equitable Growth (2023). | GAO‑25‑107450 |

Private equity firms’ investment in physician practices represent a small but growing share of physicians nationally, although estimates of this type of consolidation varied by specialty. According to a nationally representative survey of physicians conducted by the American Medical Association, about 6.5 percent of physicians worked in private equity-owned practices in 2024, up from 4.5 percent in 2022.[56] This survey asked physicians if their practice was wholly or jointly owned by a private equity firm. Looking at specific specialties, studies reported a range in the percentages of physicians employed by private equity-backed practices by specialty and that those proportions have increased over time. For example:

· One study found that roughly 1.5 percent of primary care physicians were part of private equity-backed practices in 2022, while another study found 29 percent of retina specialists worked at private equity-backed practices in the same year.[57]

· Another study found that private equity firms invested in practices employing 6 percent of radiologists in 2021, up from about 1 percent in 2012; and in practices employing 11 percent of dermatologists in 2021, up from roughly 2 percent in 2012.[58]

Despite the low overall share of physicians in private equity-backed practices, the American Hospital Association estimated that private equity accounted for the majority of physician practice acquisitions from 2019 through 2023—representing 65 percent of physicians whose practices were acquired by any type of entity.[59] In addition, private equity stakeholders told us that private equity firms are increasingly collaborating with health insurance companies to invest in physician practices.

Studies we reviewed also found variation in private equity investment by geographic market. One study reported that private equity firms collectively invested in over 30 percent of certain physician specialties in some markets, defined as metropolitan statistical areas (MSA); for some specialties, it was over 50 percent.[60] For example, it estimated private equity firms had invested in practices employing more than 30 percent of gastroenterologists in 11 percent of MSAs, and more than 50 percent of dermatologists in 4 percent of MSAs. In most of those MSAs, a single private equity firm held that market share. Another study that examined private equity investment in urology found variation by state.[61] For example, it estimated 28 percent of urologists in New Jersey were employed by private equity-backed physician practices in 2021, compared to less than one percent of urologists in Indiana.

Studies Indicate Physician Consolidation Can Increase Spending and Prices; the Effects on Quality and Access were Less Clear

Studies we reviewed suggest that physician consolidation with hospital systems can, but does not always, lead to increased spending and prices, and no change or a decrease in the quality of care provided. However, the effects of physician consolidation with health insurers, other corporate entities, or private equity firms on spending, prices, and quality were less clear or unknown. Further, we did not identify any studies that sufficiently examined the effects of physician consolidation with any entity type on access to care.

Effects of Physician Consolidation on Spending and Prices

Several studies we reviewed suggest that physician consolidation with hospital systems can lead to increased spending and prices.[62] We did not identify any studies that sufficiently examined the effects of physician consolidation by insurers or other corporate entities on spending or prices; studies on the effects of investment by private equity firms that met rigorous methodological standards were limited, but found some evidence of increases for commercial insurance.[63]

Hospital Systems

We reviewed studies that examined the effect of hospital-physician consolidation on spending by both Medicare and commercial insurance and prices (i.e., payment rates) for commercial insurance. In addition to examining different insurance types, studies spanned different years and different physician specialty types.

Medicare. Studies that we reviewed generally found that hospital-physician consolidation resulted in some degree of increased spending in traditional Medicare. For example, three studies we reviewed found increased Medicare spending as a result of more services being provided in hospital-based settings, which result in higher payments (see text box). One of the three studies found that total spending per Medicare patient increased by 5 percent for selected elective surgery services from 2010 through 2015, due in part to the substitution of physician office visits with visits in more expensive hospital-outpatient facilities.[64] The second study found that consolidation between hospitals and primary care physicians from 2013 through 2016 led to $40 million in increased spending in traditional Medicare for certain imaging procedures and $33 million for certain lab tests, largely due to a shift in the site of service to hospital settings.[65] Similarly, the third study found that Medicare spending on colonoscopies increased by an average of $3,851 per year from 2012 through 2015 for each gastroenterologist who consolidated with a hospital.[66] The study’s authors attributed this increase to an increase in facility fees following consolidation and physician throughput.

|

Medicare Payment of Facility Fees for Physician Services According to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), as hospitals have acquired more physician practices and employed more physicians, large shifts in Medicare billing have occurred in four service categories—chemotherapy administration, echocardiography, cardiac imaging, and office visits—due to the introduction of hospital facility fees for services provided in hospital-based physician practices (hospital outpatient departments). For example, MedPAC found that the share of office visits provided to beneficiaries in traditional Medicare in hospital outpatient departments grew from about 10 percent in 2012 to 13 percent in 2019, and the share of chemotherapy administration services provided in hospital outpatient departments rose from about 35 percent to 51 percent. MedPAC also reported that the shift of office visits from the physician office setting to the hospital outpatient department setting increased Medicare spending in traditional Medicare by $615 million and beneficiary cost sharing by $150 million from 2015 through 2019. In 2012 and 2014, MedPAC recommended eliminating this payment differential by applying “site-neutral” payment rates for physician services provided in hospital outpatient departments, which would reduce incentives to shift the billing of Medicare services from low-cost settings to high-cost settings and result in lower Medicare program spending and beneficiary cost sharing. Further, we have long recommended that Congress consider directing the Department of Health and Human Services to equalize payments between hospital outpatient departments and physician offices to lower Medicare costs. While Congress has taken actions to limit certain hospital outpatient departments from billing at higher rates (Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-74, § 603, 129 Stat. 584, 597), Medicare could realize additional savings if Congress applied this limitation to additional outpatient departments and services. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that paying hospital outpatient departments the same as physician offices would save almost $157 billion from 2025 through 2034. |

Source: GAO summary of Medicare Payment Advisory

Commission, Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery

System, pp. 166-167 (Washington, D.C.: June 2022); and GAO, Medicare:

Increasing Hospital-Physician Consolidation Highlights Need for Payment Reform,

GAO‑16‑189

(Washington, D.C.: Dec. 18, 2015). | GAO‑25‑107450

Another study found no change in overall spending in traditional Medicare from 2013 through 2017 across all patients following hospital-physician consolidation, but found variation depending on a patient’s health status and need for care.[67] Specifically, it found that primary care physician consolidation with hospitals led to decreased spending for healthier patients, but led to a 10 percent increase in spending per year for relatively sicker patients.

In contrast to studies that found increased spending, another study found no significant change in traditional Medicare spending from 2008 through 2017.[68] Specifically, this study examined differences in Medicare spending among patients in the first 3 months of treatment for a specific type of prostate cancer whose oncologists were consolidated with hospitals compared to those whose oncologists were not.

Commercial insurance. We reviewed two studies that examined the effect of hospital-physician consolidation on commercial insurance spending: one found decreased spending per patient over time and the other found increased spending.

· An analysis of national commercial claims data from 100 medium and large employers, found that while office visit prices increased by 17 percent after physicians consolidated with hospitals, overall spending per patient decreased from 2010 through 2016.[69] The study found increases in care coordination and decreases in care fragmentation, inpatient utilization, prescription drugs, lab and imaging, and the use of out-of-network providers following physician consolidation.

· However, another study found a 6 percent increase in total spending per patient per year from 2013 through 2017 among commercially insured patients in Massachusetts whose primary care physicians became consolidated with a hospital system.[70] The authors found this spending increase was associated with a 23 percent increase in the number of specialist visits per patient per year during that time period.

Studies that we examined on the effect of hospital-physician consolidation on prices paid by commercial health insurers to providers found that hospital-physician consolidation generally led to price increases.

· As previously noted, one study found a 17 percent increase in office visit prices following hospital-physician consolidation from 2010 through 2016.[71]

· A study found that hospital prices for inpatient stays increased by an estimated 3 percent to 5 percent between 2009 and 2015 as a result of hospital-physician consolidation, which the authors found could be due, in part, to increased market share and stronger bargaining leverage with insurers.[72]

· Another study found that consolidation between hospital systems and obstetricians and gynecologists from 2011 through 2016 led to commercial price increases for childbirths: 15 percent for physician services and 3 percent for hospital services.[73] The authors attributed this to less competition resulting from the consolidation.

· One study found that hospital-affiliated physicians in four specialties were least likely to provide selected services in a lower-cost setting.[74] For example, the study found that the probability of receiving a cardiac stress test in a physician’s office or ambulatory surgery center in 2022 was 54 percent for Medicare patients with hospital-affiliated physicians, compared to 85 percent to 86 percent for other types of physicians. The authors also noted that commercial reimbursement for a stress test performed in a high-cost setting (i.e., hospital outpatient department) was about 2.5 times higher than when performed in a lower cost setting.

· Another study found that hospital ownership of physician practices was associated with higher physician prices for primary care, orthopedics, and cardiology office visits, but not for obstetrics and gynecology or oncology visits between 2012 and 2016, according to another study we reviewed.[75]

· A study that examined the effects of participation by independent primary care practices in a hospital-led Medicare accountable care organizations, which is considered by some to be a soft form of consolidation because it can entail joint price negotiations involving the physician practices and the hospital system without an ownership change. The study found evidence of increases to commercial office visit prices after joining.[76] The study found modest price increases (4 percent) on average, with a 20 percent or greater increase for a small share (7 percent) of physician practices following participation in the accountable care organization. The authors stated that the larger price increases were likely due to an extension of the hospital systems’ existing pricing power to the independent practices.[77]

A literature review conducted by RAND Health Care that assessed studies on the effects of hospital-physician consolidation reported findings that are consistent with the literature we reviewed on Medicare and commercial spending and prices.[78] It reported that nine studies found increases in medical spending associated with hospital-physician consolidation, and six studies showed increases in prices after hospitals acquired or shared ownership with physician practices.[79]

Representatives from one of the hospital stakeholder groups we spoke with explained that when a hospital system acquires a physician practice, spending increases may result from increases in utilization and patient access to care. They also noted that hospital systems may incur additional costs to improve the financial stability of practices they acquire, which could require offsetting price increases to recoup.

Insurance stakeholders we spoke with voiced their concern that physician consolidation with hospital systems has led to an increase in prices and spending, particularly for commercially insured patients, because commercial insurers pay significantly more than Medicare for hospital-based services.[80] In addition, they noted that the recent Medicare policies that have moved toward site-neutral payments for certain types of hospital outpatient clinic visits do not apply to commercial insurers, and that hospitals regularly charge commercial insurers facility fees for most outpatient services provided in hospital facilities. For example, one commercial insurance stakeholder reported that total prices paid in 2022 for services performed in hospital outpatient clinics were significantly higher than for the same service when performed in a physician office.[81] They reported that mammograms cost about one-third more and colonoscopies cost twice as much when performed in a hospital outpatient clinic compared to a physician’s office.

Representatives from a physician group identified another potential driver of increased spending resulting from physician vertical consolidation. They said that hospitals may expect primary care physicians to see more patients in shorter duration appointments, which could increase patient referrals for additional diagnostic testing or visits with specialists.

Insurers and Other Corporate Entities

|

Direct Contracting In response to concerns that consolidation of physician practices by hospitals and insurers has increased costs, some large employers that self-fund the insurance plans they purchase for their employees are utilizing a direct contracting model to provide health care to their employees. In this model, self-funded employers contract directly with physicians, health systems, or companies to provide physician and other health care services for their employees. Employers pay health care providers for the care of their employees rather than an insurance company. According to a stakeholder group representing large, self-insured employers that we spoke with, this approach enables these employers to potentially reduce costs by developing their own provider networks. For example, Google directly contracts with one such company to provide health care to its employees. Source: GAO analysis and interviews with stakeholders. | GAO‑25‑107450 |

We did not identify any studies that sufficiently examined the effects of physician practice consolidation by insurers, retail organizations, or other corporate entities on spending or prices.[82] Similarly, the RAND literature review did not find any such studies.[83]

Stakeholders we spoke with offered their perspectives on insurer-driven consolidation. For example, a stakeholder representing hospitals opined that insurers’ acquisition of physician practices may give them additional influence over how physicians document patient diagnoses and conditions, which can lead to higher payments for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries.[84] One stakeholder representing insurers similarly stated that insurer acquisitions of physician practices are part of their overall strategy for participation in the Medicare Advantage program, because it allows them to put in place practices to manage patient care and record relevant patient diagnoses. Stakeholders representing health insurers stated that when insurers acquire physician practices, they do so to help control medical spending, enhance care management, and increase quality.

Private Equity

Studies examining the spending and price effects of private equity ownership of and investment in physician practices were limited, but found some evidence of increases for commercial insurance. In general, these studies were focused on specific specialties and patient populations and were not applicable to all types of physicians or populations.

|

Effects of Physician Management Company Affiliation with Neonatal Intensive Care Units Physician management companies, which can have various ownership structures, have increasingly employed physicians, particularly those that practice in hospital-based specialties. A 2023 study analyzed two physician management companies—one publicly traded and one private-equity owned—that provide staffing for neonatal intensive care units and their effects on spending, utilization, and clinical outcomes. The study found that for these two physician management companies, affiliation with neonatal intensive care units was associated with a 56 percent increase in spending on physician services per stay compared to units without physician management company affiliation. The study did not find changes in length of stay or adverse clinical outcomes. Source: Yu, Jiani et al., “Physician Management Companies and Neonatology Prices, Utilization, and Clinical Outcomes,” Pediatrics, vol. 151, no. 4, (April 2023). | GAO‑25‑107450 |

Medicare. The two studies we reviewed that examined private equity investment in physician specialty practices found that spending in traditional Medicare did not change. For example, one study examining urology practices did not detect differences in spending in traditional Medicare for patients diagnosed with prostate cancer from 2014 through 2019 after their urologists’ practices were acquired by private equity firms.[85] Similarly, another study of ophthalmology practices did not find differences in spending in traditional Medicare after the practices were acquired by private equity firms in 2017 through 2018.[86]

Another study found that patients treated by physicians in four specialties who were affiliated with private equity-backed MSOs were most likely to receive selected services in a physician’s office or ambulatory surgery center in 2022 compared to patients treated by physicians affiliated with hospitals or who were independent.[87] For example, the study found that the probability of a Medicare patient having a colonoscopy with biopsy in a lower cost setting was 69 percent when their physician was private equity-affiliated, compared to 30 percent when their physician was hospital-affiliated.

Commercial insurance. Studies we reviewed found that private equity investment in physician specialty practices led to increases in commercial insurance spending for some of the specialties examined, but not others. The increases varied in magnitude by specialty and market concentration. One study found that in six out of 10 specialties examined from 2012 through 2021, commercial spending increased relative to practices that did not receive private equity investment.[88] It found that those relative increases ranged from 4 percent to 16 percent, depending on the specialty. For example, the study estimated commercial spending increased 16 percent in gastroenterology, 11 percent in obstetrics and gynecology, and 6 percent in primary care. It also found that three of the 10 specialties examined experienced larger increases in commercial spending in MSAs with a high concentration of private equity investment in that specialty.[89] For example, spending for consolidated practices relative to other practices without private equity investment increased 19 percent in obstetrics and gynecology, and 13 percent in primary care in concentrated markets.[90] Similarly, another study of gastroenterology practices found that commercial insurance spending increased after acquisitions by private equity firms.[91]

In addition, the studies found that private equity investment in certain specialties can lead to increases in the prices paid by commercial insurers, with variation in magnitude by specialty. For example, a previously mentioned study found that prices increased in eight of the 10 specialties studied after practices received private equity investment, with increases ranging from 4 percent to 14 percent.[92] That study estimated commercial prices increased 14 percent in gastroenterology, 8 percent in radiology, and 4 percent in dermatology relative to other practices in the same specialty without private equity investment. Similarly, three other studies found that commercial prices increased in some specialties, including gastroenterology, ophthalmology, and anesthesia, after practices were acquired by private equity firms or affiliated with private equity-backed physician management companies.[93]

Private equity stakeholders we spoke to offered an explanation for why private equity roll-ups of multiple physician practices can lead to higher prices: because private equity investment in physician practices can enable practices to secure better rates from insurers due to the increased bargaining power they attain after being acquired.[94] In addition, an actuary organization we spoke with noted that, while not unique to private equity roll-ups, newly acquired practices can often bill for services using the acquiring entity’s negotiated rates, which they said are typically higher than that of the acquired practice.

Effects of Physician Consolidation on Quality

We reviewed several studies that sufficiently examined the effects of hospital-physician consolidation on quality, which suggested no change or a decrease in the quality of care provided. We did not identify any studies that sufficiently examined the quality effects of physician consolidation with health insurers, corporate entities, or private equity firms. Stakeholders’ views on the potential effects of physician consolidation on quality varied. For example, while some stakeholders stated that consolidation by hospitals or private equity can provide physician practices with resources that can be applied to quality improvement activities, others expressed concern that the quality of those services may decline.

Hospital Systems

The studies we reviewed that examined the effects of hospital-physician consolidation on quality found either no change or a decrease in quality. Notably, the following studies relied on measures of quality that can be gleaned from claims data, which do not account for the full range of possible quality effects. For example:

· One study found no significant change in quality from 2010 through 2015 when physicians conducted certain elective procedures on patients on traditional Medicare at hospitals with which the physicians were consolidated, as measured by 90-day mortality, readmission, or complication rates for patients with sepsis or surgical site infections.[95]

· Another study found that hospital consolidation with primary care physicians in Massachusetts found no changes in several quality measures, such as reductions to preventable inpatient admissions or emergency visits for conditions such as asthma or diabetes from 2013 through 2017.[96]

· One study found that hospital-physician consolidation may lead to lower quality for some patients. The study examined adherence rates for medications to treat chronic conditions among patients in traditional Medicare whose primary care physicians converted from independent practices to hospital-consolidated practices from 2014 through 2017.[97] It found a modest decrease in medication adherence among older patients, non-white patients, and patients with more comorbidities, but no change in overall adherence rates. The authors posited that integration may reduce clinicians’ incentives to compete based on the quality of care delivered.

· One study that analyzed Medicare claims data from 2008 through 2015 found that after gastroenterologists consolidated with hospitals, patients undergoing colonoscopy were somewhat more likely to experience certain post-procedure complications such as bleeding, cardiac symptoms, and nonserious gastrointestinal symptoms.[98] The study did not observe changes in other measures. The study also found that consolidated physicians were less likely to use deep sedation during colonoscopy procedures, which the authors attributed to the financial incentives of consolidated practices. According to the study’s authors, the reduction in the use of deep sedation can partially explain the increase in some of the adverse patient health outcomes.[99]

The RAND literature review reported mixed results from nine studies published from 2004 through 2020 that examined the association between hospital-physician consolidation and quality of care: three found small quality improvements, three found mixed results, and three found no or insignificant effects.[100] In addition, the authors stated that there is an incomplete understanding of the effects of consolidation on quality of care because most studies assessing effects do not broadly assess the many dimensions of quality. They also noted that studies that assess impacts of physician consolidation on quality commonly rely on measures that are constructed using claims data; however, many aspects of clinical quality can only be assessed using clinical data contained in medical records.[101]

Stakeholders we interviewed offered different perspectives on the potential effects on the quality of care provided following hospital-physician consolidation. Some hospital stakeholders we spoke with said that hospital employment of physicians has the potential to improve quality by, for example, streamlining quality initiatives across the system, standardizing clinical operations, and coordinating a patient’s care across the system. A physician group we spoke with said that because hospitals can charge facility fees for physician services, hospital-based physician practices may be better able to invest in new equipment and technology than can independent practices. In contrast, as previously noted, representatives from a physician group said that hospitals may expect physicians to see more patients, which can lead to shorter duration appointments where a physician may be unable to fully address a patient’s needs.

Insurers and Other Corporate Entities

We did not identify any studies that sufficiently examined the causal effects of physician acquisitions by insurers and other corporate entities on quality. Similarly, the RAND literature review did not find any studies on the effects of consolidation of physicians with insurers or other corporate entities on quality.[102]

Private Equity

We did not identify any studies that sufficiently examined the causal effects of private equity investment on quality.[103] Similarly, the RAND literature review did not identify any such studies.[104]

Stakeholders representing private equity firms and independent physicians supported by them provided examples of how private equity investment can give physician practices access to resources that have the potential to improve quality.[105] For example, a physician reported that their independent ophthalmology practice partnered with a private equity-backed MSO and as a result, gained access to the MSO’s innovation center that monitors patient outcomes and electronic health records to develop best practices to improve patient care. Another physician reported that investment from a private equity-backed MSO allowed their urology practice to purchase multimillion dollar equipment needed to deliver less invasive treatments. Private equity stakeholders told us that many private equity firms track quality metrics to help improve patient outcomes and satisfaction.

Conversely, a stakeholder association we interviewed representing physicians and some public commenters who responded to the 2024 tri-agency request for information on health care consolidation noted quality concerns at private equity-owned emergency medicine practices. Specifically, this stakeholder stated that their members reported in an internal survey that private equity-backed physician staffing companies may staff fewer physicians and more nurse practitioners and physician assistants in emergency rooms, which they believed could create a potential for patient harm because, among other factors, those clinicians have less education and training than physicians.[106]

Effects of Physician Consolidation on Access

We did not identify any studies that examined the effect of physician consolidation on access to care by any acquiring entity type that met our methodological standards. Similarly, the RAND literature review determined that there was insufficient evidence on the effect of physician consolidation on access.[107] Stakeholders’ perspectives on the effects of physician consolidation on access aligned with their roles and members’ interests.

Hospital Systems

We did not identify any studies that sufficiently examined the causal effects of hospital-physician consolidation on patient access to care. MedPAC reported in 2024 that most physicians continue to accept new Medicare beneficiaries, but that access to physician services in traditional Medicare could eventually be affected by increases in commercial prices resulting from consolidation.[108]

Stakeholders we spoke with had mixed views about the potential effects on access, with hospital stakeholders having favorable views and physician stakeholders having some concerns. Hospital stakeholders said that hospital-physician consolidation may improve access because physicians in a hospital system are better able to coordinate any necessary care, particularly following a patient’s discharge. They said that acquiring physician practices can improve the hospital system’s ability to ensure access to necessary patient care through the transfer of patients within a hospital system, such as to a post-acute care facility.

Hospital stakeholders also told us that preserving access to services is a major reason why hospitals acquire physician practices. They told us that absent acquisition or affiliation with a hospital, some physicians may close their practices or leave the medical field entirely and that hospitals may acquire these practices to prevent their loss. In addition, representatives from one group said it is not uncommon for physicians to approach their local hospitals about consolidation when they are struggling to maintain their private practice. Finally, these stakeholders told us that hospital-physician consolidation could result in increased access to care for uninsured patients because physicians may be more willing to provide uncompensated care when they are part of a health system that provides financial support.

However, physician stakeholders we spoke with said that hospital-physician consolidation may impede access to care. Physicians from one group said it may be difficult to get same day appointments with hospital-based physicians, and physicians from two other groups said that wait times for available appointments can sometimes be shorter with independent practices. Physician stakeholders also said hospital-based physicians may be pressured to only refer their patients to specialists that are part of the same hospital system, which could limit a patient’s ability to choose among all their options for follow-up care.

Insurers and Other Corporate Entities

We did not identify any studies that sufficiently examined the causal effects of physician practice consolidation by insurers, retail organizations, or other corporate entities on access, nor did RAND.

Private Equity

We did not identify any studies that examined the causal effects of private equity investment on access.[109] However, stakeholders representing private equity firms and independent physicians supported by private equity described how patient access to care could improve after private equity investment in physician practices. For example, a physician reported that partnering with a private equity-backed MSO helped their independent dermatology practice expand insurance coverage to see more patients with Medicaid and Medicare Advantage. Another physician told us that private equity investment allowed their practice to hire more providers and expand access to fertility services in rural areas. In addition, private equity stakeholders told us that private equity investment has the potential to improve patient access to appointments by implementing better scheduling tools and centralized call centers.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to HHS, DOJ, and FTC for review and comment. Each provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committees, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Attorney General, the Chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at http://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact me at GordonLV@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix I.

Leslie V. Gordon

Director, Health Care

GAO Contact

Leslie V. Gordon at GordonLV@gao.gov.

Staff Acknowledgments

In addition to the contact named above, Shannon Legeer (Assistant Director), Laura Tabellion (Analyst-in-Charge), Kevin Dong, Sean Miskell, Eric Peterson, Drew Long, Seyda Wentworth, Leia Dickerson, Emei Li, and Jennifer Whitworth made key contributions to this report.

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses, recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

Obtaining Copies of GAO Reports and Testimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is through our website. Each weekday afternoon, GAO posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. You can also subscribe to GAO’s email updates to receive notification of newly posted products.

Order by Phone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077,

or

TDD (202) 512-2537.