CONSUMER PRICES

Trends and Policy Options Related to Shrinking Product Sizes

Report to the

Ranking Member, Subcommittee on Education and the American Family, Committee on

Health, Education, Labor and Pensions,

U.S. Senate

United States Government Accountability Office

A report to the Ranking Member, Subcommittee on Education and the American Family, Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, U.S. Senate

For more information, contact: Alicia Puente Cackley at cackleya@gao.gov or Michael Hoffman at hoffmanme@gao.gov.

What GAO Found

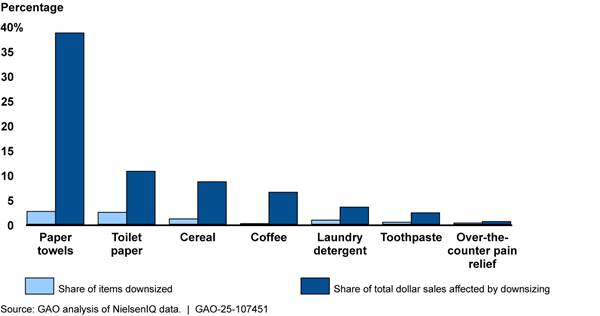

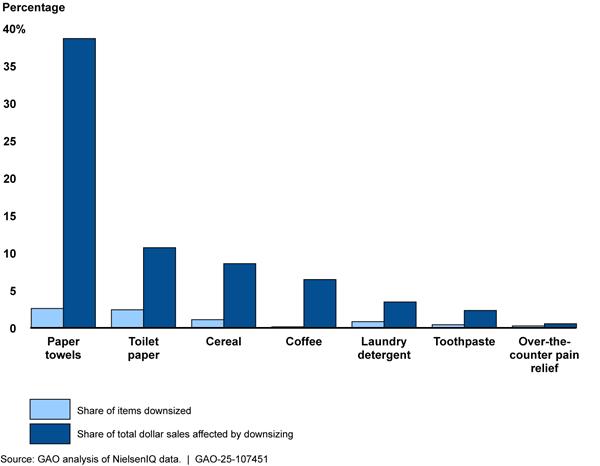

Product downsizing, or “shrinkflation,” occurs when an item’s quantity decreases without a commensurate price drop. This raises the per-unit price and contributes to inflation. GAO’s analysis of 2019–2024 Bureau of Labor Statistics data found that downsizing accounted for less than 1/10 of a percentage point of the 34.5 percent increase in overall consumer prices during this period. This is because downsized products were a small share of all products tracked in inflation measures. However, in the top five product categories experiencing downsizing, the contribution of size changes to inflation ranged from 1.6 percentage points for cereal to 3.0 percentage points for household paper products (e.g., paper towels). Separately, GAO’s analysis of 2021–2023 consumer purchase data for thousands of items across seven product categories found that while less than 5 percent of items in each category were downsized, those items made up a larger share of total dollar sales. For example, in the cereal category, 1.1 percent of items, representing 8.6 percent of sales, were downsized.

Share of Items and Sales Affected by Downsizing for

Selected Product Categories, 2021–2023

Research suggests that consumers tend to be less responsive to downsizing than to equivalent price increases and that downsizing has limited effects on purchase behavior. This limited responsiveness could stem from lack of awareness of subtle packaging changes, infrequent purchases, or strong consumer preferences for certain products and brands.

Several policy options that aim to increase transparency around downsizing also present implementation challenges. For example, some countries require manufacturers or retailers to disclose downsized items, but regulators may face difficulties defining downsizing and identifying noncompliance. In addition, a federal unit price labeling policy could help consumers compare prices using consistent unit price displays, even when downsizing goes unnoticed. However, enforcement of such a policy may rely on U.S. states and would need to consider states’ potential roles and resources.

Why GAO Did This Study

In 2021 and 2022, the U.S. experienced its highest inflation rate since 2011. Amid rising prices for everyday goods, policymakers have raised questions about product downsizing and its effects on households.

GAO was asked to review issues related to product downsizing. This report examines (1) trends in product downsizing, (2) factors affecting consumer response to product size changes, and (3) advantages and disadvantages of policy options for addressing concerns related to product downsizing.

GAO analyzed Bureau of Labor Statistics data on the frequency of product size changes and their impact on inflation. In addition, GAO analyzed retail scanner data—aggregated consumer purchase data—for all products within seven high-spending categories to determine the extent of size changes and their price effects. GAO reviewed studies on how consumers respond to size changes and interviewed or obtained written responses from officials from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the Federal Trade Commission, two state agencies, nine foreign countries, three consumer groups, and three industry groups (representing manufacturers, wholesalers, and retailers), as well as eight academic researchers.

Abbreviations

|

BLS |

Bureau of Labor Statistics |

|

CPI CPI-U DOJ |

Consumer Price Index Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers Department of Justice |

|

FDA |

Food and Drug Administration |

|

FTC |

Federal Trade Commission |

|

NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

|

UPC R-CPI-SC |

Universal Product Code CPI size change research index |

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

July 31, 2025

The Honorable Lisa Blunt Rochester

Ranking Member

Subcommittee on Education and the American Family

Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions

United States Senate

Dear Senator Blunt Rochester,

In 2021, the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by 4.7 percent—the first time the average annual inflation rate exceeded 3 percent since 2011, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).[1] Inflation remained elevated, reaching 8.0 percent in 2022, before declining to 4.1 percent in 2023 and 2.9 percent in 2024.[2] Amid rising prices, some news media called attention to product downsizing, commonly known as “shrinkflation.” We define product downsizing as a reduction in the quantity of an item without a commensurate decrease in price, resulting in a higher price per unit of volume, weight, or count.[3]

Some policymakers have expressed concern that companies use subtle package size changes to disguise price increases. Manufacturers, however, have argued that product downsizing can benefit consumers by keeping the total price of an item stable when costs rise, albeit for smaller quantities.

You asked us to review issues related to product downsizing. This report examines (1) trends in product downsizing and upsizing, (2) factors affecting how consumers respond to product downsizing in their purchase decisions, and (3) the advantages and disadvantages of policy options to address concerns related to product downsizing.[4]

For our first objective, we analyzed available BLS data from 2015 through 2024 on the frequency of downsizing and upsizing. Additionally, we analyzed available BLS research indexes from December 2014 through December 2024 that estimated the effect of downsizing and upsizing on the CPI.[5] We also analyzed weekly retail scanner data—aggregated data on consumer purchases—from NielsenIQ from 2021 through 2023 to identify trends in product downsizing and upsizing across seven products: coffee, cereal, paper towels, toilet paper, laundry detergent, toothpaste, and pain relievers.[6] We selected these seven products on the basis of criteria that included high sales and the potential to undergo downsizing or upsizing.

To assess the reliability of the BLS and NielsenIQ data, we reviewed the data and their related documentation and interviewed officials from both organizations about their methods. We determined that both data sources were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing trends in product downsizing and upsizing.

We also conducted a literature review to identify relevant studies. Using keyword searches of scholarly databases, including Scopus and EconLit, we searched research published from 2004 through 2024. We identified and reviewed two methodologically sound studies that analyzed trends in downsizing and upsizing.

For our second objective, we identified and reviewed 17 methodologically sound studies that included analysis of consumer responses to product downsizing. We identified these studies using the same process described above. We also interviewed a nongeneralizable selection of representatives of three consumer groups and three industry groups, as well as seven academics, about consumer responses to downsizing. We selected these parties for their experience and expertise related to product downsizing or upsizing.

For our third objective, we first identified current or proposed policy options to address downsizing through a search of news articles and legal material from 2014 through 2024. Using the same literature review process described above, we then identified eight methodologically sound studies that analyzed one or more of the policy options and reviewed these studies. We also interviewed or obtained written responses from governmental agencies in nine countries about these options, including their advantages and disadvantages. We selected the countries because they had adopted or proposed one or more of the policy options and reflected geographic diversity, among other criteria.

We discussed the advantages and disadvantages of the policy options with the academics, consumer groups, and industry groups noted above. Regarding unit pricing policies, we requested interviews with relevant agencies in five states, to include states with and without unit pricing policies, states in different U.S. regions, and states with different population sizes. Three states did not respond to our request. We interviewed or obtained written responses from two agencies responsible for unit pricing policies in two states, New Jersey and Arkansas. Finally, we interviewed officials from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) about policy options.

Appendix I provides further information on our scope and methodology. Appendix II provides more information about our analysis of BLS data, and appendix III provides information about our analysis of retail scanner data from NielsenIQ.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Background

Product Downsizing in the Marketplace

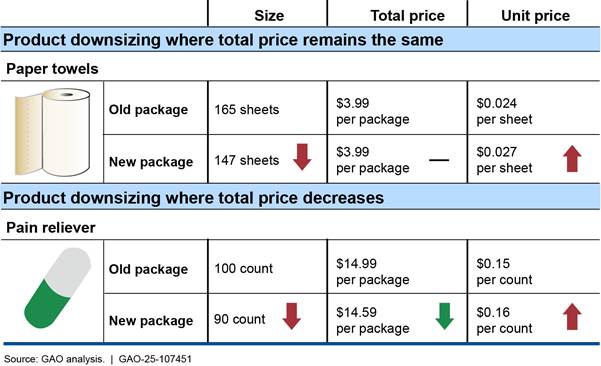

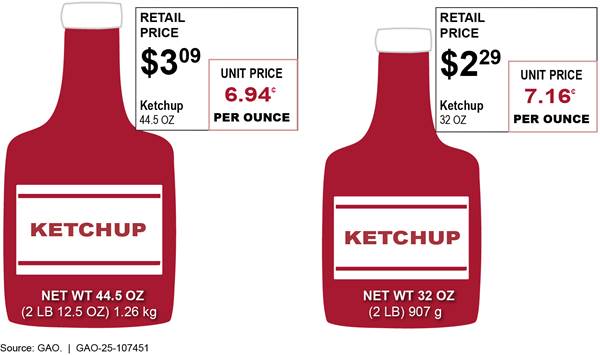

Manufacturers may downsize an item as an alternative to increasing its total price to address increases in the cost of production inputs, to increase profit, or for other reasons. When this occurs, the total price may increase, stay the same, or decrease, but the unit price—price per unit of volume, weight, or count—rises (see fig. 1).[7] Similarly, manufacturers may upsize an item—that is, increase its package size and quantity without a commensurate price increase—as an alternative to lowering the total price.

In deciding whether to downsize products, manufacturers consider factors that can affect their profits. For example, raising prices or reducing package sizes can reduce consumer demand. However, a manufacturer may determine that increasing the unit price through downsizing will have less effect on demand than raising the price without changing the size, especially if consumers do not notice the size or unit price change. Manufacturers may also consider how easily consumers can substitute competing products and how competitors might respond with their own price and size adjustments.

When downsizing occurs, in addition to making the package size smaller, manufacturers may also modify package characteristics such as labeling, shape, colors, or materials. In some cases, the changes are minimal, resulting in packaging similar to the original (see fig. 2).[8]

In other cases, packaging changes are more noticeable (see fig. 3).

Relevant Federal Laws and Regulations

Various federal laws and regulations establish requirements for the labeling and packaging of consumer products.[9] For example, under Fair Packaging and Labeling Act regulations, products must have labels that accurately state the net quantity of contents, such as the net weight or numerical count of items inside the packaging.[10] Additionally, the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act prohibits misbranded products in interstate commerce, including those with misleading containers or labels.[11]

The Fair Packaging and Labeling Act and Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act do not expressly prohibit product downsizing. However, the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act and related regulations do restrict nonfunctional slack-fill (that is, empty space in a package that does not serve specified purposes, such as protection of the contents).[12] Nonfunctional slack-fill can occur in conjunction with product downsizing if a company keeps the original packaging but reduces the product quantity, thereby increasing the empty space inside, without a commensurate decrease in unit price. A food container with nonfunctional slack-fill is considered misleading—and therefore prohibited—if the consumer cannot fully view the contents.[13]

The Federal Trade Commission Act makes it unlawful to engage in unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce.[14] The act authorizes FTC to prescribe rules that define specific acts or practices as unfair or deceptive.[15] However, prior to commencing such a rulemaking, FTC must have reason to believe that the acts or practices in question are prevalent.[16] According to FTC officials, the agency has not issued rules defining product downsizing as an unfair or deceptive act or practice under the act.

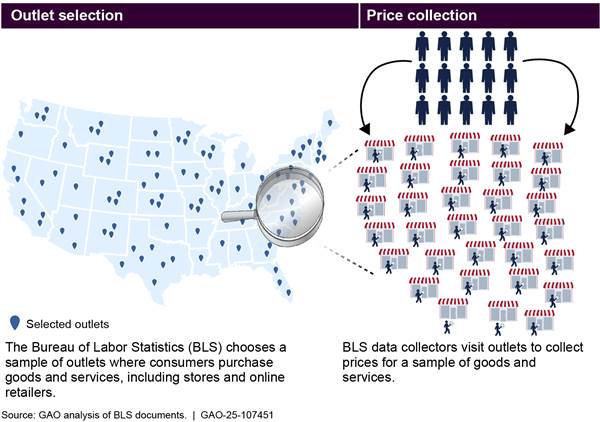

Capturing Size Changes in the Consumer Price Index

BLS produces consumer price indexes for various populations, such as for elderly and urban consumers, to estimate price inflation. In this report, we use “CPI” to refer to the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers. This index represents inflation for the goods and services purchased by about 93 percent of the U.S. population.[17] To create the CPI, BLS chooses a sample of outlets, such as stores or online retailers, where the CPI population shops. BLS data collectors visit these outlets to collect prices for a sample of goods and services included in the CPI (see fig. 4).

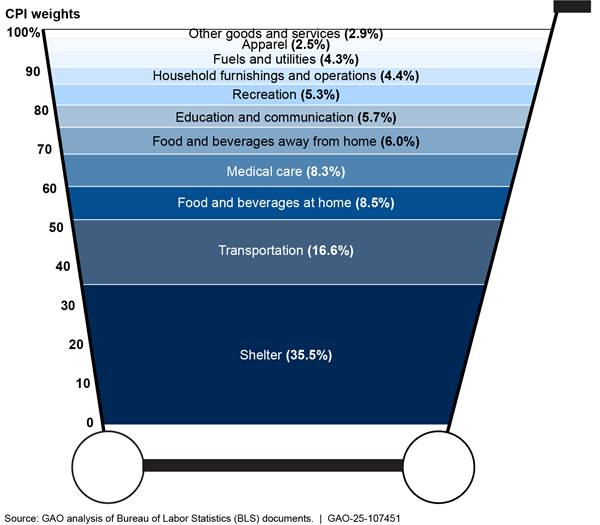

BLS then develops basic indexes capturing average price changes within 7,776 unique combinations of geographic areas and goods and services.[18] Next, it aggregates these basic indexes into a single index by applying a set of expenditure weights to the aggregated index, which reflects the proportion of consumer spending on each good and service (see fig. 5).[19]

Note: The expenditure weights reflect the proportion of consumer spending on each good and service. BLS categorizes beverages separately from food. The expenditure weights for beverages away from home and at home are both 0.4 percent.

BLS directs the data collectors to identify if an item included in the CPI sample has been downsized or upsized. BLS uses this information to ensure that CPI inflation properly accounts for changes in product sizes.[20] BLS has developed research indexes to estimate the effect of product size changes on inflation for some broad categories, such as “food-at-home,” “household paper products,” and “personal care products,” as well as some narrower categories, such as “breakfast cereal” and “baby food and formula.”

Product Downsizing Contributed Little to Overall Inflation but Has Affected Certain Products More Than Others

Product Downsizing Is a Longstanding Practice but Has Little Overall Effect on Inflation

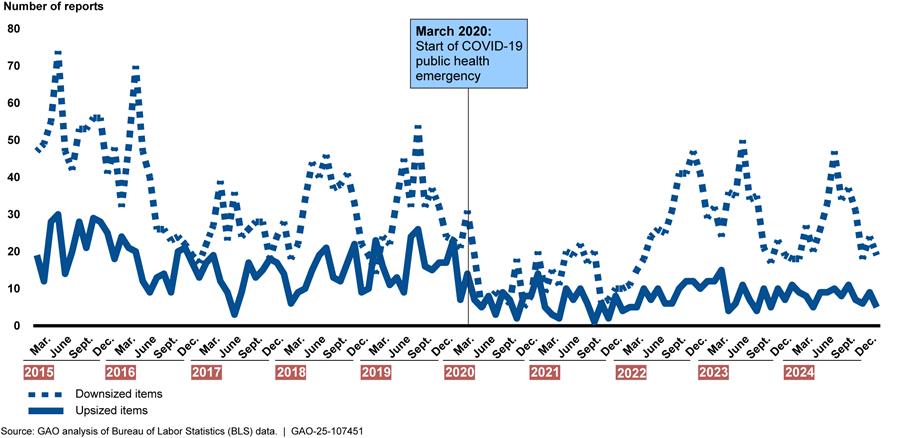

Product downsizing and upsizing are longstanding practices that have varied in frequency over time, according to our analysis of BLS data and related literature. BLS data indicate that downsizing and upsizing in products covered by the CPI occurred from 2015 through 2024, fluctuating throughout the period.[21] Overall, downsizing was more common than upsizing, with three times as many reports of downsized items as upsized items from 2021 through 2024. Our analysis indicated that downsizing occurred most frequently in 2015 and was above average in 2016, 2018, and 2019 (see fig. 6).[22] Both downsizing and upsizing were lowest in 2020 and 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic.[23] Total reports of downsized items increased starting in early 2022, amid exceptionally high inflation, while the total reports of upsized items remained low.[24]

Figure 6: Reports of Downsized and Upsized Items in the BLS Consumer Price Index Sample, by Month, 2015–2024

Two studies similarly found that downsizing and upsizing are longstanding practices, occurring over the periods they examined, dating back to 2006, according to their analyses of Nielsen retail scanner data.[25] One study, which analyzed product size changes across 91 product categories sold nationally from 2010 to 2020, found that downsizing peaked in 2012 and was significantly more common than product upsizing across nearly all products examined.[26]

The impact of product size changes on overall inflation has been relatively small, according to our analysis of BLS data from 2019 through 2024.[27] Our analysis, which is based on a modified calculation of the CPI, found that while CPI prices increased by 34.5 percent, product downsizing contributed to 0.06 of a percentage point of this increase over the 5-year period.[28] Thus, the impact of product downsizing on overall inflation was minimal, with an average annual effect of about 0.01 of a percentage point per year.[29] This minimal impact reflects that the products experiencing downsizing and upsizing make up a small share of the CPI sample. The CPI includes several high-expenditure items, including housing, gas and utilities, college tuition, and medical expenses, all of which are not subject to product size changes.

Product Downsizing Has Affected Inflation More for Certain Products

While the overall effect of product downsizing on inflation was small, the impact was more notable in product categories where downsizing and upsizing are feasible, especially among food products.[30] For example, the contribution of product size changes to CPI inflation for the top five product categories that experienced downsizing ranged from 1.6 percentage points for cereal to 3.0 percentage points for household paper products, according to our analysis of BLS data from 2019 through 2024.[31] However, some food products, such as milk and fruits, were generally not downsized during this period. Similarly, one study found frequent product size changes in categories like candy and snacks from 2010 to 2020, while products typically sold by specific volumes, such as flour and milk, rarely changed size.[32]

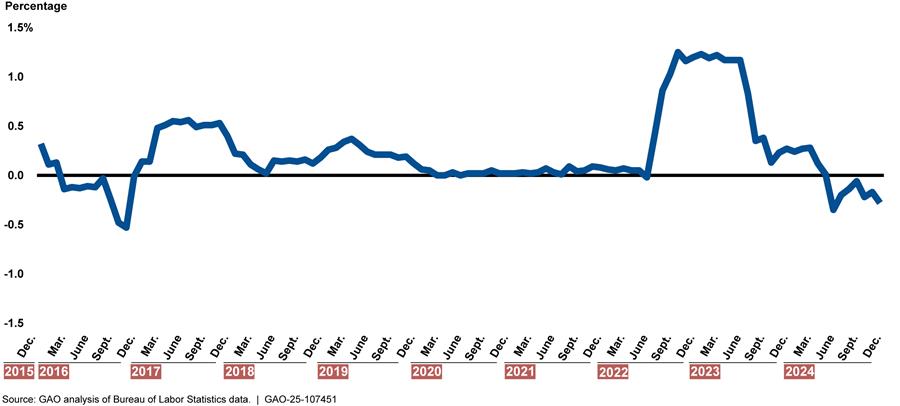

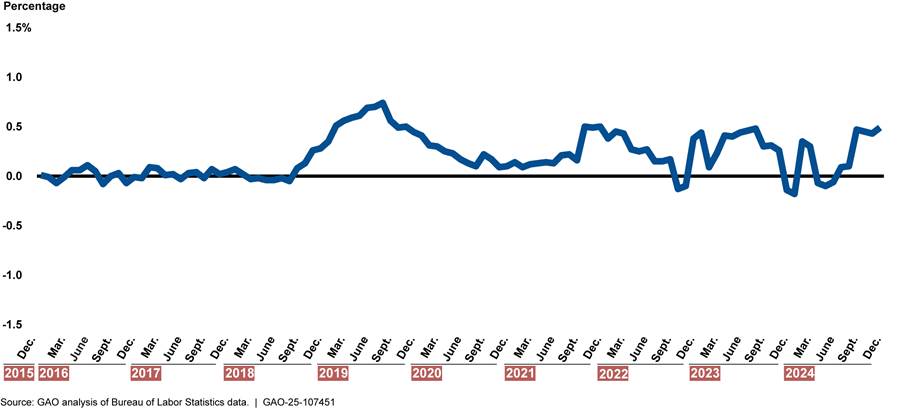

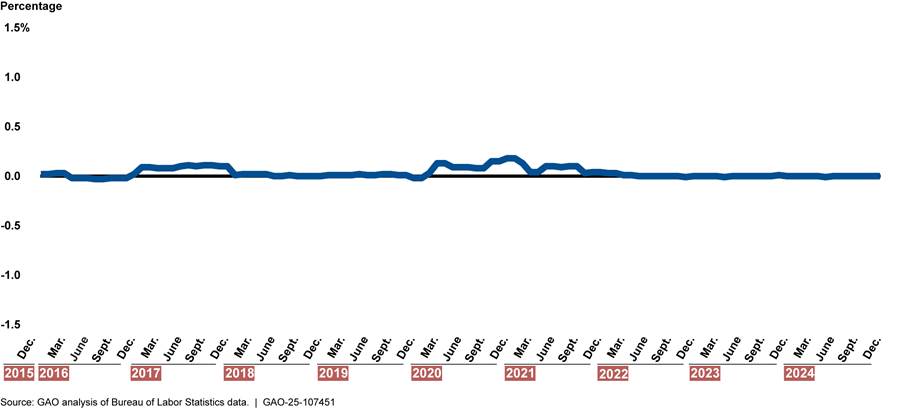

Additionally, certain product categories experienced more pronounced product downsizing during 2022 when inflation was exceptionally high, according to our analysis of BLS data. For example, before August 2022, downsizing had a minimal effect on coffee’s CPI inflation, with price changes attributable to product size changes near zero from 2020 through early 2022 (see fig. 7). However, from August 2022 through June 2023, downsizing notably increased per-unit coffee prices in the CPI. Toward the end of 2023 and 2024, the effect of product size changes on per-unit coffee prices was again near zero.[33]

Figure 7: Impact of Size Changes on Per-Unit Coffee Prices in the Consumer Price Index (CPI), Dec. 2015–Dec. 2024

Note: Percentage differences above 0.0 indicate price increases from downsizing. Percentage differences below 0.0 indicate price decreases from upsizing. The line indicates the percentage difference between the 12-month percent change in the CPI production series and the 12-month percent change in the CPI size change research series. The CPI research series removes size changes from the production series, so differences between the two estimate the price increase or decrease due to changing sizes. One limitation of the research indexes is that they are calculated outside of the official production system and are at greater risk of calculation errors than the CPI production indexes, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For more details, see app. II.

In Selected Product Categories, Higher-Selling Items Were More Likely to Be Downsized

Our analysis of NielsenIQ data from 2021 through 2023 for thousands of items in seven selected product categories found that less than 5 percent of items in each product category were downsized, with fewer, if any, upsized.[34] However, the downsized items accounted for a larger share of total dollar sales in each category, suggesting that popular or higher-selling items were more likely to be downsized. For example, in the cereal category, about 1.1 percent (60 of 5,591 items) of all cereal items sold from 2021 through 2023 were downsized, but those items represented 8.6 percent of total dollar sales over the period.[35]

The extent of downsizing varied across product categories. Our analysis of NielsenIQ data found that downsized products ranged from 0.5 percent of dollar sales in the pain relief product category to 38.6 percent in paper towels (see fig. 8). This indicates that downsized paper towel items were more widely purchased than downsized pain relief items.

Our analysis of BLS data from 2019 through 2024 identified a similar pattern: product size changes contributed just 0.32 percent to inflation in over-the-counter drugs, including pain relief, compared with 3.0 percent for household paper products, which included paper towels and toilet paper. These findings are consistent with the findings in NielsenIQ data that the extent of downsizing was small in the over-the-counter pain relief product category and relatively high in the toilet paper and paper towel product categories.

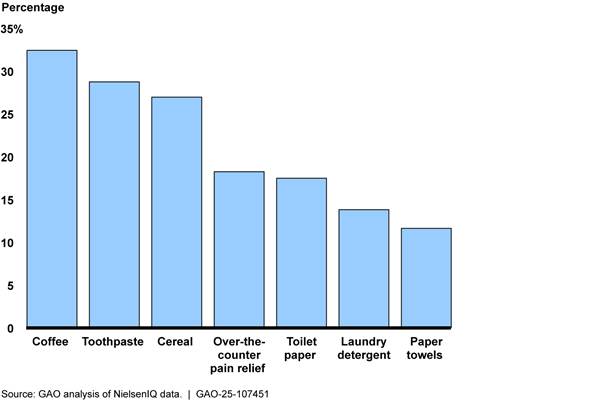

Downsizing increased per-unit prices to varying degrees among the seven product categories we examined, according to our analysis of NielsenIQ data. The average per-unit price increase among downsized products ranged from 11.6 percent in the paper towel product category to 32.4 percent in the coffee product category (see fig. 9). The per-unit price increase that resulted from the downsizing was highest for coffee among our seven selected product categories. This was consistent with our analysis of BLS data, which found that product size changes contributed 1.4 percentage points to overall coffee price inflation from 2019 through 2024. This price impact was driven largely by downsizing in 2022 and 2023.

The effect on consumers of per-unit price increases from downsizing depends on how much of the downsized product consumers buy. If consumers continue purchasing a downsized product to the same extent that they did before the product was downsized, the price increases would have a larger effect. Two studies we reviewed found that consumer responses to size changes varied by product type. Both studies, for example, found that product size changes had a small effect on coffee sales volume.[36] Our analysis of NielsenIQ data similarly found that for most of the downsized coffee items we identified, a similar number of units were sold after the downsizing occurred.[37] Moreover, we found that the total dollar sales of the products generally were similar or higher after they were downsized for nearly all items.

The extent of upsizing also varied by product category, according to our analysis of NielsenIQ data. We found no instances of upsizing in the laundry detergent or over-the-counter pain relief product categories from 2021 to 2023. We identified nine items upsized in the toilet paper product category, which was the highest among the seven selected product categories. In the other four categories, fewer than five items were upsized in each. For the toothpaste product category, where downsizing and upsizing were both limited, 0.4 percent of items were downsized and 0.1 percent of items were upsized. The downsized products accounted for 2.3 percent of total dollar sales, compared with 0.8 percent for upsized items. This was consistent with our analysis of BLS data, which found that both downsizing and upsizing affected the personal care product CPI, which includes toothpaste, during the period 2021–2023, but the size of the effects was generally small.[38]

Consumers’ Response to Product Downsizing Is Influenced by Product Characteristics, Preferences, and Other Factors

Consumers Are Generally Less Responsive to Product Downsizing Than to Price Increases

Six studies we reviewed found that consumers were less likely to change their purchases in response to product downsizing than to an equivalent total price increase.[39] Two of the studies, which examined broad product categories, found that downsizing rarely caused a decline in the number of packages sold.[40] One study found that a 1 percent increase in the total price of an item led to a 1.95 percent decline in sales on average, whereas a 1 percent size decrease led to a slight increase (0.76 percent) in the number of packages sold.[41] The other study similarly found that about 93 percent of the downsized items had no statistically significant decline in the number of packages sold, and some saw increases.[42] In some cases, higher package sales after downsizing could indicate that consumers bought more units to compensate for the reduced quantity per package.

The other four studies focused on specific products: black pepper tins, milk, ice cream, and cereal. These studies are not generalizable to all products. However, they consistently found that consumers were about two to five times more responsive to total price increases than to product downsizing, where both changes resulted in the same unit price change.[43] An additional study, which analyzed survey responses, found that when faced with cost increases, consumers preferred reductions in quantity over price increases or quality reductions for certain products.[44]

Product Characteristics, Preferences, and Household Income Affected Consumers’ Response to Downsizing

Many consumers may not change their purchase behavior in response to product downsizing because they are unaware of the change, because the product’s attributes still align more with a consumer’s preference than those of the potential substitute, or for other reasons. Consumer awareness may be limited because downsizing is not typically disclosed on packaging, and consumers may not remember unit prices or quantity for every prior product they buy. In addition, certain product characteristics can make downsizing harder to detect. Even when consumers do notice downsizing, they may continue purchasing the product due to limited alternatives, habits, or preferences.

Factors That Limit Consumer Awareness

Three academics and a consumer group representative told us it may be difficult for consumers to recognize downsizing. Studies we reviewed and stakeholders we interviewed identified factors that make recognizing downsizing more difficult.

· Subtle packaging changes can obscure downsizing. Three academics and one state regulator said subtle changes to an item’s packaging, such as a deeper indentation in the bottom of a jar or small changes to multiple dimensions of a package, can make product downsizing difficult to detect. Similarly, one study found that consumers understate the extent of product downsizing, especially when multiple dimensions of the product change.[45]

· Consumers have limited recall of size or unit price, especially for less frequent purchases. A study of black pepper tins in the U.S. market—purchased less than once a year on average—found that half of consumers failed to notice any given size adjustment in five different packages made by one large producer.[46] Another study found that consumers were more responsive to quantity reductions in jam, a household staple, than in boxed chocolate, a discretionary item.[47] Similarly, four academics told us that consumers are more aware of downsizing in products that typically come in a certain size or that they use regularly. Additionally, two academics said consumers have more limited recall of packaging sizes or unit prices compared with the total price.

Consumers’ Habits and Preferences

Even consumers who recognize downsizing may keep buying the item due to habits, preferences, or limited alternatives. Five academics we interviewed said consumers may place a high value on certain product characteristics, such as taste and health attributes and package size. In particular, two academics noted that a downsized package may still best fit a consumer’s size preference, compared with other available options. This is in part because manufacturers may design size changes to cater to consumer preferences. For example, representatives of an industry association noted that companies conduct extensive surveys on consumers’ willingness to pay to guide decisions on resizing versus price increases. One study of cereal purchases in a large U.S. metropolitan area showed that when a manufacturer downsized certain cereals, consumers mostly did not switch to alternatives—likely because the new sizes aligned more closely to their preferred package size.[48] Even if downsizing is not ideal, consumers are habitual shoppers and may continue buying the same product out of brand loyalty, according to one academic.[49]

Household Income

Household income level can be associated with a consumer’s response to product downsizing. Three studies found that higher-income households were less responsive to downsizing than lower-income households.[50] Other studies on household income suggest that this may be because higher-income households spend a smaller portion of their income on household essentials, such as food-at-home, housekeeping products, and personal care products. As a result, higher-income households are less sensitive to unit price changes.[51]

Policy Options Could Increase Transparency Around Downsizing but Pose Challenges

We identified several policy options aimed at addressing concerns related to product downsizing. Each presents potential advantages and disadvantages relative to the status quo. These options include

· requiring labels on the package or other disclosures that indicate when downsizing has occurred,

· implementing broader and more consistent unit price labeling across states to help consumers compare prices per quantity in retail outlets,

· using retail scanner data to ensure that consumer price indexes more comprehensively and accurately reflect the frequency and magnitude of product size changes,

· educating consumers about product downsizing, and

· prohibiting certain product downsizing practices deemed unfair or deceptive.

Labeling Requirements for Downsizing

Labeling products that have been downsized can improve price transparency—a key concern related to downsizing. Consumers may not notice when a product’s size has been reduced, leading them to pay a higher unit price (such as price per volume) without realizing it. This could inhibit consumers’ ability to make fully informed purchase decisions or to choose a different product, size, or brand.

France and South Korea are among the countries that have enacted measures requiring labels or other disclosures identifying downsized items, according to literature we reviewed and foreign officials we contacted.[52] These requirements have important differences. For example, France requires certain retailers to identify downsized items by displaying a specific notice on or near the product.[53] French officials stated that the requirement is imposed on retailers in part because the retailers determine final prices. South Korea places the responsibility on manufacturers, who must notify consumers through the product’s packaging, the manufacturer’s website, or at the place of sale (including online sales pages). South Korean officials explained that providing these three options for notifying consumers allows manufacturers to choose the option they deem most appropriate.

These requirements also differ in scope. For example, France’s requirement applies to prepackaged consumer products—food and nonfood products—when the quantity is reduced and the unit price increases.[54] French officials also explained that the requirement is limited to stores that are predominantly food stores with a sales area of more than 400 square meters (about 4,300 square feet). South Korea’s requirement applies to a designated list of household items and processed foods—such as cooking oil, ice cream, and jam—when content is reduced, according to literature we reviewed.[55] However, the requirement does not apply if the unit price remains unchanged or the rate of reduction is less than 5 percent, according to South Korean officials.

Labeling policies can increase price transparency, but challenges in identifying noncompliance could limit the policies’ effectiveness. French officials told us that differentiating between a downsized item and a new product, such as one that has undergone ingredient changes, is a challenge.[56] They also said that they do not receive downsizing information from retailers or manufacturers, and that enforcement relies largely on consumer reports. South Korean officials stated that major distributors and food manufacturers report quarterly information relevant to downsizing under a voluntary agreement. Officials also used information from a consumer hotline for reporting downsizing. However, as noted previously, consumers may be unaware of product downsizing, limiting their ability to identify and report noncompliance.

Consumers also may not fully take advantage of downsizing labels when making purchase decisions. Three academics said downsizing labeling adds to already substantial information consumers must process in making purchase decisions. Two other academics also cautioned that such labels could divert attention from other important but unlabeled product changes, such as ingredient modifications.

In implementing or determining the appropriateness of a product downsizing labeling policy, policymakers might weigh the benefits of transparency against the burdens of implementation, among other factors. For example, French officials told us that the downsizing notice must be displayed for 2 months after a retailer places the product on the shelf. They considered this enough time to inform consumers of the change while also limiting retailer burden. South Korean officials told us they require manufacturers to notify consumers of product downsizing for 3 months to allow sufficient time to inform consumers. Additionally, they said the estimated time between customer repurchases of the same item was approximately 3 months.

The requirements in France and South Korea went into effect in July 2024 and August 2024, respectively, according to foreign officials. In November 2024, French officials told us they had not observed many instances of downsizing notices at retailers, but it was unclear if that was due to a reduction in downsizing. South Korean officials told us that there had been no enforcement activities due to noncompliance as of November 2024.

Uniform Unit Pricing

According to NIST, 16 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories had unit pricing laws or regulations, as of November 2024.[57] In states and territories without such laws or regulations, many retailers provide unit pricing voluntarily. NIST has published a handbook containing the Uniform Unit Pricing Regulation, a model regulation that aims to encourage wide adoption and uniformity of unit pricing regulations across U.S. jurisdictions.[58] According to NIST, several states and one territory had adopted the model regulation or a prior version of it, as of November 2024.[59] The Uniform Unit Pricing Regulation does not expressly require retailers to provide unit price information but imposes requirements on those who choose to do so.

Generally, unit pricing displays in the U.S. provide information on the cost per unit of measure, such as the price per unit of weight or volume (see fig. 10).

While unit pricing alone does not directly disclose that product downsizing has occurred, it can help consumers compare prices and make informed decisions, even when they are unaware that an item’s size has changed. For example, one study examining canned tuna purchases found that consumers in U.S. states with unit pricing regulations reduced their purchases of downsized products by 30 to 84 percent more compared with those in states without such regulations.[60] More broadly, some research has found that unit price labels may lead consumers to choose items with lower unit prices.[61]

A key consideration for a unit pricing policy is the uniformity of labels. The Australian government, for example, has announced it will consult on ways to help consumers respond more effectively to product downsizing.[62] Initiatives include addressing inconsistent use of unit price measures for similar products and enhancing the readability and visibility of unit price labels in supermarkets. The Australian government is also examining ways to improve consistency in units of measurements across supermarkets to facilitate comparison shopping online.

Similar issues exist in the U.S. Technical advisors from NIST’s Office of Weights and Measures said the lack of uniformity in unit pricing across and within stores makes it difficult for consumers to compare prices (see fig. 11). They also noted issues such as small font sizes and inconsistent placement of unit prices on the labels that make unit prices hard to read or identify. To address these challenges, NIST has published a best practices guide for retailers, aimed at improving the accuracy, usability, and uniformity of unit pricing across states.[63] One consumer organization said a federal unit price labeling law could further help by establishing uniform standards, such as using the same units of measure for similar products.

Implementing a federal unit price labeling policy in the U.S. would entail consideration of states’ enforcement roles and resources. Subject matter experts from NIST’s Office of Weights and Measures explained that states play a role in the enforcement of certain federal laws, such as the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act. They said the enforcement of a federal unit price labeling policy would likely rely on states, and some states may not have the resources to expand their responsibilities. Additionally, representatives from one state agency said that if a federal requirement were adopted, states’ enforcement roles should be clearly defined. In considering such a policy, policymakers might consider how best to balance consumer benefits against cost of enforcement.

Using Retail Scanner Data to Monitor Product Size Changes

We identified statistical organizations in eight countries that have used, or plan to use, retail scanner data to better incorporate the impact of item size changes into their consumer price indexes.[64] This approach may help improve understanding of how product size changes may affect inflation.

Before adopting scanner data, these organizations used methods similar to BLS’s current approach, which involves collecting prices and size information from a sample of retail outlets on a sample of products. Under that approach, inflation is measured on the basis of the selected sample and periodic observations of price and size changes by data collectors. In contrast, retail scanner data generally include detailed information—such as price, size (e.g., weight or volume), item description, and sales—for nearly all items that retailers included in the data, including items that commonly change in size. These include products such as food, hygiene items, and cleaning supplies.

The experiences of the eight statistical organizations in other countries suggest that integrating retail scanner data—whether alone or alongside traditional methods—can offer several advantages. These organizations stated that scanner data allowed them to better incorporate item size changes into their consumer price indexes compared with traditional methods.

These statistical organizations noted that a key advantage of scanner data is more frequent and comprehensive coverage of item size changes. All eight organizations stated that scanner data expanded data coverage, such as inclusion of high-sales items not captured in their sampled market basket. This coverage has enabled more complete, accurate, and timely data inputs and allowed them to better capture the impact of size changes on inflation. Additionally, because scanner data reflect actual consumer purchases, they can be used to develop more accurate expenditure weights. This approach offers a clearer picture of household consumption than traditional methods that rely on consumer surveys.

However, adopting retail scanner data to incorporate product size changes into the CPI, or for other purposes, would entail important considerations and trade-offs. Four foreign statistical organizations stated that they had to reach separate data provision agreements with each retailer supplying the data.[65] Similarly, BLS officials said they attempted to secure direct access to data from large retailers in 2019 and 2020 but were unsuccessful.

In addition, while scanner data from third-party aggregators are available, BLS officials expressed concerns about the potentially high acquisition costs of obtaining timely data to meet BLS’s production needs. They also expressed concerns about alternatives if acquired data become unavailable or too costly. Additionally, five foreign statistical organizations stated they had to hire or train staff with specific technical skills to process and analyze the data. They also had to build infrastructure capable of storing and processing large datasets.

Other Policy Options

Our research also identified additional policy options to address transparency concerns related to product downsizing.

· Educating consumers. The Canadian government has created an online campaign to raise consumer awareness of product downsizing. It has also provided grants to nonprofit organizations to conduct research and develop consumer resources. Canadian officials told us they conduct outreach through official web pages, social media, and e-newsletters, providing consumers with tools, tips, and resources about product downsizing. The officials told us that it was too early to measure the results of these efforts, but they plan to use web analytics to examine citizen engagement with published content.

· Prohibiting deceptive downsizing practices. Legislative proposals in Germany and the U.S. would restrict certain product downsizing practices deemed unfair or deceptive. In Germany, a draft bill would generally prohibit reducing the content of a product while keeping the size of the packaging the same, according to literature we reviewed.[66] This provision was reportedly intended to prevent consumer deception.[67] In the U.S., proposed legislation would treat product downsizing by manufacturers as an unfair or deceptive act or practice under the Federal Trade Commission Act.[68] The bills would authorize FTC to issue regulations further defining what constitutes product downsizing for this purpose.[69] Six of eight academics we interviewed expressed concerns that wholly classifying product downsizing as unfair or deceptive would limit manufacturers’ flexibility to decrease sizes in response to consumer preferences. Additionally, FTC officials noted that not all downsizing is deceptive. As noted previously, in some cases, consumers may prefer smaller package sizes over equivalent price increases.

Agency Comments

We provided a draft of this report to BLS, the Department of Justice (DOJ), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), FTC, and NIST for review and comment. Three agencies, BLS, DOJ, and NIST, provided technical comments, which we incorporated as appropriate. Two agencies, FDA and FTC, stated that they had no comments on the report. We also requested comments on relevant sections of the draft report from key third parties, including certain agencies in foreign countries that provided information. We incorporated technical comments we received from some of the third parties as appropriate.

We are sending copies of this report to the appropriate congressional committee, the Attorney General, the Chairman of FTC, the Secretary of Commerce, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Secretary of Labor, and other interested parties. In addition, the report is available at no charge on the GAO website at https://www.gao.gov.

If you or your staff have any questions about this report, please contact Alicia Cackley at cackleya@gao.gov or Michael Hoffman at hoffmanme@gao.gov. Contact points for our Offices of Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page of this report. GAO staff who made key contributions to this report are listed in appendix IV.

Sincerely,

Alicia Puente Cackley

Director,

Financial Markets and Community Investments

Michael Hoffman

Director,

Applied Research and Methods

This report examines product downsizing, commonly called “shrinkflation.” Specifically, we examined (1) trends in product downsizing and upsizing, (2) factors affecting how consumers respond to product downsizing in their purchase decisions, and (3) the advantages and disadvantages of policy options to address concerns related to product downsizing.

Trends in Product Downsizing and Upsizing

For our first objective, we analyzed available Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data from 2015 through 2024 on the frequency of downsizing and upsizing.[70] Additionally, we analyzed available BLS research indexes from 2015 through 2024 that estimate the impact of downsizing and upsizing on the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The BLS frequency data capture the number of reports of product downsizing and upsizing each month in the CPI sample. The research indexes are used to estimate the resulting impact of product size changes on inflation. For more information about this analysis, see appendix II.

To assess the reliability of BLS’s data, we interviewed BLS officials about their trend analysis and underlying data and examined related documentation. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing trends in product downsizing and upsizing.

To analyze trends in product downsizing and upsizing for thousands of items in seven selected product categories, we obtained weekly retail scanner data from NielsenIQ from 2021 through 2023.[71] We used the data to measure the extent of downsizing and upsizing within the selected product categories, as well as the changes in unit prices for items that were downsized. The data captured all sales across all included outlets at the item level. An item refers to a unique product with a specific size and characteristics produced by a brand. For each item sold, the NielsenIQ data include a product identification number (Universal Product Code or UPC), item name, price, number of units sold, total dollar sales, and several product characteristics.[72] We used this information in conjunction with the BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey to select products for our analysis.

First, we identified broad product categories within the BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey that are commonly sold in retail settings and could experience downsizing or upsizing. We excluded product categories containing only services (such as entertainment) or products not packaged for retail sale as consumer-packaged goods (such as transportation). We further excluded categories that include age-restricted products (such as alcoholic beverages and tobacco) because we focused on products that are available for all consumers. After these exclusions, four broad product categories within BLS’s major expenditure categories remained: food-at- home, household products (such as housekeeping supplies), personal care products (such as hair, dental, and shaving products), and over-the-counter drugs.

Next, we used total dollar sales in the NielsenIQ retail scanner data to select products within the four broad categories identified above. Unlike BLS’s Consumer Expenditure Survey, NielsenIQ data divide broad product categories into “supercategories.” We received data on 102 supercategories and ranked them by total dollar sales to prioritize those with higher consumer expenditures. We excluded supercategories consisting of fresh foods sold by piece or a specific unit of weight (such as “prepared foods” and “vegetables”), as they were unlikely to be downsized. After these exclusions, 19 supercategories remained. We then identified the highest-selling product within each of the 19 supercategories by total dollar sales from 2021 through 2023 and grouped them under the four broad categories: food, household products, personal care products, and over-the-counter drugs.[73]

For each of the four broad categories, we generally selected one to three of the highest-selling products to analyze for size changes:

· Food. The NielsenIQ data contained multiple supercategories of food products. The NielsenIQ supercategory with the highest selling food product was “Beverages,” in which soft drinks had the highest sales. Other NielsenIQ supercategories with high-selling products were “Salty Snacks” and “Candy, Gum, and Mints,” which include products like potato chips and chocolate. Although BLS and other studies have found that snacks have historically experienced frequent size changes, we excluded these categories from our analysis because regulations around sugar content in some states may have contributed to smaller package sizes. The next highest-selling supercategories were “Packaged Coffee,” followed by “Cereal and Granola.” As a result, we focused our analysis of product size changes on coffee and cereal.

· Household products. The highest-selling household product was in the “Paper & Plastics” supercategory, which included a range of widely sold products. The top products were toilet paper (bath tissue) and paper towels. The next highest-selling household product was in the “Laundry Care” supercategory, with laundry detergent as the top-selling product. Accordingly, we focused our analysis on size changes in toilet paper, paper towels, and laundry detergent.

· Personal care. Among personal care products, the highest-selling item was in the “Oral Hygiene” supercategory. We focused our analysis on toothpaste, the top-selling product within that category.

· Over-the-counter-drugs. The highest-selling over-the-counter drug product was in the “Pain Relief” supercategory. We focused on internal analgesics (such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen), the top-selling products within that category. For the purpose of this report, we refer to internal analgesics as pain relievers or pain relief products.

After selecting the seven products—coffee, cereal, toilet paper, paper towels, laundry detergent, toothpaste, and pain relievers—we analyzed NielsenIQ data for trends in product downsizing and upsizing from 2021 through 2023 for items within these product groups, including the extent of product downsizing and upsizing and effects on unit prices.[74] To assess the reliability of the NielsenIQ data, we analyzed these data, examined related documentation, and interviewed NielsenIQ representatives. We determined that the data were sufficiently reliable for the purpose of describing trends in downsizing and upsizing. For more detailed information about the NielsenIQ data analysis and data reliability, see appendix III.

We also reviewed studies identified through a literature search broadly on product downsizing and upsizing. We restricted our searches to publications from 2004 through 2024. We conducted keyword searches in scholarly databases, including Scopus, EconLit, ABI/Inform, and Policy File Index, among others. Our search strategy focused on variations of terms related to package sizing (such as “downsizing,” “upsizing,” “increases,” and “shrinkflation”), pricing (such as “unit prices,” “inflation,” and “consumer price index”), and consumer goods (such as “groceries,” “packaged goods,” and “food”). Our search encompassed peer-reviewed journals, conference papers, working papers, and books, and it yielded 135 results.

One economist and one analyst independently reviewed abstracts for all 135 results. We excluded all working papers written before 2020 and identified 36 studies with potential topical relevance to our study. Pairs of analysts and economists then independently reviewed the 36 studies in their entirety for methodological soundness and to confirm their relevance.

To assess methodological soundness, we reviewed the studies’ research design (e.g., survey, experiment, literature review, or data analysis), data sources, sample size, methodological assumptions, and stated limitations. For example, a methodologically sound study might include robustness checks, contain sufficient data to support its conclusions, or control for many possible sources of variation affecting the outcome. This process resulted in 26 studies that were determined to be both methodologically sound and topically relevant. Of these, we identified and reviewed two that included analysis of trends in product downsizing and upsizing.

We also interviewed officials from the Bureau of Economic Analysis about available data and research on product downsizing and upsizing.

Factors Affecting How Consumers Respond to Product Size Changes

For our second objective, we reviewed the 26 methodologically sound studies discussed above and identified 17 that analyzed consumer responses to downsizing. While our literature search included terms related to product upsizing, we found no research addressing consumer responses to upsizing.

Additionally, we interviewed a nongeneralizable selection of seven academics, three consumer groups, and three industry groups to obtain their perspectives on how consumers respond to downsizing.

· Academics. We used the literature search to identify potential interviewees, and we selected eight academics for the relevance of their research and fields of expertise. Seven agreed to be interviewed and one did not respond. Three interviews were conducted jointly with coauthors. The participants had expertise in agricultural economics, consumer economics, behavioral economics, and marketing.

· Consumer and industry groups. We used the Gale Encyclopedia of Associations to identify organizations representing consumers, retailers, manufacturers, and distributers. We selected groups that had relevant missions, represented key stakeholders with knowledge of the issue, or had published prior work related to product downsizing or upsizing. Consumer groups we interviewed were the National Consumer League, National Association of Consumer Advocates, and Consumer World. Industry groups we interviewed were the Consumer Brands Association (which represents manufacturers), FMI (which represents retailers, wholesalers, and manufacturers), and the National Grocers Organization (which represents independent grocers and wholesalers). We contacted three additional organizations representing these entities, but they declined to be interviewed.

Policy Options to Address Concerns Related to Product Downsizing

For our third objective, we first identified potential policy options that address concerns related to product downsizing through a review of news articles and legal materials identified in a literature search. We conducted keyword searches of legal, news, and policy-focused databases—including Lexis+, Law360, PAIS International, and ProQuest Newsstand Professional—drawing from both international and domestic sources published from 2014 through 2024. We used search terms similar to those used for other objectives, such as those related to package sizing and pricing, along with additional terms, such as “policy,” “legislation,” and “regulations.” Through this search, we identified relevant legal sources, legislative materials, government reports, think tank publications, trade journals, and news articles. Two analysts independently reviewed the results to determine topical relevance to product downsizing policies.

From these search results, we identified five current or proposed policy options: mandating labeling or other disclosures of product downsizing by retailers or manufacturers, using uniform unit pricing, using retail scanner data to detect product size changes, promoting public education about product downsizing, and prohibiting product downsizing practices deemed unfair or deceptive. Using the same literature review process described for our first objective, we then identified eight methodologically sound studies that analyzed one or more of the policy options and reviewed these studies.

We also identified 11 countries that had adopted or proposed at least one of the five policy options other than the use of retail scanner data (which was common among these countries), on the basis of the results of the literature search described above. From this list, we selected five countries for interviews, prioritizing those that had adopted or proposed multiple policy options and, secondarily, those that offered geographic diversity. In addition to interviewing officials from relevant organizations in these five countries, we obtained written information from national statistical organizations in four others, selected in part based on interviewee recommendations identifying them as conducting research using scanner data.

In total, we interviewed or obtained written responses from governmental agencies in nine countries about the policy options we identified, including the advantages and disadvantages of the options.

· Australia. We interviewed officials from the Australian Treasury and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission about unit pricing policies, and we interviewed the national statistical organization (Australian Bureau of Statistics) about retail scanner data.[75]

· Canada. We interviewed officials from Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada about public education funding related to downsizing, and we interviewed the national statistical organization (Statistics Canada) about retail scanner data.[76]

· France. We interviewed officials from the Directorate General for Competition Policy, Consumer Affairs and Fraud Control about downsizing disclosure requirements and unit pricing policies.[77] We also interviewed the national statistical organization (National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies) about retail scanner data.[78]

· Germany. We obtained written responses from the Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection about existing policies on unfair or deceptive practices and unit pricing.[79] We also interviewed the national statistical organization (Federal Statistical Office of Germany) about retail scanner data.[80]

· South Korea. We obtained written responses from the Korea Fair Trade Commission about downsizing disclosure requirements.[81]

· Belgium, Netherlands, Poland, and United Kingdom. We obtained written responses from the national statistical organizations in each of these countries regarding retail scanner data. Respectively, they are Statistics Belgium, Statistics Netherlands, Statistics Poland, and United Kingdom’s Office for National Statistics.[82]

Officials in Germany and South Korea provided written responses to our questions in German and Korean, respectively. We translated the responses into English internally. For each translation of the respective languages, one person translated the responses and a second person reviewed the translation.

In addition to contacting foreign countries about the policy options described above, we reviewed secondary sources and other literature describing relevant legal requirements. The discussion of foreign legal requirements in this report is not an official translation or authoritative statement of law.

Regarding unit pricing policies, we requested interviews with relevant agencies in five states to include states in different U.S. regions, states with and without unit pricing policies, and states with different population sizes. Three states did not respond to our request. We interviewed or obtained written responses from two agencies responsible for unit pricing policies in two states, New Jersey and Arkansas. New Jersey is a medium-sized northeastern state, while Arkansas is a small southern state. New Jersey adopted a mandatory unit pricing policy and Arkansas adopted a voluntary unit pricing policy, according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).[83] We interviewed officials from New Jersey’s Office of Weights and Measures and obtained written responses from the Arkansas Department of Agriculture.

In addition, in our interviews with academics, consumer groups, and industry groups, described above, we obtained their perspectives on advantages and disadvantages of the identified potential policy options. We also interviewed the Federal Trade Commission and NIST officials on this topic. Additionally, we interviewed officials from the Department of Justice and Food and Drug Administration on the topics of product packaging, labeling, and downsizing.

We conducted this performance audit from February 2024 to July 2025 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Data

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data collectors document prices for the same set of unique goods and services over time for the Consumer Price Index (CPI). As a part of this process, the data collectors identify and verify product size changes so that the effective price changes experienced by consumers can be reflected in the CPI, according to BLS. The collectors notify the BLS economist reviewing the data of these changes, and the economist notifies other collectors. BLS economists also identify size changes through monthly reviews of CPI data and online research, according to BLS. BLS published monthly data on the frequency of downsizing and upsizing in the CPI sample from January 2015 through December 2024, which were the most recent data available at the time of our review.

Using these data, BLS created a series of research indexes—beginning with December 2014 data—known as the CPI size change research index (R-CPI-SC).[84] These indexes estimate the impact of downsizing and upsizing on the CPI. We used the indexes from 2015 through 2024 for our analyses. They were calculated by imputing a price change in the month a product size change occurred, rather than using its observed price change. This approach removes the effect of the size change on the price per unit. By comparing the research indexes to the regular, monthly CPI indexes that BLS publishes, it is possible to estimate the effect of product size changes on inflation.

Methodology

We used the total monthly number of reports of downsized and upsized items in the CPI sample to analyze changes in product size from 2015 to 2024. We used the available BLS research index data to estimate the overall impact of product size changes on inflation. BLS provides CPI size change index data for some but not all products that constitute the CPI for all items. Following BLS’s guidance on constructing special CPIs and their percent change, we constructed a modified research index on the basis of the products for which the research data were available and a modified version of the CPI for all items.[85] Specifically, we used available Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (also called CPI-U) cost weight data for December 2019 and December 2024, along with available CPI-U and R-CPI-SC index levels for the same period, to calculate percent changes in overall inflation over time. In essence, this modified research index shows how the CPI would have changed had BLS not adjusted for product size changes. By comparing the modified research index with the modified CPI over time, we estimated the effect of downsizing and upsizing on a measure of overall inflation. We did this comparison to estimate the overall effect of product size changes from December 2019 to December 2024, as well as the effect for broad product categories. These categories include food, household products, and nonprescription drugs, as well as more specific products like snacks, candy and chewing gum, and household paper products.

Finally, we identified product categories in the BLS research index data that mirrored the products we analyzed using NielsenIQ data, to the extent possible (see discussion of NielsenIQ data in app. I). These products include household paper products, personal care products, coffee, cleaning products, and breakfast cereal. We calculated the monthly percentage difference between the 12-month percent change in the research index and the 12-month percent change in the CPI for these products using available data from 2015 through 2024.[86] This allowed us to analyze the effect of downsizing on individual products’ year-over-year CPIs over this period.

Limitations

One limitation of the BLS data is that product size changes can only be observed for items included in the CPI sample. The CPI sample is a subset of products sold in the market, and products are regularly rotated in and out. Because BLS does not track all items sold, it cannot (and does not intend to) capture all instances of downsizing and upsizing. Additionally, BLS’s in-person price collection relies on the judgment of the price collector to identify comparable substitutes when items in the CPI sample are permanently out of stock.

Another limitation is that the research indexes are calculated outside of the official production system and are at greater risk of calculation errors than the official CPI indexes, according to BLS. Additionally, they differ from the official indexes in both scope and aggregation and may not have the same data quality as the official published indexes. In order to calculate the effect of product size changes on overall inflation, we calculated special, modified indexes, which are not official CPI indexes. As a result, our calculations may not match published BLS estimates. Moreover, the CPI sample is designed to measure average changes over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of material goods and services, not specifically to track the frequency of product size changes. Therefore, it is not designed specifically to measure downsizing and upsizing frequencies in the broader marketplace. Despite the limitations associated with these data, they are informative about the trends in downsizing and upsizing and the effect of product size changes on inflation.

Results

With respect to the frequency of downsized and upsized items in the CPI sample, we found that downsizing occurred more frequently than upsizing from 2015 through 2024. We generally found that there were more reports of downsized items in the CPI before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 than in the years that followed. In 2020 and 2021, reports of both downsized and upsized items were low, but the frequency of downsizing increased in 2022 as inflation rose. From 2021 to 2024, there were three times as many reports of downsized items as upsized ones in the CPI.

Using the research index data, we found that, according to the change in the modified research CPI, inflation increased by 34.45 percent from 2019 to 2024, when not accounting for product size changes. The change in the overall modified CPI that included the same products was 34.51 percent, suggesting that the overall effect of downsizing on the CPI over the 5-year period was about 0.06 of a percentage point, with an annual average effect of about 0.01 of a percentage point.

We found that downsizing had a greater effect on inflation in some product categories than others. For example, in the food product category, downsizing increased inflation for food by 0.38 of a percentage point over the 5-year period, compared with 0.06 of a percentage point for household products. The smaller effect in the household product category is likely due to the inclusion of items like electricity and home insurance, which are not subject to product size changes. Moreover, for specific products, like household paper products, the effect was pronounced, with downsizing accounting for an increase in the CPI of 3.0 percentage points between 2019 and 2024. Table 1 presents all specific products for which we found a non-zero effect of downsizing on the item’s CPI.

Table 1: Effect of Downsizing on Consumer Price Index (CPI) by Product, December 2019–December 2024

|

Product |

Effect of downsizing on product CPI |

|

|

Household paper products |

3.0% |

|

|

Snacks |

2.6 |

|

|

Candy and chewing gum |

2.3 |

|

|

Ice cream and related products |

1.8 |

|

|

Breakfast cereal |

1.6 |

|

|

Coffee |

1.4 |

|

|

Other processed fruits and vegetables including dried |

1.4 |

|

|

Sugar and sugar substitutes |

1.3 |

|

|

Cakes, cupcakes, and cookies |

1.2 |

|

|

Other fats and oils including peanut butter |

1.2 |

|

|

Other bakery products |

1.0 |

|

|

Frozen and freeze dried prepared foods |

1.0 |

|

|

Other miscellaneous foods |

0.9 |

|

|

Indoor plants and flowers |

0.8 |

|

|

Flour and prepared flour mixes |

0.8 |

|

|

Other beverage materials including tea |

0.7 |

|

|

Fresh biscuits, rolls, muffins |

0.6 |

|

|

Fresh fish and seafood |

0.6 |

|

|

Soups |

0.6 |

|

|

Nonfrozen noncarbonated juices and drinks |

0.5 |

|

|

Other uncooked poultry including turkey |

0.4 |

|

|

Household cleaning products |

0.4 |

|

|

Other dairy and related products |

0.3 |

|

|

Canned fruits and vegetables |

0.3 |

|

|

Other pork including roasts, steaks, and ribs |

0.3 |

|

|

Frozen fruits and vegetables |

0.3 |

|

|

Nonprescription drugs |

0.2 |

|

|

Spices, seasonings, condiments, sauces |

0.2 |

|

|

Garbage and trash collection |

0.2 |

|

|

Rice, pasta, cornmeal |

0.2 |

|

|

Chicken |

0.2 |

|

|

Pork chops |

0.2 |

|

|

Carbonated drinks |

0.2 |

|

|

Other sweets |

0.1 |

|

|

Cheese and related products |

0.1 |

|

|

Potatoes |

0.1 |

|

|

Other fresh vegetables |

0.1 |

|

|

Food from vending machines and mobile vendors |

-0.1 |

|

|

Cosmetics, perfume, bath, nail preparations and implements |

-0.1 |

|

|

Baby food and formula |

-0.1 |

|

|

Beer, ale, and other malt beverages at home |

-0.1 |

|

|

Food at employee sites and schools |

-0.1 |

|

|

Miscellaneous household products |

-0.2 |

|

|

Hair, dental, shaving, and miscellaneous personal care products |

-0.2 |

|

Source: GAO analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data. | GAO‑25‑107451

We found that the effect of size changes on the CPI varied by item from 2015ؘ through 2024, according to our analysis of selected items in the BLS data that were similar to those we analyzed using the NielsenIQ data.

Additionally, certain product categories experienced product downsizing more acutely during the period of higher inflation during and following the COVID-19 pandemic, according to our analysis of BLS data.

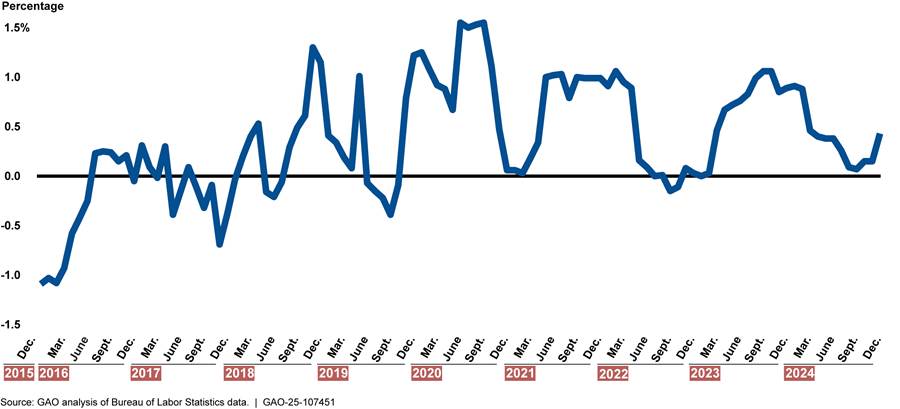

· Breakfast cereal. From January 2015 through June 2018, product size changes had a near-zero effect on cereal’s CPI. Downsizing began to increase per-unit cereal prices later in 2018. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and early 2021, the effect returned closer to zero. However, as inflation rose in late 2021 and into 2022, the effect became more persistent. In December 2024, product downsizing increased per-unit cereal prices in the CPI by 0.5 percentage points, compared with the previous year (see fig. 12).

Figure 12: Impact of Size Changes on Per-Unit Cereal Prices in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

Note: Percentage differences above 0.0 indicate price increases from downsizing. Percentage differences below 0.0 indicate price decreases from upsizing. The line shows the percentage difference between the 12-month percent change in the CPI production series and the 12-month percent change in the CPI size change research series. The CPI research series removes size changes from the production series, so differences between the two estimate the price increase or decrease due to changing sizes.

· Coffee. Before August 2022, product downsizing had a relatively small impact on coffee’s CPI. However, from August 2022 through June 2023, downsizing increased the year-over-year percent change in per-unit coffee prices in the CPI by about 1 percentage point in each month (see fig. 7 earlier in this report).

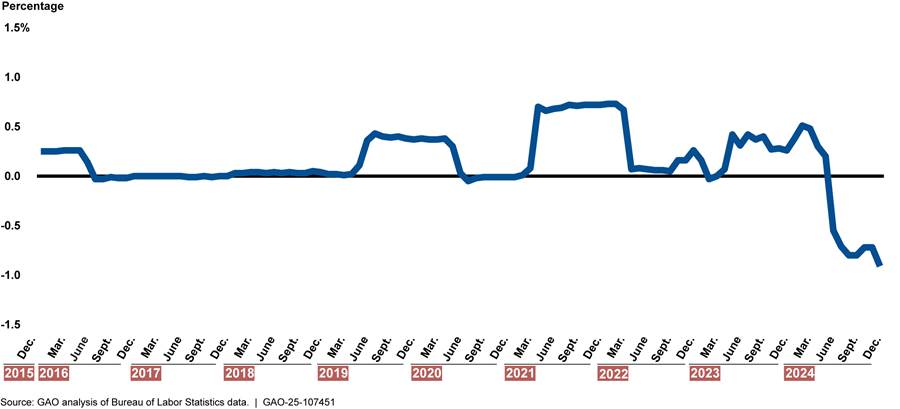

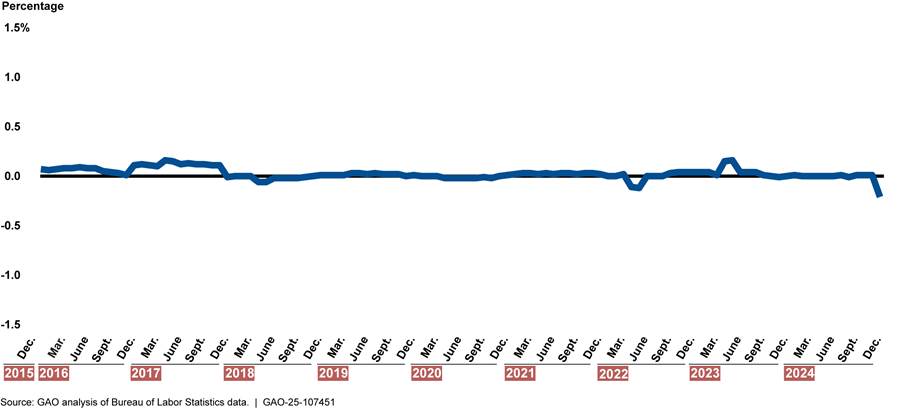

· Cleaning products (including laundry detergent). From June 2016 through May 2019, downsizing had little impact on per-unit cleaning product prices in the CPI. From June 2019 through April 2020, product downsizing increased year-over-year prices by about 0.4 percentage points in each month. From June 2020 through March 2021, during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, downsizing dropped to near zero. From April 2021 through March 2022, downsizing increased the year-over-year percent change in prices by about 0.7 percentage points in each month. Since then, the effects have been mixed, with evidence of more upsizing in 2024, which has helped reduce per-unit prices (see fig. 13).

Figure 13: Impact of Size Changes on Per-Unit Cleaning Product Prices in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

Note: Percentage differences above 0.0 indicate price increases from downsizing. Percentage differences below 0.0 indicate price decreases from upsizing. The line shows the percentage difference between the 12-month percent change in the CPI production series and the 12-month percent change in the CPI size change research series. The CPI research series removes size changes from the production series, so differences between the two estimate the price increase or decrease due to changing sizes.

· Household paper products (including toilet paper and paper towels). BLS data suggest that product size changes have affected this category frequently over the past decade. Prior to 2020, both downsizing and upsizing affected per-unit prices. Since 2020, downsizing has had a more consistent upward effect. For example, downsizing increased the year-over-year household paper product CPI by 1 percentage point in each month from May 2021 until April 2022 and again from July 2023 until February 2024 (see fig. 14).

Figure 14: Impact of Size Changes on Per-Unit Household Paper Product Prices in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

Note: Percentage differences above 0.0 indicate price increases from downsizing. Percentage differences below 0.0 indicate price decreases from upsizing. The line shows the percentage difference between the 12-month percent change in the CPI production series and the 12-month percent change in the CPI size change research series. The CPI research series removes size changes from the production series, so differences between the two estimate the price increase or decrease due to changing sizes.

· Nonprescription drugs (including over-the-counter pain relief drugs). Compared with the other selected products discussed above, the impact of product size changes has been minimal on per-unit nonprescription drug prices. Downsizing contributed to the nonprescription drug CPI in 2017 and again from March 2020 through February 2021, but the monthly effect on year-over-year inflation was less than 0.2 percentage points. Since 2022, the impact has remained near zero (see fig. 15).

Figure 15: Impact of Size Changes on Per-Unit Nonprescription Drug Prices in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

Note: Percentage differences above 0.0 indicate price increases from downsizing. Percentage differences below 0.0 indicate price decreases from upsizing. The line shows the percentage difference between the 12-month percent change in the CPI production series and the 12-month percent change in the CPI size change research series. The CPI research series removes size changes from the production series, so differences between the two estimate the price increase or decrease due to changing sizes.

· Personal care products (including toothpaste). The impact of product size changes has also been minimal on per-unit personal care product prices. Both downsizing and upsizing have affected the personal care product CPI over time, but the size of the year-over-year effect has generally been less than 0.2 percentage points (see fig. 16).

Figure 16: Impact of Size Changes on Per-Unit Personal Care Product Prices in the Consumer Price Index (CPI)

Note: Percentage differences above 0.0 indicate price increases from downsizing. Percentage differences below 0.0 indicate price decreases from upsizing. The line shows the percentage difference between the 12-month percent change in the CPI production series and the 12-month percent change in the CPI size change research series. The CPI research series removes size changes from the production series, so differences between the two estimate the price increase or decrease due to changing sizes.

Data